Abstract

Opioid use disorder (OUD) has become a national crisis and contributes to the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Emerging evidence and advances in experimental models, methodology, and our understanding of disease processes at the molecular and cellular levels reveal that opioids per se can directly exacerbate the pathophysiology of neuroHIV. Despite substantial inroads, the impact of OUD on the severity, development, and prognosis of neuroHIV and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders are not fully understood. In this review, we explore current evidence that OUD and neuroHIV interact to accelerate cognitive deficits and enhance the neurodegenerative changes typically seen with aging, through their effects on neuroinflammation. We suggest new thoughts on the processes that may underlie accelerated brain aging, including dysregulation of neuronal inhibition, and highlight findings suggesting that opioids, through actions at the μ-opioid receptor, interact with HIV in the central nervous system to promote unique structural and functional comorbid deficits not seen in either OUD or neuroHIV alone.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s-like pathology, Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), C-C Motif chemokine Receptor 5 (CCR5), Chloride homeostasis, K+-Cl− cotransporter 2 (KCC2) (SLC12A5), Microglia, μ-opioid receptor (OPRM1), Neuro-acquired immunodeficiency virus (neuroHIV), Neurodegeneration, Neuroinflammation, Opioid use disorder, Synaptodendritic injury

Introduction

Opioid use disorder (OUD) in the United States (U.S.) has reached catastrophic proportions and was declared a public health crisis in 2017 [1]. In April 2021, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported for the first time that drug overdose deaths in the U.S. exceeded 100,000 during the preceding year [2]. Of these, 75,673 were overdose deaths from opioids [2]. Injection drug use increases the likelihood of contracting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and opioid misuse and HIV have long been described as interrelated epidemics [3,4]. In fact, the opioid crisis is thought to be a major roadblock to achieving a “cure” of eradicating HIV within the current decade [5]. Additionally, chronic misuse of opioids can exaggerate HIV neuropathology and worsen neurocognitive outcomes of people living with HIV (reviewed in [6]). There have also been considerable reports within the last decade linking exposure to opioids by themselves with the development of age-related neurodegenerative disorders [7–9]. Since infected individuals are living longer due to current improvements in HIV therapeutics, the combined neuroinflammatory effects of opioids and HIV might lead to earlier onset of histopathological/biochemical indices typical of an aging brain. We describe histopathological indices of brain aging in the context of opioids and HIV, and provide an overview of novel neurodegenerative mechanisms that might converge to predispose the comorbid brain to the risk of developing early onset age-related pathologic changes.

Histopathological indices of an aging brain

Brain aging is a term used to describe the anatomic, functional, and histological changes that occur in the brain of an individual as they age. These changes usually become more evident from 70 years of age [10] and are mostly observable in brain regions that are critical to cognition and memory function. In pathologic scenarios, age-related brain changes occur at relatively younger age ranges and at exaggerated levels, and severely impact the daily activity of affected individuals. Most common histopathological changes indicative of brain aging include Alzheimer’s disease-like pathologic inclusions, atrophy, and abnormal vascular changes [10–12].

Alzheimer’s disease-like pathological changes include extracellular aggregation of amyloid β deposits, intraneuronal tangles such as hyperphosphorylated tau, and neurofibrillary tangles, with subsequent accumulation of abnormal, dense-cored, lysosomal structures known as granulovacuolar degeneration bodies [13,14]. Although overt neuronal loss is not always observable in aging brains, subtle changes to neuronal structure such as irregularities in dendritic arborization, reduction in spine density, and alterations in receptor and ion channel trafficking, have been well-documented (reviewed in [1]). These changes contribute to the cognitive decline that is seen in aging. A substantial body of emerging research suggests that chronic inflammation can initiate pathologic Alzheimer’s-like aggregate formation and brain aging [15–18]. Aggregate formation is also promoted by oxidative stress [19] and dysregulation of calcium signaling (reviewed in [20]). Reactive gliosis, aberrant signaling between central nervous system (CNS) immune cells and neurons, cellular senescence, and epigenetic alterations also contribute to accelerated brain aging [21].

Abnormal vascular changes, such as are seen in cerebral small vessel disease, are prevalent during brain aging and are characterized by blood-brain barrier dysfunction and altered cerebral blood flow [22–24]. It is noteworthy that similar vascular changes also occur, although to a lesser extent and in a more delayed manner, during the normal aging process. However, pathologic cases are marked by alteration to the structural and functional integrity of the blood-brain barrier, which results in hypoperfusion, enhanced inflammation due to CNS infiltration of serum-derived content, edema, and eventual cognitive decline [25]. An example of this cerebral vasculature-mediated aging disorder is evident in vascular cognitive impairment and dementia (commonly referred to in the literature as VCID), a disease associated with an age-associated failure of the neurovascular unit and likely worsened by opioid misuse [26]. Changes to the integrity and function of cerebral vasculature can increase inflammation, neuronal injury, and degeneration.

The effects of opioid misuse on neuroinflammation and histopathologic indices of brain aging

Clinically, OUD is associated with cognitive impairment [27], leukoencephalopathy, brain region-specific atrophy [28], and increased hyperphosphorylated tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles are reported in comparison to age-matched controls [7,29,30]. Chronic opioid use also results in lasting cognitive and psychomotor dysfunction including opioid-induced hyperalgesia and hyperkatifeia, and altered reward/saliency processing that can endure despite sustained abstinence [31,32]. These behavioral alterations coincide with lasting structural and epigenetic (e.g., altered DNA methylation and expression of non-coding RNAs) alterations and similarly occur in brain regions implicated in saliency, reward, and motivation [33–35].

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain in individuals with OUD generally reveals smaller mean relative volumes in specific brain regions of the cerebral cortex, including the prefrontal cortex [28] and basal ganglia [36–38], inferring a loss of neuropil and synapses. Heroin use is associated with white matter imaging hyperintensities that coincide with heightened microgliosis and inflammation [33,39,40]. In a rat model, heroin-induced reductions in axonal transport revealed by manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging coincide with diminished spatial memory and ultrastructural deficits, with many outcomes worsened by prolonged heroin exposure [41]. Importantly, imaging evidence also suggests some deficits in frontocingulate function associated with OUD may improve/reverse with prolonged abstinence [42].

Repeated, nonfatal opioid overdoses can result in accelerated postmortem, age-related or Alzheimer’s disease-like degenerative changes that are [43] similar to observations in fatal opioid overdoses [38]. Histologically, as many as 90% of the postmortem brain samples of individuals with OUD exhibit edema, astrogliosis, and microgliosis especially in the hippocampus, subcortical regions, and white matter compared to non-OUD samples from the same postmortem interval [37,43,44]. The reactive microgliosis [45] is accompanied by increases in proinflammatory cytokines and inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and nitric oxide synthase [46]. Sustained, low-level inflammation may be a CNS-specific feature of OUD [47,48], since opioids in the periphery tend to suppress immune function [49,50]. Interestingly, the histopathological profile and brain regions affected can differ with morphine, heroin, oxycodone, methadone, and fentanyl misuse depending on the outcome measure [38]. Although all these opioids are preferential μ-opioid receptor (MOR) agonists, subtle differences in pharmacological profiles at MOR and non-MOR receptors, and unique biased/selective agonists effects of each at MOR [51], undoubtedly underlie differences in their neuropathological properties. For delayed heroin overdose deaths exceeding a survival period of 5 h or more, studies report neurovascular disorders, hypoxic-ischemic leukoencephalopathy, and region-specific atrophy with neuronal losses that can include the hippocampal formation, cerebellum, and olivary nucleus, as well as other areas [28,52].

In rodent models, opioids also increase microgliosis and neuroinflammation [53], including the activation of heme-oxygenase, and increase the generation of reactive nitrogen species (reviewed in [54]). Nitric oxide is a byproduct of sustained opioid exposure [54,55] and interacts with oxyradical products of HIV infection [56] promoting nitrosative damage [6]. The neuroinflammatory effects of opioids are evident with both opium derivatives (e.g., heroin and morphine) and synthetic opioids (e.g., fentanyl). Fentanyl self-administration causes region- and exposure duration-specific alterations in specific interleukins and interferon regulatory genes within the nucleus accumbens and hippocampus of rats [48]. Prolonged oxycodone self-administration (3 years) increases biomarkers associated with neurodegeneration in plasma-derived exosomes in cynomolgus monkeys [57]. Neuronal, microglial, and astroglial-derived exosomes were sampled, and revealed increases in neurofilament light chain, α-synuclein, and microRNAs indicative of neuronal damage. Increases in pathologic phosphorylated forms of tau, amyloid β, and paired helical filaments have also been observed in murine brains following repeated injections of morphine, a prototypical opioid drug with abuse potential [58,59].

The effects of HIV on neuroinflammation and histopathologic indices of brain aging

Although overt dementia following neuroHIV pathology has decreased in the era of cART, a recent study showed that virally suppressed individuals still present Alzheimer’s disease-like changes like amyloid deposits and Alzheimer’s-like symptomatology [60]. Furthermore, reduced brain volume is evident in asymptomatic HIV-infected individuals [61]. Blood-brain barrier impairment and increased neurofilament light chain levels have been observed in CSF in virally suppressed individuals [62], while hyperphosphorylated tau has also been observed in HIV-infected postmortem brain samples [63]. The HIV-1 protein Tat can directly complex with Aβ [64], as well as increase hyperphosphorylated tau, neuronal deposits of paired helical filament [58], and astrocytic amyloid deposition [8] both in vitro and in animal models. These and other pathological markers associated with cognitive aging were also identified in an infectious, humanized mouse model of HIV [65]. Related to our discussion below, the C-C motif chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) blocker maraviroc substantially improved neuropathology in that study.

MOR and chemokine receptor interactions

There is increasing evidence that CCR5 signaling has an important role in cognitive processes and is a key site of opioid and HIV interaction. When HIV-exposed astroglia are exposed to opioids, opioids can induce synergistic increases in C-C chemokine motif ligand 5 (CCL5). We speculate that the opioid-dependent release of CCL5 by HIV-exposed astrocytes activates CCR5 and initiates a spiraling cascade involving chemokines (especially CCL2) and other inflammatory mediators in both astro- and microglia (reviewed in [6,66]). As described in later sections, this is a major factor in aging-related neuropathology. Deletion of a single CCR5 allele in otherwise normal mice improved cortical plasticity and memory related to hippocampal function, while CCR5 overexpression reduced function in the same tasks [67]. Additional studies with other CCR5 ligands were supportive of these findings [68]. Importantly, multiple methods of blocking CCR5 signaling have been shown to reduce memory impairment in animal models of CNS disorders, including stroke and traumatic brain injury [68,69]. Thus, the concept that alterations in CCR5 signaling by itself may be involved in neuropathology and age-related changes in HIV is well-founded. Mechanisms for how MOR-acting drugs might exacerbate these pathologies are more conjectural, but are based on the known abilities of MOR to interact with chemokine receptors, all of which are G-protein coupled receptors. Notably, in clinical trials assessing maraviroc as an HIV entry inhibitor, the cognitive effects have been mixed (e.g., [70,71]). The differing outcomes may reflect the fact that signaling through CCR5 can vary depending on context. To be beneficial, CCR5 blockade might depend on genetic background or could be limited or promoted depending on the duration of infection, interactions with other therapeutic agents, or comorbidities. Besides CCL5, CCR5 can also be activated by CCL3 and CCL4, which are independently regulated, and each are likely to have unique biased or agonist-selective actions at CCR5.

Opioid receptors are variably expressed by a wide variety of myeloid and lymphoid cell types and opioids have modulatory effects on immune function [49,50]. Typically, this results in immune suppression, but not exclusively [49,50]. Activation of MOR can result in increased HIV replication in infected cells in vitro, and can worsen HIV-induced neuropathology and cognitive damage through bystander inflammatory effects [6]. However, such interactions depend strongly on context, as well as the duration of co-exposure, in terms of whether they promote or inhibit HIV expression [6] (Fig. 1).

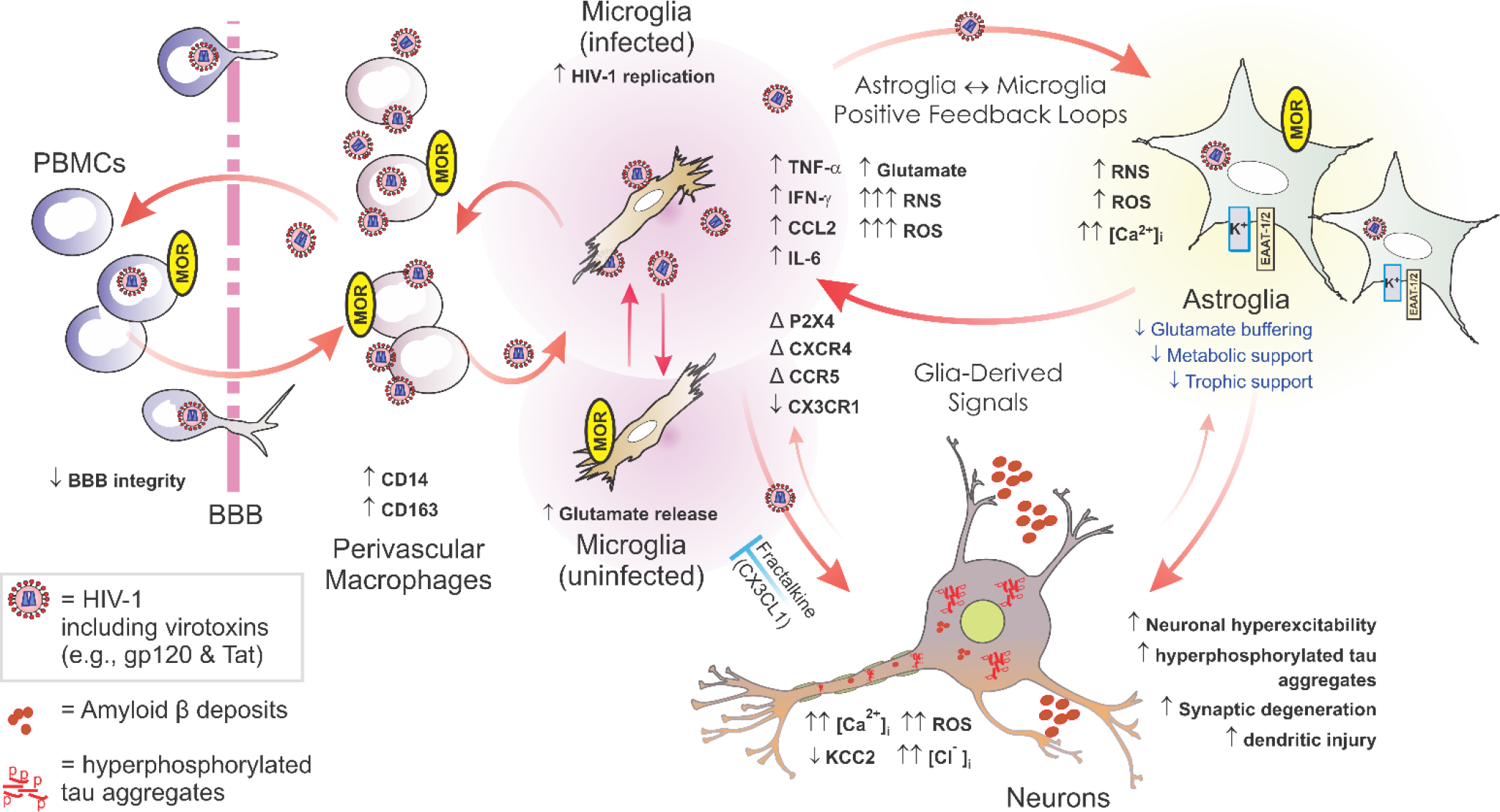

Figure 1.

Opioids can exacerbate HIV-1 CNS pathology through direct actions on phenotypically distinct subpopulations of opioid-receptor expressing glia—especially subsets of μ-opioid receptor- (MOR) expressing microglia and astroglia. The illustration above includes known and likely targets of opioid and HIV interactions. Microglia are likely infected through interactions with infiltrating, perivascular macrophages, and propagate the bulk of HIV infection in the CNS. HIV-1 also infects astroglia, but to a far lesser extent, and perhaps without the production of new virus. Infection results in the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and the release of HIV-1 proteins such as gp120 and Tat. All of these promote inflammation and cytotoxicity in bystander neurons and glia. OUD alone can cause premature Alzheimer-like changes and morphine by itself can enhance neurotoxicity in vitro; however, opiates appear to potentiate many of the pathophysiological effects of HIV in the central nervous system of infected individuals. μ, δ and κ-Opioid receptor expression varies among phenotypically distinct subpopulations of astro- and microglia and is quite heterogeneous [98,99]—differing among brain regions, throughout ontogeny, and depending on context; many astro- and microglia subpopulations do not express opioid receptors [100–102]. Many of the neurodegenerative effects of opioid-HIV interactions are the result of direct actions on microglia and astroglia, which then lead to a positive feedback cycle of inflammatory/cytotoxic signaling between HIV-1-infected microglia and astroglia. Abbreviations: α-chemokine “C-X-C” receptor 4 (CXCR4); altered or changed (Δ); β-chemokine “C-C” receptor 5 (CCR5); blood-brain barrier (BBB); decreased (↓); fractalkine (CX3CL1); fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1); increased (↑); interferon-γ (IFN-γ); interleukin-6 (IL-6); intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i); intracellular sodium concentration ([Na+]i); monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1 [or CCL2]); peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs); regulated upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES [or CCL5]); Toll-like receptor (TLR). Fractalkine released by neurons (and astroglia) can be neuroprotective by limiting the neurotoxic actions of microglia (blue “┬”); red arrows suggest pro-inflammatory/cytotoxic interactions. Modified, updated, and reprinted from reference [66] an “Open Access” article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/).

Aside from effects on HIV replication itself, the interactive effects of HIV and OUD on HIV infection, age-related brain neuropathogenesis, and negative cognitive outcomes are likely to involve direct interactions between multiple opioid receptors and chemokine receptors. The HIV co-receptors CCR5 and C-C chemokine motif receptor 4 (CXCR4) are well-positioned to participate in interactive outcomes [72,73]. Potential mechanisms for such interactions include heterologous cross-desensitization via downstream signaling events [72], and/or more direct dimeric or heteromeric interactions between opioid receptors and chemokine receptors [72,73]. Both MOR and δ-opioid receptor activation can alter/reduce the response of monocytes to multiple CCR5 ligands (CCL3, CCL4, CCL5) via MOR-dependent protein kinase Cζ activation. The MOR-specific ligand [D-Ala2,NMe-Phe4,Gly-ol5]-enkephalin (DAMGO) has been reported to upregulate CCR5 and CXCR4 on CD14+ monocytes, enhancing replication of both CCR5- and CXCR4-tropic strains of HIV [74]. Paradoxically, κ-opioid receptor activation is reported to act in an opposite manner to MOR activation. It is reported to inhibit HIV replication in primary human microglia and CD4-positive T cells, and to reduce CCL2 production by human astroglia in vitro (reviewed in [75]). Despite multiple reports that multiple μ, δ, and κ-opioid receptor types may modulate HIV replication and chemokine receptor signaling in isolated cell types grown in vitro, a more consolidated picture emerges in the brain. There, the exacerbated aging-related, neuronal injury and synaptic losses seen with opioids in neuroHIV appear to be largely mediated via MOR-expressing astroglia and microglia [6,76]. Reciprocally, HIV-1 Tat expression is also known to affect morphine’s efficacy and potency in vivo, reducing it depending on the context [77–79]. Interactions with CCR5 clearly play a role in these outcomes since the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc can reinstate morphine antinociceptive potency and restore physical dependence in morphine-tolerant mice exposed to HIV-1 Tat [80].

Both glia and neurons can express CCR5, raising the question of whether both cell types may participate, perhaps differently, in modulating the neurotoxic effects of MOR activation. Recent work in vitro suggests that glia are more prominently involved, since loss of CCR5 from glia (but not neurons) eliminated neurotoxic HIV-1 Tat and morphine interactions [81]. Pretreatment with maraviroc had a similar effect reducing the neuronal [Ca2+]i increase typically observed with Tat ± morphine exposure [81]. Selectively deleting either CCR5 [81] or MOR [76] from glia also completely protected against morphine’s ability to exacerbate Tat neurotoxicity. Unexpectedly, deleting CCR5 from glia entirely protected neurons from Tat toxicity alone. This outcome appeared to involve altered processing of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) precursor in a way that favored production of mature BDNF [81], a known neuroprotective agent [82,83]. In support of the neuroprotective effect of BDNF in this model, intranasally administered BDNF-conjugated clathrin triskelia reversed HIV Tat-induced deficits in hippocampal neurogenesis, synaptodendritic complexity, and learning and memory in transgenic mice [84]. Collectively, the findings suggest that loss of CCR5 may fundamentally change MOR signaling in HIV-exposed glia in a BDNF-dependent manner. Overall, the interaction of opioid and chemokine receptors, specifically MOR and CCR5, may alter the neuropathogenesis of HIV in a qualitatively unique manner not seen with either disorder alone.

Dysregulation of KCC2, Cl− homeostasis, and GABAergic function: A novel pathway to neuroHIV and aging-related outcomes?

K+-Cl− cotransporter 2 (KCC2) is the neuron-specific, major transporter responsible for maintaining [Cl−]i homeostasis and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) inhibitory function in the adult CNS. KCC2 functions to extrude Cl− from neurons, maintaining the low [Cl−]i necessary for GABA type A receptor- (GABAAR) induced membrane hyperpolarization. The functionality of KCC2 is determined by its proximity to the cell membrane and ability to oligomerize and is regulated by multiple phosphorylation sites. Serine 940 (S940) is a key residue that can be phosphorylated by protein kinase C to increase KCC2 trafficking and stability at the cell membrane. Reductions in KCC2 expression or function can increase [Cl−]i, reduce the hyperpolarization normally mediated via GABAAR, and can exaggerate the excitatory effects of glutamate [85]. Altered KCC2 function is implicated in multiple neurological disorders [86], including epilepsy, and enhancing KCC2 activity with CLP257 or its prodrug, CLP290 can alleviate key symptoms both pre-clinically and clinically, via a PP1-mediated mechanism.

KCC2 is a target of Tat, gp120, and HIV in primary human neurons in vitro and in HIV-1 Tat transgenic mice [87] and by logical extension, may be implicated in neuronal dysfunction in neuroHIV. Opioids also diminish KCC2 function and increase [Cl−]i [87–89], and the combination of opioids and HIV exacerbate KCC2 and [Cl−]i dysregulation experimentally [87] (Fig. 2). Both BDNF [90] and glially derived cytokines such as IL-1β [91,92], are potent regulators of KCC2. We speculate that reduced KCC2 function may underlie specific interactive effects of opioids and HIV. Loss of KCC2 activity may result from inflammation, especially excessive IL-1β, which affects dendrite and spine morphology, synaptic integrity, and excitatory/inhibitory balance [93], and is known to delay the normal developmental upregulation of KCC2 levels [91].

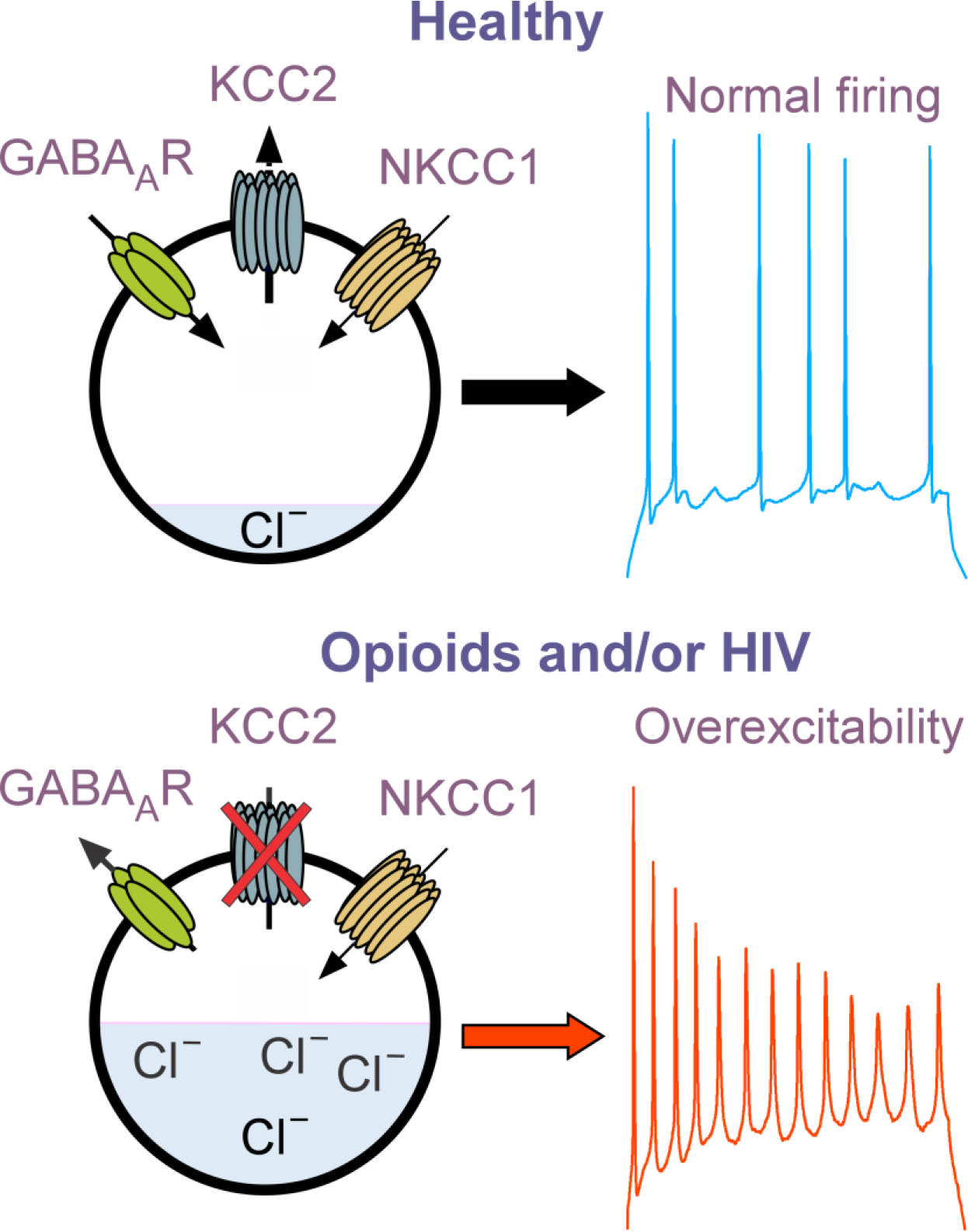

Figure 2. Effects of opioid- and/or HIV− induced deficits in KCC2 expression and/or function on neuronal excitability.

Our working model is that KCC2 pumps Cl− out of mature neurons allowing GABAAR activation to promote Cl− entry and neuronal inhibition. HIV and opioid-induced decreases in KCC2, which increase [Cl−]i result in neuronal depolarizing upon GABAAR activation and excess excitation in the presence of glutamate agonists (not shown). NKCC1 (which pumps Cl− into neurons) function tends to be constant and unaffected by extracellular factors or opioids and HIV.

Integrative BDNF, IL-1β, and KCC2 effects on indices of accelerated brain aging

In the sections above, and as summarized in Fig. 2, there are multiple pathways that intersect to drive the neuropathology and cognitive damage described as accelerated brain aging in HIV and OUD, either individually or interactively. HIV infection and/or drugs that are typical of OUD, mostly acting at glial cells, start a chain of events leading to overproduction of inflammatory factors. Among these is IL-1β, a potent regulator of KCC2 [91–94]. KCC2 maintains low [Cl−] inside of mature neurons, which allows Cl− entry and neuronal inhibition upon GABAAR activation. HIV and/or opioids decrease KCC2 levels, thus increasing [Cl−] within individual neurons. GABAAR activation thus results in less inhibition, and in extreme situations GABAAR activation can depolarize neurons. Overall, this drives excitotoxicity and damage in brain tissue. In addition, HIV/opiates also can independently reduce key neurotrophic factors, including mature BDNF, and increase multiple neurotoxic factors, including proBDNF. While this alone would hasten both structural and functional damage, depletion of mature BDNF also leads to disrupted processing of amyloid precursor proteins and accumulation of pathologic age-related proteins such as tau and amyloid β [95]. Amyloid β can further dysregulate Cl− homeostasis by increasing levels of NKCC1 [96], which directly opposes the effects of KCC2. Of importance to the above discussion, enhancing BDNF levels can increase KCC2 levels and restore both the Cl-equilibrium potential and GABAergic signaling in hippocampal area CA1, while improving learning in the Morris water maze in an Alzheimer’s disease model [97]. BDNF may thus be protective against aging-related cognitive changes in HIV/OUD by limiting neural injury through multiple pathways.

Summary

HIV-infected individuals can now expect a relatively normal lifespan but may experience aging-related changes in brain structure and function earlier and with more severity than non-infected individuals. Brain inflammation, and deficits in BDNF, which continue even in the absence of significant viral replication, are likely contributing factors. The underlying pathology appears to be enhanced by OUD, an outcome that might involve direct interactions between opioid and chemokine receptors, especially CCR5. A more speculative concept, but one relatively well-accepted for other diseases with cognitive dysfunction, is that opioid-mediated increases in cytokine production and altered BDNF processing in HIV-infected glia cause deficits in KCC2 function, thus leading to loss of neuronal [Cl−]i homeostasis. Experimental work suggests that BDNF might be an effective target to protect against combined HIV and OUD effects.

Acknowledgements.

We thank Dr. Viktor Yarotskyy for providing the illustration in Fig. 1. Because of reference limitations, we were unable to cite many publications that are supportive of this area of interest. We apologize to any authors whose relevant findings are not included in this review.

Funding.

We thank the National Institute on Drug Abuse: R01 DA057346, R01 DA034231, R01 DA045588, R01 DA044939, R21 DA057153 and R01 DA018633 for generous support.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.US-HHS: Determination that a public health emergency exists. Edited by Secretary–USHHS. Rockville, MD: US_Health_and_Human_Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CDC-NCHS: Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. Top 100,000 Annually. edn https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_releases/2021/20211117.htm. Edited by CDC NCfHS, Office of Communications, NCHS Press Room. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodder SL, Feinberg J, Strathdee SA, Shoptaw S, Altice FL, Ortenzio L, Beyrer C: The opioid crisis and HIV in the USA: deadly synergies. Lancet 2021, 397:1139–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leshner AI: HIV prevention with drug using populations. Current status and future prospects. Public Health Rep. 1998, 113 Suppl 1:1–3.:1–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerner AM, Fauci AS: Opioid Injection in Rural Areas of the United States: A potential obstacle to ending the HIV epidemic. JAMA 2019, 322:1041–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fitting S, McRae M, Hauser KF: Opioid and neuroHIV comorbidity - Current and future perspectives. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2020, 15:584–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovacs GG, Horvath MC, Majtenyi K, Lutz MI, Hurd YL, Keller E: Heroin abuse exaggerates age-related deposition of hyperphosphorylated tau and p62-positive inclusions. Neurobiol Aging 2015, 36:3100–3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 8. Sil S, Singh S, Chemparathy DT, Chivero ET, Gordon L, Buch S: Astrocytes & astrocyte derived extracellular vesicles in morphine induced amyloidopathy: implications for cognitive deficits in opiate abusers. Aging Dis 2021, 12:1389–1408. Long-term use of opiates is associated with cognitive impairments, and preclinically with synaptodendritic injury. This study take a closer look at a mechanism operative in astroglia that may contribute to the spread of amyloid deposition in the brain. Astrocyte-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) were examined from morphine-dependent rhesus macaques and cultures of morphine-exposed primary human astroglia. Morphine was shown to stimulate astrocyte production of amyloid and to induce release of EVs with amyloid cargo. Genetic and biochemical approaches showed involvement of the HIF-1α-BACE1 axis amyloid processes. The finding suggests a novel way in which astroglia may promote the seeding of neurodegenerative processes in chronic opiate users.

- 9.Dublin S, Walker RL, Gray SL, Hubbard RA, Anderson ML, Yu O, Crane PK, Larson EB: Prescription opioids and risk of dementia or cognitive decline: a prospective cohort study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015, 63:1519–1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scahill RI, Frost C, Jenkins R, Whitwell JL, Rossor MN, Fox NC: A longitudinal study of brain volume changes in normal aging using serial registered magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol 2003, 60:989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Svennerholm L, Bostrom K, Jungbjer B: Changes in weight and compositions of major membrane components of human brain during the span of adult human life of Swedes. Acta Neuropathol 1997, 94:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mrak RE, Griffin ST, Graham DI: Aging-associated changes in human brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1997, 56:1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kohler C: Granulovacuolar degeneration: a neurodegenerative change that accompanies tau pathology. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 132:339–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funk KE, Mrak RE, Kuret J: Granulovacuolar degeneration (GVD) bodies of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) resemble late-stage autophagic organelles. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2011, 37:295–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corlier F, Hafzalla G, Faskowitz J, Kuller LH, Becker JT, Lopez OL, Thompson PM, Braskie MN: Systemic inflammation as a predictor of brain aging: Contributions of physical activity, metabolic risk, and genetic risk. Neuroimage 2018, 172:118–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hou Y, Wei Y, Lautrup S, Yang B, Wang Y, Cordonnier S, Mattson MP, Croteau DL, Bohr VA: NAD(+) supplementation reduces neuroinflammation and cell senescence in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease via cGAS-STING. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118:e2011226118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh A, Comerota MM, Wan D, Chen F, Propson NE, Hwang SH, Hammock BD, Zheng H: An epoxide hydrolase inhibitor reduces neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Transl Med 2020, 12:eabb1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun XY, Li LJ, Dong QX, Zhu J, Huang YR, Hou SJ, Yu XL, Liu RT: Rutin prevents tau pathology and neuroinflammation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflammation 2021, 18:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Butterfield DA, Boyd-Kimball D: Oxidative stress, amyloid-β peptide, and altered key molecular pathways in the pathogenesis and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2018, 62:1345–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bezprozvanny I, Mattson MP: Neuronal calcium mishandling and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci 2008, 31:454–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sikora E, Bielak-Zmijewska A, Dudkowska M, Krzystyniak A, Mosieniak G, Wesierska M, Wlodarczyk J: Cellular Senescence in Brain Aging. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13:646924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caunca MR, De Leon-Benedetti A, Latour L, Leigh R, Wright CB: Neuroimaging of cerebral small vessel disease and age-related cognitive changes. Front Aging Neurosci 2019, 11:145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanon Zotin MC, Sveikata L, Viswanathan A, Yilmaz P: Cerebral small vessel disease and vascular cognitive impairment: from diagnosis to management. Curr Opin Neurol 2021, 34:246–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Silva TM, Faraci FM: Contributions of aging to cerebral small vessel disease. Annu Rev Physiol 2020, 82:275–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Banks WA, Reed MJ, Logsdon AF, Rhea EM, Erickson MA: Healthy aging and the blood-brain barrier. Nat Aging 2021, 1:243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kompella S, Al-Khateeb T, Riaz OA, Orimaye SO, Sodeke PO, Awujoola AO, Ikekwere J, Goodkin K: HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND): relative risk factors. In Neurocognitive Complications of HIV-Infection: Neuropathogenesis to Implications for Clinical Practice. Edited by Cysique LA, Rourke SB: Springer International Publishing; 2021:401–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruber SA, Silveri MM, Yurgelun-Todd DA: Neuropsychological consequences of opiate use. Neuropsychol Rev 2007, 17:299–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cadet JL, Bisagno V, Milroy CM: Neuropathology of substance use disorders. Acta Neuropathol 2014, 127:91–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anthony IC, Norrby KE, Dingwall T, Carnie FW, Millar T, Arango JC, Robertson R, Bell JE: Predisposition to accelerated Alzheimer-related changes in the brains of human immunodeficiency virus negative opiate abusers. Brain 2010, 133:3685–3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramage SN, Anthony IC, Carnie FW, Busuttil A, Robertson R, Bell JE: Hyperphosphorylated tau and amyloid precursor protein deposition is increased in the brains of young drug abusers. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2005, 31:439–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ersche KD, Clark L, London M, Robbins TW, Sahakian BJ: Profile of executive and memory function associated with amphetamine and opiate dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006, 31:1036–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 32. Browne CJ, Godino A, Salery M, Nestler EJ: Epigenetic mechanisms of opioid addiction. Biol Psychiatry 2020, 87:22–33. Epigenetic modifications caused by psychostimulants are thought to be involved in stable, epigenetic adaptations within brain regions that drive addictive behaviors. This review summarizes recent work regarding epigenetic changes with chronic opioid use, which may not generalize from studies with other addictive drugs targeting different cells and brain regions. Opioid exposure tends to promote overall higher levels of histone acetylation and lower levels of histone methylation, and there is an emerging role being identifed for noncoding RNAs in opioid addition. The authors suggest that progress towards opioid treatment/prevention strategies will require a shift in experimental focus towards human-relevant dosing regimens, volitional opioid-exposure regimens, and approaches that integrate epigenomic/transcriptomic discovery techniques with bioinformatic analyses.

- 33.Upadhyay J, Maleki N, Potter J, Elman I, Rudrauf D, Knudsen J, Wallin D, Pendse G, McDonald L, Griffin M, et al. : Alterations in brain structure and functional connectivity in prescription opioid-dependent patients. Brain 2010, 133:2098–2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serafini RA, Pryce KD, Zachariou V: The mesolimbic dopamine system in chronic pain and associated affective comorbidities. Biol Psychiatry 2020, 87:64–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koob GF, Volkow ND: Neurobiology of addiction: a neurocircuitry analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3:760–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muller UJ, Mawrin C, Frodl T, Dobrowolny H, Busse S, Bernstein HG, Bogerts B, Truebner K, Steiner J: Reduced volumes of the external and internal globus pallidus in male heroin addicts: a postmortem study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2019, 269:317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 37. Monick AJ, Joyce MR, Chugh N, Creighton JA, Morgan OP, Strain EC, Marvel CL: Characterization of basal ganglia volume changes in the context of HIV and polysubstance use. Sci Rep 2022, 12:4357. The basal ganglia is a region critical to motor function, cognition, and reward-seeking behavior, and is targeted by both drug abuse and HIV exposure. This small study (N=93) assessed the intersectional effects of HIV status and polysubstance use (stimulants and opioids) on gray matter volume in the basal ganglia and subregions (MRI), as well as behaviors associated with altered basal ganglia function. Three groups (HIV+, polydrug use+, HIV+/polydrug use+) were compared to an HIV−/polydrug use− group. While total gray matter volume and motor learning were reduced in all groups versus controls, only the HIV+/polydrug use+ group showed specific volume increases in the globus pallidus and putamen that were attributed to inflammation. This study shows that basal ganglia integrity is altered by the joint effects of HIV and polydrug use, and predict a role for inflammation as a causative factor. Opioid maintenance therapy is discussed as a factor complicating the analysis.

- 38.Blackwood CA, Cadet JL: The molecular neurobiology and neuropathology of opioid use disorder. Curr Res Neurobiol 2021, 2:100023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shrot S, Poretti A, Tucker EW, Soares BP, Huisman TA: Acute brain injury following illicit drug abuse in adolescent and young adult patients: spectrum of neuroimaging findings. Neuroradiol J 2017, 30:144–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li W, Li Q, Wang Y, Zhu J, Ye J, Yan X, Li Y, Chen J, Liu J, Li Z, et al. : Methadone-induced damage to white matter integrity in methadone maintenance patients: a longitudinal self-control DTI study. Sci Rep 2016, 6:19662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo Y, Liao C, Chen L, Zhang Y, Bao S, Deng A, Ke T, Li Q, Yang J: Heroin addiction induces axonal transport dysfunction in the brain detected by in vivo MRI. Neurotox Res 2022, 40:1070–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart JL, May AC, Aupperle RL, Bodurka J: Forging neuroimaging targets for recovery in opioid use disorder. Front Psychiatry 2019, 10:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 43. Voronkov M, Ataiants J, Cocchiaro B, Stock JB, Lankenau SE: A vicious cycle of neuropathological, cognitive and behavioural sequelae of repeated opioid overdose. Int J Drug Policy 2021, 97:103362. This review discusses brain changes that follow non-fatal overdose of opioids and provides evidence-based arguments that support the contribution of opioid overdose-induced brain injury/changes to the development of age-related neuropathological disorders.

- 44.Buttner A, Rohrmoser K, Mall G, Penning R, Weis S: Widespread axonal damage in the brain of drug abusers as evidenced by accumulation of β-amyloid precursor protein (beta-APP): an immunohistochemical investigation. Addiction 2006, 101:1339–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anthony IC, Arango JC, Stephens B, Simmonds P, Bell JE: The effects of illicit drugs on the HIV infected brain. Front Biosci 2008, 13:1294–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyuizen I, Lamash NE: Histo- and immunocytochemical detection of inducible NOS and TNF-α in the locus coeruleus of human opiate addicts. J Chem Neuroanat 2009, 37:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cahill CM, Taylor AM: Neuroinflammation-a co-occurring phenomenon linking chronic pain and opioid dependence. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2017, 13:171–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ezeomah C, Cunningham KA, Stutz SJ, Fox RG, Bukreyeva N, Dineley KT, Paessler S, Cisneros IE: Fentanyl self-administration impacts brain immune responses in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Brain Behav Immun 2020, 87:725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eisenstein TK: The role of opioid receptors in immune system function. Front Immunol 2019, 10:2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plein LM, Rittner HL: Opioids and the immune system - friend or foe. Br J Pharmacol 2018, 175:2717–2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gillis A, Kliewer A, Kelly E, Henderson G, Christie MJ, Schulz S, Canals M: Critical assessment of G protein-biased agonism at the mu-opioid receptor. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2020, 41:947–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buttner A: Review: The neuropathology of drug abuse. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2011, 37:118–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reiss D, Maduna T, Maurin H, Audouard E, Gaveriaux-Ruff C: Mu opioid receptor in microglia contributes to morphine analgesic tolerance, hyperalgesia, and withdrawal in mice. J Neurosci Res 2022, 100:203–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salvemini D: Peroxynitrite and opiate antinociceptive tolerance: a painful reality. Arch Biochem Biophys 2009, 484:238–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pasternak GW, Kolesnikov YA, Babey AM: Perspectives on the N-methyl-D-aspartate/nitric oxide cascade and opioid tolerance. Neuropsychopharmacology 1995, 13:309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ivanov AV, Valuev-Elliston VT, Ivanova ON, Kochetkov SN, Starodubova ES, Bartosch B, Isaguliants MG: Oxidative Stress during HIV Infection: mechanisms and consequences. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016:8910396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 57. Kumar A, Kim S, Su Y, Sharma M, Kumar P, Singh S, Lee J, Furdui CM, Singh R, Hsu FC, et al. : Brain cell-derived exosomes in plasma serve as neurodegeneration biomarkers in male cynomolgus monkeys self-administrating oxycodone. EBioMedicine 2021, 63:103192. Kumar et al. investigated and characterized brain-derived exosomes in monkeys with contingent oxycodone drug administration. The authors were the first to show a link between brain-derived exosomes and indices of neurodegeneration with prolonged exposure to oxycodone in a self-administering primate model. The authors further identified and characterize brain-specific exosomal cargo (e.g., neurofilament light chain) that correlate with reductions in the cerebral grey matter volume. Their findings highlight the utility of plasma exosomal cargo as a biomarker to identify prolonged opioid drug-induced neurodegeneration and brain aging.

- 58.Ohene-Nyako M, Nass SR, Hahn YK, Knapp PE, Hauser KF: Morphine and HIV-1 Tat interact to cause region-specific hyperphosphorylation of tau in transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett 2021, 741:135502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nass SR, Ohene-Nyako M, Hahn YK, Knapp PE, Hauser KF: Neurodegeneration within the amygdala is differentially induced by opioid and HIV-1 Tat exposure. Front Neurosci 2022, 16:804774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- * 60. Howdle GC, Quide Y, Kassem MS, Johnson K, Rae CD, Brew BJ, Cysique LA: Brain amyloid in virally suppressed HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2020, 7:e739. Howdle et al., using positron emission tomography, showed no group differences in amyloid deposition between virally suppressed people living with HIV and relatively older cognitively normal control individuals. However, upon a case-by-case comparison, the authors identified both abnormally high and abnormally low amyloid burden in the HIV cohort relative to the older cognitively normal controls with the abnormally low amyloid burden observed in individuals previously diagnosed with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before maintenance on cART. Their findings suggest that a pathophenotypic approach that takes into account the previous diagnosis of an HIV-infected individual is warranted in HIV-associated aging studies.

- 61.Stout JC, Ellis RJ, Jernigan TL, Archibald SL, Abramson I, Wolfson T, McCutchan JA, Wallace MR, Atkinson JH, Grant I: Progressive cerebral volume loss in human immunodeficiency virus infection: a longitudinal volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. HIV Neurobehavioral Research Center Group. Arch Neurol 1998, 55:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rahimy E, Li FY, Hagberg L, Fuchs D, Robertson K, Meyerhoff DJ, Zetterberg H, Price RW, Gisslen M, Spudich S: Blood-brain barrier disruption is initiated during primary HIV infection and not rapidly altered by antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 2017, 215:1132–1140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pushkarsky T, Ward A, Ivanov A, Lin X, Sviridov D, Nekhai S, Bukrinsky MI: Abundance of Nef and p-Tau217 in brains of individuals diagnosed with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders correlate with disease severance. Mol Neurobiol 2022, 59:1088–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 64. Hategan A, Bianchet MA, Steiner J, Karnaukhova E, Masliah E, Fields A, Lee MH, Dickens AM, Haughey N, Dimitriadis EK, et al. : HIV Tat protein and amyloid-β peptide form multifibrillar structures that cause neurotoxicity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2017, 24:379–386. The authors demonstrate that HIV-1 Tat binds to amyloid-β (Aβ) fibrils forming stable neurotoxic complexes. The extracellular Tat-Aβ complexes are physically more rigid, positively charged, and likely to bind, form pores and eventually rupture the neuronal cell membrane. Additionally, Tat-Aβ complexes might also be internalized into endolysosomes and further disrupt cell function. The ability of Tat to bind and augment Aβ cytotoxicity infers a direct mechanism by which HIV can promote Alzheimer’s-disease-like pathology in the brain.

- ** 65. Bhargavan B, Woollard SM, McMillan JE, Kanmogne GD: CCR5 antagonist reduces HIV-induced amyloidogenesis, tau pathology, neurodegeneration, and blood-brain barrier alterations in HIV-infected hu-PBL-NSG mice. Mol Neurodegener 2021, 16:78. In humanized mice, Bhargavan et al., show that HIV-1 infection increases pathologic indices of brain aging including Alzheimer’s disease-like pathologic aggregates and vascular impairments. Using the CCR5 receptor antagonist maraviroc, the authors show the involvement of the CCR5 HIV co-receptor in regulating the accretion of major histopathological indices of brain aging including amyloid β and phospho-tau isoforms. This study shows a direct involvement of HIV and/or virally induced factors in enhancing the risk of accelerated brain aging.

- 66.Hauser KF, Fitting S, Dever SM, Podhaizer EM, Knapp PE: Opiate drug use and the pathophysiology of neuroAIDS. Current Hiv Research 2012, 10:435–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhou M, Greenhill S, Huang S, Silva TK, Sano Y, Wu S, Cai Y, Nagaoka Y, Sehgal M, Cai DJ, et al. : CCR5 is a suppressor for cortical plasticity and hippocampal learning and memory. Elife 2016, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 68. Joy MT, Ben Assayag E, Shabashov-Stone D, Liraz-Zaltsman S, Mazzitelli J, Arenas M, Abduljawad N, Kliper E, Korczyn AD, Thareja NS, et al. : CCR5 Is a therapeutic target for recovery after stroke and traumatic brain injury. Cell 2019, 176:1143–1157 e1113. This article demonstrates that blockade of CCR5 with maraviroc improves functional recovery following stroke and traumatic brain injury. The authors additionally find improved recovery after stroke in individuals expressing CCR5Δ32, a CCR5 loss of function mutation.

- 69.Shen Y, Zhou M, Cai D, Filho DA, Fernandes G, Cai Y, Kim N, Necula D, Zhou C, Liu A, et al. : CCR5 closes the temporal window for memory linking. bioRxiv 2021:2021.2010.2007.463602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barber TJ, Imaz A, Boffito M, Niubo J, Pozniak A, Fortuny R, Alonso J, Davies N, Mandalia S, Podzamczer D, et al. : CSF inflammatory markers and neurocognitive function after addition of maraviroc to monotherapy darunavir/ritonavir in stable HIV patients: the CINAMMON study. J Neurovirol 2018, 24:98–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mora-Peris B, Bouliotis G, Ranjababu K, Clarke A, Post FA, Nelson M, Burgess L, Tiraboschi J, Khoo S, Taylor S, et al. : Changes in cerebral function parameters with maraviroc-intensified antiretroviral therapy in treatment naive HIV-positive individuals. AIDS 2018, 32:1007–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nickoloff-Bybel EA, Festa L, Meucci O, Gaskill PJ: Co-receptor signaling in the pathogenesis of neuroHIV. Retrovirology 2021, 18:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nash B, Festa L, Lin C, Meucci O: Opioid and chemokine regulation of cortical synaptodendritic damage in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Brain Res 2019, 1723:146409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Steele AD, Henderson EE, Rogers TJ: Mu-opioid modulation of HIV-1 coreceptor expression and HIV-1 replication. Virology 2003, 309:99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hu S, Sheng WS, Rock RB: Immunomodulatory properties of kappa opioids and synthetic cannabinoids in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2011, 6:528–539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zou S, Fitting S, Hahn YK, Welch SP, El-Hage N, Hauser KF, Knapp PE: Morphine potentiates neurodegenerative effects of HIV-1 Tat through actions at μ-opioid receptor-expressing glia. Brain 2011, 134:3616–3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fitting S, Scoggins KL, Xu R, Dever SM, Knapp PE, Dewey WL, Hauser KF: Morphine efficacy is altered in conditional HIV-1 Tat transgenic mice. Eur J Pharmacol 2012, 689:96–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fitting S, Stevens DL, Khan FA, Scoggins KL, Enga RM, Beardsley PM, Knapp PE, Dewey WL, Hauser KF: Morphine tolerance and physical dependence are altered in conditional HIV-1 Tat transgenic mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2016, 356:96–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hahn YK, Paris JJ, Lichtman AH, Hauser KF, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Knapp PE: Central HIV-1 Tat exposure elevates anxiety and fear conditioned responses of male mice concurrent with altered mu-opioid receptor-mediated G-protein activation and β-arrestin 2 activity in the forebrain. Neurobiol Dis 2016, 92:124–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gonek M, McLane VD, Stevens DL, Lippold K, Akbarali HI, Knapp PE, Dewey WL, Hauser KF, Paris JJ: CCR5 mediates HIV-1 Tat-induced neuroinflammation and influences morphine tolerance, dependence, and reward. Brain Behav Immun 2018, 69:124–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim S, Hahn YK, Podhaizer EM, McLane VD, Zou S, Hauser KF, Knapp PE: A central role for glial CCR5 in directing the neuropathological interactions of HIV-1 Tat and opiates. J Neuroinflammation 2018, 15:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Xu AH, Yang Y, Sun YX, Zhang CD: Exogenous brain-derived neurotrophic factor attenuates cognitive impairment induced by okadaic acid in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res 2018, 13:2173–2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Braschi C, Capsoni S, Narducci R, Poli A, Sansevero G, Brandi R, Maffei L, Cattaneo A, Berardi N: Intranasal delivery of BDNF rescues memory deficits in AD11 mice and reduces brain microgliosis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021, 33:1223–1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Vitaliano GD, Kim JK, Kaufman MJ, Adam CW, Zeballos G, Shanmugavadivu A, Subburaju S, McLaughlin JP, Lukas SE, Vitaliano F: Clathrin-nanoparticles deliver BDNF to hippocampus and enhance neurogenesis, synaptogenesis and cognition in HIV/neuroAIDS mouse model. Commun Biol 2022, 5:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee KY, Ratte S, Prescott SA: Excitatory neurons are more disinhibited than inhibitory neurons by chloride dysregulation in the spinal dorsal horn. Elife 2019, 8:e49753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tang BL: The expanding therapeutic potential of neuronal KCC2. Cells 2020, 9:240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 87. Barbour AJ, Hauser KF, McQuiston AR, Knapp PE: HIV and opiates dysregulate K+-Cl− cotransporter 2 (KCC2) to cause GABAergic dysfunction in primary human neurons and Tat-transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis 2020, 141:104878. This study reveals that exposure to infectious HIV, Tat, gp120 and/or morphine decrease KCC2-expression and inhibitory (GABAergic) currents, while increasing excitation in human neurons in vitro. Tat-dependent KCC2 and motor deficits are also shown in transgenic mice. Both the in vitro and motor deficits in vivo are restored following treatment with drugs that enhance KCC2 function.

- 88.Taylor AM, Castonguay A, Ghogha A, Vayssiere P, Pradhan AA, Xue L, Mehrabani S, Wu J, Levitt P, Olmstead MC, et al. : Neuroimmune regulation of GABAergic neurons within the ventral tegmental area during withdrawal from chronic morphine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41:949–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ferrini F, Trang T, Mattioli TA, Laffray S, Del’Guidice T, Lorenzo LE, Castonguay A, Doyon N, Zhang W, Godin AG, et al. : Morphine hyperalgesia gated through microglia-mediated disruption of neuronal Cl(−) homeostasis. Nat Neurosci 2013, 16:183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Patel DC, Thompson EG, Sontheimer H: Brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits the function of cation-chloride cotransporter in a mouse model of viral infection-induced epilepsy. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10:961292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ** 91. Pozzi D, Rasile M, Corradini I, Matteoli M: Environmental regulation of the chloride transporter KCC2: switching inflammation off to switch the GABA on? Transl Psychiatry 2020, 10:349. This review examines the role of NKCC1 and KCC2 Cl− cotransporters in the excitatory-to-inhibitory GABA switch and discuss how imbalances in these cotransporters may contribute to autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, epilepsy, and post-traumatic stress disorder among others. The authors also discuss how specific inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, can dysregulate NKCC1 and KCC2.

- 92.Zhang D, Yang Y, Yang Y, Liu J, Zhu T, Huang H, Zhou C: Severe inflammation in newborns induces long-term cognitive impairment by activation of IL-1β/KCC2 signaling during early development. BMC Med 2022, 20:235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pozzi D, Menna E, Canzi A, Desiato G, Mantovani C, Matteoli M: The Communication Between the Immune and Nervous Systems: The role of IL-1β in synaptopathies. Front Mol Neurosci 2018, 11:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Corradini I, Focchi E, Rasile M, Morini R, Desiato G, Tomasoni R, Lizier M, Ghirardini E, Fesce R, Morone D, et al. : Maternal immune activation delays excitatory-to-inhibitory gamma-aminobutyric acid switch in offspring. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 83:680–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang ZH, Xiang J, Liu X, Yu SP, Manfredsson FP, Sandoval IM, Wu S, Wang JZ, Ye K: Deficiency in BDNF/TrkB neurotrophic activity stimulates delta-secretase by upregulating C/EBPbeta in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep 2019, 28:655–669 e655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lam P, Vinnakota C, Guzman BC, Newland J, Peppercorn K, Tate WP, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RLM, Kwakowsky A: Beta-Amyloid (Abeta1–42) Increases the Expression of NKCC1 in the Mouse Hippocampus. Molecules 2022, 27:2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bie B, Wu J, Lin F, Naguib M, Xu J: Suppression of hippocampal GABAergic transmission impairs memory in rodent models of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur J Pharmacol 2022, 917:174771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Machelska H, Celik MO: Opioid receptors in immune and glial cells-implications for pain control. Front Immunol 2020, 11:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Avey D, Sankararaman S, Yim AKY, Barve R, Milbrandt J, Mitra RD: Single-cell RNA-seq uncovers a robust transcriptional response to morphine by glia. Cell Rep 2018, 24:3619–3629 e3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maduna T, Audouard E, Dembele D, Mouzaoui N, Reiss D, Massotte D, Gaveriaux-Ruff C: Microglia express mu opioid receptor: insights from transcriptomics and fluorescent reporter mice. Front Psychiatry 2018, 9:726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O’Sullivan SJ, Malahias E, Park J, Srivastava A, Reyes BAS, Gorky J, Vadigepalli R, Van Bockstaele EJ, Schwaber JS: Single-cell glia and neuron gene expression in the central amygdala in opioid withdrawal suggests inflammation with correlated gut dysbiosis. Front Neurosci 2019, 13:665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Stiene-Martin A, Zhou R, Hauser KF: Regional, developmental, and cell cycle-dependent differences in μ, δ, and κ-opioid receptor expression among cultured mouse astrocytes. Glia 1998, 22:249–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]