Abstract

Quantum chemistry is a promising application for noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices. However, quantum computers have thus far not succeeded in providing solutions to problems of real scientific significance, with algorithmic advances being necessary to fully utilize even the modest NISQ machines available today. We discuss a method of ground state energy estimation predicated on a partitioning of the molecular Hamiltonian into two parts: one that is noncontextual and can be solved classically, supplemented by a contextual component that yields quantum corrections obtained via a Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) routine. This approach has been termed Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE); however, there are obstacles to overcome before it can be deployed on NISQ devices. The problem we address here is that of the ansatz, a parametrized quantum state over which we optimize during VQE; it is not initially clear how a splitting of the Hamiltonian should be reflected in the CS-VQE ansätze. We propose a “noncontextual projection” approach that is illuminated by a reformulation of CS-VQE in the stabilizer formalism. This defines an ansatz restriction from the full electronic structure problem to the contextual subspace and facilitates an implementation of CS-VQE that may be deployed on NISQ devices. We validate the noncontextual projection ansatz using a quantum simulator and demonstrate chemically precise ground state energy calculations for a suite of small molecules at a significant reduction in the required qubit count and circuit depth.

1. Introduction

Quantum computers promise to yield solutions to complex problems that have previously been unattainable by classical means, yet experimental demonstration remains challenging. To date, some of the largest molecules simulated on noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) hardware are H12–albeit only a Hartree–Fock calculation–conducted by Google using just 12 of the 53 qubits available on their superconducting quantum processor Sycamore,1 and H2O performed independently by IonQ using 3 qubits of an unspecified proprietary trapped ion device2 and by IBM using 5 of the 27 qubits on the now-decommissioned ibmq_dublin superconducting device.3

Due to the limitations of short coherence times, restrictive qubit connectivity and high noise floors that characterize the NISQ era, we are not able to harness the full state-space afforded to these machines. To circumvent the above issues, we turn to the class of variational quantum algorithms, of which the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE)4 is most widely studied. In contrast with eigenvalue-finding algorithms requiring fault-tolerant machines such as Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE),5 which necessitates state evolution over an extended period of coherence, VQE executes a large ensemble of comparatively shallow parametrized circuits to estimate energy expectation values, informing a classical optimizer that updates the parameter settings before reinitialization of the quantum circuit. Its success is predicated on the variational principle, meaning the ground state energy of the system bounds expectation values from below.6

However, VQE is not without its challenges. First of all, the parametrized quantum state mentioned above, known as an ansatz, needs to be constructed carefully: It must be sufficiently expressible so the subspace of quantum states it spans contains the true ground state. On the other hand, if the ansatz is too expressible, we run into the problem of barren plateaus7 where we observe vanishing gradients. This is more often a symptom of “hardware efficient” ansätze,1,8−12 which aim to access the largest possible region of Hilbert space for the fewest number of native quantum gates.

To avoid barren plateaus, one must take into account some of the underlying problem structure to define ansatz circuits whose images are confined to a smaller but more targeted region of Hilbert space. Within this category are “chemically inspired” ansätze that represent sequences of electronic excitation operators in circuit; unitary coupled cluster (UCC)13,14 is widely acknowledged as the gold standard for electronic structure simulations, albeit computationally very expensive in practice.

More recently, we have seen the development of hybrid ansätze that bridge the gap between hardware efficiency and chemical motivation. For example, Gard et al.15 designed a compact circuit designed to conserve molecule symmetries such as particle number and spin, while Adaptive Derivative-Assembled Pseudo-Trotter (ADAPT) VQE16−19 describes a more complete approach to scalable quantum chemistry simulations by defining selection criteria of ansatz terms from a pool of excitation operators.

Second, the energy estimation procedure in VQE invokes the measurement problem; in order to mitigate statistical error, many prepare-and-measure cycles are necessary to achieve sufficient precision in the estimate. The advances made in recent years toward measurement reduction techniques are expansive20−29 and range from classical pre/postprocessing of the measurement information, such as in classical shadow tomography,30,31 to Hamiltonian term-grouping schemes and reductions in the number of Hamiltonian terms at a cost of coherent resource, such as in unitary partitioning.32−36 Combined with techniques of error mitigation,37−44 one can optimize VQE with the objective of maximal NISQ resource utilization.

In this work, we are concerned with Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE),45 which describes a method of partitioning the molecular Hamiltonian into disjoint parts so that an electronic structure problem may be simulated to some degree on the available quantum device, even when the dimension of the full problem is too great to be encoded on the number of qubits available. This is supplemented by some classical overhead, but this often permits one to achieve chemical precision (to within 1.6 mHa ≈ 4 kJ/mol of the full configuration interaction (FCI) energy) at a saving of qubits, as indicated by Kirby et al.45 We highlight the relevance of chemical precision over accuracy here; since a minimal basis set (STO-3G) will be used throughout our benchmark, one should not expect agreement with experimentally obtained molecular energies and thus chemical accuracy is not an appropriate phrase. A finer basis set such as cc-pVxZ where x = D, T, Q, etc. should be used if one wishes to assess accuracy; however, this comes at the cost of increased qubits.

There has since

been further research into the use of classical

estimates of the electronic structure problem to reduce the resource

requirements on quantum hardware. In particular, Classically Boosted

VQE (CB-VQE)46 identifies classically tractable

states and excludes them from the quantum simulation, alleviating

some measurement and fidelity requirements of the VQE routine. CS-VQE

also bears a resemblance to the qubit reduction technique of qubit

tapering,47,48 which exploits  symmetries of the Hamiltonian; the differences

and similarities are highlighted herein and by Kirby et al.45

symmetries of the Hamiltonian; the differences

and similarities are highlighted herein and by Kirby et al.45

There are still a number of problems to address before CS-VQE may be successfully deployed on real quantum hardware, most notably with regard to the ansatz, which is the principal focus of this work. To aid this objective, we place the method on a strong theoretical footing of stabilizer subspaces and projections therein; this reformulation is better suited to efficient implementation, which is being addressed through the Symmer project.49 This rephrasing of CS-VQE illuminates the matter of constructing ansätze for the contextual subspace and renders this method compatible with contemporary approaches to ansatz construction such as ADAPT-VQE.

2. Preliminaries

The notation used throughout shall be to write operators in standard capital font (A, B, C, etc.), with the exception of single-qubit Pauli operators being written in the form

| 1 |

for p ∈ {0, 1, 2,

3}. Sets are denoted by script letters  and vector spaces by bold script typeface

and vector spaces by bold script typeface  . The state space of N qubits

may be identified with the 2N dimensional

Hilbert space

. The state space of N qubits

may be identified with the 2N dimensional

Hilbert space  , with the space of (bounded) linear operators

acting upon

, with the space of (bounded) linear operators

acting upon  denoted

denoted  .

.

We introduce the Pauli group,  , consisting of operators

, consisting of operators  for pi ∈ {0, 1, 2, 3}, up to multiplication by ±1, ±i. Note the distinction between the bold font σ denoting tensor products and σp a single-qubit Pauli operator; we will sometimes write

for pi ∈ {0, 1, 2, 3}, up to multiplication by ±1, ±i. Note the distinction between the bold font σ denoting tensor products and σp a single-qubit Pauli operator; we will sometimes write  to index explicitly the qubit position

to index explicitly the qubit position  on which it acts. We shall also make use

of the commutator [A, B] ≔ AB – BA and anticommutator {A, B}

≔ AB + BA, defined for operators

on which it acts. We shall also make use

of the commutator [A, B] ≔ AB – BA and anticommutator {A, B}

≔ AB + BA, defined for operators  , which are zero when A and B commute/anticommute, respectively.

, which are zero when A and B commute/anticommute, respectively.

An N-qubit Hamiltonian can be written in the form

| 2 |

for a set of Pauli operators  ; specifying real coefficients ensures that

; specifying real coefficients ensures that  is Hermitian. The objective

of quantum chemistry simulations is to estimate the ground state energy

is Hermitian. The objective

of quantum chemistry simulations is to estimate the ground state energy

| 3 |

where  is the expectation value of

is the expectation value of  with respect to some quantum state

with respect to some quantum state  . Many physical properties of the target

system are determined by the ground state, motivating this goal.

. Many physical properties of the target

system are determined by the ground state, motivating this goal.

The Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) quantum–classical

hybrid algorithm4 is the most widely studied

means of achieving this on NISQ hardware. VQE requires a parametrized

ansatz state,  , whose parameters θ are

manipulated within a classical optimization scheme that aims to minimize

the energy expectation value

, whose parameters θ are

manipulated within a classical optimization scheme that aims to minimize

the energy expectation value

| 4 |

evaluated via many prepare-and-measure cycles. The choice of ansatz restricts us to a subspace of quantum states and therefore must be carefully designed to be sufficiently expressible so as to capture the true ground state of the system.

A common form of ansatz state, particularly in relation to the electronic structure problem, is

| 5 |

where  is some fixed reference state in which

the quantum circuit is initialized and

is some fixed reference state in which

the quantum circuit is initialized and  for parameters

for parameters  and Pauli operators

and Pauli operators  ; the unitary eiA(θ) effects excitations above the reference state.

Such ansätze as unitary coupled cluster (UCC)13,14 may by expressed by our choice of A (taking as

reference the Hartree–Fock state), in addition to any others

based on the theory of excitation operators such as ADAPT-VQE.16−19 The quantum advantage in VQE stems from the ability to prepare classically

intractable states from our parametrized ansatz circuits.

; the unitary eiA(θ) effects excitations above the reference state.

Such ansätze as unitary coupled cluster (UCC)13,14 may by expressed by our choice of A (taking as

reference the Hartree–Fock state), in addition to any others

based on the theory of excitation operators such as ADAPT-VQE.16−19 The quantum advantage in VQE stems from the ability to prepare classically

intractable states from our parametrized ansatz circuits.

3. Projections onto Stabilizer Subspaces

Given an operator  , the space of quantum states

, the space of quantum states  that it stabilizes are those satisfying σ|ψ⟩ = |ψ⟩, the +1-eigenspace

of σ. Extending this notion to an Abelian subgroup

of Pauli operators

that it stabilizes are those satisfying σ|ψ⟩ = |ψ⟩, the +1-eigenspace

of σ. Extending this notion to an Abelian subgroup

of Pauli operators  , there is an induced vector space

, there is an induced vector space  of states stabilized by the elements of

of states stabilized by the elements of  .

.

A particularly useful definition

is that of a Hamiltonian symmetry, taken here to

mean a set  of Pauli operators such that

of Pauli operators such that

| 6 |

In other words, a symmetry of  is any set of Pauli operators that commute

universally among

is any set of Pauli operators that commute

universally among  , which we may extend to an Abelian group

, which we may extend to an Abelian group  , the closure of

, the closure of  under operator multiplication, which we

shall call a symmetry group.

under operator multiplication, which we

shall call a symmetry group.

Note the setting

in which we present symmetries here is stricter

than the conventional definition, which considers any operator S that commutes with the Hamiltonian, i.e.,  , to be a symmetry. Such an operator need

not commute with the individual terms as we require here. For example,

in the Fermionic picture, the number operator

, to be a symmetry. Such an operator need

not commute with the individual terms as we require here. For example,

in the Fermionic picture, the number operator  (where a is the Fermionic

annihilation operator and its Hermitian conjugate a† represents the creation operator) commutes with

the full second-quantized molecular Hamiltonian, but not with an arbitrary

excitation term.

(where a is the Fermionic

annihilation operator and its Hermitian conjugate a† represents the creation operator) commutes with

the full second-quantized molecular Hamiltonian, but not with an arbitrary

excitation term.

The operators of  will in general be algebraically dependent,

but the theory of stabilizers50 ensures

the existence of a set of independent generators

will in general be algebraically dependent,

but the theory of stabilizers50 ensures

the existence of a set of independent generators  such that

such that  . Now, recall that the Clifford group consists

of unitary operators

. Now, recall that the Clifford group consists

of unitary operators  (meaning

(meaning  ) with the property

) with the property  , i.e., U normalizes the

Pauli group. We may construct a Clifford operation U mapping each symmetry generator to distinct single-qubit Pauli operators

σp, where we are free to choose p ∈ {1, 2, 3}. More precisely, there exists a subset

of qubit positions

, i.e., U normalizes the

Pauli group. We may construct a Clifford operation U mapping each symmetry generator to distinct single-qubit Pauli operators

σp, where we are free to choose p ∈ {1, 2, 3}. More precisely, there exists a subset

of qubit positions  satisfying

satisfying  and a bijective map

and a bijective map  such that

such that

| 7 |

This is a powerful concept that provides a mechanism for reducing the number of qubits in the Hamiltonian while preserving its energy spectrum. This is at the core of qubit tapering,47,48 in which it is observed that

| 8 |

implying the rotated Hamiltonian  consists solely of identity or Pauli σp operators in the qubit positions indexed

by

consists solely of identity or Pauli σp operators in the qubit positions indexed

by  . Taking expectation values, one may replace

the qubits

. Taking expectation values, one may replace

the qubits  by their eigenvalues νi = ±1; each assignment

by their eigenvalues νi = ±1; each assignment

| 9 |

defines a symmetry sector and at least one such sector will contain the true solution to the eigenvalue problem. Note the other sectors still have physical significance and may, for example, relate to solutions with different particle numbers or to excited states. Ancillary data files are provided in which we report the symmetry generators and corresponding sector for the Hamiltonians representing the molecular systems listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Systems Investigated to Benchmark the Noncontextual Projection Ansatza.

| molecular

systems |

number

of qubits |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | charge | mult. | full | taper | CS-VQEb |

| Be | 0 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| B | 0 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| LiH | 0 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 4 |

| BeH | +1 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 6 |

| HF | 0 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 4 |

| BeH2 | 0 | 1 | 14 | 9 | 7 |

| H2O | 0 | 1 | 14 | 10 | 7 |

| F2 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 16 | 10 |

| HCl | 0 | 1 | 20 | 17 | 4 |

All in the STO-3G basis.

Indicates the fewest number of qubits required to achieve chemical precision.

A quantum state consistent with any such sector must

be stabilized

by the operators  , and we may define a projection onto the

corresponding stabilizer subspace. In general, a projection is defined

to be an idempotent operator

, and we may define a projection onto the

corresponding stabilizer subspace. In general, a projection is defined

to be an idempotent operator  , i.e., P2 = P; the projection onto the ±1-eigenspace of a single-qubit

Pauli operator σp for p ∈ {1, 2, 3} may be written

, i.e., P2 = P; the projection onto the ±1-eigenspace of a single-qubit

Pauli operator σp for p ∈ {1, 2, 3} may be written

| 10 |

States with no component inside the chosen eigenspace are mapped to zero and observe that

| 11 |

for q ∈ {1, 2, 3}.

Let  be the reduced Hilbert space supported

by the stabilized qubits

be the reduced Hilbert space supported

by the stabilized qubits  and

and  its complement such that

its complement such that  . Given an assignment of eigenvalues

. Given an assignment of eigenvalues  , we may project onto the corresponding

sector via

, we may project onto the corresponding

sector via

|

12 |

and subsequently perform a partial

trace over the stabilized qubits  . This is effected by the unique linear

map

. This is effected by the unique linear

map  satisfying the property

satisfying the property  for all

for all  and

and  .

.

Finally, we may define the full stabilizer subspace projection map

| 13 |

which, using the linearity of Trstab, yields a reduced Hamiltonian

|

14 |

where  and we have written

and we have written  . The new coefficients

. The new coefficients  differ from hσ by a sign dependent on the chosen symmetry sector.

differ from hσ by a sign dependent on the chosen symmetry sector.

In qubit tapering, U is taken as eq 7 with the corresponding basis  a generating set for a full Hamiltonian

symmetry.47,48 Assuming identification of the correct sector,

the ground state energy of the

a generating set for a full Hamiltonian

symmetry.47,48 Assuming identification of the correct sector,

the ground state energy of the  -qubit reduced Hamiltonian

-qubit reduced Hamiltonian  will coincide with the true value of the

full system

will coincide with the true value of the

full system  .

.

This stabilizer projection procedure

is straightforward with respect

to the Hamiltonian, since the stabilized qubits contain only operators

with nonzero image under conjugation with Pν. However, suppose we were to take another observable  and wish to determine a reduced form on

and wish to determine a reduced form on  that is consistent with the reduced Hamiltonian

that is consistent with the reduced Hamiltonian  . This may be achieved by following precisely

the same process that was applied to

. This may be achieved by following precisely

the same process that was applied to  , but the symmetry

, but the symmetry  will not in general be a symmetry of A and therefore the “symmetry-breaking” terms

(those which anticommute with the generators

will not in general be a symmetry of A and therefore the “symmetry-breaking” terms

(those which anticommute with the generators  ) will vanish under projection onto the

stabilizer subspace, as per eq 11. Letting

) will vanish under projection onto the

stabilizer subspace, as per eq 11. Letting  be the set of terms in the Pauli-basis

expansion of A, observe that

be the set of terms in the Pauli-basis

expansion of A, observe that

|

15 |

recalling that qi indicates the type of single-qubit Pauli acting

on qubit position  in some tensor product σ, defined in Section 2.

in some tensor product σ, defined in Section 2.

The resulting form is identical to eq 14,

except we are explicit that the terms surviving projection are only

those whose qubit positions indexed by  consist exclusively of identity and Pauli

σp operators; this is trivially

true for the Hamiltonian by construction. Most importantly, this extends

the stabilizer subspace projection to ansätze defined on the

full system for use in variational algorithms. It should be noted

that the above operations are classically tractable and can be implemented

efficiently in the symplectic representation of Pauli operators.51,52

consist exclusively of identity and Pauli

σp operators; this is trivially

true for the Hamiltonian by construction. Most importantly, this extends

the stabilizer subspace projection to ansätze defined on the

full system for use in variational algorithms. It should be noted

that the above operations are classically tractable and can be implemented

efficiently in the symplectic representation of Pauli operators.51,52

It would be remiss of us not to draw attention to the likeness

of eq 13 to Positive Operator-Valued Measures

(POVMs);53 indeed, the projectors (eq 12) define a complete set of Kraus operators.54 The stabilizer subspace

projection procedure is reduced to a matter of enforcing a partial

measurement over some subsystem of the full problem, for which the

relevant outcomes have been determined via an auxiliary method. For

example, this could involve identifying a quantum state with a known

nonzero overlap with the true ground state; measuring the symmetry

generators  in this state will yield the correct sector.

in this state will yield the correct sector.

Hartree–Fock often provides such a state for electronic structure problems, although it is not immune to failure; this is particularly true in the strongly correlated regime. In these cases, we should defer to more effective reference states such as those obtained from Møller–Plesset perturbation theory (MP), coupled-cluster (CC) methods, and so on. One can imagine a hierarchy of increasingly precise ground state approximations, for which we should hope to obtain at some point a nonzero overlap with the true ground state.

4. CS-VQE in the Stabilizer Formalism

We now describe the Contextual Subspace VQE (CS-VQE) method in the stabilizer setting introduced in Section 3. CS-VQE partitions the Hamiltonian (2) into two disjoint components, one that is noncontextual and another that is contextual, which provides quantum corrections to the former via VQE.45 Explicitly, this allows us to write

| 16 |

where  is a noncontextual set of Pauli operators

and

is a noncontextual set of Pauli operators

and  is what remains, which will in general

be contextual.

is what remains, which will in general

be contextual.

CS-VQE differs from qubit tapering (described

in Section 3) in the

following way: the

latter exploits existing (i.e., physical) symmetries of the Hamiltonian,

whereas in CS-VQE, we impose additional “pseudosymmetries”

derived from the noncontextual Hamiltonian. This results in a loss

of information, since any terms of  not commuting with the symmetry generators

will vanish under projection.

not commuting with the symmetry generators

will vanish under projection.

4.1. The Noncontextual Problem

The notion

of contextuality goes back to the Bell–Kochen–Specker

theorem.55−57 Here we use an explicit condition for the noncontextuality

of a set of Pauli operators, developed by Kirby and Love58 and independently by Raussendorf et al.59 Strictly speaking, this condition tests for

strong measurement contextuality. In this setting, a set  is understood to be noncontextual if and

only if commutation forms an equivalence relation on

is understood to be noncontextual if and

only if commutation forms an equivalence relation on  , where we have defined the sub-Hamiltonian

symmetry

, where we have defined the sub-Hamiltonian

symmetry  . There is an implied structure

. There is an implied structure

| 17 |

where the  are equivalence classes with respect to

commutation–in other words, elements of the same class commute

and across classes they anticommute. Conversely, such a set of Pauli

operators is contextual if and only if commutation fails to be transitive

on

are equivalence classes with respect to

commutation–in other words, elements of the same class commute

and across classes they anticommute. Conversely, such a set of Pauli

operators is contextual if and only if commutation fails to be transitive

on  .

.

The symmetry  can be expanded by taking pairwise products

within equivalence classes, since {Ci, Cj} = 0 for

can be expanded by taking pairwise products

within equivalence classes, since {Ci, Cj} = 0 for  with i ≠ j, it is the case that

with i ≠ j, it is the case that  and we may define

and we may define  . As before, in Section 3,

. As before, in Section 3,  induces a symmetry group for which one

may define independent generators

induces a symmetry group for which one

may define independent generators  and a Clifford operation

and a Clifford operation  mapping the generators to single-qubit

Pauli operators; the expectation value over these qubits will again

be determined by an assignment

mapping the generators to single-qubit

Pauli operators; the expectation value over these qubits will again

be determined by an assignment  of eigenvalues, analogous to the selection

of a symmetry sector in qubit tapering.

of eigenvalues, analogous to the selection

of a symmetry sector in qubit tapering.

From each equivalence

class  , we select a representative Ci and construct an observable

, we select a representative Ci and construct an observable  where

where  and |r| = 1. Kirby and Love60 found that quantum states

and |r| = 1. Kirby and Love60 found that quantum states  stabilized by the operators

stabilized by the operators  are consistent with a classical objective

function η(ν, r) (derived in

the Supporting Information), in the sense

that η(ν, r) coincides with

the noncontextual energy expectation value

are consistent with a classical objective

function η(ν, r) (derived in

the Supporting Information), in the sense

that η(ν, r) coincides with

the noncontextual energy expectation value  for all parametrizations (ν, r). This is a consequence of the joint probability

distribution chosen over the phase-space points of their (epistricted)

model.60,61

for all parametrizations (ν, r). This is a consequence of the joint probability

distribution chosen over the phase-space points of their (epistricted)

model.60,61

The noncontextual energy spectrum is therefore parametrized by two vectors: the ±1 eigenvalue assignments ν, determining the contribution of the universally commuting terms, and r, encapsulating the remaining pairwise anticommuting classes. In this sense, we may refer to (ν, r) as a state of the noncontextual Hamiltonian itself, abstracted from quantum states of the corresponding stabilizer subspace. Optimizing over these parameters, we obtain the noncontextual ground state energy

| 18 |

and call an element (ν, r) of the preimage  a noncontextual ground state of

a noncontextual ground state of  . Let us denote by

. Let us denote by  the absolute error with respect to the

true ground state energy.

the absolute error with respect to the

true ground state energy.

As a classical estimate to the ground

state energy of the full

Hamiltonian  , in Section 5, we found the difference between the noncontextual

ground state and Hartree–Fock energy to be negligible for each

of the molecules simulated, since the heuristic used to choose

, in Section 5, we found the difference between the noncontextual

ground state and Hartree–Fock energy to be negligible for each

of the molecules simulated, since the heuristic used to choose  prioritizes diagonal Hamiltonian terms.

In principle, it may be an improvement upon Hartree–Fock as

the noncontextual set can also take into account an off-diagonal contribution

within the anticommuting classes. This is highly dependent on the

chosen form of noncontextual set; a reformulation in terms of graphs,

e.g., representing Pauli operators as nodes with (non)adjacency indicating

(anti)commutation, will allow one to identify what the equivalent

problem(s) are in computer science and therefore draw upon the vast

body of existing research and select the best algorithms designed

to solve such computational problems of graph theory. It should be

noted that the “optimal” noncontextual subset will not

necessarily be that which minimizes the noncontextual ground state

energy and some consideration of the resulting quantum corrections

must inform this choice, which remains an open question.

prioritizes diagonal Hamiltonian terms.

In principle, it may be an improvement upon Hartree–Fock as

the noncontextual set can also take into account an off-diagonal contribution

within the anticommuting classes. This is highly dependent on the

chosen form of noncontextual set; a reformulation in terms of graphs,

e.g., representing Pauli operators as nodes with (non)adjacency indicating

(anti)commutation, will allow one to identify what the equivalent

problem(s) are in computer science and therefore draw upon the vast

body of existing research and select the best algorithms designed

to solve such computational problems of graph theory. It should be

noted that the “optimal” noncontextual subset will not

necessarily be that which minimizes the noncontextual ground state

energy and some consideration of the resulting quantum corrections

must inform this choice, which remains an open question.

4.2. Quantum Corrections

Our simulation

approach has thus far been strictly classical–now we arrive

at the quantum element of CS-VQE. We have derived a classical estimate

of the ground state energy from the noncontextual part of the Hamiltonian  ; however, the contextual component

; however, the contextual component  has so far been neglected.

has so far been neglected.

While C(r) is not a stabilizer in the strict sense

(it is not an element of the Pauli group), it is unitarily equivalent

to one as a linear combination of anticommuting Pauli elements. Similar

to the symmetry generators  , it is possible to define a unitary operation UC mapping C(r) onto a single-qubit Pauli operator, following the

approach of unitary partitioning.32−36 However, unlike the

, it is possible to define a unitary operation UC mapping C(r) onto a single-qubit Pauli operator, following the

approach of unitary partitioning.32−36 However, unlike the  rotation,

rotation,  is not Clifford as it collapses M terms onto a single Pauli operator and can therefore introduce

additional terms to the Hamiltonian. Kirby et al.45 cautioned that, in principle, this increase in Hamiltonian

complexity could be exponential in the number of equivalence classes M, namely, a scaling of

is not Clifford as it collapses M terms onto a single Pauli operator and can therefore introduce

additional terms to the Hamiltonian. Kirby et al.45 cautioned that, in principle, this increase in Hamiltonian

complexity could be exponential in the number of equivalence classes M, namely, a scaling of  . However, Ralli et al.36 demonstrated that the general scaling for this sequence

of rotations (SeqRot) method is

. However, Ralli et al.36 demonstrated that the general scaling for this sequence

of rotations (SeqRot) method is  where x ∈ [1, 2];

that is, still exponential, yet the necessary conditions to obtain

the worst-case x = 2 are contrived and have not been

observed for any molecular Hamiltonians investigated to date. Regardless,

one may circumvent this potentially adverse scaling entirely by implementing

the linear combination of unitaries (LCU) approach to unitary partitioning,33,35 which is only quadratic in the number of equivalence classes

where x ∈ [1, 2];

that is, still exponential, yet the necessary conditions to obtain

the worst-case x = 2 are contrived and have not been

observed for any molecular Hamiltonians investigated to date. Regardless,

one may circumvent this potentially adverse scaling entirely by implementing

the linear combination of unitaries (LCU) approach to unitary partitioning,33,35 which is only quadratic in the number of equivalence classes  .36

.36

Appending C(r) to our set of generators  and defining

and defining  , there exists a subset of qubit indices

, there exists a subset of qubit indices  satisfying

satisfying  and a bijective map

and a bijective map  such that

such that  for each

for each  . We reiterate that p ∈

{1, 2, 3} may be chosen at will; the approach taken by Kirby et al.45 is to select p = 3 to enforce

diagonal generators.

. We reiterate that p ∈

{1, 2, 3} may be chosen at will; the approach taken by Kirby et al.45 is to select p = 3 to enforce

diagonal generators.

Suppose we have a quantum state |ψ(ν,r)⟩ that is consistent

with  ; since the rotated state

; since the rotated state  must be stabilized by

must be stabilized by  , the qubit positions

, the qubit positions  must be fixed. This implies a decomposition

must be fixed. This implies a decomposition

| 19 |

where |b(ν,r)⟩ represents a single basis state of  and

and  is independent of the parameters (ν, r). The expectation value of the full

Hamiltonian may be expressed as

is independent of the parameters (ν, r). The expectation value of the full

Hamiltonian may be expressed as

| 20 |

where  contains only the terms of the contextual

Hamiltonian that commute with all the noncontextual generators, just

as in eq 15. It was observed by Kirby et al.45 that any term which anticommutes with at least

one noncontextual generator must have zero expectation value, and

our stabilizer subspace projection captures this fact.

contains only the terms of the contextual

Hamiltonian that commute with all the noncontextual generators, just

as in eq 15. It was observed by Kirby et al.45 that any term which anticommutes with at least

one noncontextual generator must have zero expectation value, and

our stabilizer subspace projection captures this fact.

Inspecting

eq 20, we may optimize freely

over quantum states φ, i.e., we are not constrained by the noncontextual

ground state within  . In fact, we may absorb the noncontextual

ground state energy into the reduced contextual Hamiltonian

. In fact, we may absorb the noncontextual

ground state energy into the reduced contextual Hamiltonian

| 21 |

defining the contextual subspace Hamiltonian; this form is obtained naturally when applying the stabilizer subspace projection to the full Hamiltonian, which automatically includes the noncontextual energy by fixing the corresponding eigenvalue assignments.

Now, we may perform unconstrained VQE to obtain a quantum-corrected estimate

| 22 |

of the true ground state energy with absolute

error  . We have equality when the stabilizers

span every qubit position, which is the case when

. We have equality when the stabilizers

span every qubit position, which is the case when  since the generators must be algebraically

independent: this means the initial quantum correction is trivial

as the noncontextual part determines the entire system.

since the generators must be algebraically

independent: this means the initial quantum correction is trivial

as the noncontextual part determines the entire system.

For

instances of the electronic structure problem, there is no

guarantee that  will achieve chemical precision (Δc < 1.6 mHa ≈ 4 kJ/mol) and, indeed, it might not

improve upon the noncontextual estimate (although it will never be

worse, due to the variational principle applying in this case). However,

one can easily define a subset of

will achieve chemical precision (Δc < 1.6 mHa ≈ 4 kJ/mol) and, indeed, it might not

improve upon the noncontextual estimate (although it will never be

worse, due to the variational principle applying in this case). However,

one can easily define a subset of  that is again noncontextual; this is achieved

by discarding one of the noncontextual generators

that is again noncontextual; this is achieved

by discarding one of the noncontextual generators  , along with the operators that it generates.

We now append the discarded operators to the contextual Hamiltonian,

relaxing the stabilizer constraint on the qubit position f(G) and permitting a search over its Hilbert space.

This process may be iterated until the noncontextual set is exhausted

and we recover full VQE. This means that, unless the ground state

energy of

, along with the operators that it generates.

We now append the discarded operators to the contextual Hamiltonian,

relaxing the stabilizer constraint on the qubit position f(G) and permitting a search over its Hilbert space.

This process may be iterated until the noncontextual set is exhausted

and we recover full VQE. This means that, unless the ground state

energy of  and H coincides, CS-VQE

will improve upon the noncontextual energy using less quantum resources

than full VQE; this is more rigorously defined in the next section.

and H coincides, CS-VQE

will improve upon the noncontextual energy using less quantum resources

than full VQE; this is more rigorously defined in the next section.

In summary, what we have described here is a technique of scaling the relative sizes of the noncontextual (read classical) and contextual (read quantum) simulations in a reciprocal manner. We can therefore trade-off quantum and classical workloads in CS-VQE.

4.3. Expanding the Contextual Subspace

Now we describe the process of growing the contextual subspace more

rigorously. We select a subset of noncontextual generators  whose stabilizer constraints we mean to

enforce and construct a new noncontextual set

whose stabilizer constraints we mean to

enforce and construct a new noncontextual set  ; the contextual set is expanded accordingly

by appending the terms not generated by

; the contextual set is expanded accordingly

by appending the terms not generated by  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  . As before, there exists a unitary operation

. As before, there exists a unitary operation  , a subset of qubit indices

, a subset of qubit indices  , and a bijective map

, and a bijective map  satisfying

satisfying  (the rotation

(the rotation  may or may not be Clifford depending on

whether C(r) is among the stabilizers

we wish to fix).

may or may not be Clifford depending on

whether C(r) is among the stabilizers

we wish to fix).

Denote by  the ground state energy of the new noncontextual

Hamiltonian

the ground state energy of the new noncontextual

Hamiltonian  with absolute error

with absolute error  . While this is weaker as an estimate of

the true ground state energy of the full system, at the very least

we are guaranteed to recover the initial noncontextual ground state

energy from performing a simulation of the expanded contextual subspace,45 which we describe below.

. While this is weaker as an estimate of

the true ground state energy of the full system, at the very least

we are guaranteed to recover the initial noncontextual ground state

energy from performing a simulation of the expanded contextual subspace,45 which we describe below.

The stabilizer

constraints of  are enforced over the Hilbert space

are enforced over the Hilbert space  of qubits indexed by

of qubits indexed by  , whereas we may perform a VQE simulation

over

, whereas we may perform a VQE simulation

over  , the Hilbert space of the remaining

, the Hilbert space of the remaining  qubits indexed by

qubits indexed by  . Invoking the stabilizer subspace projection

map

. Invoking the stabilizer subspace projection

map  with the eigenvalue assignments

with the eigenvalue assignments  yields an expanded contextual subspace

Hamiltonian

yields an expanded contextual subspace

Hamiltonian

| 23 |

Performing an  -qubit VQE simulation over the contextual

subspace, we obtain a new quantum-corrected estimate

-qubit VQE simulation over the contextual

subspace, we obtain a new quantum-corrected estimate

| 24 |

with an error satisfying  . Recall that

. Recall that  corresponds with the contextual error when

we enforce the full set of noncontextual stabilizers.

corresponds with the contextual error when

we enforce the full set of noncontextual stabilizers.

Observe

that, when  , we are simply performing full VQE over

the entire system; this occurs when we do not enforce the stabilizer

constraint for any of the noncontextual generators, i.e.,

, we are simply performing full VQE over

the entire system; this occurs when we do not enforce the stabilizer

constraint for any of the noncontextual generators, i.e.,  . Therefore, it must be the case that

. Therefore, it must be the case that

| 25 |

Furthermore, given a nested sequence of generator

subsets  with

with  , then

, then  and the convergence is monotonic. In this

way, CS-VQE describes an interpolation between a purely classical

estimate of the ground state energy and a full VQE simulation of the

Hamiltonian. In the context of electronic structure calculations,

this often permits one to achieve chemical precision at a saving of

qubit resources, as indicated by Kirby et al.45 for a suite of tapered test molecules of up to 18 qubits. We note

in eq 25 that the quality of the chosen ansatz

and optimization procedure will limit the actual error one may achieve

in practice. This statement instead indicates that, for an appropriate

level of contextual subspace approximation, it is possible to construct

a reduced Hamiltonian whose exact ground state lies within some error

threshold of the true value.

and the convergence is monotonic. In this

way, CS-VQE describes an interpolation between a purely classical

estimate of the ground state energy and a full VQE simulation of the

Hamiltonian. In the context of electronic structure calculations,

this often permits one to achieve chemical precision at a saving of

qubit resources, as indicated by Kirby et al.45 for a suite of tapered test molecules of up to 18 qubits. We note

in eq 25 that the quality of the chosen ansatz

and optimization procedure will limit the actual error one may achieve

in practice. This statement instead indicates that, for an appropriate

level of contextual subspace approximation, it is possible to construct

a reduced Hamiltonian whose exact ground state lies within some error

threshold of the true value.

Suppose we wish to find the optimal

contextual subspace Hamiltonian

of size N′ < N. The problem

reduces to minimizing the error  over the

over the  generator subsets

generator subsets  satisfying

satisfying  . CS-VQE is highly sensitive to this choice

and remains a vital open question for the continued success of the

technique. For chemistry applications, we grow the contextual subspace

until the CS-VQE error attains chemical precision, which means finding

the minimal

. CS-VQE is highly sensitive to this choice

and remains a vital open question for the continued success of the

technique. For chemistry applications, we grow the contextual subspace

until the CS-VQE error attains chemical precision, which means finding

the minimal  such that

such that  < 1.6 mHa. In general, we will not have

access to a target energy and so will not necessarily know when the

desired precision is achieved; instead, we might choose the largest

contextual subspace accommodated by the available quantum resource

or iterate until the VQE convergence is within some fixed bound.

< 1.6 mHa. In general, we will not have

access to a target energy and so will not necessarily know when the

desired precision is achieved; instead, we might choose the largest

contextual subspace accommodated by the available quantum resource

or iterate until the VQE convergence is within some fixed bound.

Greedily selecting combinations of d ≤ N generators that yield the greatest reduction in error

is an effective stabilizer relaxation ordering heuristic, where iterating k < N/d involves a

search of depth d over N–dk elements, thus necessitating  CS-VQE simulations. Taking d = 2 produces a good balance between efficiency and efficacy,45 but there is room for more targeted approaches

that exploit some structure of the underlying problem. For example,

in quantum chemistry problems, it could be that one should relax the

stabilizers that have nontrivial action near the Fermi level, between

the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied

molecular orbital (LUMO). Excitations clustered around this gap are

more likely to appear in the true ground state and should therefore

not be assigned definite values under the noncontextual projection.

This idea comes from the theory of pseudopotential approximations,62 in which it is observed that chemically relevant

electrons are predominantly those of the valence space, whereas the

core may be “frozen”, thus reducing the electronic complexity.

CS-VQE simulations. Taking d = 2 produces a good balance between efficiency and efficacy,45 but there is room for more targeted approaches

that exploit some structure of the underlying problem. For example,

in quantum chemistry problems, it could be that one should relax the

stabilizers that have nontrivial action near the Fermi level, between

the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied

molecular orbital (LUMO). Excitations clustered around this gap are

more likely to appear in the true ground state and should therefore

not be assigned definite values under the noncontextual projection.

This idea comes from the theory of pseudopotential approximations,62 in which it is observed that chemically relevant

electrons are predominantly those of the valence space, whereas the

core may be “frozen”, thus reducing the electronic complexity.

Alternatively, one might define a Hamiltonian term-importance metric that considers coefficient magnitudes63 or second-order response with respect to a perturbation of the Hartree–Fock state.64 In relation to this, it is also not clear which features of a molecular system mean that it might be more or less amenable to CS-VQE; additional insight here would allow one to predict how many qubits will be required to simulate a given problem to chemical precision.

It is not fully understood how CS-VQE relates to active space techniques more generally, but this would be an interesting pursuit for future work. For example, the downfolding technique of subsystem embedding subalgebra coupled cluster (SES-CC)65 presents a compelling approach that iteratively decouples excitations σ = σint + σext into an “internal” part that belongs to a chosen excitation subalgebra and its “external” complement that may additionally be combined with the double unitary coupled cluster (DUCC) ansatz.66 This yields an effective Hamiltonian Hexteff(DUCC) = (P + Qint) e–σextH eσext(P + Qint) where P projects onto the reference state and Qint onto the subspace of excitations generated by σint. This has a similar form to our stabilizer subspace projection (eq 13); indeed, it might be possible to reproduce SES-CC under a qubit mapping within the contextual subspace framework by identifying an appropriate noncontextual sub-Hamiltonian and stabilizer subspace.

A benchmark of this and other dimensionality reduction methodologies such as projection-based embedding (PBE)67 would be valuable. Furthermore, CS-VQE can be layered on top of these techniques to yield hybrid methods that might outperform any of them on their own; this is a consideration that we plan to take forward into further work, with the goal of deployment on larger molecular systems and basis sets.

4.4. The Noncontextual Projection Ansatz

CS-VQE has thus far not been applied to systems exceeding 18 qubits, and the resulting reduced Hamiltonians (eq b23) have been solved by direct diagonalization;45 clearly, this will not scale to larger systems, with the required classical memory increasing exponentially. Instead, they must be simulated by performing VQE routines, but defining an ansatz for the contextual subspace provided an obstacle to achieving this in practice.

However, having now placed the problem within the stabilizer formalism described in Section 3, we have already introduced (in Sections 4.1–4.3) the tools necessary to restrict an ansatz of the form in eq 5–defined over the full system–to the contextual subspace (eq 23). The approach adopted here is equivalent to that which we defined for qubit tapering in eq 15. To restrict a parametrized ansatz operator

| 26 |

in line with the stabilizer constraints  , we may simply call upon the stabilizer

subspace projection map

, we may simply call upon the stabilizer

subspace projection map  once more, which yields a restricted ansatz

state

once more, which yields a restricted ansatz

state

| 27 |

where

| 28 |

Any rotated ansatz term  that is not identity or a Pauli σp on some subset of the qubit positions indexed

by

that is not identity or a Pauli σp on some subset of the qubit positions indexed

by  will vanish.

will vanish.

The restricted reference

state  is obtained from an effective partial projective

measurement of

is obtained from an effective partial projective

measurement of  (see the discussion on POVMs in Section 3) with outcomes

defined by ν′, which yields a product state

(see the discussion on POVMs in Section 3) with outcomes

defined by ν′, which yields a product state

| 29 |

where we have explicitly demarcated the separability

across  and

and  . The postmeasurement state

. The postmeasurement state  on the noncontextual subspace represents

a single basis vector and can therefore be disregarded, leaving just

the state of the contextual subspace; this we take as reference for

our restricted ansatz. If the unitary partitioning rotations are not to be applied, then the

on the noncontextual subspace represents

a single basis vector and can therefore be disregarded, leaving just

the state of the contextual subspace; this we take as reference for

our restricted ansatz. If the unitary partitioning rotations are not to be applied, then the  rotation is trivial over

rotation is trivial over  and we incur no expense in coherent resource.

However, if one does enforce the operator C(r) over the contextual subspace, there might be some nontrivial

component of the rotation that must be applied in-circuit to ensure

that the ansatz lies within the correct subspace; referring to Section 4.2, for the SeqRot

approach this will consist of at most

and we incur no expense in coherent resource.

However, if one does enforce the operator C(r) over the contextual subspace, there might be some nontrivial

component of the rotation that must be applied in-circuit to ensure

that the ansatz lies within the correct subspace; referring to Section 4.2, for the SeqRot

approach this will consist of at most  CNOT operations in-circuit, whereas LCU

is probabilistic due to the nature of block-encoding.35 Given a hardware-efficient ansatz, one may neglect this

since the optimizer should compensate the parameters accordingly.

CNOT operations in-circuit, whereas LCU

is probabilistic due to the nature of block-encoding.35 Given a hardware-efficient ansatz, one may neglect this

since the optimizer should compensate the parameters accordingly.

We may now define the contextual subspace energy expectation function

| 30 |

with  as in eq 23, at which

point we have reduced the problem to standard VQE, performed over

a subspace of the full problem.

as in eq 23, at which

point we have reduced the problem to standard VQE, performed over

a subspace of the full problem.

5. Simulation Results

The molecular systems that were simulated to benchmark the noncontextual projection ansatz for CS-VQE are given in Table 1. The molecule geometries were obtained from the Computational Chemistry Comparison and Benchmark Database (CCCBDB)68 and their Hamiltonians were constructed using IBM’s Qiskit Nature69 with PySCF as the underlying quantum chemistry package.70

Before we evaluate the efficacy of our noncontextual projection

ansatz, there are a few features of eq 27 that

should be highlighted. First of all, from the discussion following

eq 29, we potentially apply some component of

the operation  in-circuit, introducing further gates that

will contribute additional noise. However, when the reference state

is taken to be that of Hartree–Fock, we observed Uψref to coincide with the noncontextual ground state. This

is an artifact of the noncontextual set construction heuristic prioritizing

diagonal entries, used within both this work and that of Kirby et

al.45 This need not always be the case,

but for the molecular systems investigated, this allows us to avoid

performing

in-circuit, introducing further gates that

will contribute additional noise. However, when the reference state

is taken to be that of Hartree–Fock, we observed Uψref to coincide with the noncontextual ground state. This

is an artifact of the noncontextual set construction heuristic prioritizing

diagonal entries, used within both this work and that of Kirby et

al.45 This need not always be the case,

but for the molecular systems investigated, this allows us to avoid

performing  in-circuit and instead take the noncontextual

ground state as our reference. Since we choose to rotate the noncontextual

symmetry generators onto Pauli σ3 operators here,

this may be prepared by applying a Pauli σ1 in each

of the qubit positions

in-circuit and instead take the noncontextual

ground state as our reference. Since we choose to rotate the noncontextual

symmetry generators onto Pauli σ3 operators here,

this may be prepared by applying a Pauli σ1 in each

of the qubit positions  such that νi = −1 so that the corresponding reference state is stabilized

by the relevant operators νiσ3(i). This is visible in Figure 2, in which the VQE routine is initiated with the optimization

parameters zeroed, i.e., θ = 0, and

since eiÃ(0) = 1, optimization begins at the noncontextual ground state energy.

such that νi = −1 so that the corresponding reference state is stabilized

by the relevant operators νiσ3(i). This is visible in Figure 2, in which the VQE routine is initiated with the optimization

parameters zeroed, i.e., θ = 0, and

since eiÃ(0) = 1, optimization begins at the noncontextual ground state energy.

Figure 2.

Validation of the noncontextual projection approach to ansatz construction for CS-VQE (eq 27), used here in conjunction with ADAPT-VQE.16−19 We plot (on a log10 scale) the absolute error of wave function simulations conducted for the suite of trial molecules outlined in Table 1, each shown to achieve chemical precision; the horizontal axis indicates the algorithm step counter with each shaded region a separate ADAPT-VQE cycle. Adaptive moment estimation (Adam)73 is the classical optimizer taken in the VQE routine performed over the contextual subspace for each ADAPT-VQE cycle, and the settings used are as follows: tolerance = 10–4, learning rate = 10–2, β1 = 0.4, β2 = 0.999, ϵ = 10–8. The parameter gradients ∂Ẽ(θ)/∂θi, required for both operator pool term selection and VQE, were computed using the parameter shift rule.74

Second, application of the unitary partitioning rotations UC to the ansatz operator A(θ) may introduce additional terms by

a worst-case scaling factor of  where M is the number

of equivalence classes in eq 17, although the

true scaling is unlikely to be this severe as discussed in Section 4.2. We obtained

M = 2 for all of the molecules tested, in which case SeqRot is identical

to the asymptotically favorable LCU method. In fact, for small M ≪ N, SeqRot may generate fewer

terms than LCU (Ralli et al. presented a toy problem with M = 3 in which this was the case36) and therefore our choice of SeqRot here is valid given that the

noncontextual set

where M is the number

of equivalence classes in eq 17, although the

true scaling is unlikely to be this severe as discussed in Section 4.2. We obtained

M = 2 for all of the molecules tested, in which case SeqRot is identical

to the asymptotically favorable LCU method. In fact, for small M ≪ N, SeqRot may generate fewer

terms than LCU (Ralli et al. presented a toy problem with M = 3 in which this was the case36) and therefore our choice of SeqRot here is valid given that the

noncontextual set  construction heuristic prioritizes the

universally commuting terms

construction heuristic prioritizes the

universally commuting terms  in eq 17. Different

heuristics may lead to larger values for M, in which

case, we recommend an adoption of LCU for implementations of CS-VQE.

in eq 17. Different

heuristics may lead to larger values for M, in which

case, we recommend an adoption of LCU for implementations of CS-VQE.

Despite this, upon the subsequent projection of A(θ), it is possible that a significant number

of terms will vanish. This is highly dependent on the quality of the

initial ansatz and how heavily it is supported on the stabilized qubit

positions  . Figure 1 presents circuit depths of the noncontextual projection

ansatz as a proportion of the base ansatz from which it is derived,

in this case the unitary coupled-cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD)

operator. A net reduction in circuit depth is observed, which is quite

dramatic up to the point of reaching chemical precision in the CS-VQE

routine; in Table 2, we give the specific number of ansatz terms before and after application

of the noncontextual projection to UCCSD and UCCSDT for the fewest

number of qubits permitting chemical precision.

. Figure 1 presents circuit depths of the noncontextual projection

ansatz as a proportion of the base ansatz from which it is derived,

in this case the unitary coupled-cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD)

operator. A net reduction in circuit depth is observed, which is quite

dramatic up to the point of reaching chemical precision in the CS-VQE

routine; in Table 2, we give the specific number of ansatz terms before and after application

of the noncontextual projection to UCCSD and UCCSDT for the fewest

number of qubits permitting chemical precision.

Figure 1.

Ideal CS-VQE errors (left-hand axis) and corresponding noncontextual projection ansatz circuit depths as a proportion of the full UCCSD operator from which it is derived (right-hand axis) against the number of qubits simulated.

Table 2. Number of Pauli Terms  for a Selection of (Tapered) Ansätzea.

for a Selection of (Tapered) Ansätzea.

| number

of terms in ansatz operator |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| molecule |  |

UCCSDT (full/proj)b | UCCSD (full/proj)b | ADAPT-VQEc |

| Be | 3 | (48/6) | (48/6) | 5 |

| B | 3 | (48/12) | (32/4) | 3 |

| LiH | 4 | (704/53) | (192/53) | 5 |

| BeH+ | 6 | (646/191) | (166/79) | 11 |

| HF | 4 | (92/57) | (92/57) | 4 |

| BeH2 | 7 | (1312/352) | (224/96) | 10 |

| H2O | 7 | (1892/942) | (324/238) | 21 |

| F2 | 10 | (176/114) | (176/114) | 12 |

| HCl | 4 | (348/40) | (348/40) | 4 |

The number of qubits in the contextual subspace over which the ansatz is projected; each tuple (full/proj) gives the number of terms pre- and postprojection.

The number of ADAPT-VQE cycles required to achieve chemical precision, with the operator pool consisting of the projected UCCSD terms.

In order to identify a compact ansatz that closely captures the underlying chemistry with minimal redundancy, we employ the ADAPT-VQE methodology.16−19 The algorithm centers around an operator pool from which terms are selected in line with a gradient-based argument and appended to a dynamically expanding ansatz whose parameters are optimized at each cycle via VQE. The particular approach we implement here is that of qubit-ADAPT-VQE,17 following on from iterative qubit coupled cluster,71 which searches at the level of Jordan–Wigner encoded Pauli operators; the seminal ADAPT-VQE paper16 instead defines its operator pool over Fermionic excitations.

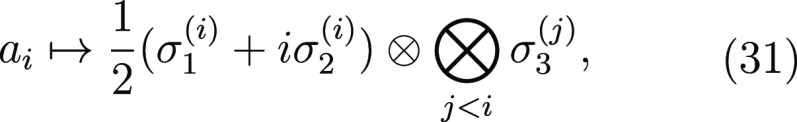

The Jordan–Wigner transformation72 maps a single Fermionic annihilation operator onto two Pauli operators

|

31 |

with the creation operator given by its Hermitian

conjugate ai†. Therefore, an excitation

on  spin orbitals of the form

spin orbitals of the form

| 32 |

is represented by 22s Pauli operators under this encoding. In the unitary coupled cluster theory, we are interested rather in the operator a–a† to ensure unitarity upon exponentiation; this may be expressed by 22s–1 Pauli terms.

As such, after a mapping onto qubits via the Jordan–Wigner transformation, single, double, and triple excitations account for 2, 8, and 32 Pauli operator terms, respectively; while these are required to enforce various electronic symmetries in the ansatz state, not all are necessary to reach chemical precision. This idea lies behind qubit-ADAPT-VQE, which will select only the necessary Pauli terms and therefore yields considerably reduced circuit depths.17

To leverage ADAPT-VQE in the context of

CS-VQE, we define an operator

pool  and apply to it the stabilizer subspace

projection (eq 13) to define a reduced pool

and apply to it the stabilizer subspace

projection (eq 13) to define a reduced pool  for the corresponding contextual subspace.

Projecting the full pool in this way will ensure that any symmetries S present will be preserved, since

for the corresponding contextual subspace.

Projecting the full pool in this way will ensure that any symmetries S present will be preserved, since  , allowing us to incorporate some chemical

intuition into the contextual subspace despite an abstraction from

the original problem; one could define a reduced pool directly, but

care should be taken to avoid the inclusion of symmetry-breaking terms

that may needlessly increase the complexity of the ADAPT-VQE procedure.

The algorithm is then executed as normal, only terminating once the

ADAPT-VQE energy is chemically precise with respect to the FCI energy;

for scalability, one should terminate computation when the largest

gradient in magnitude falls below some predefined threshold, since

the true ground state energy will not in general be known. In the Supporting Information, we provide a detailed

description of the specific ADAPT-VQE implementation used within this

work.

, allowing us to incorporate some chemical

intuition into the contextual subspace despite an abstraction from

the original problem; one could define a reduced pool directly, but

care should be taken to avoid the inclusion of symmetry-breaking terms

that may needlessly increase the complexity of the ADAPT-VQE procedure.

The algorithm is then executed as normal, only terminating once the

ADAPT-VQE energy is chemically precise with respect to the FCI energy;

for scalability, one should terminate computation when the largest

gradient in magnitude falls below some predefined threshold, since

the true ground state energy will not in general be known. In the Supporting Information, we provide a detailed

description of the specific ADAPT-VQE implementation used within this

work.

For the following, we take our pool  to be the terms of the UCCSD operator for

each of the molecules in Table 1 before tapering and projecting into the relevant contextual

subspace. In Figure 2, we present the ADAPT-VQE convergence data

with expectation values obtained via exact wave function (statevector)

calculations (i.e., no statistical/hardware noise); chemical precision

is achieved in each instance. We used the adaptive moment estimation

(Adam)73 classical optimizer and computed

parameter gradients as per the parameter shift rule.74 Adam has been adopted for previous research in VQE for

its resilience to noise, although it exhibits relatively slow convergence

compared with other optimizers75,76 such as Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno

(BFGS)77 and quantum natural gradient (NatGrad);78 the latter might be preferable for future work.

to be the terms of the UCCSD operator for

each of the molecules in Table 1 before tapering and projecting into the relevant contextual

subspace. In Figure 2, we present the ADAPT-VQE convergence data

with expectation values obtained via exact wave function (statevector)

calculations (i.e., no statistical/hardware noise); chemical precision

is achieved in each instance. We used the adaptive moment estimation

(Adam)73 classical optimizer and computed

parameter gradients as per the parameter shift rule.74 Adam has been adopted for previous research in VQE for

its resilience to noise, although it exhibits relatively slow convergence

compared with other optimizers75,76 such as Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno

(BFGS)77 and quantum natural gradient (NatGrad);78 the latter might be preferable for future work.

The number of ADAPT-VQE cycles (and therefore the

number of terms

in the resulting ansatz operator) are presented in Table 2, alongside the size of the

projected UCCSD operator pool used; one observes a significant reduction

in the number of terms. The optimized ADAPT-VQE ansatz operators are

reported in ancillary data files, along with a description of the

smallest CS-VQE problem permitting chemical precision. This includes

the optimal noncontextual generator subset  , the resulting noncontextual projection

ansatz (eq 27), the restricted reference state

, the resulting noncontextual projection

ansatz (eq 27), the restricted reference state  (eq 29), the target

error

(eq 29), the target

error  (eq 25), and that

which was actually achieved in our VQE simulations (Figure 2). We also include the corresponding

contextual subspace Hamiltonians for reproducibility.

(eq 25), and that

which was actually achieved in our VQE simulations (Figure 2). We also include the corresponding

contextual subspace Hamiltonians for reproducibility.

Extracting

the optimal parameter configuration θmin from the wave function simulations in Figure 2, we subsequently assess the

effect of sampling noise on the simulation error with our ansatz circuit

preparing the optimal quantum state  . Note that, for each of the molecular systems

in Table 1, θmin is given explicitly in the ancillary data files.

. Note that, for each of the molecular systems

in Table 1, θmin is given explicitly in the ancillary data files.

To achieve an absolute error of Δ > 0, one should expect

to perform  shots (for each term of the Hamiltonian).4 Conversely, suppose we are allocated a quantity

shots (for each term of the Hamiltonian).4 Conversely, suppose we are allocated a quantity  of shots; the obtained error should be

of the order

of shots; the obtained error should be

of the order  . In order to increase estimate accuracy,

we collected the Pauli terms into qubit-wise commuting (QWC) groups25 using the graph-coloring functionality of NetworkX;79 such groups may be measured simultaneously.

. In order to increase estimate accuracy,

we collected the Pauli terms into qubit-wise commuting (QWC) groups25 using the graph-coloring functionality of NetworkX;79 such groups may be measured simultaneously.

In Figure 3, the number of shots S = 2n for n = 0, ..., 20 carried out per QWC group is varied, and we observe the root mean-square error (RMSE) over 20 realizations of the ground state energy estimate, plotted on a log–log scale. For clarity, note the only source of noise here is that which arises from statistical variation of the quantum circuit sampling; we have not introduced hardware noise in the form of imperfect quantum gates or decoherence.

Figure 3.

Each of the plots in

panels a–i correspond with Figure 2a–i and illustrate

the statistical effect of sampling noise at the optimal parametrization θmin determined from the ADAPT-VQE statevector

simulations in Figure 2. We plot the root-mean-square error (RMSE) for 20 “realizations”

of the ground state energy estimate with S ≤

220 shots executed via IBM’s QASM simulator; determining

the line of best fit m·log10(S) + c with respect to the log–log

data indicates a decay in error of  .

.

Two error regimes are observed, one of which is

quite trivial:

at high shot counts, we see a plateau resulting from the optimal error  being recovered. To assess the convergence

properties outside of this limiting region, we plot a line of best

fit m·log10(S) + c among the data not exhibiting such behavior; since the

data is represented on a log–log scale, this corresponds with

a decay in error of

being recovered. To assess the convergence

properties outside of this limiting region, we plot a line of best

fit m·log10(S) + c among the data not exhibiting such behavior; since the

data is represented on a log–log scale, this corresponds with

a decay in error of  . In each plot of Figure 3, we obtain m ≈ −0.5,

meaning the RMSE follows the predicted decay of

. In each plot of Figure 3, we obtain m ≈ −0.5,

meaning the RMSE follows the predicted decay of  .

.

In every simulation bar F2, chemical precision was achieved within S = 220 ≈ 106 shots per QWC group. However, our shot budget could be reduced by implementing more advanced allocation strategies, for example, according to the magnitude of Hamiltonian term coefficients80 or a classical shadow tomography approach.30,31

6. Conclusions

We have placed CS-VQE on the theoretical footing of stabilizer subspace projections, which allows one to compare it against other qubit reduction techniques such as qubit tapering.47,48 Tapering defines a projection dependent on a symmetry of the full Hamiltonian and preserves the ground state energy exactly, whereas CS-VQE is approximate and projects onto a contextual subspace consistent with the symmetry of the noncontextual sub-Hamiltonian, augmented by an anticommuting contribution. In combination, the two techniques can effect a significant reduction in quantum resource requirements, as illustrated by Kirby et al.45 and in Figure 1.

Previously, the only obstacle to building a CS-VQE framework that would be faithful to deployment on quantum devices was that of the ansatz, which has been addressed within this work. Furthermore, we demonstrated how CS-VQE may be combined with the ADAPT-VQE16−19 ansatz construction framework by applying our noncontextual projection to the operator pool; validation was presented in Figure 2 in which we achieved chemical precision for the suite of small molecules outlined in Table 1. This combination provides considerable flexibility in both qubit count and circuit depth, allowing one to identify a reduced problem that may be simulated on the available quantum resource.

A number of research questions concerning

the scalability of CS-VQE

remain; we recapitulate these here. First, the success of CS-VQE is

sensitive to the generator subset  one chooses to constrain in the stabilizer

subspace projection. To date, the most effective method for choosing

this subset has been a greedy-search heuristic necessitating

one chooses to constrain in the stabilizer

subspace projection. To date, the most effective method for choosing

this subset has been a greedy-search heuristic necessitating  VQE simulations where d ≤ N is the search depth; this is expensive

for NISQ hardware, and there is room for more targeted heuristics.

For example, we may draw on chemical intuition to inform the selection

of a contextual subspace that captures information about the underlying

electronic structure problem. The second obstacle lies in the approach

taken to construct the noncontextual sub-Hamiltonian. There is currently

no intuition as to what constitutes an effective choice here, although

it should be noted that the “optimal” noncontextual

subset will not necessarily be that which minimizes the noncontextual

ground state energy; some consideration of the resulting contextual

subspaces must come into the construction of the noncontextual problem.

We leave these issues for future work.

VQE simulations where d ≤ N is the search depth; this is expensive

for NISQ hardware, and there is room for more targeted heuristics.

For example, we may draw on chemical intuition to inform the selection

of a contextual subspace that captures information about the underlying

electronic structure problem. The second obstacle lies in the approach

taken to construct the noncontextual sub-Hamiltonian. There is currently

no intuition as to what constitutes an effective choice here, although

it should be noted that the “optimal” noncontextual

subset will not necessarily be that which minimizes the noncontextual

ground state energy; some consideration of the resulting contextual

subspaces must come into the construction of the noncontextual problem.

We leave these issues for future work.

The natural next step is to execute this method on a NISQ computer, challenging the current best-in-class electronic structure simulations from Google, IonQ, and IBM.1−3 To achieve this goal, CS-VQE could be combined with techniques of measurement reduction20−35 and error mitigation.37−44

Finally, we have written an open-source Python package that facilitates the stabilizer subspace projection techniques of this work, with in-built tapering and CS-VQE functionality. We welcome the reader to make use of our code,49 which is freely available on GitHub.

Acknowledgments