Abstract

This study aimed to examine the relation between learning mode with sport participation and compare participation prevalence in different settings by learning mode among United States adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. A cross-sectional, national survey was conducted by a market research company (December 2021-January 2022) among parents whose child participated in sports pre-pandemic. Parents were asked about their child’s learning mode (in-person, online, hybrid); sports participation (yes/no) during the pandemic; and participation setting (school, community, club/elite). Weighted logistic regression models examined the relation between learning mode with sport participation. Weighted prevalence estimates of participation setting were compared by learning mode. Among youth included in the analysis (n = 500; Meanage = 14.0 years), 71.0% played sports during the pandemic. Learning mode was significantly associated with participating (versus not participating) among adolescents attending school online (aOR = 0.09; 95% CI: 0.04–0.18) and in a hybrid modality (aOR = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.15–0.58) versus those attending in-person. Those attending school online (versus in-person or hybrid) had significantly lower participation prevalence in community, school, and club/elite sports. Findings may reflect parents opting out of in-person activities or schools canceling organized sport opportunities. To inform engagement strategies, research is needed to understand reasons for declined participation and extent to which participation resumed.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, School, Sports, Adolescents, Disparities

1. Background

Youth opportunities for sports participation were notably disrupted by the novel SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), which was declared a global pandemic in March 2020. Leaders implemented measures such as stay-at-home orders, face masking, and social distancing to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. (Abouk and Heydari, 2021) Most youth sport-related activities in the United States were postponed and canceled in Spring 2020, with varying timing on reinstatement throughout the country. (Kroshus et al., 2020, Edwards et al., 2021, Dorsch and Blazo, 2021) Schools were also affected by the pandemic as many schools shifted to a remote or hybrid (i.e., combination of in-person and remote) learning format. (Bansak and Starr, 2021) Schools play an important role in youth sports promotion, (Kanters et al., 2013) as it is estimated that over half of students participate in school-based sports. (Merlo et al., 2020) Although the implications of pandemic-related shifts are still being examined, research suggests that there have been negative health impacts among youth, including marked reductions in physical activity and increased sedentary time. (Pooja et al., 2021, Rahman and Chandrasekaran, 2021, Viner et al., 2021) There are likely many contributing factors to these changes in health behavior, including less access and/or opportunities to play sports compared to before the pandemic. (Pietsch et al., 2022, Stockwell et al., 2021).

Participation in sports has been linked to numerous psychological, academic, and physical health benefits including decreased levels of depression and anxiety (Malina and Cumming, 2004, Taliaferro et al., 2008) and higher academic achievement. (Burns et al., 2020) Youth who participate in sport are also 64% more likely to meet physical activity guidelines. (Marques et al., 2016, Vella et al., 2013, Hebert et al., 2015, Mandic et al., 2012) Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, an estimated 61% and 55% of United States youth ages 10–13 and 14–17 years, respectively, participated in organized sports. (Hyde et al., 2020) In line with the Multi-level Model of Sport Participation, youth sports participation is influenced by factors on both the individual level (demand side), including household income, and on the infrastructure level (supply side), such as the availability of sports facilities. (Grima et al., 2017) Compared to recreational/community or elite/club sports, school-based sports are considered more accessible based on location, costs, and overall lower level of competition, (De Meester et al., 2014) as evidenced by the largest proportion of youth athletes participating in the school setting. (Sabo and Veliz, 2008) During the pandemic, however, sports organizations responded differently as local COVID-19-related restrictions were lifted, likely resulting in different levels of access between community, school, and club sports. Club/elite sports organizations resumed practice and competitions more quickly, potentially due to parental pressure and organizational or parental ability to pay for risk mitigation measures. (Edwards et al., 2021) In comparison, community centers and non-profit organizations (e.g., Boys and Girls Club, YMCA) were slower to re-open sports programming. (Dorsch and Blazo, 2021) Sports available through club or community organizations may have provided opportunities for adolescents to participate in sports during times of remote learning and school closures.

Although opportunities for organized sports participation have largely resumed in the United States, (Aspen Institute, 2021) it is unclear how the landscape of youth sports shifted during the pandemic, particularly by learning mode (i.e., the format in which instruction is delivered to students). Adolescent athletes who stopped participating during the pandemic may not have rejoined organized sports, likely exacerbating the negative impact of the pandemic on youth physical activity. (Stockwell et al., 2021) Regardless of participation status during the pandemic, adolescents experienced novel challenges to participating in youth sports during this time. (Flynn and Trentacosta, 2021) Examining the relation between learning mode with youth sports participation is important for informing strategies aimed to support equitable re-initiation and continuation of youth sports as the pandemic evolves. The primary aim of this study was to examine the relation between learning mode (in-person, online, hybrid) with sport participation (yes/no) during the COVID-19 pandemic among a nationally representative sample of United States adolescent athletes aged 11–17 years. A secondary aim was to compare the prevalence of sport participation in different settings (community, school, club) by learning mode.

2. Methods

2.1. Design/Participants

From December 2021-January 2022 a market research company (YouGov) conducted an online, opt-in cross-sectional survey among a United States nationally representative sample of parents of adolescents. Participants were primarily recruited through targeted Web advertising campaigns. To be eligible to participate, parents must have had a child aged 11–17 years who participated in organized sports anytime in the year prior to the pandemic (defined as March 2019-February 2020). If the parent had more than one eligible child, they were asked to report on the child who had the next upcoming birthday.

YouGov surveyed 2075 respondents, who were then matched down to a nationally representative sample of 500 according to United States census-based sampling frames by gender, age, race, and education, for a final analytic sample of 500. The frame was constructed by stratified sampling from the full 2019 American Community Survey 1-year sample, with selection within strata by weighted sampling with replacements (using the person weights on the public use file). Weighting was performed using propensity scores. The matched cases and the frame were combined, and a logistic regression, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, years of education, and region, was estimated to construct propensity of inclusion in the frame versus the matched cases. Additional details for YouGov’s sampling matching procedure can be found in Rivers. (Rivers, 2007).

Research procedures were approved by the Seattle Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board, which granted a waiver of written documentation of consent. An information sheet describing the research was provided to all participants, and they indicated their consent online before taking the survey.

2.2. Measures

All data were parent-reported. Survey items were adapted to be parent-reported, as needed, and pre-tested in cognitive interviews with parents of 11–17 year-old athletes. Inductively derived categorization of noted problems was used to determine whether items should be retained, deleted, or modified for the final survey. (Knafl et al., 2007) Demographic factors included child and parent age (in years), child and parent gender, child and parent race/ethnicity, the number of years that the child had participated in sports, household income, and parent education.

Learning mode. For learning mode, parents were asked how their child attended school during the pandemic (primarily in-person, equal combination of in-person and online, primary online), defined as March 2020-Present (December 2021-January 2022, time at which survey was taken).

Sports participation. The sport participation items were informed by sport survey items that had been validated or used in previous studies of youth sport participation. (Batista et al., 2019, Kellstedt et al., 2021, Logan et al., 2020, Mooses and Kull, 2020, Woods et al., 2020) Parents were asked whether their child participated in organized sports during the pandemic (defined above), yes/no. Organized sports were defined as leader-directed physical activity involving rules, practice, and competition. (Logan et al., 2020) If yes, parents were asked which sport(s) their child played, the number of years that their child had participated in sports, and the setting(s) in which they played each sport (school team, community/club recreation team, elite/select team, other).

2.3. Analyses

Descriptive statistics by parent and child, including means and frequency, were reported with sampling weights to be nationally representative in terms of parent demographic characteristics. For the primary aim, weighted logistic regression models before and after controlling for child gender, child grade level, child race, household income, and number of years playing sports were used to examine the relation between learning mode (in-person, online, hybrid modality) with sport participation (yes/no). For the secondary aim, weighted prevalence estimates of participation were compared by learning mode for each organizational setting of participation (community sports, school sports, club sports) using the Stata postestimation command lincom (linear combinations of estimators). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all analyses. All analyses were conducted using Stata 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

3. Results

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The average age of adolescents was 14.0 years (SD = 1.9). The majority of children in the sample were male (60.6%), White race (57.0%), and 24.5% were Hispanic ethnicity. Of the parents, 56.5% went to a two-year college or had at least a 4-year college education. Over 58% of households had an annual income of at least $60,000.

Table 1.

Parent participant characteristics; December 2021-January 2022 (N = 500).

| Total Sample (N = 500) | |

|---|---|

| Child Characteristics | |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 14.0 (1.9) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 298 (60.6) |

| Female | 200 (39.0) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (0.4) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black, African American, or African | 50 (10.3) |

| White | 298 (57.0) |

| Other racea | 20 (5.2) |

| Two or more races | 117 (24.5) |

| Unknown | 15 (3.1) |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish, n (%) | 119 (24.5) |

| Grade Level, n (%) | |

| 5th-8th Grade | 217 (45.2) |

| 9th-12th Grade | 283 (54.8) |

| Learning Mode, n (%) | |

| Primarily in-person | 168 (33.9) |

| Hybrid | 217 (42.0) |

| Primarily online | 115 (24.1) |

| Years participated in sports, mean (SD) | 5.7 (3.1) |

| Sport participation during pandemicb, n (%) | 362 (71.0) |

| Setting of sport participation during pandemic (n = 362), n (%) | |

| School Sports | 244 (66.8) |

| Community Sports | 172 (50.3) |

| Club/Elite Sports | 80 (23.4) |

| Parent Characteristics | |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 239 (48.3) |

| Female | 261 (51.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Did not graduate from high school | 17 (4.4) |

| High school graduate | 111 (23.4) |

| Some college | 78 (15.6) |

| 2-year college degree | 61 (11.7) |

| 4-year college degree | 139 (26.9) |

| Postgraduate degree | 94 (17.9) |

| Household Income, n (%) | |

| Up to $29,999 | 60 (13.7) |

| $30,000 - $59,999 | 127 (25.1) |

| $60,000 - $99,999 | 123 (24.2) |

| $100,000 - $199,999 | 134 (26.8) |

| $200,000 or more | 43 (7.9) |

| Unknown | 13 (2.4) |

SD = standard deviation.

Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaska Native, or Asian.

March 2020-January 2021.

Overall, school attendance was primarily in-person for 33.9% of adolescents, an equal combination of in-person and online for 42.0% of adolescents, and primarily online for 24.1 % of adolescents (Table 1). The average number of years that adolescents participated in organized sports was 5.7 years (SD = 3.1). About 71% of adolescents participated in organized sports during the pandemic. Of these adolescents (n = 362), over 66% participated in school sports, about 50 % participated in community sports, and about 23% participated in club sports (Table 1).

Types of sport participation during the pandemic by level of contact (contact or collision, no or limited contact) are presented in Table 2. These categories are consistent with the classification of sports according to contact by Rice (2008) Among youth who participated in sports during the pandemic, the most common sport was basketball (26.7%), followed by soccer (22.2%) and baseball (20.6%).

Table 2.

Type of adolescent sport participation during the COVID-19 pandemica (March 2020-January 2022) by sport groupb (n = 362).

| Contact or Collison | n (%) | No or Limited Contact | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basketball | 94 (26.7) | Baseball | 74 (20.6) |

| Cheerleading | 26 (7.8) | Bicycling | 11 (3.8) |

| Field hockey | 4 (1.1) | Dance | 24 (7.6) |

| Tackle football | 51 (15.3) | Flag football | 15 (3.8) |

| Golf | 9 (2.2) | Skateboarding | 4 (1.0) |

| Gymnastics | 14 (3.9) | Softball | 32 (8.5) |

| Ice hockey | 9 (3.4) | Swimming (team) | 22 (7.2) |

| Lacrosse | 9 (2.3) | Tennis | 24 (7.7) |

| Martial arts | 18 (7.2) | Track and field | 32 (8.2) |

| Soccer | 82 (22.2) | Volleyball | 34 (9.2) |

| Wrestling | 10 (2.8) |

March 2020-January 2021.

Consistent with the classification of sports according to contact by Rice (2008).

Results from the regression analyses examining the relation between school attendance mode and sport participation are presented in Table 3. In adjusted models, learning mode was statistically significantly associated with participating in sports during the pandemic. Specifically, adolescents attending school primarily online (aOR = 0.09; 95% CI: 0.04, 0.18) had lower odds for sport participation compared to those attending school primarily in-person. Similarly, adolescents attending in a hybrid school (aOR = 0.30; 95% CI: 0.15, 0.58) had lower odds for sport participation compared to those attending school primarily in-person.

Table 3.

Weighted logistic regression models for the association between learning mode and adolescent sports participation during the COVID-19 pandemic; March 2020-January 2022 (N = 500).

| Odds of Participating in Sports (versus not participating) During the COVID-19 Pandemic |

||

|---|---|---|

| Learning Mode | Model 1 OR (95 % CI) |

Model 2 aOR (95 % CI)a |

| In-person | REF | REF |

| Online | 0.11 (0.05, 0.24) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.19) |

| Hybrid | 0.35 (0.18, 0.71) | 0.30 (0.15, 0.58) |

Bold indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05.

OR = Odds ratio.

CI = Confidence intervals.

REF = Reference.

Adjusted for child gender, child grade level, child race, household income, number of years playing sports.

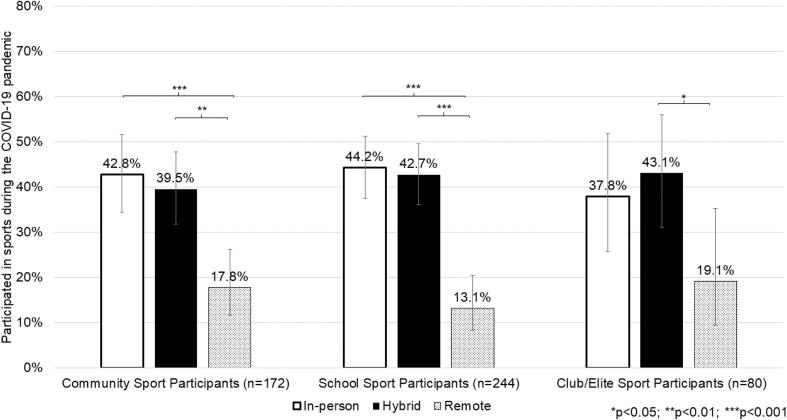

Weighted prevalence of participation by learning mode was compared among community, school, and club sport participants (Fig. 1). Among adolescents who participated in community-based sports (n = 172), prevalence of participation was significantly lower among adolescents attending school remotely (17.8, 95% CI: 11.6–26.2) compared to those attending school in a hybrid modality (39.5, 95% CI: 31.7–47.7; p = 0.001) and those attending school in-person (42.8, 95% CI: 34.3–51.6; p < 0.001). Among adolescents who participated in school-based sports (n = 244), prevalence of participation was significantly lower among adolescents attending school remotely (13.1, 95% CI: 8.2–20.3) compared to those attending school in a hybrid modality (42.7, 95% CI: 36.1–49.5; p < 0.001) and those attending school in-person (44.2, 95% CI: 37.4–51.2; p < 0.001). Among club/elite sport participants (n = 80), prevalence of participation was significantly lower among adolescents attending school remotely (19.1, 95% CI: 9.3–35.3) compared to those attending school in a hybrid modality (43.1, 95% CI: 31.0–56.0; p = 0.033).

Fig. 1.

Adolescent sports participation by learning mode among community, school, and club sport participants during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020-January 2022).

4. Discussion

This study examined the relation between learning mode with sports participation (in different settings) during the COVID-19 pandemic among United States adolescent athletes. Results showed over 70% of adolescent athletes continued to play sports during the pandemic, and adolescents attending school online or in a hybrid modality had lower odds of sports participation than those attending school in-person. Additionally, the prevalence of playing community and school sports was significantly higher among adolescents attending school in-person compared to those in a remote or hybrid modality.

These findings are consistent with existing literature showing an association between attending school in-person and participating in sports during the pandemic, (Edwards et al., 2021) which may reflect both parents’ risk tolerance (an influence on the demand side of the Multi-level Model of Sport Participation) and correlated school-community measures in response to infection rates (supply side). For example, parents who choose remote instruction are also likely to opt to their children out of other activities with person-to-person contact (e.g., organized sports) due to concerns about COVID-19 exposure, the most cited barrier to both in-person learning and to sports participation. (Haderlein et al., 2021, Aspen Institute, 2021) Additionally, mitigation measures (e.g., ‘stay-at-home’ orders, ban on social gatherings) are typically implemented at county-level (Fowler et al., 2021, Gadarian et al., 2021) and likely affect organizations within a given county similarly, including schools and sports programs. In the present study, sports participation prevalence was lower among remote learners, who have previously been shown to have lower physical activity levels of than those attending in-person. (Rahman and Chandrasekaran, 2021, Viner et al., 2021) These findings highlight the importance of developing strategies to encourage remote learners to stay active and engage in sport in ways that align with their family’s risk tolerance and community risk-mitigating measures.

For some adolescents, the decision to opt out of organized sports during the pandemic may be influenced by their family’s risk perceptions about in-person activities. Although parents’ concerns about COVID-19 exposure are common, (Aspen Institute, 2021) evidence suggests low transmission rates among youth athletes overall, (Jia et al., 2022) with incidence rates comparable to those reported for United States youth during a similar timeframe. (Biese et al., 2021) Further, implementing COVID-19 mitigation protocols (e.g., limiting contact, wearing masks, using outdoor facilities) in youth sports is an effective measure to limiting infection transmission. (Watson et al., 2021) Thus, youth sports do not necessarily need to be limited when COVID-19 rates increase, particularly when safety protocols are in place. Supporting youth physical activity and sports participation remains a public health priority, (Howie et al., 2020) and innovative approaches that incorporate known youth sports facilitators (e.g., positive peer relationships, enjoyment) (Howie et al., 2020) can keep youth active during times of remote learning and organized sport restrictions. Additionally, when it becomes necessary to close schools and restrict sports opportunities, organizational leadership should take steps to minimize risk and communicate with families to support informed decision-making.

Results showed that the prevalence of participation differed by school modality within each organizational setting. Among school and community sport participants, in-person or a hybrid school modality had a higher prevalence of sport participation compared to those attending remotely. Additionally, the highest participation prevalence overall was in the school setting, which is unsurprising given that school-based sports were most likely to resume at a normal level compared to community and club/elite sports. This suggests a positive relation between supply of school sports with youth sports participation in this setting, aligning with the Multi-level Model of Sport Participation. Resumption may be facilitated by governmental support and long-standing relationships with community members, as parents’ trust has been shown to impact how they view information from an organization and their willingness to resume activities. (Wang, 2020, Zdroik and Veliz, 2020, Aspen Institute, 2021) It is likely that schools offering in-person learning were also able to resume school sports, which may help explain the significant differences seen by learning modality. This was also seen for community sports, although overall prevalence was lower than school-based sports, in line with pre-pandemic studies. (Sabo and Veliz, 2008) Notably, the pandemic disrupted the supply of community sports programs, and in a national survey, over 44% of parents reported that their community-based sports program had either closed, merged, or returned with limited capacity. (Aspen Institute, 2021) If new programs are not developed to fill these voids, families may have limited accessibility to organized sport opportunities or face additional transportation and cost barriers when shifting to program in a different geographic area.

Overall, less than a quarter of adolescents that participated in sports during the pandemic participated in a club/elite sports setting. The United States youth sports industry generates about $19 billion annually (Rishe, 2020) and for most elite sports clubs, membership fees are the primary income source. (Green and Smith, 2016) This provided strong financial incentive for resumption of club-based sports during the pandemic. (Feiler and Breuer, 2021) Club sports, as private organizations, also have greater flexibility than city-run programs (e.g., imposing stricter requirements for enrollees). (Subramanyam and Kinderknecht, 2021). Although club sport parents are more willing to resume sports, (Edwards et al., 2021) participation costs have become more difficult as families deal with the financial strain of the pandemic. (Dorsch et al., 2021, Edwards et al., 2021) This has likely contributed to the shift in youth sports, as many athletes have returned to sports at a less competitive level than before the pandemic. (Aspen Institute, 2021) Presented results suggest that schools and community organizations continue to be the most prevalent youth sport settings, although more research is needed to examine how both the supply (e.g., availability of sports programs) and demand (e.g., barriers, interest in sports) have affected youth sports over the course of the pandemic, how this impacted participation setting, and how to promote sustained participation.

Presented findings show that over 70% of adolescent athletes continued to play sports during the pandemic. This is consistent with the literature, (Dorsch et al., 2021, Teare and Taks, 2021) including findings from a 2021 survey by the Aspen Institute showing that 27% of 11–14-year-olds and 24% of 15–18-year-olds who had played organized sports pre-pandemic had not resumed sports because they had lost interest. (Aspen Institute, 2021) Pre-pandemic, most youth athletes who dropped out of sports did so during adolescence, (Aspen Institute, 2021) with commonly cited reasons being both practical (time, cost, location) and personal (competition, competence, lack of enjoyment) in nature. (Crane and Temple, 2015, Somerset and Hoare, 2018) Pre-pandemic drop-out estimates range between 24% and 35% annually, (Balish et al., 2014, Møllerløkken et al., 2015) comparable to what was seen during the pandemic. (Aspen Institute, 2021) Although pre-pandemic research suggests that about half of youth who drop out rejoin in subsequent years, (Lindner, 2002) it is unclear what re-initiation will be among adolescent athletes who drop out during the pandemic given the additional barriers, and the number of programs that have closed or merged with other organizations. (Aspen Institute, 2021).

4.1. Limitations

The limitations of this study must be noted. First, all data were collected by parent report and therefore subject to recall and social desirability biases. Second, due to the cross-sectional nature of this study, it is not possible to infer causality. Finally, this survey was conducted December 2021-January 2022, and pandemic-related circumstances around the status of schools and sports, COVID-19 rates, and state restrictions may have changed in the following months. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine youth sports as the pandemic evolves to identify changes in sports participation, including athlete dropout and re-initiation as well as program availability.

5. Conclusions

Findings from this study suggest that 1) learning mode during COVID-19 is associated with sports participation and 2) there are significant differences in the participation by learning mode within different participation settings. Adolescents attending school online or in a hybrid setting had lower odds of participation than those attending in-person, which may reflect parental preferences for opting their children out of in-person activities or schools canceling sports opportunities. Athletes attending school remotely had significantly lower participation in school and community sports compared to those in an in-person or hybrid modality, possibly driven by this group’s lower participation in sports overall. Adolescents attending school remotely are a group with heightened pandemic impact, and decreased sports participation is one additional way that they were negatively impacted. Further research is needed to understand reasons for this decline, and whether participation resumed as the pandemic evolved, to inform strategies promoting engaged in organized sports.

Funding

This work was supported by the Seattle Children’s Research Institute Hearst Foundation Fellowship Award.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ashleigh M. Johnson: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Gregory Knell: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Timothy J. Walker: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Emily Kroshus: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. This work was supported by the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Hearst Foundation Fellowship Award. Dr. Walker was supported by NHLBI Grant K01HL151817.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Abouk R., Heydari B. The immediate effect of COVID-19 policies on social-distancing behavior in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2021;136(2):245–252. doi: 10.1177/0033354920976575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspen Institute. Project Play State of Play 2021. Pandemic Trends. Aspen Institute 2021.

- Balish S.M., McLaren C., Rainham D., Blanchard C. Correlates of youth sport attrition: A review and future directions. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2014;15(4):429–439. [Google Scholar]

- Bansak C., Starr M. COVID-19 shocks to education supply: How 200,000 US households dealt with the sudden shift to distance learning. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2021;19(1):63–90. doi: 10.1007/s11150-020-09540-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batista M.B., Romanzini C.L.P., Barbosa C.C.L., Blasquez Shigaki G., Romanzini M., Ronque E.R.V. Participation in sports in childhood and adolescence and physical activity in adulthood: A systematic review. J. Sports Sci. 2019;37(19):2253–2262. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2019.1627696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biese K.M., McGuine T.A., Haraldsdottir K., Goodavish L., Watson A.M. COVID-19 Risk in Youth Club Sports: A Nationwide Sample Representing More Than 200,000 Athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2021;56(12):1265–1270. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-0187.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns R.D., Brusseau T.A., Pfledderer C.D., Fu Y. Sports participation correlates with academic achievement: results from a large adolescent sample within the 2017 US National Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2020;127(2):448–467. doi: 10.1177/0031512519900055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J., Temple V. A systematic review of dropout from organized sport among children and youth. Eur. Phy. Educ. Rev. 2015;21(1):114–131. [Google Scholar]

- De Meester A., Aelterman N., Cardon G., De Bourdeaudhuij I., Haerens L. Extracurricular school-based sports as a motivating vehicle for sports participation in youth: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2014;11(1):1–15. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-11-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch T.E., Blazo J.A., Arthur-Banning S.G., et al. National Trends in Youth Sport during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Understanding American Parents' Perceptions and Perspectives. J. Sport Behav. 2021;44(3):303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Dorsch T.E., Blazo J.A. Project Play Aspen Institute; 2021. COVID-19 Parenting Survey IV. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards M.B., Bocarro J.N., Bunds K.S., et al. Parental perceptions of the impact of COVID-19 and returning to play based on level of sport. Sport Soc. 2021;1–18 [Google Scholar]

- Feiler S., Breuer C. Perceived Threats through COVID-19 and the Role of Organizational Capacity: Findings from Non-Profit Sports Clubs. Sustainability. 2021;13(12):6937. [Google Scholar]

- Flynn J., Trentacosta N. The COVID-19 Pandemic Upended Youth Sports. Pediatr. Ann. 2021;50(11):e450–e453. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20211016-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler J.H., Hill S.J., Levin R., Obradovich N. Stay-at-home orders associate with subsequent decreases in COVID-19 cases and fatalities in the United States. PLoS One. 2021;16(6):e0248849. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0248849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadarian S.K., Goodman S.W., Pepinsky T.B. Partisanship, health behavior, and policy attitudes in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0249596. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green K., Smith A. Routledge; 2016. Routledge handbook of youth sport. [Google Scholar]

- Grima S., Grima A., Thalassinos E., Seychell S., Spiteri J.V. Theoretical Models for Sport Participation: Literature Review. Int. J. Econ. Bus. Admin. (IJEBA). 2017;3:94–116. [Google Scholar]

- Haderlein S.K., Saavedra A.R., Polikoff M.S., Silver D., Rapaport A., Garland M. Disparities in educational access in the time of COVID: Evidence from a nationally representative panel of American families. Aera Open. 2021;7 [Google Scholar]

- Hebert J.J., Møller N.C., Andersen L.B., Wedderkopp N. Organized sport participation is associated with higher levels of overall health-related physical activity in children (CHAMPS study-DK) PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0134621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howie E.K., Guagliano J.M., Milton K., et al. Ten Research Priorities Related to Youth Sport, Physical Activity, and Health. J. Phys. Act. Health. 2020;17(9):920–929. [Google Scholar]

- Howie E.K., Daniels B.T., Guagliano J.M. Promoting physical activity through youth sports programs: It’s social. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2020;14(1):78–88. doi: 10.1177/1559827618754842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde E.T., Omura J.D., Fulton J.E., Lee S.M., Piercy K.L., Carlson S.A. Disparities in youth sports participation in the US, 2017–2018. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2020;59(5):e207–e210. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L., Huffman W.H., Cusano A., et al. The Risk of COVID-19 Transmission Upon Return to Sport: A Systematic Review. Phys. Sportsmedicine. 2022 doi: 10.1080/00913847.2022.2035197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanters M.A., Bocarro J.N., Edwards M.B., Casper J.M., Floyd M.F. School sport participation under two school sport policies: comparisons by race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013;45(suppl_1):S113–S121. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9413-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellstedt D.K., Schenkelberg M.A., Von Seggern M.J., et al. Youth sport participation and physical activity in rural communities. Arch. Public Health. 2021;79(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knafl K., Deatrick J., Gallo A., et al. The analysis and interpretation of cognitive interviews for instrument development. Res. Nurs. Health. 2007;30(2):224–234. doi: 10.1002/nur.20195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroshus E., Hawrilenko M., Tandon P.S., Christakis D.A. Plans of US parents regarding school attendance for their children in the fall of 2020: a national survey. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(11):1093–1101. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner J. Withdrawal from competitive youth sport: A retrospective ten-year study. J. Sport Behav. 2002;25(2):7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Logan K., Lloyd R.S., Schafer-Kalkhoff T., et al. Youth sports participation and health status in early adulthood: A 12-year follow-up. Prev. Med. Rep. 2020;101107 doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malina, R., Cumming, S., 2004. Current status and issues in youth sports. Youth sports: Perspectives for a new century: Coaches Choice. 7-25.

- Mandic S., Bengoechea E.G., Stevens E., de la Barra S.L., Skidmore P. Getting kids active by participating in sport and doing it more often: focusing on what matters. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2012;9(1):86. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques A., Ekelund U., Sardinha L.B. Associations between organized sports participation and objectively measured physical activity, sedentary time and weight status in youth. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2016;19(2):154–157. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merlo C.L., Jones S.E., Michael S.L., et al. Dietary and physical activity behaviors among high school students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020;69(1):64–76. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møllerløkken N.E., Lorås H., Pedersen A.V. A systematic review and meta-analysis of dropout rates in youth soccer. Percept. Mot. Skills. 2015;121(3):913–922. doi: 10.2466/10.PMS.121c23x0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooses K., Kull M. The participation in organised sport doubles the odds of meeting physical activity recommendations in 7–12-year-old children. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2020;20(4):563–569. doi: 10.1080/17461391.2019.1645887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch S., Linder S., Jansen P. Well-being and its relationship with sports and physical activity of students during the coronavirus pandemic. German J. Exercise Sport Res. 2022;52(1):50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Pooja S., Tandon C.Z., Johnson A.M., Gonzalez E.S., Kroshus E. Association of Children's Physical Activity and Screen Time with Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.27892. aop. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman A.M., Chandrasekaran B. Estimating the Impact of the Pandemic on Children's Physical Health: A Scoping Review. J. Sch. Health. 2021;91(11):936–947. doi: 10.1111/josh.13079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice S.G. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Medical Conditions Affecting Sports Participation. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):841–848. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishe P. Coronavirus cancellations are impacting youth sports and fans’ ability to release emotions at games. Forbes. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Rivers D. Stanford University and Polimetrix, Inc.; 2007. Sampling for web surveys. [Google Scholar]

- Sabo D., Veliz P. Women's Sports Foundation; East Meadow, NY: 2008. Go Out and Play: Youth Sports in America. [Google Scholar]

- Somerset S., Hoare D.J. Barriers to voluntary participation in sport for children: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12887-018-1014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell S., Trott M., Tully M., et al. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviours from before to during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021;7(1):e000960. doi: 10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanyam V., Kinderknecht J. Lessons Learned from COVID-19: The Youth Sports World Going Forward. Pediatr. Ann. 2021;50(11):e470–e473. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20211018-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliaferro L.A., Rienzo B.A., Miller M.D., Pigg R.M., Jr, Dodd V.J. High school youth and suicide risk: exploring protection afforded through physical activity and sport participation. J. Sch. Health. 2008;78(10):545–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teare G., Taks M. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth sport and physical activity participation trends. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):1744. [Google Scholar]

- Vella S.A., Cliff D.P., Okely A.D., Scully M.L., Morley B.C. Associations between sports participation, adiposity and obesity-related health behaviors in Australian adolescents. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013;10(1):113. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner R.M., Russell S., Saulle R., et al. Impacts of school closures on physical and mental health of children and young people: a systematic review. MedRxiv. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.-Y.-C. Information behavior of parents during COVID-19 in relation to their young school-age children’s education. Ser. Libr. 2020;79(1–2):62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Watson A.M., Haraldsdottir K., Biese K., Goodavish L., Stevens B., McGuine T. The association of COVID-19 incidence with sport and face mask use in United States high school athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2021 doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-281-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods S., Dunne S., McArdle S., Gallagher P. Committed to Burnout: An investigation into the relationship between sport commitment and athlete burnout in Gaelic games players. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Zdroik J., Veliz P. Participative Decision-Making: A Case of High School Athletics. J. Sport Behav. 2020;43(3):386–402. [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- Hawrilenko M., Kroshus E., Tandon P., Christakis D. The association between school closures and child mental health during COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4(9):e2124092–e. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.24092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan K., Cuff S. Organized sports for children, preadolescents, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2019;143(6):e20190997. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases DoVD. Guidance for COVID-19 Prevention in K-12 Schools. 2022; https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/k-12-guidance.html, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.