Abstract

Background and Aims

Arthrofibrosis is a severe scarring condition characterized by joint stiffness and pain. Fundamental to developing arthrofibrotic scars is the accelerated production of procollagen I, a precursor of collagen I molecules that form fibrotic deposits in affected joints. The procollagen I production mechanism comprises numerous elements, including enzymes, protein chaperones, and growth factors. This study aimed to elucidate the differences in the production of vital elements of this mechanism in surgical patients who developed significant posttraumatic arthrofibrosis and those who did not.

Methods

We studied a group of patients who underwent shoulder arthroscopic repair of the rotator cuff. Utilizing fibroblasts isolated from the patients' rotator intervals, we analyzed their responses to profibrotic stimulation with transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1). We compared TGFβ1‐dependent changes in the production of procollagen I. We studied auxiliary proteins, prolyl 4‐hydroxylase (P4H), and heat shock protein 47 (HSP47), that control procollagen stability and folding. A group of other proteins involved in excessive scar formation, including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), α smooth muscle actin (αSMA), and fibronectin, was also analyzed.

Results

We observed robust TGFβ1‐dependent increases in the production of CTGF, HSP47, αSMA, procollagen I, and fibronectin in fibroblasts from both groups of patients. In contrast, TGFβ1‐dependent P4H production increased only in the stiff‐shoulder‐derived fibroblasts.

Conclusion

Results suggest P4H may serve as an element of a mechanism that modulates the fibrotic response after rotator cuff injury.

Keywords: arthrofibrosis, collagen, profibrotic, scarring, stiff joints

1. INTRODUCTION

Joint arthrofibrosis due to excessive posttraumatic scarring involves the shoulder, elbow, hip, and knee. Arthrofibrotic scar tissue alters crucial functions of joints' elements, causing loss of their function, joint immobility, and pain. The clinical definition of joint stiffness and scarring depends on the specified joint. For instance, elbow contracture is defined as loss of extension greater than 30° and flexion less than 120°. 1 Similarly, shoulder scarring, or adhesive capsulitis, is a loss of range of motion greater than 25% in at least two planes, most notably external rotation and abduction. 2 Arthrofibrosis is a significant medical and socioeconomic problem associated with all diarthrodial joints. For instance, some estimates indicate that 3%–12% of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty develop arthrofibrosis that requires medical intervention. 3 Similarly, studies have reported arthrofibrosis in about 15% of the patients who have undergone shoulder surgery. 4 , 5

At present, there is no consensus on the treatment of arthrofibrosis. Conservative treatment with anti‐inflammatory drugs and aggressive physical therapy are initial therapeutic methods to alleviate the negative consequences of arthrofibrosis. Subsequent interventions include intra‐articular injection of steroids, hydrodilation, nerve blocks, and surgical interventions. None of these methods, however, is fully effective, so arthrofibrosis continues to affect patients' quality of life negatively.

A pathomechanism of arthrofibrosis is not fully understood. Scientists agree, however, that inflammation is a significant driver of this process. For instance, infiltrating inflammatory cells, including T cells, B cells, macrophages, and mast cells, into the shoulder's injured tissues defines Stage I of adhesive capsulitis. 6 , 7 , 8 During this stage, the inflammatory cells modulate the production of several profibrotic agents. Among them, transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1) is a critical regulator of the fibrotic process. 9 , 10 It upregulates the expression of crucial elements that form scar tissue, including fibril‐forming collagens, fibronectin, proteoglycans, and other structural macromolecules. A group of other factors produced by inflammatory cells in arthrofibrosis includes interleukin (IL)‐1α, IL‐1β, tumor necrosis factor‐α, and cyclooxygenase (COX)‐1 and COX‐2. 11 They stimulate synovial fibroblasts' proliferation, further elaborating fibrotic tissue growth. Fibroblasts' proliferation defines Stage II of adhesive capsulitis. Subsequently, the formation of dense collagenous tissue within the capsule initiates Stage III of the fibrotic process. The altered production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and MMP tissue inhibitors further accelerate the buildup of excessive scars. 6 , 11

Collagen I‐based fibrils are crucial elements of healthy joint tissues, including ligaments, tendons, and capsules, where they form well‐organized architectures needed for specific mechanical functions of the joint. With more than 90% of the scar's mass, poorly organized collagen fibrils are the main component of the arthrofibrotic tissue that stiffens the joints. 10

The formation of collagen fibrils is a complex process that involves intracellular and extracellular steps. A stable triple‐helical structure of individual collagen molecules is fundamental to assembling functional collagen fibrils. Furthermore, the intracellular formation of stable collagen triple helices depends on the auxiliary posttranslational machinery. Its vital elements include enzymes that modify nascent procollagen chains and protein chaperones that facilitate folding into triple helices. 12

Excessive deposition of collagen‐rich scar tissue is a hallmark of arthrofibrosis, and reducing its formation is the goal of all antifibrotic therapeutic approaches. 10 , 13 , 14 Consequently, to improve the outcomes of these approaches, it is critical to define crucial elements of collagen production machinery that modulate the development of arthrofibrosis.

In our exploratory study presented here, we aimed to elucidate molecular bases of significant differences in the extent of arthrofibrosis in the groups of patients who underwent rotator cuff repair. We hypothesized that diverse dynamics of collagen production by patient‐derived fibroblasts modulate these differences. Consequently, we utilized patient‐derived fibroblasts cultured in model profibrotic conditions to test this hypothesis. Our primary target was the quantification of a rationally selected panel of proteins that control collagen production and form arthrofibrotic tissue. The primary outcome measure of this study was the difference in the biosynthesis of critical collagen‐production markers analyzed in control and TGFβ1‐stimulated fibroblasts.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

We enrolled a prospective cohort of 32 patients, aged 35–73 years, undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair by a single fellowship‐trained shoulder and elbow surgeon at a single institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was approved by the Thomas University Institutional Review Board (control #15D.643).

The exclusion criterion was any previous ipsilateral shoulder surgery. A chart review was performed for demographics, comorbidities, duration of symptoms, and the number of torn tendons. Repairing the supraspinatus tendon was performed in 100% of cases; 58% included infraspinatus and 30% subscapularis. Posterosuperior tears were repaired with the double row in 85% of cases. No differentiation was made between traumatic and degenerative cuff tears.

Postoperatively, rehabilitation for all patients included sling immobilization for 6 weeks. Patients started home‐based, passive, range‐of‐motion exercises at 2 weeks; formal physical therapy was initiated at 6 weeks for motion, and strengthening started at 10 weeks. Table 1 summarizes patients' data.

Table 1.

A summary of patients' data.

| ID | Stiffness status | Age | Sex | ROM at 12 weeks | Thyroid disorder | Diabetes | Number of tendons torn | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Rotation | Passive forward elevation | ||||||||

| 1 | NS | 71 | F | 30 | 120 | − | − | 3 | 31.46 |

| 2 | NS | 71 | F | 50 | 150 | + | − | 2 | 23.63 |

| 3 | NS | 63 | M | 45 | 100 | − | + | 2 | 34.33 |

| 4 | NS | 45 | F | 50 | 150 | − | − | 1 | 24.03 |

| 5 | NS | 56 | M | 50 | 160 | − | + | 3 | 57.39 |

| 6 | NS | 56 | M | 50 | 150 | − | − | 3 | 29.75 |

| 7 | NS | 60 | M | 50 | 110 | − | − | 2 | 31.53 |

| 8 | NS | 68 | M | 50 | 150 | − | + | 2 | 36.18 |

| 9 | NS | 71 | M | 50 | 165 | + | + | 2 | 27.98 |

| 10 | NS | 48 | M | 50 | 130 | − | − | 2 | 50.13 |

| 11 | NS | 73 | M | 45 | 155 | − | − | 1 | 36.18 |

| 12 | NS | 64 | M | 45 | 135 | − | − | 2 | 27.12 |

| 13 | NS | 51 | M | 50 | 150 | − | − | 2 | 27.12 |

| 14 | NS | 56 | M | 70 | 170 | − | − | 2 | 32.55 |

| 15 | NS | 69 | F | 50 | 140 | − | + | 2 | 35.08 |

| 16 | NS | 72 | M | 45 | 150 | − | + | 2 | 36.49 |

| 17 | NS | 35 | M | 30 | 150 | − | − | 2 | 33.45 |

| 18 | NS | 61 | M | 50 | 140 | − | − | 3 | 31.56 |

| 19 | NS | 56 | M | 55 | 170 | − | − | 3 | 31.19 |

| 20 | NS | 72 | F | 40 | 150 | − | + | 1 | 35.08 |

| 21 | NS | 59 | M | 50 | 150 | − | + | 1 | 29.09 |

| 22 | NS | 51 | M | 50 | 140 | + | + | 1 | 37.59 |

| 23 | NS | 61 | F | 50 | 150 | − | − | 2 | 25.86 |

| 24 | NS | 58 | M | 45 | 150 | − | + | 2 | 33.05 |

| 25 | NS | 61 | M | 40 | 130 | − | − | 1 | 27.12 |

| 26 | ST | 58 | F | 60 | 110 | − | − | 2 | 22.86 |

| 27 | ST | 57 | M | 40 | 140 | − | − | 1 | 26.5 |

| 28 | ST | 65 | M | 45 | 110 | − | − | 1 | 25.66 |

| 29 | ST | 64 | F | 35 | 90 | − | + | 3 | 24.51 |

| 30 | ST | 58 | M | 50 | 120 | − | − | 2 | 31.56 |

| 31 | ST | 63 | M | 35 | 95 | − | − | 1 | 27.73 |

| 32 | ND | 67 | F | TH | TH | − | − | 2 | 38.00 |

Note: + indicates the presence of disease; − indicates the absence of disease.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; F, female; M, male; ND, not determined; NS, nonstiff patient; ROM, range of motion; ST, stiff patient; TH, telehealth visit.

2.2. Evaluation of joint stiffness parameters

The treating surgeon performed a postoperative clinical evaluation for passive forward elevation and passive external rotation at 2, 6, 12, and 24 weeks. A stiff (ST) shoulder cohort was defined as patients with passive external rotation <30° or passive forward elevation <120° at the 12‐week visit. A nonstiff (NS) shoulder cohort included patients with these parameters exceeding the set thresholds. In one patient (Table 1, ID#32), a 12‐week evaluation was performed during the telehealth (TH) visit due to COVID‐19‐related restrictions.

2.3. Tissue collection and isolation of cells

Multiple capsular tissue samples were obtained from the rotator interval during the diagnostic arthroscopy. Subsequently, the tissues were digested with bacterial collagenase (Collagenase Type 2; Worthington Biochemical Corporation) for 18 h at 37°C. Then, fibroblasts were separated from tissue debris by filtration. The fibroblasts were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Corning Inc.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gemini Bio‐Products). After reaching confluence, cells were collected and stored in liquid nitrogen until ready for analysis.

2.4. Fibroblasts culture in the presence of TGFβ1

To study the behavior of patient‐derived fibroblasts in the profibrotic environment, we cultured them in the presence of TGFβ1. 15 Corresponding cells cultured in the absence of TGFβ1 served as control. In brief, fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS until they reached ∼80% confluency. Subsequently, the cell layers were washed with phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) and cultured for 24 h in DMEM supplemented with 10% NuSerum (Corning Inc.). Next, a fresh medium containing 40 µg/mL of l‐ascorbic acid phosphate magnesium salt n‐hydrate (WAKO Inc.) was added to the cells for 5 h. Then, the medium was replaced with the fresh portion supplemented with TGFβ1 (R&D Systems) and added to the final concentration of 10 ng/mL. After 24 h, cell lysates were collected (see below).

2.5. Western blot assays of selected markers associated with fibrotic scarring

At the end of the culture, cell layers were washed with cold PBS. Next, the cell lysates were prepared from each cell culture dish. The protein concentration in the lysates was determined using the Bradford assay (Bio‐Rad Laboratories). Subsequently, 10‐µg protein samples were loaded onto polyacrylamide gels. Following electrophoretic separation, the proteins of interest were assayed using quantitative Western blot (QWB) assays using an infrared detection system (LI‐COR Biotechnology).

We rationally selected protein markers associated with the formation of collagen‐rich fibrotic scars. In particular, we were interested in the production of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), whose expression is stimulated by TGFβ1‐dependent pathways. 16 , 17 TGFβ1 is the master regulator of fibrotic scar formation in many tissues, including those forming joints. 10 , 18 , 19 In addition to being a strong stimulator of cell proliferation, TGFβ1 activates the biosynthesis of crucial extracellular matrix (ECM) components, including procollagen I and fibronectin. TGFβ1 acts by inducing CTGF, which is upregulated in many fibrotic disorders. Consequently, CTGF acts as the mediator of TGFβ1 activities. 17

To study the differentiation of fibroblasts into profibrotic myofibroblasts, we assayed the expression of α smooth muscle actin (αSMA). Additionally, we examined differences in the expression of crucial structural proteins that form the scar tissue, including collagen I and fibronectin. Finally, we analyzed the production of prolyl 4‐hydroxylase (P4H) and heat shock protein 47 (HSP47), essential proteins needed for the proper folding, stability, and secretion of procollagen I.

We measured glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) in each sample as an internal reference. Using secondary antibodies conjugated with different infrared dyes allowed us to detect a target protein and GAPDH simultaneously. Table 2 presents the antibodies we employed in our assays.

Table 2.

Antibodies used in quantitative Western blot assays.

| Target and corresponding GAPDH reference | Primary antibody (supplier; dilution used) | Secondary antibody (antibodies purchased in LI‐COR Biosciences; used in 1:15,000 dilution) |

|---|---|---|

| P4HA1 |

Rabbit anti‐P4HA1; LSBio Inc.; 1:500 |

Anti‐rabbit (IRDye800CW) |

| GAPDH |

Mouse anti‐GAPDH; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.; 1:1000 |

Anti‐mouse (IRDye680RD) |

| HSP47 |

Mouse anti‐HSP47; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.; 1:500 |

Anti‐mouse (IRDye800CW) |

| GAPDH |

Chicken anti‐GAPDH; Abcam; 1:2000 |

Anti‐chicken (IRDye680RD) |

| CTGF |

Rabbit anti‐CTGF; Abcam; 1:1000 |

Anti‐rabbit (IRDye800CW) |

| GAPDH |

Mouse anti‐GAPDH; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.; 1:1000 |

Anti‐mouse (IRDye680RD) |

| αSMA |

Mouse anti‐αSMA; Abcam; 1:500 |

Anti‐mouse (IRDye800CW) |

| GAPDH |

Chicken anti‐GAPDH; Abcam; 1:2000 |

Anti‐chicken (IRDye680RD) |

| Collagen I |

Rabbit anti‐Col1 (R69); in house; 1:2000 |

Anti‐rabbit (IRDye800CW) |

| GAPDH |

Mouse anti‐GAPDH; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.; 1:1000 |

Anti‐mouse (IRDye680RD) |

| Fibronectin |

Mouse anti‐fibronectin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.; 1:500 |

Anti‐mouse (IRDye800CW) |

| GAPDH |

Chicken anti‐GAPDH; Abcam; 1:2000 |

Anti‐chicken (IRDye680RD) |

Abbreviations: CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; HSP47, heat shock protein 47; P4H, prolyl 4‐hydroxylase; αSMA, α smooth muscle actin.

2.6. Quantification of fibrosis‐associated markers

Following Western blot, we employed Odyssey CLx infrared imaging system (LI‐COR Biotechnology) to visualize specific protein bands and measured their signal intensities using Image Studio software v. 5.2.5 (LI‐COR Biotechnology). The signal intensity values were normalized using GAPDH‐specific bands as the internal reference. Subsequently, we documented signal intensities of protein‐specific bands associated with the (+)TGFβ1 and the (−)TGFβ1 cell groups in a graphic form (OriginPro, version 2021b; OriginLab Corp.). All QWB measurements were done within the linear detection ranges determined in advance for each antibody used here.

A one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine whether the relative amounts of analyzed proteins calculated for the (+)TGFβ1 group and the (−)TGFβ1 group of corresponding fibroblasts isolated from a patient differed significantly (IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 27; IBM Corp.).

For each fibroblast set from a specific patient, we calculated the ratios of normalized signal intensities of corresponding protein bands associated with the (+)TGFβ1 and the (−)TGFβ1 conditions. We compared these ratios calculated for the ST and the NS shoulder groups for each protein using a one‐way ANOVA. For instance, we calculated the ratio of the signal intensities of the collagen I‐specific bands associated with fibroblasts cultured in the (+)TGFβ1 condition and the corresponding bands related to the (−)TGFβ1 condition. In all assays, statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05.

2.7. Kinetics of procollagen I secretion

Fibroblasts were grown to confluence in 10‐cm tissue culture plates. Subsequently, the cell layers were washed with PBS. Then, each plate was filled with 7 mL of fresh DMEM medium containing 40 µg/mL of l‐ascorbic acid phosphate magnesium salt n‐hydrate. Fibroblasts from each patient were cultured with or without 10 ng/mL of TGFβ1. At defined time points, 50‐µL samples were withdrawn from the media. Subsequently, the samples were processed for polyacrylamide electrophoresis. Procollagen I present in cell culture media was detected by QWB with the anti‐pro‐α1(I) chain primary antibody, as described. 20 Signal intensities of protein bands corresponding to intact and partially processed procollagen α1(I) chain were measured. Subsequently, results were normalized to the 1‐h data point. Normalized data were plotted against time and fitted to the linear model (GraphPad Prism, version 6.07; GraphPad Software Inc.). The slopes of the fitted curves represented an hourly rate of secretion of procollagen I. The significance of differences between the (+)TGFβ1 and the (−)TGFβ1 groups was analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.07. We expressed the procollagen secretion rates in arbitrary units (au)/h.

2.8. Collagen gel contraction

To analyze the contractility (a parameter that increases in many fibrotic conditions) of patients' fibroblasts from the ST and NS groups cultured in the presence or the absence of TGFβ1, we employed a collagen gel contraction assay. 21 In brief, confluent fibroblasts were detached from cell culture dishes. Then 100‐µL samples containing 3 × 106 cells were mixed with 400 µL of a neutral collagen solution containing 3 mg/mL of collagen I (BD Biosciences). Individual 500‐µL samples were poured into separate wells of a 24‐well plate. Then the cell‐gel construct was allowed to polymerize at 37°C. Subsequently, the polymerized collagen discs were lifted from the wells' bottoms. Floating, cell‐loaded collagen discs were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% NuSerum in the presence (10 ng/mL) or absence of TGFβ1. The disc images were captured at designated time points, and then their surface areas were calculated. Finally, the dynamics of gel contraction were documented graphically as the time‐disc surface area relation. We applied repeated measures ANOVA, with a Greenhouse‐Geisser correction, to evaluate the discs' surface changes across various time points (IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 27; IBM Corp.).

2.9. Statistical tests

To determine the number of patients required for our study, we employed a sample size estimation test used in the previous prevalence studies. 22 , 23 On the basis of the literature, we expected to find postoperative frozen‐shoulder cases in 15% of patients. 4 , 5 Consequently, for the expected prevalence of 15%, the required sample size was 29 for the margin of error or absolute precision of ±13% in estimating the prevalence with 95% confidence. With this sample size, the anticipated 95% CI was (2%, 28%).

Analysis of differences in the expression of protein markers in fibroblasts isolated from NS and ST patients was performed using two‐sided one‐way ANOVA (IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 27, IBM Corp.). The significance of differences between the kinetics of procollagen secretion, represented by the slopes of the fitted curves, was analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 6.07 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

To evaluate differences in the collagen disc contractures, we applied repeated measures ANOVA, with a Greenhouse‐Geisser correction, to evaluate the discs' surface changes across various time points (IBM SPSS Statistic for Windows, version 27, IBM Corp.).

Our statistical analyses' results were presented in the form of graphs, tables, and descriptive statistics. In all assays, statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients

We analyzed 32 patients who underwent shoulder surgery (Table 1). One patient (Table 1, ID#32) was excluded from the study because the 12‐week evaluation was done via TH visit due to COVID‐19 restrictions.

Among 31 included patients, 26% were females, and 74% were males. Six patients (19%) met the criteria for the ST shoulder cohort. The average age for the NS group was 60 years (standard deviation, SD ± 9.6), and for the ST group, 61.1 (SD ± 3.4). Within the NS group, 24% of patients were females, and the corresponding value in the ST group was 33%. On average, the patients from the NS group had 2.0 (SD ± 0.7) tendons torn. The corresponding value for the ST group was 1.7 (SD ± 0.8). Thyroid disorder was diagnosed in 12% of NS patients and none of the ST patients. Diabetes was diagnosed in 40% of NS patients and 16.7% of ST patients. On average, the body mass index (BMI) for the NS group was 33 kg/m2 (SD ± 7.5), and for the ST group, 26.5 kg/m2 (SD ± 3.0).

3.2. Markers associated with procollagen biosynthesis

Utilizing fibroblasts isolated from the patients' tissues before surgery, we studied the production of crucial proteins needed to form collagen‐rich deposits ultimately responsible for the stiffening of the arthrofibrotic joints. 10 We analyzed rationally selected markers associated directly with increased production of the collagen‐rich ECM needed to restore the integrity of wounded sites. In particular, we focused on the production of procollagen I and the crucial auxiliary elements needed for its proper folding, stability, and secretion into the extracellular space.

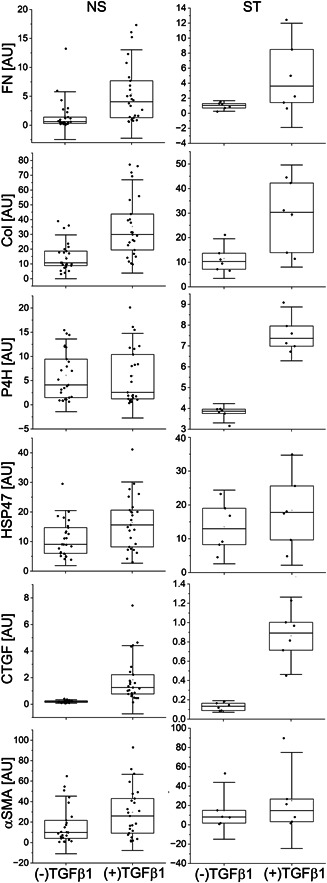

In the baseline conditions, that is, in the absence of TGFβ1, the expression of analyzed markers was higher in the NS group than in the ST group, albeit with no statistical significance (Figure 1, Table 3). Except for P4H produced by fibroblasts derived from the NS patients, TGFβ1 increased the production of all analyzed markers in the NS and ST fibroblasts (Figure 1, Table 3).

Figure 1.

Box plot representations of relative amounts of proteins associated with the scar formation produced by patient‐derived fibroblasts in the presence or the absence of TGFβ1. Results are based on QWB data normalized to the glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase‐specific signal. The interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles determines each box. The lines within the boxes represent the medians, while the whiskers delineate the SD values. COL, collagen I; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; FN, fibronectin; HSP47, heat shock protein 47; NS, proteins produced by fibroblasts from nonstiff‐shoulder patients; P4H, prolyl 4‐hydroxylase; QWB, quantitative Western blot; ST, proteins produced by fibroblasts from stiff‐shoulder patients; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; αSMA, α smooth muscle actin; (+)TGF and (−)TGF, cell culture conditions indicating the presence or the absence of TGFβ1.

Table 3.

A summary of relative amounts of analyzed proteins, represented by pixel‐intensity strengths, produced by NS‐derived and ST‐derived fibroblasts cultured in the presence or the absence of TGFβ1.

| Group | Marker |

Protein markers GAPDH‐normalized QWB signal strength (±SD) |

Statistical testing of differences between the GAPDH‐normalized QWB signal strengths in (+)TGFβ1 and (−)TGFβ1 groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (+)TGFβ1 | (−)TGFβ1 | |||

| NS, n = 25 | FN | 5.40 ± 5.10 | 1.67 ± 2.75 | F(1, 50) = 10.8, p = 0.002 |

| COL | 35.09 ± 20.65 | 15.03 ± 9.74 | F(1, 50) = 20.1, p < 0.0001 | |

| P4H | 6.22 ± 5.81 | 6.07 ± 4.90 | F(1, 50) = 0.01, p = 0.921 | |

| HSP47 | 16.17 ± 9.11 | 11.30 ± 6.13 | F(1, 50) = 6.3, p = 0.015 | |

| CTGF | 1.90 ± 1.70 | 0.20 ± 0.08 | F(1, 50) = 25.7, p < 0.0001 | |

| αSMA | 31.30 ± 26.06 | 19.85 ± 22.86 | F(1, 50) = 2.8, p = 0.099 | |

| ST, n = 6 | FN | 5.05 ± 4.62 | 0.97 ± 0.47 | F(1, 10) = 4.6, p = 0.057 |

| COL | 28.79 ± 13.85 | 11.52 ± 5.37 | F(1, 10) = 8.1, p = 0.017 | |

| P4H | 7.58 ± 0.86 | 3.76 ± 0.31 | F(1, 10) = 104.6, p < 0.0001 | |

| HSP47 | 18.43 ± 10.84 | 13.49 ± 7.26 | F(1, 10) = 0.86, p = 0.375 | |

| CTGF | 0.86 ± 0.27 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | F(1, 10) = 44, p < 0.0001 | |

| αSMA | 25.08 ± 33.14 | 14.45 ± 19.64 | F(1,10) =0.46, p = 0.514 | |

Abbreviations: COL, collagen I; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; FN, fibronectin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; HSP47, heat shock protein 47; NS, nonstiff patients; P4H, a catalytic unit of prolyl 4‐hydroxylase; QWB, quantitative Western blot; SD, standard deviation; ST, stiff patients; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; αSMA, α smooth muscle actin.

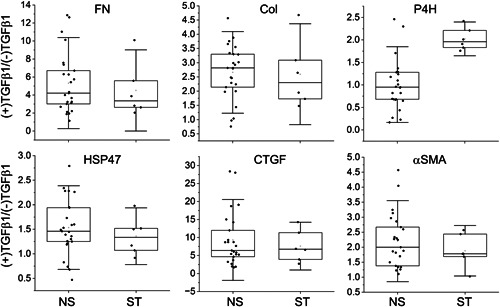

To determine the production increase extent for each patient, we also calculated the ratios of the markers produced in the presence of TGFβ1 and the corresponding markers produced in its absence. Subsequently, we compared the matching ratios calculated for the ST and NS groups for each protein marker. We observed that the extent of TGFβ1‐dependent production of P4H in the ST group was significantly greater than that observed in the NS group (Figure 2, Table 4). Since the above results were obtained with cell lysates, measured parameters mainly represent the intracellular pool of analyzed proteins.

Figure 2.

The ratios of proteins produced by the NS or the ST fibroblasts in the presence or the absence of TGFβ1. The interquartile range between the 25th and 75th percentiles determines each box. The lines represent the medians, while the whiskers delineate the SD values. COL, collagen I; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; FN, fibronectin; HSP47, heat shock protein 47; NS, proteins produced by fibroblasts from nonstiff‐shoulder patients; P4H, prolyl 4‐hydroxylase; ST, proteins produced by fibroblasts from stiff‐shoulder patients; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; αSMA, α smooth muscle actin; (+)TGF and (−)TGF, cell culture conditions indicating the presence or the absence of TGFβ1.

Table 4.

A summary of measurements of the ratios of QWB‐based protein bands' GAPDH‐normalized signals.

| Marker | Ratios of protein markers' signal strengths seen in Table 3 measured in (+)TGFβ1 and (−)TGFβ1 conditions in the NS and ST groups (±SD) | Statistical testing of the differences between the (+)TGFβ1/(−)TGFβ1 ratios in the NS and ST groups | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NS, n = 25 | ST, n = 6 | ||

| FN | 5.2 ± 3.3 | 4.5 ± 3.0 | F(1, 30) = 0.22, p = 0.641 |

| COL | 2.6 ± 1.0 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | F(1, 30) = 0.002, p = 0.969 |

| P4H | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | F(1, 30) = 15.9, p < 0.0005 |

| HSP47 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | F(1, 30) = 0.55, p = 0.464 |

| CTGF | 9.5 ± 7.4 | 7.6 ± 4.4 | F(1, 30) = 0.36, p = 0.554 |

| αSMA | 2.2 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.6 | F(1, 30) = 0.47, p = 0.498 |

Note: Each ratio was calculated for corresponding proteins produced by the same fibroblasts cultured in the presence or the absence of TGFβ1.

Abbreviations: COL, collagen I; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; FN, fibronectin; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3‐phosphate dehydrogenase; HSP47, heat shock protein 47; NS, nonstiff patients; P4H, a catalytic unit of prolyl 4‐hydroxylase; QWB, quantitative Western blot; ST, stiff patients; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1; αSMA, α smooth muscle actin.

3.3. Procollagen secretion

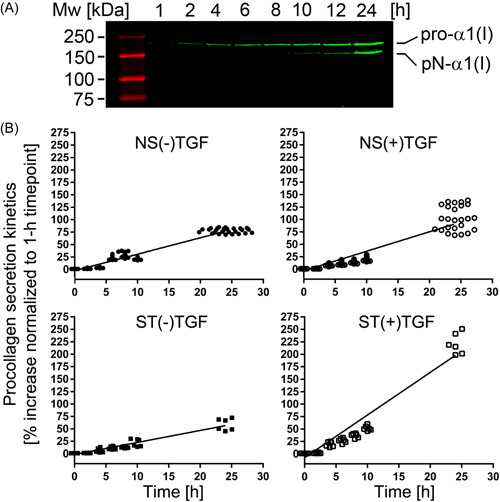

The secretion of procollagen molecules into the extracellular space depends on their proper triple‐helical structure and thermostability. While correctly folded molecules are secreted efficiently, those misfolded are not. Here, we compared the secretion rates of procollagen I produced by fibroblasts derived from the NS and ST patients. As indicated in Figure 3, the difference in the secretion rates measured for the (+)TGFβ1 (4.3 au/h) and the (−)TGFβ1 (3.2 au/h) groups from the NS pool was relatively small (F(1, 360) = 60.311, p < 0.0001). In contrast, with 9.5 au/h for the (+)TGFβ1 group and 2.5 au/h for the (−)TGFβ1, the difference between the corresponding rates associated with the ST‐derived fibroblasts was markedly greater (F(1, 80) = 321.1, p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

(A) A representative Western blot image of procollagen I secreted into cell culture media during indicated time intervals. Intact pro‐α1(I) chains and partially processed pN‐α1(I) chains are visible. (B) Individual graphs representing the procollagen I secretion rates for the NS and ST fibroblasts grown in the absence or the presence of TGFβ1. NS, nonstiff patients; ST, stiff patients; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1.

3.4. Fibroblast‐induced gel contraction

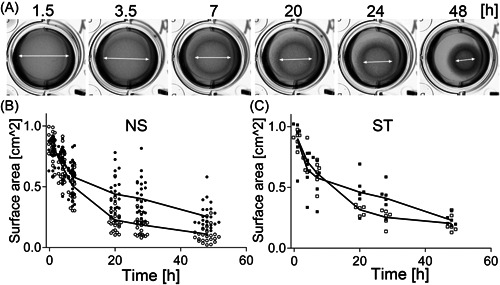

Utilizing collagen‐based matrices, we measured the contractile behavior of the NS and ST fibroblasts cultured in the presence and the absence of TGFβ1 for 48 h (Figure 4). Using repeated‐measures ANOVA, we demonstrated significant between‐subject TGFβ1‐dependent changes in the discs' surface areas across time points analyzed in the NS group (F(1, 50) = 32.9, p < 0.0001). These measures indicate that the NS‐derived fibroblasts increased their contractility in the TGFβ1 presence. In contrast, the between‐subject comparison indicated that there were no significant TGFβ1‐dependent changes in the discs' surface areas across time points analyzed in the ST group (F(1, 10) = 0.426, p = 0.529) (Figure 4). The within‐subject changes measured across time points were significant in the NS and ST (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Analysis of collagen gel contracture by the NS and the ST fibroblasts cultured in the presence and the absence of TGFβ1. (A) Representative images of the fibroblasts‐populated collagen gels observed at indicated time points; arrows indicate changes in the discs' diameters. (B, C) Graphic representations of the changes of the surface areas of the collagen gel discs populated with the NS fibroblasts (B) or ST fibroblasts (C) grown in the presence (open symbols) or the absence (closed symbols) of TGFβ1. NS, nonstiff patients; ST, stiff patients; TGFβ1, transforming growth factor β1.

4. DISCUSSION

Although standard and fibrotic scars comprise many similar structural proteins, a significant content of collagen I‐rich fibrils is a hallmark of posttraumatic arthrofibrosis. 10 , 13 In the exploratory study presented here, we confirmed our hypothesis that collagen‐producing machinery in patients that develop ST shoulders differs from that in patients that do not meet ST shoulder parameters.

The biosynthesis of collagen I molecules and their assembly into fibrils include complex intracellular and extracellular processes. 12 Many auxiliary proteins participate in these processes, including enzymes that catalyze posttranslational modifications of nascent procollagen I chains and protein chaperones that enable proper collagen folding. 24

Among these auxiliary proteins, P4H plays a central role. Its central function is to hydroxylate selected proline residues to enable proper folding, thermostability, and efficient secretion of procollagen triple‐helical molecules.

This enzyme, consisting of two catalytic α subunits and two noncatalytic β subunits, requires nascent procollagen α chains as a substrate and Fe2+, 2‐oxoglutarate, molecular O2, and ascorbate cosubstrates. 12 The β subunits also function as protein chaperones and disulfide isomerase. 24 , 25 Simultaneously with their hydroxylation, procollagen chains fold into the triple‐helical structure in a process controlled by collagen‐specific chaperones, most notably HSP47. 26

Upregulation of the fibril‐forming procollagens' expression, particularly procollagen I, seen in fibrotic disorders, creates a high demand for procollagen‐modifying enzymes and chaperones. Consequently, in many fibrotic conditions, the production of these elements is also upregulated. For instance, studies demonstrated a significant production increase of P4H subunits and HSP47 in rabbit models of arthrofibrosis and neural scarring. 10 , 27 , 28 , 29

Here, we analyzed the production of these crucial proteins in fibroblasts derived from patients who developed ST shoulders following surgery and those who did not. First, we tested the validity of our model to represent the profibrotic behavior of isolated fibroblasts treated with TGFβ1.

Our demonstration of the increased CTGF production in the TGFβ1‐stimulated fibroblasts validates their profibrotic behavior in the in vitro experimental system employed here. Furthermore, the apparent increase of αSMA production in these fibroblasts indicates their fibrotic phenotype. 30 , 31

These results indicate that our model is consistent with other models that utilize TGFβ1 to mimic crucial processes associated with the profibrotic response of fibroblasts. 32 , 33

QWB analyses demonstrated that fibronectin and procollagen I production increased in the TGFβ1‐stimulated cells. However, the extent of this stimulation did not differ between the NS and the ST shoulder groups. Hence, with a similar increase in the production of collagen and fibronectin fundamental question arose: Why did the patients from the ST group develop substantial shoulder stiffness?

Trying to answer this question, we focused on crucial posttranslational factors that facilitate procollagen production and secretion into the extracellular space, putting aside other potential contributors to joint stiffening, including the extent of injury and inflammation, adherence to the physical therapy regimen, and the genetic background.

The production levels of one of these factors, HSP47, in the TGFβ1‐stimulated fibroblasts derived from the NS and the ST patients were similar. Although increased production of this protein chaperone is upregulated in many fibrotic disorders, including arthrofibrosis, based on our results, we do not expect that this protein was the pivotal component that facilitated the development of excessive scarring in ST patients. 10 , 34

In contrast, compared to the NS patients, the expression of P4H increased significantly in the TGFβ1‐stimulated fibroblasts derived from the ST patients. This increase was associated with the fast rates of procollagen secretion into the extracellular space. We postulate that this increase may indicate that P4H is a vital element of a mechanism that pushes the healing toward excessive scar formation and arthrofibrosis.

Regardless of the fibrotic status of the neotissue formed in response to injury, the fibroblasts present at the injury sites have the challenging task of producing relatively large amounts of collagen molecules and other ECM proteins needed for tissue repair. A few mechanisms accelerate the production of these proteins. They include an increased proliferation of cells, enhanced transcription of specific genes, and rapid transport of proteins destined for the ECM.

Similar to wound healing, there is a high demand for collagen production during the rapid embryonic growth of connective tissues, as illustrated by Schwarz, who used the avian tendon as an example. This study demonstrated that procollagen contributes over 50% to the pool of proteins produced by embryonic tenocytes during tendon development. 35

Although amplification of single‐copy collagen genes by multiple corresponding copies of messenger RNA (mRNA) compensates for the limited translation rate, this compensation is insufficient to keep up with the need for the amount of collagen required to form neotissue. In physiological conditions, ascorbic acid acts as the inducer of transcription, increasing mRNA production and its half‐life by about sixfold. 36 , 37 Still, with accelerated biosynthesis of the nascent procollagen α chains, there is a need for their rapid posttranslational modifications, folding into functional triple‐helical structures, and secretion from the cells. Studies demonstrated that P4H plays a central role in all these processes. 35 P4H facilitates the formation of thermostable collagen triple helices by hydroxylating selected proline residues in the collagen chains. Unlike single procollagen chains, triple‐helical molecules enter the fast secretion route, thereby accelerating the delivery of the scar‐building material into the extracellular space. 38 , 39

Moreover, having a low binding affinity to the triple‐helical collagen structure, P4H dissociates rapidly upon triple‐helix formation and returns to the free enzyme pool. 40 , 41 While there, P4H is again available for binding to the nascent procollagen molecules for which it has a strong binding affinity.

Biological models also indicate that by accelerating the folding and secretion of procollagen molecules, P4H increases the translation rates. 35 Furthermore, the ability of P4H to bind underhydroxylated procollagen chains and retain them within the endoplasmic reticulum renders this enzyme an essential element of the quality control system that limits the secretion of nonfunctional procollagen molecules. 42

Our observation of the TGFβ1‐dependent stimulation of the P4H production in the ST patients is consistent with the TGFβ1‐P4H axis observed in other fibrotic conditions. For instance, TGFβ1‐dependent upregulation of P4H was observed in experimental lung fibrosis and lung tissue isolated from patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. 43 Moreover, we observed an increased production of this enzyme in vivo in experimental arthrofibrosis and excessive scarring of peripheral nerves. 10 , 29 Because of its profibrotic role, scientists consider P4H an attractive antifibrotic target. 44 , 45

Unlike the NS fibroblasts, our observation that stimulating the ST‐derived fibroblasts with TGFβ1 did not significantly increase contractility was somewhat surprising. Studies demonstrated that TGFβ1 increases fibroblasts' contractility in vivo during wound healing and in vitro in models similar to that employed here. 46 , 47 The ability of activated fibroblasts to contract wounds is a vital element of a proper healing process. Alterations of wound contracture may delay healing, prolong inflammation, and increase fibrosis chances. Further studies are warranted to explain the unusual contractile behavior of TGFβ1‐stimulated ST fibroblasts. These studies should consider our observation of a similar, about a twofold increase in the production of αSMA in TGFβ1‐stimulated NS and ST fibroblasts (Table 4).

Here, we had a unique opportunity to study cells from shoulder injury sites and, based on clinical data, categorize them associated with the NS shoulder and the ST shoulder groups. We determined that among rationally selected proteins associated with the formation of collagen‐rich deposits, P4H was the only one whose production increased significantly in the TGFβ1‐stimulated ST‐derived fibroblasts versus TGFβ1‐stimulated NT‐derived fibroblasts. This observation suggests that P4H may be a vital mechanism element that incites arthrofibrotic response following a shoulder injury.

Our study had limitations. First, the criteria for defining the ST versus NS shoulder conditions were binary, so they did not recognize the shoulder stiffness spectrum. Hence, we do not expect a specific threshold value for the P4H production increase above which patients develop the ST‐shoulder condition and below which they do not. Second, our study focused only on rationally‐selected proteins associated with collagen‐rich scar production. For instance, we did not consider additional protein chaperones indicated in procollagen production, including BiP, CyPB, and FKBP65. 48 , 49 , 50

Similarly, we did not analyze the expression of prolyl 3‐hydroxylase that modifies one proline residue in procollagen I. 51 Finally, we did not consider other factors that might have contributed to arthrofibrosis seen in the ST group. In particular, the extent of injury, duration of the inflammatory response, BMI, and adherence to prescribed physical therapy could impact the extent of ST‐shoulder development. Furthermore, future studies should consider analyses of tissue biopsies collected after the completion of wound healing.

In addition, since no prior data were available for analyzed parameters in patients with arthrofibrosis, our study could be underpowered. Using existing data, however, we performed a power analysis for the prevalence to ensure that our group would include NS and ST patients. Still, due to funding constraints, we applied analysis parameters, mainly precision, with a relatively low stringency.

In conclusion, despite these limitations, we demonstrated a specific difference between the TGFβ1‐dependent P4H expression in fibroblasts isolated from the ST and the NS groups. Consequently, our study results may suggest the existence of inherent biological characteristics that contribute to the development of posttraumatic arthrofibrosis in some patients.

Further studies examining the TGFβ1‐dependent regulation of P4H expression are warranted to fully comprehend the role of this enzyme in excessive fibrotic healing. With data obtained in our exploratory studies presented here, future confirmatory research is now feasible using parameters for properly powered groups.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Benjamin A. Hendy: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; resources; writing—review and editing. Jolanta Fertala: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; software; validation; writing—original draft. Thema Nicholson: Data curation; project administration; writing—review and editing. Joseph A. Abboud: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; resources; validation; writing—review and editing. Surena Namdari: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; resources; validation; writing—review and editing. Andrzej Fertala: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; methodology; project administration; resources; software; supervision; validation; writing—original draft. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The lead author Andrzej Fertala affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Pamela Walter for revising the article. This study was funded in part by a Joan and John Mullen Spine Injury Research Innovation Fund awarded to TJU. Here, the fund was primarily used for experimental data collection.

Hendy BA, Fertala J, Nicholson T, Abboud JA, Namdari S, Fertala A. Profibrotic behavior of fibroblasts derived from patients that develop posttraumatic shoulder stiffness. Health Sci Rep. 2023;6:e1100. 10.1002/hsr2.1100

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Dr. Andrzej Fertala had full access to all of the data in this study and has taken complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sojbjerg JO. The stiff elbow. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:626‐631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen AF, Lee YS, Seidl AJ, Abboud JA. Arthrofibrosis and large joint scarring. Connect Tissue Res. 2019;60:21‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheuy VA, Foran JRH, Paxton RJ, Bade MJ, Zeni JA, Stevens‐Lapsley JE. Arthrofibrosis associated with total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2604‐2611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koorevaar RCT, van‘t Riet E, Ipskamp M, Bulstra SK. Incidence and prognostic factors for postoperative frozen shoulder after shoulder surgery: a prospective cohort study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137:293‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brislin KJ, Field LD, Savoie FH, 3rd . Complications after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:124‐128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Redler LH, Dennis ER. Treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27:e544‐e554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hildebrand KA, Zhang M, Hart DA. Myofibroblast upregulators are elevated in joint capsules in posttraumatic contractures. Clin Orthop Related Res. 2007;456:85‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hildebrand KA, Zhang M, Hart DA, et al. Joint capsule mast cells and neuropeptides are increased within four weeks of injury and remain elevated in chronic stages of posttraumatic contractures. J Orthop Res. 2008;26:1313‐1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Monument MJ, Hart DA, Befus AD, Salo PT, Zhang M, Hildebrand KA. The mast cell stabilizer ketotifen reduces joint capsule fibrosis in a rabbit model of post‐traumatic joint contractures. Inflamm Res. 2012;61:285‐292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Steplewski A, Fertala J, Beredjiklian PK, et al. Auxiliary proteins that facilitate formation of collagen‐rich deposits in the posterior knee capsule in a rabbit‐based joint contracture model. J Orthop Res. 2016;34:489‐501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Le HV, Lee SJ, Nazarian A, Rodriguez EK. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: review of pathophysiology and current clinical treatments. Shoulder Elbow. 2017;9:75‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prockop DJ, Kivirikko KI. Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:403‐434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Steplewski A, Fertala J, Beredjiklian PK, et al. Blocking collagen fibril formation in injured knees reduces flexion contracture in a rabbit model. J Orthop Res. 2017;35:1038‐1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Steplewski A, Fertala J, Tomlinson RE, et al. Mechanisms of reducing joint stiffness by blocking collagen fibrillogenesis in a rabbit model of posttraumatic arthrofibrosis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0257147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xu Q, Norman JT, Shrivastav S, Lucio‐Cazana J, Kopp JB. In vitro models of TGF‐β‐induced fibrosis suitable for high‐throughput screening of antifibrotic agents. Am J Physiol‐Renal Physiol. 2007;293:F631‐F640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim KK, Sheppard D, Chapman HA. TGF‐β1 signaling and tissue fibrosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a022293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ihn H. Pathogenesis of fibrosis: role of TGF‐β and CTGF. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2002;14:681‐685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hildebrand KA, Zhang M, Germscheid NM, Wang C, Hart DA. Cellular, matrix, and growth factor components of the joint capsule are modified early in the process of posttraumatic contracture formation in a rabbit model. Acta Orthop. 2008;79:116‐125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Epstein FH, Border WA, Noble NA. Transforming growth factor β in tissue fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1286‐1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fertala J, Steplewski A, Kostas J, et al. Engineering and characterization of the chimeric antibody that targets the C‐terminal telopeptide of the α2 chain of human collagen I: a next step in the Quest to reduce localized fibrosis. Connect Tissue Res. 2013;54:187‐196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Steplewski A, Fertala J, Beredjiklian P, Wang ML, Fertala A. Matrix‐specific anchors: a new concept for targeted delivery and retention of therapeutic cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2015;21:1207‐1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arya R, Antonisamy B, Kumar S. Sample size estimation in prevalence studies. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1482‐1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Naing L, Nordin RB, Abdul Rahman H, Naing YT. Sample size calculation for prevalence studies using Scalex and ScalaR calculators. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2022;22:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Prockop DJ, Berg RA, Kivirikko KI, Uitto J. Intracellular steps in the biosynthesis of collagen. In: Ramachandran GN, Reddi AH, eds. Biochemistry of Collagen. Plenum; 1976:163‐237. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Myllyharju J. Collagens, modifying enzymes and their mutations in humans, flies and worms. Trends Genet. 2004;20:33‐43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tasab M, Batten MR, Bulleid NJ. Hsp47: a molecular chaperone that interacts with and stabilizes correctly‐folded procollagen. EMBO J. 2000;19:2204‐2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Naitoh M, Hosokawa N, Kubota H, et al. Upregulation of HSP47 and collagen type III in the dermal fibrotic disease, keloid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;280:1316‐1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fertala J, Rivlin M, Wang ML, Beredjiklian PK, Steplewski A, Fertala A. Collagen‐rich deposit formation in the sciatic nerve after injury and surgical repair: a study of collagen‐producing cells in a rabbit model. Brain Behav. 2020;10:e01802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rivlin M, Miller A, Tulipan J, et al. Patterns of production of collagen‐rich deposits in peripheral nerves in response to injury: a pilot study in a rabbit model. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hinz B. Myofibroblasts. Exp Eye Res. 2016;142:56‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schuster R, Rockel JS, Kapoor M, Hinz B. The inflammatory speech of fibroblasts. Immunol Rev. 2021;302:126‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Frangogiannis N. Transforming growth factor‐beta in tissue fibrosis. J Exp Med. 2020;217:e20190103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meng X, Nikolic‐Paterson DJ, Lan HY. TGF‐β: the master regulator of fibrosis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12:325‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Taguchi T, Razzaque MS. The collagen‐specific molecular chaperone HSP47: is there a role in fibrosis? Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:45‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schwarz RI. Collagen I and the fibroblast: high protein expression requires a new paradigm of post‐transcriptional, feedback regulation. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2015;3:38‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rowe LB, Schwarz RI, Rowe LB, Schwarz RI. Role of procollagen mRNA levels in controlling the rate of procollagen synthesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:241‐249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lyons BL, Schwarz RI. Ascorbate stimulation of PAT cells causes an increase in transcription rates and a decrease in degradation rates of procollagen mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:2569‐2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kao WW, Prockop DJ, Berg RA. Kinetics for the secretion of nonhelical procollagen by freshly isolated tendon cells. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:2234‐2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kao WW, Berg RA, Prockop DJ. Kinetics for the secretion of procollagen by freshly isolated tendon cells. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:8391‐8397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berg RA, Prockop DJ. The thermal transition of a non‐hydroxylated form of collagen. Evidence for a role for hydroxyproline in stabilizing the triple‐helix of collagen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;52:115‐120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Murphy L, Rosenbloom J. Evidence that chick tendon procollagen must be denatured to serve as substrate for proline hydroxylase. Biochem J. 1973;135:249‐251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Walmsley AR, Batten MR, Lad U, Bulleid NJ. Intracellular retention of procollagen within the endoplasmic reticulum is mediated by prolyl 4‐hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14884‐14892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Luo Y, Xu W, Chen H, et al. A novel profibrotic mechanism mediated by TGFβ‐stimulated collagen prolyl hydroxylase expression in fibrotic lung mesenchymal cells: mesenchymal TGFβ signalling and prolyl hydroxylase in lung fibrosis. J Pathol. 2015;236:384‐394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vasta JD, Andersen KA, Deck KM, Nizzi CP, Eisenstein RS, Raines RT. Selective inhibition of collagen prolyl 4‐hydroxylase in human cells. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:193‐199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vasta JD, Raines RT. Collagen prolyl 4‐hydroxylase as a therapeutic target. J Med Chem. 2018;61:10403‐10411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang TH, Thoreson AR, Gingery A, et al. Collagen gel contraction as a measure of fibroblast function in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103:574‐580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Desmoulière A, Geinoz A, Gabbiani F, Gabbiani G. Transforming growth factor‐beta 1 induces alpha‐smooth muscle actin expression in granulation tissue myofibroblasts and in quiescent and growing cultured fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:103‐111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Coss MC, Winterstein D, Raymond CS, 2nd , Simek SL. Molecular cloning, DNA sequence analysis, and biochemical characterization of a novel 65‐kDa FK506‐binding protein (FKBP65). J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29336‐29341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Smith T, Ferreira LR, Hebert C, Norris K, Sauk JJ. Hsp47 and cyclophilin B traverse the endoplasmic reticulum with procollagen into pre‐Golgi intermediate vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18323‐18328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Duran I, Martin JH, Weis MA, et al. A chaperone complex formed by HSP47, FKBP65, and BiP modulates telopeptide lysyl hydroxylation of type I procollagen. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:1309‐1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Vranka JA, Sakai LY, Bächinger HP. Prolyl 3‐hydroxylase 1, enzyme characterization and identification of a novel family of enzymes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:23615‐23621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Dr. Andrzej Fertala had full access to all of the data in this study and has taken complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.