ABSTRACT

Centrosome duplication and cell cycle progression are essential cellular processes that must be tightly controlled to ensure cellular integrity. Despite their complex regulatory mechanisms, microbial pathogens have evolved sophisticated strategies to co-opt these processes to promote infection. While misregulation of these processes can greatly benefit the pathogen, the consequences to the host cell can be devastating. During infection, the obligate intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis induces gross cellular abnormalities, including supernumerary centrosomes, multipolar spindles, and defects in cytokinesis. While these observations were made over 15 years ago, identification of the bacterial factors responsible has been elusive due to the genetic intractability of Chlamydia. Recent advances in techniques of genetic manipulation now allows for the direct linking of bacterial virulence factors to manipulation of centrosome duplication and cell cycle progression. In this review, we discuss the impact, both immediate and downstream, of C. trachomatis infection on the host cell cycle regulatory apparatus and centrosome replication. We highlight links between C. trachomatis infection and cervical and ovarian cancers and speculate whether perturbations of the cell cycle and centrosome are sufficient to initiate cellular transformation. We also explore the biological mechanisms employed by Inc proteins and other secreted effector proteins implicated in the perturbation of these host cell pathways. Future work is needed to better understand the nuances of each effector’s mechanism and their collective impact on Chlamydia’s ability to induce host cellular abnormalities.

KEYWORDS: centrosomes, cervical cancer, Chlamydia, ovarian cancer, secreted effector

INTRODUCTION

In order to proliferate, intracellular pathogens are tasked with co-opting host organelles and signaling pathways to carve out their unique niches within the host cell, events that are associated with disease. Manipulation of the cell cycle machinery is an evolved strategy increasingly found to be used by microbial pathogens to promote host colonization. The host cell cycle is a tightly regulated process involving the up- and downregulation of numerous proteins that drive phases in growth, acquisition of nutrients, replication of chromosomes, and ultimately segregation of the genetic material to opposite poles followed by a cytokinetic event resulting in two identical daughter cells. The cell cycle is marked by four phases: G1, S, G2, and M phases (1). G1 and G2 are gap phases during which the cell is preparing for either S or M phase, respectively. During S phase, DNA is replicated. M phase, or mitosis, is where the cell segregates genetic information and divides by cytokinesis into two daughter cells. The cell cycle is primarily driven forward by the upregulation and degradation of cyclin-dependent kinases and cyclin proteins (1).

Intimately related to cell cycle progression are centrosomes, which are the main microtubule organizing centers (MTOC) in eukaryotic cells. Centrosomes are not only important for proper spindle formation, but also ensure that the genetic material is equally segregated into the daughter cells during M phase. The role of centrosomes during M phase is well known, but they have also been implicated in direct regulation of the cell cycle (2). Centrosomes should only be duplicated once per cycle and cytokinesis should result in two identical daughter cells; however, this tightly controlled process can be subverted during oncogenesis or when the cell is occupied by a microbial pathogen. Pathogens often manipulate their host to promote their replication and avoid host defense mechanisms. While it is well documented that many viruses cause centrosome abnormalities (3–6) and alter cell cycle progression, it is also becoming clear that intracellular bacteria may be altering their host in similar, but distinct ways (7, 8).

In this review, we will discuss the regulation of centrosome duplication and how this process is hijacked during oncogenesis and microbial infection. Specifically, we discuss how Chlamydia trachomatis alters centrosome positioning, induces the formation of supernumerary centrosomes, multipolar spindles, and blocks cytokinesis with a specific focus on the secreted factors that are involved in producing these cellular abnormalities.

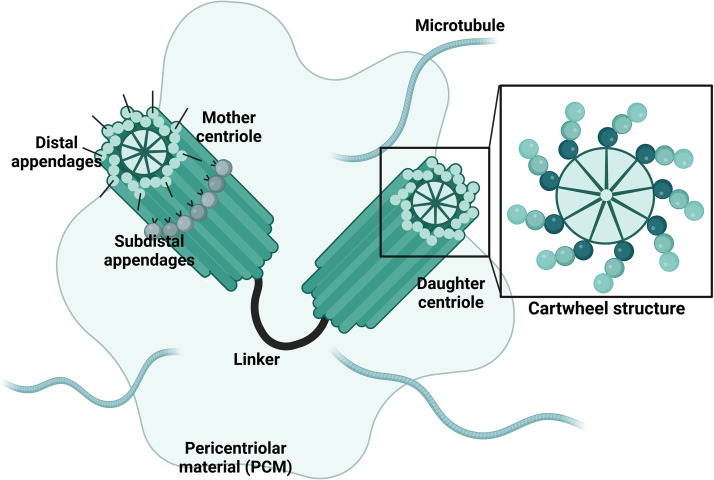

CENTROSOME DUPLICATION AND MISREGULATION

The centrosome serves as the main MTOC for the cell, and as such plays an essential role in mitotic spindle assembly, chromosome segregation during cell division, maintaining cell shape, and even acts as a scaffold for cell signaling (9). Each centrosome (Fig. 1) is composed of a pair of centrioles which consist of triplets of microtubules arranged around a central cartwheel with the conserved 9-fold symmetry (10). To form the centrosome, two centrioles are connected at their proximal ends by a protein centrosome linker and are joined such that they are perpendicular to one another (11). Of these, one centriole, termed the mother centriole, is mature, meaning it possesses a distal and subdistal appendage, whereas the daughter centriole is immature and lacks these appendages (9). The centrosome is surrounded by the pericentriolar material (PCM) which consists of over 100 proteins required for microtubule (MT) nucleation and cell cycle regulation (12).

FIG 1.

Centrosome structure. The centrosome is composed of two centrioles, a mature mother centriole and an immature daughter centriole. The mother centriole is distinct because it has distal and subdistal appendages. The centrioles are connected for part of the cell cycle by a protein linker and are surrounded by varying amounts of pericentriolar material, again dependent on the stage of replication. Each centriole consists of triplets of microtubules arranged around a central cartwheel structure with the conserved 9-fold symmetry. The centrosome is the site of microtubule nucleation.

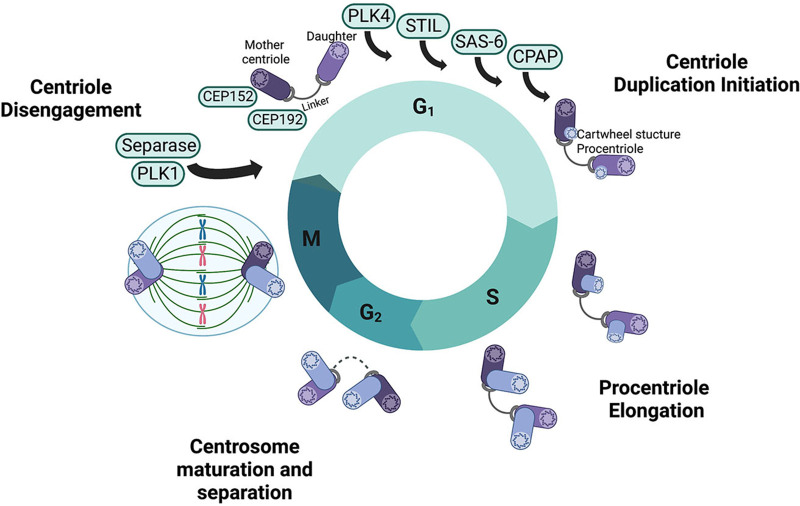

Centrosome amplification is intimately linked to cell cycle progression and is tightly controlled to ensure each centriole duplicates only once per cycle and that only one new centriole forms along its pre-existing template (10) (Fig. 2). Similar to DNA replication, centriole duplication is a tightly regulated event, requiring (i) centriole disengagement, mediated by Polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) and the protease separase (13); and (ii) centriole-to-centrosome conversion, involving removal of the cartwheel structure and acquisition of PCM by the procentriole (14). As the cell enters the G1/S transition, the 192 kDa centrosomal protein (CEP192) recruits CEP152 and PLK4 to the centriole (15). Competition between CEP152 and CEP192 restricts PLK4 to the proximal end of the centriole, thus PLK4 activity plays an essential role in regulating centriole copy number (16). Subsequently, transautophosphorylation of PLK4 allows for associations with and phosphorylation of centriolar assembly protein STIL, which is required for binding to the C-terminus of another centriolar assembly protein SAS-6 (17). As the cell enters S phase, cartwheel-MT connections are established and the procentriole begins to elongate using the cartwheel structure as a template (14). As the centriole elongates, centrosomal P4.1-associated protein (CPAP) binds to the plus end of MTs, slowing centriole growth and MT assembly (18). As the cell enters prophase, additional PCM components are recruited to enhance MT-nucleation for spindle pole formation, causing a notable increase in the diameter of the centrosome (19). Finally, the proteinaceous linker connecting the two pairs of centrioles is degraded, allowing the centrosomes to move to the cellular poles during mitosis to mediate chromosome segregation (11).

FIG 2.

Centrosome duplication and the cell cycle. Centrosome duplication is intricately linked to the cell cycle. At the start of G1, a mature mother centriole is connected to an immature daughter centriole by a linker protein. Numerous proteins are recruited to the site of duplication and initiate duplication through the formation of a procentriole structure on each the two centrioles. Procentrioles are elongated through S phase to become immature centrioles. In preparation for M phase, during G2, the previously immature daughter centriole matures and the protein linker between the new centrosomes degrades allowing one centrosome to migrate to each pole of the cell to orchestrate chromosomal segregation during mitosis.

The presence of more than two centrosomes can be catastrophic as it can result in missegration of the chromosomes between daughter cells and other devastating replication defects. While many checkpoints are in place to ensure that the centrosome is only duplicated once and that cells are limited to two centrosomes per cell, misregulation of the centrosome duplication machinery, blocks in cytokinesis, or cell-cell fusion events can lead to the presence of supernumerary centrosomes (9). Centrosome amplification beyond duplication is strongly correlated with tumorigenesis and supernumerary centrosomes are found in almost all cancer cell types (9). Extra centrosomes can pose a problem to the cell by causing mitotic errors and genomic instability (20). To avoid this, cells can inactivate centrosomes, lose extra centrosomes, or most commonly will use centrosome clustering, in which groups of centrosomes are clustered to form pseudopolar spindles for bipolar cell division (20). However, despite the mechanisms to compensate for centrosome amplification, genomic instability and aneuploidy are still quite common in cells possessing supernumerary centrosomes (9).

Several viruses, notably oncogenic viruses, induce centrosome amplification. AIDS, caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, is associated with the development of several cancers, including Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and various cancers that manifest in cervical, testicular, anal, or lung tissues (9). HIV viral protein R (Vpr) localizes to the centrosome in infected cells where it binds to DCAF1, forming a complex with CEP78 and the ubiquitin ligase EDD-DYRK2-DDB1DCAF1 to drive centriole elongation, enhance MT nucleation, and induce centrosome amplification (3). Human T cell leukemia virus type-1 (HTLV-1), the etiological agent of T cell leukemia and lymphoma, triggers centrosome fragmentation and genomic instability via HTLV-1 Tax binding host Ran and Ran-binding protein 1 at the centrosome (6). Human papillomavirus (HPV), the etiological agent of cervical cancer, uses two oncoproteins, E6 and E7, to induce centrosome amplification and genomic instability. Expression of E6 or E7 induces multiple cellular abnormalities, including abnormal centrosome numbers, multipolar mitosis, and aneuploidy (21). Expression of E7 induces entry into S-phase, degradation of the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRB), and binding to cyclin A or E/CDK2 complexes, all to promote genomic instability in the host (4, 5, 21). E7 expression also impairs normal centriole duplication via a novel mechanism termed centriole multiplication, in which a single maternal centriole gives rise to multiple daughter centrioles (22). Maternal centrioles from cells expressing E7 exhibit aberrant PLK4 expression (4), which may serve as a mechanism to induce centriole multiplication. While E6 has also been shown to contribute to centrosome amplification, its role is less defined but may involve misregulation of p53 (21). While a cell with structural and/or functional abnormalities should be committed to apoptotic mechanisms of cell death, many viruses interfere with apoptotic signaling and mitotic checkpoints, allowing for accumulation of polyploid cells leading to aneuploidy and ultimately malignancy (21).

C. TRACHOMATIS INTERACTION WITH THE CENTROSOME

C. trachomatis is an obligate intracellular pathogen that is the leading cause of infectious blindness (trachoma) and the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection (chlamydia). Over 1.7 million cases are reported annually in the United States, with the worldwide burden nearing 131 million cases per year (23). While chlamydial infections can be asymptomatic, ascending infections lead to serious complications, including pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and sterility (24). Significantly, current or prior chlamydial infection increases the risk of developing cervical or ovarian cancers (25, 26). There is no Chlamydia vaccine and due to the short-lived immunity from infection, reinfection is common (27). Additionally, treatment failure occurs in approximately 10% of cases (28–30). Understanding the physiological consequences of chlamydial infections are paramount to improving female health outcomes and preventing the devastating consequences that can result from infection.

All Chlamydia share a biphasic developmental cycle in which they alternate between an infectious, nonreplicative elementary body (EB) and a noninfectious, replicative reticulate body (RB) (31). EBs are endocytosed into a membrane-bound compartment, termed the inclusion, which avoids fusion with lysosomes and instead traffics along microtubules to the MTOC of the cell (32). Movement to the MTOC requires the minus-end-directed microtubule motor dynein; however, the dynactin complex is not necessary (32). While bacterial and viral pathogens co-opt host microtubules for intracellular migration (33, 34), C. trachomatis is distinct in that it has likely evolved a factor that supersedes the requirement for dynactin which is normally necessary for linking dynein to specific cargo. Indeed, inhibition of bacterial protein synthesis impairs chlamydial delivery to the MTOC, further suggesting that C. trachomatis possesses a factor to compensate for dynactin (32). At the MTOC, the inclusion tightly associates with the centrosome, an interaction that is maintained throughout the infection cycle (35). The association between the inclusion and the centrosome results in relocalization of the centrosome away from its normal position juxtaposed to the nucleus (35). Notably the association between the inclusion and the centrosome is so tight that if the infected cell divides, the chlamydial inclusion is appropriated to only one daughter cell following one centrosome, yet inclusion membrane components remain attached to the other centrosome that is allocated to the uninfected daughter cell (35).

As the infection progresses, supernumerary centrosomes and abnormal spindles become evident at 36 h postinfection (35, 36). These supernumerary centrosomes are bona fide centrosomes consisting of two centrioles surrounded by the PCM; however, many are immature procentrioles that lack subdistal appendages, suggesting C. trachomatis induces the uncontrolled initiation of procentriole formation (36). While supernumerary centrosomes can form when cytokinesis is blocked and indeed, C. trachomatis blocks host cell cytokinesis (37, 38), the fact that many of the centrioles are immature suggests that cytokinesis defects are not the major driver of supernumerary centrosome formation during C. trachomatis infection. Furthermore, the kinase activities of PLK4 and Cdk2 are required for the centrosomal abnormalities that manifest during C. trachomatis infection, further supporting the notion that there is some direct modulation of the duplication machinery by the bacterium (36).

In a cell that possesses two centrosomes, each centrosome serves to anchor microtubules at opposite poles of the cell, resulting in bipolar spindles, appropriate segregation of the chromosomes, and two daughter cells after cell division. However, if a cell possesses more than two centrosomes, multipolar spindles can form resulting in inappropriate DNA segregation. To overcome the detrimental effects of supernumerary centrosomes, the cell will initiate centrosome clustering, a process that requires both a mitotic delay and microtubule motor proteins. Centrosome clustering allows the cell to form two pseudopolar spindles by bundling the supernumerary centrosomes into two groups, resulting in proper segregation of chromosomes during division. When nuclear envelope breakdown is initiated during mitosis, the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein (NuMA) is released from the nucleus. NuMA targets dynactin to the minus-end of microtubules, restricting dynein motor activity to that specific spot (39). Additionally, the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) will monitor microtubule attachment to the kinetochore and delay anaphase initiation until microtubules have appropriately attached (40). During chlamydial infection, increased geometric spread of centrosomes is noted, suggesting C. trachomatis may directly interfere with the cell’s ability to cluster centrosomes together to form two active spindle poles (41, 42). While dynein is localized to the chlamydial inclusion, this does not appear to adversely affect its localization to spindles or its ability to carry out diverse functions in the cell, suggesting dynein sequestration at the inclusion membrane is not the mechanism by which C. trachomatis inhibits centrosome clustering (41). By measuring the mitotic index of infected cells, it was noted that infected cells exit metaphase prior to appropriate chromosome alignment, indicating that Chlamydia’s ability to interfere with centrosome clustering may be due to direct perturbation of the SAC (41). While securin and cyclin B1 were observed to be degraded (41, 43), this has since been shown an artifact of sample processing (44). Future work is needed to address whether C. trachomatis infection does indeed perturb the SAC and if so, how the bacteria orchestrate this. Additionally, while some studies have determined that C. trachomatis infection does not alter the rate of progression through the cell cycle (37), other studies suggest that infected cells proliferate at an altered rate (38, 43) Resolving this conundrum could provide insight as to the mechanisms for how C. trachomatis induces centrosomal and spindle abnormalities.

Collectively, C. trachomatis causes substantial cytological changes during infection including supernumerary centrosomes, multipolar spindles, and blocked cytokinesis which leads to genomic instability (41, 45). These cellular abnormalities can be found in almost all types of cancerous lesions (9), suggesting that C. trachomatis infection could drive cellular transformation events. Using a 3T3 anchorage-independence assay, which allows for assessment of mutagenic potential as measured by quantification colony formation indicative of cellular transformation, Knowlton et al. demonstrated that C. trachomatis infection induces colony formation, indicating that the bacteria can induce stable changes to the cell that can prime it for cellular transformation (46). It is well-established that females infected with Chlamydia have increased cellular replication, cervical dysplasia, and similar cellular abnormalities (centrosome mislocalization, infection induced multinucleation) to those previously noted in cell culture (46). This suggests that C. trachomatis may be sufficient to cause invasive cervical cancer. However, Chlamydia infection can be lytic (47), resulting in death of the host cell; thus, the aberrant host cell would need to survive in order to induce cervical cancer. There are, however, several possible ways this could occur. If an infected cell divides, the inclusion is appropriated into only one daughter cell, yet the centrosomal and spindle defects could be allocated to the uninfected daughter cell (35), serving as one mechanism for propagation of cellular abnormalities. While lytic exit is one method used for bacterial release at the end of the developmental cycle, the inclusion can also “extrude,” leaving the host cell intact (47). Importantly, treatment with antibiotics has been shown to resolve the infection, yet abnormal centrosome numbers and multipolar spindles persist (41, 46). While secreted effectors are typically thought of as only acting in the infected cell, the T3SS effector protein SINC from Chlamydia psittaci has been shown to target the nuclear envelope of infected and uninfected neighboring cells (48). Thus, if secreted proteins can access bystander cells, they could induce cytopathic changes in the absence of infection; however, this concept requires further exploration.

C. trachomatis has been implicated as a risk factor for cervical cancer. However, HPV is typically considered the major etiological agent of cervical cancer, with 70% of cervical cancers being attributed to high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 (49). While many females are infected with high-risk HPV types, less than 2% will develop cervical cancer (49), suggesting other factors might contribute to oncogenesis. Cofactors, including immune status, hormones, smoking, and co-infection with C. trachomatis have been proposed (25, 26, 50, 51). Indeed, epidemiological data show that females with a prior chlamydial infection are at elevated risk of developing cervical cancer (52, 53). Current cell culture models make it difficult to study the link between C. trachomatis, HPV, and oncogenesis. A newly developed ectocervical organoid model containing stem and differentiated cells to mimic the stratified squamous epithelium of the cervix will enable researchers to overcome this barrier (54). This study showed that HPV and C. trachomatis induce different transcriptional and posttranslational changes, some that antagonize the other. This emphasizes the need to study these organisms in more relevant model systems to better understand the interactions between these two pathogens and how together they can increase cellular and genomic instability that promote neoplastic progression. Both HPV and C. trachomatis have been shown to independently induce centrosome amplification, and new studies using a co-infection model revealed that the two pathogens have an additive effect on centrosome amplification (38). Uniquely, C. trachomatis infection correlates with multinucleation that results from a defect in cytokinesis (38). These new studies, in conjunction with prior work, suggests that supernumerary centrosome formation during Chlamydia infection may result from perturbation of the centrosome duplication machinery, as well as from cytokinesis failure (38, 45).

ROLE OF C. TRACHOMATIS SECRETED FACTORS IN MANIPULATION OF THE CENTROSOME

To establish its unique intracellular niche, Chlamydia releases an arsenal of virulence factors into the host cell using a type III secretion system (T3SS) (55). A subset of these proteins, termed conventional T3SS (cT3SS) effector proteins, have been shown to localize to the plasma membrane, Golgi apparatus, and nucleus where they play important roles in host cell invasion and subversion of host defense mechanisms (56–59). Additionally, C. trachomatis secretes a unique class of proteins, termed inclusion membrane proteins (Incs), that intercalate into the inclusion membrane (60, 61). Inc proteins possess two or more transmembrane domains that allow for their insertion in the inclusion membrane in such a way that their N- and C-terminal domains are oriented into the host cell cytosol (62). Given their positioning at the host-pathogen interface, Inc proteins are poised to mediate crucial interactions with the host cell, including binding to small GTPases, generating contact sites with host organelles, and mediating inclusion fusion (63–67). While cT3SS and Inc proteins likely play important roles in formation of the C. trachomatis unique intracellular niche, the genetic intractability of Chlamydia spp. has hindered our ability to dissect their roles in manipulation of host cell biology. However, recent advances in chlamydial genetics, including the ability to overexpress epitope-tagged proteins in C. trachomatis (68–70) and generate site-specific mutants (71, 72), in conjunction with protein-protein interaction studies (64) have identified several secreted effectors and Inc proteins that bind to centrosome components or factors involved in cell cycle progression (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

C. trachomatis Inc proteins and secreted effectors that target the centrosome

| Gene | Classification | Host target | Function/phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT105/CteG | cT3SSe | CETN2 | Centrosome amplification, lytic exit | 89, 90, 92 |

| CT192/Dre1 | Inc protein | Dynactin | Repositions centrosome around inclusion | 39, 64 |

| CT223/IPAM | Inc protein | CEP170 | Centrosome amplification, multinucleation, MT reorganization | 70, 71 |

| CT288 | Inc protein | CCDC146 | Unknown | 80, 81 |

| CT847 | cT3SSe | GCIP | Unknown | 93 |

| CT850 | Inc protein | DYNLT1 | Unknown | 76, 78 |

| CPAF | Secreted effector | Unknown | Centrosome amplification, multinucleation | 42 |

Early observations that Chlamydia spp. interfered with the cell cycle, leading to centrosome amplification and cytokinesis defects, rapidly prompted searches for the bacterial factors responsible for these phenotypes. As Inc proteins reside at the host-pathogen interface, these proteins were considered likely candidates for mediating interactions with the centrosome. Indeed, ectopic expression of known Inc proteins identified CT223 as a candidate for inducing centrosome amplification and blocking cytokinesis (73). Bioinformatic analysis of the C-terminal domain of CT223 revealed it shares primary sequence similarity to the MT and centrosome-interacting protein pericentrin, resulting in its designation as inclusion protein acting on microtubules (IPAM) (74). IPAM was shown to bind to centrosomal protein of 170 kDa (CEP170), a centrosome protein that localizes to subdistal appendages of the mature mother centriole where it is phosphorylated by PLK1 to promote microtubule organization and spindle assembly (75, 76). In line with CEP170’s ascribed function, recruitment of CEP170 to the inclusion by IPAM results in disruption of the PCM and induces MT reorganization, presumably to form the MT scaffold that encompasses the chlamydial inclusion (74). As the mitotic spindle has been shown to dictate the position of the cleavage furrow during cytokinesis (77), MT reorganization induced by CEP170-IPAM interactions could explain the cytokinesis defect and centrosome amplification phenotype that manifest when IPAM is ectopically expressed. At the time of these studies, genetic tools for manipulation of C. trachomatis were in their infancy and the ability to overexpress or insertionally inactivate IPAM was not feasible; thus, prior studies were predominately conducted using ectopic expression. However, a newly generated IPAM mutant (78) will now make it possible to query the importance of IPAM-mediated perturbation of MTs and host cytokinesis directly during C. trachomatis infection.

The inclusion membrane includes unique structures, termed inclusion microdomains, which are areas of the inclusion enriched in cholesterol, active Src family kinases, and several inclusion membrane proteins (79, 80). Notably, microdomains share a number of traits with the lipid rafts found in the plasma membranes of eukaryotic cells and they are hypothesized to play a similar role in nucleating membrane protein components of macromolecular signaling and interaction platforms on the surface of the inclusion. Microdomains also serve as contact points with the centrosome (79), an interaction that is likely mediated by interactions with select Inc proteins. Of the microdomain Incs, ectopically expressed CT850 was uniquely shown to colocalize with centrosomes (79). Further study of CT850 revealed it possesses a Dynein Light Chain Tctex-Type 1 (DYNLT1) binding domain and this domain is necessary for CT850-dynein interactions (81). Given the importance of dynein for inclusion trafficking to the MTOC and the fact that CT850 is expressed early during infection (82), it is conceivable that CT850 plays an important role in inclusion positioning at the MTOC through these interactions. Furthermore, it is intriguing to postulate that CT850 may functionally supplant the dynactin complex which surprisingly is not required for inclusion trafficking.

Site-directed mutagenesis of Inc proteins using the group II intron revealed that the microdomain Inc protein CT288 was important for intracellular growth and in vivo infection (80, 83). Using a yeast-2-hybrid, Almeida et al. (84) demonstrated that CT288 binds to the coiled-coil domain-containing protein 146 (CCDC146), a protein of unknown function that localizes to the mother centriole (85). This interaction was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation from infected and transfected cells. While CCDC146 was reported to localize to the inclusion membrane, its recruitment was independent of CT288 and, furthermore, did not affect centrosome localization to the inclusion membrane (84). Given that several other Inc proteins bind to centrosome components, it is not surprising that the loss of a single Inc protein does not impair recruitment of this host organelle to the chlamydial inclusion. Future work is needed to address whether the interaction between CT288 and CCDC146 is physiologically important for some reason other than centrosome localization, such as regulating the as of yet unknown function of CCDC146.

From an affinity-purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) screen aimed at identifying putative host targets of Inc proteins, a high-confidence interaction between ectopically expressed CT192 and all 11 subunits of the dynactin complex was noted (64), a finding that was recently confirmed in the context of infection (42). CT192 was shown to be necessary for dynactin recruitment to the inclusion membrane, resulting in its redesignation as dynactin recruiting effector 1 (Dre1). While dynactin is dispensable for initial inclusion trafficking to the MTOC (32), dynactin localizes to many compartments and organelles, including the centrosome, where it organizes MTs and facilitates organelle positioning, suggesting it might be important for C. trachomatis manipulation of the centrosome. In line with the important role dynactin plays in centrosome dynamics, Dre1-dynactin interactions were shown to be important for relocalization of the centrosomes from their juxta-nuclear position to the inclusion membrane (42). Additionally, while Dre1-dynactin interactions do not contribute to the supernumerary centrosome phenotype, Dre1 is important for blocking centrosome clustering and is partially responsible for infection-induced multinucleation (42). Dre1’s role in blocking centrosome clustering is likely through the actions of dynactin on MT-binding and organizing of organelles with stable pools of dynactin to override canonical centrosome positioning pathways. Abnormal centrosome positioning can lead to abnormal spindles, which in turn can impede cytokinesis and cause multinucleation, providing an explanation for how Dre1 also contributes to the multinucleation phenotype. Other C. trachomatis secreted factors have been implicated in contributing to infection-induced multinucleation (45); thus, it is not surprising that loss of Dre1 only partially reduces this phenotype.

The chlamydial protease- or proteasome-like activity factor (CPAF) is a cysteine protease that is presumed to be a major virulence factor of Chlamydia (86). Since its discovery in 2001, numerous bacterial and host factors have been identified that were presumed to be cleaved or degraded by CPAF (87), including cyclin B1 and securin, two proteins involved in regulating progression through the cell cycle (41). However, more recent studies have demonstrated that many of these targets were artificially cleaved during sample processing and are not processed under natural biological conditions, as made evident by the use of a CPAF inhibitor (88). With the isolation of a C. trachomatis CPAF null strain, generated by chemical mutagenesis, CPAF has been shown to be required for inducing centrosome amplification and multinucleation (45). While CPAF clearly plays a role in inducing centrosome overamplification and progression through the cell cycle, relevant host targets have yet to be identified, making it challenging to determine how CPAF induces these abnormalities. How CPAF, which is a type II secretion system (T2SS) effector, crosses the inclusion membrane—moving from the inclusion lumen to the host cell cytosol—is unknown and requires further exploration.

While several Inc proteins and the T2SS effector protein CPAF clearly play some role in co-opting the centrosome, cT3SS effector proteins, which are not restricted to the host-pathogen interface, could also be involved. Numerous chlamydial proteins have been shown to be secreted using a surrogate host (89–91), and a growing list have been confirmed as secreted during chlamydial infection, including CT105 (92). During infection, CT105 was shown to localize to the Golgi early in infection (16 h to 20 h) and to the plasma membrane late in infection (30 h to 40 h) resulting in its designation as C. trachomatis effector associated with the Golgi (CteG) (92). While the precise localization and function of CteG at these sites remains unknown, it did induce a vacuolar protein sorting defect in yeast, suggesting it might perturb host vesicular trafficking (92). Using a yeast suppressor screen to identify the host pathway(s) targeted by CteG, the anaphase promoting complex subunit 2 (APC2) was identified as a suppressor of CteG toxicity in yeast, suggesting it might interfere with the cell cycle, which is closely linked to centrosome duplication (93). Using AP-MS, CteG was shown to bind to centrin-2 (CETN2), a key regulator of centriole duplication and spindle formation (94). In line with previous reports demonstrating that CETN2 is important for centriole duplication (94), the absence of CETN2 or CteG significantly impaired Chlamydia’s ability to induce centrosome amplification (93). Given the role of CETN2 in centriole duplication, it is interesting to speculate that CteG could be subverting this process to dysregulate the duplication machinery to cause formation of supernumerary centrosomes. Thus far, CteG and CPAF are the only chlamydial effectors shown to directly contribute to supernumerary centrosome formation during C. trachomatis infection; however, whether these effectors operate through the same or distinct pathways is unknown. CteG appears to be proteolytically processed in infected cells (92, 93) and CPAF has been implicated in cleaving chlamydial proteins (87). It is intriguing to speculate that CteG could be cleaved by CPAF, which is necessary for its function and ability to induce centrosome amplification. If this is the case, it could help address how both effector proteins contribute to centrosome amplification during infection. Additionally, CteG was recently shown to be important for lytic exit at the conclusion of the developmental cycle (95). How this relates to its newly ascribed role in modulating centrosome amplification or whether CteG is a multifunctional effector is unknown and warrants further study.

From a yeast-2-hybrid screen to identify putative interacting partners of the cT3SS effector protein CT847, an interaction with the Grap2 cyclin-D interacting protein (GCIP) was detected and confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation (96). GCIP binds to both cyclin D and Grap2 where it plays a critical role in cell proliferation and differentiation (97). At the mid-cycle of infection, GCIP was noted to be degraded in a manner that requires active bacterial protein synthesis and a functional proteasome (96). Due to the genetic intractability of C. trachomatis at the time, neither the requirement of CT847 for GCIP degradation nor how CT847-GCIP interactions impact the host cell cycle were able to be confirmed. As GCIP interacts with cyclin D1, degradation of GCIP may enable infected cells to progress from G1 to S, which is the point at which centrosome duplication begins. Indeed, siRNA knockdown of GCIP enhanced chlamydial replication (96); however, further work is needed to determine whether GCIP depletion during chlamydial infection impacts the host cell cycle. Potential quicker advancement to S phase may allow Chlamydia to initiate centrosome amplification. Intriguingly, CT847 shares 37% sequence similarity to the low-temperature essential gene (Lte1) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (96). In the event the spindles become misaligned in anaphase, the cells will arrest due to activation of the mitotic exit network (MEN), which is mediated by Lte1 (98). As C. trachomatis infection induces spindle abnormalities, it is intriguing to speculate that CT847 might mimic Lte1 to modulate MEN for cell proliferation to occur in the face of these cellular abnormalities.

CONCLUSIONS

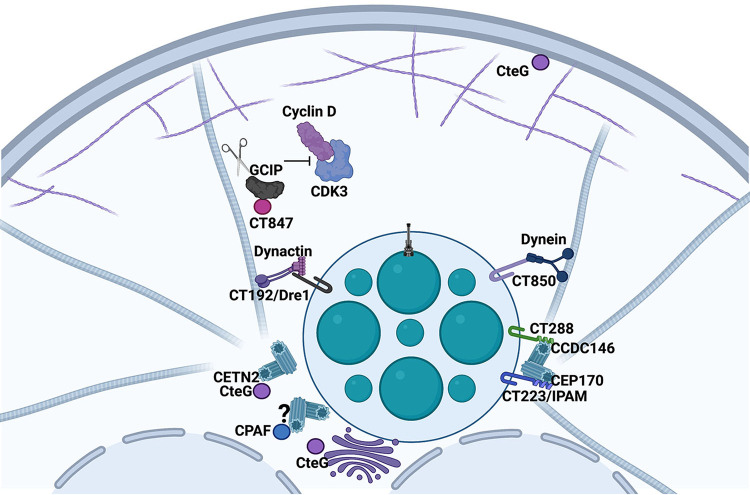

Taken together, these studies support a model (Fig. 3) in which early during infection the nascent chlamydial inclusion moves along microtubes, potentially using CT850-dynein interactions to localize at the MTOC. Once the growing inclusion arrives in the vicinity of the MTOC, host centrosomes are recruited away from their juxta-nuclear region via Dre1-dynactin interactions where they associate with inclusion microdomains through interactions with Inc proteins such as CT288 and IPAM that bind CCDC146 and CEP170, respectively. During the mid-cycle of infection CT847 interacts with GCIP, resulting in GCIP degradation to potentially promote cell progression from G1 to S. To support the growing inclusion, MT reorganization is mediated by IPAM-CEP170 interactions. As the infection progresses, supernumerary centrosome formation is induced by CteG and CPAF. Dre1 and microdomain Incs are also important for repositioning and anchoring these newly formed centrosomes. While these studies highlight the great lengths numerous C. trachomatis effector proteins must go through to co-opt the centrosome, many unanswered questions remain. For instance, we still do not understand why the inclusion associates with the centrosome and why promotion of supernumerary centrosomes seems to be an essential event for proper chlamydial proliferation. One thought is that because the chlamydial inclusion is partitioned into only one of the daughter cells, this association might ensure appropriate partitioning during cytokinesis. It is also conceivable that inducing centrosome amplification would alter the rate of cellular proliferation, allowing for more resources to be diverted to the bacteria. Another possibility is that amplifying centrosomes to decorate the periphery of the inclusion would allow for a more robust MT network around the growing inclusion to provide support and anchoring. Elucidating the how and why Chlamydia induces these host cellular abnormalities is of great importance as it could provide answers to questions such as how C. trachomatis infection increases the risk for cancer. Because C. trachomatis is linked to an increased risk of cervical cancer, future studies linking some of these effector proteins to this increased risk through transformation of host cells are warranted. This is particularly interesting in the context of co-infection with HPV to address whether C. trachomatis is a co-factor helping drive oncogenesis in HPV infected cells. One could postulate that the workings of the many effector proteins described in this review that cause lasting host cellular transformations could contribute to oncogenesis of host cells in infected tissues.

FIG 3.

Role of C. trachomatis secreted factors in manipulation of the centrosome. After the bacterium is internalized into a host cell, it survives in a membrane compartment that is extensively modified by incorporation of inclusion membrane proteins. Interactions between dynein and the Inc protein CT850 are believed to promote inclusion trafficking to the MTOC. Other Inc proteins, including CT288 and IPAM, bind to centrosomal components CCDC146 and CEP170, respectively. Dre1, through interactions with dynactin, relocalizes the centrosomes to the inclusion. The secreted factor CteG binds CETN2 to induce centrosome amplification. While CPAF also induces centrosome amplification, the host cell target is unknown. CT847 binds to and promotes degradation of GCIP potentially altering host cell cycle progression.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alix McCullough for critical review of this manuscript. We acknowledge grant support from the NIH (R01 AI150812 and R01 AI155434 to M.M.W.) and the University of Iowa Stead Family Scholars. B.S. was supported by T32 AI007511.

Biographies

Brianna Steiert received her B.A. in molecular biology from William Jewell College in 2018. At Jewell, she researched cell division mechanisms of Planctomyces limnophilus in the laboratory of Lilah Rahn-Lee. After undergraduate, she worked for a year at the University of Kansas Medical Center as a Research Assistant in the lab of Bruno Hagenbuch studying hepatocyte-specific organic anion transporting polypeptides involved in drug uptake. After this stint in pharmacology, she returned to microbiology as a graduate student at the University of Iowa in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in 2019. Brianna is currently a PhD candidate in the lab of Mary M. Weber studying Chlamydia trachomatis type III secreted effector proteins. Her focus is on the conventional effector CteG and its role in centrosome amplification. Brianna is interested in obligate intracellular pathogens and how they use secreted effectors to subvert host pathways.

Robert Faris pursued his PhD at the University of Texas at Austin, where he studied the role of mitochondria and lipid metabolism in the aging immune system and cancer. A deep desire to live in the Rocky Mountains brought him to the National Institutes of Health, Rocky Mountain Labs for a postdoctoral position in the laboratory of persistent viral diseases. Robert expanded his investigations on mitochondrial mechanisms of pathogenesis in the laboratory of Suzette Priola where he focused on mitochondrial dysregulation during neurodegenerative disease. In 2017, he moved to the University of Iowa where he is now a Staff Scientist and an adjunct lecturer in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology.

Mary M. Weber received her B.S. in biology from the University of Akron in 2004. After working in the biotechnology sector for a year, she pursued her M.S. in biology at Texas State University where she worked in the laboratory of Robert McLean, investigating the importance of mixed species interactions in biofilms. At a conference in Texas, she learned about obligate intracellular pathogens and decided to pursue her Ph.D. at Texas A&M in the laboratory of James Samuel where she worked to identify and characterize type IV secreted effector proteins from Coxiella burnetii Her interest in host-pathogen interactions prompted her to undertake a postdoctoral position with Ted Hackstadt, where she investigated the role of Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane proteins in promoting bacterial replication and inclusion development. In 2017, she started her own lab at the University of Iowa where she continues to study how obligate intracellular bacteria subvert normal host cell processes to carve out their unique replicative niches. She is fascinated by how these proteins use molecular mimicry to thwart host defense mechanisms.

Contributor Information

Mary M. Weber, Email: mary-weber@uiowa.edu.

Anthony R. Richardson, University of Pittsburgh

REFERENCES

- 1.Vermeulen K, Bockstaele DRV, Berneman ZN. 2003. The cell cycle: a review of regulation, deregulation and therapeutic targets in cancer. Cell Prolif 3:131–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin M, Xie SS, Chan KY. 2022. An updated view on the centrosome as a cell cycle regulator. Cell Div 17:1. 10.1186/s13008-022-00077-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hossain D, Barbosa JAF, Cohen ÉA, Tsang WY. 2018. HIV-1 Vpr hijacks EDD-DYRK2-DDB1DCAF1 to disrupt centrosome homeostasis. J Biol Chem 293:9448–9460. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.001444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korzeniewski N, Treat B, Duensing S. 2011. The HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein induces centriole multiplication through deregulation of Polo-like kinase 4 expression. Mol Cancer 10:61. 10.1186/1476-4598-10-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen CL, Münger K. 2008. Direct association of the HPV16 E7 oncoprotein with cyclin A/CDK2 and cyclin E/CDK2 complexes. Virology 380:21–25. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peloponese J-M, Haller K, Miyazato A, Jeang K-T. 2005. Abnormal centrosome amplification in cells through the targeting of Ran-binding protein-1 by the human T cell leukemia virus type-1 Tax oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:18974–18979. 10.1073/pnas.0506659103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cumming BM, Rahman M, Lamprecht DA, Rohde KH, Saini V, Adamson JH, Russell DG, Steyn AJC. 2017. Mycobacterium tuberculosis arrests host cycle at the G1/S transition to establish long term infection. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006389. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sol A, Lipo E, de Jesús-Díaz DA, Murphy C, Devereux M, Isberg RR. 2019. Legionella pneumophila translocated translation inhibitors are required for bacterial-induced host cell cycle arrest. Proc National Acad Sci 116:3221–3228. 10.1073/pnas.1820093116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao JZ, Ye Q, Wang L, Lee SC. 2021. Centrosome amplification in cancer and cancer-associated human diseases. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta Bba - Rev Cancer 1876:188566. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2021.188566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nigg EA, Holland AJ. 2018. Once and only once: mechanisms of centriole duplication and their deregulation in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 19:297–312. 10.1038/nrm.2017.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Panic M, Hata S, Neuner A, Schiebel E. 2015. The centrosomal linker and microtubules provide dual levels of spatial coordination of centrosomes. PLoS Genet 11:e1005243. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodruff JB, Wueseke O, Hyman AA. 2014. Pericentriolar material structure and dynamics. Philosophical Transactions Royal Soc B Biological Sci 369:20130459. 10.1098/rstb.2013.0459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsou M-FB, Wang W-J, George KA, Uryu K, Stearns T, Jallepalli PV. 2009. Polo kinase and separase regulate the mitotic licensing of centriole duplication in human cells. Dev Cell 17:344–354. 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanco-Ameijeiras J, Lozano-Fernández P, Martí E. 2022. Centrosome maturation – in tune with the cell cycle. J Cell Sci 135. 10.1242/jcs.259395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonnen KF, Gabryjonczyk A-M, Anselm E, Stierhof Y-D, Nigg EA. 2013. Human Cep192 and Cep152 cooperate in Plk4 recruitment and centriole duplication. J Cell Sci 126:3223–3233. 10.1242/jcs.129502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park S-Y, Park J-E, Kim T-S, Kim JH, Kwak M-J, Ku B, Tian L, Murugan RN, Ahn M, Komiya S, Hojo H, Kim N-H, Kim BY, Bang JK, Erikson RL, Lee KW, Kim SJ, Oh B-H, Yang W, Lee KS. 2014. Molecular basis for unidirectional scaffold switching of human Plk4 in centriole biogenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21:696–703. 10.1038/nsmb.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moyer TC, Clutario KM, Lambrus BG, Daggubati V, Holland AJ. 2015. Binding of STIL to Plk4 activates kinase activity to promote centriole assembly. J Cell Biol 209:863–878. 10.1083/jcb.201502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma A, Aher A, Dynes NJ, Frey D, Katrukha EA, Jaussi R, Grigoriev I, Croisier M, Kammerer RA, Akhmanova A, Gönczy P, Steinmetz MO. 2016. Centriolar CPAP/SAS-4 imparts slow processive microtubule growth. Dev Cell 37:362–376. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodruff JB, Gomes BF, Widlund PO, Mahamid J, Honigmann A, Hyman AA. 2017. The centrosome is a selective condensate that nucleates microtubules by concentrating tubulin. Cell 169:1066–1077.e10. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quintyne NJ, Reing JE, Hoffelder DR, Gollin SM, Saunders WS. 2005. Spindle multipolarity is prevented by centrosomal clustering. Science 307:127–129. 10.1126/science.1104905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moody CA, Laimins LA. 2010. Human papillomavirus oncoproteins: pathways to transformation. Nat Rev Cancer 10:550–560. 10.1038/nrc2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duensing A, Liu Y, Perdreau SA, Kleylein-Sohn J, Nigg EA, Duensing S. 2007. Centriole overduplication through the concurrent formation of multiple daughter centrioles at single maternal templates. Oncogene 26:6280–6288. 10.1038/sj.onc.1210456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman L, Rowley J, Hoorn SV, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, Stevens G, Gottlieb S, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. 2015. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One 10:e0143304. 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darville T, Hiltke TJ. 2010. Pathogenesis of genital tract disease due to chlamydia trachomatis. J Infect Dis 201:S114–S125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Das M. 2018. Chlamydia infection and ovarian cancer risk. Lancet Oncol 19:e338. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30421-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu H, Shen Z, Luo H, Zhang W, Zhu X. 2016. Chlamydia trachomatis infection-associated risk of cervical cancer. Medicine (Baltimore, MD) 95:e3077. 10.1097/MD.0000000000003077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de la Maza LM, Darville TL, Pal S. 2021. Chlamydia trachomatis vaccines for genital infections: where are we and how far is there to go? Expert Rev Vaccines 20:421–435. 10.1080/14760584.2021.1899817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Afrakhteh M, Mahdavi A, Beyhaghi H, Moradi A, Gity S, Zafargandi S, Zonoubi Z. 2011. The prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis in patients who remained symptomatic after completion of sexually transmitted infection treatment. Iran J Reprod Med 11:285–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadzadeh F, Dolatian M, Jorjani M, Afrakhteh M, Majd HA, Abdi F, Pakzad R. 2019. Urogenital chlamydia trachomatis treatment failure with azithromycin: a meta-analysis. Int J Reproductive Biomed 17:603–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geisler WM, Uniyal A, Lee JY, Lensing SY, Johnson S, Perry RCW, Kadrnka CM, Kerndt PR. 2015. Azithromycin versus doxycycline for urogenital chlamydia trachomatis infection. N Engl J Med 373:2512–2521. 10.1056/NEJMoa1502599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J. 2016. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 14:385–400. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grieshaber SS, Grieshaber NA, Hackstadt T. 2003. Chlamydia trachomatis uses host cell dynein to traffic to the microtubule-organizing center in a p50 dynamitin-independent process. J Cell Sci 116:3793–3802. 10.1242/jcs.00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leopold PL, Pfister KK. 2006. Viral strategies for intracellular trafficking: motors and microtubules. Traffic 7:516–523. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim S-W, Ihn K-S, Han S-H, Seong S-Y, Kim I-S, Choi M-S. 2001. Microtubule- and dynein-mediated movement of Orientia tsutsugamushi to the microtubule organizing center. Infect Immun 69:494–500. 10.1128/IAI.69.1.494-500.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grieshaber SS, Grieshaber NA, Miller N, Hackstadt T. 2006. Chlamydia trachomatis causes centrosomal defects resulting in chromosomal segregation abnormalities. Traffic 7:940–949. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson KA, Tan M, Sütterlin C. 2009. Centrosome abnormalities during a Chlamydia trachomatis infection are caused by dysregulation of the normal duplication pathway. Cell Microbiol 11:1064–1073. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Greene W, Zhong G. 2003. Inhibition of host cell cytokinesis by Chlamydia trachomatis infection. J Infect 47:45–51. 10.1016/s0163-4453(03)00039-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang K, Muñoz KJ, Tan M, Sütterlin C. 2021. Chlamydia and HPV induce centrosome amplification in the host cell through additive mechanisms. Cell Microbiol 23:e13397. 10.1111/cmi.13397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hueschen CL, Kenny SJ, Xu K, Dumont S. 2017. NuMA recruits dynein activity to microtubule minus-ends at mitosis. Elife 6:e29328. 10.7554/eLife.29328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Musacchio A, Salmon ED. 2007. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 8:379–393. 10.1038/nrm2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knowlton AE, Brown HM, Richards TS, Andreolas LA, Patel RK, Grieshaber SS. 2011. Chlamydia trachomatis infection causes mitotic spindle pole defects independently from its effects on centrosome amplification. Traffic 12:854–866. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sherry J, Dolat L, McMahon E, Swaney DL, Bastidas RJ, Johnson JR, Valdivia RH, Krogan NJ, Elwell CA, Engel JN. 2022. Chlamydia trachomatis effector Dre1 interacts with dynactin to reposition host organelles during infection. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.04.15.488217. [DOI]

- 43.Balsara ZR, Misaghi S, Lafave JN, Starnbach MN. 2006. Chlamydia trachomatis infection induces cleavage of the mitotic cyclin B1. Infect Immun 74:5602–5608. 10.1128/IAI.00266-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grieshaber SS, Grieshaber NA. 2014. The role of the chlamydial effector CPAF in the induction of genomic instability. Pathog Dis 72:5–6. 10.1111/2049-632X.12207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown HM, Knowlton AE, Snavely E, Nguyen BD, Richards TS, Grieshaber SS. 2014. Multinucleation during C. trachomatis infections is caused by the contribution of two effector pathways. PLoS One 9:e100763. 10.1371/journal.pone.0100763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knowlton AE, Fowler LJ, Patel RK, Wallet SM, Grieshaber SS. 2013. Chlamydia induces anchorage independence in 3T3 cells and detrimental cytological defects in an infection model. PLoS One 8:e54022. 10.1371/journal.pone.0054022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hybiske K, Stephens RS. 2007. Mechanisms of host cell exit by the intracellular bacterium Chlamydia. Proc National Acad Sci 104:11430–11435. 10.1073/pnas.0703218104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mojica SA, Hovis KM, Frieman MB, Tran B, Hsia R, Ravel J, Jenkins-Houk C, Wilson KL, Bavoil PM. 2015. SINC, a type III secreted protein of Chlamydia psittaci, targets the inner nuclear membrane of infected cells and uninfected neighbors. Mol Biol Cell 26:1918–1934. 10.1091/mbc.E14-11-1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, Markowitz LE. 2007. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 297:813–819. 10.1001/jama.297.8.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koskela P, Anttila T, Bjørge T, Brunsvig A, Dillner J, Hakama M, Hakulinen T, Jellum E, Lehtinen M, Lenner P, Luostarinen T, Pukkala E, Saikku P, Thoresen S, Youngman L, Paavonen J. 2000. Chlamydia trachomatis infection as a risk factor for invasive cervical cancer. Int J Cancer 85:35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brake T, Lambert PF. 2005. Estrogen contributes to the onset, persistence, and malignant progression of cervical cancer in a human papillomavirus-transgenic mouse model. Proc National Acad Sci 102:2490–2495. 10.1073/pnas.0409883102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith JS, Muñoz N, Herrero R, Eluf-Neto J, Ngelangel C, Franceschi S, Bosch FX, Walboomers JMM, Peeling RW. 2002. Evidence for Chlamydia trachomatis as a human papillomavirus cofactor in the etiology of invasive cervical cancer in Brazil and the Philippines. J Infect Dis 185:324–331. 10.1086/338569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Silva J, Cerqueira F, Medeiros R. 2014. Chlamydia trachomatis infection: implications for HPV status and cervical cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289:715–723. 10.1007/s00404-013-3122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koster S, Gurumurthy RK, Kumar N, Prakash PG, Dhanraj J, Bayer S, Berger H, Kurian SM, Drabkina M, Mollenkopf H-J, Goosmann C, Brinkmann V, Nagel Z, Mangler M, Meyer TF, Chumduri C. 2022. Modelling Chlamydia and HPV co-infection in patient-derived ectocervix organoids reveals distinct cellular reprogramming. Nat Commun 13:1030. 10.1038/s41467-022-28569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Andersen SE, Bulman LM, Steiert B, Faris R, Weber MM. 2021. Got mutants? How advances in chlamydial genetics have furthered the study of effector proteins. Pathog Dis 79:ftaa078. 10.1093/femspd/ftaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pennini ME, Perrinet S, Dautry-Varsat A, Subtil A. 2010. Histone methylation by NUE, a novel nuclear effector of the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS Pathog 6:e1000995. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Faris R, McCullough A, Andersen SE, Moninger TO, Weber MM. 2020. The Chlamydia trachomatis secreted effector TmeA hijacks the N-WASP-ARP2/3 actin remodeling axis to facilitate cellular invasion. PLoS Pathog 16:e1008878. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Keb G, Ferrell J, Scanlon KR, Jewett TJ, Fields KA. 2021. Chlamydia trachomatis TmeA Directly Activates N-WASP To Promote Actin Polymerization and Functions Synergistically with TarP during Invasion. mBio 12:e02861-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen Y-S, Bastidas RJ, Saka HA, Carpenter VK, Richards KL, Plano GV, Valdivia RH. 2014. The Chlamydia trachomatis type III secretion chaperone Slc1 engages multiple early effectors, including TepP, a tyrosine-phosphorylated protein required for the recruitment of CrkI-II to nascent inclusions and innate immune signaling. PLoS Pathog 10:e1003954. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rockey DD, Grosenbach D, Hruby DE, Peacock MG, Heinzen RA, Hackstadt T. 1997. Chlamydia psittaci IncA is phosphorylated by the host cell and is exposed on the cytoplasmic face of the developing inclusion. Mol Microbiol 24:217–228. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3371700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scidmore-Carlson MA, Shaw EI, Dooley CA, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T. 1999. Identification and characterization of a Chlamydia trachomatis early operon encoding four novel inclusion membrane proteins. Mol Microbiol 33:753–765. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bannantine JP, Griffiths RS, Viratyosin W, Brown WJ, Rockey DD. 2000. A secondary structure motif predictive of protein localization to the chlamydial inclusion membrane. Cell Microbiol 2:35–47. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kokes M, Dunn JD, Granek JA, Nguyen BD, Barker JR, Valdivia RH, Bastidas RJ. 2015. Integrating chemical mutagenesis and whole-genome sequencing as a platform for forward and reverse genetic analysis of chlamydia. Cell Host Microbe 17:716–725. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mirrashidi KM, Elwell CA, Verschueren E, Johnson JR, Frando A, Von Dollen J, Rosenberg O, Gulbahce N, Jang G, Johnson T, Jäger S, Gopalakrishnan AM, Sherry J, Dunn JD, Olive A, Penn B, Shales M, Cox JS, Starnbach MN, Derre I, Valdivia R, Krogan NJ, Engel J. 2015. Global mapping of the Inc-human interactome reveals that retromer restricts chlamydia infection. Cell Host Microbe 18:109–121. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wesolowski J, Weber MM, Nawrotek A, Dooley CA, Calderon M, St Croix CM, Hackstadt T, Cherfils J, Paumet F. 2017. Chlamydia hijacks ARF GTPases To coordinate microtubule posttranslational modifications and golgi complex positioning. mBio 8:e02280-16. 10.1128/mBio.02280-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Faris R, Merling M, Andersen SE, Dooley CA, Hackstadt T, Weber MM. 2019. Chlamydia trachomatis CT229 subverts Rab GTPase-dependent CCV trafficking pathways to promote chlamydial infection. Cell Rep 26:3380–3390.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stanhope R, Flora E, Bayne C, Derré I. 2017. IncV, a FFAT motif-containing Chlamydia protein, tethers the endoplasmic reticulum to the pathogen-containing vacuole. Proc National Acad Sci 114:12039–12044. 10.1073/pnas.1709060114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang Y, Kahane S, Cutcliffe LT, Skilton RJ, Lambden PR, Clarke IN. 2011. Development of a transformation system for Chlamydia trachomatis: restoration of glycogen biosynthesis by acquisition of a plasmid shuttle vector. PLoS Pathog 7:e1002258. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bauler LD, Hackstadt T. 2014. Expression and targeting of secreted proteins from Chlamydia trachomatis. J Bacteriol 196:1325–1334. 10.1128/JB.01290-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agaisse H, Derré I. 2013. A C. trachomatis cloning vector and the generation of C. trachomatis strains expressing fluorescent proteins under the control of a C. trachomatis promoter. PLoS One 8:e57090. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson CM, Fisher DJ. 2013. Site-Specific, insertional inactivation of incA in Chlamydia trachomatis using a group II intron. PLoS One 8:e83989. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mueller KE, Wolf K, Fields KA. 2016. Gene deletion by fluorescence-reported allelic exchange mutagenesis in Chlamydia trachomatis. mBio 7:e01817-15–e01815. 10.1128/mBio.01817-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Alzhanov DT, Weeks SK, Burnett JR, Rockey DD. 2009. Cytokinesis is blocked in mammalian cells transfected with Chlamydia trachomatis gene CT223. BMC Microbiol 9:2. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dumoux M, Menny A, Delacour D, Hayward RD. 2015. A chlamydia effector recruits CEP170 to reprogram host microtubule organization. J Cell Sci 128:3420–3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bärenz F, Kschonsak YT, Meyer A, Jafarpour A, Lorenz H, Hoffmann I. 2018. Ccdc61 controls centrosomal localization of Cep170 and is required for spindle assembly and symmetry. Mol Biol Cell 29:3105–3118. 10.1091/mbc.E18-02-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guarguaglini G, Duncan PI, Stierhof YD, Holmström T, Duensing S, Nigg EA. 2005. The forkhead-associated domain protein Cep170 interacts with polo-like kinase 1 and serves as a marker for mature centrioles. Mol Biol Cell 16:1095–1107. 10.1091/mbc.e04-10-0939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Normand G, King RW. 2010. Polyploidization and cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol 676:27–55. 10.1007/978-1-4419-6199-0_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Meier K, Jachmann LH, Pérez L, Kepp O, Valdivia RH, Kroemer G, Sixt BS. 2022. The Chlamydia protein CpoS modulates the inclusion microenvironment and restricts the interferon response by acting on Rab35. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.02.18.481055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 79.Mital J, Miller NJ, Fischer ER, Hackstadt T. 2010. Specific chlamydial inclusion membrane proteins associate with active Src family kinases in microdomains that interact with the host microtubule network. Cell Microbiol 12:1235–1249. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01465.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Weber MM, Bauler LD, Lam J, Hackstadt T. 2015. Expression and localization of predicted inclusion membrane proteins in Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun 83:4710–4718. 10.1128/IAI.01075-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mital J, Lutter EI, Barger AC, Dooley CA, Hackstadt T. 2015. Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT850 interacts with the dynein light chain DYNLT1 (Tctex1). Biochem Bioph Res Co 462:165–170. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Belland RJ, Zhong G, Crane DD, Hogan D, Sturdevant D, Sharma J, Beatty WL, Caldwell HD. 2003. Genomic transcriptional profiling of the developmental cycle of Chlamydia trachomatis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:8478–8483. 10.1073/pnas.1331135100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Weber MM, Lam JL, Dooley CA, Noriea NF, Hansen BT, Hoyt FH, Carmody AB, Sturdevant GL, Hackstadt T. 2017. Absence of specific Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane proteins triggers premature inclusion membrane lysis and host cell death. Cell Rep 19:1406–1417. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Almeida F, Luís MP, Pereira IS, Pais SV, Mota LJ. 2018. The human centrosomal protein CCDC146 binds Chlamydia trachomatis inclusion membrane protein CT288 and is recruited to the periphery of the chlamydia-containing vacuole. Front Cell Infect Mi 8:254. 10.3389/fcimb.2018.00254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Firat-Karalar EN, Sante J, Elliott S, Stearns T. 2014. Proteomic analysis of mammalian sperm cells identifies new components of the centrosome. J Cell Sci 127:4128–4133. 10.1242/jcs.157008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhong G, Fan P, Ji H, Dong F, Huang Y. 2001. Identification of a chlamydial protease–like activity factor responsible for the degradation of host transcription factors. J Exp Medicine 193:935–942. 10.1084/jem.193.8.935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jorgensen I, Bednar MM, Amin V, Davis BK, Ting JPY, McCafferty DG, Valdivia RH. 2011. The chlamydia protease CPAF regulates host and bacterial proteins to maintain pathogen vacuole integrity and promote virulence. Cell Host Microbe 10:21–32. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen AL, Johnson KA, Lee JK, Sütterlin C, Tan M. 2012. CPAF: a chlamydial protease in search of an authentic substrate. PLoS Pathog 8:e1002842. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.da Cunha M, Milho C, Almeida F, Pais SV, Borges V, Maurício R, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP, Mota LJ. 2014. Identification of type III secretion substrates of Chlamydia trachomatis using Yersinia enterocolitica as a heterologous system. BMC Microbiol 14:40. 10.1186/1471-2180-14-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pais SV, Milho C, Almeida F, Mota LJ. 2013. Identification of novel type III secretion chaperone-substrate complexes of Chlamydia trachomatis. PLoS One 8:e56292. 10.1371/journal.pone.0056292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Muschiol S, Boncompain G, Vromman F, Dehoux P, Normark S, Henriques-Normark B, Subtil A. 2011. Identification of a family of effectors secreted by the type III secretion system that are conserved in pathogenic chlamydiae. Infect Immun 79:571–580. 10.1128/IAI.00825-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pais SV, Key CE, Borges V, Pereira IS, Gomes JP, Fisher DJ, Mota LJ. 2019. CteG is a Chlamydia trachomatis effector protein that associates with the Golgi complex of infected host cells. Sci Rep 9:6133. 10.1038/s41598-019-42647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Steiert B, Icardi CM, Faris R, Klingelhutz AJ, Yau PM, Weber MM. 2022. The Chlamydia trachomatis type III secreted effector protein CteG induces centrosome amplification through interactions with centrin-2. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.06.23.496711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 94.Salisbury JL, Suino KM, Busby R, Springett M. 2002. Centrin-2 is required for centriole duplication in mammalian cells. Curr Biol 12:1287–1292. 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pereira IS, Pais SV, Borges V, Borrego MJ, Gomes JP, Mota LJ. 2022. The type III secretion effector CteG mediates host cell lytic exit of Chlamydia trachomatis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 12:902210. 10.3389/fcimb.2022.902210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chellas-Géry B, Linton CN, Fields KA. 2007. Human GCIP interacts with CT847, a novel Chlamydia trachomatis type III secretion substrate, and is degraded in a tissue-culture infection model. Cell Microbiol 9:2417–2430. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Xia C, Bao Z, Tabassam F, Ma W, Qiu M, Hua S, Liu M. 2000. GCIP, a novel human Grap2 and Cyclin D interacting protein, regulates E2F-mediated transcriptional activity. J Biol Chem 275:20942–20948. 10.1074/jbc.M002598200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Falk JE, Campbell IW, Joyce K, Whalen J, Seshan A, Amon A. 2016. LTE1 promotes exit from mitosis by multiple mechanisms. Mol Biol Cell 27:3991–4001. 10.1091/mbc.E16-08-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]