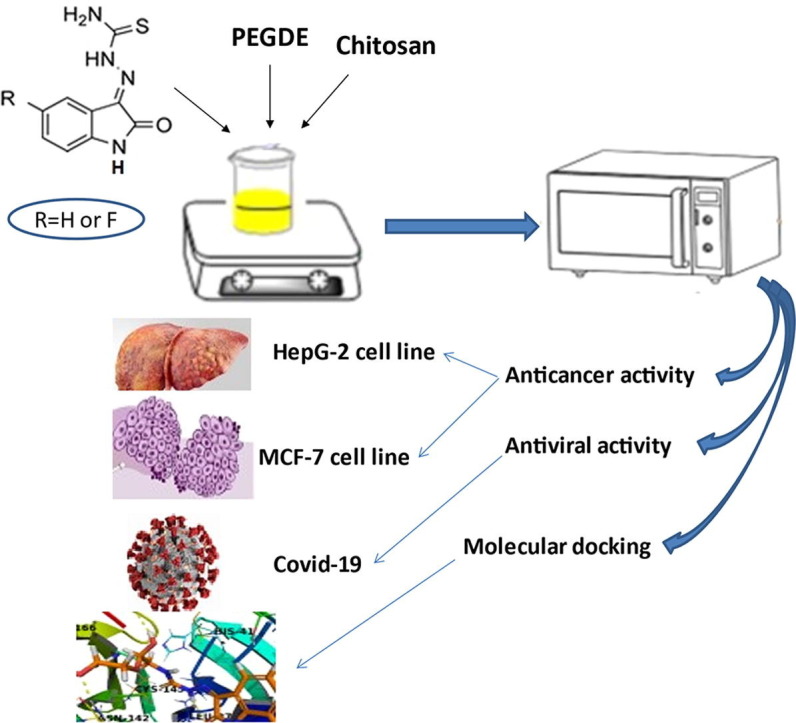

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Chitosan and chitosan NP’s derivatives, COVID-19, Anticancer, Molecular docking

Abstract

Chitosan (CS) is a biopolymer and has reactive amine/hydroxyl groups facilitated its modifications. The purpose of this study is improvement of (CS) physicochemical properties and its capabilities as antiviral and antitumor through modification with 1-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)thiosemicarbazide (3A) or 1-(5-fluoro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)thiosemicarbazide (3B) via crosslinking of poly(ethylene glycol)diglycidylether (PEGDGE) using microwave-assisted as green technique gives (CS-I) and (CS-II) derivatives. However, (CS) derivatives nanoparticles (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs) are synthesized via ionic gelation technique using sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP). Structures of new (CS) derivatives are characterized using different tools. The anticancer, antiviral efficiencies and molecular docking of (CS) and its derivatives are assayed. (CS) derivatives and its nanoparticles show enhancement in cell inhibition toward (HepG-2 and MCF-7) cancer cells in comparison with (CS). (CS-II NPs) reveals the lowest IC50 values are 92.70 ± 2.64 μg/mL and 12.64 µ g/mL against (HepG-2) cell and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) respectively and the best binding affinity toward corona virus protease receptor (PDB ID 6LU7) −5.71 kcal / mol. Furthermore, (CS-I NPs) shows the lowest cell viability% 14.31 ± 1.48 % and the best binding affinity −9.98 kcal/moL against (MCF-7) cell and receptor (PDB ID 1Z11) respectively. Results of this study demonstrated that (CS) derivatives and its nanoparticles could be potentially employed for biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

A globally spreading disease known as COVID-19, which is a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by a totally new coronavirus called “SARS-CoV-2,” is still causing havoc on the medical and health industries (Modak et al., 2021, Chowdhury et al., 2021, Packialakshmi et al., 2021a). The rapid transmission rate of SARS-CoV-2 has resulted in an increase in COVID cases, putting extra strain on health systems (Singh et al., 2021). Additionally, cancer-related morbidity and mortality have become a global issue in recent years, posing a constant threat to human society's well-being and medical system (Mi et al., 2021, Packialakshmi et al., 2021b). Breast, liver, lung, and prostate cancers are the most frequent cancer types causing deaths. The alarming mortality rate is the result of delayed tumor diagnosis and the lack of treatment options for advanced cancer stages (Prateeksha et al., 2021). The design and development of a multifunctional delivery system is one of the most difficult tasks in cancer treatment (Wang et al., 2010).

Chitosan is a natural polycationic carbohydrate biopolymer derived by the deacetylation of chitin. Chitosan consists of β-1,4-glucosamine and β-1,4-N-acetyl glucosamine residues (Kandile et al., 2018). Due to its excellent characteristics and potentials as biocompatibility, biodegradability, biosafety, and nontoxicity, chitosan and its derivatives have become a hot topic in research on transdermal drug delivery (Kavianinia et al., 2014, Kavianinia et al., 2015, Kavianina et al., 2016), modifiability in biological applications (Abdalla et al., 2022, Ahmed et al., 2020, Ibrahim et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021), and new applications for them are constantly being created including preventing cancer (Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021), viral (Chowdhury et al., 2021, Modak et al., 2021, Packialakshmi et al., 2021a, Singh et al., 2021), and decreasing blood fat (Ma et al., 2022).

The extensive review by Chirkov (Chirkov, 2002) well acknowledged chitosan as an antiviral agent and recent reports of chitosan as a plausible molecule for combat COVID-19 disease are well documented in literature by Sharma et al. (Sharma et al., 2021) and Safarzadeh et al. (Safarzadeh et al., 2021). According to literatures reported, chitosan and its derivatives nanoparticles achieve antitumor effects and statistically significant decrease in cell viability for cancer cells such as HepG-2 (Li et al., 2021, Mi et al., 2021), MCF-7 (Mi et al., 2021, Wang et al., 2010), A549, BGC-823 (Mi et al., 2021), and Vero cell (Kandile and Mohamed, 2021).

Chemical modifications of biopolymers have been demonstrated to improve physical properties, and controlled drug delivery, especially for chemotherapeutic agents (Horo et al., 2021). Polymers such as polyethylene glycol, chitosan, poly lactic-co-glycolic acid, and others have been utilized to create core–shell structures to encapsulate a variety of drugs (Wang et al., 2010).

Chitosan may easily interact with other molecules due to the large number of functional groups (hydroxyl and amine groups) on its backbone, which could provide chitosan-based products desired qualities (Mi et al., 2021), also the abundance of active groups in chitosan makes it possible to carry out a wide range of reactions to produce chitosan derivatives with different structures, properties, and functions (Abdalla et al., 2022, Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kavianinia et al., 2014, Kavianinia et al., 2015, Kavianina et al., 2016, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021).

Chitosan-based nanomaterials play a vital role in the biomedical field because of their unique properties such as biodegradable, biocompatible, non-toxic, and antimicrobial nature (Abdalla et al., 2022, Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Ibrahim et al., 2020, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021).

In the biomedical field, chitosan nanoparticles have been widely used in the biomedical industry as delivery systems for drugs, vaccines, and genes (Mi et al., 2021).

Isatin (indoline-2,3-dione) is a nitrogen-containing heterocyclic aromatic molecule present in plants, human blood, and tissue that serves as a key species in the synthesis of a variety of heterocyclic chemicals. Isatin moiety and isatin thiosemi- carbazone derivatives are responsible for a variety of biological and pharmacological properties such as antiviral, antimicrobial, antitubercular, antimalarial, antifungal, antibacterial, and anticancer (Abbas et al., 2013, Aziz et al., 2020, Divar et al., 2017).

As part of our ongoing efforts to prepare broad-spectrum bioactive chitosan derivatives (Abdalla et al., 2022, Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kavianinia et al., 2014, Kavianinia et al., 2015, Kavianina et al., 2016, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021), the aim of the current study was modification of chitosan with bioactive heterocyclic compounds istain carbazone derivatives (3A, 3B) (Abbas et al., 2013, Aziz et al., 2020, Divar et al., 2017, Singh et al., 2017) through crosslinking with (PEGDGE) as noncytotoxic polymers for biomedical applications (Liu et al., 2019, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021) using microwave-assisted as eco-friendly method (Gan et al., 2021, Priyadarshi et al., 2022) to give (CS-I) and (CS-II) derivatives respectively. However, (CS) derivatives nanoparticles (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs) were prepared under the same reaction conditions using ionic gelation technique in presence of (TPP). The structures of (CS) derivatives and its nanoparticles were confirmed by (FTIR) and Elemental analysis. The thermal stability for all (CS) derivatives was studied using (TGA) analysis. Besides, (SEM) images used to study the morphology structure of (CS) derivatives, and the nanoparticle size measured by (TEM). The crystallinity of (CS) and its derivatives was investigated by (XRD) analysis. Finally, evaluation of the activity of new modified chitosan derivatives and its nanoparticles to anticancer activities toward HepG-2 (hepatocellular cancer), MCF-7 (breast cancer) cell lines, antiviral ability against SARS-CoV-2 (COVID 19), and study of molecular docking toward (PDB ID 6LU7) and (PDB ID 1Z11) as corona virus protease receptors were studied.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Low molecular weight chitosan (CS) (degree of deacetylation (DD) 93.3 %, MW 60 KDa) was purchased from (Acros, Belgium). Isatin (indoline-2,3-dione) or 5-fluoroisatin (5-fluoroindoline-2,3-dione), were purchased from (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Glacial acetic acid, acetic acid, sodium chloride, thiosemicarbazide, and sodium tripolyphosphate (TPP) were provided from (Edwic, Egypt). Poly (ethylene glycol) diglycidyl ether (PEGDGE) was purchased from (Sigma-Aldrich, Japan). Absolute ethanol and dimethylformamide (DMF) were provided from (Merck, Germany) and (Caloarba, France) respectively. All aqueous solutions were prepared using distilled water.

2.2. Instrumentation

Elemental analyses were performed using a Perkin-Elmer 2400C, H, N elemental analyzer to report molar elements C, H, and N ratios. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra were obtained by casting a thin film onto a KBr plate and measuring them with a Thermo Scientific Smart Omni-Transmission instrument. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was obtained in temperatures ranging from 25 °C to 800 °C. using the SDT Q600 V20.9 Build 20, USA, in an inert nitrogen atmosphere at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. X-ray diffraction analysis (XRD) was used to investigate the crystalline and amorphous content of the prepared (CS) derivatives using analytical X'PERT PRO. A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) was used for sample morphological characterization and imaging. The samples were then examined using a Quanta 250 FEG (Field Emission Gun) and an EDX unit (Energy Dispersive X-ray Analysis). Finally, transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) was used to determine the shape and size of the nanoparticles. The samples were sonicated for 15 min before being placed on a carbon-coated copper grid. The coated grids were measured using a JEM − 1200 EX 2, Electron Microscope Jaban Specimens for (TEM).

2.2.1. Determination of the average molecular weight of (CS)

To determine the average molecular weight (MW) of (CS), viscometry was performed at 25 °C using a Brookfield viscometer. Various concentrations of (CS) were dissolved in a mixture of (0.1 M) acetic acid and (0.2 M) sodium chloride in this method. The viscosity of (CS) solutions and buffer solution was measured three times and the relative viscosity (η) calculated. Mark–Houwink–Sakurada’s empirical equation (Eq. (1)) (Kavianinia et al., 2014) was used to calculate chitosan (MW) based on the intrinsic viscosity [η]

| (1) |

Where k = 1.81 × 10-3 and a = 0.93 for the buffer solution at 25 °C.

2.3. Experimental

2.3.1. Preparation of 1-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene) thiosemicarbazide (3A) or 1-(5-fluoro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene) thiosemicarbazide (3B)

A mixture of isatin (1A) or 5-fluoroisatin (1B) (0.01 mol), thiosemicarbazide (2) (0.91 g, 0.01 mol) and a catalytic amount of acetic acid (2–3 drops) were dissolved in ethanol (15 mL). The reaction mixture was refluxed for 7 h and the reaction completion was checked by TLC. The solution was kept in a refrigerator overnight. The solid formed was filtered, washed with ethanol (2 × 5 mL), and crystallization from mixture solvent MeOH and H2O to give yellow crystalline (3A, 3B) m.p 235 °C, and 280 °C, yield 90 % and 89 % respectively (Abbas et al., 2013, Aziz et al., 2020, Singh et al., 2017).

2.3.2. 3.2. Modification of (CS) with thiosemicarbazone derivatives (3A) or (3B) in presence of (PEGDGE)

Chitosan (0.5 g) was dissolved into aqueous acetic acid (50 mL, 1 % v/v) under vigorous stirring at room temperature until complete dissolution. (PEGDGE) (6 mL), and solution of thiosemicarbazone derivatives (3A) or (3B) (0.5 g) in DMF (3 mL) were added to (CS) solution. The reaction mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature to give milky yellow solution which irradiated in a microwave oven (Gan et al., 2021, Priyadarshi et al., 2022) until yellow or orange solution was obtained during (7 × 2) min at (400 W, 50 Hz, 230 V) to complete the reaction. The solid formed after cooling at room temperature was washed with (DMF) to remove the unreacted thiosemicarbazone derivatives, then aqueous (NaOH) to neutralize the excess of acetic acid solution, finally with distilled water and left to dry in oven at 60 °C to give (CS-I) and (CS-II) derivatives in orange or yellow color respectively.

2.3.3. Preparation of (CS) derivatives nanoparticles (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs)

The in-situ ionotropic gelation (Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021) was performed to prepare crosslinked (CS) nanoparticles (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs) in presence of (TPP) as crosslinker.

Briefly, clear (CS) solution was prepared by dissolving (0.5 g, 1 % wt/v in 50 mL acetic acid 1 % v/v) under stirring at room temperature, then (PEGDGE) (6 mL) and (DMF) solution (3 mL) of thiosemicarbazone derivatives (3A) or (3B) (0.5 g) were added and left under stirring for 30 min. An aqueous solution of (TPP) (20 mL, 1 % wt/v) was added dropwise and the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature followed by a microwave irradiation (Gan et al., 2021, Priyadarshi et al., 2022) for (7 × 2) min at (400 W, 50 Hz, 230 V). The solid formed was cooled at room temperature, then washed with (DMF), aqueous (NaOH), distilled water and dried in an oven at 60 °C to give (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs) derivatives in yellow color.

2.4. In vitro cytotoxicity study

2.4.1. Anticancer study

2.4.1.1. Cancer cell cultures

MCF-7 (breast cancer) and HepG-2 (hepatocellular cancer) mammalian cell lines were acquired from the VACSERA Tissue Culture Unit. The cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), which included 10 % heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum, 1 % l-glutamine, (HEPES buffer), and 50 g/ml gentamycin. All cells were kept at 37°Celsius in a humidified environment with 5 % CO2 and were subcultured twice a week.

2.4.1.2. Viability assay

The viability assay was used to assess the cytotoxicity of the tested polymers. In a 96-well plate, the cells were seeded at a cell concentration of (1 × 104) cells per well in (100 µL) of growth medium. After 24 h of seeding, fresh medium containing different concentrations of the tested polymers was added. Using a multichannel pipette, serial twofold dilutions of the tested polymers were added to confluent cell monolayers and dispensed into 96-well, flat-bottomed microtiter plates (Falcon, NJ, USA). The microtiter plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5 % CO2. For each concentration of the test sample, three wells were used. Control cells were incubated with or without the tested polymers, as well as with or without (DMSO) (maximal 0.1 %). Following cell incubation, viable yield was determined using a colorimetric method with crystal violet solution (1 %) added to each well for at least 30 min. The stain was removed, and the plates were rinsed with tap water to remove any remaining stain. Glacial acetic acid (30 %) was then added to all wells, thoroughly mixed, and the absorbance of the plates was measured on a Microplate reader (TECAN, Inc.) after gently shaking with a test wavelength of 490 nm. Background absorbance detected in wells without added stain was corrected for in all results (Gomha et al., 2015, Mosmann, 1983).

2.4.2. Antiviral study

Stock solutions of the examined compounds in10 % DMSO were diluted to the working ones with DMEM to calculate the half-maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC 50). MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) method was applied with minor changes to evaluate the cytotoxic activity of the tested compounds in VERO-E6 cells. The entire methodology was performed in details, as described earlier (Of, 2016). The cytotoxicity percentage was determined using the following equation:

Inhibitory concentration 50 (IC50) determinations

The IC50 concentrations of the tested compounds were determined as previously described (Feoktistova et al., 2016). The IC 50 is the concentration required to decrease the cytopathic effect (CPE) of the virus by 50 %, compared to the virus control. The virology study was covered partially by funding from the Egyptian Academy of Scientific Research and Technology (ASRT) within the “Ideation Fund” program under contract numbers 7303.

2.5. Molecular docking

The new synthesized compounds were subjected to molecular docking to recognize their binding modes and free energies of binding towards corona virus protease (Li et al., 2021, Packialakshmi et al., 2021a) and methoxsalen (Packialakshmi et al., 2021b) receptors. Therefore, crystallographic structure of corona virus protease and methoxsalen receptors in complex with co-crystalized ligands, was retrieved from Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6LU7 and 1Z11). The docking result analysis was performed using AutoDock program. The 2D chemical structures of the synthesized compounds and co-crystalized ligand were sketched using ChemBioDraw Ultra 14.0. To assess the efficacy of the method used for docking, we performed molecular redocking of co-crystalized ligands, which validated by getting low RMSD values between the docked and X-ray structures. Then the docking of co-crystalized ligand and the synthesized compounds were performed using default protocol parameters. The docking results from Auto Dock program was further analyzed and visualized using Pymol software to investigate the putative interaction mechanism with corona virus protease and methoxsalen targets.

2.6. Statistical Analysis.

All the assays were expressed as a mean value with its standard deviation (mean ± S.D) of each sample that is repeated three times (n = 3). A difference was considered statistically significant when the p-value was less than 0.05.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemistry

3.1.1. Synthesis of 1-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene) thiosemicarbazide (3A) or 1-(5-fluoro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene) thiosemicarbazide (3B)

Isatin and its derivatives have recently sparked a lot of interest. They have a wide range of biological activities (Divar et al., 2017) especially fluorinated isatin derivatives that revealed the development of pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties such as absorption, tissue distribution, secretion, the route and rate of biotransformation, toxicology, bioavailability, and metabolic stability. Additionally, isatin thiosemi- carbazone derivatives are used as a preventive medication against a variety of viral infections (Abbas et al., 2013).

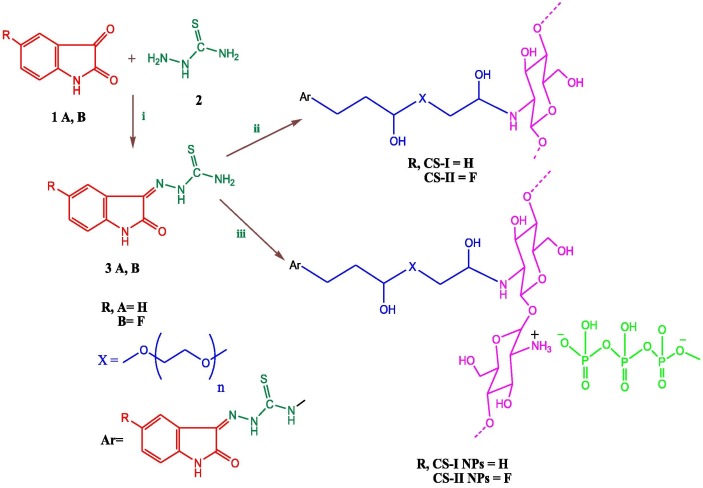

In this study, isatin thiosemicarbazone derivatives (3A, 3B) were prepared by reacting of isatin or 5-fluoroisatin (1A, 1B) and thiosemicarbazide (2) via condensation reaction (Abbas et al., 2013, Aziz et al., 2020, Singh et al., 2017) (Scheme 1 ).

Scheme 1.

Preparation of isatin carbazone derivatives, (CS) derivatives and its nanoparticles (i) EtOH/Reflux, (ii) Chitosan and (PEGDGE)/ Microwave, and (iii) Chitosan, (PEGDGE), and (TPP) / Microwave.

3.1.2. Preparation of (CS) derivatives and its derivatives nanoparticles

The use of chemically modified biopolymers and polymeric nanoparticles has been documented as a feasible strategy for increasing drug bioavailability ensuring the sustained and long-term release of encapsulated medicines improved antiviral and anticancer accumulation and fewer negative side effects (Horo et al., 2021, Mi et al., 2021, Pyrć et al., 2021).

From the above facts two (CS) derivatives (CS-I) and (CS-II) were prepared from the reaction of (CS) with carbazone derivatives (3A, 3B) and (PEGDGE) as biomedical crosslinker (Liu et al., 2019, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021) through epoxy ring opening of (PEGDGE) using microwave-assisted method.

(CS) derivatives nanoparticles (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs) were prepared by in-situ ionic gelation method via the interactions between the positively charged amine groups of (CS) and the negatively charged groups of polyanion crosslinker (TPP) (Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021) (Scheme 1).

3.2. Characterization of (CS) derivatives (CS-I) and (CS-II) and its derivatives NPs (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs)

3.2.1. Viscometry and elemental analysis

The viscometry method of Mark–Houwink–Sakurada was used to determine the average molecular weight (MW) of (CS), approximately 60 KDa as shown in (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Elemental analysis, (MW), and (DD%) for (CS) and (CS) derivatives.

| Comp. No. | C% | H% | N% | S% | C/N | DD% | MW KDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs | 38.48 | 7.01 | 7.31 | – | 5.26 | 93.3 | 60 |

| Cs-I | 48.16 | 8.34 | 2.66 | 0.16 | |||

| CS-II | 43.25 | 7.22 | 2.99 | 0.83 |

The percentage of free amine group on (CS) backbone was calculated using (Eq. (2) (Kasaai et al., 2000). The degree of deacetylation for (CS) is determined from the elemental analysis of (CS) and the percentage employed in this study was 93.3 %. The percentage of carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and degree of deacetylation of (CS) were represented in (Table 1).

| (2) |

Where C/ N ratio displayed C% and N% for (CS), and 5.145 and 6.861 values referred to N-deacetylated chitosan (C6H11O4N) and N-acetylated chitin (C8H13O5N) repeat unit, respectively.

Additionally, from elemental analysis which displayed S% and higher C and H % compared to C and H % of (CS) confirmed the formation of (CS-I), and (CS-II) derivatives as shown in (Table 1).

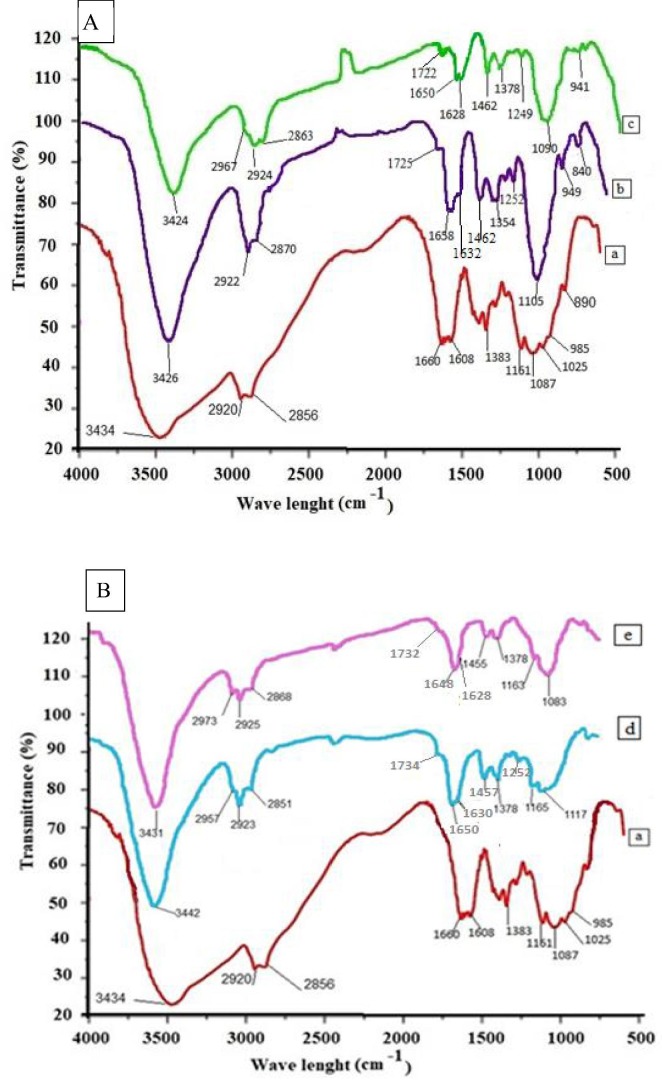

3.2.2. FTIR spectroscopy

Structures of (CS), (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) were confirmed by FTIR as shown in (Fig. 1 (A, B). The major bands observed for (CS), a broad band at 3434 cm−1 corresponding to the overlapping of O—H and N—H (NH2) stretching vibration. Two bands at 2920 cm−1 and 2856 cm−1 referred to C—H aliphatic stretching vibration and a peak at 1660 cm−1 due to C O of the acetyl group present in the (CS) structure (Abdalla et al., 2022, Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kavianinia et al., 2014, Kavianinia et al., 2015, Kavianina et al., 2016, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021). FTIR spectra in (Fig. 1 (A, B) for (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) showed similar profiles to those of (CS) with shifted values such as peaks at 3442 cm−1 − 3424 cm−1 attributed to stretching vibration (O—H and N—H groups) and bands at 1658 cm−1 − 1648 cm−1 due to (C O group) at N- acetylated unit. In addition, the crosslinking of (CS) with (PEGDGE) was confirmed by appearance of new peaks at 2973–2851 cm−1 with high intensity were ascribed to aliphatic C—H long chain of (PEGDGE) (Kandile and Mohamed, 2021). Moreover, the new characteristic bands at 1734 cm−1 −1722 cm−1, at 1632 cm−1 − 1628 cm−1 and at 1252 cm−1 − 1249 cm−1 referred to (C O, C N and C S groups) (Mohamed et al., 2017) can demonstrate the successful modification of (CS) and isatin carbazone derivatives.

Fig. 1.

A) FTIR of a) CS, b) CS-I, and c) CS-II, and B) FTIR of d) CS-I NPs and e) CS-II NPs.

Furthermore, (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) illustrated new peaks at 1542 cm−1 − 1541 cm−1, 1165 cm−1 − 1163 cm−1 referred to (vibration P—O) of (TPP), and another two peaks at 1123 cm−1 − 1117 cm−1 and 998 cm−1 − 995 cm−1 pointed to (PO3 2− group) (Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021) confirmed the ionic gelation between (CS) derivatives and (TPP).

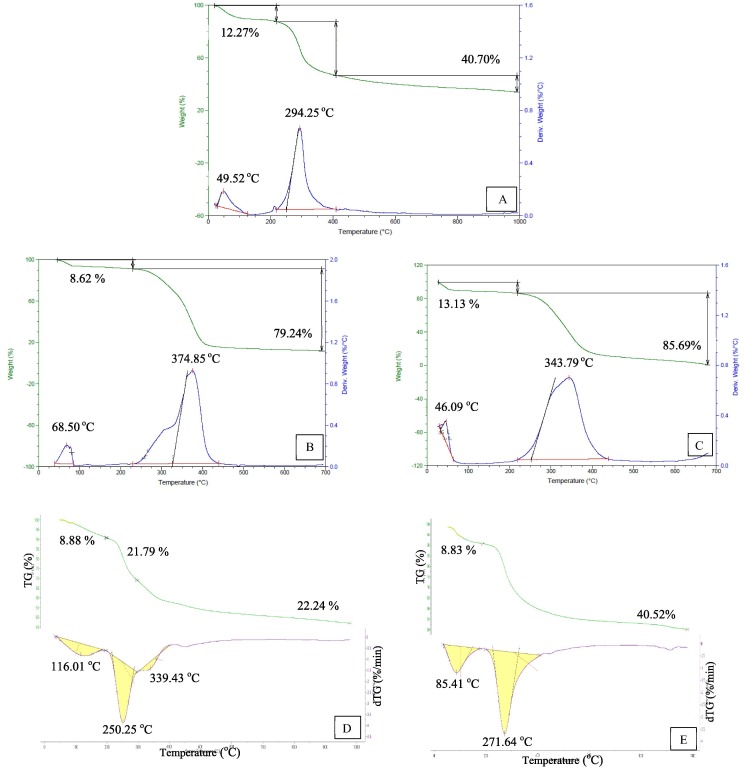

3.2.3. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA).

The thermal stability of (CS), crosslinked (CS) and its derivatives NPs was assessed using (TGA) and represented in (Fig. 2 , Table 2 ). Overall, (TGA) curves showed a very small mass loss due to moisture evaporation (Raju et al., 2021) with an initial weight loss 12.27 %, 8.62 %, 13.13 %, 8.88 %, and 8.83 % at 49.52 °C, 68.50 °C, 46.09 °C, 116.01 °C, and 85.41 °C for (CS), (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) respectively. The actual degrading step of (CS) was found at 294.25° corresponding to a mass loss of 40.70 %. (Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021). Furthermore, the onset degradation temperature with weight loss 79.24 %, 85.69 %, and 40.52 % at 374.85 °C, 343.79 °C, and 271.64 °C for (CS-I), (CS-II), and (CS-II NPs) respectively, while (CS-I NPs) representing two degradation steps at 250.25 °C and 339.43 °C with mass loss 21.78 % and 22.24 % respectively may be pointed to the thermal decomposition of carbazone moiety and polymeric chain for crosslinked (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs.

Fig. 2.

TGA of A) CS, B) CS-I, C) CS-II, D) CS-I NPs and E) CS-II NPs.

Table 2.

Thermal properties for (CS), (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs.

| Comp. No. | Temp. | Weight loss% | Temp. | Weight loss% | Temp. | Weight loss% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs | 49.52 | 12.27 | 294.25 | 40.70 | – | – |

| Cs-I | 68.50 | 8.62 | 374.85 | 79.24 | – | – |

| CS-II | 46.09 | 13.13 | 343.79 | 85.69 | – | – |

| Cs-I NPs | 116.01 | 8.88 | 250.25 | 21.79 | 339.43 | 22.24 |

| Cs-II NPs | 85.41 | 8.83 | 271.64 | 40.52 | – | – |

As observed in (Fig. 2) (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs have increased the thermal stability compared to (CS) except (CS-II NPs). This high thermal stability may be attributed to cleavage of C—C linkages in long aliphatic chain indicated improved cross-linking between chitosan and (PEGDGE) (Kandile and Mohamed, 2021).

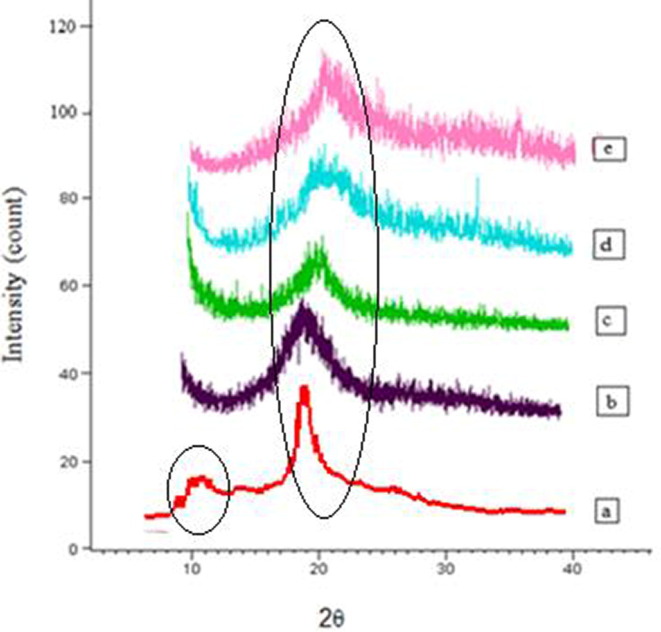

3.2.4. X-ray diffraction (XRD)

The (XRD) patterns of (CS), new (CS) derivatives, and its derivatives NPs were shown in (Fig. 3 ). (CS) displayed two peaks at 2θ = 10° (small) and 2θ = 20° (broad) (Elzamly et al., 2021). However, (CS) derivatives, and its derivatives NPs revealed only one peak around 2θ = 20° (broad) while the peak reported for (CS) at 2θ = 10° disappeared indicating to increased amorphous nature of (CS) derivatives and decrease the crystal structure of (CS) referred to good compatibility of (CS) in the crosslinked reaction (El Hamdaoui et al., 2021).

Fig. 3.

X-ray of a) CS, b) CS-I, c) CS-II, d) CS-I NPs and e) CS-II NPs.

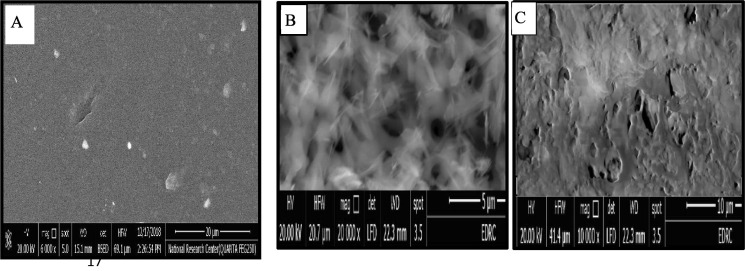

3.2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) was used to characterize the surface morphology of (CS-I), and (CS-II) at 5 and10 μm respectively showed rough and irregular morphological structure as shown in (Fig. 4 (B, C)) compared with the smooth surface of (CS) as shown in (Fig. 4 A) (Abdalla et al., 2022, Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Ibrahim et al., 2020, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021). This observation can be explained by breaking of hydrogen bonds in (CS) due to involving amine groups of (CS) in the reaction with (PEGDGE) (El Hamdaoui et al., 2021).

Fig. 4.

SEM for A) CS, B) CS-I, and C) CS-II.

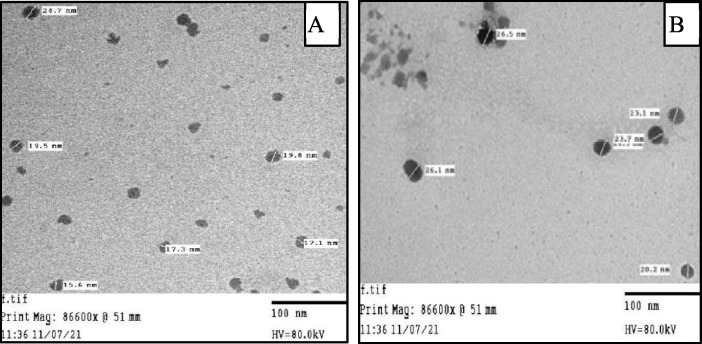

3.2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images were measured at 100 nm in (Fig. 5 (A, B)) for (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) revealed that NPs were disseminated as individual NPs with a well-defined spherical shape and a homogeneously distributed. Moreover, the particle size diameter of (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) were found to be in the range of 12–38 nm and 14–32 nm respectively and confirmed the successful ionic gelation process between negatively phosphate group of (TPP) and positively amine group of (CS) skeleton as reported in our previous studies (Ahmed et al., 2020, Elzamly et al., 2021, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021).

Fig. 5.

TEM for A) CS-I NPs, and B) CS-II NPs.

3.3. Cytotoxicity studies

3.3.1. Viability assay

Cancer is predicted to be the reason of 17 million deaths per year worldwide by 2030. The increasing mortality rate is due to the late detection of tumors and the lack of therapeutic options for advanced cancer stages. Various functional groups, namely hydroxyl and amine make them perfect for optimizing all aspects of therapeutic (Prateeksha et al., 2021). (CS) as a natural polysaccharide, is widely used in biomedical applications due to its owing to numbers of functional groups (hydroxyl and amine) on its backbone (Li et al., 2021).

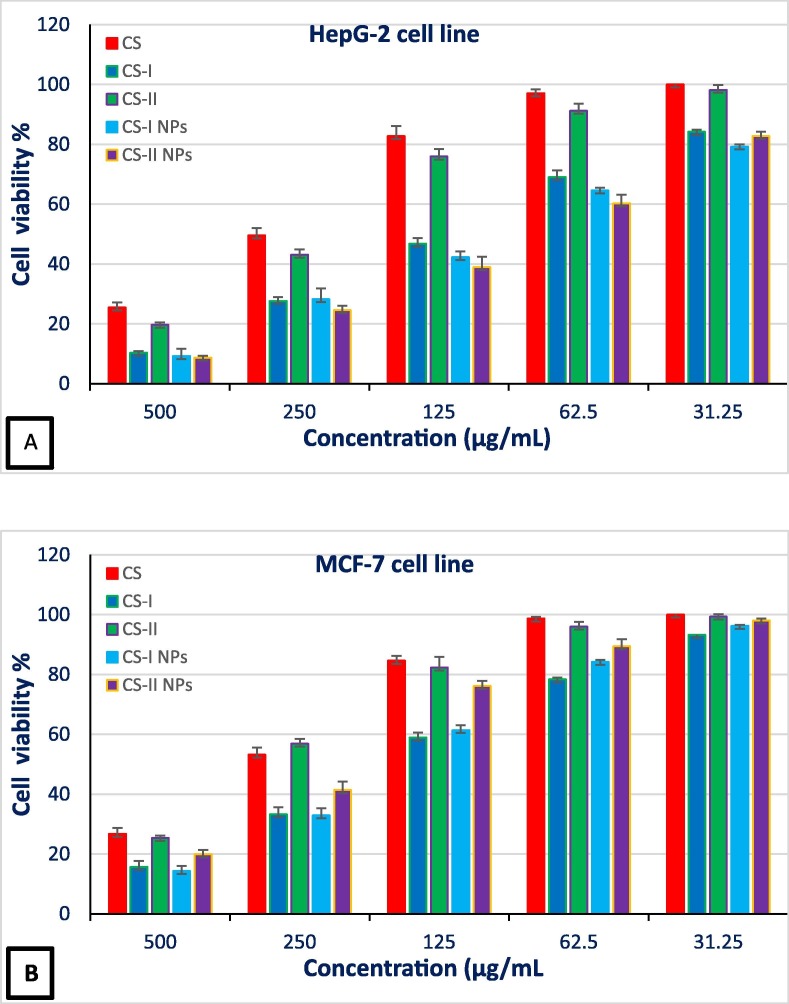

To evaluate the antitumor activities of (CS), (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) against two types of cancer cells HepG-2 (hepatocellular cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer), the viability assay (Ali et al., 2023, Kandile et al., 2020, Kandile and Mohamed, 2021 ) was used on a series of concentrations ranging from 31.25 − 500 μg/mL as shown in (Fig. 6 (A, B),Table 3, Table 4 ).

Fig. 6.

(A) Cell viability % toward HepG-2 cell line at concentrations 31.25–500 μg/mL for (CS), (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs. (B) Cell viability % toward MCF-7 cells line at concentrations 31.25–500 μg/mL for (CS), (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs.

Table 3.

Cell viability % toward HepG-2 cell line for (CS), (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs.

| Comp. No. | Sample conc. (µg/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 250 | 125 | 62.5 | 31.25 | |

| Cs | 25.48 ± 1.66 | 49.61 ± 2.37 | 82.75 ± 3.41 | 97.06 ± 1.28 | 100 |

| Cs-I | 10.34 ± 0.82 | 27.65 ± 1.73 | 46.81 ± 53.19 | 69.08 ± 2.34 | 84.1 ± 1.58 |

| CS-II | 19.76 ± 2.48 | 43.12 ± 3.56 | 75.94 ± 1.82 | 91.26 ± 0.92 | 98.23 ± 0.71 |

| Cs-I NPs | 9.24 ± 0.62 | 28.26 ± 1.48 | 42.35 ± 3.51 | 64.57 ± 2.89 | 79.28 ± 1.46 |

| Cs-II NPs | 8.70 ± 0.34 | 24.61 ± 0.75 | 38.97 ± 1.41 | 60.32 ± 2.36 | 82.75 ± 1.39 |

Table 4.

Cell viability % toward MCF-7 cell line for (CS), (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs.

| Comp. No. | Sample conc. (µg/ml) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 250 | 125 | 62.5 | 31.25 | |

| Cs | 26.76 ± 1.96 | 53.19 ± 2.35 | 84.62 ± 1.64 | 98.74 ± 0.52 | 100 |

| Cs-I | 15.68 ± 0.74 | 33.27 ± 1.59 | 58.96 ± 3.48 | 78.42 ± 1.56 | 93.20 ± 0.84 |

| CS-II | 25.40 ± 1.68 | 56.91 ± 2.37 | 82.37 ± 1.59 | 96.02 ± 0.64 | 99.34 ± 0.28 |

| Cs-I NPs | 14.31 ± 1.48 | 32.95 ± 2.91 | 61.43 ± 1.68 | 84.20 ± 2.34 | 96.28 ± 0.68 |

| Cs-II NPs | 19.85 ± 1.43 | 41.36 ± 2.62 | 76.21 ± 1.97 | 89.47 ± 1.03 | 98.06 ± 0.82 |

Some conclusions could be summarized as follows: Lower cell viability of cancer cells represents higher antitumor activity. Modified (CS) derivatives and its NPs derivatives showed higher antitumor activities compared to (CS). The cell viability values were 25.48 ± 1.66 %, 10.34 ± 0.82 %, 19.76 ± 2.48 %, 9.24 ± 0.62 %, and 8.70 ± 0.34 % for (CS), (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) respectively against (HepG-2) cancer cell at concentration 500 μg/mL which displayed the highest antitumor activity for (CS-II NPs). Additionally, (CS-II NPs) revealed cell viability at concentration 250 μg/mL reached to 24.61 ± 0.75 % similar to (CS) NPs derivative reported by Y. Mi et al. (Mi et al., 2021) that showed cell viability value 22.55 % at concentration 320 μg/mL. Also, (CS) derivatives and its NPs derivatives revealed Lower IC50 values were 115.92 ± 2.86, 224.03 ± 3.89, 103.13 ± 2.75, and 92.70 ± 2.64 μg/mL for (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) than IC50 value was 249.17 ± 4.21 μg/mL for (CS).

In case of (MCF-7) cancer cell line, all (CS) derivatives possessed the lower cell viability in comparison with (CS) which values were 26.76 ± 1.96 %, 15.68 ± 0.74 %, 25.40 ± 1.68 %, 14.31 ± 1.48 % and 19.85 ± 1.43 % for (CS), (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) respectively at concentration 500 μg/mL. (CS-I NPs) derivative referred the minimum cell viability and higher anticancer efficacy compared to (CS) NPs derivative reported by M. H. Zaboon et al. (Zaboon et al., 2019) that showed cell viability value 17.33 ± 8.963 %.

In addition, lower IC50 values showed by (CS-I), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) derivatives were 169.57 ± 3.91 μg/mL, 175.16 ± 3.96 μg/mL, and 219.05 ± 4.67 μg/mL respectively compared to IC50 value was 280.14 ± 8.72 μg/mL for (CS). The improvement in cytotoxicity illustrated by (CS) derivatives might relate to the bioactive isatin carbazone moiety. It was reported that isatin and fluorinated isatin carbazone derivatives showed various chemotherapeutic properties such as anti-cancer (Abbas et al., 2013, Divar et al., 2017). Additionally, the assaying of cell viability showed that nanoparticles led to a statistically reduction in the cell viability of cancer cells and possessed strong antitumor activities may attributed to good biocompatibility, nanoparticle size and had a large surface area could increase the permeability into the cancer cells, hence increasing the antitumor activity (Mi et al., 2021).

3.3.2. Assessment of in vitro cytotoxicity and antiviral activity

Finding effective therapeutic interventions has become a top priority as the global case and fatality rates due to COVID-19 infection have risen. Marine resources are underutilized and should be considered when investigating antiviral potential. (CS) is one of these bioactive glycans found in nearly all marine organisms. We would like to test (CS) against SARS-CoV-2 because it contains reactive amine/hydroxyl groups with low toxicity/allergenicity (Modak et al., 2021).

Many studies have found that individuals who got drugs via nanoparticles had very little side effects. Nanoparticles could be very effective in the administration and the delivery of drugs medications for COVID-19 treatment (Chowdhury et al., 2021).

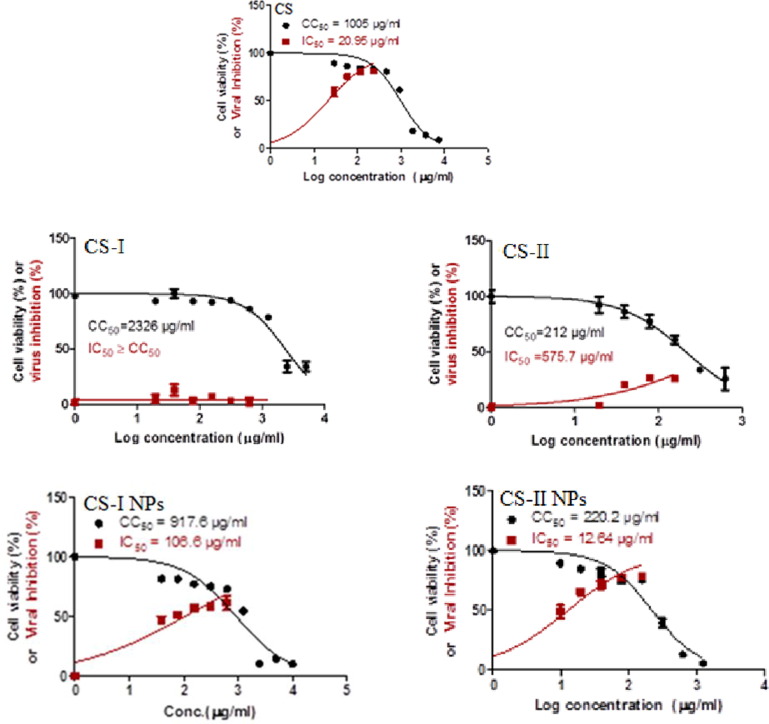

The cytotoxicity and virus-inhibitory impact of (CS), (CS-I), (CS-II), (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) were determined by finding the half-maximal cytotoxic CC50 and inhibitory IC50 doses for each drug. The ratio of the (CC50) to the (IC50) was used to calculate the selectivity index for each of these drugs. With IC50 values of 12µ g/mL, 20.95 µg/mL, and 106.6 µg/mL for (CS-II NPs), (CS) and (CS-I NPs) respectively, demonstrated potential their antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 as shown in (Fig. 7 , Table 5 ) especially, (CS-II NPs) which showed superior efficacy against COVID-19 coronavirus. Meanwhile, their selectivity indices were roughly 17.40, 47.97, and 8.60 for (CS-II NPs), (CS) and (CS-I NPs) respectively.

Fig. 7.

Cytotoxic concentration 50 (CC50) and inhibitory concentration (IC50) for (CS) and newly prepared derivatives of (CS). The cytotoxicity values for studied (CS) and (CS) derivatives were assessed on Vero E6 cells while their antiviral activities were evaluated against SARS-CoV-2 (hCoV-19/Egypt/NRC-03/2020 (Accession Number on GSAID. EPI_ISL_430820).

Table 5.

Cytotoxicity and virus inhibitory effect of (CS), (CS) derivatives and its nanoparticles against SARS-CoV-2.

| Comp. No. | ||

|---|---|---|

| CS | 1005 | 20.95 |

| CS-I | 2326 | ≥ |

| CS-II | 212 | ≥ |

| CS-I NPs | 917.6 | 106.6 |

| CS-II NPs | 220.2 | 12.64 |

Because most FDA-approved protease inhibitors lack anti-SARS-CoV-2 action, lopinavir demonstrated modest antiviral potential against SARS-CoV-2 with an IC50 of 5.73 M and a selectivity index of at least 8 (Chen et al., 2004, El Gizawy et al., 2021). We believe that (CS-II NPs), (CS-I NPs) and (CS) may be protease inhibitor candidates to combat SARS-CoV-2 replication when compared to lopinavir.

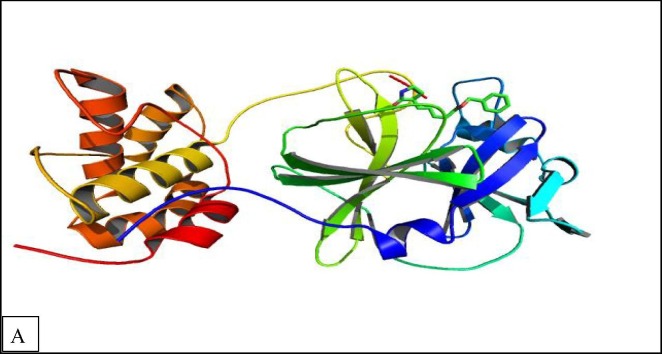

3.4. Docking studies

(CS) and (CS) derivatives NPs have been reported as potent for SARS corona virus protease (PDB ID 6LU7) (Jaber et al., 2022, Packialakshmi et al., 2021a) (Fig. 8A ). For better comprehend how (CS) NPs derivatives contributed to corona virus protease inhibitory activities, molecular docking investigation were conducted by using AutoDock 4.2 program. The molecular docking results indicated that the binding site location of docked compounds as that of co-crystallized ligand. Moreover, the molecular docking study results with corona virus receptor indicated that co-crystallized ligand, reference drug and (CS) NPs derivatives have similar binding mode patterns, and our study has confirmed that most of (CS) NPs derivatives have good binding affinities towards the receptor target ranging from −5.29 to −5.71 kcal/mol. Furthermore, the computed values of free energy for binding of chitosan and (CS) NPs derivatives reflect the overall trend (Table 6 ).

Fig. 8A.

X-ray structure of corona virus protease (PDB ID 6LU7).

Table 6.

Summary of free energy of binding, hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonding interactions of (CS) and (CS) derivatives NPs with corona virus protease binding site.

| Comp. No. | Total energy (kcal / mol) | Hydrogen bonding interactions |

cationic-π interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS-I NPs | −5.29 | Asn142, Glu166, and Gln189 | Thr24, Thr45, and Ser46 |

| CS-II NPs | −5.71 | Thr24, Thr26, Phe140, Gly143, Glu166, and His172 | Thr24, Thr45, and Ser46 |

| CS | −5.63 | Thr26, Asn142, and Gly143 |

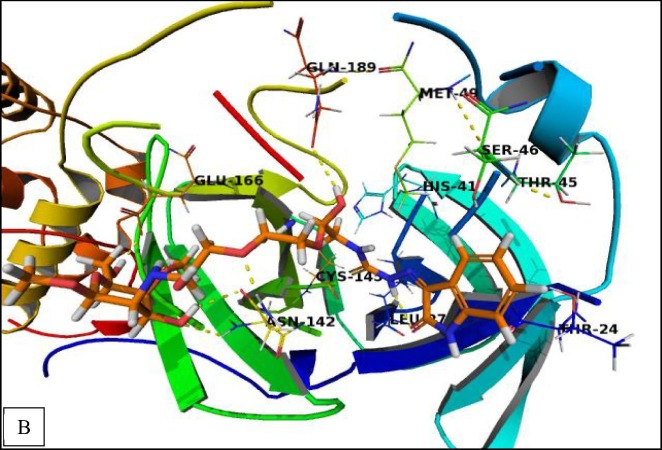

The obtained binding mode of (CS-I NPs) derivative revealed that four hydrogen bonding interactions with backbone and side chains of Asn142, Glu166, and Gln189. Isatin moiety can be stabilized by cationic-π interactions with Thr24, Thr45, and Ser46 as well as hydrophobic interactions with His41, Met49, Leu141, and Cys145 (Fig. 8B ).

Fig. 8B.

Crystal structure of corona virus protease receptor (PDB ID 6LU7) with (CS-I NPs). The hydrogen bonding interactions are presented by dashed lines. Residues contacting ligand are demonstrated as lines.

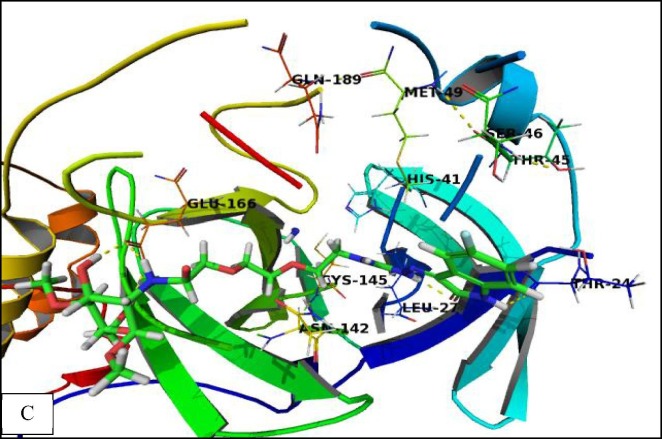

The binding mode of (CS-II NPs) was like that of (CS-I NPs). Furthermore, the amine and hydroxyl groups of (CS-II NPs) were involved in hydrogen bonding interactions with backbone amine group of Gly143, Glu166, and His172. Isatin moiety was stabilized by additional hydrogen bonding interactions with Thr24, Thr26, cationic-π interactions with Thr45, and Ser46 and hydrophobic interactions with His41, Met49, Leu141, and Cys145. These additional interactions seem to have a crucial role in the recognition process and may explain its higher affinity of (CS-II NPs) derivative compared with (CS-I NPs) derivative (Fig. 8C ).

Fig. 8C.

Crystal structure of corona virus protease receptor (PDB ID 6LU7) with (CS-II NPs) derivative. The hydrogen bonding interactions are presented by dashed lines. Residues contacting ligand are demonstrated as lines.

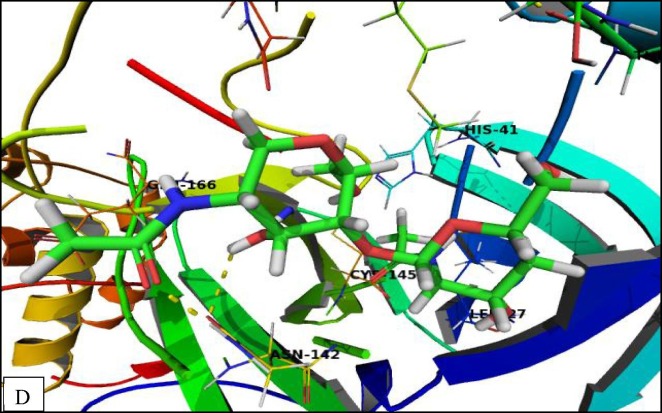

The binding mode of chitosan (Fig. 8D ) was like (CS-II NPs) derivative that cannot be completely accommodating the binding site. In addition, the hydrophilic moieties of (CS) were in a favorable hydrophilic interaction with Thr26, Asn142, and Gly143.

Fig. 8D.

Crystal structure of corona virus protease receptor (PDB ID 6LU7) with (CS) The hydrogen bonding interactions are presented by dashed lines. Residues contacting ligand are demonstrated as lines.

Molecular docking was added also to investigate how (CS) and (CS) derivatives NPs binding to receptor in the field of anticancer activity. Therefore, (CS) and (CS) derivatives NPs were docked into the methoxsalen (Prateeksha et al., 2021) protein receptor (PDB ID 1Z11) using AutoDock Tools.

The binding mode of (CS-I NPs) derivative which has the highest binding affinity indicated that isatin moiety was stabilized by aromatic stacking interactions with Phe107, Phe111, Phe118, Phe209, and Phe480 and located in hydrophobic interactions with Val110, Val117, Leu296, and Ile300. The hydroxyl groups of (CS) nucleus were involved in the hydrogen bonding interactions with Arg101, backbone carbonyl groups of Pro431, Arg437, and Phe440 (Fig. 8E ).

Fig. 8E.

Crystal structure of methoxsalen receptor (PDB ID 1Z11) with (CS-I NPs) derivative. The hydrogen bonding interactions are presented by dashed lines. Residues contacting ligand are demonstrated as lines.

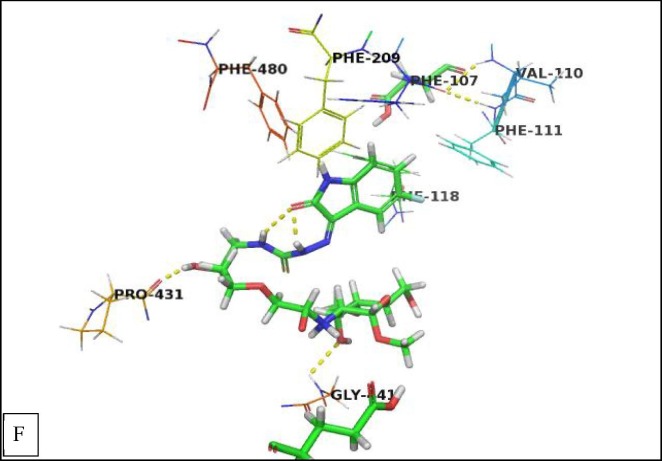

The binding mode of (CS-II NPs) derivative was like that of (CS-I NPs) derivative. The hydroxyl groups were involved in hydrogen bonding interactions with Pro431, and Gly441 and the other hydrogen bonding interactions were missed that may explain its lower affinity of (CS-II NPs) derivative compared with (CS-I NPs) derivative (Fig. 8F ).

Fig. 8F.

Crystal structure of methoxsalen receptor (PDB ID 1Z11) with (CS-I NPs) derivative. The hydrogen bonding interactions are presented by dashed lines. Residues contacting ligand are demonstrated as lines.

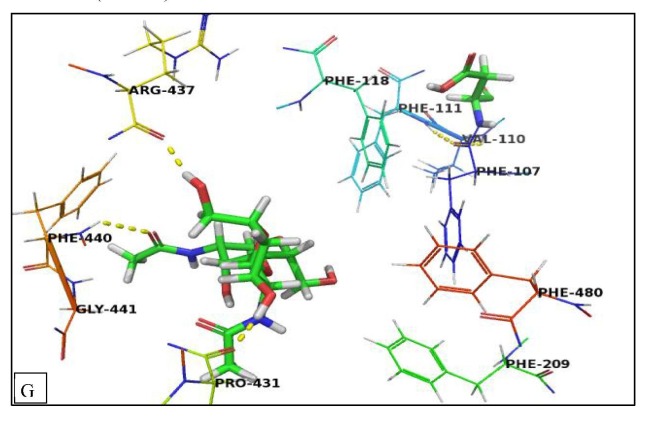

The binding mode of (CS) (Fig. 8G ) was like (CS-II NPs) derivative that can completely mobile inside the binding site. In addition, the polar groups were in an unfavorable hydrophilic interaction with Phe107, Val110, Phe111, and Phe118 that decrease its affinity compared with the other derivative. The molecular docking study results with methoxsalen receptor indicated that reference drug and (CS) derivatives NPs have similar binding mode patterns, and our study has confirmed that most of (CS) derivatives NPs have good binding affinities towards the receptor target ranging from −7.99 to −9.98 kcal/mol. Furthermore, the computed values of free energy of binding of (CS) derivatives NPs reflect the overall trend (Table 7 ).

Fig. 8G.

Crystal structure of methoxsalen receptor (PDB ID 1Z11) with (CS). The hydrogen bonding interactions are presented by dashed lines. Residues contacting ligand are demonstrated as lines.

Table 7.

Summary of free energy of binding, hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bonding interactions of (CS) and (CS) derivatives NPs with methoxsalen receptor binding site.

| Comp. No. | Total energy (kcal / mol) | Hydrogen bonding interactions | π-π interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

| CS-I NPs | −9.98 | Arg101, Pro431, Arg437, and Phe440 | Phe107, Phe111, Phe118, Phe209, and Phe480 |

| CS-II NPs | −8.83 | Pro431, and Gly441 | Phe107, Phe111, Phe118, Phe209, and Phe480 |

| CS | −7.99 | Phe440, Pro431, and Arg437 |

4. Conclusion

In summary, new (CS) derivatives (CS-I), (CS-II), and its derivatives NPs (CS-I NPs), and (CS-II NPs) were successfully prepared via reaction of (CS) with isatin carbazone derivatives (3A, 3B) through crosslinking with (PEGDGE) in absence or presence of (TPP) respectively. New (CS) derivatives were characterized by different tools. (SEM) showed rough morphological surface for (CS-I) and (CS-II) compared to smooth surface for (CS). (CS-I NPs) and (CS-II NPs) revealed particle size lower than 100 nm in (TEM) images. (CS) derivatives and its derivatives NPs displayed higher thermal stability and amorphous nature than (CS). Based on the results of the in-vitro anticancer evaluation, it was observed that (CS-II NPs) derivative was the most active member with the lowest IC50 92.70 μg/mL against HepG-2 cell line, while (CS-I) and (CS-I NPs) derivatives showed high potency against MCF-7 cell line (IC50 169.57 & 175 μg/mL) respectively. Furthermore, biological studies on these active (CS) derivatives were performed against SARS-CoV-2 virus. It was found that (CS-II NPs) derivative displayed promising activity with IC50 12.64 μg/mL. Docking studies revealed that isatin moiety in (CS-II NPs) derivative was stabilized by additional hydrogen bonding interactions with Thr24, Thr26, cationic-π interactions with Thr45, and Ser46 and hydrophobic interactions with His41, Met49, Leu141, and Cys145. These may be attributed to the highest activity of new (CS) derivatives against COVID-19 virus. These results suggested that the active new modified (CS) derivatives can be used as potential agents for treatment Hep-G2, and MCF-7 cells line and COVID-19 coronavirus.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflict of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to chemistry department, Faculty of Women for Art, Science & Education, Ain Shams University for providing assistance with the chemicals used in this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abbas S.Y., Farag A.A., Ammar Y.A., Atrees A.A., Mohamed A.F., El-Henawy A.A. Synthesis, characterization, and antiviral activity of novel fluorinated isatin derivatives. Monatsh. Chem. 2013;144:1725–1733. doi: 10.1007/s00706-013-1034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla T.H., Nasr A.S., Bassioni G.h., Harding D.R.K., Kandile N.G. Fabrication of sustainable hydrogels-based chitosan Schiff base and their potential applications. Arab J. Chem. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed M.E., Mohamed H.M., Mohamed M.I., Kandile N.G. Sustainable antimicrobial modified chitosan and its nanoparticles hydrogels: Synthesis and characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;162:1388–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali M., Kandile N.G., Mohamed M.I., Taher A.T., Hassan H.M. Fabrication of modified chitosan with furanone derivatives and its nanocomposites: Synthesis, characterization and evaluation as anticancer agents, accepted for publication in Egypt. J. Chem. 2023 doi: 10.21608/EJCHEM.2023.186011.7432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz T., Rahim F., Ullah R., Ullah A., Haq F., Khan F.U., Kiran M., Khattak N.S., Iqbal M. Synthesis and biological evaluation of isatin based thiazole derivatives. Biomed. J. Sci. Tech. Res. 2020;28(5):21919–21925. doi: 10.26717/BJSTR.2020.28.004704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F., Chan K.H., Jiang Y., Kao R.Y.T., Lu H.T., Fan K.W., Cheng V.C.C., Tsui W.H.W., Hung I.F.N., Lee T.S.W., Guan Y., Peiris J.S.M., Yuen K.Y. In vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirkov S.N. The antiviral activity of chitosan (review) Prikl. Biokhim. Mikrobiol. 2002;38(1):5–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1013206517442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, N. K., Deepika, Choudhury, R., Sonawane, G. A., Mavinamar, S., Lyu, X., Pandey, R. P., 2021. Chang, C.-M., Nanoparticles as an effective drug delivery system in COVID-19, Biomed. Pharmacother. 143, 112162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Divar M., Khalafi-Nezhad A., Zomorodian K., Sabet R., Faghih Z., Jamali M., Pournaghz H., Khabnadideh S. Synthesis of Some Novel semicarbazone and thiosemicarbazone derivatives of isatin as possible biologically active agents. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2017;17(6):1–13. http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/20102 [Google Scholar]

- El Gizawy, H. A., Boshra, S. A., Mostafa, A., Mahmoud, S. H., Ismail, M. I., Alsfouk, A. A., Taher, A. T., Al-Karmalawy, A. A., 2021. Pimenta dioica (L.) merr. bioactive constituents exert anti-SARS-CoV-2 and anti-inflammatory activities: Molecular docking and dynamics, in vitro, and in Vivo studies, Molecu. 26, 5844. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules 26195844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- El Hamdaoui L., El Marouani M., El Bouchti M., Kifani-Sahban F., El Moussaouiti M. Thermal stability, kinetic degradation and lifetime prediction of chitosan Schiff bases derived from aromatic aldehydes. Chem. Selec. 2021;6:1–13. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348523770 [Google Scholar]

- Elzamly R.A., Mohamed H.M., Mohamed M.I., Zaky H.T., Harding D.R.K., Kandile N.G. New sustainable chemically modified chitosan derivatives for different applications: Synthesis and characterization. Arab. J. Chem. 2021;14 doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistova M., Geserick P., Leverkus M. Crystal violet assay for determining viability of cultured cells. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. 2016;343–347 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot087379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan P.G., Sam S.T., Abdullah M.F., Omar M.F., Tan W.K. Water resistance and biodegradation properties of conventionally-heated and microwave-cured cross-linked cellulose nanocrystal/chitosan composite films. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021;188 www.elsevier.com/locate/polymdegradstab [Google Scholar]

- Gomha S.M., Riyadh S.M., Mahmmoud E.A., Elaasser M.M. Synthesis and anticancer activities of thiazoles, 1,3-thiazines, and thiazolidine using chitosan-grafted-poly(vinylpyridine) as basic catalyst. Heterocyc. 2015;91(6):1227–1243. doi: 10.3987/COM-15-13210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horo H., Bhattacharyya S., Mandal B., Kundu L.M. Synthesis of functionalized silk-coated chitosan-gold nanoparticles and microparticles for target-directed delivery of antitumor agents. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;258 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim H.M., Mostafa M., Kandile N.G. Potential use of N-carboxyethylchitosan in biomedical applications: Preparation, characterization, biological properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;149:664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaber N., Al-Remawi M.A., Al-Akayleh F.A., Al-muhtaseb N.A., Al-Adham I.S., Collier P.J. A review of the antiviral activity of chitosan including patented application and its potential use against COVID-19. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022;1:41–58. doi: 10.1111/jam.15202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandile N.G., Zaky H.T., Mohamed M.I., Nasr A.S., Ali Y.G. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from shrimp shells, Open. J. Org. Polym. Mater. 2018;8:33–42. http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojopm [Google Scholar]

- Kandile N.G., Mohamed H.M., Nasr A.S. Novel hydrazinocurcumin derivative loaded chitosan, ZnO, and Au nanoparticles formulations for drug release and cell cytotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;158:1216–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandile N.G., Mohamed H.M. New chitosan derivatives inspired on heterocyclic anhydride of potential bioactive for medical applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;182:1543–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandile N.G., Mohamed M.I., Zaky H.T., Nasr A.S., Ali Y.G. Quinoline anhydride derivatives cross–linked chitosan hydrogels for potential use in biomedical and metal ions adsorption. Polym. Bull. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00289-021-03633-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasaai M., Arul J., Charlet G. Intrinsic viscosity–molecular weight relationship for chitosan. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2000;38:2591–2598. doi: 10.1002/1099-0488(20001001)38:19<2591::AID-POLB110>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavianina I., Plieger P.G., Cave N.J., Gopakumar G., Dunowasks M., Kandile N.G., Harding D.R.K. Design, and evaluation of a novel chitosan-based system for colon-specific drug delivery. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016;85:2539–3246. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavianinia, I., Plieger, P.G., Kandile, N. G. Harding D. R. K., 2014. In vitro evaluation of spraydried chitosan microspheres crosslinked with pyromellitic dianhydride for oral colon-specific delivery of protein drugs, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260412803.

- Kavianinia I., Plieger P.G., Kandile N.G., Harding D.R.K. Preparation and characterization of an amphoteric chitosan derivative employing trimellitic anhydride chloride and its potential for colon targeted drug delivery system. Mater. Today Commun. 2015;3:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.mtcomm.2015.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhang P., Li C., Guo Y., Sun K. In vitro/vivo antitumor study of modified-chitosan/carboxymethyl chitosan “boosted” charge-reversal nanoformulation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;269 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Kou Y., Zhang X., Dong W., Cheng H., Mao S. Enhanced oral insulin delivery via surface hydrophilic modification of chitosan copolymer based self-assembly polyelectrolyte nanocomplex. Int. J. Pharm. 2019;554:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J., Yuchen W., Lu R. Mechanism and application of chitosan and its derivatives in promoting permeation in transdermal drug delivery systems: A Review. Pharmaceu. 2022;15:459. doi: 10.3390/ph15040459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi Y., Chen Y., Gu G., Miao Q., Tan W., Li Q., Guo Z. New synthetic adriamycin-incorporated chitosan nanoparticles with enhanced antioxidant, antitumor activities, and pH-sensitive drug release. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021;273 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.118623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modak C., Jha A., Sharma N., Kumar A. Chitosan derivatives: A suggestive evaluation for novel inhibitor discovery against wild type and variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;187:492–512. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.07.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed M.I., Kandile N.G., Zaky H.T. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 1,3,4-oxadiazole-2(3H)-thione and azidomethanone derivatives based on quinoline4-carbohydrazide derivatives. J. Heterocyclic Chem. 2017;54(1):35–43. doi: 10.1002/jhet.2529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann, T., 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays, J. Immunol. Method. 65, 55-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4Get rights and content. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Of J. Research article of the essential oil of nepeta deflersiana schweinf growing in KSA. Int. Res. J. Pharm. 2016;7(6):29–33. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304994941 [Google Scholar]

- Packialakshmi P., Gobinath P., Ali D., Alarifi S., Alsaiari N.S., Idhayadhulla A., Surendrakumar R. Synthesis and characterization of a minophosphonate containing chitosan polymer derivatives: invstiation of cytotoxic activity and in silico study of SARS-CoV-19. Polym. 2021;7:1046. doi: 10.3390/polym13071046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packialakshmi P., Gobinath P., Ali D., Alarifi S., Gurusamy R., Idhayadhulla A., Surendrakumar R. New chitosan polymer scaffold Schiff bases as potential cytotoxic activity: synthesis, molecular docking, and physiochemical characterization. Front. Chem. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2021.796599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prateeksha, Sharma, V. K., Liu, X., Oyarzún, D. A., Abdel-Azeem, A. M., Atanasov, A. G. Hesham, A. El-L., Barik, S. K., Gupta, V. K., Singh, B. N., 2021. Microbial polysaccharides: An emerging family of natural biomaterials for cancer therapy and diagnostics, Semin. Cancer Biol. In press. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2021.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Priyadarshi G., Raval N.P., Trivedi M.H. Microwave-assisted synthesis of cross-linked chitosan-metal oxide nanocomposite for methyl orange dye removal from unary and complex effluent matrices. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022;219:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.07.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrć K., Milewska A., Duran E.B., Botwina P., Dabrowska A., Jedrysik M., Benedyk M., Lopes R., Arenas-Pinto A., Badr M., Mellor R., Kalber T.L., Fernandez-Reyes D., Schätzlein A.G., Uchegbu I.F. SARS–CoV–2 inhibition using a mucoadhesive, amphiphilic chitosan that may serve as an anti–viral nasal spray. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:20012. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99404-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju L., Lazuli A.R.S.C., Prakash N.K.U., Rajkumar E. Chitosan- terephthaldehyde hydrogels – effect of concentration of cross-linker on structural, swelling, thermal and antimicrobial properties. Materialia. 2021;16 doi: 10.1016/j.mtla.2021.101082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safarzadeh M., Sadeghi S., Azizi M., Rastegari-Pouyani M., Pouriran R., Hoseini M.H.M. Chitin and chitosan as tools to combat COVID-19: A triple approach. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;183:235–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N., Modak C., Singh P.K., Kumar R., Khatri D., Singh S.B. Underscoring the immense potential of chitosan in fighting a wide spectrum of viruses: a plausible molecule against SARS-CoV-2? Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021;179:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V., Batoo K.M., Singh M. Fabrication of chitosan–coated mixed spinel ferrite integrated with graphene oxide (GO) for magnetic extraction of viral RNA for potential detection of SARS–CoV–2. Mater. Sci. process. Appl. Phys. A. 2021;127:960. doi: 10.1007/s00339-021-05067-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A., Raghuwanshi K., Patel V.K., Jain D.K., Veerasamy R., Dixit A., Rajak H. Assessment of 5-substituted isatin as surface recognition group: Design, Synthesis, and Antiproliferative evaluation of hydroxamates as novel histone deacetylase inhibitors. Pharmaceu. Chem. J. 2017;51(5):366–374. doi: 10.1007/s11094-017-1616-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Zhao P., Liang X., Gong X., Song T., Niu R., Chang J. Folate-PEG coated cationic modified chitosan – cholesterol liposomes for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Biomater. 2010;31:4129–4138. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaboon M.H., Al-Lami H.S., Saleh A.A. Synthesis of polymeric chitosan derivative Nanoparticles and their MTT and flow cytometry evaluation against breast carcinoma cell. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2019;1279 doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1279/1/012070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]