Abstract

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) which is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis poses a significant public health global treat. Tuberculosis meningitis (TBM) accounts for approximately 1% of all active TB cases. The diagnosis of Tuberculosis meningitis is notably difficult due to its rapid onset, nonspecific symptoms, and the difficulty of detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In 2019, 78,200 adults died of TB meningitis. This study aimed to assess the microbiological diagnosis TB meningitis using CSF and estimated the risk of death from TBM.

Methods

Relevant electronic databases and gray literature sources were searched for studies that reported presumed TBM patients. The quality of included studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tools designed for prevalence studies. Data were summarized using Microsoft excel ver 16. The proportion of culture confirmed TBM, prevalence of drug resistance and risk of death were calculated using the random-effect model. Stata version 16.0 was used perform the statistical analysis. Moreover, subgroup analysis was conducted.

Results

After systematic searching and quality assessment, 31 studies were included in the final analysis. Ninety percent of the included studies were retrospective studies in design. The overall pooled estimates of CSF culture positive TBM was 29.72% (95% CI; 21.42–38.02). The pooled prevalence of MDR-TB among culture positive TBM cases was 5.19% (95% CI; 3.12–7.25). While, the proportion of INH mono-resistance was 9.37% (95% CI; 7.03–11.71). The pooled estimate of case fatality rate among confirmed TBM cases was 20.42% (95%CI; 14.81–26.03). Based on sub group analysis, the pooled case fatality rate among HIV positive and HIV negative TBM individuals was 53.39% (95%CI; 40.55–66.24) and 21.65% (95%CI;4.27–39.03) respectively.

Conclusion

Definite diagnosis of TBM still remains global treat. Microbiological confirmation of TBM is not always achievable. Early microbiological confirmation of TBM has great importance to reduce mortality. There was high rate of MDR-TB among confirmed TBM patients. All TB meningitis isolates should be cultured and drug susceptibility tested using standard techniques.

Introduction

Tuberculosis(TB) poses a significant public health global threat, which is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis(Mtb) bacteria. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2020, the number of people newly diagnosed with TB dropped to 5.8 million with 1.3 million TB deaths among HIV-negative people and an additional 214 000 among HIV-positive people [1]. Following a primary or post-primary pulmonary infection, Mycobacterium tuberculosis can attack any part of the body including the central nervous system. Tuberculosis meningitis(TBM) is the most common type of central nervous system TB. Some patients who have or have had tuberculosis may develop the rare complication known as tuberculous meningitis. Tuberculous meningitis accounts for approximately 1% of all cases of active tuberculosis [2].

Southeast Asia and Africa accounted for 70% of global TBM incidence. WHO estimated that 78,200 (95% UI; 52,300–104,000) adults died of TBM in 2019. Tuberculous Meningitis case fatality in those treated was on average 27% [3, 4]. Besides, TBM can cause a diverse clinical picture including altered mental status, meningitic features, seizures, cranial nerve palsies, and focal neurological deficits [5]. It is among severe diseases which account 5–10% of extra-pulmonary tuberculosis cases [2].

The disease involves the infection of the meninges of the host, which is caused by Mtb and other mycobacteria. Over half of TBM survivors have neurological disability [6]. Patients with TBM usually required admission to the intensive care unit. The most predisposed populations to develop TBM are children under four years, the elderly and HIV-positive patients [7]. The challenge TBM management concentrated on rapid reliable diagnosis andtreatment. Drug resistance and HIV infection increase the difficulty of TBM management [8].

Following TB infection infants have an up to 20% risk of developing TBM. Over half of all children with tuberculosis in the world go undiagnosed or unreported. Tuberculous meningitis mostly develops within 2–6 months following primary pulmonary infections during childhood [9]. To diagnose TBM in children MRI is superior to CT imaging but its high cost and need for infrastructure make difficult to use it [10]. In children, Most of the time TBM presents as subacute meningitis which makes it difficult to distinguishes from other meningoencephalitis diseases [11].

The diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis is notably difficult due to its rapid onset, nonspecific symptom, and the difficulty of detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [12]. The examination of the cerebrospinal fluid is the gold standard for diagnosing TBM. The identification of tuberculous bacilli in the CSF, either by smear examination or by culture, is required for a definitive diagnosis [13]. Even though culture is the gold standard for diagnosing Mycobacterium tuberculosis, long time for Mycobacterium growth on Mycobacterium growth indicator tube (MGIT) and LJ medium may lead to a delay in diagnosis [14].

Tuberculosis meningitis diagnosis is challenging by several factors, particularly in low- and middle-income countries: first, CSF collection necessitates lumbar puncture; second, CSF processing necessitates adequate laboratory capacity; and finally, available laboratory diagnosis methods (smear microscopy, molecular tests such as Xpert MTB/RIF, or CSF culture) have moderate sensitivity [15]. A lumbar puncture is performed by a doctor who is specially trained to collect CSF. In a diagnostic Lumbar Puncture, standard bedside aseptic procedures apply with no-touch technique [15]. At this time there were obstacles in the diagnosis of TBM due to the absence of quick, reliable and affordable diagnostic tests. This study aims to assess the microbiological diagnosis of TBM using CSF and to estimate case fatality rate from TBM.

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis was registered on the PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews), University of York. It was assigned a registration number CRD42022323629.

Literature search

Systematic literature searching was performed using the PubMed, EMBASE databases and gray literature to assess microbiological diagnosis and mortality of Tuberculosis meningitis. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist [16] was used to conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis (S1 Table). There was no need for ethical approval because this study was based on previously published primary investigations. The following key terms were used to extract the intended data: Tuberculosis, meningitis, Tuberculous meningitis, diagnosis, microbiological diagnosis bacteriologically confirmed, mortality, fatality, death and TB culture.

The search terms and their variations were used in combination. The Boolean operators AND and OR were used accordingly. Articles were limited to papers published in the English language without a limit of a published year. The final search included studies published up to May 1, 2022.

Selection criteria

Included studies were: (1) original study on TBM presumptive patients; (2) published in the English language without regard to a publication year; 3). having described microbiological diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis based on CSF Mycobacteriological culture result data. Additionally, included articles should be peer-reviewed, fulfilled the above listed inclusion criteria and adequately addresses the objective of the study. Studies with incomplete data, studies not used culture technique to diagnose TBM, and review articles, meta-analyses and duplicates were all excluded from the study. Two authors (GS and AA) search and selected articles based on their title and abstract. Additionally, they did independent screening of the full text of the retrieved article to be included in the final analysis.

Data extraction

To collect pertinent data from each eligible study, a pre-designed Microsoft 2010 excel data extraction form was used. The extraction activity was carried out by two writers (GS and BD). The quality and completeness of the extracted data were also reviewed by the third Author (DF). The following information was extracted: initial author name; year of publication; country of study, study period, age of study participants; study design, sample size of participants, case fatality rate, MDR-TB prevalence, and INH mono-resistance prevalence.

Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal (JBI) techniques for prevalence studies were used to assess the quality of eligible papers [17]. There are nine quality indicators on the JBI checklist for the prevalence study. These quality indicators were converted to 100%, and the quality score was assessed as high if >80%, medium if 60–80%, and low if <60%. Two authors (GS and BD) carried out the quality assessment, while the third author handled the disagreement between the two authors (AA).

Data analysis

Data were summarized and saved in Microsoft Excel 2016 before being exported to STATA Version 16.0 for analysis. All studies were pooled to estimate the risk of death of Tuberculosis meningitis presumptive patients at any age. Subgroup analysis was done based on the age of study participants (children or adult), HIV status and study design. Heterogeneity among studies was examined using forest plots and I2 heterogeneity tests. In the current review, I2>50% a random effect model was used for analysis. Funnel plot and an Egger’s test (p-value 0.1 as a significant level) to see if there was any potential for publication bias. The forest plot provides a visual inspection of the confidence intervals of effect sizes of individual studies. The presence of non-overlapping intervals suggests heterogeneity.

Result

Eligible studies

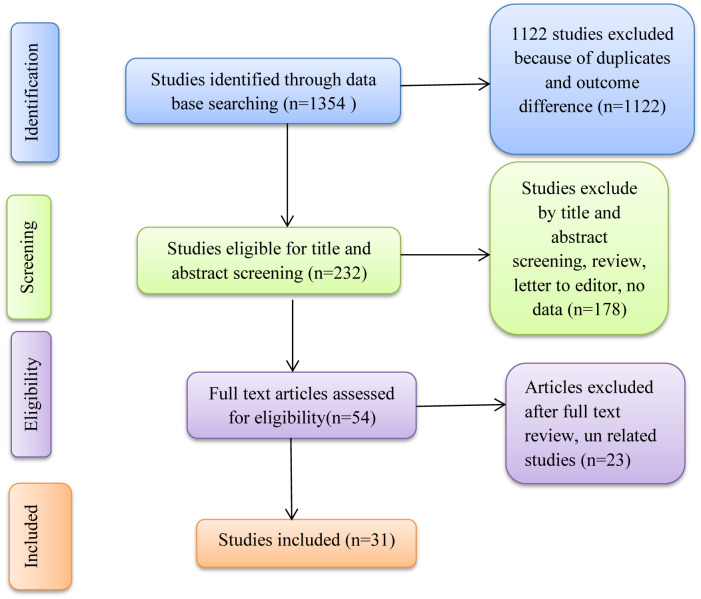

Using the study’s search terms, 1354 studies were found through a systematic search of electronic databases. After removing 1122 duplicate research, titles and abstracts were used to screen 232 publications. 174 studies were removed from the full-text review based on the abstract and title review. Only 31 [18–48] papers were included in the final systematic review and meta-analysis after full-text review of 54 studies (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Flow diagram of systematic search of studies for this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

There were 14 studies from Asia, eight from Europe, five from America, and only four [20, 26, 27, 36] studies from Africa (3 in South Africa and one in Uganda). Ninety percent of the included studies were retrospective studies in design. The study period of the studies was from 1985 to 2020. The range of sample sizes was 20 [23] to 6762 [36] study participants. Five studies [18, 20, 25, 27, 32] were conducted on children under the age of 18 and seven studies were conducted on adults over the age of 18. The rest studies included all study participants without discrimination on age. The total study participants of the included studies were 20,596 (Table 1).

Table 1. Study characteristic of included studies.

| Author_year | Country | Study period | Study design | Participant age | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali, et al. 2015 [18] | Diyarbakir Turkey | 1998 to 2008 | Retrospective | <18 | 185 TBM |

| Anne-Sophie, et al. 2011 [19] | Denmark | January 2000 to December 2008 | Retrospective | All age | 50 TBM |

| Anu, et al. 2018 [20] | S/Africa | 2010–2014 | Retrospective | 3 months-15 years | 865 TBM |

| Baobao, et al. 2021 [21] | Shandong, China | January 2008 to April 2018. | Retrospective | >18 | 80 TBM |

| Chia, et al. 2017 [22] | Kebangsaan Malaysia | January 2003 to February 2015 | Observational | >18 | 61 TBM |

| Christiene, et al. 2002 [23] | Denmark | 1988 to July 2000. | Retrospective | All age | 20 TBM |

| Cíntia Helena, et al. 2014 [24] | Brazil | 2001 to 2010 | Descriptive | All age | 116 TBM |

| Dong-Mei, et al. 2020 [25] | Southwest of China | January 2013 to December 2018 | Retrospective | < 14 years old | 319 TBM |

| Fiona, et al. 2020 [26] | Uganda | Nov 25, 2016, to Jan 24, 2019 | Retrospective | >18 | 204TBM |

| Gijs, et al. 2009 [27] | South Africa | January 1985 to April 2005 | Retrospective | <18 | 554TBM |

| Heng, et al. 2016 [28] | Sabah, Malaysia | February 2012 to March 2013 | cohort | >12 | 84 TBM |

| Hosoglu, et al. 2003 [29] | Turkey | 1985 to 1998 | Retrospective | >18 | 469TBM |

| Jaime, et al. 2019 [30] | Peru | 2006 to 2015 | Retrospective | >18 | 263TBM |

| Renu, et al. 2017 [31] | India | July 2012 to July 2015 | Prospective | All age | 197 TBM |

| Robindra, et al. 2020 [32] | Europe | February 2016 to August 2016 | Retrospective | 0–16 years | 118 TBM |

| Yahia, et al. 2014 [33] | Qatar | January 2006 to December 2012 | Retrospective | >18 | 80 TBM |

| Christopher, et al. 2010 [34] | USA | 1 January 1993 to 31 December 2005 | Retrospective | All age | 1896TBM |

| Krishnapriya, et al. 2020 [35] | South India | August 2018 to February 2020 | Observational | 293 TBM | |

| Patel, et al. 2004 [36] | S/Africa | 1999 through 2002 | Retrospective | All age | 6762TBM |

| Ting, et al. 2016 [37] | Shaanxi, China | September 2010 to December 2012 | Retrospective | All age | 350 TBM |

| Jingya, et al. 2016 [38] | southwest China | - | - | 11 to 84 | 401 TBM |

| Kavitha, et al. 2016 [39] | India | May 2013 –April 2014 | Prospective | 3 months to 70 years | 698 TBM |

| Duc T, et al. 2019 [40] | America | 01/2010 to 12/2017 | Retrospective | All age | 192 TBM |

| Egidia, et al. 2015 [41] | Romania | 2004 to 2013 | Retrospective | All age | 204 TBM |

| Erdem, et al. 2013 [42] | Multi-country | 2000 to 2012. | Retrospective | All age | 506 TBM |

| Filiz, et al. 2011 [43] | Turkey | 1998 to 2009 | Retrospective | >14 | 160 TBM |

| Jyothi, et al. 2017 [44] | India | 2009 to 2014 | Retrospective | All age | 790 TBM |

| Lidya, et al. 2018 [45] | Indonesia | 2006 to 2016 | Cohort | >18 | 1180 TBM |

| Miguel, et al. 2020 [46] | Mexico | January 2015 to March2018 | Retrospective | ≥18 | 41 TBM |

| Nguyen, et al. 2014 [47] | Vietnam | 17 April 2011 to 31 December 2012 | Retrospective | >18 | 379 TBM |

| Syed, et al. 2017 [48] | India | 2013 to 2015 | - | >18 | 267 TBM |

Quality assessments of the included studies are provided in the (S2 Table). Ten studies [19, 21, 22, 23, 28, 30, 33, 34, 38, 47] score medium quality based on JBI quality assessment checklist for prevalence studies. While most of the studies score high quality using JBI checklist for prevalence studies.

Microbiological diagnosis

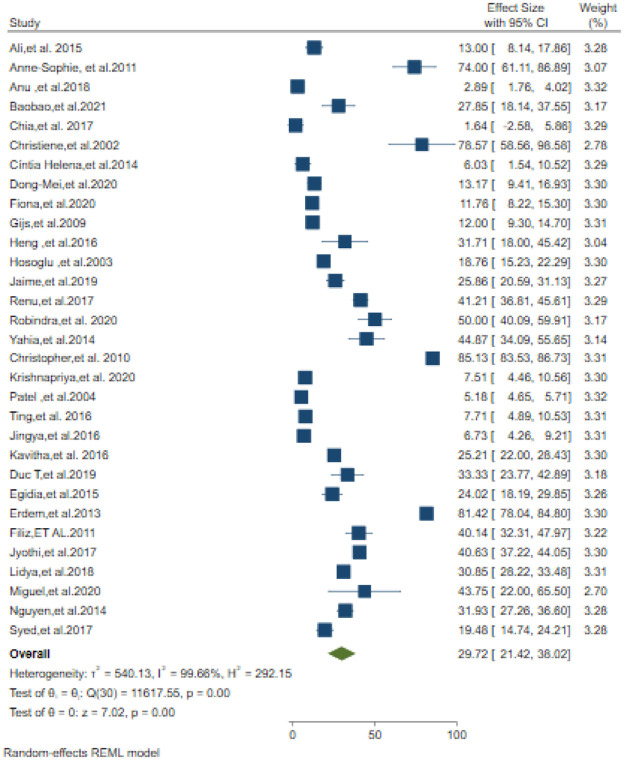

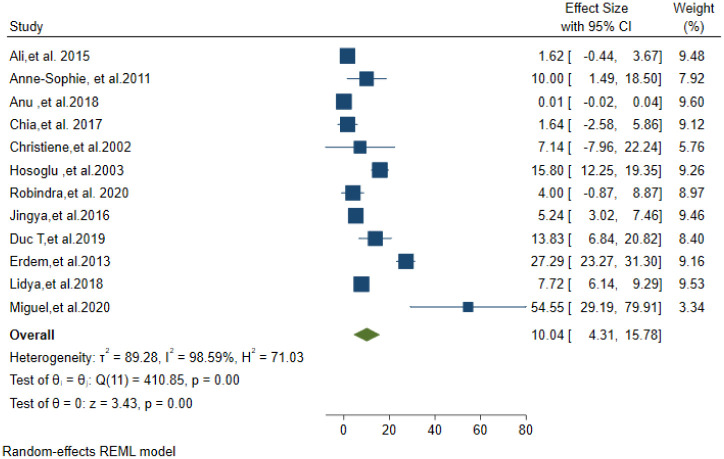

The overall pooled estimate of Tuberculosis meningitis confirmed by CSF culture was 29.72% (95% CI; 21.42–38.02). The lowest percentage of TBM confirmed by CSF culture was 1.64% [22] and the highest percentage was 85.13% [34] (Fig 2). Prevalence of definite TBM diagnosed by AFB microscopy was 10.04% (95% CI; 4.31–15.78) (Fig 3).

Fig 2. CSF Culture confirmed Tuberculosis meningitis among suspected patients.

Fig 3. ZN AFB microscopy positivity of CSF in TBM suspected patients.

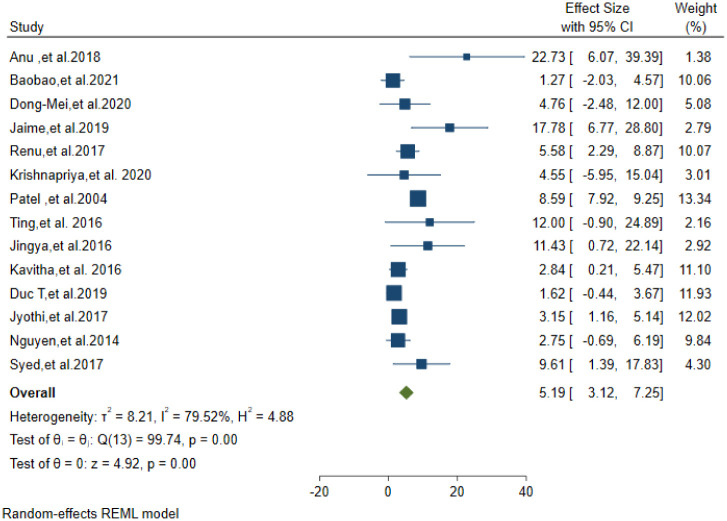

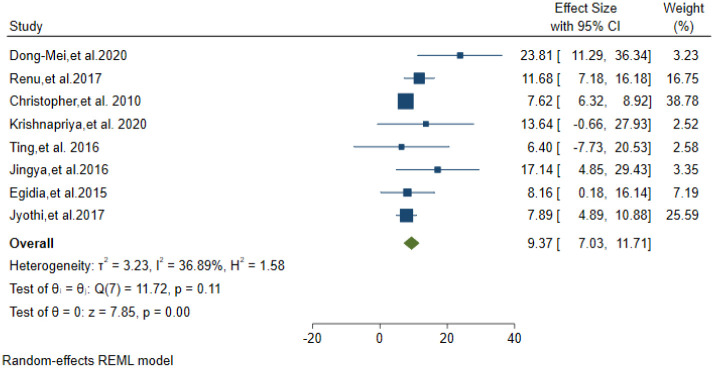

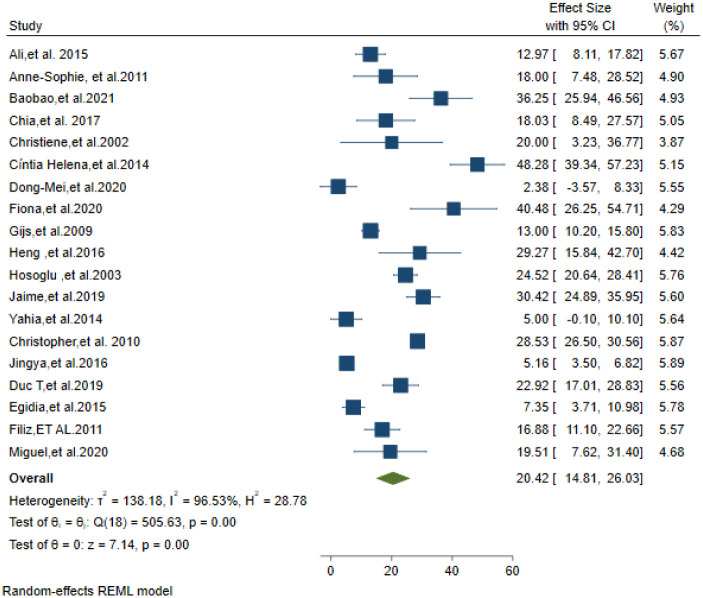

Only fourteen studies reported the drug resistance pattern of the CSF culture-positive isolates. A total of 2736 CSF Mycobacterium TB culture-positive isolates were tested for drug susceptibility. Fourteen studies(5 from india,4 from china,2 from south Africa,1 from America,1 from Peru and 1 from Vietnam) were included to analyses the drug resistance pattern. MDR-TBM was found in 5.19% of these isolates (95% CI: 3.12–7.25) (Fig 4). Eight studies reported the proportion of INH mono resistance from the above total isolates. INH mono-resistance was 9.37% (95% CI; 7.03–11.71) (Fig 5).

Fig 4. Pooled estimate of MDR-TB prevalence in Tuberculosis confirmed isolates.

Fig 5. Prevalence of INH mono resistance in Tuberculosis meningitis confirmed isolates.

Case fatality rate among TBM patients

The proportion of TBM patients who died was reported in twenty-one studies. There were 1250 deaths out of a total of 6896 TBM patients. The estimated case fatality rate in TBM patients was 20.42% (95%CI; 14.81–26.03) (Fig 6).

Fig 6. Mortality among Tuberculosis meningitis suspected patients.

Sub-group analysis of case fatality among TBM patients

A subgroup analysis of case fatality rates by age, study design type, and HIV status yields estimates of 9.80% (95% CI;3.22–16.37) in children under the age of 18 and 24.82% (95%CI;17.05–32.59) in adults (greater than or equal to 18 years old); 20.34% (95% CI;14.03–26.65) and 30.92% (95% CI;18.40–43.44) in retrospective and other study designs, respectively; 53.39 (95%CI;40.55–66.24) in HIV positive TBM patients and 21.65 (95%CI;4.27–39.03) among HIV negative TBM patients (Table 2).

Table 2. Sub group analysis of mortality.

| Characteristic | Number of studies | Number of deaths | Proportion of death (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| <18 years | 3 | 95 | 9.80 (3.22–16.37) |

| ≥18 years | 7 | 277 | 24.82 (17.05–32.59) |

| Study type | |||

| Retrospective | 17 | 1076 | 20.34 (14.03–26.65) |

| other study design | 4 | 160 | 30.92(18.40–43.44) |

| HIV status | |||

| Positive* | 4 | 220 | 53.39 (40.55–66.24) |

| Negative* | 4 | 173 | 21.65 (4.27–39.03) |

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis the microbiological diagnosis of Tuberculosis meningitis and the risk of death among patients were calculated. According to the data around one–third of TBM patients had CSF microbiological (TB culture and AFB microscopy) confirmed illness. MDR-TB was shownto be prevalent in TBM patients. The risk of death was significant among TB meningitis patients. As per the findings, one patient will die for every five TBM cases.

The culture confirmed diagnostic rate reported in this study (29.72%) was slightly near to the report (38.9%) of a previous study [49]. It implies that 75% of TBM patients received anti-TB treatment empirically. This finding was also in support with the reports of previous study which stated as in more than 50 per cent TBM patients, microbiological confirmation is not achieved This data indicated that conventional microbiological diagnosis of TBM tests has suboptimal positivity from CSF samples. Due to constrain of infrastructure and trained personnel, Worldwide there was a difficulty in diagnosing TBM using CSF. Junior doctors possess uncertainties regarding performing the procedure and frequently perform below expectations [50]. Lumbar puncture (LP) is often not performed in sub-Saharan African and other resource-limited settings [51]. Culture for M. tuberculosis performed on CSF had even lower positivity, producing a positive result in only approximately one in three cases [52].

Besides its longer turnaround time and inaccessibity, the lower positivity rate of CSF culture makes doubt its use as a gold standard diagnosis method for TBM. The positive rate of detection for the smear and culture tests is low alerting the globe to invest in rapid accurate and accessible diagnostic methods. Paucibacillarity of TBM makes it difficult to isolate Mtb in CSF by conventional culture methods. Even though rapid, sensitive and highly specific molecular detection methods have been favored, their cost and accessibility make early diagnosis of TBM difficult [53].

The lower positivity of CSF for Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on AF smear microscopy found in this meta-analysis was similar to other studies report which describe staining of CSF smears for acid-fast bacilli has poor sensitivity (about 10% to 15%) [54]. However, smear microscopy is the most widely used rapid and inexpensive diagnostic test for TB, especially in low and middle-income countries. Based on this most TBM cases were not microbiologically confirmed.

This systematic review and meta-analysis study has shown that drug resistance in TBM is not an unusual occasion. The rate of MDR-TB and INH mono resistance was 5.19% and 9.37% respectively. Since most of the included studies to analyze drug resistance pattern were from Asia (5 from India, 4 from china and 1 from Vietnam), the result reflects drug resistance pattern in that specific region. This indicates that TBM has a high vulnerability to drug resistance. Thus with the difficulties of getting precious CFS samples from TBM presumptive patients countries must include microbiological diagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in their national strategic plan and algorithm.

According to the findings, 20.03% of TBM patients died during the course of their illness. It was alligned with the study finding of another study [55]. Our sub-group analysis showed that the risk of death was higher among adults (≥18 years) and HIV positive than their respective children (<18 years old) and HIV negative patients. Majority of the included studies were done after the initiation of antiretroviral treatment in most of developed and developing countries. The different case fatality rate reported in this study among children and adults was different from the reports of a previous single study [41] which found a similar 7.03% case fatality rate in both groups. This finding (mortality rate among children 9.8%) is lower than the report of previous systematic review and meta-analysis [56]. which reported 19.3% mortality rate among children. It might be due to the previous study participants were HIV–infected children. Among adults, our study finding was consistent with the previous studies [49, 55].

According to this study, HIV-TBM co-infected individuals have a two-fold greater case fatality rate than HIV-negative patients; mortality in HIV-negative TBM patients was 21.65%, compared to 53.39 percent in HIV-positive TBM patients. A prior study [49] found a mortality rate of 53.4 percent among adult HIV-positive TBM patients, which was similar to this. The HIV-infected person is at higher risk of developing disseminated extrapulmonary tuberculosis including TBM, particularly at a stage of more advanced immunosuppression [56]. It has been reported that tuberculosis patients co-infected with HIV were more likely to have poor treatment outcomes and death [57, 58].

There was a lot of heterogeneity between studies. We were able to find subgroup analysis based on the features of the included research, but we still don’t know what caused the heterogeneity. Although we were unable to pinpoint the source of heterogeneity, the following factors could contribute to publication bias and heterogeneity: 1). We only considered research that was published in English; 2).the smallest sample size of the included studies was 20; and 3).the majority of the studies were retrospective.

Our study has some limitations: First, in this meta-analysis, we only included studies published in English. Second, we are unable to analyze case fatality by anti-retroviral therapy use and CD4 count due to a lack of sufficient data. Third, since, there was high heterogeneity of studies interpretation of results need attention.

Conclusion

Tuberculosis meningitis cannot always be confirmed microbiologically. There was high rate of mortality in tuberculosis meningitis patients. The importance of early microbiological confirmation of TBM in reducing mortality is enormous. TBM patients have a high prevalence of MDR-TB infection. Tuberculous meningitis should be diagnosed using rapid, sensitive, and specific molecular testing methods. All TB meningitis isolates should be cultured and drug susceptibility tested using standard techniques. To investigate this goal in greater depth, prospective studies with a bigger sample size were required.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

Our great acknowledge goes to the author of primary studies included in this systematic review and meta-analyses.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

References

- 1.Global tuberculosis report 2021. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO

- 2.Thwaites G, Fisher M, Hemingway C, et al. British Infection Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. J Infect. 2009;59(3):167–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dodd PJ, Osman M, Cresswell FV, Stadelman AM, Lan NH, Thuong NTT, et al. The global burden of tuberculous meningitis in adults: A modelling study. PLOS Glob Public Health 2021;1(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantier M, Morisot A, Guérot E, et al. Functional outcomes in adults with tuberculous meningitis admitted to the ICU: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):1–8.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2013; 12: 999–1010. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70168-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiang S., Khan F, Milstein M, Tolman A.W, Benedetti A., Starke J.R, et al. Treatment outcomes of childhood tuberculous meningitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 947–957. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70852-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cano-Portero R, Amillategui-dos Santos R, Boix-Martínez R, Larrauri-Cámara A. Epidemiology of tuberculosis in Spain. Results obtained by the National Epidemiological Surveillance Network in 2015. Enferm Infect Microbiol Clin 2018;36(3):179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faksri K., Prammananan T., Leechawengwongs M., Chaiprasert A. Molecular Epidemiology and Drug Resistance of Tuberculous Meningitis. In: Wireko-Brobby G., editor. Meningitis [Internet]. London: IntechOpen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alarcon F, Escalante L, Perez Y, Banda H, Chacon G, Duenas G. Tuberculous meningitis. Short course of chemotherapy. Arch Neurol. 1990;47(12):1313–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530120057010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huynh J, Abo Y.-N, du Preez K, Solomons R, Dooley K.E, Seddon J.A. Tuberculous Meningitis in Children: Reducing the Burden of Death and Disability. Pathogens 2022, 11, 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mezochow A, Thakur K, Vinnard C. Tuberculous meningitis in children and adults: new insights for an ancient foe. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017. doi: 10.1007/s11910-017-0796-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett JE. Chronic meningitis. In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Vol 1. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders; 2015:1138–43; ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3

- 13.Ducomble T, Tolksdorf K, Karagiannis I, Hauer B, Brodhun B, Haas W, et al. The burden of extrapulmonary and meningitis tuberculosis: an investigation of national surveillance data, Germany, 2002 to 2009. Euro Surveill 2013; 18:. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Well GT, Paes BF, Terwee CB, Springer P, Roord JJ, Donald PR, et al. Twenty years of pediatric tuberculous meningitis: a retrospective cohort study in the western cape of South Africa. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1). doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bahr NC, Meintjes G, Boulware DR. Inadequate diagnostics: the case to move beyond the bacilli for detection of meningitis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol. 2019; 68: 755–760 doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Güneş A, Uluca Ü, Aktar F, Konca Ç, Şen V, Ece A, et al. Clinical, radiological and laboratory findings in 185 children with tuberculous meningitis at a single centre and relationship with the stage of the disease. Ital J Pediatr. 2015. Oct 15;41:75. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0186-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christensen, Andersen Å, Thomsen V.Ø., Andersen PH, Johansen IS. Tuberculous meningitis in Denmark: a review of 50 cases. BMC Infect Dis 11, 47 (2011). doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goenka A, Jeena PM, Mlisana K, Solomon T, Spicer K, Stephenson R, et al. Rapid Accurate Identification of Tuberculous Meningitis Among South African Children Using a Novel Clinical Decision Tool. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018. Mar;37(3):229–234. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng B., Fei X., Sun Y., Zhang X, Shang D, Zhou Y, et al. Prognostic factors of adult tuberculous meningitis in intensive care unit: a single-center retrospective study in East China. BMC Neurol 21, 308 (2021). doi: 10.1186/s12883-021-02340-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kee CP, Periyasamy P, Law ZK, Ibrahim NM, WanYahya WNN, Mahadzir H, et al. Features and Prognostic Factors of Tuberculous Meningitis in a Tertiary Hospital in Malaysia. J Infect Dis Epidemiol. 2017;3:028. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bidstrup C, Andersen PH, Skinhøj P, Andersen ÅB. Tuberculous meningitis in a country with a low incidence of tuberculosis: still a serious disease and a diagnostic challenge. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;34(11):811–4. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000026938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Souza Cíntia Helena, Yamane Ayaka, Pandini Jeison Cleiton, Ceretta Luciane Bisognin, Ferraz Fabiane, da Luz Glauco Duarte, et al. Incidence of tuberculous meningitis in the State of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 47(4):483–489, Jul-Aug, 2014. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0122-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang DM., Li QF., Zhu M. Wu GH, Li X, Xu YH, et al. Epidemiological, clinical characteristics and drug resistance situation of culture-confirmed children TBM in southwest of China: a 6-year retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 20, 318 (2020). doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05041-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cresswell FV, Tugume L, Bahr NC, Kwizera R, Bangdiwala AS, Musubire AK, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for the diagnosis of HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis: a prospective validation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020. Mar;20(3):308–317. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30550-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gijs T. J. van Well, Paes Berbe F., Terwee Caroline B., Springer Priscilla, Roord John J, et al. Twenty Years of Pediatric Tuberculous Meningitis: A Retrospective Cohort Study in the Western Cape of South Africa. Pediatrics Volume 123, Number 1, January 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee H.G., William T., Menon J. et al. Tuberculous meningitis is a major cause of mortality and morbidity in adults with central nervous system infections in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis 16, 296 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoşoğlu S, Geyik MF, Balik I, Aygen B, Erol S, Aygencel SG, et al. Tuberculous meningitis in adults in Turkey: epidemiology, diagnosis, clinic and laboratory. Eur J Epidemiol. 2003;18(4):337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soria J, Metcalf T, Mori N, Newby RE, Montano SM, Huaroto L, et al. Mortality in hospitalized patients with tuberculous meningitis. BMC Infect Dis. 2019. Jan 5;19(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3633-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta R, Thakur R, Kushwaha S, Jalan N, Rawat P, Gupta P, et al. Isoniazid and rifampicin heteroresistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolated from tuberculous meningitis patients in India. Indian J Tuberc. 2018. Jan;65(1):52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2017.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Basu Roy R, Thee S, Blázquez-Gamero D, Falcón-Neyra L, Neth O, Noguera-Julian A, et al. Performance of immune-based and microbiological tests in children with tuberculosis meningitis in Europe: a multicentre Paediatric Tuberculosis Network European Trials Group (ptbnet) study. Eur Respir J 2020; 56: 1902004 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02004-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imam YZ, Ahmedullah HS, Akhtar N, Chacko KC, Kamran S, Al Alousi F, et al. Adult tuberculous meningitis in Qatar: a descriptive retrospective study from its referral center. Eur Neurol. 2015;73(1–2):90–7. doi: 10.1159/000368894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vinnard C, Winston CA, Wileyto EP, Macgregor RR, Bisson GP. Isoniazid resistance and death in patients with tuberculous meningitis: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2010. Sep 6;341:c4451. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krishnakumariamma K, Ellappan K, Muthuraj M, Tamilarasu K, Kumar SV, Joseph NM. Molecular diagnosis, genetic diversity and drug sensitivity patterns of Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains isolated from tuberculous meningitis patients at a tertiary care hospital in South India. PLoS One. 2020. Oct 5;15(10):e0240257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patel VB, Padayatchi N, Bhigjee AI, Allen J, Bhagwan B, Moodley AA, et al. Multidrug-resistant tuberculous meningitis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2004. Mar 15;38(6):851–6. doi: 10.1086/381973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang T., Feng GD., Pang Y., Liu JY, Zhou Y, Yang YN, et al. High rate of drug resistance among tuberculous meningitis cases in Shaanxi province, China. Sci Rep 6, 25251 (2016). doi: 10.1038/srep25251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J, Hu X, Hu X, Ye Y, Shang M, An Y, et al. Clinical features, Outcomes and Molecular Profiles of Drug Resistance in Tuberculous Meningitis in non-HIV Patients. Sci Rep. 2016. Jan 7;6:19072. doi: 10.1038/srep19072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar K, Giribhattanavar P, Chandrashekar N, Patil S. Correlation of clinical, laboratory and drug susceptibility profiles in 176 patients with culture positive TBM in a tertiary neurocare centre. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016. Dec;86(4):372–376. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.09.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nguyen DT, Agarwal S, Graviss EA. Trends of tuberculosis meningitis and associated mortality in Texas, 2010–2017, a large population based analysis. PLoS ONE 2019;14(2): e0212729 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miftode EG, Dorneanu OS, Leca DA, Juganariu G, Teodor A, Hurmuzache M, et al. Tuberculous Meningitis in Children and Adults: A 10- Year Retrospective Comparative Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7): e0133477 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erdem H, Ozturk-Engin D, Elaldi N, Gulsun S, Sengoz G, Crisan A, et al. The microbiological diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: results of Haydarpasa-1 study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014. Oct;20(10):O600–8. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pehlivanoglu F, Yasar KK, Sengoz G. Tuberculous meningitis in adults: a review of 160 cases. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:169028. doi: 10.1100/2012/169028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaviyil JE, Ravikumar R. Diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: Current scenario from a Tertiary Neurocare Centre in India. Indian J Tuberc. (2017) doi: 10.1016/j.ijtb.2017.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaidir L, Annisa J, Dian S, Parwati I, Alisjahbana A, Purnama F, et al. Microbiological diagnosis of adult tuberculous meningitis in a ten-year cohort in Indonesia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018. May;91(1):42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2018.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.García-Grimshaw M, Gutiérrez-Manjarrez FA, Navarro-Álvarez S, González-Duarte A. Clinical, Imaging, and Laboratory Characteristics of Adult Mexican Patients with Tuberculous Meningitis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020. Mar;10(1):59–64. doi: 10.2991/jegh.k.191023.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nhu NT, Heemskerk D, Thu do DA, Chau TT, Mai NT, Nghia HD, et al. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2014. Jan;52(1):226–33. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01834-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rufai SB, Singh A, Singh J, Kumar P, Sankar MM, Singh S. Diagnostic usefulness of Xpert MTB/RIF assay for detection of tuberculous meningitis using cerebrospinal fluid. J Infect. 2017. Aug;75(2):125–131. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Ming-Gui, Luo Lan, Zhang Yunxia, Liu Xiangming, Liu Lin and He Jian-Qing. Treatment outcomes of tuberculous meningitis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulmonary Medicine (2019) 19:200. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0966-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henriksen MJV, Wienecke T, Thagesen H, Jacobsen RVB, Subhi Y, Ringsted C, et al. Assessment of Residents Readiness to Perform Lumbar Puncture: A Validation Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2017. Jun;32(6):610–618. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3981-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Siddiqi OK, Birbeck GL, Ghebremichael M, Mubanga E, Love S, Buback C, et al. Prospective Cohort Study on Performance of Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Xpert MTB/RIF, CSF Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) Lateral Flow Assay (LFA), and Urine LAM LFA for Diagnosis of Tuberculous Meningitis in Zambia. J Clin Microbiol. 2019. Jul 26;57(8):e00652–19. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00652-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garg RK. Microbiological diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: Phenotype to genotype. Indian J Med Res. 2019. Nov;150(5):448–457 doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1145_19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marais S, Thwaites G, Schoeman JF, Toeroek ME, Misra UK, Prasad K, et al. Tuberculous meningitis: a uniform case definition for use in clinical research. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(11):803–12 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70138-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bahr NC, Meintjes G, Boulware DR. 2019. Inadequate diagnostics: the case to move beyond the bacilli for detection of meningitis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Med Microbiol 68:755–760. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stadelman AM, Ellis J, Samuels THA, Mutengesa E, Dobbin J, Ssebambulidde K, et al. Treatment Outcomes in Adult Tuberculous Meningitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020. Jun 30;7(8):ofaa257. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vinnard C, Macgregor RR. Tuberculous meningitis in HIV-infected individuals. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2009. Aug;6(3):139–45) doi: 10.1007/s11904-009-0019-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tavares AM, Fronteira I, Couto I, Machado D, Viveiros M, Abecasis AB, et al. HIV and tuberculosis co-infection among migrants in Europe: a systematic review on the prevalence, incidence and mortality. PLoS One. 2017;12(9): e0185526. 35. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gupta RK, Lucas SB, Fielding KL, Lawn SD. Prevalence of tuberculosis in post-mortem studies of HIV-infected adults and children in resource-limited settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2015;29(15):1987–2002. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]