This Letter to the Editor refers to ‘EHRA expert consensus statement on arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse and mitral annular disjunction complex in collaboration with the ESC Council on valvular heart disease and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and by the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society’, by A. Sabbag et al., https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euac125.

A link between mitral valve prolapse (MVP) and malignant ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) has been reported. The recently published consensus statement summarized current literature and provided practical suggestions for risk stratification and management of patients with arrhythmic MVP.1

The mechanism of VAs in MVP, although not well explained, may be linked to anatomical substrates as areas of patchy myocardial fibrosis in the sub-valvular apparatus, triggered activity due to mechanical stretch of papillary muscles that leads to stretch-activated early afterdepolarizations and abnormal repolarization as a result of endocardial and mid-myocardial fibrotic changes on the papillary muscles and adjacent left ventricle.1 Despite the common fibrosis close to the mitral annulus, detected using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, the findings of a recent systematic review may imply that the main mechanism of ventricular arrhythmias leading to sudden cardiac death (SCD) is non-reentrant.2 In this way, the committee does not endorse the routine use of electrophysiological study with programmed ventricular stimulation for risk stratification.

Integrative grading of mitral valve regurgitation (MR) severity is also essential for evaluating the risk of VAs, as several studies have demonstrated that patients with severe degenerative MR carry an increased risk of SCD. Mitral valve surgery, through suppressing the progression of MVP, may have a role in preventing SCD by reducing VA burden. However, data are inconsistent and mainly derived from case series and thus, the surgical approach of MVP is not proposed in patients with high-risk VAs without severe MR.1,3,4

On this point, we should mention that not only VA reduction but also new-onset VAs have been described after corrective valve surgery, including mitral valve repair.5 Importantly, most clinically significant VAs in this setting have been revealed to be due to scar-related reentry as they are inducible with programmed stimulation.5 These arrhythmias present a similar ECG morphology that is compatible with papillary muscle or mitral annular/left ventricular basal origin impeding distinction of the underlying mechanism (Figure 1). R/S ratio and QRS duration are reliable predictors for differentiating papillary muscle VAs from fascicular arrhythmias that can also occur after valve surgery.5 However, previously undetected arrhythmic MVP VAs of non-reentrant mechanism cannot be excluded. Interestingly, these arrhythmias can occur even years after surgery. Therefore, they could also be related to a degenerative process of MVP.

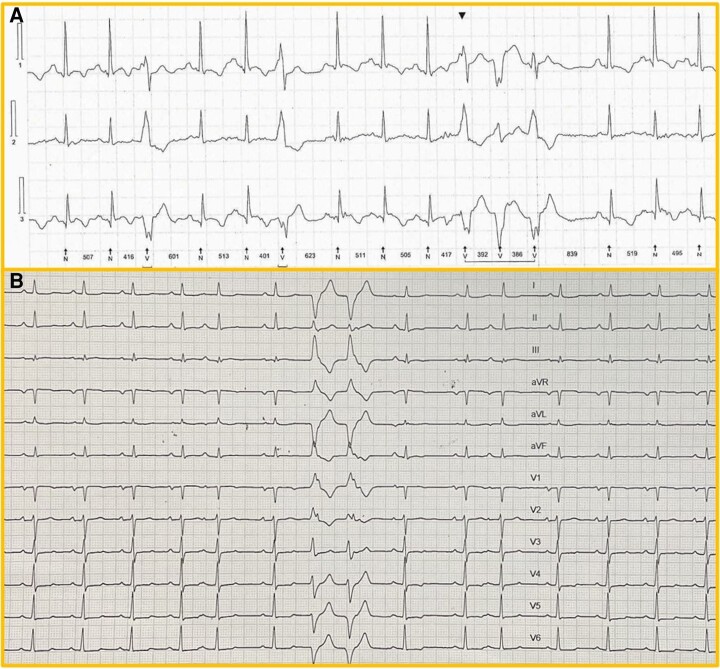

Figure 1.

New-onset ventricular arrhythmias in a 23-year-old female patient early after surgical valve repair for mitral valve prolapse with severe mitral regurgitation A. 24 h Holter monitoring showing a high burden of new-onset ventricular ectopy and non-sustained ventricular tachycardias. B. 12-lead ECG with a couplet of premature ventricular extrasystoles showing a right bundle branch block pattern with a late R/S transition in V4 precordial lead, likely originating from the anterolateral papillary muscle.

Taking into consideration the abovementioned characteristics of post-surgery VAs, we suggest that a distinct algorithm may be applied for the approach of new-onset (or presumably new-onset) VAs after surgery for MVP. Although validation from specifically designed studies is warranted, the role of electrophysiological study may be more crucial for the evaluation of these arrhythmias.

Contributor Information

K Tampakis, Department of Electrophysiology & Pacing, Henry Dunant Hospital Center, 107, Mesogion Ave, 115 26 Athens, Greece.

K Polytarchou, Department of Electrophysiology & Pacing, Henry Dunant Hospital Center, 107, Mesogion Ave, 115 26 Athens, Greece.

G Andrikopoulos, Department of Electrophysiology & Pacing, Henry Dunant Hospital Center, 107, Mesogion Ave, 115 26 Athens, Greece.

References

- 1. Sabbag A, Essayagh B, Barrera JDR, Basso C, Berni A, Cosyns Bet al. EHRA Expert consensus statement on arrhythmic mitral valve prolapse and mitral annular disjunction complex in collaboration with the ESC Council on valvular heart disease and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging endorsed cby the Heart Rhythm Society, by the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and by the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society. EP Europace 2022; doi: 10.1093/europace/euac125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Han HC, Ha FJ, Teh AW, Calafiore P, Jones EF, Johns Jet al. Mitral valve prolapse and sudden cardiac death: a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e010584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naksuk N, Syed FF, Krittanawong C, Anderson MJ, Ebrille E, DeSimone CVet al. The effect of mitral valve surgery on ventricular arrhythmia in patients with bileaflet mitral valve prolapse. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J 2016;16:187–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vaidya VR, DeSimone CV, Damle N, Naksuk N, Syed FF, Ackerman MJet al. Reduction in malignant ventricular arrhythmia and appropriate shocks following surgical correction of bileaflet mitral valve prolapse. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2016;46:137–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eckart RE, Hruczkowski TW, Tedrow UB, Koplan BA, Epstein LM, Stevenson WG. Sustained ventricular tachycardia associated with corrective valve surgery. Circulation 2007;116:2005–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]