Abstract

Aims

The effect of atrial fibrillation catheter ablation on cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure is an important outstanding research question. We undertook a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing ablation to medical therapy in patients with AF and heart failure.

Methods and results

We systematically identified all trials comparing catheter ablation to medical therapy in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. The pre-specified primary endpoint was all-cause mortality in trials with at least 2 years of follow-up. The secondary endpoint was heart failure hospitalization. Sensitivity analyses were performed for trials with any follow-up and trials deemed at low risk of bias. Eight trials (1390 patients) were included. Seven hundred and seven patients were randomized to catheter ablation and 683 to medical therapy. In the primary analysis (three trials, n = 977), catheter ablation reduced mortality compared with medical therapy [relative risk (RR): 0.61, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.44 to 0.84, P = 0.003]. Catheter ablation also reduced heart failure hospitalizations compared with medical therapy (RR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.49–0.74, P < 0.001). The effect on stroke was not statistically significant (RR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.28–1.37, P = 0.237). There was low heterogeneity between studies. Sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analyses.

Conclusion

In patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure, catheter ablation reduces mortality and the occurrence of heart failure hospitalizations.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Heart failure, Ablation, Pulmonary vein isolation, Meta-analysis

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

What’s new?

We synthesized randomized controlled trial (RCT) data of the effect of catheter ablation in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure, including a large, recently published, trial.

The pooled RCT data show that catheter ablation reduces all-cause mortality and heart failure hospitalization in these patients.

The ablation strategies varied but all included pulmonary vein isolation as the core procedure

Patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation were included.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) affects 3% of adults and is associated with increased risk of death, stroke, hospitalization, and developing heart failure. Heart failure itself is associated with an increased risk of death, hospitalization and developing AF. When AF and heart failure co-exist the prognosis is even worse than the combined risk of each alone.1,2

Catheter ablation for AF, typically by pulmonary vein isolation using either radiofrequency or cryothermal energy, has been robustly shown to reduce the incidence and burden of atrial fibrillation.3 Symptom improvements have also been seen, albeit in un-blinded studies.4 However, whether this translates to improved outcomes remains controversial. Patients with heart failure appear to be a group in which an effect of ablation on cardiovascular events can be observed, but until recently the evidence base has been small. In light of ongoing uncertainty, guidelines carry weak recommendations for AF ablation in heart failure.5,6

A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT)7 has been published evaluating mortality and heart failure hospitalization in this population. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis of RCT data including the most recent trial to formally evaluate the benefit of atrial fibrillation ablation on mortality and heart failure hospitalizations.

Methods

We carried out a meta-analysis of RCTs that evaluated the effect of AF ablation on mortality and heart failure hospitalizations for patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. We conducted the meta-analysis in accordance with the PRISMA statement.8 The protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42022324271).

Search strategy

We performed a systematic search of the MEDLINE, Cochrane, and Embase databases in March 2022 for all studies of atrial fibrillation ablation in heart failure. Our search strings included ‘(atrial fibrillation) AND [(ablation) OR (pulmonary vein isolation)]’ AND ‘heart failure’. We also hand-searched the bibliographies of relevant selected studies, reviews and meta-analyses to identify further eligible studies. Abstracts were reviewed for suitability and articles retrieved accordingly. Two independent reviewers performed the search (K.S. and A.N.), with disputes resolved by consensus following discussion with a third author (A.A.).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We considered all randomized studies of AF ablation. Studies were eligible if they randomized patients with heart failure to AF ablation or medical therapy and reported cardiovascular outcomes. Observational studies were excluded.

Endpoints

The primary efficacy endpoint was all-cause mortality in trials with at least 2 years of mean follow-up. This was to ensure sufficient follow-up duration for cardiovascular events, in particular mortality, to occur. The secondary endpoint was hospitalization for heart failure. Cardiovascular mortality and stroke were also assessed if more than one trial reported them separately from composite outcomes. Symptomatic and functional data were not assessed as un-blinded trials often cannot reliably assess these outcomes.

Data extraction and analysis

Two authors (F.S. and A.A.) independently abstracted the data from included trials and verified by a third author (J.S.). We analysed efficacy on an intention-to-treat basis. The primary outcome measure was the relative risk (RR) of all-cause mortality. RRs and their associated confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated from event data. We performed a random-effects meta-analysis using the restricted maximum likelihood estimator. We used the I2 statistic to assess heterogeneity.9 Mean values are expressed as mean ± SD unless otherwise stated. The statistical programming environment R with the metafor package was used for all statistical analysis. Included studies were assessed (J.S., Y.A.) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.10 Tests for publication bias were only planned in the event of at least 10 trials being included for analysis.10

Sensitivity analyses

Pre-specified sensitivity analysis were planned to include trials with any duration of follow-up and to include only trials judged to be at low risk of bias with regard to cardiovascular outcomes. Jackknife analyses with sequential removal of trials were also planned. Fixed-effects meta-analysis for the primary outcome was also planned.

Results

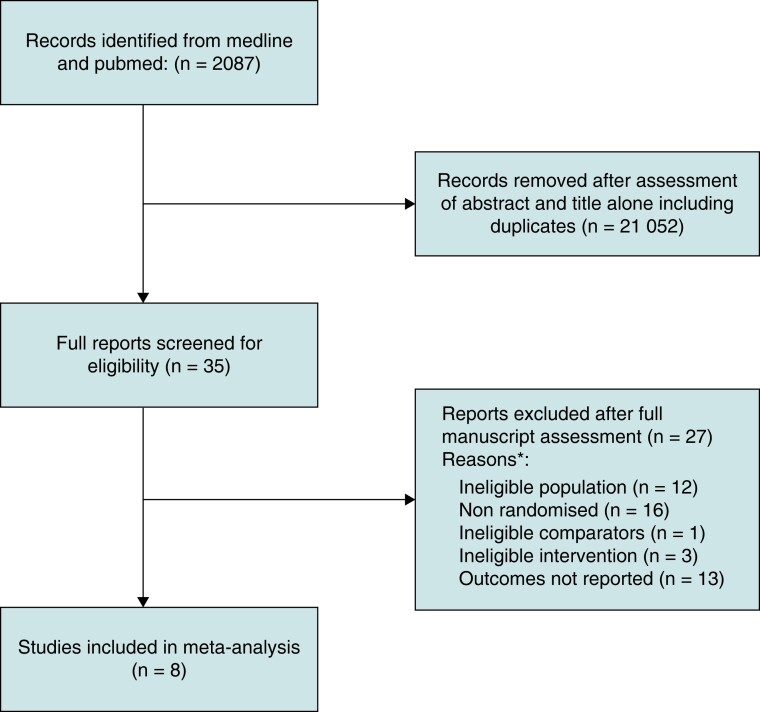

Eight trials,7,11–17 enrolling 1390 patients, met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Three trials,7,11,16 enrolling 977 patients, met the primary analysis criterion of at least 2 years mean follow-up. Four hundred and twenty-five of the latter patients were randomized to ablation and 482 were allocated to medical therapy. All three studies reported all-cause mortality and hospitalization events with mean follow-up of 33 months. Two studies (CASTLE-AF and RAFT-AF) reported stroke data. Therefore, all three of these outcomes were meta-analysed. Only one trial (RAFT-AF) reported cardiovascular mortality in sufficient detail, therefore this outcome was not meta-analysed.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and source of included studies.PRISMA flow chart for study eligibility. *some studies excluded for multiple reasons.

Across the 8 studies, the mean age was 62.6 years and the mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 28.2%. The characteristics of recruited patients and included studies are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristicsa

| Study Name | Year of Publication | Region | N | Ageb | Male % | LVEF % | Type of AFc | Ischaemic %d | NYHA%e | Devicesf | LA diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT-AF | 2022 | Brazil, Canada, Sweden, Taiwan | 411 | 66.7 | 74.3 | 30 | all | 34.6 | II 67.3 III 32.7 |

ICD 11.7% CRT 13.6% |

46 |

| AMICA | 2019 | Europe (Germany, Hungary, Spain) | 202 | 65 | 90 | 26 | psAF | 44 | II 41 III 59 |

ICD 57 CRT 43% |

50 |

| CASTLE-AF | 2018 | Europe, Australia, USA | 363 | 64 | 85.5 | 32 | all | 40 | II 58 III 29 |

ICD 73% CRT 27% |

48 |

| CAMERA-MRI | 2017 | Australia | 68 | 60.5 | 91 | 33 | psAF | 0 | II–IV 100 | n/a | 48 |

| AATAC | 2016 | USA | 203 | 61 | 74 | 30 | psAF | 62 | II–III | ICD or CRT 100% | 47 |

| CAMTAF | 2014 | UK | 50 | 57.5 | 95.5 | 33 | psAF | 23 | II 42 III 58 | n/a | 52 |

| ARC-HF | 2013 | UK | 52 | 63 | 86.5 | 24 | psAF | 38 | II 54 III 46 | ICD 7% CRT 31% |

50 |

| MacDonald et al. | 2010 | UK | 41 | 63.3 | 78 | 18 | psAF | 50 | II 9 III 91 | n/a | n/a |

n/a refers to data not reported in source trial manuscript or supplementary data

Mean age of recruited participants

Trials that included both paroxysmal and persistent AF are referred to as ‘all’; trials that recruited only persistent AF are referred to as ‘psAF’

Percentage of participants with ischaemic heart disease as cause of heart failure, remainder are non-ischaemic

Percentages of participants with each NYHA class

Device therapy at randomization

Anti-arrhythmic drug usage at baseline and follow-up summarized in supplementary material (section 3).

Table 2.

Trial characteristics

| Study and author name | Follow-upa | Eligibility criteriab | Ablation protocolc | Medical therapy | Sinus rhythm percentaged | Outcomese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT-AF Tang et al. |

37.4 | NYHA II-III | PVI ± CFAE, roof, mitral, PWI, AT | Rate control with AV node ablation if necessary | 85.6% | ACM HF hosp. Stroke |

| AMICA Hindricks et al. | 12 | NYHA II-III, LVEF <35% ICD or CRT-D indication | PVI ± CFAE, roof, mitral | Rate control or DCCV/pharmacological rhythm control electrical/pharmacological rhythm control | 73.5% | ACM CVM |

| CASTLE-AF Bansch et al. | 37.8 | NYHA II–IV LVEF <35% | PVI ± CFAE, roof, mitral, AT | Rate control or rhythm control | 63.1% | ACM CVM Stroke HF hosp. |

| CAMERA-MRI Kistler et al. | 6 | NYHA II–IV LVEF <45% | PVI ± roof, mitral, PWI | Rate control | 100% | ACM CVM Stroke HF hosp. |

| AATAC Natale et al. | 24 | NYHA II–III, LVEF <40% ICD/CRT in situ | PVI ± PWI, CFAE, AT | Pharmacological rhythm control specifically with Amiodarone | 70% | ACM HF hosp. |

| CAMTAF Schilling et al. | 6 | NYHA II-IV LVEF <50% | PVI ± CFAE, roof, mitral, AT | Rate control | 73% | ACM CVM Stroke |

| ARC-HF Wong et al. | 12 | NYHA II-IV LVEF < 35% | PVI ± CFAE, roof, mitral, AT. | Rate control | 92% | ACM CVM |

| MacDonald et al. Petrie et al. | 6 | NYHA II-IV LVEF <35% | PVI ± CFAE, roof, mitral, AT | Rate control | 50% | ACM CVM Stroke HF hosp. |

ACM = all-cause mortality; CVM = cardiovascular mortality; DCCV = direct current cardioversion; HF Hosp = heart failure hospitalization; CFAE = Complex fractionated atrial electrograms; AT = atrial tachycardia; PWI = posterior wall isolation; CRT = cardiac resynchronization therapy; ICD = implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; SR = sinus rhythm

Mean unless only median provided.

Eligibility criteria regarding NYHA status, LVEF, and device implantation.

Ablation lesion sets as stated in protocol or in sections detailing lesion sets delivered.

Percentage of patients in sinus rhythm at longest follow-up.

Outcomes, from the those of interest in this meta-analysis, reported in each trial. Outcome reporting determined from planned outcome analysis and outcome data reported elsewhere in manuscript.

Trial quality was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool and is shown in Table 3. No trial specified blinding of patients; however, the trials were generally appropriately conducted in most other respects and were included as the outcomes of interest in this meta-analysis are resistant to bias from allocation non-concealment. Four trials were graded intermediate quality as not all patients randomized were included or appropriately accounted for in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment

| Trial | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RAFT-AF | Low risk Central web-based randomization with permuted balanced blocks | High risk Open-label | High risk un-blinded | Low risk Outcomes adjudicated by a committee blinded to treatment allocation | Low risk 11 patients in both groups either did not receive allocated treatment or were lost to follow-up. All were included in original allocation group for intention-to-treat analysis | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | High: an appropriately conducted and reported open-label trial. |

| CASTLE-AF | Low risk Computerized, stratified central randomization | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Low risk Blinded endpoint committee | High risk During run-in phase, after randomization but before treatment administration, 21 intervention and 13 medical therapy patients withdrew for various reasons. These patients were not included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Subsequent losses to follow-up or change in treatment allocation were analysed as intention-to-treat. | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | Intermediate: An overall well conducted open-label trial but the pre-treatment post-randomization withdrawals not included in intention-to-treat reduce the quality of the trial. |

| AATAC | Low risk Computerized central randomization scheme was generated using block randomization, and sets of randomly selected blocks | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Intermediate risk No specific mention of blinding | Low risk No loss to follow-up | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | High: An appropriately conducted and reported open-label trial |

| CAMTAF | Low risk Random number generator with sealed envelopes | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Low risk Anonymized core lab reporting | Low risk Minimal loss to follow-up. Cardiovascular outcomes reported for all randomised participants. | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | High: An appropriately conducted and reported open-label trial |

| AMICA | Low risk Computer-generated lists of random numbers in a block design, stratified | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Low risk Blinded core lab | High risk Trial terminated due to futility. 62 patients with incomplete follow-up. | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | Intermediate: An overall well conducted open-label trial but the pre-treatment post-randomization withdrawals not included in intention-to-treat reduce the quality of the trial. |

| ARC-HF | Low risk Computer-generated sequence | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Low risk All endpoints analysed in a blinded fashion | Low risk Minimal loss to follow-up. Cardiovascular outcomes reported for all randomized participants in intention-to-treat fashion. | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | High: An appropriately conducted and reported open-label trial |

| CAMERA-MRI | Low risk Electronic block randomization using third party software | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Low risk All endpoints analysed in a blinded fashion but rhythm during assessment could not be concealed. | Some concerns Minimal loss to follow-up. Intention-to-treat analysis excluded 2 patients found ineligible or withdrawn. | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | Intermediate: An overall appropriately conducted and reported open-label trial but with a small number of randomized patients not included in intention-to-treat analysis. |

| MacDonald | Low risk Computer-generated sequence | High risk Open-label | High risk Un-blinded | Low risk All endpoints analysed in a blinded fashion | Some concerns Minimal loss to follow-up. Intention-to-treat analysis excluded 3 patients found ineligible or withdrawn | Low risk All endpoints on CT.gov reported | Intermediate: An overall appropriately conducted and reported open-label trial but with a small number of randomized patients not included in intention-to-treat analysis. |

Although patients and researchers were un-blinded to treatment allocation in every trial, this was not considered sufficient to determine these trials to be at high risk of bias with regard to the outcomes of interest in this meta-analysis, which are highly resistant to bias due lack of blinding (all-cause mortality, heart failure hospitalizations).

Effect of ablation on all-cause mortality, heart failure hospitalization, and stroke

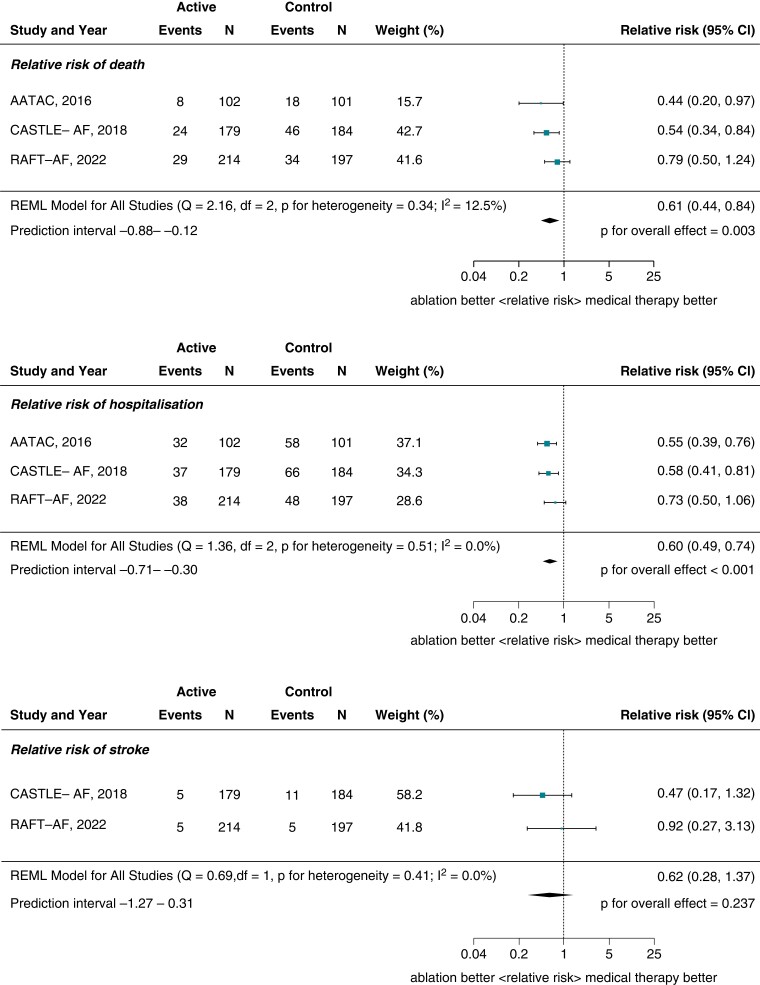

In the three trials with at least 2 years mean follow-up duration, catheter ablation resulted in a significant reduction in all-cause mortality, (Figure 2; RR: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.44–0.84, P = 0.003), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 12.5%), compared with medical therapy. Catheter ablation also resulted in a significant reduction in heart failure hospitalizations (Figure 2; RR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.49–0.74, P < 0.001), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Catheter ablation did not significantly reduce the rate of stroke (Figure 2, RR: 0.62, 95% CI: 0.28–1.37, P = 0.237) but the direction of the effect was in favour of ablation.

Figure 2.

Effect of ablation on mortality, heart failure hospitalization, and stroke. Forest plots for the primary analysis of all-cause mortality (top) and the secondary analyses of heart failure hospitalization (middle) and stroke (bottom). These plots include trials with mean follow-up ≥ 2 years.

Sensitivity analysis

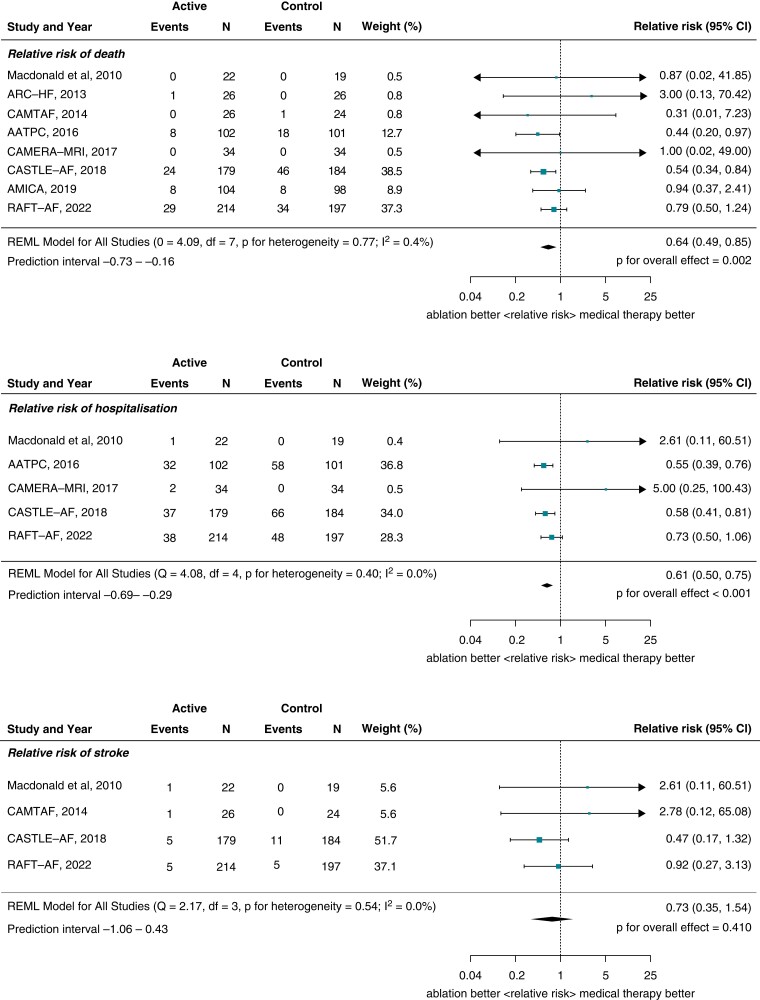

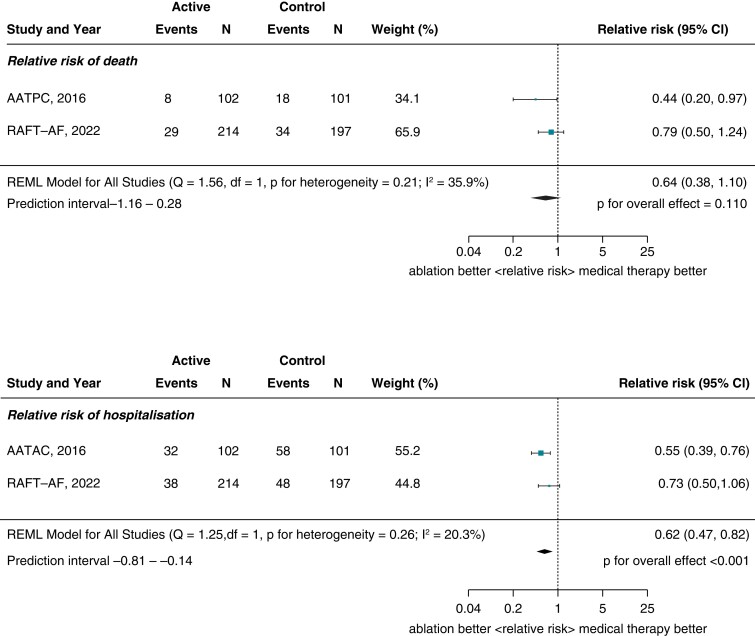

Both pre-specified sensitivity analyses were consistent with the primary analyses: (i) all trials with any duration of follow-up (Figure 3), (ii) low risk of bias trials only (Figure 4). Hazard ratio meta-analysis was performed as an exploratory analysis in trials that reported hazard data and this did not change the result (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1, supplementary appendix). Jackknife analysis showed that analyses with sequential removal of trials were also consistent with the primary analysis (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2, supplementary appendix).

Figure 3.

Sensitivity analysis—all follow-up durations. Pre-specified sensitivity analysis forest plot for all-cause mortality (top) and hospitalizations (bottom) in trials with any follow-up duration.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis—low risk of bias. Pre-specified sensitivity analyses forest plot for all-cause mortality (above) and hospitalizations (below) in trials assessed as being at low risk of bias.

Discussion

In this study we have shown that catheter ablation reduces the risk of mortality and hospitalization in patients with co-existing atrial fibrillation and heart failure. The risk of mortality and hospitalization was very high in all included trials (20% in medical therapy groups at almost 3-year follow-up), despite RCT populations often having better prognoses than real-world patients. This demonstrates the scale of impact of these two diseases occurring together and the need for proven efficacious therapies to be implemented. This is the first meta-analysis to incorporate the results of the recently published RAFT-AF trial, the results of which are shown, in this analysis, to be consistent with other trials in favour of ablation despite RAFT-AF itself having a statistically non-significant result.

European Society of Cardiology guidelines only strongly recommend AF ablation in heart failure in the context of overt tachycardiomyopathy to reverse left ventricular dysfunction, which is a relatively rare sub-group of heart failure patients with AF.5 A IIbA recommendation is offered for survival and hospitalization benefit after failed medical therapy, otherwise ablation is targeted at symptoms only. However, patients may be deterred from an invasive treatment, with upfront risk, if the only benefit they are offered is symptomatic improvement and not better prognosis. Trialling medical therapy for extended periods prior to consideration of ablation can allow adverse remodelling to occur, preventing successful ablation or preventing successful ablation from translating to better outcomes. This has been demonstrated by recent trials18,19 and analyses20 showing earlier ablation producing better outcomes.

Our findings demonstrate compelling RCT evidence of survival and hospitalization benefit with AF ablation in heart failure. There are now three large RCTs, with sufficiently long follow-up, assessing ablation in AF with heart failure and all show a reduction in mortality and hospitalizations with ablation. The effect is not statistically significant in every trial, but our meta-analysis demonstrates that the average effect is clearly significant. Furthermore, trials have now been performed in multiple settings demonstrating generalizability. The data from the trials presented here are consistent with sub-group analysis of the CABANA RCT which included patients with heart failure.4

AF ablation has also been shown to improve echocardiographic measures including LVEF and mitral regurgitation.13,17 Such measures can be prone to bias in open-label trials, which is why we did not include them in this meta-analysis. However, such data support structural remodelling as one mechanism through which sinus rhythm improves mortality and prevents hospitalizations. The point estimate for the pooled effect of ablation on stroke reduction, in the two trials that reported it, was similar to that of mortality and hospitalization reduction. However, the result was not statistically significant: this is partly because event rates were low and only two trials provided data, reducing precision, but in RAFT-AF there was no difference between the number of stroke events in each arm. It is therefore unclear if prevention of fatal strokes and fatal sequelae of strokes are another mechanism of mortality improvement. Recent evidence suggests that early ablation can reduce stroke rates in AF, although this was not a heart failure population.

The magnitude of benefit from ablation in the included trials was large. All-cause mortality risk was reduced by 39% and hospitalization rate was reduced by 40%. Given the high risk of both outcomes in the medical therapy arms of these trials and in real-world patients, the absolute benefit likely to be high.

The rate of sinus rhythm maintenance in ablation arms was variable: 63.1% in CASTLE-AF and 85.6% in RAFT-AF, for example. However, this outcome was measured in different ways, device recordings in CASTLE-AF and 12-lead ECG in RAFT-AF, making comparisons challenging and the ablation protocols were broadly similar between trials. In all trials pulmonary vein isolation was the base procedure and additional ablation via complex fractionated atrial electrogram ablation, mitral lines, roof lines, posterior wall isolation and atrial tachycardia ablation were applied on an individual patient basis. The optimal lesion set for first-time and redo ablation in patients with AF and heart failure remains unclear.

Ablation of the atrioventricular node, as an alternative ablation strategy, has gained prominence recently after a mortality benefit was observed in an RCT comparing it against medical therapy in heart failure.21 The risks of resulting pacing dependence can make this less attractive to patients. Pulmonary vein isolation and atrioventricular node ablation can be performed in the same patient: these strategies are not mutually exclusive. One RCT compared these strategies and found pulmonary vein isolation to be the more favourable of the two.22

In most of the included trials, patients were only eligible for recruitment if they had heart failure with impairment of systolic function as represented by reduced LVEF, however in RAFT-AF patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) could be included. 41.6% of the 411 recruited patients had LVEF >45%. The mean LVEF of this group was 54.6, SD 7.3 for control arm patients. In this sub-group, the direction of the point estimate for effect was in favour of ablation: 0.88 (95% CI: 0.48–1.61). Thirty percent of patients in CASTLE-AF had long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation, as did 18–28% of patients in AMICA. In the latter trial, there was a non-significant report of reduced ablation efficacy in this sub-group (HR: 1.13, CI: 0.50–2.57). Thus the findings of this meta-analysis are mainly applicable to patients with impaired systolic function and recent-onset atrial fibrillation but patients with HFpEF and long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation may also benefit from ablation.

Ablation-related serious adverse events occurred in the intervention arms of the larger trials (AATAC, CASTLE-AF, and RAFT-AF), including ten pericardial effusions, of which seven required pericardiocentesis, a death from atrio-oesophageal fistula and multiple major bleeding complications. These overall mortality and hospitalization reductions with ablation were seen despite these complications.

Limitations

We could only report the available data and cannot account for unpublished trials. CASTLE-AF lost patients to follow-up post-randomization that were not analysed in an intention-to-treat fashion but exclusion of this trial did not change the result. Medical therapy was not uniform across studies: AATAC compared ablation with amiodarone, for example, while RAFT-AF specified rate control alone. However, there was low heterogeneity between trials and in clinical practice different pharmacological strategies are used as medical therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure, including rate control and non-ablative rhythm control.

Of note, several included studies were terminated early,14,17 due to apparent futility, by the trials’ data safety and monitoring boards. These are unexpected decisions as the results of each trial suggested a favourable response to ablation and the point estimate in each trial was in the direction of ablation benefit. Trials stopped for futility do not generally bias in favour of a treatment effect and are most likely to bias against an overall treatment effect since the appearance of futility is most evident when the hazard ratio for effect is closest to unity. Therefore, the most likely outcome is that our analysis is close to the true average effect of ablation or is an underestimate.

Patients recruited for the source trials may have been selected on the basis of a perceived higher likelihood of successful ablation. Although this can limit generalizability of the findings of each trial, recruited patients had characteristics expected of typical populations with heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, heart failure and persistent atrial fibrillation are both considered to be unfavourable characteristics for successful ablation.

Conclusions

In patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure, catheter ablation reduces mortality and heart failure hospitalizations.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Florentina A Simader, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

James P Howard, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Yousif Ahmad, Section of Cardiovascular Medicine, Yale University, 330 Cedar Street, New Haven, CT 06520-8056, USA.

Keenan Saleh, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Akriti Naraen, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Jack W Samways, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Jagdeep Mohal, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Rohin K Reddy, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Nandita Kaza, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Daniel Keene, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Matthew J Shun-Shin, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Darrel P Francis, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Zachary I Whinnett, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Ahran D Arnold, National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Du Cane Road, London, W12 0HS, London, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

J.M. and J.P.H. are supported by the British Heart Foundation (BHF, FS/CRTF/21/24171 and FS/ICRF/22/26039). A.D.A. is supported by the Imperial BHF Centre of Research Excellence (RE/18/4/34215) and the National Institute of Health Resarch (NIHR).

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Deisenhofer I. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: prime time for ablation! Heart Rhythm O2 2021;2:754–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PAet al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the framingham heart study. Circulation 2003;107:2920–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ganesan AN, Shipp NJ, Brooks AG, Kuklik P, Lau DH, Lim HSet al. Long-term outcomes of catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 2013;2:e004549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Packer DL, Piccini JP, Monahan KH, Al-Khalidi HR, Silverstein AP, Noseworthy PAet al. Ablation versus drug therapy for atrial fibrillation in heart failure: results from the CABANA trial. Circulation 2021;143:1377–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist Cet al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS) the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2020;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JCet al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:104–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parkash R, Wells GA, Rouleau J, Talajic M, Essebag V, Skanes Aet al. Randomized ablation-based rhythm-control versus rate-control trial in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation: results from the RAFT-AF trial. Circulation 2022;145:1693–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med 2002;21:1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman ADet al. The cochrane collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Di Biase L, Mohanty P, Mohanty S, Santangeli P, Trivedi C, Lakkireddy Det al. Ablation versus amiodarone for treatment of persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with congestive heart failure and an implanted device: results from the AATAC multicenter randomized trial. Circulation 2016;133:1637–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hunter RJ, Berriman TJ, Diab I, Kamdar R, Richmond L, Baker Vet al. A randomized controlled trial of catheter ablation versus medical treatment of atrial fibrillation in heart failure (the CAMTAF trial). Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology 2014;7:31–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones DG, Haldar SK, Hussain W, Sharma R, Francis DP, Rahman-Haley SLet al. A randomized trial to assess catheter ablation versus rate control in the management of persistent atrial fibrillation in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1894–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuck K-H, Merkely B, Zahn R, Arentz T, Seidl K, Schlüter Met al. Catheter ablation versus best medical therapy in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure: the randomized AMICA trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2019;12:e007731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. MacDonald MR, Connelly DT, Hawkins NM, Steedman T, Payne J, Shaw Met al. Radiofrequency ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with advanced heart failure and severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction: a randomised controlled trial. Heart 2011;97:740–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marrouche NF, Brachmann J, Andresen D, Siebels J, Boersma L, Jordaens Let al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med 2018;378:417–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prabhu S, Taylor AJ, Costello BT, Kaye DM, McLellan AJ, Voskoboinik Aet al. Catheter ablation versus medical rate control in atrial fibrillation and systolic dysfunction: the CAMERA-MRI study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1949–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirchhof P, Camm AJ, Goette A, Brandes A, Eckardt L, Elvan Aet al. Early rhythm-control therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Eng J Med 2020;383:1305–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Packer DL, Kowal RC, Wheelan KR, Irwin JM, Champagne J, Guerra PGet al. Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: first results of the north American Arctic front (STOP AF) pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1713–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim D, Yang P-S, You SC, Sung J-H, Jang E, Yu HTet al. Treatment timing and the effects of rhythm control strategy in patients with atrial fibrillation: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2021;373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brignole M, Pentimalli F, Palmisano P, Landolina M, Quartieri F, Occhetta Eet al. AV Junction ablation and cardiac resynchronization for patients with permanent atrial fibrillation and narrow QRS: the APAF-CRT mortality trial. Eur Heart J 2021;42:4731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khan MN, Jaïs P, Cummings J, Di Biase L, Sanders P, Martin DOet al. Pulmonary-vein isolation for atrial fibrillation in patients with heart failure. N Eng J Med 2008;359:1778–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.