Abstract

Aims

Accessory pathway (AP) ablation is a standard procedure for the treatment of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW). Twelve-lead electrocardiogram (ECG)-based delta wave analysis is essential for predicting ablation sites. Previous algorithms have shown to be complex, time-consuming, and unprecise. We aimed to retrospectively develop and prospectively validate a new, simple ECG-based algorithm considering the patients’ heart axis allowing for exact localization of APs in patients undergoing ablation for WPW.

Methods and results

Our multicentre study included 211 patients undergoing ablation of a single manifest AP due to WPW between 2013 and 2021. The algorithm was developed retrospectively and validated prospectively by comparing its efficacy to two established ones (Pambrun and Arruda). All patients (32 ± 19 years old, 47% female) underwent successful pathway ablation. Prediction of AP-localization was correct in 197 patients (93%) (sensitivity 92%, specificity 99%, PPV 96%, and NPV 99%). Our algorithm was particularly useful in correctly localizing antero-septal/-lateral (sensitivity and specificity 100%) and posteroseptal (sensitivity 98%, specificity 92%) AP in proximity to the tricuspid valve. The accuracy of EASY-WPW was superior compared to the Pambrun (93% vs. 84%, P = 0.003*) and the Arruda algorithm (94% vs. 75%, P < 0.001*). A subgroup analysis of children (n = 58, 12 ± 4 years old, 55% female) revealed superiority to the Arruda algorithm (P < 0.001*). The reproducibility of our algorithm was excellent (ϰ>0.8; P < 0.001*).

Conclusion

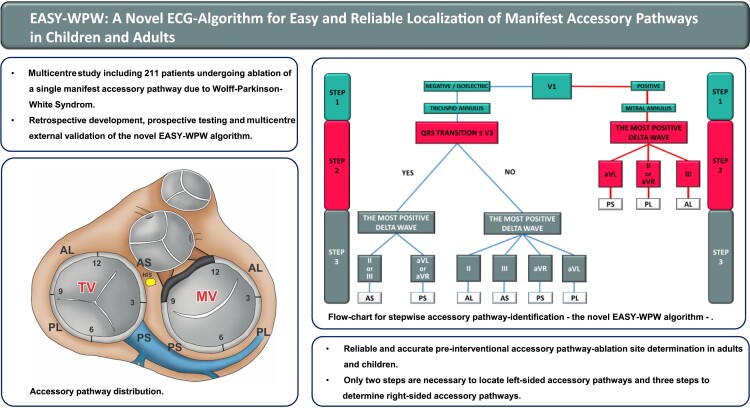

The novel EASY-WPW algorithm provides reliable and accurate pre-interventional ablation site determination in WPW patients. Only two steps are necessary to locate left-sided AP, and three steps to determine right-sided AP.

Keywords: Accessory pathway localization, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, Catheter ablation, Electrocardiography, Algorithm

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

What’s new?

Our novel 12-lead ECG-based EASY-WPW algorithm enables reliable and accurate pre-interventional AP-ablation site determination in adults and children.

Only two steps are necessary to locate left-sided AP and three steps to determine right-sided AP.

This can be done with the help of a simple flowchart or, in the future, with the help of an app.

Introduction

Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome (WPW) is characterized by the presence of an accessory pathway (AP) between the atrium and the ventricle. In some patients, WPW is an incidental finding as they are completely asymptomatic, whereas others develop palpitations, atrial fibrillation, syncope, or life-threatening ventricular fibrillation.1,2

Typical 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) characteristics of WPW include a short PR-interval, a delta wave, and a wide QRS complex. In case of recurrent or severe symptoms, an electrophysiological study (EPS) followed by an AP-ablation is recommended.3 For optimized patient education, ablation planning and performance pre-interventional determination of AP-localization is desirable. Thus, several algorithms for AP-localization primarily including the polarity of delta waves, the QRS complex, or both, have been developed.4–10 However, they have shown to be complex, time-consuming, and often unprecise because of a variable anatomical heart axis, especially in children.11–14 As WPW is the most common cause of tachycardia in children,2 a more sensitive and reliably applicable AP-algorithm in pediatric patients is strongly required.

We aimed to retrospectively develop, prospectively test, and externally validate a novel, simple 12-lead ECG-based algorithm considering the patients’ heart axis allowing for an accurate and reliable pre-interventional AP-site localization in adults and children.

Methods

Patients were selected consecutively between 2013 and 2021. Our multicentre study included 211 patients with a single manifest AP. One hundred and nine of them (109/211, 52%) were referred to our department for AP assessment and ablation. One hundred and two patients (102/211, 48%) were treated in other centres. Additionally, a subgroup analysis for children < 18 years old (58/211, 28%) was performed. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) first ablation of a manifest AP, (2) absence of structural heart disease, and (3) absence of multiple APs. Further details are summarized in Supplementary material online, Figure S1.

The study was performed in compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Reg. No. 2019-563).

Ablation procedure

All procedures were performed under conscious sedation using propofol and analgesia with fentanyl as required. Antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) were discontinued at least three half-lives before ablation.

For EPS, three diagnostic catheters were percutaneously inserted through the femoral vein. One diagnostic catheter was placed in the coronary sinus (CS), while the other diagnostic catheter was positioned at the His bundle. The third diagnostic catheter was positioned in the apex of the right ventricle (RV). During EPS, pathway location and characteristics were determined. The ablation catheter choice depended on the AP-localization and physician preference. Vascular access (femoral vein or artery), additional material (long sheath for catheter stability), and energy source (standard radiofrequency, irrigated radiofrequency, or cryothermy) varied with ablation site. During left-sided AP-ablation intravenous heparin was administered to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) of 300 s throughout the procedure. Persistent ablation success was confirmed after a waiting period of 30 min by adenosine administration. Pericardial effusion (PE) was ruled out immediately after ablation and the next day.

Algorithm development

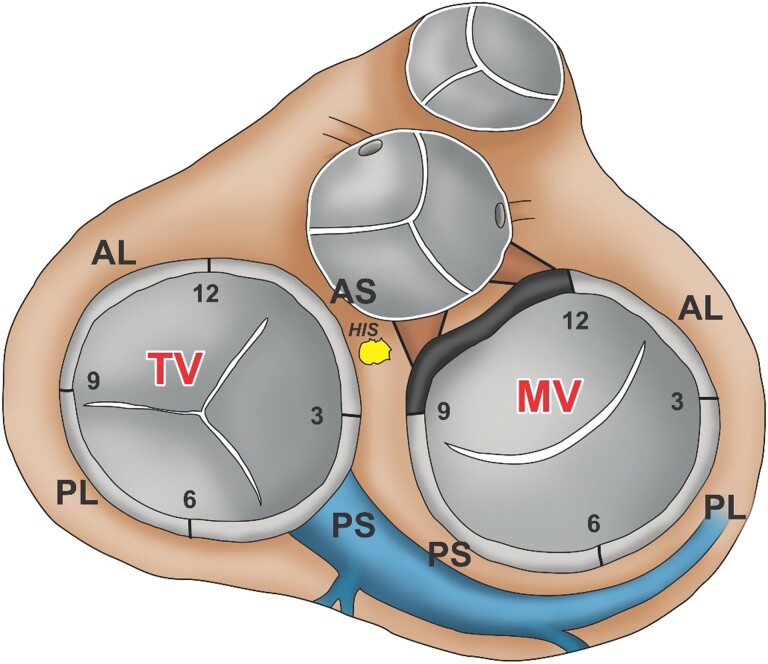

The EASY-WPW algorithm was developed retrospectively. Seven anatomical sites are distinguished as viewed in the left anterior oblique view (60°). These are defined as follows: (1) tricuspid valve (TV) anteroseptal, from 12 to 3° clock; including the atrioventricular node (AVN) and His bundle (HIS); (2) TV posteroseptal, from 3 to 6° clock, including the CS ostium; (3) TV posterolateral, from 6 to 9° clock; (4) TV anterolateral, from 9 to 12° clock; (5) mitral valve (MV) anterolateral, 12 to 3° clock; (6) MV posterolateral, from 3 to 6° clock; and (7) MV posteroseptal, from 6 to 9° clock (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Accessory pathway’s distribution. Schematic representation of the atrioventricular junction region as viewed in the left anterior oblique view (60°). Clockwise (bold numbers) the following accessory pathway localizations are distinguished: TV, tricuspid valve: AL, anterolateral; AS, anteroseptal; PL, posterolateral; PS, posteroseptal; MV, mitral valve: AL, PL, PS; HIS, His bundle.

Algorithm assessment

After retrospective development, our novel EASY-WPW algorithm was prospectively tested and a multicentre external validation was performed. In all patients, the exact ablation site of the AP was verified by an EPS. Beyond that, the reproducibility of our novel algorithm was tested by three investigators. All three were blinded to the ablation procedures and each other’s conclusions. The results of the new algorithm were compared to those obtained from two established AP-algorithms (Pambrun6 and Arruda4).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS, version 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical and ordinal data were examined by chi-square, Mann–Whitney tests, or Fisher’s exact tests, respectively. The accuracy of the algorithm was defined as the percentage of patients with an exact prediction of the successful ablation site. The reproducibility of the algorithm was set as the level of agreement between investigators in determining the exact AP-localization. Kappa values > 0.75 were considered to indicate an excellent agreement. Data are presented as mean ± SD or percentage value unless stated otherwise. A P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Algorithm description

The EASY-WPW algorithm is based on both, the analysis of QRS polarity and transition as well as the most positive delta wave or the most positive QRS complex if delta wave is not well differentiated. The delta wave is defined as the first 20–40 ms of the earliest QRS deflection.

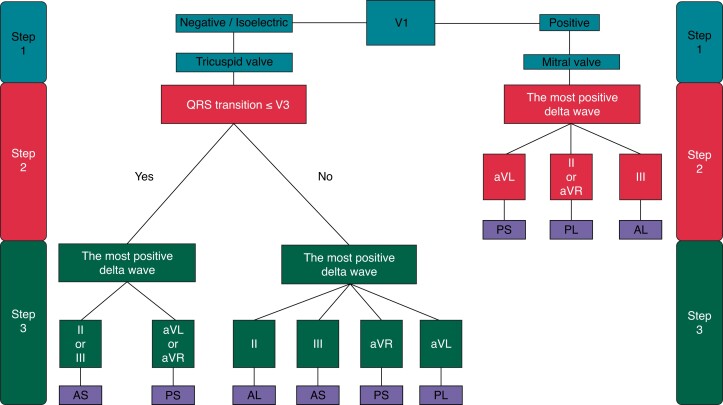

Our novel algorithm includes a two-step approach for a left-sided AP (MV) and a three-step-identification of a right-sided AP (TV), respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart for stepwise AP-identification. The validated EASY-WPW algorithm with a three-step approach for right-sided AP (tricuspid valve) and a two-step approach for left-sided AP (mitral valve). AL, anterolateral; AP, accessory pathway; AS, anteroseptal; PL, posterolateral; PS, posteroseptal.

V1 lead polarity discriminates between left- and right-sided AP-localization.

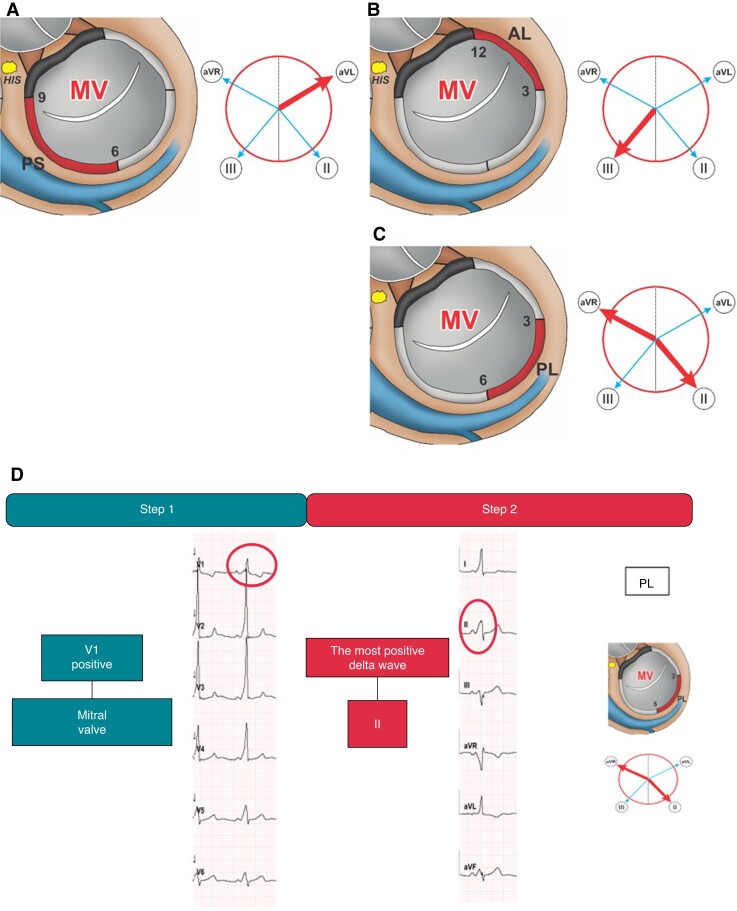

Left-sided AP

Step 1 (lead V1 polarity) Positive polarity defines a left-sided AP. Step 2 (most positive delta wave) The most positive delta wave in leads II, III, aVR, aVL determines the exact AP-localization. In detail, the most positive delta wave in aVL indicates posteroseptal, in II or aVR posterolateral, and in III anterolateral AP-localization (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Left-sided accessory pathways. Schematic representation of the MV junction region as viewed in the left anterior oblique view (60°) illustrating posteroseptal (A), anterolateral (B), and posterolateral (C) AP-localizations. The adjacent Cabrera circles indicate the corresponding leads with the most positive delta wave (bold red arrow). ECG-Identification of a left-sided posterolateral AP with the EASY-WPW algorithm (D). MV, mitral valve; PS, posteroseptal; AL, anterolateral; PL, posterolateral; AP, accessory pathway.

Right-sided AP

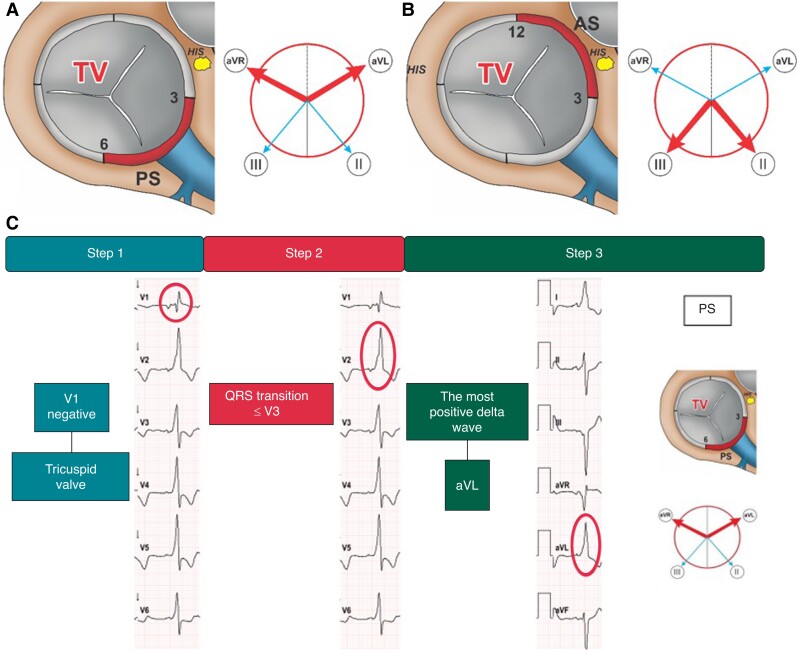

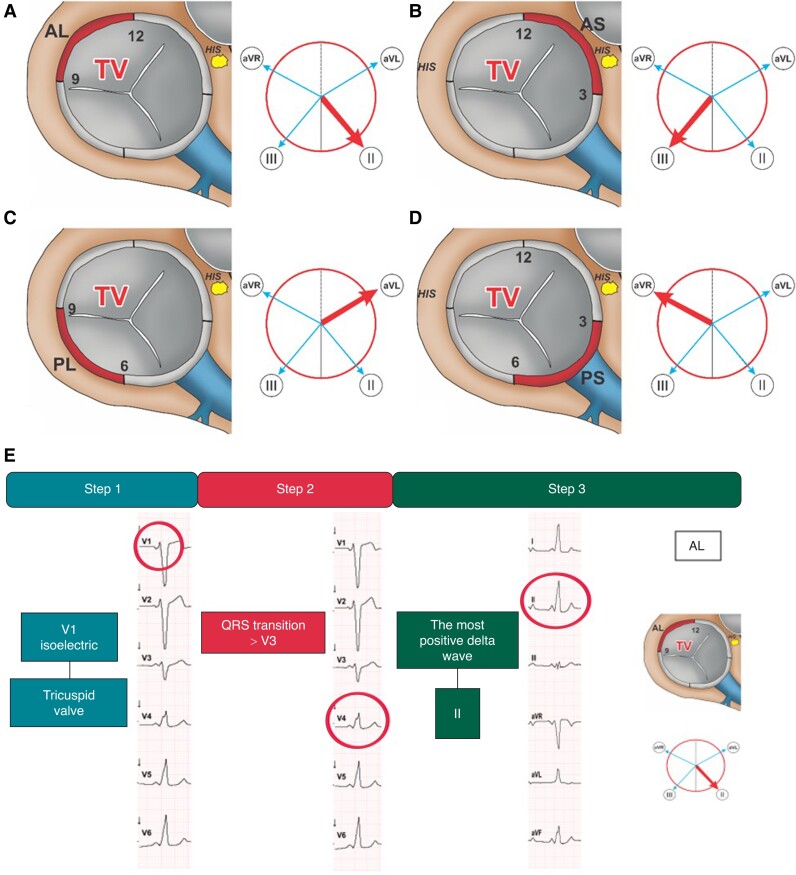

Step 1 (lead V1 polarity) Negative polarity or isoelectric V1 indicates a right-sided AP. Step 2 (lead V3 polarity) QRS transition in the precordial leads (≤ or > V3) determines the further procedure in Step 3. Step 3 (most positive delta wave) the most positive delta wave in leads II, III, aVR, aVL determines the exact AP-localization. (A) QRS transition ≤ V3: The most positive delta wave in II or III indicates anteroseptal and the most positive delta wave in aVR or aVL displays posteroseptal AP-localization (Figure 4). (B) QRS transition > V3: The most positive delta wave in aVL indicates posterolateral, in II anterolateral, in III anteroseptal, and in aVR posteroseptal AP-localization (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Right-sided accessory pathways with QRS transition ≤ V3. Schematic representation of the TV junction region as viewed in the left anterior oblique view (60°) illustrating posteroseptal (A) and anteroseptal (B) AP-localization. The adjacent Cabrera circles indicate the corresponding leads with the most positive delta wave (bold arrow). ECG-identification of a right-sided posteroseptal AP with the EASY-WPW algorithm (C).TV, tricuspid valve; PS, posteroseptal; AS, anteroseptal; HIS, His bundle; AP, accessory pathway.

Figure 5.

Right-sided accessory pathways with QRS transition > V3. Schematic representation of the TV junction region as viewed in the left anterior oblique view (60°) illustrating anterolateral (A), anteroseptal (B), posterolateral (C), and posteroseptal (D) AP-localization. The adjacent Cabrera circles indicate the corresponding leads with the most positive delta wave (bold arrow). ECG-identification of a right-sided anterolateral AP with the EASY-WPW algorithm (E). AL, anterolateral; AP, accessory pathway; AS, anteroseptal; HIS, His bundle; PS, posteroseptal; PL, posterolateral; TV, tricuspid valve.

ECG examples for the identification of different APs with the EASY-WPW algorithm are presented in Figures 3–5.

Results

Study population

The total study population consisted of 211 patients (32 ± 19 years old, 47% female). Prospective testing included 109 patients (109/211, 52%) (29 ± 18 years old, 45% female). The multicentre external validation was performed in 102 patients (102/211, 48%) (42 ± 20 years old, 50% female). Our novel algorithm was applied to 58 children < 18 years old (58/211, 27%) (12 ± 4 years old, 55% female). Forty of them were tested prospectively (40/58, 69%) (11 ± 4 years old, 45% female) and 18 of them were validated externally (18/58, 31%) (14 ± 2 years old, 78% female).

Accessory pathway distribution

The distribution of successful AP-ablation sites in all patients and in the subgroup of children < 18 years old is presented in Supplementary material online, Figure S2.

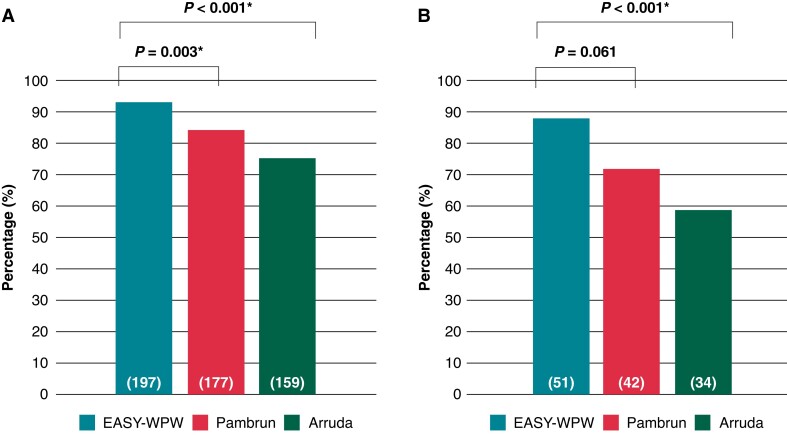

Algorithm accuracy

Applied to the overall study population our novel EASY-WPW algorithm was superior compared to the Pambrun (93% vs. 84%, P = 0.003*) and the Arruda algorithm (94% vs. 75%, P < 0.001*) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Direct comparison of AP-algorithms. Direct comparison of the accuracy of AP-algorithms. In all patients, the accuracy (percentage of patients with an exact prediction of AP-localization) of the EASY-WPW algorithm was superior compared to the PAMBRUN (93% vs. 84%, P = 0.003*) and the ARRUDA algorithm (94% vs. 75%, P < 0.001*) (A). A subgroup analysis of children < 18 years old revealed significant superiority to the ARRUDA algorithm (P < 0.001*) (B). P < 0.05 and * indicate statistical significance. AP, accessory pathway.

A subgroup analysis of children < 18 years old revealed a higher accuracy compared to the Pambrun (88% vs. 72%, P < 0.061) and significant superiority compared to the Arruda algorithm (88% vs. 59%, P < 0.001*) (Figure 6). To further distinguish children < 12 years old from teenagers, we performed a subgroup analysis of children < 12 years old demonstrating a higher accuracy of the EASY-WPW algorithm compared to the Pambrun and the Arruda algorithm, too (see Supplementary material online, Figure S5). The results gained from our prospective testing are comparable to those obtained from the multicentre external validation (see Supplementary material online, Figures S3 and S4).

For all AP-localizations, our novel EASY-WPW algorithm achieved a higher accuracy in both adults and children compared to the Pambrun and the Arruda algorithm. Particularly good results were obtained in the presence of septal, anterior, and right-sided AP-localizations. Children performed slightly worse, but still better in direct comparison to the Pambrun and the Arruda algorithm. Detailed information is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Algorithm accuracy depending on the AP-localization

| AP-localization | Algorithm accuracy (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EASY-WPW | PAMBRUN | ARRUDA | ||||

| All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | |

| Total | 93 | 88 | 84 | 72 | 75 | 59 |

| MV | 92 | 83 | 85 | 71 | 82 | 71 |

| TV | 95 | 91 | 82 | 74 | 69 | 50 |

| septal | 96 | 90 | 90 | 80 | 85 | 75 |

| lateral | 91 | 87 | 79 | 68 | 67 | 39 |

| anterior | 96 | 96 | 90 | 87 | 85 | 100 |

| posterior | 92 | 83 | 81 | 63 | 71 | 51 |

Algorithm accuracy (percentage of patients with an exact prediction of AP-localization) depends on the AP-localization in the entire cohort of patients compared to the subgroup of children < 18 years old. MV, mitral valve; TV, tricuspid valve; All, all patients; < 18, subgroup of children < 18 years old.

The averaged sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the EASY-WPW algorithm compared to the Pambrun and the Arruda algorithm for each AP-localization are presented in Table 2. Particularly good results were achieved with our algorithm in the presence of an anteroseptal (sensitivity and specificity 100%) or posteroseptal (sensitivity 98%, specificity 92%) AP in proximity to the TV.

Table 2.

Algorithm performance for each of the seven ablation sites

| Ablation site | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EASY-WPW | PAMBRUN | ARRUDA | EASY-WPW | PAMBRUN | ARRUDA | EASY-WPW | PAMBRUN | ARRUDA | EASY-WPW | PAMBRUN | ARRUDA | |||||||||||||

| All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | All | < 18 | |

| Total | 92 | 82 | 81 | 70 | 68 | 61 | 99 | 98 | 97 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 96 | 95 | 83 | 72 | 74 | 61 | 99 | 98 | 97 | 95 | 96 | 95 |

| TV anteroseptal | 100 | 100 | 94 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98 | 94 | 97 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 80 | 57 | 74 | 67 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| TV posteroseptal | 98 | 100 | 89 | 85 | 82 | 77 | 92 | 84 | 90 | 82 | 87 | 79 | 82 | 65 | 77 | 58 | 70 | 56 | 99 | 100 | 96 | 95 | 93 | 91 |

| TV posterolateral | 80 | 63 | 53 | 38 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 90 | 98 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 67 | 75 | 30 | 9 | 99 | 94 | 96 | 91 | 94 | 94 |

| TV anterolateral | 93 | 100 | 71 | 78 | 29 | 38 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 98 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 83 | 88 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 98 | 96 | 95 | 91 |

| MV anterolateral | 95 | 90 | 93 | 90 | 98 | 90 | 100 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 97 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 91 | 90 | 89 | 100 | 99 | 98 | 98 | 98 | 99 | 98 |

| MV posterolateral | 90 | 91 | 76 | 64 | 67 | 70 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 100 | 97 | 94 | 200 | 100 | 97 | 100 | 85 | 94 | 98 | 98 | 94 | 92 | 92 | 94 |

| MV posteroseptal | 88 | 33 | 88 | 33 | 81 | 50 | 99 | 100 | 98 | 96 | 95 | 94 | 92 | 100 | 85 | 33 | 70 | 94 | 98 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 97 | 98 |

Algorithm performance for each of the seven ablation sites in the entire cohort of patients compared to the subgroup of children < 18 years old. Particularly good results were achieved with our EASY-WPW algorithm in the presence of a right-sided antero- or posteroseptal AP. TV, tricuspid valve; MV, mitral valve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; All, all patients; < 18, subgroup of children < 18 years old.

Concerning the investigator dependent accuracy of the EASY-WPW algorithm, AP-localizations were correctly identified by the three investigators in 92% (583 of 633) of patients with our novel algorithm compared to 81% (512 of 633) of patients with the Pambrun (P < 0.001*) and 73% (461 of 633) of patients with the Arruda algorithm (P < 0.001*). Thus, accuracy proved consistently higher with the novel EASY-WPW algorithm, regardless of different investigators (see Supplementary material online, Table S1).

With regard to the reproducibility, the agreement between investigators was excellent (see Supplementary material online, Table S2).

Discussion

We developed a novel, simple stepwise 12-lead ECG-based algorithm allowing for an accurate and reliable pre-interventional AP-site localization in adults and children (Figures 1–6, Supplementary material online, Figures S3 and S4). In the past, several AP-algorithms have been published.4–14 Most of them were designed retrospectively. Only a few of them were additionally validated prospectively. Even fewer were specifically designed for use in children.12–14

To examine the accuracy and reliability of our novel EASY-WPW algorithm in predicting the exact AP-localization we compared it to the established Arruda4 and Pambrun algorithm.6

In contrast to the Pambrun algorithm, which requires an EPS our novel EASY-WPW algorithm as well as the Arruda algorithm can be applied to pre-procedural 12-lead ECGs. Thus, our EASY-WPW algorithm offers several advantages for optimized patient education, ablation planning, and performance as not only the ablation strategy (e.g. choice of access, catheter, energy form, need for trans-septal puncture) but also the success- and complication rate (e.g. risk of AV block and embolism) as well as procedure- and fluoroscopy time vary considerably, depending on the exact AP-localization.

Discrimination of AP-localizations

The Arruda algorithm allows discrimination of 10 AP-sites, the Pambrun algorithm considers nine and our EASY-WPW algorithm differentiates between seven AP-localizations (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2). In our opinion, a reliable classification into seven localizations is sufficient to evaluate the most relevant aspects pre-interventionally. Too many locations may complicate the algorithm unnecessarily and make it less accurate, as we observed particularly in terms of the Arruda algorithm.

Stepwise approach for AP-localization

The Arruda and the Pambrun algorithms appear complex and time-consuming. Our algorithm requires the fewest steps, so that it is the fastest and easiest to apply (Figure 2).

Algorithm efficacy

Although Arruda et al. reported on an overall sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 99%4 we could not obtain satisfactory results with the Arruda algorithm (Figure 6, Tables 1 and 2). Concerning the accuracy, the Pambrun algorithm performed better than the Arruda algorithm, but our novel EASY-WPW algorithm proved to be superior to both (Figure 6, Tables 1 and 2). Arruda et al. reported that their algorithm is particularly useful in correctly localizing anteroseptal (sensitivity 75%, specificity 99%) and mid-septal (sensitivity 100%, specificity 98%) AP,4 which are of special interest due to their proximity to the AVN and HIS with risk of AV block. Applied to our study population, our EASY-WPW algorithm yielded better results regarding the correct prediction of antero- and posteroseptal AP in proximity to the tricuspid valve (Tables 1 and 2).

As far as reproducibility is concerned the agreement between investigators was excellent (see Supplementary material online, Tables S1 and S2).

Application in children

Due to an age-dependent variability of the heart axis, algorithms primarily developed for adults often do not provide satisfactory results in children.11,14

The Pambrun as well as the Arruda study included adolescents,4,6 but no subgroup analysis on children was performed. Thus, no conclusions were made about the applicability in pediatric patients in either study. Wren et al. examined the accuracy in predicting the AP-localization in children with WPW for seven published algorithms, including the Arruda algorithm.11 Overall accuracy of prediction was only 30–49%. The identification of septal pathways was even worse with an accuracy of 5–35%.11 Another study reported on similar results.13 For a specific validation of our EASY-WPW algorithm in pediatric patients we conducted subgroup analyses with children < 18 and < 12 years old. Although the results were slightly worse, they were comparable to those gained from adults. In children < 18 years old, our algorithm was superior to the Pambrun as well as to the Arruda algorithm (Figure 6, Tables 1 and 2) and even in children < 12 years old our EASY-WPW algorithm achieves higher accuracy rates (see Supplementary material online, Figure S5).

Thus, our EASY-WPW algorithm seems to perform better in children compared to the results gained from other algorithms.11–14

Beyond that, studies exclusively focusing on the AP-localization in children are very scarce.12–14Boersma et al. presented an algorithm which was retrospectively developed in 135 children with RFA for WPW. The authors reported on a reasonable sensitivity and specificity for only five AP-sites.12 The pediatric algorithm developed by Li et al. presents with a better accuracy for left- (100%) and right-sided AP (88.6%), but only allows for differentiation of four regions.13Beak et al. developed another algorithm for children, which proved superior to established ones with a documented sensitivity of 95.7% for septal pathways, but still shows worse results compared to our EASY-WPW algorithm14 (Figure 6, Tables 1 and 2).

Comparison to the St. George’s algorithm

The St. George’s algorithm is based on the polarity and morphology of QRS-complexes.15 As Xie et al. did not perform a subgroup analysis in children < 18 years old, the validity of the St. George’s algorithm in children remains unclear.

Xie et al. performed a prospective analysis in 46 patients.15 This, of course, does not allow for a reliable and valid evaluation of the authors’ algorithm for use in clinical practice.

The St. George’s algorithm distinguishes 11 regions along the atrioventricular annuli.15 As already demonstrated for the Arruda algorithm, too many locations may complicate the algorithm unnecessarily and make it less accurate (Figure 6, Tables 1 and 2). Basiouny et al. found significantly lower results for algorithms with more than six possible locations for the AP.16

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to present a simple algorithm that provides accurate and reliable results in both adults and children. Currently, our EASY-WPW algorithm can be applied using a simple flowchart (Figure 2).

Outlook

In the future, our findings could serve as a training dataset for artificial intelligence applications. As already demonstrated in one study,17 it is conceivable that deep learning models will be developed soon allowing for an immediate determination of AP-sites e.g. with the help of an app.

Limitations

As the presence of multiple APs was an exclusion criterion in our study, there is limited experience in using our novel WPW algorithm in patients with multiple pathways. Beyond that, fibrosis and scar tissue induced by a prior ablation or structural heart disease may affect the delta wave ECG pattern.

Conclusion

Our novel 12-lead ECG-based EASY-WPW algorithm enables reliable and accurate pre-interventional AP-ablation site determination in adults and children with a single AP and without structural heart disease. Only two steps are necessary to locate left-sided AP and three steps to determine right-sided AP. This can be done with the help of a simple flowchart or, in the future, with the help of an app.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Mustapha El Hamriti, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Martin Braun, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Stephan Molatta, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany; Center for Congenital Heart Disease/Pediatric Heart Center, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Guram Imnadze, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Moneeb Khalaph, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Philipp Lucas, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Julia Kathinka Nolting, Clinic for General and Interventional Cardiology/Angiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Khuraman Isgandarova, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Vanessa Sciacca, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Thomas Fink, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Leonard Bergau, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany; Clinic for Cardiology, University Goettingen, Robert-Koch-Str. 40, 37075 Goettingen, Germany.

Christian Sohns, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Kunihiko Kiuchi, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kobe University Hospital, 7-5-2 Kusunokicho, Chuo-ku, Kobe City, Japan; Section of Arrhythmia, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kobe University Hospital, 7-5-2 Kusunokicho, Chuo-ku, Kobe City, Japan.

Makoto Nishimori, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Kobe University Hospital, 7-5-2 Kusunokicho, Chuo-ku, Kobe City, Japan.

Christian-Hendrik Heeger, Department of Rhythmology, University Heart Centre Lübeck, Ratzeburger Allee 160, 23538 Lübeck, Germany.

Martin Borlich, Heart Center, Segeberger Kliniken (Academic Teaching Hospital of the Universities of Kiel, Lübeck and Hamburg), Am Kurpark 1, Bad Segeberg, 23795 Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

Dong-In Shin, Clinic for Cardiology, Herzzentrum Niederrhein, HELIOS Klinikum Krefeld, Lutherplatz 40, 47805 Krefeld, Germany.

Sonia Busch, Cardiology Department, Klinikum Coburg GmbH, Coburg, Germany.

Denise Guckel, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Philipp Sommer, Clinic for Electrophysiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

No funding obtained.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Antz M, Weiss C, Volkmer M, Hebe J, Ernst S, Ouyang Fet al. Risk of sudden death after successful accessory atrioventricular pathway ablation in resuscitated patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002;13:231–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Derejko P, Szumowski LJ, Sanders P, Krupa W, Bodalski R, Orczykowski Met al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: role of pulmonary veins. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2012;23:280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brugada J, Katritsis DG, Arbelo E, Arribas F, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist Cet al. 2019 ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia. The task force for the management of patients with supraventricular tachycardia of the European society of cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2020;41:655–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arruda MS, McClelland JH, Wang X, Beckman KJ, Widman LE, Gonzalez MDet al. Development and validation of an ECG algorithm for identifying accessory pathway ablation site in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1998;9:2–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fitzpatrick AP, Gonzales RP, Lesh MD, Modin GW, Lee RJ, Scheinman MM. New algorithm for the localization of accessory atrioventricular connections using a baseline electrocardiogram. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;23:107–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pambrun T, El Bouazzaoui R, Combes N, Combes S, Sousa P, Le Bloa Met al. Maximal Pre-excitation based algorithm for localization of manifest accessory pathways in adults. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:1052–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. d'Avila A, Brugada J, Skeberis V, Andries E, Sosa E, Brugada P. A fast and reliable algorithm to localize accessory pathways based on the polarity of the QRS complex on the surface ECG during sinus rhythm. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1995;18:1615–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chiang CE, Chen SA, Teo WS, Tsai DS, Wu TJ, Cheng CCet al. An accurate stepwise electrocardiographic algorithm for localization of accessory pathways in patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome from a comprehensive analysis of delta waves and R/S ratio during sinus rhythm. Am J Cardiol 1995;76:40–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iturralde P, Araya-Gomez V, Colin L, Kershenovich S, de Micheli A, Gonzalez-Hermosillo JA. A new ECG algorithm for the localization of accessory pathways using only the polarity of the QRS complex. J Electrocardiol 1996;29:289–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Milstein S, Sharma AD, Guiraudon GM, Klein GJ. An algorithm for the electrocardiographic localization of accessory pathways in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1987;10:555–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wren C, Vogel M, Lord S, Abrams D, Bourke J, Rees Pet al. Accuracy of algorithms to predict accessory pathway location in children with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Heart 2012;98:202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boersma L, García-Moran E, Mont L, Brugada J. Accessory pathway localization by QRS polarity in children with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002;13:1222–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li HY, Chang SL, Chuang CH, Lin MC, Lin YJ, Lo LWet al. A novel and simple algorithm using surface electrocardiogram that localizes accessory conduction pathway in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in pediatric patients. Acta Cardiol Sin 2019;35:493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baek SM, Song MK, Uhm JS, Kim GB, Bae EJ. New algorithm for accessory pathway localization focused on screening septal pathways in pediatric patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:2172–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Xie B, Heald SC, Bashir Y, Katritsis D, Murgatroyd FD, Camm AJet al. Localization of accessory pathways from the 12-lead electrocardiogram using a new algorithm. Am J Cardiol 1994;74:161–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Basiouny T, de Chillou C, Fareh S, Kirkorian G, Messier M, Sadoul Net al. Accuracy and limitations of published algorithms using the twelve-lead electrocardiogram to localize overt atrioventricular accessory pathways. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1999;10:1340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nishimori M, Kiuchi K, Nishimura K, Kusano K, Yoshida A, Adachi Ket al. Accessory pathway analysis using a multimodal deep learning model. Sci Rep 2021;11:8045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.