Abstract

Aims

Electrical reconnection of pulmonary veins (PVs) is considered an important determinant of recurrent atrial fibrillation (AF) after pulmonary vein isolation (PVI). To date, AF recurrences almost automatically trigger invasive repeat procedures, required to assess PVI durability. With recent technical advances, it is becoming increasingly common to find all PVs isolated in those repeat procedures. Thus, as ablation of extra-PV targets has failed to show benefit in randomized trials, more and more often these highly invasive procedures are performed only to rule out PV reconnection. Here we aim to define the ability of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE)-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out PV reconnection non-invasively.

Methods and results

This study is based on a prospective registry in which all patients receive an LGE-MRI after AF ablation. Included were all patients that—after an initial PVI and post-ablation LGE-MRI—underwent an invasive repeat procedure, which served as a reference to determine the predictive value of non-invasive lesion assessment by LGE-MRI.: 152 patients and 304 PV pairs were analysed. LGE-MRI predicted electrical PV reconnection with high sensitivity (98.9%) but rather low specificity (55.6%). Of note, LGE lesions without discontinuation ruled out reconnection of the respective PV pair with a negative predictive value of 96.9%, and patients with complete LGE lesion sets encircling all PVs were highly unlikely to show any PV reconnection (negative predictive value: 94.4%).

Conclusion

LGE-MRI has the potential to guide selection of appropriate candidates and planning of the ablation strategy for repeat procedures and may help to identify patients that will not benefit from a redo-procedure if no ablation of extra-PV targets is intended.

Keywords: Durability of pulmonary vein isolation, Pulmonary vein reconnection, Late gadolinium enhancement, Cardiac MRI, Non-invasive ablation lesion assesment, Atrial fibrillation, Catheter ablation

What’s new?

Non-invasive lesion assessment by post-ablation late gadolinium enhancement (LGE)-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) predicts pulmonary vein (PV) isolation durability with high specificity but somewhat lower sensitivity.

LGE-MRI can reliably rule out PV reconnection with a negative predictive value of 97%.

Patients with complete LGE lesions encircling all four PVs may not benefit from repeat invasive procedures, if ablation of extra-PV targets is not intended.

LGE-MRI has a clear potential to guide selection of appropriate candidates and planning of the ablation strategy for repeat procedures and may help to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures with all their associated risks and costs.

Introduction

Electrical reconnection of pulmonary veins (PVs) is considered an important determinant of recurrent atrial fibrillation (AF) after pulmonary vein isolation (PVI).1 To date, an invasive repeat procedure is required to assess durability of PVI. Against this background, in most centres clinically relevant AF recurrences almost automatically trigger repeat ablation procedures aiming at PV re-isolation.2,3 However, technological and procedural advances have substantially improved efficacy of catheter ablation.4–10 As a result, it is becoming increasingly common to find all four PVs isolated in those repeat procedures.11 Thus, as ablation of extra-PV targets has failed to show benefit in large randomized trials, more and more often these highly invasive procedures are being performed only to confirm durable PVI.3

Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE)-magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the only non-invasive method to assess ablation lesions. While the ability of LGE-MRI to localize functional gaps in ablation lesions after PVI has been investigated in a number of small studies, its predictive value regarding PVI durability and PV reconnection, respectively, has not been specifically defined.12–20 Here we aim to determine the ability of LGE-MRI to rule out PV reconnection and its potential to guide patient selection for repeat ablation procedures.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was an observational, retrospective analysis of a prospective patient registry conducted at the Arrhythmia Section of Hospital Clínic, University of Barcelona. All patients scheduled for AF ablation enter this registry and receive an LGE-MRI within 4 days prior to ablation, as well as 3 months after ablation. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the local research ethics committee, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

All patients from the registry that had undergone a repeat invasive procedure after an initial AF ablation with complete PVI were eligible and included in the analyses if the post-index ablation LGE-MRI was of sufficient quality. The ability of LGE-MRI to determine PVI durability and PV reconnection, respectively, was then investigated using invasive mapping during the subsequent repeat procedure as a reference.

Late gadolinium enhancement-magnetic resonance image acquisition

LGE-MRI was performed as previously described.12 In brief, MRI studies were performed in sinus rhythm using one of two different 3-Tesla scanners (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany and Signa Architect, General Electric, Chicago, Illinois, USA), both with 32-channel phase array cardiovascular coils.

Inversion recovery prepared T1-weighted gradient echo sequences were acquired in axial orientation using electrocardiogram gating and a free-breathing 3D navigator, 20 min after administering an intravenous bolus of 0.2 mmol/kg of gadobutrol (Gadovist, Bayer Hispania).

Sequence parameters for magnetom prisma scanner (Siemens Healthineers)

Repetition time 2.3 ms, echo time 1.4 ms, flip angle 11°, bandwidth 460 Hz/pixel, and inversion time (TI) 280–380 ms, acquired voxel size 1.25 × 1.25 × 2.5 mm.

Sequence parameters for signa architect scanner (general electric)

Repetition time 6.4 ms, echo time 2.2 ms, flip angle 20°, bandwidth 244 Hz/pixel, acquired voxel size 1.25 × 1.25 × 2.4 mm.

A TI scout sequence was used in order to determine the optimal TI that nullified the left ventricular myocardial signal (typically 280–380 ms).

Late gadolinium enhancement-magnetic resonance imaging post-processing

LGE-MRI post-processing was performed by two highly experienced experts (E.F. and P.G.), blinded to data from invasive mapping, using ADAS 3D software (Adas3D Medical SL). For semiautomatic 3D reconstruction of left atria and PVs, the atrial wall was manually traced on each axial-plane slice and automatically adjusted to built a 3D shell.

LGE was quantified in a standardized manner based on voxel signal intensities relative to the mean blood pool signal intensity, applying a previously validated signal intensity ratio threshold of ≥1.2 to define LGE indicative of fibrotic tissue.12,21 The 3D reconstructions were colour-coded accordingly, and an LGE discontinuation of ≥3 mm was considered indicative of PV reconnection (previous studies from our group suggest that LGE discontinuations of <3 mm may not be relevant for clinical outcome and that consideration only of LGE discontinuations ≥3 mm does not significantly lower the sensitivity in the detection of gaps).12,22

Invasive assessment of pulmonary vein isolation

For validation, PVI durability was determined based on the subsequent invasive repeat procedures taking into account all available information including electroanatomical mapping and local bipolar PV electrograms. Electrical PV reconnections were defined based on the presence of local PV electrograms recorded by the multipolar mapping catheter without application of a specific voltage threshold. Invasive assessment of PVI was performed exclusively with the following multipolar mapping catheters: LassoNav™ and PentaRay™ (both Biosense Webster Inc.), IntellaMap Orion™ (Boston Scientific Inc.) or AdvisorTM HD Grid (Abbott, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed using SPSS 28.0 software (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range), unless otherwise specified. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive, as well as negative predictive value of LGE-MRI were determined with respect to PV reconnection as determined by invasive assessment. In addition, the agreement between the two methods was analysed by calculating Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ) for inter-rater reliability based on the presence or absence of gaps in LGE-MRI using invasive mapping as a reference. A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Screening and baseline characteristics

Of the 1262 patients in the AF ablation registry screened, a total of 159 patients had undergone a post-ablation LGE-MRI and a subsequent invasive repeat procedure. Seven patients (4.4%) had to be excluded because of insufficient MRI quality. Thus, total of 152 patients with PVI index ablation procedure performed between October 2010 and December 2020, were included in the analysis. Patient and procedural characteristics are displayed in Tables 1 and 2. In the vast majority of patients a PVI-only approach was followed and performed by point-by-point radiofrequency ablation. Of note, contact force-sensing catheters were used by default from 2013 onwards, whereas index-guided ablation according to the CLOSE-protocol was introduced in 2018.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Parameter | n = 152 |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 57.0 ± 10.7 |

| Female gender | 45 (29.6) |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 1.4 ± 1.1 |

| AF type prior to index PVI | |

| ȃParoxysmal AF | 62 (41) |

| ȃPersistent AF | 90 (59) |

| Recurrent arrhythmia type triggering repeat procedure | |

| ȃParoxysmal AF | 47 (31) |

| ȃPersistent AF | 68 (45) |

| ȃAT/flutter | 37 (24) |

| Left atrial diameter, mm | 42.5 ± 6.4 |

| Left atrial volume index, mL/m2 | 39.9 ± 7.3 |

| LVEF, % | 55.7 ± 8.6 |

| Congestive heart failure | 18 (12) |

| Systemic hypertension | 77 (51) |

| Diabetes | 16 (11) |

All values are n, (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

Table 2.

Index ablation procedural characteristics

| Parameter | n = 152 |

|---|---|

| Complete pulmonary vein isolation | 152 (100) |

| Additional extra-PV ablation | 10 (7) |

| ȃPosterior wall isolation (box lesion) | 7 (5) |

| ȃMitral isthmus line | 2 (1) |

| ȃLGE-MRI-based fibrosis ablation | 2 (1) |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 128 (84) |

| Cryoballoon ablation | 24 (16) |

All values are n, (%).

Per-pulmonary vein pair analysis

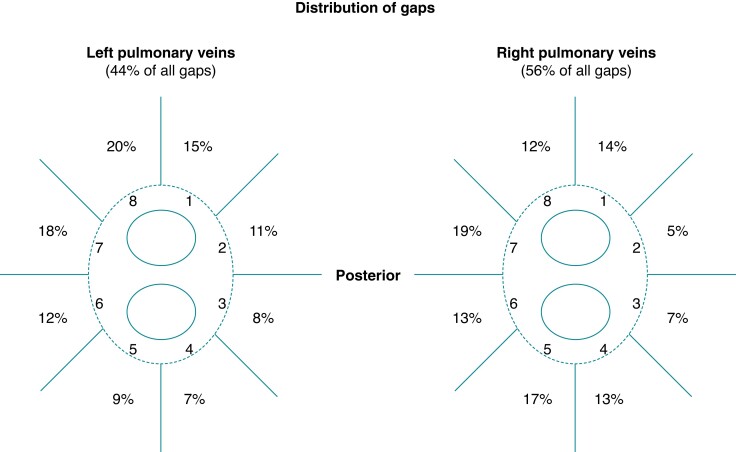

Post-ablation LGE lesions of 304 PV pairs from 152 patients were analysed and validated based on subsequent invasive repeat procedures. The distribution of gaps is displayed in Figure 1. LGE-MRI predicted PV reconnection with high sensitivity (98.9%), whereas specificity was rather low (55.6%) (Table 3). The agreement between LGE-MRI and invasive assessment of PVI regarding the presence or absence of gaps in a given PV pair was moderate to good (Cohen’s kappa coefficients for inter-rater reliability between 0.56 and 0.61). Of note, complete circumferential LGE lesions without discontinuation were encountered in 64 PV pairs (21.1%) and ruled out electrical reconnection of the respective PV pair with a negative predictive value of 96.9% (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Distribution of LGE gaps. Proportion of LGE discontinuities in left vs. right PV pairs and according to PV segments.

Table 3.

Predictive value regarding PV reconnection—per-PV pair analysis

| Left PVs | Right PVs | Left and right PVs | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 98.8 (83/84) | 99.0 (104/105) | 98.9 (187/189) |

| Specificity | 60.3 (41/68) | 48.9 (23/47) | 55.6 (64/115) |

| Positive predictive value | 75.5 (83/110) | 81.3 (104/128) | 78.6 (187/238) |

| Negative predictive value | 97.6 (41/42) | 95.8 (23/24) | 96.9 (64/66) |

| Agreement (kappa) | 0.61* | 0.56* | 0.59* |

Percentages (n-numbers); *P < 0.0001.

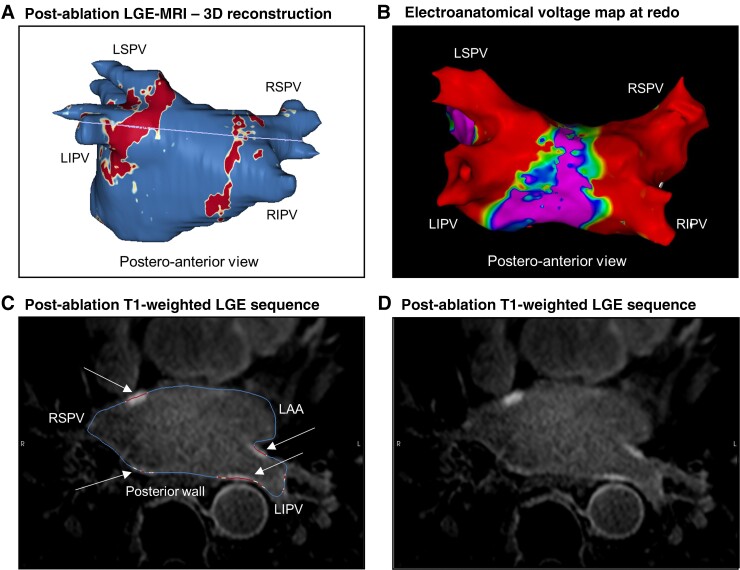

Figure 2.

Complete LGE lesion set and durable PVI—representative case. (A) 3D reconstruction of left atrium and PVs 3 months after index PVI with colour coding based on signal intensity ratios applying thresholds for fibrotic tissue (yellow ≥1.2; red >1.32) using ADAS 3D software (Adas3D Medical Barcelona, Spain). The purple line indicates the plane of the LA slices in the lower panel (C&D). (B) Postero-anterior view of electroanatomical voltage map of the same left atrium and PVs in a subsequent repeat invasive procedure (24 months after index PVI) applying voltage thresholds of 0.1 and 0.5 mV, respectively. (C) Overlay of the T1-weighted image with the LGE colour coding described previously. White arrows point to local ablation-induced LGE lesions at the PV ostial walls. (D) T1-weighted raw image without overlay. LIPV, left inferior pulmonary vein; LSPV, left superior pulmonary vein; RSPV, right superior pulmonary vein; RIPV, right inferior pulmonary vein; LAA, left atrial appendage.

Per-patient analysis

The per-patient analysis yielded similar results with very high sensitivity of LGE-MRI regarding the detection of PV reconnection, but a rather low specifity and thus only moderate agreement with invasive assessment of PVI according to Cohen’s kappa coefficient for inter-rater reliability (Table 4). While durable PVI was encountered in 22% of the patients according to invasive assessment, only 11% of the patients displayed complete LGE lesion sets encircling all four PVs. Of note, only one patient with a complete LGE lesion set showed electrical PV reconnection in the invasive repeat procedure, corresponding to a negative predictive value of 94.4%.

Table 4.

Predictive value regarding PV reconnection—per-patient analysis

| Sensitivity | 99.1% (116/117) |

| Specificity | 48.6% (17/35) |

| Positive predictive value | 86.6% (116/134) |

| Negative predictive value | 94.4% (17/18) |

| Agreement (kappa) | 0.58* |

Percentages (n-numbers); *P < 0.0001.

Discussion

This retrospective study investigated the accuracy of LGE-MRI to non-invasively determine PVI durability in 152 patients and 304 PV pairs, respectively, using subsequent invasive repeat procedures as a reference.

Late gadolinium enhancement-magnetic resonance imaging can rule out pulmonary vein reconnection with a high negative predictive value

These data demonstrate that the absence of LGE discontinuities is highly predictive of durable PVI, and patients with complete LGE lesions encircling the PVs are unlikely to present PV reconnection (negative predictive value 94.4%). In those patients the potential benefit of a repeat invasive procedure might be questionable and should be carefully reconsidered, taking a personalized approach with non-PV targets into account.

This is of increasing relevance as indeed, with recent technical advances, it is becoming increasingly common to find all PVs isolated in repeat procedures.11 Thus, as ablation of extra-PV targets has failed to show benefit in large randomized trials, more and more often these highly invasive procedures are being performed only to confirm durable PVI—or even worse, investigators might feel obliged to target extra-PV structures, only to justify the invasive procedure.23

Standardized post-processing method

A particular strength of this study is the standardized post-processing method to define ablation lesions, which is investigator-independent and therefore readily reproducible.24 As T1-weighted imaging is based on signal intensity contrast rather than directly measured absolute values, for standardization LGE must be defined by a signal intensity threshold relative to an internal reference. Obviously, different internal references and/or thresholds applied to the same images will inevitably yield different sensitivities and specificities in the detection of fibrotic tissue.25,26 One of the limitations that hampered the widespread use of LGE-MRI for atrial fibrosis and lesion assessment in the past has been the lack of standardization and thus reproducibility.

Against this background, our group has recently established a method quantifying local signal intensity ratios using the mean signal intensity of the blood pool as a reference for normalization (signal intensity of each given voxel/mean signal intensity of the blood).21 Thresholds to define fibrotic tissue (signal intensity ratio >1.2) or dense scar (signal intensity ratio >1.32) in the atrium were derived from comparisons of distinct cohorts of young healthy individuals and post-AF ablation patients, and subsequently validated in numerous clinical studies with respect to electroanatomical voltage mapping, as well as procedural and clinical endpoints.12,19,22,27 These uniform definitions for signal intensity thresholds and internal references render this method universally applicable irrespective of the centre and independent of the investigator, allowing for a widespread clinical use. However, it shall be emphasized that various other methods using distinct internal references and thresholds have been validated by other groups.14,16,28,29 Moreover, it shall be stressed that sufficient image quality is an important prerequisite. Of note, image acquisition during AF is challenging and may result in insufficient image quality. Therefore image acquisition during sinus rhythm is recommended.

Proportion of complete late gadolinium enhancement lesions

In line with previous reports, the proportion of patients with complete LGE lesions encircling the PVs was rather low in this study.13,30 However, it has to be considered that the selection of patients based on clinically indicated invasive repeat procedures introduces a substantial bias in this regard. It is also noteworthy that the majority of the index PVI procedures in this cohort were performed before the introduction of index-guided ablation following the CLOSE-protocol, and the proportion of repeat procedures showing complete isolation of all four PVs (22%) is also consistent with previous reports of comparable cohorts.11 In fact, the recent advent of standardized index-guided ablation approaches has raised this proportion substantially with durable PVI being encountered in up to 60% of the repeat procedures.11 However, to some extent, limitations in the detection of ablation-induced fibrosis are likely to contribute to the low proportion of complete LGE lesion sets.

False positive late gadolinium enhancement-predicted pulmonary vein reconnections

The fact that a substantial proportion of PV pairs with LGE discontinuities showed no electrical reconnection based on invasive mapping, likely reflects a partial failure of LGE-MRI to detect local ablation-induced scarring. Of note, this was despite application of a relatively low threshold defining LGE. In fact, in a recent study using electroanatomical mapping as a reference, we found that application of this lower of the two previously established and validated thresholds (signal intensity ratio >1.2) augmented sensitivity in the detection of ablation lesions while preserving specificity.12 This was confirmed in the current study, where specificity in the detection of lesions (and thus sensitivity in the detection of PV reconnections) was extremly high despite using this lower threshold.

Previous data indicate that detectability of ablation lesions also depends on the timing of the image acquisition and can be improved accordingly. In fact, detectability of definite ablation lesions appears to be better and more accurate at 3 months post-ablation than at chronic stages (>12 months post-ablation).12 However, it is important to note that acute and subacute LGE lesions (<2 months post-ablation), at least in part reflect a transient inflammatory response, which usually resolves within the first 1–2 months following ablation, rather than definite scar formation.31,32

Finally, it also has to be taken into account that ‘false positive’ LGE discontinuities, may indicate true anatomical gaps in the ablation lesion that coincide with sites of dormant conduction or non-conductive tissue and therefore do not result in evident electrical PV reconnection.

Conclusion

Taken together, non-invasive ablation lesion assessment by LGE-MRI can rule out PV reconnection with a high negative predictive value. Therefore, it has the potential to guide selection of appropriate candidates and planning of the ablation strategy for repeat procedures, and may help to improve success rates and to avoid unnecessary procedures with all their associated risks and costs.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Carolina Sanroman, Eulalia Ventura, and Neus Portella for their excellent administrative support.

Contributor Information

David Padilla-Cueto, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Elisenda Ferro, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Paz Garre, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Susanna Prat, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Jean-Baptiste Guichard, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Department of Cardiology, University Hospital of Saint-Étienne, 42055 Saint-Étienne, France.

Rosario J Perea, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain.

Jose Maria Tolosana, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Eduard Guasch, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Elena Arbelo, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Andreu Porta-Sanchéz, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Ivo Roca-Luque, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Marta Sitges, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Josep Brugada, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Lluís Mont, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Cardiovascular (CIBERCV), 28029 Madrid, Spain.

Till F Althoff, Atrial Fibrillation Unit, Department of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute (ICCV), CLÍNIC—University Hospital Barcelona, C/Villarroel N° 170, 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), 08036 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain; Department of Cardiology and Angiology, Charité—University Medicine Berlin, Charité Campus Mitte, Charitéplatz 1, 10117 Berlin, Germany; DZHK (German Centre for Cardiovascular Research), partner site Berlin, 10117 Berlin, Germany.

Funding

This work is supported in part by grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Government, Madrid, Spain [FIS_PI16/00435—FIS_CIBER16]; Fundació la Marató de TV3, Catalonia, Spain [N° 20152730].

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Ouyang F, Antz M, Ernst S, Hachiya H, Mavrakis H, Deger FTet al. . Recovered pulmonary vein conduction as a dominant factor for recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmias after complete circular isolation of the pulmonary veins: lessons from double lasso technique. Circulation 2005;111:127–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist Cet al. . 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association of cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gupta D. Noninvasive assessment of durability of ablation lesions with magnetic resonance imaging: are we there yet? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:2582–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andrade JG, Wells GA, Deyell MW, Bennett M, Essebag V, Champagne Jet al. . Cryoablation or drug therapy for initial treatment of atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2021;384:305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chinitz LA, Melby DP, Marchlinski FE, Delaughter C, Fishel RS, Monir Get al. . Safety and efficiency of porous-tip contact-force catheter for drug-refractory symptomatic paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation: results from the SMART SF trial. Europace 2018;20:f392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Das M, Loveday JJ, Wynn GJ, Gomes S, Saeed Y, Bonnett LJet al. . Ablation index, a novel marker of ablation lesion quality: prediction of pulmonary vein reconnection at repeat electrophysiology study and regional differences in target values. Europace 2017;19:775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Duytschaever M, Vijgen J, De Potter T, Scherr D, Van Herendael H, Knecht Set al. . Standardized pulmonary vein isolation workflow to enclose veins with contiguous lesions: the multicentre VISTAX trial. Europace 2020;22:1645–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Natale A, Reddy VY, Monir G, Wilber DJ, Lindsay BD, McElderry HTet al. . Paroxysmal AF catheter ablation with a contact force sensing catheter: results of the prospective, multicenter SMART-AF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:647–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reddy VY, Dukkipati SR, Neuzil P, Natale A, Albenque JP, Kautzner Jet al. . Randomized, controlled trial of the safety and effectiveness of a contact force-sensing irrigated catheter for ablation of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: results of the TactiCath contact force ablation catheter study for atrial fibrillation (TOCCASTAR) study. Circulation 2015;132:907–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Taghji P, El Haddad M, Phlips T, Wolf M, Knecht S, Vandekerckhove Yet al. . Evaluation of a strategy aiming to enclose the pulmonary veins with contiguous and optimized radiofrequency lesions in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: A pilot study. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2018;4:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. De Pooter J, Strisciuglio T, El Haddad M, Wolf M, Phlips T, Vandekerckhove Yet al. . Pulmonary vein reconnection No Longer occurs in the majority of patients after a single pulmonary vein isolation procedure. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Althoff TF, Garre P, Caixal G, Perea R, Prat S, Tolosana JMet al. . Late gadolinium enhancement-MRI determines definite lesion formation most accurately at 3 months post ablation compared to later time points. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2022;45:72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Badger TJ, Daccarett M, Akoum NW, Adjei-Poku YA, Burgon NS, Haslam TSet al. . Evaluation of left atrial lesions after initial and repeat atrial fibrillation ablation: lessons learned from delayed-enhancement MRI in repeat ablation procedures. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010;3:249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harrison JL, Sohns C, Linton NW, Karim R, Williams SE, Rhode KSet al. . Repeat left atrial catheter ablation: cardiac magnetic resonance prediction of endocardial voltage and gaps in ablation lesion sets. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8:270–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hunter RJ, Jones DA, Boubertakh R, Malcolme-Lawes LC, Kanagaratnam P, Juli CFet al. . Diagnostic accuracy of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the detection and characterization of left atrial catheter ablation lesions: a multicenter experience. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2013;24:396–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jefairi NA, Camaioni C, Sridi S, Cheniti G, Takigawa M, Nivet Het al. . Relationship between atrial scar on cardiac magnetic resonance and pulmonary vein reconnection after catheter ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2019;30:727–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kurose J, Kiuchi K, Fukuzawa K, Takami M, Mori S, Suehiro Het al. . Lesion characteristics between cryoballoon ablation and radiofrequency ablation with a contact force-sensing catheter: late-gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging assessment. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2020;31:2572–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mont L, Roca-Luque I, Althoff TF. Ablation lesion assessment with MRI. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 2022;11:e02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Quinto L, Cozzari J, Benito E, Alarcón F, Bisbal F, Trotta Oet al. . Magnetic resonance-guided re-ablation for atrial fibrillation is associated with a lower recurrence rate: a case-control study. Europace 2020;22:1805–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spragg DD, Khurram I, Zimmerman SL, Yarmohammadi H, Barcelon B, Needleman Met al. . Initial experience with magnetic resonance imaging of atrial scar and co-registration with electroanatomic voltage mapping during atrial fibrillation: success and limitations. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:2003–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Benito EM, Carlosena-Remirez A, Guasch E, Prat-Gonzalez S, Perea RJ, Figueras Ret al. . Left atrial fibrosis quantification by late gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance: a new method to standardize the thresholds for reproducibility. Europace 2017;19:1272–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Linhart M, Alarcon F, Borras R, Benito EM, Chipa F, Cozzari Jet al. . Delayed gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging detected anatomic gap length in wide circumferential pulmonary vein ablation lesions is associated with recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2018;11:e006659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Verma A, Jiang CY, Betts TR, Chen J, Deisenhofer I, Mantovan Ret al. . Approaches to catheter ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1812–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Margulescu AD, Nunez-Garcia M, Alarcon F, Benito EM, Enomoto N, Cozzari Jet al. . Reproducibility and accuracy of late gadolinium enhancement cardiac magnetic resonance measurements for the detection of left atrial fibrosis in patients undergoing atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. Europace 2019;21:724–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Eichenlaub M, Mueller-Edenborn B, Minners J, Figueras IVRM, Forcada BR, Colomer AVet al. . Comparison of various late gadolinium enhancement magnetic resonance imaging methods with high-definition voltage and activation mapping for detection of atrial cardiomyopathy. Europace 2022;24(Suppl):euac053.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hopman LHGA, Bhagirath P, Mulder MJ, Eggink IN, van Rossum AC, Allaart CPet al. . Quantification of left atrial fibrosis by 3D late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation: impact of different analysis methods. European Heart Journal—Cardiovascular Imaging 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bisbal F, Guiu E, Cabanas-Grandio P, Berruezo A, Prat-Gonzalez S, Vidal Bet al. . CMR-guided approach to localize and ablate gaps in repeat AF ablation procedure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:653–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oakes RS, Badger TJ, Kholmovski EG, Akoum N, Burgon NS, Fish ENet al. . Detection and quantification of left atrial structural remodeling with delayed-enhancement magnetic resonance imaging in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2009;119:1758–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khurram IM, Beinart R, Zipunnikov V, Dewire J, Yarmohammadi H, Sasaki Tet al. . Magnetic resonance image intensity ratio, a normalized measure to enable interpatient comparability of left atrial fibrosis. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:85–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Akoum N, Wilber D, Hindricks G, Jais P, Cates J, Marchlinski Fet al. . MRI Assessment of ablation-induced scarring in atrial fibrillation: analysis from the DECAAF study. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2015;26:473–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Badger TJ, Oakes RS, Daccarett M, Burgon NS, Akoum N, Fish ENet al. . Temporal left atrial lesion formation after ablation of atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2009;6:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ghafoori E, Kholmovski EG, Thomas S, Silvernagel J, Angel N, Hu Net al. . Characterization of gadolinium contrast enhancement of radiofrequency ablation lesions in predicting edema and chronic lesion size. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2017;10:e005599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.