Abstract

Aims

The safety and feasibility of combining percutaneous catheter ablation (CA) for atrial fibrillation with left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) as a single procedure in the USA have not been investigated. We analyzed the US National Readmission Database (NRD) to investigate the incidence of combined LAAO + CA and compare major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) with matched LAAO-only and CA-only patients.

Methods and results

In this retrospective study from NRD data, we identified patients undergoing combined LAAO and CA procedures on the same day in the USA from 2016 to 2019. A 1:1 propensity score match was performed to identify patients undergoing LAAO-only and CA-only procedures. The number of LAAO + CA procedures increased from 28 (2016) to 119 (2019). LAAO + CA patients (n = 375, mean age 74 ± 9.2 years, 53.4% were males) had non-significant higher MACE (8.1%) when compared with LAAO-only (n = 407, 5.3%) or CA-only patients (n = 406, 7.4%), which was primarily driven by higher rate of pericardial effusion (4.3%). All-cause 30-day readmission rates among LAAO + CA patients (10.7%) were similar when compared with LAAO-only (12.7%) or CA-only (17.5%) patients. The most frequent primary reason for readmissions among LAAO + CA and LAAO-only cohorts was heart failure (24.6 and 31.5%, respectively), while among the CA-only cohort, it was paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (25.7%).

Conclusion

We report an 63% annual growth (from 28 procedures) in combined LAAO and CA procedures in the USA. There were no significant difference in MACE and all-cause 30-day readmission rates among LAAO + CA patients compared with matched LAAO-only or CA-only patients.

Keywords: LAAO – Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion, CA – Percutaneous Catheter-directed Atrial Fibrillation Ablation, MACE – Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, NRD – National Readmission Database

What's new?

In the USA, simultaneous percutaneous LAAO and catheter-directed ablation of AF at the same time are not only being performed successfully but also have noticed an approximately 60% annual increase in the incidence between 2016 and 2019.

Among patients undergoing combined LAAO + CA procedure, 8% experienced MACE during procedural hospitalization, while 11% had all-cause 30-day readmission, which was not significantly different when compared with propensity score-matched LAAO-only or CA-only cohorts.

Compared to the LAAO-only cohort, paroxysmal AF significantly predicted MACE among the LAAO + CA cohort.

The most frequent reason for readmission among the LAAO + CA cohort was heart failure, while paroxysmal AF was among the matched LAAO-only or CA-only cohorts.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) management is a two-pronged approach to attaining rate- or rhythm control and preventing stroke. AF catheter ablation has a Class I recommendation for rhythm control in the 2020 ESC1 and 2014 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society (ACC/AHA/HRS)2 guidelines among patients who failed, or are intolerant to, class I or III antiarrhythmic drugs. Catheter-directed AF ablation (CA) has gained significant interest as a first-line rhythm control strategy over antiarrhythmic medications, especially in patients with paroxysmal or recent-onset AF, as evidenced by major randomized control trials including RAAFT, MANTRA-PAF and CASTLE-AF, in which, patients undergoing CA were found to have lower mortality, less recurrence of AF, and better quality-of-life.3,4

Similarly, the use of left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) devices, such as the Watchman® device (Boston Scientific) and the Amulet® device (Abbott), has increased significantly in the USA5 with lower in-hospital mortality and rehospitalization rates compared with matched AF cohorts.6–8 LAAO is proven to reduce haemorrhagic stroke risk when compared with warfarin among non-valvular AF patients.9–12 Combining AF ablation and implantation of LAAO device is expected to provide additive benefits in non-pharmacologic AF management. This ‘one-stop’ combination procedure has gained popularity worldwide.13 Multicentre parallel LAAO registries from Europe, the Middle East, Russia, Asia, and Australia have suggested that the combined procedure is feasible and safe.14 However, there is a paucity of such studies on the US patient population and this information is essential since the USA is one of the nations with the highest prevalence of AF [>900 per 100 000 individuals (age-standardized prevalence in 2016)].1

In this study, we assess the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) among patients undergoing combined AF ablation and LAAO procedures compared with patients having either individual procedure using a multi-institutional, US representative patient population database.

Methods

Database source

The National Readmission Database (NRD), a de-identified, all-payer, publicly available, in-hospital patient care database, was utilized in the study. The NRD is a part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) which is sponsored by the Agency of Health Research and Quality. The NRD is generated annually from 28 participating State Inpatient Databases (SID). This collectively represents approximately 60% of the US resident population and 58% of all US hospitalizations.15 NRD provides a patient-specific encrypted linkage number (NRD_VisitLink) that is created using the date of birth and sex to help track each patient across hospitals for that calendar year. This is used in tandem with another variable (NRD_DaysToEvent) which provides the number of days between each consecutive hospitalization. In this dataset, each patient's events are captured at the end of hospitalization in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM), and Procedure (ICD-10-PCS) codes. As all the data are de-identified to protect patients, physicians, and hospital privacy and since we accessed the data in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 and HCUP data reporting guidelines, this study was considered exempt from the Institutional Review Boards approval. NRD dataset is limited to only those who have completed the data usage agreement with HCUP; therefore, we are unable to share the data publicly.

Study cohort and study design

We included all the patients in the NRD between 1 January 2016 and 31 December 2019 with complete data for age ≥18 years and death. Initially, all patients undergoing in-hospital percutaneous LAAO procedure and percutaneous catheter-directed AF ablation (CA) were identified using ICD-10-PCS codes. Subsequently, patients hospitalized primarily for AF were identified using ICD-10-CM codes and then those undergoing AF ablation were extracted. The ICD-10 codes utilized in this study have been summarized in Supplementary material online, Table S1.

In this study, we clustered the patient population into three cohorts: (i) patients undergoing LAAO + CA, (ii) LAAO-only, and (iii) CA-only. Among each subgroup, we excluded patients diagnosed with other tachyarrhythmias such as re-entry ventricular arrhythmias, supraventricular tachycardia, ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, ventricular flutter, atrial premature depolarization, ventricular premature depolarization, and junctional premature depolarization. This methodology of identifying patients undergoing LAAO implantation and catheter-directed AF ablation from administrative databases has been adopted and validated in previous studies.5,6 Our population of interest were patients undergoing LAAO + CA on the same day: therefore, patients undergoing LAAO or CA on different days during the same hospitalization were excluded (unweighted n = 23). Additionally, patients hospitalized in December were excluded (unweighted n = 78). Since NRD captures data annually, 30-day readmissions, if they occurred during the following year, would not be represented. The study design is summarized as a flowchart in Supplementary material online, Figure S1.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was to assess the incidence of the combined LAAO + CA in the USA, in addition to assessing MACE. In this study, MACE is defined as a patient diagnosed with pericardial effusion and or requiring pericardiocentesis, or major bleeding (patient undergoing blood transfusion) or experiencing a stroke or transient ischaemic attack or in-hospital death. These individual constituents of MACE were identified using ICD-10-CM and ICD-10-PCS codes as summarized in the Supplementary material online, Table S1. We also assessed all-cause 30-day readmission after index LAAO + CA procedural hospitalization. Secondarily, we assessed disposition and length of stay during the index hospitalization, MACE and cardioversion during readmission, readmission length of stay, and hospitalization cost. We also queried the most common (frequency ≥5%) primary diagnosis during readmission hospitalization.

Statistical analyses

Patient demographic variables such as age, gender, Elixhauser comorbidity index (ECI), a composite of 31 comorbidities, and hospital demographics were categorized by the type of procedure performed and compared using the Pearson2 test. Continuous variables that were normally distributed are presented as mean (standard deviation), while skewed data are presented as median (interquartile range) and compared by one-way analysis of variance. Continuous variables, such as age, ECI and CHA2DS2-VASc score, were converted to categorical variables and introduced into modelling as we chose to avoid linearity assumptions.

Once the LAAO + CA group was recognized, a propensity score match was performed to identify identical patients who had undergone only LAAO or CA. Age, gender and CHA2DS2-VASc score (including a quadratic variable for the latter two) were introduced into the regression model used to fit the propensity score. The matching algorithm was performed using a 1:1 nearest neighbor match, without replacement with a 10% matching caliper for the estimated propensity scores’ standard deviation. To test for matching accuracy, standardized mean difference (including variance) and kernel density plots were analyzed and presented in Supplementary material online, Tables S4 and S5; Supplementary material online, Figures S7 and S8, respectively.

Multivariable logistic regression analysis for gender, type of AF, type of insurance provider and clustered age, CHA2DS2-VASc score, and ECI was performed to analyze the measure of association with MACE. Univariable unadjusted logistic regression analysis with each component of ECI was also performed to explore the association of individual comorbidity with MACE. We also performed Kaplan-Meier Cox proportional hazard model to measure the association between each study cohort and time-to-readmission within 30 days. Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the difference in MACE among the LAAO + CA group (study group that had the combined procedures on the same) with those who had the combined procedure on different days but during the same hospitalization. All the analyses accounted for the complex survey design of NRD and to comply with the HCUP data reporting guidelines and any variable with n < 10 was omitted. A two-sided significance level of P < 0.05 was considered significant. All the analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics, version 27.0 (IBM Corp.), and STATA version 16.1 (Stata Corp. LP).

Results

Demographics and comorbidities

In the USA, during the study period of four consecutive calendar years (2016–2019), we identified a total study cohort of 1189 (unweighted n = 690) patients, among which the LAAO + CA cohort consisted of 375 (unweighted n = 225) patients. After matching by propensity score, we identified 407 (unweighted n = 231) LAAO-only patients and 406 (unweighted n = 234) CA-only patients.

Among patients with LAAO + CA (n = 375), the mean age was 74 ± 9.2 years, 53.4% were males, and 85.7% were admitted electively. The majority had paroxysmal AF (49.1%), followed by persistent AF (32.6%) and chronic AF (12.5%). The mean CHA2DS2-VASc score was 3.8 ± 1.3, with 94.1% having a score ≥2 (high risk). Hypertension (83.2%), congestive heart failure (39.7%), diabetes (29.6%), renal failure (23.2%), and valvular heart disease (21.3%) were some of the most frequent comorbidities in this cohort.

Among the matched LAAO-only and CA-only cohorts, the mean age was 74 ± 8.7 years and 74 ± 9.2 years, respectively. The majority were males (52.8 and 54.1%) diagnosed most commonly with paroxysmal AF (54 and 53.1%) and with a high risk (≥2) CHA2DS2-VASc score (95.7 and 94.4%), respectively. Compared with the CA-only cohort, the LAAO-only cohort had significantly higher index elective hospitalization (93.7 vs. 50.2%, P < 0.001), suggesting LAAO-associated hospitalization was mostly a planned admission. In both groups, hypertension was most common (83.5 and 81.1%, P = 0.606), followed by congestive heart failure (29.2 and 50.2%, P = 0.004), and diabetes (34 and 24.6%, P = 0.1). Among various ECI during the index hospitalization, the distribution of clinically relevant comorbidities in our study, among the three study cohorts, was not significantly different, in particular, blood loss anaemia. Demographics and comorbidities of the study population have been summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study

| Covariates | Total (n = 1189) | LAAO and CA (n = 375) | LAAO only (n = 407) | CA only (n = 406) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (clustered) | |||||||||

| ȃ18–54 years | 31 | (2.6%) | 10 | (2.8%) | < 10 | 11 | (2.8%) | 0.9998 | |

| ȃ55–64 years | 106 | (9.0%) | 34 | (9.1%) | 33 | (8.1%) | 39 | (9.7%) | |

| ȃ65–74 years | 440 | (37.0%) | 141 | (37.5%) | 152 | (37.4%) | 147 | (36.2%) | |

| ȃ75–84 years | 476 | (40.1%) | 150 | (39.9%) | 167 | (40.9%) | 160 | (39.4%) | |

| ȃ> = 85 years | 135 | (11.4%) | 41 | (10.8%) | 46 | (11.3%) | 49 | (11.9%) | |

| Male | 635 | (53.4%) | 201 | (53.4%) | 215 | (52.8%) | 220 | (54.1%) | 0.9763 |

| Atrial fibrillation | |||||||||

| ȃParoxysmal | 622 | (52.3%) | 184 | (49.1%) | 221 | (54.4%) | 216 | (53.1%) | 0.6468 |

| ȃPersistent | 364 | (30.6%) | 122 | (32.6%) | 78 | (19.3%) | 163 | (40.1%) | 0.0024 |

| ȃLongstanding Persistent | < 10 | a | a | < 10 | 0.7068 | ||||

| ȃChronic | 177 | (14.9%) | 47 | (12.5%) | 91 | (22.3%) | 40 | (9.7%) | 0.0118 |

| ȃPermanent | 11 | (0.9%) | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.4465 | |||

| ȃUnspecified | 118 | (9.9%) | 42 | (11.3%) | 27 | (6.7%) | 48 | (11.9%) | 0.2438 |

| Elixhauser comorbidity index (clustered) | |||||||||

| ȃECI 0–1 | 50 | (4.2%) | 16 | (4.4%) | 22 | (5.3%) | 12 | (2.9%) | 0.3945 |

| ȃECI 2–3 | 434 | (36.5%) | 141 | (37.6%) | 161 | (39.7%) | 132 | (32.4%) | |

| ȃECI 4–5 | 440 | (37.0%) | 139 | (37.0%) | 152 | (37.3%) | 149 | (36.7%) | |

| ȃECI > = 6 | 264 | (22.2%) | 79 | (21.0%) | 72 | (17.7%) | 113 | (27.9%) | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | |||||||||

| ȃLow risk (0 score) | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.7022 | ||||

| ȃModerate risk (1 score) | 54 | (4.6%) | 21 | (5.6%) | 12 | (3.0%) | 21 | (5.2%) | |

| ȃHigh risk (≥ 2 score) | 1126 | (94.8%) | 353 | (94.1%) | 390 | (95.7%) | 384 | (94.4%) | |

| Insurance provider | |||||||||

| ȃMedicare | 1008 | (84.8%) | 311 | (82.9%) | 359 | (88.1%) | 338 | (83.1%) | 0.631 |

| ȃMedicaid | 19 | (1.6%) | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | ||||

| ȃPrivate insurance | 136 | (11.4%) | 42 | (11.3%) | 41 | (10.1%) | 52 | (12.8%) | |

| ȃSelf-pay | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | |||||

| ȃOther | 18 | (1.5%) | 10 | (2.8%) | < 10 | < 10 | |||

| Elective index admission | 907 | (76.6%) | 322 | (86.3%) | 382 | (93.7%) | 204 | (50.3%) | < 0.001 |

CA, Ablation of atrial fibrillation; LAAO, left atrial appendage occlusion procedure.

No encounters identified.

Table 2.

Comorbidities of the study population identified during index hospitalization from Elixhauser comorbidity Index

| Covariates | Total (n = 1189) | LAAO and CA (n = 375) | LAAO only (n = 407) | CA only (n = 406) | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypertension, uncomplicated | 519 | (43.7%) | 152 | (40.5%) | 211 | (51.9%) | 156 | (38.4%) | 0.0507 |

| Congestive heart failure | 472 | (39.7%) | 149 | (39.7%) | 119 | (29.2%) | 204 | (50.2%) | 0.0025 |

| Hypertension, complicated | 471 | (39.6%) | 160 | (42.7%) | 130 | (32.0%) | 180 | (44.4%) | 0.0863 |

| Valvular disease | 256 | (21.5%) | 80 | (21.3%) | 85 | (20.8%) | 91 | (22.4%) | 0.9384 |

| Renal failure | 249 | (21.0%) | 87 | (23.2%) | 68 | (16.6%) | 95 | (23.4%) | 0.3421 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 241 | (20.2%) | 50 | (13.3%) | 90 | (22.1%) | 101 | (24.9%) | 0.0688 |

| Hypothyroidism | 233 | (19.6%) | 57 | (15.3%) | 85 | (21.0%) | 90 | (22.1%) | 0.3647 |

| Obesity | 209 | (17.6%) | 58 | (15.5%) | 58 | (14.1%) | 94 | (23.1%) | 0.0782 |

| Diabetes, uncomplicated | 180 | (15.1%) | 51 | (13.5%) | 72 | (17.6%) | 57 | (14.1%) | 0.5968 |

| Diabetes, complicated | 171 | (14.3%) | 60 | (15.9%) | 67 | (16.4%) | 44 | (10.8%) | 0.4123 |

| Peripheral vascular disorders | 161 | (13.5%) | 47 | (12.6%) | 60 | (14.6%) | 54 | (13.3%) | 0.8961 |

| Fluid and Electrolyte Disorders | 116 | (9.8%) | 29 | (7.8%) | 15 | (3.6%) | 72 | (17.7%) | 0.0011 |

| Depression | 89 | (7.5%) | 26 | (7.0%) | 32 | (7.8%) | 31 | (7.6%) | 0.9683 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 71 | (6.0%) | 23 | (6.1%) | 11 | (2.7%) | 37 | (9.2%) | 0.0565 |

| Other neurological disorders | 50 | (4.2%) | 11 | (3.0%) | 20 | (4.8%) | 19 | (4.6%) | 0.7248 |

| Coagulopathy | 49 | (4.1%) | 21 | (5.6%) | 19 | (4.7%) | < 10 | 0.2895 | |

| Rheumatoid disease | 45 | (3.8%) | 15 | (3.9%) | 13 | (3.1%) | 17 | (4.3%) | 0.8553 |

| Deficiency anaemia | 38 | (3.2%) | 17 | (4.5%) | < 10 | 17 | (4.2%) | 0.2015 | |

| Liver disease | 30 | (2.5%) | < 10 | 15 | (3.6%) | < 10 | 0.5305 | ||

| Alcohol abuse | 25 | (2.1%) | < 10 | 12 | (2.9%) | < 10 | 0.6813 | ||

| Solid tumour without metastasis | 22 | (1.8%) | < 10 | < 10 | 13 | (3.2%) | 0.248 | ||

| Blood loss anaemia | 16 | (1.3%) | < 10 | 11 | (2.7%) | a | 0.0994 | ||

| Weight loss | 15 | (1.3%) | < 10 | a | 14 | (3.4%) | 0.0145 | ||

| Psychoses | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.9174 | ||||

| Metastatic cancer | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.6937 | ||||

| Lymphoma | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | a | 0.5434 | ||||

| Drug abuse | < 10 | < 10 | a | < 10 | 0.4672 | ||||

| Paralysis | < 10 | a | < 10 | a | 0.6695 | ||||

CA, ablation of atrial fibrillation; LAAO, left atrial appendage occlusion procedure.

No encounters identified.

Among the total study population, Medicare was the primary insurance provider (84.8%), with most of the procedures being performed in large (67.9%), private non-profit (82.3%), and metropolitan teaching (88.8%) hospitals. The characteristics of the hospitals that contributed to the study population have been provided in Supplementary material online, Table S2.

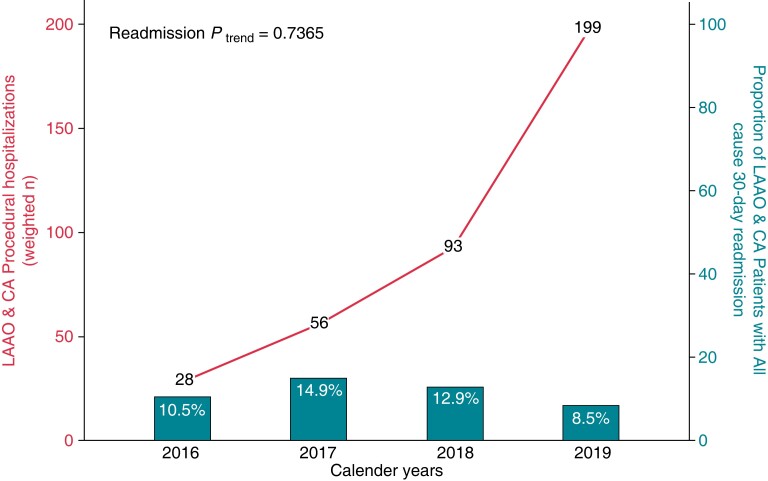

Incidence and readmissions among left atrial appendage occlusion + catheter ablation cohort

During the study period in the USA, we report a steady increase in the number of LAAO and CA simultaneous procedures [28 (2016) vs. 199 (2019)] performed on the same day. However, all-cause 30-day readmission rate remained relatively unchanged [10.5% (2016) vs. 8.5% (2019), Ptrend = 0.737]. Index and readmission hospitalization trends have been presented in Figure 1. Readmission rates among LAAO + CA not significantly different when compared with LAAO-only (10.7% vs. 12.7%, P = 0.629) or CA-only (10.7 vs. 17.5%, P = 0.145).

Figure 1.

Incidence and all-cause 30-day readmission trends among patients undergoing LAAO and CA procedure in the United States. LAAO, Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion device; CA, Percutaneous Atrial Fibrillation Ablation.

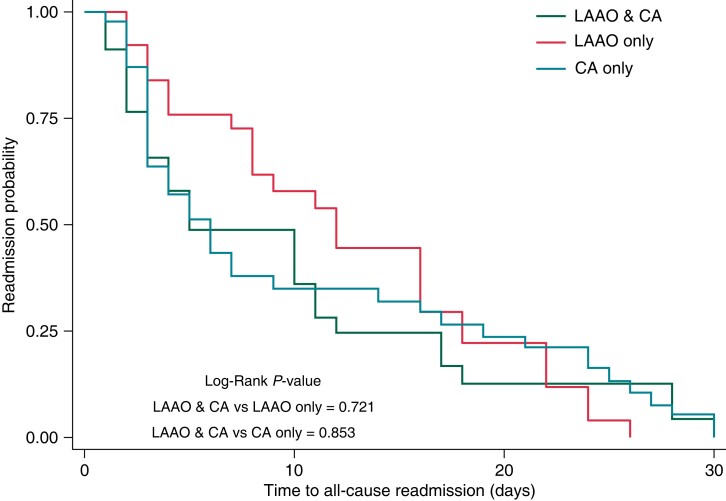

Among LAAO + CA patients readmitted within 30 days, approximately one-fourth were hospitalized primarily for heart failure, followed by paroxysmal AF (7.1%). There was no significant difference in readmission probability and time-to-readmission after index procedural hospitalization among the LAAO + CA group compared to the LAAO-only or CA-only group (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for all-cause 30-day readmission risk stratified by study cohorts.

Major adverse cardiovascular events

MACE during index hospitalization occurred among 82 patients (6.9%), but there was no significant difference in MACE among the LAAO + CA group (8.1%) vs. the LAAO-only (5.3%, P = 0.339) or CA-only group (7.4%, P = 0.983). Pericardial effusion was the most common complication among all three cohorts (5.2 vs. 3.1% vs. 4.7%, P = 0.603), while the incidence of in-hospital mortality was 0.5% and noted only among the LAAO + CA cohort.

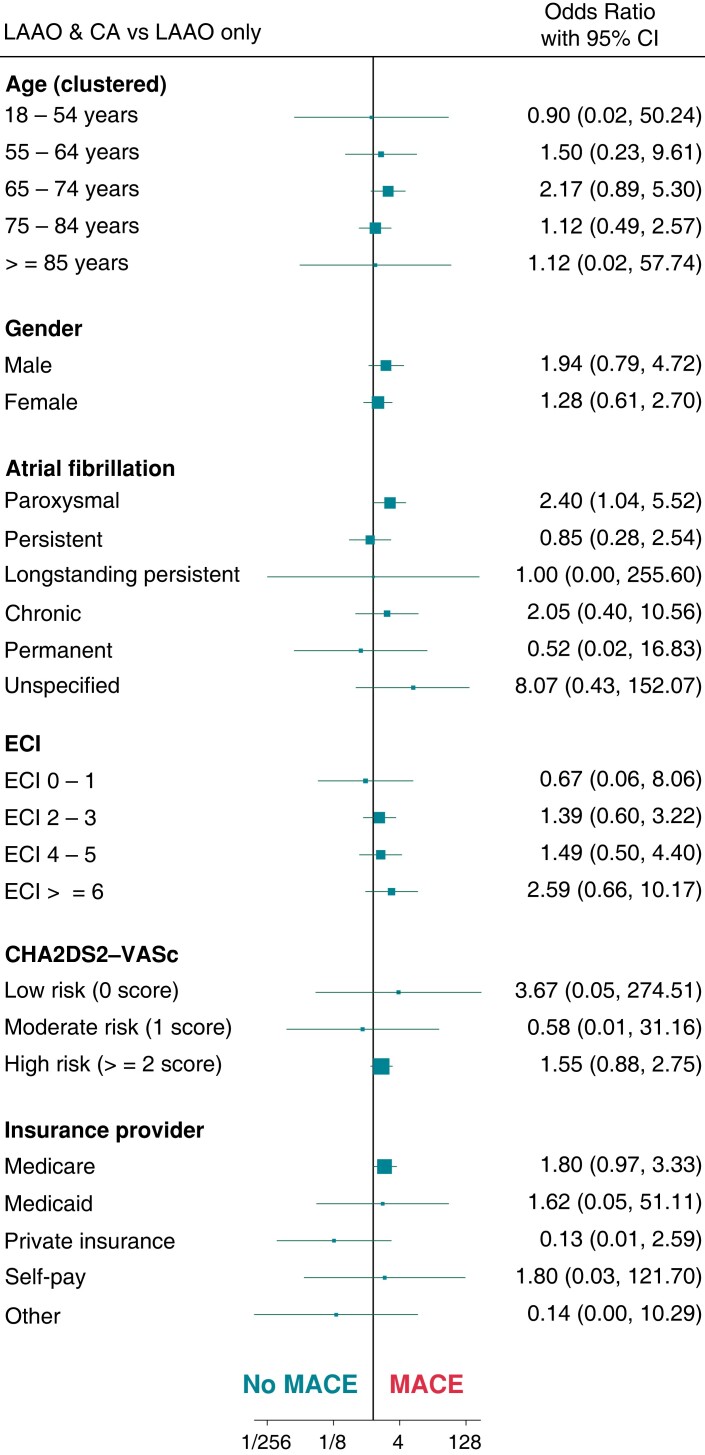

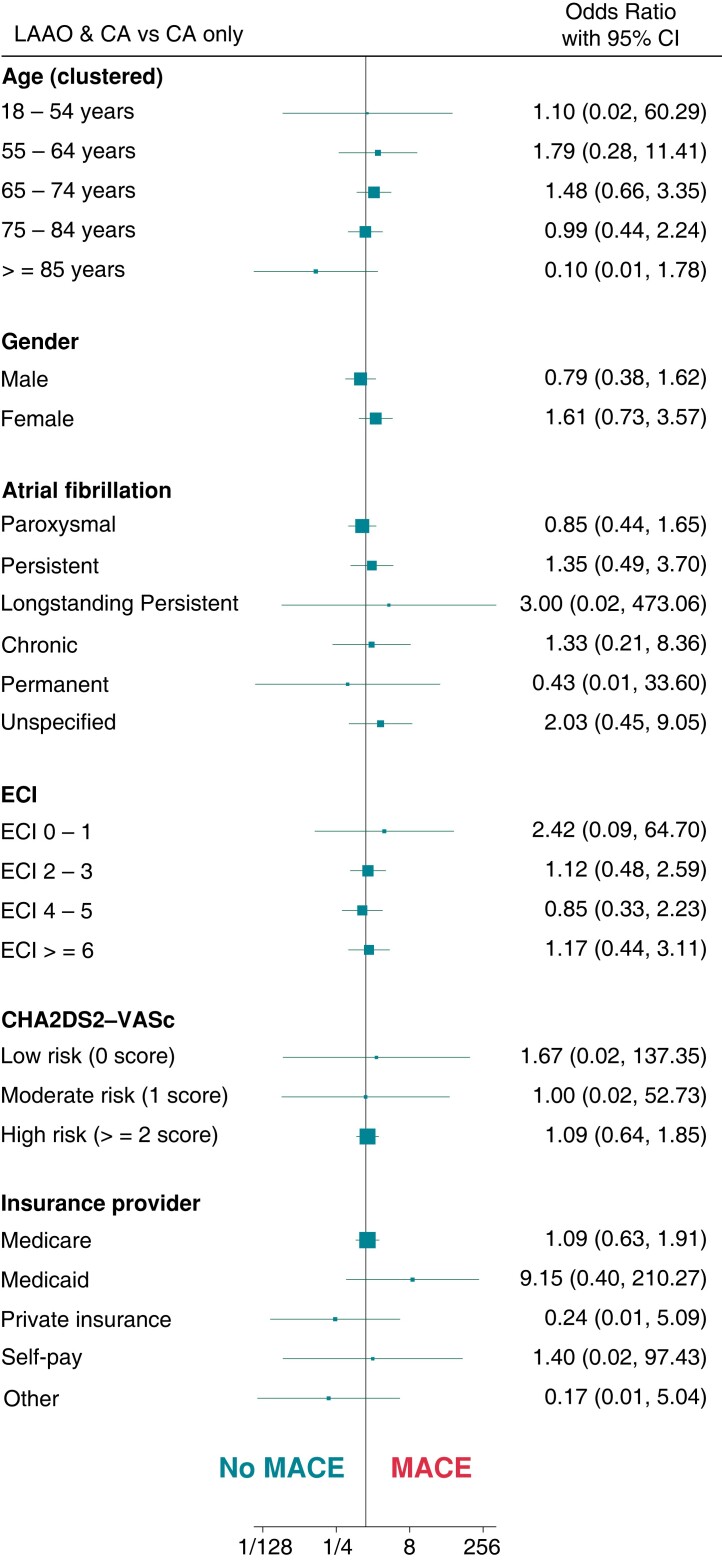

The predictors of MACE by patient demographic among the LAAO + CA cohort in comparison with LAAO-only and CA-only are summarized in Figure 3 and Figure 4, respectively. In comparison to the LAAO-only cohort, the only significant predictor for MACE in the LAAO + CA cohort was paroxysmal AF (OR: 2.4, 95% CI: 1.04–5.52). While, when compared to the CA-only cohort, among patient demographics in the LAAO + CA cohort, there were no significant predictors of MACE.

Figure 3.

Demographic predictors of major adverse cardiovascular events among LAAO + CA and LAAO only cohort. LAAO, Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion device; CA, Percutaneous Atrial Fibrillation Ablation; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; MACE, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events.

Figure 4.

Demographic predictors of Major adverse cardiovascular events among LAAO + CA and CA only cohort. LAAO, Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion device; CA, Percutaneous Atrial Fibrillation Ablation; ECI, Elixhauser Comorbidity Index; MACE, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events.

Patient comorbidities among the LAAO + CA group which significantly predicted MACE in comparison to LAAO-only were hypertension with complications [odds ratio (OR): 5.03, 95% CI: 1.44–17.57], chronic pulmonary disease (OR: 4.83, 95% CI: 1.19 –19.63) and congestive heart failure (OR: 3.13, 95% CI: 1.13–8.71). While in comparison with CA-only, only chronic pulmonary disease (OR: 5.44, 95% CI: 1.34–22.08) significantly predicted MACE (see Supplementary material online, Figures S2 and S3). Hospital characteristics among the LAAO + CA group, which predicted MACE compared with LAAO-only and CA-only, have been summarized in Supplementary material online, Figures S4 and S5.

Secondary outcomes

Among all the patients readmitted within 30-days (n = 163), MACE was noticed in 13.9%, with pericardial effusion being the leading complication (9%). Pericardiocentesis, cardioversion, and in-hospital mortality during readmission were very low (<10). None of the patients experienced a stroke or transient ischaemic attack. Additionally, there was no significant difference in MACE during readmission across the sub-groups (Table 3). After the index procedural hospitalization, the majority of patients were discharged home (87.1%) across the study groups [LAAO + CA (85.8%), LAAO-only (94.8%) and CA-only (80.5%), P = 0.016]. The median length of stay of the total study population during index hospitalization was 1 day, while during readmission, it was 3 days, with minimal variation across the sub-groups (Table 3). The proportion of patients being discharged to the skilled nursing facility was significantly lower in the LAAO-only (2.5%) cohort when compared with LAAO + CA (5.5%) and CA-only (6.1%, P = 0.016).

Table 3.

Outcomes of interest among the study population

| Total | LAAO and CA | LAAO only | CA only | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcome | (n = 1189) | (n = 375) | (n = 407) | (n = 406) | ||||||

| MACE | 82 | (6.9%) | 30 | (8.1%) | 22 | (5.3%) | 30 | (7.4%) | 0.6086 | |

| ȃPericardial effusion | 52 | (4.3%) | 20 | (5.2%) | 13 | (3.1%) | 19 | (4.7%) | 0.6034 | |

| ȃPericardiocentesis | 27 | (2.2%) | 10 | (2.8%) | < 10 | 12 | (2.9%) | 0.5165 | ||

| ȃBlood transfusion | 22 | (1.9%) | 12 | (3.1%) | < 10 | < 10 | 0.4552 | |||

| ȃStroke/TIA/thromboembolism | < 10 | a | < 10 | < 10 | 0.5819 | |||||

| ȃIn-hospital mortality | < 10 | < 10 | a | a | 0.5114 | |||||

| 30-day readmissions | 163 | (13.7%) | 40 | (10.7%) | 52 | (12.7%) | 71 | (17.5%) | 0.2341 | |

| Secondary outcome | ||||||||||

| Index hospitalization | ||||||||||

| ȃLength of stay (median, IQR; days) | 1 | (1–4) | 1 | (1–4) | 1 | (1–2) | 3 | (2–7) | 0.001 | |

| ȃDisposition | ||||||||||

| ȃȃHome or self-care | 1035 | (87.1%) | 322 | (85.8%) | 386 | (94.8%) | 327 | (80.5%) | 0.016 | |

| ȃȃHome with home care | 96 | (8.1%) | 31 | (8.2%) | 11 | (2.6%) | 55 | (13.4%) | ||

| ȃȃSkilled nursing facility | 56 | (4.7%) | 20 | (5.5%) | 10 | (2.5%) | 25 | (6.1%) | ||

| Readmission hospitalization | (n = 163) | (n = 40) | (n = 52) | (n = 71) | ||||||

| ȃMACE | 23 | (13.9%) | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.811 | ||||

| ȃȃPericardial effusion | 15 | (9.0%) | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.9493 | ||||

| ȃȃPericardiocentesis | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | 0.7027 | |||||

| ȃȃBlood transfusion | < 10 | < 10 | < 10 | a | 0.1033 | |||||

| ȃȃStroke/TIA | a | a | a | a | ||||||

| ȃȃIn-hospital mortality | < 10 | < 10 | a | < 10 | 0.4054 | |||||

| ȃCardioversion | < 10 | < 10 | a | < 10 | 0.5617 | |||||

| ȃLength of stay (median, IQR; days) | 3 | (2–7) | 2 | (2–9) | 3 | (2–8) | 3 | (2–6) | 0.766 | |

| ȃHospitalization cost (median, IQR; $ per 10 000) | 38.9 | (21–91) | 32.5 | (14–116) | 40.9 | (14–112) | 40.0 | (22–112) | 0.432 | |

CA, ablation of atrial fibrillation; LAAO, left atrial appendage occlusion procedure; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

No encounters identified.

Primary diagnosis during readmission hospitalization in the matched cohort

Among the LAAO-only cohort, the most frequent primary reason for readmission was heart failure (31.5%), followed by paroxysmal AF (20.1%). While, among the matched CA-only cohorts, the most frequent primary reason for readmission was paroxysmal AF (17.7%), followed by an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (10.9%). Supplementary material online, Table S3 summarizes the most frequent primary diagnosis during readmission.

Sensitivity analysis

The majority of the LAAO and CA procedures were performed on the same day (91%, n = 375), while 3.9% (n = 16) had LAAO implanted before CA, and 5.3% (n = 22) had LAAO performed after CA Supplementary material online, Figure S6. There was no significant difference in MACE during index hospitalization among patients undergoing LAAO + CA procedure on the same day (8%) when compared with those undergoing LAAO before CA (20%) or undergoing LAAO after CA (21%, P = 0.3). This could result from an imbalance in the patient population undergoing the combined procedure on the same day vs. on different days. None of the patients developed major bleeding during index hospitalization among those undergoing LAAO before CA, while patients undergoing LAAO + CA procedure had significantly lower major bleeding (3.1%) compared with those undergoing LAAO after CA (15%, P = 0.03). There was no significant difference in the incidence of pericardial effusion or pericardiocentesis irrespective of LAAO + CA timing.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis from the most extensive available nationwide readmission database of the US patient population, we analyzed 375 patients undergoing concomitant LAAO and percutaneous AF ablation on the same day between 2016 and 2019, with 8.1% of patients experiencing MACE during index hospitalization and approximately 11% patients were readmitted within 30-days. Compared to propensity score-matched patients undergoing either LAAO-only or CA-only, LAAO + CA patients did not significantly differ in MACE during index or readmission hospitalization and had similar readmission rates.

Our data suggest that in the USA, combined LAAO + CA procedures, while still low, are being performed successfully and increased over 7-fold during the 4-year study period. The idea of comparing the combined procedure with a propensity score match patients undergoing either of the procedures alone was to assess complication rates while controlling for confounding bias. In comparison to a 5-year pooled meta-analysis of PREVAIL and PROTECT-AF, our study noticed the same major bleeding rates (3.1%), while none of the patients experienced stroke/transient ischaemic attack (1.7% in the pooled meta-analysis).12 All-cause in-hospital mortality rate combining index and readmission hospitalization in our study was lower (1.6%) than reported in PROTECT-AF (12.3%) or PREVAIL (2.6%).7,8 Additionally, comparing outcomes from the ablation patients in the CABANA trial to those randomized to drug therapy, we noticed a lower death (6.1 vs. 1.5%) and similar serious bleeding rates (3.2 vs. 3.1%) during index hospitalization.16

Interestingly, patients in the LAAO + CA cohort had a trend towards a lower AF-related readmission rate compared with the matched CA-only patients (7.1 vs. 25.7%, P = 0.356), although not statistically significant. This can be attributed to additional electrical isolation of the LAA (inclusion criteria consisted of LAA percutaneous ablation), which among a small group of patients (n = 20) has been demonstrated to be more effective in maintaining sinus rhythm at the end of 1-year compared with CA alone.17 Also, there were no strokes or transient ischaemic attacks during the index hospitalization among the LAAO + CA group. However, < 1% of patients in the matched LAAO-only or CA-only cohort were reported to have a stroke or transient ischaemic attack during the index hospitalization. During readmission, no patient experienced a stroke or TIA across the groups.

Compared with antiarrhythmic medications, CA is superior in maintaining sinus rhythm and reducing the burden of AF. However, the impact of merely attaining sinus rhythm or reducing AF burden on stroke reduction is an area of ongoing research. In a large registry-based study, the LAA was demonstrated to be the focus for AF recurrence in approximately 27% of CA patients (approximately 9% having LAA as the only foci of AF).9 The large multicentre randomized control trial (aMAZE trial) demonstrated a lower trend (non-significant) towards recurrence of atrial arrhythmias among early persistent AF patients undergoing percutaneous LAA ligation with the LARIAT system in addition to pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) when compared with those undergoing PVI alone.18 Additionally, as demonstrated in the LAAOS III randomized control trial, surgical isolation of the LAA during cardiac surgery (leading to both electrical and thromboembolic isolation) is associated with a significant reduction in ischaemic stroke or noncerebral systemic embolism.19 Therefore, supplementing CA with electro-embolic isolation of the LAA can provide an additive benefit in managing AF.

Henceforth, as demonstrated in our study, compared with propensity score-matched patients undergoing either LAAO-only or CA-only, combining LAAO + CA is safe (no significant difference in MACE during index or readmission hospitalization) and is associated with a trend toward lower all-cause 30-day readmission rates and shorter length of index and readmission hospitalization. We also demonstrated a lower recurrence of AF-associated rehospitalization among the LAAO + CA cohort. However, choosing the right patient for the combined procedure remains unsettled. The ongoing clinical trial, Comparison of Anticoagulation With Left Atrial Appendage Closure After AF Ablation [OPTION trial (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03795298)], may provide further direction. Until then, clinical decision-making should consider the patient's CHA2DS2-VASc score, bleeding risk, duration of AF and the size of the left atrium.13

Limitations

This study is limited by the retrospective and administrative nature of the NDR database, which also precluded us from assessing clinical, pre and postprocedural transesophageal echocardiogram findings (peri-device leak), type of CA procedure (radiofrequency or cryoballoon), size of the LAAO device, antiarrhythmic medications and anticoagulation of the study population. In this study, we focused on identifying patients undergoing simultaneous LAAO + CA procedures on the same day. However, there could have been LAAO + CA procedures performed on the same patient during different hospitalization; comparing outcomes among such patients with those undergoing the combined procedure on the same day could be explored in future studies. NRD captures information about the procedure performed in an in-patient setting only, lacking data about outpatient or same-day procedures. Although propensity score match was performed in our study, there might have been selection bias due to imbalance based on the unmatched covariates such as comorbidities, social demographics and medication non-compliance. There could have been some inconsistencies in the diagnosis codes; however, the procedure codes are expected to be more accurate as they tend to drive billing towards a higher DRG which influences hospital reimbursement. Utilizing ICD-10 codes and the HCUP database has been studied extensively in the literature with minimal variation in comparison to real-world data.20

Conclusion

In the USA, combined LAAO and CA procedures are being performed safely. The use of this combined procedure has increased at a rate of approximately 63% annually (from 28 procedures). Compared to the matched LAAO-only or CA-only cohorts, there was no significant difference in MACEs and all-cause 30-day readmission rates. Among LAAO + CA cohorts, the most frequent cause for readmission was heart failure vs. AF among the matched LAAO-only or CA-only cohorts.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Deepak Kumar Pasupula, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, MercyOne North Iowa Medical Center, 1000 4th St SW, Mason City, IA 50401, USA.

Sudeep K Siddappa Malleshappa, Division of Haematology-Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, UMass Chan-Baystate, 759 Chestnut St, Springfield, MA 01199, USA.

Muhammad B Munir, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of California Davis, 4150 V Street, Suite 3100, Sacramento, CA 95817, USA.

Anusha Ganapati Bhat, Department of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Maryland, 620 W Lexington St, Baltimore, MD 21201, USA.

Antony Anandaraj, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, MercyOne North Iowa Medical Center, 1000 4th St SW, Mason City, IA 50401, USA.

Avaneesh Jakkoju, Division of Cardiology, Cardiovascular Institute of South, 441 Heymann Blvd, Lafayette, LA 70503, USA.

Michael Spooner, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, MercyOne North Iowa Medical Center, 1000 4th St SW, Mason City, IA 50401, USA.

Ketan Koranne, Division of Cardiovascular Disease, Department of Internal Medicine, MercyOne North Iowa Medical Center, 1000 4th St SW, Mason City, IA 50401, USA.

Jonathan C Hsu, Division of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of California San Diego, 9500 Gilman Dr. La Jolla, CA 92093, USA.

Brian Olshansky, Department of Cardiology, University of Iowa, 200 Hawkins Dr, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA.

A John Camm, Division of Cardiology, St George's University of London, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, UK.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Europace online.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

NRD is open access, publicly available database that is limited to only those who have completed data usage agreement training. Therefore, we are unable to share the study data.

References

- 1. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist Cet al. 2020 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European association for cardio-thoracic surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European society of cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the European heart rhythm association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2021;42:373–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC Jret al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:e1–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jons C, Hansen PS, Johannessen A, Hindricks G, Raatikainen P, Kongstad Oet al. The medical ANtiarrhythmic treatment or radiofrequency ablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (MANTRA-PAF) trial: clinical rationale, study design, and implementation. Europace 2009;11:917–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morillo CA, Verma A, Connolly SJ, Kuck KH, Nair GM, Champagne Jet al. Radiofrequency ablation vs antiarrhythmic drugs as first-line treatment of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (RAAFT-2): a randomized trial. JAMA 2014;311:692–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Munir MB, Khan MZ, Darden D, Pasupula DK, Balla S, Han FTet al. Contemporary procedural trends of watchman percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion in the United States. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021;32:83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pasupula DK, Munir MB, Bhat AG, Siddappa Malleshappa SK, Meera SJ, Spooner Met al. Outcomes and predictors of readmission after implantation of a percutaneous left atrial appendage occlusion device in the United States: a propensity score-matched analysis from the national readmission database. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2021;32:2961–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reddy VY, Sievert H, Halperin J, Doshi SK, Buchbinder M, Neuzil Pet al. Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure vs warfarin for atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:1988–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Holmes DR Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, Whisenant B, Sievert H, Doshi SKet al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the watchman left atrial appendage closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy: the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;64:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Biase L, Burkhardt JD, Mohanty P, Sanchez J, Mohanty S, Horton Ret al. Left atrial appendage: an underrecognized trigger site of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2010;122:109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lakkireddy D, Sridhar Mahankali A, Kanmanthareddy A, Lee R, Badhwar N, Bartus Ket al. Left atrial appendage ligation and ablation for persistent atrial fibrillation: the LAALA-AF registry. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2015;1:153–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holmes DR Jr, Doshi SK, Kar S, Price MJ, Sanchez JM, Sievert Het al. Left atrial appendage closure as an alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a patient-level meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2614–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S, Gibson DN, Price MJ, Huber Ket al. 5-Year Outcomes after left atrial appendage closure: from the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:2964–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. He B, Jiang LS, Hao ZY, Wang H, Miao YT. Combination of ablation and left atrial appendage closure as “one-stop” procedure in the treatment of atrial fibrillation: current status and future perspective. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2021;44:1259–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Phillips KP, Pokushalov E, Romanov A, Artemenko S, Folkeringa RJ, Szili-Torok Tet al. Combining watchman left atrial appendage closure and catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: multicentre registry results of feasibility and safety during implant and 30 days follow-up. Europace 2018;20:949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Data Use Agreement https://wwwhcup-usahrqgov/DUA/dua_508/DUA508versionjsp#data Accessed on 1 January 2022.

- 16. Packer DL, Mark DB, Robb RA, Monahan KH, Bahnson TD, Poole JEet al. Effect of catheter ablation vs antiarrhythmic drug therapy on mortality, stroke, bleeding, and cardiac arrest among patients with atrial fibrillation: the CABANA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:1261–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Panikker S, Jarman JW, Virmani R, Kutys R, Haldar S, Lim Eet al. Left atrial appendage electrical isolation and concomitant device occlusion to treat persistent atrial fibrillation: a first-in-human safety, feasibility, and efficacy study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Outcomes of Adjunctive Left Atrial Appendage Ligation Utilizing the LARIAT Compared to Pulmonary Vein Antral Isolation Alone—aMAZE. https://wwwaccorg/latest-in-cardiology/clinical-trials/2021/11/12/00/14/amaze14 November 2021.

- 19. Whitlock RP, Belley-Cote EP, Paparella D, Healey JS, Brady K, Sharma Met al. Left atrial appendage occlusion during cardiac surgery to prevent stroke. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2081–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lorence DP, Ibrahim IA. Benchmarking variation in coding accuracy across the United States. J Health Care Finance 2003;29:29–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

NRD is open access, publicly available database that is limited to only those who have completed data usage agreement training. Therefore, we are unable to share the study data.