Background:

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) rarely involves delayed giant coronary aneurysms, multiple readmissions or occurrence after COVID-19 vaccination.

Methods:

We describe a child with all 3 of these unusual features. We discuss his clinical presentation, medical management, review of the current literature and CDC guidance recommendations regarding further vaccinations.

Results:

A 5-year-old boy had onset of MIS-C symptoms 55 days after COVID-19 illness and 15 days after receiving his first BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination. He was admitted 3 times for MIS-C, and twice after his steroid dose was tapered. On his initial admission, he was given intravenous immunoglobulin and steroids. During his second admission, new, moderate coronary dilation was noted, and he was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and steroids. At his last admission, worsening coronary dilation was noted, and he was treated with infliximab and steroids. During follow-up, he had improvement in his coronary artery dilatation. However, his inflammatory markers increased after steroid wean, and his steroid taper was further extended, after which time his inflammatory markers improved. This is the only such reported case of a patient who was admitted 3 times for MIS-C complications after COVID-19 vaccination.

Conclusion:

MIS-C rarely involves delayed giant coronary aneurysms, multiple readmissions, or occurrence after COVID-19 vaccination. Whether our patient’s COVID-19 vaccine 6 weeks after COVID-19 illness contributed to his MIS-C is unknown. After consultation with the CDC-funded Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment Project, the patient’s care team decided against further COVID-19 vaccination until at least 3 months post normalization of inflammatory markers.

Keywords: COVID-19, multisystem inflammatory syndrome, children, vaccination, coronary aneurysm

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) typically presents 2–6 weeks after severe acute respiratory distress syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection.1,2 Cardiac manifestations are common during the acute MIS-C episode, but delayed giant coronary aneurysms and readmissions are rare.3–6 MIS-C with onset after COVID-19 vaccination has been described, with most cases having had evidence of prior SARS-CoV-2 infection.7–12

We report the case of a 5-year-old boy with onset of MIS-C symptoms 55 days after acute COVID-19 illness and 15 days after receiving the first dose of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine) who had recrudescence of MIS-C requiring multiple readmissions associated with significant coronary artery dilation.

CASE

A previously healthy 5-year-old male was hospitalized with fever up to 102 °F for 4 days (day 0 = first day of fever), sore throat, myalgias, abdominal pain, conjunctival injection and rash 55 days after onset of a mild COVID-19 illness that did not require hospitalization and 15 days after receiving the first dose of BNT162b2 (Table 1; Fig. 1). The workup was notable for elevated inflammatory markers [white blood cell (WBC) count 15.55 103/µL (reference: 4.3–12.4), C-reactive protein (CRP) 19.3 mg/dL (reference: <1)], mildly elevated cardiac biomarkers including brain natriuretic peptide [103.7 pg/mL (reference: <100.0)] and troponin-I [0.036 ng/mL [reference: <0.03]) with evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antinucleocapsid antibody (Tables 1 and 2). Although he had features suggestive of incomplete Kawasaki disease (KD), given a positive COVID-19 test on both PCR and antinucleocapsid antibody the child met CDC case definition for MIS-C and was diagnosed as such (Fig. 1).14,15 Per hospital protocol for management of MIS-C with KD features, he was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 2 g/kg, steroids (methylprednisolone 1mg/kg intravenously twice daily for one day followed by prednisone 1 mg/kg orally twice daily for four days) and daily aspirin 81 mg (Table 1). Echocardiography during the initial hospitalization was reassuring with normal cardiac function and no coronary artery dilation. The patient demonstrated clinical improvement with resolution of symptoms, and on day 6 of MIS-C illness, he was discharged home with low-dose aspirin for 6 weeks and 1 day of prednisone.

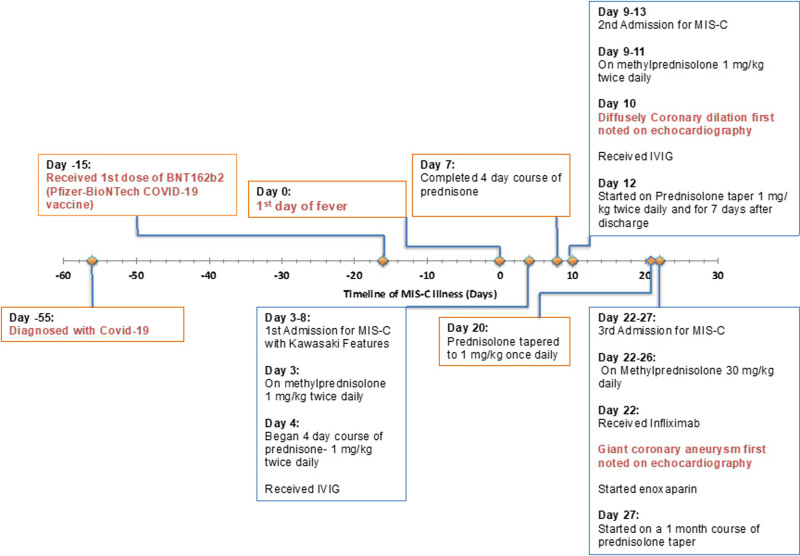

FIGURE 1.

Course of illness in a 5-year-old boy with MIS-C 55 days after COVID-19 diagnosis and 15 days after COVID-19 vaccination. His course was complicated by severe coronary dilation and recrudescence of MIS-C symptoms requiring 2 additional readmissions. Day 0 indicates day patient was initially symptomatic for MIS-C.

TABLE 1.

Patient Demographics, Clinical Features, and Management of a Child with MIS-C and Severe Coronary Artery Dilatio

| Category | Patient |

|---|---|

| Age | 5 y |

| Sex | Male |

| Race | White, non-Hispanic |

| Comorbidities | None |

| Met CDC definition of MIS-C | Yes |

| Age <21 y | Yes |

| Fever | Yes |

| Inflammatory laboratories | Yes |

| Severe illness; hospitalized | Yes |

| Multiorgan involvement | Dermatologic, gastrointestinal, respiratory, cardiac, hematologic |

| Positive SARS-Cov2 test | PCR and antinucleocapsid serology |

| Met criteria for KD | No, but had features consistent with incomplete Kawasaki disease13 |

| Fever × 5 d or until IVIG | Yes |

| Conjunctivitis | Yes |

| Extremity changes | No |

| Rash | Yes |

| Oral mucosal changes | Yes |

| Cervical lymphadenopathy | No |

| Laboratory criteria | 3/6 (White blood cell count 15.55 [103/µL], hemoglobin 10.6 [g/dL], albumin 3.1 [g/dL]) |

| CRP > 3 mg/dL | Yes |

| ESR > 40 mm/h | Yes |

| Giant CAA diagnosis | Day 22 of MIS-C illness |

| Maximum z-score | 15.59 (LAD), 6.75 (RCA), 4.41 (LMCA) |

| MIS-C treatment pre-giant CAA diagnosis | IVIG, methylprednisolone, prednisone, aspirin |

| MIS-C treatment post-giant CAA diagnosis | Infliximab, methylprednisolone, prednisone, enoxaparin, aspirin |

| Coronary artery thrombosis diagnosis | No |

| Coronary aneurysm size | 3.10 mm (LAD), 5.80 (RCA), 3.0 mm (LMCA) |

| Ongoing therapy | Famotidine, Aspirin |

CAA indicates coronary artery aneurysms; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

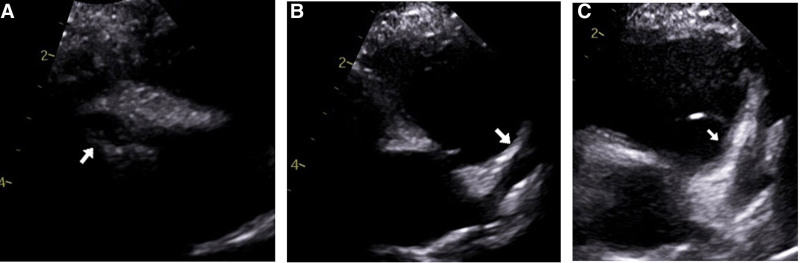

A day after completing the prescribed 5-day course of steroids, the patient was readmitted on day 9 with slightly elevated temperature (100 °F), fatigue, cough, faint blanching macular rash on the chest and abdomen, conjunctivitis and dry, cracked lips. Laboratory studies were notable for elevations in WBC count (25.6 103/µL), CRP (4.4 mg/dL), and D-dimer [405 ng/mL (reference: 0–220)] (Table 2). His troponin and brain natriuretic peptide were within normal limits. He was diagnosed with recrudescence of MIS-C with KD features and started on methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg IV q12h and low-dose aspirin with resolution of symptoms. Echocardiography on day 10 was significant for new, moderately dilated coronary arteries with no obvious aneurysms, and the patient was promptly given a second dose of IVIG 2g/kg, following which he remained afebrile (Figs. 1–3). On day 13, he was discharged with a 2-week taper of prednisolone and low-dose aspirin. Until day 19 of illness, he took 1 mg/kg of prednisolone twice daily.

TABLE 2.

Most Representative Laboratory Values Reflective of Inflammation and Cardiac Injury Throughout the MIS-C Disease Course

| Labs | Day 3 | Day 4 | Day 5 | Day 9 | Day 11 | Day 13 | Day 22 | Day23 | Day 27 | Day 55 | Day 60 | Day 85 | Day 117 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood count (103/µL) (ref: 4.3–12.4) |

15.55 | 15.21 | — | 25.60 | 23.69 | 25.83 | 30.82 | 27.38 | 20.66 | 12.3 | 16.95 | 6.3 | — |

| CRP (mg/dL) (ref: <1) |

19.3 | 21.0 | 8.7 | 4.4 | 16.3 | 2.9 | 6.1 | 17.5 | 0.2 | 11.1 | — | 0.2 | <1 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) (ref: 13.7–78.8) |

— | 96.97 | — | 39.77 | — | 65.28 | 107.29 | 52.75 | 106 | — | 23 | — | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (ref: 10.9–14.8) |

10.6 | 10.5 | 11.3 | 10.3 | 10.8 | 10.3 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 9.3 | 9.9 | 10.9 | — | |

| D-dimer (ng/mL) (ref: 0–220) |

412 | — | — | 405 | — | — | 268 | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Platelets (103/µL) (ref: 150–450) |

478 | 450 | — | 644 | 551 | — | 612 | 532 | 611 | 899 | — | 739 | — |

| Albumin (g/dL) (ref: 3.5–4.5) |

3.1 | 3.0 | — | 3.0 | — | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 4.2 | — | — | — | |

| B-natriuretic peptide (pg/mL) (ref: <100.0) |

103.7 | 177.8 | — | 30.3 | — | 62.4 | — | — | — | — | — | ||

| Troponin-I (ng/mL) (ref: <0.03) |

0.036 | — | — | <0.010 | — | <0.010 | — | — | — | — | — |

Only selected days of laboratory measurements are shown.

FIGURE 3.

Two-dimensional echocardiograms demonstrating dilated coronary arteries. A: Mild dilation of right coronary artery (3.4 mm, z-score: +4.02) on day 10 of MIS-C illness. B: Mild dilation of the left main coronary artery (3.1 mm, z-score: +3.87) on day 10 of MIS-C illness. C: Severe dilation of left main coronary artery (6.7 mm, z-score: +15.59) on day 22 of MIS-C illness.

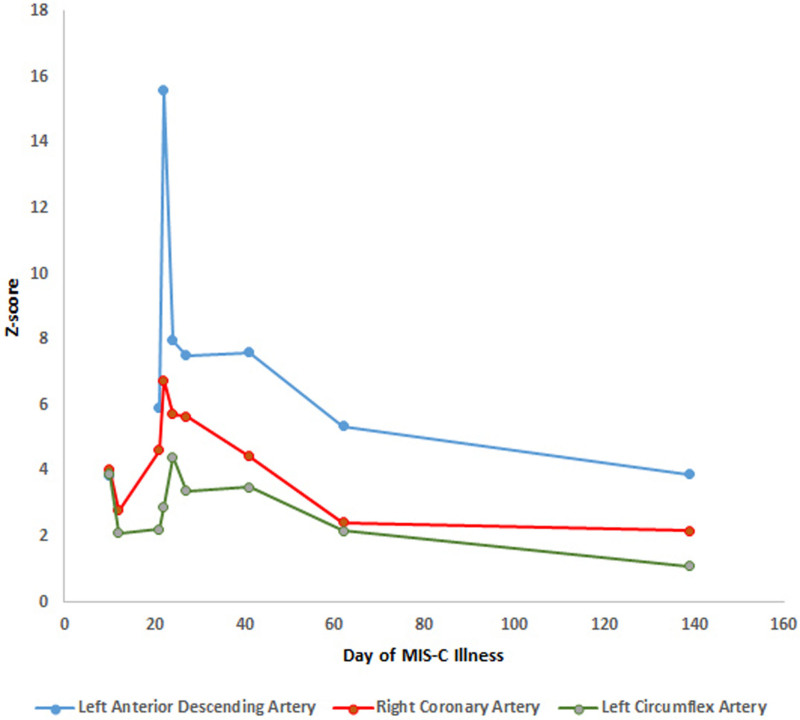

On day 20, the patient started his planned prednisolone taper of 1 mg/kg daily. He then presented with tactile fever, dry cracked lips, conjunctivitis, and abdominal pain on day 22. Inflammatory markers had increased since previous discharge (WBC 30.82 103/µL), CRP 6.1 mg/dL) (Table 2). Echocardiography was significant for severe dilation to his coronary arteries: right coronary artery (RCA) (4.5 mm, z-score 6.5) and left anterior descending artery (LAD) (6.7 mm, z-score 15.59) (Fig. 3C). He was admitted for the third time and began treatment for refractory MIS-C with infliximab 10 mg/kg IV and methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg IV for 5 days. As the LAD dimensions met criteria for a giant coronary aneurysm, he was also given enoxaparin for his coronary artery dilation per the American Heart Association Kawasaki guidelines.13 On day 24, echocardiography continued to show severe coronary artery dilation, most significant for the LAD (4.4 mm, z-score 7.98) (Fig. 2). His inflammatory markers and clinical course improved, and he was discharged on day 27 on enoxaparin, daily aspirin and a 30-day steroid taper.

FIGURE 2.

Evolution of echocardiographic Z-score vs. time (day of MIS-C illness). Patient was noted to have giant coronary aneurysms 22 days after he was initially symptomatic for MIS-C.

Nearly a month after discharge, on day 55, the patient remained asymptomatic, but his inflammatory markers began increasing (CRP 11.1 mg/dL), and his steroid taper was further extended (Table 2). On day 64, a repeat echocardiogram showed improvement in the diffuse coronary artery dilation to the mildly dilated range except for the LAD artery at the takeoff of the first diagonal branch in the moderate range. A cardiac computed tomography study on day 94 showed mild RCA dilation with 3 small- to medium-sized right coronary aneurysms in the mid and distal segments, not visible on echocardiogram. The left main coronary artery and left anterior descending coronary artery were improved to normal, except for aneurysmal dilation at the left anterior descending at the level of the first diagonal branch takeoff, which was like what was seen by echocardiogram. On day 112, his prednisolone was discontinued and on day 117 his inflammatory markers were notably improved with a CRP < 1 mg/dl. His last echocardiogram (day 139) before the article submission showed slight improvement (Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

We report a case of MIS-C with three unusual features: development of a delayed giant coronary aneurysm, multiple recrudescent episodes resulting in hospital readmissions and occurrence after COVID-19 vaccination with a recent history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

MIS-C has been associated with cardiac manifestations in >80% of cases, but reports of giant coronary aneurysms (z-score ≥ 10 or diameter ≥ 8 mm) and delayed coronary dilation in MIS-C are scarce.3–5 In our patient, coronary aneurysms developed after the administration of IVIG, and much later in his disease course—nearly 3 weeks after he was initially symptomatic. Infliximab has been shown to improve coronary aneurysms in refractory MIS-C and in other types of vasculitis including KD and Behçet Disease.16,17

Our patient was admitted 3 times for MIS-C refractory to initial treatment with IVIG, corticosteroids and anti-inflammatory agents, most likely due to rebound inflammation. Readmission for the same episode of MIS-C is rare.6 Among the 456 cases of MIS-C at the child’s institution, he is the only patient to date to require two readmissions for MIS-C. Notably, his MIS-C symptoms first resurfaced a day after he completed his course of prednisone and then again a day after his prednisone taper was decreased to 1 mg/kg daily. It appears this patient needed a longer course with higher dosing to achieve suppression of his inflammation. Glucocorticoids have been shown to reduce the need for adjuvant therapy, decrease the duration of fevers and reduce the need for hemodynamic support.18 A month after, he was discharged from the hospital, his inflammatory markers were rising and his steroid taper was adjusted accordingly.

Given the timing of our patient’s MIS-C onset relative to his first dose of COVID-19 vaccination and the severity of his MIS-C illness, questions regarding further COVID-19 vaccination were raised. First, the care team had concerns regarding the potential contribution of COVID-19 vaccine to the occurrence of MIS-C. Published literature and CDC MIS-C surveillance activities suggest that (1) COVID-19 vaccine is highly effective in preventing MIS-C; (2) MIS-C after COVID-19 vaccination is rare, with most cases having evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection; and (3) the contribution of vaccination to these cases, if any, is unknown.7–12,19 The CDC Interim Clinical Considerations advise patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection to wait until after they have recovered from acute COVID-19 illness and have met criteria to discontinue isolation before obtaining COVID-19 vaccination.20 CDC guidance further advises, however, that individuals may consider delaying vaccination by 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms (or positive test if no symptoms) given possibility of improved immune response and observed low risk of reinfection in the weeks to months after SARS-CoV-2 infection.20 Whether our patient’s COVID-19 vaccine 6 weeks after COVID-19 illness contributed to his MIS-C is unknown. Pediatricians should be aware that the option for an extended interval between SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination exists.

The second question regarding vaccination was whether our patient should receive a second dose of vaccine to complete his primary series of COVID-19 vaccination. Current CDC guidance recommends that further COVID-19 vaccine doses in children with MIS-C within 90 days after vaccination should be deferred until more safety data are available, unless there is strong evidence that the episode of MIS-C was a complication of a recent SARS-CoV-2 infection.20 Given the complexities of this case, consultation was requested from the CDC-funded Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project regarding future vaccinations.21,22 CISA is a collaboration between CDC and 7 medical research centers with expertise in vaccine safety and multiple medical specialties that provides consultation to US healthcare providers with complex patient vaccine safety questions. Advice from CISA is meant to assist in decision-making, rather than provide direct patient management. CISA experts advised deferring COVID-19 vaccine at the current time and suggested review of the risks and benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine and available vaccine formulations in the CDC Interim Clinical Considerations when the child is fully recovered. The child’s care team agreed, opting to recommend that the family not seek further doses of COVID-19 vaccine at this time. However, the care team committed to reconsidering administration of COVID-19 vaccine at least three months after his inflammatory markers normalized, considering such factors at that time as community prevalence of SARS-CoV-2, latest data on benefit and safety of further doses of vaccines (particularly in those with prior history of COVID-19), and effectiveness of available vaccines against prevailing strains of SARS-CoV-2.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the contributions of the CISA Project, a consultation service supported by CDC through contracts to CISA Project sites. Authors received salary support from their institutions. Cases accepted for CISA consultation are reviewed free of charge to the healthcare providers. In addition, we acknowledge the following individual contributors to this CISA consultation.

CDC: Karen R. Broder, MD; Tom Shimabukuro, MPH, MBA, MD; Michael McNeil, MD, MPH; Allison Lale, MD, MPH; Andrea Thames-Allen, MD, MPH; Angela Campbell, MD, MPH; Anna Yousaf, MD; Jennifer Wiltz, MD, MPH; Christine Robin Curtis, MD MPH; Oidda Museru, MSN, MPH; and Shashi Sharma, PhD, RN

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center: Mary Staat, MD, MPH; Sean Lang, MD; Chitravati Choony, BS

Vanderbilt University: Kathryn Edwards, MD; C. Buddy Creech, MD, MPH; Donna Hummell, MD; Allison Norton MD; Paula Campbell, MS MPH; Braxton Hern, BS

Johns Hopkins University: Neal Halsey, MD; Kawsar Talaat, MD

Duke University: Emmanuel Walter, MD, MPH; Michael Smith MD, MS

We also acknowledge colleagues from the Georgia Department of Public Health: Sheila Lovett, Immunization Program Director; Walaa Elbedewy, MBBCh, MPH, MPA, MIS-C Epidemiologist; Melissa Tobin-D’Angelo, MD, MPH.

Finally, we acknowledge all clinicians providing care for this child, including his pediatrician, John “Wes” Johnson, MD.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

M.E.O. serves as site principal investigator for an NIH study funded by Pfizer-BioNTech on myocarditis and pericarditis associated with COMIRNATY. S.K.’s institution has received funding from NIH to conduct clinical trials of Moderna and Janssen COVID-19 vaccines, and funding from Pfizer to conduct clinical trials of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines. E.P.S. receives research funding from Pfizer, Inc., to investigate a maternal respiratory syncytial virus vaccine and serves as a consultant for Sanofi Pasteur. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Khadija Haq, Email: khaq@msm.edu.

E. Gloria Anyalechi, Email: iyo8@cdc.gov.

Elizabeth P. Schlaudecker, Email: elizabeth.schlaudecker@cchmc.org.

Rachel McKay, Email: mckayr@kidsheart.com.

Satoshi Kamidani, Email: satoshi.kamidani@emory.edu.

Cynthia K. Manos, Email: cynthia.k.manos@emory.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, et al. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1607–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belay ED, Abrams J, Oster ME, et al. Trends in geographic and temporal distribution of US children with multisystem inflammatory syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:837–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu EY, Campbell MJ. Cardiac manifestations of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) following COVID-19. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2021;23:168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villacis-Nunez DS, Hashemi S, Nelson MC, et al. Giant coronary aneurysms in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3:1499–1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson MC, Mrosak J, Hashemi S, et al. Delayed coronary dilation with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. CASE (Phila). 2022;61:31–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villacis-Nunez DS, Jones K, Jabbar A, et al. Short-term outcomes of corticosteroid monotherapy in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:576–584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouldali N, Bagheri H, Salvo F, et al. Hyper inflammatory syndrome following COVID-19 mRNA vaccine in children: a national post-authorization pharmacovigilance study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;17:100393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yousaf AR, Cortese MM, Taylor AW, et al. Reported cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children aged 12-20 years in the USA who received a COVID-19 vaccine, December, 2020, through August, 2021: a surveillance investigation. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2022;6:303–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karatzios C, Scuccimarri R, Chedeville G, et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in two children. Pediatrics. 2022;150:e2021055956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holm M, Espenhain L, Glenthoj J, et al. Risk and phenotype of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in vaccinated and unvaccinated Danish children before and during the omicron wave. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:821–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wisniewski M, Chun A, Volpi S, et al. Outcomes after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination among children with a history of multisystem inflammatory syndrome. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e224750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoste L, researchers M-C, Soriano-Arandes A, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination in children with a history of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: an international survey. J Pediatr. 2022;248:114–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCrindle BW, Rowley AH, Newburger JW, et al. Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a scientific statement for health professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e927–e999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CDC. Information for Healthcare Providers about Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C). 2021. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mis/mis-c/hcp/index.html. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- 15.Burns JC. Frequently asked questions regarding treatment of Kawasaki disease. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2017;2017:e201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satis H, Cindil E, Atas N, et al. Successful treatment of coronary artery aneurysm with infliximab in a Behcet’s disease patient. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:e10–e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson LA, Canna SW, Friedman KG, et al. American College of Rheumatology Clinical Guidance for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children associated with SARS-COV-2 and hyperinflammation in pediatric COVID-19: version 3. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2022;74:e1–e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ouldali N, Toubiana J, Antona D, et al. Association of intravenous immunoglobulins plus methylprednisolone vs immunoglobulins alone with course of fever in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children. JAMA. 2021;325:855–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zambrano LD, Nerhams MM, Olson SM, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) mRNA vaccination against multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children among persons aged 12–18 years—United States, July–December 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC. Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines currently approved or authorized in the United States. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/clinical-considerations/interim-considerations-us.html#covid19-vaccination-misc-misa. 2022. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- 21.CDC. Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment (CISA) Project. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/cisa/index.html. 2020. Accessed July 21, 2022.

- 22.LaRussa PS, Edwards KM, Dekker CL, et al. Understanding the role of human variation in vaccine adverse events: the clinical immunization safety assessment network. Pediatrics. 2011;127(Suppl 1):S65–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]