Background:

Coronavirus disease 2019 [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)] infection at varying time points during the pregnancy can influence antibody levels after delivery. We aimed to examine SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgM and IgA receptor binding domain of the spike protein and nucleocapsid protein (N-protein) reactive antibody concentrations in maternal blood, infant blood and breastmilk at birth and 6 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection in early versus late gestation.

Methods:

Mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy were enrolled between July 2020 and May 2021. Maternal blood, infant blood and breast milk samples were collected at delivery and 6 weeks postpartum. Samples were analyzed for SARS-CoV-2 spike and N-protein reactive IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies. Antibody concentrations were compared at the 2 time points and based on trimester of infection (“early” 1st/2nd vs. “late” 3rd).

Results:

Dyads from 20 early and 11 late trimester infections were analyzed. For the entire cohort, there were no significant differences in antibody levels at delivery versus 6 weeks with the exception of breast milk levels which declined over time. Early gestation infections were associated with higher levels of breastmilk IgA to spike protein (P = 0.04). Infant IgG levels to spike protein were higher at 6 weeks after late infections (P = 0.04). There were strong correlations between maternal and infant IgG levels at delivery (P < 0.01), and between breastmilk and infant IgG levels.

Conclusions:

SARS-CoV-2 infection in early versus late gestation leads to a persistent antibody response in maternal blood, infant blood and breast milk over the first 6 weeks after delivery.

Keywords: COVID-19, vertical transmission, antibodies, breast milk

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)] has affected a growing number of pregnant people in the US Emerging surveillance data have shown that pregnant individuals may be at increased risk of a severe outcome following SARS-CoV-2 infection, though most experience mild disease.1–3 SARS-CoV-2 continues to pose significant risks during pregnancy including increased risk for severe maternal morbidity, preterm delivery, caesarian section delivery and venous thromboembolism.4,5

Although research on this continues to evolve, viremia in the infant or vertical transmission has been identified in a range of 1%–7% of COVID-19 cases during pregnancy.6–8 The primary method of transmission is thought to be related to the placenta.9–11 Maternal immunoglobulin (Ig) M antibodies typically do not transfer through the placenta at high rates, and such studies use its presence in infants as evidence of viremia.12–14 Presence of SARS-CoV-2–specific IgG represents passive transfer of maternal antibody or infant response to infection.9,15

Although severity of COVID-19 disease in pregnancy does not affect the degree of transplacental antibody transfer, preliminary studies have suggested that increased antibody transfer appears to correlate with time between onset of maternal infection and delivery.9,13,16 Individuals infected with COVID-19 earlier in the pregnancy were found to have increased transplacental transfer which correlated positively with length of time from infection to delivery.13,17 Prior studies have not examined the full scope of antibody profiles in the neonate serially over time after infection at various trimesters of pregnancy.

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through breast milk has not been reported. Breastfeeding continues to be encouraged for those with COVID-19 infection given the overwhelming benefits to parental and infant health.18,19 Passive humoral immunity after birth can occur through breastmilk containing IgA antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Unvaccinated pregnant persons with COVID-19 infection produce robust quantities of antispike protein IgA, and lesser amounts of IgG.19,20 Variability in breast milk concentrations by trimester of infection and duration of this response remains understudied.

The primary aim of the study was to examine SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgM and IgA receptor binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein and nucleocapsid protein (N-protein) reactive antibody concentrations in maternal blood, infant blood and breastmilk at birth and 6 weeks after delivery after SARS-CoV-2 infection in early gestation (1st or 2nd trimester) versus late gestation (3rd trimester) infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patient Population

Boston Medical Center (BMC) is the largest urban safety-net hospital in New England. The hospital has approximately 3000 births per year in the Labor and Delivery Unit with majority of women being from minority groups with comorbidities, characteristics associated with severe SARS-CoV-2 disease.21,22 BMC performed universal screening of all women who presented in labor since April 2020. Infants of mothers who were positive at the time of delivery had routine care nasopharyngeal swabs obtained for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 and 48 hours after delivery.

We enrolled mother–infant dyads from the obstetric clinics, Labor and Delivery and the Postpartum Unit between July 2020 and May 2021 in this prospective cohort study. Eligible individuals had to be at least 18 years of age, have a documented SARS-CoV-2 infection at any point during pregnancy [positive nasopharyngeal swab Polymerase chain reaction (PCR)], have a viable singleton gestation pregnancy, no COVID-19 vaccination during the pregnancy, speak English or Spanish and give birth at BMC. Mothers were not approached if they were critically ill, in active labor or immediately postpartum, or if they did not have custody of their infant.

Mothers who were SARS-CoV-2 positive at the time of delivery were consented remotely per hospital guidelines. Phone interpreters were used for Spanish-speaking patients. This study was approved by the Boston University Medical Campus Institutional Review Board.

Sample Collection

Approximately 5 mL of maternal blood and cord blood, and 0.5–1 mL of infant blood was collected in a red top serum tube during the delivery hospitalization. Breast milk samples (1–3 mL) were collected through hand expression or breast pump. Six weeks after delivery, the dyad returned for a follow-up visit for collection of maternal and infant blood samples, and a repeat breastmilk sample. Samples were transported to our BLS-2 plus research laboratory. Blood samples were centrifuged and plasma was extracted and frozen at −80°C until analysis.

Laboratory Methods

Antibodies reactive to SARS-CoV-2 RBD spike protein and nucleocapsid protein (N-protein) were assayed from plasma following the BU enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay protocol.23 Briefly, wells of 96-well plates (Pierce 96-Well Polystyrene Plates; cat#15041, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) were coated with 50 µL/well of a 2 µg/mL solution of each respective protein in sterile PBS (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) or with PBS only for 1 hour at room temperature before washing with PBS 3 times using a multichannel pipettor. Next, 200 µL of casein blocking buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, cat#37528) was added to wells at room temperature for 1 hour. Next, plates were washed 3 times as previously described. Subject samples and monoclonal SARS-CoV-2 RBD reactive antibodies (IgG, clone CR3022, gift from the Alter lab at Ragon Institute; IgA, clone CR3022, Absolute Antibodies; IgM, clone BIB116, Creative Diagnostics, Shirley, NY) were diluted in Thermo Fisher casein blocking buffer, and 50 µL of each were added to the plates for 1 hour at room temperature, with dilution buffer only added to blank wells. After incubation, plates were again washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and immediately antihuman horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies for IgG (cat#A18817, Thermo Fisher, 1:2000), IgM (cat#A18841, Thermo Fisher, 1:8000) and IgA (Jackson Immunoresearch, cat#109-035-011, 1:2000) diluted in casein blocking buffer were added to the plates at 50 µL per well for 30 minutes at room temperature. Next, plates were washed 4 times with 0.05% PBST as described, and 50 µL per well of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine-enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay substrate solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, cat# 34029) was added and incubation occurred in the dark until a visible color difference between the well with the seventh dilution (1.37 ng/mL) of recombinant antibody and the diluent only “zero” well appeared, this time ranged from ~8 to 20 minutes. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 µL of stop solution for 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, cat#N600) and the optical density (OD) was measured at 450 nm (OD 450 nm) on a Synergy HT Multi-Detection Microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) using the accompanying Gen5 software, Albuquerque, NM. Sample dilutions (ranging from 1:5 to 1:500, depending on sample type and isotype detected) were run in uncoated (PBS only) and paired antigen-coated wells. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA. Arbitrary units (AU) on a ng/mL scale were calculated as previously described from the OD values according to standard curves generated by known amounts of monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 spike protein IgG, IgM or IgA.22 Cut-offs for the assays were determined based on the validated BU protocol.22

Data Abstraction

Electronic medical records of the dyads were reviewed and demographic characteristics such as race, ethnicity and age at delivery recorded in a secure electronic database. Pregnancy dating was based on best obstetrical estimate, first trimester ultrasound or last menstrual period if early ultrasound data were not available. Other maternal data points such as history of chronic illnesses and pregnancy-related diagnoses were collected. For infants, demographics and birth parameters as well as COVID-19 testing status in the first 6 weeks of life were reviewed. Details of all vaccinations received during the pregnancy were reviewed. Once the COVID-19 vaccine was made available, participants completed a brief survey at the time of delivery on vaccination history.

All mothers completed a brief electronic questionnaire at the 6-week visit, that queried details of the home environment and infant caretakers, risk of COVID-19 exposures, precautions practices, breastfeeding practices, known exposures to COVID-19 after discharge, COVID-19 symptoms in the mother or infant and any health care encounters or hospitalizations since discharge.

Statistical Methods

A subset of 31 dyads for which maternal and infant samples were available at 2 time points was selected for this pilot analysis from our larger enrolled cohort. Demographic characteristics, maternal, and neonatal outcomes were summarized for the dyads. Categorical variables were reported as percentages [n (%)] and continuous variables reported as either mean with standard deviation [mean (standard deviation)] or median with interquartile range [median (interquartile range)], where appropriate.

Mean and standard deviations for each antibody type were then determined for each specimen type. Antibody concentrations in maternal, infant and breast milk samples were compared at the 2 time points and based on trimester of infection (“early” 1st/2nd vs. “late” 3rd trimester) using t tests with mean differences (95% confidence interval) determined. Correlations were then examined between antibody levels based on specimen type and time point. An α level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. Repeat chart abstractions were conducted to identify any missing clinical data points. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Demographics

We identified 146 individuals with COVID-19 who delivered at BMC during the recruitment period. Twenty were not eligible for the study due to twin gestation (n = 1), non-English or Spanish speaking (n = 11), screened out by providers (n = 3), maternal age <18 years (n = 3) or Intensive care unit admission during screening (n = 2). Of 126 eligible individuals, 85 were approached for consent, 60 individuals enrolled and 31 dyads with samples available at the 2 time points included in this pilot study (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/INF/E897).

Demographics of the dyads are shown in Table 1. The study population was reflective of our ***BMC population with 80.6% identifying as non-White race, 67.7% as Hispanic ethnicity, 54.8% with a chronic health condition and 90.3% with pregnancy complications (Table 1). There was one first, 19 second and 11 third trimester infections. Most (90.3%) mothers exhibited symptoms and 12.9% were hospitalized for their infection during the pregnancy. The 6 infants born to mothers who were COVID-19 positive at the time of delivery were evaluated and had negative nasopharyngeal SARS-CoV-2 PCRs at 24 and 48 hours after birth. All infants were born >35 weeks gestational age and none had symptoms of COVID-19 during the neonatal period.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of the 31 Mother–Infant Dyads With COVID-19 in Pregnancy

| Variable | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery (y) | 29.6 (5.7) |

| Maternal race | |

| Black | 5/31(16.1%) |

| White | 6/31 (19.4%) |

| Asian | 2/31(6.4%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 16/31 (53.3%) |

| Middle Eastern | 1/31 (3.3%) |

| Maternal ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 21/31 (67.7%) |

| Non-Hispanic | 10/31(32.3%) |

| Maternal chronic health conditions | 17/31(54.8%) |

| Diabetes | 0 (0%) |

| Hepatitis C or HIV infection | 0 (0%) |

| Hypertension | 1/31 (3.2%) |

| Obesity | 2/31(6.5%) |

| Substance use disorder | 3/31 (9.7%) |

| Other chronic health condition | 15/31 (48.4%) |

| Pregnancy comorbidities | 28/31 (90.3%) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 5/31 (16.1%) |

| Gestational diabetes | 4/31 (12.3%) |

| Hypertension disorder of pregnancy | 7/31 (22.6%) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 7/31 (22.6%) |

| Preterm labor | 3/31 (9.7%) |

| Other | 19/31 (61.3%) |

| Delivery mode | |

| Vaginal | 17/31 (54.8%) |

| Cesarean section | 14/31 (45.2%) |

| Trimester of maternal COVID-19 infection | |

| First | 1/31 (3.2%) |

| Second | 19/31 (61.3%) |

| Third | 11/31 (35.5%) |

| GA (wk) at time of COVID-19 infection | 23.8 (8.2) |

| Days between COVID-19 diagnosis and delivery | 104.2 (59.1) |

| Maternal symptoms of COVID-19 at any point | 28/31 (90.3%) |

| Maternal hospitalization for COVID-19 | 4/31 (12.9%) |

| Maternal COVID-19 status at delivery | |

| Positive | 6/31 (19.3%) |

| Negative | 25/31 (80.7%) |

| Gestational age at delivery (wk) | 38.6 (2.3) |

| Infant birth weight (g) | 3214.6 (664.3) |

| Infant sex | |

| Male | 14/31 (45.2%) |

| Female | 17/31 (54.8%) |

| Infant breastfed during birth hospitalization | 29/31 (93.6%) |

| Infant signs or symptoms of COVID-19 at delivery | 0 (0%) |

| Infant positive COVID-19 PCR test within 30 d | 0 (0%) |

ER indicates emergency room; GA, gestational age; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; SD, standard deviation.

On the 6-week surveys, most participants reported caregivers other than the parents living in the home and/or caring for the infant, and most (76.7%) reported household members who worked outside of the home. Only 1 participant reported a new COVID-19 contact during the previous 6 weeks. None of the mothers had received a COVID-19 vaccination in the 6 weeks since delivery. One infant was admitted for evaluation of poor feeding, and 2 were seen and discharged from the emergency department with symptoms unrelated to COVID-19. None of the mothers or infants was diagnosed with COVID-19 since the birth hospitalization.

Delivery and 6-week Antibody Levels

SARS-CoV-2 antibodies were detected at birth and 6 weeks from all samples. Overall, spike and N-protein antibody levels declined over the first 6 weeks after delivery in infant blood and breast milk samples, while levels increased in maternal blood. Breast milk IgA (P = 0.009) and IgM (P = 0.04) to N-protein demonstrated a statistically significant decline over the 2 time points (Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/INF/E898).

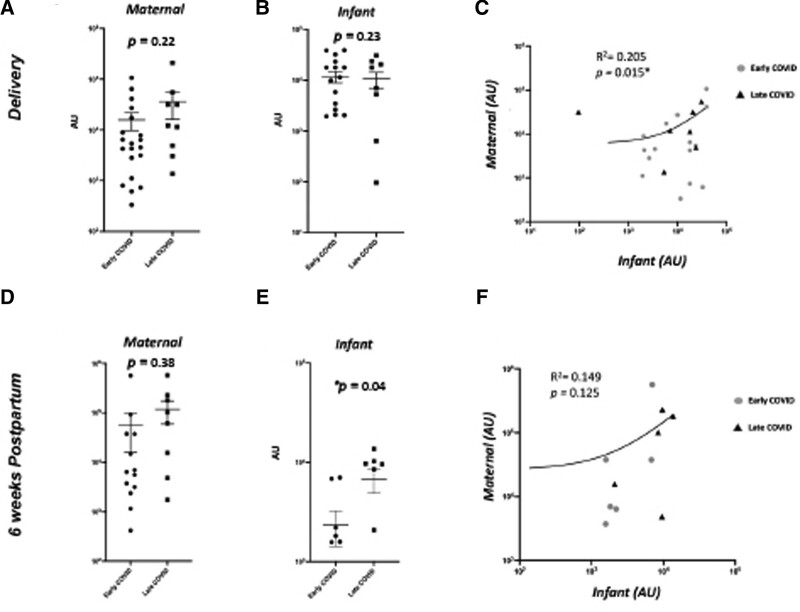

Maternal blood and infant blood IgG levels at delivery were highly correlated for both the spike protein (R = 0.87, P < 0.0001) and N-protein (R = 0.47, P = 0.009; Fig. 1). Maternal and infant blood IgA to N-protein at 6 weeks were also highly correlated (R = 0.72, P = 0.001). There were no correlations between maternal and infant samples for IgM levels at either time point (Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/INF/E899).

FIGURE 1.

Maternal and infant serum IgG responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in early versus late infections at delivery and 6 wk. A, B, D, E: Serum IgG levels from maternal (A) and infant (B) samples at delivery, maternal (D) and infant (E) samples at 6 wk in early (2nd trimester) vs. late (3rd trimester) COVID-19 infections in pregnancy. C, F: Correlation analysis of maternal–infant dyad antibody expression at birth (C) and at 6 wk (F). AU greater than 0 expressed as log 10 values of antibody abundance.

There were 3 infants in which the cord blood (n = 2) or infant blood (n = 1) sample at delivery had an IgM value for the spike protein of >200 AU (range 230–1987 AU); all cases were earlier third trimester infections in which the mothers were asymptomatic by the time of delivery. None of the infants had PCR testing or neonatal signs of COVID-19. The remainder of the detectable infant IgM values at delivery (n = 10) were primarily from cord blood with values <80 AU. There were also 6 infants with a positive IgM to the spike protein at the 6-week follow-up visit, with values ranging from 18 to 108 AU.

Comparison of Early Versus Late Gestation Infections

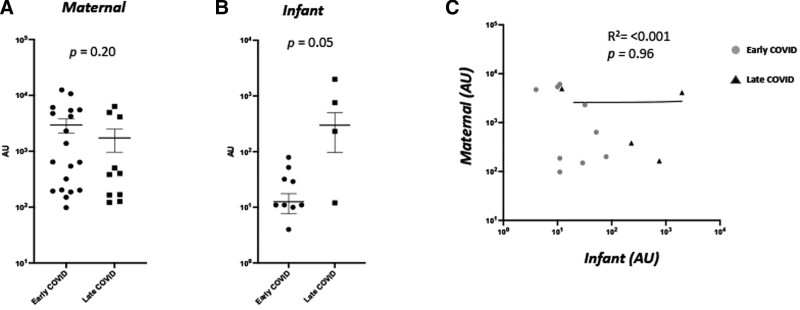

Maternal and infant IgM antibody concentrations measured at both time of delivery and 6 weeks later did not differ significantly by time of infection during gestation (Fig. 2). There were no differences in maternal or infant IgG levels to the spike protein or N-protein at delivery based on timing of infection. Infant IgG levels at the 6-week time point were higher in late trimester infections compared with early trimester infections (P = 0.04; Fig. 1). There were no differences in maternal or infant IgA levels at either time point based on timing of maternal infection (Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/INF/E900, Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/INF/E901).

FIGURE 2.

Maternal and infant serum IgM responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in early versus late infections at delivery and 6 wk. A and B: Maternal (A) and infant (B) IgM levels against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in early (2nd trimester) vs. late (3rd trimester) COVID-19 infections in pregnancy. C: Correlation analysis of maternal–infant dyad antibody expression. AU greater than 0 expressed as log 10 values of antibody abundance.

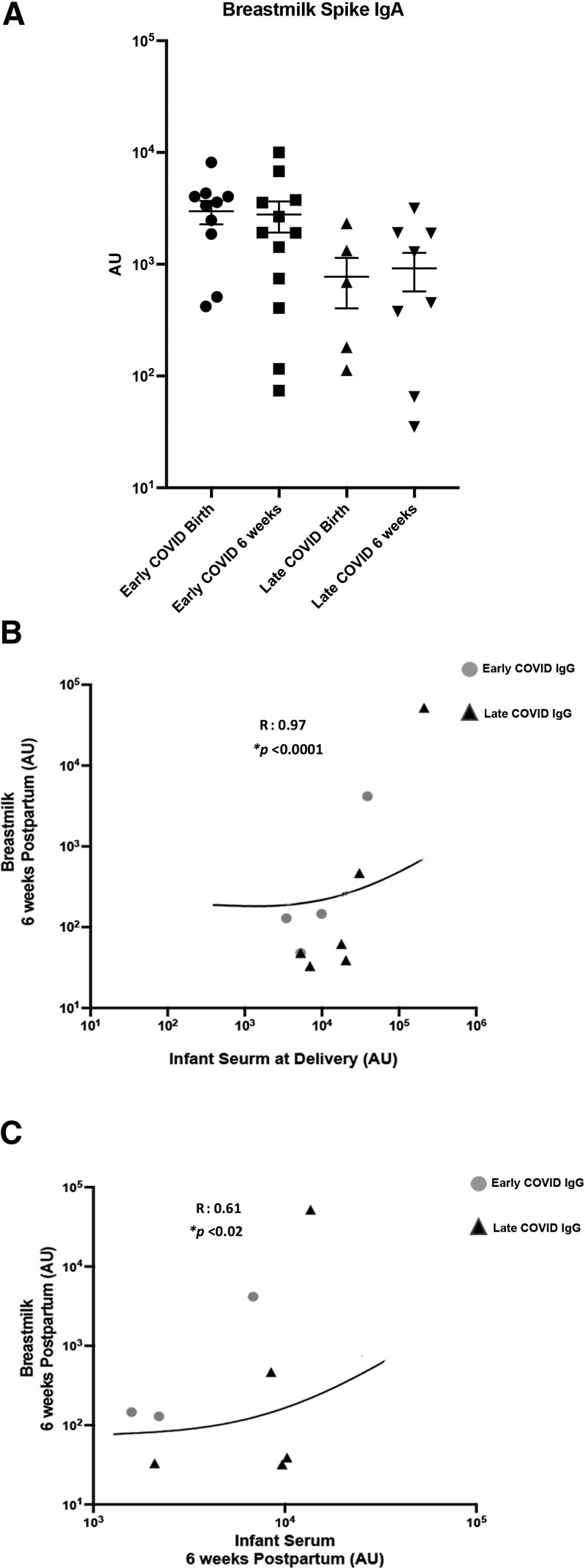

Breastmilk Antibody Levels

There were higher levels of breast milk spike protein IgA at delivery after early gestation infections compared with late gestation (P = 0.04; Fig. 3). No other significant differences in breastmilk antibody levels were seen at the 2 time points based on timing of maternal infection (Supplemental Digital Content 5, http://links.lww.com/INF/E901).

FIGURE 3.

Breastmilk IgA levels against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in early vs. late infections at delivery and 6 wk. A: Breastmilk IgA levels against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein at birth and 6 wk following delivery in early COVID vs. late COVID groups. B: Correlation of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in infant serum at delivery and breastmilk 6 wk postpartum in early COVID vs. late COVID groups. C: Correlation of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein in infant serum and breastmilk 6 wk postpartum early COVID vs. late COVID groups. AU greater than 0 expressed as log 10 values of antibody abundance.

In examination of correlations between infant blood samples and breast milk antibody levels, IgG levels of N-protein were correlated at the delivery time point (R = 0.52, P = 0.04) and IgG to the spike protein in infant blood at both delivery and 6 weeks with the 6-week breastmilk samples (P < 0.05; Fig. 3). There were no significant correlations between cord blood levels and IgM or IgA levels in the breast milk at either time point (Supplemental Digital Content 6, http://links.lww.com/INF/E902).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to include primarily second trimester COVID-19 infections, as well as the serial sampling of maternal, infant and breast milk samples over the first 6 weeks after birth. We identified that SARS-CoV-2 infection in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy leads to persistent antibody responses that are detected for at least 6 weeks postpartum. Given there was only 1 first trimester infection in our cohort, we are unable to draw conclusions from this time period of infection. The persistence of IgG and IgA in infant serum and breast milk that our study demonstrates contributes to our understanding of the lack of severe COVID-19 infection in infants exposed to the virus in utero.

Our study is consistent with a 2020 systematic review of 6 studies that examined infant IgG and IgM antibody to SARS-CoV-2 after maternal infection during pregnancy; IgG and IgM antibodies were detected in 90% of infants who tested negative by PCR for COVID-19.24 One previous study examined IgG to SARS-CoV-2 in maternal and infant blood in a small number of first trimester (n = 3) and second trimester (n = 3) infections and found detectable levels at the time of delivery.25 Another study of 83 mothers found efficient transfer of IgG antibodies from women who were SARS-CoV-2 seropositive, and a positive correlation between maternal and cord antibody concentrations.13

Our study uniquely found that IgM antibodies were detectable, primarily in very low levels, in infant serum or cord blood in most samples at delivery and 6-week samples in the absence of other evidence of infant infection. Even though IgG is passively transferred across the placenta from mother to fetus, IgM usually is not transferred from mother to fetus because of its larger macromolecular structure.26 In a small study of 6 mothers with SARS-CoV-2, IgM was detected in 2 infants.27 A study by Edlow et al9 examined cord blood samples from 77 infants after maternal infections around the time of delivery and found only 1 infant with detectable IgM to NP. Similarly, in another study of 31 cases where mothers were positive at the time of delivery, IgM was detected only in 1 cord blood sample while IgG was detected in 40%.28 Thus, the high number of infant samples with detectable IgM in our study could represent differences in the assays used, cord blood contamination by maternal blood, or cross-reactivity with other antibodies. The BU enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay method is more sensitive than other methods, likely related to the manual washing; the method has been demonstrated to be able to detect very low amounts of antibody, which are of unclear clinical significance.23 In addition, recent studies have indicated the lack of specificity of anti-N antibodies, particularly in the setting of recent vaccination.29 It is also possible this represents true infection in some infants transplacentally, as noted by the highest infant IgM at delivery in third trimester infections.

There is also the possibility of postpartum transmission given the high-risk exposures in this population as evidenced by the new IgM positivity in some of the 6-week infant samples. None of the infants had clinical symptoms over the first 6-weeks after birth, perhaps related to protection from the maternal transferred IgG and IgA antibodies. Given there was no clinical indication for PCR testing, these infants did not have corresponding PCR results for comparison which is a limitation of the study.

Maternal antibody levels overall increased over the 6 weeks postpartum, perhaps due to the increased immunocompetence, or due to the timing of the COVID-19 infection relative to the timing of delivery with a likely convalescent response in those who had infections closer to the time of delivery.30–32 Higher maternal antibody concentrations and a higher transfer ratio were associated with increasing duration between onset of maternal infection and time of delivery.13 Multiple other factors, such as antigen-elicited IgG subclass, maternal infections, maternal immunodeficiency, placental pathology and gestational age at birth, are known to affect transfer efficiency and will require further study.31–33

Our study is consistent with other studies that demonstrated that antibodies, specifically IgA, can be present in the breast milk up to 5–6 months after infection, but that IgA levels decline in breast milk over time.34,35 Other studies have examined IgG and IgM to SARS-CoV-2 in breastmilk samples but only within the first week after delivery. Our results support the existing national guidelines that breastfeeding is safe and recommended in the setting of maternal COVID-19 infection and can transfer protective antibodies through the breastmilk.36,37

Our study has several limitations, including our small sample size, inclusion of only 1 first trimester infection, and lack of PCR testing for SARS-CoV-2 in all infants. We were required at the time of the study to limit PCR testing to infants for whom it was indicated per clinical care protocols. Also, an in-depth analysis by trimester of infection or by maternal severity of COVID-19 illness was not possible due to the small sample size. Demographic characteristics, disease severity or antibody concentrations for those who declined the study or were not approached to offer participation due to severity of illness may also have differed from those who agreed to participate. Other limitations include lack of mothers who were vaccinated, or who were infected with the Delta or Omicron variants, limiting our ability to determine the impact of these variables on antibody levels. In addition, we did not collect information on timing of breastmilk collection relative to the infant feed, which can influence antibody levels in the breastmilk.

In summary, this study demonstrates that infection with COVID-19 in the second and third trimesters of pregnancy results in antibody transfer to the infant with sustained antibodies throughout the first 6-weeks postdelivery. We also demonstrated differences in antibody levels based on timing of infection during the pregnancy, characterized the breast milk antibody patterns over time and demonstrated correlations between antibody levels. Future studies should enroll a larger sample size of varying trimesters of infection with a focus on first trimester infections, assess the impact of various COVID-19 variants on antibody response in the infant, and examine the impact of COVID-19 vaccination status during pregnancy on antibody levels over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the staff from the Boston Medical Center Labor and Delivery Unit, Postpartum Unit, and Newborn Intensive Care Unit who assisted us with recruitment and facilitation of sample collection, especially Kate Thibault, RN; Lauren Laliberte, RN; Brianna Medeiros, RN, NP; Elizabeth Regan, RN and Joanna Bushfield, RN. We would also like to acknowledge the Maxwell Finland Laboratory of Pediatric Infectious Disease at Boston Medical Center (Yazdan Shaik-Dasthagirisaheb and Loc Truong), and the Boston University NEIDL laboratory of microbiology.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This study was supported with funding from the Boston University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (1UL1TR001430 to E.D.B. and E.M.W.).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

E.S.T. and V.S. contributed equally as senior authors.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (www.pidj.com).

Contributor Information

Jennifer Snyder-Cappione, Email: cappione@bu.edu.

Jeffery Boateng, Email: jboateng@bu.edu.

Renee Ferraro, Email: Renee.Ferraro@bmc.org.

Sigride Jean-Sicard, Email: Sigride.Jean-Sicard@bmc.org.

Elizabeth Woodard, Email: Elizabeth.Taglauer@bmc.org.

Alice Cruikshank, Email: Alice.Cruikshank@bmc.org.

Bharati Sinha, Email: Bharati.Sinha@bmc.org.

Ruby Bartolome, Email: Ruby.Bartolome@bmc.org.

Elizabeth D. Barnett, Email: Elizabeth.Barnett@bmc.org.

Christina Yarrington, Email: Christina.Yarrington@bmc.org.

Elizabeth S. Taglauer, Email: Elizabeth.Taglauer@bmc.org.

Vishakha Sabharwal, Email: Vishakha.Sabharwal@bmc.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Di Toro F, Gjoka M, Di Lorenzo G, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson JL, Nguyen LM, Noble KN, et al. COVID-19-related disease severity in pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;84:e13339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kucirka LM, Norton A, Sheffield JS. Severity of COVID-19 in pregnancy: a review of current evidence. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2020;84:e13332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrara A, Hedderson MM, Zhu Y, et al. Perinatal complications in individuals in California with or without SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182:503–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Allotey J, Stallings E, Bonet M, et al. ; for PregCOV-19 Living Systematic Review Consortium. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ovali F. SARS-CoV-2 infection and the newborn. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabharwal V, Bartolome R, Hassan SA, et al. Mother-infant dyads with COVID-19 at an urban, safety-net hospital: clinical manifestations and birth outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kotlyar AM, Grechukhina O, Chen A, et al. Vertical transmission of coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:35–53.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edlow AG, Li JZ, Collier A-RY, et al. Assessment of maternal and neonatal SARS-CoV-2 viral load, transplacental antibody transfer, and placental pathology in pregnancies during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2030455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taglauer E, Benarroch Y, Rop K, et al. Consistent localization of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein and ACE2 over TMPRSS2 predominance in placental villi of 15 COVID-19 positive maternal-fetal dyads. Placenta. 2020;100:69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyle MH, Hussain M, Saltz V, et al. Vertical transmission and neonatal outcomes following maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2022;65:195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong L, Tian J, He S, et al. Possible vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from an infected mother to her newborn. JAMA. 2020;323:1846–1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flannery DD, Gouma S, Dhudasia MB, et al. Assessment of maternal and neonatal cord blood SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and placental transfer ratios. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:594–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Hur H, Gurevich P, Elhayany A, et al. Transport of maternal immunoglobulins through the human placental barrier in normal pregnancy and during inflammation. Int J Mol Med. 2005;16:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Flores V, Romero R, Xu Y, et al. Maternal-fetal immune responses in pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat Commun. 2022;13:320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atyeo C, Pullen KM, Bordt EA, et al. Compromised SARS-CoV-2-specific placental antibody transfer. Cell. 2021;184:628–42.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song D, Prahl M, Gaw SL, et al. Passive and active immunity in infants born to mothers with SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e053036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hand IL, Noble L. Covid-19 and breastfeeding: what’s the risk? J Perinatol. 2020;40:1459–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pace RM, Williams JE, Järvinen KM, et al. COVID-19 and human milk: SARS-CoV-2, antibodies, and neutralizing capacity. medRxiv. 2020:2020.09.16.20196071. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao X, Wang S, Zeng W, et al. Clinical and immunologic features among COVID-19-affected mother-infant pairs: antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 detected in breast milk. New Microbes New Infect. 2020;37:100752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. ; STOP-COVID Investigators. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:1436–1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aldridge RW, Lewer D, Katikireddi SV, et al. Black, Asian and minority ethnic groups in England are at increased risk of death from COVID-19: indirect standardization of NHS mortality data. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuen RR, Steiner D, Pihl RMF, et al. Novel ELISA protocol links pre-existing SARS-CoV-2 reactive antibodies with endemic coronavirus immunity and age and reveals improved serologic identification of acute COVID-19 via multi-parameter detection. Front Immunol. 2021;12:614676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bwire GM, Njiro BJ, Mwakawanga DL, et al. Possible vertical transmission and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 among infants born to mothers with COVID-19: a living systematic review. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1361–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kashani-Ligumsky L, Lopian M, Cohen R, et al. Titers of SARS CoV-2 antibodies in cord blood of neonates whose mothers contracted SARS CoV-2 (COVID-19) during pregnancy and in those whose mothers were vaccinated with mRNA to SARS CoV-2 during pregnancy. J Perinatol. 2021;41:2621–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohler PF, Farr RS. Elevation of cord over maternal IgG immunoglobulin: evidence for an active placental IgG transport. Nature. 1966;210:1070–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng H, Xu C, Fan J, et al. Antibodies in infants born to mothers with COVID-19 Pneumonia. JAMA. 2020;323:1848–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fenizia C, Biasin M, Cetin I, et al. Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 vertical transmission during pregnancy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Follman D, Janes HE, Buhule OD, et al. Anti-nucleocapsid antibodies following SARS-CoV-2 infection in the blinded phase of the mRNA-1273 Covid-19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:e1258–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mor G, Cardenas I. The immune system in pregnancy: a unique complexity. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2010;63:425–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Racicot K, Kwon J-Y, Aldo P, et al. Understanding the complexity of the immune system during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;72:107–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mo H, Zeng G, Ren X, et al. Longitudinal profile of antibodies against SARS-coronavirus in SARS patients and their clinical significance. Respirology. 2006;11:49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Yang P, Zheng J, et al. Dynamic changes of acquired maternal SARS-CoV-2 IgG in infants. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncombe CJ, McCulloch DJ, Shuey KD, et al. Dynamics of breast milk antibody titer in the six months following SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Virol. 2021;142:104916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Juncker HG, Romijn M, Loth VN, et al. Human milk antibodies against SARS-CoV-2: a longitudinal follow-up study. J Hum Lact. 2021;37:485–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flannery DD, Puopolo KM. Perinatal COVID-19: guideline development, implementation, and challenges. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2021;33:188–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang N, Che S, Zhang J, et al. ; COVID-19 Evidence and Recommendations Working Group. Breastfeeding of infants born to mothers with COVID-19: a rapid review. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]