Abstract

Across the lifespan most sexual minority individuals experience the closet – a typically prolonged period in which no significant others know their sexual identity. This paper positions the closet as distinct from stigma concealment given its typical duration in years and absolute remove from sources of support for an often-central identity typically during a developmentally sensitive period. The Developmental Model of the Closet proposed here delineates the vicarious learning that takes place before sexual orientation awareness to shape one’s eventual experience of the closet; the stressors that take place after one has become aware of their sexual orientation but has not yet disclosed it, which often takes place during adolescence; and potential lifespan-persistent mental health effects of the closet, as moderated by the structural, interpersonal, cultural, and temporal context of disclosure. The paper outlines the ways the model draws upon and is distinct from earlier models of sexual minority identity formation and proposes several testable hypotheses and future research directions, including tests of multilevel interventions.

Keywords: sexual orientation, minority stress, stigma, concealment, disclosure

“The gay closet is not a feature only of the lives of gay people. But for many gay people it is still the fundamental feature of social life; and there can be few people, however courageous and forthright by habit, however fortunate in the support of their immediate communities, in whose lives the closet is not still a shaping presence.”

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (1990; p. 68).

Coming out of the closet refers to the psychosocial experience of disclosing, in some form, one’s sexual minority status to others. Social scientists have long viewed coming out as a critical milestone within sexual minority identity development (Cass, 1979; Rosario et al., 2001; Rosario et al., 2004; Troiden, 1979). The importance of the personal shift represented by the act of coming out—and its relationship to psychological adjustment—is evidenced by the substantial empirical attention generated on the topic within the social and behavioral sciences (Jackson & Mohr, 2016; Pachankis, Mahon et al., 2020; Rosario et al., 2011). Despite the robust literature on coming out, empirical scholarship almost exclusively conceptualizes one’s outness and concealment as a gradient—the degree to which one discloses or conceals their sexual minority status after coming out to at least some people. For instance, this research assesses concealment among those who are out as the number and types of people to whom one has not disclosed (e.g., Meidlinger & Hope, 2014; Meyer et al., 2002; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000; Villicana et al., 2016), follows people over days or weeks to examine associations between their fluctuating levels of sexual identity concealment and mental health and social functioning (e.g., Beals et al., 2009; Pachankis et al., 2011); experimentally induces concealment by asking participants to hide a sexual minority identity in a given social interaction (Santuzzi & Ruscher, 2002); or as a trait-like tendency (e.g., Schrimshaw et al., 2013). Yet, by definition, people in the closet are not out to anyone; the closet demands absolute concealment rather than daily fluctuating concealed states; and people cannot be experimentally assigned to the closet, unlike concealment. Perhaps not surprisingly then, much less research attention focuses on the closet compared to concealment. Although the two constructs share some conceptual overlap – for instance, people in the closet conceal – people in the closet conceal entirely and not everyone who conceals is closeted; the two constructs are distinct. Despite accumulating research attention paid to coming out (and also despite the fact that the closet occupies a central place in the public imagination, as indexed by the numerous contemporary television series and movies featuring a closeted character), little research has conceptualized the experience of the closet itself.

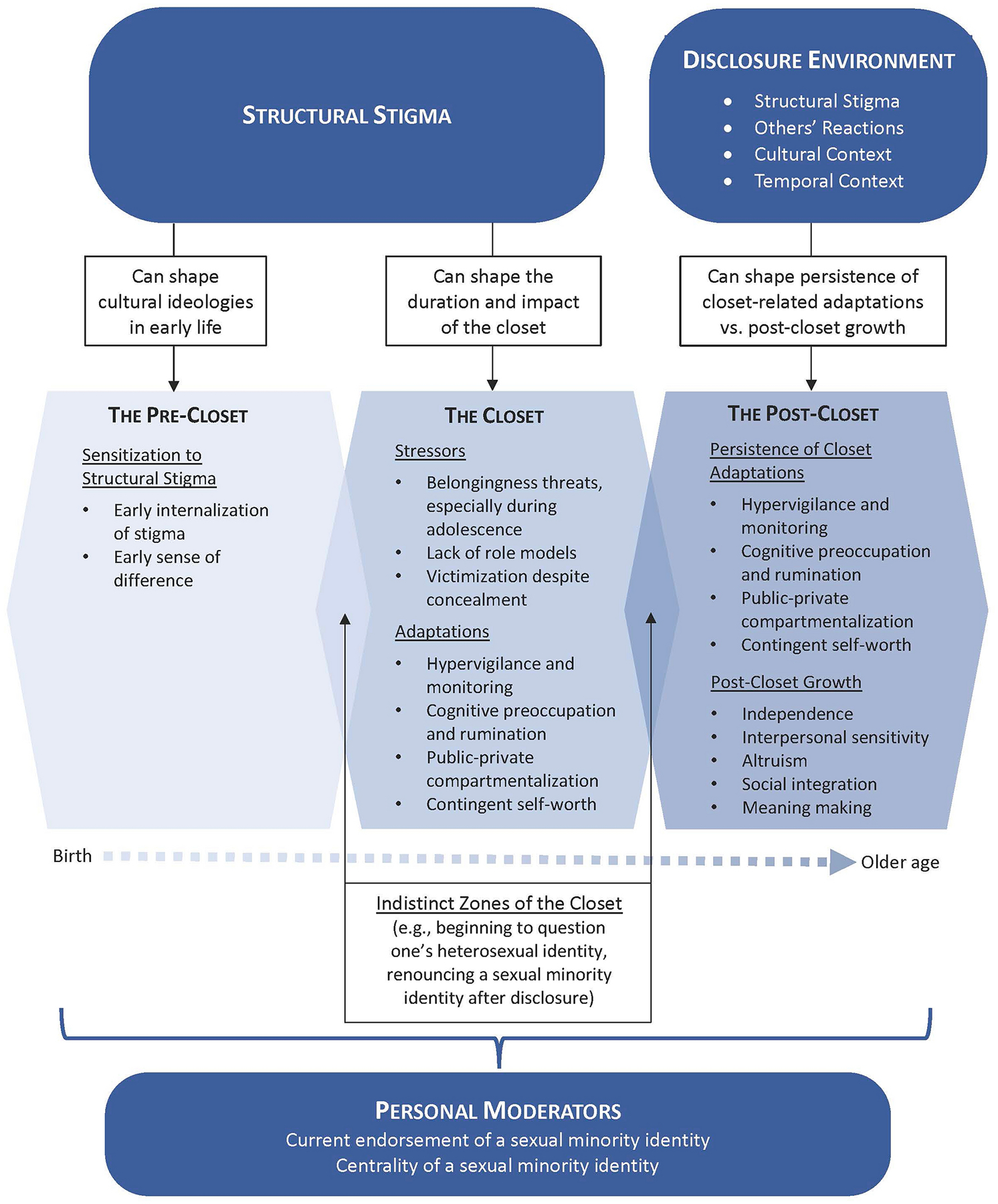

To guide future research, this paper presents the Developmental Model of the Closet that centers the experience of the sexual minority closet – the period between self-labeling and initial disclosure, and a relatively distinct feature of sexual minority development across cultures – to suggest how this period might influence mental health and social functioning. Although, as described in the opening quote, the closet has been recognized as an essential feature of sexual minority life in theoretical and social commentary, as well as in clinically derived models of identity development for several decades (Cass, 1996; Coleman, 1982; Morris, 1997; Troiden, 1989), emerging social science research since that time provides a new basis for an empirical understanding of the closet’s determinants and outcomes. Thus, the Developmental Model of the Closet is grounded in research from across psychological science and aims to spur even more targeted future research into the closet as a determinant of sexual minority mental health and social functioning. Specifically, the Developmental Model of the Closet focuses on the vicarious learning that takes place before sexual orientation awareness to shape one’s eventual experience of the closet and decisions about whether to come out; the stressors that take place after one has become aware of their sexual orientation but has not yet disclosed their sexual orientation to important others, which for many takes place during the developmentally sensitive period of adolescence; and the lifespan persistence of the closet’s effects on mental health and social functioning even if one comes out, as determined by features of the disclosure environment. Rather than assuming that the closet takes the same form or has an identical meaning across diverse sexual minority populations, the Developmental Model of the Closet allows for wide variation in the closet’s experience across sexual identities and fluidities, developmental timings, and cultures. Importantly, the Developmental Model of the Closet does not assume an imperative to come out of the closet, treat coming out as a necessary ideal, or make assumptions about the value or benefit of what one comes into by coming out (Klein et al., 2015; McLean, 2007). Instead, the model outlines the cultural ideologies that precede, orient, and sensitize one to their emerging identity and the stressful adaptations to the closet that can persist after coming out as well as provide opportunities for post-closet growth. The paper proposes testable hypotheses to guide future research and concludes by suggesting future needed research directions.

The scientific study of the closet has historically been hampered by several methodological challenges – some of which are recently surmountable, such as inclusion of outness assessments in population-based studies (e.g., Pachankis, Cochran, & Mays, 2015; van der Star et al., 2019) and prospective cohort studies of youth that assess sexual orientation identity starting early in development. (e.g., Irish et al., 2019; la Roi et al. 2016; Luk et al., 2018). However, some challenges cannot be resolved, including those inherent to studying a phenomenon in which an individual has yet to identify themselves as the identity being studied perhaps to themselves and perhaps more certainly to researchers (Stein, 1999). Attempts to resolve these latter types of challenges, such as retrospectively linking one’s current identities with their earlier experiences, will always be subject to certain bias (e.g., Pachankis, Clark, Dougherty, & Klein, 2021). The model proposed in this paper takes advantage of the most recent research into the developmental experience of the closet, prioritizing the most methodologically rigorous research, to encourage the strongest possible future study of the model’s tenets. Although the improving conditions in which some sexual minority individuals live today might make the opening quote by Sedgwick about the ubiquity of the closet seem anachronistic in certain contexts, this new empirical scholarship on the closet suggests that the closet and its determinants and outcomes remain contemporarily pervasive, a point that the Developmental Model of the Closet takes up as a primary tenet.

The Importance of Studying the Closet and Its Developmental Features

Every individual who comes to identify as a sexual minority will experience a period, no matter how short or long, during which only they, and no one else, will know their sexual orientation. Research shows that, even in relatively accepting social climates, sexual minorities typically conceal their sexual orientation across formative years of development, including all of adolescence (Calzo et al., 2011; Katz-Wise et al., 2017; Rosario et al., 2004). In fact, estimates suggest that of sexual minority adults worldwide, a large proportion, if not the majority, have disclosed their sexual orientation to few or no others (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019). Population-based studies in the US show that even for young sexual minorities today, the average period between self-identification as a sexual minority and first disclosure of that status is about three or four years (Calzo et al., 2011; Bishop et al., 2020). The same is true in a large sample of sexual minorities living across 28 European countries (Layland et al., 2022). Yet scant research has focused on elucidating the developmental experience of the closet and its potentially persistent mental health consequences, regardless of whether one eventually comes out.

This paper positions the closet as a central, yet under-examined, experience of sexual minority development that potentially wields a powerful and lasting impact on mental health and social functioning. The closet is defined here as the period of absolute sexual identity nondisclosure—that is, the period during which one both recognizes their sexual identity and has not disclosed it to anyone significant in their life. In this paper, we delineate three distinct developmental periods that concern the sexual minority closet: (1) the period before one is aware of their sexual minority identity but during which one is nonetheless learning the dominant cultural ideologies about sexual minorities and their social treatment (i.e., “the pre-closet”), (2) the period after one becomes aware of their sexual minority identity but has not disclosed it to any significant people in their life, often triggering a series of psychosocial stressors and adaptations during a sensitive developmental stage (i.e., “the closet”), and (3) for those who eventually disclose their sexual orientation, the period after coming out, during which one continues to contend with—and in some cases transform—the self-perceptions and coping strategies developed within earlier stages (i.e., “the post-closet”). This trajectory situates the experience of the sexual minority closet—whether days or decades in duration—as part-and-parcel of sexual minority identity development.

Distinction from Related Theoretical and Conceptual Models

The Developmental Model of the Closet differs substantially from early stage models of sexual identity formation (Bell & Weinberg, 1978; Boxer et al., 1991; Cass, 1996; Coleman, 1982; Harry, 1993; Morris, 1997; Troiden, 1989), which focus primarily on the formation of a sexual minority identity rather than the stressors and adaptations demanded by the closet (e.g., contingent self-worth, hypervigilance, compartmentalization). Informed by models of general lifespan identity development (Erikson, 1968; Marcia, 1966), these models of sexual minority identity development highlight the unfolding of an emerging personal awareness of oneself as a sexual minority individual into a public identity that integrates one’s stigmatized status into a fuller sense of self (Cass, 1979; Morris, 1997; Troiden, 1989). Empirical studies of these stage models find that movement toward an integrated sexual minority identity is associated with positive social functioning and mental health (Rosario et al., 2011). The Developmental Model of the Closet positions the closet as part of the larger general developmental experiences described by these models but, unlike those models, focuses solely on the closet. Also unlike these more general developmental models, the Developmental Model of the Closet is only a stage model to the extent that it recognizes the closet as a distinct period characterized by an absolute lack of disclosure despite self-identification as a sexual minority. As described in the opening quote by Sedgwick (1990) and numerous social theorists who have written both before and since her cogent analysis (e.g., Herdt, 1992; Humphreys, 1970; Foucault, 1980; Seidman et al., 1999), as long as sexual minority individuals have been recognized as an actual and distinct social group, and a stigmatized social group in Western contexts, they have reckoned with the reality of the closet – the sociological constraint imposed upon those for whom stigma denies full integration into public life and the psychological constraint against immediate open self-expression of one’s sexual identity upon initial self-discovery. Inspired by these theoretical writings of the closet as a sociological reality and the general psychological models of sexual minority identity development described above, the Developmental Model of the Closet positions the closet as a continuing key feature of sexual minority life with important implications for mental health and social functioning.

As mentioned above, the Developmental Model of the Closet also differs from the more general research on sexual orientation concealment (e.g., Beals et al., 2009; Meidlinger & Hope, 2014; Meyer et al., 2002; Mohr & Fassinger, 2000; Pachankis et al., 2011; Santuzzi & Ruscher, 2002; Schrimshaw et al., 2013; Villicana et al., 2016). Perhaps because out sexual minorities are easier to recruit into research than those who are not out (Ferlatte et al., 2017; Salway et al., 2019), concealment has enjoyed more empirical research than the closet, and though important, it does not offer a complete picture of the contexts and outcomes of sexual minority individuals’ experiences of absolute concealment. Finally, as we elaborate below, the Developmental Model of the Closet also differs from theoretical models and empirical research on stigma concealment more generally (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010; Pachankis, 2007; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2013; Smart & Wegner, 2000). While sexual minorities in the closet conceal, they do so entirely, from all important others, often for a prolonged period, without the support of friends, family, and others for this identity. In this way, the closet is the ultimate manifestation of concealment for sexual minorities and consequently is argued to pose exacerbated versions of the challenges typically associated with concealment as well as several unique challenges.

Like the Disclosure Process Model (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010), the Developmental Model of the Closet assumes that the decision to come out is weighed against the perceived costs and benefits of doing so. The Developmental Model of the Closet further specifies that these costs and benefits are shaped by the surrounding heterosexist ideologies about sexual minorities embedded within cultures, families, schools, and neighborhoods, while also recognizing the sheer diversity of ideologies surrounding sexual minorities worldwide (e.g., Rahman & Valliani, 2016). Yet, unlike the Disclosure Process Model, the Developmental Model of the Closet does not address the myriad factors, other than surrounding cultural ideologies, that determine whether and after how long an individual might eventually come out. The Developmental Model of the Closet also allows for disclosure and coming out to occur at any point in the life course, and for identity fluidity (Diamond, 2016; Klein et al., 2015).

Finally, like the minority stress theory of sexual minority mental health (Meyer, 2003) and the related psychological mediation framework (Hatzenbuehler, 2009), the Developmental Model of the Closet also identifies stigma-related determinants of poor mental health and social functioning and potential psychosocial mechanisms through which stigma operates to affect these outcomes. However, by giving primacy to the closet, the Developmental Model of the Closet suggests that several of the psychosocial mechanisms outlined by minority stress theory and the psychological mediation framework can be understood through the developmental experience of the closet. For instance, the Developmental Model of the Closet suggests that social isolation emerges not only as a reaction to broadly stigmatizing environments (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009), but also from a lack of access to similar peers and role models encountered during the closet and the persistence of closet-related adaptations (e.g., feelings of inauthenticity, low perceived belonging, public-private compartmentalization) in post-closet life. Similarly, the Developmental Model of the Closet suggests the possibility that other minority stress mechanisms, such as rejection sensitivity (Pachankis et al., 2008) and contingent self-worth (Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013), might emerge not just as an adult response to contemporaneous stigmatizing environments (Pachankis et al., 2014), but might also represent an initially adaptive coping strategy learned during the developmentally sensitive period of the closet that can persist across the lifespan even when no longer adaptive.

The Developmental Model of the Closet: An Introduction

The Developmental Model of the Closet assumes that self-identified sexual minority individuals in most contemporary contexts will find themselves in the closet at some point in life – an assumption based upon two interrelated aspects of sexual orientation. First, in most current contexts, individuals are presumed to be heterosexual unless they present information suggesting otherwise through verbal or more tacit behavioral disclosure (e.g., showing romantic affection toward a same-sex partner (Davila et al., 2021; Villicana et al., 2016). Thus, one’s sexual minority status requires an intentional declaration or unintentional discovery to be truly known by others; in that way, sexual minority status is a concealable stigmatized identity (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009; Quinn, 2005; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2011; Quinn et al., 2014). Although sexual minority status can sometimes be inferred from gendered self-presentational cues (e.g., Freeman et al., 2010), such inferences are often inaccurate (Rule, 2017) and, in any event, can never be confirmed without disclosure or discovery of corroborating evidence. Second, sexual orientation is an emergent identity in that it manifests not from birth but later in the life course, often in adolescence (Calzo et al., 2011). The typical onset of sexual minority identity development may distinguish it from other concealable stigmatized identities (e.g., based on religion, ability, class) that arise earlier or later in life (Pachankis, Hatzenbuehler et al., 2018). Thus, except for sexual minorities raised in contexts, especially those non-Westernized contexts that hold less hetero-normative, gender-binary conceptualizations of sexual diversity (Herdt, 1997), or except for those who come to understand their sexual orientation while in the presence of another person (e.g., a passionate friendship; Diamond, 2002), these circumstances predispose sexual minority people to encounter the closet. Starting from this position, below we present a model that summarizes the lifespan developmental experiences that occur as a function of the closet (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

A developmental model of the closet

The Pre-Closet: Vicarious Socialization into Cultural Ideologies of Stigma

In most contexts throughout the world, sexual minorities are likely to encounter pervasive and negative public attitudes towards sexual minorities well before they come to identify as sexual minorities themselves (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2017). This occurs during what we refer to as the pre-closet, the developmental period during which one neither identifies themselves as having a sexual minority status, nor is out, but is nonetheless being socialized into the heterosexist cultural context surrounding sexual minorities. This period can be understood as being influenced by the highly variable structural stigma context surrounding sexual minorities across cultures worldwide and the ability of structural stigma to shape one’s internalized beliefs regarding sexual minorities. Ultimately, the Developmental Model of the Closet suggests that the experiences of this period determine how a sexual minority individual will respond to their emerging awareness of their sexual minority status during the closet period.

Structural stigma as developmental backdrop.

Structural stigma refers to the geographically bound societal conditions, such as laws, policies, and community attitudes, that undermine the welfare and life chances of a stigmatized population (Hatzenbuehler, 2016). Structural stigma surrounding sexual minorities predicts not only who is closeted, but also potentially exacerbates the stress of the closet. Recent research demonstrates that the odds of being closeted are strongly associated with structural stigma both at the country level (Layland et al., 2021; Pachankis & Bränström, 2018; Pachankis et al., 2021) and US state, county, and municipality level (Lattanner et al., 2021). For instance, sexual minorities in Russia are more than twice as likely to indicate that they have told no other person of their sexual minority status than sexual minorities in the Netherlands (Pachankis & Bränström, 2018).

A recent estimate suggests that, even when allowing for a wide margin of error, the majority of the world’s sexual minorities likely have disclosed their sexual minority status to no or very few people in their lives, largely a function of the strong censure of homosexuality in many countries around the world (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019). Same-sex relationships are criminalized in over 70 countries and punishable by death in eight of these (International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association, 2017). Even if one’s current structural context is supportive, early exposure to high structural stigma in the location where one was born or grew up continues to be associated with concealment of their sexual minority status in their current, more supportive environment for several years after relocating (Pachankis et al., 2021; van der Star, Bränström, & Pachankis, 2021).

Structural stigma might operate to perpetuate anti-LGBTQ bias in sexual minorities’ immediate, day-to-day contexts to ultimately shape their experience of the pre-closet. For instance, because structural stigma is closely related to attitudes toward sexual minorities (Ofusu et al, 2019), anti-LGBTQ attitudes of parents and other family members might serve as one vehicle through which structural stigma manifests in sexual minorities’ immediate contexts to shape their experience of the pre-closet. In fact, sexual minority youth whose parents respond more negatively to their sexual orientation come out later than those who respond more positively (Clark et al., 2021; D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2008; Huebner et al., 2019). Similarly, structural stigma in the broader community might shape the school climate toward sexual minority students, which in turn shapes the proximal ideologies surrounding sexual minorities in the pre-closet (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014). In fact, school bullying is especially common for sexual minority youth who are out in high-structural stigma countries (van der Star, Pachankis, & Bränström, 2021). Therefore, sexual minority youth in the pre-closet who live in high-structural stigma contexts are likely vicariously socialized to expect rejection or victimization upon disclosure. Consequently, the first testable hypothesis of the Developmental Model of the Closet is that youth in the pre-closet period (who will later identify as sexual minorities) who live in high-structural stigma contexts are vicariously socialized to expect rejection or victimization upon disclosure and therefore delay coming out (Hypothesis 1; Table 1).1

Table 1.

Testable hypotheses of the Developmental Model of the Closet.

| Testable Hypotheses of the Pre-closet Period |

| Hypothesis 1. Youth in the pre-closet period (who will later identify as sexual minorities) who live in high-structural stigma contexts are vicariously socialized to expect rejection or victimization upon disclosure and therefore delay coming out. |

| Hypothesis 2. Given the pervasive influence of structural stigma, individuals who will later identify as sexual minorities are likely to internalize its negative messages and ascribe any early sense of difference to the content of these messages during the pre-closet period. |

| Hypothesis 3. The mental health and social functioning of individuals in the pre-closet period (before coming out) is a function of the structural stigma of their surroundings. For sexual minorities who report an early feeling of difference, perhaps especially likely for those who exhibit gender non-conforming behaviors and interests, the adverse influence of structural stigma is particularly strong. |

| Hypothesis 4. Pre-closet experiences of structural stigma, personal differences perceived as negative, and their interaction strongly determine if, when, and how one comes out. |

| Testable Hypotheses of the Closet Period |

| Hypothesis 5. The stress of the closet is exacerbated for sexual minorities who arrive at the closet during adolescence (as opposed to later in life), given the stressful developmental challenges of this developmental period. |

| Hypothesis 6. The psychological costs of secrecy documented in existing research are likely to be exacerbated in the closet given the absolute secrecy (i.e., no disclosure at any time to anyone) that the closet entails. |

| Hypothesis 7. Because the closet keeps sexual minorities hidden from each other, sexual minorities in the closet face barriers to accessing sexual minority role models, who can facilitate decisions of whether to come out and the navigation of closet-related and post-closet challenges. |

| Hypothesis 8. Experiences of victimization and vicarious victimization may be especially harmful to sexual minorities during the closet period due to their self-awareness of their sexual minority status and relative lack of outlets through which they can process negative identity-related experiences and solicit more affirming information. |

| Testable Hypotheses of the Post-closet Period |

| Hypothesis 9. The negative adaptations of the closet might continue to pose mental health challenges even upon coming out, especially when one’s closet-related challenges were especially severe and especially under negative post-closet environmental conditions (e.g., high structural stigma, pervasive negative reactions from others). |

| Hypothesis 10. Supportive post-closet conditions (e.g., low structural stigma, positive reactions upon disclosure) allow closet-related adaptations to transform into sources of growth rather than persistent drains on mental health. |

| Testable Hypotheses of Moderators of the Model |

| Hypothesis 11. One’s endorsement and centrality of a sexual minority identity during each of the model’s periods shapes an individual’s experiences of stressors and resiliencies during that period. |

| Testable Hypotheses of Interventions for the Model’s Components |

| Hypothesis 12. Structural improvements improve mental health through reducing the adaptations required by the closet and its duration. |

| Hypothesis 13. Affirming school, family, community, and individual interventions buffer against structural stigma to reduce pre-closet internalization of negative cultural ideologies and closet-related stressors and adaptations and support post-closet growth. |

Early internalization of sexual minority stigma.

Because the structural context surrounding sexual minorities exerts a strong impact on remaining closeted, it can be assumed that it does so through teaching sexual minorities powerful lessons about what it means to be a sexual minority or to exist outside of dominant heterosexist norms. We hypothesize that this process begins even before sexual minorities possess an awareness that they themselves might be a sexual minority. In fact, stereotypes are often learned by age five (e.g., Ambady et al., 2001; Dunham et al., 2008), are resistant to change (e.g., Haines et al., 2016), and become self-directed upon the emergence of one’s own stigmatized identity (Cox et al., 2012). In this way, our conceptualization of the pre-closet is similar to research on other stigmatized statuses, in particular mental illness (Link et al., 1989). Similar to a sexual minority status, mental illness emerges later in life—often in adolescence and young adulthood—well after the individual has internalized negative societal ideologies about that status. Research on modified labeling theory as originally applied to mental illness finds that, as a function of pervasive stigmatizing ideologies, individuals internalize negative attitudes toward stigmatized groups and that, when they themselves become aware of their own membership in such a group, this internalization drives concealment of the stigma and social withdrawal (Kroska & Harkness, 2006; Link et al., 1989). Modified labeling theory has been applied to other stigmatized statuses, like obesity (e.g., Hunger & Tomiyama, 2014), with research finding that the harms of early socialization and ultimate labeling and internalization persist into adulthood. Our model proposes that such a process also occurs for sexual minorities. Indeed, structural stigma toward sexual minorities manifests in publicly visible ways, from negative interpersonal treatment of sexual minorities, including victimization and discrimination (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019; van der Star, Pachankis, & Bränström, 2021), to negative mainstream media depictions of sexual minorities as illegitimate (Flores, Hatzenbuehler, & Gates, 2018). Not surprisingly, therefore, structural stigma is strongly correlated with perceived normative bias against the stigmatized in the general population (Tankard & Paluck, 2017) and internalized bias among sexual minorities themselves (Pachankis et al., 2021). Modified labeling theory suggests that this internalization happens among all or most members of society, who, in the absence of readily available forums for critical examination of cultural messages about the stigmatized, cannot help but absorb these messages. For those members of society for whom a sexual minority status and its associated stigma will ultimately apply, research with other stigmatized populations suggests that this awareness—born of structural stigma—comes at a steep and persistent cost to mental health and social functioning (Link et al., 1989; Hunger & Tomiyama, 2014).

Early sense of difference.

Despite not yet having adopted a sexual minority identity, young people in the pre-closet period who later identify as sexual minorities might nonetheless be particularly likely to attend to sexual minority stigma in their structural surroundings and to internalize its self-relevance. In particular, those who later identify as sexual minorities often report feeling different from others from a young age (Newman & Muzzonigro 1993; Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2015; Taylor, 2000). In childhood, this difference often manifests as gender nonconforming behavior or interests; in adolescence and young adulthood, as same-sex romantic or sexual attractions (Cohen, 2002) or passionate friendships (Diamond, 2002). Parents and peers often notice and react to this difference (D’Augelli et al., 2008; Toomey et al., 2013; Toomey et al., 2014). In fact, sexual minority youth are more likely to experience peer teasing and bullying in childhood and early adolescence (Mittleman, 2019), even before many or most have self-identified as a sexual minority (Pachankis, Clark, Klein, et al., 2020). In fact, children whose parents believe that their child is a sexual minority are at particularly high risk of psychiatric morbidity especially if the child themselves does not identify as a sexual minority, perhaps a pre-closet indicator (Clark et al., 2020).

Those in the pre-closet might come to understand the structural backdrop surrounding sexual minorities through an emerging personal difference, which might further heighten its internalization. Because the structural backdrop is often negative, one’s gendered behavior or interests or emerging same-sex attractions or relationships might themselves become readily self-interpreted as negative to the extent these differences are at least remotely understood as relevant to biased cultural discourse about sexual minorities. Accordingly, the mental health harms that the model most strongly associates with the closet in the next section (e.g., belonginess threats, isolation from similar peers, victimization) might begin emerging during the pre-closet, and this may be especial true among sexual minorities who express gender nonconforming traits during this period.

Consequently, the second testable hypothesis of the Developmental Model of the Closet is that individuals who will later identify as sexual minorities are likely to internalize the negative messages of structural stigma and ascribe any early sense of difference to the content of these messages (Hypothesis 2; Table 1). Relatedly, the model hypothesizes that for individuals in the pre-closet period who report an early feeling of difference during this period, perhaps especially for those who exhibit gender non-conforming behaviors and interests, the adverse influence of structural stigma on mental health and social functioning is particularly strong (Hypothesis 3; Table 1). These pre-closet experiences therefore strongly determine if, when, and how one comes out (Baum & Critcher, 2020; Camacho et al., 2020; Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010) (Hypothesis 4; Table 1).

The Closet: Heightened Social Stress Requiring Psychological Adaptation

The model proposed here suggests that what many sexual minorities report as a diffuse and elusive feeling of being different from their peers (Newman & Muzzonigro 1993; Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2015; Taylor, 2000), often during adolescence, becomes a clear and attributable difference based on their emergent sexual minority status—and thus, they arrive within the closet. The closet might be particularly stressful because of its typical onset during a sensitive developmental period for the emergence of depression and anxiety, in relative isolation from similar peers and supportive role models, and because despite its intrapersonal costs, it does not likewise guarantee protection against the interpersonal costs of rejection and victimization. As reviewed above, sexual minorities who live within particularly stigmatizing structural contexts are likely to internalize heterosexist cultural ideologies, magnifying these stressors.

Belongingness threats during a sensitive developmental stage.

Most sexual minorities become aware of their same-sex attractions and sexual identity at the start of adolescence and do not disclose their minority status to another person for the duration of adolescence, even in supportive social climates (Calzo et al., 2011; Katz-Wise et al., 2017; Layland et al., 2021; Rosario et al., 2004). From a developmental psychopathology perspective, this timing is unfortunate (Friedman et al., 2008; Katz-Wise et al., 2017). Specifically, adolescence is a period of development during which understanding the self and identity are especially salient, and the need to conceive of a stable sense of self becomes paramount to developing a sense of control in everyday life (Erikson, 1959; Frijns & Finkenauer, 2009; McAdams, 1993). The need to belong, especially powerful during adolescence, shapes identity formation and motivates the drive to conform to or resist hegemonic narratives (McLean, Shucard, & Syed, 2017).

Given the central role of belonging during adolescence, this developmental period is characterized by increased peer-directed social activities, particular importance of peer group status, and high susceptibility to the negative mental health consequences of social stress, including targeted rejection (Charmandari et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2013; Romeo et al., 2006). Social stress during this time can become particularly self-defining and emotionally salient (Rubin et al., 1998; Singer & Salovey, 1993). For instance, thwarted or contingent belonging can disrupt intrinsic goals and motivation (e.g., Sheldon & Kasser, 2008). Further, social stress during this time can also alter neurobiology to impact later risk for depression and anxiety (e.g., Andersen & Teicher, 2008; Leussis & Andersen, 2008; Murphy et al., 2013). Therefore, during the very developmental stage that most individuals are particularly reliant on belonging for a stable sense of self and highly sensitive to social stress (Charmandari et al., 2003), the average sexual minority adolescent is typically becoming aware of their stigmatized social status. This is often accompanied by expectations of and actual rejection, potential loss of belonging, and the challenge of forming a minority sexual identity against a default narrative of heterosexuality (Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2015). By virtue of the closet, this awareness and stress is happening in isolation without identity-affirming support that can be internalized as reflecting one’s true self – sexual minority identity and all. Thus, the Developmental Model of the Closet hypothesizes that the stress of the closet is exacerbated for sexual minorities who arrive at the closet during adolescence (as opposed to later in life) (Hypothesis 5; Table 1).

The psychological toll of secrecy.

Maintaining one’s position within the sexual minority closet necessitates guarding a secret and is therefore stressful (Pachankis, 2007; Smart & Wegner, 2000). Theory and research on secret-keeping, including about stigmatizing information, suggests that secrecy yields feelings of inauthenticity (McDonald et al., 2020; Newheiser & Barreto, 2014; Slepian et al., 2017), diminished sense of belonging (Newheiser & Barreto, 2014), hypervigilance and monitoring (Bouman, 2003; Critcher & Ferguson, 2014; Frable et al., 1990; Santuzzi & Ruscher, 2002; Smart & Wegner, 1999), cognitive preoccupation and rumination (Maas et al., 2012; Slepian, Greenaway, & Masicampo, 2020), strong compartmentalization between public and private selves (Sedlovskaya et al., 2013), and shame (Fishbein & Laird, 1979; Slepian et al., 2020), each with negative implications for mental health and social functioning. Further, whereas confiding in others about personally relevant experiences fosters relationship satisfaction, identity development, meaning-making, trauma resolution, and even wisdom and health (Elsharnouby & Dost-Gözkan, 2020; McAdams, 2001; Mansfield et al., 2010; Pasupathi et al., 2009; Pennebaker, 1989, 1995; Sprecher & Hendrick, 2004), secrecy prohibits these processes. In sum, substantial research on secrecy on the one hand and disclosure on the other strongly suggests that the closet can usher in substantial mental health costs by virtue of secrecy alone.

Here again, the harmful effects of secrecy may also be especially detrimental during adolescence, the developmental period during which individuals are most likely to be in the closet. Research suggests that harboring secrets in adolescence has longer-term downstream consequences for mental health (Frijns et al., 2005, 2013; Frijns & Finkenauer, 2009, Laird & Marrero, 2010). Although some benefits of secrecy during adolescence exist (e.g., emotional autonomy), such benefits may be most attributable to keeping secrets from parents during a period in which adolescents begin to increasingly rely on friends for emotional support (Finkenauer et al., 2002). Unlike individuals who have begun coming out, those in the closet do not have such peer confidants. One can easily imagine how the total secrecy that characterizes the closet keeps sexual minorities from processing events related to their sexual minority status (e.g., witnessing an unknowing crush pursue another romantic partner), including traumatic events (e.g., same-sex sexual assault), with adverse mental health consequences.

While most of the above research concerns secrecy in general, or concealable stigmatized identities more broadly, one psychological cost of secrecy has been directly examined as a function the sexual minority closet. Specifically, supporting the possibility that the closet poses psychological demands as a function of strategic adaptation, sexual minority male university students in one study were more likely to invest their self-worth in achievement-related domains (e.g., academic and competitive success) than heterosexual college students. Further, the length of time that sexual minority students were in the closet during adolescence significantly predicted the degree to which they invested their self-worth in these particular domains (Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013). As long as one hides an important part of their identities, such as their sexual orientation, acceptance of their full selves can never be guaranteed (Jourard, 1971). Therefore, some sexual minorities in the closet might invest their self-worth in domains that do not rely on others’ approval, but instead only on how hard they can work, such as through academic, financial, or other competitive success. Strategically investing one’s self-worth in domains in which one is likely to succeed and disengaging one’s self-worth from domains in which one is likely to fail might be one way to protect self-worth against social or structural threats (Crocker et al., 2003; Crocker & Wolfe, 2001). Yet, for sexual minorities this comes at a mental health cost, including social isolation, negative affect, and dishonesty as shown in a 9-day daily diary study (Pachankis & Hatzenbuehler, 2013).

Except for research on contingent self-worth as a function of the closet, the research on secrecy applies to individuals with a concealable stigmatized identity who are at least partially out about their identity or to individuals who were experimentally induced to recall or hide personal secrets in a laboratory setting. We propose that this research nonetheless has relevance to the experience of the sexual minority closet. We specifically hypothesize that the psychological costs of secrecy are likely to be exacerbated in the closet given the absolute secrecy that the closet demands (Hypothesis 6; Table 1). Indeed, secrets kept completely private are understood to weigh heaviest on the secret keeper, causing greater psychological harm than those shared with confidants (Frijns et al., 2013). Future research is needed to examine the impact on mental health and social functioning of the other psychological costs of secrecy, besides contingent self-worth, as specifically related to the sexual minority closet.

Lack of access to similarly identified peers and sexual minority role models.

Unlike many other prominent stigmatized identities that one’s family, community, and many peers also often share (e.g., like a racial/ethnic or religious minority status in the US), minority sexual orientations are randomly and diffusely distributed in the population. Current estimates suggest that about four percent of US adults identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB), with a slight majority of this population identifying as bisexual (Gates, 2011); the proportion of younger birth cohorts of US adults that identifies as LGB is slightly larger (Gates, 2017) and including emerging sexual minority identity categories (e.g., pansexual) might increase the number of sexual minorities somewhat further (Watson et al., 2020). Therefore, the average sexual minority person in the closet encounters a small prevalence of sexual minority others in their daily lives, such as at school. In an average classroom of 30 students, only one, maybe two, students will be sexual minorities. This numeric infrequency would pose challenges to identifying similar peers even without the reality of the closet, which further keeps similar peers out of visibility from each other (Beals, Peplau, & Gable, 2009; Frable et al., 1998; Taylor, 2000).

Given that the closet keeps sexual minorities relatively hidden from each other, combined with the random and diffuse distribution of minority sexual orientations in the population, closeted sexual minorities are at risk of lacking visible and accessible sexual minority role models. While population-based research has not compared the prevalence of available role models across sexual orientations, research using non-probability samples finds that a sizeable proportion of sexual minority adolescents reports not having a role model and that most identified role models are inaccessible (e.g., television stars, pop stars). Indeed, less than 20% of a diverse sample of sexual minority youth reported having an accessible role model, such as a parent or teacher (Bird et al., 2011). While this study did not assess the sexual orientation of role models, because the closet keeps sexual minorities out of reach of each other, especially inter-generationally (Bohan et al., 2002), likely few sexual minority adolescents have access to a sexual minority role model. A lack of accessible role models is associated with mental distress across studies of sexual minority adolescents (Bird et al., 2011; Grossman & D’Augelli, 2004) and may be another way that the closet harms mental health.

Role models might be particularly important for sexual minorities, and especially for sexual minorities in the closet who would benefit from examples of out sexual minority life. Compared to heterosexuals, the average sexual minority individual follows different scripts, encounters different contexts, and faces different opportunities and challenges, some of which are not necessarily related to stigma, but which can nonetheless affect mental health (Cochran, 2001). For instance, sexual minorities are less likely to have children (Gates, 2013), more likely to live alone (Wells et al., 2011), more likely to be non-monogamous (Haupert et al., 2017), and more motivated to move cities to seek opportunities around similar others (Human Rights Campaign, 2010) than are heterosexuals. Sexual minorities may also encounter unique relationship challenges and questions (e.g., comparing oneself to one’s partner, dating within friend circles, unique manifestations of domestic violence, whether to date someone who is closeted, sexual position negotiations) and have distinct sexual health needs (Keuroghlian et al., 2017; Meadows, 2018) that might be best and most easily answered by similar others.

Given these distinct life paths facing sexual minorities, sexual minorities would likely benefit from guidance and support for navigating these decisions. However, the closet poses challenges to identifying, connecting with, and therefore learning from out sexual minorities (Suppes et al., 2021). For instance, while in the closet, a sexual minority person cannot easily make themselves known or visible to those who might serve as mentors and guides. This cost of the closet to role modeling is perhaps compounded by barriers to intergenerational contact across sexual minorities, including highly distinct and rapidly changing experiences across successive cohorts of sexual minorities (Hammack et al., 2017; Rosenfeld et al., 2012; Russell & Bohan, 2005) and stereotypes of older sexual minority individuals as predators (Hajek, 2018). The closet can also keep role models themselves hidden. For instance, in high-stigma contexts where concealment is high across age groups, visible, thriving sexual minority role models might be particularly likely to be out of sight of younger cohorts (Pachankis & Bränström, 2019).

At the same time that the Developmental Model of the Closet suggests that the closet serves to keep sexual minority individuals away from each other and from supportive role models, this barrier of the closet might not be absolute. Indeed, emerging evidence suggests that academic and extracurricular involvement is at least partially patterned by sexual orientation. For instance, although sexual minority youth are less likely to participate in sports than heterosexual youth (Greenspan et al., 2017), likely due to disproportionate threats and fears of safety due to gender non-conformity (Kulick et al., 2019), they are also more likely than heterosexual youth to participate in other extracurricular activities such as theater (Perrotti & Westheimer, 2002). Increasingly, evidence also suggests that sexual minority boys are more likely to engage in academic pursuits than heterosexual boys, although this particular difference does not seem to exist for girls (Mittleman, in press). Together, this research suggests that perhaps even while in the closet, sexual minority young people might affiliate with like-minded others – perhaps through both choice and duress – which can serve to provide support and even role modeling during the closet period. Yet, as mentioned above, as long as this contact happens in the closet, the validation stemming from affiliation and support likely cannot be completely internalized as long as one has not shared the full identity for which this support is needed. Such affiliation and support while in the closet also likely cannot explicitly and directly solve an individuals’ specific identity-related questions or challenges since these remain unspoken, even if assumed. In addition to being incomplete, support received from others who are unaware of one’s sexual orientation might also be invalidating if those others share heterosexist or otherwise stigmatizing attitudes. Combined with the lack of means for directly challenging this stigma, receiving such stigma in the closet without support from similarly stigmatized others might be particularly detrimental to mental health and social functioning.

In sum, at the same time that sexual minorities face distinct developmental challenges, the closet poses several barriers to seeking support for navigating those challenges. The Developmental Model of the Closet hypothesizes that because the closet at least partially keeps sexual minorities hidden from each other, sexual minorities in the closet face barriers to accessing sexual minority role models, who can facilitate decision of whether to come out and the navigation of closet-related and post-closet challenges (Hypothesis 7; Table 1).

Victimization despite concealment.

In addition to becoming aware of their socially devalued status in relative isolation, sexual minority adolescents report substantially more victimization, discrimination, and peer rejection than heterosexual adolescents (Almeida et al., 2009; Bos et al., 2008; Friedman et al., 2011). Importantly, one can be in the closet and still be harmed by homophobic prejudice. First, there is a potential for targeted rejection, especially toward gender nonconforming behavior, even without sexual orientation disclosure (Gordon et al., 2018; Rieger et al., 2008; Roberts et al., 2013; Toomey et al., 2013; Toomey et al., 2014). Thus, for many sexual minorities, especially those who are gender nonconforming, the costs of the closet (e.g., lack of contact with similar others) are not necessarily offset by protection against victimization. Perhaps given these greater costs than benefits (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010), sexual minorities who exhibit gender nonconforming behaviors and interests might come out earlier, especially given that they conceal less frequently than those who are gender conforming (Thoma et al., 2021). Second, experimental research shows that concealing a sexual minority identity does not necessarily guarantee being treated more favorably by heterosexuals (Goh et al., 2019), and turning down opportunities to disclose personal information can paradoxically invite more negative treatment than revealing this information, even when the information is perceived as negative (John et al., 2016). Finally, even those who are protected from direct homophobic victimization may nonetheless feel the vicarious sting of witnessing homophobia directed elsewhere. Being in the closet does not, for example, protect one from seeing a stereotypical portrayal of sexual minority people in the media, witnessing the homophobic bullying of a peer, learning inaccurate information about the history, contributions, and morality of sexual minorities, or learning about an LGBTQ hate crime (Balsam et al., 2013; Bell & Perry, 2015; Willis, 2012). The Developmental Model of the Closet hypothesizes that experiences of victimization and vicarious victimization may be especially harmful to sexual minorities during the closet period due to their self-awareness of their sexual minority status and relative lack of outlets through which they can process negative identity-related experiences and solicit more affirming, accurate information (Hypothesis 8; Table 1).

Indistinct zones of the closet.

Using our proposed definition of the closet—the period between sexual minority self-labeling and one’s first sexual minority disclosure—most sexual minorities, at any given moment of their lives, are likely to be easily definable as either in the closet or outside of it (e.g., within the pre- or post-closet period). However, certain unique experiences of sexual minority identity development and disclosure challenge these seemingly distinct boundaries. For instance, individuals who ultimately identify as sexual minorities may, at one point, question whether they are heterosexual without yet self-identifying with a sexual minority identity label; others might engage in same-sex sexual behavior but temporarily self-identify as heterosexual. Such individuals exemplify the indistinct zone between the pre-closet and closet periods. Similarly, one can imagine scenarios that demonstrate the gray area between the closet and post-closet periods. Consider sexual minorities who only ever disclose their sexual minority status to an anonymous, insignificant, or no longer available other. Additionally, an individual might disclose their sexual minority status only to later renounce the disclosure and identify as heterosexual, effectively returning to the closet. Such individuals blur the distinctness and sequential nature of the closet and post-closet. In recognition of these trajectories and others, our model acknowledges the potential for individuals to find themselves within indistinct zones of the closet—whether fleetingly or across long stretches of the lifespan (see Figure 1).

The Post-Closet: Contextual Moderators of Lifespan-Persistent Negative Adaptations to the Closet Versus Post-Closet Growth

Although concealment demands might be ongoing and although sexual identities might remain in flux, the Developmental Model of the Closet highlights the distinct moment when one discloses their sexual minority status to one or more important others in their lives – at the point, the closet technically ends. What happens next, according to the Developmental Model of the Closet, depends on the conditions that one comes into when coming out. One possibility is that by coming out, one can potentially be known as their fuller self – stigma and all – thereby reducing the psychological toll of secrecy, increasing the likelihood that they will have meaningful contact with similar others, and ushering in a period of post-closet flourishing. At the same time, the sexual orientation disparities in several mental health problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) persist across the lifespan (Rice et al., 2019) and might at least partly be explained by the persistence of closet-related coping into post-closet life.

On the one hand, the possibility of post-closet growth is supported by over 100 studies, which on average show a small negative association between disclosure and depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (Pachankis, Mahon et al., 2020). This meta-analytic finding suggests that disclosure might yield a net positive benefit to mental health and that the benefits of coming out might outweigh the known challenges of navigating a new public stigmatized identity, including victimization and discrimination (Pachankis & Bränström, 2018; Suppes et al., 2021). In fact, research shows that despite the challenges of coming out, several benefits accrue, including increased feelings of belonging, a reduced toll of secrecy, and greater integration into sexual minority communities (e.g., Suppes et al., 2021).

At the same time, the disproportionate risk of mental health problems facing sexual minorities does not completely dissipate over the lifespan (Rice et al., 2019), suggesting that psychological burdens of the closet might remain for some. Thus, the Developmental Model of the Closet proposes that the psychological adaptations learned in closet – achievement-contingent self-worth, hypervigilance, cognitive preoccupation, compartmentalization – might persist under negative post-closet disclosure conditions, in which these adaptations might remain necessary for protecting mental health and safety.

According to the Developmental Model of the Closet, whether the stressful adaptations of the closet continue into the post-closet period or whether the post-closet period brings about a period of growth away from these adaptations depends on three factors surrounding the sexual minority person’s disclosure. These factors include the structural (i.e., structural stigma environment), interpersonal (i.e., others’ reactions to the person’s disclosure), cultural (i.e., related to other features of identity, such as race, ethnicity, and religion), and temporal (i.e., changing sociocultural conditions) context of disclosure.

Structural stigma.

As for structural conditions of the post-closet disclosure environment, research shows that sexual minority adults who are out in structurally stigmatizing environments experience lower life satisfaction than those in more supportive environments, as a function of greater exposure to discrimination and victimization compared to those who are not out and those who live in structurally supportive environments (Bränström & Pachankis, 2018). Therefore, for those living in structurally stigmatizing environments, those same structural stigma conditions that set into motion the stressors and adaptations of the pre-closet and closet periods might continue to exact their toll on sexual minority mental health and social functioning by constraining post-closet opportunities for growth past the stressful adaptations of the closet. Importantly, structural stigma can occur at multiple socioecological levels, from the distal (e.g., country-level laws and policies) to the more proximal (e.g., school, workplace, or religious organization policies). Structural stigma regardless of its socioecological level is associated with adverse mental health among sexual minority youth and adults (e.g., Meyer et al., 2019; Poteat et al., 2013). Recent research also shows that concealment pressures imposed by structural stigma at one level are conditional on structural stigma at another level, such that concealment pressures are lowest, for example, when structural stigma is low across levels, and that perhaps low levels of structural stigma at a proximal level (e.g., a supportive city) can offset some of the concealment pressures of structural stigma at a distal level (e.g., an unsupportive state) (Lattanner et al., 2021). Although structural stigma can occur at multiple socioecological levels surrounding an individual, overall, this research suggests that the costs to concealment pressures and mental health increase as the number of socioecological levels that can be characterized as stigmatizing increases.

Others’ reactions.

Negative reactions from others upon disclosure and the type of relationship in which this occurs represent another relevant post-closet disclosure condition capable of moderating the post-closet experience. Indeed, research shows that negative reactions from others, including from parents, is associated with mental health and substance use problems (e.g., Rosario, Corliss et al., 2014; Rosario, Schrimshaw et al., 2009), lending support to the possibility that an unsupportive post-closet environment can lead to the persistence of negative adaptations learned in the closet. The type of relationship in which one discloses is also likely important. For instance, peer reactions might be particularly impactful, especially during adolescence, given the relative importance of peer influence across early development (e.g., Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Peer exclusion upon disclosure can constrain peer networks and the potential for post-closet growth (e.g., Poteat et al., 2009; Prinstein & La Greca, 2004; Dishion et al., 1995). These findings join the large body of research documenting disproportionate rates of negative parental and peer interpersonal treatment, including discrimination, bullying, and other forms of victimization, towards sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals (Friedman et al., 2011), that at least partially explain sexual minorities’ greater risk of adverse mental health and social functioning (Pachankis et al., 2021). However, this research does not typically focus on discrimination and victimization as an outcome of disclosure per se and some mistreatment might be directed toward gender non-conforming individuals who are presumed to be sexual minority regardless of their actual sexual orientation or outness (Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2012; Poteat & Russell, 2013).

Cultural context.

The Developmental Model of the Closet also positions culture as an important feature of the post-closet disclosure environment that shapes post-closet experiences. Culture shapes the nature and meaning of a sexual minority identity itself and therefore others’ reactions to disclosure. For instance, disclosure of a sexual minority identity in a collectivistic culture might exact particularly steep costs, at least to the extent that one’s community or family are likely to perceive one’s sexual minority identity as a form of communal disrespect (Cerezo et al., 2020; Hu & Wang, 2013; Sun et al., 2020; Villicana et al., 2016). This would be expected to heighten the persistence of closet-related adaptations. Against other cultural backdrops, sexual identity concealment might be desired (Schrimshaw et al. 2018) or privileged (Massad, 2002) compared to being out, which could also strengthen the persistence of closet-related adaptations for those who are out. In cultures in which open identification as a sexual minority is particularly costly, one might instead choose to preserve other meaningful cultural identities and communal ties, even if this requires relative disengagement from one’s sexual identity (Bowleg et al., 2008). The exclusion of people of color from gay-related organizations and media depictions (e.g., Millet et al., 2006) might constrain options for sexual self-identification (Pathela et al., 2006) in ways that might prolong the adaptations of the closet into post-closet life (Santos & VanDaalen, 2016).

Temporal context.

The Developmental Model of the Closet is derived from research concerning the ways current social conditions (e.g., laws, societal attitudes, LGBTQ visibility) shape sexual minorities’ internal and environmental experiences. However, not only are social conditions for sexual minorities inconsistent across geography and cultural context as discussed previously, but such factors are also not static over time. In fact, within many contexts, the legal rights and public support for sexual minorities are rapidly changing and show little sign of slowing down (Earnshaw et al., 2022; Russell & Fish, 2019). Therefore, the tenets of the Developmental Model of the Closet are likely moderated by the temporally distinct context in which sexual minorities live. Most obviously, the predictions of the present model are only applicable in future contexts within which sexual minorities remain a distinct and structurally stigmatized social group. Also, specific societal advances may serve as facilitators and barriers to coming out or otherwise attenuate certain predictions of the model. For example, changes in LGBTQ media representations and general technological advances are likely to render individuals less dependent upon their immediate surroundings to experience identity-related affirmation. For example, compared to previous generations, current US adolescents are more likely to encounter positive representations of LGBTQ individuals within the news, social, media, and TV (Craig & McInroy, 2014; Russell & Fish, 2019). If such representations become increasingly common and more uniformly positive, they may more effectively compensate for the negative messages of sexual minority stigma suggested to be a defining feature of the pre-closet stage. Relatedly, one tenet of the Developmental Model of the Closet is that the closet is harmful, in part, because it limits individuals’ access to identity-affirming information and similar others. However, the global proliferation of broadband internet (Baller et al., 2016) has provided many sexual minority individuals with a previously unavailable means to privately (a) access accurate and affirming information about LGBTQ life, (b) encounter a diverse array of LGBTQ role models online, and (c) connect with virtual LGBTQ communities to cope with stigma and foster a positive sexual minority identity (Craig & McInroy, 2014; Jackson, 2017). Such outlets may increasingly empower sexual minority individuals within the closet who historically may have been dependent upon coming out to access information and people demonstrating the existence, history, worth, and diversity of the LGBTQ community. Overall, future researcher of the closet must consider, at the time of study, which of the model’s constructs and conceptualizations reflect the lived experiences of sexual minority populations—qualifying those that are waning and discarding those that no longer apply (Hammack et al., 2021).

Post-closet growth.

Just as negative post-closet disclosure conditions can encourage the persistence of closet-related adaptations into post-closet life, the Developmental Model of the Closet proposes that under positive disclosure conditions, the post-closet period can represent a marked departure from the closet stage and usher in a period of growth even if some of the closet-related adaptations persist in some form. In addition to generally supportive structural conditions, positive post-closet disclosure conditions might include family and non-school peer supports, which can yield positive post-closet experiences even in the presence of school-based rejection upon disclosure, given the relative importance and pervasiveness of these relationships (e.g., East & Rook, 1992). Further, integrating one’s sexual identity into other marginalized aspects of identity can serve as an identity-affirming buffer against the stress of open identification in post-closet life (Cerezo et al., 2020; Rahman & Valliani, 2016; Sarno et al., 2015), which can perhaps set one on a path of post-closet growth.

Research suggests that post-closet growth might allow the learned adaptations of the closet to actually flourish under supportive post-closet conditions. In fact, the flip side of many of the negative closet adaptations reviewed above are in fact positively adaptive. For instance, the social sensitivity inherent to hypervigilance can serve as the source of interpersonal attunement – a valued trait (e.g., DeWall et al., 2009; Maner et al., 2007) – whereas belongingness threats and social isolation can foster adaptive independence, another positive adaptation. Interestingly, social sensitivity and independence are the very traits that characterize the occupations in which sexual minorities are over-represented in national studies (e.g., psychologists, a profession rated as requiring social sensitivity; mechanics, a profession rated as requiring high independence; Tilcsik et al., 2015), even after accounting for gender typicality of various occupations. Even beyond the workplace, social sensitivity and independence might represent highly adaptive traits in close relationships, creative pursuits, spirituality, and social activism. Research and theory on “altruism born of suffering” suggests that the pursuit of empathy, social integration, and meaning-making motivate prosocial outcomes among unduly stressed populations (Staub & Vollhardt, 2008; Vollhardt, 2009). These motivations are also consistent with the individual (e.g., authenticity) and collective (e.g., improved relationships) aspects of closet-related growth identified in a community sample of gay and lesbian adults (Vaughan & Rodriguez, 2014; Vaughan & Waehler, 2010) and merit further research as possible sources of adaptive post-closet manifestations of the coping strategies learned in the closet (e.g., hypervigilance). Rather than being a burden on mental health, such coping strategies, when allowed to flourish under supportive post-closet conditions, could instead be characterized as resilient life assets.

Persistence of closet-related learning versus post-closet growth.

We propose that the degree of influence that the post-closet disclosure environment has on how likely stressful closet-related adaptations might be to persist versus how strongly post-closet growth occurs depends on the nature and degree of exposure to that environment. Here we borrow from learning theory (e.g., Bouton, 1993; Bouton et al., 2001) and the notion of corrective emotional experiences (Miller et al., 1947) to posit that the post-closet period is a time of new learning not possible in the closet and that the strength of this new learning depends on the pervasiveness of exposure to post-closet disclosure environments and their emotional context. For instance, one critical feature of the post-closet disclosure environment is the person or people to whom one discloses. Disclosing to a close friend, parent, teacher, or spouse, for instance, will likely provide a more powerful learning experience than disclosing to an anonymous sex partner, anonymous online contacts, or an online research survey. One reason for the greater power of the former type of disclosure context is that these relationships are more pervasive, allowing numerous opportunities for experiencing oneself as an out person on a repeated basis in the presence of the other. They are also more powerful because they are emotionally important – a close friend, parent, teacher, or spouse is a relationship often built over a substantial duration of time and how that person reacts has substantial potential to confirm or override adaptations learned in the closet. In learning theory terms, these relationships provide more trials for new learning and more emotionally salient contexts. A positive disclosure response from a meaningful person in one’s life can provide a corrective emotional experience, fostering post-closet growth; a negative disclosure response is likely to encourage the persistence of learned closet-related adaptations, including hypervigilance, preoccupation, compartmentalization, and contingent self-worth. Receiving a positive disclosure response from important others is also likely to encourage future disclosure and the accumulation of new learning. Conversely, receiving a negative disclosure response from important others is likely to reduce future disclosures (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010). The likelihood of persistence in, versus growth away from, closet-related adaptations is argued to be a function of the net positive versus negative reactions from others in combination with the importance of those relationships. Even though a first disclosure is a singular, one-time event that ushers in the end of the closet period, lessons learned from this event about one’s newly out self can lead to proliferating future disclosures or dampen the likelihood of subsequent disclosures. The total impact of this initial disclosure on post-closet stress versus growth therefore rests not only on this initial disclosure but also on its potential to generate or prevent future disclosures that are characterized by their own emotional valences and impacts.

Overall, the Developmental Model of the Closet suggests two hypotheses regarding the post-closet period. The first hypothesis is that the negative adaptations of the closet continue to pose mental health challenges even upon coming out, especially under negative post-closet environmental conditions (Hypothesis 9; Table 1). The second is that supportive post-closet conditions, including structural, interpersonal, and cultural, allow closet-related adaptations to transform into sources of flourishing rather than persistent drains on mental health (Hypothesis 10; Table 1).

Personal Moderators of the Closet: Sexual Identity Fluidity and Centrality

Rather than proposing that the closet represents a singular experience that similarly characterizes all sexual minorities, the Developmental Model of the Closet recognizes that the experience of the closet is likely moderated by personal features, including sexual identity fluidity and centrality. These personal moderators apply to all periods of the model and complement the structural, interpersonal, cultural, and temporal moderators of the post-closet experience reviewed above.

Sexual minority identities are diverse, both in terms of their relative fluidity over time (Diamond, 2016) and their centrality to the individual (Dyar et al., 2015). Even among individuals who experience high sexual identity fluidity or low sexual identity centrality over time, for most people who come to identify as sexual minorities, there is at least one period in which they—and only they—know of their sexual minority status. That said, like any conceptual model based on identity awareness and disclosure, the Developmental Model of the Closet proposed here is likely moderated by this diversity of identity experiences. In particular, we propose that the predictions of the model are somewhat attenuated for those who do not currently possess a sexual minority identity (even if they previously did) and for those whose sexual minority identities are not central to their self-concept. For instance, individuals without a sexual minority identity (e.g., someone who, despite engaging in same-gender sexual behavior, identifies comfortably as heterosexual) are less likely to internalize a negative sense of difference as self-applicable; these individuals are also less likely to experience belongingness threats or the toll of secrecy based on a sexual minority identity. However, if and when the individual moves toward a sexual minority identity, the closet-related experiences predicted by the model are expected to become relevant at the point of self-identification. Conversely, if the individual moves away from a sexual minority identity, the closet-related experiences are expected to attenuate. Because the model is focused on identity, it does not make predictions about a person’s experience of the closet based on their sexual attractions or behaviors. Overall, compared to those who persist in a sexual minority identity across the life course, those who move into and out of a sexual minority identity fluidly are expected to only experience the workings of the closet to the extent that the closet is an experience that can be interpreted through the lens of their current identity (Klein et al., 2015; McLean, 2007).

Further, sexual identity fluidity entails not only movement into and out of a sexual minority identity but also movement across various sexual minority identities (e.g., gay/lesbian to/from bisexual). Although the prevalence of such fluidity varies widely across studies, in general, sexual identities are stable for most sexual minority individuals with no particularly predominant pattern of movement from one particular sexual minority identity to another (Campbell et al., 2021; Diamond et al, 2003; Ott et al., 2011; Rosario et al., 2006; Savin-Williams, 2012). Because all sexual minority identities can be associated with stigma, even if this stigma varies depending on the identity, the general predictions of the Developmental Model of the Closet are argued to apply regardless of sexual minority identity and movement across sexual minority identities, although this postulation awaits further empirical study.

Similarly, the predictions of the model are expected to be strongest for those whose sexual minority identities are most central to their overall self-concept. That is, to the extent that individuals experience their sexual identity as particularly self-definitional (Dyar et al., 2015), pre-closet socialization is expected to be particularly salient and the impact and persistence of closet-related coping is likely strengthened. This tenet is partially supported by research on individuals who hold a concealable stigmatized identity, which finds those with more central identities report more stigma-related psychosocial experiences, such as internalized stigma (Overstreet et al., 2017) and anticipated stigma (Quinn et al., 2014). This moderating effect is likely to apply to most or all of the threats and stressors discussed within the Developmental Model of the Closet. For example, it is easy to imagine that the effort and burden associated with keeping one’s sexual orientation a secret would be more intense and heavier among those whose sexual identity is central to their self-concept.

Overall, the model suggests that the degree to which an individual experiences the model’s predictions (e.g., internalized cultural ideologies during the pre-closet, closet-related stressors and adaptations, and persistent closet-related adaptations versus post-closet growth) is contingent on their endorsement of a sexual minority identity and the centrality of this identity during each of the model’s periods (Hypothesis 11; Table 1).

Implications of the Model for Future Research

Although the model presented here emerges from substantial research supporting many of its components, some of its exact predictions are speculative. These predictions are presented as testable hypotheses for future research in Table 1. Here we present several research directions capable of testing these hypotheses, organized in terms of the three periods proposed by the model, the model’s proposed moderators, and the possibility that interventions can reduce the closet’s duration, stressors, and required adaptations.

Future Research on the Pre-closet