Abstract

Introduction

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in breast cancer are associated with a poor prognosis. Early studies of TAMs were largely limited to the pan-macrophage marker CD68, however, more recently, an increasing number of studies have used CD163, a marker expressed by alternatively activated M2 macrophages and TAM subsets. We hypothesized that CD163-positive (CD163+) TAMs would be a better predictor of survival outcomes in breast cancer compared to CD68+ TAMs.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search of trials (from 1900 to August 2020) reporting overall survival (OS) or progression-free survival (PFS), breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS), TAM phenotype, and density. Thirty-two studies with 8446 patients were included. Meta-analyses were carried out on hazard ratios (HRs) for survival outcomes of breast cancer patients with a high density of TAMs (CD68+ and/or CD163+) compared to a low density of TAMs.

Results

A high density of TAMs (CD68+ and/or CD163+) was associated with decreased OS (HR 1.69, 95% CI 1.37–2.07) and reduced PFS (HR 1.64; 95% CI 1.35–1.99). Subgrouping by CD marker type showed a lower OS for high density of CD163+ TAMs (HR 2.24; 95% CI 1.71–2.92) compared to a high density of CD68+ TAMs (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.12–2). A high density of TAMs (CD68+ and/or CD163+) in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cases was associated with lower OS (HR 2.81, 95% CI 1.35–5.84).

Conclusion

Compared to CD68+ TAMs, a high density of CD163+ TAMs that express a similar phenotype to M2 macrophages are a better predictor of poor survival outcomes in breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Tumor-associated macrophage, CD68, CD163, Prognosis, Triple-negative breast cancer

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| TAMs are known to play critical roles in the development, progression, and metastasis of breast cancer. However, the breast cancer microenvironment contains several subsets of macrophages, including pro-inflammatory M1, anti-inflammatory M2, and M2-like TAMs. |

| Previous meta-analyses have predominantly contained studies that used pan-macrophage markers, whereas more recent studies have expanded to include markers that identify macrophage subsets. |

| Our hypothesis was that markers of M2 macrophages and M2-like TAMs would be a better predictor of survival outcomes in breast cancer compared to non-specific macrophage markers. |

| What was learned from this study? |

| In breast cancer, a high density of CD163+ TAMs that express a similar phenotype to alternatively activated macrophages are a better predictor of poor clinical outcomes. |

| Future studies should use a larger number of antibodies that identify specific macrophage subsets in the breast cancer tumor microenvironment. |

Introduction

Breast cancers consist of complex cellular microenvironments where interactions between tumor cells, stroma, and immune cells influence cancer cell growth and response to treatment [1]. One of the most studied immune cell populations is tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). These play critical roles in the development, progression, and metastasis of breast cancer, and in future risk models could be included together with tumor size and nodal status to guide treatment decisions [2]. However, the lack of reliable and specific markers to identify and differentiate TAM subsets has limited the development of prognostic algorithms or development of targeted therapies. Further complicating targeting of TAMs is that specific subsets may alternatively facilitate or inhibit neoplastic transformation and metastasis [3–5]. All macrophages, including TAMs, show a high level of plasticity and variation in phenotype and activation state that are modified by the microenvironment [6]. These differences may explain the discrepant results of studies of TAMs in the biologic regulation of cancers [7–9]. It is therefore essential to identify breast cancer TAM subtypes using differentially expressed markers that can be used in association studies of survival outcomes.

Breast cancer TAMs are derived from peripheral blood monocytes that migrate into the tumor and differentiate into several subtypes [4, 10, 11]. Historically, macrophages have been classified as classically activated, pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, and alternatively activated anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages that secrete immunosuppressive cytokines [3]. This binary model has been superseded by a spectrum model of polarization following the discovery of non M1/M2 macrophages that include TAMs [4]. Although a distinct macrophage subtype, breast cancer TAMs express a number of markers, including CD163, Fc fragment of IgG and C-type lectin domains, which are also expressed by M2 macrophages [4]. Our current understanding of the association between TAM density in breast cancer tissue and clinical outcomes relies on retrospective cohort studies that have used one or two clusters of differentiation (CD) markers that identify M1 and M2 macrophages rather than panels of markers that define TAM subsets [12]. Most studies have used the pan-macrophage marker CD68 to identify TAMs, however this marker does not discriminate between M1 and M2 macrophages and TAMs [4, 13].

A systematic review and meta-analysis performed by Zhao et al. [14] that included 16 studies performed from 1996 to 2016 found that CD68 was more highly associated with lower overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) compared to CD163 [14]. However, this analysis was limited by the inclusion of only three studies of OS that used CD163, and one study that included CD206 and CD40. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 13 studies from 2005 to 2018 by Ni et al. [15] included only three studies that assessed 5-year OS and relapse-free survival (RFS) using CD163+ TAM density [15].

Breast cancer has traditionally been classified based on expression of the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Although the molecular heterogeneity of cancers that lack expression of these receptors has been well described, they are often grouped as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [16]. In addition to the importance of TAM markers, it has become increasingly recognized that breast cancer subtype and microanatomical location influence TAM phenotype and behavior [17].

Following the publication of the two latest systematic reviews and meta-analyses of TAMs and breast cancer [14, 15], several studies have been published that analyzed the association between breast cancer survival outcomes, CD163+ TAM density, TAM location in the tumor, and TNBC. The present systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to update the current knowledge on the significance of breast cancer TAM phenotype and focus on studies that report associations between TAM density and OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS).

Methods

A systematic search of Medline (from 1950 to August 2020), Embase (from 1947 to August 2020), Web of Science (from 1900 to August 2020), and Google Scholar (first 30 pages of results) was used to identify relevant articles. Search terms used were “breast cancer”, “breast tumor” or “breast neoplasm” and “macrophages” or “tumor-associated macrophage” and “survival”, “prognosis” or “progression” as text word search and medical subject headings where applicable. The references of identified articles were manually searched for additional relevant studies. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed [18]. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Consistent with The National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, this systematic review and meta-analysis of published and non-identifiable data is exempt from the requirement for ethical review.

Study Selection

We included studies that met the following inclusion criteria: (1) proven diagnosis of breast cancer by pathology; (2) reported TAM density by CD68 or CD163 using immunohistochemistry; (3) assessment of OS, PFS, or BCSS with respect to TAM density; (4) risk reported as a hazard ratio (HR); (5) 95% confidence interval (CI) reported; and (6) full-text English language studies.

Data Extraction

One author (EA) extracted the data, which were checked by a second author (JM). HRs with 95% confidence intervals were collected and checked using reported p values. The names and affiliations of authors were cross-checked to ensure duplicate data were not included.

Statistical Analysis

Subjects were divided into those with (1) a low density of TAMs (low TAM) and (2) a high density of TAMs (high TAM). The study HRs represent the risk for the “high density of TAMs” group compared to the “low density of TAMs” group. There was some clustering of HR effect sizes within studies for different TAM groups because the HR in each case used the same “low density of TAMs” reference group. Consequently, the validity of a two-level meta-analysis model was checked against a three-level model, where level 1 was individual participant information, level 2 the high density of TAMs group within a study, and level 3 the individual study. A comparison of model fit between the two- and three-level models using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) showed that the two-level model was preferred. All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software https://www.r-project.org/. The primary R package used for the analysis was the “meta” package and for the multilevel analysis, the “metafor” package. For the meta-analyses, the metagen function from the meta package was used and the restricted maximum likelihood method for random effects [19–21]. The Hartung–Knapp adjustment was also used for random effects analysis [22].

Results

Description of the Studies

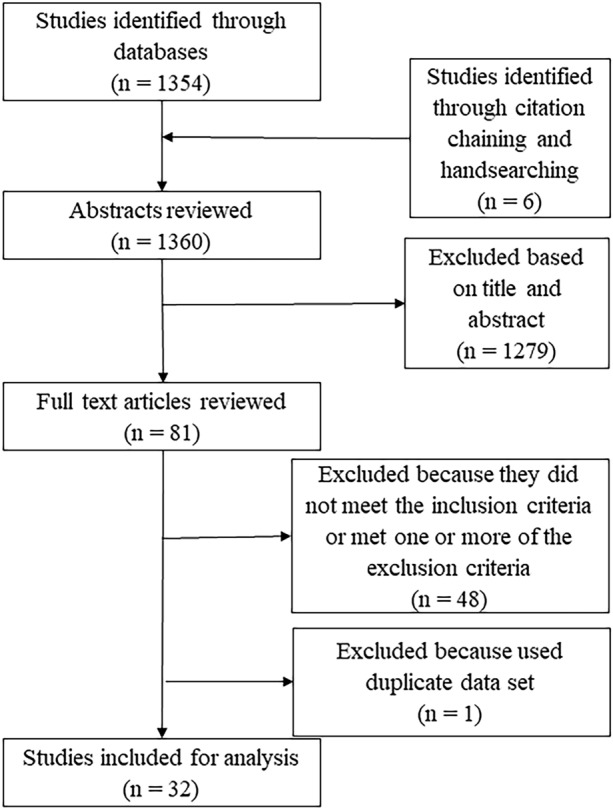

Search results yielded 1354 articles including six studies identified through citation chaining and handsearching. Of these, 1279 were excluded based on title and abstract. After careful review of 81 full-text articles, one was excluded due to analyses of duplicate data sets and 48 were excluded that did not meet the inclusion criteria, leaving 32 articles for inclusion in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Where articles met inclusion criteria but did not report OS, PFS, or BCSS with HRs, the authors were contacted for clarification.

Fig. 1.

Process of study selection for the meta-analysis

All studies were retrospective cohort studies and used immunohistochemical staining to identify TAMs in paraffin-embedded tumor samples (Table 1). Pelekanou et al. [23] and Mohamed et al. [24] included two separate populations within one article and these were analyzed separately. There was heterogeneity in methods for determining TAM density (Table 1). Furthermore, for each method, there were no standardized cut-offs to define the high density of TAMs. For example, the definition of high density for HPF ranged from > 5 to > 61 per HPF. With respect to tissue distribution of TAMs, there were 12 studies reporting density in tumor stroma and 11 studies reporting density in tumor nest.

Table 1.

Characteristics of eligible studies

| Author | Year | Cases | Follow-up median (months) | Population | Country | Tissue distribution | Definition of high-density TAM | Result | NOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang, et al. [25] | 2015 | 100 | 60 | Women with invasive breast carcinoma 2005–2013 | China | TN and TS | > 61.14 ± 23.76/ HPF | OS | 7 |

| Gwak et al. [26] | 2015 | 372 | 92 | 1 hospital; 276 consecutive cases resected from May 2003 to December 2006; + 96 cases resected from June 2005 to December 2011 (hormone negative) | South Korea | TN and TS | Median extent of infiltration. Intra-tumoral > 24.2/HPF; stromal TAMs 35.3 /HPF | PFS | 7 |

| Adams et al. [27] | 2018 | 180 | 120 | 1 hospital, largely consecutive patients with triple-negative breast cancer | USA | NS | > 20% | OS | 7 |

| Campbell et al. [28] | 2011 | 216 | 108 | 2 hospitals | USA | NS | 5/HPF | OS, PFS | 7 |

| Campbell et al. [29] | 2013 | 102 | 36 | Multicenter; histologically confirmed invasive breast cancers; at least 3 cm; no distant metastases | USA | NS | > 24/HPF | PFS | 7 |

| Carrio et al. [30] | 2013 | 29 | 138 | Random selection: women treated for PR- breast cancer between 1978 and 1996 at 2 Miami hospitals | USA | TN | No detectable expression; +, moderate expression (1–5 macrophages/slide); ++, strong expression (5–10 macrophages/slide); +++, very strong expression (10–20 macrophages/slide) and ++++, super strong expression (> 20 macrophages/slide) | OS | 7 |

| Chen et al. [31] | 2011 | 562 | 45 | Primary ductal carcinomas of the breasts at one hospital from January 2002 to October 2007 | China | TS | > 20 per view of field | OS | 6 |

| Esbona et al. [32] | 2018 | 371 | 100 | University of Wisconsin Biobank | USA | TN and TS | Expression of CD68 and CD163 > 75th percentile of the data, were considered as high expression or high infiltration | OS, PFS | |

| Jamiyan et al. [33] | 2020 | 107 | NS | Consecutive TNBC in one hospital between 2006 and 2018 | Japan | TN and TS | CD68 in TS was 26.2, CD68 in TN was 11.2, CD163 in TS was 26.6, CD163 in TN was 8.6 | OS, PFS | |

| Jeong et al. [34] | 2019 | 367 | 111 | Invasive breast cancer patients who underwent surgery at one hospital between 2000 and 2007: wide variety of histopathology | Korea | TN and TS |

Overall survival: CD68 in TS: 17.8, CD68 in TN: 33 CD163 in TS: 21, CD163 in TN: 1.67 PFS: CD68 in TS: 17.8, CD68 in TN: 33 CD163 in TS: 20, CD163 in TN: 1.67 |

OS, PFS | |

| Leek et al. [35] | 1996 | 101 | NS | Consecutive series of 101 breast carcinomas | England | NS | Low < 12; High > 18 | OS, PFS | 6 |

| Liu et al. [36] | 2017 | 102 | 39 | Patients with invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the breast had undergone mammectomy at one Chinese hospital between May 2009 and March 2013; Not including metastasis | China | NS | Not defined | OS, PFS | 7 |

| Mahmoud et al. [37] | 2012 | 1322 | 127 | Primary invasive breast carcinoma diagnosed between 1987 and 1998 and entered into the Nottingham Tenovus Primary Breast Carcinoma series | England | TN and TS |

TS > 17/HPF TN > 6/HPF |

OS, PFS, BCSS | 6 |

| Medrek et al. [38] | 2012 | 144 | 79 | Patients diagnosed with invasive breast cancer at one hospital between 2001 and 2002 | Sweden | TN and TS | Absent/sparse (0–2); dense (3). No specific numbers given | PFS, BCSS | 7 |

| Miyasato et al. [39] | 2017 | 149 | NS | Diagnosed with invasive ductal carcinoma from 2001 to 2012 in one hospital | Japan | NS |

CD204-positive Low: ≤ 200; High: > 200 CD163-positive Low: ≤ 145; High > 145 CD68-positive Low: ≤ 190; High > 190 |

PFS, BCSS | 5 |

| Mohammed et al. [24] | 2012 | 159 | 165 | Invasive ductal breast cancer at 2 centers in Scotland between 1995 and 1998. ER-positive | Scotland | NS | Top tertile; translating to > 3% | OS, PFS, BCSS | |

| Mohammed et al. [24] | 2012 | 283 | 165 | Invasive ductal breast cancer at 2 centers in Scotland between 1995 and 1998. ER-negative | Scotland | NS | Top tertile; translating to > 3% | OS, PFS, BCSS | |

| Morita et al. [40] | 2017 | 53 | NS | DCIS 1988–1989 in one center | USA | TN and TS | > 21/HPF | PFS | 5 |

| Mukhtar et al. [41] | 2011 | 70 | 87 | Consecutive cases of breast cancer in one community center | USA | NS | > 5/HPF | OS | 7 |

|

Mukhtar et al [42] |

2012 | 367 | 112 | 116 consecutive patients with breast cancer between 1989 and 1997 | USA, Nigeria, Senegal | NS | > 10% staining | PFS | 6 |

| Murri et al. [43] | 2008 | 168 | 72 | Consecutive BC cases in 2 hospitals | Scotland | NS | Tertile | OS | 6 |

| Pelekanou et al. [23] | 2018 | 398 | 139 | Mixed ER-positive and -negative between 1976 and 2005 at one university center | USA | NS | Median quantitative immunofluorescence (QIF) score value was used as cut point to determine low and high cases | OS | 6 |

| Pelekanou et al. [23] | 2018 | 156 | 52 | TNBC between 1998 and 2004 at one university center | USA | NS | Not defined | OS | |

| Richardsen et al. [44] | 2015 | 68 | 200 | BC diagnosis between 1985 and 2003 | Norway | TN and TS | Not defined | BCSS | 5 |

| Shabo et al. [45] | 2008 | 127 | 156 | Stage 2 BC several centers in one country (years unknown) | Sweden | NS | more than 25% of the cancer cells were stained | OS, BCSS | 5 |

| Shiota et al. [46] | 2016 | 146 | 86 | Diagnosis of ductal carcinoma between 2001 and 2008 at one center | Japan | Regional lymph node | Not defined | PFS BCSS | 6 |

| Sousa et al. [47] | 2015 | 562 | 35 | n = 562 out of 1199 patients from the FinXX study | Finland and Sweden | NS | > 369/mm2 | OS, PFS, BCSS | |

| Tiainen et al. [48] | 2020 | 262 | 116 | Operated due to BC at one hospital between 2002 and 2008 | Finland | NS | values higher than the median | OS, BCSS | 6 |

| Yang et al. [49] | 2018 | 200 | 66 | Contiguous cases of basal-like breast cancer in one center between April 2006 and December 2007 | China | TN and TS |

CD163+ and CD68 TS > 36 macrophages/0.24 mm2 CD163 and CD68 TN > 11 macrophages/0.24 mm2 |

OS, PFS | 7 |

| Tsutsui et al. [50] | 2005 | 249 | 90 | Breast surgery on those with invasive ductal carcinoma between 1985 and 1999 in one center | Japan | NS | TAM density > 55th percentile of all tumors reviewed | PFS | |

| Yuan et al. [51] | 2019 | 217 | 60 | Primary invasive breast cancer, nil prior treatment; randomly selected from cases between 2009 and 2010; single center | China | NS | Multiplication of staining intensity and number of cells (Low 0–6; High 7–12) | PFS | |

| Yuan et al. [52] | 2014 | 287 | 89 | TNBC without distant metastasis undergoing surgery between 2000 and 2008; single center | China | TS | 16 TAMs per HPF | PFS | |

| Zhang et al. [53] | 2018 | 278 | 87 | TNBC without distant metastasis undergoing surgery between 2004 and 2008; single center | China | NS | Values higher than the median | OS, PFS | |

| Zhang et al. [54] | 2013 | 172 | 60 | Primary mastectomies without distant metastasis between January 2006 and June 2007; single center | China | NS | > 26 TAMs per tissue core | OS | |

| Total number | 8446 | ||||||||

TN tumor nest, TS tumor stroma, OS overall survival, PFS progression-free survival, BCSS breast cancer-specific survival, NOS Newcastle–Ottawa Scale checklist, TNBC triple-negative breast cancer, BC breast cancer, NS not stated, HPF high-power field

High Density of TAMs Survival Outcomes

OS was reported in 20 studies that included CD68+ and/or CD163+ TAMs (Table 1). To determine whether clustering should be considered, the model fit for the full three-level model was compared to the reduced two-level model. AIC was lower for the two-level model compared to the three-level model (93.8 vs. 95.8) that indicated negligible clustering within studies [55], and the two-level model, with a lower AIC, was used for the analysis. The OS meta-analysis showed that a high density of TAMs was associated with a lower OS (HR 1.69, 95% CI 1.37–2.07) (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of HRs for TAM density and outcomes. Forest plots and meta-analyses of studies evaluating HRs of high density of TAMs compared to low density. A OS, B PFS, C BCSS. Note: Where reported, CD marker and tumor location were analyzed separately

PFS was reported in 19 studies. The AIC was lower for the two-level model compared to the 3-level model (83.26 vs. 85.26) and the two-level model was used for the analysis. PFS meta-analysis showed high density of TAMs was associated with a lower PFS (HR 1.64, 95% CI 1.35–1.99) (Fig. 2B).

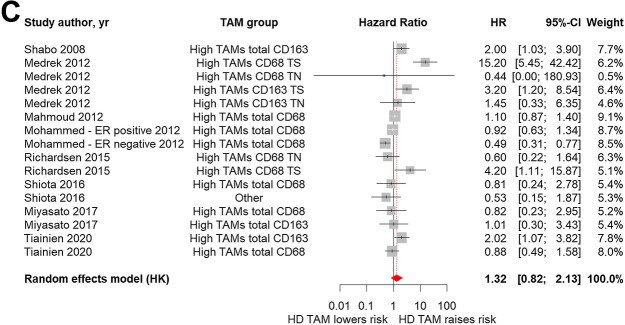

BCSS was reported in 9 studies (Fig. 2C). The AIC for the two-level model was again lower than the three-level model and the reduced model was used for the meta-analysis. BCSS meta-analysis showed the summary HR was 1.32, however the confidence interval crossed unity (95% CI 0.82–2.13). There were fewer studies for BCSS and high heterogeneity [Q (df = 15) = 57.09, p < 0.0001].

Sub-group Analyses

High density of CD68+ TAMs versus CD163+ TAMs

There were 19 studies that analyzed the density of CD68+ and/or CD163+ TAMs, including Pelekanou et al. [23] (Table 1, studies 21a and 21b included in the same report). Studies where the CD marker type was “Other” were omitted. The forest plot with subgrouping by CD marker type showed lower OS for a high density of CD163+ TAMs (HR 2.24; 95% CI 1.71–2.92) compared to a high density of CD68+ TAMs (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.12–2) (Fig. 3A). The random effects test for this difference was significant (p = 0.03). There was a trend for lower PFS for high density of CD163 + TAMs (HR 2.03; 95% CI 1.51–2.73) versus CD68+ TAMs (HR 1.53; 95% CI 1.18–1.98), however this was not significant (Fig. 3B). There were nine studies that reported the density of CD68+ and/or CD163+ TAMs and BCSS, with no difference between high densities for each CD marker (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of HRs for high density of CD68+ TAMs compared to high density of CD163+ TAMs. A OS, B PFS

High Density of TAMs in Triple-negative Breast Cancer

TAM density in TNBC and OS was analyzed in 20 studies, including Pelekanou et al. [23]. TNBC cases with a high density of TAMs had a lower OS (HR 2.81, 95% CI 1.35–5.84) compared to non-TNBC cases (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.27–1.93) (Fig. 4A) although this difference was not significant (p = 0.07). Similarly, there was a lower PFS in high density of TAMs in TNBC cases (HR 2.37; 95% CI 0.99–5.65) versus non-TNBC cases (HR 1.56; 95% CI 1.28–1.9) (Fig. 4B) that was not significant. There were no eligible studies that reported TAM densities and BCSS in TNBC.

Fig. 4.

Forest plots of HRs for high density of TAMs in TNBC. A OS, B PFS

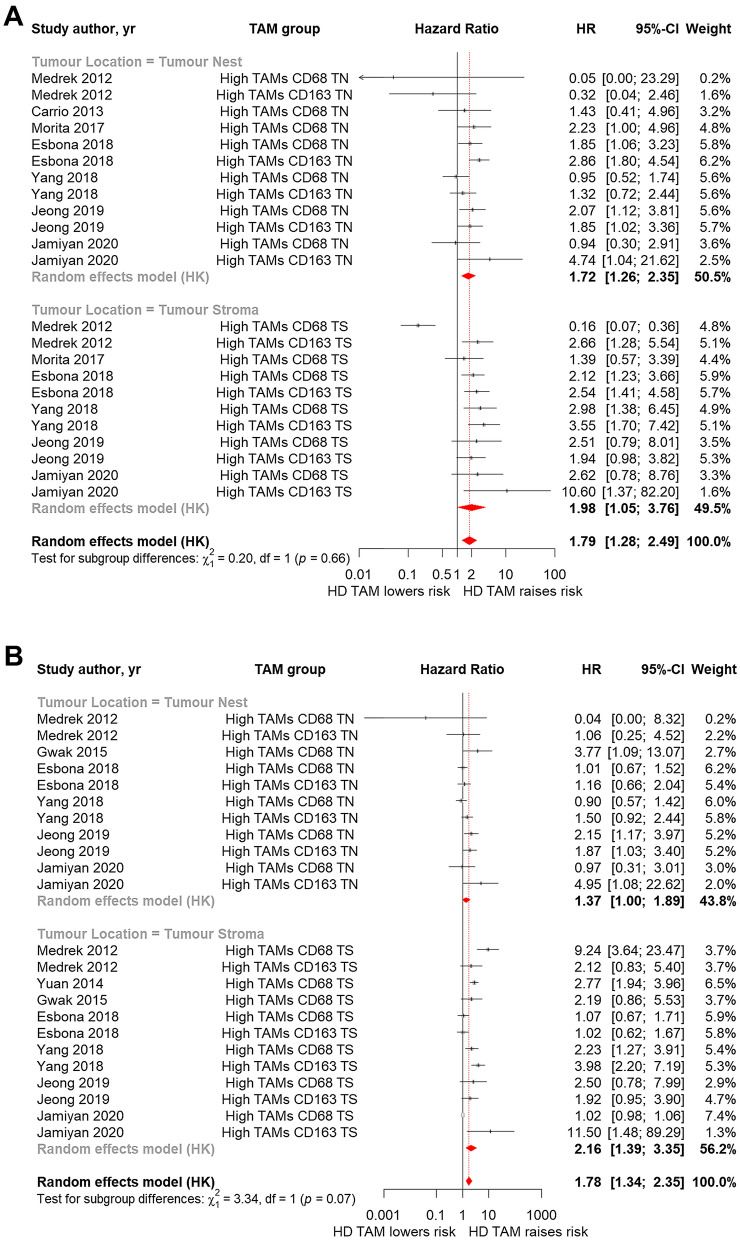

Location of TAMs in the Tumor

There were seven studies that analyzed OS by location of TAMs in the tumor nest (TN) or tumor stroma (TS). The forest plot with subgrouping by tumor location showed no difference in OS for high TAMs in the TN (HR 1.72; 95% CI 1.26–2.35) compared to the TS (HR 1.98; 95% CI 1.05–3.76) (Fig. 5A). In seven studies, there was a trend for lower PFS for high density of TAMs in the TS (HR 2.16; 95% CI 1.39–3.35) compared to the TN (HR 1.37; 95% CI 1.0–1.89), however this was not significant (p = 0.07) (Fig. 5B). There was lower BCSS in tumors with a high density of TAMs in the TS (HR 5.99; 95% CI 0.72–49.89) compared to TN (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.22–2.77; p = 0.0004), however there were only two studies in this analysis (not shown).

Fig. 5.

Forest plots of HRs for high density of TAMs and tumor location. A OS, B PFS

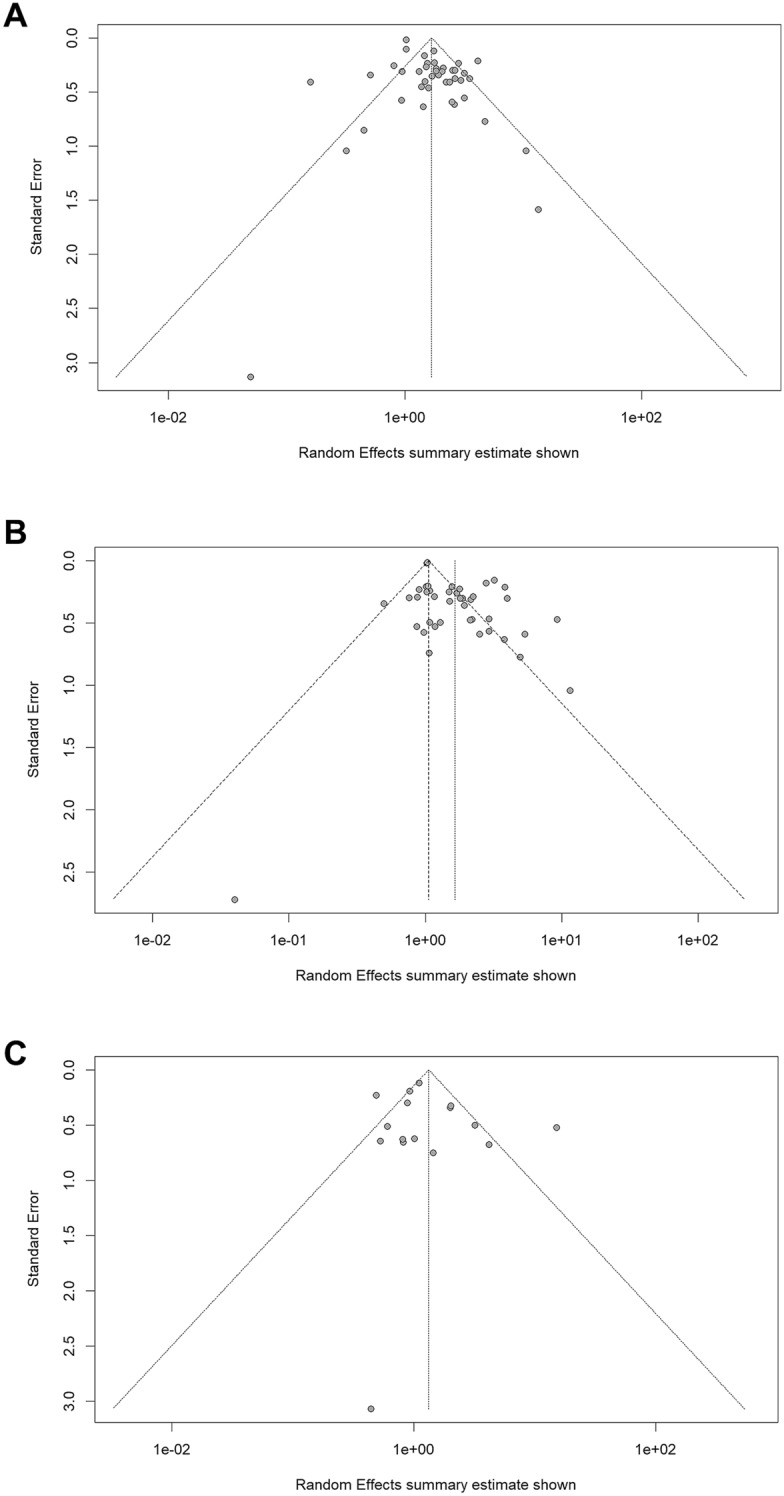

Publication Bias

To evaluate publication bias for each outcome, we used a funnel plot analysis of standard error versus random effects summary estimate. For OS, most studies were clustered towards the top indicating high precision (Fig. 6A). There were very few small studies and on inspection the plot was symmetric. The heterogeneity test was significant, with Q (df = 41) = 224.19, p < 0.0001. Compared to OS, the funnel plot analysis for PFS showed a broader horizontal scatter with slight skewing of studies to the right-hand side (Fig. 6B). The heterogeneity test was significant, with Q (df = 40) = 240.95, p < 0.0001. For BCSS, the funnel plot showed symmetry albeit with outlier studies on both sides (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Funnel graphs for assessment of potential publication bias in studies of density of TAMs in patients with breast cancer. A OS, B PFS, C BCSS

Discussion

Breast cancer TAMs are derived from circulating monocytes that differentiate under the influence of the tumor environment and promote progression and metastasis [12, 56]. TAMs express distinct proteins that can be used for prognostic algorithms and provide targets for therapy [12]. To date, however, a limited number of proteins have been included in association studies of TAM density and breast cancer survival outcomes. The most used marker in survival studies has been the pan-macrophage marker CD68 that in more recent studies has been combined with CD163 in immunohistochemistry studies of cancer tissue [23, 27, 32–34, 36, 38, 48, 53]. To distinguish from classically activated M1 macrophages, CD163 has been identified as a marker for alternatively activated M2 macrophages that are stimulated by IL-4 and IL-13; and secrete IL-10 and transforming growth factor β [57]. Although the binary model of M1 and M2 macrophages has been superseded by a spectrum model [4], most TAM subsets also express CD163 and its expression has been associated with other breast TAM markers including CD169 [12]. Considering that the recent studies of TAM density and prognosis have included CD163, we hypothesized that TAM expression of CD163 would be a better predictor of survival outcomes compared to CD68. A systematic review and meta-analysis of association studies comparing the densities of CD68+ and/or CD163+ TAMs and survival outcomes showed that a high density of TAMs (CD68+ and/or CD163+) was associated with decreased OS and reduced PFS (Fig. 2A, B, respectively). Furthermore, a high density of CD163+ TAMs was a better predictor of shorter OS compared to CD68+ TAMs (Fig. 3A). Although there was a trend for lower PFS for high density of CD163+ TAMs, this was not superior to CD68+ (Fig. 3B). There were fewer studies for BCSS and high heterogeneity. Consequently, the summary HR CIs crossed unity for high density of TAMs (CD68+ and/or CD163) and sub-group analyses of CD163+ TAMs, TNBC cases, and TAM location in the tumor.

In relation to the better predictive value of the high density of CD163+ TAMs compared to CD68+, our finding differed from a meta-analysis by Zhao et al. that showed CD163 was not superior to CD68 [14]. Zhao et al. included studies from PubMed (MEDLINE), Web of Science, and Embase from inception to July 1, 2016. There were 16 studies that met the inclusion criteria, including TAMs expressing CD68, CD206, and/or CD163 and correlations between TAM density and OS, DFS, RFS, BCSS, and clinicopathological features. A high density of TAMs of any phenotype was associated with poor OS (HR 1.5; 95% CI 1.2–1.88), however subgroup analysis of CD markers showed CD68 (HR 1.83; 95% CI 1.41–2.38) was a better predictor compared to CD163 (HR 1.13; 95% CI 0.62–2.07). Subgroup analyses for CD markers and DFS, RFS, and BCSS were not performed [14].

A more recent meta-analysis by Ni et al. included studies through February 2018 [15]. Analyses were performed on 13 studies that included densities of CD163+ or CD68+ TAMs, survival outcomes and clinicopathological features. Only three studies reported 5-year OS and RFS based on CD163+ TAMs. Considering the limited number of studies, high density of CD163+ TAMs showed shorter 5-year OS [risk ratio (RR) 2.12; 95% CI 1.09–4.13] and RFS (RR 1.93; 95% CI 1.23–3.04). Similarly, a high density of CD68+ TAMs predicted lower 5-year OS (RR 1.58; 95% CI 1.35–1.84) and RFS (RR 1.74; 95% CI 1.44–2.11). Non-metastatic breast cancer was an eligibility criterion and risk ratios (RR) were used, however our analysis only included studies reporting the HR, which is preferred for analysis of study events over time in longitudinal studies [58].

There is evidence that TAM polarization is influenced by cancer subtype [59], and molecular subtypes of breast cancer are classified as ER+, PR+, HER2+, and TNBC based on receptor expression. This classification is used to guide prognosis and therapy and the presence of ER, PR, and HER2 overexpression has enabled the development of targeted therapies [60]. However, treatment of TNBC currently lacks an option for targeted therapy and carries a poor prognosis. Although a biologically heterogenous disease [16], in TAM studies TNBC has been studied as a single entity. There are conflicting results relating to the prognostic significance of TAMs in TNBC [26, 33, 61]. In the Zhao et al. metanalysis [14], only one study of TNBC was included that reported outcomes for high and low density of TAMs [52]. This study showed a shorter DFS for high density of CD163+ TAMs (HR 2.2; 95% CI 1.53–3.16) [52]. In the Ni et al. study [15], a subgroup analysis found associations between TNBC and both higher density of CD68+ TAMs (RR 1.90; 95% CI 1.63–2.21) and CD163+ TAMs (RR 1.46; 95% CI 0.64–3.33), although only three studies of a high density of CD163+ were included, and the summary RR confidence interval crossed unity [15]. In our study, there was a trend for lower OS associated with high density of CD163+ and/or CD68+ TAMs in TNBC (HR 2.81, 95% CI 1.35–5.84) compared to non-TNBC cases (HR 1.57, 95% CI 1.27–1.93), although this analysis was limited to four studies and only three included a high density of CD163+ TAMs [23, 27, 33, 53]. For PFS, the HR estimate for TNBC was higher at 2.37 compared to 1.56 for non-TNBC, but there was overlap in the CIs (Fig. 4B).

Breast cancer progression is influenced by interactions between tumor cells, stromal cells, and other cellular elements. The TS is the source of growth factors, chemokines, and cytokines [62, 63], and the ratio of TN to TS predicts outcomes in several cancers, including breast cancer [64]. The anatomical location of TAMs within the tumor stroma and nest influences macrophage polarization [10, 12], and consequently associations between survival outcomes and TAM density in the TN and TS have been studied. However, our meta-analysis was limited by low numbers of studies that assessed OS (n = 7), PFS (n = 6), and BCSS (n = 2). There were no differences in OS and PFS for high density of TAMS in the TS or TN, however a high density of TAMs in the TS was associated with lower BCSS (HR 5.99; 95% CI 0.72–49.89) compared to TN (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.22–2.77) (p = 0.0004). The Zhao et al. [14] meta-analysis found lower survival outcomes in cases with high density of TAMs in TS compared to TN, however like our meta-analysis, there were a limited number of studies analyzed.

Although it is well documented that the presence of CD68+ TAMs in breast cancer is associated with a poor prognosis, it is only recently that bulk- and single-cell RNA and DNA sequencing have enabled an understanding of the heterogeneity of macrophages that infiltrate breast cancer tissue [12, 65]. The aim of these studies is to identify proteins differentially expressed by pro-tumor TAMs that can be targeted by treatments. Identifying prognostic factors and protein targets while avoiding off-target toxicities requires identification of gene and protein signatures that are specific to TAM subtypes, and TAM-specific mRNA signatures have been identified that are associated with poor survival outcomes [12, 66]. A highly upregulated gene in one of these TAM signatures is SIGLEC1 that encodes CD169 [12]. In a study by Cassetta et al., high expression of SIGLEC1 corresponded with high CD163 mRNA, and CD169 protein expression combined with CD163, CSFR1, CCR2, and CD68 identified three breast cancer TAMS (CSFR1+CCR2−CD68+CD163+SIGLEC1−, CSFR1+CCR2−CD68+CD163+SIGLEC1+, and CSFR1+CCR2−CD68+CD163−SIGLEC1+) that are enriched in TNBC cases [12]. Our finding that the density of CD163+ TAMs is a better marker for survival outcomes compared to CD68+ TAMs contributes to the growing evidence that specific TAM subgroups dictate tumor progression, metastasis, and ultimately survival outcomes. A major limitation to previous studies, and consequently meta-analyses, is the lack of a definition of high versus low TAM density (Table 1). Similarly, the definition of TS and TN is highly variable amongst studies. Consequently, there is a need to standardize TAM density and tumor microarchitecture. The significance of TAM phenotype and density may vary according to the breast cancer subtype, and between the early and metastatic setting. However, only six studies included samples from metastatic stage 4 breast cancer [25, 27, 28, 44, 54, 67], and only one study included prognostic data based on stage and TAM density [54]. Zhang et al. [54] demonstrated that in both early breast cancer (stage I–II, and node negative) and invasive breast cancer (stage III), high CD68+ TAM density was associated with lower OS. Further studies are required to characterize the significance of TAM infiltration in the early and metastatic settings. A further limitation to this study was the reliance on CD68 and CD163 as markers of TAMs. There were several studies that used other immunohistochemical markers including CD204 [39], CD11c+ [34], CD206 [67], PCNA [41, 42], MMP-9 [23], and CD169 [46]. However, due to small numbers, these were not included in this analysis.

Conclusions

TAMs play critical roles in the development, progression, and metastasis of breast cancer, and could be included in future risk models and provide targets for treatment. We found that a high density of TAMs is associated with poor survival outcomes in breast cancer. Furthermore, a high density of CD163+ TAMs is a better predictor of poor outcomes, suggesting that TAMs expressing a similar phenotype to alternatively activated macrophages are responsible for tumor progression and metastasis. The studies included in this meta-analysis were limited by the low specificity of markers used to identify TAMs, and heterogeneity in definitions of TAM density and location in the tumor. It is expected that advances in microscopy technology, including the development of techniques that combine immunofluorescent imaging of several hundred proteins in a single sample at subcellular resolution, will enable identification of protein signatures of TAM subtypes that will complement existing single cell genomic studies [68].

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance provided by the Sydney Informatics Hub, a Core Research Facility of the University of Sydney. The authors would like to acknowledge Kristen K. Skarratt, Alison Webster, and Brooke Keogh for proofreading the manuscript.

Funding

The Nepean Medical Research Fund provided principal funding for the study. No funding or sponsorship was received for publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Eleanor Allison: study conception, literature search, data extraction, data, and statistical analysis, writing and editing of manuscript following critical review, tables and figures. Senarath Edirimanne: study conception, writing and editing of manuscript. Jim Matthews: literature search, data extraction, data, and statistical analysis, writing and editing of manuscript. Stephen J Fuller: study conception, writing and editing of manuscript.

Disclosures

Eleanor Allison, Senarath Edirimanne, Jim Matthews, and Stephen J. Fuller have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. Consistent with The National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, this systematic review and meta-analysis of published and non-identifiable data is exempt from the requirement for ethical review.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Cazet AS, Hui MN, Elsworth BL, Wu SZ, Roden D, Chan C-L, et al. Targeting stromal remodeling and cancer stem cell plasticity overcomes chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2897. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05220-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dushyanthen S, Beavis PA, Savas P, Teo ZL, Zhou C, Mansour M, et al. Relevance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in breast cancer. BMC Med. 2015;13:202. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0431-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeya M, Komohara Y. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in human malignancies: friend or foe? Pathol Int. 2016;66(9):491–505. doi: 10.1111/pin.12440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aras S, Zaidi MR. TAMeless traitors: macrophages in cancer progression and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(11):1583–1591. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2017.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams CB, Yeh ES, Soloff AC. Tumor-associated macrophages: unwitting accomplices in breast cancer malignancy. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2016;2(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/npjbcancer.2015.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gosselin D, Link VM, Romanoski CE, Fonseca GJ, Eichenfield DZ, Spann NJ, et al. Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell. 2014;159(6):1327–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dai F, Liu L, Che G, Yu N, Pu Q, Zhang S, et al. The number and microlocalization of tumor-associated immune cells are associated with patient's survival time in non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:220. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edin S, Wikberg ML, Dahlin AM, Rutegård J, Öberg Å, Oldenborg PA, et al. The distribution of macrophages with a M1 or M2 phenotype in relation to prognosis and the molecular characteristics of colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e47045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayama H, Nonomura N, Nishimura K, Oka D, Shiba M, Nakai Y, et al. Decreased immunostaining for macrophage scavenger receptor is associated with poor prognosis of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2009;103(4):470–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ham S, Lima LG, Lek E, Möller A. The impact of the cancer microenvironment on macrophage phenotypes. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1308. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizi E, Carr AJ, Plitas G, Cornish AE, Konopacki C, Prabhakaran S, et al. Single-cell immune map of breast carcinoma reveals diverse phenotypic states driven by the tumor microenvironment. cell. 2018;174(5):1293–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.05.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cassetta L, Fragkogianni S, Sims AH, Swierczak A, Forrester LM, Zhang H, et al. Human tumor-associated macrophage and monocyte transcriptional landscapes reveal cancer-specific reprogramming, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets. Cancer Cell. 2019;35(4):588–602.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ambarus CA, Krausz S, van Eijk M, Hamann J, Radstake TRDJ, Reedquist KA, et al. Systematic validation of specific phenotypic markers for in vitro polarized human macrophages. J Immunol Methods. 2012;31(375):196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2011.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X, Qu J, Sun Y, Wang J, Liu X, Wang F, et al. Prognostic significance of tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer: a meta-analysis of the literature. Oncotarget. 2017;8(18):30576–30586. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ni C, Yang L, Xu Q, Yuan H, Wang W, Xia W, et al. CD68- and CD163-positive tumor infiltrating macrophages in non-metastatic breast cancer: a retrospective study and meta-analysis. J Cancer. 2019;10(19):4463–4472. doi: 10.7150/jca.33914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ensenyat-Mendez M, Llinàs-Arias P, Orozco JIJ, Íñiguez-Muñoz S, Salomon MP, Sesé B, et al. Current triple-negative breast cancer subtypes: dissecting the most aggressive form of breast cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Yang C, Wei C, Wang S, Shi D, Zhang C, Lin X, et al. Elevated CD163(+)/CD68(+) ratio at tumor invasive front is closely associated with aggressive phenotype and poor prognosis in colorectal cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15(5):984–998. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.29836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G. An introduction to meta-analysis in R. In: Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Rücker G, editors. Meta-analysis with R. Cham: Springer; 2015. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Mental Health. 2019;22(4):153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36(3):1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v036.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.IntHout J, Ioannidis JPA, Borm GF. The Hartung–Knapp–Sidik–Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian–Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pelekanou V, Villarroel-Espindola F, Schalper KA, Pusztai L, Rimm DL. CD68, CD163, and matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) co-localization in breast tumor microenvironment predicts survival differently in ER-positive and -negative cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-1076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mohammed ZM, Going JJ, Edwards J, Elsberger B, Doughty JC, McMillan DC. The relationship between components of tumour inflammatory cell infiltrate and clinicopathological factors and survival in patients with primary operable invasive ductal breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012;107(5):864–873. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J, Li X, Liu X, Liu Y. The role of tumor-associated macrophages in breast carcinoma invasion and metastasis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(6):6656–6664. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gwak JM, Jang MH, Kim DI, Seo AN, Park SY. Prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophages according to histologic locations and hormone receptor status in breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0125728. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams TA, Vail PJ, Ruiz A, Mollaee M, McCue PA, Knudsen ES, et al. Composite analysis of immunological and metabolic markers defines novel subtypes of triple-negative breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2018;31(2):288–298. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2017.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell MJ, Tonlaar NY, Garwood ER, Huo D, Moore DH, Khramtsov AI, et al. Proliferating macrophages associated with high grade, hormone receptor negative breast cancer and poor clinical outcome. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(3):703–711. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campbell MJ, Wolf D, Mukhtar RA, Tandon V, Yau C, Au A, et al. The prognostic implications of macrophages expressing proliferating cell nuclear antigen in breast cancer depend on immune context. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e79114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrio R, Koru-Sengul T, Miao F, Glueck S, Lopez O, Selman Y, et al. Macrophages as independent prognostic factors in small T1 breast cancers. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(1):141–148. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Yao Y, Gong C, Yu F, Su S, Chen J, et al. CCL18 from tumor-associated macrophages promotes breast cancer metastasis via PITPNM3. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(4):541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esbona K, Yi Y, Saha S, Yu M, Van Doorn RR, Conklin MW, et al. The presence of cyclooxygenase 2, tumor-associated macrophages, and collagen alignment as prognostic markers for invasive breast carcinoma patients. Am J Pathol. 2018;188(3):559–573. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2017.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamiyan T, Kuroda H, Yamaguchi R, Abe A, Hayashi M. CD68- and CD163-positive tumor-associated macrophages in triple-negative cancer of the breast. Virchows Archiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Jeong H, Hwang I, Kang SH, Shin HC, Kwon SY. Tumor-associated macrophages as potential prognostic biomarkers of invasive breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2019;22(1):38–51. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2019.22.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leek RD, Lewis CE, Whitehouse R, Greenall M, Clarke J, Harris AL. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56(20):4625–4629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu H, Wang J, Liu Z, Wang L, Liu S, Zhang Q. Jagged1 modulated tumor-associated macrophage differentiation predicts poor prognosis in patients with invasive micropapillary carcinoma of the breast. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(16):e6663. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahmoud SM, Lee AH, Paish EC, Macmillan RD, Ellis IO, Green AR. Tumour-infiltrating macrophages and clinical outcome in breast cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(2):159–163. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2011-200355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Medrek C, Ponten F, Jirstrom K, Leandersson K. The presence of tumor associated macrophages in tumor stroma as a prognostic marker for breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:306. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyasato Y, Shiota T, Ohnishi K, Pan C, Yano H, Horlad H, et al. High density of CD 204-positive macrophages predicts worse clinical prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108(8):1693–1700. doi: 10.1111/cas.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morita Y, Zhang R, Leslie M, Adhikari S, Hasan N, Chervoneva I, et al. Pathologic evaluation of tumor-associated macrophage density and vessel inflammation in invasive breast carcinomas. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(2):2111–2118. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mukhtar RA, Moore AP, Nseyo O, Baehner FL, Au A, Moore DH, et al. Elevated PCNA+ tumor-associated macrophages in breast cancer are associated with early recurrence and non-Caucasian ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130(2):635–644. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1646-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukhtar RA, Moore AP, Tandon VJ, Nseyo O, Twomey P, Adisa CA, et al. Elevated levels of proliferating and recently migrated tumor-associated macrophages confer increased aggressiveness and worse outcomes in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(12):3979–3986. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murri AMA, Hilmy M, Bell J, Wilson C, McNicol AM, Lannigan A, et al. The relationship between the systemic inflammatory response, tumour proliferative activity, T-lymphocytic and macrophage infiltration, microvessel density and survival in patients with primary operable breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;99(7):1013–1019. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Richardsen E, Uglehus RD, Johnsen SH, Busund L-T. Macrophage-colony stimulating factor (CSF1) predicts breast cancer progression and mortality. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(2):865–874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shabo I, Stal O, Olsson H, Dore S, Svanvik J. Breast cancer expression of CD163, a macrophage scavenger receptor, is related to early distant recurrence and reduced patient survival. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(4):780–786. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiota T, Miyasato Y, Ohnishi K, Yamamoto-Ibusuki M, Yamamoto Y, Iwase H, et al. The clinical significance of CD169-positive lymph node macrophage in patients with breast cancer. PloS One. 2016;11(11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Sousa S, Brion R, Lintunen M, Kronqvist P, Sandholm J, Mönkkönen J, et al. Human breast cancer cells educate macrophages toward the M2 activation status. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0621-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tiainen S, Masarwah A, Oikari S, Rilla K, Hamalainen K, Sudah M, et al. Tumor microenvironment and breast cancer survival: combined effects of breast fat, M2 macrophages and hyaluronan create a dismal prognosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;179(3):565–575. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05491-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yang M, Li Z, Ren M, Li S, Zhang L, Zhang X, et al. Stromal infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages conferring poor prognosis of patients with basal-like breast carcinoma. J Cancer. 2018;9(13):2308–2316. doi: 10.7150/jca.25155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsutsui S, Yasuda K, Suzuki K, Tahara K, Higashi H, Era S. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic implications in breast cancer: the relationship with VEGF expression and microvessel density. Oncol Rep. 2005;14(2):425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan J, He H, Chen C, Wu J, Rao J, Yan H. Combined high expression of CD47 and CD68 is a novel prognostic factor for breast cancer patients. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:238. doi: 10.1186/s12935-019-0957-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yuan ZY, Luo RZ, Peng RJ, Wang SS, Xue C. High infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages in triple-negative breast cancer is associated with a higher risk of distant metastasis. Onco Targ Ther. 2014;7:1475–1480. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S61838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang W-J, Wang X-H, Gao S-T, Chen C, Xu X-Y, Zhou Z-H, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages correlate with phenomenon of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and contribute to poor prognosis in triple-negative breast cancer patients. J Surg Res. 2018;222:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2017.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Cheng S, Zhang M, Zhen L, Pang D, Zhang Q, et al. High-infiltration of tumor-associated macrophages predicts unfavorable clinical outcome for node-negative breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9):e76147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rücker G, Reiser V, Motschall E, Binder H, Meerpohl JJ, Antes G, et al. Boosting qualifies capture-recapture methods for estimating the comprehensiveness of literature searches for systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1364–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arwert EN, Harney AS, Entenberg D, Wang Y, Sahai E, Pollard JW, et al. A unidirectional transition from migratory to perivascular macrophage is required for tumor cell intravasation. Cell Rep. 2018;23(5):1239–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fan QM, Jing YY, Yu GF, Kou XR, Ye F, Gao L, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cancer stem cell-like properties via transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;352(2):160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.George A, Stead TS, Ganti L. What's the risk: differentiating risk ratios, odds ratios, and hazard ratios? Cureus. 2020;12(8):e10047-e. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erreni M, Mantovani A, Allavena P. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAM) and inflammation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Microenviron. 2011;4(2):141–154. doi: 10.1007/s12307-010-0052-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Waks AG, Winer EP. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(3):288–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oner G, Altintas S, Canturk Z, Tjalma W, Verhoeven Y, Van Berckelaer C, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer-Role of immunology: a systemic review. Breast J. 2020;26(5):995–999. doi: 10.1111/tbj.13696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sjöberg E, Augsten M, Bergh J, Jirström K, Östman A. Expression of the chemokine CXCL14 in the tumour stroma is an independent marker of survival in breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114(10):1117–1124. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khan S, Shukla S, Sinha S, Meeran SM. Role of adipokines and cytokines in obesity-associated breast cancer: therapeutic targets. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24(6):503–513. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Kruijf EM, van Nes JG, van de Velde CJ, Putter H, Smit VT, Liefers GJ, et al. Tumor-stroma ratio in the primary tumor is a prognostic factor in early breast cancer patients, especially in triple-negative carcinoma patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125(3):687–696. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0855-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu SZ, Al-Eryani G, Roden DL, Junankar S, Harvey K, Andersson A, et al. A single-cell and spatially resolved atlas of human breast cancers. Nat Genet. 2021;53(9):1334–1347. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00911-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Beck AH, Espinosa I, Edris B, Li R, Montgomery K, Zhu S, et al. The macrophage colony-stimulating factor 1 response signature in breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(3):778–787. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Koru-Sengul T, Santander AM, Miao F, Sanchez LG, Jorda M, Gluck S, et al. Breast cancers from black women exhibit higher numbers of immunosuppressive macrophages with proliferative activity and of crown-like structures associated with lower survival compared to non-black Latinas and Caucasians. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2016;158(1):113–126. doi: 10.1007/s10549-016-3847-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kinkhabwala A, Herbel C, Pankratz J, Yushchenko DA, Rüberg S, Praveen P, et al. MACSima imaging cyclic staining (MICS) technology reveals combinatorial target pairs for CAR T cell treatment of solid tumors. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1911. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-05841-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.