Abstract

Background

In many countries, national, regional and local inter‐ and intra‐agency collaborations have been introduced to improve health outcomes. Evidence is needed on the effectiveness of locally developed partnerships which target changes in health outcomes and behaviours.

Objectives

To evaluate the effects of interagency collaboration between local health and local government agencies on health outcomes in any population or age group.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Public Health Group Specialised Register, AMED, ASSIA, CENTRAL, CINAHL, DoPHER, EMBASE, ERIC, HMIC, IBSS, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In‐Process, OpenGrey, PsycINFO, Rehabdata, Social Care Online, Social Services Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, TRoPHI and Web of Science from 1966 through to January 2012. 'Snowballing' methods were used, including expert contact, citation tracking, website searching and reference list follow‐up.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), controlled clinical trials (CCTs), controlled before‐and‐after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series (ITS) where the study reported individual health outcomes arising from interagency collaboration between health and local government agencies compared to standard care. Studies were selected independently in duplicate, with no restriction on population subgroup or disease.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently conducted data extraction and assessed risk of bias for each study.

Main results

Sixteen studies were identified (28,212 participants). Only two were considered to be at low risk of bias. Eleven studies contributed data to the meta‐analyses but a narrative synthesis was undertaken for all 16 studies. Six studies examined mental health initiatives, of which one showed health benefit, four showed modest improvement in one or more of the outcomes measured but no clear overall health gain, and one showed no evidence of health gain. Four studies considered lifestyle improvements, of which one showed some limited short‐term improvements, two failed to show health gains for the intervention population, and one showed more unhealthy lifestyle behaviours persisting in the intervention population. Three studies considered chronic disease management and all failed to demonstrate health gains. Three studies considered environmental improvements and adjustments, of which two showed some health improvements and one did not.

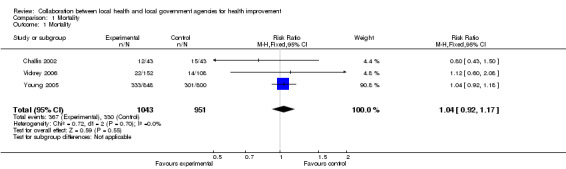

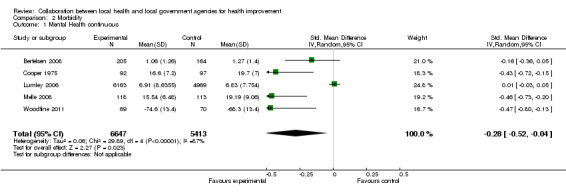

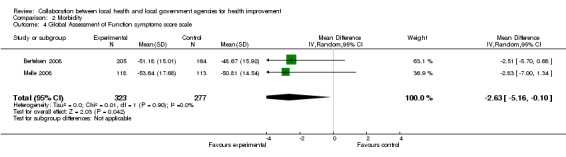

Meta‐analysis of three studies exploring the effect of collaboration on mortality showed no effect (pooled relative risk of 1.04 in favour of control, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.17). Analysis of five studies (with high heterogeneity) looking at the effect of collaboration on mental health resulted in a standardised mean difference of ‐0.28, a small effect favouring the intervention (95% CI ‐0.51 to ‐0.06). From two studies, there was a statistically significant but clinically modest improvement in the global assessment of function symptoms score scale, with a pooled mean difference (on a scale of 1 to 100) of ‐2.63 favouring the intervention (95% CI ‐5.16 to ‐0.10).

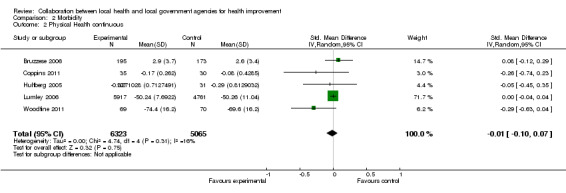

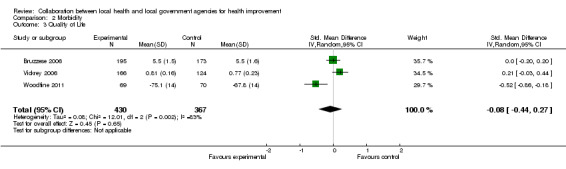

For physical health (6 studies) and quality of life (4 studies) the results were not statistically significant, the standardised mean differences were ‐0.01 (95% CI ‐0.10 to 0.07) and ‐0.08 (95% CI ‐0.44 to 0.27), respectively.

Authors' conclusions

Collaboration between local health and local government is commonly considered best practice. However, the review did not identify any reliable evidence that interagency collaboration, compared to standard services, necessarily leads to health improvement. A few studies identified component benefits but these were not reflected in overall outcome scores and could have resulted from the use of significant additional resources. Although agencies appear enthusiastic about collaboration, difficulties in the primary studies and incomplete implementation of initiatives have prevented the development of a strong evidence base. If these weaknesses are addressed in future studies (for example by providing greater detail on the implementation of programmes; using more robust designs, integrated process evaluations to show how well the partners of the collaboration worked together, and measurement of health outcomes) it could provide a better understanding of what might work and why. It is possible that local collaborative partnerships delivering environmental Interventions may result in health gain but the evidence base for this is very limited.

Evaluations of interagency collaborative arrangements face many challenges. The results demonstrate that collaborative community partnerships can be established to deliver interventions but it is important to agree goals, methods of working, monitoring and evaluation before implementation to protect programme fidelity and increase the potential for effectiveness.

Plain language summary

Collaboration between local health and local government agencies for health improvement

Since the 1980s, national and international health organisations have promoted partnerships between health and other public services at a local level to improve the health of the population. This review looked for evidence on whether collaboration does or does not work when compared to standard services.

Of the two good quality studies identified, one showed no evidence that collaboration between local services improved health and the other showed a modest improvement in some areas. Of the remaining studies, where health benefits were reported these were often modest, inconsistent with other findings and could have been the result of additional funding or resources. Two out of three studies looking at environmental changes reported some health benefits.

These findings show that when comparing local collaborative partnerships between health and government agencies with standard working arrangements, there is generally no difference in health outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Overview of studies.

| Interventions for health improvement in all populations | ||||||

| Outcomes | Intervention and Comparison intervention | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| With comparator | With intervention | |||||

| Mortality | ||||||

| Mortality/health improvement | Study population | RR 1.04 (0.92 to 1.17) | 1994 (3) | |||

| 347 per 1000 | 352 per 1000 | |||||

| Mental Health | ||||||

| Morbidity/health improvement | The mean mental health score in the intervention groups was 0.28 standard deviations lower, a small effect favouring intervention (95% CI: 0.52 to 0.04 lower). | 12060 (5) | Standard Mean Difference ‐0.28 (‐0.52 to ‐0.04) | |||

| Physical Health | ||||||

| Morbidity/health improvement | The mean physical health score in the intervention groups was

0.01 standard deviations lower (95% CI: 0.1 lower to 0.07 higher). |

11388 (5) | Standard Mean Difference ‐0.01 (‐0.1 to 0.07) | |||

| Quality of Life | ||||||

| Morbidity/health improvement | The mean quality of life in the intervention groups was 0.08 standard deviations lower (95% CI 0.44 lower to 0.27 higher). | 797 (3) | Standard Mean Difference ‐0.08 (‐0.44 to 0.27) | |||

| Global Assessment of Function symptoms score | ||||||

| Morbidity/health improvement | The mean global assessment of function symptoms score in the intervention groups was 2.63 lower, a small effect favouring intervention (95% CI: 5.16 to 0.1 lower). | 600 (2) | ||||

Background

The level of health within a given population is affected not only by its health services but also by factors as diverse as environmental, social, cultural and economic influences (Benzeval 1995). These factors are addressed by many publicly funded organisations, including local government and local health authorities. The recognition of the role that social determinants play in the health of the population makes it clear that health cannot be the responsibility of just one agency and, over the last three decades, collaboration has been an increasing focus of health promotion internationally (Marmot 2005).

The need for collaborative working was highlighted in the 1986 Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, produced during the First International Conference on Health Promotion. The Charter stated that “the prerequisites and prospects for health cannot be ensured by the health sector alone. More importantly, health promotion demands coordinated action by all concerned: by governments, by health and other social and economic sectors, by nongovernmental and voluntary organizations, by local authorities, by industry and by the media. People in all walks of life are involved as individuals, families and communities. Professional and social groups and health personnel have a major responsibility to mediate between differing interests in society for the pursuit of health" (WHO 1986).

In 1997 the Jakarta Declaration identified partnerships for health and social development between different sectors as one of its five key priorities. It stressed the need to strengthen existing partnerships and urged the development of new partnerships (Jakarta 1997). These priorities were further highlighted in 2005 when the Bangkok Charter stated that “partnerships, alliances, networks and collaborations provide exciting and rewarding ways of bringing people and organizations together around common goals and joint actions to improve the health of populations" (WHO 2005).

In his report "Fair Society, Healthy Lives" Marmot advised that tackling health inequalities also requires action across the social determinants of health, including education, occupation, employment, income, home and community. He emphasised the key role of local government along with national government departments, the voluntary and private sectors (Marmot 2010).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has documented the success that can be achieved when people, agencies, governments and industry work together to tackle international public health challenges such as smallpox, dehydration, poor mental health, tobacco, AIDS, tuberculosis and outbreaks (WHO 2011). The reports are encouraging but all involved national and international effort. It is not clear if collaborations between local health and local government agencies are equally successful.

In many countries national, regional and local inter‐ and intra‐agency collaborations have been introduced in order to improve health outcomes; often in disadvantaged groups. Agencies involved include primary and secondary healthcare providers, social services, housing, transport, leisure and library services, education and training departments and a range of voluntary bodies. Currently, there are a number of examples where collaborative programmes have been funded at national or state level but delivered locally through interagency partnerships. The WISEWOMAN Project was developed in the USA to prevent or control cardiovascular and other chronic diseases in low income and under‐ or uninsured women. The project comprises 15 state‐based partnerships across a range of agencies working within existing breast and cervical cancer screening programmes to provide screening and lifestyle interventions (CDC 2007). The Victoria Primary Care Partnerships in Australia have drawn together over 800 agencies in 13 partnerships to improve the efficiency and efficacy of health resources and to improve health and wellbeing (Primary 2004; Primary 2005; Primary 2009).

In the United Kingdom, interdepartmental working has been signalled as the way forward since the reorganisation of health and social services that took place during the 1970s (Great Britain 1970; Great Britain 1972; Great Britain 1973). Despite a split in responsibilities, close collaborative working between local health and local government agencies was identified as essential to improve the standards of services being delivered (Laws Statutes 1973a; Laws Statutes 1973b; Laws Statutes 1974). Collaboration was expected to be wide‐ranging, involving the sharing of resources, information, responsibilities and power. Since that time, successive UK governments have created a number of committee and team structures to facilitate partnerships. These have included bodies with statutory functions, such as Joint Commissioning Committees, and others established in accordance with governmental guidance, such as drug and alcohol action teams (Great Britain 1977; Great Britain 1999; HM Government 1995; HM Government 1998). The focus on collaboration has continued with successive governments. For example, the SureStart programme brought together early education, childcare, health and family support with the aim of delivering the best start in life for every child via a mix of universal and targeted programmes for young children and their parents (Sure Start 2004). These bodies address local problems and may have a very different set of priorities from those of their individual partner agencies. The question of whether better health outcomes are achieved as a result of such collaborative arrangements is not clearly answered.

Rationale of the review

In 2000, an unpublished systematic review by the current authors examined the research evidence related to the health effect of collaboration between local health and local government agencies (Wales Office 2001). The review found no evidence that interagency collaborative working necessarily led to improved health. In light of the continued emphasis on local collaborative working, the authors felt it was appropriate to update the review. As in the original review, the focus is on locally‐based initiatives. These could include initiatives arising from a national or state agenda as long as there was local flexibility in how they were developed and implemented. Collaboration at state and national levels often involves coordination of large scale planning and represents a different model of strategic alliances and relationship‐building from partnerships configured at the community level (Padgett 2004). Evidence is needed on the effectiveness of locally‐developed partnerships which target changes in individual health outcomes and behaviours.

Objectives

Primary research objective

To critically assess and summarise the effects of interagency collaboration between local health and local government agencies on health outcomes.

Secondary research objectives

1. To document and describe methods and models of collaboration between local health service agencies and local government authorities.

2. To assess the best methods of collaboration for producing measurable health improvement, if any such methods exist.

3. To develop guidance for future research and research methods if insufficient evidence is identified to address the primary research objective.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Included studies were randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trials (RCTs) including cluster RCTs; controlled clinical trials (CCTs); controlled before‐and‐after studies (CBAs) with a minimum of two study and two control sites; interrupted time series (ITS) with a minimum of three points both before and after the intervention. Studies which were solely economic evaluations were excluded. For included studies, authors were asked for information on partnership or process evaluations related to their collaborative arrangements, and for clarification of study design or missing data as appropriate. Studies or phases of studies where follow‐up rates were less than 60% were excluded. Where studies reported sequential results, they were included up to the point where follow‐up fell below 60%.

Types of participants

All population types and all age groups were included.

Types of interventions

Any interventions of interagency collaboration and partnership between statutory health and local government agencies where the level of partnership between collaborators could be clearly determined (for example, who are the partner agencies and what are their roles within the partnership) and where the interventions were aimed at improving health. For each intervention, comparator care was the mainstream care provided in the area and at the time the intervention was being tested (standard care).

Interventions could be delivered by a wide range of partner agencies but needed to include personnel funded or hosted by a local health agency (for example, doctors, nurses, therapists, midwives, health visitors, dieticians, school nurses, clinical psychologists, health promotion practitioners including public health units) and personnel funded or hosted by a local government agency (for example, social workers, teachers, educational psychologists, housing support workers, library and leisure staff, transport staff, environmental health officers). Multi‐partner collaborations could include education authorities and health agencies, departments for transportation or housing and health agencies, or a mix of these. Interventions where another organisation, for example a voluntary organisation, had been contracted to act on behalf of one of those agencies were also considered for inclusion.

Collaboration was defined as 'two or more parties that pursue an agreed set of goals and work cooperatively toward a set of shared health outcomes', adapted from that used by Gillies (1998) in describing alliances and partnerships for health promotion. Partnerships for health promotion focus on health outcomes rather than specific health promotion goals (Gillies 1998). Local collaboration was judged to have taken place if there was evidence that the partners had agreed local joint working arrangements and shared objectives.

Studies with the following types of interventions were excluded.

Studies which evaluated the effect of collaborative training initiatives between, for example, medical and social work undergraduates.

Studies that included a collaboration designed to enhance one agency's effectiveness in accessing other agencies, as these studies would not be reporting on the outcomes of the collaboration itself but the degree of involvement of the parent agency.

Studies where local government collaborated with the police, probation and prison services or the church but not with a health agency.

Studies where health agencies collaborated with the police, probation and prison services or the church but not with a local government agency.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest were limited to those which were either direct measures of improved health, health status, survival; or lifestyle factors where evidence indicates these have an effect on those direct measures. Studies were included where there were data for any measure of the following endpoints, and where a validated tool was used (see Appendix 1).

Mortality e.g., all‐cause death within period of study; probability of survival.

Morbidity e.g., quality of life measures, incidence rates, measures of symptoms and functionality, birth weight.

Behavioural change was included as a lifestyle change measure when it was known to directly affect levels of health risk or provide health protection e.g., measures of physical activity, smoking status and history, alcohol consumption, dietary change.

Where studies reported more than one relevant outcome, each was captured and reported in narrative form. Where outcomes were provided at multiple follow‐up points, each outcome was reported for the longest available follow‐up period where attrition was 40% or less.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched from January 1966 (or the database start date if later than January 1966) to December 2011 without language, publication or geographical restrictions. The search strategies were based on the strategy developed for Ovid MEDLINE. All search strategies for the electronic databases are provided in Appendix 2.

AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine) 1966 to 2011.

ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts) 1966 to 2011.

CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature) 1966 to 2011.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library) 2012, Issue 1.

Cochrane Public Health Group Specialized Register 25 January 2012.

DoPHER (Database of promoting health effectiveness reviews) 2004 to 2011.

EMBASE (Excerpta Medica) 1980 to 2011.

ERIC (Education Resources Information Center) 1966 to 2011.

HMIC (Health Management Information Consortium) 1979 to 2011.

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) 1979 to 2011.

MEDLINE 1966 to 2011.

MEDLINE In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations 1966 to 2011.

PsycINFO 1966 to 2011.

Rehabdata 1966 to 2011.

OpenGrey (formerly OpenSIGLE) 1980 to 2011.

Social Care Online 1970 to 2011.

Social Services Abstracts 1979 to 2011.

Sociological Abstracts 1996 to 2011.

TRoPHI (The Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions) 2004 to 2011.

Web of Science ‐ Science Citation Index 1979 to 2011.

Web of Science ‐ Social Sciences Citation Index 1979 to 2011.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of included studies and systematic reviews identified in the search were checked for additional citations, and citation tracking of identified RCTs was conducted using Scopus. In addition, experts were contacted directly and via mail lists, and the following websites were searched for publications and unpublished research.

The Association of Public Health Observatories (APHO): http://www.apho.org.uk/.

International Public Health Forum (IPHF): http://www.iphfonline.org/.

Local Government Association: http://www.lga.gov.uk/lga/core/page.do?pageId=1.

NHS Evidence ‐ National Library for Public Health: http://www.library.nhs.uk/publichealth/.

The World Federation of Public Health Associations: http://www.wfpha.org/.

World Health Organization: http://www.who.int/en/.

The UK Public Health Association: http://www.ukpha.org.uk/.

Conference proceedings via the British Library's ZETOC service: http://zetoc.mimas.ac.uk/.

Dissertation and Theses and Index to Theses database: http://proquest.umi.com/login.

Mail lists

Equity, Health & Human Development

EAHIL

Evidence Based Health

LIS Medical

PUBLIC‐HEALTH

PUBLIC‐HEALTH‐INTELLIGENCE

Social Policy

LIS Research Support

Study identification and selection

The titles and abstracts of all search results were reviewed independently by two authors to select potentially relevant studies using pre‐defined inclusion criteria. Studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were independently reviewed in full text by two authors. Where there was a difference of opinion, a third review author also reviewed the paper and a consensus was reached.

Data collection and analysis

Assessment of risk of bias

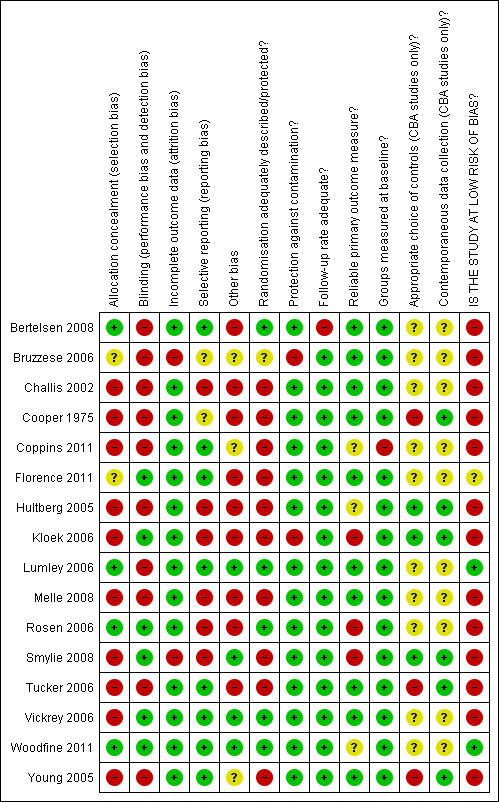

Each eligible study was independently assessed for risk of bias by two review authors using a modified Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group (EPOC) risk of bias assessment (EPOC 2007a) and Chapter 8 (assessing risk of bias) in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008). Questions for RCTs, CCTs, CBAs and ITS study designs were incorporated into a modified version of the EPOC data abstraction form (EPOC 2007b) (see Figure 1, 'Risk of bias summary' for the categories). Where authors disagreed, a third author assessed the study and discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

1.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

All included studies met the minimum standard of the EPOC checklist and were assessed and reported in a ‘Risk of bias' table (Higgins 2008). Where studies reported sequential results, those where follow‐up fell below 60% were excluded.

Studies were defined as having a low risk of bias if they demonstrated the following: an adequate randomisation methodology; a process of allocation concealment; blinding (of participants, investigators and for outcome assessment); non‐selective outcome reporting and a follow‐up response rate greater than 80% (or incomplete outcome data less than 20%) (Burger 2005; Higgins 2008).

Studies that did not fulfil the criteria for demonstrating a low risk of bias were reported as having an unclear or high risk of bias after considering all the items in the checklist.

Data extraction

A modified version of the EPOC data abstraction form was developed. It included questions to capture health equity data based on those used in the draft Cochrane Health Equity Field checklist for review authors (Morris 2007). The revised form was piloted by the authors before use. Data were extracted for all studies that met the quality and inclusion criteria. Two review authors independently completed a form for each study. Data were also extracted for included studies that reported a formal evaluation of the intervention, including the use of any specific partnership assessment tool (PAT) (Dickinson 2006; Hardy 2003; Victorian Health Promotion Foundation 2005).

Where studies reported more than one endpoint per outcome, the primary endpoint identified by study authors was extracted. Where no primary endpoint was identified by the study authors, the measures with the longest follow‐up and with attrition rates under 40% were reported.

Data analysis

Reporting results

Continuous outcomes were reported, where possible, on the original scale. Dichotomous outcomes were presented with odds ratios. All outcome effects were shown with their associated 95% confidence intervals.

Meta‐analysis

Meta‐analyses were conducted where trials reported similar outcomes. Random‐effects models were used for all analyses due to the expected differences in intervention, settings and outcomes. Relative risks were used to summarise dichotomous outcomes and standardised mean differences for continuous outcomes, except where the exact same outcome measure was used in different studies when mean differences were used.

Subgroup analysis

The number of studies with similar outcomes was not deemed sufficient to investigate subgroup analysis by population group or type of intervention.

Asssessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was formally evaluated using the I2 statistic, as well as graphically using the forest plots.

Assessment of publication bias

Funnel plots to assess for publication bias were not presented due to the small number of studies in each meta‐analysis (maximum of five).

Incomplete outcome data (non‐response follow‐up rate)

As stated in the protocol, studies with attrition greater than 40% were excluded.

Summary of findings table

The Table 1 was completed to present brief information about the three categories of health outcomes. It was decided that the inclusion of evidence quality for each group of outcomes (based on the GRADE approach) was not feasible given the heterogeneity and range of study designs.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

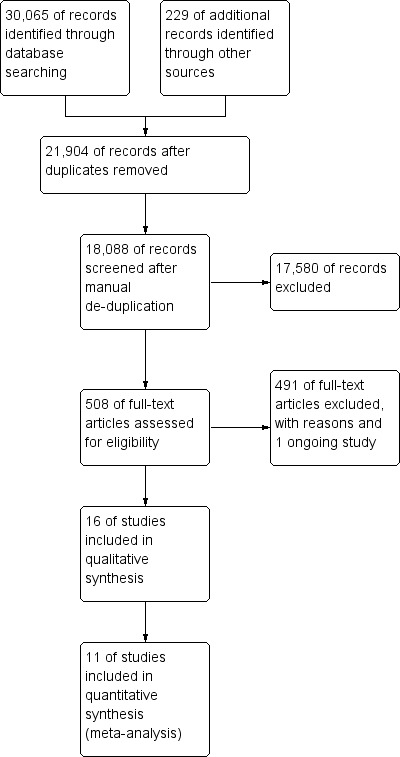

Electronic searches yielded 19,064 references in the original search and an additional 11,001 references in the search for the updated review; 416 full‐text articles were assessed for eligibility from the original search and 92 from the updated search. Sixteen studies met the inclusion criteria for the narrative synthesis, of which 11 contributed data to meta‐analyses.

Excluded studies

Four hundred and ninety‐one studies were excluded. Most were excluded because of the nature of the collaboration, for example, partners coming from either health or local government agencies but not both, or prescriptive collaborations set up under national or international programmes. Other studies did not report relevant health outcomes or had inappropriate study designs. The Characteristics of excluded studies table lists the 491 studies with reasons for exclusion.

Ongoing studies

One ongoing study was identified (see Characteristics of ongoing studies).

| Lead author | Study design | Population | Intervention | Health outcomes |

| Bertelsen 2008 | RCT | 547 patients with first diagnosis within schizophrenia spectrum in Copenhagen and Aarhus, Denmark | The lead agency was mental health. Collaboration was between psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, vocational therapists, social workers, family therapists working in multidisciplinary teams following agreed protocols. They delivered an intensive early intervention programme of Assertive Community Treatment, family treatment and social skills training. |

Primary health outcomes: Symptoms on the Scale for Assessment of Psychotic Symptoms (SAPS), Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) and the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores for symptoms and for function |

| Bruzzese 2006 | Cluster RCT | 591 children in kindergarten to Grade 5, New York City, USA | The lead agency was the Local Education Authority. Collaboration was between school nurses, community and primary care physicians, school educators, public health assistants and university staff. They established Preventive Care Networks for each intervention school and delivered training for health and educational professionals. |

Primary health outcomes: Asthma symptoms in past 2 weeks and past 6 months, number of nights woken in past 2 weeks and past 6 months Number of days restricted activity in past 2 weeks and past 6 months Paediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire (PACQLQ) |

| Challis 2002 | CCT | 95 elderly adults with dementia in Lewisham, UK | The lead agency was community mental health. Collaboration was between social services case managers and mental health teams. They delivered an intensive case management scheme with structured care plans. Case managers had protected case loads and control of a devolved budget. They had access to health and social care resources. |

No primary outcomes were stated Health outcomes included: Depression measured by the Comprehensive Assessment and Referral Evaluation (CARE) schedule, disability measured through Clifton Assessment Procedures for the Elderly (CAPE) behaviour rating scale Physical disability, social disturbance, communication disorder and apathy measured through CAPE Patients' overall level of risk Carers' health assessed for strain and malaise |

| Cooper 1975 | CCT | 189 patients with chronic neurotic illness in primary care practice in a metropolitan area, UK | The lead agency was primary care. Collaboration was between general practitioners and health visitors in a primary care practice, a social worker and research psychiatrists. They established multidisciplinary coordination and evaluation of patients' care through fortnightly meetings. |

Primary health outcomes: Change in psychiatric rating (scale now known as GHQ 30) |

|

Coppins 2011 NEW |

RCT | 65 participants aged 6 to 14 years with a BMI above the 91st centile, living in Jersey, UK |

The lead agency was the local community health service. Collaboration was between a dietician, physical activity health promotion officer, educational and clinical psychologists, physical activity instructors. They ran workshops and physical activity sessions in school settings. Siblings aged 6 to 14 years and parents/guardians were encouraged to participate. |

Change in BMI standard deviation score. Change in weight, waist circumference, sum of skinfolds % body fat |

|

Florence 2011 NEW |

ITS | Resident populations and visitors to Cardiff and selected control cities in the UK | The lead agency was health. Collaboration was between city government (education, transport, licensing regulators) police, an emergency department consultant and an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, ambulance service and local licensees. They worked together in the Cardiff Violence Prevention Programme to share data between agencies and use the information for violence prevention through targeted policing and other strategies. |

Hospital admissions after violence, police recorded woundings, police recorded common assaults |

| Hultberg 2005 | CBA | 138 patients with musculoskeletal disorder in Goteburg, Sweden | The lead agency was primary care. Collaboration was between health centre physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers and social insurance officers working in co‐financed multidisciplinary teams based in the health centres. They had access to a joint budget provided by one common administrative body. They attended weekly team meetings to discuss and intensify the rehabilitation of individual patients. |

Primary health outcomes: Pain level measured by the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) Health‐related quality of life measured through EuroQol 5 dimensions instrument (EQ‐5D) |

| Kloek 2006 | CBA | 2781 residents in Eindhoven, Netherlands | The lead agency was municipal health. Collaboration consisted of multi‐agency coalitions between municipal health services and representatives from social work, social welfare, city development department, neighbourhood residents organisation, general practice and researchers. They assessed neighbourhood health needs, developed action plans to improve health‐related behaviour and delivered a range of activities in schools, small community groups and public events. |

Primary outcome was to improve health‐related behaviours, measured by impact on fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption |

| Lumley 2006 | Cluster RCT |

11,305 women giving birth in Victoria, Australia | The lead agency was local authority. Collaboration in each intervention area consisted of key stakeholders from local government, GPs, Maternal and Child Health nurses, community and consumer organisations and a community development officer forming local steering committees to deliver a Program of Resources, Information and Support for Mothers (PRISM). Interventions included components for primary care and for local community services. Clinical audits were conducted. |

Primary health outcome: EPDS, a 10‐item scale for use in the postnatal period to identify probable depression SF36 physical and mental component scores |

| Melle 2008 | CCT | 281 patients with first episode psychosis in four catchment areas in Norway and Denmark | The lead agency was mental health. Collaboration was between mental health clinicians, nurses, psychologists, GPs, school staff and social workers. Specialist integrated teams delivered an Early Detection Programme for rapid assessment of possible first episode psychosis patients and community information campaigns in schools and the local media to raise awareness of mental health issues. |

Primary outcome was the duration of untreated first episode psychosis Secondary health outcomes included symptom levels assessed through the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores and level of functioning through the Global Assessment of Functioning scores |

|

Rosen 2006 NEW |

Cluster RCT randomized at the level of preschool |

40 public religious and secular preschools with 1029 children aged 3 and 4 years old. Additional support for children from 469 families who were in the intervention preschools. Set in Jerusalem region, Israel |

The lead agency was public health. Collaboration was between public health officers, Ministry of Education officials, teachers, preschools, school nurses, doctors and educational experts. They delivered an intervention consisting of educational lectures and resources, play materials, video and puppetry, along with ensuring environmental facilities were adequate to support good hand hygiene. The home component consisted of educational resources sent to families, chosen by computer‐generated random numbers, of children attending the intervention preschools. Control preschools had no intervention until the study was over. Home component control families received an educational pack on toothbrushing. |

Illness‐related absenteeism, handwashing behaviour before lunch and after using the bathroom |

|

Smylie 2008 NEW |

CBA | 240 Grade Nine students in six public schools in Windsor‐Essex County, Ontario, Canada | The lead agency was public health. Collaboration was between public health nurses, health promoters, social workers, teachers, a teen mother, a teen father and an HIV positive individual. They delivered a five session class‐based learning programme, a newsletter and workshops to help parents communicate effectively on sexual health issues with their children. |

Forty‐six items on knowledge, birth control attitudes, contraceptive agency (the degree to which students felt comfortable accessing and using birth control), communication, awareness of sexual response, sex role attitudes and sexual interaction values |

| Tucker 2006 | CBA | 8703 secondary school children, median age 14 years 6 months, in Lothian and Grampian regions, UK | The lead agency was the local health board. Collaboration was between health, education and the voluntary sector working in 10 schools. As part of the Healthy Respect programme, they established a partnership to implement the SHARE (Sexual Health and Relationships Education) project of multidisciplinary staff training, multidisciplinary delivery in classroom lessons and drop‐in sexual health services. |

Primary health outcomes: Self‐reported sexual intercourse at <16 years, and knowledge, attitudes and intentions about sexually transmitted diseases and condom use |

| Vickrey 2006 | Cluster RCT |

408 dementia patient and carer dyads, Southern California, USA | The lead agency was primary care. Collaboration was between physicians, leaders from community agencies, a community caregiver, the researchers and care managers. They formed a steering committee to identify existing guidelines as care goals. They introduced a disease management programme promoting care guidelines, care coordination and referral protocols. Community agency care managers and healthcare care managers received the same formal education and training programme. Health and community agency staff collaborated to provide support to patients with dementia and their carers. |

Primary outcome, extent of adherence to guidelines, was not relevant to this review Secondary health outcomes: Health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) for patients and carers |

|

Woodfine 2011 NEW |

RCT | 192 asthmatic children aged 5‐14 years, who had been in receipt of ≥3 prescriptions of corticosteroid inhalers in previous 12 months. Set in Wrexham, UK |

The lead agency was public health. The collaborators were local public health, primary care, Wrexham County Borough Council and academia. Vent‐Axia HR200XL ventilation systems were installed in the roof space and improvement/replacement of central heating system was undertaken if required. |

Primary: Parental assessment of the child's asthma‐specific quality of life (PedQL asthma module) 4 and 12 months after randomisation Secondary: General health‐related quality of life (PedQL core module), school attendance and the use of health care including medication Cost effectiveness of intervention |

| Young 2005 | CCT | 1648 vulnerable elderly patients in the Leeds area, UK | The lead agency was the health authority. Collaboration was between Leeds Health Authority and Leeds City Council. They developed a commissioning framework to provide support and rehabilitation to older patients following a health crisis at home or in hospital. A multi‐agency joint care management team commissioned care from a multidisciplinary Intermediate Care Team comprising nurses, therapists and social services staff. |

Primary health outcome: Independence measured by Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Index |

Table 1. Outlines of included studies

Included studies

Characteristics of studies

Sixteen studies were included in the narrative synthesis, of which seven were RCTs or cluster RCTs (Bertelsen 2008; Bruzzese 2006; Coppins 2011; Lumley 2006; Rosen 2006; Vickrey 2006; Woodfine 2011), four studies were CCTs (Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Melle 2008; Young 2005), four studies were CBAs (Hultberg 2005; Kloek 2006; Smylie 2008; Tucker 2006) and one was an ITS (Florence 2011). Eleven were included in the meta‐analyses (Figure 2). A brief outline of each included study can be found in Table 1. More details are presented in the 'Characteristics of included studies' table for each study (see Characteristics of included studies).

2.

Study flow diagram.

Of the 16 studies meeting the inclusion criteria (Figure 1), 15 reported information on 28,212 participants although not all participants contributed outcome data as many participants were lost to follow‐up. One study monitored rates of violence in a population of 324,800 (Florence 2011). The largest number of participants (11,305) was from a study (Lumley 2006) that aimed to reduce depression and improve the physical health of mothers six months after giving birth. The next largest study (Tucker 2006) surveyed 8703 school children in two different cohorts.

Seven studies were conducted in the UK (Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Coppins 2011; Florence 2011; Tucker 2006; Woodfine 2011; Young 2005), one in Denmark (Bertelsen 2008), one in Sweden (Hultberg 2005), one in both Norway and Denmark (Melle 2008), one in the Netherlands (Kloek 2006), two in US states (Bruzzese 2006; Vickrey 2006), one in Canada (Smylie 2008), one in Israel (Rosen 2006) and one in Australia (Lumley 2006). While reports on interventions in low or middle income countries were identified by the search strategy, many of them reflected work by international aid agencies delivering internationally agreed programmes with local partners rather than by local partnerships working to locally agreed goals.

Eight studies were delivered through community and primary care services (Bertelsen 2008; Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Hultberg 2005; Lumley 2006; Vickrey 2006; Woodfine 2011; Young 2005), five were delivered in schools (Bruzzese 2006; Coppins 2011; Rosen 2006; Smylie 2008; Tucker 2006) and three were set in the wider community (Florence 2011; Kloek 2006; Melle 2008). No studies were based in hospitals but two (Bertelsen 2008; Young 2005) recruited participants from hospital‐based services.

Bertelsen 2008, Melle 2008, Rosen 2006, Tucker 2006, Woodfine 2011 and Young 2005 succeeded in recruiting the sample sizes required by their power calculations. Lumley 2006 identified that they were not recruiting enough participants and extended the recruitment period until the required number had been recruited to the intervention group though not to the control group. Vickrey 2006 aimed to recruit 438 dyads but failed to achieve this. Hultberg 2005 did not conduct a power calculation but aimed to recruit 450 patients, which they failed to achieve despite extending the recruitment period by eight months. The remaining studies did not provide power calculations and did not state their desired sample size (Bruzzese 2006; Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Coppins 2011; Florence 2011; Kloek 2006; Smylie 2008).

Primary outcomes

Few studies reported one primary outcome, although several had one overarching goal for which there was a range of measures. Coppins 2011 aimed to produce a change in the body mass index standard deviation score (BMI SDS) (or BMI z‐score), a measure demonstrating the deviation of children's BMI from the average of a child of the same age and sex. Kloek 2006 aimed to improve health‐related behaviours measured through self‐reported diet, exercise, smoking and alcohol behaviours. Melle 2008 aimed to reduce the duration of untreated first episode psychosis in order to improve mental health outcomes in the longer term. The primary outcome for Vickrey 2006 was adherence to care guidelines on the understanding that this should improve quality of life for dementia patients and their carers. Young 2005 aimed to protect the independence of vulnerable elderly patients in order to minimise hospitalisations and institutionalisation. The primary outcome for Rosen 2006 was a reduction in illness absenteeism but reliable data were hard to collect. Smylie 2008 wanted to support actual change in sexual behaviour in under 16s but it was thought inappropriate to ask school students about this so proxies relating to knowledge, attitudes, communication and self‐awareness were used. All studies measured multiple outcomes and Bruzzese 2006, Challis 2002 and Vickrey 2006 included measures of carer health. The primary outcome for Bertelsen 2008 was stated to be at five years but at that point follow‐up rates for symptom and function assessments were below 60% in both arms. Follow‐up rates at two years were above 60%, unequal in the two arms, and assessment was not blinded.

Characteristics of participants

Seven studies delivered interventions to individual participants (Bertelsen 2008; Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Coppins 2011; Hultberg 2005; Woodfine 2011; Young 2005). Six studies delivered interventions to populations defined by: area of residence (Kloek 2006; Melle 2008); school attended (Rosen 2006; Smylie 2008; Tucker 2006); or registered primary care clinic (Vickrey 2006). Bruzzese 2006, Florence 2011 and Lumley 2006 used a variety of interventions, some aimed at the general population and others at individuals. Two studies targeted deprived communities (Bruzzese 2006; Kloek 2006) and all but five studies (Coppins 2011; Melle 2008; Smylie 2008; Woodfine 2011; Young 2005) reported measures of deprivation. The targets of the educational programmes and public information campaigns in Melle 2008 were school children and households in the intervention areas. However, the target group to benefit were people with first episode psychosis who, if the programme was successful, would have assessment, diagnosis and treatment earlier in the course of their illness due to increased awareness and support in their community. In Kloek 2006 the programmes were delivered to children as well as adults but the outcomes were only measured in adults. Bruzzese 2006, Challis 2002 and Vickrey 2006 included measures to support carers.

Four of the five studies identified in the 2012 update were targeted at children (Coppins 2011; Rosen 2006; Smylie 2008; Woodfine 2011). The fifth study (Florence 2011) was aimed at the population of a city, particularly but not solely people making use of a city centre's night‐time facilities.

Characteristics of interventions

Collaboration was delivered through a range of multidisciplinary teams working to agreed programmes. Partners included primary and secondary healthcare workers, public health officers, health promotion officers, local authority staff including social workers and care staff, teaching professionals, environmental health officers, sports and leisure officers, police and voluntary agencies.

Seven studies reported on interventions to improve the care or treatment of patients (Bertelsen 2008; Bruzzese 2006; Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Hultberg 2005; Vickrey 2006; Young 2005) through multidisciplinary team work. Nine studies reported health education, health promotion or disease prevention initiatives (Coppins 2011; Florence 2011; Kloek 2006; Lumley 2006; Melle 2008; Rosen 2006; Smylie 2008; Tucker 2006; Woodfine 2011). Examples of health education and promotion included Melle 2008, which aimed to raise community awareness of psychosis to encourage early referrals and so decrease the duration of untreated psychosis; and Kloek 2006, which ran nutrition projects in primary schools, quit smoking courses and large annual community events related to health along with other activities such as walking events.

Six studies related to mental health initiatives (Bertelsen 2008; Challis 2002; Cooper 1975; Lumley 2006; Melle 2008; Vickrey 2006), including one focused on preventing depression and improving the physical health of mothers in the first six months after giving birth (Lumley 2006). Of the remaining five studies, two related to chronic disease management (Bruzzese 2006; Hultberg 2005), two were aimed at encouraging healthy lifestyles (Kloek 2006; Tucker 2006) and one was aimed at improving support for the frail elderly (Young 2005).

Defined at‐risk populations were targeted in five studies, two in children (Bruzzese 2006; Tucker 2006) and three in the elderly (Challis 2002 ; Vickrey 2006; Young 2005).

One study followed longitudinal incident rates of violent assault in a defined population (Florence 2011).

Evaluation of partnerships and processes

Some authors included comments on the extent to which participants had taken part in or received interventions. For instance Smylie 2008 captured how many classroom sessions students had attended. Of the 10 authors who responded to requests for information on partnership evaluations, six studies had been formally evaluated (Challis 2002; Kloek 2006; Lumley 2006; Rosen 2006; Tucker 2006; Vickrey 2006) although data were not available for the Lumley 2006 intervention. Additionally, for Woodfine 2011 a cost effectiveness analysis was performed. However, many authors had not conducted partnership evaluations.

Risk of bias in included studies

Of the seven RCTs, only two were considered to be at low risk of bias (Lumley 2006; Woodfine 2011) and one was at unclear risk of bias (Vickrey 2006). Of the non‐randomised studies, Melle 2008 and Florence 2011 were judged to be at unclear risk of bias and all the others were deemed to be at high risk of bias.

For detailed information on the risk of bias of individual studies see the risk of bias tables for each study and the risk of bias summary (Figure 1).

Adequate randomisation methodology

Most RCTs and cluster RCTs reported appropriate methods for randomisation. Bertelsen 2008, Rosen 2006, Vickrey 2006 and Woodfine 2011 used various independent methods to generate random allocation. Lumley 2006 generated a random set of eight matched pairs of areas from a stratified set of 21 eligible areas. Bruzzese 2006 and Coppins 2011 did not give a description of how participants were randomised.

Contamination of the control group

Controlling conditions in population or area level intervention studies can be hard. People are free to move between areas and there may be family or social ties between intervention and control arms which are unknown to the researchers. Three studies reported on probable contamination in the control groups of their studies. One study appeared to have been conducted to a high standard (Bruzzese 2006) but a similar intervention was introduced to the wider community, including the whole study population, part way through the study thereby contaminating the control group and reducing the potential to demonstrate a true effect from the intervention. Lumley 2006 reported that they had looked for evidence of contamination in the control areas and found that some members of the control group had received the leaflets designed for the intervention group. They concluded that as the overall intervention consisted of many additional components this was unlikely to have led to bias in the results. Kloek 2006 identified low levels of contamination in control neighbourhoods, which was to be expected as they were in the same city as the intervention neighbourhoods. For the remaining studies contamination of the control group appeared unlikely.

Allocation concealment

Based on the author report, only four studies were able to conceal allocation (Bertelsen 2008; Florence 2011; Lumley 2006; Rosen 2006).

Selective outcome reporting

Selective outcome reporting appeared to be more common in the non‐randomised studies. Some studies reported follow‐up results linked to previous work. For example, Melle 2008 reported two year follow‐up results on a study that had started recruiting participants eight to 10 years previously and which had been extensively reported by other authors. There were differences in the way the various reports described the same study, making it difficult to understand exactly what had been done and raising the possibility that some data were not being fully reported. Challis 2002 reported different sets of outcomes at different follow‐up periods. Smylie 2008 captured full follow‐up data on 22 students who had not attended any sexual health sessions and omitted to include these results in their analysis. It was not possible to establish whether Cooper 1975 had used selective outcome reporting because a protocol was not available.

Level of blinding

We assessed blinding of participants and researchers. The participants and researchers in population or public health Interventions often cannot be blinded because there are clear differences between receiving the intervention and not. Rosen 2006 used an interesting technique to blind families as they gave the intervention families information and equipment related to handwashing and for the control families they gave information on toothbrushing. Most studies were unable to achieve blinding of outcome assessment. Of the studies that reported blinding, Vickrey 2006 used a variety of ways to achieve as high a level of blinding as possible. Participants were blinded at baseline and they were not reminded of status at follow‐up. Data abstractors were blinded. Carers were blinded at the baseline survey. Bruzzese 2006, Lumley 2006 and Smylie 2008 did not use blinding in assessments but the outcomes were judged unlikely to have been influenced by this. In Cooper 1975 there was no evidence to suggest assessment had been blind, although assessment of individuals was not performed by the psychiatrist involved in their care.

Incomplete outcome data

Only studies where outcome data appeared to be adequately accounted for were included in this review. Outcome data available for less than 60% of participants at any time‐point were excluded.

Unit of analysis errors

Four studies employed cluster randomisation (Bruzzese 2006; Lumley 2006; Rosen 2006; Vickrey 2006). All used methods to account for the clustering and none of these studies were re‐analysed. Bruzzese 2006 used Generalised Estimating Equations (GEE) models to account for clustering. Lumley 2006 used a multilevel model reporting that the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.0012. Rosen 2006 used mixed linear models and reported an ICC of 0.06 for overall absenteeism and 0.07 for illness absenteeism. Vickrey 2006 used multilevel modelling to account for clustering, however this study contributed uncorrected dichotomous information to the mortality meta‐analysis. Using the design effect of 1.57 reported in their sample size calculation (based on an ICC of 0.03) the sample size of both control and intervention groups were scaled down from 238 and 170 to 152 and 108 for the intervention and control groups respectively. Numbers of events were selected that produced proportions of events closest to the observed proportions. The effect of this design effect scaling was very small.

Interrupted time series (ITS) studies

Only one interrupted time series study (Florence 2011) was identified and this has been reported separately.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs)

Lumley 2006 (a cluster RCT with low risk of bias) conducted a community randomized trial using the PRISM (Program of Resources, Information and Support for Mothers) approach to reduce depression and improve women's physical health after giving birth. Power calculations suggested that questionnaires needed to be sent to 9600 women in each arm and, as birth rates were lower than anticipated, data collection was extended to generate the required sample size. A total of 6248 women out of 10,144 women (61.6%) in the intervention arm and 5057 out of 8411 women (60.1%) in the control arm completed postal questionnaires six months after giving birth. The intervention and control groups appeared comparable at baseline. The mean Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Score (EPDS) was 6.91 (SE adjusted (adj) 0.11) in 6163 women in the intervention communities and 6.83 (SE adj 0.11) in 4969 women in the control communities (P = 0.61, mean difference 0.08, SE adj 0.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.25 to 0.40). Mean SF‐36 physical component scores were 50.24 (SE adj 0.10) for 5917 women in the intervention communities and 50.26 (SE adj 0.16) for 4761 women in the control communities (P = 0.91, mean difference ‐0.02, SEadj 0.19, 95% CI ‐0.43 to 0.39). Mean SF‐36 mental component scores were 47.58 (SE adj 0.15) in 5917 women in the intervention communities and 47.91 (SE adj 0.19) in 4761 women in the control communities (P = 0.20, mean difference ‐0.32, SE adj 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.83 to 0.18). None of these findings were significant. There was no difference between intervention and control communities in the mothers' rating of partners' practical and emotional support, with mean scores derived from a set of six questions being 6.9 in both groups.

Evaluation of the intervention

An interorganisational analysis has being conducted. It has not yet been published and a copy could not be obtained.

Summary: there were no significant differences between the two groups in any of the measures at six‐months follow‐up.

Woodfine 2011 (an RCT with a low risk of bias) aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of tailored packages of home improvements, providing adequate heating and ventilation in order to reduce mould spores, for children with moderate or severe asthma. They aimed to recruit 200 children to yield 80% power to detect, at 5% significance level, a change in asthma‐specific quality of life of at least 0.4 of the standard deviation of the parent‐completed asthma‐specific module of PedsQL, a validated quality of life measure for children.

At month 12 (11 months post‐intervention): 169 (88%) responded (intervention group (I) = 88; control group (C) = 89). The mean difference in PedsQL asthma scale adjusted for baseline was 7.1 (95% CI 2.8 to 11.4); standardised effect size 0.42. There were no significant differences in physical scale (4.5, 95% CI ‐0.2 to 9.1; standardised effect size 0.22) or psychosocial functioning (2.2, 95% CI ‐1.9 to 6.4; standardised effect size 0.11). The overall psychosocial scale at 12 months was 74.6 in the intervention group (n = 69) and 68.3 in the control group (n = 70) (mean adjusted difference 2.7, 95% CI ‐1.8 to 7.2) favouring the intervention arm. There was no significant difference in parent‐reported school absence over 12 months: mean 9.2 days in intervention group versus 13.2 days in control group (Mann‐Whitney U test P = 0.091); and mean 3.9 days in intervention group versus 6.4 days in control group for asthma‐related absences (Mann‐Whitney U test P = 0.053).

There was no significant difference in healthcare costs over 12 months between groups. The authors reported a shift from ‘severe’ to ‘moderate’ asthma in 17% of the intervention group and 3% of the control group.

Cost effectiveness of the intervention: the mean cost of modifications was £1718 per child treated or £12,300 per child shifted from ‘severe’ to ‘moderate’ asthma. ‘Bootstrapping’ gave an incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £234 per point improvement on the 100‐point PedsQL™ asthma‐specific scale (95% CI £140 to £590). The ICER fell to £165 (95% CI £84 to £424) for children with ‘severe’ asthma. The authors concluded that the intervention had been cost effective.

Evaluation of the intervention

The authors did not undertake a formal evaluation, although some information on the delivery of the programme was provided in a cost‐effectiveness analysis.

Summary: the impact of asthma on childrens' lives, as measured by the asthma subscale of the parent‐completed PedsQL, was significantly lessened in the intervention group 11 months after home modification. No significant improvement was seen in overall physical or psychosocial quality of life at 12 months. School absences were not statistically significantly different between groups.

Bertelsen 2008 (an RCT with high risk of bias) aimed to determine the long‐term effects of an intensive early‐intervention programme for first‐episode psychotic patients. They assessed 547 participants at baseline before randomization and the two groups appeared well matched and representative of the client group. At two years the independent assessment was unblinded and at five years the independent assessment was blinded. (Note: the mean differences are based on a repeated model to impute missing data.)

The follow‐up rate at two years was 75% in the intervention group (n = 205) and 60% in the control group (n = 164). The mean symptom score on the Scale for Assessment of Psychotic Symptoms (SAPS) was 1.06 (SD 1.26) in the intervention group and 1.27 (SD 1.40) in the control group, estimated mean difference ‐0.32 (95% CI ‐0.58 to ‐0.06, P = 0.02). The mean symptom score on the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) was 1.41 (SD 1.15) in the intervention group and 1.82 (SD 1.23) in the control group, estimated mean difference ‐0.45 (95% CI ‐0.67 to ‐0.22, P < 0.001). The mean Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) symptom score was 51.18 (SD 15.01) in the intervention group and 48.67 (SD 15.92) in the control group, estimated mean difference 2.45 (95% CI ‐0.32 to 5.22, P = 0.08). The mean GAF function score was 55.16 (SD 15.15) in the intervention group and 51.13 (SD 15.92) in the control group, estimated mean difference 3.12 (95% CI 0.37 to 5.88, P = 0.03).

The primary endpoint of the study was at five years but as follow‐up was below 60%, with 56% in the intervention group and 57% in the control group, and below 60% in both arms when deaths were taken into account, it is not reported here.

Evaluation of the intervention

No process evaluation has been identified.

Summary: interim results at two‐year unblinded follow‐up showed that the SAPS and SANS symptom scores and the GAF score for function were statistically significantly improved in the intervention group although the size of these effects was very modest (‐0.32, ‐0.45 for SAPS and SANS respectively, both on a 6‐point scale; and 2.45 on the GAF, a 100‐point scale). There was no difference in the GAF score for symptoms between the two groups.

Vickrey 2006 (a cluster RCT with medium risk of bias) tested the effectiveness of a dementia guideline‐based disease management programme on quality of care and outcomes for patients with dementia. Primary outcomes related to the level of adherence to 23 guidelines and were not relevant to this review. Secondary outcomes were assessed through a caregiver survey. At baseline assessment the intervention and control groups did not differ in patient and caregiver characteristics. At 18‐months follow‐up the mean patient health‐related quality of life score had decreased from 0.17 (SD 0.30) to 0.10 (SD 0.30) in the intervention group and from 0.16 (SD 0.32) to 0.03 (SD 0.29) in the control group. The adjusted analysis for intervention versus control group between‐group difference was 0.06 (95% CI 0.005 to 0.11, P = 0.034). Caregiver health‐related quality of life, measured using EuroQol‐5D, changed from a mean of 0.83 (SD 0.17) at baseline to 0.81 (SD 0.16) at 18‐months follow‐up for carers of patients in the intervention group and from 0.80 (SD 0.22) at baseline to 0.77 (SD 0.23) at 18‐month follow‐up for carers of patients in the control group. The adjusted analysis for intervention versus control between‐group difference was 0.02 (95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.06, P = 0.127).

By the 12‐month follow‐up 34 out of 238 patients had died in the intervention group and 20 out of 170 patients had died in the control group.

Evaluation of the intervention

All care management communications and encounters with the participants were recorded on an electronic database. Subsequent analysis of the impact of the three agencies demonstrated that contact with healthcare organisation care managers was associated with improved quality. Further, statistically and clinically significant incremental gains in quality were seen with the addition of the other provider types (community agency care managers and healthcare organisation primary care providers). It was noted that the three groups of staff may have recorded their interventions differently. Factors associated with accepting case management were also analysed and were found to include cohabitation of the caregiver, lesser severity of dementia and higher patient co‐morbidity.

Summary: at 18‐month follow‐up the caregivers reported that quality of life had deteriorated for the intervention and control groups but the intervention group had a better health‐related quality of life score than the control group. There was no difference in the health‐related quality of life for the carers of the two groups.

Bruzzese 2006 (a cluster RCT with high risk of bias) established a preventive network of school nurses, teachers and primary care providers to improve elementary school childrens' control of asthma. Randomization was at the school level. Intervention and control groups were assessed at baseline and found to be comparable apart from the control group children waking more nights due to asthma in the previous two weeks. For every 50 children known by the school nurse to have asthma, the network identified another 25 children with an asthma diagnosis and another 20 children with symptoms suggestive of asthma. Follow‐up at two years by telephone interview of caregivers was 64% in the intervention group (n = 195) and 61% in the control group (n = 173). The mean number of days with symptoms in the past two weeks was 2.9 (SD 3.7) in the intervention group and 2.6 (SD 3.4) in the control group; mean number of days with symptoms in the last six months was 32.1 (SD 44.9) in the intervention group and 32.0 (SD 45.6) in the control group. The mean number of nights woken in the past two weeks was 1.6 (SD 2.6) in the intervention group and 2.2 (SD 3.4) in the control group; mean number of nights woken in the last six months was 26.3 (SD 40.6) in the intervention group and 26.8 (SD 42.3) in the control group. The mean number of days with restricted activity in the past two weeks was 1.5 (SD 2.45) in the intervention group and 1.5 (SD 2.8) in the control group; mean number of days with restricted activity in the past six months was 25.4 (SD 41.3) in the intervention group and 23.6 (SD 41.0) in the control group. Caregivers' quality of life assessed using the Paediatric Asthma Caregiver's Quality of Life Questionnaire was mean 5.5 (SD 1.5) in the intervention group and 5.5 (SD 1.6) in the control group. None of these outcomes were significantly different.

Evaluation of the intervention

No process evaluation has been carried out.

Summary: the network identified more children with diagnosed and undiagnosed asthma than were known to the school nurses. There were no differences in outcomes between the children in the two groups or between the two groups of carers at two‐year follow‐up.

Coppins 2011 (an RCT with a high risk of bias) aimed to treat overweight and obese children through a multi‐component family focused education package. Workshops were conducted on healthy eating, physical activity, psychological well‐being and behaviour change, including reducing sedentary activity; and offered regular physical activity sessions for obese and overweight children aged 6 to 14 years, their siblings aged 6 to 14 years, and their parents. Outcomes were measured at six‐month intervals for 24 months but the intervention was given to the intervention‐control group in the first 12 months and to the control‐intervention group in the second 12 months, so the point of comparison was taken to be at 12 months for the purpose of this review. There were some differences between the groups at baseline with the intervention group being on average 16.5 months older than the control group.

The primary outcome was change in BMI SDS. At 12 months the change in the intervention group BMI SDS was ‐0.17 (95% CI ‐0.26 to ‐0.08) and the adjusted difference was ‐0.13 (95% CI ‐0.26 to ‐0.008). The change for the control group BMI SDS was ‐0.08 (95% CI ‐0.24 to 0.07) and the adjusted difference was ‐0.14 (95% CI 0.28 to ‐0.001). The mean difference between the intervention and control groups was ‐0.09 (95% CI ‐0.26 to 0.09, F = 0.99, P = 0.32).

Evaluation of the intervention

The corresponding author reported that no information relating to process or partnership evaluations has been published.

Summary: the multi‐component intervention to help overweight and obese children adopt healthier lifestyles and normalise their BMI was not effective compared to the wait‐list control group.

Rosen 2006 (an RCT with a high risk of bias) evaluated the effects of a comprehensive hand hygiene programme, including improving environmental facilities where indicated, on preschool children aged 3 and 4 years in 40 preschools (20 intervention, 20 control). They also nested an RCT within the intervention group to test a home education component. Sample size was calculated to detect a 25% drop in illness absenteeism with a power of 80% and a two‐sided alpha level of 0.05, given a control group illness absenteeism rate of 6% per child day (36 preschools, rounded up to 40). A planned 60‐day study period was extended to 66 days during the trial. Sample size for the home intervention was similarly calculated to detect an illness absenteeism reduction from 4.5% to 3.0%. The required sample size was 204 families per arm. The main outcome measures were overall absenteeism and illness absenteeism from preschool. For the purposes of this review the outcome measure of illness absence was used. The researchers also measured handwashing behaviours.

The average per day percentage of illness absenteeism was 3.40 days (489 children) and 3.11 days (540 children) for the intervention and control preschools respectively: intraclass correlation coefficient 0.0747, between day correlation 0.0417, adjusted RR of 1.00 (95% CI 0.81 to 1.32, P = 0.97). For the home component, illness absenteeism was 2.92 (n = 237) in the intervention group and 3.04 (n = 232) in the control group, adjusted RR of 0.94 (95% CI 0.76 to 1.23, P = 0.57).

Evaluation of the intervention

The corresponding author reported a detailed survey of the teachers', parents' and childrens' reactions to the programme and there were comments made on the activity of the partners delivering the intervention. The feedback was extremely positive and other schools have taken up the programme several years after completion of the study. There were descriptions of the partnership in the published papers but there does not appear to have been a formal evaluation of the partnership itself.

Summary: neither the joint handwashing and environmental intervention in preschools nor the home education component had an effect on childrens' illness absenteeism.

Controlled clinical trials (CCTs)

Melle 2008 (a controlled clinical trial with medium risk of bias) investigated the effectiveness of community and health professional educational campaigns to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis through early referral and prompt assessment and treatment of those affected. Patients were recruited over a four‐year period and followed up for two years after recruitment. Power calculations suggested they needed to recruit 100 patients in each group. The researchers invited 186 patients in the intervention area and 194 patients in the control area to join the study: 141 and 140 patients agreed, respectively (74% of all eligible patients). At recruitment the mean duration of untreated psychosis in the intervention group (n = 118) was five weeks (range 0 to 1196) and in the control group (n = 113) it was 16 weeks (range 0 to 966) (P < 0.01, Mann‐Whitney U test). Symptomatic and functional status was measured at two years in 118 patients from the intervention areas and 113 patients from the control areas. The mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia (PANSS) positive component was 9.13 (SD 4.97) in the intervention group and 9.06 (SD 4.02) in the control group. The mean PANSS negative component was 15.54 (SD 6.48) in the intervention group and 19.19 (SD 9.06) in the control group. The mean Global Assessment of Function (GAF) symptoms score was 53.64 (SD 17.68) in the intervention group and 50.81 (SD 14.54) in the control group. The mean GAF functioning score was 53.80 (SD 17.32) in the intervention group and 49.47 (SD 14.78) in the control group. Only the PANSS negative component score was statistically significant (P < 0.001, t test), in favour of the intervention group, after correcting for multiple testing.

Evaluation of the intervention

No process evaluation was identified.

Summary: the mean duration of untreated psychosis was significantly shorter in the intervention area but this is an intermediate outcome and it is not clear if it resulted in lasting health benefit. The intervention group had lower scores for the negative component of the PANSS scale than the control group at two‐year follow‐up and the difference was statistically significant. There were no significant differences between the two groups for the positive component of the PANSS scale or for the GAF function and symptom scores. The authors noted that clinical ratings of the PANSS scale had not been masked and there was therefore the possibility of assessment bias.

Challis 2002 (a controlled clinical trial with high risk of bias) evaluated the Lewisham Case Management Scheme. This intensive scheme integrated social service case managers into a Community Mental Health Team for the Elderly; caring for a target population of older people with dementia. They had control over a devolved budget and had access to all relevant health and social care resources. The 45 patients in the intervention group and 50 in the control group appeared to be comparable at baseline. Follow‐up rates were different for each measure and only health measures with greater than 60% follow‐up are reported here. At six months the mean CAPE Behaviour Rating Scale score for disability, a composite measure of physical disability, social disturbance, communication disorder and apathy, increased from 14.94 (SD 5.11) to 15.83 (SD 5.60), mean change of 0.89, for the intervention group (n = 35); and decreased from 16.07 (SD 4.67) to 15.33 (SD 5.30) (n = 43), mean change of ‐0.74, for the control group: F = 2.87 (95% CI for the group difference ‐0.29 to 3.55, P value not significant). The mean level of risk to the cases decreased from 1.94 (SD 1.17) to 1.30 (SD 1.21), mean change of ‐0.64 in the intervention group (n = 33); and increased from 1.42 (SD 1.26) to 1.47 (SD 1.24), mean change 0.05 in the control group (n = 43) (95% CI for the group difference ‐1.30 to ‐0.07, P < 0.05). From the 43 matched pairs, 12 deaths were recorded in the intervention group and 15 in the control group at 24‐month follow‐up but the total number of deaths from the 95 participants was not reported. The study reported that around 80% of participants had carers, implying there were 75 carers in total. At 12 months the mean overall strain on carers decreased from 4.00 (SD 1.62) to 3.00 (SD 1.57), mean change of ‐1.0 in the carers for the intervention group (n = 26); and from 4.09 (SD 1.28) to 2.91 (SD 1.80), mean change of ‐1.18 in the carers for the control group (n = 32): F = 0.17 (95% CI for group difference ‐0.74 to 1.11, P value not significant). Malaise decreased from a mean of 5.92 (SD 5.28) to 4.32 (SD 4.34), mean change ‐1.60 in the carers for the intervention group (n = 25); and from 6.68 (SD 3.99) to 6.32 (SD 3.60), mean change ‐0.35 in the carers for the control group (n = 34): F = 2.84 (95% CI for group difference ‐2.73 to 0.23, P value not significant).

Evaluation of the intervention

The author supplied some additional information which reported progress of the project rather than formally evaluating the collaborative partnership. It demonstrated that the model had been highly valued and staff particularly appreciated having control over relatively small budgets. Local commissioners of health and social care jointly agreed to maintain the service and it has since become mainstream, recognised as providing good practice in terms of its integration and co‐location of staff.

Summary: the researchers' unblinded assessment of patients' overall level of risk indicated a decrease in the intervention group and an increase in the control group at six months. There was no difference in the CAPE Behaviour Rating Score between the intervention and control group patients at six months and no differences in strain or malaise between carers of the intervention and control patients at 12 months.

Cooper 1975 (a controlled clinical trial with high risk of bias) assessed the therapeutic value of attaching a social worker to a metropolitan primary care practice for the management of chronic neurotic illness. Participants were assessed at baseline and were broadly similar in demographic profiles. There were some differences between the groups in diagnoses but the paper reports the differences as being of doubtful significance to the findings. The psychiatric mean score at one‐year follow‐up decreased from 26.9 to 16.6, mean change ‐10.3 (SD 10.2) in the intervention group (n = 92); and from 26.1 to 19.7, mean change ‐6.4 (SD 9.9) in the control group (n = 97): test of significance t = 2.68, P < 0.01. The team analysed the impact various professional groups may have had on the ratings and concluded that the therapeutic effect of the experimental service was not confined to any one member or professional group in the team but a result of the group interaction.

Evaluation of the intervention

No process evaluation has been identified.

Summary: the psychiatric score of both groups decreased at one‐year follow‐up suggesting decreased clinical severity in both groups, more so in the intervention group than in the control group.