Abstract

Acromegaly is a progressive systemic disorder which is common among middle-aged women. A functioning growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma is the most common cause. Anaesthesia for pituitary surgery in patients with acromegaly is challenging. Rarely, these patients may develop thyroid lesions that may compromise the airway. We present the case of a young man with newly diagnosed acromegaly caused by a pituitary macroadenoma complicated by a large multinodular goitre. The aim of this report is to discuss the perianaesthetic approach in patients with acromegaly with a high risk of airway compromise undergoing pituitary surgery.

Keywords: Anaesthesia, Pituitary disorders, Thyroid disease, Neuroanaesthesia

Background

A young man presented to us with progressive acral changes, sexual dysfunction and peripheral vision loss. Biochemical assays and relevant imaging diagnosed the patient as suffering from acromegaly caused by a pituitary macroadenoma complicated by a large multinodular goitre (MNG) with retrosternal extension causing tracheal narrowing. He was posted for an urgent endoscopic trans-sphenoidal excision of the pituitary macroadenoma. We share our experience in the perioperative assessment, planning and successful execution of this case, with a brief review on acromegaly.

Case presentation

A man in his 40s with comorbidities of well-controlled hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to our institution with complaints of progressive painless enlargement of his hands and feet and jaw protrusion for the past 16 years. In addition, he claimed to have worsening peripheral vision over the past 1 month. For the past 10 years, he has noticed excessive sweating and increased body odour, with reduced libido and an inability to keep a firm erection during regular sexual intercourse. In addition, our patient complained of having a small painless swelling on the right side of his neck which had gradually enlarged over the past 2–3 years. He denied having a husky voice, stridor, shortness of breath, or symptoms of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. The patient also noticed that he had a scooped-in chest, which started to appear 5–6 years ago. He denied loss of appetite or weight, double vision, headaches, projectile vomiting, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) symptoms, breast swelling or nipple discharge.

On clinical examination, he was alert and conscious. His blood pressure (BP), pulse rate and oxygen saturation were 141/75 mm Hg, 72 beats per minute and 100% under room air, respectively. His pupils were reactive bilaterally with sizes of 3 mm each, without papilloedema. His cranial nerves were intact except for the optic nerve. Visual acuity (VA) in the right and left eyes was 6/18 and 6/60, respectively. Visual field examination revealed bitemporal hemianopia with right inferonasal quadrantanopia. His systemic neurological examination was normal. He has pectus excavatum and a palpable painless right thyroid mass measuring 3 cm × 2 cm in size (figure 1). There were no regional lymphadenopathies. Face examination showed thickened lips, prognathism, a large nose and macroglossia. Airway assessment showed Mallampati 3, with good mouth opening and a thyromental distance of more than 6 cm. Peripheral examination showed spade-like hands, skin tags and coarse skin all over the body.

Figure 1.

Pectus excavatum of the patient’s chest.

Investigations

Our patient’s full blood count, electrolytes, liver function tests and coagulation profile were within normal ranges. His haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level was 16.1% (normal values: 4%–6%). He had a fasting blood sugar (FBS) level of 8.2 mmol/L (normal values: <7 mmol/L) and a random blood sugar level of 10.8 mmol/L (normal values: <11 mmol/L).

His hormonal workup showed gross elevation of insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) at 949.1 nmol/L (normal values: 7–36 nmol/L), cortisol at 1464 nmol/L (normal values: 166–507 nmol/L), growth hormone (GH) at 63 pmol/L (normal values: 18–44 pmol/L), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) at 23.4 pmol/L (normal values: 2–10 pmol/L) and prolactin at 920 mIU/L (normal values: <425 mIU/L). There was reduction in testosterone hormone level at 1.88 nmol/L (normal values: 10–35 nmol/L) and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) at 0.183 mIU/L (normal values: 0.27–42 mIU/L). His follicle stimulating hormone, luteinising hormone, free triiodothyronine (FT3) and free thyroxine (FT4) were within normal values. The high-dose dexamethasone suppression test showed suppression of ACTH. Graves’ disease was ruled out as his serum anti-TSH receptor and anti-thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibodies were negative.

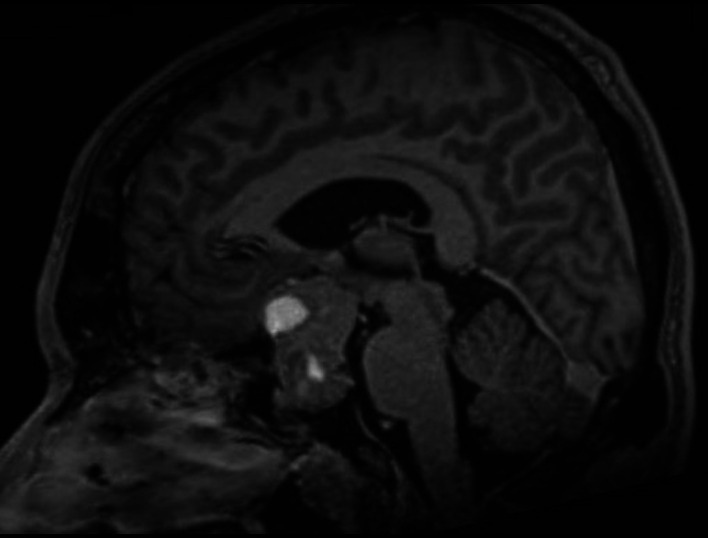

MRI of the brain showed a large lobulated sellar mass with suprasellar extension (snowman appearance). The size was 2.9 cm × 3 cm × 4.5 cm (figure 2). There was evidence of intratumoural calcification, haemorrhagic changes, and mass effect to the optic chiasm, bilateral frontal lobes and midbrain.

Figure 2.

Brain MRI of the patient showing pituitary macroadenoma.

His echocardiogram showed an ejection fraction of 72% with good left ventricular function. No valvulopathy was seen. His pulmonary function test showed normal lung compliance. An ultrasonography (USG) of the thyroid gland showed an MNG measuring 3.7 cm × 4.2 cm × 3.5 cm with retrosternal extension that was 3 cm deep. There were no enlarged adrenal glands seen via the abdominal USG.

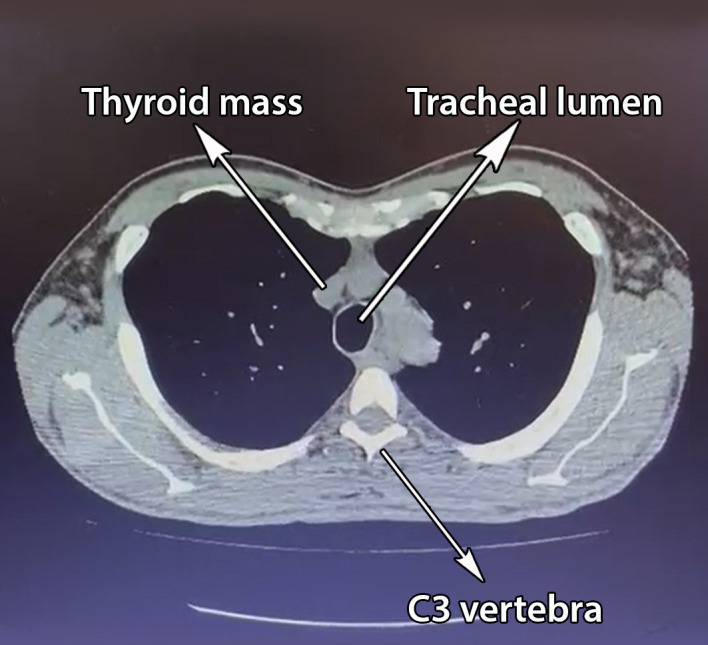

High-resolution CT (HRCT) of the thorax showed pectus excavatum and a retrosternal mass with soft tissue density encasing the trachea at the level of cervical 3 and 4 (C3–C4), which may represent the thyroid gland. There was a heterogeneous soft tissue lesion seen arising from the inferior pole of the right thyroid lobe measuring 4.1 cm × 3.2 cm × 3.7 cm (figure 3). The lesion exerted mass effect to the trachea, causing slight tracheal narrowing at this level and left tracheal deviation. The lumen at this area measured 2.1 cm × 1.3 cm. Both bronchi appeared to be of normal calibre. There were no lesions seen in both lungs.

Figure 3.

High-resolution CT of the thorax showing retrosternal mass encapsulating the trachea.

In view of his deteriorating vision, which necessitates urgent surgical intervention, radioactive iodine uptake thyroid scan to rule out toxic MNG was not done. Histopathological examination (HPE) of the suprasellar lesion revealed a synchronous prolactin and GH-secreting pituitary adenoma.

Differential diagnosis

The provisional diagnosis was acromegaly due to a GH-secreting pituitary macroadenoma and a concomitant MNG with retrosternal extension. As our patient was subclinically hyperthyroid, we did not administer any medication to suppress it. Due to his worsening visual symptoms, he was planned for an urgent transnasal trans-sphenoidal excision of pituitary macroadenoma.

Treatment

Surgical and anaesthetic consents, including for this manuscript’s publication, were obtained from the patient. He was briefed regarding the need and techniques of awake fibreoptic intubation (AFOI) on the eve of surgery. The patient fasted 8 hours prior to the elective surgery with intravenous (IV) normal saline 0.9% maintenance. He was carefully placed on the operating table with standard anaesthetic monitoring such as capnography, non-invasive blood pressure, ECG, pulse oximetry and core temperature. Antithyroid medications such as Lugol’s iodine, IV propylthiouracil, paracetamol, esmolol and hydrocortisone were kept within reach in the operating room in anticipation of a thyroid storm. IV glycopyrrolate 200 μg was given as antisialagogue and the patient was preloaded with 250 mL of Sterofundin over 20 min. His airway was anaesthetised with nebulised lignocaine 2%, and xylocaine spray 10% on the tonsillar pillars. Target-controlled infusion (TCI) of remifentanil was initiated at a dose of 1–2 ng/mL as anxiolytic agent during AFOI. A 7.5 mm-sized flexometallic endotracheal tube (ETT) was railroaded to the fibrescope. We employed the SAY-GO (spray as you go) method during oral AFOI with multiple aliquots of 2 mL of lignocaine 2%. The procedure was uneventful and the ETT was anchored at 22 cm from the lips. A throat pack was inserted to prevent debris from falling into the bronchus. A Ryles tube was inserted to enable us to administer Lugol’s iodine should he develop thyroid storm perioperatively.

After this, a right subclavian vein central venous line and radial artery catheter were inserted for fluid resuscitation and monitoring, respectively. General anaesthesia was maintained using TCI of remifentanil and propofol at a range of 2–9 ng/mL and 3–6 μg/mL, respectively, which were guided by bispectral index (BIS) at a range of 40–60. We employed a lung protective strategy which includes a tidal volume (TV) of 8 mL/kg, a respiratory rate of 12–16 breaths per minute and a positive end expiratory pressure of 6–8 cmH2O, generating a peak inspiratory pressure of 20–25 cmH2O. The patient’s haemodynamics were stable throughout the endoscopic resection. Intraoperatively, his serum glucose level was tightly controlled in the range of 8.2–14.3 mmol/L with the usage of insulin infusion. Diabetic ketoacidosis was ruled out as his urine ketone level was negative. Total blood loss was estimated at about 1.5 L and one unit of packed cells was transfused.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively, our patient was sent to the neurocritical care unit for monitoring and optimisation. We administered IV dexamethasone 8 mg three times per day for 24 hours as prophylaxis against laryngeal oedema. We performed qualitative and quantitative cuff leak test (CLT) prior to extubation. There were no audible hissing sounds around the ETT after deflation. Quantitatively, the cuff leak volume was 190 mL, which was more than 30% of the delivered TV. As both bedside tests showed a positive CLT, we safely extubated our patient to facemask oxygen. He did not develop stridor, worsening of visual loss, neurological deficits, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) rhinorrhoea or sepsis. However, he developed transient cranial diabetes insipidus, which was responsive to fluid challenges and subcutaneous desmopressin 1 μg. His serum glucose level was within normal values without the use of hypoglycaemic agents.

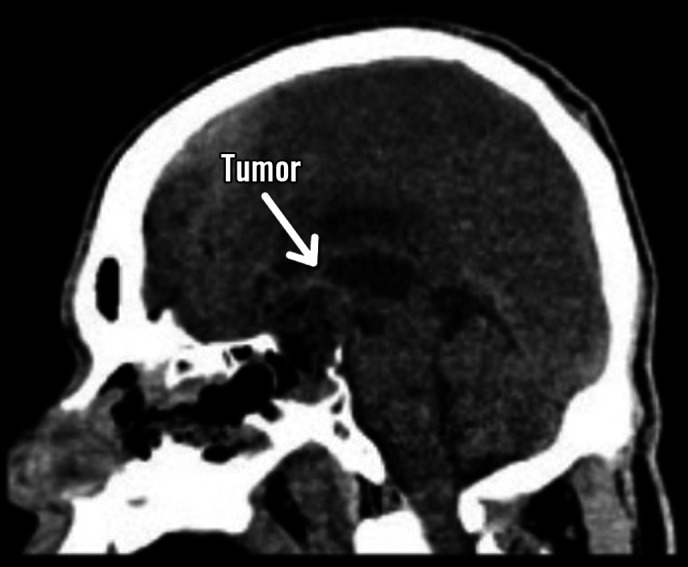

Our patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day. He was reviewed at the neurosurgical clinic 3 weeks later and his vision improved remarkably. The right thyroid mass was clinically palpable at 2 cm × 1 cm. A repeat endocrine investigation showed normal values of prolactin at 152.4 mIU/L, GH at 23 pmol/L, ACTH at 8.27 pmol/L, HbA1c at 6.1%, FBS at 5.9 mmol/L, cortisol at 365 nmol/L, FT3 at 9.21 pmol/L and FT4 at 18.56 pmol/L. The IGF-1 level was still raised at 87 nmol/L. There was a slight increase in his testosterone and TSH levels at 2.27 nmol/L and 0.251 mIU/L, although still below their normal values. Postoperative CT of the brain showed a residual pituitary lesion measuring 2.4 cm × 2.6 cm × 3.5 cm (figure 4). He was referred to an oncologist for commencement of postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy to arrest tumorous growth in view of the residual functioning pituitary macroadenoma.

Figure 4.

Postoperative CT of the brain showing remnants of the pituitary tumour.

Discussion

Pituitary adenomas account for 10%–15% of all intracranial masses. They are classified into macroadenomas (>10 mm) and microadenomas (<10 mm). Prolactinomas (40%–57%) and non-functioning adenomas (28%–37%) are the most common types, followed by GH-secreting adenomas (13%–20%).1 2

Acromegaly is a rare multisystem disorder characterised by disproportionate tissue and organ growth due to excess GH exposure after puberty. A GH-secreting pituitary adenoma is the cause in more than 98% of cases. The global prevalence of acromegaly is 60 cases per 1 000 000 population and is common in females at an average age of 43 years old.3 4 According to Burton et al,5 the incidence of acromegaly among males and females are 10 and 12 cases per million person-years, respectively. The average time to diagnose acromegaly is 4–5 years after the first acral changes.4 Our patient was diagnosed after more than a decade of noticing initial features of acromegaly. This delay is probably due to the progressive subclinical conditions and the lack of patient awareness and resources in seeking early treatment.

The clinical presentation of acromegaly is related to local mass effect by the adenoma and the sequelae of GH excess.6–8 Hypersecretion of GH by the tumorous pituitary somatotrophs causes elevated serum levels of IGF-1. Chronic exposure to GH and IGF-1 leads to pathological multisystemic changes, as seen in our patient. The enlarging pituitary macroadenoma may exert mass effect to the surrounding intracranial structures such as the optic chiasm and nerve fibres to cause blurring of vision and reduced VA, and may even cause panhypopituitarism.7 9 Progressive physiognomic alterations and growth of the acral parts are usually the initial manifestations of the disease. Hypersecretion of GH and IGF-1 causes impaired glucose control.10 11 Ghrelin, a GH secretagogue, enhances ACTH secretion by stimulating the effect on arginine vasopressin in the anterior pituitary gland.12 GH-releasing hormone and GH-releasing peptide-2 potentiate the response of both ACTH and cortisol to cause hyperglycaemia. A cerebral MRI is valuable in localising a pituitary macroadenoma and its invasion into neighbouring intracranial structures.13 These positive findings are sufficient to establish a diagnosis of pituitary acromegaly.

Detailed evaluation by USG or HRCT is recommended in patients with acromegaly due to the high prevalence of concomitant thyroid disorders.14 Non-toxic MNG is the most frequent type of thyroid disease, which occurs as a result of hyperstimulation of the thyroid follicular epithelium by the action of GH and IGF-1.15 Thyroid nodules are more prevalent in patients with active acromegaly, in which IGF-1 plays a role to regulate angiogenesis and the increased synthesis of vascular endothelial growth factor. Hypervascularisation with increased blood flow will be visualised via a colour Doppler USG of the thyroid gland.

Our patient had clinical signs of hypogonadism, suggesting compressive effect from a GH-secreting pituitary macroadenoma.15–17 HPE from the intraoperative pituitary macroadenoma revealed a synchronous prolactin-secreting and GH-secreting pituitary adenoma, which occurs in 25% of pituitary acromegaly cases.18 This explains the visceromegalic effects of GH onto the thyroid and adrenal glands to cause non-toxic MNG, raised serum ACTH and hypercortisolism, which progressively resolved postoperatively.12 19 Hyperprolactinaemia reduces secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone to cause hypotestosteronaemia and erectile dysfunction. Radiotherapy is offered to patients with macroadenomas that denied the ease of complete surgical excision, non-resectable residual tumours, or those who are actively secreting hormone despite maximal surgical and medical therapy. It achieves local control rates of up to 90% across all types of pituitary adenoma and complete biochemical responses in 50% of patients.20 Our patient’s postoperative CT of the brain showed remnants of non-resectable pituitary lesions with raised serum IGF-1 levels, an indication of radiotherapy despite normalisation of his endocrine function.

Anaesthesia in patients with acromegaly for pituitary surgeries is extremely challenging.21 Extra manpower is needed to help position the patient safely onto the operating table. Excessive peripheral soft tissue deposition in these patients may increase the risk of nerve entrapment syndromes, warranting careful attention during positioning. Carpal ligament hypertrophy may lead to ulnar artery compression, giving rise to a radial-dominant circulation. An Allen’s test should be performed to exclude this as radial artery cannulation for invasive BP monitoring poses a higher risk of hand ischaemia.22

Mask ventilation, laryngoscopy and tracheal intubation are challenging due to a combination of macrognathia, macroglossia and expansion of upper airway soft tissues.21 23 Large or sometimes extra-large sizes of face masks, laryngoscopes and blades are needed in anticipation of these issues. As tracheal stenosis may be present, gentle intubation is warranted when passing in a small-sized ETT to avoid airway trauma. Approximately 20%–50% of patients initially assessed as a Mallampati class 1 or 2 preoperatively were later found to be difficult to intubate with direct laryngoscopy.23–25 AFOI is the gold standard to safely secure the airway in these patients.26 27 In our patient, we inserted a sized 7.5 mm flexometallic ETT orally via AFOI to bypass the narrowest level at C3–C4 of the trachea to ensure a patent airway in case the large MNG collapses and compresses onto it intraoperatively.

The most common surgical approach for pituitary surgery is via transnasal trans-sphenoidal, with the advantages of minimal blood loss, direct access to the gland and avoiding the hazards of craniotomy. However, a huge pituitary macroadenoma may warrant a craniotomy for proper tumour debulking.

The principles of neuroanaesthetic care in endoscopic pituitary surgery are to maintain adequate cerebral perfusion pressure, avoid fluctuations in intracranial pressure (ICP), preserve cerebral autoregulation and allow rapid postoperative neurological assessment. These can be best achieved with TCI of remifentanil and propofol.28–30 Intraoperatively, transient hypercapnoea with a target of 40–45 mm Hg can temporarily increase ICP and improve exposure of the tumour by pushing it inferiorly into the sella to facilitate surgical resection.21 31

Bleeding could be extensive in larger tumours, especially with suprasellar extension which invaded into the cavernous sinus and internal carotid arteries.32 33 Continuous oozing from the small operative field can make surgical conditions difficult. Permissive hypotension with mean arterial pressure of 65–70 mm Hg can significantly reduce bleeding from the vascular bed and provide a clear field for surgical exploration.21

Postoperatively, patients require intensive care for at least 24–48 hours to monitor for cranial diabetes insipidus, CSF leak and sepsis. They may develop airway obstruction and laryngospasm due to trickling of blood and CSF from the nasopharynx. This may cause severe hypoxaemia especially in those with severe OSA. Prior to extubation, a CLT should be performed on patients who are at risk of postoperative airway obstruction. Ochoa et al34 mentioned that the sensitivity and specificity of CLT were 56% and 92%, respectively.35 It is also demonstrated that performing a CLT reduced the occurrence of postextubation stridor and decreased the rate of reintubation.

Anaesthesia for our patient was arduous yet interesting. Despite demonstrating subclinical hyperthyroidism, we investigated for the possibility of Graves’ disease by performing serum anti-TSH receptor and anti-TPO antibodies, which were negative. Nevertheless, extra anaesthetic vigilance of him developing thyroid storm perioperatively was taken. In addition, we eliminated potential causes of hypercortisolemia and increased ACTH secretions such as small cell carcinoma of the lung and adrenal malignancies. This was crucial as their presence might impair his cardiorespiratory haemodynamics. As our patient had a large MNG and pectus excavatum compromising the airway and ventilation, we safely secure it with AFOI. We employed TCI of remifentanil and propofol, guided by BIS monitoring, to ensure smooth and safe anaesthesia. Extensive bleeding and haemodynamic instability were navigated with intraoperative application of Moffett’s solution into the nostrils, permissive hypotension and blood transfusion. We share our perioperative airway concerns and management strategies in table 1.

Table 1.

Perioperative airway management strategies in patients with acromegaly with a huge MNG

| Patients’ clinical issues | Anaesthetic concerns | Anaesthetic management |

|

|

|

|

AFOI, awake fibreoptic intubation; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ETT, endotracheal tube; HRCT, high-resolution CT; MNG, multinodular goitre.

Patient’s perspective.

I am thankful to the surgeon and teams involved during my brain tumour surgery. Most importantly, the entire process was safe and smooth. I am lucky that my wife and children are very supportive of me. I hope to pull through this battle for my health safely.

Learning points.

Acromegaly is a rare progressive systemic disorder which is commonly caused by a growth hormone-secreting pituitary adenoma.

It is common for patients with acromegaly to develop thyroid nodules and non-toxic multinodular goitre (MNG).

Holistic perioperative planning, with extra care in airway management, is important to avoid total airway obstruction in patients with a huge MNG.

Transnasal trans-sphenoidal excision of pituitary macroadenoma is the mainstay of treatment for patients with acromegaly.

Cuff leak test should be performed on patients who are at risk of developing postextubation airway obstruction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patient and the management of Hospital Universiti Sains Malaysia (HUSM) for approval in the publication of this interesting case report.

Footnotes

Contributors: WMNWH, TBY and ARG were the clinicians involved in patient management. JDJ and TBY participated in manuscript writing.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Lake MG, Krook LS, Cruz SV. Pituitary adenomas: an overview. Am Fam Physician 2013;88:319–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehta GU, Lonser RR. Management of hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas. Neuro Oncol 2017;19:762–73. 10.1093/neuonc/now130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crisafulli S, Luxi N, Sultana J, et al. Global epidemiology of acromegaly: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol 2021;185:251–63. 10.1530/EJE-21-0216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lenders NF, McCormack AI, Ho KKY. MANAGEMENT of endocrine disease: does gender matter in the MANAGEMENT of acromegaly? Eur J Endocrinol 2020;182:R67–82. 10.1530/EJE-19-1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton T, Le Nestour E, Neary M, et al. Incidence and prevalence of acromegaly in a large US health plan database. Pituitary 2016;19:262–7. 10.1007/s11102-015-0701-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menon R, Murphy PG, Lindley AM. Anaesthesia and pituitary disease. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain 2011;11:133–7. 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkr014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melmed S. Acromegaly pathogenesis and treatment. J Clin Invest 2009;119:3189–202. 10.1172/JCI39375 Available: 10.1172/JCI39375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramírez C, Hernández-Ramirez L-C, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A-L, et al. Ectopic acromegaly due to a GH-secreting pituitary adenoma in the sphenoid sinus: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Res Notes 2013;6:411. 10.1186/1756-0500-6-411 Available: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lugo G, Pena L, Cordido F. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of acromegaly. Int J Endocrinol 2012;2012:540398. 10.1155/2012/540398 Available: 10.1155/2012/540398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazziotti G, Bonadonna S, Doga M, et al. Biochemical evaluation of patients with active acromegaly and type 2 diabetes mellitus: efficacy and safety of the galanin test. Neuroendocrinology 2008;88:299–304. 10.1159/000144046 Available: 10.1159/000144046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Subbarayan SK, Fleseriu M, Gordon MB, et al. Serum IGF-1 in the diagnosis of acromegaly and the profile of patients with elevated IGF-1 but normal glucose-suppressed growth hormone. Endocr Pract 2012;18:817–25. 10.4158/EP11324.OR Available: 10.4158/EP11324.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim CT, Khoo B. Normal physiology of ACTH and GH release in the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary in man [Endotext]. November 7, 2020.

- 13.Katznelson L, Laws ER, Melmed S, et al. Acromegaly: an endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014;99:3933–51. 10.1210/jc.2014-2700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rogozinski A, Furioso A, Glikman P, et al. Thyroid nodules in acromegaly. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 2012;56:300–4. 10.1590/s0004-27302012000500004 Available: 10.1590/s0004-27302012000500004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dąbrowska AM, Tarach JS, Kurowska M, et al. Thyroid diseases in patients with acromegaly. Arch Med Sci 2014;10:837–45. 10.5114/aoms.2013.36924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Laethem D, Michotte A, Cools W, et al. Hyperprolactinemia in acromegaly is related to prolactin secretion by somatolactotroph tumours. Horm Metab Res 2020;52:647–53. 10.1055/a-1207-1132 Available: 10.1055/a-1207-1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katznelson L, Kleinberg D, Vance ML, et al. Hypogonadism in patients with acromegaly: data from the multi-centre acromegaly registry pilot study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;54:183–8. 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2001.01214.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman M, Jusué-Torres I, Alkabbani A, et al. Synchronous GH- and prolactin-secreting pituitary adenomas. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep 2014;2014:140052. 10.1530/EDM-14-0052 Available: 10.1530/EDM-14-0052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loeffler JS, Shih HA. Radiation therapy in the management of pituitary adenomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:1992–2003. 10.1210/jc.2011-0251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ciresi A, Amato MC, Vetro C, et al. Adrenal morphology and function in acromegalic patients in relation to disease activity. Endocrine 2009;36:346–54. 10.1007/s12020-009-9230-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menon R, Murphy PG, Lindley AM. Anaesthesia and pituitary disease. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain 2011;11:133–7. 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkr014 Available: 10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkr014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esfahani K, Dunn LK. Anesthetic management during transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2021;34:575–81. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000001035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campkin TV. Radial artery cannulation. potential hazard in patients with acromegaly. Anaesthesia 1980;35:1008–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1980.tb05004.x Available: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1980.tb05004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn LK, Nemergut EC. Anesthesia for transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2013;26:549–54. 10.1097/01.aco.0000432521.01339.ab Available: 10.1097/01.aco.0000432521.01339.ab [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nemergut EC, Zuo Z. Airway management in patients with pituitary disease: a review of 746 patients. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2006;18:73–7. 10.1097/01.ana.0000183044.54608.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teah MK, Liew EHR, Wong MTF, et al. Secrets to a successful awake fibreoptic intubation (AFOI) on a patient with odentogenous abscess. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e238600. 10.1136/bcr-2020-238600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeap TB, Teah MK, Ramly AKM, et al. Anaesthetic challenges for a patient with huge superior mediastinal mass in prone position. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e242118. 10.1136/bcr-2021-242118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gemma M, Tommasino C, Cozzi S, et al. Remifentanil provides hemodynamic stability and faster awakening time in transsphenoidal surgery. Anesth Analg 2002;94:163–8, 10.1097/00000539-200201000-00031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gargiulo G, Cafiero T, Frangiosa A, et al. Remifentanil for intraoperative analgesia during the endoscopic surgical treatment of pituitary lesions. Minerva Anestesiol 2003;69:124–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cafiero T, Cavallo LM, Frangiosa A, et al. Clinical comparison of remifentanil-sevoflurane vs. remifentanil-propofol for endoscopic endonasal transphenoidal surgery. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2007;24:441–6. 10.1017/S0265021506002080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Korula G, George SP, Rajshekhar V, et al. Effect of controlled hypercapnia on cerebrospinal fluid pressure and operating conditions during transsphenoidal operations for pituitary macroadenoma. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2001;13:255–9. 10.1097/00008506-200107000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HW, Caldwell JE, Wilson CB, et al. Venous bleeding during transsphenoidal surgery: its association with pre- and intraoperative factors and with cavernous sinus and central venous pressures. Anesth Analg 1997;84:545–50. 10.1097/00000539-199703000-00014 Available: 10.1097/00000539-199703000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.AlQahtani A, London NR, Castelnuovo P, et al. Assessment of factors associated with internal carotid injury in expanded endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;146:364–72. 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.4864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ochoa ME, Marín M del C, Frutos-Vivar F, et al. Cuff-leak test for the diagnosis of upper airway obstruction in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1171–9. 10.1007/s00134-009-1501-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AK AK, Cascella M. Post intubation laryngeal edema. instatpearls [internet]. StatPearls Publishing, 2022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]