Version Changes

Revised. Amendments from Version 2

There are minor edits in the citations while some parts of the discussion have been revised with two additional citations for clarity.

Abstract

Background: Anemia is a severe public health problem affecting more than half of children under five years of age in low-, middle- and high-income countries. The study aimed to determine the prevalence and factors associated with anemia among children under five years of age in northern Tanzania.

Methods: This community-based cross-sectional study was conducted in Rombo district, Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania, in April 2016. Multistage sampling technique was used to select a total of 602 consenting mothers and their children aged 6-59 months and interviewed using a questionnaire. Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1. We used generalized linear models (binomial family and logit link function) with a robust variance estimator to determine factors associated with anemia.

Results: Prevalence of anemia was 37.9%, and it was significantly higher among children aged 6-23 months (48.3%) compared to those aged 24-59 months (28.5%). There were no significant differences in anemia prevalence by sex of the child. Adjusted for other factors, children aged 6-23 months had over two times higher odds of being anemic (OR=2.47, 95% CI 1.73, 3.53, p<0.001) compared to those aged 24-59 months. No significant association was found between maternal and nutritional characteristics with anemia among children in this study.

Conclusion: Prevalence of anemia was lower than the national and regional estimates, and it still constitutes a significant public health problem, especially among children aged 6-23 months. The study recommends iron supplementation, food fortification, dietary diversification, and management of childhood illnesses interventions for mothers and children under two years.

Keywords: Anemia, prevalence, risk factors, under five children, Tanzania

Introduction

In children under five years, anemia is a significant public health problem in the low-, middle- and high-income countries. The world health organization (WHO) defines anemia as a low blood hemoglobin concentration of less than 11g/dl in children under five years of age 1, 2 . Anemia in children is a major cause of adverse health consequences such as stunted growth, impaired cognitive development, compromised immunity, disability and increased risk of morbidity and mortality 2– 11 . Globally, about 43% of children under-five are anemic, and there is a marked variation in the prevalence of anemia between low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). Over 50% of anemic children live in LMIC 12 , and the highest prevalence rate (78%) was reported in Ghana and the lowest (26%) in Cuba 13, 14 . According to WHO, the African region has the highest proportion (62%) of anemic children 12 .

A variety of factors causes anemia, but the most common cause is iron deficiency 1, 3, 12 . Iron deficiency can result from inadequate dietary intake or poor absorption, increased needs for iron during the high growth periods, and increased iron loses due to helminths infection 3 . Other causes of anemia can be infections like malaria, genetic makeup, and nutritional deficiencies of vitamins B12, A, C and folate 3 . Factors associated with anemia also vary from region to region. The factors include the area of residence (whereby children living in rural areas beingmore at risk), low education level of the mother, child’s sex (high among males), child’s age (below 24 months) and history of infections, high birth order and maternal history of anemia 1, 4, 13– 20 . Unemployment, low family income, low wealth quartile and high poverty index have also been associated with anemia in children under five 5, 9, 15, 17 . In addition, poor breastfeeding practices and complementary feeding leads to anemia 7, 14– 16 .

To combat anemia in children, WHO recommends combined strategies such as iron supplementation, especially to vulnerable populations, food-based approaches to increase iron intake through food fortification and dietary diversification and management of infectious diseases, particularly malaria and helminth infections 21 . These strategies are recommended to be built into the primary health care system and existing programs such as maternal and child health, integrated management of childhood illness, adolescent health, safe motherhood, roll-back malaria, deworming and tuberculosis 21 . Improved quality of anemia care is also among key strategies to accelerate progress towards addressing this problem 22 . Although Tanzania is implementing these strategies 23 , the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) report shows no improvement in reducing anemia prevalence. For the two consecutive DHS rounds, 2010 and 2015, the prevalence of anemia was 58%. The results of the DHS show that the country is still far from reaching the set target of reducing anemia prevalence to 20% by 2020. In the Kilimanjaro region, Same District, anemia prevalence was 70% 19 . Since studies show variations in factors that are associated with anemia, there was a need to conduct this study in the Rombo district as an important step towards evidence-based decision-making when planning for interventions. Geographically Same is semi-arid district while Rombo is located around Mount Kilimanjaro, hence having different topographic conditions.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study utilized data from a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in Rombo district, Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania in April 2016. Rombo district is one of the seven districts of the Kilimanjaro region. The study aimed to assess the nutritional status of children under five years in the district. The district is bordered to the north and east by Kenya, to the west by Siha and Hai districts and to the south by Moshi rural district. According to the 2012 national population and housing census, Rombo district had a total population of 260,963 of which 124,528 (52.3%) were females while 29,955 were children under five years of which 14,971 (50%) were females 24 . The district’s largest population depends on agriculture, livestock keeping, small petty business, and few people are employed in the public sector. The district has 43 health facilities: 2 hospitals, four health centers and 37 dispensaries 25 .

Study population, sample size, and sampling

The study included consenting mothers and their children aged 6–59 months. A single proportion formula was used for sample size calculation. Using a standard normal value of 1.96 under 95% confidence interval, a 48% prevalence of anemia among children 6–59 months in Kilimanjaro region 2 , a margin of error of 5% and multiplying by a design effect of 1.5 to account for cluster design, the minimum required sample size was 575 mother-child pairs.

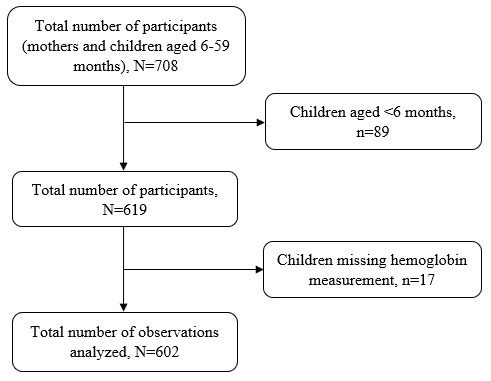

Multistage sampling technique was used to select 708 mother-child pairs from households with children aged 6–59 months. Two villages were randomly selected from each randomly selected ward. A listing of households with children under five years was generated with the help of village leaders or link persons, followed by a random selection of households. Systematic random sampling was used to select households. When the visited household had no child under five years of age, the next household was selected until the minimum required sample size was reached. If there were more than one child aged 6–59 months, the younger one was selected to represent the rest of the children in the household. If the child’s mother was not at home, the research team visited the house a minimum of three times before declaring that the participant could not be reached. Children whose mothers were not available on the day of data collection were excluded from the study as it was not possible to verify child information if next in kin or neighbor was interviewed. In addition, after excluding 89 children aged <6 months and 17 with missing hemoglobin concentrations, we analyzed data for 602 mothers-child pairs Figure 1.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram showing the number of participants.

Data collection methods

A questionnaire, shared as extended data , was used to collect data during face-to-face interviews. Although the questionnaire has not been validated in Tanzania, we adopted questions from the DHS and added some from previous literature. The following information was collected; maternal reproductive health, breastfeeding history, feeding patterns, initiation of complementary feeding, use of health facilities during pregnancy and child nutrition status. The questionnaire was in both English and Swahili languages but administered using the Swahili language, a language spoken by all the local people in this setting. Trained medical student at the Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College collected data under the Institute of Public Health supervision.

Study variables and measurements

The dependent variable in this study was anemia. Anemia was defined as a blood hemoglobin concentration below 11.0 g/dl in children under five years of age 1 . Blood samples were drawn among children from a drop of blood taken from a finger prick or heel prick (for children aged 6–11 months) and collected in a microcuvette strip. Hemoglobin (Hb) was measured on-site using a portable HemoCue rapid testing method (HemoCue ® Hb 301 Analyzer - HemoCue AB, Kuvettgatan 1, SE-262 71 Angelholm, Sweden). The anemia results were given on-site and children with severe anemia (hemoglobin level <7 g/dL) were referred to the nearby health facilities.

The independent variables included socio-demographical characteristics such as age of the mother in years (<20, 20–29 and 30+), education level, occupation (Peasant/farmer, Employed and Others), marital status (single, married/cohabiting and divorced/ separated/ widowed), area of residence (rural and urban depending on how the locals define them), alcohol consumption (Yes and No), body mass index (BMI) of the mother (underweight (<18.5Kg/m 2); normal weight (18.5–24.9 Kg/m 2), overweight (25–29.9 Kg/m 2), and obese (≥30 Kg/m 2)); and child’s age and sex. Nutritional characteristics included exclusive breastfeeding (Yes and No) 27 , colostrum feeding (Yes and No), meal frequency per day (≤3 meals and >3 meals), age at initiation of complimentary feeding (<6 months and 6+ months), and use of deworming drugs past six months (Yes and No).

Measurement of weight was performed using a SECA weighing scale (SECA GmbH & Co. KG, Hamburg, Germany) while recumbent length was measured for children aged <24 months and standing height was measured for older children using stadiometers. At least two measurements were taken then the average was calculated. Stunting, wasting, and underweight (height-for-age, weight-for-height z-score, and weight-for-age z-score below minus two standard deviations (-2 SD), respectively) from the median of the WHO reference population 2 . Child anthropometric z-scores were calculated using the 2006 WHO child growth standards through the “zscore06” package in Stata 28 .

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval was obtained from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College Research and Ethics Review Committee (KCMU-CRERC). Permission to conduct the study was also sought from the Rombo District Authority. Before data collection, logistics meetings were held with ward and village leaders of selected sites to inform them about the study’s purpose. The study purpose was explained to mothers before enrolment. Those who agreed to participate provided written informed consent. Unique identification numbers were used to ensure the anonymity of participant information.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata version 15.1, StataCorp LLC. Means and standard deviations were used to summarize numeric variables while frequency and percentages for categorical variables. Chi-square (χ 2) test was used to compare the prevalence of anemia by participant characteristics. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to determine factors associated with anemia in children using generalized linear models (GLM) with binomial family and logit link function adjusted for potential confounding. Akaike information criteria (AIC) was used to select the best model. The GLM model with binomial family and log link function was favored against the log-linear model, i.e., Poisson family with log link function hence all the analyses were performed using the former model. A robust variance estimator was used to account for model misspecification hence improving precision of estimates. The stepwise regression method was used to select variables included in the adjusted analysis at the 10% threshold level. The age of the child remained the only significant predictor of anemia at this stage. Maternal age, alcohol use (statistically significant in the crude analysis), sex of the child, and child’s nutritional characteristics, specifically exclusive breastfeeding, wasting, stunting, and underweight, were considered potential confounders, hence included in the final model.

Results

Background characteristics of mothers and children

Data were analyzed for a total of 602 mothers and children aged 6–59 months. The mean age (SD) of mothers in this study was 29.9±7.6 years. More than half (52%) of all mothers were aged between 20–29 years, 70% had primary school education level, 81.3% were married or cohabiting with their partners. The prevalence of obesity among women was 14.3%. The median age (IQR) of children in this study was 24 (14, 36) months while more than half (52.5%) were aged between 24–59 months. Also, more than half (52.7%) of all children were males Table 1 29 .

Table 1. Background characteristics of mothers and children (N=602).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

|

Age categories of the mother in

years * |

||

| Mean (SD) | 29.9 (7.6) | |

| <20 | 19 | 3.2 |

| 20–29 | 307 | 52.0 |

| 30+ | 264 | 44.8 |

| Education level * | ||

| None | 13 | 2.2 |

| Primary | 420 | 69.9 |

| Secondary and above | 168 | 28.0 |

| Marital status * | ||

| Single | 73 | 12.2 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 487 | 81.3 |

| Divorced/ separated/ widowed | 39 | 6.5 |

| Occupation * | ||

| Peasant/farmer | 366 | 64.9 |

| Employed | 160 | 28.3 |

| Others | 38 | 6.7 |

| Area of residence | ||

| Urban | 27 | 4.5 |

| Rural | 575 | 95.5 |

| Body mass index categories * | ||

| Normal | 285 | 47.9 |

| Underweight | 26 | 4.4 |

| Overweight | 199 | 33.4 |

| Obese | 85 | 14.3 |

| Consume alcohol | ||

| No | 367 | 60.9 |

| Yes | 235 | 39.0 |

|

Attended ANC during pregnancy for

this baby * |

||

| No | 13 | 2.2 |

| Yes | 585 | 97.8 |

| Number of ANC visits * (n=585) | ||

| ≥4 | 382 | 65.8 |

| <4 | 199 | 34.2 |

| Sex of the child | ||

| Male | 317 | 52.7 |

| Female | 285 | 47.3 |

| Age of the child (months) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 24 (14, 36) | |

| 6–23 | 286 | 47.5 |

| 24–59 | 316 | 52.5 |

*Variable with missing information.

Feeding practices and nutritional status of children

The vast majority (96.3%) were given colostrum while the overall prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding up to six months was 40.1%. Less than half (45.2%) of children in this study were given more than three meals per day and 69.7% were initiated complimentary feeding before six months. Also, 70.5% of children in this study were given deworming drugs. This study’s prevalence of wasting, stunting, and underweight was 10%, 38.5%, and 6%, respectively Table 2 29 .

Table 2. Nutritional characteristics (N=602).

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Child given deworming drugs * | ||

| No | 171 | 29.5 |

| Yes | 408 | 70.5 |

| Baby given colostrum * | ||

| No | 22 | 3.7 |

| Yes | 577 | 96.3 |

| Meal frequency per day * | ||

| ≤3 | 321 | 54.8 |

| >3 | 265 | 45.2 |

| Age at complementary feeding * | ||

| <6 months | 375 | 69.7 |

| ≥6 months | 163 | 30.3 |

| Child exclusively breastfed * | ||

| No | 349 | 59.9 |

| Yes | 234 | 40.1 |

| Wasted | ||

| No | 542 | 90.0 |

| Yes | 60 | 10.0 |

| Stunted | ||

| No | 370 | 61.5 |

| Yes | 232 | 38.5 |

| Underweight | ||

| No | 566 | 94.0 |

| Yes | 36 | 6.0 |

*Variable with missing information

Prevalence of anemia by child’s age and sex

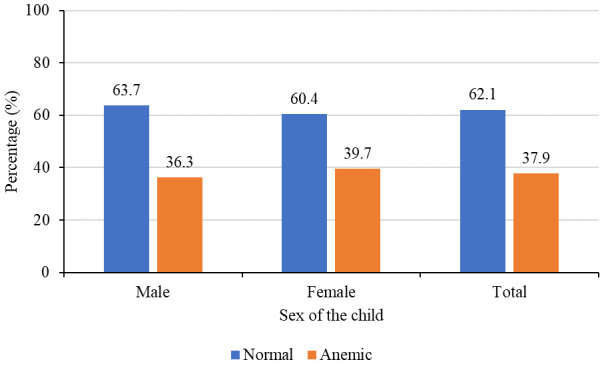

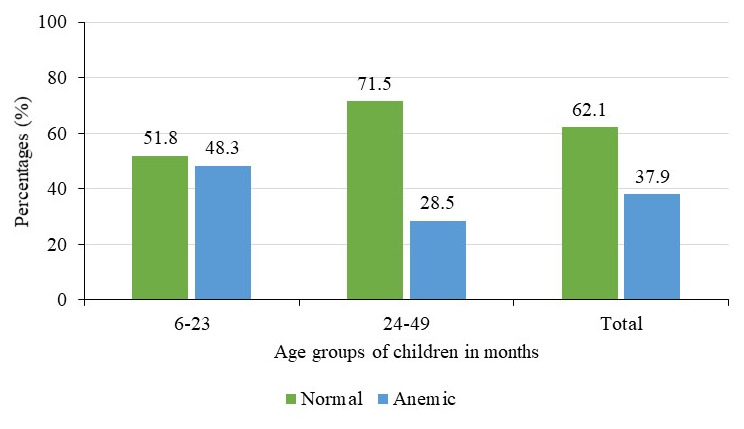

In this study, the mean (SD) hemoglobin level of children aged 6–59 months was 11.2±1.6g/dl and the prevalence of anemia (hemoglobin level less than 11g/dl) was 37.9%. Prevalence was slightly higher among females (39.7%) compared to 36.2% among males Figure 2 29 , but this difference was not significant (p=0.40). Prevalence was much higher among children aged 6–23 months (48.1%) compared to 28.5% among those aged 24–59 months Figure 3 29 . These differences in the prevalence by age were statistically significant (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Prevalence of anemia by sex of the child (N=602).

Figure 3. Prevalence of anemia by age groups of children in months (N=602).

Factors associated with anemia

The study performed crude and adjusted analyses to determine factors associated with anemia in children aged 6–59 months. In the crude analysis, factors associated with anemia were whether the mother consumed alcohol, exclusive breastfeeding, and child’s age Table 3 29 . Lower odds of anemia were observed among children whose mothers consumed alcohol (OR=0.68, 95%CI 0.48, 0.95, p=0.03). Higher odds of anemia were observed among children who were breastfed exclusively (OR=1.53, 95%CI 1.09, 2.14, p=0.02) and children aged 6–23 months (OR=2.34, 95%CI 1.67, 3.28) compared to those aged 24–59 months which showed a much stronger association with anemia (p<0.001). There was a positive association between stunting and the odds of anemia (OR=1.39, 95%CI 0.99, 1.95) but this association was not strong (p=0.06), Table 3 29 .

Table 3. Crude analysis for factors associated with anemia in children under five (N=602).

| Variables | N | Anemic (%) | COR * | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age categories of the mother in

years |

|||||

| <20 | 19 | 9 (47.4) | 1.58 | 0.62, 4.01 | 0.34 |

| 20–29 | 307 | 119 (38.8) | 1.12 | 0.79, 1.56 | 0.56 |

| 30+ | 264 | 96 (36.4) | 1.00 | ||

| Education level | |||||

| None | 13 | 3 (23.1) | 0.45 | 0.12, 1.70 | 0.24 |

| Primary | 420 | 158 (37.6) | 0.91 | 0.63, 1.31 | 0.61 |

| Secondary+ | 168 | 67 (39.9) | 1.00 | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 73 | 29 (39.7) | 1.09 | 0.66, 1.80 | 0.80 |

| Married/Cohabiting | 487 | 184 (37.8) | 1.00 | ||

| Divorced/ separated/ widowed | 39 | 14 (35.9) | 0.92 | 0.45, 1.74 | 0.82 |

| Occupation | |||||

| Peasant/farmer | 366 | 127 (34.7) | 0.72 | 0.49, 1.05 | 0.09 |

| Employed | 160 | 68 (42.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Others | 38 | 21 (55.3) | 1.67 | 0.82, 3.41 | 0.16 |

| Body mass index categories | |||||

| Normal | 285 | 116 (40.7) | 1.00 | ||

| Underweight | 26 | 10 (38.5) | 0.91 | 0.40, 2.08 | 0.82 |

| Overweight | 199 | 69 (34.7) | 0.77 | 0.53, 1.13 | 0.18 |

| Obese | 85 | 32 (37.7) | 0.88 | 0.53, 1.45 | 0.61 |

| Consume alcohol | |||||

| No | 367 | 152 (41.4) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 235 | 76 (32.3) | 0.68 | 0.48, 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Number of ANC visits | |||||

| ≥4 | 382 | 148 (38.7) | 1.00 | ||

| <4 | 199 | 73 (36.7) | 0.92 | 0.64, 1.31 | 0.63 |

| Child given deworming drugs | |||||

| No | 171 | 72 (42.1) | |||

| Yes | 408 | 150 (36.8) | 0.80 | 0.56, 1.15 | 0.23 |

| Baby given colostrum | |||||

| No | 22 | 10 (45.5) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 576 | 215 (37.3) | 0.71 | 0.30, 1.68 | 0.44 |

| Meal frequency per day | |||||

| ≤3 | 321 | 118 (36.7) | 1.00 | ||

| >3 | 265 | 105 (39.6) | 1.13 | 0.81, 1.58 | 0.48 |

| Age at complementary feeding | |||||

| <6 months | 375 | 137 (36.5) | 1.00 | ||

| ≥6 months | 163 | 71 (43.6) | 1.34 | 0.92, 1.95 | 0.13 |

| Child exclusively breastfed | |||||

| No | 349 | 120 (34.4) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 234 | 104 (44.4) | 1.53 | 1.09, 2.14 | 0.02 |

| Wasted | |||||

| No | 542 | 207 (38.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 60 | 21 (35.0) | 0.87 | 0.50, 1.52 | 0.63 |

| Stunted | |||||

| No | 370 | 129 (34.8) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 232 | 99 (42.7) | 1.39 | 0.99, 1.95 | 0.06 |

| Underweight | |||||

| No | 566 | 217 (38.3) | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 36 | 11 (30.6) | 0.71 | 0.34, 1.47 | 0.35 |

| Sex of the child | |||||

| Male | 317 | 115 (36.2) | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 285 | 113 (39.7) | 1.15 | 0.83, 1.61 | 0.40 |

| Child age categories | |||||

| 6–23 | 286 | 138 (48.1) | 2.34 | 1.67, 3.28 | <0.001 |

| 24–59 | 316 | 90 (28.5) | 1.00 |

*COR=Crude odds ratio

Adjusted analysis for factors associated with anemia in children is shown in Table 4 29 . A multivariable model was developed by adding and later removing one variable after another to assess the presence and effect of confounding. Age of the child was the only variable that remained to be strongly (p<0.001) associated with higher odds of anemia. Adjusted for mother’s age categories (years), whether a mother consumed alcohol during pregnancy, exclusive breastfeeding, wasting, stunting and child’s sex, children aged 6–23 months had over two times higher odds of being anemic (OR=2.47, 95%CI 1.73, 3.53) compared to those aged 24–59 months Table 4 29 .

Table 4. Adjusted analysis for factors associated with anemia in children under five (N=602).

| Variables | AOR * | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Age categories of the mother in

years |

|||

| <20 | 0.71 | 0.27, 2.84 | 0.48 |

| 20–29 | 0.86 | 0.59, 1.24 | 0.42 |

| 30+ | 1.00 | ||

| Consume alcohol | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.70 | 0.48, 1.02 | 0.06 |

| Child exclusively breastfed | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.38 | 0.97, 1.98 | 0.08 |

| Wasted | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.86 | 0.43, 1.72 | 0.66 |

| Stunted | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.40 | 0.97, 2.02 | 0.07 |

| Underweight | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.39, 2.52 | 0.98 |

| Sex of the child | |||

| Male | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.01 | 0.71, 1.44 | 0.94 |

| Child age categories | |||

| 6–23 | 2.47 | 1.73, 3.53 | <0.001 |

| 24–59 | 1.00 |

*AOR: Adjusted odds Ratio

Discussion

The prevalence of anemia among children aged 6–59 months in this study was 37.9%. Age of the child was the only factor significantly associated with anemia among children. This study’s prevalence of anemia in this study is much lower than the national and regional estimates 2 and other sub-population studies in Tanzania 9, 19 . One of these studies was hospital-based 9 , while the other included children aged 1–35 months 19 that could explain the differences. Prevalence in this study is also lower than those reported in other countries 5, 13, 15, 16, 30 . High prevalence in other studies could be linked to differences in the study population and wider population coverage since most utilized nationally representative data such as DHS data. A study by Ayoya et al. observed a similar prevalence (39%) among under-five children in Haiti 4 . Pita et al. observed a lower (26%) prevalence in Cuba 14 , which may be due to food-fortification interventions among other strategies 14 . Despite the observed differences, the prevalence reported in this study constitutes a significant public health problem 12 that needs intensified efforts.

In this study, adjusted for the background and nutritional characteristics, children aged 6–23 months had higher odds of having anemia than those aged 24–59 months. Infants (<24 months) are consistently reported to be at higher odds of being anemic in other studies 2, 4, 5, 13, 14, 31, 32 . Infants have a higher demand for nutrients needed for their growth, hence need proper complementary feeding. In this setting, there is a practice of giving porridge (a mixture of water, maize flour, and added sugar), cow’s milk and less diversified foods at a younger age 33 . This practice could be one of the factors that leads to poor anemia status in children 33, 34 . Also, conflicting advice on infant and young child feeding from various sources, including close relatives, community members, and health care providers affects breastfeeding practices, impacting the child’s anemia status 34 . Receiving quality anemia care, particularly nutrition advice about healthy foods and the minimum acceptable diet to the care giver, and routine hemoglobin measurement is critical in reducing anemia burden for children 6–23 months, who are most at risk 22 .

There were no significant differences in the prevalence of anemia by sex of the child in this study which is consistent with findings from other studies 13, 14, 18, 30 . On the contrary, females have been reported to be less likely to be anemic in Ethiopia 16 , which is contrary to findings from Kenya where the risk was high in male children (aged 6 months to 14 years) 31 , which could account for these differences. We did not find an association between maternal characteristics such as age categories, education level, occupation and ANC visits among others contrary to other studies. ANC visit and mother’s occupation have been associated with anemia elsewhere 7, 16 . The higher education level of mothers is protective against childhood anemia 15, 19, 31 .

Likewise, there was no association between nutritional characteristics such as deworming drugs uptake, exclusive breastfeeding (EBF), colostrum feeding, complementary feeding, and feeding frequency with anemia. However, other studies reported an association between nutritional characteristics with a higher risk of anemia in under-five children 4, 5, 14, 18, 33 . On the contrary, Meinzen-Derr et al. 20 reported that, infants exclusively breastfed for six months in developing countries might be at increased risk of anemia, especially among mothers with poor iron status. In addition, there is evidence that the longer the infant is exclusively breastfed, the worse the severity of childhood anemia due to low iron content in breast milk 35, 36 . The positive association between EBF and anemia was observed in this study but was not statistically significant. The effect of EBF on anemia in children is an area that needs further research. Despite the observed association in this study, nutritional interventions (EBF included) are among the key strategies to reduce the burden of anemia in under-five children 21, 23, 27 .

The study involved participants from most wards in the Rombo district, providing a picture of anemia in children under five. However, the findings in this study may not be generalized to other districts in Kilimanjaro and regions across the country. Also, the study might have been prone to recall and social desirability bias due to the self-reporting of nutritional practices associated with anemia. These may under or over-estimate these practices in the district.

Conclusion

The prevalence of anemia was lower than the national and regional prevalence but it still constitutes a significant public health problem especially among children aged 6–23 months. There were no significant differences in anemia prevalence by sex of the child and any of the nutritional characteristics. The study recommends iron supplementation, food fortification, dietary diversification, and management of childhood illnesses interventions for mothers and children under two years. Future studies should apply mixed methods, including longitudinal follow-up, to explore and determine the factors associated with anemia in children necessary to inform context-specific interventions.

Acknowledgements

We extend our profound appreciation to the Institute of Public Health, Department of Community Health of Kilimanjaro Christian Medical University College for providing the data used in this study. We also acknowledge all the study participants whose consent enabled this study to be successful.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

[version 3; peer review: 1 approved

Data availability

Underlying data

Harvard Dataverse: Anaemia in children under five years of age in rural Tanzania. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/KJMNID 29

This project contains the following underlying data:

-

-

anemiaU5_rombo2016data.tab (Data on anaemia prevalence and associated factors among children under five years of age in the Rombo district, Kilimanjaro region, Northern Tanzania)

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Zero "No rights reserved" data waiver (CC0 1.0 Public domain dedication).

Extended data

Figshare: Questionnaire: Nutritional status of children U5 years of age in Kilimanjaro Region, Northern Tanzania. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12553844.v2 26

This project contains the following extended data:

-

-

Questionnaire - Nutritional status of children U5 years of age - English.pdf (Study questionnaire - English)

-

-

Questionnaire - Nutritional status of children U5 years of age.pdf (Study questionnaire)

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

References

- 1. WHO: Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. World Health Organization,2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 2. MoHCDGEC, MoH, NBS, et al.: Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey and Malaria Indicator Survey (TDHS-MIS) 2015-16. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Rockville, Maryland, USA,2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 3. WHO: Global nutrition targets 2025: anaemia policy brief (WHO/NMH/NHD/14.4). Geneva: World Health Organization;2014. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ayoya MA, Ngnie-Teta I, Séraphin MN, et al. : Prevalence and risk factors of anemia among children 6–59 months old in Haiti. Anemia. 2013;2013:502968. 10.1155/2013/502968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khan JR, Awan N, Misu F: Determinants of anemia among 6–59 months aged children in Bangladesh: evidence from nationally representative data. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):3. 10.1186/s12887-015-0536-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kumar T, Taneja S, Yajnik CS, et al. : Prevalence and predictors of anemia in a population of North Indian children. Nutrition. 2014;30(5):531–7. 10.1016/j.nut.2013.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Parbey PA, Tarkang E, Manu E, et al. : Risk Factors of Anaemia among Children under Five Years in the Hohoe Municipality, Ghana: A Case Control Study. Anemia. 2019;2019:2139717. 10.1155/2019/2139717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Phiri KS, Calis JC, Faragher B, et al. : Long term outcome of severe anaemia in Malawian children. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e2903. 10.1371/journal.pone.0002903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simbauranga RH, Kamugisha E, Hokororo A, et al. : Prevalence and factors associated with severe anaemia amongst under-five children hospitalized at Bugando Medical Centre, Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Hematol. 2015;15(1):13. 10.1186/s12878-015-0033-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takele K, Zewotir T, Ndanguza D: Risk factors of morbidity among children under age five in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):942. 10.1186/s12889-019-7273-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, et al. : A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014;123(5):615–24. 10.1182/blood-2013-06-508325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO: The global prevalence of anaemia in 2011. Geneva: World Health Organization;2015. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ewusie JE, Ahiadeke C, Beyene J, et al. : Prevalence of anemia among under-5 children in the Ghanaian population: estimates from the Ghana demographic and health survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):626. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pita GM, Jiménez S, Basabe B, et al. : Anemia in children under five years old in Eastern Cuba, 2005-2011. MEDICC Rev. 2014;16(1):16–23. 10.37757/MR2014.V16.N1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goswmai S, Das KK: Socio-economic and demographic determinants of childhood anemia. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2015;91(5):471–7. 10.1016/j.jped.2014.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mohammed SH, Habtewold TD, Esmaillzadeh A: Household, maternal, and child related determinants of hemoglobin levels of Ethiopian children: hierarchical regression analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):113. 10.1186/s12887-019-1476-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woldie H, Kebede Y, Tariku A: Factors associated with anemia among children aged 6–23 months attending growth monitoring at Tsitsika Health Center, Wag-Himra Zone, Northeast Ethiopia. J Nutr Metab. 2015;2015:928632. 10.1155/2015/928632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Legason ID, Atiku A, Ssenyonga R, et al. : Prevalence of anaemia and associated risk factors among children in North-western Uganda: a cross sectional study. BMC Hematol. 2017;17(1):10. 10.1186/s12878-017-0081-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abubakar A, Uriyo J, Msuya S, et al. : Prevalence and risk factors for poor nutritional status among children in the Kilimanjaro region of Tanzania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(10):3506–18. 10.3390/ijerph9103506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Meinzen-Derr JK, Guerrero ML, Altaye M, et al. : Risk of infant anemia is associated with exclusive breast-feeding and maternal anemia in a Mexican cohort. J Nutr. 2006;136(2):452–8. 10.1093/jn/136.2.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO, UNICEF: Focusing on anaemia: Towards an integrated approach for effective anaemia control.Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization;2004. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitchinson C, Strobel N, McAullay D, et al. : Anemia in disadvantaged children aged under five years; quality of care in primary practice. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19(1):178. 10.1186/s12887-019-1543-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. MoHCDGEC: The national road map strategic plan to improve reproductive, maternal, newborn, child & adolescent health in Tanzania (2016 - 2020): One Plan II.Dar es Salaam, Tanzania,2016. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 24. NBS, OCGS: Population Distribution by Age and Sex.Dar es Salaam, Tanzania,2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Swai SJ, Damian DJ, Urassa S, et al. : Prevalence and risk factors for HIV among people aged 50 years and older in Rombo district, Northern Tanzania. Tanzan J Health Res. 2017;19(2). 10.4314/thrb.v19i2.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mboya IB, Mamseri R, John B, et al. : Questionnaire: Nutritional status of children U5 years of age in Kilimanjaro Region, Northern Tanzania.V2 ed: figshare;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 27. WHO: Global nutrition targets 2025: breastfeeding policy brief.World Health Organization,2014. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leroy JL: ZSCORE06: Stata module to calculate anthropometric z-scores using the 2006 WHO child growth standards. 2011. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mboya IB, Mamseri R, John B, et al. : Anaemia in children under five years of age in rural Tanzania.V1 ed: Harvard Dataverse;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Menon MP, Yoon SS, , Uganda Malaria Indicator Survey Technical Working Group : Prevalence and factors associated with anemia among children under 5 years of age–Uganda, 2009. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(3):521–6. 10.4269/ajtmh.15-0102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ngesa O, Mwambi H: Prevalence and risk factors of anaemia among children aged between 6 months and 14 years in Kenya. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113756. 10.1371/journal.pone.0113756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Assis AMO, Barreto ML, da Silva Gomes GS, et al. : Childhood anemia prevalence and associated factors in Salvador, Bahia, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2004;20(6):1633–41. 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000600022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kejo D, Petrucka PM, Martin H, et al. : Prevalence and predictors of anemia among children under 5 years of age in Arusha District, Tanzania. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2018;9:9–15. 10.2147/PHMT.S148515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mgongo M, Hussein TH, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. : “We give water or porridge, but we don’t really know what the child wants:” a qualitative study on women’s perceptions and practises regarding exclusive breastfeeding in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):323. 10.1186/s12884-018-1962-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Buck S, Rolnick K, Nwaba AA, et al. : Longer breastfeeding associated with childhood anemia in rural south-eastern Nigeria. Int J Pediatr. 2019;2019:9457981. 10.1155/2019/9457981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Burke RM, Rebolledo PA, Aceituno AM, et al. : Effect of infant feeding practices on iron status in a cohort study of Bolivian infants. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):107. 10.1186/s12887-018-1066-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]