Abstract

We used data of 32,542 prospective cohort study participants who previously received primary and one or two monovalent booster COVID-19 vaccinations. Between 26 September and 19 December 2022, relative effectiveness of bivalent original/Omicron BA.1 vaccination against self-reported Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection was 31% in 18–59-year-olds and 14% in 60–85-year-olds. Protection of Omicron infection was higher than of bivalent vaccination without prior infection. Although bivalent booster vaccination increases protection against COVID-19 hospitalisations, we found limited added benefit in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Keywords: COVID-19, vaccine effectiveness, SARS-CoV-2

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron (Phylogenetic Assignment of Named Global Outbreak lineage (Pango) lineage B.1.1.529) variant has been dominant in Europe since January 2022, causing large waves of infections because of high transmissibility and escape from vaccine- and infection-induced immunity [1]. Bivalent mRNA vaccines targeting the Omicron BA.1 subvariant and the original Wuhan strain of SARS-CoV-2 [2] have been available as booster vaccination for all individuals 12 years and older in the Netherlands since 19 September 2022. At that time, the Omicron BA.5 subvariant and not the Omicron BA.1 subvariant was the dominant Omicron subvariant in the Netherlands [3]. Individuals 60 years and older, medical risk groups and healthcare workers were invited by personal letters.

We present estimates of the relative effectiveness of bivalent Omicron BA.1-targeted vaccination against self-reported SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection between 26 September and 19 December 2022 among adults who had previously received primary vaccination and one or two monovalent booster vaccinations.

Study population

We used data from 32,542 participants of an ongoing prospective cohort study (VASCO) among community-dwelling Dutch adults aged 18–85 years who are followed with 3-monthly questionnaires and 6-monthly serum samples [4,5]. We only included participants who had received primary vaccination and one or two monovalent booster vaccinations before the start of the bivalent booster programme (19 September 2022). Follow-up started on 26 September 2022 (1 week after the start of the bivalent booster vaccination programme), or 3 months after the last monovalent vaccination or last prior infection (occurring before 26 September 2022), whichever came last. This is in line with vaccination policy, where individuals are eligible for a bivalent vaccine 3 months after vaccination or infection. Follow-up ended on 19 December 2022, at the date of first positive SARS-CoV-2 test or at the date of last completed follow-up questionnaire, whichever came first.

We included 12,988 participants aged 18–59 years who had previously received a primary vaccination series and one monovalent booster vaccination. We further included 19,554 participants aged 60–85 years who had previously received a primary vaccination series and one (n = 8,963) or two (n = 10,591) monovalent booster vaccinations. In total, 5,504 (42.4%) 18–59-year-olds and 11,900 (60.9%) 60–85-year-olds received a bivalent vaccine after 19 September 2022 (Table). Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, based on self-report or presence of anti-nucleoprotein antibodies [4], was present in 9,605 (74.0%) of 18–59-year-olds and 10,898 (55.7%) of 60–85-year-olds (Table). Participants who received the bivalent booster vaccine were older (median age: 51 vs 48 years in 18–59-year-olds) and more often had a medical risk condition (26.5% vs 18.0% in 18–59-year-olds; 41.9% vs 38.2% in 60–85-year-olds) than participants who did not receive a bivalent booster. Among 60–85-year-olds, the bivalent booster vaccine recipients had more frequently received two prior monovalent booster vaccinations than the non-recipients (58.2% vs 47.9%).

Table. Characteristics of participants included in the analysis of SARS-CoV-2 bivalent vaccine effectiveness, the Netherlands, September–December 2022 (n = 32,542).

| 18–59 years | 60–85 years | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Bivalent booster vaccination | No bivalent booster vaccinationa | p value | Overall | Bivalent booster vaccination | No bivalent booster vaccinationa | p value | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| All participants | 12,988 | 100 | 5,504 | 100 | 7,484 | 100 | NA | 19,554 | 100 | 11,900 | 100 | 7,654 | 100 | NA |

| Median age in years (IQR) | 49 (15) | 51 (12) | 48 (16) | <0.001 | 66 (6) | 66 (6) | 65 (6) | 0.054 | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 9,497 | 73.1 | 4,115 | 74.8 | 5,382 | 71.9 | <0.001 | 10,797 | 55.2 | 6,584 | 55.3 | 4,213 | 55.0 | 0.427 |

| Male | 3,484 | 26.8 | 1,388 | 25.2 | 2,096 | 28.0 | 8,756 | 44.8 | 5,316 | 44.7 | 3,440 | 44.9 | ||

| Other | 7 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

| Prior infectionb | ||||||||||||||

| No prior infection | 3,383 | 26.0 | 1,497 | 27.2 | 1,886 | 25.2 | 0.027 | 8,656 | 44.3 | 5,431 | 45.6 | 3,225 | 42.1 | <0.001 |

| Prior pre-Omicron infection | 1,331 | 10.2 | 569 | 10.3 | 762 | 10.2 | 2,105 | 10.8 | 1,246 | 10.5 | 859 | 11.2 | ||

| Prior Omicron infection | 8,274 | 63.7 | 3,438 | 62.5 | 4,836 | 64.6 | 8,793 | 45.0 | 5,223 | 43.9 | 3,570 | 46.6 | ||

| Medical risk conditionc, yes | 2,803 | 21.6 | 1,457 | 26.5 | 1,346 | 18.0 | <0.001 | 7,913 | 40.5 | 4,989 | 41.9 | 2,924 | 38.2 | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1,038 | 8.0 | 557 | 10.1 | 481 | 6.4 | 5,099 | 26.1 | 3,242 | 27.2 | 1,857 | 24.3 | ||

| Lung disease or asthma | 1,008 | 7.8 | 554 | 10.1 | 454 | 6.1 | 1,517 | 7.8 | 1,001 | 8.4 | 516 | 6.7 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 289 | 2.2 | 166 | 3.0 | 123 | 1.6 | 1,298 | 6.6 | 801 | 6.7 | 497 | 6.5 | ||

| Immune deficiency | 226 | 1.7 | 105 | 1.9 | 121 | 1.6 | 308 | 1.6 | 190 | 1.6 | 118 | 1.5 | ||

| Monovalent vaccination status before study periodd | ||||||||||||||

| Booster 1 | 12,988 | 100 | 5,504 | 100 | 7,484 | 100 | NA | 8,963 | 45.8 | 4,976 | 41.8 | 3,987 | 52.1 | <0.001 |

| Booster 2 | NA | 10,591 | 54.2 | 6,924 | 58.2 | 3,667 | 47.9 | |||||||

| Education levele | ||||||||||||||

| High | 8,266 | 63.6 | 3,674 | 66.8 | 4,592 | 61.4 | <0.001 | 10,334 | 52.8 | 6,511 | 54.7 | 3,823 | 49.9 | <0.001 |

| Intermediate | 3,901 | 30.0 | 1,527 | 27.7 | 2,374 | 31.7 | 5,253 | 26.9 | 3,128 | 26.3 | 2,125 | 27.8 | ||

| Low | 783 | 6.0 | 293 | 5.3 | 490 | 6.5 | 3,818 | 19.5 | 2,174 | 18.3 | 1,644 | 21.5 | ||

| Other | 38 | 0.3 | 10 | 0.2 | 28 | 0.4 | 149 | 0.8 | 87 | 0.7 | 62 | 0.8 | ||

| Bivalent vaccine product | ||||||||||||||

| Spikevax | NA | 2,689 | 48.9 | NA | NA | NA | 9,431 | 79.3 | NA | NA | ||||

| Comirnaty | NA | 2,687 | 48.8 | NA | NA | 1,774 | 14.9 | NA | ||||||

| Unknown | NA | 128 | 2.3 | NA | NA | 695 | 5.8 | NA | ||||||

| Time between bivalent vaccine and end of follow-up | ||||||||||||||

| Median (days) | NA | 33 | NA | NA | NA | 39 | NA | NA | ||||||

| Test intentionf | ||||||||||||||

| High | 10,368 | 79.8 | 4,748 | 86.3 | 5,620 | 75.1 | <0.001 | 16,306 | 83.4 | 10,401 | 87.4 | 5,905 | 77.1 | <0.001 |

| Middle/low | 2,620 | 20.2 | 756 | 13.7 | 1,864 | 24.9 | 3,248 | 16.6 | 1,499 | 12.6 | 1,749 | 22.9 | ||

COVID-19: coronavirus disease; IQR: interquartile range; NA: not applicable; SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

a Participants could only receive bivalent booster vaccination during the study period; no other COVID-19 vaccinations were provided.

b Prior infection at least 3 months before start of follow-up; pre-Omicron infection was defined as positive test date before 20 December 2021; Omicron infection was defined as positive test date after 9 January 2022; participants with prior infection in transition period from Delta to Omicron (20 December 2021–9 January 2022) were excluded; prior infection was based on self-reported test-confirmed infections or the presence of anti-nucleoprotein antibodies before the start of the study period. Date of prior infection based on anti-nucleoprotein antibodies (no corresponding infection reported) was imputed as mid-date between two blood samples, where the first was negative and the second was positive for anti-nucleoprotein antibodies, or where the second had at least a four‐fold increase in anti-nucleoprotein antibody concentration compared with the first. When the first serum sample of a participant was positive for anti-nucleoprotein antibodies, but no prior infection was reported, an infection date was imputed as the mid‐date between the baseline questionnaire and sample receipt. Serological analyses were done as previously described [4]. Of 31,448 participants (97%), at least one anti-nucleoprotein antibody result was available, with a median time of 104 days between last blood sample and start follow-up. Blood sample data were available until 16 September 2022.

c Medical risk condition: one or more of the following conditions: diabetes mellitus, lung disease or asthma, asplenia, cardiovascular disease, immune deficiency, cancer (currently untreated, currently treated, untreated), liver disease, neurological disease, renal disease, organ or bone marrow transplantation.

d Participants who received a third dose before the start of the general public booster campaign (18 November 2021) were excluded. Persons 60 years or older and only a very high-risk group younger than 60 years were eligible for second booster vaccination; therefore, participants younger than 60 years with a second booster vaccination were excluded.

e Educational level was classified as low (no education or primary education), intermediate (secondary school or vocational training) or high (bachelor’s degree, university).

f Information on test intention was obtained from the questionnaires. Participants were classified as high when in all questionnaires during the study period they answered “almost always” or “always” to the question whether they (would) test when having symptoms.

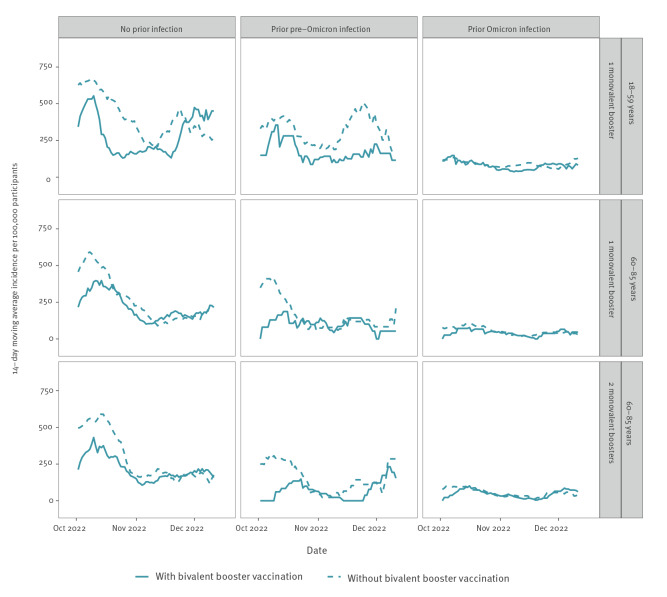

Incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection

During the study period, 3,005 SARS-CoV-2 infections, based on a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR or (self-administered) antigen test, were reported by the participants. The reported incidence in September and October 2022 was high (Figure 1), consistent with national data from syndromic and wastewater surveillance [6,7]. The incidence was highest among participants without any prior infection, lower among participants with a prior pre-Omicron infection, and lowest among participants with a prior Omicron infection. During most of the study period, the incidence was lower among participants who did receive than among those who did not receive a bivalent booster vaccine. However, it is important to note that the number of participants with a bivalent vaccine was small at the beginning of the study period and thus the incidence in these participants was based on a small number of infections. We provide further details on the number of participants and infections per vaccination status in Supplementary Figure S1.

Figure 1.

14-day moving average of number of SARS-CoV-2 infections reported per 100,000 participants by age group, prior infection status and vaccination status, the Netherlands, 26 September–19 December 2022 (n = 32,542)

SARS-CoV-2: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

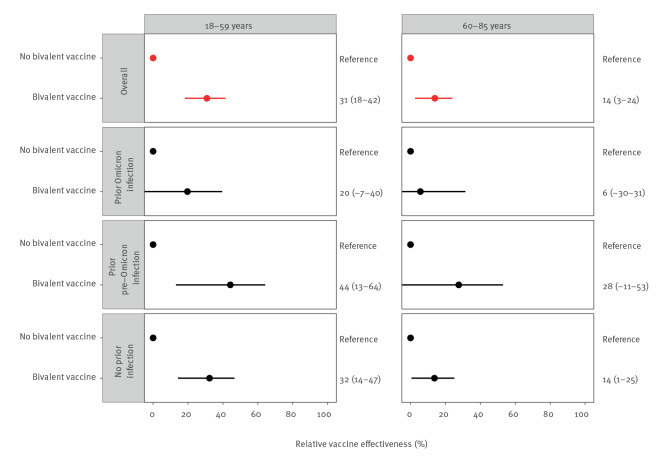

Relative vaccine effectiveness

To estimate effectiveness of bivalent vaccination relative to receiving the primary vaccination series and one or two monovalent booster vaccinations, we used Cox proportional hazard models with calendar time as underlying time scale and bivalent vaccination as time-varying exposure. Estimates were adjusted for age group, sex, education level and presence of a medical risk condition. We present stratified estimates by infection history and an overall estimate additionally adjusted for infection history. The 7 person-days after bivalent vaccine administration were excluded. All analyses were done using R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) and packages Epi and survival.

Among 18–59-year-olds who received primary vaccination and one monovalent booster, the overall relative effectiveness of bivalent vaccination against infection was 31% (95% confidence interval (CI): 18 to 42). Among participants with prior Omicron infection the relative effectiveness of a bivalent booster appeared lower (20%; 95% CI: −7 to 40) than among participants with no prior infection (32%; 95% CI: 14 to 47) or prior pre-Omicron infection (44%; 95% CI: 13 to 64), although confidence intervals largely overlapped (Figure 2). Among 60–85-year-olds who received primary vaccination and one or two monovalent booster vaccinations, overall relative effectiveness was 14% (95% CI: 3 to 24). Among participants with prior Omicron infection this was 6% (95% CI: −30 to 31). We provide number of infections, person time and estimates with confidence intervals per age group in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 2.

Relative vaccine effectivenessa and 95% confidence interval of bivalent COVID-19 vaccine overall and stratified by infection history and by age group, the Netherlands, 26 September 2022–19 December 2022 (n = 32,542)

COVID-19: coronavirus disease.

a Adjusted for age group (18–39, 40–59, 60–69, 70–85), sex, education level and presence of a medical risk condition; overall estimates were additionally adjusted for infection history.

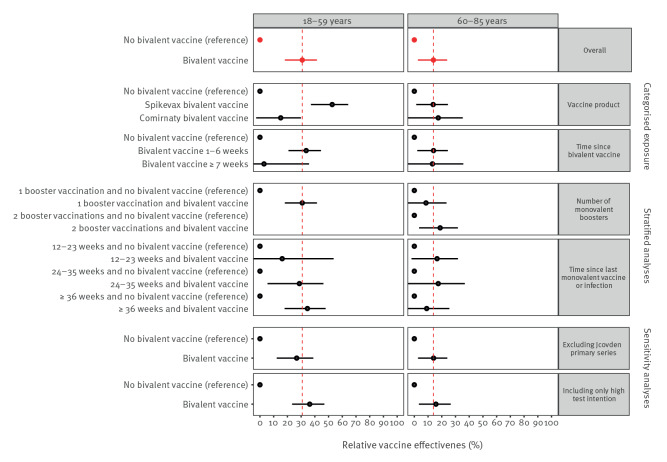

Estimates among 60–85-year-olds were similar to the main estimate across different stratified analyses and sensitivity analyses (Figure 3). Among 18–59-year-olds, stratification by bivalent vaccine product showed higher relative effectiveness of Spikevax (mRNA-1273, Moderna, Cambridge, United States (US)) than of Comirnaty (BNT162b2 mRNA, BioNtech/Pfizer, Mainz, Germany/New York, US) bivalent vaccine; of note, Spikevax was only given to individuals 45 years and older and therefore the median age in Spikevax recipients was higher than in Comirnaty recipients (54 vs 43 years) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stratified and sensitivity analysesa for relative vaccine effectiveness of bivalent COVID-19 vaccination by age group, the Netherlands, 26 September 2022–19 December 2022 (n = 32,452)

COVID-19: coronavirus disease.

a Adjusted for age group (18–39, 40–59, 60–69, 70–85), sex, education level, presence of a medical risk condition, and infection history. Categorised exposure = exposure categorised by (i) vaccine product (n = 31,719) and (ii) time since bivalent vaccination (n = 32,542); Stratified analyses = analyses stratified by (i) number of monovalent booster doses before start of follow-up (n = 32,542) and (ii) time since last monovalent booster at start follow-up (n = 32,542); Sensitivity analyses = analyses performed (i) excluding all individuals with a Jcovden (Ad26.COV2-S (recombinant), Janssen-Cilag International NV, Beerse, Belgium) primary series (n = 29,577)) and (ii) in only persons with a high intention to test during follow-up (n = 26,674).

In participants aged 18–59 years, compared with those without bivalent vaccination and without prior infection, relative effectiveness of bivalent vaccination among participants without prior infection (37%; 95% CI: 21 to 50) was similar to relative protection from a prior pre-Omicron infection and no bivalent vaccination (34%; 95% CI: 21 to 44), while relative protection from a prior Omicron infection with or without bivalent vaccination was substantially higher (80–83%). Similarly, participants aged 60–85 years showed higher relative protection from prior Omicron infection with (82%; 95% CI: 76 to 86) or without bivalent vaccination (82%; 95% CI: 79 to 85) than from bivalent vaccination (14%; 95% CI: 1 to 25) or prior pre-Omicron infection (43%; 95% CI: 32 to 52). We provide estimates with confidence intervals in Supplementary Table S2.

Discussion

We found that Omicron BA.1-targeted bivalent vaccination gave an overall relative vaccine effectiveness against Omicron SARS-CoV-2 infection of 31% in 18–59-year-olds and 14% in 60–85-year-olds who had previously received the primary vaccination series and at least one booster vaccination, adjusted for infection history.

Estimates of (relative) effectiveness of bivalent vaccination against infection are scarce. A recent study from the US reported slightly higher estimates against infection by the BA.4/BA.5-targeted bivalent vaccine (respectively 46%, 38% and 36% 6–7 months after last monovalent dose in individuals aged 18–49 years, 50–64 and ≥ 65 years) [8]. However, these estimates were not stratified by or adjusted for infection history. A preprint publication from the Nordic countries reported a relative effectiveness against hospitalisation of 75% for the BA.1-targeted bivalent vaccine in individuals aged ≥ 50 years [9]. Dutch surveillance data reported a relative risk reduction of 45% in 40–59-year-olds and of 58% after BA.1-targeted bivalent vaccination in individuals aged ≥ 60 years with at least one prior monovalent vaccination [10].

Our data showed that prior Omicron infection provided higher protection than bivalent vaccination among persons without prior infection, even though the time since prior Omicron infection was longer than the time since bivalent vaccination. This is consistent with a recent preprint publication estimating higher and longer protection after a breakthrough infection compared with booster vaccination [11]. In general, a combination of vaccination and infection, i.e. hybrid immunity, has been shown to provide better protection against infection than vaccination alone [12,13]. We did, however, find that prior pre-Omicron infection had a similar effect as bivalent vaccination without prior infection, probably because the time since pre-Omicron infection was substantially longer than the time since bivalent vaccination.

The VASCO cohort participants were given SARS-CoV-2 self-administered antigen tests free of charge, and we were not dependent on the SARS-CoV-2 testing infrastructure. In addition, serological data allowed us to detect prior untested (asymptomatic) infections. Confidence intervals overlap for the stratified analyses according to infection history, which makes it difficult to conclude there are real differences. Estimates can be confounded through differences in factors between participants who did and did not receive a bivalent booster vaccine, including test frequency and differences in exposure through behaviour. Participants who received a bivalent booster vaccine had a slightly higher intention to test, but restricting the analysis to participants with high test intention did not change our estimates. Since we investigated only participants who already received monovalent booster vaccination (so no unvaccinated individuals) and COVID-19 measures were limited during the study period, differences in SARS-CoV-2 exposure between bivalent vaccine recipients and non-recipients are likely to be limited. We will probably have missed some infections during the study period because of self-reporting, but we think this will have been comparable between persons with and without the bivalent vaccine.

Conclusion

The bivalent booster vaccination campaign has shown benefit in reducing COVID-19 hospitalisations, which is especially important for those at increased risk, including elderly people and those with a medical risk condition. However, we found limited added protection of bivalent vaccination in preventing SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection among persons who received primary vaccination and one or two monovalent booster vaccinations. Especially in persons with prior Omicron infection, the added benefit seems small.

Ethical statement

The VASCO study is conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the study protocol was approved by the not-for-profit independent Medical Ethics Committee of the Stichting Beoordeling Ethiek Biomedisch Onderzoek (BEBO), Assen, the Netherlands (NL76815.056.21).

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Dutch Ministry of Health.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary Data

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Authors’ contributions: All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. HdM, JvdW, SH, SvdH and MK designed the study. AH, BdG and CH cleaned and analysed the data. AH and MK drafted the manuscript. BdG, CH, HdM, SH, GdH, JvdW, SvdH and MK critically reviewed the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). One year since the emergence of COVID-19 virus variant Omicron. Geneva: WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/one-year-since-the-emergence-of-omicron

- 2.European Medicines Agency (EMA). First adapted COVID-19 booster vaccines recommended for approval in the EU. EMA; 2022. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/first-adapted-covid-19-booster-vaccines-recommended-approval-eu

- 3.Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM). Varianten van het coronavirus SARS-CoV-2.[Variants of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2]. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2023. Dutch. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/coronavirus-covid-19/virus/varianten

- 4. Huiberts A, Kooijman M, de Melker H, Hahne S, Grobbee D, Hoeve C, et al. Design and baseline description of an observational population-based cohort study on COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in the Netherlands - The VAccine Study COvid-19 (VASCO) [PREPRINT]. Research Square. 2022. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1645696/v1 [DOI]

- 5.Huiberts AJ, de Gier B, Hoeve CE, de Melker HE, Hahné SJM, Hartog Gd, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of primary and booster COVID-19 vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 infection in the Netherlands from 12 July 2021 to 6 June 2022: a prospective cohort study [PREPRINT]. medRxiv. 2023:2023.01.09.23284335. 10.1101/2023.01.09.23284335 10.1101/2023.01.09.23284335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Rijksoverheid. Coronadashboard: Virusdeeltjes in rioolwater. [Coronavirus dashboard. Virus particles in wastewater]. Den Haag: Rijksoverheid. [Accessed: 17 Jan 2023]. Dutch. Available from: https://coronadashboard.government.nl/landelijk/rioolwater

- 7.Rijksoverheid. Coronadashboard: Positief geteste mensen. [Coronavirus dashboard. Positive tests]. Den Haag: Rijksoverheid. [Accessed: 17 Jan 2023]. Dutch. Available from: https://coronadashboard.rijksoverheid.nl/landelijk/positief-geteste-mensen

- 8. Link-Gelles R, Ciesla AA, Fleming-Dutra KE, Smith ZR, Britton A, Wiegand RE, et al. Effectiveness of Bivalent mRNA Vaccines in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection - Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, September-November 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(48):1526-30. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7148e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Andersson NW, Thiesson EM, Baum U, Pihlström N, Starrfelt J, Faksová K, et al. Comparative effectiveness of the bivalent BA.4-5 and BA.1 mRNA-booster vaccines in the Nordic countries [PREPRINT]. medRxiv. 2023:2023.01.19.23284764 10.1101/2023.01.19.23284764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu (RIVM). RIVM COVID-19 epidemiologie en surveillance team. COVID-19 ziekenhuis en intensive-care-opnames per vaccinatiestatus in Nederland (opnames 3 oktober 2022 – 9 januari 2022). [COVID-19 hospital and intensive care admissions by vaccination status in the Netherlands (admissions 3 October 2022 – 9 January 2023)]. Bilthoven: RIVM; 2023. Dutch. Available from: https://www.rivm.nl/documenten/covid-19-ziekenhuis-en-intensive-care-opnames-per-vaccinatiestatus-in-nederland-5

- 11. Wei J, Matthews PC, Stoesser N, Newton JN, Diamond I, Studley R, et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant and anti-spike antibody responses after a third/booster vaccination or breakthrough infection in the UK general population [PREPRINT]. medRxiv. 2022:2022.11.29.22282916 10.1101/2022.11.29.22282916 [DOI]

- 12. Bobrovitz N, Ware H, Ma X, Li Z, Hosseini R, Cao C, et al. Protective effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and hybrid immunity against the omicron variant and severe disease: a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;S1473-3099(22)00801-5. 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00801-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Gier B, Huiberts AJ, Hoeve CE, Hartog Gd, van Werkhoven H, van Binnendijk R, et al. The effect of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 Omicron infection and relation with serological response – a prospective cohort study [PREPRINT]. medRxiv. 2023:2023.01.09.23284334 10.1101/2023.01.09.23284334 10.1101/2023.01.09.23284334 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.