Abstract

Background

The purpose of this investigation was to assess surgical outcomes after distal biceps tendon (DBT) repair for upper-extremity surgeons at the beginning of their careers, immediately following fellowship training. We aimed to determine if procedure times, complication rates, and clinical outcomes differed during the learning curve period for these early-career surgeons.

Methods

All cases of DBT repairs performed by 2 fellowship-trained surgeons from the start of their careers were included. Demographic data as well as operative times, complication rates, and patient reported outcomes were retrospectively collected. A cumulative sum chart (CUSUM) analysis was performed for the learning curve for both operative times and complication rate. This analysis continuously compares performance of an outcome to a predefined target level.

Results

A total of 78 DBT repairs performed by the two surgeons were included. In the CUSUM analysis of operative time for surgeon 1 and 2, both demonstrated a learning curve until case 4. In CUSUM analysis for complication rates, neither surgeon 1 nor surgeon 2 performed significantly worse than the target value and learning curve ranged from 14 to 21 cases. Mean Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score (QuickDASH) (10.65 ± 5.81) and the pain visual analog scale scores (1.13 ± 2.04) were comparable to previously reported literature.

Conclusions

These data suggest that a learning curve between 4 and 20 cases exists with respect to operative times and complication rates for DBT repairs for fellowship-trained upper-extremity surgeons at the start of clinical practice. Early-career surgeons appear to have acceptable clinical results and complications relative to previously published series irrespective of their learning stage.

Keywords: Distal biceps rupture, Distal biceps repair, Elbow surgery, Surgical complications, Patient reported outcome measures, Surgical learning curve

Distal biceps tendon (DBT) ruptures are frequently encountered in upper-extremity clinics, with an incidence around 2.55 per 100,000 patient-years.21 Most patients are male, and injury events usually occur during middle age (35-54 years) to the dominant extremity.21 The most common described mechanism of injury for DBT rupture is an excessive eccentric contraction of the biceps brachii with a flexed elbow and supinated forearm. Such precipitating activities include weight lifting, wrestling, and labor-intensive jobs.45 While controversy exists regarding the indications for operative treatment, surgery can improve strength and function after these injuries.16,19,23,33 In selected patients, nonoperative treatment can result in good functional outcomes and pain relief, even with expected decreases in supination strength.2,6,14,30 Treatment options for the DBT ruptures include either oneincision technique or twoincision techniques.46 For both techniques, multiple methods of tendon fixation to bone have been described including bone tunnels, suture anchors, interference screws, and cortical buttons. Repair and approach methods vary with respect to biomechanical advantages and pull-out strength.8,23,28,30 To date, no consensus has been reached regarding the preferred method of DBT fixation.1,8,17,28,29,38, 39, 40

It is commonly understood that proficiency at a given task requires repetition and time, but the length of time needed to achieve competence is not known. The time period of working toward gaining proficiency is often referred to as the “learning curve” period and is defined as the rate of a person's progress in gaining experience or new skills. These learning curves can be divided into a number of phases, including a consolidation phase (time in which the surgeon is gaining proficiency in performance) and a mastery phase (where surgeon performance reaches a steady state).9,11,22,25,34,47 Surgeons have typically referred to the number of cases needed to achieve a steady state of outcomes as the “learning curve”. More specifically, a learning curve is a graphical representation of the relationship between learning effort and learning outcome. It serves as a visual representation of the process of learning and allows researchers to employ statistical techniques to draw conclusions from the data.44 The learning curve for surgical procedures may depend on many variables, including the nature and difficulty of the case as well as the individual surgeon’s previous training experience. For example, procedures with less technical complexity that were frequently performed during training may be a shorter learning curve than highly technical procedures that were never performed during training.

Prior authors have aimed to evaluate the presence of a learning curve for common upper-extremity procedures and the results have been conflicting. 3,18,22,32,36 With respect to endoscopic carpal tunnel release, previous studies have indicated that the rate of conversion to an open procedure was higher during the learning curve period; however, complications did not differ relative to surgeon experience.3 In contrast, there have been reported increases in complication rates and length of hospital stay for shoulder and elbow arthroplasties performed by surgeons with less experience and in hospitals with lower volumes.18,32,36 Prior authors have determined that a learning curve for reverse shoulder arthroplasty may be around 40 cases.22 While DBT repair for acute ruptures has predictable outcomes and clearly defined rates of complications, it remains uncertain if the outcomes after DBT repair differ relative to primary surgeon experience with the procedure.

The purpose of this investigation was to assess surgical outcomes after surgical repair of acute DBT ruptures performed by upper-extremity surgeons at the beginning of their careers, immediately following fellowship training in hand or upper extremity. We aimed to determine if procedure times, complication rates, and clinical outcomes differed during the learning curve period for these early-career upper-extremity surgeons. We hypothesized that DBT repair would have a small learning curve and that surgical outcomes would be similar to those reported in previously published series.10,26,33,41

Materials and methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for this retrospective investigation.

We used our electronic billing database to identify all cases of DBT repair from August 2016 to December 2020. Patients were included if they were 18 years of age or older. Cases involving DBT reconstruction and cases with less than 6 months of follow-up time were later excluded from the clinical outcomes analysis. All cases were performed consecutively at the start of clinical practice by one of the two fellowship trained upper-extremity surgeons. The surgeons started clinical practice immediately after completing fellowship training (surgeon 1 in August 2016 and Surgeon 2 in August 2017). Cases were performed within a rural, level I trauma center which is part of an integrated, academic, tertiary referral center in the northeastern United States. All DBT repairs utilized the single-incision technique. The method of tendon fixation employed varied by surgeon during the study period, including repair with a cortical suture button or suture anchor.

Baseline demographics and surgical outcomes were recorded via manual chart review. Analysis was performed on a per-case, as opposed to a per-patient basis to account for patients with bilateral DBT repairs. Demographics recorded included age, sex, laterality, tobacco use, marital status, employment status, medical comorbidities as well as the presence of any mental, behavioral, or neurodevelopmental disorders (defined as any International Classification of Diseases-10 codes from F01 to F99). The surgical variables recorded included operative times and fixation method. Operative times were defined as time from incision until the placement of the dressing. In cases where the tendon could not be retrieved from the incision on the volar forearm, we recorded whether a second supplemental incision over the musculotendinous junction was utilized for tendon retrieval.

Postoperatively, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) including Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score (QuickDASH) and the pain visual analog scale (VAS) were collected along with range of motion measurements. All range of motion measurements were obtained by a certified occupational hand therapist using a manual goniometer. Postoperative complications were also recorded. Cases with a sensory neuropraxia of either the radial sensory or lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve were defined as “resolved” if the sensory symptoms resolved during the study period or “unresolved” if the patient had persistent subjective sensory symptoms at the time of final follow-up. Superficial infection was defined as an early postoperative wound infection that required local wound care and/or oral antibiotics, but did not require a return to the operating room for débridement. Deep infection was defined as any case that required a return to the operating room for débridement and irrigation. Any case of suspected rerupture after repair was confirmed with either a postoperative ultrasound or a magnetic resonance imaging.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were utilized for patient demographics and clinical outcomes when comparing cases characteristics between the two surgeons. Mean and standard deviation was reported for continuous variables, while total count and frequency was reported for categorical data. Categorical data were analyzed using chi-square (or Fisher’s Exact where appropriate) while continuous variables were analyzed using a 2-tailed Independent sample student’s t-test. The primary outcome variables were rates of complications and operative times for early career surgeons during the potential learning curve period. Complication rates were reported as frequencies. To investigate an association between number of completed cases and operative time, a linear regression analysis was performed for each surgeon. A two-sided type I error rate of 5% was used for all comparisons. No attempt was made to control for multiplicity of testing.

Cumulative sum analysis

A cumulative sum chart (CUSUM) analysis was performed to identify learning curve stages for operative times and complication rates. The CUSUM analysis continuously compares performance of an outcome to a predefined target level. This statistical analysis represents the most appropriate statistical method for evaluating a learning curve of a surgical procedure.42,47 For operative times, our target rate was defined as the mean values for each surgeon respectively.9,24,25 For complication rates, our predefined target rate was 44% based on prior postoperative complication rates reported in the current literature.26 All complications were included in this predefined target rate, including transient sensory neuropraxia. Further analysis on complication rates was conducted based on methodology outlined by Fu et al.15 Each case was assigned a value of “0” if there were any complications postoperatively or “1” if there were no complications (Table I). Complications included presence of neuropraxia at any time, superficial or deep infection, rerupture, or reoperation for any reason.

Table I.

CUSUM values were calculated as (1-s)+CUSUM for cases with complications and CUSUM-s for cases without. Cases with complications were coded at 0. Cases without complications were coded as 1.

| CUSUM variable formula | Value |

|---|---|

| Target complication rate | 44% |

| P0 | 0.44 |

| P1 = 2 × P0 | 0.88 |

| α | 0.05 |

| β | 0.2 |

| P = ln(P1/P0) | 0.693 |

| Q = ln[(1-P0)/(1-P1)] | 1.540 |

| S = Q/(P + Q) | 0.690 |

| 1-S | 0.310 |

| a = ln[(1-β)/α] | 2.773 |

| b = ln[(1-α)/β] | 2.558 |

| H0 = b/(P + Q) | −0.698 |

| H1 = a/(P + Q) | 1.241 |

CUMSUM, cumulative sum chart.

The resulting CUSUM curve graphs (Fig. 1, A and B, Fig. 3, A and B) from this analysis show all consecutive patients in a chronological order on the horizontal axes. The vertical axes show the cumulative performance on the metric, compared to the target level.42,47 CUSUM values were visually evaluated for both deviations from the target rate as well as a plateauing of data points, indicative of performance stabilization. A downward trend of the CUSUM graph indicates success and an upward trend indicates failure. A learning curve can be determined when the CUSUM curve indicates an upward trend in the first phase, also called learning phase, while a downward trend can be determined in a secondary phase, also called consolidation phase. In a final third phase, also called the mastery phase, performance reaches an optimal steady level.34 Inflection points were determined by 3 consecutive down trending points of change.9,25

Figure 1.

(A) CUSUM analysis of operative time for surgeon 1 across consecutive distal biceps repairs. (B) CUSUM analysis of operative time for surgeon 2 across consecutive distal biceps. CUSUM, cumulative sum chart.

Figure 3.

(A) CUSUM analysis of complication rate for surgeon 1 across consecutive distal biceps repairs where h1 is defined as a statistically significant “unacceptable” rate of performance and h0 is defined as a statistically significant “acceptable” rate of performance. (B) CUSUM analysis of complication rate for surgeon 2 across consecutive distal biceps repairs where h1 is defined as a statistically significant “unacceptable” rate of performance and h0 is defined as a statistically significant “acceptable” rate of performance. CUMSUM, cumulative sum chart.

Statistical significance was calculated with α = 0.05 and β = 0.2 According to Fraser et al, “when the CUSUM score remains above the decision limit h1, the actual failure rate is significantly greater than the acceptable failure rate, with a probability of type I error equal to α. When the CUSUM score remains below the decision limit h0, the actual failure rate does not differ significantly from the acceptable failure rate, with a probability of type II error equal to β”.11,13,24,27,49

Results

During the study period, a total of 78 DBT repairs were performed by the two surgeons and included for the CUSUM analysis (Appendix 1). All repairs were performed within 8 weeks from the time of injury. There were 24 cases included in the CUSUM analysis for surgeon 1 and 54 cases included for surgeon 2. There were 21 cases with less than 6 months of clinical follow-up or lacking appropriate PROM assessments and excluded from clinical PROM analysis, leaving 57 total cases for demographic and case characteristic analysis. For clinical analysis, surgeon 1 performed 18 cases (32%) whereas surgeon 2 performed 39 cases (68%) during the study period. Surgeon 2 utilized cortical button fixation for all 39 of their cases (100%), whereas surgeon 1 utilized a both anchor and cortical button fixation.

Table II summarizes the baseline demographics for included cases. The majority of cases were male (98%), and the mean age was 49 years (range; 33-78). Tables III and IV include surgical details, outcomes, and complications. There was an overall complication rate of 53% (95% confidence interval [40%-66%]). The most reported complication was sensory neuropraxia, which occurred in 27 cases. The average clinical follow-up was 20 months (range; 6-60). Mean operative time was 70 minutes (range; 27-165) with a 95% confidence interval of [62.04-77.54], but this differed between surgeons (103 vs. 54 minutes, P < .001). At the time of final follow-up, the mean QuickDASH and VAS pain scores were 10.65 (range; 0-61.36) and 1.13 (range; 0-8), respectively.

Table II.

Baseline demographics for the 57 cases of distal biceps tendon repair performed during the study period.

| All | Surgeon 1 | Surgeon 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, (n) | 57 | 18 | 39 | - |

| Age in yr, mean (SD) | 49.12 (±9.43) | 49.33 (±10.67) | 49.03 (±8.94) | .91 |

| Interquartile range | 12.75 | 10.5 | 15.25 | |

| Median | 49.5 | 48 | 50.5 | |

| Maximum | 78 | 78 | 64 | |

| Minimum | 33 | 35 | 33 | |

| Male, n (%) | 56 (98%) | 18 (100%) | 38 (97%) | 1.0 |

| Laterality right, n (%) | 31 (54%) | 10 (56%) | 21 (54%) | 1.0 |

| White race, n (%) | 57 (100%) | 18 (100%) | 39 (100%) | - |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 32.51 (±6.64) | 32.60 (±5.35) | 32.47 (±7.22) | .95 |

| Interquartile range | 6.72 | 5.74 | 8.54 | |

| Median | 31.24 | 30.31 | 32.23 | |

| Maximum | 59.18 | 43.7 | 59.18 | |

| Minimum | 19.37 | 25.49 | 19.37 | |

| Active tobacco use, n (%) | 10 (17%) | 4 (22%) | 6 (15%) | .71 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 6 (10%) | 1 (5%) | 5 (13%) | .65 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| ASA rating, n (%) | .94 | |||

| ASA 1-2 | 44 (77%) | 14 (78%) | 30 (78%) | |

| ASA 3-4 | 13 (23%) | 4 (22%) | 9 (23%) | |

| Mental, behavioral or neurodevelopmental disorder, n (%) | 14 (25%) | 4 (22%) | 10 (26%) | 1.0 |

| Married, n (%) | 43 (73%) | 13 (72%) | 30 (77%) | .96 |

| Employed, n (%) | 44 (75%) | 14 (78%) | 30 (77%) | 1.0 |

| Insurance type, n (%) | .041 | |||

| Private insurance | 46 (81%) | 13 (72%) | 33 (85%) | |

| Medicaid/Medical Assistance | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Medicare | 3 (5%) | 3 (17%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Self-Pay | 1 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other | 6 (11%) | 1 (6%) | 5 (13%) | |

| Worker’s compensation | 4 (7%) | 1 (6%) | 3 (8%) | 1.0 |

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table III.

Surgical details and outcomes for the 57 cases of distal biceps tendon repair performed during the study period.

| All | Surgeon 1 | Surgeon 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative details | ||||

| Cases, (n) | 57 | 18 | 39 | - |

| Operative time in minutes, mean (SD) | 69.79 (±29.87) | 103.06 (±26.56) | 54.44 (±15.25) | <.001 |

| Interquartile range | 38.75 | 39 | 21.5 | |

| Median | 63.5 | 97 | 50.5 | |

| Maximum | 165 | 165 | 89 | |

| Minimum | 27 | 72 | 27 | |

| Use of supplemental incision for tendon retrieval, n (%) | 6 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (15%) | .16 |

| Method of Fixation, n(%) | <.001 | |||

| Suture anchors | 13 (23%) | 13 (72%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Bicortical endobutton | 13 (23%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (33%) | |

| Unicortical endobutton | 31 (54%) | 5 (28%) | 26 (67%) | |

| Surgical outcomes | ||||

| Months follow-up, mean (SD) | 20.02 (±13.40) | 26.39 (±18.65) | 17.08 (±9.00) | .057 |

| Interquartile range | 14 | 28.75 | 11.5 | |

| Median | 14 | 21 | 13.5 | |

| Maximum | 60 | 60 | 43 | |

| Minimum | 6 | 6 | 6 | |

| Range of motion, mean degrees (SD) | ||||

| Flexion | 136.60 (±14.65) | 140.00 (20.00) | 135.21 (±11.85) | .27 |

| Interquartile range | 20 | 16.25 | 16.25 | |

| Median | 135 | 150 | 134 | |

| Maximum | 160 | 160 | 150 | |

| Minimum | 75 | 75 | 110 | |

| Flexion-extension arc | 135.05 (±16.59) | 139.69 (±20.12) | 133.15 (±14.78) | .19 |

| Interquartile range | 20 | 20 | 15.5 | |

| Median | 135 | 150 | 131.5 | |

| Maximum | 160 | 160 | 150 | |

| Minimum | 75 | 75 | 95 | |

| Pronation | 83.02 (±9.30) | 85.31 (±7.63) | 82.08 (±9.84) | .25 |

| Interquartile range | 10 | 6.25 | 10 | |

| Median | 85 | 90 | 85 | |

| Maximum | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| Minimum | 45 | 65 | 45 | |

| Supination | 82.42 ±(9.03) | 83.75 (±9.57) | 81.87 (±8.87) | .49 |

| Interquartile range | 10 | 11.25 | 10 | |

| Median | 85 | 90 | 81 | |

| Maximum | 90 | 90 | 90 | |

| Minimum | 60 | 65 | 60 | |

| Patient Reported Outcome Measures, mean (SD) | ||||

| VAS pain score | 1.13 (±2.04) | 0.72 (±1.77) | 1.32 (±2.14) | .31 |

| Interquartile range | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Median | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maximum | 8 | 7 | 8 | |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| QuickDASH | 10.65 (±15.81) | 10.42 (±17.28) | 10.76 (±15.33) | .94 |

| Interquartile range | 14.78 | 13.64 | 11.36 | |

| Median | 4.55 | 2.27 | 4.55 | |

| Maximum | 61.36 | 60.15 | 61.36 | |

| Minimum | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Table IV.

Complications after distal biceps tendon repair for surgeon 1 and surgeon 2.

| Complications | All N = 57 | Surgeon 1 N = 18 | Surgeon 2 N = 39 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases with any complications, n (%) | 30 (53%) | 9 (50%) | 21 (54%) | 1.0 |

| Sensory neuropraxia, n (%) | 27 (47%) | 7 (39%) | 20 (51%) | .56 |

| Resolved | 18 (32%) | 5 (28%) | 13 (33%) | .66 |

| Unresolved | 9 (16%) | 2 (11%) | 7 (18%) | |

| Time from surgery to neuropraxia resolution, mean (SD) | 107.33 (±90.07) | 124.60 (±138.24) | 100.69 (±70.37) | .63 |

| Superficial infection, n (%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1.0 |

| Deep infection, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Rerupture, n (%) | 3 (5%) | 2 (11%) | 1 (3%) | .23 |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (11%) | 0 (0%) | .096 |

| Posterior interosseous nerve injury, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

Operative time

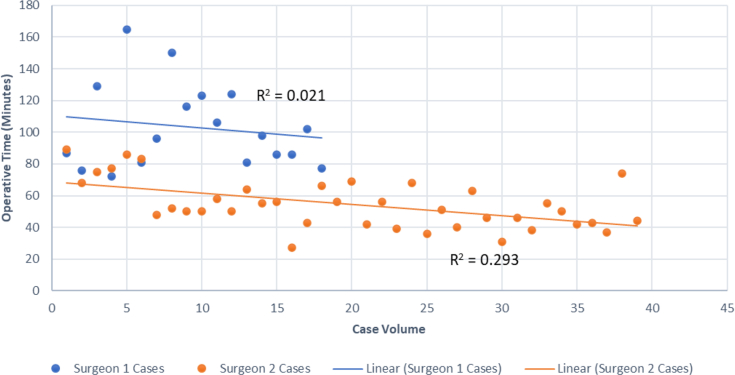

In the CUSUM analysis of operative time for surgeon 1 and 2, both demonstrated a learning curve until case 4. Surgeon 1 had a consolidation of performance until case 17, where there is a secondary inflection point representing the start of a plateauing of performance from case 18-24 (Fig. 1, A, Table V). Surgeon 2 had a consolidation of performance until the secondary inflection point at case 36, after which the upward trend back to target represents a plateauing of performance from case 37-54 (Fig. 1, B). Figure 2 displays a linear regression model on operative time and case volume for surgeon 1 and surgeon 2. Surgeon 1 had an adjusted R2 value of 0.021 and surgeon 2 had an adjusted R2 value of 0.293 (Fig. 2).

Table V.

CUSUM based competency phases for surgeon 1 and surgeon 2.

| Competency measure | Surgeon 1 |

Surgeon 2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Learning curve phase | Consolidation phase | Mastery phase | Learning curve phase | Consolidation phase | Mastery phase | |

| Operation time | 1st-4th case | 5th-17th case | 18th-24th case | 1st–4th case | 5th - 36th cases | 37th-54th case |

| Complication rate | 1st-14th case | 15th-24th case | - | 1st-21st case | 22nd-49th case | 50th–54th case |

CUMSUM, cumulative sum chart.

Figure 2.

Distal bicep operative repair time based on cases completed for 2 surgeons.

Complication rate

In CUSUM analysis of complication rate, neither surgeon 1 nor surgeon 2 performed significantly worse than the target value. Surgeon 1 had a consolidation of performance occurring after approximately 14 cases and performed significantly better than the target value after 16 cases (Fig. 3, A, Table V). In contrast, surgeon 2 had a consolidation of performance occurring after case 21 (Fig. 3, B) and performed significantly better than target value consistently after case 22. This suggests a 14-case learning curve for surgeon 1 and a learning curve of 21 cases for surgeon 2.

Table VI includes a comparison of results reported in our series as well as results from 6 prior recent published series. The complication rates reported in this study were within the range of previously reported rates (33%-73%).

Table VI.

Comparison of our results to other series of single-incision distal biceps repairs published in past ∼5 years.

| Our series | Series 1 Huynh et al20 | Series 2 Ford et al12 | Series 3 Matzon et al26 | Series 4 Siebenlist et al41 | Series 5 Cain et al5 | Series 6 Dunphy et al10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases with single approach, (n) | 57 | 60 | 652 | 112 | 24 | 188 | 639 |

| Fixation methods | Cortical button Suture anchor |

Cortical button | Cortical button (±Interference screw) Suture anchor Bone tunnel |

Cortical button Suture anchor |

Cortical button | Cortical button Suture anchor Bone tunnel |

Cortical button (±Interference screw) Suture anchor |

| Age in yr, mean (SD) | 49.12 (±9.43) | 46.1 (±7.6) | 49 | 48.7 | 49 | 48 | 48 |

| Operative time in minutes, mean (SD) | 69.79 (±29.87) | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 56.2 |

| Months follow-up, meanº (SD) | 20.02 (±13.40) | 44.4 (±20.4) | 5.6 | 3.9 | 28 (±16) | 9.7 | 49 |

| Range of Motion, meanº (SD) | |||||||

| Flexion | 136.60 (±14.65) | 134 (±11) | NR | NR | 126.7 | NR | 135 |

| Flexion-extension arc | 135.05 (±16.59) | 134 | NR | NR | 126.5 | NR | 132.9 |

| Pronation | 83.02 (±9.30) | 87 (±9) | NR | NR | 85 | NR | NR |

| Supination | 82.42 (±9.03) | 81 (±16) | NR | NR | 82.2 | NR | NR |

| Patient Reported Outcome Measures, mean (SD) | |||||||

| VAS pain scale | 1.13 (±2.04) | NR | NR | NR | 0.7 | NR | NR |

| QuickDASH | 10.65 (±15.81) | 7.9 (±11.4) | NR | NR | 3.8 (±7.6) | NR | NR |

| Cases with any complications, n (%) | 30 (53%) | 44 (73%) | 216 (33%) | 50 (45%) | NR | 70 (37%) | 243 (38%) |

| Sensory neuropraxia, n (%) | 27 (47%) | 7 (12%) | 149 (23%) | 47 (42%) | 2 (8%) | 62 (33%) | 186 (29%) |

| Resolved | 18 (32%) | NR | NR | NR | 2 (8%) | 186 (100%) | |

| Unresolved | 9 (16%) | NR | NR | NR | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Superficial Infection, n (%) | 1 (2%) | NR | NR | NR | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) | NR |

| Deep infection, n (%) | 0 (0%) | NR | NR | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | NR | NR |

| Rerupture, n (%) | 3 (5%) | 3 (5%) | 13 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (4%) | 4 (2%) | 10 (2%) |

| Reoperation, n (%) | 2 (4%) | NR | 28 (4.3%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (13%) | 6 (3%) | 15 (2%) |

| Posterior interosseous nerve injury, n (%) | 0 (0%) | NR | 12 (1.8%) | NR | 0 (0%) | 7 (4%) | 5 (1%) |

QuickDASH, Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand score; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analog scale.

Discussion

In assessing surgical outcomes after DBT repair for upper-extremity surgeons at the beginning of their careers, we reported a mean postoperative VAS pain scale and QuickDASH of 1.13 and 10.65, respectively. Results from our series (which included two surgeons within their learning-curve period) are similar to those reported by prior authors of recent series involving single incision DBT repairs. Both Huynh et al and Siebenlist et al reported postoperative QuickDASH scores of 7.9 and 3.8, respectively following DBT repair.20,41 Our results obtained by surgeons immediately following upper-extremity fellowship training are similar to those from large published series by experienced surgeons, suggesting that surgeon experience may not be associated with substantial changes in patient reported outcomes.

Previous literature has established complication rates after DBT repairs; however, our study suggests that a variability in this rate may be dependent on a surgeon’s experience.10,20,26 Our data suggest that there is a complication-based learning curve occurring within the first 14-21 cases for early-career upper-extremity surgeons. The rerupture rate reported in our investigation (5%) is consistent with prior published series and systematic reviews.5,10,12,20,26,41 Historically, single-incision techniques have been associated with a higher rate of nerve injury (15%-33%).2,28 Review of current series reporting on sensory neuropraxia demonstrates a range from 12% to 42%.5,10,12,20,41 More recently Matzon et al performed a large prospective cohort study of DBT repairs with 65 patients (30.7%) who had 73 complications.26 Fifty patients (44.6%) in the 1-incision group experienced complications compared with 15 (15.0%) in the 2-incision group.26 Overall, 57 patients (26.9%) had sensory neurapraxias.26 Of the patients with neurapraxias, 94.7% were resolved or improving at the time of the latest follow-up. Sensory neuropraxia occurred in 27 patients (47%), 7 patients (39%), and 20 patients (51%), respectively for each surgeon in our study. In total 18 (32%) patients resolved and 9 (16%) patients remained unresolved at 6-months follow-up. When comparing complications within the first year and beyond 1 year of practice, we found no difference in these rates for each surgeon (5 [71%] vs. 4 [36%] and 5 [83%] vs. 16 [48%], respectively).

The learning curve for operative time was 4 cases for both surgeons in our series. The consolidation phase, or time in which the surgeon is gaining proficiency in performance, varied from 13 to 32 cases for the two surgeons of our series. The mastery phase, where surgeon’s performance reaches a steady state, is suggested to occur after 18-36 cases for the two surgeons in our series. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report early surgeon performance with respect to DBT repairs. The CUSUM analysis has been supported as the standard method for reporting operative learning curves within orthopedics and other surgical specialties.42,43,47 In the upper extremity, Blaas et al supported a previously established operative learning curve of 15 cases for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for patients with proximal humerus fractures.4,7 In spine, a study by Yu et al reported a learning curve of 17-18 cases with respect to operative time for cases involving a robot-assisted pedicle screw fixation while an operative time learning curve of 58 cases for the lumbar decompressive laminectomy using a biportal endoscopic approach was reported by Park et al.35,48 Beyond orthopedics, CUSUM-based operative learning curves have reported to be approximately 30 cases for robot-assisted colorectal surgery, approximately 50 cases in surgical resection of advanced ovarian cancer, and 43 cases for robot-assisted transabdominal preperiotoneal repair of inguinal hernias.31,37,43 Notably, the CUSUM learning curve for operative time is shorter than complication rate for the two surgeons in our series while no learning curve for patient reported outcomes was reported.

Our investigation has a number of limitations which should be considered. Many of these limitations are inherent to retrospective series, including the fact that complications may be under-reported compared to prospective data collection. Of the 78 cases performed, 21 had <6 months of postoperative follow-up and were unable to be included in the assessment of PROMs. This study includes two surgeons and considering the small sample size of early career surgeons, it remains uncertain if these results are generalizable to a larger early career surgeon population. Surgeon 2 performed more than twice the number of cases as surgeon 1, and the impact of these differing case numbers remains uncertain. This study lacked an internal control group consisting of experienced surgeons at our institution. This would have allowed for more robust comparisons to the early-career surgeons, as comparison to prior published series is less ideal. However, the results of DBT repair have been extensively studied. This study included two surgeons in an academic practice, so it remains uncertain if these results are generalizable to other institutions or types of training. The surgeons utilized three fixation methods, and the small subgroup numbers would make meaningful comparisons between fixation methods difficult. There was no standardization of routine postoperative radiographs to evaluate for heterotopic ossification, incompletely evaluating this postoperative complication, although less likely in our cohort as only a single-incision DBT repairs were performed in all cases. The small sample size does not allow for analysis of shorter-time intervals to possibly elucidate changes in operative time and complications. We did not measure postoperative strength.

Conclusion

In summary, our data suggest a learning curve ranging between 4 cases and approximately 20 cases for operative times and complication rates, respectively after DBT repair for upper-extremity surgeons at the beginning of their careers. Early-career surgeons appear to have acceptable clinical results and complications relative to previously published series irrespective of their learning stage.

Disclaimers

Funding: There were no source of support in the form of grants, equipment, or other items.

Conflicts of interest: The authors, their immediate families, and any research foundation with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

Geisinger Institutional Review Board approved this study; FWA # 00000063; IRB # 00008345; IRB Study # 2019-0830.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseint.2022.09.013.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Balabaud L., Ruiz C., Nonnenmacher J., Seynaeve P., Kehr R., Rapp E. Repair of distal biceps tendon ruptures using a suture anchor and an anterior approach. J Hand Surg Br. 2004;29:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker B.E., Bierwagen D. Rupture of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii. Operative versus non-operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:414–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck J.D., Deegan J.H., Rhoades D., Klena J.C. Results of endoscopic carpal tunnel release relative to surgeon experience with the Agee technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:61–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaas L.S., Yuan J.Z., Lameijer C.M., van de Ven P.M., Bloemers F.W., Derksen R.J. Surgical learning curve in reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humerus fractures. JSES Int. 2021;5:1034–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cain R.A., Nydick J.A., Stein M.I., Williams B.D., Polikandriotis J.A., Hess A.V. Complications following distal biceps repair. J Hand Surg. 2012;37:2112–2117. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chillemi C., Marinelli M., De Cupis V. Rupture of the distal biceps brachii tendon: conservative treatment versus anatomic reinsertion – clinical and radiological evaluation after 2 years. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127:705–708. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0326-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi S., Bae J.H., Kwon Y.S., Kang H. Clinical outcomes and complications of cementless reverse total shoulder arthroplasty during the early learning curve period. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1077-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Citak M., Backhaus M., Seybold D., Suero E.M., Schildhauer T.A., Roetman B. Surgical repair of the distal biceps brachii tendon: a comparative study of three surgical fixation techniques. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1936–1941. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cundy T.P., Gattas N.E., White A.D., Najmaldin A.S. Learning curve evaluation using cumulative summation analysis—a clinical example of pediatric robot-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:1368–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunphy T.R., Hudson J., Batech M., Acevedo D.C., Mirzayan R. Surgical treatment of distal biceps tendon ruptures: an analysis of complications in 784 surgical repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:3020–3029. doi: 10.1177/0363546517720200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filho E.O., Rodrigues G. The construction of learning curves for basic skills in anesthetic procedures: an application for the cumulative sum method. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:411–416. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200208000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford S.E., Andersen J.S., Macknet D.M., Connor P.M., Loeffler B.J., Gaston R.G. Major complications after distal biceps tendon repairs: retrospective cohort analysis of 970 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1898–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser S.A., Feldman L.S., Stanbridge D., Fried G.M. Characterizing the learning curve for a basic laparoscopic drill. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2005;19:1572–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freeman C.R., McCormick K.R., Mahoney D., Baratz M., Lubahn J.D. Nonoperative treatment of distal biceps tendon ruptures compared with a historical control group. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2329–2334. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu Y., Cavuoto L., Qi D., Panneerselvam K., Arikatla V.S., Enquobahrie A., et al. Characterizing the learning curve of a virtual intracorporeal suturing simulator VBLaST-SS©. Surg Endosc. 2020;34:3135–3144. doi: 10.1007/s00464-019-07081-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garon M.T., Greenberg J.A. Complications of distal biceps. Orthop Clin North Am. 2016;47:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gregory T., Roure P., Fontes D. Repair of distal biceps tendon rupture using a suture anchor: description of a new endoscopic procedure. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:506–511. doi: 10.1177/0363546508326985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hammond J., Queale W., Kim T., McFarland E. Surgeon experience and clinical and economic outcomes for shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2318–2324. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200312000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hetsroni I., Pilz-Burstein R., Nyska M., Back Z., Barchilon V., Mann G. Avulsion of the distal biceps brachii tendon in middle-aged population: is surgical repair advisable? A comparative study of 22 patients treated with either nonoperative management or early anatomical repair. Injury. 2008;39:753–760. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2007.11.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huynh T., Leiter J., MacDonald P.B., Dubberley J., Stranges G., Old J., et al. Outcomes and complications after repair of complete distal biceps tendon rupture with the cortical button technique. JB JS Open Access. 2019;4:e0013. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.OA.19.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly M.P., Perkinson S.G., Ablove R.H., Tueting J.L. Distal biceps tendon ruptures: an epidemiological analysis using a large population database. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2012–2017. doi: 10.1177/0363546515587738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kempton L.B., Ankerson E., Wiater J.M. A complication-based learning curve from 200 reverse shoulder arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res®. 2011;469:2496–2504. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1811-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kodde F., Baerveldt R.C., Mulder P.G.H., Eygendaal D., van den Bekerom M.P.J. Refixation techniques and approaches for distal biceps tendon ruptures: a systematic review of clinical studies. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:e29–e37. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linsk A.M., Monden K.R., Sankaranarayanan G., Ahn W., Jones D.B., De S., et al. Validation of the VBLaST pattern cutting task: a learning curve study. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:1990–2002. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5895-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mackenzie H., Miskovic D., Ni M., Parvaiz A., Acheson A.G., Jenkins J.T., et al. Clinical and educational proficiency gain of supervised laparoscopic colorectal surgical trainees. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:2704–2711. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matzon J.L., Graham J.G., Penna S., Ciccotti M.G., Abboud J.A., Lutsky K.F., et al. A prospective evaluation of early postoperative complications after distal biceps tendon repairs. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44:382–386. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarter F.D., Luchette F.A., Molloy M., Hurst J.M., Davis K., Jr., Johannigman J.A., et al. Institutional and individual learning curves for focused abdominal ultrasound for trauma: cumulative sum analysis. Ann Surg. 2000;231:689. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200005000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meherin J.M., Kilgore E.S. The treatment of ruptures of the distal bi-ceps brachii tendon. Am J Surg. 1960;99:636–640. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyamoto R.G., Elser F., Millett P.J. Distal biceps tendon injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2128–2138. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morrey B.F., Askew L.J., An K.N., Dobyns J.H. Rupture of the distal tendon of the biceps brachii. A biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:418–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishikimi K., Tate S., Matsuoka A., Shozu M. Learning curve of high-complexity surgery for advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nitin J., Peitrobon R., Hocker S., Guller U., Shankar A., Higgins L. The relationship between surgeon and hospital volume and outcomes for shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:496–505. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen J.R., Shields E., Williams R.B., Miller R., Maloney M., Voloshin I. A comparison of cortical button with interference screw versus suture anchor techniques for distal biceps brachii tendon repairs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1607–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parisi A., Scrucca L., Desiderio J., Gemini A., Guarino S., Ricci F., et al. Robotic right hemicolectomy: analysis of 108 consecutive procedures and multidimensional assessment of the learning curve. Surg Oncol. 2017;26:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park S.M., Kim H.J., Kim G.U., Choi M.H., Chang B.S., Lee C.K., et al. Learning curve for lumbar decompressive laminectomy in biportal endoscopic spinal surgery using the cumulative summation test for learning curve. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:e1007–e1013. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.10.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poff C., Kunkle B., Li X., Friedman R.J., Eichinger J.K. Assessing the hospital volume–outcome relationship in total elbow arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31:367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2021.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Proietti F., La Regina D., Pini R., Di Giuseppe M., Cianfarani A., Mongelli F. Learning curve of robotic-assisted transabdominal preperitoneal repair (rTAPP) for inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc. 2021;35:6643–6649. doi: 10.1007/s00464-020-08165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranelle R.G. Use of the Endobutton in repair of the distal biceps brachii tendon. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2007;20:235–236. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2007.11928294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Recordon J.A.F., Misur P.N., Isaksson F., Poon P.C. Endobutton versus transosseous suture repair of distal biceps rupture using the two-incision technique: a comparison series. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:928–933. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2014.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Siebenlist S., Elser F., Sandmann G.H., Buchholz A., Martetschlager F., Stockle U., et al. The double intramedullary cortical button fixation for distal biceps tendon repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19:1925–1929. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siebenlist S., Schmitt A., Imhoff A.B., Lenich A., Sandmann G.H., Braun K.F., et al. Intramedullary cortical button repair for distal biceps tendon rupture: a single-center experience. J Hand Surg. 2019;44:418–418.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steiner S.H., Cook R.J., Farewell V.T., Treasure T. Monitoring surgical performance using risk-adjusted cumulative sum charts. Biostatistics. 2000;1:441–452. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.4.441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugishita T., Tsukamoto S., Imaizumi J., Takamizawa Y., Inoue M., Moritani K., et al. Evaluation of the learning curve for robot-assisted rectal surgery using the cumulative sum method. Surg Endosc. 2022;36:5947–5955. doi: 10.1007/s00464-021-08960-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valsamis E.M., Sukeik M. Evaluating learning and change in orthopaedics: what is the evidence-base? World J Orthop. 2019;10:378–386. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i11.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vestermark G.L., Van Doren B.A., Connor P.M., Fleischli J.E., Piasecki D.P., Hamid N. The prevalence of rotator cuff pathology in the setting of acute proximal biceps tendon rupture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1258–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waterman B., Navarro L. Primary repair of traumatic distal bicep ruptures: effect of 1 vs. 2-incision technique. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:e19–e20. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2017.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yap C.H., Colson M.E., Watters D.A. Cumulative sum techniques for surgeons: a brief review. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:583–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu J., Zhang Q., Fan M.X., Han X.G., Liu B., Tian W. Learning curves of robot-assisted pedicle screw fixations based on the cumulative sum test. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:10134. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i33.10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L., Sankaranarayanan G., Arikatla V.S., Ahn W., Grosdemouge C., Rideout J.M., et al. Characterizing the learning curve of the VBLaST-PT©(virtual basic laparoscopic skill trainer) Surg Endosc. 2013;27:3603–3615. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-2932-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.