Abstract

There is now a consensus that mitochondria are important tumor drivers, sophisticated biological machines that can engender panoply of key disease traits. How this happens, however, is still mostly elusive. The Opinion presented here is that what cancer exploits are not the normal mitochondria of oxygenated and nutrient-repleted tissues, but the unfit, damaged, and dysfunctional organelles generated by the hostile environment of tumor growth. These ghost mitochondria survive quality control and thwart cell death to relay multiple, comprehensive “danger signals” of metabolic starvation, cellular stress, and reprogrammed gene expression. The result is a new, treacherous cellular phenotype, proliferatively quiescent but highly motile that enables tumor cell escape from a threatening environment and colonization of distant, more favorable sites, or metastasis.

Keywords: mitochondria, tumor plasticity, Mic60, metastasis, metabolism

A NEW DAWN FOR MITOCHONDRIA IN CANCER

After decades of benevolent neglect, when the role of mitochondria in cancer was variously dismissed as dysfunctional, tumor suppressive or simply unimportant, there is now a resurgent interest in mitochondrial biology as a tumor driver [1, 2]. This is for good reason. we now know that the Warburg effect, the conversion of glucose to lactate even when oxygen is present and hallmark of most tumors, is not the only bioenergetics mean that sustains malignant growth [3]. In fact, elegant studies of stable isotope tracking have shown that mitochondria are not only functional in malignancy, but also that ATP produced via oxidative phosphorylation is required for tumor growth [4]. How much required likely depends on cellular context and tumor type, but data from cancer stem cells [5] and acquisition of metastatic competence [6] suggest that oxidative phosphorylation can drive multiple stages of tumorigenesis. And we also know that mitochondria are signaling organelles that impact virtually every facet of cellular homeostasis [7], orchestrating changes in nuclear gene expression [8], crosstalk with other organelles [9], buffering oxidative stress [10], and controlling multiple cell death pathways [11].

On this basis, one would conclude that mitochondria are among the most sophisticated, pleiotropic biological machines exploitable in cancer. Energetically, the efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation is unparalleled [12], capable of sustaining the most energy-intensive cellular processes. The endogenous mitochondrial antioxidant systems [13], coupled with adaptive control of cell death [14], is ideal to raise a general survival threshold in cancer, promote chemoresistance, and prevent anoikis during tumor dissemination. Despite the risk of proteotoxic stress typical of actively proliferating tumor cells and the vulnerability of the mitochondrial proteome to oxidative damage, mitochondria recruit a host of molecular chaperones, AAA+ proteases and sophisticated protein import and sorting mechanisms to ensure the stability, folding and function of the ~1,000 proteins in their proteome [15, 16]. And tumor cells hijack an elaborate machinery of subcellular trafficking that repositions mitochondria at the cortical, or peripheral cytoskeleton [17] to fuel key steps of cell motility, migration [18] and metastasis [19].

Altogether, this has led to the concept of mitochondrial reprogramming as a ubiquitous cancer tactic [20, 21], leveraging a diverse menu of organelle functions to sustain tumor growth [4], expand metabolic plasticity [22] and enable traits of aggressive disease, in particular metastasis [19] and drug resistance [23].

GHOST MITOCHONDRIA

Despite its appeal, there is a problem with the concept of mitochondrial reprogramming as a tumor driver. And that is that the microenvironment of primary and metastatic tumor growth is anything but ideal, and in fact can be detrimental to mitochondria [24]. This has to do with erratic and cycling oxygen concentrations, scarce to absent nutrients, and accumulation of oxidative radicals [25]. All these conditions are potent toxicants that can compromise mitochondrial functions [26], overcome the organelle’s buffering systems, shut off oxidative phosphorylation, and disrupt outer membrane integrity in protein import and cell death initiation. Mitochondrial dynamics is also deregulated in these settings and the smaller, i.e. fissed mitochondria that are generated are bioenergetically inefficient and prone to cell death activation [27]. Finally, degraded mitochondrial fitness triggers quality control mechanisms designed to regain homeostasis, mostly mitophagy [28], which ends up further lowering mitochondrial mass and function [26]. On balance, instead of exploitation, the intrinsic features of tumor growth seem ideally poised to accomplish precisely the opposite, poisoning the mitochondria, and degrade organelle fitness.

Recent experiments may offer a potential framework to make sense of this paradox. A recent shRNA screen unexpectedly identified Mic60, also called Mitofilin or inner mitochondrial membrane protein (IMMT) as a mitochondrial gene whose silencing promoted tumor cell invasion [29]. Few proteins seem as important as Mic60 in preserving mitochondrial integrity and fitness. As a constituent of a multi-protein MICOS complex [30], Mic60 ensures cristae architecture [31], organizes respiratory complexes [32], and enables outer membrane biogenesis [33]. A role of this pathway in cancer had not been previously explored, but analysis of public databases pointed to Mic60 as an essential gene in all tumor cell lines tested across different cancer types [29], in line with its maintenance of mitochondrial integrity [30].

The situation was much different, in vivo. In fact, Mic60 levels were highly heterogeneous in cancer patients, both intra- and inter-tumorally, and certain malignancies, dubbed Mic60-low had dramatically reduced or even absent levels of Mic60 [29]. The basis for a decreased expression of Mic60 in these conditions was not elucidated but reproducing this phenotype with deletion or silencing of Mic60 in tumor cells confirmed its essential requirement for mitochondrial integrity. Here, Mic60 depletion created acutely defective, ghost mitochondria with short, collapsed cristae. Inner membrane potential was dissipated, oxidative phosphorylation was shut down, and ATP production was inhibited, whereas mitochondrial fission was increased (Figure 1). This was accompanied by AMPK phosphorylation, a marker of cellular starvation, unbalanced antioxidant levels, heightened ROS production and DNA damage [29]. Taken together, it was not surprising that Mi60-low tumor cells activated quality control mechanisms of autophagy and mitophagy [26], stopped proliferating and failed to form xenograft tumors in mice. What was surprising was that despite this acutely deranged phenotype, Mic60-low cells did not die, as the levels of apoptosis, ferroptosis or necroptosis [11] were not significantly different, compared to controls [29].

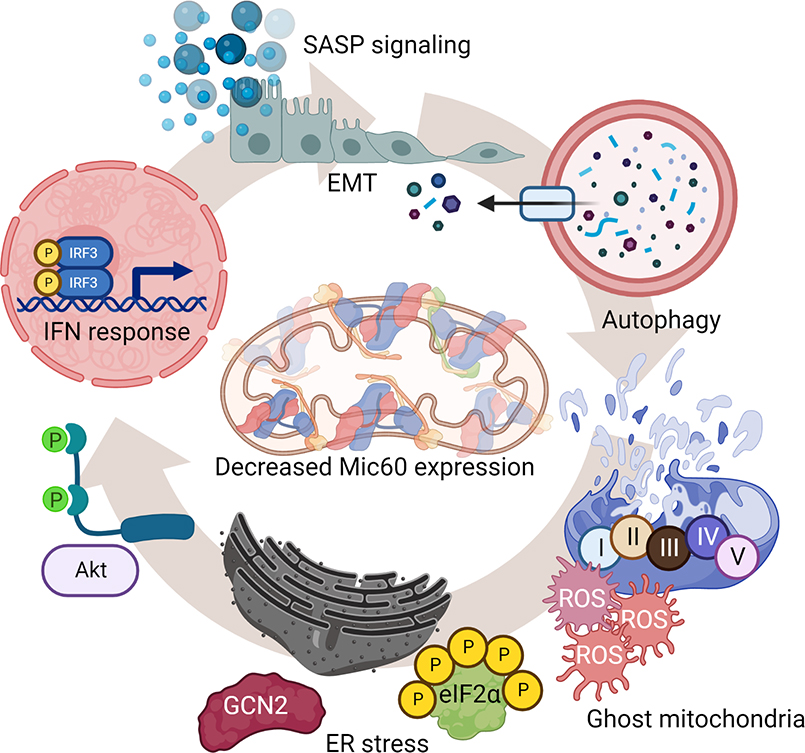

Figure 1. Cellular “danger signals” induced by Mic60 downregulation in cancer.

Mic60-low tumors exhibit ghost mitochondria characterized by collapsed and short cristae, disrupted outer membrane integrity, impaired oxidative phosphorylation with reduced ATP production and high generation of ROS. Together with activation of quality control measures of autophagy and mitophagy, Mic60-low tumors stimulate compensatory mitochondria-to-nuclei and mitochondria-to ER inter-organelle communication with induction of a type I IFN/SASP transcriptional signature and a GCN2-Integrated Stress Response (ISR), respectively.

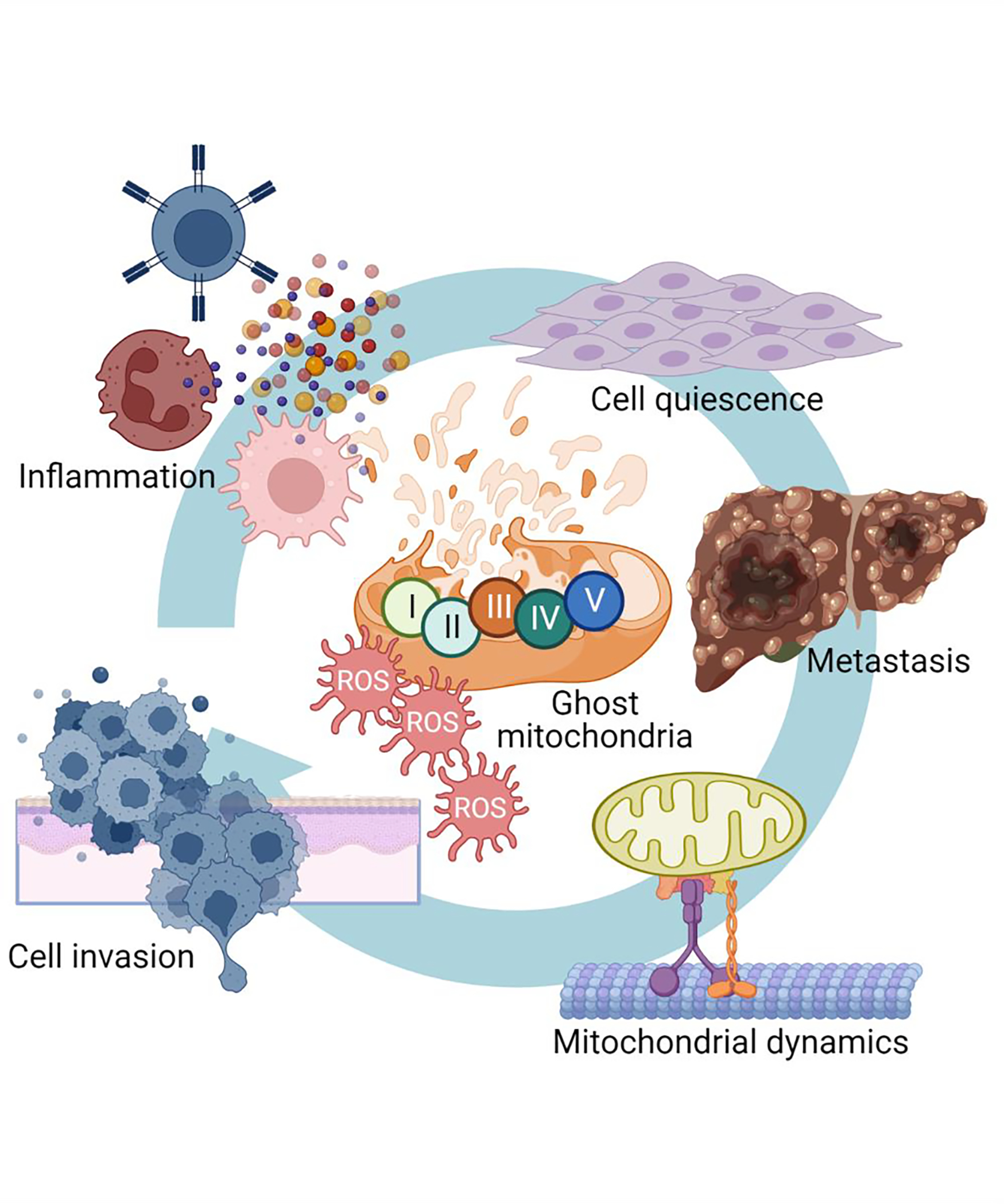

Clearly, compensatory pathway(s) of cellular adaptation had to be activated in Mic60-low tumors. In fact, this involved a two-pronged response. First, and consistent with mitochondria-to-nuclei “retrograde” signaling [34], Mic60-low tumors underwent extensive transcriptional changes with upregulation of a gene signature of innate immunity/type I interferon (IFN) response and cytokines/chemokines reminiscent of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [35]. Second, there was induction of an integrated stress response (ISR) after Mic60 depletion, with activation of the general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) kinase, phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), and upregulation of ISR effectors, activation transcription factor (ATF) 4, ATF6, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 α kinase 3 (eIF2AK3) and calreticulin [29]. The combination of IFN/SASP gene expression and GCN2/ISR signaling were not only compensatory but drove a new cellular phenotype in Mic60-low tumors (Figure 2). SASP signaling has long been seen as an enabler of aggressive tumor traits, promoting cell motility and invasion, in vivo [36]. Consistent with this, Mic60-low tumor cells became highly migratory and invasive, characterized by heightened mitochondrial fission [17], epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), phosphorylation of Focal Adhesion Kinase (FAK), and extensive metastatic dissemination in multiple mouse models, in vivo [29]. In parallel, ISR activation kept Mic60-low tumor cells alive despite mitochondrial damage and defective cellular functions. A pro-survival role of the ISR is known [37] and pharmacologic or genetic targeting of GCN2 as well as Akt preferentially killed Mic60-low cells, compared to controls [29].

Figure 2. Phenotype of Mic60-low tumors.

Downregulation of Mic60 and associated cellular “danger signals” stop cell proliferation but induce inflammatory cytokine and chemokine release, stimulate cell migration and invasion, activate mitochondrial dynamics and subcellular organelle trafficking and promote metastasis, in vivo.

NOT CLEAN WINDMILLS BUT STRESSED TINKERERS

Overall, these findings appear counterintuitive and call into question our current thinking of how mitochondria are exploited in cancer. Why would so many tumors downregulate an important gene like Mic60, creating dysfunctional, ghost mitochondria and consequently impair so many cellular functions, including cell proliferation (Figure 2)? And what purpose, if any, does a decrease in Mic60 expression serve in cancer? We know that mitochondria are important drivers of the metabolic plasticity that sustains tumor adaptation and heterogeneity [21]. But how can the ghost mitochondria of Mic60-low tumors contribute to this pathway with their collapsed integrity, impaired functions, and oxidative stress (Figure 1)?

One possible model is that tumors adaptively lower Mic60 expression in response to threatening environmental conditions, in vivo. What that threshold of environmental threat may be or how Mic60 downregulation is accomplished, whether by transcriptional or post-transcriptional means, is currently unknown. However, it can be speculated that if mounting levels of hypoxia, low nutrients and oxidative radicals reach a point where tumor cell proliferation is no longer possible [24], adaptive response(s) would likely be generated to deal with the threat and ensure tumor persistence. Such adaptive response may create the first trade-off in the Mic60 pathway: lower the expression of Mic60 to convert energy-producing and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-buffering mitochondria into dysfunctional ghost organelles that relay powerful “danger signals”. In fact, the phenotype of Mic60-low tumors is one of comprehensive cellular danger, dominated by metabolic starvation, oxidative stress, DNA damage, mitochondrial fission and compensatory mechanisms of autophagy and ISR that can lead to ell death if the originating stress conditions are not mitigated.

How, then, do the “danger signals” emanating from ghost mitochondria help tumor cells deal with a threatening environment? The goal is not to restore homeostasis but to create a new cellular phenotype that has the ability to escape the current, unfavorable environment and colonize a new, distant site with potentially better conditions. This is the phenotype observed experimentally in Mic60-low tumors, with increased migratory and invasive abilities and heightened metastatic potential, in vivo [29]. The idea that tumor spreading to distant organs could be conceptually equated to a cancer “diaspora” has been proposed before [38]. Many of the elements of this model are recognizable in the Mic60 pathway: the quality of the primary tumor microenvironment, the fitness and signaling competence of migrating cancer cells, and the quality of the target microenvironment(s) [38]. Consistent with this scenario, metabolic stress [39], increased mitochondrial fission [17] and heightened ROS production [40] are all features of Mic60-low ghost mitochondria and key enablers of tumor cell motility and metastasis. Sustained Akt and FAK phosphorylation, as also maintained in Mic60-low tumors ae equally essential to enable tumor cell movements [18]. And the SASP transcriptome upregulated in these settings is ideal to establish a cytokine/chemokine-rich environment to support autocrine and paracrine cell motility, EMT and invasion [36]. It could also be speculated that chronic activation of a type I IFN response, as induced in Mic60-low tumors, may contribute to an inflammatory and pro-tumorigenic microenvironment [41], compounding myeloid-directed immunosuppression [42] and propagation of cancer stemness [43]. Such pro-tumorigenic function of chronic IFN signaling may be especially relevant under conditions of mitochondrial dysfunction [44], reminiscent of the ghost mitochondria in Mic60-low tumors.

The fact that Mic60-low tumors stop proliferating is perhaps the second trade-off of the pathway, where energy sources are shifted towards fueling cell movements and invasion at the expense of cell division. A dichotomy between cell proliferation and cell migration is not a new concept in cancer, also called “phenotype switching” [45], or go-or-grow decisions [46]. This describes a dynamic and reversible state, where tumor cells alternate between proliferative and migratory phenotypes depending on quality of environmental conditions. Similar to the Mic60 pathway, recent data have linked phenotype switching to changes in expression of other mitochondrial regulators, including syntaphilin [47] or FUNDC1 [48]. It is possible that go-or-grow decisions may be more common than previously thought, and enhance tumor plasticity to regulate metastatic traits [49].

Finally, it is noteworthy that Mic60-low tumor cells and their ghost mitochondria manage to persist, in vivo, defying cellular suicide programs and escaping quality control mechanisms of mitophagy. The activation of GCN2-ISR signaling in these settings may embody the ideal compensatory response to maintain cell viability [37], adjust metabolism under stress [50], preserve aspects of mitochondrial integrity [51] and oppose cell death [52], while also shutting off cell proliferation via eIF2α phosphorylation. Less straightforward is a role of mitophagy in this response. One of the main mitophagy effectors, Parkin is reduced or even undetectable in most cancers, consistent with a role in tumor suppression [28]. However, a protective function of mitophagy in cancer is far from clear as activation of this process has been implicated in progression of KRAS-driven pancreatic cancer [53] and chemotherapy resistance [54]. Recent data have uncoupled these two processes and suggested that Parkin tumor suppression is independent of mitophagy, leveraging its E3 ligase activity to disrupt mitochondria-regulated cell motility and inhibit tumor bioenergetics produced by the pentose phosphate pathway [55].

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Although there is little doubt that mitochondria are active cancer drivers, their role in disease progression, and, specifically, metastatic competence continues to evolve. What we have learned over the years is that the microenvironment of primary and metastatic tumor growth is extraordinarily complex and chaotic, where hundreds of malignant clones are constantly in competition and cooperation with each other for nutrients, resources, selection of fitness traits and adaptation to ever-changing and mostly unfavorable surroundings [56]. Against this backdrop of stunning heterogeneity, which is one of the central drivers of treatment failure in the clinic, it seems unlikely that the only mitochondrial function exploited in cancer is energy production, also given the pervasive role of hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment.

The Mic60 pathway [29] seems to point to a far more complex landscape of mitochondrial exploitation, one that amplifies “danger signals” originating from degraded, de-energized and ROS-producing ghost mitochondria. The net result is not a restoration of homeostasis. On the contrary, mitochondrial “danger signals” are designed to produce an even more deranged and treacherous cellular phenotype: one that is proliferatively quiescent, and therefore shielded from most anticancer therapies, but highly migratory and invasive with dramatically enhanced metastatic potential. It could be speculated that tumors leverage this pathway as part of their adaptive plasticity [49], titrating Mic60 levels as a stress-regulated switch to enable cell motility and activate the “cancer diaspora” [38].

Major questions with this model remain (see Outstanding questions). Future work will address some of these issues, and it is possible that the deranged and metastasis-prone phenotype created by ghost mitochondria may uncover new therapeutic opportunities. The potential “addiction” to compensatory survival pathways, such as GCN2-ISR, may make Mic60-low tumor cells selectively vulnerable to combination therapies that reactivate cell death while preventing cellular adaptation, especially in advanced and metastasis-prone cancer.

OUTSTANDING QUESTIONS.

How is Mic60 regulated, in vivo, and are there differences in the control of its expression between normal and cancer cells?

Is the deranged phenotype of global cellular stress imposed by ghost mitochondria reversible once environmental conditions improve, potentially enabling resumption of tumor cell proliferation at distant metastatic sites?

Are there other mechanisms aside from Mic60 downregulation, perhaps even exposure to conventional or molecular therapy that can generate ghost mitochondria as relays of “danger signals”?

Are tumor cells “addicted” to the compensatory mechanisms activated by ghost mitochondria, for instance GCN2 and Akt signaling, and can this provide a therapeutic opportunity, especially for advanced cancer, where treatment options remain scarce and not very effective?

HIGHLIGHTS.

Mitochondria are signaling organelles that impact virtually every cellular function

There is now great interest in understanding how mitochondrial functions are exploited in cancer, especially in promoting tumor plasticity and advanced disease traits, such as metastasis

The microenvironment of tumor growth is highly unfavorable to mitochondria as erratic oxygen concentrations, low nutrients, and high oxidative radicals compromise organelle fitness

Loss of mitochondrial fitness is common in cancer creating highly defective, ghost mitochondria that relay “danger signals” of metabolic starvation, oxidative stress, and inflammatory and senescence gene expression

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R35 CA220446 and an award from the Mary Kay Ash Foundation. The author apologizes to all colleagues who contributed to this area of investigation whose work could not be cited for space constraints.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The author declares no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson RG et al. (2018) Mitochondria in cancer metabolism, an organelle whose time has come? Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1870 (1), 96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porporato PE et al. (2018) Mitochondrial metabolism and cancer. Cell Res 28 (3), 265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeBerardinis RJ and Chandel NS (2020) We need to talk about the Warburg effect. Nat Metab 2 (2), 127–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sellers K et al. (2015) Pyruvate carboxylase is critical for non-small-cell lung cancer proliferation. J Clin Invest 125 (2), 687–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sancho P et al. (2016) Hallmarks of cancer stem cell metabolism. Br J Cancer 114 (12), 1305–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBleu VS et al. (2014) PGC-1alpha mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat Cell Biol 16 (10), 992–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chandel NS (2015) Evolution of Mitochondria as Signaling Organelles. Cell Metab 22 (2), 204–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleine T and Leister D (2016) Retrograde signaling: Organelles go networking. Biochim Biophys Acta 1857 (8), 1313–1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen S et al. (2018) Interacting organelles. Curr Opin Cell Biol 53, 84–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes JD et al. (2020) Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell 38 (2), 167–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galluzzi L et al. (2014) Organelle-specific initiation of cell death. Nat Cell Biol 16 (8), 728–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wikstrom M and Springett R (2020) Thermodynamic efficiency, reversibility, and degree of coupling in energy conservation by the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Commun Biol 3 (1), 451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayes JD et al. (2020) Oxidative Stress in Cancer. Cancer Cell. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bock FJ and Tait SWG (2020) Mitochondria as multifaceted regulators of cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21 (2), 85–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Song J and Becker T (2022) Fidelity of organellar protein targeting. Curr Opin Cell Biol 75, 102071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chae YC et al. (2013) Landscape of the mitochondrial Hsp90 metabolome in tumours. Nat Commun 4, 2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caino MC et al. (2016) A neuronal network of mitochondrial dynamics regulates metastasis. Nat Commun 7, 13730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roussos ET et al. (2011) Chemotaxis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 11 (8), 573–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Altieri DC (2019) Mitochondrial dynamics and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci 76 (5), 827–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caino MC and Altieri DC (2016) Molecular Pathways: Mitochondrial Reprogramming in Tumor Progression and Therapy. Clin Cancer Res 22 (3), 540–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveira GL et al. (2021) Cancer cell metabolism: Rewiring the mitochondrial hub. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 1867 (2), 166016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jia D et al. (2018) Elucidating the Metabolic Plasticity of Cancer: Mitochondrial Reprogramming and Hybrid Metabolic States. Cells 7 (3), 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosc C et al. (2017) Resistance Is Futile: Targeting Mitochondrial Energetics and Metabolism to Overcome Drug Resistance in Cancer Treatment. Cell Metab 26 (5), 705–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watson MJ and Delgoffe GM (2022) Fighting in a wasteland: deleterious metabolites and antitumor immunity. J Clin Invest 132 (2), e148549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewhirst MW et al. (2008) Cycling hypoxia and free radicals regulate angiogenesis and radiotherapy response. Nat Rev Cancer 8 (6), 425–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ng MYW et al. (2021) Quality control of the mitochondrion. Dev Cell 56 (7), 881–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senft D and Ronai ZA (2016) Regulators of mitochondrial dynamics in cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol 39, 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardini JP et al. (2017) Parkin and mitophagy in cancer. Oncogene 36 (10), 1315–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh JC et al. (2022) Ghost mitochondria drive metastasis through adaptive GCN2/Akt therapeutic vulnerability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 119 (8), e2115624119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zerbes RM et al. (2012) Mitofilin complexes: conserved organizers of mitochondrial membrane architecture. Biol Chem 393 (11), 1247–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai PI et al. (2017) Drosophila MIC60/mitofilin conducts dual roles in mitochondrial motility and crista structure. Mol Biol Cell 28 (24), 3471–3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedman JR et al. (2015) MICOS coordinates with respiratory complexes and lipids to establish mitochondrial inner membrane architecture. Elife 4, e07739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohnert M et al. (2012) Role of mitochondrial inner membrane organizing system in protein biogenesis of the mitochondrial outer membrane. Mol Biol Cell 23 (20), 3948–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang D and Kim J (2019) Mitochondrial Retrograde Signalling and Metabolic Alterations in the Tumour Microenvironment. Cells 8 (3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Birch J and Gil J (2020) Senescence and the SASP: many therapeutic avenues. Genes Dev 34 (23–24), 1565–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faget DV et al. (2019) Unmasking senescence: context-dependent effects of SASP in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 19 (8), 439–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pakos-Zebrucka K et al. (2016) The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep 17 (10), 1374–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pienta KJ et al. (2013) The cancer diaspora: Metastasis beyond the seed and soil hypothesis. Clin Cancer Res 19 (21), 5849–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caino MC et al. (2013) Metabolic stress regulates cytoskeletal dynamics and metastasis of cancer cells. J Clin Invest 123 (7), 2907–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Radisky DC et al. (2005) Rac1b and reactive oxygen species mediate MMP-3-induced EMT and genomic instability. Nature 436 (7047), 123–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mantovani A et al. (2008) Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 454 (7203), 436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panni RZ et al. (2019) Agonism of CD11b reprograms innate immunity to sensitize pancreatic cancer to immunotherapies. Sci Transl Med 11 (499). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qadir AS et al. (2017) CD95/Fas Increases Stemness in Cancer Cells by Inducing a STAT1-Dependent Type I Interferon Response. Cell Rep 18 (10), 2373–2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lei Y et al. (2021) Elevated type I interferon responses potentiate metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and accelerated aging in mtDNA mutator mice. Sci Adv 7 (22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kemper K et al. (2014) Phenotype switching: tumor cell plasticity as a resistance mechanism and target for therapy. Cancer Res 74 (21), 5937–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hatzikirou H et al. (2012) ‘Go or grow’: the key to the emergence of invasion in tumour progression? Math Med Biol 29 (1), 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caino MC et al. (2017) Syntaphilin controls a mitochondrial rheostat for proliferation-motility decisions in cancer. J Clin Invest 127 (10), 3755–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li J et al. (2020) The mitophagy effector FUNDC1 controls mitochondrial reprogramming and cellular plasticity in cancer cells. Sci Signal 13 (642). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jehanno C et al. (2022) Phenotypic plasticity during metastatic colonization. Trends Cell Biol S0962–8924(22)00079–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tameire F et al. (2019) ATF4 couples MYC-dependent translational activity to bioenergetic demands during tumour progression. Nat Cell Biol 21 (7), 889–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker BM et al. (2012) Protective coupling of mitochondrial function and protein synthesis via the eIF2alpha kinase GCN-2. PLoS Genet 8 (6), e1002760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hu J et al. (2012) Activation of ATF4 mediates unwanted Mcl-1 accumulation by proteasome inhibition. Blood 119 (3), 826–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Humpton TJ et al. (2019) Oncogenic KRAS Induces NIX-Mediated Mitophagy to Promote Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Discov 9 (9), 1268–1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Villa E et al. (2017) Parkin-Independent Mitophagy Controls Chemotherapeutic Response in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep 20 (12), 2846–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Agarwal E et al. (2021) A cancer ubiquitome landscape identifies metabolic reprogramming as target of Parkin tumor suppression. Sci Adv 7 (35). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zahir N et al. (2020) Characterizing the ecological and evolutionary dynamics of cancer. Nat Genet 52 (8), 759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]