Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases, featured by progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, are considered incurable at present. Movement disorders like tremor and postural instability, cognitive or behavioral disorders such as memory impairment are the most common symptoms of them and the growing patient population of neurodegenerative diseases poses a serious threat to public health and a burden on economic development. Hence, it is vital to prevent the occurrence of the diseases and delay their progress. Vitamin D can be transformed into a hormone in vivo with both genomic and non-genomic actions, exerting diverse physiological effects. Cumulative evidence indicates that vitamin D can ameliorate neurodegeneration by regulating pertinent molecules and signaling pathways including maintaining Ca2+ homeostasis, reducing oxidative stress, inhibiting inflammation, suppressing the formation and aggregation of the pathogenic protein, etc. This review updates discoveries of molecular mechanisms underlying biological functions of vitamin D in neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and vascular dementia. Clinical trials investigating the influence of vitamin D supplementation in patients with neurodegenerative diseases are also summarized. The synthesized information will probably provoke an enhanced understanding of the neuroprotective roles of vitamin D in the nervous system and provide therapeutic options for patients with neurodegenerative diseases in the future.

Keywords: Vitamin D, Neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Multiple sclerosis

Abbreviations: VDR, vitamin D receptors; VDBP, vitamin D binding protein; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PD, Parkinson’s disease; MS, multiple sclerosis; VaD, vascular dementia; SVD, small vessel disease

1. Introduction

Vitamin D is a kind of fat-soluble steroid vitamin which was discovered in the late 1800s when England was suffering an epidemic of rickets because ultimately the patients were found to be a result of reduced Ca2+ levels related to vitamin D deficiency [1]. And now, the problem of vitamin D deficiency still exists all over the world. It has been reported that half of the people across the world lacked vitamin D to different degrees and more than 1 billion people were suffering from vitamin D deficiency [2]. More importantly, except for bone-related diseases, subsequent findings suggest that vitamin D deficiency is related to many other human diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS) and vascular dementia (VaD), as well as cancer, cardiovascular disease, immunity disease, etc [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]].

Overlapping pathologies are shared by many neurodegenerative diseases, such as oxidative stress, inflammation, protein aggregation, and demyelination [12]. In recent years, the effects of vitamin D on the nervous system have been receiving increasing attention. Many vitamin D-related enzymes and vitamin D receptors (VDRs) are widely presented in the brain, and the metabolites of vitamin D could interact with neuronal and glial cells to exert various effects [[13], [14], [15]]. Vitamin D has been shown to ameliorate neuropathological features and vitamin D supplementation contributes to a better prognosis [16]. In this review, we will discuss the relationship between vitamin D and some neurodegenerative diseases and present possible mechanisms through which vitamin D affects the occurrence and development of these diseases as well as clinical applications of vitamin D in the diseases.

2. Biosynthesis and metabolism of vitamin D

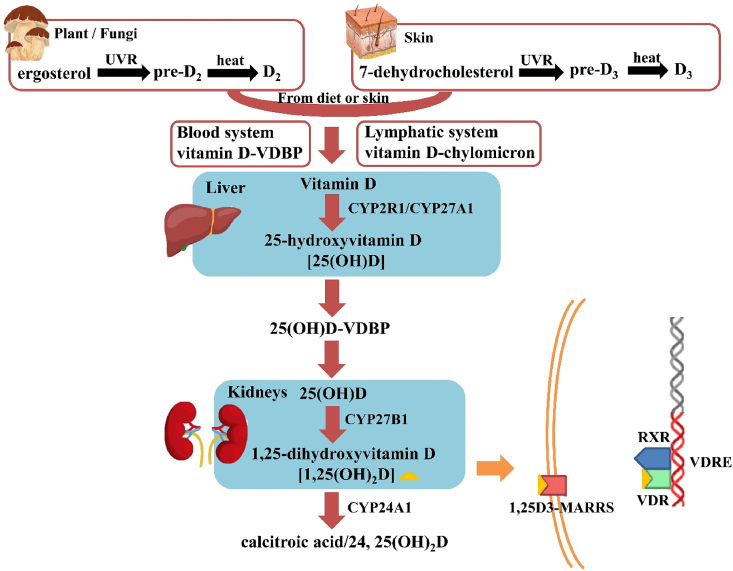

Vitamin D exists in nature in two major forms, vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol) and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol). Vitamin D3 is mainly produced in animal skin from 7-dehydrocholesterol (7-DHC) while vitamin D2 is synthesized in plants and fungi from ergosterol (E) by ultraviolet rays (UVR) irradiation. The synthesis of them is similar, containing two processes that are not enzymatic. First, the B ring in E/7-DHC is broken by the UVR (290–315 nm) irradiation, and E/7-DHC converts to pre-D2/D3, an isomer of vitamin D2/D3. Then, through a thermo-sensitive process, pre-D2/D3 finally isomerizes to vitamin D2/D3 (Fig. 1) [1,17].

Fig. 1.

The biosynthesis, metabolism, and mechanism of action of vitamin D. VDBP, vitamin D binding protein; RXR, retinoid X receptor; VDR, vitamin D receptor; 1,25D3-MARRS, 1,25D3 membrane-associated rapid-response steroid-binding protein; VDRE, vitamin D-responsive elements.

For humans, most vitamin D is produced in the skin by the irradiation of UVR and only 20% of vitamin D is ingested diet [18]. Most vitamin D enters the blood circulation and binds to vitamin D binding protein (VDBP) or chylomicron to be transported to tissues and organs. The metabolism of vitamin D includes three main processes, which are 25-hydroxylation, 1α-hydroxylation, and 24-hydroxylation [17]. The first conversion of vitamin D is in the liver, where it is hydroxylated on C-25 by the enzymes cytochrome P450 2R1 (CYP2R1) and cytochrome P450 27 (CYP27A1) forming 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D], a major type of circulating metabolite of vitamin D. 25(OH)D is mainly transported to the kidney by VDBP and starts the second hydroxylation at the C1-position by the cytochrome P450 [5(OH)D-1α-hydroxylase; CYP27B1]. This process yields 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1,25(OH)2D], a biologically active form of vitamin D, which is also named calcitriol. The third process, 24-hydroxylation catalyzed by 24-hydroxylase (CYP24A1), participates in vitamin D3 inactivation (Fig. 1) [1,19]. Therefore, the functions of vitamin D we synthesize below are actually implemented by calcitriol.

3. Mechanism of action and functions of vitamin D

Vitamin D receptor (VDR) is a DNA-binding transcription factor and a member of the steroid hormone nuclear receptor family, which is expressed and distributed in almost all tissues and organs in the human body [17,[20], [21], [22]]. 1,25(OH)2D binds to VDR by its ligand-binding domain with the assistance of vitamin A to induce a change in conformation, forming a heterodimer with retinoid X receptor (RXR), which binds to vitamin D-responsive elements (VDREs) and starting gene transcription [[23], [24], [25], [26]]. More recently, the 1,25D3 membrane-associated rapid-response steroid-binding protein (1,25D3-MARRS), activated by calcitriol [1,25(OH)2D3], was also identified (Fig. 1) [27].

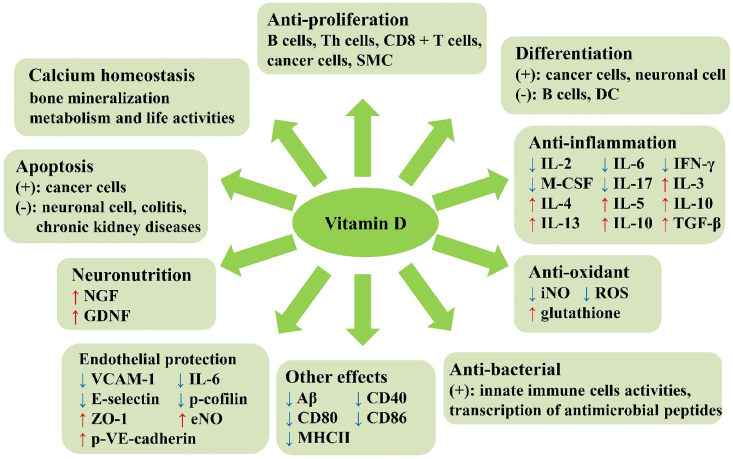

The classic effect of vitamin D is associated with bone [28]. Vitamin D can promote the absorption of calcium and phosphorus, maintaining calcium homeostasis in order for proper mineralization of bone. Several surveys found that vitamin D supplementation could reduce the incidence of hip fractures and other non-vertebral fractures [[29], [30], [31]]. Besides, vitamin D can also sustain muscle function and enhance postural and dynamic balance. A meta-analysis published in 2004 found that vitamin D supplementation could reduce the risk of falls by over 20% in ambulatory or institutionalized older individuals with stable health [32].

Vitamin D also plays an important role in the immune system. Calcitriol could strengthen the antimicrobial effects by enhancing the chemotaxis and phagocytic capabilities of innate immune cells and the transcription of antimicrobial peptides in them [33]. In macrophages or monocytes, vitamin D induces the production of antibiotic peptides, such as cathelicidin and β-Defensin 2 [34,35]. Vitamin D increases transcription of the autophagy-associated proteins Atg-5, and Beclin-1, which promote autophagy through the upregulation of cathelicidin and their downstream factors (p38, ERK, and C/EBP) [36]. Vitamin D could suppress dendritic cells (DC) to express MHCII, co-stimulatory molecules, and cytokines essential for T cells differentiation and inhibit the activity of T helper cells (Th) and its production of cytokines like interleukin-17 (IL-17) and IL-21 [33,37,38]. Furthermore, vitamin D could either directly repress naïve B cell differentiation, memory B, and plasma cells maturation or indirectly suppress B cell differentiation, proliferation, and antibody production via Th cells [39].

Vitamin D could also regulate the differentiation, proliferation of neurons and microglia, and dopamine signaling transduction [13,40]. The effects of vitamin D, including regulating synaptic plasticity and molecular transport in cell organelles, and maintaining cytoskeleton, are sufficiently proved, which implies the important roles of vitamin D in brain development and synaptic plasticity [13,41,42]. Calcitriol could restore calcium homeostasis and reduce apoptosis and neuronal death by downregulating the expression of L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channel (LVCC) while upregulating the expression of plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase (PMCA) and Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1) that efflux Ca2+ and Calbindin D-9k, Calbindin D-28k, as well as parvalbumin that buffer Ca2+ [16,43,44]. Besides, vitamin D sustains normal functions of mitochondria thus reducing the formation of ROS, and controlling the expression of antioxidants through the vitamin D–Klotho–Nrf2 regulatory network [45]. Vitamin D assists in anti-oxidation by up-regulating the expression of glutathione and superoxide dismutase and down-regulating the expression of nitric oxide (NO) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [[46], [47], [48]]. Moreover, vitamin D enhances neuronal survival by regulation of neurotrophins, including neural growth factor (NGF), glial-line derived neurotrophic factors (GDNF), and brain derived neurotrophic factors (BDNF) [40,49,50]. The synthesis of neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine (ACh), dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT), and gamma-aminobutyric (GABA) is also under the control of vitamin D [[51], [52], [53], [54]]. Vitamin D could protect neurons by altering glutamate levels and reducing excitotoxicity caused by long-term increases in extracellular glutamate levels and hyperactivation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) [55].

Other functions of vitamin D, including inhibiting inflammation and smooth muscle cells proliferation, may also play roles in cardiovascular diseases and neurodegenerative diseases [[56], [57], [58]]. In various cancers, vitamin D has been found to exert its effects through inhibition in proliferation, inflammation, angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis, induction of differentiation, and promotion of cell apoptosis [59]. Further, vitamin D plays an anti-apoptosis role through Caspase-3, Bcl-2, and other probable mechanisms in many other diseases (Fig. 2) [[60], [61], [62]].

Fig. 2.

The functions of vitamin D. ↑: up-regulate; ↓: down-regulate; +: positive influence in; -: negative influence in. DC, dendritic cells; Th, T helper; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; GDNF, glial-line derived neurotrophic factors; SMC, smooth muscle cells; Aβ, beta-amyloid; P-gp, P-glycoprotein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; eNO, endothelial NO; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; VE-cadherin, vascular endothelial cadherin; M-CSF, macrophage colony stimulating factor; IL, interleukin; ZO-1, zonula occludin-1.

4. Effects and molecular mechanisms of vitamin D in neurodegenerative diseases

4.1. Vitamin D and Alzheimer’s disease

As a major kind of neurodegenerative disease, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) has a growing patient population in the world [63]. AD is the main cause of dementia [64]. At present, almost 48 million people are suffering from dementia and this population is increasing at the speed of about 10 million every year around the world [63,65]. Initial symptoms include short-term memory loss, and as the disease advances, other symptoms, such as problems with language, disorientation, and mood swings, would ensue [66]. The major neuropathological features of AD include the accumulation of extracellular senile plaques consisting of beta-amyloid (Aβ) protein aggregates, intra-neuronal neurofibrillary tangles made up of tau protein, and loss of cholinergic neurons and synapses in the cerebral cortex and certain subcortical regions [67,68]. Besides, neuroinflammation was also proved to promote AD pathogenesis [69].

Vitamin D deficiency could be a risk factor for AD [70]. A meta-analysis conducted in 2019 found that vitamin D deficiency (<10 ng/mL) has a positive correlation with the risk of AD and every 10 ng/mL supplement of vitamin D could reduce the risk of AD by 17%, while these associations were not found in vitamin D insufficiency (10–20 ng/mL) [71]. It has been found in a mouse experiment that a deficiency of vitamin D in the early stage of AD could increase the amyloid load in the hippocampus and the cortex and strongly inhibit cell proliferation, neurogenesis, and neuron differentiation in both wild-type and transgenic AD-like mice (5XFAD model) in the late stage [72]. All evidence presented above proves that vitamin D deficiency could enhance the development of AD.

Contrarily, supplements of vitamin D may prevent or inhibit the development of AD (Table 1). It has been found that vitamin D supplements could improve the cognition of young amyloid-β protein precursor (AβPP) transgenic mice and maintain memory abilities of old transgenic mice or aging rats [18,73]. Loads of evidence supports the positive effect of vitamin D in reducing Aβ accumulation, but some findings with the opposite conclusion also exist. In an animal experiment, vitamin D could decrease the formation of Aβ and increase the degradation of Aβ [74]. However, a recent study showed a contradictory result that vitamin D supplementation increased Aβ deposition and aggravated AD. The explanation is that Aβ42 in the AD brain switched VDR binding target from RXR to p53 to transduce the non-genomic vitamin D signal [75]. In humans, vitamin D could increase the level of the β amyloid peptide Aβ1–40 in serum and decrease the level of Aβ in the brain, inhibiting amyloidogenesis [76]. Some researchers put forward probable mechanisms. 1α,25(OH)2D 3 could stimulate macrophages to devour Aβ in AD patients [77]. The activation of VDR could inhibit the phosphorylation of tau probably by decreasing the activity of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) in APP/PS1 transgenic mice [78]. VDR overexpression or vitamin D supplement was found to inhibit the transcription of amyloid precursor protein (APP) [79]. Moreover, a vitamin D analog, maxacalcitol, could decrease the level of Aβ and hyperphosphorylated Tau protein by down-regulating the level of MAPK-38p and ERK1/2 [80]. In addition, vitamin D can act on calcium channels and upregulate the expression of calcium buffer to maintain calcium homeostasis, breaking the Aβ/Ca2+ positive feedback loop, increasing neuronal excitability, and promoting cell proliferation and neurogenesis [81–84].

Table 1.

Vitamin D and Alzheimer’s disease.

| Model (duration of the disease) | Strain and/or age | Supplement | Dose | Cognition/memory test | Effects | Signaling Pathway or molecule | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tg2576 and TgCRND8 mouse models of AD (chronic) | C57BL/6 mice; 8-week-old | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 2.5 μg/kg, q2d × 4 or q3d × 19 | Fear conditioning | Improved memory | NA | [73] |

| Reducing Aβ in the brain | VDR, P-gp | ||||||

| Vitamin D deficient mice (chronic) | C57BL/6 mice; age not obtained | Calcifediol or its analogues | 100 nM | NA | Reducing amyloid plaques | α-secretase/β-secretase/γ- secretase/BACE1 | [74] |

| APP695 overexpressing human and mice neuroblastoma (NA) | SH-SY5Y; N2a | vitamin D3/vitamin D2/vitamin D3 analogues/vitamin D2 analogues | 100 nM | NA | Inhibiting Aβ formation; increasing Aβ degradation | ||

| APP/PS1 tg mice (chronic) | Strain not obtained; 6-month old | Paricalcitol | 200 ng/kg, q2d, 15 weeks | NA | Inhibiting Tau phosphorylation | GSK3β | [78] |

| Mice neuroblastoma with overexpression of VDR or vitamin D treatment (NA) | N2a | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 0.02, 0.2 and 2 μM |

NA | Inhibiting Aβ formation | APP | [79] |

| AD rats induced by LPS (acute) | Female white albino rats; 6 months-1 year old | Maxacalcitol | 1 μg/kg, tid, 4 weeks | T-maze test | Inhibiting Aβ formation and Tau phosphorylation | MAPK-38p/ERK1/2 | [80] |

| APP/PS1 tg mice (chronic) | C57BL/6 N mice; 4.5 months old | Cholecalciferol | 8044 IU/kg/day, 3 months | Morris water maze test | Worse cognitive function; more severe Aβ deposit | Aβ/BACE1/Nicastrin | [75] |

| Human neuroblastoma pretreated with Aβ42 (NA) | SH-SY5Y | Calcitriol | 10, 30, or 100 nM | NA | Promoting apoptosis and autophagy | VDR/PARP/LC3-1/LC3-II | [75] |

| VDR-silenced neurons (NA) | Primary cortical neurons from Sprague-Dawley rat embryos | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 10−7/10−8/10−9 M | NA | Maintaining calcium homeostasis; inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress | LVSCC-A1C/NO/TNF-α/IL-6 | [81] |

| Aged male rats (chronic) | F344; 3–4 months and 24–25 months | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 500 ng/kg, 6 days | NA | Maintaining calcium homeostasis | L-VGCC | [82] |

| Neurons treated with 1,25 (OH)2D3 (NA) | Hippocampal neurons from Sprague Dawley fetal rat | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 1–100 nm | NA | Maintaining calcium homeostasis | L-VSCC | [83] |

| Human brain pericytes | NA | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 10−8 M | NA | Inhibiting inflammation | TNF-α/IFN-γ | [85] |

| Mice exposed to oxidative stress AD pathology induced by D-gal (subacute) | Male adult albino mice; 8 weeks old | Vitamin D | 100 μg/kg, 3 times/week, 4 week | Morris water maze and Y-maze tests | Improving memory dysfunction | NA | [86] |

| Enhancing pre- and post- synaptic protein expression; reducing inflammation | SYP/PSD-95 | ||||||

| Inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress | NF-kB/TNF-α/IL-1β/SIRT1/NRF-2/HO-1 | ||||||

| Inhibiting Aβ formation | BACE-1 | ||||||

| Rats with AD induced by LPS (acute) | Female white albino rats; 6 months-1 year | Maxacalcitol | 1 μg/kg, tid, 4 weeks | T-maze test | Improvement of the cognitive functions of the brain of Maxacalcitol treated rats | NA | [80] |

| Inhibiting oxidative stress | Nrf2/HO-1/GSH | ||||||

| Human and murine kidney cells treated with 1,25 (OH)2D3 (NA) | mpkDCT, HEK, IMCD-3, HK-2, COS-7 | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 10 −8 M | NA | Anti-aging | Klotho | [87] |

| Neurons treated with 1,25 (OH)2D3 (NA) | Embryonic hippocampal cells | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 100 nM | NA | Promoting neurite growth | NGF | [91] |

P-gp, P-glycoprotein; SYP, Synaptophysin; PSD-95, post synapse density 95; NF-kB, Nuclear Factor kappa B; SIRT1, Silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1; NRF-2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; BACE-1, beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme-1; LVCC, L-type voltage-sensitive calcium channel; PMCA, plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase; NCX1, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; GDNF, glial-line derived neurotrophic factors; BDNF, brain derived neurotrophic factors; NGF, neural growth factor; AchACh, acetylcholine; DA, dopamine; 5-HT, serotonin; GABA, gamma-aminobutyric; NMDAR, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor; Aβ, beta-amyloid; AβPP, amyloid-β protein precursor; GSK3β, glycogen synthase kinase 3β; APP, amyloid precursor protein; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; D-gal, d-Galactose; Nrf2, erythroid2-related factor 2; HO-1, heme oxygenase-1; GSH, glutathione; Tg, transgenic; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NA, not applicable.

Anti-inflammation and reducing oxidative stress are also benefits of vitamin D in AD. It was found that 1,25(OH)2D3 possesses anti-inflammation quality in brain pericytes by influencing the transcription process, which means vitamin D could direct protective effect in brain capillaries under the situation of chronic inflammation happened in AD [85]. Moreover, vitamin D could prevent the up-regulation of iNOS, NO, and other proinflammatory factors like tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 in damaged neurons, microglia, and astrocytes [18,46,81]. Another study also found that vitamin D could reduce oxidative stress through SIRT1/Nrf-2/NF-kB signaling pathway, restore the level of neuronal synapse protein and decrease the formation of Aβ induced by d-Galactose (D-gal) in adult mice [86]. Maxacalcitol could be beneficial to AD via its antioxidant effect by increasing the level of nuclear factor erythroid2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and glutathione (GSH) [80]. The anti-aging effect of vitamin D is also involved in AD, by increasing the expression of an anti-aging gene Klotho, as well as decreasing the expression and inhibiting the activity of aging-related protein mTOR, through PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [87,88]. Besides, calcitriol can also up-regulate the expression of NGF and GDNF to influence neuronal cell differentiation and maturation, promoting learning and memory process through the septohippocampal pathway [89–91].

4.2. Vitamin D and Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is also a common neurodegenerative disease with which patients show motor system problems including rigidity, tremor, postural instability, and slow movement, while non-motor symptoms entail sleep disorder, anosmia, constipation, and depression [92,93]. More than 6 million individuals were diagnosed with PD around the world in 2015 [94]. The characteristics of PD are dopamine (DA) neurons loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), insoluble cytoplasmic protein inclusions accumulation called Lewy bodies, and Lewy neuritis [95]. The specific pathogenesis of PD is not clear yet but it is widely recognized that α-synuclein (α-Syn) protein is the core of pathogenesis of the disease [95]. α-Syn aggregation is cytotoxic, causing cellular damage and dysfunction [96,97].

Deficiency or insufficiency of vitamin D is common in PD patients and vitamin D insufficiency in serum [25(OH)D < 30 ng/mL] increases the risk of PD [98]. On the contrary, vitamin D supplement and sunlight exposure (≥15 min/week) was found to be a preventive measure for PD [99]. In the aspect of balance, a review showed that a high dose of vitamin D may improve balance and postural equilibrium and reduce the occurrence of falls only in young PD patients rather than elderly PD patients [100]. Besides, a high level of serum vitamin D is associated with better cognition in PD patients without dementia. Few studies showed that vitamin D was associated with mood and olfactory function in PD [100]. However, some studies obtained contradictory results. A prospective cohort study with a 17-year follow-up period proposed that there was no correlation between vitamin D levels and the risk of PD [101]. Another Mendelian randomized study, involving 4 single-nucleotide polymorphisms which affect 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations, also showed no clear support for the relationship between vitamin D and PD onset [102].

The effects of vitamin D on PD may be achieved through the following mechanisms (Table 2). In a PD preclinical animal model induced by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), vitamin D treatment is beneficial in alleviating dopaminergic neurodegeneration and attenuating neuroinflammation mediated by microglia through down-regulating the expression of iNOS and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) and up-regulating the expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, IL-4, and TGF-β) mRNA, as well as CD163, CD206 and CD204 [103]. The effect of restoring calcium homeostasis could also be beneficial in PD since SNc neurons are more prone to be damaged by Ca2+ and oxidative stress which is caused by the repeated rises in Ca2+ occurring every few seconds when the dopaminergic neuronal pacemaker mechanism is functioning [84]. Vitamin D also could reduce the cytotoxicity caused by α-synuclein aggregation in the early state by down-regulating the production of ROS. Cell death and apoptosis might result from the inhibition of α-Syn aggregation for strong affinity energy to α-Syn monomer [96]. What’s more, vitamin D could also decrease the exocytotic release of neurotransmitters raised by α-Syn oligomers, indicating the neuroprotective effect of vitamin D in PD [96]. In the 6-OHDA PD mouse model, 1,25(OH)2D3 pretreatment could prevent neuroinflammation and the loss of dopamine cells induced by oxidative stress and increase the transcription of VDR, CYP24, and MDR1a which encodes a membrane transporter P-gp mainly expressed in vascular endothelial cells [104]. Besides, vitamin D could directly up-regulate the expression of C-Ret which is a multifunctional receptor vital for GDNF signaling in DA neurons, and increase the expression of GDNF which is important for the survival of DA neurons [40]. It has been proved that the activation of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) which contributes to the pathogenesis of PD in MPTP model, can be inhibited by overexpression of VDR [105,106]. Another experiment also found that over-expression of VDR could increase the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), catechol-o-methyl transferase (COMT), monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), and vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) which can influence the differentiation of DA neurons [107].

Table 2.

Vitamin D and Parkinson’s disease.

| Model/Patients (duration of the disease) | Strain and/or age | Supplement | Dose | Behavioral test | Effects | Signaling Pathway or molecule | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPTP induced PD model in mice (acute) | Male C57BL/6 N mice; 8–10 weeks | Vitamin D | 1 μg/kg/day, 10 d | NA | Inhibiting neuroinflammation | iNOS/TLR-4/IL-10/IL-4/TGF-β/CD163/CD206/CD204 | [103] |

| Human neuroblastoma cells incubated with α-Syn monomer solution (NA) | SH-SY5Y | Vitamin D | 4 μM | NA | Inhibiting α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity | α-Syn monomer | [96] |

| 6-hydroxydopamine -induced PD mouse (acute) | Male C57BL/6 N mice; 3 months | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 2.56 μg/kg, q2d × 4 | NA | Inhibiting α-synuclein aggregation and toxicity | P-gp | [104] |

| Developmental vitamin D-deficient rat model (chronic) | Embryonic forebrains of Sprague-Dawley rats at E18 | Calcitriol | 0 IU/kg | NA | Differentiation and maintenance of dopaminergic neurons | C-Ret | [40,108] |

| Neuroblastoma cells transfected with VDR (NA) | SH-SY5Y | Calcitriol | 20 nM | NA | Differentiation and maintenance of dopaminergic neurons | C-Ret/GDNF/GFRα1 | [40] |

| PD cell model induced by MPP+ (NA) | SH-SY5Y | Calcitriol | 25–75 nM | NA | Protecting SH-SY5Y cells from Parthanatos | PARP1/AIF/phosphor-histone H2A.X | [105] |

| PD mice model induced by MPTP (subacute) | C57/BL6 mice; 8 weeks | Calcitriol | 2.5 μg/kg/day, i.p, for 21 days | Rotarod Testing; Pole Testing | Alleviated PD-related behavioral damage | NA | [105] |

| Alleviating behavioral and dopaminergic neuron damage | VDR/PARP1 | ||||||

| Over-expression of VDR in neuroblastoma cells (NA) | SH-SY5Y | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 20 nM | NA | Promoting neuronal development and maturation | TH/COMT/MAO-A/VMAT2 | [107] |

| Dopaminergic neurons (NA) | Embryonic ventral midbrain of Sprague-Dawley rats at E12/E13 | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 10 nM | NA | Neuronutrition | GDNF | [90] |

Α-Syn, α-synuclein; PARP1, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1; TH, tyrosine hydroxylase; COMT, catechol-o-methyl transferase; MAO-A, Monoamine oxidase A; VMAT2, vesicular monoamine transporter 2; i.p, intraperitoneal injections; NA, not applicable.

4.3. Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a central nervous system (CNS) disease with chronic inflammation and degenerative process mediated by the immune system [109]. Approximately 2.3 million people were affected by the disease worldwide in 2015 [110]. MS is regarded as an autoimmune disease because it is initiated by immune cells passing through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and abnormal immune responses, causing demyelination and damage to neuroaxonal in the brain, retina, and spinal cord [111,112].

In general, the prevalence of MS shows latitude-related differences. Notably, MS has a minimal prevalence at the equator, implying the correlation between vitamin D and MS [113]. It is recognized that vitamin D is a risk factor for MS [114]. In a study with only whites included, it was found that people with the highest concentrations of vitamin D had a 62% lower risk of developing MS than people with the lowest concentrations [115]. Low levels of serum vitamin D in the early stage of MS predict a more active disease process [116]. Besides, in animal experiments, high levels of serum vitamin D have effects on preventing, improving the symptoms, and inhibiting the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [111]. Moreover, continuous moderate vitamin D supplements also could reduce the rate of recurrence [114].

Since MS is an autoimmune disease, the effects of vitamin D related to the immune system may also influence the disease (Table 3). Vitamin D could suppress the activity of Th1 and Th17 by down-regulating the level of Jak1/Jak2, Erk/MAPK, Pi3K/Akt/mTOR, Stat1/Stat4, and Stat3, which are important for the differentiation of Th1 and Th17, decreasing the secretion of many inflammatory cytokines including IL-2, IL-6, IFN-γ, macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and IL-17 in EAE model, while enhancing the activity of Th2 and induce the response of regulatory T-cell (Treg), up-regulating the level of IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, IL-13, IL-10 and TGF-β [117,118]. An animal experiment found that calcitriol could suppress neuroinflammation by decreasing the expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, and IL-1β local mRNA, stabilizing BBB by increasing the mRNA expression of zonula occludin-1 (ZO-1), a junctional adaptor protein controlling the formation of BBB, and reducing the activation of local macrophage and microglia and mediate autoimmune response by decreasing the level of MHCII in EAE animal model [119]. Besides, the proliferation of B cells, Th cells, and CD8 + T cells and the differentiation of B cells and DC are inhibited by vitamin D while the amount of Treg increases [39,117,120,121]. Vitamin D could also down-regulate the expression of co-stimulatory molecules, such as CD40, CD80, and CD86 causing a VDR-dependent loss of MHCII in monocytes [120,122]. Furthermore, an animal study found that vitamin D could up-regulate the level of Bcl-2/Bax and Beclin 1 which reduces LC3-II, leading to inhibited apoptosis and autophagy in EAE mouse model, dampening the progression of EAE [123]. Except for the effects on the immune system, vitamin D could also act in CNS, mediating neuroprotection, neurotrophic effect, and remyelination [114].

Table 3.

Vitamin D and multiple sclerosis.

| Model/Patient (duration of the disease) | Strain and/or age | Supplement | Dose | Clinical assessment | Effects | Signaling Pathway or molecule | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAE mice model (acute) | Dark Agouti rats; age not obtained | Vitamin D3 | 10 IU/g | 0 = no paralysis; 1 = loss of tail tone; 2 = hindlimb weakness; 3 = hindlimb paralysis; 4 = hindlimb and forelimb paralysis; 5 = moribund or dead |

Alleviating in clinical symptoms | NA | [118] |

| Immunomodulation and anti-inflammation | Jak1/Jak2, Erk/Mapk, Pi3K/Akt/mTor, Stat1/Stat4, Stat3 | ||||||

| EAE mice model (acute) | C57BL/6J female mice; 9 weeks old | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 5 μg/kg, every 2 days | Alleviating in clinical symptoms and inhibiting progressing | NA | [119] | |

| Immunomodulation and anti-inflammation | NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β/ZO-1/MHCII | ||||||

| EAE mice model (acute) | C57BL/6J female mice; 8–10 weeks | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 0.1 μg/day, every 3 days | Alleviating in clinical symptoms and inhibiting progressing | NA | [123] | |

| Reducing inflammation, demyelination, and neuron loss in the spinal cord | Bcl-2/Bax/Beclin 1/LC3-II | ||||||

| EAE mice model (acute) | C57BL/6J female mice; age not obtained | Vitamin D3 | 75,000 IU/kg food | Alleviating in clinical symptoms | NA | [124] | |

| Triggering MS activity by attenuating phenotype and function of myeloid APC development of pro-inflammatory T cells and accelerated activation and differentiation of both myeloid APC and T cells | IFN-γ/IL-17/MHC II/CD40/CD80/CD86 |

JAK, Janus Kinase; Erk, extracellular regulated protein kinases; Mapk, mitogen-activated protein kinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NLRP, Nod-like receptors protein; EAE, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.

4.4. Vitamin D and vascular dementia

Vascular dementia (VaD) is the most common type of dementia second only to AD, caused by infarcts in the brain [125,126]. Cognitive, motor, and behavioral dysfunction can be signs of VaD, including cognitive decline, memory impairment, hemiparesis, bradykinesia, hyperreflexia, extensor plantar reflexes, ataxia, pseudobulbar palsy, gait problems, and dysphagia [127]. The pathology of VaD involves diffuse and focal white matter lesions, lacunar and microinfarcts, intracerebral microbleeds, cerebral amyloid angiopathies, and familial small vessel diseases [[128], [129], [130], [131], [132]]. For chronic hypoperfusion induced VaD, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and central cholinergic dysfunction are its pathophysiological features [133].

In VaD patients, vitamin D deficiency was more common than in normal people [134]. It was found that a low level of vitamin D could increase the risk of VaD, while a recent study showed that higher level of vitamin D could reduce the risk of VaD [134,135]. In an animal experiment, vitamin D could reduce the amount of induced infarction in the cortex in vivo [136]. Besides, in a cross-sectional study of 318 elderly adults, vitamin D deficiency may result in a greater number of large vessel infarcts, which are associated with a higher risk of VaD [137]. In addition, VDR polymorphism is suggested to relate to VaD which could be caused by small vessel disease (SVD). In an Asian India cohort study, it was found that the presence of “ff” genotype of FokI variant increased the odds of SVD by 2.5 folds in subjects with low serum 25(OH)D and ApaI polymorphism decreased the risk of cerebral SVD in women [134].

The probable effects of vitamin D in VaD mainly include two aspects, vascular and nerves (Table 4). Vitamin D could inhibit the influx of calcium into the endothelial cells and decrease the release of vasoconstrictor metabolites to induce vasodilatation in the microcirculation [138]. Vitamin D could also directly up-regulate the expression of the endothelial form of NOS (eNOS) and increase the production of endothelial NO (eNO), inhibiting platelet aggregation and endothelial dysfunction [139,140]. Vitamin D attenuates cerebral artery remodeling and vasospasm through the upregulation of osteopontin (OPN) and phosphorylation of AMPK and eNOS in the cerebral arteries [141]. What’s more, vitamin D could decrease the level of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), cytokine IL-6, and E-selectin, reducing the adhesion of endothelial cells [142]. Vitamin D counteracts inflammation in endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFC) involved in angiogenesis and endothelial repair by increasing endothelial interconnections through vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) junctions and impacting cell dynamics through cofilin and VE-cadherin phosphorylation, contributing to an improvement in endothelial barrier integrity [143]. Vitamin D also could prevent hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced BBB disruption by NF-κB pathway and diminish the response of endothelial cells to inflammatory cytokines, reducing brain injury [144]. It was also proposed a conjecture that vitamin D could inhibit the proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells (SMC) [145]. The mechanisms mentioned above could prevent the development of atherosclerosis, which is a pathogenic factor of VaD [146]. In the presence of vitamin D, NO could activate phospholipase A2 in the astrocytes, triggering the prostaglandin cascade, widening the arteries, and the expression of ACh and vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) increases, amplifying the process [147]. An animal experiment conducted with VDR −/− mice showed that without the existence of VDR, the progress of atherosclerosis was accelerated and promoted [148]. In terms of neurons, vitamin D could mediate neuroprotection and the improvement in neurogenesis, cell proliferation and differentiation, and neurotransmitter metabolism, which are similar to other neurodegenerative diseases [149].

Table 4.

Vitamin D and vascular dementia.

| Model/Subject (duration of the disease) | Strain and/or age | Supplements | Dose | Behavioral test | Effects | Signaling pathway | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin D deficient rat model (chronic) | Male Sprague Dawley; 10 weeks | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 0.15 μg/kg, 4 weeks | NA | Vitamin D deficiency impaired microvascular vasodilation. Calcitriol supplementation improves endothelium-dependent contraction | eNOS | [139] |

| Healthy college-aged Africa-Americans (NA) | 18–30 years | Oral vitamin D | 2000 IU/day, 4 weeks | NA | Promoting microvascular function | eNO | [140] |

| Endovascular perforation SAH model in Sprague-Dawley rat (acute) | Male Sprague Dawley; 10 weeks | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 30 ng/kg, 24 h | Spontaneous activity, spontaneous movement of all limbs, vibrissae touch, forelimbs outstretching, and climbing wall of cage | Improves neurological deficits | NA | [141] |

| Reducing cerebral artery remodeling and vasospasm | OPN/AMPK/eNOS | ||||||

| Patients with metabolic syndrome (NA) | 30–50 years; (BMI) < 40 kg/m2 | Vitamin D | 50,000 IU/week, 16 weeks | NA | Inhibiting atherosclerosis | VCAM-1/IL-6/E-selectin | [142] |

| Endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFC) pretreated with 1α,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3 (NA) | NA | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 0.1/10 nM, 24 h | NA | Vasoprotective, neovasculogenic and anti-inflammation effects | VE-cadherin/cofilin | [143] |

| Immortalized mouse brain endothelial cells exposed to different vitamin D3 concentrations | bEnd.3 | 1,25 (OH)2D3 | 0/5/20/200 nmol/L | NA | Protection against ischemic injury-induced BBB dysfunction in cerebral endothelial cells | NF-κB | [144] |

| Atherosclerosis induced by high fat-high cholesterol (HFHC) diet and water containing 2 mM CaCl2 LDLR−/−/VDR−/− mice, Rag-1−/−/VDR−/− mice | C57BL/6 mice; 8 weeks | NA | NA | NA | Inhibiting atherosclerosis | MCP-1/IL-1β/IFN-γ/matrix metalloproteinase 9/renin/ICAM-1/E-selectin/VDR | [148] |

eNO, endothelial NO; OPN, osteopontin; AMPK, Adenosine 5′-monophosphate activated protein kinase; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; VE-cadherin, vascular endothelial cadherin; OPN, osteopontin; NF-kB, Nuclear Factor kappa B; ICAM, intercellular cell adhesion molecule; NA, not applicable; SAH:subarachnoid hemorrhage.

5. Clinical application of vitamin D in neurodegenerative diseases

The beneficial effects of vitamin D in neurodegenerative diseases have been widely studied in cellular and animal experiments. There are also some clinical trials and case reports about the effects of vitamin D in some neurodegenerative diseases. The specific information of them is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Clinical studies including the effects of vitamin D in AD, PD, and MS patients.

| Design | Subjects | Supplement | Dose | Assessment | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R, DB, PC | 210 AD patients (age: over 65 years) | Vitamin D3 | 800 IU/day for 12 months | WAIS-RC, ADL, MMSE | Significantly improvement in cognitive function | [150] |

| R, PC | 32 mild-moderate AD patients (median age: 77.5) | Vitamin D | 1000 IU/day for 8 weeks, 6000 IU/day for 8 weeks | ADAS-cog, Disability Assessment, WMS-R LM | No improvement in cognition, memory, and disability | [151] |

| R, DB, PC | 86 PD patients (average age: 70.6 years) | 1α(OH)D3 | 0.1 μg/day for 18 months | Computed radiographic densitometry in the second metacarpals | Significant improvement in bone mineral densities and reduce the risk of hip and other non-vertebral fractures | [158] |

| R, AB | 150 cognitively intact PD patients | Vitamin D | ND | 6 MWT, 4 MWS, TUG, BBS, HS, SPDDS, BW, SMM | Significant improvement in lower extremity function and muscle mass | [159] |

| R, DB, PC | 51 PD patients (average age: 66.57 years) | Vitamin D | 10,000 IU/day for 16 weeks | SOT, TUG, SLLE, FF, NHP | Significant improvement in balance in younger patients | [160] |

| R, DB, PC | 114 PD patients (average age: 72 years) | Vitamin D3 | 1200 IU/day for 12 months | HY, UPDRS, NEDL, MEDL, ME, MC, MMSE | Significantly inhibit the development of PD | [161] |

| CR | 1 PD patient (age: 55 years) | Vitamin D | 4000 IU/day for 3 years | Neurological examination | No improvement in any symptom | [162] |

| CR | 1 MS patient born in 1950 | Vitamin D3 | 800 IU/day, 4000 IU/day, 6000 IU/day | muscular pain, ambulation ability | Improvement in motor function | [163] |

| R, PC | 62 MS patients | Vitamin D3 | 300,000 IU/month for 6 months | EDSS, number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions | No significant improvement in the status of disability | [164] |

| R, DB, PC | 68 fully ambulatory MS patients | Vitamin D3 | 20,000 IU/week for 96 weeks | ARR, EDSS, MSFC, grip strength, fatigue | No significant improvement in any symptoms | [165] |

| R, DB | 45 MS patients (age: over 18 years) | Vitamin D3 | 800 IU/day or 4370 IU/day for a year | ARR, EDSS, QoL, FLS | No significant improvement in any symptoms | [166] |

| R, DB | 40 MS patients (age: over 18 years) | Vitamin D3 | 800 IU/day or 4370 IU/day for a year | FAMS | No significant effect on depression | [167] |

| R, PC | 40 MS patients (age: 18–55 years) | Vitamin D3 | 14.000 IU/day for 48 weeks | HADS-D | No significant effect on depression | [168] |

| R, DB, PC | 94 RRMS patients (age: 18–55 years) | Vitamin D3 | 50,000 IU/5 days for 3 months | MSQOL-54 Persian version | Significant improvement in mental health | [169] |

| R, DB, PC | 66 MS patients (age: 18–55 years) | Vitamin D3 | 20,000 IU/week for a year | ARR, BOD, EDSS, timed 25-foot walk test, and timed 10 foot tandem walk tests | Significant reduction in the activity of the disease | [170] |

| R, DB, PC | 181 RRMS patients (age: 18–65 years) | Vitamin D3 | 100,000 IU/week for 96 weeks | ARR, MRI parameters, EDSS | Significantly less progress | [171] |

| R, DB, PC | 229 RRMS patients (age: 18–55 years) | Vitamin D3 | 6670 IU/day for 4 weeks; then 14,007 IU/day for 44 weeks | NEDA-3 | Significantly less progress | [173] |

| R | 88 MS patients (average age: 36.3 years) | Vitamin D3 | diet and sunlight expose | MoCA, SDMT, BVMT-R | Significant improvement in cognition | [174] |

| R, DB, PC | 158 MS patients (average age: 41.1 years) | Alfacalcidol | 1 mcg/day for 6 months | FIS | Significant decrease in fatigue and improvement in QoL | [175] |

| CR | 1 AD patient (age: 88 years) | Eldecalcitol | 0.75 μg/day for 5 months | MMSE, IADL, Electrocardiogram, laboratory examination | Cognitive decline, hypercalcemia, and renal dysfunction | [177] |

| CR | 1 MS patient (age: 45 years) | Vitamin D3 | ND | ND | hypercalcemia | [178] |

| CR | 1 MS patient (age: 58 years) | Vitamin D3 | 5500 IU/day for several years | Electrocardiogram, laboratory examination | Severe hypercalcemia | [180] |

CR, Case report; R, Randomized; DB, Double-blind; PC, Placebo-controlled; OL, Open-label; AB, assessor-blind; WAIS-RC, Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised; ADL, Activity of Daily Living; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; ADAS-cog, Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale-cognitive subscale; WMS-R LM, Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical memory; BPSD, behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; 6 MWT, 6-min walking test; 4 MWS, 4-m walking speed; TUG, Timed Up and Go test; BBS, Berg balance scale; HS, handgrip strength; SPDDS, Self-assessment Parkinson’s Disease Disability Scale; BW, body weight; SMM, skeletal muscle mass; SOT, Sensory Organization Test; SLLE, strength of leg flexion and extension; FF, fall frequency; NHP, Nottingham health profile; HY, the modified Hoehn and Yahr stage; UPDRS, Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Stage; NEDL, nonmotor experiences of daily living; MEDL, motor experiences of daily living; ME, motor examination; MC, motor complications; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; ARR, relapse rate; MSFC, multiple sclerosis functional composite; QoL, Quality of Life; FLS, Flu-like symptoms; FAMS, Functional assessment of MS; HADS-D, Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale depression subscale; BOD, burden of disease; RRMS, relapsing-remitting MS; NEDA-3, no evidence of disease activity; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SDMT, Symbol Digit Modalities; BVMT-R, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test; FIS, Fatigue Impact Scale; ND, not determined.

Whether Vitamin D could improve the clinical symptoms of AD also has been investigated. A trial investigated the influence of vitamin D supplements on the cognition of 210 AD patients, showing that oral vitamin D supplements (800 IU/day) for 12 months can significantly improve cognitive function in AD patients [150]. But in 2011, a randomized controlled trial including 63 individuals found that vitamin D couldn’t improve cognition or disability in mild-moderate AD, no matter low dose (1000 IU/day) or high dose (6000 IU/day) [151]. Cognitive impairment is an important feature of AD patients [152]. In a study about aged people, medium-chain triglycerides in combination with leucine and vitamin D may benefit cognitive function in frail elderly individuals [153]. And a trial by 183 elderly subjects with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) found that vitamin D supplement (800 IU/day) for 12 months showed to have an improvement in cognition through reducing oxidative stress regulated by increased TL in elder MCI adults [154]. But more trials showed vitamin D supplements couldn’t improve the cognition of subjects [[155], [156], [157]]. In summary, no sufficient evidence could prove that vitamin D could improve the symptoms in AD patients.

Vitamin D supplement was found to have some clinical benefits for PD patients. A trial conducted in 1999 with 86 elderly PD patients found that 1α(OH)D3 supplement (0.1 μg/day) for 18 months could reduce the risk of hip and other non-vertebral fractures by retarding the bone mineral densities loss in osteoporotic elderly PD patients [158]. And Michela et al. performed a trial in completely cognitive PD patients for 10 months. The subjects received a standard hospital diet with or without whey protein-based nutritional supplement enriched with leucine and vitamin D twice daily and underwent a 30-day multidisciplinary intensive rehabilitation treatment (MIRT). In this trial, a whey protein-based nutritional formula enriched with leucine and vitamin D with MIRT showed benefits in lower extremity function and maintained muscle mass in PD patients and Class I evidence also showed the diet formula used in this study with intensive rehabilitation could increase the walking distance of PD patients during a 6-min walking test (6 MWT) [159]. In addition, it was suggested that vitamin D could have the potential of improving balance in younger PD patients with the intake of high-dose vitamin D (10,000 IU/day) for 16 weeks [160]. Except for the effect on motor function, the development of PD could also be controlled by vitamin D. A trial appeared that a vitamin D3 supplement (1200 IU/day) for 12 months probably could prevent the deterioration of PD in a short time in patients with FokI TT or CT genotypes [161]. However, only a case reported in 1997 presented that regular therapy with 4000 IU D3/day and 1 g Ca/day for 3 years couldn’t benefit the fifty-year-old PD patient [162]. In general, the benefit of vitamin D on PD is obvious.

In a 10-year case report, a female MS patient ingested vitamin D supplements every day since January 2001 with a dose of 800 IU/day, then increased to 4000 IU/day in September 2004 and 6000 IU/day in December 2005. The supplement reduced muscular pain and improved ambulation in the patient [163]. The clinical effects of vitamin D in MS have been well investigated in many trials. A trial was conducted in 2011 and included 62 MS patients. They received 300,000 IU/month or placebo by intramuscular injection for 6 months. The result showed no significant differences between these two groups in the expanded disability status scale scores (EDSS) and the number of gadolinium-enhancing lesions [164]. Another study also found that 20,000 IU/week supplements of vitamin D for 96 weeks had limited effects in fully ambulatory MS patients [165]. A trial conducted by Daniel et al. about vitamin D and interferon (IFN)-β in 45 MS patients showed both 800 IU/day and 4370 IU/day of vitamin D3 for a year had no significant improvement in ARR, EDSS, Quality of Life (QoL) and Flu-like symptoms (FLS), which are common side effects of IFN-β treatment [166]. They also found that the intake of vitamin D3 in the same doses for a year did not affect depression conditions in MS patients [167]. A similar result was also yielded in another study [168].

However, a study in 94 relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) patients appeared that 50,000 IU/5d vitamin D for 3 months significantly improved the mental health of the patients [169]. A study in 66 MS patients was conducted to find the security and efficiency of the addition of vitamin D3 to the treatment of IFN β-1b (IFNB), showing that the combination of 20,000 IU/week of vitamin D3 and IFNB for a year could reduce the activity of the disease without a higher risk of adverse events [170]. In addition, William et al. performed a trial in 2019 involving 189 RRMS patients. The group with the dose of 100,000 IU every week for 96 weeks had less progress in MS [171]. Another similar finding was also obtained in other studies [172,173]. In terms of cognition, vitamin D also showed benefits to MS patients. In a study, the levels of serum vitamin D in the patients were supplemented by diet and sunlight exposure. After 3 months, this form of vitamin D supplement could improve cognition in MS patients [174]. Another trial also investigated the effect of vitamin D on fatigue, one of the most common and disabling symptoms of MS. 158 MS patients with significant fatigue were involved in this trial. Randomly divided into two groups, they were given 1 mcg/day of alfacalcidol or placebo for six months and assessed the level of fatigue by the Fatigue Impact Scale (FIS) score. The result appeared that alfacalcidol could decrease fatigue and improve QoL in MS patients without serious adverse events [175].

While the doses of vitamin D supplementation might vary from person to person, it was suggested increasing vitamin D intake and having appropriate sunlight exposure to maintain serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D at least 30 ng/mL (75 nmol/L), and preferably at 40–60 ng/mL (100–150 nmol/L) to achieve the optimal overall health benefits of vitamin D. However, it is still crucial and essential to determine the doses and duration of vitamin D supplementation since vitamin D supplementation can trigger undesirable consequences [176]. A case report of an 88-year-old woman showed that a long-term supplement of vitamin D with 0.75 μg eldecalcitol capsules per day could worsen the symptoms of AD and cause hypercalcemia and renal dysfunction, leading to chronic delirium [177]. Similarly, some case reports also alarmed that excessive intake of vitamin D could cause hypercalcemia and even threaten patients' lives [[178], [179], [180]]. But this toxicity of vitamin D can be alleviated by simultaneous supplements of vitamin K and vitamin A [181].

6. Conclusions

Vitamin D exhibits its functions through binding to its nuclear receptor VDR, membrane receptor 1,25 D3-MARRS, or interfering with molecules in signaling pathways that are associated with the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases, such as AD, PD, MS, and VaD. Still, more experiments on cell and animal models are required for further insight into molecular mechanisms of vitamin D to attenuate cognitive and motor dysfunctions caused by neurodegenerative diseases. In addition, some of the clinical studies that we concluded in this review demonstrated positive effects of vitamin D supplementation on neurodegenerative diseases while the rest displayed no significant influence. The contradictory results can probably be attributed to diverse doses and durations of vitamin D treatment. Therefore, intricately designed, large multicenter clinical trials need to be conducted to investigate and analyze the potency of vitamin D in influencing the clinical symptoms of patients with neurodegenerative disorders whether as clinical nutrition or as a therapy.

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

Xianfang Meng was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [81671066 & 81974162].

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interest’s statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Holick M.F. Vitamin D deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holick M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017;18:153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holick M.F. The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2017;18:153–165. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9424-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holick M.F. McCollum Award Lecture, 1994: vitamin D--new horizons for the 21st century. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994;60:619–630. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.4.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prentice A. Nutritional rickets around the world. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013;136:201–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Willett W.C., Wong J.B., Stuck A.E., Staehelin H.B., Orav E.J., et al. Prevention of nonvertebral fractures with oral vitamin D and dose dependency: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2009;169:551–561. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reid I.R. Effects of vitamin D supplements on bone density. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2015;38:91–94. doi: 10.1007/s40618-014-0127-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nitsa A., Toutouza M., Machairas N., Mariolis A., Philippou A., Koutsilieris M. Vitamin D in cardiovascular disease. In Vivo. 2018;32:977–981. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeon S.M., Shin E.A. Exploring vitamin D metabolism and function in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2018;50:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0038-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chau Y.Y., Kumar J. Vitamin D in chronic kidney disease. Indian J. Pediatr. 2012;79:1062–1068. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0765-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bartley J. Vitamin D: emerging roles in infection and immunity. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2010;8:1359–1369. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugger B.N., Dickson D.W. Pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2017;9 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandes de Abreu D.A., Eyles D., Féron F. Vitamin D, a neuro-immunomodulator: implications for neurodegenerative and autoimmune diseases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S265–S277. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stumpf W.E., Sar M., Clark S.A., DeLuca H.F. Brain target sites for 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Science. 1982;215:1403–1405. doi: 10.1126/science.6977846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gil A., Plaza-Diaz J., Mesa M.D. Vitamin D: classic and novel actions. Ann. Nutr. Metabol. 2018;72:87–95. doi: 10.1159/000486536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eyles D.W., Burne T.H.J., McGrath J.J. Vitamin D, effects on brain development, adult brain function and the links between low levels of vitamin D and neuropsychiatric disease. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34:47–64. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bikle D.D. Vitamin D metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical applications. Chem. Biol. 2014;21:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landel V., Annweiler C., Millet P., Morello M., Féron F. Vitamin D, cognition and Alzheimer’s disease: the therapeutic benefit is in the D-tails. J Al.zheimers Dis. 2016;53:419–444. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlögl M., Holick M.F. Vitamin D and neurocognitive function. Clin. Interv. Aging. 2014;9:559–568. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S51785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pike J.W., Christakos S. Biology and mechanisms of action of the vitamin D hormone. Endocrinol Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2017;46:815–843. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y., Zhu J., DeLuca H.F. Where is the vitamin D receptor? Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2012;523:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eyles D.W., Smith S., Kinobe R., Hewison M., McGrath J.J. Distribution of the vitamin D receptor and 1 alpha-hydroxylase in human brain. J. Chem. Neuroanat. 2005;29:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riccio P., Rossano R. Diet, gut microbiota, and vitamins D + A in multiple sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2018;15:75–91. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0581-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goltzman D. Functions of vitamin D in bone. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2018;149:305–312. doi: 10.1007/s00418-018-1648-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pike J.W., Meyer M.B., Bishop K.A. Regulation of target gene expression by the vitamin D receptor - an update on mechanisms. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2012;13:45–55. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones G, Strugnell Sa Fau - DeLuca HF, DeLuca HF. Current Understanding of the Molecular Actions of Vitamin D. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Nemere I., Dormanen M.C., Hammond M.W., Okamura W.H., Norman A.W. Identification of a specific binding protein for 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in basal-lateral membranes of chick intestinal epithelium and relationship to transcaltachia. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:23750–23756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hernigou P., Auregan J.C., Dubory A. Vitamin D: part II; cod liver oil, ultraviolet radiation, and eradication of rickets. Int. Orthop. 2019;43:735–749. doi: 10.1007/s00264-019-04288-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trivedi D.P., Doll R., Khaw K.T. Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomised double blind controlled trial. BMJ. 2003;326:469. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7387.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawson-Hughes B., Harris S.S., Krall E.A., Dallal G.E. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337:670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larsen E.R., Mosekilde L., Foldspang A. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents osteoporotic fractures in elderly community dwelling residents: a pragmatic population-based 3-year intervention study. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19:370–378. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.0301240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bischoff-Ferrari H.A., Dawson-Hughes B., Willett W.C., Staehelin H.B., Bazemore M.G., Zee R.Y., et al. Effect of Vitamin D on falls: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1999–2006. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prietl B., Treiber G., Pieber T.R., Amrein K. Vitamin D and immune function. Nutrients. 2013;5:2502–2521. doi: 10.3390/nu5072502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T.T., Dabbas B., Laperriere D., Bitton A.J., Soualhine H., Tavera-Mendoza L.E., et al. Direct and indirect induction by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 of the NOD2/CARD15-defensin beta2 innate immune pathway defective in Crohn disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:2227–2231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.071225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gombart A.F., Borregaard N., Koeffler H.P. Human cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) gene is a direct target of the vitamin D receptor and is strongly up-regulated in myeloid cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Faseb. J. 2005;19:1067–1077. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3284com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yuk J.M., Shin D.M., Lee H.M., Yang C.S., Jin H.S., Kim K.K., et al. Vitamin D3 induces autophagy in human monocytes/macrophages via cathelicidin. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penna G., Adorini L. 1 Alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 inhibits differentiation, maturation, activation, and survival of dendritic cells leading to impaired alloreactive T cell activation. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2405–2411. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berer A., Stöckl J., Majdic O., Wagner T., Kollars M., Lechner K., et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) inhibits dendritic cell differentiation and maturation in vitro. Exp. Hematol. 2000;28:575–583. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(00)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S., Sims G.P., Chen X.X., Gu Y.Y., Chen S., Lipsky P.E. Modulatory effects of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 on human B cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1634–1647. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pertile R.A.N., Cui X., Hammond L., Eyles D.W. Vitamin D regulation of GDNF/Ret signaling in dopaminergic neurons. Faseb. J. 2018;32:819–828. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700713R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eyles D., Almeras L., Benech P., Patatian A., Mackay-Sim A., McGrath J., et al. Developmental vitamin D deficiency alters the expression of genes encoding mitochondrial, cytoskeletal and synaptic proteins in the adult rat brain. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;103:538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.12.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Almeras L., Eyles D., Benech P., Laffite D., Villard C., Patatian A., et al. Developmental vitamin D deficiency alters brain protein expression in the adult rat: implications for neuropsychiatric disorders. Proteomics. 2007;7:769–780. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Viragh P.A., Haglid K.G., Celio M.R. Parvalbumin increases in the caudate putamen of rats with vitamin D hypervitaminosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989;86:3887–3890. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.10.3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexianu M.E., Robbins E., Carswell S., Appel S.H. 1Alpha, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D3-dependent up-regulation of calcium-binding proteins in motoneuron cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 1998;51:58–66. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980101)51:1<58::AID-JNR6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calton E.K., Keane K.N., Soares M.J. The potential regulatory role of vitamin D in the bioenergetics of inflammation. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care. 2015;18:367–373. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Garcion E., Sindji L., Montero-Menei C., Andre C., Brachet P., Darcy F. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase during rat brain inflammation: regulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Glia. 1998;22:282–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garcion E., Sindji L., Leblondel G., Brachet P., Darcy F. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the synthesis of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and glutathione levels in rat primary astrocytes. J. Neurochem. 1999;73:859–866. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0730859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berridge M.J. Vitamin D, reactive oxygen species and calcium signalling in ageing and disease. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2016;371 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2015.0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gezen-Ak D., Dursun E., Yilmazer S. The effect of vitamin D treatment on nerve growth factor (NGF) release from hippocampal neurons. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2014;51:157–162. doi: 10.4274/npa.y7076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khairy E.Y., Attia M.M. Protective effects of vitamin D on neurophysiologic alterations in brain aging: role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Nutr. Neurosci. 2021;24:650–659. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2019.1665854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Garcion E., Wion-Barbot N., Montero-Menei C.N., Berger F., Wion D. New clues about vitamin D functions in the nervous system. Trends Endocrinol. Metabol. 2002;13:100–105. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Latimer C.S., Brewer L.D., Searcy J.L., Chen K.C., Popović J., Kraner S.D., et al. Vitamin D prevents cognitive decline and enhances hippocampal synaptic function in aging rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014;111:E4359–E4366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404477111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baksi S.N., Hughes M.J. Chronic vitamin D deficiency in the weanling rat alters catecholamine metabolism in the cortex. Brain Res. 1982;242:387–390. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90331-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puchacz E., Stumpf W.E., Stachowiak E.K., Stachowiak M.K. Vitamin D increases expression of the tyrosine hydroxylase gene in adrenal medullary cells. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;36:193–196. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00314-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taniura H., Ito M., Sanada N., Kuramoto N., Ohno Y., Nakamichi N., et al. Chronic vitamin D3 treatment protects against neurotoxicity by glutamate in association with upregulation of vitamin D receptor mRNA expression in cultured rat cortical neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2006;83:1179–1189. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Izzo M., Carrizzo A., Izzo C., Cappello E., Cecere D., Ciccarelli M., et al. Vitamin D: not just bone metabolism but a key player in cardiovascular diseases. Life (Basel) 2021:11. doi: 10.3390/life11050452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pfeifer M., Begerow B., Minne H.W., Nachtigall D., Hansen C. Effects of a short-term vitamin D(3) and calcium supplementation on blood pressure and parathyroid hormone levels in elderly women. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:1633–1637. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.4.7393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Autier P., Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch. Intern. Med. 2007;167:1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ma Y., Johnson C.S., Trump D.L. Mechanistic insights of vitamin D anticancer effects. Vitam. Horm. 2016;100:395–431. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang C., Tong T., Miao D.C., Wang L.F. Vitamin D inhibits TNF-α induced apoptosis of human nucleus pulposus cells through regulation of NF-kB signaling pathway. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021;16:411. doi: 10.1186/s13018-021-02545-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu T., Liu T.J., Shi Y.Y., Zhao Q. Vitamin D/VDR signaling pathway ameliorates 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis by inhibiting intestinal epithelial apoptosis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2015;35:1213–1218. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arfian N., Muflikhah K., Soeyono S.K., Sari D.C., Tranggono U., Anggorowati N., et al. Vitamin D attenuates kidney fibrosis via reducing fibroblast expansion, inflammation, and epithelial cell apoptosis. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 2016;62:E38–E44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haapasalo A., Hiltunen M. A report from the 8th kuopio alzheimer symposium. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2018;8:289–299. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2018-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Qiu C., Kivipelto M., von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2009;11:111–128. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2009.11.2/cqiu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wolters F.J., Ikram M.A. Erratum to: epidemiology of dementia: the burden on society, the challenges for research. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018;1750:E3. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7704-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ballard C., Gauthier S., Corbett A., Brayne C., Aarsland D., Jones E. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2011;377:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Venigalla M., Sonego S., Gyengesi E., Sharman M.J., Münch G. Novel promising therapeutics against chronic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2016;95:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Serrano-Pozo A., Frosch M.P., Masliah E., Hyman B.T. Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011;1:a006189. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gąsiorowski K., Brokos B., Echeverria V., Barreto G.E., Leszek J. RAGE-TLR crosstalk sustains chronic inflammation in neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:1463–1476. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0419-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chai B., Gao F., Wu R., Dong T., Gu C., Lin Q., et al. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: an updated meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19:284. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1500-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jayedi A., Rashidy-Pour A., Shab-Bidar S. Vitamin D status and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of dose-response (†) Nutr. Neurosci. 2019;22:750–759. doi: 10.1080/1028415X.2018.1436639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Morello M., Landel V., Lacassagne E., Baranger K., Annweiler C., Féron F., et al. Vitamin D improves neurogenesis and cognition in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2018;55:6463–6479. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0839-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Durk M.R., Han K., Chow E.C., Ahrens R., Henderson J.T., Fraser P.E., et al. 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 reduces cerebral amyloid-β accumulation and improves cognition in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:7091–7101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2711-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grimm M.O.W., Thiel A., Lauer A.A., Winkler J., Lehmann J., Regner L., et al. Vitamin D and its analogues decrease amyloid-β (Aβ) formation and increase aβ-degradation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18122764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lai R.H., Hsu C.C., Yu B.H., Lo Y.R., Hsu Y.Y., Chen M.H., et al. Vitamin D supplementation worsens Alzheimer’s progression: animal model and human cohort studies. Aging Cell. 2022;21 doi: 10.1111/acel.13670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller B.J., Whisner C.M., Johnston C.S. Vitamin D supplementation appears to increase plasma Aβ40 in vitamin D insufficient older adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:843–847. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Masoumi A., Goldenson B., Ghirmai S., Avagyan H., Zaghi J., Abel K., et al. 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 interacts with curcuminoids to stimulate amyloid-beta clearance by macrophages of Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:703–717. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu T.Y., Zhao L.X., Zhang Y.H., Fan Y.G. Activation of vitamin D receptor inhibits Tau phosphorylation is associated with reduction of iron accumulation in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Neurochem. Int. 2022;153 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2021.105260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang L., Hara K., Van Baaren J.M., Price J.C., Beecham G.W., Gallins P.J., et al. Vitamin D receptor and Alzheimer’s disease: a genetic and functional study. Neurobiol. Aging. 2012;33:1844.e1–1844.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saad El-Din S., Rashed L., Medhat E., Emad Aboulhoda B., Desoky Badawy A., Mohammed ShamsEldeen A., et al. Active form of vitamin D analogue mitigates neurodegenerative changes in Alzheimer’s disease in rats by targeting Keap1/Nrf2 and MAPK-38p/ERK signaling pathways. Steroids. 2020;156 doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2020.108586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gezen-Ak D., Dursun E., Yilmazer S. The effects of vitamin D receptor silencing on the expression of LVSCC-A1C and LVSCC-A1D and the release of NGF in cortical neurons. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Brewer L.D., Porter N.M., Kerr D.S., Landfield P.W., Thibault O. Chronic 1alpha,25-(OH)2 vitamin D3 treatment reduces Ca2+ -mediated hippocampal biomarkers of aging. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brewer L.D., Thibault V., Chen K.C., Langub M.C., Landfield P.W., Porter N.M. Vitamin D hormone confers neuroprotection in parallel with downregulation of L-type calcium channel expression in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:98–108. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-01-00098.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berridge M.J. Vitamin D cell signalling in health and disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;460:53–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nissou M.F., Guttin A., Zenga C., Berger F., Issartel J.P., Wion D. Additional clues for a protective role of vitamin D in neurodegenerative diseases: 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 triggers an anti-inflammatory response in brain pericytes. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42:789–799. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ali A., Shah S.A., Zaman N., Uddin M.N., Khan W., Ali A., et al. Vitamin D exerts neuroprotection via SIRT1/nrf-2/NF-kB signaling pathways against D-galactose-induced memory impairment in adult mice. Neurochem. Int. 2021;142 doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Forster R.E., Jurutka P.W., Hsieh J.-C., Haussler C.A., Lowmiller C.L., Kaneko I., et al. Vitamin D receptor controls expression of the anti-aging klotho gene in mouse and human renal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;414:557–562. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.O’Kelly J., Uskokovic M., Lemp N., Vadgama J., Koeffler H.P. Novel Gemini-vitamin D3 analog inhibits tumor cell growth and modulates the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;100:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rai S.N., Singh P., Steinbusch H.W.M., Vamanu E., Ashraf G., Singh M.P. The role of vitamins in neurodegenerative disease: an update. Biomedicines. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9101284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Orme R.P., Bhangal M.S., Fricker R.A. Calcitriol imparts neuroprotection in vitro to midbrain dopaminergic neurons by upregulating GDNF expression. PLoS One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brown J., Bianco J.I., McGrath J.J., Eyles D.W. 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 induces nerve growth factor, promotes neurite outgrowth and inhibits mitosis in embryonic rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 2003;343:139–143. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jankovic JA-O, Tan EK. Parkinson’s Disease: Etiopathogenesis and Treatment. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Bonnet A.M., Houeto J.L. Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 1999;53:117–121. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(99)80076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Global, Regional, and National Burden of Neurological Disorders during 1990-2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rocha E.M., De Miranda B., Sanders L.H. Alpha-synuclein: pathology, mitochondrial dysfunction and neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2018;109:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Zhang Y., Ji W., Zhang S., Gao N., Xu T., Wang X., et al. Vitamin D inhibits the early aggregation of α-synuclein and modulates exocytosis revealed by electrochemical measurements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022;61 doi: 10.1002/anie.202111853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lashuel H.A., Overk C.R., Oueslati A., Masliah E. The many faces of α-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:38–48. doi: 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhou Z, Zhou R, Zhang Z, Li K. The Association between Vitamin D Status, Vitamin D Supplementation, Sunlight Exposure, and Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Zhou Z., Zhou R., Zhang Z., Li K. The association between vitamin D status, vitamin D supplementation, sunlight exposure, and Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Mon. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2019;25:666–674. doi: 10.12659/MSM.912840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fullard M.E., Duda J.E. A review of the relationship between vitamin D and Parkinson disease symptoms. Front. Neurol. 2020;11:454. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Shrestha S., Lutsey P.L., Alonso A., Huang X., Mosley T.H., Jr., Chen H. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations in Mid-adulthood and Parkinson’s disease risk. Mov. Disord. 2016;31:972–978. doi: 10.1002/mds.26573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]