Abstract

Context:

The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) requires coverage for mental health and substance use disorder (MH/SUD) to benefits be no more restrictive than for medical/surgical benefits in commercial health plans. State insurance departments oversee enforcement for certain plans. Insufficient enforcement is one potential source of continued MH/SUD treatment gaps among commercial insurance enrollees. This study explored state-level factors that may drive enforcement variation.

Methods:

The authors conducted a four-state multiple-case study to explore factors influencing state insurance offices’ enforcement of MHPAEA. They interviewed 21 individuals who represented state government offices, advocacy organizations, professional organizations, and a national insurer. Their analysis included a within-case content analysis and a cross-case framework analysis.

Findings:

Common themes included insurance office relationships with other stakeholders, policy complexity, and political priority. Relationships between insurance offices and other stakeholders varied between states. MHPAEA complexity posed challenges for interpretation and application. Political priority influenced enforcement via priorities of insurance commissioners, governors, and legislatures. Where enforcement of MHPAEA was not prioritized by any actors, there was minimal state enforcement.

Conclusions:

Within a state, enforcement of MHPAEA is influenced by insurance office relationships, legal interpretation, and political priorities. These unique state factors present significant challenges to uniform enforcement.

Background

Passed by Congress in 2008, the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act (MHPAEA) is considered a major victory for advocates of access to mental health and substance use disorder (MH/SUD) treatment. Broadly, the law requires commercial health plans to provide benefits covering MH/SUD treatment in a manner that is “no more restrictive” than that used for all other medical/surgical services. In the years since the law’s passage, research findings suggest it has had minimal effect on increasing access to treatment and decreasing the cost of care. Advocates identify a lack of insurer compliance and insufficient enforcement by government agencies as potential drivers of these underwhelming effects. Responsibility for oversight of insurers’ compliance with MHPAEA depends on the type of insurance plan. For a subset of plans, oversight is the responsibility of individual state insurance departments. This division of oversight responsibility may lead to uneven enforcement between states. Previous studies have not specifically addressed state agency activities related to MHPAEA enforcement. To address this gap, the primary objective of the study described in this article is to explore state-level factors impacting insurance department enforcement of MHPAEA.

Mental Health, Substance Use Disorders, and Health Insurance Coverage

Mental health and substance use conditions are prevalent in the United States. The 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health indicates that approximately 21.0% of US adults aged 18 or older had any mental illness, and 14.5% of individuals aged 12 or older had an SUD in the previous year. Of the adults with any mental illness, only 46.2% received mental health care. For those with SUDs, only 6.5% received treatment (SAMHSA 2021).

In 2019, 55.5% of people in the United States were covered by commercial insurance plans (KFF n.d.). Historically, commercial insurers offered significantly more restrictive inpatient and outpatient MH/SUD treatment coverage compared to coverage for treatment for medical/surgical (all other health care except MH/SUD treatment) conditions (Frank and McGuire 2000). For example, insurers imposed higher copays and covered fewer inpatient hospital days and outpatient visits for MH/SUD treatment than for medical/surgical services.

In response to this unequal coverage, beginning in the 1970s, states introduced policies ranging from required minimum mental health benefits to full MH/SUD parity in commercial health plans (Frank and McGuire 2000; Cauchi and Hanson 2015). However, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 19741 exempted self-insured plans from state regulations. This gap was closed when President George W. Bush signed the MHPAEA into law in 2008.2

The federal MH/SUD parity law requires that commercial health insurance plans that provide benefits for MH/SUD treatment do so in a manner consistent with medical/surgical benefits. It requires parity in financial requirements (deductibles, copays, cost sharing) and treatment limitations (number of visits, covered days). The final rules, released in 2013, specify that parity protections apply to both quantitative treatment limitations (numbers of visits) and nonquantitative treatment limitations (NQTLs, such as prior authorizations or medical management procedures). Additionally, the law requires insurer transparency about medical necessity criteria and coverage denials (CMS n.d.). These protections were extended to more plans in 2010 when behavioral health coverage became required as part of the Essential Health Benefits in the Affordable Care Act.3

Implementation and Enforcement of MHPAEA

For commercial insurance plans, responsibility for enforcement of MHPAEA is divided between the Department of Labor (for self-insured employer-sponsored plans), the Department of Health and Human Services (for state or local government self-insured plans), and—the focus of the present study—state insurance commissioners’ offices (for fully insured employer-sponsored plans with more than 50 employees and individual marketplace plans) (GAO 2019). The degree to which insurance commissioners enforce MHPAEA and the strategies they use are likely multidetermined. Agency structure may affect division of labor and enforcement activities. Variation in staffing capacity between states’ insurance commissioners’ offices also influences enforcement (Kober and Rentner 2012; Scholz and Wei 1986). Finally, relationships between insurance commissioners’ offices and other parity stakeholders (professional organizations or advocacy groups) could impact state-level actions (Hoefer 2005; Pacewicz 2018).

Impact of MHPAEA

Extant parity research has explored the impact of MHPAEA on benefit design and MH/SUD treatment utilization and spending. Studies evaluating changes in benefit design found most health plans complying with quantitative treatment limitations, a decrease in NQTLs, and alignment with medical/surgical benefits (Horgan et al. 2016; Thalmayer et al. 2017; Thalmayer et al. 2018). Despite evidence of changes in benefit design, studies of utilization and spending found minimal effects (Busch et al. 2013; Busch et al. 2014; Grazier et al. 2015; Busch et al. 2017: Stuart et al. 2017; Huskamp et al. 2018; Kennedy-Hendricks et al. 2018; Block et al. 2020; Friedman et al. 2020). The small effects seen in studies suggest that MHPAEA has not met advocates’ expectations.

Advocacy groups and coalitions identify multiple reasons for ongoing barriers to MH/SUD treatment, including nationwide provider shortages, lack of provider acceptance of insurance, and stigmatizing attitudes. They have also pointed to a lack of sufficient compliance by insurers and enforcement by government agencies as potential causes of the underwhelming effects of MHPAEA. In a 2019 STAT opinion piece Patrick Kennedy and Jim Ramstad wrote: “The regulation and oversight of these companies is fragmented and meager. Federal and state regulators should not accept self-reports by insurers as evidence of compliance with anything—let alone with parity laws intended to protect those with mental health and substance use disorders” (Kennedy and Ramstad 2019). Their sentiments are echoed in policy briefs (Goodell 2015) and government reports (GAO 2019; SAMHSA 2016) as well as a June 2022 article in the Washington Post that highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the urgency of access to MH/SUD treatment (Bernstein 2022). However, empirical research on state enforcement of MHPAEA is lacking.

Challenges to Implementation and Enforcement

The Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services and the Internal Revenue Service released interim final rules for implementation of MHPAEA in 2010. This release was followed by a public comment period in which representatives from health insurers, behavioral health provider organizations, patient and family advocacy groups, and state government offices raised questions and concerns about the law’s implementation. Some common concerns across commenters included how to assess parity for MH/SUD treatment services that lack equivalent medical/surgical care (or vice-versa), how and whether to include network adequacy standards and reimbursement rates for providers given known shortages in those professions, and consideration of clinical best-practices/evidence-based treatments (EBSA n.d.).

The 2013 final rules for implementation of MHPAEA addressed some of these stakeholder concerns. However, recognition of the challenges associated with MHPAEA implementation and enforcement is evidenced by the ongoing release of guidance, reports, and FAQ documents from 2010 through the present by agencies including the Department of Labor, the Department of Health and Human Services, the Internal Revenue Service, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Government Accountability Office (GAO). Two reports, one from SAMHSA and the other from GAO, provide specific insight into state enforcement practices. The 2016 SAMHSA report identified five areas as key to successful enforcement: (1) open channels of communication, (2) standardization of materials, (3) creation of templates, workbooks, and other tools, (4) implementation of market conduct exams and network adequacy assessments, and (5) collaboration with multiple agencies and stakeholder groups. A major conclusion of the report is that implementation of and compliance with MHPAEA requires that all five of those elements be implemented simultaneously (SAMHSA 2016).

The 2019 GAO report to Congress addressed the status of MHPAEA oversight and enforcement in the federal government and the states. The GAO surveyed all 50 states about their processes for assessing compliance with MHPAEA and their enforcement activities in 2017 and 2018, and the agency interviewed representatives from Maryland, Massachusetts, and Wyoming. They found that most insurance commissioners’ offices include some assessment of compliance with parity in coverage for MH/SUD treatment, but that the nature of these assessments varies, especially among those conducted on approved plans with enrollees (GAO 2019). The types of reviews included targeted reviews based on consumer complaints or other factors (e.g., government agency recommendation, public scrutiny), random audits, and market conduct examinations (review of insurer operations, including business practices, to assess compliance with laws related to the sale of products and settlement of claims). The report also mentioned challenges to enforcement, including the complexity of assessing compliance with NQTLs because of difficulty in identifying how plans implement them, and lack of resources to conduct in-depth evaluations (GAO 2019).

Both the SAMHSA and GAO reports explore aspects of state MH/SUD treatment coverage parity enforcement, with the former looking at successful enforcement in a small set of states and the latter gathering high-level information about the enforcement process from all states. Both reports mention resources (including staff time) allocated to MHPAEA enforcement as factors in a state insurance commissioner’s office’s enforcement activity. The current case study characterizes and compares federal parity enforcement in four states: two that have insurance commissioners’ offices with high staffing capacity, and two that have insurance commissioners’ offices with low staffing capacity. Specifically, this study was designed to answer two research questions: (1) What factors influence state insurance commissioners’ enforcement of the federal parity law? (2) Do those factors differ in states with high versus low staffing capacity in insurance commissioners’ offices? An understanding of the drivers of state-level enforcement of MHPAEA will provide insight into whether standardization across states is feasible, and if so, where to target efforts to ensure consistent enforcement.

Methods

To explore factors influencing enforcement of MHPAEA across states, we conducted a multiple-case study of four states using semistructured interviews with key stakeholders (staff from government offices, leaders in advocacy organizations, and members of professional organizations) and document reviews. We defined a case as a state that enforces MHPAEA through its insurance department. To compare federal parity enforcement in states with high versus low insurance agency staffing capacity, we selected two states with high capacity (Rhode Island and Georgia) and two states with low capacity (Massachusetts and West Virginia).

Data Collection

We compiled state characteristics from the US Census Bureau, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, the National Association of State Budget Officers, and America’s Health Insurance Plans (table 1). We used websites of state agencies, legislatures, and advocacy groups to identify MH/SUD parity specific information. We conducted 21 interviews across the four states with staff in state agencies such as insurance commissioners’ offices, attorneys general’s offices, behavioral health divisions of health departments, advocacy organizations, members of mental health professional organizations, and one national health insurance representative. To identify interviewees, we used purposive and snowball sampling. Participation was inconsistent across states (table 2). We did not compensate interviewees for their participation. Interviews averaged 45 minutes in length, with the shortest lasting 30 minutes and the longest lasting 90 minutes.

Table 1.

State Demographics

| GA | MA | RI | WV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State population | ||||

| Census 20201 | 10,711,908 | 7,029,917 | 1,097,379 | 1,793,716 |

| % Urban 20102 | 75.1 | 92.0 | 90.7 | 48.7 |

| Insurance dept demographics | ||||

| Standalone dept or Division of other dept | Standalone | Division | Division | Standalone |

| % Change in staffing 2015–20193 | −13.6 | −13.1 | 0 | −38.3 |

| % Change in proportion of state budget 2015–20193,4 | −15.5 | −6.5 | −26.4 | −15.1 |

| Insurance enrollment 6 | ||||

| Private | 55.0 | 61.0 | 60.0 | 47.0 |

| Medicare | 13.0 | 13.0 | 15.0 | 19.0 |

| Medicaid | 17.0 | 22.0 | 21.0 | 27.0 |

| Other public | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Uninsured | 13.0 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 7.0 |

| % population in plans where MHPAEA compliance overseen by state | 13.9 | 21.2 | 15.0 | 9.0 |

Data retrieved from the 2020 Census Apportionment Results released April 2021 https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2020/dec/2020-apportionment-data.html

Data retrieved from the 2010 Census data https://data.census.gov/cedsci/all?q=2010%20census%20rural

Data retrieved from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners Resource Report 2019: Volume 1 https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/publication-sta-hb-volume-one.pdf

State budgets retrieved from the National Association of State Budget Officers https://www.nasbo.org/reports-data/state-expenditure-report

Table 2.

Interviewees by State

| GA | MA | RI | WV | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance Dept. | - | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 |

| Behavioral Health Dept. | - | - | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Attorney General’s Office | - | 2 | 1 | - | 3 |

| Advocacy & Professional Orgs. | 3 | 3 | 2 | - | 7 |

| Total | 3 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 19 |

The study team developed an interview guide for staff in insurance commissioners’ offices and adapted it for staff in other government offices. We created a separate guide for advocates and members of professional organizations. To develop the guides, we used a review of the literature, the experience and expertise of the research team members, and the research questions. We collected interviewee-identified documents (e.g., market conduct reports) and included them as part of individual case data. The first author conducted all interviews via telephone or video conference between December 2020 and March 2021. Interviews continued until interviewees provided similar answers to questions, suggesting that data saturation was reached (Morse 1995).

Data Analysis

We summarized relevant characteristics for each state including total population, urbanicity of the population (as defined by the 2010 US census), characteristics of the insurance commissioners’ offices, and health insurance enrollment by payor. To analyze interview data, we conducted a content analysis for each case, followed by a framework analysis for cross-case comparisons. We used a combination of inductive and deductive coding to analyze interview transcripts. To develop an initial codebook, we used the interview domains, concepts present across summary memos crafted by the interviewer, and Markell and Glicksman’s three-layered framework for agency regulation (Markell and Glicksman 2014: 43). Two members of the research team piloted the codebook on one transcript from each state. We refined the codebook iteratively, with study team members reviewing development of themes and subthemes.

To develop the framework for cross-case comparisons, we used the codebook from the within-case analysis. Comparing the themes and subthemes from the cases, we distilled results down to the most salient concordant and discordant themes across the cases. We considered themes salient if they were present in at least three of the cases and pertained to state insurance commissioners’ offices’ enforcement of MHPAEA. We conducted member-checking with interviewees in each state. We coded and analyzed the data in ATLAS.ti 9. This research was determined to be not human subjects research by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (additional methods specifications can be found in appendix A).

Findings

Within-Case Analysis

Georgia

For 2021, 13.9% of Georgia residents were insured through private health plans that were subject to state oversight and were required to comply with federal MH/SUD parity, i.e., fully insured employer sponsored plans with more than 50 employees and plans sold on the individual marketplace (AHIP 2021). The Office of the Commissioner of Insurance oversees these plans. Georgia is one of 11 states to elect its insurance commissioner. By state law, the commissioner must examine insurers at least once every five years.4

Enforcement Context and Actions.

The Office of the Commissioner of Insurance’s website provides forms that health insurers are required to submit for new plans and changes to existing plans (OCISF n.d.). The forms include information about access to health care services, quality assurance, financial incentives, patient confidentiality, and formulary design. None of the forms include items specifically about compliance with MHPAEA. Additionally, there are no easily identifiable records of market conduct evaluations on the insurance commissioner’s website, which precludes determination of the extent to which Georgia may evaluate compliance in routine or targeted exams.

Additional Government Actions.

In 2019, Governor Brian Kemp and the Georgia General Assembly established the Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission. The commission, which expires in June of 2023, comprises 24 appointed members and is tasked with conducting a comprehensive review of Georgia’s behavioral health system. Among the findings and recommendations from the commission’s first report (filed in 2020) are the following recommendations for commercial plans: ensuring the Department of Insurance performs regular market conduct examinations focusing on MH/SUD parity compliance and annually publishes reports of these exams and the actions taken to address violations; improving the process for consumers to report suspected parity violations; and developing processes for data collection and public reporting of filed and investigated complaints (GBHRIC 2021). Additionally, on April 4, 2022, Governor Kemp signed the Mental Health Parity Act5 into law, which provides for the state to enact the commission’s recommendations and provide for enforcement of MHPAEA.

During interviews with advocates in Georgia, they expressed concern about the lack of a state parity law and that the state has not expanded Medicaid. Although the state recently passed a parity law, the political climate in Georgia makes it unlikely that the state will soon expand Medicaid access, which could increase insurance coverage for low-income single adults with MH/SUDs (Dey et al. 2016). In 2022, Georgia has a Republican trifecta, controlling the governorship and both houses of the legislature. During his 2018 gubernatorial campaign, Governor Kemp expressed vehement opposition to Medicaid expansion. In 2019 the Georgia legislature passed a law authorizing the state to seek expansion of Medicaid up to 100% of the federal poverty level. Governor Kemp’s proposal, initially accepted by the Trump administration, included work requirements. Subsequently, the Biden administration rejected the proposal, and Georgia filed a lawsuit in January 2022 (Brown 2022).

Massachusetts

In 2021, 21.2% of Massachusetts residents were enrolled in private insurance plans subject to oversight by the state’s insurance commissioner’s office and required to comply with MHPAEA (AHIP 2021). The Division of Insurance, an agency within the Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation, oversees health insurers. As part of their annual rate and form filing, insurers in Massachusetts are required to include an attestation form affirming that the company’s plans have been evaluated and are in compliance with MHPAEA (Commonwealth of Massachusetts 2022).

Enforcement Context and Actions.

In June 2018 the Division of Insurance filed a report on its evaluation of health insurers’ provider directories. The division reviewed networks for primary care providers, seven types of behavioral health facilities, and 10 types of behavioral health clinicians (HCAB 2018). This review was conducted in response to consumer and advocate concerns about inaccuracies in these directories regarding providers’ ongoing network participation, acceptance of new patients, treatment of directory-listed conditions, and current contact information.

An interviewee from the Division of Insurance explained that his office’s work on enforcement of MH/SUD parity is part of a larger portfolio addressing shortcomings in the behavioral health system. He said his office has worked closely with the state’s Executive Office of Health and Human Services, the Department of Mental Health, and MassHealth (Massachusetts’ Medicaid program) during the previous 10 years to identify and address system-level problems. The emphasis on broader issues, he explained, has meant not taking a specifically targeted approach to enforcement of MH/SUD parity.

Additional Government Actions.

Currently, Massachusetts has a divided government, with a Republican governor and a Democratic legislature and attorney general. Despite differences in political party, MH/SUD treatment access is a concern for all three groups. For the FY19 budget proposal, Governor Charlie Baker included an $83.8 million funding increase to the Department of Mental Health (EOHHS 2018). Additionally, in March of 2022 he unveiled legislation to broaden access to mental health services. Attorney General Maura Healy’s office investigated residents’ challenges in accessing behavioral health services, resulting in agreements with five insurers (and two companies managing behavioral health services for insurers) in 2020 regarding MH/SUD parity and provider directories. In addition to considering MH/SUD parity violations, the attorney general’s office also considered insurer conduct under consumer protection law.

In the legislature, the state senate unanimously passed a bill in November of 2021 to guarantee residents access to free mental health wellness exams annually and strengthen enforcement of MH/SUD parity. The bill is now with the state house of representatives, with the legislature’s official session ending July 31. Advocates have been hopeful that a change in leadership in the house might promote more action on bills to expand access to MH/SUD treatment.6

Rhode Island

In 2021, approximately 15% of Rhode Islanders were enrolled in plans that were required to comply with parity and that were overseen by the state insurance office (AHIP 2021). The Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner (OHIC) within the Department of Business Regulation oversees health insurers. The General Assembly passed legislation in 2004 to create the office, becoming the only state in the nation with a designated insurance office specifically for the oversight of health plans. One of the office’s requirements is to “monitor the adequacy of each health plan’s compliance with the provisions of the federal Mental Health Parity Act, including a review of related claims processing and reimbursement procedures”7

Enforcement Context and Actions.

As part of health plans’ annual filings, OHIC reviews rate and plan documents to ensure compliance with state and federal laws including MHPAEA. One form requires attestation of compliance with federal MH/SUD parity. Additionally, OHIC recently completed targeted market conduct exams of four insurers, specifically evaluating MH/SUD parity compliance. As part of this process, examiners reviewed insurers’ policies and procedures for utilization review and ensuring MH/SUD parity compliance. They also required records of utilization review decisions. Examiners reviewed these records for procedural and nonclinical compliance and enlisted expert behavioral health clinicians to determine clinical appropriateness of decisions, including utilization review criteria and requiring clinical decisions (OHIC 2022).

An area of particular concern for advocates is public knowledge about their rights under MHPAEA. The director of the Rhode Island Parity Initiative (RIPI) explained that a large part of their agenda is public education and that without this education, individuals cannot adequately advocate for themselves and do not access assistance with issues like claim denials. The initiative uses multiple formats to share information with the public, including radio ads, ads inside and outside of public buses, and distribution of materials in medical offices and social service agencies. In addition to education about parity itself, RIPI and the Rhode Island Parent Information Network (RIPIN) work to ensure that residents are aware of a help line operated by RIPIN that helps citizens with denied claims for behavioral health services. The help line is not specific to parity, but it deals with parity violations and serves as the complaint line for OHIC.

Additional Government Actions.

In 2004, the legislature created the Health Insurance Advisory Council to “obtain information and present concerns of consumers, business, and medical providers affected by health insurance decisions” (HIAC 2005). Their 2020 report to the legislature says access to mental health and substance use disorder treatment has been a priority for the council, and it highlights OHIC’s work to ensure MH/SUD parity (HIAC 2020). Additionally, in February of 2021, H5546 was introduced in the Rhode Island House of Representatives. This bill would have required behavioral health provider reimbursements to increase over five years at 4% per year. It died in the House Health and Human Services Committee, with the recommendation that it be held for additional study. At this time, it is unclear whether this bill will be reintroduced and could gain sufficient support to become law. Rhode Island has been one of the most reliably Democratic states in the nation for the past 50 years. However, more progressive Democrats have been pushing against what they consider governance by moderate Democrats. It is uncertain how progressive candidates could impact residents’ access to MH/SUD services or change processes for parity enforcement (Nesi 2020).

West Virginia

In 2021, 27% of West Virginia’s population was covered by Medicaid. Approximately 9% of residents were enrolled in commercial plans that were required to comply with MHPAEA and that were subject to state oversight (AHIP 2021). The Offices of the Insurance Commissioner (OIC) are responsible for oversight of commercial insurers. There are multiple divisions within OIC, but the ones most relevant for enforcement of MHPAEA include the subdivision of Company Analysis and Examinations for market conduct, and the Rates and Forms Division (OIC n.d.).

Enforcement Context and Actions.

In market conduct exams, the subdivision examines compliance with MHPAEA per the National Association of Insurance Commissioners Market Regulation Handbook (NAIC 2022). Reviewers examine a sample of 20 paid claims and 50 denied claims for MH/SUD treatment. In a 2020 report of the market conduct examination of Health Plan Group, the evaluation of parity compliance notes that legislation was introduced in both houses of the legislature (which subsequently passed) placing greater emphasis on verification that behavioral health claims are addressed “fairly” and in alignment with state and federal guidelines (OIC 2020a). In an interview with staff from OIC, a market conduct examiner explained that in addition to claims review, they communicate with insurers to understand their procedures for claims processing and review.

While market conduct examinations happen retrospectively, the rates and forms section evaluates plans prospectively when they file their annual paperwork. A staff member in this section explained that they look for compliance with both state and federal parity. She also stated that during the filing season she has regular contact with the insurers and works with them to ensure documentation and paperwork is in order rather than rejecting forms if there are errors or omissions. For example, she said that if she notices an error while looking at filings, she asks them to correct it or to “try again” rather than start over.

Additional Government Actions.

West Virginia has a Republican governor and Republican majorities in the senate and house of delegates. However, since 2014, it has the highest overdose mortality rate in the country, with a high of 57.8 per 100,000 reported in 2017 (CDC 2021). During January–August of 2020 (the first eight months of the COVID-19 pandemic), overdose deaths increased 52.9% compared to the same period in 2019. As a result, access to treatment for SUDs remains a high priority issue in the state (NCHS 2021). Potentially because of the rates of overdose deaths, there has been movement in the legislature and executive agencies to improve access to treatment and improve parity.

In February of 2020, the legislature passed a comprehensive MH/SUD parity law that applies to all insurance plans regulated by the state and the West Virginia Public Employees Insurance Agency (PEIA).8 Previously PEIA filed for, and was granted, exemptions from compliance with MHPAEA. The head of PEIA testified against the bill in a committee hearing, expressing his belief that the agency provided parity in most senses, except for treatment of gender dysphoria, so he felt the bill was unnecessary. However, the bill’s sponsor responded that he felt it was necessary to ensure access to MH/SUD services (Stuck 2020).

To educate the public, the Department of Health and Human Resources website has a page presenting information on the meaning of MH/SUD parity and telling how to identify the appropriate oversight agency depending on the type of health insurance. The page also includes contact information for oversight agencies as well as other resources, including a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services fact sheet and information for the Judge Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. However, it is difficult to find this page through the website; it only turns up when searching for “mental health parity.”

Cross-Case Analysis

Although states differed in terms of insurance commissioner office structure and the number of people covered by commercial plans that were subject to both federal parity and state insurance commissioner office oversight (table 1), we identified common themes affecting MHPAEA enforcement. These themes were present across states with both high and low staffing per capita. Although the overarching themes were common, there were differences in the manifestation of themes across states. The three common overarching themes, along with six subthemes summarized in table 3, include insurance commissioners’ offices’ relationships with other stakeholders, policy complexity, and policy champions.

Table 3.

Summary of themes and subthemes

| Theme | Description | Sample Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Relationships | ||

| With other state offices | Formal and informal relationships with other state government agencies | There’s lots of areas where we have overlapping jurisdiction and it’s really just a matter of coordination to decide who has the tools that are most effective to solve this problem and if both sets of tools are necessary, then we might proceed in parallel |

| With advocates and professional organizations | Communication and informal relationships with MH/SUD advocacy and professional organizations | My organization has been meeting with [the Division of Insurance] about mental health parity implementation since 2014… |

| With insurers | Working relationship with insurers selling plans within their state | We kind of make a habit of not denying filings, we want to work with the company to get the best possible product out to our consumers. |

| Policy Complexity | ||

| Interpretation of the law | Lack of clarity about the meaning or application of parts of MHPAEA | I think the hardest part for everyone is knowing what parity specifically means and I think we do understand that there is guidance from the federal government, but even some of that guidance is confusing |

| Necessary expertise | Required legal or content knowledge to understand or enforce MHPAEA | We did reach out to clinical advisors, but to have someone with that area of expertise, which is pretty specialized to, look at the criteria and evaluate it and give us their opinions both on the criteria or how the criteria are being applied, and then to give us an opinion on parity issue too. |

| Public education | Public knowledge of applicability and protections under MHPAEA | People didn’t understand that we had both state and federal mental health parity laws that we’re required to abide by and that without that public education patients weren’t adequately advocating for themselves |

| Political Priority | Prioritization of enforcement of MHPAEA by insurance commissioners’ offices, legislators or other political actors | It kind of depends on the individual and what their aspirations or are they just put in the position to hold a spot or are they someone who’s gung-ho and really wants to be involved. |

Relationships with other stakeholders

Interviewees in all four states perceived that relationship dynamics with other stakeholders influenced enforcement of MHPAEA. These included relationships between insurance commissioners’ offices and other government offices, relationships between state insurance commissioners’ offices and mental health advocates or professional organizations, and relationships between state insurance commissioners’ offices and insurers.

Insurance Commissioners’ Offices and Other Government Offices.

In Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and West Virginia, the insurance commissioners’ office staffs described having a variety of relationships with other state offices. While Massachusetts reported regular communication with the attorney general’s office, the health department, and the department of mental health, West Virginia mentioned having minimal contact with the attorney general’s office and making use of resources and support provided by the federal Department of Labor. In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, instances where offices communicated or worked together to enforce federal parity included sharing information (what types of parity complaints were received) and problem solving (leveraging knowledge or experience). For example, a staff member in the Massachusetts Attorney General’s office reported: “There are various consumer and patient privacy rules and other things that … limit a little bit the formal sharing of information. … But we get on the phone and we can sort of share trends. ‘And we’re hearing a lot about this issue. Is this something on your mind? And you’re hearing about this. Is this something that we’re hearing about?’”

Additionally, a staff member in Rhode Island’s Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner explained that they may leverage the clinical knowledge of their state’s mental health department and the department responsible for intellectual disability services to help make determinations about whether an insurer’s authorization criteria are appropriate.

Insurance Commissioners’ Offices and Advocacy or Professional Organizations.

Coalitions of consumer advocacy groups, provider organizations, and legal advocates were present in Georgia (Georgia Parity Collaborative), Massachusetts (Massachusetts Mental Health and Substance Use Parity Coalition), and Rhode Island (Rhode Island Parity Initiative). As part of their work, they sought relationships with state insurance commissioners’ offices to advocate for enforcement of MHPAEA and for their inclusion in discussions of enforcement. Interviewees in government offices stated that advocacy organizations can be useful sources of information about potential federal parity violations and behavioral health treatment coverage. These organizations communicate regularly with individuals and families seeking treatment and are knowledgeable about MHPAEA. As a result, they are well positioned to recognize common issues that arise, assess possible parity violations, and pass this information to the appropriate state office. This relationship was described by an interviewee from an advocacy organization in Massachusetts: “My organization has been meeting with [the Division of Insurance] about mental health parity implementation since 2014 or before, and more recently, the Division of Insurance has been holding more meetings and what they call public listening sessions about mental health parity and implementation.”

Also in Massachusetts, the insurance commissioner’s office’s relationships with advocacy and professional organizations led the office to include advocates and professionals on a committee to review insurers’ behavioral health provider networks. Additionally, in Georgia, an advocate with the National Alliance on Mental Illness discussed attending virtual and phone meetings with the organization’s executive director and the insurance commissioner at the governor’s direction.

Insurance Commissioners’ Offices and Insurers.

The staff in insurance commissioners’ offices in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and West Virginia described working relationships with insurers. Interviewees in these states said these relationships are relatively standard, with communication around licensure, filing of required documentation, and market conduct examinations. In West Virginia they also explained that the small size of their health insurance market and the need to keep insurers in the market factored into their relationship. As such, there is incentive for both insurance commissioners’ office staff and insurers to maintain a nonadversarial relationship. This balance was exemplified by one of the West Virginia insurance commissioner’s office interviewees, who explained that they aim to have proactive interactions with insurers while ensuring fair treatment of citizens. She stated: “This goes to our solid relationship with our carriers, but if [a filing error is] caught on the front end, we pick up the phone and call them and say, “No, try again.” We kind of make a habit of not denying filings. We want to work with the company to get the best possible product out to our consumers.”

Additionally, a staff member of a national health insurer explained that their relationship with insurance commissioners’ offices varied, with some taking West Virginia’s collaborative approach, and others taking an adversarial approach. He also explained that some departments’ staff are uniform in their approach and mentality to working with insurers, whereas others are not: “If you have one person that you’re dealing with for a couple years, you may develop a working relationship and give-and-take and understanding.”

One way that state insurance commissioners’ offices and insurers communicate is through formal written notices. For example, in May of 2013, the Massachusetts commissioner of insurance released Bulletin 2013–06 informing consumers and insurers about insurers’ responsibility to provide information about enrollees’ rights under federal and state MH/SUD parity, the requirement that all insurers certify and affirm compliance with MH/SUD parity laws, and how the Division of Insurance handles complaints about insurers’ potential noncompliance.9 Similarly, the West Virginia Offices of the Insurance Commissioner notified insurers of a 2020 MH/SUD parity law making changes to benefit requirements and the need to ensure compliance (OIC 2020b).

In Massachusetts, a staffer with a legal advocacy organization questioned the nature of the relationship between the health insurers in the state and the insurance commissioner. He expressed concern about the potential for insurers to co-opt the regulatory process and decrease the effectiveness of regulations to protect consumers stating: “I think the challenge that we see with the Division of Insurance is that they—it feels a little bit like regulatory capture. Like, they’re a little bit cozy with the insurers and so, they don’t—so, that’s one kind of challenge.”

Policy Complexity

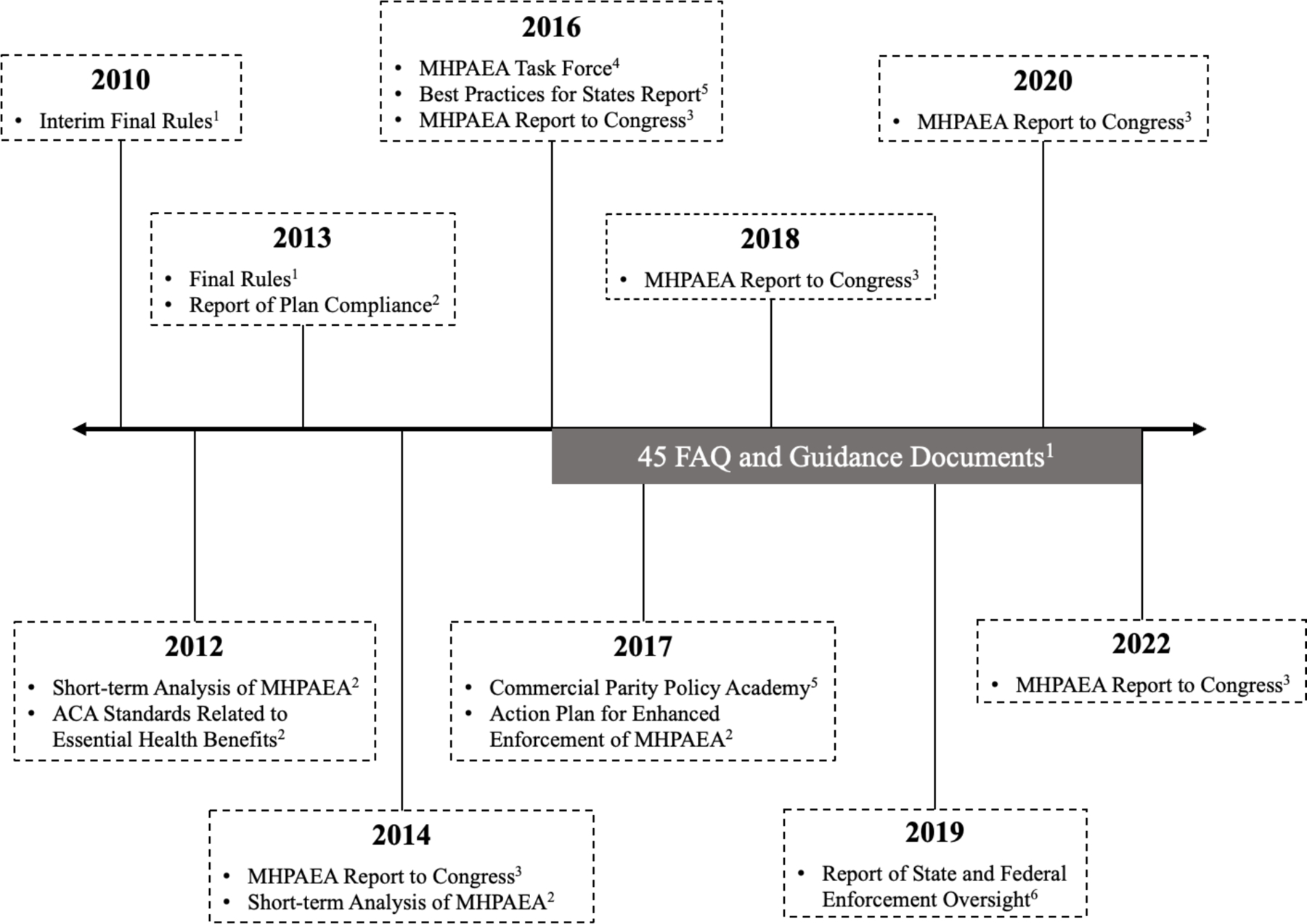

A second issue interviewees identified as influencing federal parity enforcement across all cases was the complexity of MHPAEA’s language. To assist insurers and states enforcing the law, the federal Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Treasury provide guidance documents on their websites on an ongoing basis, most commonly in the form of FAQs. In addition to providing guidance on the law in general, the FAQs also provide guidance related to new federal laws or rules that impact MHPAEA. For example, the FAQs from April 2, 2021, explain how the Consolidated Appropriation Act of 2021, part 45 amends MHPAEA and provides new protections. Interviewees noted that the need for ongoing guidance on the original law, combined with the need for extensive and continuous updates and reports from multiple federal agencies (fig. 1), is indicative of the difficulty of applying the law in general (determining what specifically to evaluate and how to evaluate it) and in specific cases (comparability of specific clinical services between MH/SUD treatment and medical/surgical treatment) as well as the challenges posed for compliance and enforcement. Within the context of the complexity of the policy, three subthemes were identified: interpretation of the law, necessary expertise, and public education.

Figure 1.

Federal Government MHPAEA Regulations, Reports, and Guidance Documents

1 Departments of Labor and Health and Human Services, and the IRS

2 Department of Health and Human Services

3 Department of Labor

4 Office of the President

5 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

6 Government Accountability Office

Note: MHPAEA = Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act.

Interpretation of the Law.

One concern about the law’s language is that parts are vague and unclear in application. For example, the law requires that any limitations placed on benefits for behavioral health treatment be equal to the limitations placed on treatment of medical conditions or on surgical services. For quantifiable factors, this is straightforward. Financial limitations such as copayment amounts, or limits on treatment access such as the number of allowed days of inpatient treatment, need to be applied in the same way to behavioral health benefits as they are applied to medical/surgical benefits. However, the final rules affirm that equivalence must also apply to NQTLs, such as prior authorization requirements or care management strategies.

Interpretation of what constitutes an NQTL and how to assess equal coverage was a challenge for Rhode Island, as one insurance commissioner’s office staff member pointed out:

What’s comparable on the behavioral health side to the medical side, and the federal government, as you know, has a parity tool, but we just don’t find it really very useful. It talks about nonquantitative treatment limitations in a class of mental health and substance use disorder benefits needing to apply to substantially all the medical/surgical benefits in that class, and it’s just really—it feels like you’re comparing apples to oranges, and so that’s been a challenge. How do you really measure parity without comparing apples to apples, or at least apples to crabapples?

NQTLs present a particular challenge, as explained by a national insurer’s staff member:

When you talk about the NQTL standard of “It has to be comparable,” what does that mean? If I go down to the parking lot and pick out two cars, I’m a reasonably well-trained lawyer, so I could argue that they are comparable because they both have four tires, internal combustion engine, et cetera, and I can also argue they’re not comparable because one is a Mercedes and one is a Prius and one is red and one is blue. Depending on what you define comparability to mean or what factors you look at, you can have differing and both reasonable interpretations of whether it is comparable.

An additional challenge of NQTLs is that they are not always readily visible to regulators, consumers, and providers. Not only is it hard to compare “apples to oranges,” it also is hard to identify which things to compare. A professional organization representative in Massachusetts explained: “One of the biggest challenges is you have to know what questions to ask to get the necessary data to demonstrate that parity isn’t happening, because health plans aren’t just gonna hand that over, and that’s been one of the hardest things to figure out.”

Necessary Expertise.

In addition to interpretation challenges, insurance commissioners’ offices also discussed challenges associated with trying to determine whether insurers are complying. Interviewees in Massachusetts and Rhode Island explained that determining whether medical/surgical services are comparable to behavioral health services requires clinical knowledge. In all four cases, none of the insurance commissioners’ offices had a clinician designated to make these determinations. One interviewee who worked on staff in the Rhode Island insurance commissioner’s office also noted that finding someone with sufficient expertise about the breadth of medical/surgical services and their levels of care, along with behavioral health services and their levels of care, poses a unique challenge. She described the insurance commissioner’s office’s need to involve clinical advisors:

You sort of need a clinic—you do need a clinic. We did reach out to clinical advisors, but to have someone with that area of expertise, which is pretty specialized, to one, look at the criteria and evaluate it and give us their opinions both on the criteria or how the criteria are being applied, and then to give us an opinion on the parity issue too. There again, someone could say they’re cherry picking or whatever if they find it’s not in parity because it’s just similar to a patient needing this medical-surgical medication. I guess it’s possible for a carrier to come back and say, “Well, but we have some other medical-surgical medication that it is comparable to.”

Public Education.

Advocates, representatives of professional organizations, and insurance commissioners’ office staff across all four states described a lack of public knowledge about the parity law, especially regarding its application to their insurance. Given that insurance commissioners’ offices and attorneys general’s offices mentioned complaints as one way that problems are identified, a public that lacks knowledge of what may constitute a parity violation and where to report their complaints is problematic. Additionally, there are some processes that may be visible to providers regarding authorizations or approvals that are not visible to patients.

Information about MH/SUD parity was available to consumers in a number of settings. In Massachusetts, for example, health plans are required to provide information to subscribers about their rights under MH/SUD parity. One insurer has a page on their website informing enrollees of their rights and providing information about claims appeals and how to file a complaint with the Division of Insurance (Tufts Health Plan 2021). Additionally, the parity coalitions in Georgia, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island provide educational materials for consumers on their websites. Health Law Advocates, a nonprofit public interest law firm, provides a “parity tool kit” that includes information about state and federal MH/SUD parity laws, specifics about filing complaints by type of coverage, and sample letters to send to insurers (Health Law Advocates 2017). One advocacy organization staffer in Rhode Island emphasized the importance of public education:

The first year of the initiative was really a lot about public education. We realized that people didn’t understand that we had both state and federal mental health parity laws that we’re required to abide by and that without that public education, patients weren’t adequately advocating for themselves. … You say “mental health parity,” and the average person trying to access behavioral health care doesn’t know what you’re talking about, so that was a big piece and one prong of the initiative’s work, ongoing piece of work for us.

Policy Champions

Another topic that arose in all four cases was the role of policy champions in the enforcement of MHPAEA. Policy champion in this case refers to a policy maker in an executive or legislative position who considers MH/SUD parity as a priority issue. Across states, policy champions were not specific to a political party as much as they were to the personal priorities/platforms of the specific policy makers. Depending on the powers associated with a policy champion’s role, examples of their actions included allocating financial or manpower resources (insurance commissioners, state legislatures), instructing state insurance commissioners’ offices to produce specific analyses or reports (insurance commissioners, legislatures, governors), or conducting targeted investigations of health plans (insurance commissioners, attorneys general).

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, there was interest in parity enforcement from insurance commissioners’ offices, attorneys general’s offices, and state legislators. The attorney general in Massachusetts acted on MH/SUD parity enforcement in early 2020, reaching settlements with four health insurers. In Rhode Island, the representative from the attorney general’s office noted that they had not recently worked specifically on this issue but that they were interested in pursuing it more actively.

In Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and West Virginia the insurance commissioners’ offices discussed how heads of their offices influence how much of a priority MHPAEA enforcement is relative to the rest of their duties. In both Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the current commissioners have expressed investment in MH/SUD parity enforcement. In both states, this investment can be seen directly in actions taken by the office, such as targeted market conduct examinations in Rhode Island and convening a committee to study behavioral health provider directories in Massachusetts. In West Virginia, the insurance commissioner’s office staff explained that commissioner priorities have varied over time, and that because the governor appoints the position, the commissioner is beholden to the governor to stay in office. One staff member in the Rhode Island insurance commissioner’s office stated:

Because the commissioner here is appointed, he can stay as long as the governor is satisfied with his performance. Each one of these appointees brings their own life experience to the table. The current commissioner that we have has a legal background, and the one prior to him had more of a marketing background. So that kind of steers the ship in different directions based on their own life experience.

Policy champions can also advocate for prioritization of MHPAEA enforcement through budget allocations. However, from 2015 through 2019, the percentage of each state’s budget allocated to the agency that oversees insurance decreased (6.5% in Massachusetts, 15.1% in West Virginia, 15.5% in Georgia, and 26.4% in Rhode Island), with the number of staff across the department also decreasing in three of the four states. Resource allocation is critical to MHPAEA enforcement, as one staff member in the Rhode Island insurance commissioner’s office explained: “That, again, took us over four or five years, and we’re not done. And then even the question of how do you—I’m not saying they aren’t going to be complying, but then to go back in to see if they are complying is almost like doing another examination, which could take a whole team of people another five years, because we don’t have anyone dedicated just to doing that.”

Discussion

This study aimed to identify state-level factors that influence state insurance commissioners’ enforcement of MHPAEA. Our findings indicate enforcement challenges and opportunities, including insurance office relationships with other stakeholders, the complexity of MHPAEA, and the presence of a policy champion among influential government officials. Interviewees identified these factors as important across all four cases.

Insurance commissioners’ offices benefited from relationships with other state offices through shared information and leveraging of expertise. Public administration literature broadly considers interagency collaboration desirable for effective governance, especially with increasingly complex tasks (Hudson et al. 1999). However, coordination between entities varies dramatically depending on the context (Hudson et al. 1999). Although insurance commissioners’ offices enforce MH/SUD parity, the law’s complex nature suggests that expertise and information from other offices (e.g., a mental health department or state attorney general’s office) may be required for comprehensive enforcement.

In a 2017 study, Purtle et al. found that the number of state mental health agencies that anticipated contributing to MHPAEA enforcement decreased from 28 in 2010 to only 6 actually participating in 2015. The most common reason for state mental health agencies to collaborate on insurance commissioners’ MHPAEA enforcement was to share expertise in MH/SUD treatment and services. In the discussion, the authors speculate that resource constraints (time or financial) and resistance to collaboration from insurance commissioners’ offices may have contributed to the low engagement of state mental health agencies in MHPAEA enforcement (Purtle et al. 2017).

Our findings suggest that some insurance commissioners’ offices recognize the need for, and the benefit of, expert knowledge possessed by other stakeholders. Interviewees in Massachusetts discussed ongoing communication with other state offices, and in Rhode Island they acknowledged the value of leveraging outside clinical expertise. While these collaborations do not speak to the effectiveness of these states’ enforcement efforts, those states were the most active in terms of actions taken to enforce MHPAEA. Whether this association suggests that collaboration increases insurance agencies’ enforcement activities warrants further investigation.

Another area for future study is whether a formal, centralized body to assess and respond to potential parity violations would improve state enforcement of MHPAEA. The goals would be to (1) provide clinical knowledge of MH/SUD treatment and medical/surgical services, along with policy/legal knowledge to interpret MHPAEA and other relevant state and federal insurance laws; (2) support insurance office efforts to improve enforcement processes (e.g., refining documentation requested of insurers about MHPAEA compliance, updating questions regarding NQTLs); and (3) maintain dialogue with other state/federal bodies with similar functions to share knowledge of compliance issues in other jurisdictions and increase uniform interpretation and application of MHPAEA across states. Whether created by a legislature or an executive agency, this structure could be tailored to the particular needs and resources of individual states.

An additional consideration for contextualizing the findings of this study is whether enforcement is tied to political party affiliation. The most active enforcement was in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, states with strong Democratic constituencies, while Georgia and West Virginia, with less active enforcement, are both Republican-dominated states. However, research on political partisanship and support of legislative intervention in MH/SUD parity presents a nuanced picture.

In a 2019 study, Purtle et al. examined whether state legislators’ support for MH/SUD parity laws was influenced by fixed characteristics (gender, political party, ideology), mutable factors (beliefs about the impact of MH/SUD parity laws, treatment efficacy, stigmatizing attitudes) and state-level context (opioid deaths, unemployment, legislative partisanship). After adjusting for fixed characteristics and state context, legislators’ mutable characteristics were all significantly associated with support for MH/SUD parity laws. The only fixed characteristic significantly associated with support for MH/SUD parity laws was ideology, not party affiliation, with liberals most likely to support parity laws, and conservatives least likely (Purtle et al. 2019).

Whether Purtle et al.’s findings extend to other policy makers is unclear. However, the importance of legislators’ mutable factors in their support for MH/SUD parity laws may be factors in the recent passage of more comprehensive state MH/SUD parity laws in West Virginia and Georgia. As Purtle et al. suggest, targeting these mutable factors and tailoring messaging to policy makers’ ideology may prove effective in increasing support for MH/SUD parity enforcement. The recent passage of laws in West Virginia and Georgia also suggest additional research is necessary to understand state perspectives on what state MH/SUD parity laws accomplish that cannot be accomplished under the current federal law.

Finally, we studied states’ processes for enforcing MHPAEA. We did not assess those processes’ impact on insurer compliance or benefits for enrollees. Although Massachusetts and Rhode Island showed more active enforcement than West Virginia and Georgia, we did not evaluate whether that activity improved access to treatment services or health outcomes. Future research should examine the effectiveness of different enforcement approaches. Results from such a study could identify quantifiable enforcement measures to include in models of the overall impact of MHPAEA. These measures would allow evaluation of whether enforcement practices moderate the law’s impact, and whether MHPAEA can meaningfully increase access to care regardless of enforcement.

This study has several limitations. First, the case selection strategy may have missed drivers of enforcement variation present in other states. As a result of the lack of recommendations from insurance staff, nonresponse from other state offices, or an explicit statement that an office did not enforce parity, interviewees did not span the same offices across states. Additionally, the small range of roles among respondents from Georgia and West Virginia limited the ability to triangulate among informants; however, interviewee information was also triangulated with documentary evidence. The small size of the total sample limited our ability to ensure data saturation across states. Interviews were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. None of the government staff noted effects of the pandemic; however, it is possible that their answers were impacted by changes to workflows such as remote work or shifts in state government priorities. Selection of cases was based on per capita staffing in the state insurance office. However, other metrics, such as staffing relative to the number of insurers in each state or to the number of reviewed plans, could reveal differences in resources to enforce MHPAEA. A final limitation is the use of a single coder for all data. However, members of the study team reviewed interview guides and codebook design, and the codebook was piloted with a second coder to decrease potential bias. Additionally, to validate findings we conducted member-checking with individuals from all states.

Conclusion

Inconsistent state enforcement of MHPAEA is often cited as a concern with the law’s implementation, yet this is one of the first studies to examine factors impacting state-level variation in enforcement. Sources of enforcement variability across states included insurance commissioners’ offices’ relationships with other state offices, insurers, and advocates; the complexity of the law; and the presence of a government policy champion. Improved coordination among stakeholders could improve enforcement of MHPAEA. However, despite extensive guidance and reports, interpreting and applying the law remain significant obstacles to enforcement.

Acknowledgments

Rachel Presskreischer gratefully acknowledges support from the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH109436) and the Johns Hopkins Center for Qualitative Studies in Health and Medicine.

Appendix A

Case Selection

Specifically, the four cases were selected utilizing the National Association of Insurance Commissioners' 2019 Insurance Department Resources Report - Volume One (National Association of Insurance Commissioners 2020) to determine how many staff members are employed in insurance commissioners' offices in areas pertinent to enforcement of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. Categories of staff included were licensing, consumer affairs, and market conduct positions, as well as contracted employees. We then summed the total number of employees across those job categories and divided by the state population from the 2019 American Community Survey estimates (U.S. Census Bureau 2019) to calculate the number of insurance commissioner's office staff per capita.

Interview Domains

The primary domains in the interview guides for state agency staff were (1) agency enforcement activities, (2) barriers and facilitators to enforcement, (3) perception of the priority of enforcing parity within the state, and (4) collaborations between and within agencies to enforce parity. For advocates and professional organization representatives the interview domains were (1) advocacy actions, (2) perceived impact of parity on people with mental illness/substance use disorders, their families, and providers, (3) perception of state enforcement efforts, and (4) priority areas for enforcement efforts. The difference between the guide for state agency staff and advocates/professionals was the framing of questions. For agency staff, questions emphasized their offices' work to enforce MHPAEA, framing questions to be appropriate to the office (asking insurance commissioners' office staff about what actions they take to enforce MHPAEA vs. asking staff in attorneys general's offices about whether they take action). The questions for advocates/professionals emphasized perceptions of state agency actions and how they communicate information about the concerns of individuals and families.

Interview procedures

Interviewees were informed of the nature of the research and that their statements could be used in publications. Oral consent was obtained at the beginning of the interview which was subsequently audio recorded and transcribed. They were also informed that they could choose not to answer a question and stop the interview at any time if they wished. The researcher also informed interviewees that they would be provided with summaries of findings and any direct quotes that would be included in the manuscript prior to submission. The interviewer created summary memos following each interview, recording a recollection of the main points of the interview, first impressions of which concepts were most emphasized by interviewees, and initial thoughts about relationships between concepts in the interview and concepts mentioned in other interviews both within the same state and across states.

Initially, contact was made with each state's agency responsible for oversight of insurance, the state's Office of the Attorney General, state advocacy organizations working on issues related to MH/SUD parity enforcement, and state organizations representing behavioral health professionals' interests. Each interviewee was sent an email introducing the study and inviting them to participate. Non-responders were sent a follow-up email one week after the initial email.

Footnotes

Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974, 29 U.S.C. § 18.

“Parity in Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Benefits,” 29 U.S.C. § 1185a.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, §1302.

O.C.G.A. § 33–2-11.

Mental Health Parity Act (2022) HB 1013.

An Act Addressing Barriers to Care for Mental Health (2021) S.2572.

R.I. Gen. Laws § 42–14.5–3.

West Virginia Insurance Bulletin 20–13: Summary of 2020 Legislation. Issued June 8, 2020.

Bulletin 2013–06: Disclosure and Compliance Requirements for Carriers, and Process for Handling Complaints for Non-Compliance with Federal and State Mental Health and Substance Use Disorder Parity Laws, issued May 31, 2013.

Contributor Information

Rachel Presskreischer, Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health.

Colleen L. Barry, Cornell Jeb E. Brooks School of Public Policy

Adria K. Lawrence, Johns Hopkins University

Alexander McCourt, Johns Hopkins University.

Ramin Mojtabai, Johns Hopkins University.

Emma E. McGinty, Weill Cornell Medical College

References

- AHIP (America’s Health Insurance Plans). 2021. “Health Coverage: State-to-State 2021” May 3. https://www.ahip.org/resources/health-coverage-state-to-state-2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein Lenny. 2022. “Equal Mental Health Insurance Coverage Elusive Despite Legal Guarantee.” Washington Post, June 2. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2022/05/25/equal-mental-health-insurance-coverage-elusive-despite-legal-guarantee/. [Google Scholar]

- Block Eryn P., Xu Haiyong, Azocar Francisca, and Ettner Susan L.. 2020. “The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act Evaluation Study: Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health Service Expenditures and Utilization.” Health Economics 29, no 12: 1533–48. 10.1002/hec.4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Christopher. 2022. “Planned Medicaid Work Rules’ Impact at Heart of Georgia Lawsuit.” Bloomberg Law February 11. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/health-law-and-business/planned-medicaid-work-rules-impact-at-heart-of-georgia-lawsuit. [Google Scholar]

- Busch Alisa B., Yoon Frank, Barry Colleen L., Azzone Vanessa, Normand Sharon-Lise T., Goldman Howard H., and Huskamp Haiden A.. 2013. “The Effects of Mental Health Parity on Spending and Utilization for Bipolar, Major Depression, and Adjustment Disorders.” American Journal of Psychiatry 170, no. 2: 180–87. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch Susan H., Epstein Andrew J., Harhay Michael O., Fiellin David A., Un Hyong, Leader Deane Jr., and Barry Colleen L.. 2014. “The Effects of Federal Parity on Substance Use Disorder Treatment.” American Journal of Managed Care 20, no 1: 76–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch Susan H., McGinty Emma E., Stuart Elizabeth A., Huskamp Haiden A., Gibson Teresa B., Goldman Howard H., and Barry Colleen L. 2017. “Was Federal Parity Associated with Changes in Out-of-Network Mental Health Care Use and Spending?” BMC Health Services Research 17, no. 1: article no. 315. 10.1186/s12913-017-2261-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauchi Richard, and Hanson Karmen. 2015. “Mental Health Benefits: State Laws Mandating or Regulating.” National Conference of State Legislatures, December 30. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/mental-health-benefits-state-mandates.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021. “Drug Overdose Mortality by State” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm (accessed April 2021). [Google Scholar]

- CMS (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services). n.d. “The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act” https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Programs-and-Initiatives/Other-Insurance-Protections/mhpaea_factsheet (accessed May 1, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts. 2022. “Compliance Checklists and Filing Guidance” https://www.mass.gov/lists/compliance-checklists-and-filing-guidance (accessed September 19, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Dey Judith, Rosenoff Emily, West Kristina, Ali Mir M., Lynch Sean, Chandler McClellan Ryan Mutter, Patton Lisa, Teich Judith, and Woodward Albert. 2016. “Benefits of Medicaid Expansion for Behavioral Health.” DHHS, ASPE Issue Brief, March 28. https://mdsoar.org/bitstream/handle/11603/22030/BHMedicaidExpansion.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. [Google Scholar]

- EBSA (Employee Benefits Security Administration). n.d. “Public Comments: Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act Interim Final Rule” https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ebsa/laws-and-regulations/rules-and-regulations/public-comments/1210-AB30-2 (accessed September 19, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- EOHHS (Executive Office of Health and Human Services). 2018. “Governor Baker, HHS Secretary Sudders Meet with Mental Health Community to Highlight Investments in Behavioral Health Services” Press release, March 1. https://www.mass.gov/news/governor-baker-hhs-secretary-sudders-meet-with-mental-health-community-to-highlight-investments-in-behavioral-health-services. [Google Scholar]

- Frank Richard G., and McGuire Thomas G. 2000. “Economics and Mental Health.” In The Handbook of Health Economics, Volume 1, edited by Culyer Anthony J. and Newhouse Joseph P., 893–954. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Sarah, Xu Haiyong, Azocar Francisca, and Ettner Susan L.. 2020. “Carve‐Out Plan Financial Requirements Associated with National Behavioral Health Parity.” Health Services Research 55, no. 6: 924–31. 10.1111/1475-6773.13542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO (Government Accountability Office). 2019. “Mental Health and Substance Use: State and Federal Oversight of Compliance with Parity Requirements Varies” Publication GAO-20–150, December 13. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-150. [Google Scholar]

- GBHRIC (Georgia Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission). 2021. “First Year Report.: January. https://www.house.ga.gov/Documents/CommitteeDocuments/2020/BehavioralHealth/BH_Commission_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Goodell Sarah. 2015. “Health Policy Brief: Enforcing Mental Health Parity.” Health Affairs, Health Policy Brief, November 9. 10.1377/hpb20151109.624272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grazier Kyle L., Eisenberg Daniel, Jedele Jenefer M., and Smiley Mary L.. 2015. “Effects of Mental Health Parity on High Utilizers of Services: Pre-Post Evidence from a Large, Self-Insured Employer.” Psychiatric Services 67, no. 4: 448–51. 10.1176/appi.ps.201400586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HCAB (Health Care Access Bureau, Massachusetts Division of Insurance). 2018. “Summary Report: Market Conduct Exam Reviewing Health Insurance Carriers’ Provider Directory Information” June. https://www.mass.gov/doc/provider-information-report-6-12-2018/download. [Google Scholar]

- Health Law Advocates. 2017. “Health Law Advocates Mental Health Parity Toolkit” https://www.healthlawadvocates.org/get-legal-help/resources/document/HLA-MentalHealthParityToolkit_6_pub-3.15.17.pdf (accessed September 19, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- HIAC (Health Insurance Advisory Council). 2005. “Health Insurance Advisory Council Charter” September. http://www.ohic.ri.gov/documents/HIAC-Charter.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- HIAC (Health Insurance Advisory Council). 2020. “2020 Annual Report” https://ohic.ri.gov/sites/g/files/xkgbur736/files/documents/2020/2020-Annual-Report.pdf (accessed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer Richard. 2005. “Altering State Policy: Interest Group Effectiveness among State-Level Advocacy Groups.” Social Work 50, no. 3: 219–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan Constance M., Hodgkin Dominic, Stewart Maureen T., Quinn Amity, Merrick Elizabeth L., Reif Sharon, Garnick Deborah W., and Creedon Timothy B.. 2016. “Health Plans’ Early Response to Federal Parity Legislation for Mental Health and Addiction Services.” Psychiatric Services 67, no. 2: 162–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson Bob, Hardy Brian, Henwood Melanie, and Wistow Gerald. 1999. “In Pursuit of Inter-Agency Collaboration in the Public Sector.” Public Management 1, no 2: 235–60. 10.1080/14719039900000005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huskamp Haiden A., Samples Hillary, Hadland Scott E., McGinty Emma E., Gibson Teresa B., Goldman Howard H., Busch Susan H., Stuart Elizabeth A., and Barry Colleen L.. 2018. “Mental Health Spending and Intensity of Service Use among Individuals with Diagnoses of Eating Disorders following Federal Parity.” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 2: 217–23. 10.1176/appi.ps.201600516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Patrick J., and Ramstad Jim. 2019. “Landmark Ruling Sets Precedent for Parity Coverage of Mental Health and Addiction Treatment.” STAT, First Opinion, March 18. https://www.statnews.com/2019/03/18/landmark-ruling-mental-health-addiction-treatment/. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy-Hendricks Alene, Epstein Andrew J., Stuart Elizabeth A., Haffajee Rebecca L., McGinty Emma E., Busch Alisa B., Huskamp Haiden A., and Barry Colleen L.. 2018. “Federal Parity and Spending for Mental Illness.” Pediatrics 142, no. 2: e20172618. 10.1542/peds.2017-2618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). n.d. “Health Insurance Coverage of the Total Population.” State Health Facts https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/ (accessed May 23, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Kober Nancy, and Rentner Diane Stark. 2012. “State Education Agency and Staffing in the Education Reform Era.” Center on Education Policy, February. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED529269.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Markell David L., and Glicksman Robert L.. 2014. “A Holistic Look at Agency Enforcement.” North Carolina Law Review 93, no. 1: 1–76. [Google Scholar]

- Morse Janice M. 1995. “The Significance of Saturation.” Qualitative Health Research 5, no. 2: 147–49. 10.1177/104973239500500201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- NAIC (National Association of Insurance Commissioners). 2022. “Resource Center: Publications” 2022. https://content.naic.org/sites/default/files/publication-mes-hb-market-handbook-examination.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2021. “Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm (accessed April 2021). [Google Scholar]

- Nesi Ted. 2020. “Progressives Oust Multiple Incumbent Lawmakers in RI Primary.” WPRI 12 News, September 10. https://www.wpri.com/news/elections/progressives-oust-multiple-incumbent-lawmakers-in-ri-primary/. [Google Scholar]

- OCISF (Office of Commissioner of Insurance and Safety Fire ). n.d. “Insurance Product Filings—Life and Health” https://oci.georgia.gov/regulatory-filings/insurance-product-filings/life-health (accessed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- OHIC (Rhode Island Office of the Health Insurance Commissioner). “Market Conduct Examinations” https://ohic.ri.gov/regulations-and-enforcement-actions/market-conduct-examinations (accessed May 2021). [Google Scholar]

- OIC (West Virginia Offices of the Insurance Commissioner). 2020b. “Mental Health Parity SB291” June 5. https://www.wvinsurance.gov/Portals/0/Mental%20Health_1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- OIC (West Virginia Offices of the Insurance Commissioner). n.d. “Divisions” https://www.wvinsurance.gov/Divisions (accessed March 2021). [Google Scholar]

- OIC (West Virginia Offices of the Insurance Commissioner). 2020a. “Report of market conduct examination—Health Plan Group” https://www.wvinsurance.gov/Divisions_Market-Conduct (accessed September 19, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Pacewicz Josh. 2018. “The Regulatory Road to Reform: Bureaucratic Activism, Agency Advocacy, and Medicaid Expansion within the Delegated Welfare State.” Politics and Society 46, no. 4: 571–601. 10.1177/0032329218795850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Purtle Jonathan, Borchers Benjamin, Clement Tim, and Mauri Amanda. 2017. “Inter-Agency Strategies Used by State Mental Health Agencies to Assist with Federal Behavioral Health Parity Implementation.” Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research 45, no. 3: 516–26. 10.1007/s11414-017-9581-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]