Abstract

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common chronic liver disease worldwide and macrophage polarization plays an important role in its pathogenesis. However, which molecule regulates macrophage polarization in NAFLD remains unclear. Herein, we showed NAFLD mice exhibited increased 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7 (17β-HSD7) expression in hepatic macrophages concomitantly with elevated M1 polarization. Single-cell RNA sequencing on hepatic non-parenchymal cells isolated from wild-type littermates and macrophage-17β-HSD7 knockout mice fed with high fat diet (HFD) for 6 weeks revealed that lipid metabolism pathways were notably changed. Furthermore, 17β-HSD7 deficiency in macrophages attenuated HFD-induced hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance and liver injury. Mechanistically, 17β-HSD7 triggered NLRP3 inflammasome activation by increasing free cholesterol content, thereby promoting M1 polarization of macrophages and the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. In addition, to help demonstrate that 17β-HSD7 is a potential drug target for NAFLD, fenretinide was screened out from an FDA-approved drug library based on its 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase inhibitory activity. Fenretinide dose-dependently abrogated macrophage polarization and pro-inflammatory cytokines production, and subsequently inhibited fat deposition in hepatocytes co-cultured with macrophages. In conclusion, our findings suggest that blockade of 17β-HSD7 signaling by fenretinide would be a drug repurposing strategy for NAFLD treatment.

Key words: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, 17β-HSD7, Macrophage, Cholesterol, Insulin resistance, Fenretinide

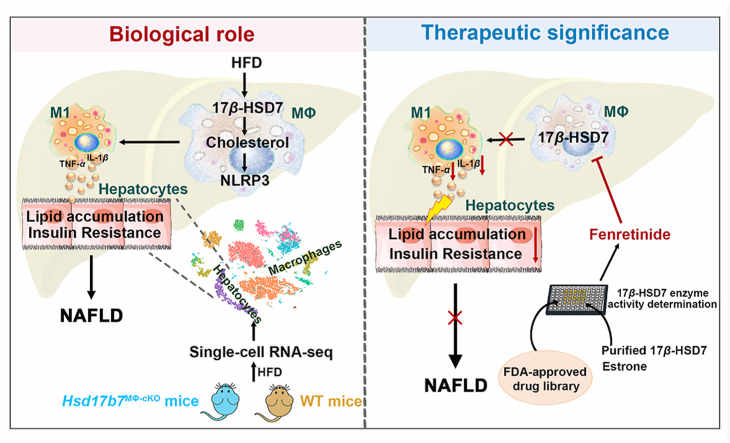

Graphical abstract

By increasing free cholesterol content, 17β-HSD7 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation and M1 polarization, ultimately resulting in NAFLD. Moreover, fenretinide reduces M1 polarization and further hepatocytes lipid accumulation through inhibiting 17β-HSD7.

1. Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to a group of conditions characterized by excessive fat accumulation in the liver, ranging from simple hepatic steatosis (NAFL) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), an aggressive histological form, ultimately leading to advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis1. At present, the prevalence of NAFLD is approximately 25% and projected to rise rapidly up to 56% over the next decade due to the worldwide obesity epidemic2. However, there are no approved pharmacological agents for NAFLD, and the available treatments only aim to control associated conditions, which are far from satisfactory3. Therefore, a better understanding of the pathophysiology of NAFLD and the identification of novel druggable targets, are of the utmost importance.

The widely accepted pathogenesis of NAFLD is the ‘two-hit theory’. Steatosis represents the ‘first hit’ of the liver, and in the ‘second hit’, steatosis advances into steatohepatitis, which additionally includes inflammation and oxidative stress. Actually, it has been documented that inflammation may also promote steatosis4, suggesting a complex interaction between lipid metabolic disturbance and inflammation. Therefore, exploring the key molecules that connect inflammation and steatosis may provide new targets for inhibiting the progression of NAFL to NASH. As the most abundant and important innate immune cell group in the liver, hepatic macrophages can differentiate into pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype M1 and anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype M2 according to hepatic microenvironment5,6. M1 macrophages play a critical role in triggering the liver inflammatory response in NAFLD by secreting pro-inflammatory cytokines7. In contrast, M2 macrophages promote the resolution of inflammation in NAFLD8. It has been reported that pro-inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), could promote insulin resistance (IR) and the dysfunction of lipid metabolism in the liver9, 10, 11. Meanwhile, anti-inflammatory cytokines secreted by M2 macrophages could promote lipolytic events and inhibit lipogenic enzymes in the liver12. These indicate that molecules regulating macrophage polarization have effects both on lipid metabolism and inflammation in the liver and may serve as important mediators driving NAFL to NASH. However, how macrophage polarization is regulated in the context of NAFLD pathophysiology needs to be further elucidated.

It was reported that cholesterol synthesis pathways were up-regulated in the macrophages of mice with metabolic diseases13, 14, 15. Another study showed that macrophages isolated from the liver of NAFLD mice were rich with free cholesterol16. Therefore, cholesterol synthesis-related molecules may mediate macrophage polarization, in turn be targets for NAFLD treatment. 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7 (17β-HSD7) is encoded by Hsd17b7, which can catalyze the conversion of zymosterone to zymostero, participating in the biosynthesis of cholesterol17. More importantly, Jokela et al.18 found that Hsd17b7 depletion-induced decreased cholesterol could not be efficiently compensated by other cholesterol biosynthetic enzymes, indicating that 17β-HSD7 is irreplaceable for cholesterol synthesis and suggesting a possible involvement of 17β-HSD7 in modulating macrophage polarization. In addition, researches showed that 17β-HSD7 was highly expressed in the livers of humans and mice19,20. However, the potential role of 17β-HSD7 in liver-related diseases has rarely been reported. Based on the BioGPS gene expressing database, we noticed that Hsd17b7 was highly expressed in macrophages, and the inflammatory stimulation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increased Hsd17b7 mRNA expression (Supporting Information Fig. S1). These led us to test the hypothesis that 17β-HSD7 could be involved in macrophage polarization and NAFLD development and targeting 17β-HSD7 might ameliorate NAFLD.

In this study, we reported that 17β-HSD7 expression was significantly increased in macrophages concomitantly with elevated hepatic M1 polarization in HFD-fed mice. Moreover, knockout of Hsd17b7 in macrophages attenuated HFD-induced NAFLD and M1 polarization relying on decreasing free cholesterol content. Furthermore, fenretinide, showing inhibitory effect on 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase, decreased hepatocytes lipid accumulation through inhibiting M1 polarization. Our results suggest that 17β-HSD7 acts as a novel regulator of macrophage polarization and inhibition of 17β-HSD7 by fenretinide may represent a drug repurposing strategy for NAFLD treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Reagents

Anti-F4/80-FITC, anti-CD206-APC and anti-CD11c-PE were obtained from Biolegend (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-17β-HSD7 and anti-F4/80 were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, USA). Anti-CD11c and intracellular fixation kit and permeabilization buffer set were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA, USA). Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-Armenian hamster IgG was purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA, USA) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti rat IgG was purchased from Antgene (Wuhan, China). Anti-β-tubulin was purchased from Biopm (Wuhan, China). Goat anti-mouse IgG/PE antibody was purchased from Bioss (Beijing, China). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug library, fenretinide (purity >99%) and hydralazine HCl (purity >99%) were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA). Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), total cholesterol (TC) and triglyceride (TG) biochemical kits were purchased from Jiancheng Biotech (Nanjing, China). Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukins-1β (IL-1β), interleukins-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) ELISA kits were purchased from MultiSciences (Hangzhou, China). Oleic acid (OA) was purchased from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Dnase I and Oil Red O staining were purchased from Solarbio (Beijing, China). LPS, D-Hanks and Hanks balanced salt solution, red cell lysis buffer, collagenase IV, hematoxylin and imidazole were purchased from Biosharp (Hefei, China). Nickel-nitrilotriacetic (Ni-NTA) agarose column was purchased from Smart-Lifesciences (Changzhou, China).

2.2. Animal treatment

Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the Experimental Center of Hubei Medical Scientific Academy (No. 2015-0018, Wuhan, China). Hsd17b7fl/fl and Lyz2-Cre mice were both acquired from Gem Pharmatech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). To generate macrophage-specific Hsd17b7 knockout mice, Hsd17b7fl/fl mice were crossed with Lyz2-Cre mice, producing Lyz2-Cre+;Hsd17b7fl/– mice, which were subsequently crossed with Hsd17b7fl/fl to generate Lyz2-Cre+ Hsd17b7fl/fl (cKO) mice. The genotype of the mice was determined by PCR using tail tissues. The primer sequences used for genotyping are listed in Supporting Information Table S1. Western blot was used for verification at the protein level. Male cKO mice and WT littermates (7–8 weeks of age) were fed with normal chow diet (NCD, 11.9% kal fat), high-fat diet (HFD, 60% kal fat) or methionine- and choline-deficient diet (MCD) for 2, 4 and 6 weeks. Mice were bred at the Center for Animal Experiment of Wuhan University (Wuhan, China), which has been accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International). Animals were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle at 23 ± 1 °C with free access to food and water ad libitum. The protocols were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments at Wuhan University School of Basic Medical Sciences. All animal experiment procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the Chinese Animal Welfare Committee and the International Council on Research Animal Care.

2.3. Glucose and insulin tolerance testing (GTT and ITT)

For the GTT, mice were fasted overnight from 6:00 pm to 9:00 am, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of 1 g/kg glucose. For the ITT, mice were fasted from 8:00 am to 13:00 pm, followed by an intraperitoneal injection of 0.75 units/kg insulin. Blood from the tail vein was obtained before (0 min) and at 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after the injection to determine blood glucose using a glucometer (Roche, Mannheim, Germany).

Plotted with the blood sugar time curve, and calculate area under the curve (AUC), using the Tai's equation21:

| (1) |

2.4. Histopathological analysis

Mouse liver samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin and cut into sections of 4-μm thickness. The paraffin-embedded liver sections were stained with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) or Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) to evaluate histological changes22. Frozen sections were prepared from liver tissue frozen in OCT media and sliced into 5-μm thickness. Oil Red O staining was used to assess lipid accumulation in the liver. At least 3 liver sections were included in each group.

2.5. Immunofluorescence (IF) staining of liver sections

The paraffin-embedded liver sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and further proceed with antigen retrieval. After blocking with 5% BSA to prevent non-specific staining, the slides were incubated with anti-rat F4/80 (1:50) and anti-Armenian hamster CD11c (1:50) primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti rat IgG (1:100) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-Armenian hamster IgG (1:100) secondary antibodies were added to the sections to visualize the staining. DAPI was used for nuclear staining. Immunofluorescence images were acquired using a Leica-LCS-SP8-STED confocal laser-scanning microscope with 63× oil objective (Leica, Germany).

2.6. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-10 and TGF-β in the livers were detected using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.7. Biochemical analysis

The activity of serum ALT and AST, LDL-C, HDL-C, TC, TG, NEFA levels and hepatic TC, TG and NEFA levels were detected by biochemical kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.8. Flow cytometry

To prepare non-parenchymal cells from mouse liver, mice were anesthetized with 0.1 mL of 1% pentobarbital and the livers were perfused with 20 mL of pre-perfusion solution (D-Hanks solution containing 0.5% phosphatase inhibitor) and 20 mL of post-perfusion solution (Hanks solution containing 0.5% phosphatase inhibitor, 1% BSA, 0.05% collagenase IV, and 0.002% Dnase I) from the inferior vena cava at a flow rate of 5 mL/min. Then, the liver tissues were minced after the gall bladders were removed. Subsequently, the cell suspensions were got through the 200-mesh filter screen and centrifugated at 50 × g for 5 min to remove hepatocytes. The supernatant cells were collected by centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min and then the red blood cells were cracked with red cell lysis buffer. Finally, hepatic non-parenchymal cells were obtained by centrifugation at 400 × g for 5 min at 4 °C.

The cells were subsequently stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for flow cytometry analysis. The hepatic non-parenchymal cells were stained with 100 μL of surface antibody cocktail (anti-mouse F4/80-FITC, CD11c-PE and CD206-APC) for 30 min at 4 °C to analyze macrophage polarization.

For intracellular staining of 17β-HSD7, the cells were stained with surface antibodies (anti-mouse F4/80-FITC) for 30 min at 4 °C. After fixation and permeabilization for 30 min at RT, the cells were blocked for 1 h at RT with PBS containing 5% BSA. Then the cells were incubated with anti-mouse 17β-HSD7 antibody for 1.5 h and goat anti-mouse IgG/PE antibody for 1.5 h at RT.

For the detection of free cholesterol in macrophages, the cells were stained with surface antibodies (anti-mouse F4/80-FITC) for 30 min at 4 °C. After fixation and permeabilization for 30 min at RT, the cells were stained with Filipin III for 30 min at RT to analyze free cholesterol content in the macrophages. Data were acquired with a flow cytometer (BD FACS Aria III, BD) using FASC Diva software. All analysis was performed using FlowJo software (v10.0.7).

2.9. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and data analysis

scRNA-seq was done on hepatic non-parenchymal cells isolated from WT and cKO mice fed with HFD for 6 weeks by Novogene (Beijing, China). Hepatic non-parenchymal cells were prepared as described in 2.8 and subjected to scRNA-seq analysis using 10× Genomics Chromium Single-Cell 3′ according to the manufacturer's instructions. Alignment, aggregation and analysis of single-cell data sets were performed in RStudio (v1.4.1717).

2.10. Cell culture

Murine macrophage RAW 264.7, HEK293T cells and L929 cells were cultured in DMEM (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Murine hepatocytes AML-12 were cultured in DMEM/F12 (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS, ITS (5 μg/mL of insulin, 5 μg/mL of transferrin and 5 ng/mL of selenium) and 40 ng/mL dexamethasone. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with 100 ng/mL LPS + 250 μmol/L OA + 125 μmol/L PA (LOP) for 12 h in vitro, which are the main stimulating factors of hepatic macrophages in NAFLD.

Bone marrow cells were isolated from the femur and tibia of cKO mice and WT mice. The marrow from bones was flushed using PBS. Bone marrow cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 20% L929 supernatant to differentiate them into bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs). On Day 7, all adherent cells became mature macrophages.

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from WT mice. In situ liver perfusion was performed with ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) buffer followed by collagenase IV digestion. After digestion, the liver cell suspension was then centrifugated at 50 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Cell viability was confirmed by trypan blue exclusion.

For co-culture study, the BMDMs (from cKO or WT mice) or RAW 264.7 (shControl or shHsd17b7) were treated with LOP for 12 h, then cultured for 24 h after changing the medium without LOP. The supernatants were then collected and added into hepatocytes from WT mice or AML-12 to build a co-cultured system. Finally, hepatocytes were treated with OA and stained with Oil Red O to observe the lipid accumulation, and stained lipids were extracted and quantified by measuring absorbance at 570 nm. TG content was then detected in hepatocytes for quantitative analysis.

2.11. Lentivirus transfection

The Hsd17b7 interference plasmid Lv-shRNA-EGP/Hsd17b7 and negative control plasmid Lv-shRNA-EGP/NMC were purchased from Longqian Biotech (Shanghai, China). To generate Hsd17b7 knockdown RAW 264.7 cells, lentivirus vector was transfected into HEK293T cells with helper plasmids and a transfection reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California, USA). Lentivirus supernatant was harvested 24 and 52 h after transfection and cleared by a 0.45 μm filter, which was then used to infect RAW 264.7 cells. Stable cell pools were selected with puromycin for 1 week. The shRNA sequences used in this study are listed in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.12. RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using RNAiso Plus reagent, and 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA using a reverse transcriptase kit (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The expressions of indicated genes were estimated by a real-time PCR system (CXF96, Bio-Rad, USA) using SYBR Green with Gapdh as an internal gene, and the genes were analyzed using the ΔΔCT. The primer sequences used in this study are listed in Supporting Information Table S1.

2.13. Western blot

Cells were collected and lysed using lysis buffer and quantified by BCA assay. The protein lysates were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and subsequently electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at RT. The blocked membrane was incubated with primary antibody 17β-HSD7 (1:1000), and β-tubulin (1:10,000) was used as the loading control overnight, followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000) at room temperature for 1 h. Protein bands were visualized by a gel imaging analyzer (Peiqing, Shanghai, China).

2.14. Enzyme purification and activity assay of 17β-HSD7

pET-21b modified plasmid coding for mouse Hsd17b7 with 6 × His tag on C-terminal was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21. Transformed E. coli cells were first incubated in Luria–Bertani (LB) liquid medium for 3 h supplemented with ampicillin (0.1 mg/mL) at 150 rpm, 37 °C using an incubator shaker (Jinchengguosheng, Jintan, China). To express 17β-HSD7-His, IPTG (0.2 mmol/L) was added to cell suspension when OD600 = 0.6. After 5 h of incubation, cells were harvested at 4000 × g for 20 min; the resulted pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer, and then disrupted on ice with a sonicator for 30 min. The cell debris was separated from the supernatant by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 30 min) and the resulted supernatant was further loaded on a nickel-nitrilotriacetic (Ni-NTA) agarose column for the purification of 17β-HSD7 protein. Protein was eluted in different gradient concentrations of elution buffer (50, 100, 150, and 250 mmol/L imidazole), and the purified protein was stored at −20 °C until use.

The 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase activity reactions were performed in 96-well plate, containing 0.12 mmol/L estrone, 1.8 mg/mL 17β-HSD7 protein, 0.4 mmol/L NADPH and PBS (pH = 7.5). The tested drugs were incubated into plate, and DMSO or water were incubated as control. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, the enzyme activity of 17β-HSD7 was measured by the change of absorbance at 340 nm of NADPH with a microplate reader (BioTek, USA).

2.15. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between two groups were compared using a t-test, and differences among multiple groups were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's test. P < 0.05 is considered as statistical significance. Data were analyzed using SPSS 17 (SPSS Science) and Prism 7.0 (GraphPad Software).

3. Results

3.1. Hepatic macrophage 17β-HSD7 expression is significantly increased concomitantly with M1 polarization in HFD-fed mice

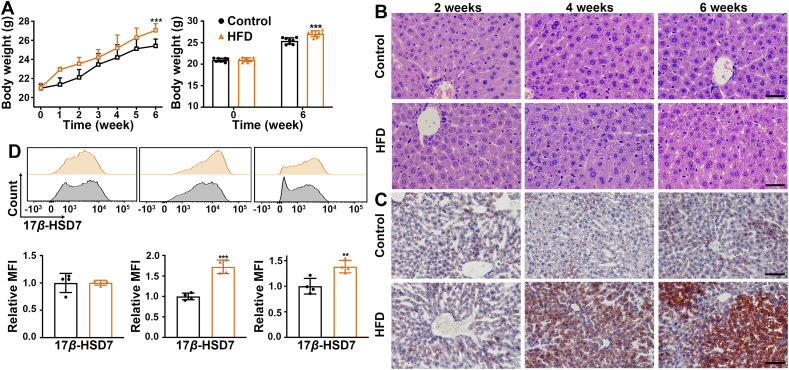

To address the relevance of macrophage 17β-HSD7 and NAFLD, the mice were fed with HFD for 2, 4 and 6 weeks gradually developing into NAFLD. The body weight of the HFD mice was higher than that of the control group (Fig. 1A). In terms of H&E staining, the hepatocytes in the control group were arranged closely and regularly, while the hepatocytes were swollen and irregular in HFD mice fed for 4 and 6 weeks (Fig. 1B). We also detected the lipid contents in the liver by Oil Red O staining and the results showed that compared with the control group, there were excessive lipid droplets in hepatocytes of HFD mice fed for 4 and 6 weeks (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, we examined the expression of 17β-HSD7 in hepatic macrophages, which was significantly higher in HFD mice than that of the control group when fed for 4 and 6 weeks, as determined by flow cytometry (Fig. 1D). Similarly, we found increased macrophage 17β-HSD7 expression in NAFLD mice induced by MCD (Supporting Information Fig. S2). In vitro, after LOP (100 ng/mL LPS + 250 μmol/L OA + 125 μmol/L PA) treatment for 6, 12 and 24 h, RAW 264.7 also showed increased mRNA and protein expressions of 17β-HSD7 (Supporting Information Fig. S3).

Figure 1.

Hepatic macrophage 17β-HSD7 upregulation was associated with NAFLD. (A) The body weight of mice in the control or HFD groups (n = 8). (B) Representative H&E staining of liver sections of control and HFD mice fed for 2, 4 and 6 weeks (scale bar: 50 μm). (C) Representative Oil Red O staining of liver sections of control and HFD mice fed for 2, 4 and 6 weeks (scale bar: 100 μm). (D) 17β-HSD7 expression was examined in hepatic macrophages of control and HFD mice fed for 2, 4 and 6 weeks by flow cytometry (n = 4). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; HFD, high-fat diet.

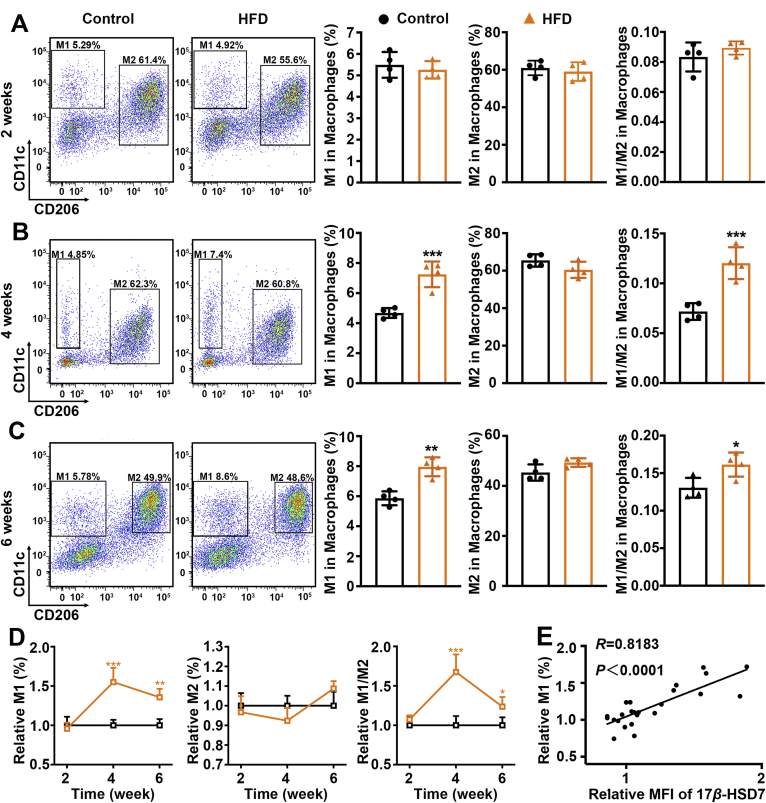

We then analyzed total macrophages (F4/80+), pro-inflammatory M1 (F4/80+CD11c+) and anti-inflammatory M2 (F4/80+CD206+) macrophages by flow cytometry. Compared with the control group, mice fed with HFD showed increased total macrophages and M1 macrophages after diet-induced 4 and 6 weeks, but the proportion of M2 showed no significant change (Fig. 2A–D, Supporting Information Fig. S4). Moreover, we observed that macrophage 17β-HSD7 expression was positively correlated with the proportion of M1 (R = 0.8183, P < 0.0001; Fig. 2E). Similar results were observed in MCD-induced NAFLD mice (Supporting Information Fig. S5). Collectively, these results suggest a positive correlation between 17β-HSD7 expression and hepatic macrophage M1 polarization during NAFLD development.

Figure 2.

Hepatic macrophage M1 polarization was positively correlated with the expression of 17β-HSD7 during NAFLD development. (A–C) Proportion of M1 (F4/80+CD11c+) and M2 (F4/80+CD206+) macrophages in the liver tissues of control and HFD mice fed for 2, 4 and 6 weeks (n = 4). (D) Dynamic changes of M1, M2 and M1/M2 in the liver tissues of control and HFD mice fed for 2, 4 and 6 weeks (n = 4). (E) The relationship between macrophage 17β-HSD7 expression and proportion of M1 (n = 24). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; HFD, high-fat diet; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

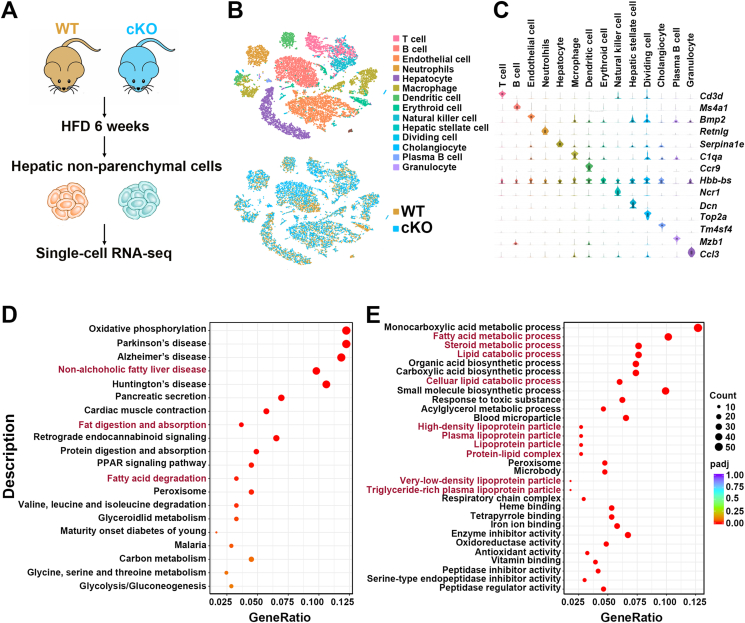

3.2. Changes in the biological processes of hepatic cells from macrophages 17β-HSD7-depletion mice

As the functions of 17β-HSD7 have not been reported in macrophages and livers, we generated macrophage-specific Hsd17b7 knockout mice (cKO) to explore the possible biological processes it affected in the liver. Successful deletion of 17β-HSD7 was confirmed by PCR using tail tissues and Western blot using bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) (Supporting Information Fig. S6). We then performed single-cell RNA sequencing on hepatic non-parenchymal cells isolated from WT and cKO mice fed with HFD for 6 weeks (Fig. 3A). T-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) visualization of combined cKO and WT data revealed 14 major cell types, which correspond to T cells, B cells, endothelial cells, neutrophils, hepatocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, erythroid cells, natural killer cells, hepatic stellate cells, dividing cells, cholangiocytes, plasma B cells and granulocytes, based on marker gene expression (Fig. 3B and C). Cellular process of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis in macrophages revealed that 17β-HSD7 mainly affected ‘NAFLD’, ‘fat digestion and absorption’ and ‘fatty acid degradation’ (Fig. 3D). Gene Ontology (GO) terms for differentially expressed genes in hepatocytes revealed that the biological functions of 17β-HSD7 associated with ‘lipid metabolism processes’ were notably changed (Fig. 3E). These results indicate a possible role of macrophage 17β-HSD7 in lipid metabolism and NAFLD.

Figure 3.

Biological processes in the livers from WT and cKO mice fed with HFD. (A) Overview of the single-cell RNA-seq. (B) t-SNE visualization of hepatic cell types. (C) Violin plots show representative marker gene expression for each cell type. (D) Bubble plots show significantly changed KEGG pathways in macrophages. (E) Bubble plots show significantly changed GO analysis in hepatocytes. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; GO, gene ontology; HFD, high-fat diet; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; t-SNE, T-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding.

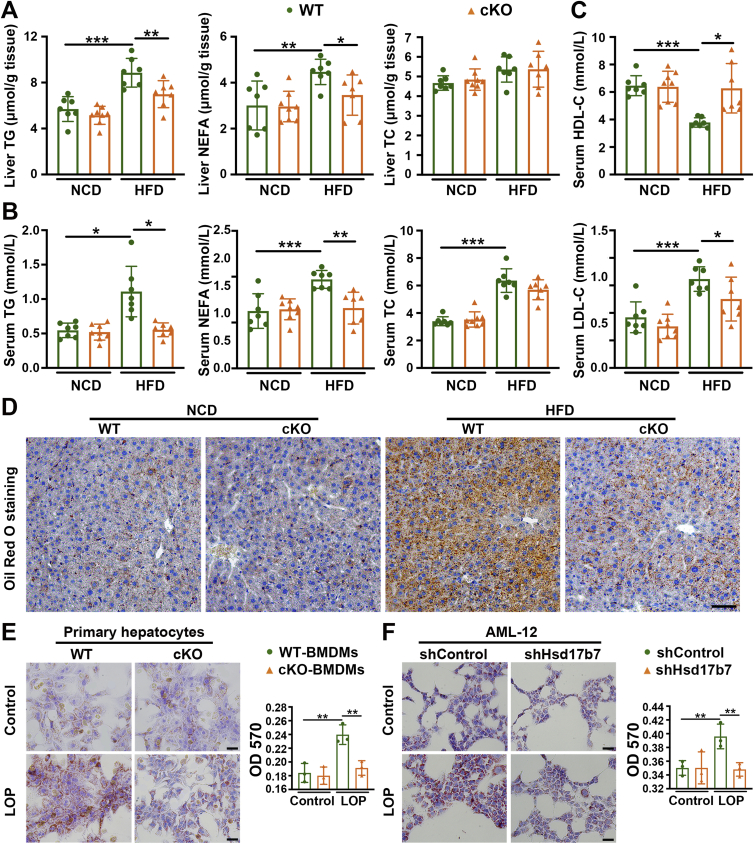

3.3. Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages reduces hepatic lipid accumulation

Furthermore, hepatic TC, TG and NEFA levels were measured to reflect hepatic lipid accumulations. As shown in Fig. 4, compared with WT mice fed with HFD, hepatic TG and NEFA levels were significantly decreased in cKO mice fed with the same diet, and hepatic TC showed no differences (Fig. 4A). Consistently, the serum TG and NEFA levels of cKO mice were less than that of WT mice (Fig. 4B). In addition, serum HDL-C levels were increased and LDL-C levels were decreased in cKO mice compared with WT mice fed with HFD (Fig. 4C). Oil Red O staining of liver sections also showed that cKO mice had less steatosis compared with WT mice (Fig. 4D). Meanwhile, we co-cultured primary mouse hepatocytes with LOP (LPS + OA + PA)-stimulated BMDMs from cKO or WT mice. Hepatocytes co-cultured with cKO BMDMs accumulated less lipid droplets than with WT BMDMs as determined by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 4E). Similarly, murine hepatocyte AML-12 co-cultured with shHsd17b7 RAW 264.7 also exhibited less lipid accumulation than with shControl after LOP treatment (Fig. 4F).

Figure 4.

Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages reduced hepatic lipid accumulation. (A) Liver TG, NEFA and TC levels in WT and cKO mice fed with HFD or NCD (n = 7–8). (B) Serum TG, NEFA, TC levels, and (C) LDL-C and HDL-C levels in WT and cKO mice fed with HFD or NCD (n = 7–8). (D) Representative pictures of Oil Red O staining of liver sections (scale bar: 100 μm). (E) Representative pictures of Oil Red O staining of primary hepatocytes co-cultured with BMDMs from WT and cKO mice treated with LOP (left panel, scale bar: 100 μm), and quantitative analysis at OD 570 nm (right panel, n = 3). (F) Representative pictures of Oil Red O staining of AML-12 co-cultured with shControl and shHsd17b7 treated with LOP (left panel, scale bar: 100 μm), and quantitative analysis at OD 570 nm (right panel, n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; NEFa, free fatty acid; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HFD, high-fat diet; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LOP, 100 ng/mL LPS + 250 μmol/L OA + 125 μmol/L PA; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; NCD, normal chow diet; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acid; OA, oleic acid; PA, palmitic acid; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

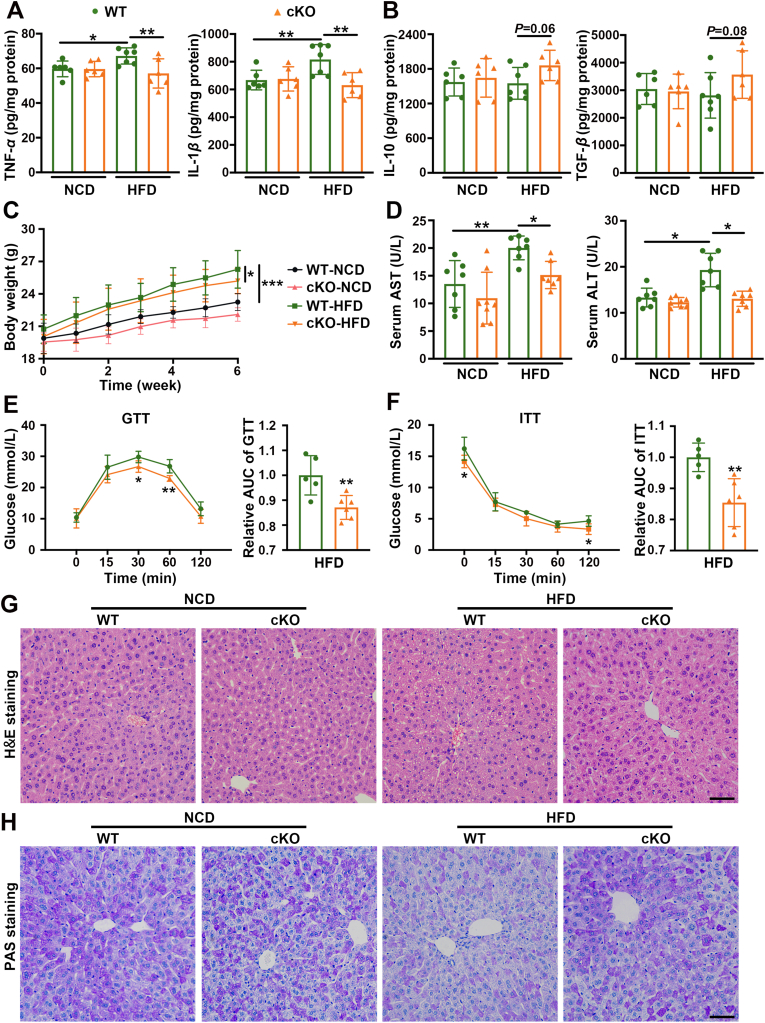

3.4. Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages ameliorates insulin resistance, hepatic injury and hepatic histopathology in NAFLD mice

The effects of macrophage 17β-HSD7 on hepatic lipid accumulation prompted us to focus on cytokine changes which are closely related to insulin resistance and liver damage. We tested the pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β) and the anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β). The results showed a significant reduction of TNF-α and IL-1β in the livers of cKO mice compared with that of the WT mice fed with HFD (Fig. 5A). However, the anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β of cKO mice were just slightly increased compared with those in WT mice (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, compared with the WT mice fed with NCD, the body weight of WT mice fed with HFD gained faster, while it was lower in cKO mice under HFD feeding (Fig. 5C). HFD-induced hepatic injury, as indicated by elevated serum AST and ALT activities, was attenuated in cKO mice (Fig. 5D). Notably, HFD-fed cKO mice showed decreased glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity compared with HFD-fed WT mice, as determined by GTT and ITT (Fig. 5E and F). Histological examination of liver sections showed that cKO mice had much improved histology with WT mice, as demonstrated by H&E staining (Fig. 5G). PAS staining showed that cKO mice had higher glycogen content in the livers than WT mice fed with same HFD (Fig. 5H). Collectively, these data indicate that macrophage 17β-HSD7 promotes the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, inducing NAFLD.

Figure 5.

Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages ameliorated insulin resistance, hepatic injury and hepatic histopathology in NAFLD mice. Levels of (A) TNF-α and IL-1β, (B) IL-10 and TGF-β in the livers of WT and cKO mice fed with HFD or NCD (n = 6–7). (C) The body weight, (D) serum ALT and AST in WT and cKO mice fed with HFD (n = 7–8). (E) GTT and (F) ITT in WT and cKO mice fed with HFD (n = 5–6). (G) Representative pictures of H&E staining of liver sections (scale bar: 100 μm). (H) Representative pictures of PAS staining of liver sections (scale bar: 100 μm). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; GTT, glucose tolerance test; H&E, hematoxylin AUC, area under curve; and eosin; HFD, high-fat diet; IL-1β, interleukins-1β; IL-10, interleukins-10; ITT, insulin tolerance test; NCD, normal chow diet; PAS, periodic acid-Schiff; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

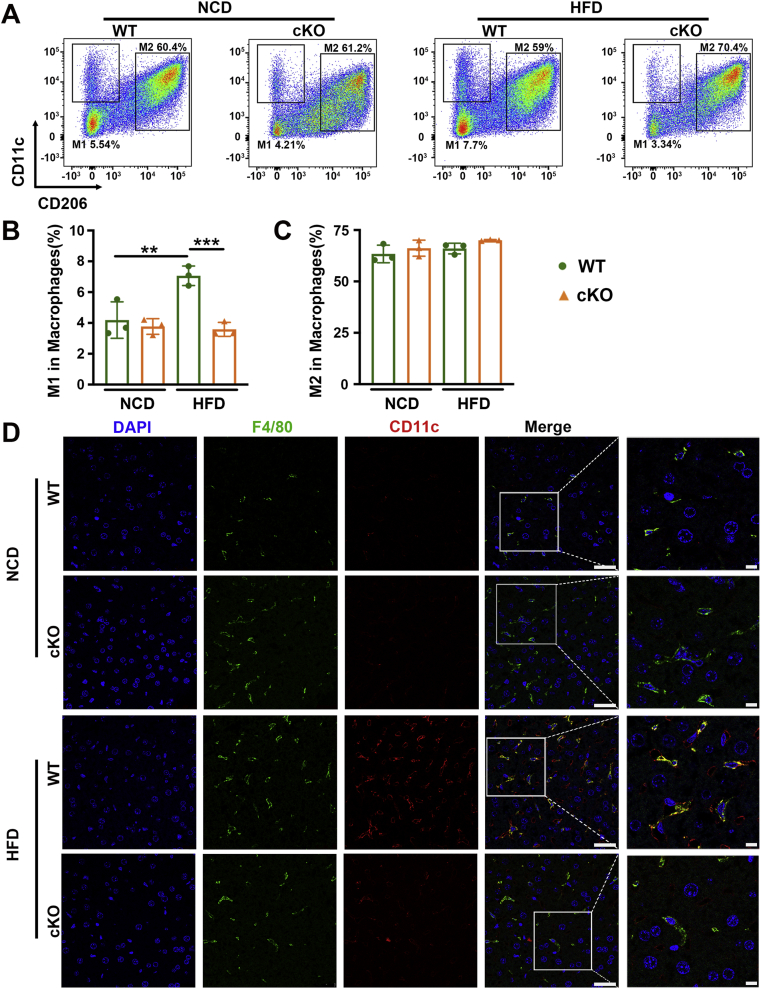

3.5. Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages reduces macrophage M1 polarization

We subsequently attempted to identify whether 17β-HSD7 participated in NAFLD through regulating macrophage M1 polarization. We analyzed M1 (F4/80+CD11c+) and M2 macrophages from the liver tissues of WT and NCD mice fed with HFD by flow cytometry. Compared with WT mice, cKO mice showed decreased proportions of M1 macrophages, but M2 proportions had no changes (Fig. 6A–C). Moreover, IF staining of liver sections revealed that the fluorescence intensity of CD11c in the liver sections also showed increased M1 macrophages in HFD mice, which was attenuated in cKO mice (Fig. 6D). Moreover, the total frequency of F4/80+ macrophages in the liver was obviously decreased in cKO mice compared with WT mice (Supporting Information Fig. S7). These results suggest that 17β-HSD7 can promote macrophage polarization to M1 phenotype.

Figure 6.

Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages reduced M1 polarization. (A) Proportions of M1 (F4/80+CD11c+) and M2 (F4/80+CD206+) macrophages in the liver tissues of WT and cKO mice fed with HFD or NCD. (B) The statistical analysis of proportions of M1 macrophages (n = 3). (C) The statistical analysis of proportions of M2 macrophages (n = 3). (D) Representative pictures of IF staining for CD11c and F4/80 in the liver tissues of WT and cKO mice fed with HFD (scale bar: 25 μm). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; HFD, high-fat diet; IF, immunofluorescence; NCD, normal chow diet.

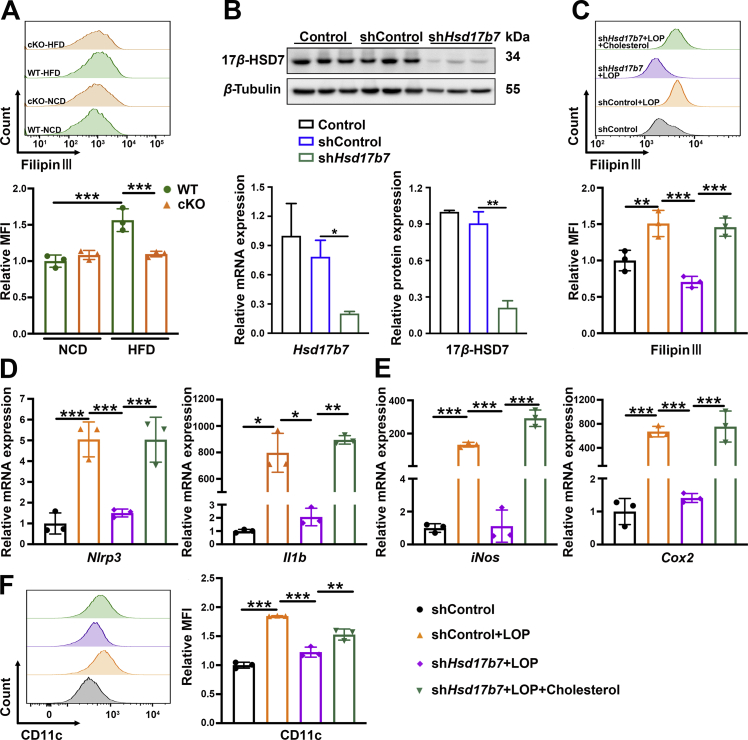

3.6. Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages decreases free cholesterol content

To gain mechanistic insights for 17β-HSD7 regulation of macrophage polarization, we detected the free cholesterol (FC) content (F4/80+ Filipin III+) in macrophages by flow cytometry. The results show that FC content in hepatic macrophages of HFD mice was greater than that of NCD, which was attenuated in cKO mice (Fig. 7A). Studies have shown that the accumulation of FC results in the formation of cholesterol crystals23,24, which can induce NLRP3 inflammasome activation and subsequent pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β secretion25,26. To clarify whether 17β-HSD7 could induce macrophage polarization through FC, we constructed Hsd17b7 knockdown RAW 264.7 by shRNA. Successful knockdown of 17β-HSD7 was confirmed by qRT-PCR and Western blot (Fig. 7B). Compared with shControl treated with LOP, FC content and the mRNA expression of Nlrp3 and Il1b were markedly decreased in shHsd17b7 RAW 264.7 treated with LOP, whereas they were significantly increased after exogenous cholesterol recruitment (Fig. 7C and D). Furthermore, we analyzed pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages in shControl and shHsd17b7 of RAW 264.7 cells with LOP treatment. Compared with shControl, shHsd17b7 RAW 264.7 showed a decreased proportion of M1 and mRNA expression of M1 markers (iNos and Cox2). Subsequently, after exogenous cholesterol treatment, shHsd17b7 RAW 264.7 significantly polarized to M1 phenotype (Fig. 7E and F). Overall, these findings suggest that increased FC content mediates the 17β-HSD7-induced macrophage M1 polarization.

Figure 7.

Exogenous cholesterol recruitment reversed the decreased M1 polarization in 17β-HSD7 knockdown RAW 264.7. (A) MFI of Filipin Ⅲ in macrophages in the liver tissues of WT and cKO mice fed with HFD (n = 3). (B) 17β-HSD7 knockdown in RAW 264.7 was verified by qRT-PCR (left panel) and Western blot (right panel). (C) MFI of Filipin Ⅲ in RAW 264.7 was examined by flow cytometry (n = 3). mRNA expressions of (D) Nlrp3 and Il1b, (E) iNos and Cox2 were examined by qRT-PCR (n = 3). (F) MFI of CD11c in RAW 264.7 was examined by flow cytometry (n = 3). Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; Cox2, cyclooxygenase-2; Il1b, interleukins-1β; iNos, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; Nlrp3, NLR family pyrin domain containing 3.

3.7. Fenretinide is screened out as a 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase inhibitor and may improve hepatocyte steatosis

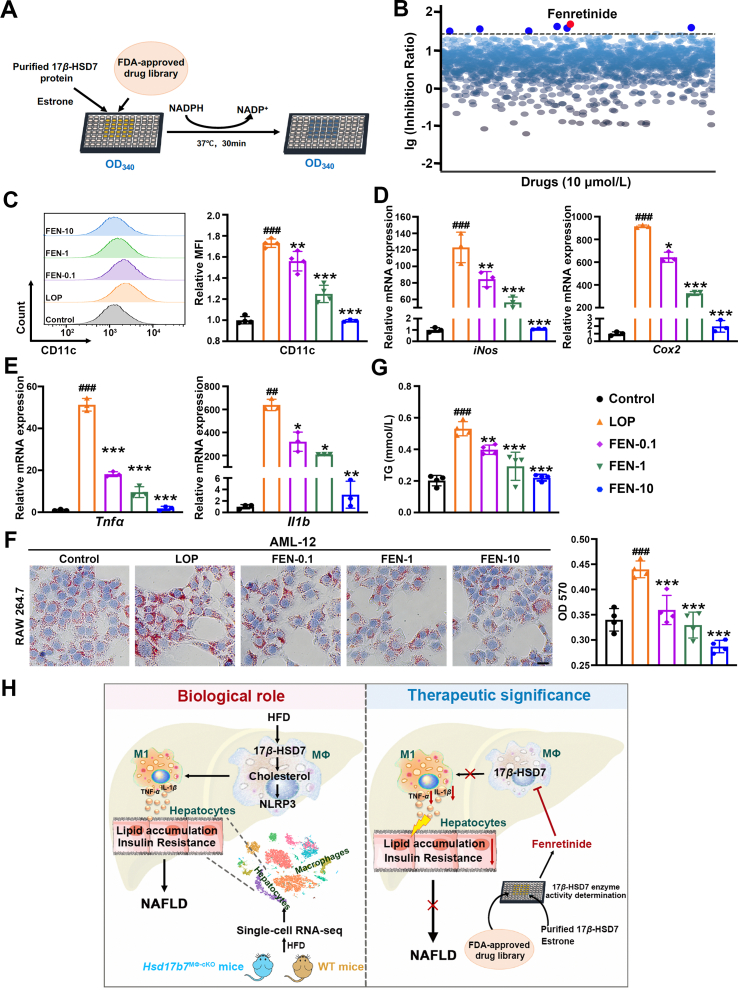

Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages can ameliorate NAFLD, suggesting that 17β-HSD7 may be a potential new target for treating NAFLD. Thus, an FDA-approved drug library was screened to identify drugs targeting 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase activity (Fig. 8A). Seven drugs (fenretinide, bilastine, hydralazine HCl, l-lactic acid, deferasirox, verapamil HCl, clofarabine) were screened out showing inhibitory effects on 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase activity at more than a 30% inhibition ratio, among which fenretinide exhibited a remarkable inhibitory effect (Fig. 8B).

Figure 8.

The 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase inhibitor, fenretinide, reduced macrophage M1 polarization and hepatocytes lipid accumulation. (A) Schematic outline of screening 17β-HSD7 inhibitor. (B) The inhibition ratio on 17β-HSD7 of drugs. (C) MFI of CD11c in RAW 264.7 was examined by flow cytometry (n = 3). mRNA expressions of (D) iNos and Cox2, (E) Tnfa and Il1b were examined by qRT-PCR (n = 3). (F) Representative pictures of Oil Red O staining of AML-12 co-cultured with fenretinide treated-RAW 264.7 (left panel, scale bar: 50 μm) and quantitative analysis at OD 570 nm (right panel, n = 4). (G) TG content in AML-12 when co-cultured with fenretinide treated-RAW 264.7 (n = 4). (H) Schematic represents the regulation of 17β-HSD7 and fenretinide on macrophage M1 polarization and NAFLD pathogenesis. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. the control; ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. LOP. 17β-HSD7, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7; FEN, fenretinide; Cox2, cyclooxygenase-2; Il1b, interleukins-1β; iNos, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LOP, 100 ng/mL LPS+ 250 μmol/L OA+ 125 μmol/L PA; LPS, lipopolysaccharides; OA, oleic acid; PA, palmitic acid; Tnfa, tumor necrosis factor-α; TG, triglyceride.

To assess the potential therapeutic effect of 17β-HSD7 inhibitor on NAFLD, fenretinide was added to RAW 264.7 under LOP treatment. MTT results show that 0.1–1 μmol/L fenretinide treatment had no significant effect on the viability of RAW 264.7 cells (Supporting Information Fig. S8). Flow cytometry analysis results show that the M1 polarization was decreased after fenretinide (0.1, 1, 10 μmol/L) treatment, as compared with LOP group (Fig. 8C). Besides, we observed that fenretinide treatment reduced the mRNA expressions of M1 markers (iNos and Cox2) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Tnfa and Il1b) in RAW 264.7 when compared with that of LOP group (Fig. 8D and E). Further we measured the hepatocyte lipid contents in AML-12 co-cultured with fenretinide-treated RAW 264.7, and observed that lipid droplets and levels of TG in hepatocytes were significantly decreased after fenretinide treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8F and G). In addition, another drug, hydralazine HCl, was also used to assess the effect of 17β-HSD7 inhibitor on hepatocytes steatosis. Flow cytometry and mRNA results showed hydralazine HCl had similar effects to fenretinide on inhibiting M1 polarization and hepatocytes fat deposition through macrophages (Supporting Information Fig. S9). These findings provide important evidence for the utilization of 17β-HSD7 inhibitor as an improvement agent for NAFLD.

4. Discussion

Hepatic macrophage M1 polarization is a pivotal factor in the onset and progression of NAFLD, which promotes both hepatocyte steatosis and inflammation27. Previous studies have demonstrated that macrophage M1 polarization was highly increased in patients with NAFLD and HFD-induced NAFLD mice28, 29, 30. Moreover, another evidence has suggested that pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted by M1 macrophages mediate lipogenesis in hepatocytes and aggravate hepatic steatosis31. For example, TNF-α was found to upregulate the expression of lipogenic enzymes like FASN, which could suppress fatty acid oxidation32, 33, 34. When the liver develops overt fat deposition and inflammatory damage, NAFL progresses to NASH. Thus, molecules associated with M1 polarization are prospective mediators in driving the progression of NAFL to NASH. Moreover, the upregulation of cholesterol synthesis pathways in macrophages of NAFLD mice indicates the potential role of cholesterol synthesis-related molecules in M1 polarization. A study has shown that macrophage-specific knockout of HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme of cholesterol biosynthesis, can improve the adipose tissue M1 polarization. However, it has no effects on hepatic M1 polarization35. It prompted us to explore other cholesterol synthesis-related molecules regulating hepatic macrophage. In this study, we built mouse models without hepatic steatosis (fed with HFD for 2 weeks) and with significantly hepatic steatosis (fed with HFD or MCD for 4 and 6 weeks) to observe the role of hepatic macrophage polarization in NAFLD and analyzed the expression of 17β-HSD7 for exploring the underlying mechanism of M1 polarization. We first found that macrophage 17β-HSD7 expression was significantly increased after HFD or MCD feeding for 4 and 6 weeks, concomitantly with elevated M1 polarization. These indicated that 17β-HSD7 might be correlated with M1 polarization and hepatic lipid accumulation in HFD-fed mice.

At present, researches of Hsd17b7 are mainly focused on its role in promoting breast cancer and other estrogen-related diseases through regulating estrogen homeostasis36,37, while research on liver-related diseases is rarely reported. Intriguingly, 17β-HSD7 is highly expressed in the liver19,20, and the human HSD17B7 gene maps to chromosome 10p11.2, which is close to the susceptibility loci for metabolic diseases such as hyperlipidemia, obesity and type I diabetes38, indicating it might participate in NAFLD. Moreover, because the synchronicity of increased 17β-HSD7 and macrophage polarization was observed in HFD-induced NAFLD mice in our study, we generated macrophage-specific Hsd17b7 knockout mice (cKO) to detect its role in macrophage polarization and NAFLD. We first investigated the role of 17β-HSD7 in M1 polarization. The results show that HFD-induced NAFLD mice showed increased M1 polarization and the secretions of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, which were inhibited by the deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages, suggesting that 17β-HSD7 participates in hepatic M1 polarization. We next investigated the role of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages under NAFLD development. Deletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages changed ‘lipid metabolism processes’ in hepatocytes and showed a significant correlation with NAFLD according to single-cell RNA sequencing results. Specifically, patients with NAFLD often show increased body weight gain, lipid metabolism disorders and liver damage. In this study, depletion of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages could alleviate the body weight gain, IR and the accumulation of hepatic and blood lipids in HFD mice. In summary, macrophage 17β-HSD7 participates in NAFLD by promoting M1 polarization.

Several studies have shown that cholesterol content in macrophages is closely associated with the polarization state of macrophages in metabolic diseases39, 40, 41. It has been reported that macrophage cholesterol content and M1 polarization were increased in the liver of NAFLD mice, and the increased intracellular cholesterol content could promote M1 polarization9,24,42. Specifically, the accumulation of cholesterol in macrophages triggers M1 polarization mediated by NLRP3 inflammasome activation42,43. An in vitro study found that after exogenous cholesterol treatment, mouse macrophages RAW 264.7 polarized towards M1 phenotype, and the intracellular cholesterol content is positively related to the proportion of M144. In this study, the expression of 17β-HSD7 and FC content in hepatic macrophages were increased in NAFLD mice, which might be the cause of the elevated M1 polarization. By contrast, inhibition of 17β-HSD7 in macrophages showed decreased FC content, NLRP3 expression and M1 polarization. Furthermore, exogenous cholesterol recruitment could reverse the improvement effects from 17β-HSD7 inhibition, leading to increased NLRP3 expression and M1 polarization. These results indicate that macrophage 17β-HSD7 facilitates M1 polarization by increasing FC content, promoting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and subsequently pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion. In addition, our single-cell RNA sequencing results show that 17β-HSD7 had wide effect on amino acid, glucose and energy metabolism, among which oxidative phosphorylation were remarkably changed in macrophages in cKO mice fed with HFD. Moreover, researches have shown that the metabolism of macrophage polarization was greatly dependent on oxidative phosphorylation for energy generation29,45. Collectively, the role of 17β-HSD7 on oxidative phosphorylation process may be another prospective mechanism on macrophage polarization and NAFLD progression.

Currently, there are no approved pharmacological treatments for NAFLD. As the polarization of hepatic macrophages is a key event for the onset and progression of NAFLD, several studies have attempted to explore drugs improving M1 polarization for NAFLD treatment, some of which have shown efficacy on NAFLD8,46,47. In this study, we screened out 7 drugs from an FDA-approved drug library based on their inhibitory effect on 17β-HSD7 dehydrogenase activity, among which fenretinide showed the most significantly inhibitory effect. Fenretinide (N-4-hydroxyphenyl retinamide [4-HPR]), a cancer chemopreventive and antiproliferative agent, is a synthetic retinoid. It is endowed with many pharmacological features, including anti-inflammatory, antiviral and antitumor activities on a wide range of tumors48, 49, 50. Preitner's study has shown that 16 weeks of fenretinide treatment ameliorated obesity, insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis on HFD-fed mice51. In addition, Koh's study has showed fenretinide could prevent fatty liver by increasing plasma adiponectin levels, activation of hepatic AMPK and the expression of PPARα and AOX, which promote fatty acid oxidation52. In this study, we found macrophage 17β-HSD7 as a novel target molecule and M1 polarization as a novel mechanism for fenretinide on NAFLD. Fenretinide dose-dependently (0.1, 1, 10 μmol/L) improved abnormal M1 polarization and pro-inflammatory cytokines production in LOP-treated RAW 264.7. Further, the co-culture system of macrophages and hepatocytes was built to analyze the effect of fenretinide treated-macrophages on hepatocytes. Hepatocytes AML-12 co-cultured with fenretinide-treated RAW 264.7 showed less lipid accumulation than that without fenretinide. In addition, another screened-out drug, Hydralazine HCl, also showed an inhibitory effect on M1 polarization and pro-inflammatory production, which further resulted in less hepatocytes lipid accumulation. Collectively, these suggest macrophages 17β-HSD7 may represent a potential target for NAFLD therapy, and fenretinide may be a therapeutic candidate for NAFLD by inhibiting macrophage 17β-HSD7.

5. Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated that 17β-HSD7-induced macrophage M1 polarization critically contributes to NAFLD progression by regulating free cholesterol content in macrophages. Furthermore, the improvement of fenretinide on M1 polarization and in turn hepatocytes lipid accumulation relied on inhibiting 17β-HSD7. Overall, our study provides 17β-HSD7 as a novel regulator of macrophage polarization and potential target of fenretinide on NAFLD therapy, indicating that blockade of 17β-HSD7 signaling by fenretinide would be a drug repurposing strategy for NAFLD treatment. However, further studies are warranted to explore the other possible mechanisms of 17β-HSD7 on macrophage polarization and NAFLD, e.g., oxidative phosphorylation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82173872 and 81872663).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2022.04.003.

Author contributions

Xiaoyu Dong and Yiting Feng designed the experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. Yiting Feng, Xiaoyu Dong, Dongqin Xu, Mengya Zhang contributed to experiments and corrected the manuscript. Xiao Wen, Wenhao Zhao, Qintong Hu, Qinyong Zhang and Hui Fu helped data collection. Jie Ping supervised research and critically reviewed the paper.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Cotter T.G., Rinella M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 2020: the state of the disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1851–1864. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang D.Q., El-Serag H.B., Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore M.P., Cunningham R.P., Dashek R.J., Mucinski J.M., Rector R.S. A fad too far? Dietary strategies for the prevention and treatment of NAFLD. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1843–1852. doi: 10.1002/oby.22964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tilg H., Moschen A.R. Evolution of inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: the multiple parallel hits hypothesis. Hepatology. 2010;52:1836–1846. doi: 10.1002/hep.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Racanelli V., Rehermann B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology. 2006;43:S54–S62. doi: 10.1002/hep.21060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazankov K., Jørgensen S.M.D., Thomsen K.L., Møller H.J., Vilstrup H., George J., et al. The role of macrophages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:145–159. doi: 10.1038/s41575-018-0082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baffy G. Kupffer cells in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the emerging view. J Hepatol. 2009;51:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wan J., Benkdane M., Teixeira-Clerc F., Bonnafous S., Louvet A., Lafdil F., et al. M2 kupffer cells promote M1 kupffer cell apoptosis: a protective mechanism against alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2014;59:130–142. doi: 10.1002/hep.26607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klöting N., Blüher M. Adipocyte dysfunction, inflammation and metabolic syndrome. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s11154-014-9301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narayanan S., Surette F.A., Hahn Y.S. The immune landscape in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Immune Netw. 2016;16:147–158. doi: 10.4110/in.2016.16.3.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C., Rajapakse A.G., Riedo E., Fellay B., Bernhard M.C., Montani J.P., et al. Targeting arginase-II protects mice from high-fat-diet-induced hepatic steatosis through suppression of macrophage inflammation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20405. doi: 10.1038/srep20405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han Y.H., Kim H.J., Na H., Nam M.W., Kim J.Y., Kim J.S., et al. RORα induces KLF4-mediated M2 polarization in the liver macrophages that protect against nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Rep. 2017;20:124–135. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen E., Aviram M., Khatib S., Rosenblat M., Vaya J. Human carotid atherosclerotic lesion protein components decrease cholesterol biosynthesis rate in macrophages through 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase regulation. Biofactors. 2015;41:28–34. doi: 10.1002/biof.1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaplan M., Kerry R., Aviram M., Hayek T. High glucose concentration increases macrophage cholesterol biosynthesis in diabetes through activation of the sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1): inhibitory effect of insulin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:324–332. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181879d98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraemer F.B. Insulin deficiency alters cellular cholesterol metabolism in murine macrophages. Diabetes. 1986;35:764–770. doi: 10.2337/diab.35.7.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leroux A., Ferrere G., Godie V., Cailleux F., Renoud M.L., Gaudin F., et al. Toxic lipids stored by kupffer cells correlates with their pro-inflammatory phenotype at an early stage of steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2012;57:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnesorg T., Adamski J. Promoter analyses of human and mouse 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;94:259–261. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jokela H., Rantakari P., Lamminen T., Strauss L., Ola R., Mutka A.L., et al. Hydroxysteroid (17beta) dehydrogenase 7 activity is essential for fetal de novo cholesterol synthesis and for neuroectodermal survival and cardiovascular differentiation in early mouse embryos. Endocrinology. 2010;151:1884–1892. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohnesorg T., Keller B., Hrabé de Angelis M., Adamski J. Transcriptional regulation of human and murine 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type-7 confers its participation in cholesterol biosynthesis. J Mol Endocrinol. 2006;37:185–197. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.02043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thériault J.F., Lin S.X. The dual sex hormone specificity for human reductive 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7: synergistic function in estrogen and androgen control. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;186:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2018.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tai M.M. A mathematical model for the determination of total area under glucose tolerance and other metabolic curves. Diabetes Care. 1994;17:152–154. doi: 10.2337/diacare.17.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qiu Y., Sui X., Zhan Y., Xu C., Li X., Ning Y., et al. Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) overexpression attenuates HFD-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2017;1863:978–990. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabas I. Consequences of cellular cholesterol accumulation: basic concepts and physiological implications. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:905–911. doi: 10.1172/JCI16452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ioannou G.N., Van Rooyen D.M., Savard C., Haigh W.G., Yeh M.M., Teoh N.C., et al. Cholesterol-lowering drugs cause dissolution of cholesterol crystals and disperse Kupffer cell crown-like structures during resolution of NASH. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:277–285. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M053785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duewell P., Kono H., Rayner K.J., Sirois C.M., Vladimer G., Bauernfeind F.G., et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 2010;464:1357–1361. doi: 10.1038/nature08938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajamäki K., Lappalainen J., Oörni K., Välimäki E., Matikainen S., Kovanen P.T., et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tosello-Trampont A.C., Landes S.G., Nguyen V., Novobrantseva T.I., Hahn Y.S. Kuppfer cells trigger nonalcoholic steatohepatitis development in diet-induced mouse model through tumor necrosis factor-α production. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:40161–40172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.417014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Du Y., Paglicawan L., Soomro S., Abunofal O., Baig S., Vanarsa K., et al. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate dampens non-alcoholic fatty liver by modulating liver function, lipid profile and macrophage polarization. Nutrients. 2021;13:599. doi: 10.3390/nu13020599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu F., Guo M., Huang W., Feng L., Zhu J., Luo K., et al. Annexin A5 regulates hepatic macrophage polarization via directly targeting PKM2 and ameliorates NASH. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101634. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bocsan I.C., Milaciu M.V., Pop R.M., Vesa S.C., Ciumarnean L., Matei D.M., et al. Cytokines genotype-phenotype correlation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:4297206. doi: 10.1155/2017/4297206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambertucci F., Arboatti A., Sedlmeier M.G., Motiño O., Alvarez M.L., Ceballos M.P., et al. Disruption of tumor necrosis factor alpha receptor 1 signaling accelerates NAFLD progression in mice upon a high-fat diet. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;58:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fafián-Labora J., Carpintero-Fernández P., Jordan S.J.D., Shikh-Bahaei T., Abdullah S.M., Mahenthiran M., et al. FASN activity is important for the initial stages of the induction of senescence. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:318. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beier K., Völkl A., Fahimi H.D. TNF-alpha downregulates the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-alpha and the mRNAs encoding peroxisomal proteins in rat liver. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:385–387. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00805-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beier K., Völkl A., Fahimi H.D. Suppression of peroxisomal lipid beta-oxidation enzymes of TNF-alpha. FEBS Lett. 1992;310:273–276. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81347-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takei A., Nagashima S., Takei S., Yamamuro D., Murakami A., Wakabayashi T., et al. Myeloid HMG-CoA reductase determines adipose tissue inflammation, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes. 2020;69:158–164. doi: 10.2337/db19-0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shehu A., Albarracin C., Devi Y.S., Luther K., Halperin J., Le J., et al. The stimulation of HSD17B7 expression by estradiol provides a powerful feed-forward mechanism for estradiol biosynthesis in breast cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:754–766. doi: 10.1210/me.2010-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Gérard C., Thériault J.F., Poirier D., Doillon C.J., Lin S.X. Synergistic control of sex hormones by 17β-HSD type 7: a novel target for estrogen-dependent breast cancer. J Mol Cell Biol. 2015;7:568–579. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjv028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krazeisen A., Breitling R., Imai K., Fritz S., Möller G., Adamski J. Determination of cDNA, gene structure and chromosomal localization of the novel human 17beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 7. FEBS Lett. 1999;460:373–379. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01366-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhu X., Lee J.Y., Timmins J.M., Brown J.M., Boudyguina E., Mulya A., et al. Increased cellular free cholesterol in macrophage-specific Abca1 knock-out mice enhances pro-inflammatory response of macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:22930–22941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801408200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westerterp M., Murphy A.J., Wang M., Pagler T.A., Vengrenyuk Y., Kappus M.S., et al. Deficiency of ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 and G1 in macrophages increases inflammation and accelerates atherosclerosis in mice. Circ Res. 2013;112:1456–1465. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.301086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Y., Schwabe R.F., DeVries-Seimon T., Yao P.M., Gerbod-Giannone M.C., Tall A.R., et al. Free cholesterol-loaded macrophages are an abundant source of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6: model of NF-kappaB- and map kinase-dependent inflammation in advanced atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21763–21772. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen H.W., Yen C.C., Kuo L.L., Lo C.W., Huang C.S., Chen C.C., et al. Benzyl isothiocyanate ameliorates high-fat/cholesterol/cholic acid diet-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through inhibiting cholesterol crystal-activated NLRP3 inflammasome in kupffer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020;393:114941. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2020.114941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tall A.R., Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15:104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu X., Zhang A., Li N., Li P.L., Zhang F. Concentration-dependent diversifcation effects of free cholesterol loading on macrophage viability and polarization. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:419–431. doi: 10.1159/000430365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vats D., Mukundan L., Odegaard J.I., Zhang L., Smith K.L., Morel C.R., et al. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1β attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metabol. 2006;4:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith K. Liver disease: kupffer cells regulate the progression of ALD and NAFLD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:503. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sakai Y., Chen G., Ni Y., Zhuge F., Xu L., Nagata N., et al. DPP-4 inhibition with anagliptin reduces lipotoxicity-induced insulin resistance and steatohepatitis in male mice. Endocrinology. 2020;161:baqq139. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cooper J.P., Reynolds C.P., Cho H., Kang M.H. Clinical development of fenretinide as an antineoplastic drug: pharmacology perspectives. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2017;242:1178–1184. doi: 10.1177/1535370217706952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Palo G., Mariani L., Camerini T., Marubini E., Formelli F., Pasini B., et al. Effect of fenretinide on ovarian carcinoma occurrence. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;86:24–27. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2002.6663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Puduvalli V.K., Yung W.K., Hess K.R., Kuhn J.G., Groves M.D., Levin V.A., et al. Phase II study of fenretinide (NSC 374551) in adults with recurrent malignant gliomas: a north American brain tumor consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4282–4289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Preitner F., Mody N., Graham T.E., Peroni O.D., Kahn B.B. Long-term fenretinide treatment prevents high-fat diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297:E1420–E1429. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00362.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koh I.U., Jun H.S., Choi J.S., Lim J.H., Kim W.H., Yoon J.B., et al. Fenretinide ameliorates insulin resistance and fatty liver in obese mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:369–375. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.