Summary

The patch-clamp technique is the gold-standard methodology for analysis of excitable cells. However, throughput of manual patch-clamp is slow, and high-throughput robotic patch-clamp, while helpful for applications like drug screening, has been primarily used to study channels and receptors expressed in heterologous systems. We introduce an approach for automated high-throughput patch-clamping that enhances analysis of excitable cells at the channel and cellular levels. This involves dissociating and isolating neurons from intact tissues and patch-clamping using a robotic instrument, followed by using an open-source Python script for analysis and filtration. As a proof of concept, we apply this approach to investigate the biophysical properties of voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, which are among the most diverse and complex neuronal cells. Our approach enables voltage- and current-clamp recordings in the same cell, allowing unbiased, fast, simultaneous, and head-to-head electrophysiological recordings from a wide range of freshly isolated neurons without requiring culturing on coverslips.

Keywords: dorsal root ganglion, voltage-gated sodium channel, excitability, patch-clamp, pharmacology, voltage-clamp, current-clamp, neuron, automated, high-throughput

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

High-throughput electrophysiological method to investigate freshly isolated neurons

-

•

Our method enables fast, unbiased, and head-to-head analysis of diverse neurons

-

•

Enables analysis of neurons without requiring overnight culture on glass coverslips

-

•

Enables high-throughput voltage- and current-clamp within the same neurons

Motivation

The patch-clamp technique has provided many insights into neurons and the channels and receptors that reside within them. This powerful technique offers precise measurements of the ionic conductances in neurons when used in the voltage-clamp mode, while also offering precise measurements of macroscopic cellular excitability when used in the current-clamp mode. However, traditional patch-clamp has significant drawbacks. Manual recordings are labor intensive and subject to selection bias of neurons that are recorded. We therefore developed a high-throughput and unbiased method that addresses the limitations of manual patch-clamp.

Ghovanloo et al. propose an automated, high-throughput, and completely unbiased method to investigate the electrophysiological properties of freshly isolated neurons. This method enables voltage- and current-clamp analysis within the same neurons.

Introduction

Since its introduction in the 1980s, the patch-clamp method1,2,3 has taught us innumerable lessons about neurons and the channels and receptors within them. Used in the voltage-clamp (VC) mode, it can provide accurate measurements of the ionic conductances in excitable cells. Used in the current-clamp (CC) mode it can provide measurements of macroscopic cellular excitability. Patch-clamp electrophysiology has enhanced our understanding of virtually every ion channel and receptor, and has contributed to understanding of virtually every type of neuron.4

Despite the power of patch-clamp recording, like all methods it comes with some challenges and limitations. Among these are, in its manual (physiologist-implemented) configuration, the labor-intensive and time-consuming nature of patch-clamp recording. It can take even a skilled physiologist ∼10–15 min to assess a single cell. This limitation (along with others) has been mitigated by the introduction of robotic, higher throughput methods that achieve high-resistance seals, and perform patch-clamp physiology using suction (cell-on-a-hole) methodology to record, rather than lowering an electrode onto each cell.5 Although cells are not visually screened and selected for recording, the large number of cells recorded in parallel yields, for any given experiment (“run”), a much larger number of recordings than could be obtained manually. This high-throughput methodology has been used widely and successfully, both in industry for drug screening5,6,7 and in academic settings for basic studies of physiology and pharmacology.8,9,10,11,12 Furthermore, the existing manual patch-clamp technique does not allow for head-to-head and simultaneous comparison of a broad range of cell types, e.g., different types of neurons, under the exact same conditions, and necessitates culturing the primary cells on glass coverslips for extended periods of time.

Because the primary application of robotic patch-clamp systems has been in drug screening, these systems have to date been primarily used to study channels and receptors expressed in heterologous cell lines.6,7,8,9 More recently, there have been reports of use of these systems to study cardiac myocytes and dopaminergic neurons differentiated from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs),11,13,14 and some cardiac and cortical (the cortical study lacks methodological and biophysical details) cells.15,16,17,18 While these studies have provided invaluable information about ion channels and receptors expressed in heterologous systems and excitable cell types differentiated from stem cells (which are not always identical to primary counterparts), there is substantial evidence indicating that the functional properties of channels and receptors can vary, depending on the cell background in which they are expressed.19,20

High-throughput patch-clamp recordings from neurons have thus far not been obtained using high-throughput robotic methodology. Moreover, assessment of how the channels and receptors within a freshly isolated neuron contribute to its firing properties, while amenable to CC analysis, have not been demonstrated on high-throughput platforms.

In this paper, we show that patch-clamp analysis of freshly isolated neurons on a high-throughput platform is possible, and describe methodology using dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons,21 which provide a model of a complex neuronal cell type. Here, we specifically apply our approach to investigating the properties of voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels in these neurons, whose diversity and role within the sensory pathway is well-substantiated,22,23 and capitalize on the differential sensitivity of sensory Nav channels to tetrodotoxin (TTX), which provides a pharmacological means to further characterize the biophysical properties of DRG neurons. Our approach allows a completely blinded, unbiased, simultaneous, high-throughput, and comprehensive investigation of the biophysical properties of a broad range of freshly isolated neurons, immediately after tissue dissociation.24,25 This approach is applicable to a variety of cell types and can be used in multiple applications from extensive investigations of physiology to the studies on pharmacology in freshly isolated neurons. We also show that this methodology permits VC analysis followed by CC analysis on the same neuron in a high-throughput mode.

Results

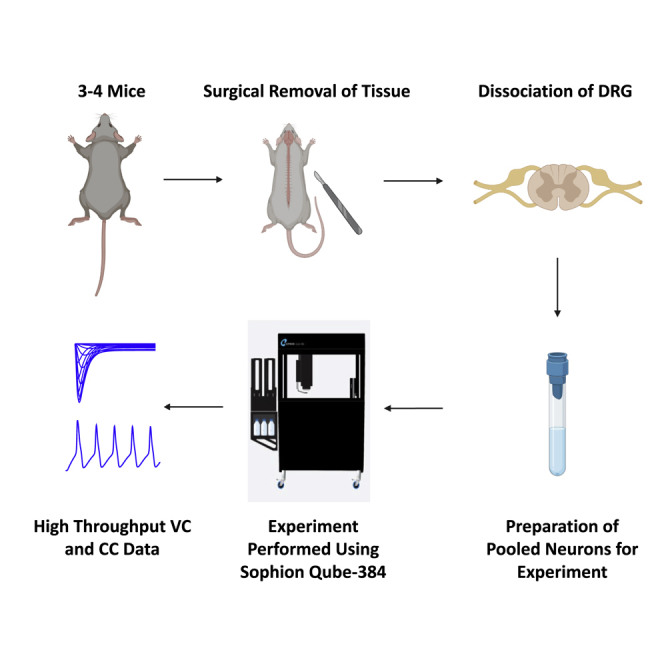

Freshly isolated neuron preparation and optimization

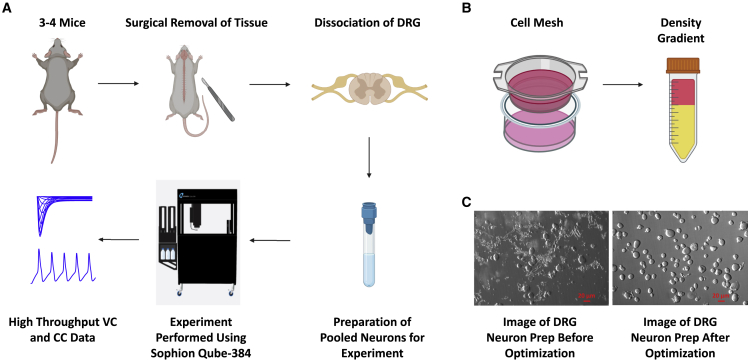

A typical experiment on automated patch-clamp systems requires tens to hundreds of thousands of neurons.26 Thus, a successful experiment requires certain criteria to be met: (1) high cell count, (2) high cell purity (i.e., no glia or tissue debris), (3) cells with healthy membranes (i.e., cells with round and smooth morphology, not vacuolated), and (4) in this study, to maintain neuronal diversity, we sought to ensure that cells with diverse sizes are retained and not filtered out during preparation. To maximize the success with cell count, we harvested and pooled DRG tissues from three to four (males and females) adult C57-BL6 mice (7–9 weeks old), which was followed by dissociation (Figures 1A and 1B). As shown in the left image in Figure 1C, after dissociation (mechanical trituration followed by enzyme incubation), cell suspension was a mixture of single neurons, undissociated big pieces, dissociated supporting cells, and dissociated small pieces of axons and myelin. To get pure single-neuron suspension, undissociated big pieces, dissociated supporting cells, and small pieces of axons and myelin needed to be removed. To remove the former, a 70-μm cell strainer was applied; to remove the latter, 15% BSA density gradient was applied twice. As shown in the right image in Figure 1C, after filtering with 70-μm mesh and 15% BSA density gradient, relatively pure single-neuron suspension was yielded. This cell preparation remains suitable for ∼3–4 h at room temperature, and can support two to four runs per preparation (Table S1). A more detailed step-by-step description of this approach is provided in the STAR Methods section.

Figure 1.

Workflow of the assay and cell preparation

(A) The general workflow of our new assay. We start off by harvesting DRG tissue from three to four adult mice and preparing neuronal cell suspension using standard methods, as explained in STAR Methods.

(B) Cell suspension if filtered using a 70-μM cell mesh, followed by a two rounds of cell purification on 15% BSA density gradient in DRG media.

(C) Images of DRG neuronal cultures using the standard protocol and after implementing the filtration and purification of the neuronal suspension on density gradients. We aimed to make sure we get as many neurons as possible while maintaining purity, healthy looking membranes, and diversity of cell sizes. Finally, cells were loaded onto the instrument to run VC/CC experiments.

Once the cells were transferred onto our automated patch-clamp system in DRG media, we used a custom suction protocol to both suck cells down toward the hole on the bottom of the well (Figure S1), and to break into the membrane to establish the whole-cell configuration. Because high calcium is known to form crystals with intracellular fluoride, which enhances seal quality,27 we perfused our cells with 20 mM Ca2+ saline solution and pulsed from −120 mV to −20 mV at 0.5 Hz for 30 cycles. Then, we washed the cells three times with our standard external solution to remove any residual high Ca2+ and pulsed the cells with the same protocol, as before. Finally, we waited an additional ∼2.5 min (to let cells stabilize) before applying our experimental VC and/or CC protocols. We were able to obtain high-quality recording from up to four experimental runs from the same neuronal prep. Each run produced ∼25–45 recordings (Figure S2A). These recordings underwent our pre-determined automated filters, as described next, and only the data that passed these filters were included in subsequent analyses. The data presented in this study came from seven independent preparations. On average, cells could last for 40–50 min (the length of our experimental run), with more cells surviving protocols such as steady-state inactivation and recovery from inactivation, but less so for activation protocol (Table S1).

Approach to data analysis

Unlike in heterologous expression systems, where only a single chosen ion channel is typically expressed, any given type of neuron (including DRG neurons) expresses a unique set of conductances.28,29,30,31,32,33,34 To address this issue, we modified the typical data analysis approaches that are commonly followed using high-throughput systems. We used a combination of equation-based fits, fit qualities, and quality check filters to identify the wells that first successfully patched neurons, and second, whether the quality of the recordings was sufficiently high for inclusion into our datasets. Because all our experiments started with a train of square pulses from −120 to −20 mV, we used the current amplitudes and the exponential decay (via the analysis software, Analyzer) of the macroscopic sodium current decay as primary filters to identify cells with real sodium currents (Figure S2A). We also used the Boltzmann function in Analyzer to further identify the cells that were properly clamped in all our activation and inactivation protocols.35 Finally, we imposed filters on patch resistances (e.g., Rseries<10 MΩ, [Figure S2B]) and capacitances (e.g., C > 10 pF, we argued that a smaller capacitance would not be from a real neuron) as a further quality check. A description of the filters is provided in Figure S3.

We used the unique identifier code (on our automated robotic platform) that details every cells’ position on the patching chip and encodes all experimental blocks to keep accurate records of all subsequent calculations and analyses of each individual datum. To further facilitate data analysis and filtration, we developed a Python-based analysis script that took the information that passed our filtration criteria in Analyzer as input, and performed subsequent mathematical filtration of the data and also automated data sorting and fitting functions (Supporting Information, Code/Instructions). This pipeline enabled rapid and robust analyses with multiple equations, as outlined below.

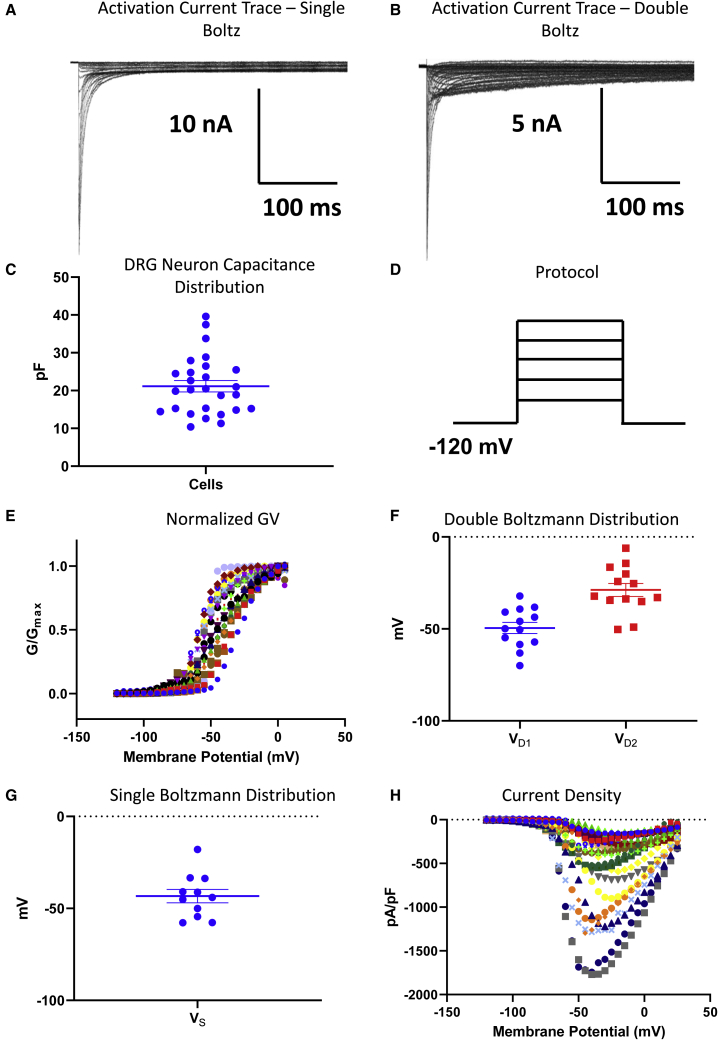

Nav channels activating properties

As in manual patch-clamp analysis, the first biophysical property we examined was Nav channel activation, in which we measured peak channel conductances at membrane potentials between −120 and +30 mV in a head-to-head comparison (Figures 2A–2D). We used capacitance as a proxy for neuronal size.36 We obtained activation recordings from cells with capacitances ranging from ∼10 to 40 pF (Figure 2C). As DRG neurons are known to express different ensembles of Nav channels with different electrophysiological signatures (e.g., voltage-dependence midpoints),34 we fit the normalized conductance-voltage (GV) relationship from each neuron with both double and single Boltzmann equations. In cells where the two terms of the double Boltzmann fit were very close, the fit procedure failed (signifying that a single Boltzmann was representative of the data), and the cell was binned in the single Boltzmann category. If the cell could be fit by both a single and double Boltzmann model, we used the quality of the fit (based on the root-mean-square deviation number, which is better when a double Boltzmann fit succeeds), to bin the data in the double Boltzmann category. The resulting midpoints from the double (VD1 and VD2) and single (VS) Boltzmann fits are shown (Figures 2E–2G). As expected, we found that most of the data were better fit with a double Boltzmann fit (indicative of multiple Nav subtypes); in addition, in both distribution bins, there was an expected variability in the midpoints, indicative of the broad range of Nav channel ensembles on a cell-by-cell basis.

Figure 2.

Activating properties of Nav channels in freshly isolated DRG neurons

(A and B) Sample traces of data that were either better fit with single (A) or double (B) Boltzmann equations.

(C) The distribution of capacitances of the cells that were used in our final analysis. The capacitances were measured experimentally for all cells.

(D) The standard VC protocol that was used to elicit the currents. The cells were held at −120 mV, followed by depolarizing step-pulses.

(E–G) All the GV data from each neuron. Each relationship displays normalized conductance as a function of membrane potential. The relationships in this panel were run with both single and double Boltzmann functions, and (F) if the fit quality mathematically was better with double, VD1 (i.e., V1/2’s) and VD2 were binned in (F); (G) if single Boltzmann worked better, the VS was put into the bin in (G).

(H) The current densities of each neuron shown as pA/pF as a function of membrane potential.

In Figure 2H, we show a plot of sodium current density as peak INa divided by membrane capacitance (pA/pF) as a function of membrane potential. The current density distribution further displays the heterogeneity of Nav currents across the DRG neurons.

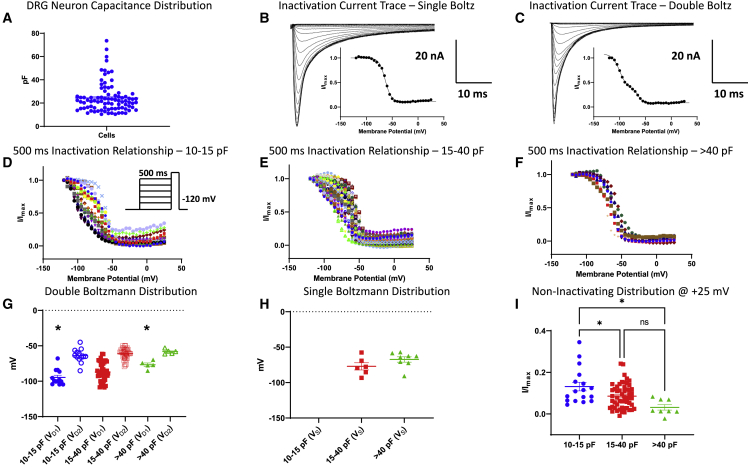

Correlation between Nav channel inactivation and membrane capacitance

We next measured the voltage-dependence of steady-state inactivation of our DRG neurons from a 500-ms pre-pulse (Figure 3). Generally, durations that are in the range of few hundreds of milliseconds are considered more implicative of fast inactivation than slow inactivation. However, 500 ms may appear to trigger an overall macroscopic intermediate inactivation (some channels undergoing fast inactivation mixed with channels undergoing slow inactivation).37,38,39 We recorded from neurons with capacitances ranging from ∼10 to 75 pF (Figure 3A). Based on the range that we were able to obtain, we divided these cells into three bins: 10 to <15 pF (small), 15 to <40 pF (medium), and >40 pF (large). Next, we applied the same double versus single Boltzmann fitting mathematical comparison to each neuron within the capacitive bins (Figures 3B–3H). Small- and large-diameter neurons express different combinations of TTX-R (tetrodotoxin-resistant) and TTX-S (tetrodotoxin-sensitive) currents.34,40 However, studies suggest that both Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 are expressed in neurons across various diameters,34,41,42 albeit to different extents. Our results indicate that all the cells in our smallest capacitance bin are fit better with a double Boltzmann (Figure 3D). The bi-phasic relationship is noticeably visible across every neuron’s IV relationship. Expectedly, the mean VD1 from the small bin was the most hyperpolarized of all three bins, suggestive of the presence of the TTX-S Nav1.7 (the V1/2 of Nav1.7 is the most hyperpolarized, which will shift the midpoint to the left) and TTX-R Nav1.9 channels34,40,41,42; whereas VD2 was relatively more depolarized, which is suggestive of a TTX-R Nav1.8 current (the V1/2 of Nav1.8 is the most depolarized, which will shift the midpoint to the right) (Figure 3G).

Figure 3.

Steady-state inactivation of Nav channels using a 500-ms pre-pulse

(A) The distribution of the capacitance sizes we got from our experiments that were used in all subsequent analyses.

(B and C) Samples of single (B) versus double (C) Boltzmann traces/curves.

(D) The current-voltage (IV) relationship for neurons within the 10–15 pF capacitive bin. The neurons within this bin have a clear biphasic distribution, and most of the Nav channels in these cells do not fully inactivate, i.e., there is a residual persistent current, as indicated but the low ends of the IV curves.

(E) The middle bin (15–40 pF) has the broadest distribution and falls in-between (D) and (F).

(F) The Nav channels in cells in the large bin (>40 pF) tend to fully inactivate, as indicated by the low ends of the curves that display minimal persistent currents.

(G) Distribution of cells that fit better with double Boltzmann function. The V1/2’s suggest that the smaller cells are more heterogeneous, and likely possess both Nav1.7 (with the most negative inactivation V1/2) and TTX-R currents, but as the cells become bigger, as in third bin, the Nav1.7 effect becomes smaller.

(H) Displays the distribution of cells that were better fit with single Boltzmann. Whereas none of the cells in the small bin fit with single Boltzmann, some were better fit with a single Boltz in the mid and larger bins.

(I) The plot of non-inactivating current (persistent current) in each bin. ∗Indicates p < 0.0001 for (G), p = 0.0406 (small versus mid), p = 0.0226 (small versus large) for (I).

We found that there were some neurons in each of the medium and large capacitive bins that fit better with single Boltzmann (Figures 3E–3H); however, most neurons were better fit with a double Boltzmann. Importantly, VD1 from the small bin was significantly more hyperpolarized than the large bin, which is consistent with a stronger presence of Nav1.6 than Nav1.7 in the larger cells (p < 0.05). Next, we measured the amount of non-inactivating current at the most positive potential (+25 mV) from the steady-state inactivation curves43 (Figure 3I). We found that the small capacitance cells had significantly larger persistent currents than either medium or large capacitance neurons (p < 0.05). This is consistent with the idea that as the cells become larger, they express more TTX-S currents, which have less persistent currents than TTX-R Nav channels.34,41,42

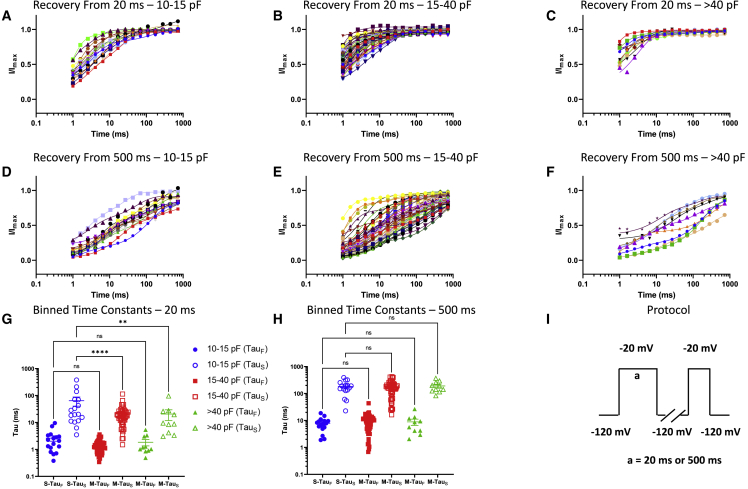

Nav channels in larger cells recover faster from fast inactivation

To further assess inactivation properties, we then measured the recovery from inactivation from the same three capacitive bins (Figure 4). This was done after depolarizing pre-pulse durations of 20 ms (indicative of fast inactivated) or 500 ms (indicative of intermediate inactivated), from a holding-potential of −120 mV. To measure recovery from inactivation, we held the channels in our cells at −120 mV to ensure that the channels were fully available, and then we pulsed the channels to −20 mV at one of the noted durations and allowed different time intervals at −120 mV to measure recovery as a function of time. The normalized recovery following the pre-pulse in each bin were plotted and fit with a biexponential function (Figures 4A–4F).

Figure 4.

Recovery from 20-ms (fast) and 500-ms (intermediate) inactivation

(A–F) (A–C) Data divided up using the same bins as above for 20 ms, and (D–F) for 500 ms.

(G) Displays the distribution of TauFast and TauSlow from 20 ms across the bins. There was no statistical difference in the fast component of recovery across the bins, but there was a clear and significant slowing of the TauSlow kinetics as the cells became smaller, indicative of the stronger presence of TTX-R channels. ∗∗Indicates p = 0.0054, ∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(H) At 500 ms, there were no significant differences across bins.

(I) The protocols that were used to measure the kinetics of recovery from 20- or 500-ms depolarizations. The S, M, and L designations on the X axis (G, H) refer to small (10–15 pF), medium (15–40 pF), and large (>40 pF) neurons, respectively.

Our results suggested that larger neurons have faster recovery kinetics from fast inactivation from 20 ms, as shown by the τSlow component of the recovery (Figure 4G). These faster kinetics are consistent with a higher expression of TTX-S currents, including Nav1.6 (along with lesser expression of Nav1.7 and Nav1.9).34,41,42,44 Expectedly, the τFast component of recovery was not significantly different across bins.45 As we increased the depolarization duration to 500 ms, we found that there were no significant differences in either recovery time constants across the capacitive bins (Figure 4H). These results could be due to the accumulation of a mixture of fast and slow inactivation in the different Nav channels that have varying kinetic properties over the course of 500 ms.46,47 Therefore, the two populations become inseparable. (Each member of the Nav channel family has its own signature voltage-dependences and kinetics; over the course of 500 ms (intermediate) depolarizations, each Nav subtype displays varying amounts of channels in the fast and slow inactivated states; this combined with the presence of multiple types of Nav channels could cause the populations to become inseparable when measured with a single test pulse after the 500 ms pre-pulse.46,48) The pulse protocol we used in these experiments is shown in Figure 4I.

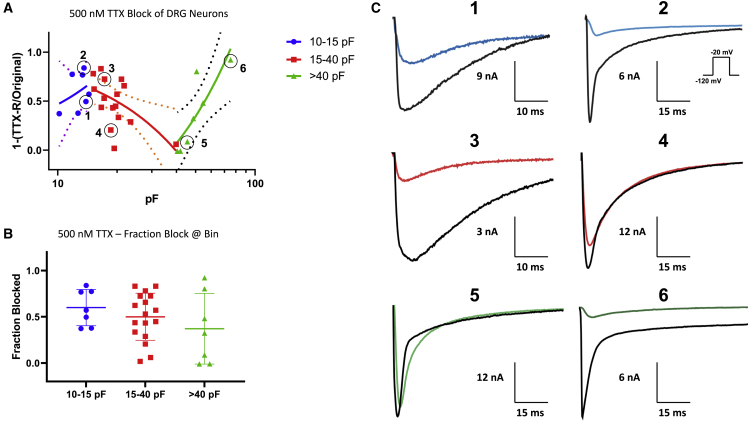

Pharmacological block of sodium current using TTX

Sodium channels within neurons fall into two broad classes on the basis of their sensitivity to TTX. To characterize the TTX sensitivity of our DRG neurons across the capacitive bins, we voltage-clamped neurons (held at −120 mV and pulsed to −20 mV to elicit maximal current). Then we perfused 500 nM TTX, to block all the TTX-S Nav channels (half maximal inhibitory concentration of TTX-S channels is ∼10–30 nM 35,39), and measured peak amplitude differences before and after TTX perfusion (Figure 5). In Figure 5A, we show fraction of TTX-S current versus capacitance, which expectedly shows variability on the smaller (10–15 pF) end of the spectrum. In the medium-sized (15–40 pF) capacitances, there is an increase in the TTX-R component, which is likely dominated by Nav1.8. In the large (>40 pF) bin, there is an increase in the TTX-S current, which is likely predominantly Nav1.6,34,41,42,44 as suggested by the data shown in Figure 3. The variability of the distribution of the sensitivity to TTX in each bin and sample traces are shown in Figures 3B and 3C.

Figure 5.

Pharmacological block by 500 nM TTX

(A) The fraction of Nav current inhibited by TTX versus capacitance. There is variability in TTX response (smaller cells). In cells with capacitances from ∼20 to 40 pF, there is a stronger presence of TTX-R (likely Nav1.8/9). The data were fitted with a simple linear regression equation to display the trend of TTX sensitivity of cells as a function of capacitance. The dotted lines display the 95% confidence intervals.

(B) The variable distribution of fraction of the current blocked across each bin, and (C) sample traces from cells that are circled in (A).

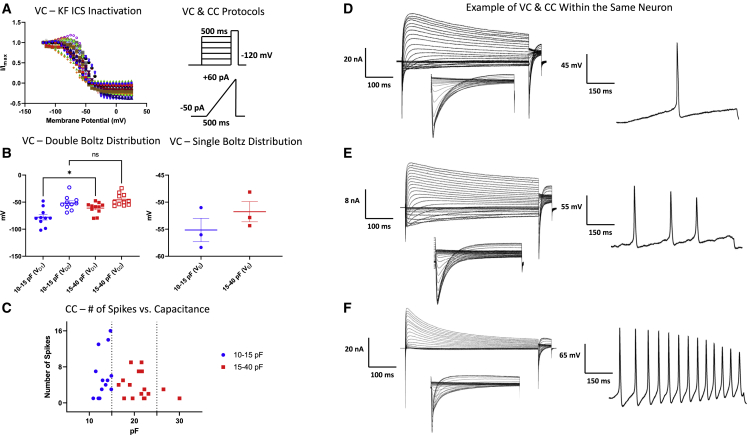

Measuring ionic conductance and cellular excitability within the same neuron

Only a few published studies have used high-throughput robotic patch-clamp for CC, and to date, robotic patch-clamp platforms have not achieved CC and VC in the same cell. In this study, we used a potassium fluoride (KF)-based intracellular solution to perform both VC and CC experiments on the same neurons. We first performed the same voltage protocol we used to measure steady-state inactivation and applied the same double versus single Boltzmann fitting (Figures 6A and 6B). As expected, in the absence of cesium, the outward potassium current caused the normalized current relationship to go below 0 as the membrane potential became more depolarized49 (Figure 6A). As before, most of the cells were better fit with a double Boltzmann (Figure 6B), and the overall trend of the midpoints was consistent with Figure 3. Next, we applied −50 pA of current to the same neurons and ramped it up to +60 pA over the course of 500 ms (reliable resting membrane potential measurements using this system requires further optimization from the instrument manufacturer; these include compensation for leak current that causes Nav channel inactivation in CC mode). In Figure 6C, we show the number of spikes per ramp versus cell capacitance. These data suggest that there is variability in excitability, and that overall, excitability may be lower among the larger neurons. This is consistent with threshold differences between different-sized neurons, which have been previously investigated.50 Sample AP and macroscopic sodium and potassium currents from the same neurons (capacitances: ∼12, 15, 23 pF) are shown in Figures 6D–6F.

Figure 6.

VC and CC in the same neurons

(A) Inactivating current-voltage (IV) relationship of Nav channels in KF internal solution. Protocols are on the right.

(B) Comparison of double versus single Boltzmann approach, as before (the biggest cell we got in these experiments was 30 pF). ∗Indicates p = 0.0104.

(C) Number of AP spikes that were elicited using a standardized ramp CC protocol.

(D–F) Sample VC and CC traces for high and low spiking neurons are shown.

Discussion

Traditional whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology is the gold-standard approach for high-fidelity analysis of the biophysical properties of excitable cells.1,3,51 However, manual recordings have limitations, which make investigations of freshly isolated excitable cells, particularly complex neuronal cells, remarkably challenging. Each particular cell type is home to various ensembles of ion channels, which can range from having multiple subtypes of the same family of channels that conduct the same ion, to ones that conduct different ions. For instance, in the cardiac tissue, multiple potassium and calcium currents are expressed that contribute various phases of the cardiac AP52; a similar situation exists in the central and peripheral nervous systems, where multiple Nav currents contribute to excitability.23,34,40,53,54,55,56 Gaining a better understanding of any of these cell types requires a set of electrophysiological enhancements to the traditional technique that we provide here. In this proof-of-concept study, we applied adaptations to an automated high-throughput electrophysiological platform to the study of DRG neurons, which provide a model of neuronal cell types that manifests a high degree of diversity, and is relevant to pain, a global unmet medical need.57 However, this approach is also applicable for the study of other excitable cell types.

DRG neurons serve to detect a multitude of sensory modalities. DRG neurons have specialized membrane properties—each neuronal membrane is home to various types of ion channels and receptors, which are present in varying ensembles that serve different purposes. These include Nav, potassium (Kv), and transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, among others.28,29,30,31,32,33,34 The interplay of these channels and receptors is essential for the normal functioning of DRG neurons and for pathological outcomes when their normal function is modified in diseased states. These properties made DRG neurons a good case study for application of the novel approach described in this paper.

We chose to apply our approach to investigate DRG neurons because they express multiple Nav channels. Nav1.7–1.9 are predominantly expressed in peripheral neurons and Nav1.1/6 are expressed in both central and peripheral neurons.34,58,59,60 Among these channels only Nav1.8 and Nav1.9 are resistant to TTX, and the remaining isoforms can be blocked by low nanomolar concentrations of TTX.35 Nav1.7 is regarded as the major Nav isoform that acts as a threshold channel to trigger APs in small DRG neurons, and a malignant hyperactivity of this channel is responsible for several pain syndromes.61,62 Furthermore, we have previously demonstrated a physiological interaction between Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 channels, which is essential for regulating neuronal firing of DRG neurons in which these two channels are present. Importantly, we have recently shown that gain-of-function variants in Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 channels significantly attenuate firing of DRG neurons that express strong gain-of-function mutations in Nav1.7 channels from patients with the pain disorder inherited erythromelalgia.63,64 Thus, the ability to record multiple ion conductances in VC mode and to assess neuronal excitability properties in CC mode in the same cell (which is possible using the existing manual patch-clamping method, but is challenging to achieve), as we have successfully done in this study will be a major advantage to better understand well-functioning sensory physiology.

Previous studies have developed other robotic-based patch-clamp methods that investigate in vivo electrophysiological properties of cells.65,66,67 The method developed by Kodandaramaiah et al.66 provides a means for analyzing temporal impedance changes in live animals, with direct applications described in cortex and hippocampus areas. The technique developed by Annecchino et al.65 uses a photon-based method that is also used for in vivo recordings from the neocortex and cerebellum of mouse brains. The approach described in this study provides a novel methodology for investigating the in-depth electrophysiological properties of freshly isolated cells (e.g., peripheral DRG neurons), in vitro. The most direct comparison to our approach is traditional manual patch-clamp recordings of primary cells that have undergone dissociation, isolation, and culturing on glass coverslips. In this case, the throughput is in the order of ∼1–10 cells per day, whereas with our novel approach it is possible to record from up to 200 cells per day (Tables 1 and S1). Another previously published method added automation to traditional manual patch-clamp rigs that use glass pipettes (as opposed to planar patch in our setup).68,69,70 This method possesses many of the same advantages of traditional patch-clamp, with the added benefits of automation; however, it does not provide the advantages of increased throughput or the option of head-to-head comparison of multiple cell-types, as in our method.

Table 1.

Comparison of our assay to traditional manual patch-clamp, with respect to freshly isolated DRG neurons

| Type | Cells recorded/day | Perfusion | VC/CC in same neuron | Cell selection | Data analysis | Overnight coverslip incubation | Diverse neuron, head-to-head comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current method | ∼1–10 | yes | no | experimenter bias | subconscious bias | yes | no |

| Novel assay | up to ∼200 (Assuming 2 preps/day) | yes | yes | blinded | unbiased | no | yes |

More information on the numbers associated with our assay can be found in the supplemental information.

In summary, our results demonstrate that patch-clamp analysis of freshly isolated neurons on a high-throughput platform is possible. Using DRG neurons as a model, we describe an approach that allows a completely blinded, unbiased, simultaneous, high-throughput, and comprehensive investigation of the biophysical properties of a broad range of freshly isolated neurons, immediately after tissue dissociation. Notably, this methodology permits CC analysis following VC study, on the same neuron, in a high-throughput mode. This approach provides a basis for high-throughput physiological and pharmacological study of a variety of types of freshly isolated neurons.

Key advantages

By taking advantage of a robotic automated patch-clamp system, our approach allows for a high-throughput and simultaneous (under the same recording conditions) analysis of a broad range of neurons. Although this study describes Nav channels in DRG neurons, our approach can be used to investigate the properties of other native ion channels and/or receptors, including Kv, Cav, and TRP channels, among others, in a variety of types of excitable cells.

Another key advantage of this approach is that every step from cell selection to final inclusion/exclusion of a datum in a set is unbiased and automated, although having an experienced electrophysiologist validating every step is crucial. The extensive quality control and mathematical filtrations we impose onto the dataset further minimizes the impact of the experimenter’s subconscious bias.

The development of our Python analysis script enables us to mathematically fit (and quality control) the same datum with multiple equations. Using the parameters of the resulting fits, we can determine if a neuron more likely expresses Nav channels (or other conductances) that are biophysically similar, or whether it expresses a set of biophysically distinct Nav subtypes. Our experiments were performed in primary cells, and it is highly unlikely that any given neuron expressed just one Nav subtype; thus, a caveat is that, if most of the Nav current is composed of subtypes that are biophysically similar, then a single Boltzmann function could fit better (e.g., a neuron that mostly expresses Nav1.1 and Nav1.6). In the case of smaller neurons where both TTX-R and TTX-S (mostly Nav1.7) current is expected to be expressed, our Python script suggests that cells fit better with a double Boltzmann. We should note, however, that the presence of a specific channel can still be investigated using pharmacological assays when isoform-selective reagents are available, and multiple channels could be investigated if these reagents are easily washed out.

Cell preparation for traditional patch-clamping typically involves overnight culturing typically at 37°C of the dissociated neurons on glass coverslips.24,25 This process may conceivably alter the cell biology of these neurons. However, our approach allows for an investigation of neurons within hours of dissection and dissociation from the intact tissue. Thus, recordings can be obtained temporally closer (as well as head-to-head) to when the cells were in an intact animal. This advantage could work in concert with our assay’s ability to perform VC and CC in the same freshly isolated cell to provide measurements of the biophysical properties of these cells after relatively short times, ex vivo. A comparison of the traditional versus our method is provided in Table 1. Finally, this method could be used to perform analyses on animals treated with drugs or injected with adeno-associated viruses, etc. in a high-throughput manner, providing new avenues of research into DRG neurons.

Major limitations

Whereas the unbiased cell selection in this approach is an important advantage for many types of studies, it is a limitation if one seeks to investigate the effects of a transiently transfected construct in a native primary neuronal background. Because the patching and recording of the cells occurs randomly, we could not currently force the robotic system to pick only the cells that, for instance, express a fluorescent tag. This limitation may be slightly remedied if one uses a functional marker that normally does not exist in the cell type of interest as a co-transfecting marker.71 Alternatively, transfected cells could be isolated by cell sorting using GFP fluorescence. This idea is based on the standard use of GFP tags that are commonly used in manual patch-clamp recordings to identify the cells that express the cDNA of interest. These potential approaches should be tested and developed in future studies.

The second major limitation is that, in neurons, it is currently not possible to patch any of the neuronal processes (e.g., axons and dendrites). As shown in Figure 1C, our cell preparation process culminates in isolated and round neurons; thus, all the recordings are from neuronal somas (recording from processes is also challenging using manual patch-clamp).

We also found that success rate is lower for the analysis of Nav activation than inactivation. This is because Nav channels have fast kinetics, which when combined with very large sized currents can cause clamping challenges.

The requirement for high cell counts is also a technical challenge, because it requires pooling of neurons from multiple animals. However, as tissue collection methods are further optimized, this challenge may be overcome.

Finally, although we implemented this new methodology using one particular robotic patch-clamp platform, the Sophion Qube system, we would note that with appropriate modification, this approach could be used on other similar high-throughput automated electrophysiological platforms.

Concluding remarks

In the aggregate, our results demonstrate the feasibility of patch-clamp analysis of freshly isolated neurons on a high-throughput platform. This approach allows a blinded, unbiased, simultaneous, high-throughput, and comprehensive VC investigation of freshly isolated neurons, immediately after tissue dissociation. Moreover, CC analysis can be carried out following VC study, on the same neuron, in a high-throughput mode. This approach provides a basis for high-throughput physiological and pharmacological study of a variety of types of channels and receptors within multiple types of freshly isolated neurons.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Liberase TM | Roche | 5401119001 |

| Liberase TL | Roche | 05401020001 |

| Papain | Worthington Biomedical | 9001-73-4, EC 3.4.22.2 |

| Trypsin inhibitor | Sigma | 9035-81-8 |

| DMEM/F12 | Invitrogen | 11320033 |

| Streptomycin | Invitrogen | 15140122 |

| L-glutamine | Invitrogen | 25030081 |

| Fetal bovine serum | HyClone | SH30071.03IH25-40 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: WT C57Bl/6 | Envigo | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Analyzer | Sophion | https://sophion.com/ |

| ViewPoint | Sophion | https://sophion.com/ |

| Prism | Graphpad Software, Inc. | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Custom code | This paper |

https://github.com/emrekiziltug3/AutomatedClampAnalysis https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7411103 |

| Python | Python Software Foundation | https://www.python.org |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel |

| Other | ||

| 70 μm Mesh | Beckton Dickinson | 352350 |

| Qube-384 | Sophion | https://sophion.com/products/high-throughput-screening-on-qube/ |

| Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope | Nikon | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Stephen G. Waxman (stephen.waxman@yale.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

Animal studies followed a protocol approved by the Department of Veterans Affairs West Haven Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Experiments were performed using both male and female animals. DRGs from three to four 7-9.5-week-old male and female C57Bl/6 mice were harvested and dissociated according to our previous report24 with some modifications that are described below.

Method details

Preparation of DRG neurons from adult mouse

DRGs (at least 24 DRGs from each mouse) were harvested and immediately put in ice-cold complete saline solution (CSS) (in mM: 137 NaCl, 5.3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 25 sorbitol, 3 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.2 with NaOH). After all the DRGs were harvested, DRGs were transferred to 37°C enzyme solution - 0.5 U/mL Liberase TM (Roche) and 0.6 mM EDTA in CSS for a 20-min incubation at 37°C, followed by a 15-min incubation at 37°C in another enzyme solution - 0.5 U/mL Liberase TL (Roche), 0.6 mM EDTA, and 30 U/mL papain (Worthington Biochemical) in CSS. DRGs were then centrifuged and triturated in 0.5 mL of 1.5 mg/mL BSA (low endotoxin) and 1.5 mg/mL trypsin inhibitor (Sigma) in DRG media [DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen) with 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Invitrogen), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), and 10% fetal bovine serum (Hyclone)]. After trituration, undissociated pieces were removed by filtering through a 70-μm mesh (Becton Dickinson). To remove small supporting cells and small pieces of dissociated axons and myelin, density gradients with 15% BSA were applied twice. Cells were pelleted and re-suspended with 1 mL DRG media, layered on top of 15% BSA solution and centrifuged at 250 g for 10 min at 4°C; pelleted cells were then re-suspended with DRG media and went through a second round of 15% BSA purification. The cell pellet was re-suspended with 1 mL of DMEM/F12 (4°C) to get single-cell suspension. Five μL of cell suspension was counter stained with five μL of trypan blue to check neuronal number, viability, and purity. Single-cell suspension [225 ± 75 K (mean ± SD) live neurons total] was diluted to 3 mL in DMEM/F12 (4°C) before delivering to the 384 well chip on the Qube-384 instrument (Sophion A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark). An aliquot of the cell suspension was plated on a 35-mm Tissue Culture-treated culture dish and imaged using a Nikon microscope (Eclipse TE2000-U Inverted Microscope).

Automated patch-clamp

Automated patch-clamp recording was used for all experiments. Sodium currents were measured in the whole-cell configuration using a Qube-384 automated voltage-clamp system. Intracellular solution contained (in mM): 120 CsF (or KF for CC experiments), 10 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH7.2 with CsOH. The extracellular recording solution contained (in mM): 145 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, adjusted to pH7.4 with NaOH. Liquid junction potentials calculated to be ∼7 mV were not adjusted for. Currents were low pass filtered at 5 kHz and recorded at 25 kHz sampling frequency. Series resistance compensation was applied at 100% and leak subtraction enabled. The Qube-384 temperature controller was used to maintain recording for all experiments at 22 ± 2°C at the recording chamber. Appropriate filters for series resistance (<10 MOhm) and Nav current magnitude (more than baseline in the inward direction, 0 nA) were routinely applied to exclude poor quality recordings. Data analysis was performed using Analyzer (Sophion) and Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) software. More relevant information could be found in supplemental information.

Activation protocols

To determine the voltage-dependence of activation, we measured the peak current amplitude at test pulse potentials ranging from −120 mV to +30 mV in increments of +5 mV for 500 ms. Channel conductance (G) was calculated from peak INa:

| (Equation 1) |

where GNa is conductance, INa is peak sodium current in response to the command potential V, and ENa (measured on IV relationships) is the Nernst equilibrium potential. Calculated values for conductance were fit with the Boltzmann equation:

| (Equation 2) |

where G/Gmax is normalized conductance amplitude, Vm is the command potential, V1/2 is the midpoint voltage and k is the slope.

Steady-state inactivation protocols

The voltage-dependence of fast-inactivation was measured by preconditioning the channels from −120 to +30 mV in increments of 5 mV for 500 ms, followed by a 10 ms test pulse during which the voltage was stepped to −20 mV. Normalized current amplitudes from the test pulse were fit as a function of voltage using the Boltzmann equation:

| (Equation 3) |

where Imax is the maximum test pulse current amplitude.

Double Boltzmann for both activation and inactivation

Double Boltzmann fit was using the following equations:

| (Equation 4) |

| (Equation 5) |

| (Equation 6) |

Where y0 is offset, A is span, x01 and x02 are midpoints, k1 and k2 are slope factors, and p is fraction.

Recovery from inactivation protocols

Recovery from inactivation was measured by holding the channels at −120 mV, followed by a depolarizing pulse to 0 mV, then the potential was returned to −120 mV for different time periods. This was followed by a depolarizing 10 ms test pulse to 0 mV to measure availability. Recovery from inactivation was measured after pre-pulse durations of 20 ms and 500 ms and fit with a biexponential function of the form:

| (Equation 7) |

| (Equation 8) |

| (Equation 9) |

where t is time in seconds, Y0 is the Y intercept at t = 0, KFast and KSlow are rate constants in units the reciprocal of t, PercentFast the fraction of the Y signal attributed to the fast-decaying component of the fit.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Normalization was performed in order to control the variations in sodium channel expression and inward current amplitude and in order to be able to fit the recorded data with a Boltzmann function (for voltage-dependences) or a bi-exponential function (for time courses of inactivation). The Sophion Qube is an automated electrophysiology instrument that is blinded to cell selections and experimentation, and selection is performed in a randomized manner. All subsequent data filtering and analysis is performed in a non-biased manner, in which automated filters are applied to the entire dataset from a given Qube run. Fitting and graphing were done using Prism 9 software (Graphpad Software Inc., San Diego, CA), unless otherwise noted. All statistical p values report the results obtained from tests that compared experimental conditions to the control conditions. One-way ANOVA: when each condition was being compared other conditions; or t-test: when overall 2 conditions were being compared. A level of significance α = 0.05 was used with p values less than 0.05 being considered to be statistically significant. All values are reported as means ± SE of means (SEM) or errors in fit, when appropriate, for n recordings/samples. Values are presented as mean ± SEM with probability levels less than 0.05 considered significant. The declared group size is the number of independent values, and that statistical analysis was done using these independent values.

The Python code, associated equations, and instructions to use the code are available as supplemental information (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7411103).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the US Department of Veterans Affairs Rehabilitation Research and Development Service. The Center for Neuroscience and Regeneration Research is a Collaboration of the Paralyzed Veterans of America with Yale University. M.-R.G. is a Banting Fellow (grant number: 471896) and is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). S.T. was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Medical Scientist Training Program Training Grant T32GM136651.

Author contributions

M.-R.G. designed the study and protocols/experiments, assembled data, performed experiments, developed assays, analyzed data, made figures, wrote and edited the manuscript, interpreted data, and performed conceiving of experiments. S.T. wrote Python code, contributed to data analysis, contributed intellectually important ideas, and edited the manuscript. P.Z. performed neuron dissection and dissociation and optimized cell culture. E.K. wrote Python code and contributed to data analysis. M.E. contributed important ideas. S.D.D.-H. contributed to project conceptualization, analysis, and funding and editing of the manuscript. S.G.W. contributed to project conceptualization and funding, data curation, formal analysis, supervision, validation, investigation, methodology, and writing and review and editing of manuscript and provided project administration.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Published: January 12, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crmeth.2022.100385.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All the data published in this paper will be available from the lead contact upon request.

-

•

The Python code is available as supporting information in this manuscript.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Hamill O.P., Marty A., Neher E., Sakmann B., Sigworth F.J. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neher E., Sakmann B. Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres. Nature. 1976;260:799–802. doi: 10.1038/260799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sigworth F.J., Neher E. Single Na+ channel currents observed in cultured rat muscle cells. Nature. 1980;287:447–449. doi: 10.1038/287447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raju T.N. The nobel chronicles. 1991 Erwin Neher (b 1944) and bert Sakman (b 1942) Lancet (London, England) 2000;355:1732. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)73143-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chambers C., Witton I., Adams C., Marrington L., Kammonen J. High-throughput screening of Na(V)1.7 modulators using a Giga-seal automated patch clamp instrument. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2016;14:93–108. doi: 10.1089/ADT.2016.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson J.P., Focken T., Khakh K., Tari P.K., Dube C., Goodchild S.J., Andrez J.C., Bankar G., Bogucki D., Burford K., et al. NBI-921352, a first-in-class, Na V 1.6 selective, sodium channel inhibitor that prevents seizures in Scn8a gain-of-function mice, and wild-type mice and rats. Elife. 2022;11:e72468. doi: 10.7554/ELIFE.72468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahuja S., Mukund S., Deng L., Khakh K., Chang E., Ho H., Shriver S., Young C., Lin S., Johnson J.P., Jr., et al. Structural basis of Nav1.7 inhibition by an isoform-selective small-molecule antagonist. Science. 2015;350:aac5464. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghovanloo M.-R., Shuart N.G., Mezeyova J., Dean R.A., Ruben P.C., Goodchild S.J. Inhibitory effects of cannabidiol on voltage-dependent sodium currents. J. Biol. Chem. 2018;293:16546–16558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.004929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghovanloo M.-R., Estacion M., Higerd-Rusli G.P., Zhao P., Dib-Hajj S., Waxman S.G. Inhibition of sodium conductance by cannabigerol contributes to a reduction of dorsal root ganglion neuron excitability. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2022;179:4010–4030. doi: 10.1111/bph.15833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Labau J.I.R., Alsaloum M., Estacion M., Tanaka B., Dib-Hajj F.B., Lauria G., Smeets H.J.M., Faber C.G., Dib-Hajj S., Waxman S.G. Lacosamide inhibition of Na V 1.7 channels depends on its interaction with the voltage sensor domain and the channel pore. Front. Pharmacol. 2021;12:791740. doi: 10.3389/FPHAR.2021.791740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potet F., Egecioglu D.E., Burridge P.W., George A.L. GS-967 and eleclazine block sodium channels in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Mol. Pharmacol. 2020;98:540–547. doi: 10.1124/MOLPHARM.120.000048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghovanloo M.-R., Goodchild S.J., Ruben P.C. Cannabidiol increases gramicidin current in human embryonic kidney cells: an observational study. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0271801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0271801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franz D., Olsen H.L., Klink O., Gimsa J. Automated and manual patch clamp data of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons. Sci. Data. 2017;4:170056. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2017.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosholm K.R., Badone B., Karatsiompani S., Nagy D., Seibertz F., Voigt N., Bell D.C. Adventures and advances in time travel with induced pluripotent stem cells and automated patch clamp. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022;15:898717. doi: 10.3389/FNMOL.2022.898717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seibertz F., Rapedius M., Fakuade F.E., Tomsits P., Liutkute A., Cyganek L., Becker N., Majumder R., Clauß S., Fertig N., Voigt N. A modern automated patch-clamp approach for high throughput electrophysiology recordings in native cardiomyocytes. Commun. Biol. 2022;5:969. doi: 10.1038/S42003-022-03871-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obergrussberger A., Rinke-Weiß I., Goetze T.A., Rapedius M., Brinkwirth N., Becker N., Rotordam M.G., Hutchison L., Madau P., Pau D., et al. The suitability of high throughput automated patch clamp for physiological applications. J. Physiol. 2022;600:277–297. doi: 10.1113/JP282107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Obergrussberger A., Friis S., Brüggemann A., Fertig N. Automated patch clamp in drug discovery: major breakthroughs and innovation in the last decade. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2021;16:1–5. doi: 10.1080/17460441.2020.1791079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toh M.F., Brooks J.M., Strassmaier T., Haedo R.J., Puryear C.B., Roth B.L., Ouk K., Pin S.S. Application of high-throughput automated patch-clamp electrophysiology to study voltage-gated ion channel function in primary cortical cultures. SLAS Discov. 2020;25:447–457. doi: 10.1177/2472555220902388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummins T.R., Aglieco F., Renganathan M., Herzog R.I., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Nav1.3 sodium channels: rapid repriming and slow closed-state inactivation display quantitative differences after expression in a mammalian cell line and in spinal sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:5952–5961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05952.2001. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11487618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han C., Estacion M., Huang J., Vasylyev D., Zhao P., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Human Nav1.8: enhanced persistent and ramp currents contribute to distinct firing properties of human DRG neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2015;113:3172–3185. doi: 10.1152/JN.00113.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dib-Hajj S.D., Cummins T.R., Black J.A., Waxman S.G. From genes to pain: nav1.7 and human pain disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dib-Hajj S.D., Yang Y., Black J.A., Waxman S.G. The NaV1.7 sodium channel: from molecule to man. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn3404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Sodium channels in human pain disorders: genetics and pharmacogenomics. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2019;42:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-070918-050144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dib-Hajj S.D., Choi J.S., Macala L.J., Tyrrell L., Black J.A., Cummins T.R., Waxman S.G. Transfection of rat or mouse neurons by biolistics or electroporation. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1118–1126. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cummins T.R., Rush A.M., Estacion M., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Voltage-clamp and current-clamp recordings from mammalian DRG neurons. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1103–1112. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milligan C.J., Möller C. Automated planar patch-clamp. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;998:171–187. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-351-0_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lei C.L., Fabbri A., Whittaker D.G., Clerx M., Windley M.J., Hill A.P., Mirams G.R., de Boer T.P. A nonlinear and time-dependent leak current in the presence of calcium fluoride patch-clamp seal enhancer. Wellcome Open Res. 2020;5:152. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15968.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vandewauw I., Owsianik G., Voets T. Systematic and quantitative mRNA expression analysis of TRP channel genes at the single trigeminal and dorsal root ganglion level in mouse. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xing H., Chen M., Ling J., Tan W., Gu J.G. TRPM8 mechanism of cold allodynia after chronic nerve injury. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:13680–13690. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2203-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patil M.J., Ruparel S.B., Henry M.A., Akopian A.N. Prolactin regulates TRPV1, TRPA1, and TRPM8 in sensory neurons in a sex-dependent manner: contribution of prolactin receptor to inflammatory pain. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;305:1154–1164. doi: 10.1152/AJPENDO.00187.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abdulla F.A., Smith P.A. Changes in Na+ channel currents of rat dorsal root ganglion neurons following axotomy and axotomy-induced autotomy. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;88:2518–2529. doi: 10.1152/jn.00913.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sleeper A.A., Cummins T.R., Dib-Hajj S.D., Hormuzdiar W., Tyrrell L., Waxman S.G., Black J.A. Changes in expression of two tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channels and their currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons after sciatic nerve injury but not rhizotomy. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7279–7289. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.20-19-07279.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa K., Tanaka M., Black J.A., Waxman S.G. Changes in expression of voltage-gated potassium channels in dorsal root ganglion neurons following axotomy. Muscle Nerve. 1999;22 doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199904)22:4<502::aid-mus12>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett D.L., Clark A.J., Huang J., Waxman S.G., Dib-Hajj S.D. The role of voltage-gated sodium channels in pain signaling. Physiol. Rev. 2019;99:1079–1151. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00052.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hille B. Sinauer; 2001. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Limón A., Pérez C., Vega R., Soto E. Ca2+-activated K+-current density is correlated with soma size in rat vestibular-afferent neurons in culture. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3751–3761. doi: 10.1152/JN.00177.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Featherstone D.E., Richmond J.E., Ruben P.C. Interaction between fast and slow inactivation in Skml sodium channels. Biophys. J. 1996;71 doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79504-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Richmond J.E., Featherstone D.E., Hartmann H.A., Ruben P.C. Slow inactivation in human cardiac sodium channels. Biophys. J. 1998;74:2945–2952. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)78001-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghovanloo M.-R., Choudhury K., Bandaru T.S., Fouda M.A., Rayani K., Rusinova R., Phaterpekar T., Nelkenbrecher K., Watkins A.R., Poburko D., et al. Cannabidiol inhibits the skeletal muscle nav1.4 by blocking its pore and by altering membrane elasticity. J. Gen. Physiol. 2021;153:e202012701. doi: 10.1085/jgp.202012701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rush A.M., Cummins T.R., Waxman S.G. Multiple sodium channels and their roles in electrogenesis within dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Physiol. 2007;579:1–14. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.121483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramachandra R., McGrew S.Y., Baxter J.C., Howard J.R., Elmslie K.S. NaV1.8 channels are expressed in large, as well as small, diameter sensory afferent neurons. Channels. 2013;7:34–37. doi: 10.4161/CHAN.22445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shields S.D., Ahn H.S., Yang Y., Han C., Seal R.P., Wood J.N., Waxman S.G., Dib-Hajj S.D. Nav1.8 expression is not restricted to nociceptors in mouse peripheral nervous system. Pain. 2012;153:2017–2030. doi: 10.1016/J.PAIN.2012.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fouda M.A., Ghovanloo M.-R., Ruben P.C. Late sodium current: incomplete inactivation triggers seizures, myotonias, arrhythmias, and pain syndromes. J. Physiol. 2022;600:2835–2851. doi: 10.1113/JP282768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dib-Hajj S.D., Cummins T.R., Black J.A., Waxman S.G. Sodium channels in normal and pathological pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;33:325–347. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Armstrong C.M. Na channel inactivation from open and closed states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17991–17996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607603103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vilin Y.Y., Ruben P.C. Slow inactivation in voltage-gated sodium channels: molecular substrates and contributions to channelopathies. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2001;35:171–190. doi: 10.1385/CBB:35:2:171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gawali V.S., Todt H. Mechanism of inactivation in voltage-gated Na+ channels. Curr. Top. Membr. 2016;78:409–450. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctm.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Catterall W.A. Voltage-gated sodium channels at 60: structure, function and pathophysiology. J. Physiol. 2012;590:2577–2589. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clay J.R., Shlesinger M.F. Analysis of the effects of cesium ions on potassium channel currents in biological membranes. J. Theor. Biol. 1984;107:189–201. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ma C., LaMotte R.H. Enhanced excitability of dissociated primary sensory neurons after chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion in the rat. Pain. 2005;113:106–112. doi: 10.1016/J.PAIN.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neher E., Sakmann B. Single-channel currents recorded from membrane of denervated frog muscle fibres. Nature. 1976;260:799–802. doi: 10.1038/260799a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwartz P.J., Ackerman M.J., Antzelevitch C., Bezzina C.R., Borggrefe M., Cuneo B.F., Wilde A.A.M. Inherited cardiac arrhythmias. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020;6:58. doi: 10.1038/S41572-020-0188-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waszkielewicz A.M., Gunia A., Szkaradek N., Słoczyńska K., Krupińska S., Marona H. Ion channels as drug targets in central nervous system disorders. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:1241–1285. doi: 10.2174/0929867311320100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li M., Lester H.A. Ion Channel diseases of the central nervous system. CNS Drug Rev. 2001;7:214–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Waxman S.G. The neuron as a dynamic electrogenic machine: modulation of sodium-channel expression as a basis for functional plasticity in neurons. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2000;355:199–213. doi: 10.1098/RSTB.2000.0559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waxman S.G. Sodium channels, the electrogenisome and the electrogenistat: lessons and questions from the clinic. J. Physiol. 2012;590:2601–2612. doi: 10.1113/JPHYSIOL.2012.228460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Krausz R.M., Westenberg J.N., Ziafat K. The opioid overdose crisis as a global health challenge. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2021;34:405–412. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ghovanloo M.-R., Ruben P.C. Cannabidiol and sodium channel pharmacology: general overview, mechanism, and clinical implications. Neuroscientist. 2022;28:318–334. doi: 10.1177/10738584211017009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghovanloo M.-R., Aimar K., Ghadiry-Tavi R., Yu A., Ruben P.C. Physiology and pathophysiology of sodium channel inactivation. Curr. Top. Membr. 2016;78:479–509. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctm.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Catterall W.A. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dib-Hajj S.D., Rush A.M., Cummins T.R., Hisama F.M., Novella S., Tyrrell L., Marshall L., Waxman S.G. Gain-of-function mutation in Nav1.7 in familial erythromelalgia induces bursting of sensory neurons. Brain. 2005;128:1847–1854. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fertleman C.R., Baker M.D., Parker K.A., Moffatt S., Elmslie F.V., Abrahamsen B., Ostman J., Klugbauer N., Wood J.N., Gardiner R.M., Rees M. SCN9A mutations in paroxysmal extreme pain disorder: allelic variants underlie distinct channel defects and phenotypes. Neuron. 2006;52:767–774. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mis M.A., Yang Y., Tanaka B.S., Gomis-Perez C., Liu S., Dib-Hajj F., Adi T., Garcia-Milian R., Schulman B.R., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Resilience to pain: a peripheral component identified using induced pluripotent stem cells and dynamic clamp. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:382–392. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2433-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yuan J.-H., Estacion M., Mis M.A., Tanaka B.S., Schulman B.R., Chen L., Liu S., Dib-Hajj F.B., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. KCNQ variants and pain modulation: a missense variant in Kv7.3 contributes to pain resilience. Brain Commun. 2021;3:fcab212. doi: 10.1093/BRAINCOMMS/FCAB212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Annecchino L.A., Morris A.R., Copeland C.S., Agabi O.E., Chadderton P., Schultz S.R. Robotic automation of in vivo two-photon targeted whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiology. Neuron. 2017;95:1048–1055.e3. doi: 10.1016/J.NEURON.2017.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kodandaramaiah S.B., Franzesi G.T., Chow B.Y., Boyden E.S., Forest C.R. Automated whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology of neurons in vivo. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:585–587. doi: 10.1038/NMETH.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Annecchino L.A., Schultz S.R. Progress in automating patch clamp cellular physiology. Brain Neurosci. Adv. 2018;2 doi: 10.1177/2398212818776561. 2398212818776561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kolb I., Stoy W.A., Rousseau E.B., Moody O.A., Jenkins A., Forest C.R. Cleaning patch-clamp pipettes for immediate reuse. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:35001. doi: 10.1038/srep35001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kolb I., Landry C.R., Yip M.C., Lewallen C.F., Stoy W.A., Lee J., Felouzis A., Yang B., Boyden E.S., Rozell C.J., Forest C.R. PatcherBot: a single-cell electrophysiology robot for adherent cells and brain slices. J. Neural. Eng. 2019;16:046003. doi: 10.1088/1741-2552/AB1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Perszyk R.E., Yip M.C., McConnell O.L., Wang E.T., Jenkins A., Traynelis S.F., Forest C.R. Automated intracellular pharmacological electrophysiology for ligand-gated ionotropic receptor and pharmacology screening. Mol. Pharmacol. 2021;100:73–82. doi: 10.1124/MOLPHARM.120.000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Thompson K.J., Khajehali E., Bradley S.J., Navarrete J.S., Huang X.P., Slocum S., Jin J., Liu J., Xiong Y., Olsen R.H.J., et al. DREADD Agonist 21 is an effective agonist for muscarinic-based DREADDs in vitro and in vivo. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2018;1:61–72. doi: 10.1021/ACSPTSCI.8B00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All the data published in this paper will be available from the lead contact upon request.

-

•

The Python code is available as supporting information in this manuscript.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.