Abstract

Ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is linked to an increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbations, which significantly increase the risk of mortality in COPD patients. Identifying the subtype of COPD patients who are sensitive to environmental aggressions is necessary. Using in vitro and in vivo PM2.5 exposure models, we demonstrate that exosomal hsa_circ_0005045 is upregulated by PM2.5 and binds to the protein cargo peroxiredoxin2, which functionally aggravates hallmarks of COPD by recruiting neutrophil elastase and triggering in situ release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α by inflammatory cells. The biological function of hsa_circ_0005045 associated with aggravation of COPD is validated using exosome-transplantation and conditional circRNA-knockdown murine models. By sorting the major components of PM2.5, we find that PM2.5-bound heavy metals, which are distinguishable from the components of cigarette smoke, trigger the elevation of exosomal hsa_circ_0005045. Finally, using machine learning models in a cohort with 327 COPD patients, the PM2.5 exposure-sensitive COPD patients are characterized by relatively high hsa_circ_0005045 expression, non-smoking, and group C (mMRC 0–1 (or CAT < 10) and ≥ 2 exacerbations (or ≥ 1 exacerbation leading to hospital admission) in the past year). Thus, our results suggest that environmental reduction in PM2.5 emission provides a targeted approach to protecting non-smoking COPD patients against air pollution-related disease exacerbation.

Keywords: COPD, circRNA, PM2.5, air pollution, machine learning

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which is characterized by chronic inflammatory airway obstruction and emphysema (Vogelmeier et al., 2017), is the third leading cause of death globally (Boehm et al., 2019). A national cross-sectional study suggested that cigarette smoking and ambient fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution are major risk factors for COPD in the Chinese adult population (Wang et al., 2018). Cigarette smoke is the most common irritant of COPD; however, at least one-fourth of COPD cases occur in non-smokers, and their disease is largely attributed to air pollution (Elbarbary et al., 2020; Li et al., 2017). In 2015, the prevalence of spirometry-defined COPD among the Chinese population aged 20 years or older was 6.6% for non-smoking people (without second-hand smoking exposure at home) (Wang et al., 2018). Exposure to an annual mean level of > 50 μg m−3 PM2.5 is associated with a significantly higher prevalence of COPD among never-smokers (Wang et al., 2018). Besides, short-term PM2.5 exposure has been associated with increased hospitalization, emergency department visits, and acute exacerbation in patients with COPD (Atkinson et al., 2014; Li et al., 2016a; Yan et al., 2019). Acute exacerbation is an acute worsening of symptoms leading to loss of lung function in COPD patients (Watz et al., 2018). Researches have shown that even a single exacerbation may significantly increase mortality risk (Suissa et al., 2012). These studies highlight the need for further research on the PM2.5-specific molecular mechanisms to trigger COPD exacerbation and, therefore, predict or prevent the exacerbation (Annesi-Maesano, 2019).

Pulmonary cell-derived exosomes have been reported to serve as biomarkers of COPD progression and to predict the degree of lung injury (Wang et al., 2020b). Exosomes are lipid bilayer extracellular vesicles with diameters < 150 nm. Genschmer et al. reported that exosomes play an unappreciated role in the pathogenesis of COPD (Genschmer et al., 2019); indeed, exosome-bound neutrophil elastase (ELANE) facilitates the degradation of the extracellular matrix and resistance to α1-antitrypsin (α1AT), subsequently causing enlargement of the airspace in lung tissues (Genschmer et al., 2019). In addition to proteins, nucleic acids (mRNA, ncRNAs, and DNA) are common cargo of exosomes and function as mediators of cell-cell communication (Maas et al., 2017). Among them, circular RNAs (circRNAs) have been recognized for their enrichment and stability in exosomes (Wang et al., 2019).

Circular RNAs (CircRNAs), which are covalently closed, single-stranded transcripts produced from precursor mRNA (pre-mRNA) back-splicing (Wang et al., 2020b), have been reported to exhibit tissue-, organ-, and developmental-specific expression (Patop et al., 2019). The expression patterns of circRNAs are involved in the fundamental progression of diseases, such as immune diseases (Chen et al., 2019), tumor development (Guarnerio et al., 2019), brain dysfunction (Piwecka et al., 2017), and respiratory disorders (Huang et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2019). Cytoplasmic circRNAs can be sorted into multivesicular endosomes and then secreted into the plasma within exosomes (Du et al., 2017). Because exosomal circRNAs are enriched and stable in plasma, they represent potential biomarkers of the progression of tissue-specific disease (Chen et al., 2019; Fan et al., 2019). To date, circRNAs have been proposed to act as miRNA sponges and regulate the expression of target genes (Wei et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2018). In addition, circRNAs can interact with proteins, enhance protein function (Huang et al., 2020), and recruit proteins to specific locations (Chen et al., 2018b). Their unique covalently closed-loop structures and distinct tertiary structures determine their protein-binding capacity (Du et al., 2017). Given the small number of molecules within exosomes due to limited physical space, the direct interaction of circRNAs with proteins inside exosomes is more common than the interaction with miRNA sponges.

Acute exacerbation of COPD (aeCOPD) causes hospital admission and is associated with significant mortality and an increased financial burden, whereas identification of aeCOPD remains difficult (Adibi et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2020). Machine learning, including logistic regression (LR), Naïve Bayes (NB), and artificial neural network, has been used to help predict or identify the exacerbation in COPD patients at an early stage (Wang et al., 2020a). Amarala et al. have developed a COPD classifier using machine learning algorithms, which could reach a very accurate clinical diagnosis of COPD (Amaral et al., 2015). We thus hypothesize to construct machine learning models to predict aeCOPD in patients sensitive to PM2.5 pollution.Regarding the importance of COPD exacerbation prediction in response to air pollution, we identified circRNAs in PM2.5-induced COPD with a high risk of exacerbation and examined the potential mechanisms in the current study; We also developed a Naïve Bayes and a decision tree-based model to characterize COPD patients who are sensitive to ambient PM2.5 exposure, which can be a helpful assessment tool to aid COPD patients in taking preventive actions during an acute episode of air pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient characteristics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Southeast University (2016ZDKYSB157). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants at enrollment. In the first cohort, a total of 83 males (mean age: 66 years, range: 57–73 years) and 15 females (mean age: 67 years, range: 62–71 years) in Nanjing, China, were recruited. All patients were retirees living in urban communities and had been diagnosed with stable mild-to-moderate COPD at Nanjing Chest Hospital according to the classification of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Patients who had severe comorbidities or inflammatory diseases were excluded. In Nanjing, the autumn and winter seasons (March-October) show higher air pollution levels than the spring and summer seasons (September-February), with PM2.5 commonly being the primary pollutant (Yang et al., 2018). Therefore, four or five blood collections for each patient were scheduled in September 2016 and March 2017 and were collected between 8:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m. to control for diurnal rhythms. A pair of blood samples was defined as one pre-exposure sample and one post-exposure sample collected from the same individual at 10–14 days over which an air pollution episode had occurred (daily PM2.5 > 75 μg m−3). The levels of pollutants, including PM2.5, PM10, O3 (8 h), NO2, SO2, and CO, were measured by a China national urban air quality real-time publishing platform. Values were converted to air quality index (AQI) levels using the US Environmental Protection Agency standard. Data on individual demographic characteristics (sex, smoke, height, and weight) were collected at enrollment.

In the second cohort, 327 retirees (mean age: 66.91 years, range: 53–79 years, including 271 males and 56 females) in Nanjing were recruited between November 2017 and March 2018. All patients were living in urban communities and had been diagnosed with COPD at Nanjing Chest Hospital according to the classification of GOLD and grouped according to the ABCD group GOLD 2017 as follows: Group A: modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) 0–1 (or COPD Assessment Test (CAT) < 10), and 0–1 exacerbation (not leading to hospital admission) in the past year; Group B: mMRC ≥ 2 (or CAT ≥ 10), and 0–1 exacerbation (not leading to hospital admission) in the past year; Group C: mMRC 0–1 (or CAT < 10) and ≥ 2 exacerbations (or ≥ 1 exacerbation leading to hospital admission) in the past year; Group D: mMRC ≥ 2 (or CAT ≥ 10), and ≥ 2 exacerbations (or ≥ 1 exacerbation leading to hospital admission) in the past year. Peripheral blood samples were collected during the stable stage of COPD. Peripheral blood samples of healthy donors matched with sex, age, and smoking status, enrolled at the Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine, were collected in November 2017 and March 2018. Non-smoking was defined as not having a cigarette for at least one year, and current smoking was defined as having smoked 100 cigarettes in one’s lifetime and currently smoking cigarettes (Wang et al., 2018). This cohort was followed up for two years to survey the acute exacerbations after an episode of PM2.5 pollution. An acute exacerbation of COPD was characterized by a worsening of baseline dyspnea, cough with or without sputum production, or other respiratory symptoms leading to a hospital visit for aeCOPD or a change in medication during an air pollution episode (daily PM2.5 > 75 μg m−3) or within three days after elevated PM2.5 concentration (Annesi-Maesano, 2019; Jung et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2019).

2.2. CircRNA microarray

Eight pairs of blood samples from the first cohort were used for circRNA microarray analysis. The samples were obtained from four men and four women with COPD who experienced an episode of PM2.5 pollution and reported an exacerbation of COPD after the PM2.5 exposure period. Pre-exposure blood samples were obtained between November 7 and 13, 2016, and post-exposure blood samples were obtained between November 13 and 19, 2016. Detailed clinical information from the eight patients with COPD and AQIs across the exposure duration is shown in Tables S9 and S10. Additional Details are provided in supplementary Materials and Methods.

2.3. Proteomics

Exosomes were isolated from blood samples of patients 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, and 8 before and after PM2.5 exposure (Table S9). Proteomics analyses on each sample were performed using the isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) method by CapitalBio Technology Co., Ltd. (China). Exosomal protein was quantified by the BCA method, and 100 μg protein from each sample was lysed with 100 μL lysis buffer composed of 4.5 μL 1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and 4 M urea at 55°C for one h. The protein was precipitated with 660 μL acetone and then digested using 2.5 μg trypsin (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) at 37°C overnight. Peptide samples were labeled with iTRAQ reagent (iTRAQ Mass Tagging Kit) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Tryptic digests of exosomes were separated on an NCS35000 high-performance liquid chromatography instrument (DIONEX, USA) with a 250 mm reverse-phase C18 column. The samples were eluted within 120 min with phase A solution (pure water with 0.1% formic acid) and phase B solution (acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid) at a constant flow rate of 300 nL min−1. A Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) operated in positive ion mode was employed for sample analysis. The mean of the normalized log2 ratio values from all samples was calculated for every protein. A protein was considered significantly changed if it had FC > 1.2 with a P value < 0.05.

2.4. Chemicals

Fine atmospheric particulate matter (PM2.5) (Standard Reference Material 2786) was purchased from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, USA). 9-nitroanthracene (56229), 1-nitropyrene (N-22959), levoglucosan (316555), and PBDE209 (34120) were purchased from Merck, Germany; 2-nitrofluoranthene (FN167487) was purchased from Biosynth Carbosynth, UK, and black carbon particles were purchased from Plasmachem, Germany. According to the manufacturer’s specification, the average primary particle diameter size was 13 nm.

Fine metal particles of aluminum (Al), titanium (Ti), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), iron (Fe), and manganese (Mn) were purchased from Shanghai Naiou Nano Technology Co., Ltd, China. The size distributions of metal particles were evaluated using a zetasizer (nano-zs90, Malvern Instruments, UK). The mean diameters of metal particles were 924.6 ± 43.78 nm (Al), 268.8 ± 24.25 nm (Ti), 270.1 ±26.97 nm (Zn), 742.8 ± 33.55 nm (Cu), 317.0 ± 39.96 nm (Fe) and 777.6 ± 23.23 nm (Mn) as shown in Figure S7. All diameters of metal particles were < 2.5 μm.

2.5. Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (20–22 g, 8-week-old) were purchased from SLRC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (China) and housed in a specific pathogen-free (SPF) animal facility. The efforts were made to ensure humane treatment, and all experimental protocols were approved by the Committee on Animal Use and Care of Southeast University (China) (approval No. 20160622). Mice received standard rodent chow (Jiangsu Xietong Pharmaceutical Bioengineering Co., Ltd., China) sterilized by cobalt (Co) 60 radiation. Five mice were housed in each polycarbonate cage with ad libitum access to food and water, a 12/12-h light/dark cycle, and a room temperature of 22.5°C.

2.6. Animal experiments

Dynamic PM2.5 inhalation exposure chambers have been described previously (Li et al., 2019). Briefly, the chambers were outfitted with extensive air-quality monitoring equipment and an aerosol generator (Beijing HuiRongHe Technology Co., Ltd., China). The concentration of suspended PM2.5 was measured gravimetrically using a real-time dust monitor (CEL-712 Microdust Pro; CASELLA CEL Inc., USA). Exposure was carried out in stainless steel Hinners-type whole-body inhalation chambers; the treatment groups received PM2.5, and the control received high-efficiency particulate air-filtered room air (FRA) at the same flow rate. The mice were exposed in their respective chambers for two h day−1 (9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m.), five days/week (Monday to Friday), with a mean mass concentration of 200 μg m−3 PM2.5, or 50 μg m−3 Mn particles, which led to COPD-like lesions in mice after two-week exposure (data not shown). Additional details are provided in supplementary Materials and Methods.

2.7. Machine learning

In this study, five commonly-used supervised machine learning algorithms, including logistic regression, Naïve Bayes (NB), K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), decision tree (DT), and random forest (RF), were used to predict the potential risks of aeCOPD with different selected features. These five machine learning algorithms have been widely used by investigators for disease prediction, among them, the logistic regression classifier was used as the baseline for comparison. NB is a simple but powerful algorithm based on Bayes’ Theorem, which is quite suitable for solving multi-level prediction problems; KNN is a non-parametric learning algorithm that uses similarity to make a classification based on the distances between a new data point and the points in the training datasets. DT has a hierarchical tree structure, and its branches represent the decision-making process step by step; one of the advantages of DT is that its outputs are easy to read and interpret, especially when we use DT to present the classification of demographic information and other discrete variables, RF is an ensemble learning method which was consisted of multiple decision trees (Uddin et al., 2019). All classifiers were implemented using R package mlr3. Seven selected features (age, sex, smoking status, Group ABCD, FEV1, CAT score, and hsa_circ_0005045 expression) were used to predict the aeCOPD risk. 3-time 10-fold cross-validation technique was used to assess the model performances of the five classifiers; in detail, the whole datasets were randomly divided into ten subsets, then treated nine subsets as the cross-validation training subsets to train the machine learning models, and kept the left one subset as the validation dataset to evaluate the accuracy of the models (Larracy et al., 2021). Finally, the average values of a series of classifier performance indices, including area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (AUC), the sensitivity and specificity of three rounds of 10-fold cross-validation, were calculated based on the confusion matrix of different models.

2.8. Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD) unless indicated otherwise. For comparisons of multiple groups, one- or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used. For comparisons of two groups, pair t-tests or unpaired t-tests were used. The 2−ΔΔCt method was used to analyze the qRT-PCR results. Pearson’s correlation was used to analyze the correlation between hsa_circ_0005045 and PRDX2 or ELANE. The t-test was used to analyze the hsa_circ_0005045 expression levels in the plasma of COPD and healthy controls since the Shapiro-Wilk test (P=0.03) and Kolmogorov- Smirnov test (P=0.78) both proved that the hsa_circ_0005045 expression levels were normally distributed. Results with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 18.0 software. All machine learning analyses were conducted using R version 3.4.3 (www.r-project.org) with R packages mlr3.

Complete details of all reagents and procedures used in this study are provided in Supplemental data.

3. Results

3.1. CircRNA profiles are altered in COPD patients in response to PM2.5 exposure

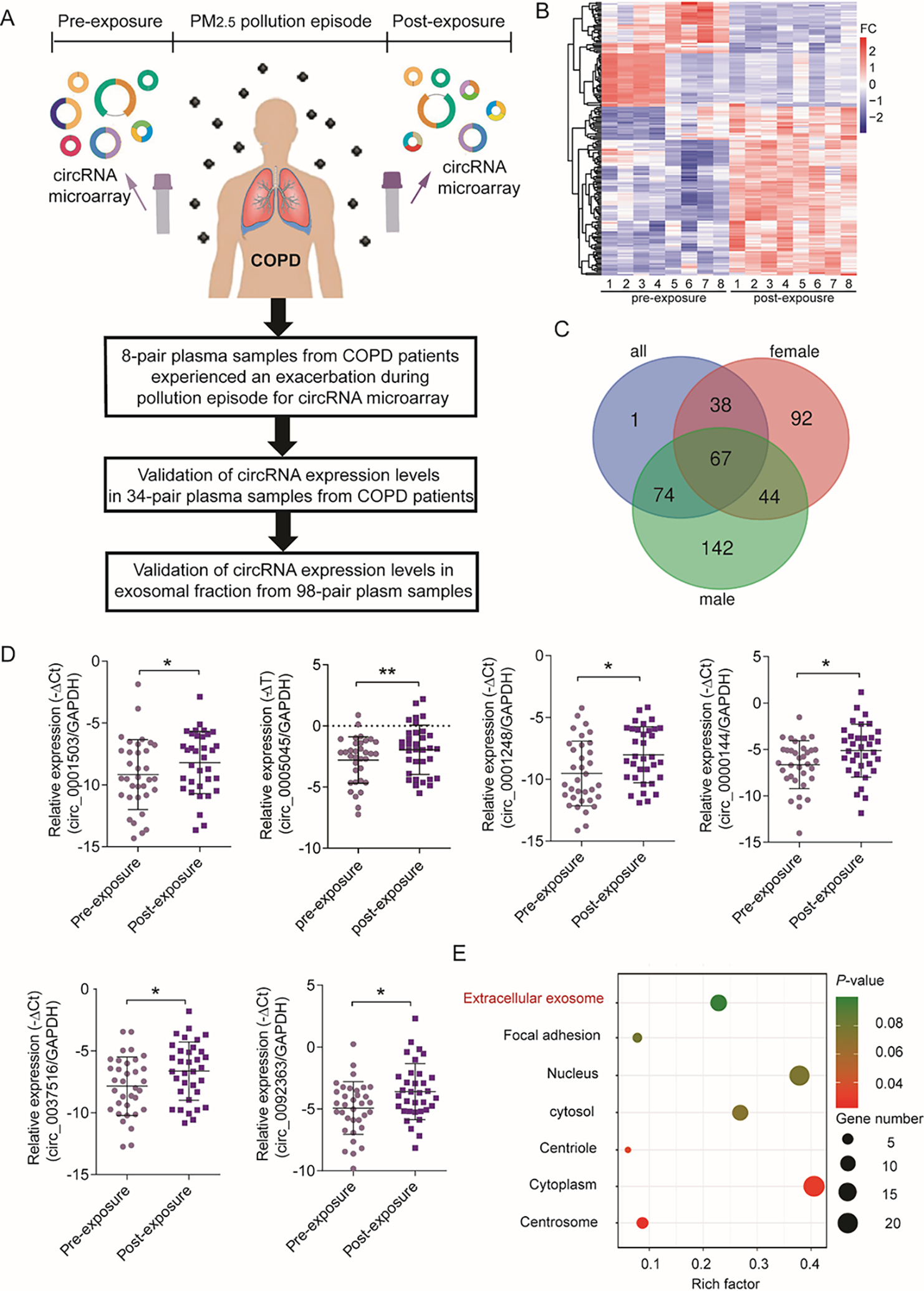

To identify differentially expressed circRNAs in plasma of non-smoking COPD patients who experienced disease exacerbation after an ambient PM2.5 pollution episode, we performed a circRNA microarray analysis of eight pairs of plasma samples pre- and post-exposure (from four men and four women) followed by validation (Figure 1A). As shown in Figure 1B, 111 upregulated circRNAs and 69 downregulated circRNAs were detected in post-exposure plasma compared with pre-PM2.5 exposure plasma, using a cut-off fold change (FC) > 1.5 and P value < 0.05. Further analyses identified 67 circRNAs that overlapped among subgroups composed of the four men, the four women, or all samples (i.e., the four men and four women combined) (Figure 1C). GO analysis suggested the potential enrichment in biological processes (BPs), molecular functions (MFs), and cellular components (CCs) of the pre-mRNAs of these 67 circRNAs (Table S1).

Figure 1. hsa_circ_0005045 is upregulated in the plasma after PM2.5 exposure.

A: The experimental design to identify differentially expressed circRNAs related to PM2.5 exposure. B: Heat map of circRNA expression patterns from microarray analysis of eight patients with COPD. Plasma was collected before and after PM2.5 exposure. C: Venn diagram of differentially expressed circRNAs in males (n=4), females (n=4), and the combination (all, n=8). D: Expression levels of six overlapping circRNAs in plasma samples derived from 34 patients with COPD were evaluated by qRT-PCR (n = 34/group paired t-test). E: Gene ontology enrichment of pre-mRNAs of differentiated expressed circRNAs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Next, we performed qRT-PCR assays to validate the expression levels of the top 16 upregulated overlapping circRNAs in 34 pairs of plasma samples from COPD patients. The expression levels of six circRNAs, including hsa_circ_0001503, hsa_circ_0037516, hsa_circ_0092363, hsa_circ_0000144, hsa_circ_0005045, and hsa_circ_0001248, were significantly upregulated in the plasma after exposure (Figure 1D). Notably, four of the six pre-mRNAs of these circRNAs, i.e., reticulon 4 (RTN4, hsa_circ_0005045), tetratricopeptide repeat domain 38 (TTC38, hsa_circ_0001248), DEAD/H-Box helicase 11 (DDX11, hsa_circ_0092363), and SLAM family member 6 (SLAMF6, hsa_circ_0000144), were associated with the CC “enrichment of extracellular exosomes” (GO: 0070062) (Figure 1E), suggesting a potential association between circRNAs and exosomes.

3.2. Exosomal hsa_circ_0005045 is enhanced in the plasma of COPD patients and interacts with proteins

Exosomes carrying pathogenic substances can promote the transformation of pulmonary disease to COPD (Genschmer et al., 2019). Therefore, we isolated exosomes from plasma samples of COPD patients before and after PM2.5 exposure. Transmission electron microscopy results demonstrate that the exomes were analogous in size (< 100 nm) and appearance (round vesicles) (Figure 2A). The exosomal markers CD63 and Tsg101 were highly expressed in exosome fractions compared with non-exosome fractions in plasma (Figure 2B). Furthermore, expression analysis of the four candidate exosomal circRNAs in 98 paired samples demonstrated that hsa_circ_0005045 was the only significantly upregulated circRNA enriched in exosomes after PM2.5 exposure (Figure 2C and Figure S1). Sanger sequencing and annotation of the sequence confirmed that the qRT-PCR product of hsa_circ_0005045 shared the same sequence as exon 2 of its pre-mRNA, RTN4 and that the back-splicing junction was between G and T (Figure 2D and E).

Figure 2. Proteomics assay of exosomes derived from plasma samples of patients with COPD.

A: Electron micrograph of exosomes derived from plasma samples from patients with COPD pre- and post-exposure to PM2.5 pollution. B: Western blotting of the exosomal markers CD63 and Tsg101 in exosomal and non-exosomal fractions. C: Expression levels of hsa_circ_0005045 in plasma exosomal and non-exosomal fractions from 98 patients with COPD (n = 98/group, paired t-test). D: Sanger sequencing of hsa_circ_0005045 PCR product. E: Schematic diagram showing hsa_circ_0005045 derived from RTN4 and the circularized form from exon 2 of RTN4. F: Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using STRING, an online protein-protein interaction network database (https://string-db.org/). G: RIP assays evaluating the physical binding of hsa_circ_0005045 to PRDX2 and ELANE (n = 3/group, two-way ANOVA). H: The interaction between PRDX2 and ELANE was confirmed by Co-IP assays. I: Expression levels of PRDX2 in plasma samples from patients with COPD, as determined by ELISA (n = 60, paired t-test) and correlation with hsa_circ_0005045 expression in plasma (Pearson analysis, n = 60). J: Expression levels of ELANE in plasma samples from patients with COPD, as determined by ELISA (n = 60, paired t-test), and correlation with hsa_circ_0005045 expression in plasma samples (Pearson analysis, n = 60).*P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

To explore the interactions between circRNA and proteins, we performed proteomics analysis of six pairs of exosomes from plasma of patients with COPD before and after PM2.5 exposure. The results showed that 15 proteins exhibited greater abundance and 20 proteins reduced in abundance in exosomes after PM2.5 exposure compared with the pre-exposure period, with a cut-off of FC > 1.2 and P < 0.05 (Table S2). As shown in Figure 2F, in protein-protein interaction (PPI) network constructed using the online database STRING (https://string-db.org/), peroxiredoxin2 (PRDX2) and neutrophil elastase (ELANE) showed the highest number of nodes among the up-regulated proteins. Therefore, we used the RNA-protein interaction prediction (RPISeq) online tool to predict protein interactions with hsa_circ_0005045, which indicated positive interaction (> 0.05 score) for PRDX2 according to the random forest classifier and for both PRDX2 and ELANE according to the support vector machine classifier (Table S3). RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays indicated that hsa_circ_0005045 interacts with PRDX2 but not ELANE in exosomes (Figure 2G). Moreover, Co-IP assays suggest that PRDX2 and ELANE bind each other (Figure 2H). These results indicate that hsa_circ_0005045 may interact in a complex with PRDX2 and ELANE within exosomes. PRDX2 and ELANE protein levels in the plasma of COPD patients post-exposure compared to pre-exposure to PM2.5 were evaluated. PRDX2 and ELANE showed increased plasma levels with PM2.5 exposure, which were correlated with the levels of hsa_circ_0005045 (Figure 2I and J).

Because pulmonary epithelial cell-derived exosomes are a significant focus in pulmonary exosome biology (Fujita et al., 2015), we further confirmed that expression levels of hsa_circ_0005045 were upregulated in both bronchial and alveolar epithelial cell-derived exosomes after PM2.5 exposure in vitro. (Figure S2).

3.3. Mmu_circ_0002950-enriched exosomes confer a COPD-like phenotype in mice.

To further investigate the function of circRNA in vivo, we established a murine model with COPD-like lesions via dynamic PM2.5 inhalation (Figure S3). According to the NCBI BLAST database, the sequence of the murine circRNA mmu_circ_0002950 is 91% homologous to that of circRNA hsa_circ_0005045, and they are both spliced from the same pre-mRNA RTN4 (Figure 3A), with mmu_circ_0002950 having a back-splicing junction between A and C (Figure 3B). The levels of mmu_circ_0002950 in COPD-like murine BALF and plasma-derived exosomes were consistently and significantly elevated after 7, 14, and 28 days of PM2.5 inhalation (Figure 3C). Furthermore, PRDX2 expression was significantly increased in lung tissues after PM2.5 exposure as evaluated by immunohistochemistry (IHC), with predominant expression in airway epithelial cells (black arrow), alveolar epithelia (red arrow), and infiltrated inflammatory cells (yellow arrow) in the pulmonary parenchyma (Figure 3D), suggesting a potential role in PM2.5 inhalation-associated inflammation.

Figure 3. Inhalation of PM2.5 increases expression levels of mmu_circ_0002950 in murine lungs.

A: Homology analysis in human and mouse genomes was conducted using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and showed that hsa_circ_0005045 and mmu_circ_0002950 are highly conserved. B: Sanger sequencing of the mmu_circ_0002950 PCR product. C: Expression levels of mmu_circ_0002950 in exosomes derived from BALF and plasma of mice (n = 10 [duplicates × five mice/group], two-way ANOVA). D: Representative images of PRDX2 expression in murine lung tissues and IHC scores for PRDX2 (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). PRDX2 expression was mainly expressed in airway epithelial cells (black arrow), alveolar epithelia (red arrow), and infiltrated inflammatory cells (yellow arrow) in the pulmonary parenchyma. E: Schematic of exosome transfer experiment. F: Representative images of H&E staining of murine lungs exposed to exosomes and Lm of alveolar tissue (n = 5/group, t-test). G: Expression levels of mmu_circ_0002950 in the plasma of mice exposed intratracheally to exosomes (n = 10 [5 mice/group × duplicates]/group, t-test). H: Masson’s trichrome staining of murine lungs exposed to exosomes and thickness of the fibrotic layer around small airways (n = 30/group [6 measurements/section × 5 sections/group], t-test). I: Number of cells in the BALF of mice exposed intratracheally to exosomes (n = 5/group, t-test). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To further evaluate the inflammatory status of the mice, we calculated the numbers of inflammatory cells in BALF after PM2.5 exposure. The results demonstrate an increase in total cells, monocytes, and neutrophils after 7, 14, and 28 days of exposure to PM2.5 (Figure S4A). Furthermore, enhanced tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels were significantly increased in the BALF of PM2.5-exposed mice compared with control mice (Figure S4B), which is consistent with a previous report showing that extracellular PRDX2 mediates inflammation by triggering macrophage production and release of TNF-α (Salzano et al., 2014). In acutely injured lungs, ELANE is known to be abnormally secreted by massively recruited polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs) (Boxio et al., 2016). Therefore, we also evaluated ELANE expression by IHC under a high-power field (1000×). ELANE+ cells were observed in the pulmonary parenchyma after PM2.5, and expression was detected in airway epithelial cells (black arrow), alveolar epithelia (red arrow), and infiltrated inflammatory cells (yellow arrow) (Figure S4C and D).

To verify that mmu_circ_0002950-enriched exosomes contribute to COPD-like lesions in mice, we collected exosomes from the BALF of filtered room air (FRA) or PM2.5 inhaled mice and conferred them to healthy recipient mouse airways (Figure 3E). The exosomes isolated from PM2.5-inhaled mice induced hallmarks of COPD (alveolar enlargement) in murine lungs (Figure 3F) and caused an elevation of mmu_circ_0002950 in plasma (Figure 3G). The accumulation of fibrotic tissue around the small airway was slightly but not significantly increased in exosome-treated lungs compared with that in control mice, which could be potentially attributed to the short-term exposure time (7 days; Figure 3H). However, we also observed an elevation of BALF cell counts in mice after exosome administration (Figure 3I), thus confirming that mmu_circ_0002950-enriched exosomes contribute to hallmarks of COPD after PM2.5 exposure.

3.4. Knockdown of mmu_circ_0002950 rescues PM2.5-induced COPD-like lesions in mice

To directly evaluate the role of mmu_circ_0002950 in PM2.5-dependent COPD lesions, we used adeno-associated virus vector (AAV)-6 expressing a short hairpin RNA (shRNA) that targets its backsplicing junction (circ0002950-i) to deplete circ_0002950 in vivo. Mice were treated with FRA or PM2.5, with circ0002950-i or a control AAV (shNC). Intranasal administration of circ0002950-i compared with shNC significantly inhibited the expression of mmu_circ_0002950 in exosomes derived from BALF (Figure 4A) or plasma (Figure 4B) and significantly reduced the numbers of monocytes and neutrophils in murine BALF after PM2.5 inhalation (Figure 4C). Consistent with mmu_circ_0002950, the expression levels of PRDX2, its downstream effector TNF-α, and ELANE were significantly inhibited in the PM2.5/circ0002950-i group compared with PM2.5/shNC (Figure 4D, E, and F). Finally, compared to the PM2.5/shNC group, the hallmarks of COPD, including emphysema and fibrosis deposition, were significantly recovered in the PM2.5/circ0002950-i group (Figure 4G to J). These results suggest that inhibition of mmu_circ_0002950 in murine lungs effectively rescues PM2.5-induced COPD-like lesions in mice.

Figure 4. Suppression of mmu_circ_0002950 rescues COPD-like lesions in murine lungs exposed to PM2.5.

A, B: Effects of AAV6 circ0002950 knockdown (circ0002950-i) on the expression of mmu_circ_0002950 in exosomes derived from the (A) BALF and (B) plasma of mice exposed to PM2.5 (n = 10 [5 mice × duplicates]/group, two-way ANOVA). C: Number of cells in the BALF of mice exposed to PM2.5 with or without circ0002950-i (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). D: IHC staining of PRDX2 in murine lung tissues (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). E: TNF-α levels in the BALF of mice exposed to PM2.5 with or without circ0002950-i (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). F: IHC staining of ELANE in murine lung tissues (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). G: Representative images of H&E staining in murine lung tissues. H: Lm of alveolar tissues (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). I: Masson’s trichrome staining of murine lung tissues. J: Thickness of fibrotic layers around small airways (n = 18/group [6 measurements/section × 3 sections/group], two-way ANOVA). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

3.5. PM2.5-bound manganese is the major component that induces the hsa_circ_0005045 expression

To identify the specific toxic components of PM2.5 that induce hsa_circ_0005045 expression, we compared the major components of PM2.5 (certification of SRM2786) and cigarette smoking, which revealed that PAHs and trace elements are common to both (Figure 5A). Therefore, we treated HBE cells with the components with top mass fractions from nitro-PAH, PBDE congeners, sugars, and trace elements (Table S4). Most of the metal components (Al, Zn, Cu, Fe, and Mn) led to significant increases in hsa_circ_0005045 expression in HBE cells compared to the control within each group. Furthermore, only Mn particles acted in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 5B and Table S5). We performed animal experiments as additional in vivo evidence for the role of Mn particles in inducing hsa_circ_0005045-mediated COPD symptoms. After 14 days of exposure, Mn particles resulted in hallmarks of COPD (emphysema and airway remodeling) in the murine lungs, while circ0002950-i administration effectively protected mice against Mn particle-induced pulmonary lesions (Figure 5C, D and Figure S5). Mechanistically, our results demonstrate that heavy metal-enriched PM2.5 inhalation leads to increased expression and enrichment of hsa_circ_0005045 in exosomes. The physical binding between hsa_circ_0005045 and PRDX2 aggravates COPD lesions in the lung. Furthermore, exosomal hsa_circ_0005045 is transported from the lungs to circulation and is detectable in the plasma after PM2.5 exposure (Figure 5E). Next, it is vital to identify COPD patients sensitive to PM2.5 exposure.

Figure 5. Major toxic components of PM2.5 associated with hsa_circ_0005045 elevation.

A: Venn diagram of major components of PM2.5 and cigarette smoke. B: Expression levels of hsa_circ_0005045 in HBE cells after different components exposure (n=3/group). C: Enlargement of the air space in murine lungs after Mn particle exposure (n = 5/group, two-way ANOVA). D: Deposits of fibrosis around the small airway after Mn particle exposure (n = 30/group [6 measurements/section × 5 sections/group, two-way ANOVA). E: Schematic of involvement of exosomal hsa_circRNA_0005045 in PM2.5 exposure-induced COPD lesion.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

3.6. Prediction of PM2.5 pollution-sensitive COPD patients using machine learning algorithms

To further elucidate the hsa_circ_0005045 expression atlas in COPD patients, we analyzed hsa_circ_0005045 levels in plasma from 327 COPD patients in stable status and healthy controls. The demographic characteristics of the participants and overall expression of hsa_circ_0005045 are shown in Table S6 and S7. Relative to the levels of hsa_circ_0005045 in the plasma of healthy controls, the levels in the plasma of COPD patients were significantly elevated (Figure S6A). Furthermore, among the COPD patients, non-smokers showed considerably higher levels of hsa_circ_0005045 in plasma than smokers (Figure S6B). Within a 2-year follow-up, 102 out of 327 patients had reported experiencing at least once aeCOPD during a PM2.5 pollution episode or within three days after elevated PM2.5 concentration. However, using a single predictor such as smoking, hsa_circ_0005045 levels, COPD assessment test (CAT) score, sex, and age is not strong enough to predict the aeCOPD in response to PM2.5 pollution with AUC values of 0.511, 0.573, 0.479, 0.541, and 0.484, respectively (Figure S6C). Therefore, we further performed five commonly used machine learning algorithms in combination with several nonlinear predictors to characterize the PM2.5 pollution-sensitive COPD patients. As shown in Table S8, all the classifiers have very similar AUC values; however, the sensitivity of Naïve Bayes, K-nearest neighbors Algorithm, decision tree, random forest, and logistic regression were 61%, 50%, 46%, 48%, and 39%, respectively. Based on the comparison of model assessment indices, including the average AUC values in cross-validation training datasets and test subsets, sensitivity, and specificity (Table S8), the performance of Naïve Bayes was superior to other algorithms with robust AUC values (0.7873 and 0.7673) in training and test datasets, the highest sensitivity (0.6186) and specificity (0.8177) among all algorithms. In addition, to better distinguish the more sensitive subgroups and make the results easy to read for researchers and clinical practitioners, we also use a decision tree algorithm to present the classification of aeCOPD following PM2.5 pollution in different subgroups according to key demographic features such as smoking and Group.

Figure 6 presents the results of Naïve Bayes. There were strong correlations between the CAT score and the ABCD group (Figure 6A). The Naive Bayes classifier assumes that all the features contribute to the outcome independently, and using highly correlated variables renders the model instability due to multicollinearity. Then the CAT score was not included in the NB model. The distributions of hsa_circ_0005045 expression between COPD and aeCOPD are shown in Figure 6B. The value for the area under the ROC curve (AUC) was 76.7%; this result is superior to any single regression, as represented in Figure S6C. The scatter plots showed the distribution of cases using a naive bayes classifier with two features in 3-fold cross-validation resampling test sets. Subjects with relatively high circ_0005045 levels among non-smokers (Figure 6C) or in group C (Figure 6D) have higher risks of aeCOPD than other COPD patients; the average prediction accuracies were 0.7431 and 0.7125, respectively.

Figure 6. Prediction of aeCOPD following PM2.5 pollution by machine learning.

A: Correlation between predictor and outcome evaluated using Spearman’s rank coefficient. B: Distribution of circ_0005045 expression in COPD or aeCOPD patients. C: ROC curves derived from Naïve Bayes classifier for segregating aeCOPD from COPD patients. D: Scatter plots representing the distribution of COPD patients according to 2 variables in 3-fold cross-validation resampling test sets using a naive bayes classifier. CV: cross-validation E: Relative importance of variables for segregation of aeCOPD from COPD patient in decision tree algorithm. F: Decision tree algorithm to discriminate COPD patients sensitive to PM2.5 pollution.

Next, we displayed the characteristics of PM2.5-sensitive COPD patients predicted by the decision tree classifier. The relative importance of a variable for segregating aeCOPD in response to PM2.5 pollution was calculated. We identified the top three factors, including hsa_circ_0005045 expression, smoking, and ABCD group, as important predictors for aeCOPD (Figure 6E). High-risk cases (aeCOPD>50%) appeared in two subgroups. Up to 85.7% non-smoking, hsa_circ_0005045 >−3.776 and group C patients, or 63.1% non-smoking, hsa_circ_0005045 >−1.542, group A, B, or D patients experienced aeCOPD during PM2.5 pollution episode (Figure 6F). Taken together, non-smoking, high hsa_circ_0005045 expression, and group C COPD patients are more sensitive to PM2.5 pollution than other patients.

4. Discussion

Plenty of studies have reported associations between PM2.5 pollution and increased COPD exacerbation (Annesi-Maesano, 2019; DeVries et al., 2017). However, characterizing COPD patients who are sensitive to air pollution remains difficult. The rapid advances in omics technology combined with a large-scale evaluation of transcriptomic, proteomic, and mechanism studies permit a novel strategy to identify the biomarkers associated with COPD outcomes(Serban et al., 2021). We currently evaluate the potential role of exosomal circRNAand found that relatively high expression of exosomal hsa_circ_0005045, non-smoking and group C COPD patients were at risk of experiencing acute exacerbation in response to PM2.5 pollution. The induction of exosomal hsa_circ_0005045 aggravated COPD by activating PRDX2/ELANE/TNF-α signaling.

Airway injury from exposure to air pollutants is a significant risk factor in the development of lung diseases. Bronchial and alveolar epithelial cells represent the first line of defense against air pollutants (Fujita et al., 2015). The lung epithelial barrier can become damaged with repeated exposures to toxic substances, such as PM2.5, leading to airway pathology. One of the mechanisms underlying pathogenesis in the airway involves cell-to-cell communication orchestrated by the lung epithelial (Fujita et al., 2015). Exosomes have been extensively reported to play a role in intercellular communication (Sun et al., 2020). Lung cells release exosomes into the extracellular space. These exosomes containing mRNA, non-coding RNA, and proteins are present in BALF (Kaur et al., 2021) and capable of functioning as biomarkers of pulmonary disease (Liu et al., 2022). Furthermore, exosomes containing cargo can enter the circulation and be used as biomarkers for disease diagnosis and therapeutic response (Zhang et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). CircRNAs play multiple roles in developing pulmonary diseases (Chen et al., 2018a; Cheng et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2019b) and have been associated with PM2.5-induced pulmonary disorders (Zhong et al., 2019). Here, we reported the upregulation of exosomal hsa_circ_0005045 (mmu_circ_0002950) as a functional link between PM2.5-driven inflammation and COPD-like lesions. Furthermore, we characterized a novel mechanism through which exosomal hsa_circ_0005045 physically binds to proteins and aggravates the hallmarks of COPD. This reveals a previously overlooked aspect of the interplay between exosomal circRNAs, proteins, inflammation, and COPD-like lesions, suggesting potential applications of molecular markers for evaluating air pollution-induced COPD.

Notably, we observed that hsa_circ_0005045 binds to the exosomal protein PRDX2, a ubiquitous redox-active intracellular enzyme. PRDX2 has been shown to be upregulated in the BALF of patients with COPD (Pastor et al., 2013) and to provide a danger signal, enabling the induction of inflammatory responses (Salzano et al., 2014). Moreover, cells undergoing stress release PRDX2, which mediates inflammation in the mouse brain (Shichita et al., 2012), blood (Bayer et al., 2013), and pulmonary (Federti et al., 2017; Lee, 2020). PRDX2 does not have a signal peptide, suggesting that it is released through nonclassical pathways. Our results indicate that hsa_circ_0005045 facilitates the PRDX2 levels in exosomes, which is likely to provide a pathway for nonclassical cellular circulation. Consistent with this possibility, a recent study reported that PRDX2 is highly expressed in the exosomal fraction but not in the remaining supernatant after exosomes are removed from cultured HEK293 cells and human plasma, suggesting that exosome vehicles are an essential mechanism for the release of circulating PRDX2 (Mullen et al., 2015). Thus, enrichment of PRDX2 associated with the elevated exosomal levels of hsa_circ_0005045 (mmu_circ_0002950) is likely to act as a danger signal in PM2.5-induced COPD. Activation of PRDX2/ELANE/TNF- α signaling associated with increased hsa_circ_0005045 contributes to the aggravated COPD symptoms, which is in line with the mechanism study underlying inflammation is a hallmark in the process of PM2.5 - aggravated COPD (Arias-Perez et al., 2020). As a ubiquitous redox-active intracellular enzyme, the extracellular PRDX2 acts as a redox-dependent inflammatory mediator, triggering macrophages to produce and release TNF-α (Salzano et al., 2014). The oxidative coupling of glutathione (GSH) to PRDX2 cysteine residues occurs before PRDX2 release, a process central to the regulation of immunity. The binding of hsa_circ_0005045 to PRDX2 may affect glutathione formation of PRDX2, thereby increasing the secretion of TNF-α by inflammatory cells. In this study, we identified increased expression of secretory TNF-α in inflammatory cells, which functionally exacerbates the characteristics of COPD. Thus, it is possible that the binding of hsa_circ_0005045 to PRDX2 can modify the redox status of cell surface receptors and induce inflammatory responses. CircrRNAs as biomarkers for diseases have been verified in many lung diseases and have high potential diagnostic and therapeutic value. For example, inhibition of circBbs9 expression can reduce air pollution-induced lung inflammation through NLRP3 activation (Li et al., 2020). circFOXO3 might be a good target for the treatment of inflammatory disorders similar to cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation (Zhou et al., 2021). However, hsa_circ_0005045 is a potential therapeutic target for aeCOPD patients induced by air pollution. Beginning in 2011, the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) began to use ABCD groups to assess the heterogeneity among COPD patients. This system is based on symptoms and the risk of exacerbation in addition to lung function (Boland et al., 2014). The GOLD ABCD groups were modified in 2017 to include measures of symptoms and risk determined only by exacerbation history (Vogelmeier et al., 2017). The 2017 ABCD system acknowledges COPD as a multidimensional disease with various factors determining the disease impact and provides a strategy for individualized care to COPD patients (Criner et al., 2019). Here, we found that group C patients are more sensitive to PM2.5 exposure than those in groups A, B, and D. Dispiting that a cohort study reported 3% of group C among all the COPD patients, the estimated number of group C patients remains large worldwide(Le et al., 2019). According to the 2017 ABCD grading scheme, group C is characterized by a low burden of symptoms but the high risk (2 or more outpatient-treated exacerbations or one or more exacerbations leading to hospital admission). We supposed that environmental triggers, such as PM2.5 pollution, could be a vital risk factor for exacerbation in group C COPD patients.

A substantial reduction of total PM2.5 mass is essential to reduce premature mortality in areas with severe air pollution (Hu et al., 2017); however, total mass reduction requires long-term efforts, and reduction of specific PM2.5 constituent emissions provides an established strategy that might give a more targeted approach to protect susceptible populations (e.g., the successful reduction of Pb emissions by removing Pb-containing additives in gasoline). In the present study, we demonstrated a pathway by which PM2.5 heavy metal components are upstream triggers of COPD exacerbation. Mn has been detected in PM2.5 samples worldwide, showing a high-mass concentration (Li et al., 2016b; Liu et al., 2018; Soleimani et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2016). Notably, PM2.5-bound Mn originates predominantly from ground vehicle emissions (Ventura et al., 2017) and has been identified as resuspended dust (Liu et al., 2018). A recent study has associated Mn-enriched particle exposure with reduced pulmonary function, an important index of COPD (Huang et al., 2019a). Therefore, our results strongly suggest that reducing the concentrations of the key pollutants in the ambient air is likely beneficial to susceptible populations.

In this study, we characterized PM2.5 pollution-sensitive COPD patients with relatively high hsa_circ_0005045 levels among non-smokers and group C, in the combination of using exosomal circRNA profiles, cellular and animal models, a COPD cohort, and machine learning models. Our work will assist in identifying more vulnerable COPD subgroups who are susceptible to ambient PM2.5 exposure and taking proper preventions. However, limitationsshould be metioned. Firstly, a variety of confounding factors such as unhealthy lifestyles except smoking, dietary factors as well as other demographic factors might influence aeCOPD, more features should be collected and included in the aeCOPD prediction model to improve its identifying performance. Moreover, a multi-center study should be done to further verify our findings.

5. Conclusion

In summary, our results found that the subgroup of COPD patients, who are prone to experience an acute exacerbation in response to PM2.5 exposure, are characterized by relatively high hsa_circ_0005045 expression, non-smoking, and group C. Reduction in heavy metal-enriched PM2.5 emission represented potential benefits to protect against air pollution-related COPD exacerbation. It is our understanding that this work will shed light on the possible underlying mechanisms and provide guidance for future government policy-making.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the State Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81730088), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (82025031), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81973084, 82003498, 82003499, 91943301), and Guangdong Provincial Natural Science Foundation Team Project, China (2018B030312005). MA was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) (R01 ES10563, R01 ES07331, and R01 ES020852). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- COPD

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- aeCOPD

Acute exacerbation of COPD

- PM2.5

Particulate matter

- ELANE

Neutrophil elastase, circRNAs, Circular RNAs

- mMRC

Modified Medical Research Council

- RTN4

Reticulon 4

- TTC38

Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 38

- DDX11

DEAD/H-Box helicase 11

- SLAMF6

SLAM family member 6

- PRDX2

Peroxiredoxin2

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Qingtao Meng: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Validation. Jiajia Wang: Methodology, Validation. Jian Cui: Methodology, Validation. Bin Li: Methodology, Validation. Shenshen Wu: Methodology, Validation. Jun Yun: Methodology, Validation. Michael Aschner: Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing, Supervision. Chengshuo Wang: Methodology, Validation. Luo Zhang: Project administration, Supervision. Xiaobo Li: writing original draft, Methodology, Validation, Funding acquisition. Rui Chen: Funding acquisition, Supervision, Project administration.

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or the author.

Supplementary materials and methods, Figure S1–S7, and Table S1 to S12

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an article that has undergone enhancements after acceptance, such as the addition of a cover page and metadata, and formatting for readability, but it is not yet the definitive version of record. This version will undergo additional copyediting, typesetting and review before it is published in its final form, but we are providing this version to give early visibility of the article. Please note that, during the production process, errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability Statement

The circRNA microarray datasets reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE150251).

References

- Adibi A, Sin DD, Safari A, Johnson KM, Aaron SD, FitzGerald JM, and Sadatsafavi M 2020. The Acute COPD Exacerbation Prediction Tool (ACCEPT): a modelling study. Lancet Respir Med 8. 1013–1021. 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30397-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral JL, Lopes AJ, Faria AC, and Melo PL 2015. Machine learning algorithms and forced oscillation measurements to categorise the airway obstruction severity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 118. 186–197. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annesi-Maesano I 2019. Air Pollution and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Exacerbations: When Prevention Becomes Feasible. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 199. 547–548. 10.1164/rccm.201810-1829ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Perez RD, Taborda NA, Gomez DM, Narvaez JF, Porras J, and Hernandez JC 2020. Inflammatory effects of particulate matter air pollution. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 27. 42390–42404. 10.1007/s11356-020-10574-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RW, Kang S, Anderson HR, Mills IC, and Walton HA 2014. Epidemiological time series studies of PM2.5 and daily mortality and hospital admissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 69. 660–665. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-204492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayer SB, Maghzal G, Stocker R, Hampton MB, and Winterbourn CC 2013. Neutrophil-mediated oxidation of erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2 as a potential marker of oxidative stress in inflammation. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 27. 3315–3322. 10.1096/fj.13-227298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm A, Pizzini A, Sonnweber T, Loeffler-Ragg J, Lamina C, Weiss G, and Tancevski I 2019. Assessing global COPD awareness with Google Trends. The European respiratory journal 53. 10.1183/13993003.00351-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland MR, Tsiachristas A, Kruis AL, Chavannes NH, and Rutten-van Molken MP 2014. Are GOLD ABCD groups better associated with health status and costs than GOLD 1234 grades? A cross-sectional study. Primary care respiratory journal : journal of the General Practice Airways Group 23. 30–37. 10.4104/pcrj.2014.00002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxio R, Wartelle J, Nawrocki-Raby B, Lagrange B, Malleret L, Hirche T, Taggart C, Pacheco Y, Devouassoux G, and Bentaher A 2016. Neutrophil elastase cleaves epithelial cadherin in acutely injured lung epithelium. Respiratory research 17. 129. 10.1186/s12931-016-0449-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Ma W, Ke Z, and Xie F 2018a. CircRNA hsa_circ_100395 regulates miR-1228/TCF21 pathway to inhibit lung cancer progression. Cell cycle 17. 2080–2090. 10.1080/15384101.2018.1515553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Zhao G, Yan X, Lv Z, Yin H, Zhang S, Song W, Li X, Li L, Du Z, et al. 2018b. A novel FLI1 exonic circular RNA promotes metastasis in breast cancer by coordinately regulating TET1 and DNMT1. Genome biology 19. 218. 10.1186/s13059-018-1594-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yang T, Wang W, Xi W, Zhang T, Li Q, Yang A, and Wang T 2019. Circular RNAs in immune responses and immune diseases. Theranostics 9. 588–607. 10.7150/thno.29678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Luo W, Li Z, Cao M, Zhu Z, Han C, Dai X, Zhang W, Wang J, Yao H, et al. 2019. CircRNA-012091/PPP1R13B-Mediated Lung Fibrotic Response in Silicosis via ER Stress and Autophagy. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 10.1165/rcmb.2019-0017OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criner RN, Labaki WW, Regan EA, Bon JM, Soler X, Bhatt SP, Murray S, Hokanson JE, Silverman EK, Crapo JD, et al. 2019. Mortality and Exacerbations by Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease Groups ABCD: 2011 Versus 2017 in the COPDGene(R) Cohort. Chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases 6. 64–73. 10.15326/jcopdf.6.1.2018.0130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries R, Kriebel D, and Sama S 2017. Outdoor Air Pollution and COPD-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospital Admissions, and Mortality: A Meta-Analysis. COPD 14. 113–121. 10.1080/15412555.2016.1216956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du WW, Zhang C, Yang W, Yong T, Awan FM, and Yang BB 2017. Identifying and Characterizing circRNA-Protein Interaction. Theranostics 7. 4183–4191. 10.7150/thno.21299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbarbary M, Oganesyan A, Honda T, Kelly P, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Morgan G, Guo Y, and Negin J 2020. Ambient air pollution, lung function and COPD: cross-sectional analysis from the WHO Study of AGEing and adult health wave 1. BMJ Open Respir Res 7. 10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Cao Q, Liu J, Zhang J, and Li B 2019. Circular RNA profiling and its potential for esophageal squamous cell cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Molecular cancer 18. 16. 10.1186/s12943-018-0936-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federti E, Matte A, Ghigo A, Andolfo I, James C, Siciliano A, Leboeuf C, Janin A, Manna F, Choi SY, et al. 2017. Peroxiredoxin-2 plays a pivotal role as multimodal cytoprotector in the early phase of pulmonary hypertension. Free Radic Biol Med 112. 376–386. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita Y, Kosaka N, Araya J, Kuwano K, and Ochiya T 2015. Extracellular vesicles in lung microenvironment and pathogenesis. Trends in molecular medicine 21. 533–542. 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genschmer KR, Russell DW, Lal C, Szul T, Bratcher PE, Noerager BD, Abdul Roda M, Xu X, Rezonzew G, Viera L, et al. 2019. Activated PMN Exosomes: Pathogenic Entities Causing Matrix Destruction and Disease in the Lung. Cell 176. 113–126 e115. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarnerio J, Zhang Y, Cheloni G, Panella R, Mae Katon J, Simpson M, Matsumoto A, Papa A, Loretelli C, Petri A, et al. 2019. Intragenic antagonistic roles of protein and circRNA in tumorigenesis. Cell research 29. 628–640. 10.1038/s41422-019-0192-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Huang L, Chen M, Liao H, Zhang H, Wang S, Zhang Q, and Ying Q 2017. Premature Mortality Attributable to Particulate Matter in China: Source Contributions and Responses to Reductions. Environ Sci Technol 51. 9950–9959. 10.1021/acs.est.7b03193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang A, Zheng H, Wu Z, Chen M, and Huang Y 2020. Circular RNA-protein interactions: functions, mechanisms, and identification. Theranostics 10. 3503–3517. 10.7150/thno.42174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Bao M, Xiao J, Qiu Z, and Wu K 2019a. Effects of PM2.5 on Cardio-Pulmonary Function Injury in Open Manganese Mine Workers. International journal of environmental research and public health 16. 10.3390/ijerph16112017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Cao Y, Zhou M, Qi X, Fu B, Mou Y, Wu G, Xie J, Zhao J, and Xiong W 2019b. Hsa_circ_0005519 increases IL-13/IL-6 by regulating hsa-let-7a-5p in CD4(+) T cells to affect asthma. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology 49. 1116–1127. 10.1111/cea.13445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZK, Yao FY, Xu JQ, Deng Z, Su RG, Peng YP, Luo Q, and Li JM 2018. Microarray Expression Profile of Circular RNAs in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells from Active Tuberculosis Patients. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 45. 1230–1240. 10.1159/000487454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YJ, Kim EJ, Heo JY, Choi YH, Kim DJ, and Ha KH 2022. Short-Term Air Pollution Exposure and Risk of Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Korea: A National Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Study. International journal of environmental research and public health 19. 10.3390/ijerph19052823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur G, Maremanda KP, Campos M, Chand HS, Li F, Hirani N, Haseeb MA, Li D, and Rahman I 2021. Distinct Exosomal miRNA Profiles from BALF and Lung Tissue of COPD and IPF Patients. Int J Mol Sci 22. 10.3390/ijms222111830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larracy R, Phinyomark A, and Scheme E 2021. Machine Learning Model Validation for Early Stage Studies with Small Sample Sizes. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2021. 2314–2319. 10.1109/EMBC46164.2021.9629697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le LAK, Johannessen A, Hardie JA, Johansen OE, Gulsvik A, Vikse BE, and Bakke P 2019. Prevalence and prognostic ability of the GOLD 2017 classification compared to the GOLD 2011 classification in a Norwegian COPD cohort. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 14. 1639–1655. 10.2147/COPD.S194019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ 2020. Knockout Mouse Models for Peroxiredoxins. Antioxidants (Basel) 9. 10.3390/antiox9020182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Sun S, Tang R, Qiu H, Huang Q, Mason TG, and Tian L 2016a. Major air pollutants and risk of COPD exacerbations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 11. 3079–3091. 10.2147/COPD.S122282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Hua Q, Shao Y, Zeng H, Liu Y, Diao Q, Zhang H, Qiu M, Zhu J, Li X, et al. 2020. Circular RNA circBbs9 promotes PM2.5-induced lung inflammation in mice via NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Environ Int 143. 105976. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Cui J, Yang H, Sun H, Lu R, Gao N, Meng Q, Wu S, Wu J, Aschner M, et al. 2019. Colonic Injuries Induced by Inhalational Exposure to Particulate-Matter Air Pollution. Advanced science 6. 1900180. 10.1002/advs.201900180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Yang H, Sun H, Lu R, Zhang C, Gao N, Meng Q, Wu S, Wang S, Aschner M, et al. 2017. Taurine ameliorates particulate matter-induced emphysema by switching on mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114. E9655–E9664. 10.1073/pnas.1712465114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Zhang Z, Liu H, Zhou H, Fan Z, Lin M, Wu D, and Xia B 2016b. Characteristics, sources and health risk assessment of toxic heavy metals in PM2.5 at a megacity of southwest China. Environmental geochemistry and health 38. 353–362. 10.1007/s10653-015-9722-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang L, Li C, Shen Y, Rong H, Jing H, and Tong Z 2020. Long-Term Trends in Hospitalization and Outcomes in Adult Patients with Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Beijing, China, from 2008 to 2017. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 15. 1155–1164. 10.2147/COPD.S238006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Chen Y, Chao S, Cao H, Zhang A, and Yang Y 2018. Emission control priority of PM2.5-bound heavy metals in different seasons: A comprehensive analysis from health risk perspective. The Science of the total environment 644. 20–30. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Yan J, Tong L, Liu S, and Zhang Y 2022. The role of exosomes from BALF in lung disease. J Cell Physiol 237. 161–168. 10.1002/jcp.30553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas SLN, Breakefield XO, and Weaver AM 2017. Extracellular Vesicles: Unique Intercellular Delivery Vehicles. Trends in cell biology 27. 172–188. 10.1016/j.tcb.2016.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen L, Hanschmann EM, Lillig CH, Herzenberg LA, and Ghezzi P 2015. Cysteine Oxidation Targets Peroxiredoxins 1 and 2 for Exosomal Release through a Novel Mechanism of Redox-Dependent Secretion. Molecular medicine 21. 98–108. 10.2119/molmed.2015.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor MD, Nogal A, Molina-Pinelo S, Melendez R, Salinas A, Gonzalez De la Pena M, Martin-Juan J, Corral J, Garcia-Carbonero R, Carnero A, et al. 2013. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with lung cancer and COPD. Journal of proteomics 89. 227–237. 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.04.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patop IL, Wust S, and Kadener S 2019. Past, present, and future of circRNAs. EMBO J 38. e100836. 10.15252/embj.2018100836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piwecka M, Glazar P, Hernandez-Miranda LR, Memczak S, Wolf SA, Rybak-Wolf A, Filipchyk A, Klironomos F, Cerda Jara CA, Fenske P, et al. 2017. Loss of a mammalian circular RNA locus causes miRNA deregulation and affects brain function. Science 357. 10.1126/science.aam8526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzano S, Checconi P, Hanschmann EM, Lillig CH, Bowler LD, Chan P, Vaudry D, Mengozzi M, Coppo L, Sacre S, et al. 2014. Linkage of inflammation and oxidative stress via release of glutathionylated peroxiredoxin-2, which acts as a danger signal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111. 12157–12162. 10.1073/pnas.1401712111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serban KA, Pratte KA, and Bowler RP 2021. Protein Biomarkers for COPD Outcomes. Chest 159. 2244–2253. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shichita T, Hasegawa E, Kimura A, Morita R, Sakaguchi R, Takada I, Sekiya T, Ooboshi H, Kitazono T, Yanagawa T, et al. 2012. Peroxiredoxin family proteins are key initiators of post-ischemic inflammation in the brain. Nature medicine 18. 911–917. 10.1038/nm.2749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soleimani M, Amini N, Sadeghian B, Wang D, and Fang L 2018. Heavy metals and their source identification in particulate matter (PM2.5) in Isfahan City, Iran. Journal of environmental sciences 72. 166–175. 10.1016/j.jes.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suissa S, Dell’Aniello S, and Ernst P 2012. Long-term natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: severe exacerbations and mortality. Thorax 67. 957–963. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Burrola S, Wu J, and Ding WQ 2020. Extracellular Vesicles in the Development of Cancer Therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci 21. 10.3390/ijms21176097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin S, Khan A, Hossain ME, and Moni MA 2019. Comparing different supervised machine learning algorithms for disease prediction. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak19. 281. 10.1186/s12911-019-1004-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura LMB, Mateus VL, and de Almeida ACSL 2017. Chemical composition of fine particles (PM2.5): water-soluble organic fraction and trace metals. Air Quality, Atmosphere and Health 10. 845–852 [Google Scholar]

- Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martinez FJ, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Chen R, Decramer M, Fabbri LM, et al. 2017. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 Report. GOLD Executive Summary. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 195. 557–582. 10.1164/rccm.201701-0218PP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Chen X, Du L, Zhan Q, Yang T, and Fang Z 2020a. Comparison of machine learning algorithms for the identification of acute exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 188. 105267. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.105267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Xu J, Yang L, Xu Y, Zhang X, Bai C, Kang J, Ran P, Shen H, Wen F, et al. 2018. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China Pulmonary Health [CPH] study): a national cross-sectional study. Lancet 391. 1706–1717. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30841-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Wang Q, Du T, Gabriel ANA, Wang X, Sun L, Li X, Xu K, Jiang X, and Zhang Y 2020b. The Potential Roles of Exosomes in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Front Med (Lausanne) 7. 618506. 10.3389/fmed.2020.618506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Liu J, Ma J, Sun T, Zhou Q, Wang W, Wang G, Wu P, Wang H, Jiang L, et al. 2019. Exosomal circRNAs: biogenesis, effect and application in human diseases. Mol Cancer 18. 116. 10.1186/s12943-019-1041-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Magnussen H, Mueller A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Wouters EFM, Vogelmeier C, and Calverley PMA 2018. Spirometric changes during exacerbations of COPD: a post hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Respiratory research 19. 251. 10.1186/s12931-018-0944-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Chen X, Liang C, Ling Y, Yang X, Ye X, Zhang H, Yang P, Cui X, Ren Y, et al. 2019. A Noncoding Regulatory RNAs Network Driven by Circ-CDYL Acts Specifically in the Early Stages Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 10.1002/hep.30795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan P, Liu P, Lin R, Xiao K, Xie S, Wang K, Zhang Y, He X, Zhao S, Zhang X, et al. 2019. Effect of ambient air quality on exacerbation of COPD in patients and its potential mechanism. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease14. 1517–1526. 10.2147/COPD.S190600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Christakos G, Yang X, and He J 2018. Spatiotemporal characterization and mapping of PM2.5 concentrations in southern Jiangsu Province, China. Environmental pollution 234. 794–803. 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.11.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng N, Wang T, Chen M, Yuan Z, Qin J, Wu Y, Gao L, Shen Y, Chen L, and Wen F 2019. Cigarette smoke extract alters genome-wide profiles of circular RNAs and mRNAs in primary human small airway epithelial cells. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 23. 5532–5541. 10.1111/jcmm.14436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X, Xu X, Zheng X, Reponen T, Chen A, and Huo X 2016. Heavy metals in PM2.5 and in blood, and children’s respiratory symptoms and asthma from an e-waste recycling area. Environmental pollution 210. 346–353. 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang N, Nan A, Chen L, Li X, Jia Y, Qiu M, Dai X, Zhou H, Zhu J, Zhang H, et al. 2020. Circular RNA circSATB2 promotes progression of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Mol Cancer 19. 101. 10.1186/s12943-020-01221-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Du L, Bai Y, Han B, He C, Gong L, Huang R, Shen L, Chao J, Liu P, et al. 2018. CircDYM ameliorates depressive-like behavior by targeting miR-9 to regulate microglial activation via HSP90 ubiquitination. Molecular psychiatry. 10.1038/s41380-018-0285-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wang Y, Zhang C, Hu Y, Sun C, Liao J, and Wang G 2019. Identification of long non-coding RNA and circular RNA in mice after intra-tracheal instillation with fine particulate matter. Chemosphere 235. 519–526. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.06.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Wu B, Yang J, Wang B, Pan J, Xu D, and Du C 2021. Knockdown of circFOXO3 ameliorates cigarette smoke-induced lung injury in mice. Respir Res 22. 294. 10.1186/s12931-021-01883-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L, Sun HT, Wang S, Huang SL, Zheng Y, Wang CQ, Hu BY, Qin W, Zou TT, Fu Y, et al. 2020. Isolation and characterization of exosomes for cancer research. J Hematol Oncol 13. 152. 10.1186/s13045-020-00987-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The circRNA microarray datasets reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE150251).