Abstract

Background

The development of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) may be associated with an inflammatory process. Inflammatory cytokines may be a surrogate for systemic inflammation leading to worsening neurological function. We aim to investigate the association between cognitive impairment and inflammation by pooling and analyzing the data from previously published studies.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature search on MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Scopus for prospective longitudinal and cross-sectional studies evaluating the relationship between inflammation and cognitive functions.

Results

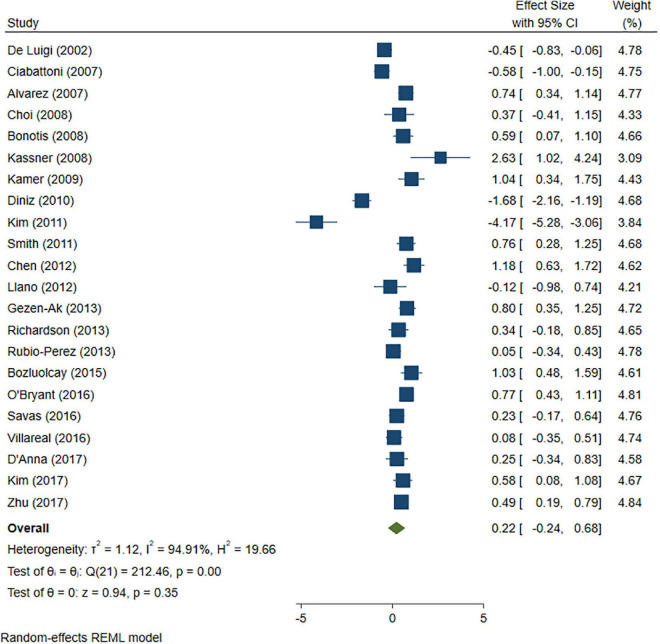

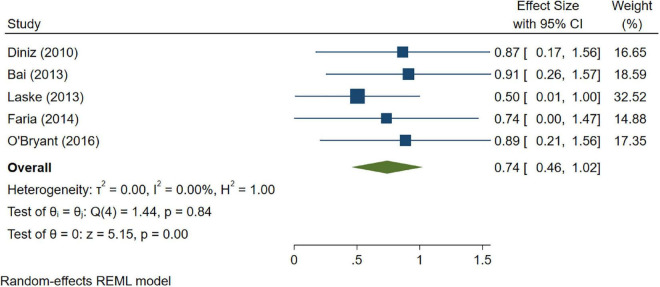

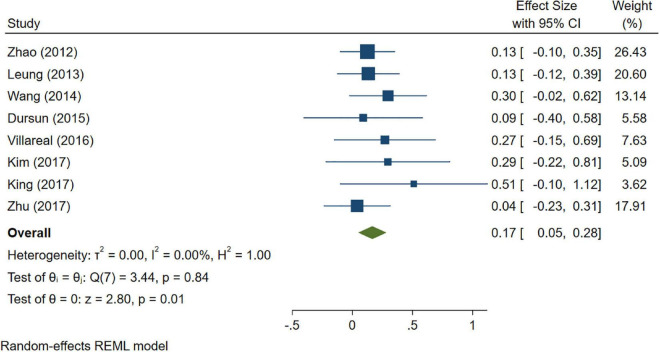

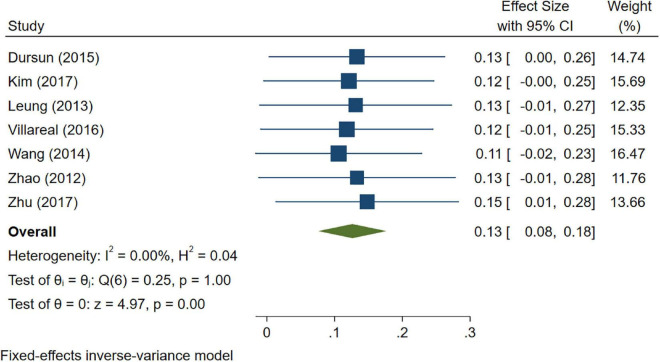

A total of 79 articles were included in our systematic review and meta-analysis. Pooled estimates from cross-sectional studies have demonstrated an increased level of C-reactive protein (CRP) [Hedges’s g 0.35, 95% CI (0.16, 0.55), p < 0.05], IL-1β [0.94, 95% CI (−0.04, 1.92), p < 0.05], interleukin-6 (IL-6) [0.46, 95% CI (0.05, 0.88), p < 0.005], TNF alpha [0.22, 95% CI (−0.24, 0.68), p < 0.05], sTNFR-1 [0.74, 95% CI (0.46, 1.02), p < 0.05] in AD compared to controls. Similarly, higher levels of IL-1β [0.17, 95% CI (0.05, 0.28), p < 0.05], IL-6 [0.13, 95% CI (0.08, 0.18), p < 0.005], TNF alpha [0.28, 95% CI (0.07, 0.49), p < 0.05], sTNFR-1 [0.21, 95% CI (0.05, 0.48), p < 0.05] was also observed in MCI vs. control samples. The data from longitudinal studies suggested that levels of IL-6 significantly increased the risk of cognitive decline [OR = 1.34, 95% CI (1.13, 1.56)]. However, intermediate levels of IL-6 had no significant effect on the final clinical endpoint [OR = 1.06, 95% CI (0.8, 1.32)].

Conclusion

The data from cross-sectional studies suggest a higher level of inflammatory cytokines in AD and MCI as compared to controls. Moreover, data from longitudinal studies suggest that the risk of cognitive deterioration may increase by high IL-6 levels. According to our analysis, CRP, antichymotrypsin (ACT), Albumin, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha may not be good surrogates for neurological degeneration over time.

Keywords: elderly, inflammation, cytokines, CRP, IL-6, cognition

1. Introduction

A variety of cell types can produce cytokines and non-antibody proteins. Interleukins (IL-1–24), tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), and transforming growth factors (TGFs Beta 1–3) are among the approximately 30 cytokines known. Cytokines are proteins that mediate cellular communication by autocrine, paracrine, or endocrine processes. Unique cytokine cell membrane receptors dictate the specificity of the cytokine response. The total response relies on its different components’ synergistic or antagonistic activities. Cytokine actions are the product of a complex network, frequently comprising feedback loops and cascades. The exact activities of different cytokines are hard to identify because of their pleiotropism (Papanicolaou et al., 1998; Wilson et al., 2002). IL-1, IL-6, and TNF are regarded as proinflammatory, but IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 are typically considered anti-inflammatory in the periphery (Kronfol and Remick, 2000). The aging process is associated with a general decrease in immune function. Increasing age has been related to variations in blood levels of different cytokines (Wells et al., 2000). It has been extensively observed that serum IL-6 levels rise with aging in a variety of healthy groups (Wei et al., 1992; Ershler, 1993; Hager et al., 1994; Roubenoff et al., 1998). As a result, increases in IL-6 appear to be the normal outcome of aging, regardless of co-morbidity. Thymic atrophy and inhibition of thymopoiesis during aging may be linked to an increase in IL-6 with age (Sempowski et al., 2000).

It has been hypothesized that Alzheimer’s disease (AD) inflammation is linked and contributes to vascular dementia (Wilson et al., 2002). Central nervous system (CNS) levels of certain cytokines appear to increase as a function of age. Neurologically intact patients show a progressive increase in brain level of IL-1 and microglial activation with age (Sheng et al., 1998). Brain IL-6 levels in the mouse brain have been observed to rise with age, most likely as a result of increasing microglial output (Ye and Johnson, 1999). Cytokines’ impacts on cognition work in two ways, with systemic cytokines signaling the CNS inflammation and the behavioral effects of systemic cytokines producing systemic consequences that eventually negatively influence cognition. The cognitive manifestations of the abovementioned neural degeneration processes arise when acute and chronic excessive cytokine levels exceed a person’s homeostatic threshold, which may be measured by synaptic density or plasticity, and is termed a “cognitive reserve” (Wilson et al., 2002).

Beyond the conventional paradigms of cytokine-induced neurodegeneration and consequent cognitive impairment, processes affecting cognition in its broadest meaning must be investigated. The relationship between increased inflammatory markers in the serum and the occurrence and deterioration of cognitive degenerative diseases is still ambiguous. The correlation between inflammation and cognitive decline has been poorly studied. Older persons with no signs of dementia had higher levels of the inflammatory biomarkers interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP), according to a cross-sectional studies from the Netherlands (Schram et al., 2007) and the US (Yaffe et al., 2003). Consistently contradictory findings may be seen in longitudinal investigations of populations without dementia. Among older Finnish women, a higher CRP level at baseline was associated with worse cognitive performance 12 years later (Komulainen et al., 2007), while a cognitive decline was observed after 2 years in white and black elderly Americans (Yaffe et al., 2003). In white and black Americans, IL-6 predicted the cognitive decline after 2 years (Yaffe et al., 2003), while in Dutch older adults after 5 years (Weaver et al., 2002). Although, there are few systematic reviews and meta-analyses where authors have reviewed the level of biomarkers in cognitive decline (Swardfager et al., 2010; Holmes, 2013) but all of them have considered cross sectional studies only and mostly focused on AD vs. normal comparison in blood samples.

As a result, we aim to systematically review studies comparing cytokine levels between AD and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) vs. healthy controls from the cross-sectional as well as longitudinal studies to test the hypothesis of increased inflammatory levels associated with cognitive decline in this population.

2. Materials and methods

To conduct this systematic review and meta-analysis: we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statements guidelines (Page et al., 2021), as well as the standards of the Cochrane Handbook for systematic review.

2.1. Literature search strategy

We searched the published literature in two electronic databases including MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science and Scopus up to December 2021. Search terms were as follows:

-

(1)

Cognition OR cognitive decline OR cognitive function OR cognitive impairment OR cognitive loss OR memory.

-

(2)

Peripheral OR blood OR plasma OR plasm* OR serum OR sera.

-

(3)

Inflammatory markers OR inflammation OR cytokine OR chemokine OR IFN OR interleukin OR TGF OR TNF OR CRP. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to combine the respective searches. We also manually searched the biography of the included studies for any additional relevant references cited within retrieved articles that were not retrieved during the literature search.

2.2. Eligibility criteria and study selection

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) the study had a cross sectional or longitudinal prospective cohort design; (ii) the cross sectional studies should have reported data of AD, MCI with respect to controls, while in longitudinal studies, cognition performance was used at baseline and follow-up; in (iii) levels of cytokines were measured in blood; (iv) the longitudinal study measured the association of cytokine level and cognitive decline; (v) the article was available in English. Exclusion criteria included: (i) participants with dementia or cognitive impairment were included at baseline; (ii) the association between baseline cytokine level and cognitive decline was not reported; (iii) if the concentration of cytokine markers were measured in post-mortem samples. (iv) Small sample size less than 5 was used.

2.3. Quality assessment

The quality assessment was performed by two authors independently according to the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, and disputes were resolved by discussion. The quality score was calculated based on three major components of cohort studies: quality of selection (zero to four stars), comparability (zero to two stars), and exposure and outcome of study participants (zero to three stars). A higher score represents better methodological quality. Studies were defined as high (greater than seven stars), medium (six to seven stars), or low quality (less than six stars).

2.4. Data extraction

Each type of dataset was extracted independently by two authors. Discrepancies were reconciled through full discussion and consensus among the reviewers. For longitudinal studies, the extracted data involved the following: (I) summary and baseline of patients included in our study including study ID (name of the author, year, and setting of the publication), study design, subjects at baseline, the proportion of females at baseline, mean age at baseline (years), mean follow up assessment of global cognition in months, and the conclusion of each study; (II) risk of bias (ROB) domains including three major components of cohort studies: quality of selection (zero to four stars), comparability (zero to two stars), and exposure and outcome of study participants (zero to three stars); and (III) the outcome measures. The outcome measures were extracted as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the adjusted model, and confounders were adjusted for in the regression analysis. For cross sectional studies, the sample sizes and mean (±SD) concentrations of markers were extracted and Hedge’s g was used for effect size (ES) for meta-analysis.

2.5. Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Open Meta Analyst (AHRQ, CEBM; Brown University, Providence, RI, USA) and STATA version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). We ultimately employed the random-effects model with the DerSimonian and Liard method (DerSimonian and Laird, 1986). From cross sectional studies, the sample sizes and mean (±SD) concentrations of markers were extracted and Hedges’s g was used for ES for meta-analysis. For longitudinal studies, all data were dichotomous (events and no events) and were pooled as weighted proportions and risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CI (Cumpston et al., 2019). Pooled rates of proportions were calculated through the Freeman–Tukey transformation meta-analysis of proportions using MedCalc (Version 15.0; MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Heterogeneity between studies was examined visually and statistically through Chi-square and I2 tests: a Q statistic with P < 0.1 indicated heterogeneity, whereas I2 values of 0, 25, 50, and 75% represented no, low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins et al., 2003). When detecting considerable heterogeneity, we performed sensitivity analyses to ascertain the source of heterogeneity by excluding one study at a time in addition to and subgroup analyses. Publication bias was visually examined through funnel plot symmetry as well as mathematically through Egger’s regression test, Begg’s test, and Duval’s non-parametric trim-and-fill analysis (Begg and Mazumdar, 1994; Irwig et al., 1998; Duval and Tweedie, 2000).

3. Results

3.1. Search results and characteristics of included studies

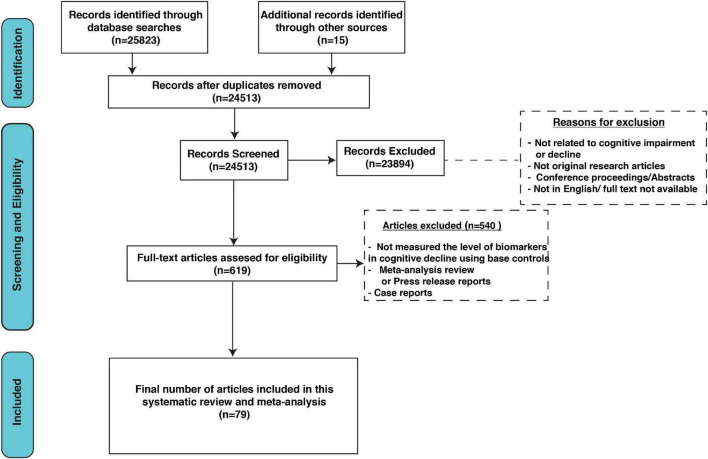

Our search extracted 25,513 unique citations after searching electronic databases. Following title and abstract screening, 619 full-text articles were retrieved and screened for eligibility. Of them, 540 articles were excluded, and 79 studies were reviewed in detail and included in this meta-analysis (PRISMA flow diagram; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

The bibliography of the included randomized control trials (RCTs) was manually searched but added no further records. All studies were conducted between 2002 and 2021. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of included patients and cross-sectional studies, while Table 2 represents longitudinal studies.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of included patients and cross-sectional studies.

| Sr. No | References | Samples | Age (mean ± SD) | Female (%) | Diagnosis | Sample type | Assay type | ||||||

| AD | MCI | CI | AD | MCI | CT | AD | MCI | CT | |||||

| 1 | Teunissen et al., 2003 | 34 | 61 | 73.0 ± 10.0 | 68.0 ± 6.7 | 59 | 43 | DSM-IV; NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA | |||

| 2 | Ciabattoni et al., 2007 | 44 | 44 | 73.0 ± 8.0 | 75.0 ± 7.0 | 56.8 | 61.4 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | ELISA, Bio-Plex cytokine assay | |||

| 3 | Kassner et al., 2008 | 5 | 5 | 75.2 ± 3.5 | 71.0 ± 3.2 | 40 | 40 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA | |||

| 4 | Porcellini et al., 2008 | 195 | 69 | 830 | 79.2 ± 8.3 | 78.0 ± 8.0 | 73.0 ± 6.0 | 69.7 | 53.6 | 54.2 | DSM-IV; NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | ELISA, Immunonephelometry |

| 5 | Davis et al., 2009 | 18 | 51 | NA | NA | NINCDS-ADRDA; DSM-IVR | Serum | Immunoturbidimetric assay | |||||

| 6 | Yarchoan et al., 2013 | 203 | 58 | 117 | 74.5 ± 7.7 | 71.6 ± 8.4 | 69.9 ± 10.1 | 58 | 52 | 68 | NA | Plasma | ELISA |

| 7 | Bozluolcay et al., 2016 | 145 | 25 | 73.2 ± 10.2 | 73.1 ± 10.6 | 50 | 48 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA, Immunonephelometry | |||

| 8 | Villarreal et al., 2016 | 28 | 30 | 77 | 81.9 ± 9.2 | 81.2 ± 7.8 | 76.5 ± 6.7 | 78.6 | 66.7 | 64.9 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Multiplex assay |

| 9 | Dukic et al., 2016 | 70 | 48 | 50 | 74.0 ± 7.6 | 72.0 ± 6.1 | 67.3 ± 7.6 | 61 | 65 | 60 | NINCDS-ADRDA; the Petersen rating criteria | Serum | Complex |

| 10 | King et al., 2018 | 20 | 21 | 20 | 75.9 ± 6.7 | 78.5 ± 6.4 | 75.9 ± 7.3 | 25 | 66.7 | 20 | NINCDS-ADRDA; NIA-AA | Plasma | Mixed |

| 11 | Choi et al., 2008 | 11 | 13 | 73.5 ± 4.0 | 68.5 ± 7.2 | 81.8 | 61.5 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum, CSF | Immunoassay | |||

| 12 | Llano et al., 2012 | 15 | 7 | 70.2 ± 7.4 | 65.0 ± 5.2 | 20 | 28.6 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | MSD | |||

| 13 | Leung et al., 2013 | 117 | 122 | 112 | 76.2 ± 6.1 | 73.9 ± 5.6 | 72.3 ± 6.7 | 66.7 | 49.2 | 53.6 | MMSE; CDR; CERAD; ADAS-Cog | Plasma | Multiplex, ELISA |

| 14 | Rubio-Perez and Morillas-Ruiz, 2013 | 48 | 52 | 76.5 ± 3.5 | 79.0 ± 4.0 | 72.9 | 76.9 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Immunoassay | |||

| 15 | Licastro et al., 2000 | 145 | 51 | 75.0 ± 12.0 | 78.0 ± 14.3 | 62.8 | 60.8 | NINCDS-ADRDA; DSM-III R | Plasma | ELISA | |||

| 16 | De Luigi et al., 2002 | 58 | 47 | NA | NA | NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | ELISA | |||||

| 17 | Zuliani et al., 2007 | 60 | 42 | 78.5 ± 7.6 | 72.3 ± 5.8 | 65 | 46 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | ELISA | |||

| 18 | Forlenza et al., 2009 | 58 | 74 | 21 | 76.3 ± 6.5 | 70.7 ± 10.3 | 69.9 ± 6.7 | 82.8 | 74.3 | 64.5 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA |

| 19 | Kamer et al., 2009 | 18 | 16 | NA | 78 | 94 | DSM-IV; NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | Immunoassay | ||||

| 20 | Richardson et al., 2013 | 24 | 35 | 79.0 ± 6.3 | 75.6 ± 7.6 | 63.8 | 61.8 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA | |||

| 21 | Bozluolcay et al., 2016 | 145 | 25 | 73.2 ± 10.2 | 73.1 ± 10.6 | 50 | 48 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Immunoassay | |||

| 22 | Dursun et al., 2015 | 53 | 30 | 32 | 74.0 ± 3.9 | 74.4 ± 2.9 | 72.1 ± 3.4 | NA | DSM-IV | Serum | ELISA | ||

| 23 | D’Anna et al., 2017 | 27 | 18 | 74.3 ± 8.0 | 70.7 ± 5.0 | 51.9 | 44.4 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Pro human cytokine 10-Plex | |||

| 24 | Zhao et al., 2012 | 150 | 150 | 70.7 ± 4.3 | 69.9 ± 5.2 | 47.3 | 41.3 | Peterson et al’s clinical criteria | Serum | ELISA | |||

| 25 | Wang et al., 2014 | 97 | 54 | 122 | 73.7 ± 9.4 | 76.6 ± 9.1 | 73.7 ± 8.4 | 44.3 | 57.4 | 54.0 | DSM-IV; NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | ELISA |

| 26 | Villarreal et al., 2016 | 28 | 30 | 77 | 81.9 ± 9.2 | 81.2 ± 7.8 | 76.5 ± 6.7 | 78.6 | 66.7 | 64.9 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Multiplex assay |

| 27 | Kim et al., 2017 | 35 | 29 | 28 | 77.7 ± 8.1 | 75.0 ± 7.5 | 72.0 ± 7.3 | 71.4 | 61.5 | 57.1 | NINCDS-ADRDA; IWG criteria | Serum | ELISA |

| 28 | Zhu et al., 2017 | 96 | 140 | 79 | 77.3 ± 7.3 | 71.2 ± 8.1 | 68.3 ± 6.0 | 62.5 | 47.9 | 51.9 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Luminex assays |

| 29 | Bonotis et al., 2008 | 49 | 21 | 75.0 ± 6.0 | 71.2 ± 4.4 | 57.1 | 52.4 | INCDS-ADRDA | Blood | ELISA | |||

| 30 | Bozluolcay et al., 2016 | 145 | 25 | 73.2 ± 10.2 | 73.1 ± 10.6 | 50 | 48 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA, immunoassays | |||

| 31 | Eriksson et al., 2011 | 71 | 205 | 81.6 ± 5.3 | 81.3 ± 5.6 | 73.3 | 62 | NINCDS-ADRDA; DSM-III R, IV | Serum | Immunoassays | |||

| 32 | Kamer et al., 2009 | 18 | 16 | NA | 78 | 94 | DSM-IV; NINCDS-ADRDA | Plasma | Immunoassays | ||||

| 33 | Kong et al., 2002 | 70 | 52 | 71.8 ± 9.7 | 69.0 ± 4.0 | 51.4 | 51.9 | DSM-IV R, MMSE, ADL | Serum | ELISA | |||

| 34 | O’Bryant et al., 2016 | 79 | 65 | 76.1 ± 8.6 | 71.2 ± 9.2 | 70 | 68 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | Multiplex biomarker assay | |||

| 35 | Richartz et al., 2005 | 20 | 21 | 72.0 (60.0–88.0) | 68.0 (59.0–82.0) | 80 | 33 | 3 | NINCDS-ADRDA | Serum | ELISA | ||

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of included patients and longitudinal studies.

| References | Cohort | Setting | Subjects at baseline (n) | Female (%) | Mean age at baseline (years) | Mean follow up (years) | Conclusion |

| Dik et al., 2005 | Longitudinal aging study Amsterdam | The Netherlands | 1,284 | 51 | 75.4 ± 6.6 | 3 | Serum inflammatory protein _1-antichymotrypsin (ACT) is associated with cognitive decline in older persons, whereas C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and albumin are not. |

| Jordanova et al., 2007 | N/A | Britain | 290 | 57 | 65.5 ± 5.5 | 3 | Raised IL-6 but not CRP predicted cognitive decline in this population inflammatory changes associated with cognitive decline may be specific to particular causal pathways. |

| Rafnsson et al., 2007 | Edinburgh artery study | Britain | 452 | 50 | 73.1 ± 5.0 | 4 | Systemic markers of inflammation and hemostasis are associated with a progressive decline in general and specific cognitive abilities in older people, independent of major vascular comorbidity. |

| Schram et al., 2007 (Rotterdam study) | Rotterdam cohort | The Netherlands | 3,874 | 58 | 72.1 ± 6.9 | 4.6 | Systemic markers of inflammation are only moderately associated with cognitive function and decline and tend to be stronger in carriers of the APOE e4 allele. Systemic markers of inflammation are not suitable for risk stratification. |

| Schram et al., 2007 (Leiden 85-plus Study) | Leiden 85-Plus cohort | The Netherlands | 491 | 65 | 85 | 5 | Systemic markers of inflammation are only moderately associated with cognitive function and decline and tend to be stronger in carriers of the APOE e4 allele. Systemic markers of inflammation are not suitable for risk stratification. |

| Singh-Manoux et al., 2014 | The Whitehall II Study | Britain | 5,217 | 28 | 55.7 ± 6.0 | 5 | Elevated IL-6 but not CRP in midlife predicts cognitive decline; the combined cross sectional and longitudinal effects over the 10-year observation period corresponded to an age effect of 3.9 years. |

| Weaver et al., 2002 | The MacArthur study of successful aging | America | 1,189 | 55 | 74.3 ± 2.7 | 7 | There is a relationship between elevated baseline plasma IL-6 and risk for subsequent decline in cognitive function. These findings are consistent with the hypothesized relationship between brain inflammation, as measured here by elevated plasma IL-6, and neuropathologic disorders. |

| Yaffe et al., 2003 | The health ABC study | America | 3,031 | 52 | 73.6 ± 2.9 | 2 | Serum markers of inflammation, especially IL-6 and CRP, are prospectively associated with cognitive decline in well-functioning elders. These findings support the hypothesis that inflammation contributes to cognitive decline in the elderly. |

| Alley et al., 2008 | MacArthur study of successful aging | United States | 533 | 51.8 | 74.4 | 7 | Although high levels of inflammation are associated with incident cognitive impairment, these results do not generalize to the full range of cognitive changes, where the role of inflammation appears to be marginal. |

| Chen et al., 2014 | Prospective, observational, cohort study | China | 109 | NA | 74.1 ± 6.0 | NA | Increased CRP was associated with cognitive impairment, and additive effects of increased CRP with hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia on cognitive impairment were observed among elderly individuals. |

| Tilvis et al., 2004 | Prospective cohort | Finland | 650 | 73 | 75 | 5 | Five-year decline was predicted by the presence of atrial fibrillation [relative risk (RR) 2.8], APOE4 (RR 2.4), elevated CRP (RR 2.3), diabetes mellitus (RR 2.2), and heart failure (RR 1.8). They also tended to increase 5-year all-cause mortality. |

| Adriaensen et al., 2014 | Prospective, observational, cohort study | Belgium | 303 | 37.3 | 84.3 ± 3.4 | NA | Simple serum levels of IL-6 may be very useful in short-term identification or evaluation of global functional status in the oldest old. |

| Ashraf-Ganjouei et al., 2020 | Longitudinal study | Iran | 216 | 36.1 | 39.12 ± 20.19 | NA | Healthy subjects with higher levels of CRP exhibit poorer performance in verbal learning memory and general wakefulness domains of cognition. |

| Baierle et al., 2015 | Prospective cohort | Brazil | 57 | 64.9 | 75 | NA | Individuals with lower antioxidant status are more vulnerable to oxidative stress, which is associated with cognitive function, leading to reduced life quality and expectancy. |

| Beydoun et al., 2018 | Prospective cohort | United States | 2,574 | 55 | 46.9 | 4.64 | Strong associations between systemic inflammation and longitudinal cognitive performance were detected, largely among older individuals (>50 y) and African-Americans. Randomized trials targeting inflammation are warranted. |

| Beydoun et al., 2019 | Prospective cohort | United States | 195 | 65 | 46.90 ± 1.00 | 4.64 | Cytokines were shown to be associated with age-related cognitive decline among middle-aged and older urban adults in an age group and race-specific manner. |

| Boots et al., 2020 | Longitudinal secondary analysis | United States | 86 | 50 | 69.03 ± 6.65 | NA | Peripheral inflammation is inversely associated with select cognitive domains and white matter integrity (but not WMHs), particularly in older Black adults. It is important to consider race when investigating inflammatory associates of brain and behavior. |

| Chi et al., 2017 | Longitudinal study | United States | 1,182 | 45 | 78.9 ± 3.4 | 8 | Inflammation is associated with memory and psychomotor speed. In particular, systemic inflammation, vascular inflammation, and altered endothelial function may play roles in domain-specific cognitive decline of non-demented individuals. |

| Giudici et al., 2019 | Prospective observational study | France | 1,516 | 64.5 | 75.4 ± 4.5 | 5 | Low-grade inflammation and hyperhomocysteinemia were both related with impairment on the combined IC levels among older adults after a 5-year follow-up. Identifying biomarkers that strongly associate with IC may help to settle strategies aiming to prevent the incidence and slow down the evolution of age-related functional decline and care dependency. |

| Goldstein et al., 2015 | Longitudinal study | United States | 278 | 63.7 | 57.4 ± 5.4 | NA | There is strong association between IL-8 and cognitive performance in African Americans than Caucasians. This relationship should be further examined in larger samples that are followed over time. |

| Gunathilake et al., 2016 | Longitudinal study | Australia | 3,293 | 53 | 66.8 ± 7.8 | NA | There is a weak positive association between obesity and cognitive performance in older persons, which is partially antagonized by inflammation and elevated fasting plasma glucose, but not hypertriglyceridemia. |

| Hajjar et al., 2018 | Longitudinal cohort study | United States | 511 | 68 | 49.1 | 4 | Increased oxidative stress reflected by decreased glutathione was associated with a decline in executive function in a healthy population. In contrast, inflammation was not linked to cognitive decline. Oxidative stress may be an earlier biomarker that precedes the inflammatory phase of executive decline with aging. |

| Jung et al., 2019 | Longitudinal cohort study | Republic of Korea | 70 | 44.2 | 25.68 ± 3.89 | NA | Cytokines, stress, and emotional and cognitive intelligence are closely connected one another related to brain structure and functions. Also, the pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and IL-6 had negative effects, whereas the anti-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., IL-10 and interferon (IFN)-gamma] showed beneficial effects, on stress levels, and multiple dimensions of emotional and cognitive intelligence. |

| Komulainen et al., 2007 | Longitudinal cohort study | Finland | 97 | 100 | 63.8 | 12 | High serum hs-CRP concentration predicts poorer memory 12 years later in elderly women. Hs-CRP may be a useful biomarker to identify individuals at an increased risk for cognitive decline. |

| Marioni et al., 2009 | Longitudinal cohort study | United Kingdom | 3,350 | 72 | 61.9 ± 6.7 | 5 | Increased circulating levels of CRP, fibrinogen, and elevated plasma viscosity predicted poorer subsequent cognitive ability and were associated with age-related cognitive decline in several domains, including general ability. |

| McHugh Power et al., 2019 | Longitudinal cohort study | United Kingdom | 116 | 66 | 65.81 ± 6.63 | 2 | Inflammatory markers, cognitive function, social support, and psychosocial wellbeing were evaluated. A structural equation modelling approach was used to analyse the data. The model was a good fit (_108 2 = 256.13, p < 0.001). |

| Mooijaart et al., 2011 | Prospective observational study | Scotland, Ireland, and the Netherlands | 5,680 | 52 | 75.3 | 3.2 | Plasma CRP concentrations associate with cognitive performance in part through pathways independent of cardiovascular disease. However, lifelong exposure to higher CRP levels does not associate with poorer cognitive performance in old age. |

| Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2006 | Longitudinal cohort study | Mexico | 189 | 75 | 66.8 | NA | The elderly in urban areas have more oxidative stress and a higher risk of developing confidence interval (CI) compared with elderly individuals in a rural environment. |

| Sasayama et al., 2012 | Longitudinal cohort study | Japan | 576 | 75 | 45.1 ± 15.0 | NA | Elevated IL-6 and soluble IL-6R levels in Ala carriers may have negative impact on acquiring verbal cognitive ability requiring long-term memory. |

| Sharma et al., 2016 | Longitudinal case-cohort study | United States | 1,298 | 45 | 79.0 ± 3.4 | 6 | This study did not find strong evidence of the utility of the biomarkers evaluated for identifying individuals at risk of cognitive decline. |

| Shi et al., 2020 | Prospective observational study | China | 372 | 31.5 | 60.58 ± 7.86 | 2 | IL-35 polymorphisms were not associated with cognitive decline in CHD patients over a 2-year period yet. |

| Sochocka et al., 2017 | Longitudinal case-cohort study | Poland | 128 | 64.8 | 55–90 | NA | The comorbidity of the periodontal health status may deepen the cognitive impairment and neurodegenerative lesions and advance to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). |

| Yang et al., 2020 | Longitudinal cohort study | China | 122 | 49.18 | NA | NA | T2DM patients have more cognitive impairment than T1DM patients. Changes in brain function connections and metabolites may be the structural basis of the differences in cognitive functional impairment. Inflammation is related to cognitive impairment in diabetes patients, especially in T2DM patients. |

| Yirmiya et al., 2020 | Longitudinal cohort study | Israel | 33 | 60.6 | NA | NA | Sleep impairments in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, which might negatively affect their cognitive functioning, and corroborate a potential role of immunological pathways in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome neuro-phenotype. |

| Zheng et al., 2019 | Case-control study | China | 126 | 50 | 74.06 | NA | Serum IL-6 and hs-CRP were associated with the risk of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in Chinese patients with T2D. Serum folate might modify the association between serum hs-CRP and MCI in T2D patients. |

3.2. The potential sources of bias

Following the Newcastle Ottawa Scale, the quality of the included studies ranged from moderate to high. The main concern was absent control groups. A summary of quality assessment domains with authors’ judgments is attached. Funnel plots of the inverse of the standard error vs. the ES demonstrated asymmetry. However, Egger’s test (P = 0.08) and Begg’s test (P = 0.13) indicated no small-study effects. Also, we employed the trim-and-fill approach to verify the robustness of the results, which exhibited no significant changes to the results when imputing three missing studies.

3.3. Comparisons between AD/control and MCI/control cross-sectional studies

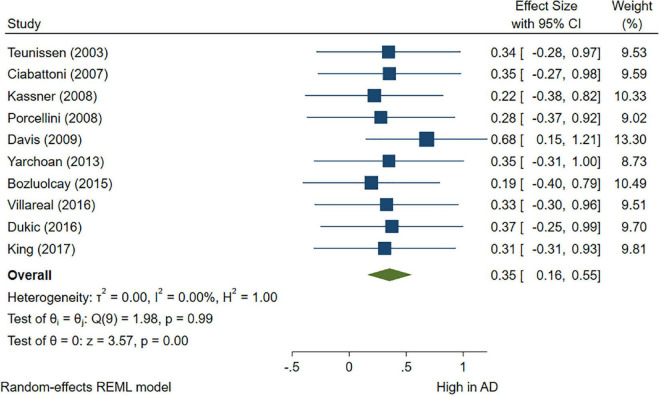

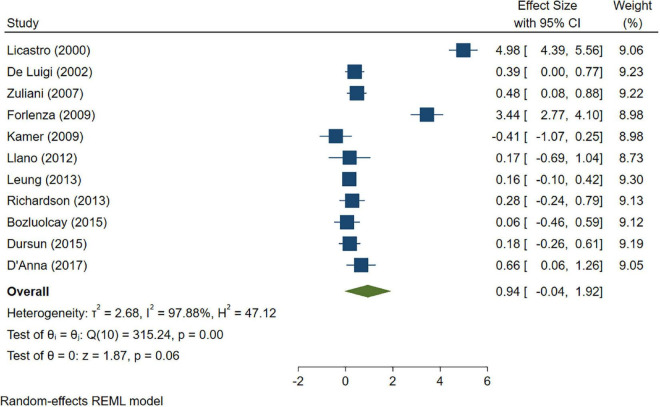

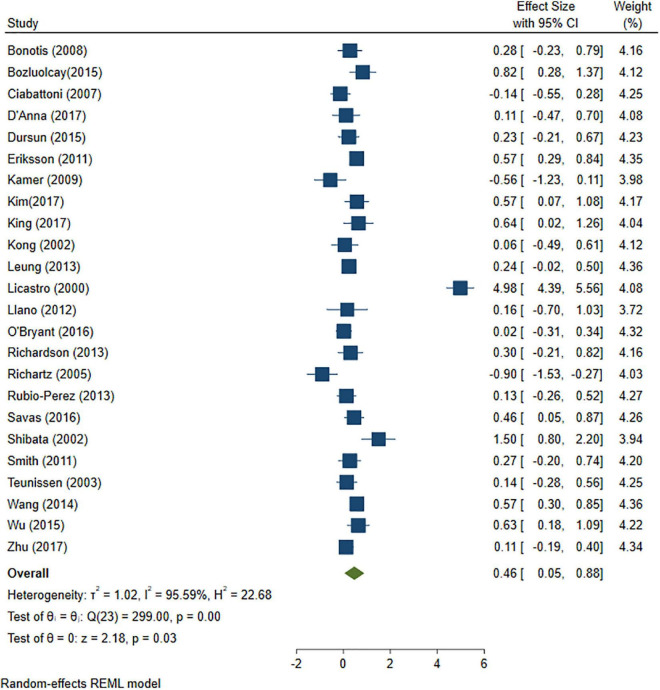

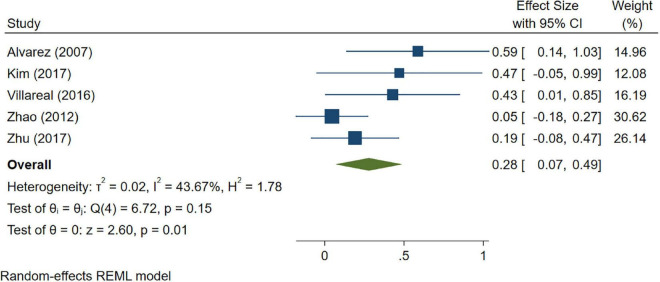

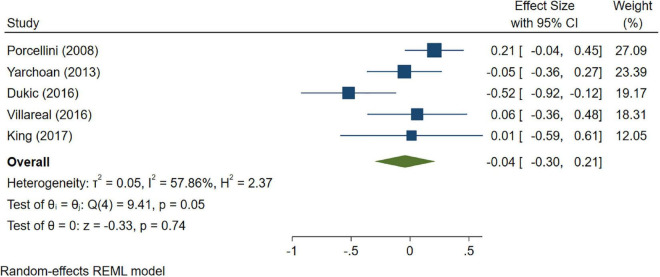

A total of 46 studies were included in this analysis. Cross-sectional studies have demonstrated an increased level of CRP (Hedges’s g 0.35, p < 0.05) (Figure 2), IL-1β (0.94, p < 0.05) (Figure 3), IL-6 (0.46, p < 0.005) (Figure 4), TNF alpha (0.22, p < 0.05) (Figure 5), and sTNFR-1 (0.74, p < 0.05) (Figure 6) in AD compared to controls. Similarly, higher levels of IL-1β (0.17, p < 0.05) (Figure 7), IL-6 (0.13, p < 0.005) (Figure 8), TNF alpha (0.28, p < 0.05) (Figure 9), and CRP (0.21, p < 0.05) (Figure 10) was also observed in MCI vs. control samples.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high IL-1β concentration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high IL-6 concentration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha concentration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high sTNFR-1 concentration in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high IL-1β concentration in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high IL-6 concentration in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha concentration in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) samples compared to controls.

FIGURE 10.

Forest plot of pooled Hedge’s g depicting high C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration in mild cognitive impairment (MCI) samples compared to controls.

3.4. Outcomes from longitudinal studies

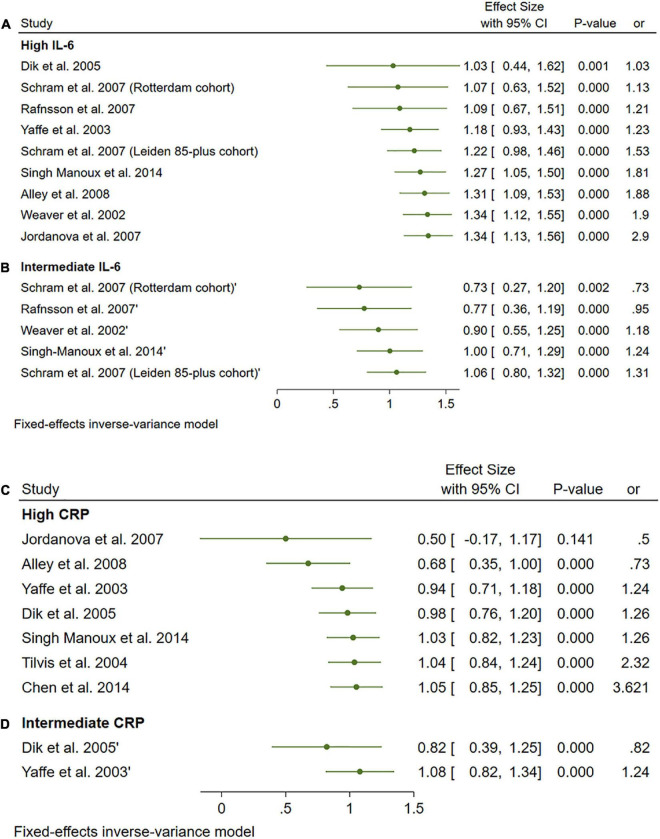

3.4.1. IL-6

A total of 33 studies were included in this analysis and they followed subjects for an average of 58.35 months (min. 24 months and max. 144 months). High levels (>3.1 pg/ml) of IL-6 significantly increased the risk of cognitive decline [OR = 1.34, 95% CI (1.13, 1.56)]. However, intermediate levels (1.6–3.1 pg/ml) of IL-6 had no significant effect on the final endpoint [OR = 1.06, 95% CI (0.8, 1.32)]. The pooled analysis was homogeneous (I2 = 0%, p = 0.5) (Figures 11A, B).

FIGURE 11.

(A) Forest plot of pooled odds ratio (OR) for interleukin-6 (IL-6) high concentration and cognitive decline. (B) Forest plot of pooled odds ratio (OR) for IL-6 intermediate concentration and cognitive decline. (C) Forest plot of pooled odds ratio (OR) for C-reactive protein (CRP) high concentration and cognitive decline. (D) Forest plot of pooled odds ratio (OR) for CRP intermediate concentration and cognitive decline.

3.4.2. CRP

Interestingly, high and intermediate levels of CRP showed no significant impact on cognitive decline [OR = 1.08, 95% CI (0.74, 1.42)] and [OR = 1.05, 95% CI (0.64, 1.46)], respectively. The pooled analysis was moderately heterogeneous (I2 = 52.56%, p = 0.05), and heterogeneity did not resolve after further sensitivity analysis; thus, the random effect model was employed (Figures 11C, D).

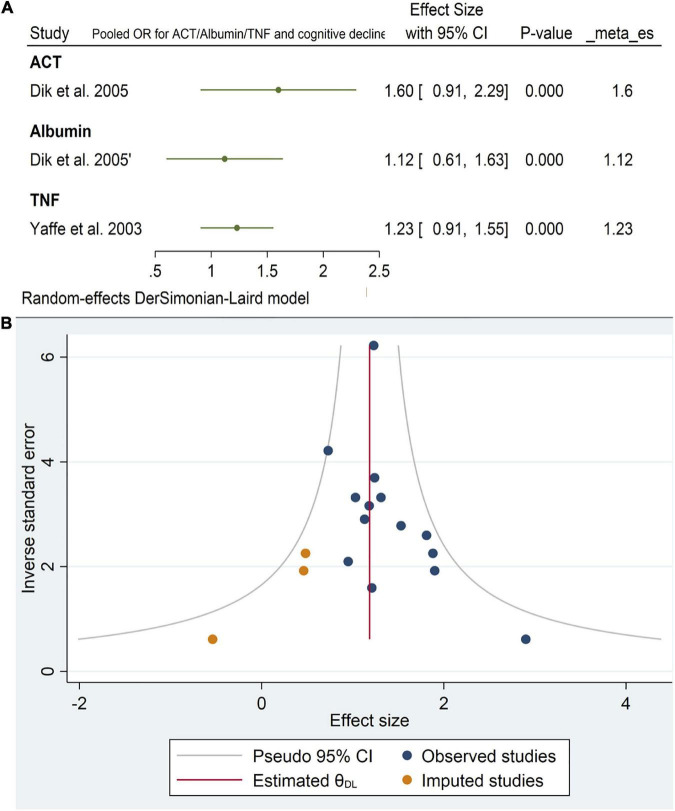

3.4.3. ACT, Albumin, and TNF

Only two studies reported the effects of alpha1-antichymotrypsin (ACT), Albumin, and TNF alpha on cognitive outcomes. Neither ACT [OR = 1.6, 95% CI (0.9, 2.29)] Albumin [OR = 1.12, 95% CI (0.61, 1.63)] nor TNF [OR = 1.23, 95% CI (0.91, 1.55)] had a statistically significant effect on cognitive impairment. The pooled analysis was homogeneous (I2 = 0%, p = 0.5) (Figure 12A). Funnel plots of the inverse of the standard error vs. the ES demonstrated asymmetry (Figure 12B). However, Egger’s test (P = 0.08) and Begg’s test (P = 0.13) indicated no small-study effects.

FIGURE 12.

(A) Forest plot of pooled odds ratio (OR) for antichymotrypsin (ACT), albumin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and cognitive decline. (B) Funnel plot for the included longitudinal studies for interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels (intermediate and high).

4. Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we have compiled and analyzed the varied results from individual studies that looked at the relationship between AD and MCI and inflammatory markers in peripheral blood or cerebrospinal fluid. Different levels of inflammatory markers were found to be significantly different across the AD, MCI, and control groups. A total of 79 articles were included in our systematic review and meta-analysis which include cross-sectional and longitudinal cohort studies and case-control. Cross-sectional studies demonstrated several changes in the inflammatory marker levels in the comparisons between AD, MCI, and control groups.

Notably, IL-6 level was found to be significantly increased in patients with AD compared with controls and MCI vs. controls. This meta-analysis confirmed the elevated levels of interleukin family molecules including as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8 in AD patients. These cytokines and chemokines connect with the existence and breakdown of amyloid-beta (Aβ) or tau proteins, which contribute to neurodegeneration pathways in AD (Teixeira et al., 2008). Specifically, IL-6 was revealed to have a potential characteristic that identifies the extent of cognitive decline in AD patients. Deposition of Aβ has been demonstrated to stimulate IL-6 production by microglia and astrocytes, which may speed the progression of AD’s degenerative cascade (Uslu et al., 2012). There are many common cytokines whose level were detected in AD and MCI conditions including CRP, IL1β, TNFα, IL6, and sTNFR1. However, their overall level was less in MCI compared to AD which suggest them as markers of neuroinflammation in AD and there may be an association between raised levels of cytokines in the blood and the development of AD.

4.1. Impact of systemic inflammation on cognitive performance

One hypothesis to explain the effects of increased cytokines in MCI and AD as compared to healthy controls is the impact of systemic inflammation on brain plasticity and function. Systemic inflammation raises pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-, and CRP, which may interact with the CNS in three ways: (1) pro-inflammatory cytokine transport proteins facilitate active trafficking across the blood brain barrier (BBB) for central activity (Dantzer et al., 2008; Fung et al., 2012). (2) Systemically generated cytokines may excite afferent nerves (e.g., the vagal nerve), which send inflammation to the brain stem. Vagal nerve projects to the solitary tract nucleus and higher brain areas (McCusker and Kelley, 2013). (3) Circulating cytokines reach outside-BBB organs. There, cells expressing toll-like receptors react to the increased inflammation by releasing pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may reach the brain by volume diffusion (Vitkovic et al., 2000b; McCusker and Kelley, 2013; Sankowski et al., 2015). When triggered peripherally, these three routes activate brain microglia and astrocytes to create pro-inflammatory cytokines, spreading the signal into the neuronal environment (Dantzer et al., 2008; Sankowski et al., 2015).

The blood-brain barrier, often known as the BBB, is an important component in both the preservation of the CNS’s highly specialized milieu and the facilitation of communication with the systemic compartment. Alterations to the BBB may be seen in a variety of CNS diseases, including AD. Some non-disruptive BBB alterations are mediated directly by cytokines (Ericsson et al., 1995). The cerebral endothelium expresses several cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF- receptors. Activation of the endothelium is caused by IL-1 before that of neighboring brain regions, which suggests that activation of the BBB is an intermediary stage (Herkenham et al., 1998). It is interesting to note that IFN- decreases the transmigration of type 1 T helper lymphocytes without having any effect on the diffusibility of albumin. This suggests that the effect is not caused by a change in the tight junctions but rather by cytokine-induced non-disruptive changes that discourage neuroinflammation (Prat et al., 2005).

Systemic inflammation is also known to play an important role in altering the hormonal levels. There are a number of cytokines, including TNF-alpha, interleukin-1 beta (IL-1 beta), and IL-6 that work as feedback loops to inhibit the immunological response when the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is stimulated by the stress of trauma or exercise (Brenner et al., 1997; Licinio and Wong, 1997; Teblick et al., 2019). However, persistent increase of cytokines might potentially inhibit the HPA axis, which can lead to decreased levels of glucocorticoids, growth hormone, and adrenocorticotropic hormone (Teblick et al., 2019).

4.2. Increased cytokine levels as a marker of central nervous system inflammation

Preclinical and clinical research have demonstrated that infection-related peripheral inflammation contributes to the development and progression of CNS disorders such AD, personality disorders (PD), Multiple Sclerosis (MS), and stroke. Patients with AD have increased levels of Aβ in their brains due to peripheral inflammation (Le Page et al., 2018). In amyloid precursor protein (APP) transgenic mice, peripheral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection enhanced BBB permeability, enabling proinflammatory factors such as IL-6 and TNF- to infiltrate the brain and promote disease development (Jaeger et al., 2009; Takeda et al., 2013). The increased level of cytokines in included studies suggests that patients might have CNS inflammation.

4.3. Longitudinal studies and risk of IL-6

Results from longitudinal studies also showed high levels of IL-6 significantly increased the risk of cognitive decline. However, intermediate levels of IL-6 had no significant effect on the final endpoint. Likewise, neither CRP, ACT, Albumin, or TNF alpha showed a significant impact on cognitive decline.

The neuronal and glial cell function is modulated by a highly controlled network of cytokines and soluble cytokine receptors (Benveniste, 1998; Vitkovic et al., 2000a). This is related to their capacity to modulate neurotransmission. Increases in noradrenergic, dopaminergic, and serotonergic metabolism in the hypothalamus, hippocampus, and nucleus accumbens can be caused by both systemic and central cytokine administration (Mohankumar et al., 1991; Shintani et al., 1993; Linthorst et al., 1995; Merali et al., 1997). IFN- stimulates neuronal differentiation, while IL-1, IL-6, and TNF- have trophic effects on developing neurons and glia (Jonakait, 1997; Zhao and Schwartz, 1998). In the developing brain, IL-1 may also play a role in regulating the synaptic plasticity that underpins learning and memory (Zhao and Schwartz, 1998).

Jordanova et al. (2007), Singh-Manoux et al. (2014) reported that raised IL-6 but not CRP predicted cognitive decline in this population. Inflammatory changes associated with cognitive decline may be specific to particular causal pathways which is consistent with our findings. Weaver et al. (2002), Sasayama et al. (2012), Adriaensen et al. (2014) found a strong association between the level of IL-6 and short-term identification or evaluation of global functional status in the old. They reported that elevated IL-6 and soluble IL-6R levels in Ala carriers may have a negative impact on acquiring verbal cognitive ability requiring long-term memory. Mooijaart et al. (2011) found that plasma CRP concentrations associate with cognitive performance in part through pathways independent of cardiovascular disease. However, lifelong exposure to higher CRP levels does not associate with poorer cognitive performance in old age.

On the other hand, Yaffe et al. (2003), Chen et al. (2014) documented an association between CRP elevation and cognitive impairment which is inconsistent with our meta results. This may be because of the limited number of participants in these studies compared to our meta-analysis. Ashraf-Ganjouei et al. (2020) found that healthy subjects with higher levels of CRP exhibit poorer performance in verbal learning memory and general wakefulness domains of cognition.

Some other interleukins have a role in cognitive impairment other than IL-6. Goldstein et al. (2015) recorded strong relation between IL-8 and cognitive performance in African Americans than Caucasians. However, this relationship should be further examined in larger samples that are followed over time. Conversely, Shi et al. (2020) reported IL-35 polymorphisms were not associated with cognitive decline in coronary heart disease patients over 2 years.

Shen et al. (2019) reported that inflammatory marker levels were found to be significantly different in AD and control groups, supporting the idea that AD is accompanied by inflammatory responses in the peripheral and cerebro spinal fluid (CSF). In a previous review, Wilson et al. (2002) reported that cytokine-mediated inflammation in neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and vascular dementia is increasingly appreciated. Cytokines are an important part of stress activation in the hypothalamic-hypo physiologic-adrenal axis.

Our study is the first meta-analysis to our knowledge to differentiate between several inflammatory cytokines and their relation individually to cognitive impairment. In spite of the large sample size of our study and the strength of meta-analysis, these results are limited by the study design of included studies and the insufficient data about other inflammatory markers other than IL-6. Only two studies reported the effects of ACT, Albumin, and TNF alpha on cognitive outcomes. We need more controlled studies that have the least confounders to assure the strength of results.

4.4. Future perspectives: Inflammatory markers as a novel therapeutic target for AD

Although this meta-analysis only provides additional evidence for the association between some inflammatory markers and cognitive decline, it is worthwhile to discuss the potential impact for the development of novel treatments for AD. There has been an important debate on the current therapeutic target for AD, the amyloid β-protein. However, studies have not demonstrated that anti-amyloid therapies have induced significant therapeutic effects. In this context, some inflammatory markers, especially if targeted before the onset of cognitive deterioration, may be an interesting marker to target. For instance, it has been suggested that some diets, such as the Mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diets, can improve cognition and also have an anti-inflammatory effect (van den Brink et al., 2019). Also, non-invasive brain stimulation can also improve cognition (Martins et al., 2017) and reduce inflammation in animal models (Laste et al., 2012; de Oliveira et al., 2019; Toledo et al., 2021). One of the limitations of the current review is not including studies related to comorbid vascular dementia, which is connected with AD and MCI especially in elderly patients.

5. Conclusion

This review included inflammatory biomarkers in AD and MCI conditions supported from cross sectional and longitudinal studies. Cross sectional studies included in this review and meta-analysis demonstrated remarkable alterations in the peripheral levels of CRP, IL-1β, IL-6, sTNFR1, and TNF alpha. The findings from longitudinal studies indicated that the risk of cognitive deterioration has been substantially increased by high IL-6 levels. However, intermediate IL-6 levels did not affect the outcome significantly. Neither CRP, ACT, Albumin, or TNF alpha have had a major influence on cognitive degradation. These results provided further proof that AD and MCI are accompanied by inflammatory processes originating in the CNS.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Adriaensen W., Matheï C., Vaes B., van Pottelbergh G., Wallemacq P., Degryse J., et al. (2014). Interleukin-6 predicts short-term global functional decline in the oldest old: Results from the BELFRAIL study. Age 36:9723. 10.1007/s11357-014-9723-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alley D. E., Crimmins E., Karlamangla A., Hu P., Seeman T. (2008). Inflammation and rate of cognitive change in high-functioning older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 63 50–55. 10.1093/gerona/63.1.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashraf-Ganjouei A., Moradi K., Bagheri S., Aarabi M. (2020). The association between systemic inflammation and cognitive performance in healthy adults. J. Neuroimmunol. 345:577272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baierle M., Nascimento S., Moro A., Brucker N., Freitas F., Gauer B., et al. (2015). Relationship between inflammation and oxidative stress and cognitive decline in the institutionalized elderly. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015:804198. 10.1155/2015/804198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begg C. B., Mazumdar M. (1994). Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics 50 1088–1101. 10.2307/2533446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benveniste E. N. (1998). Cytokine actions in the central nervous system. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 9 259–275. 10.1016/S1359-6101(98)00015-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun M. A., Dore G., Canas J., Liang H., Beydoun H., Evans M., et al. (2018). Systemic inflammation is associated with longitudinal changes in cognitive performance among urban adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 10:313. 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beydoun M. A., Weiss J., Obhi H., Beydoun H., Dore G., Liang H., et al. (2019). Cytokines are associated with longitudinal changes in cognitive performance among urban adults. Brain Behav. Immun. 80 474–487. 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.04.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonotis K., Krikki E., Holeva V., Aggouridaki C., Costa V., Baloyannis S. (2008). Systemic immune aberrations in Alzheimer’s disease patients. J. Neuroimmunol. 193 183–187. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2007.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boots E. A., Castellanos K., Zhan L., Barnes L., Tussing-Humphreys L., Deoni S., et al. (2020). Inflammation, cognition, and white matter in older adults: An examination by race. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12 553998. 10.3389/fnagi.2020.553998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozluolcay M., Andican G., Fırtına S., Erkol G., Konukoglu D. (2016). Inflammatory hypothesis as a link between Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes mellitus. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 16 1161–1166. 10.1111/ggi.12602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner I. K., Zamecnik J., Shek P., Shephard R. (1997). The impact of heat exposure and repeated exercise on circulating stress hormones. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 76 445–454. 10.1007/s004210050274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. M., Cui G., Jiang G., Xu R., Tang H., Wang G., et al. (2014). Cognitive impairment among elderly individuals in Shanghai suburb, China: Association of C-reactive protein and its interactions with other relevant factors. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Dement. 29 712–717. 10.1177/1533317514534758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi G. C., Fitzpatrick A., Sharma M., Jenny N., Lopez O., DeKosky S., et al. (2017). Inflammatory biomarkers predict domain-specific cognitive decline in older adults. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 72 796–803. 10.1093/gerona/glw155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi C., Jeong J., Jang J., Choi K., Lee J., Kwon J., et al. (2008). Multiplex analysis of cytokines in the serum and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease by color-coded bead technology. J. Clin. Neurol. 4 84–88. 10.3988/jcn.2008.4.2.84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciabattoni G., Porreca E., Di Febbo C., Di Iorio A., Paganelli R., Bucciarelli T., et al. (2007). Determinants of platelet activation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 28 336–342. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cumpston M., Li T., Page M., Chandler J., Welch V., Higgins J., et al. (2019). Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 10:ED000142. 10.1002/14651858.ED000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna L., Abu-Rumeileh S., Fabris M., Pistis C., Baldi A., Sanvilli N., et al. (2017). Serum Interleukin-10 levels correlate with cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta deposition in Alzheimer disease patients. Neurodegener. Dis. 17 227–234. 10.1159/000474940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R., O’Connor J., Freund G., Johnson R., Kelley K. (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 46–56. 10.1038/nrn2297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G., Baboolal N., Nayak S., McRae A. (2009). Sialic acid, homocysteine and CRP: Potential markers for dementia. Neurosci. Lett. 465 282–284. 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luigi A., Pizzimenti S., Quadri P., Lucca U., Tettamanti M., Fragiacomo C., et al. (2002). Peripheral inflammatory response in Alzheimer’s disease and multiinfarct dementia. Neurobiol. Dis. 11 308–314. 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira C., de Freitas J., Macedo I., Scarabelot V., Ströher R., Santos D., et al. (2019). Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) modulates biometric and inflammatory parameters and anxiety-like behavior in obese rats. Neuropeptides 73 1–10. 10.1016/j.npep.2018.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R., Laird N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin. Trials 7 177–188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dik M. G., Jonker C., Hack C., Smit J., Comijs H., Eikelenboom P. (2005). Serum inflammatory proteins and cognitive decline in older persons. Neurology 64 1371–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukic L., Simundic A., Martinic-Popovic I., Kackov S., Diamandis A., Begcevic I., et al. (2016). The role of human kallikrein 6, clusterin and adiponectin as potential blood biomarkers of dementia. Clin. Biochem. 49 213–218. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dursun E., Gezen-Ak D., Hanağası H., Bilgiç B., Lohmann E., Ertan S., et al. (2015). The interleukin 1 alpha, interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6 and alpha-2-macroglobulin serum levels in patients with early or late onset Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment or Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 283 50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duval S., Tweedie R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56 455–463. 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson A., Liu C., Hart R., Sawchenko P. (1995). Type 1 interleukin-1 receptor in the rat brain: Distribution, regulation, and relationship to sites of IL-1-induced cellular activation. J. Comp. Neurol. 361 681–698. 10.1002/cne.903610410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson U. K., Pedersen N., Reynolds C., Hong M., Prince J., Gatz M., et al. (2011). Associations of gene sequence variation and serum levels of C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 with Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. J. Alzheimers Dis. 23 361–369. 10.3233/JAD-2010-101671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ershler W. B. (1993). Interleukin-6: A cytokine for gerontologists. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 41 176–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlenza O. V., Diniz B., Talib L., Mendonça V., Ojopi E., Gattaz W., et al. (2009). Increased serum IL-1beta level in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 28 507–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung A., Vizcaychipi M., Lloyd D., Wan Y., Ma D. (2012). Central nervous system inflammation in disease related conditions: Mechanistic prospects. Brain Res. 1446 144–155. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.01.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giudici K. V., de Souto Barreto P., Guerville F., Beard J., Araujo de Carvalho I., Andrieu S., et al. (2019). Associations of C-reactive protein and homocysteine concentrations with the impairment of intrinsic capacity domains over a 5-year follow-up among community-dwelling older adults at risk of cognitive decline (MAPT Study). Exp. Gerontol. 127:110716. 10.1016/j.exger.2019.110716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein F. C., Zhao L., Steenland K., Levey A. (2015). Inflammation and cognitive functioning in African Americans and Caucasians. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 30 934–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunathilake R., Oldmeadow C., McEvoy M., Inder K., Schofield P., Nair B., et al. (2016). The association between obesity and cognitive function in older persons: How much is mediated by inflammation, fasting plasma glucose, and hypertriglyceridemia? J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 71 1603–1608. 10.1093/gerona/glw070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager K., Machein U., Krieger S., Platt D., Seefried G., Bauer J. (1994). Interleukin-6 and selected plasma proteins in healthy persons of different ages. Neurobiol. Aging 15 771–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar I., Hayek S., Goldstein F., Martin G., Jones D., Quyyumi A. (2018). Oxidative stress predicts cognitive decline with aging in healthy adults: An observational study. J. Neuroinflammation 15:17. 10.1186/s12974-017-1026-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herkenham M., Lee H. Y., Baker R. A. (1998). Temporal and spatial patterns of c-fos mRNA induced by intravenous interleukin-1: A cascade of non-neuronal cellular activation at the blood-brain barrier. J. Comp. Neurol. 400 175–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P., Thompson S., Deeks J., Altman D. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C. (2013). Review: Systemic inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 39 51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwig L., Macaskill P., Berry G., Glasziou P. (1998). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Graphical test is itself biased. BMJ 316 470–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger L. B., Dohgu S., Sultana R., Lynch J., Owen J., Erickson M., et al. (2009). Lipopolysaccharide alters the blood-brain barrier transport of amyloid beta protein: A mechanism for inflammation in the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav. Immun. 23 507–517. 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonakait G. M. (1997). Cytokines in neuronal development. Adv. Pharmacol. 37 35–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordanova V., Stewart R., Davies E., Sherwood R., Prince M. (2007). Markers of inflammation and cognitive decline in an African-Caribbean population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 22 966–973. 10.1002/gps.1772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y. H., Shin N., Jang J., Lee W., Lee D., Choi Y., et al. (2019). Relationships among stress, emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence, and cytokines. Medicine 98:e15345. 10.1097/MD.0000000000015345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamer A. R., Craig R., Pirraglia E., Dasanayake A., Norman R., Boylan R., et al. (2009). TNF-alpha and antibodies to periodontal bacteria discriminate between Alzheimer’s disease patients and normal subjects. J. Neuroimmunol. 216 92–97. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassner S. S., Bonaterra G., Kaiser E., Hildebrandt W., Metz J., Schröder J., et al. (2008). Novel systemic markers for patients with Alzheimer disease? - a pilot study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 5 358–366. 10.2174/156720508785132253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. S., Lee K. J., Kim H. (2017). Serum tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 levels in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Psychogeriatrics 17 224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King E., O’Brien J., Donaghy P., Morris C., Barnett N., Olsen K., et al. (2018). Peripheral inflammation in prodromal Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementias. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 89 339–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komulainen P., Lakka T., Kivipelto M., Hassinen M., Penttilä I., Helkala E., et al. (2007). Serum high sensitivity C-reactive protein and cognitive function in elderly women. Age Ageing 36 443–448. 10.1093/ageing/afm051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Q. L., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Ge P., Xu Y., Mi R., et al. (2002). [Serum levels of macrophage colony stimulating factor in the patients with Alzheimer’s disease]. Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao 24 298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronfol Z., Remick D. G. (2000). Cytokines and the brain: Implications for clinical psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 157 683–694. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laste G., Caumo W., Adachi L., Rozisky J., de Macedo I., Filho P., et al. (2012). After-effects of consecutive sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in a rat model of chronic inflammation. Exp. Brain Res. 221 75–83. 10.1007/s00221-012-3149-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Page A., Dupuis G., Frost E., Larbi A., Pawelec G., Witkowski J., et al. (2018). Role of the peripheral innate immune system in the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Exp. Gerontol. 107 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung R., Proitsi P., Simmons A., Lunnon K., Güntert A., Kronenberg D., et al. (2013). Inflammatory proteins in plasma are associated with severity of Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One 8:e64971. 10.1371/journal.pone.0064971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licastro F., Pedrini S., Caputo L., Annoni G., Davis L., Ferri C., et al. (2000). Increased plasma levels of interleukin-1, interleukin-6 and alpha-1-antichymotrypsin in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: Peripheral inflammation or signals from the brain? J. Neuroimmunol. 103 97–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Licinio J., Wong M. L. (1997). Interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene expression in rat pituitary in the systemic inflammatory response syndrome: Pathophysiological implications. Mol. Psychiatry 2 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linthorst A. C., Flachskamm C., Müller-Preuss P., Holsboer F., Reul J. (1995). Effect of bacterial endotoxin and interleukin-1 beta on hippocampal serotonergic neurotransmission, behavioral activity, and free corticosterone levels: An in vivo microdialysis study. J. Neurosci. 15 2920–2934. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-04-02920.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano D. A., Li J., Waring J., Ellis T., Devanarayan V., Witte D., et al. (2012). Cerebrospinal fluid cytokine dynamics differ between Alzheimer disease patients and elderly controls. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 26 322–328. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31823b2728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marioni R. E., Stewart M., Murray G., Deary I., Fowkes F., Lowe G., et al. (2009). Peripheral levels of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, and plasma viscosity predict future cognitive decline in individuals without dementia. Psychosom. Med. 71 901–906. 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181b1e538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A. R., Fregni F., Simis M., Almeida J. (2017). Neuromodulation as a cognitive enhancement strategy in healthy older adults: Promises and pitfalls. Neuropsychol. Dev. Cogn. B Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 24 158–185. 10.1080/13825585.2016.1176986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCusker R. H., Kelley K. W. (2013). Immune-neural connections: How the immune system’s response to infectious agents influences behavior. J. Exp. Biol. 216(Pt 1), 84–98. 10.1242/jeb.073411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh Power J., Carney S., Hannigan C., Brennan S., Wolfe H., Lynch M., et al. (2019). Systemic inflammatory markers and sources of social support among older adults in the Memory Research Unit cohort. J. Health Psychol. 24 397–406. 10.1177/1359105316676331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merali Z., Lacosta S., Anisman H. (1997). Effects of interleukin-1beta and mild stress on alterations of norepinephrine, dopamine and serotonin neurotransmission: A regional microdialysis study. Brain Res. 761 225–235. 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00312-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohankumar P. S., Thyagarajan S., Quadri S. K. (1991). Interleukin-1 stimulates the release of dopamine and dihydroxyphenylacetic acid from the hypothalamus in vivo. Life Sci. 48 925–930. 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90040-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooijaart S. P., Sattar N., Trompet S., Polisecki E., de Craen A., Schaefer E., et al. (2011). C-reactive protein and genetic variants and cognitive decline in old age: The PROSPER study. PLoS One 6:e23890. 10.1371/journal.pone.0023890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryant S. E., Lista S., Rissman R., Edwards M., Zhang F., Hall J., et al. (2016). Comparing biological markers of Alzheimer’s disease across blood fraction and platforms: Comparing apples to oranges. Alzheimers Dement. 3 27–34. 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M. J., McKenzie J., Bossuyt P., Boutron I., Hoffmann T., Mulrow C., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolaou D. A., Wilder R., Manolagas S., Chrousos G. (1998). The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann. Intern. Med. 128 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcellini E., Davis E., Chiappelli M., Ianni E., Di Stefano G., Forti P., et al. (2008). Elevated plasma levels of alpha-1-anti-chymotrypsin in age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease: A potential therapeutic target. Curr. Pharm. Des. 14 2659–2664. 10.2174/138161208786264151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prat A., Biernacki K., Antel J. P. (2005). Th1 and Th2 lymphocyte migration across the human BBB is specifically regulated by interferon beta and copolymer-1. J. Autoimmun. 24 119–124. 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafnsson S. B., Deary I., Smith F., Whiteman M., Rumley A., Lowe G., et al. (2007). Cognitive decline and markers of inflammation and hemostasis: The Edinburgh Artery Study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 55 700–707. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01158.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C., Gard P., Klugman A., Isaac M., Tabet N. (2013). Blood pro-inflammatory cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease in relation to the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 28 1312–1317. 10.1002/gps.3966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richartz E., Stransky E., Batra A., Simon P., Lewczuk P., Buchkremer G., et al. (2005). Decline of immune responsiveness: A pathogenetic factor in Alzheimer’s disease? J. Psychiatr. Res. 39 535–543. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roubenoff R., Harris T., Abad L., Wilson P., Dallal G., Dinarello C. (1998). Monocyte cytokine production in an elderly population: Effect of age and inflammation. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 53 M20–M26. 10.1093/gerona/53A.1.M20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Perez J. M., Morillas-Ruiz J. M. (2013). Serum cytokine profile in Alzheimer’s disease patients after ingestion of an antioxidant beverage. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 12 1233–1241. 10.2174/18715273113129990075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez M. A., Santiago E., Arronte-Rosales A., Vargas-Guadarrama L., Mendoza-Núñez V. (2006). Relationship between oxidative stress and cognitive impairment in the elderly of rural vs. urban communities. Life Sci. 78 1682–1687. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankowski R., Mader S., Valdes-Ferrer S. I. (2015). Systemic inflammation and the brain: Novel roles of genetic, molecular, and environmental cues as drivers of neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 9:28. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasayama D., Hori H., Teraishi T., Hattori K., Ota M., Matsuo J., et al. (2012). Association of cognitive performance with interleukin-6 receptor Asp358Ala polymorphism in healthy adults. J. Neural Transm. 119 313–318. 10.1007/s00702-011-0709-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schram M. T., Euser S., de Craen A., Witteman J., Frölich M., Hofman A., et al. (2007). Systemic markers of inflammation and cognitive decline in old age. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 55 708–716. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01159.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempowski G. D., Hale L., Sundy J., Massey J., Koup R., Douek D., et al. (2000). Leukemia inhibitory factor, oncostatin M, IL-6, and stem cell factor mRNA expression in human thymus increases with age and is associated with thymic atrophy. J. Immunol. 164 2180–2187. 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma M., Fitzpatrick A., Arnold A., Chi G., Lopez O., Jenny N., et al. (2016). Inflammatory biomarkers and cognitive decline: The Ginkgo evaluation of memory study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 64 1171–1177. 10.1111/jgs.14140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X. N., Niu L., Wang Y., Cao X., Liu Q., Tan L., et al. (2019). Inflammatory markers in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A meta-analysis and systematic review of 170 studies. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 90 590–598. 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J. G., Mrak R. E., Griffin W. S. (1998). Enlarged and phagocytic, but not primed, interleukin-1 alpha-immunoreactive microglia increase with age in normal human brain. Acta Neuropathol. 95 229–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Zhang S., Xue Y., Yang Z., Lin Y., Liu L., et al. (2020). IL-35 polymorphisms and cognitive decline did not show any association in patients with coronary heart disease over a 2-year period: A retrospective observational study (STROBE compliant). Medicine 99:e21390. 10.1097/MD.0000000000021390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani F., Kanba S., Nakaki T., Nibuya M., Kinoshita N., Suzuki E., et al. (1993). Interleukin-1 beta augments release of norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin in the rat anterior hypothalamus. J. Neurosci. 13 3574–3581. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03574.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A., Dugravot A., Brunner E., Kumari M., Shipley M., Elbaz A., et al. (2014). Interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein as predictors of cognitive decline in late midlife. Neurology 83 486–493. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sochocka M., Sobczyński M., Sender-Janeczek A., Zwolińska K., Błachowicz O., Tomczyk T., et al. (2017). Association between periodontal health status and cognitive abilities. The role of cytokine profile and systemic inflammation. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 14 978–990. 10.2174/1567205014666170316163340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swardfager W., Lanctôt K., Rothenburg L., Wong A., Cappell J., Herrmann N. (2010). A meta-analysis of cytokines in Alzheimer’s disease. Biol. Psychiatry 68 930–941. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda S., Sato N., Ikimura K., Nishino H., Rakugi H., Morishita R., et al. (2013). Increased blood-brain barrier vulnerability to systemic inflammation in an Alzheimer disease mouse model. Neurobiol. Aging 34 2064–2070. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teblick A., Peeters B., Langouche L., Van den Berghe G. (2019). Adrenal function and dysfunction in critically ill patients. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 15 417–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira A. L., Reis H., Coelho F., Carneiro D., Teixeira M., Vieira L., et al. (2008). All-or-nothing type biphasic cytokine production of human lymphocytes after exposure to Alzheimer’s beta-amyloid peptide. Biol. Psychiatry 64 891–895. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen C. E., Lütjohann D., von Bergmann K., Verhey F., Vreeling F., Wauters A., et al. (2003). Combination of serum markers related to several mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 24 893–902. 10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilvis R. S., Kähönen-Väre M., Jolkkonen J., Valvanne J., Pitkala K., Strandberg T., et al. (2004). Predictors of cognitive decline and mortality of aged people over a 10-year period. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 59 268–274. 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo R. S., Stein D., Sanches P., da Silva L., Medeiros H., Fregni F., et al. (2021). rTMS induces analgesia and modulates neuroinflammation and neuroplasticity in neuropathic pain model rats. Brain Res. 1762:147427. 10.1016/j.brainres.2021.147427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uslu S., Akarkarasu Z., Ozbabalik D., Ozkan S., Colak O., Demirkan E., et al. (2012). Levels of amyloid beta-42, interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Neurochem. Res. 37 1554–1559. 10.1007/s11064-012-0750-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Brink A. C., Brouwer-Brolsma E., Berendsen A., van de Rest O. (2019). The mediterranean, dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH), and mediterranean-DASH Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) diets are associated with less cognitive decline and a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease-a review. Adv. Nutr. 10 1040–1065. 10.1093/advances/nmz054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal A. E., O’Bryant S., Edwards M., Grajales S., Britton G. Panama Aging Research Initiative. (2016). Serum-based protein profiles of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in elderly Hispanics. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 6 203–213. 10.2217/nmt-2015-0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitkovic L., Konsman J., Bockaert J., Dantzer R., Homburger V., Jacque C. (2000b). Cytokine signals propagate through the brain. Mol. Psychiatry 5 604–615. 10.1038/sj.mp.4000813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitkovic L., Bockaert J., Jacque C. (2000a). “Inflammatory” cytokines: Neuromodulators in normal brain? J. Neurochem. 74 457–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Xiao S., Liu Y., Lin Z., Su N., Li X., et al. (2014). The efficacy of plasma biomarkers in early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 29 713–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver J. D., Huang M., Albert M., Harris T., Rowe J., Seeman T. (2002). Interleukin-6 and risk of cognitive decline: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Neurology 59 371–378. 10.1212/wnl.59.3.371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei J., Xu H., Davies J., Hemmings G. (1992). Increase of plasma IL-6 concentration with age in healthy subjects. Life Sci. 51 1953–1956. 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells G., Shea B. J., O’Connell D., Peterson J., Welch V., Losos M., et al. (2000). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Available online at: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm (accessed December, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C. J., Finch C. E., Cohen H. J. (2002). Cytokines and cognition–the case for a head-to-toe inflammatory paradigm. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 50 2041–2056. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50619.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K., Lindquist K., Penninx B., Simonsick E., Pahor M., Kritchevsky S., et al. (2003). Inflammatory markers and cognition in well-functioning African-American and white elders. Neurology 61 76–80. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073620.42047.d7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Chen Y., Zhang W., Zhang Z., Yang X., Wang P., et al. (2020). Association between inflammatory biomarkers and cognitive dysfunction analyzed by MRI in diabetes patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 13 4059–4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarchoan M., Louneva N., Xie S., Swenson F., Hu W., Soares H., et al. (2013). Association of plasma C-reactive protein levels with the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 333 9–12. 10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye S. M., Johnson R. W. (1999). Increased interleukin-6 expression by microglia from brain of aged mice. J. Neuroimmunol. 93 139–148. 10.1016/S0165-5728(98)00217-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya E. T., Mekori-Domachevsky E., Weinberger R., Taler M., Carmel M., Gothelf D., et al. (2020). Exploring the potential association among sleep disturbances, cognitive impairments, and immune activation in 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 182 461–468. 10.1002/ajmg.a.61424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B., Schwartz J. P. (1998). Involvement of cytokines in normal CNS development and neurological diseases: Recent progress and perspectives. J. Neurosci. Res. 52 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S. J., Guo C., Wang M., Chen W., Zhao Y. (2012). Serum levels of inflammation factors and cognitive performance in amnestic mild cognitive impairment: A Chinese clinical study. Cytokine 57 221–225. 10.1016/j.cyto.2011.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng M., Chang B., Tian L., Shan C., Chen H., Gao Y., et al. (2019). Relationship between inflammatory markers and mild cognitive impairment in Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes: A case-control study. BMC Endocr. Disord. 19:73. 10.1186/s12902-019-0402-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Chai Y., Hilal S., Ikram M., Venketasubramanian N., Wong B., et al. (2017). Serum IL-8 is a marker of white-matter hyperintensities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7 41–47. 10.1016/j.dadm.2017.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuliani G., Ranzini M., Guerra G., Rossi L., Munari M., Zurlo A., et al. (2007). Plasma cytokines profile in older subjects with late onset Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 41 686–693. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.