Abstract

Malaysia reported the first human case of Nipah virus (NiV) in late September 1998 with encephalitis and respiratory symptoms. As a result of viral genomic mutations, two main strains (NiV-Malaysia and NiV-Bangladesh) have spread around the world. There are no licensed molecular therapeutics available for this biosafety level 4 pathogen. NiV attachment glycoprotein plays a critical role in viral transmission through its human receptors (Ephrin-B2 and Ephrin-B3), so identifying small molecules that can be repurposed to inhibit them is crucial to developing anti-NiV drugs. Consequently, in this study annealing simulations, pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics were used to evaluate seven potential drugs (Pemirolast, Nitrofurantoin, Isoniazid Pyruvate, Eriodictyol, Cepharanthine, Ergoloid, and Hypericin) against NiV-G, Ephrin-B2, and Ephrin-B3 receptors. Based on the annealing analysis, Pemirolast for efnb2 protein and Isoniazid Pyruvate for efnb3 receptor were repurposed as the most promising small molecule candidates. Furthermore, Hypericin and Cepharanthine, with notable interaction values, are the top Glycoprotein inhibitors in Malaysia and Bangladesh strains, respectively. In addition, docking calculations revealed that their binding affinity scores are related to efnb2-pem (− 7.1 kcal/mol), efnb3-iso (− 5.8 kcal/mol), gm-hyp (− 9.6 kcal/mol), gb-ceph (− 9.2 kcal/mol). Finally, our computational research minimizes the time-consuming aspects and provides options for dealing with any new variants of Nipah virus that might emerge in the future.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11030-023-10624-8.

Keywords: Nipah virus, Glycoprotein, Ephrin-B2, Ephrin-B3, Annealing simulation, Molecular docking

Introduction

The first case of Nipah virus (NiV) in late September 1998 occurred in Malaysia and was repeatedly distributed in South and Southeast Asia namely Singapore (in 1999), Bangladesh (in 2001), and the Philippines (in 2014) [1]. The most recent NiV outbreak occurred in 2018 in Kerala, India, with a case-fatality rate of 91%. Genetic analysis from different geographical areas has identified at least two strains of NiV, known as Malaysia and Bangladesh, and the sequence analysis of NiV-India revealed 97% similarity to the NiV-Bangladesh lineage [2, 3]. NiV has a threefold viral circulation between fruit bats, pigs, and human beings through transmission from bats to pigs, pigs to humans, and from date palm sap to humans but based on various outbreaks documented from different geographical parts of the globe, fruit bats (Pteropus giganteus) have been associated as the main reservoir of NiV transmission and due to a large number of bats around the world, an infection carried long distances and cause a deadly pandemic [4, 5]. Nipah virus is a species of the genus Henipaviruses that belongs to the Paramyxoviridae family and is closely related to Hendra virus [6]. This enveloped virus contains negative-sense single-stranded RNA [7]. NiV causes severe respiratory disease, and encephalitis with fatality rates up to 90%, therefore, is classified as a biosafety level 4 pathogen [8, 9]. In addition, NiV can also result in relapsing encephalitis, from several months to more than 10 years later, following a recovery from an acute infection as a result of recrudescence of virus replication in the central nervous system [10]. These mentioned abilities for transmission as well as the lack of a vaccine or efficient treatment have caused the NiV has the high potential to commence a deadly pandemic or be used in biological warfare [11].

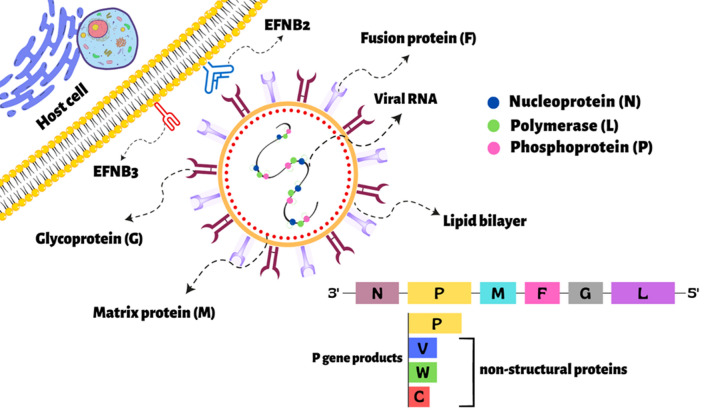

NiV genomes encode six structural proteins: nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein (M), fusion glycoprotein (F), attachment glycoprotein (G), and RNA-directed RNA polymerase protein (L). The N, P and L proteins contain the replication complex. The P gene undergoes RNA editing to beget two additional non-structural proteins, V and W, that are interferon (IFN) antagonists. The C non-structural protein is transcribed from a second open reading frame in the P gene (Fig. 1) [12]. The P protein binds to the N protein and increases its specificity towards viral RNA and as a result, this constructed complex forms the nucleocapsid. This nucleocapsid acts as a pattern for polymerase protein to replicate itself and the host machinery is then utilized to translate its proteins [13]. The W and V non-structural proteins have been reported to inhibit the IFN signaling pathway, and the C protein also has a weak inhibitory. Therefore, Nipah virus non-structural proteins have anti-immune response functions and play key roles in pathogenicity [14]. NiV enters the host cells through the concerted action of an attachment glycoprotein and a fusion glycoprotein, which are the main targets of the humoral immune response [15]. However, the viral matrix protein function seems to be integral to the viral organization, facilitates the assembly, and coordinates virion budding. Furthermore, the M protein at the interior surface of the virion hijacks cellular trafficking and ubiquitination trails to facilitate transient nuclear localization [16, 17, 18]. The attachment of viral glycoprotein to cell-surface receptors Ephrin-B2 (EFNB2) and Ephrin-B3 (EFNB3) are essential for virus fusion and entry (Fig. 1) [19]. Ephrin receptor families are part of the receptor tyrosine kinases and are expressed by the number of non-neural cells, hematopoietic cells, tumor cells, and arterial [20].

Fig. 1.

The Nipah virus structural and non-structural protein structures along with the human efnb2 and efnb3 receptors

Several studies have been completed to search for appropriate small molecules for anti-NiV treatments. Dawes et al. [21] in a recent experimental study demonstrated that Favipiravir (T-705) has potent antiviral activity against henipaviruses. Favipiravir is a purine analog with the efficacy of inhibiting Nipah and Hendra viruses’ replication and transcription [21]. Moreover, Lo et al. [22] reported that GS-5734 had antiviral activity across multiple virus families such as NiV-Malaysia, and NiV-Bangladesh infections and they could provide evidence to support new indications for this monophosphate prodrug against antiviral therapies [22]. Another related study evaluated the antiviral activity of 4′-azidocytidine (R1479) to inhibit henipaviruses along with other representative members of the family Paramyxoviridae, and finally, they documented its antiviral therapeutics across both negative and positive-sense RNA viruses [23]. Based on the mentioned studies since up to now there is no licensed drug against NiV, there is a strong need to discover small molecule inhibitors against NiV with high-potential therapeutic rates. Traditionally small molecules have been designed for targeting a single biological entity such as a protein. However, at the beginning of the 2000s, the concept of multi-target drugs made rapid and spectacular progress so nowadays multi-target drugs are already available on the market [24]. In the three mentioned articles, several Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) strategies including molecular docking, machine learning, molecular dynamic simulation, pharmacophore-based, structure–activity relationship (SAR), quantitative structure–activity relationship (QSAR), and combination methods were developed to facilitate the screening of new compounds with one-compound-multiple-target characteristics [25, 26, 27].

In this computational study, the interactions of the potential SARS-CoV-2 drugs with clinical studies against Malaysia, and Bangladesh Nipah virus Glycoprotein along with the human Ephrin-B2 and Ephrin-B3 receptors were assessed. The NiV structural glycoprotein from Malaysia and Bangladesh strains and efnb2 and efnb3 receptors were modeled as a receptor, and their interactions with Pemirolast, Nitrofurantoin, Isoniazid Pyruvate, Eriodictyol, Cepharanthine, Ergoloid, and Hypericin were calculated. It is important to understand the protein mutation impacts and infection changes accordingly for anti-NiV treatments. In this study bioinformatics methods such as annealing simulations, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamic simulations have used to evaluate the interactions between inhibitors and proteins. Five main steps of pipeline are represented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 .

A schematic flowchart of the methodology steps

Materials and methods

Preparation and mutation

The X-ray-derived 3D crystal structures of ephrin-B2 (PDB ID: 2VSM), and ephrin-B3 (PDB ID: 3D12) were attained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank website [28, 29]. Since 2VSM contains Nipah henipavirus Hemagglutinin-neuraminidase in complex with human cell surface receptor ephrin-B2, first, the G protein was removed from the PDB file using UCSF Chimera 1.16 software [30]. Therefore, only chain ephrin-B2 with 140 sequence length along with one NAG group (2-acetamido-2-deoxy-beta-D-glucopyranose) remained. This NAG group was not considered in the following analysis because our goal was to repurpose drugs and not co-crystal molecules. The 3D12 PDB file contains Ephrin-B3 with 141 sequence lengths and two non-standard residues (HOH and SO4). On the other hand, the reference NiV-Malaysia and NiV-Bangladesh strains were generated based on GenBank accession numbers AJ627196.1 and AY988601.1 respectively [31] using SWISS-MODEL [32]. The critical glycoprotein substitutions in two main variants Malaysia (GM) and Bangladesh (GB) could be observed in Supplementary Fig. 1. Based on Shamsi et al. [33] review study, seven potential drugs with clinical effectiveness in COVID-19 therapy which target human ACE2 receptor and SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein were used as specific inhibitors against human ephrin-B2, ephrin-B3 receptors and Nipah virus Glycoprotein in two Malaysia and Bangladesh strains [33]. In fact, Pemirolast, Nitrofurantoin, Isoniazid Pyruvate, and Eriodictyol which are specific ACE2 inhibitors were repurposed for human ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3 receptors, and Cepharanthine, Ergoloid, and Hypericin drugs which are targeting SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein were analyzed against Nipah virus Glycoprotein. The SDF format of each drug was obtained from the ZINC15 free database [34].

Annealing simulations

To gain the most efficient energy form of each protein–inhibitor complex (efnb2-pemirolast, efnb2-nitrofurantoin, efnb2-isoniazid pyruvate, efnb2-eriodictyol, efnb3-pemirolast, efnb3-nitrofurantoin, efnb3-isoniazid pyruvate, efnb3-eriodictyol, Malaysia glycoprotein-cepharanthine, Malaysia glycoprotein-ergoloid, Malaysia glycoprotein-hypericin, Bangladesh glycoprotein-cepharanthine, Bangladesh glycoprotein-ergoloid, and Bangladesh glycoprotein-hypericin) before running annealing simulations the complexes were optimized geometrically by the smart algorithm with a maximum of 500 iterations using an adsorption locator. Then a classical annealing simulation with ultra-fine quality was completed using Materials Studio software [35], and was set to an initial temperature of 200 K, a midcycle temperature of 500 K, and 50 heating ramps per cycle, a total of 200 cycles with 100 dynamic steps per ramp. The canonical ensemble NVT was applied to relax the minimized systems during a time step of 1.0 fs dynamic simulations by the Nosé thermostat. The universal force field with charges assigned [36] and the 18.5 Å cutoff radius was chosen to continue these simulations. All the runs were performed with a spline width of 1.0 Å and a buffer width of 0.5 Å. After each simulation, the second step of energy minimization was performed with conjugate gradient algorithms to remove any unwanted contacts and clashes. Simulations were repeatedly carried out with 4 cores running in parallel for 14 protein−inhibitor complexes. Finally, the lowest energy configuration was optimized, and the total kinetic, total potential, bond energy, van der Waals energy, electrostatic and non-bond energy of the studied systems were calculated.

We computed the interaction energy between the protein−inhibitor complexes by:

| 1 |

where Eprotein−inhibitor, Eprotein, and Einhibitor represent the protein-inhibitor complex energy, the isolated proteins (efnb2, efnb3, Malaysia glycoprotein, and Bangladesh glycoprotein), and the individual inhibitors (pemirolast, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid pyruvate, eriodictyol, cepharanthine, ergoloid, and hypericin), respectively.

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling

ZINCPharmer web interface was used for the modeling of pharmacophore features that are essential for identifying the interactions of potential inhibitors with proteins [37]. Typical pharmacophore features include hydrophobic centroids, aromatic rings, hydrogen bond acceptors and/or donors, anions, and cations. In this analysis, seven inhibitors including pemirolast, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid pyruvate, eriodictyol, cepharanthine, ergoloid, and hypericin were analyzed to generate the ligand-based pharmacophore model. These modeling results were validated through molecular docking.

Molecular docking and validation

The AutoDock Vina software [38, 39] was employed to evaluate the binding affinities of the protein-inhibitor complexes. Four PDB format receptors with seven SDF format ligands were used as input for molecular docking. Before running, based on AutoDock Vina documentation, native ligands, redundant water molecules, and non-standard residues were removed from receptor files. However polar hydrogen atoms and Gasteiger charges [40] were added using UCSF Chimera 1.16 software. All of the receptors have stayed on the lowest energy level through the steepest descent and conjugate gradient consecutive steps of energy minimization. The number of generations was set to nine and then, the most appropriate pose was selected for interaction analysis. The molecular docking results were further validated using two other docking simulation programs, SwissDock [41, 42], and HDock [43]. To maintain the conditions of each docking tool, blind molecular docking was used in AutoDock Vina software. The grid box parameters as shown in Table 1, were enclosed in the following dimensions. A spacing value of 1 Å was constructed. Additionally, protein–ligand interactions were analyzed through the Discovery Studio Visualizer [44].

Table 1.

The grid box center and size dimensions

| Protein name | Center (x, y, z) | Size (x, y, z) |

|---|---|---|

| Ephrin-B2 | 31.149 Å × 57.528 Å × − 45.98 Å | 33 Å × 37 Å × 31 Å |

| Ephrin-B3 | 29.506 Å × − 117.543 Å × − 90.961 Å | 32 Å × 29 Å × 32 Å |

| Glycoprotein | 243.951 Å × 227.34 Å × 275.793 Å | 57 Å × 52 Å × 50 Å |

Molecular dynamics simulation

Based on molecular dynamics simulations, four candidate complexes were evaluated for their stability and molecular motion using the iMOD server (iMODS) (http://imods.chaconlab.org/) [45]. iMODS was utilized for the analysis of the structural dynamics of the docking complexes, along with the determination of physical movement. Top docked complexes from previous sections (efnb2-pem, efnb3-iso, gm-hyp, gb-ceph) were investigated in normal mode analysis to determine deformability, B-factor, eigenvalue, variance, covariance map and elastic network. The input PDB files were uploaded to iMODS, with default parameters including 300 K constant temperature, 1 atm constant pressure, and 50 ns molecular dynamic simulation was carried out for all the complexes.

Result and discussion

Annealing simulation calculations

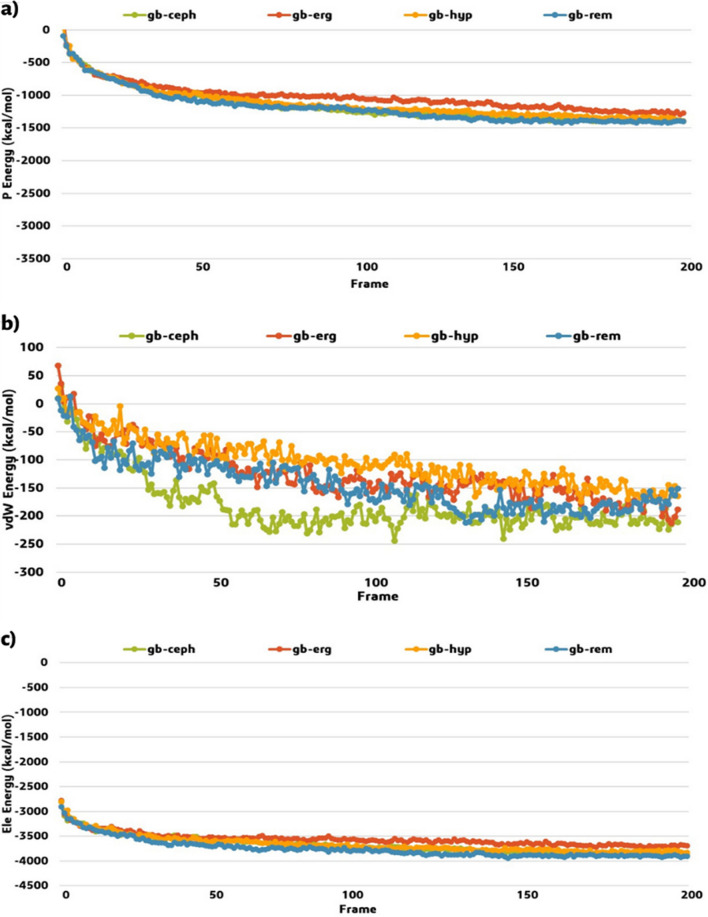

Simulated annealing has been successfully used in several protein–ligand interactions and drug discovery studies [46]. In the recent study done by Zhang et al. (2021) to assess the interactions between carbon nanoparticles and SARS-CoV-2 RNA fragment, inspired us for this simulation [47]. In this study, the annealing simulations have mainly suggested the molecular interactions between protein-inhibitor. Our simulation study consists of two main steps; (I) the adsorption locator module has been used for the identity binding sites and the energetics of substrates to investigate the preferential adsorption of the components. This technique is performed based on Monte Carlo simulation of a substrate-adsorbate system. Thus, the PDB format of the protein substrates (efnb2, efnb3, Malaysia, and Bangladesh Glycoproteins) besides the PDB format of the small molecules (pemirolast, nitrofurantoin, isoniazid pyruvate, eriodictyol, cepharanthine, ergoloid, and hypericin) were loaded with the constant default setup. The best energy adsorption configurations were entered in the second step. (II) the forcite module has been used for annealing simulated in the mentioned conditions. Moreover, a total of 200 annealing cycles which illustrated an optimal balance of total energy were simulated. The evaluation of the potential energy (P), van der Waals (vdW), and electrostatic energy (Ele) of the complexes during annealing simulation in 200 frames are shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5, and 6. The idea behind the annealing simulation is to evaluate both intramolecular energy terms of the ligand and the intermolecular ligand–protein interaction energy in a stable geometry. The optimized conformations of the complexes obtained after the simulation procedure and the total kinetic energy (ΔEK), total potential energy (ΔEP), bond energy (ΔEB), van der Waals energy (ΔEvdW), electrostatic energy (ΔEEle), and non-bond energy (ΔENB) are summarized in Table 2. In this table, we used the first three letters of each drug, in addition, gm, and gb abbreviations are related to the glycoprotein Malaysia, and glycoprotein Bangladesh, respectively. The negative computed values are indicating that the inhibitors have strong interactions with human and NiV proteins, hence the lowest energy adsorption configurations are related to the best inhibition efficiencies, and the top-ranking order. Therefore, these values will be processed for the interaction energies including potential interaction energy (Eint−P), bond interaction energy (Eint−B), van der Waals interaction energy (Eint−vdW), electrostatic interaction energy (Eint−Ele), and non-bond interaction energy (Eint−NB). By eliminating the small molecule and then the protein from the optimized complex, the interaction energies were computed (Table 3). According to the results, when the interaction energy values are more negative, not only the interaction force between protein–ligand is noteworthy, but also the complex with low interaction energy values is more stable. As shown in Table 3, since the rem (Eint−P), pem (Eint−B), rem (Eint−vdW), rem (Eint−Ele), and rem (Eint−NB) have noteworthy interaction values in the mentioned categories, these two small molecules were found as the efnb2 inhibitors. Moreover, the iso (Eint−P), rem (Eint−B), rem (Eint−vdW), iso (Eint−Ele), and iso (Eint−NB) have significant interaction values as the efnb3 inhibitors. The hyp (Eint−P), ceph (Eint−B), hyp (Eint−vdW), hyp (Eint−Ele), and hyp (Eint−NB) were discovered as the Glycoprotein Malaysia inhibitors, and the rem (Eint−P), rem (Eint−B), ceph (Eint−vdW), rem (Eint−Ele), and ceph (Eint−NB) with the appropriate interaction values are the top Glycoprotein Bangladesh inhibitors. Based on the in vitro examination, remdesivir (GS-5734) showed potent antiviral activity against both Malaysian and Bangladesh genotypes of the Nipah virus and reduced viral replication in primary human lung microvascular endothelial cells by more than four orders of magnitude. Therefore, remdesivir, an anti-NiV compound experimentally, was used as the positive control compound and other results were compared with its values to the whole work make more sense [48]. In Table 2, remdesivir is abbreviated as rem, and between the efnb2-inhibitors, in potential energy, pem (− 2618.05 kJ/mol) has the maximum (less interaction) and nit (− 2887.36 kJ/mol) has the minimum (more interaction) values. In van der Waals interaction, pem (− 109.53 kJ/mol) has the maximum and rem (− 139.85 kJ/mol) has the minimum values, also in electrostatic energy, eri (− 2531.35 kJ/mol) has the maximum, and rem (− 2712.77 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. Thus, nitrofurantoin and remdesivir with further interaction values are found as the efnb2 inhibitors. Between the efnb3-inhibitors, in potential energy, pem (− 6442.07 kJ/mol) has the maximum, and iso (− 7164.23 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. In van der Waals interaction, pem (− 32.51 kJ/mol) has the maximum and iso (− 73.15 kJ/mol) has the minimum values, also in electrostatic energy, pem (− 6967.42 kJ/mol) has the maximum, and iso (− 7494.71 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. Hence, isoniazid pyruvate has remarkable interaction values in all three categories as the efnb3 inhibitors. Among the gm-inhibitors, in potential energy, erg (− 1369.77 kJ/mol) has the maximum and hyp (− 1700.16 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. In van der Waals interaction, rem (− 187.003 kJ/mol) has the maximum and hyp (− 264.99 kJ/mol) has the minimum values, also in electrostatic energy, erg (− 3797.48 kJ/mol) has the maximum and hyp (− 4042.52 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. Thus, hypericin has noteworthy interaction values in all three categories as Glycoprotein Malaysia inhibitors. Among the gb-inhibitors, in potential energy, erg (− 1273.36 kJ/mol) has the maximum and ceph (− 1402.48 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. In van der Waals interaction, rem (− 151.07 kJ/mol) has the maximum and ceph (− 210.94 kJ/mol) has the minimum values, also in electrostatic energy, erg (− 3694.47 kJ/mol) has the maximum, and rem (3902.64 kJ/mol) has the minimum values. Therefore, cepharanthine and remdesivir have significant interaction values as Glycoprotein Bangladesh inhibitors. In the case of NiV glycoprotein, hyp and rem have the top valuable interactions with gm and gb, respectively. Additionally, ceph was found as both variant inhibitors. Since up to now there is not any equal study for NiV, the closest molecular dynamics study was selected for comparison. Sen et al. [13] carried out 100 ns of molecular dynamic simulations and binding free energy calculations on all the designed Nipah virus protein-peptide complexes and the 13 top shortlisted small molecule ligands to check their stability and binding strengths. For each trajectory, the total potential energy, the distance between the center of the protein and peptide, RMSD, and RMSF of the complexes were analyzed. The small molecule inhibitors of the fusion and matrix proteins bind with ~ 110 kJ/mol potential interaction energy. However, in the case of glycoprotein, two peptide inhibitors (FSPNLW and LAPHPSQ) bind to the glycoprotein with ~ 100 and ~ 60 kJ/mol respectively [13]. Two candidate small molecules for gm (hyp and ceph) with − 350.34 and − 163.57 kJ/mol potential interaction energy show strong results. However, rem (− 41.67 kJ/mol) and ceph (− 22.27 kJ/mol) against gb protein are not proper enough.

Fig. 3.

Variation of a potential (P) energy, b van der Waals (vdW) energy, and c electrostatic (Ele) energy of the efnb2 protein-inhibitors complexes

Fig. 4.

Variation of a potential (P) energy, b van der Waals (vdW) energy, and c electrostatic (Ele) energy of the efnb3 protein-inhibitors complexes

Fig. 5.

Variation of a potential (P) energy, b van der Waals (vdW) energy, and c electrostatic (Ele) energy of the glycoprotein Malaysia-inhibitors complexes

Fig. 6.

Variation of a potential (P) energy, b van der Waals (vdW) energy, and c electrostatic (Ele) energy of the glycoprotein Bangladesh–inhibitors complexes

Table 2.

Calculated protein–inhibitor complexes energy (kJ/mol)

| Complex | ΔEK | ΔEP | ΔEB | ΔEvdW | ΔEEle | ΔENB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| efnb2-pem | 1380.75 | − 2618.05 | 186.21 | − 109.53 | − 2532.74 | − 2642.28 |

| efnb2-nit | 1387.28 | − 2887.36 | 199.53 | − 117.80 | − 2651.81 | − 2769.62 |

| efnb2-iso | 1388.27 | − 2848.29 | 208.95 | − 134.06 | − 2634.04 | − 2768.11 |

| efnb2-eri | 1367.38 | − 2685.39 | 224.53 | − 134.08 | − 2531.35 | − 2665.44 |

| efnb2-rem | 1401.38 | − 2879.89 | 207.68 | − 139.85 | − 2712.77 | − 2852.63 |

| efnb3-pem | 1431.71 | − 6442.07 | 265.10 | − 32.51 | − 6967.42 | − 6999.94 |

| efnb3-nit | 1402.26 | − 6715.16 | 266.23 | − 57.71 | − 7070.77 | − 7128.49 |

| efnb3-iso | 1458.29 | − 7164.23 | 265.39 | − 73.15 | − 7494.71 | − 7567.87 |

| efnb3-eri | 1386.19 | − 6638.61 | 258.95 | − 59.69 | − 6981.71 | − 7041.40 |

| efnb3-rem | 1450.41 | − 6905.33 | 262.42 | − 67.83 | − 7315.57 | − 7383.40 |

| gm-ceph | 2417.10 | − 1441.59 | 270.79 | − 203.65 | − 3883.58 | − 4087.23 |

| gm-erg | 2372.72 | − 1369.77 | 271.24 | − 215.43 | − 3797.48 | − 4012.91 |

| gm-hyp | 2356.64 | − 1700.16 | 269.77 | − 264.99 | − 4042.52 | − 4307.51 |

| gm-rem | 2380.22 | − 1467.34 | 270.40 | − 187.003 | − 3954.07 | − 4141.07 |

| gb-ceph | 2432.24 | − 1402.48 | 275.34 | − 210.94 | − 3874.12 | − 4085.07 |

| gb-erg | 2384.55 | − 1273.36 | 267.13 | − 188.34 | − 3694.47 | − 3882.81 |

| gb-hyp | 2380.99 | − 1394.82 | 283.84 | − 164.54 | − 3832.21 | − 3996.76 |

| gb-rem | 2394.32 | − 1398.45 | 261.96 | − 151.07 | − 3902.64 | − 4053.71 |

Table 3.

Calculated interaction energies of protein–inhibitor complexes (kJ/mol)

| Complex | Eint−P | Eint−B | Eint−vdW | Eint−Ele | Eint−NB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| efnb2-pem | − 1139.78 | − 116.4 | − 552.78 | 679.84 | 127.04 |

| efnb2-nit | − 1427.75 | − 101.97 | − 555.31 | 540.37 | − 10.32 |

| efnb2-iso | − 1376.24 | − 92.6 | − 571.57 | 562.78 | − 8.81 |

| efnb2-eri | − 1219.71 | − 78.71 | − 565.27 | 654.87 | 91.26 |

| efnb2-rem | − 1544.99 | − 99.08 | − 595.02 | 469.98 | − 125.06 |

| efnb3-pem | − 1280.97 | − 399.6 | − 54.55 | − 438.29 | − 6831.53 |

| efnb3-nit | − 1572.72 | − 397.36 | − 69.37 | − 562.04 | − 6970.1 |

| efnb3-iso | − 2009.35 | − 398.25 | − 89.45 | − 981.34 | − 7409.48 |

| efnb3-eri | − 1490.1 | − 406.38 | − 69.67 | − 478.94 | − 6885.61 |

| efnb3-rem | − 1887.6 | − 406.43 | − 101.79 | − 816.27 | − 7256.74 |

| gm-ceph | − 163.57 | − 4.11 | − 6.09 | − 173.72 | − 179.82 |

| gm-erg | − 41.96 | 3.77 | − 8.64 | − 56.45 | − 65.09 |

| gm-hyp | − 350.34 | 1.76 | − 65.07 | − 297.41 | − 362.47 |

| gm-rem | − 212.75 | 2.83 | 23.11 | − 231.66 | − 208.55 |

| gb-ceph | − 22.27 | − 6.54 | − 29.32 | − 51.83 | − 81.16 |

| gb-erg | 156.64 | − 7.32 | 2.51 | 158.99 | 161.51 |

| gb-hyp | 57.19 | 8.85 | 19.44 | 25.33 | 44.78 |

| gb-rem | − 41.67 | − 12.59 | 43.1 | − 67.8 | − 24.69 |

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling results

Pharmacophore modeling strategy is used for finding the top hit small molecules. There are two kinds of pharmacophore models: structure-based pharmacophore which derived from X-ray protein–ligand complex, and ligand-based pharmacophore which derived from the structure of the active compound [49]. Since two protein structures were obtained from homology modeling and did not have an experimental X-ray three-dimensional structure, for getting more reasonable results in this section, the ligand-based pharmacophore modeling was used. Therefore, the seven listed inhibitors were further considered for generating the ligand-based pharmacophore model. These pharmacophore models were predicted by ZINCPharmer and revealed six spatial features including (A) aromatic, (HD) hydrogen donor, (HA) hydrogen acceptor, (HP) hydrophobic, (P) positive ion, and (N) negative ion (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 7, the A ring, HD, HA, HP centroid, P, and N are represented in violet, white, yellow, green, blue, and red colors. In addition, the spatial location (x, y, z) with radius can be seen for each drug in Table 4. The highest number of non-covalent interactions was found for Hypericin with 28 interactions, followed by Cepharanthine with 18, Ergoloid with 16, Eriodictyol with 14, Pemirolast with 14, Isoniazid pyruvate with 10, and finally Nitrofurantoin with 10 non-covalent interactions are defined.

Fig. 7.

Ligand-based pharmacophore model of human efnb2, efnb3 receptors, and glycoprotein of NiV Malaysia and Bangladesh. Here, a represents pemirolast features, b nitrofurantoin, c isoniazid pyruvate, d eriodictyol, e cepharanthine, f ergoloid, and g hypericin

Table 4.

Pharmacophore modeling results of the screened compounds along with spatial location (x, y, z) and radius

| Drug name | Molecular formula | Pharmacophore class | x | y | z | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pemirolast | C10H8N6O | Aromatic | 0.36 | 0.38 | − 0.01 | 1.1 |

| Aromatic | 2.58 | − 0.52 | 0.01 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | − 3.56 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 1.1 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 4.41 | − 0.52 | 0.02 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 0.93 | 1.65 | − 0.01 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 3.16 | − 1.02 | 0.01 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 3.25 | 1.24 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.51 | 0.81 | 0.01 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 0.7 | − 2.08 | − 0.04 | 0.5 | ||

| Negative Ion | − 3.56 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.75 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 0.36 | 0.38 | − 0.01 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 2.58 | − 0.52 | 0.01 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 3.56 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 3.75 | 2.16 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Nitrofurantoin | C8H6N4O5 | Aromatic | − 2.37 | 0.63 | 0 | 1.1 |

| Hydrogen donor | 4.52 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 1.11 | 0.84 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.66 | − 2.27 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 3.64 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 5.67 | − 0.17 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.38 | − 1.96 | 0 | 0.5 | ||

| Positive Ion | − 4.52 | − 0.7 | 0 | 0.75 | ||

| Negative Ion | − 5.67 | − 0.17 | 0 | 0.75 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 2.37 | 0.63 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Isoniazid pyruvate | C9H9N3O3 | Aromatic | 2.87 | − 0.33 | − 0.01 | 1.1 |

| Hydrogen donor | − 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 1.9 | 1.1 | 0.11 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.05 | − 1.07 | − 0.08 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 0.51 | 2.39 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 2.73 | − 1.43 | − 1.39 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 2.68 | − 1.83 | 0.87 | 0.5 | ||

| Negative Ion | − 2.73 | − 1.45 | − 0.21 | 0.75 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 2.87 | − 0.33 | − 0.01 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 4.4 | 0.86 | 0.06 | 1 | ||

| Eriodictyol | C15H12O6 | Aromatic | − 3.29 | − 0.09 | 0.35 | 1.1 |

| Aromatic | 3.02 | − 0.58 | − 0.03 | 1.1 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | 4.35 | 1.83 | − 0.03 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | 4.49 | − 2.91 | − 0.03 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 4.49 | − 0.35 | − 2.12 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 6.01 | − 0.53 | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 0.26 | − 0.78 | − 0.03 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 2 | 2.94 | − 0.13 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.35 | 1.83 | − 0.03 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.49 | − 2.91 | − 0.03 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.49 | − 0.35 | − 2.12 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 6.01 | − 0.53 | 0.2 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 3.29 | − 0.09 | 0.35 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 3.02 | − 0.58 | − 0.03 | 1 | ||

| Cepharanthine | C37H38N2O6 | Aromatic | − 3.45 | − 0.11 | 1.12 | 1.1 |

| Aromatic | 0.48 | − 2.58 | − 0.41 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | − 0.31 | 2.93 | − 0.27 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | 4.2 | 1.48 | 0.2 | 1.1 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.74 | 1.13 | − 2.24 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.08 | − 3.35 | − 1.05 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 1.26 | − 1.17 | 2.37 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 3.25 | − 0.96 | 3.7 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 2.22 | − 3.08 | − 0.15 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.5 | 4.19 | − 0.21 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 3.45 | − 0.11 | 1.12 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 0.48 | − 2.58 | − 0.41 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 0.31 | 2.93 | − 0.27 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 4.2 | 1.48 | 0.2 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 4.68 | 0.59 | − 3.6 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 5.51 | − 3.19 | − 1.28 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 2.93 | − 3.38 | − 1.35 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 5.11 | 4.94 | 0.84 | 1 | ||

| Ergoloid | C35H41N5O5 | Hydrogen donor | 0.28 | 0.78 | − 0.72 | 0.5 |

| Hydrogen donor | 8.91 | − 1.34 | − 0.74 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | 3.24 | − 2.05 | − 0.27 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 1.79 | − 0.43 | 1.3 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 1.3 | 2.08 | 0.79 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 1.42 | 1.62 | 0.67 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 1.79 | − 0.43 | 1.3 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 6.13 | 1.9 | 0.21 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 2.01 | 0.14 | − 2.45 | 0.5 | ||

| Positive Ion | 8.91 | − 1.34 | − 0.74 | 0.75 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 3.29 | − 2.42 | 1.1 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 0.91 | 2.99 | − 1.78 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 5.79 | − 1.17 | 0.06 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 4.18 | 0.58 | 3.4 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 7.17 | − 2.18 | − 0.55 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 7.27 | 0.65 | 0.06 | 1 | ||

| Hypericin | C30H16O8 | Aromatic | 0 | 1.23 | 0 | 1.1 |

| Aromatic | 0 | − 1.23 | 0 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | − 2.11 | 0 | − 0.01 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | 2.11 | 0 | 0.01 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | − 2.15 | − 2.43 | − 0.06 | 1.1 | ||

| Aromatic | 2.15 | − 2.43 | 0.06 | 1.1 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 4.88 | 0.04 | − 0.07 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | 4.88 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 1.08 | − 4.93 | − 0.25 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | 1.07 | − 4.93 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | − 4.92 | − 2.48 | − 0.15 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen donor | 4.91 | − 2.48 | 0.15 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.88 | 0.04 | − 0.07 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.88 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 1.08 | − 4.93 | − 0.25 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 1.07 | − 4.93 | 0.25 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.92 | − 2.48 | − 0.15 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.91 | − 2.48 | 0.15 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | − 4.75 | 2.53 | − 0.24 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrogen acceptor | 4.75 | 2.52 | 0.24 | 0.5 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 0 | 1.23 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 0 | − 1.23 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 2.11 | 0 | − 0.01 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 2.11 | 0 | 0.01 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 2.15 | − 2.43 | − 0.06 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 2.15 | − 2.43 | 0.06 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | − 0.83 | 4.78 | 1.33 | 1 | ||

| Hydrophobic | 0.84 | 4.78 | − 1.33 | 1 |

Molecular docking calculations and validation

The molecular docking simulations were performed based on the procedure that was mentioned in the previous section using three in silico tools; AutoDock Vina, SwissDock, and HDock server. The purpose of screening 14 protein-inhibitor complexes was based on identifying the least interaction binding energy between the receptor and the ligand molecule which reflects a stable mode. Docking scores of screened complexes are displayed in Table 5. Re-docking of the seven suggested drugs against the human efnb2, efnb3 receptors, and glycoprotein of NiV Malaysia and Bangladesh using SwissDock and HDock had mostly similar results as the previous results with Autodock Vina software. Based on Randhawa et al. (2022) research paper to identify the multi-target inhibitors for the Nipah virus, the antiviral drug remdesivir with DB14761 DrugBank accession number was used as the positive control for molecular docking studies [50, 51]. As seen in Table 5, remdesivir (abbreviated as rem) was docked into all seven viral proteins with the previously mentioned parameters and processes. Remdesivir binds to efnb2 protein with − 6.8 kcal/mol binding affinity, and it is just stronger than one complex (efnb2-iso). remdesivir binds to efnb3 (− 7.9 kcal/mol); however, three complexes (efnb3-pem, efnb3-nit, and efnb3-iso) bind more firmly. rem binds to gm (− 7.2 kcal/mol), and gb (− 7.1 kcal/mol), but other complexes are stronger. Therefore, the comparatively poor affinity is attributed to the weak intermolecular interactions between remdesivir and NiV glycoproteins. Since remdesivir was not able to bind efficiently to the targets, we did not perform its interaction details in the next section.

Table 5.

Molecular docking results of complexes and the evaluation of the docking performance

| Complexes | Autodock Vina | Binding affinity (kcal/mol) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissDock | HDock | ||

| efnb2-pem | − 7.1 | − 7.29 | − 124.41 |

| efnb2-nit | − 6.8 | − 6.89 | − 130.02 |

| efnb2-iso | − 5.9 | − 6.47 | − 119.82 |

| efnb2-eri | − 8.1 | − 6.6 | − 147.74 |

| efnb2-rem (control) | − 6.8 | ||

| efnb3-pem | − 7.3 | − 7.32 | − 128.28 |

| efnb3-nit | − 6.5 | − 7.08 | − 136.49 |

| efnb3-iso | − 5.8 | − 6.75 | − 119.19 |

| efnb3-eri | − 8 | − 7.36 | − 148.67 |

| efnb3-rem (control) | − 7.9 | ||

| gm-Ceph | − 10.1 | − 6.9 | − 229.15 |

| gm-erg | − 10.1 | − 7.7 | − 206.73 |

| gm-hyp | − 9.6 | − 7.29 | − 248.44 |

| gm-rem (control) | − 7.2 | ||

| gb-Ceph | − 9.2 | − 6.5 | − 225.9 |

| gb-erg | − 9.4 | − 6.89 | − 211.37 |

| gb-hyp | − 9.6 | − 7.6 | − 243.6 |

| gb-rem (control) | − 7.1 | ||

In Sen et al. [13] study the number of 146 small molecule inhibitors were considered against the nine Nipah virus proteins including glycoprotein, fusion, and matrix. On the 13 top shortlisted small molecule ligands the molecular dynamics simulations were carried out for checking the stability and estimating binding strengths. The small molecules with the highest confidence to bind different NiV proteins were mentioned for comparison with our results. g-ZINC04580552 with − 8.97 kcal/mol, g-ZINC63857604 with − 8.76 kcal/mol, g-ZINC63411510 with − 8.73 kcal/mol, g-ZINC65407076 with − 8.64 kcal/mol, and g-ZINC72264974 with − 8.57 kcal/mol [13]. Additionally, Randhawa et al. (2022) calculated the binding affinity values of some chemical and phytochemical inhibitors against NiV-fusion and NiV-glycoprotein including f-RSV604 with − 8.6 kcal/mol, g-RSV604 with − 8.8 kcal/mol, f-AC1MH6FW (− 8.2 kcal/mol), g-AC1MH6FW (− 8.3 kcal/mol), f-CARS0358 (− 7.9 kcal/mol), g-CARS0358 (− 8.0 kcal/mol), f-CARS0394 (− 7.8 kcal/mol), g-CARS0394 (− 7.8 kcal/mol), f-24-Olefinic sterol (− 7.8 kcal/mol), g-24-Olefinic sterol (− 8.2 kcal/mol), f-Naringin (− 8 kcal/mol), g-Naringin (− 7.9 kcal/mol), f-17-O-Acetyl-nortetraphyllicine (− 7.8 kcal/mol), and g-17-O-Acetyl-nortetraphyllicine (− 7.8 kcal/mol). Compared to these computational works, our analysis results are stronger and show firmly drug-protein interactions and could be repurposed as inhibitors of the Nipah virus.

In Smith et al. [52] repurposing therapeutics study for Coronavirus nCov-2019, using the world’s most powerful supercomputer, SUMMIT, for developing a computational model of the spike protein interacting with the human ACE2 receptor. ACE2 is an entry point for viral infection in humans. This study was performed in three phases: structural modeling, molecular simulations (ensemble building), and molecular docking. As a result, the top four compounds including pemirolast, isoniazid pyruvate, nitrofurantoin, and eriodictyol were identified through having stronger interactions with the ACE2 receptor than the S protein. Therefore, the mentioned drugs were known as specific ACE2 inhibitors, and in this work were used for repurposing against the efnb2 and efnb3 human NiV receptors. The AutoDock Vina binding affinities against ACE2 receptor were calculated as pemirolast (− 7.4 kcal/mol), isoniazid pyruvate (− 7.3 kcal/mol), nitrofurantoin (− 7.2 kcal/mol), and eriodictyol (− 7.1 kcal/mol) and compared to our results for efnb2/efnb3-pem/nit/iso/eri complexes (Table 5), the values are close and it seems these drugs could be effective for anti-NiV treatment experimentally. In the continuation of this study, three top hit inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with their binding scores were mentioned. Cepharanthine with − 6.6 kcal/mol, ergoloid with − 6.3 kcal/mol, and hypericin with − 6.9 kcal/mol can cause favorable interaction which blocks host recognition. These three potent inhibitors were used in our study against NiV glycoprotein, which has a similar role as spike protein for viral entry and extending infections. As shown in Table 5, the binding affinity of NiV proteins-ceph/erg/hyp can be represented as potent NiV inhibitors [52]. The candidate protein-inhibitor complexes were obtained from Table 3, efnb2-pem (− 7.1 kcal/mol), efnb3-iso (− 5.8 kcal/mol), gm-hyp (− 9.6 kcal/mol), gb-ceph (− 9.2 kcal/mol), are considered for their binding affinity scores.

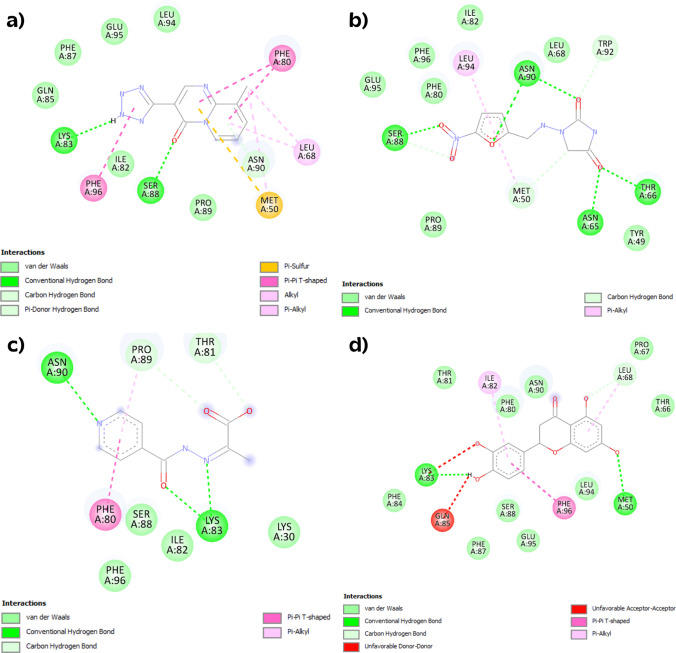

Protein–ligand interaction details

The best docking pose of each protein-inhibitor complex was obtained from molecular docking. The binding site of the suggested drugs with EFNB2, EFNB3, and Malaysia and Bangladesh Glycoprotein were evaluated. As observed in Figs. 8, 9, 10, the 2D diagrams of docked complexes, from Autodock Vina software, investigate the main residues in protein–ligand interactions using Discovery Studio Visualizer. Moreover, 2D diagrams from two other docking servers are shown in Supplementary Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. In the efnb2-pem complex (Fig. 8a), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, π-sulfur, π-π T-shaped, alkyl, and π-alkyl interactions were observed. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Leu94, Glu95, Phe87, Gln85, Lys83, Phe96, Ile82, Ser88, Pro89, Met50, Asn90, Leu68, Phe80. In the efnb2-nit complex (Fig. 8b), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, and π-alkyl interactions were seen. Residues contained in the intermolecular interaction include Trp92, Leu68, Asn90, Leu94, Ile82, Phe96, Phe80, Glu95, Ser88, Pro89, Met50, Asn65, Tyr49, Thr66. In the efnb2-iso complex (Fig. 8c), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, π-π T-shaped, and π-alkyl were detected. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Thr81, Pro89, Asn90, Phe80, Ser88, Phe96, Ile82, Lys83, Lys30. In the efnb2-eri complex (Fig. 8d), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, unfavorable donor-donor, unfavorable acceptor-acceptor, π-π T-shaped, and π-alkyl interactions were observed. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Thr66, Leu68, Pro67, Asn90, Phe80, Ile82, Thr81, Lys83, Gln85, Phe84, Phe87, Ser88, Glu95, Phe96, Leu94, Met50. In the efnb3-pem complex (Fig. 9a), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, and π-alkyl interactions were observed. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Asn71, Asn95, Phe101, His99, Glu100, Glu91, Gln90, Ser93, Lys88, Ile87, Phe85. In the efnb3-nit complex (Fig. 9b), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, and carbon hydrogen bond were seen. Residues contained in the intermolecular interaction include Tyr92, Gln90, Glu91, Ser93, Asn95, Pro94, Phe101, Glu100, His99, Ile87, Phe85, Thr86. In the efnb3-iso complex (Fig. 9c), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, and carbon hydrogen bond were detected. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Asn71, Leu73, Phe85, Ile87, Phe101, Gln90, Glu91, Asn95, Gly98, Glu100, His99, Ser93. In the efnb3-eri complex (Fig. 9d), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, and π-π T-shaped interactions were observed. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Phe89, Gln90, Phe101, Glu100, His99, Leu73, Leu72, Asn71, Phe85, Asn95, Ser93, Ile87, Lys88. In the gm-ceph complex (Fig. 10a), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, π-π stacked, π-π T-shaped, alkyl, and π-alkyl interactions were seen. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Trp373, Tyr220, His150, Phe327, Pro310, Lys429, Tyr377, Gly375, Val376, Asp88, Glu448, Gln428, Tyr450, Ser110, Leu174. In the gb-ceph complex (Fig. 10b), van der Waals interaction, π-anion, π-π stacked, and π-alkyl interactions were shown. Residues contained in the intermolecular interaction include Tyr450, Ser110, Gln428, Glu448, Tyr377, Pro310, Lys429, Phe327, His150, Asp88, Tyr220, Asp171, Ile173, Trp373, Leu174. In the gm-erg complex (Fig. 10c), van der Waals interaction, carbon hydrogen bond, π-anion, π-sigma, π-π stacked, alkyl and π-alkyl interactions were detected. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Tyr450, Glu448, Tyr220, Pro310, Trp373, Ile173, Leu174, His150, Ser110, Arg111, Asp171, Tyr149, Arg105, Asp88, Gly375, Phe327, Lys429, Tyr377, Val376, Gln428. In the gb-erg complex (Fig. 10d), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, π-anion, π-sigma, and π-alkyl interactions were shown. Residues contained in the intermolecular interaction include Asp88, Glu448, Tyr450, Lys429, Tyr377, Trp373, Gln428, Phe327, Leu174, Val376, Leu174, Asp171, Gly375, Gln359, Glu374, Ala401, Ile173, Pro310, Tyr220, His150. In the gm-hyp complex (Fig. 10e), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, π-anion, π-π stacked, and π-alkyl interactions were detected. Residues involved in the intermolecular interaction include Tyr220, Lys429, Pro310, Tyr377, Phe327, Val376, Gly375, Gln428, Asp88, His150, Tyr149, Arg105, Asp171, Leu174, Ser110. Finally, in the gb-hyp complex (Fig. 10f), van der Waals interaction, conventional hydrogen bond, carbon hydrogen bond, π-anion, π-π stacked, and π-alkyl interactions were observed. Residues contained in the intermolecular interaction include Ser110, Leu174, Asp171, Lys105, Asp88, Leu103, Tyr149, Arg117, His150, Lys429, Pro310, Tyr377, Phe327, Val376, Gly375. In order to compare two NiV Malaysia and Bangladesh strains of glycoprotein, the van der Waals interactions were discussed. As shown in Fig. 10a, b) four (Tyr220, Val376, Gln428, Tyr450), and eleven (Tyr377, Pro310, Lys429, Phe327, Tyr220, Asp171, Ile173, Trp373, Leu174, Ser110, Gln428) van der Waals interactions were observed in gm-ceph and gb-ceph complexes, respectively. In Fig. 10c, d) thirteen (Arg105, Tyr149, Arg111, Ile173, Trp373, Pro310, Tyr220, Tyr450, Gln428, Val376, Tyr377, Phe327, Gly375), and fifteen (Glu374, Ile173, Pro310, Tyr220, His150, Tyr450, Tyr377, Trp373, Gln428, Phe327, Leu174, Val376, Asp171, Gly375, Gln359) van der Waals interactions in gm-erg and gb-erg complexes, and in Fig. 10e, f) nine (Tyr220, Tyr149, Arg105, Asp171, Leu174, Ser110, Gly375, Val376, Phe327), and eight (Phe327, Val376, Ser110, Leu174, Lys105, Leu103, Tyr149, Arg117) van der Waals interactions in gm-hyp and gb-hyp were evaluated. The candidate protein-inhibitor complexes from previous sections were evaluate based on the van der Waals interaction values; efnb2-pem (6), efnb3-iso (8), gm-hyp (9), and gb-ceph (11).

Fig. 8.

2D diagram intermolecular interactions resulted from Autodock Vina, a efnb2-pem, b efnb2-nit, c efnb2-iso, and d efnb2-eri complexes

Fig. 9.

2D diagram intermolecular interactions resulted from Autodock Vina, a efnb3-pem, b efnb3-nit, c efnb3-iso, and d efnb3-eri complexes

Fig. 10.

2D diagram intermolecular interactions resulted from Autodock Vina, a gm-ceph, b gb-ceph, c gm-erg, d gb-erg, e gm-hyp, and f gb-hyp complexes

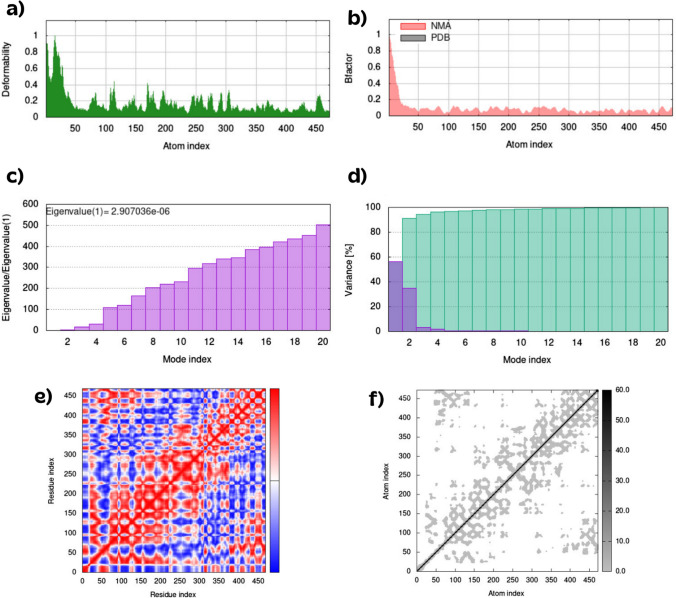

Molecular dynamics analysis

A recent study using molecular dynamics to identify secretory proteins as novel targets for temozolomide in glioblastoma multiforme motivated us to evaluate the docked complexes using the iMODS [53]. Figures 11, 12, 13, 14 illustrate how deformability, B-factor, eigenvalues, variance, covariance map, and elastic network were determined for efnb2-pem, efnb3-iso, gm-hyp, and gb-ceph complexes. The deformability and B-factor give the mobility profiles of the complexes. The main-chain of deformability measures the deformation of each protein residue. Figures 11a, 12a, 13a, 14a illustrate the highest peaks corresponding to regions of proteins with high deformability. The B-factor graphs provide a comparison between the normal mode analysis and the PDB field of the complexes. Since many PDB files of averaged NMR models contain no B-factors, the B-factor column gives an averaged RMS (Figs. 11b, 12b, 13b, 14b). The eigenvalue and the variance are linked to each normal mode. The eigenvalue value is related to the energy required to deform the complex, and the lower the value, the easier the deformation (Figs. 11c, 12c, 13c, 14c). The candidate protein-inhibitor complex eigenvalues are: efnb2-pem (5.31), efnb3-iso (6.11), gm-hyp (2.9), and gb-ceph (2.97). The variance-colored graphs are depicted in Figs. 11d, 12d, 13d, 14d, show the individual (red) and cumulative (green) variances. Covariance matrix indicates correlations among residues in a complex. The red color shows a decent correlation between residues, whereas the white color indicates uncorrelated motion. Furthermore, the blue color illustrates anticorrelations. The superior of the correlation, the better complex (Figs. 11e, 12e, 13e, 14e). The elastic maps of the complexes define the associations between the atoms, where the darker-gray portions specify stiffer portions (Figs. 11f, 12f, 13f, 14f).

Fig. 11.

Outputs of molecular dynamic simulations for efnb2-pem complex, a deformability b B-factor plot c eigenvalue d variance plot e covariance map and f elastic network model

Fig. 12.

Outputs of molecular dynamic simulations for efnb3-iso complex, a deformability b B-factor plot c eigenvalue d variance plot e covariance map and f elastic network model

Fig. 13.

Outputs of molecular dynamic simulations for gm-hyp complex, a deformability b B-factor plot c eigenvalue d variance plot e covariance map and f elastic network model

Fig. 14.

Outputs of molecular dynamic simulations for gb-ceph complex, a deformability b B-factor plot c eigenvalue d variance plot e covariance map and f elastic network model

Conclusions

Large-scale epidemics of highly pathogenic viruses always occur in human populations. In addition, virus genomic mutations complicate the situation further. In this research, annealing simulations, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics were used to identify possible inhibitors of the Malaysia and Bangladesh main strains of Nipah virus glycoprotein with their Ephrin-B2 and Ephrin-B3 receptors. It is the first study to assess the interactions between a druggable NiV glycoprotein from two main strains, Ephrin-B2 and Ephrin-B3 human receptors, with seven antiviral small molecules that showed efficacy in a clinical trial for the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The results of annealing simulations showed negative values -indicating stable adsorption- from potential energy, van der Waals interaction, electrostatic energy, etc. Moreover, this simulation is described as a productive method to evaluate both intramolecular and intermolecular interaction energies in the stable form of the complexes. As a result of the docking simulations, we found that the complexes had the highest binding affinities compared to other NiV inhibitors, including the antiviral drug Remdesivir, and had higher potential docking results than SARS-CoV-2. According to our study, efnb2-pemirolast, efnb3-isoniazid pyruvate, gm-hypericin, and gb-cepharanthine are promising compounds compared with previous experimental and/or computational studies for anti-NiV treatments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

ME and MA wrote the main manuscript text, prepared all figures and reviewed the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ang BSP, Lim TCC, Wang L. Nipah virus infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2018 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01875-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arunkumar G, Chandni R, Mourya DT, et al. Outbreak investigation of Nipah virus disease in Kerala, India, 2018. J Infect Dis. 2019;219:1867–1878. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mire CE, Satterfield BA, Geisbert JB, et al. Pathogenic differences between Nipah virus Bangladesh and Malaysia strains in primates: implications for antibody therapy. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30916. doi: 10.1038/srep30916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh RK, Dhama K, Chakraborty S, et al. Nipah virus: epidemiology, pathology, immunobiology and advances in diagnosis, vaccine designing and control strategies—a comprehensive review. Vet Q. 2019;39:26–55. doi: 10.1080/01652176.2019.1580827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L-F, Anderson DE. Viruses in bats and potential spillover to animals and humans. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;34:79–89. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerry RG, Malik S, Redda YT, et al. Nano-based approach to combat emerging viral (NIPAH virus) infection. Nanomedicine. 2019;18:196–220. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rima B, Balkema-Buschmann A, Dundon WG, et al. ICTV virus taxonomy profile: paramyxoviridae. J Gen Virol. 2019;100:1593–1594. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.001328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelissier R, Iampietro M, Horvat B. Recent advances in the understanding of Nipah virus immunopathogenesis and anti-viral approaches. F1000Res. 2019;8:1763. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.19975.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mougari S, Gonzalez C, Reynard O, Horvat B. Fruit bats as natural reservoir of highly pathogenic henipaviruses: balance between antiviral defense and viral tolerance interactions between henipaviruses and their natural host, fruit bats. Curr Opin Virol. 2022;54:101228. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2022.101228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisbert TW, Bobb K, Borisevich V, et al. A single dose investigational subunit vaccine for human use against Nipah virus and Hendra virus. NPJ Vaccines. 2021;6:23. doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00284-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jensen MR, Yabukarski F, Communie G, et al. Structural description of the Nipah virus phosphoprotein and its interaction with STAT1. Biophys J. 2020;118:2470–2488. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amaya M, Broder CC. Vaccines to emerging viruses: Nipah and Hendra. Annu Rev Virol. 2020;7:447–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-021920-113833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sen N, Kanitkar TR, Roy AA, et al. Predicting and designing therapeutics against the Nipah virus. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoneda M, Guillaume V, Sato H, et al. The nonstructural proteins of Nipah virus play a key role in pathogenicity in experimentally infected animals. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang Z, Amaya M, Addetia A, et al. Architecture and antigenicity of the Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein. Science. 2022;375:1373–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.abm5561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauser N, Gushiken AC, Narayanan S, et al. Evolution of Nipah virus infection: past, present, and future considerations. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2021;6:24. doi: 10.3390/tropicalmed6010024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patch JR, Crameri G, Wang L-F, et al. Quantitative analysis of Nipah virus proteins released as virus-like particles reveals central role for the matrix protein. Virol J. 2007;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watkinson RE, Lee B. Nipah virus matrix protein: expert hacker of cellular machines. FEBS Lett. 2016;590:2494–2511. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowden TA, Aricescu AR, Gilbert RJC, et al. Structural basis of Nipah and Hendra virus attachment to their cell-surface receptor ephrin-B2. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:567–572. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Füller T, Korff T, Kilian A, et al. Forward EphB4 signaling in endothelial cells controls cellular repulsion and segregation from ephrinB2 positive cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2461–2470. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawes BE, Kalveram B, Ikegami T, et al. Favipiravir (T-705) protects against Nipah virus infection in the hamster model. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7604. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25780-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lo MK, Jordan R, Arvey A, et al. GS-5734 and its parent nucleoside analog inhibit Filo-, Pneumo-, and Paramyxoviruses. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43395. doi: 10.1038/srep43395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hotard AL, He B, Nichol ST, et al. 4’-Azidocytidine (R1479) inhibits henipaviruses and other paramyxoviruses with high potency. Antiviral Res. 2017;144:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramsay RR, Popovic-Nikolic MR, Nikolic K, et al. A perspective on multi-target drug discovery and design for complex diseases. Clin Transl Med. 2018;7:3. doi: 10.1186/s40169-017-0181-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang W, Pei J, Lai L. Computational multitarget drug design. J Chem Inf Model. 2017;57:403–412. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Viana J, O, Félix MB, Maia M dos S,, et al. Drug discovery and computational strategies in the multitarget drugs era. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2018 doi: 10.1590/s2175-97902018000001010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma XH, Shi Z, Tan C, et al. In-silico approaches to multi-target drug discovery: computer aided multi-target drug design, multi-target virtual screening. Pharm Res. 2010;27:739–749. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.WwPDB: 2VSM. https://www.wwpdb.org/pdb?id=pdb_00002vsm. Accessed 7 Feb 2023

- 29.WwPDB: 3D12. https://www.wwpdb.org/pdb?id=pdb_00003d12. Accessed 7 Feb 2023

- 30.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, et al. UCSF Chimera–a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clark K, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, et al. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D67–72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waterhouse A, Bertoni M, Bienert S, et al. SWISS-MODEL: homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W296–W303. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shamsi A, Mohammad T, Anwar S, et al. Potential drug targets of SARS-CoV-2: from genomics to therapeutics. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;177:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterling T, Irwin JJ. ZINC 15–ligand discovery for everyone. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55:2324–2337. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, Materials Studio software, Version 20.1.0.2728, San Diego: Dassault Systèmes (2020)

- 36.Rappe AK, Casewit CJ, Colwell KS, et al. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10024–10035. doi: 10.1021/ja00051a040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koes DR, Camacho CJ. ZINCPharmer: pharmacophore search of the ZINC database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W409–W414. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61:3891–3898. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c00203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gasteiger J, Marsili M. Iterative partial equalization of orbital electronegativity—a rapid access to atomic charges. Tetrahedron. 1980;36:3219–3228. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(80)80168-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. SwissDock, a protein-small molecule docking web service based on EADock DSS. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:W270–W277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grosdidier A, Zoete V, Michielin O. Fast docking using the CHARMM force field with EADock DSS. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:2149–2159. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan Y, Zhang D, Zhou P, et al. HDOCK: a web server for protein-protein and protein-DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W365–W373. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.BIOVIA, Dassault Systèmes, Discovery studio visualizer software, version 4.0, San Diego: Dassault Systèmes (2012).

- 45.López-Blanco JR, Aliaga JI, Quintana-Ortí ES, Chacón P. iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W271–W276. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guarnieri F, Kulp JL, Jr, Kulp JL, 3rd, Cloudsdale IS. Fragment-based design of small molecule PCSK9 inhibitors using simulated annealing of chemical potential simulations. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225780. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang F, Wang Z, Vijver MG, Peijnenburg WJGM. Probing nano-QSAR to assess the interactions between carbon nanoparticles and a SARS-CoV-2 RNA fragment. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;219:112357. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo MK, Feldmann F, Gary JM, et al. Remdesivir (GS-5734) protects African green monkeys from Nipah virus challenge. Sci Transl Med. 2019 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kutlushina A, Khakimova A, Madzhidov T, Polishchuk P. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling using novel 3D pharmacophore signatures. Molecules. 2018;23:3094. doi: 10.3390/molecules23123094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Randhawa V, Pathania S, Kumar M. Computational identification of potential multitarget inhibitors of Nipah virus by molecular docking and molecular dynamics. Microorganisms. 2022;10:1181. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms10061181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, et al. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D668–D672. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith M, Smith JC. Repurposing therapeutics for COVID-19: supercomputer-based docking to the SARS-CoV-2 viral spike protein and viral spike protein-human ACE2 interface. ChemRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv.11871402.v4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sumera, Anwer F, Waseem M, et al. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics studies reveal secretory proteins as novel targets of temozolomide in glioblastoma multiforme. Molecules. 2022;27:7198. doi: 10.3390/molecules27217198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.