Abstract

Background

Pediatric cancer incidence in Mexico is ~160/million/year with leukemias making 49.8% of the cases. While survival rates have been reported in various Mexican studies, no data is available from the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital‐HITO, a nonprofit private institution specialized exclusively in comprehensive pediatric oncology care in the country that closely follows high‐income countries' advanced standards of cancer care.

Aim

To determine overall survival (OS) and relapse‐free survival (RFS) in patients treated at HITO between December 2013 and February 2018.

Methods and results

Secondary analysis of data extracted from medical records. It included 286 children aged 0–17 years diagnosed with various cancers grouped into three categories based on location: (1) Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), (2) tumors within the central nervous system (TWCNS), and (3) tumors outside the CNS (TOCNS). OS and RFS rates for patients who completed 1 (n = 230) and 3 (n = 132) years of follow‐up after admission were computed by sex, age, and cancer location, and separately for a subsample (1‐year = 191, 3‐years = 110) who fulfilled the HITO criteria (no prior treatment, underwent surgery/chemotherapy when indicated, and initiated therapy). TOCNS accounted for 45.1%, but ALL was the most frequent single diagnosis with 28%. Three‐year OS for patients with ALL, TWCNS, and TOCNS who fulfilled the HITO criteria were 91.9%, 86.7%, and 79.3%, respectively; for 3‐year RFS these were 89.2%, 60%, and 72.4%. Boys showed slightly higher OS and RFS, but no major differences or trends were seen by age group.

Conclusion

This study sets a relevant reference in terms of survival and relapse for children with cancer in Mexico treated at a private oncology center that uses a comprehensive and integrated therapeutic model.

Keywords: epidemiology, hematology, oncology, pediatric cancer, relapse, survival

1. INTRODUCTION

Pediatric cancer is a major challenge in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC), where 80% of the cases occur, 1 and it is becoming an emergent global health concern. 2 , 3

At present, cancer is the most common cause of death in children aged 5–14 years in Mexico. 4 , 5 Data from the National Council for the Prevention and Treatment of Childhood Cancer, a network comprising 55 public certified hospitals nationwide, revealed an incidence of pediatric cancer (0–17 years) of 156.9 per million inhabitants in 2012. 6 Leukemia accounted for 49.8% of all pediatric cancers followed by lymphomas (9.9%), and central nervous system (CNS) tumors (9.4%) during the 2007–2012 period, 4 , 6 with an incidence increasing over time, particularly that of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). 7

Several initiatives have been implemented in Mexico to establish a pediatric cancer control agenda, including the involvement of the “Seguro Popular,” the government‐funded public medical insurance program. However, efforts have faced various challenges associated with insufficient funding, ranging from limited infrastructure to poorly trained staff. 8

Child survival from cancer in Mexico has improved considerably due to better public health interventions; yet, survival is still half of the rates observed in high‐income countries (HIC). 5 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12

While survival from pediatric cancer has been linked to various factors, including genetic susceptibility, age at diagnosis, type of hospital, nutritional status, and stage at diagnosis and treatment, 12 , 13 in resource‐limited settings substantial improvement in survival mostly relates to adherence to integrated pediatric cancer management protocols. 14

In this context, the aim of this study was to determine the overall survival (OS) and relapse‐free survival (RFS) rates for patients admitted to the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital (HITO), a specialized nonprofit private institution that closely follows advanced standards of cancer care followed in HIC.

Written permission to use, analyze, and publish the data was given by the HITO Ethics and Research Committee (ID: CEI‐2018‐005). Informed consent was not obtained, as this was a secondary data analysis. However, complete anonymity was maintained throughout the analysis and reporting process.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Study design

This was a retrospective secondary survival analysis of data extracted from medical records of pediatric patients treated for cancer at HITO. The study period lasted 50 months, starting from the hospital inauguration in December 2013 until February 2018. Standard diagnostic methods were followed as per disease condition and protocol recommendations, including imaging (radiography, ultrasound, bone scintigraphy, and CT‐PET‐MRI scans), pathology (immunohistochemistry panel, molecular pathology, cytospin CSF, FISH testing, and cytogenetics), and hematopathology (microscopy, high‐quality flow cytometry, and minimal residual disease testing) procedures.

2.2. Study setting

This study was carried out at a hospital located in the city of Querétaro, 200 km north of Mexico City. From the 74 pediatric cancer units in the country, this is the only hospital in Mexico exclusively focused on the treatment of pediatric cancer. 15 It is run and owned by the Mexican Telethon Foundation, which started providing pediatric rehabilitation services in 1997, and currently runs the largest rehabilitation system for children in the world.

When HITO initiated activities, it had a medical and paramedical staff of 260; by the end of the study period, it had 350. Pediatric subspecialists in oncology, neurosurgery, oncologic surgery, transplant medicine, critical and emergency medicine, anesthesiology, radiotherapy, and radiooncology are the core medical staff, but nephrologists, endocrinologists, hematologists, pathologists, urologists, and orthopedic specialists are also affiliated.

HITO's infrastructure and services include clinical, pathological, cytogenic/molecular biology, and hematological diagnostic labs along with diagnostic/follow‐up imaging. The hospital has 26 cubicles for ambulatory chemotherapy, an Eleckta® device for radiotherapy, a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation unit, and two fully equipped operating rooms. There is a 24/7 TRIAGE/shock area, intensive care unit (ICU), and blood bank. HITO also has an adjacent 74‐room building (Casa Teletón) that provides housing and food to caretakers during the critical stages of treatment.

The hospital has an inpatient capacity of 26 beds (four for ICU) that served a yearly average of 61 new patients in active therapy between 2014 and 2017 (2014 = 58, 2015 = 78, 2016 = 50, and 2017 = 58). Mean hospital bed occupancy rate within the last 5 years was 52%. Most patients (42%) are residents of Querétaro State, but patients also come from many other Mexican states, especially from neighboring Guanajuato (15%).

Care ranges from diagnostics to reintegration to daily life. Therapeutic services offered include oncological surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and bone marrow transplantation (BMT). During the period of stay at the hospital, patients and caregivers are accommodated in Casa Teletón to minimize dropouts and for early detection of complications. Caregivers receive continuous training in numerous courses and workshops regarding cancer management.

2.3. Study population

The study population comprised 305 children aged 0–17 years with new diagnosis of various types of cancers during the study period. However, the final sample with complete and accurate data for analysis included 286 patients (19 patients had inconsistent diagnostic and follow‐up dates). Each medical treatment given at the hospital followed advanced standardized protocols of care used in HICs that lead to the highest possible survival, such as those of the Children's Oncology Group (COG) of the United States for solid tumors, 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 and the Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) for leukemia in pediatrics. 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 These are the most experienced organizations in the world in clinical development of new therapeutics for children and adolescents. In fact, with two exceptions (i.e., DFCI protocol for ALL and St. Jude's 99 protocol for medulloblastoma), all other conditions followed COG protocols (see Supplementary Table S1). There were no ongoing research trials during the study period. Local Mexican protocols were not used, as they have not demonstrated any increase in survival rates. For all acute leukemias, antibacterial prophylaxis with levofloxacin was routinely used to reduce the incidence of bacterial infections, avoiding mortality due to sepsis during the induction phase. For all cancers, when patients presented fever and neutropenia, the antibiotic treatment protocol (mostly fourth‐generation cephalosporins) was followed within the first hour of fever. Central venous access catheters (acute or long‐term) were used throughout chemotherapy; such devices were managed by a specialized catheter clinic. Follow up care was given every month during the first year after treatment, and three or four times per year thereafter to determine the recurrence of cancer.

2.4. Data extraction

Data was extracted from clinical records. Due to the relatively small samples available for individual malignancies, cancers were classified into three major groups based on its location: (I) ALL (n = 80); (II) tumors within the central nervous system (TWCNS) (n = 55) including astrocytomas 23, medulloblastomas 11, ependymomas 6, adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas 4, intracranial germ cell tumors 4, atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors 2, neuronal and mixed neuronal‐glial tumors 2, non‐medulloblastoma embryonal tumors 1, choroid plexus carcinomas 1, and tumors of the pineal region 1; and (III) tumors outside the CNS (TOCNS) (n = 132) including osteosarcomas 25, retinoblastomas 24, non‐rhabdomyosarcoma soft‐tissue sarcomas 16, rhabdomyosarcomas 12, extracranial germ cell tumors 12, neuroblastomas 10, Langerhans cell histiocytosis 9, Ewing's sarcomas 8, Wilms tumors 8, rare tumors 4, hepatoblastomas 3, and hepatocellular carcinomas 1.

Information extracted included patients' sex, age, occurrence of relapse, and status at the time of the study (i.e., death during treatment, under treatment, post‐therapy follow‐up, and abandoned). Children who received a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) were not analyzed (n = 22).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Frequencies and percentages were used to depict basic characteristics of the study population. RFS was defined as the time from diagnosis to disease progression. OS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death from any cause. RFS and OS as functions of time since diagnosis, were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier, 31 stratifying by sex, age group (0–4, 5–9, and 10–17 years), and cancer location in patients who completed one (n = 230) and three (n = 132) years of follow‐up after admission. Kaplan–Meier plots were used to depict these graphically.

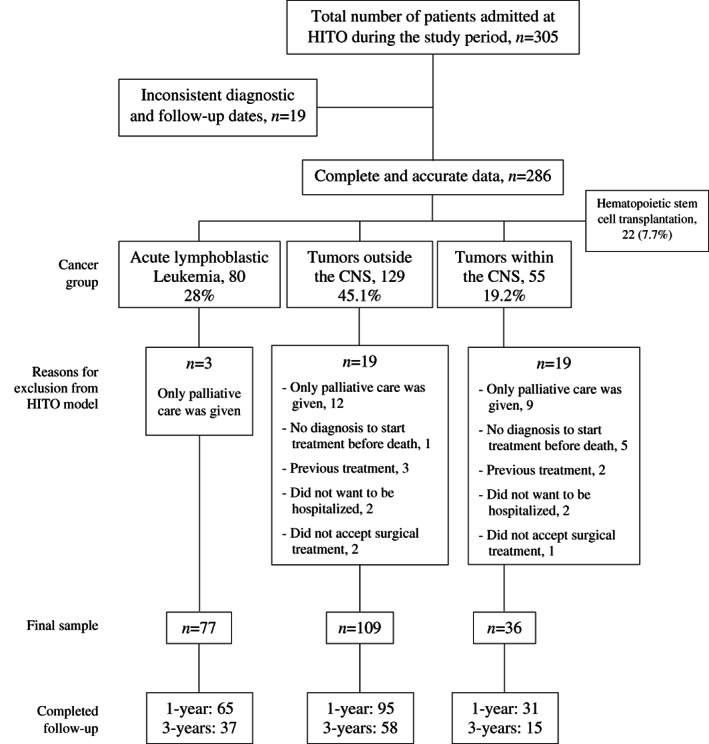

A separate analysis was conducted with patients who fulfilled the HITO criteria (i.e., no prior treatment at admission, underwent surgical/chemotherapy treatment when indicated, and initiated oncologic treatment at HITO). This was considered crucial to accurately portray the OS and RFS of patients treated with the HITO model of care, as some patients only received palliative care due to their advance stage (e.g., several patients died within few days or weeks after admission). For ALL, three patients were excluded (reason: only palliative care was given) leaving 77 available for analysis (80/77 = 96.2%). For TWCNS, 19 children had to be excluded (reasons: only palliative care was given 9, no diagnosis available to start treatment before death 5, previous treatment 2, did not want to be hospitalized 2, and did not accept surgical treatment 1), leaving 36 patients available (36/55 = 65.4%). For TOCNS, 20 patients were excluded (reasons: only palliative care was given 12, previous treatment 3, did not want to be hospitalized 2, did not accept surgical treatment 2, and no diagnosis available to start treatment before death 1) leaving 109 available (109/129 = 84.5%). Figure 1 represents a flow‐chart showing the distribution of patients admitted to the hospital during the study period by cancer group, number of patients with complete data excluded from the HITO model, and final number of patients who completed the 1‐ and 3‐years follow‐up period (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow‐chart showing the distribution of patients admitted to the hospital during the study period by cancer group, the number of patients with complete data excluded from the HITO model, and the final number of patients who completed the 1‐ and 3‐years follow‐up periods at the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 2018, Querétaro, Mexico

Patients with ALL constituted the largest group and were thus used for a sub‐analysis (n = 77). Cox regression analysis was used to compute crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) to identify predictors of OS and RFS in children with ALL.

Data management and statistical analyzes were carried out in SPSS v.24.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 presents basic characteristics of patients with cancer aged 0–17 years admitted to the hospital during the study period. Nearly 300 children were hospitalized since HITO started activities until February 2018. More number of boys were treated than girls (155 vs. 131). Children from all ages were hospitalized, but the majority were 1–4 years old (36.4%). TOCNS accounted for 45.1% of diagnoses, but ALL was the most frequent single diagnosis observed (28%). Death occurred in 22.4% of children, and relapse in 22.7% (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Basic characteristic of cancer patients aged 0–17 admitted to the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 2018, Querétaro, Mexico

| Variable | Category | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 155 | 54.2 |

| Female | 131 | 45.8 | |

| Age group (y) | <1 | 20 | 7.0 |

| 1–4 | 104 | 36.4 | |

| 5–9 | 68 | 23.8 | |

| 10–17 | 94 | 32.9 | |

| Tumor location | Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 80 | 28.0 |

| Tumors within the CNS a | 55 | 19.2 | |

| Tumors outside the CNS b | 129 | 45.1 | |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | 22 | 7.7 | |

| Relapse | Yes | 65 | 22.7 |

| No | 221 | 77.3 | |

| Current state | Death | 64 | 22.4 |

| Under treatment | 85 | 29.7 | |

| Current | 131 | 45.8 | |

| Palliative care, abandoned | 6 | 2.0 | |

| Total | 286 | 100.0 |

It includes astrocytic tumors, ependymal tumors, oligodendroglial tumors, embryonal tumors, tumors of sellar region, and germ cell tumors.

It includes retinoblastomas, Wilms tumors, neuroblastomas, osteosarcomas, Ewing's sarcomas, soft‐tissue sarcomas, rhabdomyosarcomas, germ‐cell tumors, hepatic tumors, and thyroid tumors.

OS at years 1 and 3 after admission by age group, sex, and cancer location are shown in Table 2. For all cancer groups, OS at 1 and 3 years was 83.9% and 72%, respectively; boys showed consistently higher OS than girls, and children aged 10–17 years tended to have the lowest OS compared with the other age groups. For ALL, overall OS was 89.7% and 87.2% at 1 and 3 years, respectively, with OS being slightly higher in boys, and among those aged 5–9 years. OS for TWCNS were lowest compared with the other cancer groups at years 1 and 3 with 71.4%, and 59.1%, respectively, with boys having a better survival than girls. The OS rates for TOCNS were 85.8% and 67.6% at years 1 and 3, respectively, with no clear differences by sex and age group (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Surviving patients at years 1 (n = 230) and 3 (n = 132) after admission in children aged 0–17 years at the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 2018 by cancer location, age group and sex, Querétaro, Mexico

| Survival (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | All ages | 0–4 years | 5–9 years | 10–17 years | |||||

| Year | Age group | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| All cancers | |||||||||

| Total | 83.9 | 72.0 | 83.1 | 82.4 | 89.9 | 70.3 | 79.5 | 61.4 | |

| Boys | 87.3 | 76.0 | 84.8 | 85.7 | 92.7 | 73.1 | 84.6 | 66.7 | |

| Girls | 79.8 | 66.7 | 81.1 | 78.3 | 85.7 | 63.6 | 74.4 | 56.5 | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |||||||||

| Total | 89.7 | 87.2 | 90.5 | 87.5 | 100 | 92.9 | 75.0 | 77.8 | |

| Boys | 97.3 | 91.3 | 100 | 87.5 | 100 | 90.9 | 90.0 | 100 | |

| Girls | 80.6 | 81.3 | 81.8 | 87.5 | 100 | 100 | 60.0 | 60.0 | |

| Tumors within the central nervous system | |||||||||

| Total | 71.4 | 59.1 | 58.8 | 75.0 | 77.8 | 50.0 | 78.6 | 50.0 | |

| Boys | 81.8 | 72.7 | 57.1 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 75.0 | 100 | 66.7 | |

| Girls | 63.0 | 45.5 | 60.0 | 75.0 | 70.0 | 25.0 | 57.1 | 33.3 | |

| Tumors outside the central nervous system | |||||||||

| Total | 85.8 | 67.6 | 88.9 | 81.5 | 87.5 | 60.0 | 81.8 | 58.6 | |

| Boys | 83.6 | 68.3 | 86.2 | 87.5 | 87.5 | 54.5 | 77.3 | 57.1 | |

| Girls | 89.1 | 66.7 | 93.8 | 72.7 | 87.5 | 75.0 | 86.4 | 60.0 | |

Table 3 shows RFS at years 1 and 3 after diagnosis by age group, sex, and cancer location. For all cancer groups, RFS at years 1 and 3 was 85.6% and 72.5%, respectively, with boys having slightly higher rates than girls, and children aged 5–9 years also showing slightly higher rates compared with the other age groups. For ALL, RFS was 95.5% and 89.7% at 1 and 3 years, respectively, with no clear trends by sex or age group. For TWCNS, RFS was 89.7% and 61.9% at years 1 and 3, respectively, with no clear trends by sex and age group. For TOCNS, RFS was 77.8% and 66.2%, at 1 and 3 years, respectively; boys tended to have higher rates than girls, but no trend was seen by age group (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Patients free of relapse at years 1 (n = 230) and 3 (n = 132) after admission in children aged 0–17 years at the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 2018 by cancer location, age group, and sex, Querétaro, Mexico

| Free of relapse (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | All ages | 0–4 years | 5–9 years | 10–17 years | |||||

| Year | Age group | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| All cancers | |||||||||

| Total | 85.6 | 72.5 | 84.3 | 72.5 | 89.9 | 75.7 | 83.2 | 69.8 | |

| Boys | 85.7 | 74.3 | 84.7 | 75.0 | 92.7 | 76.9 | 79.5 | 70.0 | |

| Girls | 85.4 | 70.2 | 83.8 | 69.6 | 85.7 | 72.7 | 87.0 | 69.6 | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | |||||||||

| Total | 95.5 | 89.7 | 100 | 81.3 | 100 | 100 | 84.4 | 88.9 | |

| Boys | 91.9 | 91.3 | 100 | 87.5 | 100 | 100 | 70.0 | 75.0 | |

| Girls | 100 | 87.5 | 100 | 75.0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| Tumors within the central nervous system | |||||||||

| Total | 89.7 | 61.9 | 94.1 | 62.5 | 83.3 | 62.5 | 92.9 | 60.0 | |

| Boys | 90.9 | 60.0 | 100 | 50.0 | 87.5 | 75.0 | 85.7 | 50.0 | |

| Girls | 88.9 | 63.6 | 90.0 | 75.0 | 80.0 | 50.0 | 100 | 66.7 | |

| Tumors outside the central nervous system | |||||||||

| Total | 77.8 | 66.2 | 73.2 | 70.4 | 83.3 | 60.0 | 79.5 | 65.5 | |

| Boys | 80.5 | 68.3 | 75.7 | 75.0 | 87.5 | 54.5 | 81.8 | 71.4 | |

| Girls | 73.9 | 63.3 | 68.8 | 63.6 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 77.3 | 60.0 | |

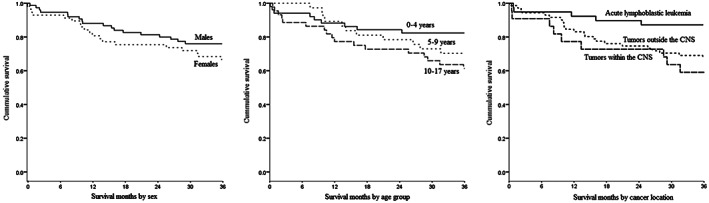

Figure 2 displays Kaplan–Meier curves for OS in months by sex, age group, and cancer location. Curves depict the higher survival seen in boys, and the lower survival among those ages 0–17 years at the time of admission. For cancer location, the ALL curve reflects the notably better survival compared with the other cancer groups (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan‐Meier plots for cancer survival in months for hospitalized patients aged 0–17 years who completed 3 years of follow‐up at the Telethon Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 201 by sex, age group and malignancy locations, Querétaro, Mexico (n = 132)

Table 4 presents OS and RFS for patients aged 0–17 years who fulfilled the HITO criteria at years 1 (n = 191) and 3 (n = 110) after admission. OS was higher in this subsample compared with the full sample for all cancer groups in both follow‐up years analyzed (e.g., year 1: 94.2% vs. 83.9%; year 3: 84.5% vs. 72%). Overall, ALL reached 93.8% and 91.9% survival, TWCNS 90.3% and 86.7%, and TOCNS 95.8% and 79.3% at years 1 and 3, respectively. Both 1‐ and 3‐year survival rates tended to decrease with age group. For FRS, overall rates were slightly higher for years 1 and 3 when using the HITO criteria than with the full sample (year 1: 87.9% vs. 85.9%; year 3: 76.4% vs. 72.5%). Children with ALL reached 95.3% and 89.2% free of relapse, TWCNS 87.1% and 60%, and TOCNS 83.1% and 72.4% at years 1 and 3, respectively. Neither OS nor RFS showed clear trends in rates by age group (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Surviving and free of relapse patients who fulfilled the HITO criteria a at years 1 (n = 191) and 3 (n = 110) at the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 2018 by cancer location and age group, Querétaro, Mexico

| Percentage | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | All ages | 0–4 years | 5–9 years | 10–17 years | |||||

| Year | Age group | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Survival | |||||||||

| All cancers | 94.2 | 84.5 | 95.8 | 91.3 | 94.8 | 81.3 | 91.8 | 78.1 | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 93.8 | 91.9 | 100 | 93.3 | 100 | 92.9 | 87.5 | 78.9 | |

| Tumors within the CNS | 90.3 | 86.7 | 90.9 | 100 | 81.8 | 66.7 | 100 | 100 | |

| Tumors outside the CNS | 95.8 | 79.3 | 95.2 | 88.0 | 95.0 | 75.0 | 97.0 | 71.4 | |

| Free of relapse | |||||||||

| All cancers | 87.9 | 76.4 | 84.7 | 71.7 | 93.1 | 84.4 | 86.8 | 75.0 | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 95.3 | 89.2 | 100 | 80.0 | 100 | 100 | 83.6 | 85.7 | |

| Tumors within the CNS | 87.1 | 60.0 | 90.9 | 50.0 | 81.8 | 66.7 | 88.9 | 66.7 | |

| Tumors outside the CNS | 83.1 | 72.4 | 76.0 | 72.0 | 90.0 | 75.0 | 87.9 | 71.4 | |

No prior treatment received, underwent surgery/chemotherapy when indicated, and initiated therapy at the hospital.

Crude and adjusted HRs with 95% CIs for surviving and free of relapse children with ALL aged 0–17 years who fulfilled the HITO criteria (n = 77) are shown in Table 5. Sex, age group, and risk category were not significant predictors in both crude and adjusted analyzes for either outcome. However, adjusted HR point estimates for survival were higher as the cancer risk category increased (high 3.34, very high 4.77), and among girls (1.96); similar patterns were also seen for relapse‐free HRs (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Crude and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) from Cox regression for relapse‐free and overall survival of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia aged 0–17 years (n = 77) who fulfilled the HITO criteria a at the Telethon Pediatric Oncology Hospital from December 2013 to February 2018, Querétaro, Mexico

| Model | Category | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted b | ||

| Overall survival | |||

| Risk category | Standard | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High | 5.87 (0.65–52.6) | 3.34 (0.24–44.7) | |

| Very high | 7.57 (0.84–67.8) | 4.77 (0.49–45.8) | |

| Sex | Male | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 1.90 (0.51–7.11) | 1.96 (0.50–7.66) | |

| Age group in years | 1–4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5–9 | 0.20 (0.02–1.81) | 0.31 (0.03–3.12) | |

| 10–17 | 1.49 (0.37–5.98) | 1.36 (0.20–9.17) | |

| Relapse‐free | |||

| Risk category | Standard | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High | 4.19 (0.84–20.7) | 2.84 (0.38–21.1) | |

| Very high | 4.68 (0.90–24.1) | 4.77 (0.85–26.6) | |

| Sex | Male | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Female | 0.97 (0.31–2.98) | 0.98 (0.31–3.06) | |

| Age group in years | 1–4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5–9 | 0.79 (0.19–3.18) | 1.19 (0.26–5.38) | |

| 10–17 | 1.99 (0.53–7.49) | 1.93 (0.28–13.0) | |

No prior treatment, underwent surgery/chemotherapy when indicated, and initiated therapy at the hospital.

The models were adjusted for all the variables included in the table.

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed at determining OS and RFS rates for patients admitted at HITO between 2013 and 2018. OS was used as an indicator of the overall care provided, and RFS as a measure of success of the initial treatment.

Of all malignancies studied, 28% corresponded to ALL, 19.2% to TWCNS, and 45.1% to TOCNS. These proportions are similar to the reported in the international literature. 32

From all hematological malignancies admitted at HITO during the study period (n = 116), 80 were ALL and 36 were non‐ALL (Hodgkin lymphoma 12, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma 11, acute myeloid leukemia 10, and chronic myeloid leukemia 3). From the leukemias, the proportion of ALL was 86%, very similar to the 85.1% reported in a study with children aged <15 years diagnosed in public hospitals of Mexico City during 2006–2007. 33 OS and RFS for all hemathological malignancies was 88.5% and 82.9% at year 3, respectively. When excluding patients not enrolled in the HITO model, the sample for each non‐ALL malignancy was further reduced. Therefore, we decided to present ALL as a single group to establish comparisons with other populations, as this is the most frequent pediatric cancer.

We pooled together TOCNS due to sample size constraints, and because this is the official categorization of the “Seguro Popular,” 34 the governmental institution that shares with HITO the financial costs of the care provided to 64.5% of the patients admitted.

OS of HITO children treated between December 2013 and February 2018 with ALL was higher compared with that of other cancers, as previously reported. 35 , 36 The 50%–65% 5‐year OS for ALL reported in Mexico among children aged 0–17 years 37 contrasts with the notably higher 91.9% observed under the HITO model at 3‐years of follow‐up. This survival can also be compared with a study from the University Hospital of Monterrey (northern Mexico) where 5‐year survival of patients aged ≤16 years treated with BFM‐inspired protocols during the 2004–2015 period for ALL ranged 55.5%–67.1%. 38 In another study with an average follow‐up of 3.9 years, children aged <16 years treated between 2006 and 2010 at the National Medical Center of the Mexican Institute of Social Security for ALL using a DFCI protocol showed a survival of 63.9%. 39 HITO's survival is comparable to that reported by the COG Report that contains data ranging from 1982 to 2002. 40 In fact, the OS for pediatric patients at HITO for standard risk ALL matched the benchmark estimates achieved in high‐income settings. 41

HITO patients also showed lower ALL relapse rates compared with other Mexican studies published earlier. 37 , 39 , 42 This is likely due to the better quality of care and to the higher adherence to HIC's advanced standards of care.

Early diagnosis and treatment of ALL relate to better OS and RFS. 43 However, patients aged <1 year and > 10 years tend to have less favorable outcomes. 44 , 45 During the 3‐year follow‐up period, children aged 0–4 years relapsed notably less than older children, a finding consistent with recent studies that report better survival outcomes in those with no early relapse, 46 and among younger children. 47

On the other hand, some differentials by sex with regards to ALL survival and relapse were observed, as it has been reported by other authors. 48 , 49 In this study, sex differences were relatively small not reaching statistical significance in log‐rank tests (e.g., 3‐year OS for all cancers in those aged 0–17 years: boys 76% vs. girls 66.7%; p > 0.05); differences seemed to relate to the small sample, especially when stratifying data. Also, crude (HR 1.90; 95% CI 0.51–7.11) and adjusted (1.96; 0.50–7.66) estimates for sex were not significant in regression analyzes. From the cultural perspective, we have no data suggesting a possible parental bias whereby caretakers might give more value and care to boys. Financially, this can be ruled out, as the full treatment given, including the parents' support in the adjacent facilities devised for that purpose, were completely free of charge.

We tried to identify predictors of survival and relapse in patients with ALL using Cox regression. Risk category is a well‐established predictor of survival with higher HR in the high‐risk and very high‐risk categories compared with the standard‐risk category. 27 , 50 Also, adolescents have shown higher HR compared with younger children. 48 However, neither sex, age group, nor risk category were statistically associated in adjusted analyzes. Possible reasons for failing to replicate these findings include the small sample size that led to low precision, and the incomplete adjustment of confounders including tumor subtype and staging, and the initial response to therapy that could have biased the estimates.

Based on the HITO model, 1‐year relapse rate was 4.7%, 12.9%, and 16.9% for ALL, TWCNS, and TOCNS, respectively. All patients who relapsed after the first year were given a second‐line treatment with the intention to cure. 51 , 52 , 53 Comparing these results with international studies could not be done, as we followed the Mexican official classification, and combined various diagnoses due to sample size constraints.

We decided to conduct a specific analysis with patients who fulfilled the HITO criteria. This was done to better assess the therapeutic performance of the HITO model. After exclusion, OS tended to increase, as one would have expected (e.g., all cancers, all ages, 3‐year OS: non‐HITO 72% vs. HITO 84.5%; ALL, all ages, 3‐year OS: non‐HITO 87.2% vs. HITO 91.9%). This finding points to the value of using an integrated and comprehensive care model. 54 , 55 The HITO model uses a family‐centered strategy that prevents treatment abandonment and promotes comprehensive health care; it is supported in five pillars: (1) diagnostic certainty to give the best treatment for each patient, (2) advanced evidence‐based medicine for a successful therapy, (3) human development at Casa Teletón to encourage personal growth through educational and occupational activities that promote treatment adherence, (4) improved quality of life for patients/caretakers to advance their physical, emotional, and spiritual well‐being aimed at avoiding treatment abandonment through services such as psychooncology, thanatology, recreational activities, schooling program, palliative care, and pain management, and (5) prevention and management of complications to avoid deaths using an infection control program, and the 24/7 functioning of the ICU and blood bank to treat and mitigate side effects and complications.

Compared with the full analyzes, the sub‐analysis showed higher OS, especially for TWCNS. This indicates that excluded patients had a considerably poorer prognosis due to an advanced cancer stage without proper diagnosis/treatment, and/or because therapy used initially was not followed. These were patients that did not accept the standardized oncologic therapy (i.e., did not consent chemotherapy and/or surgery), had been previously treated elsewhere, or died before an accurate histopathological diagnosis was established. Regardless of whether patients followed the HITO model or not, all children received the best available treatment at the time of initial assessment according to the consensus of the specialists' working group.

While treatment duration for most conditions diagnosed at HITO is at least 1 year, 1‐year survival was included because mortality due to chemotherapy complications within the first months of treatment in LMIC can reach 23% compared with 3% in HIC. Mortality has been associated with inadequate nutrition and poor hospital accessibility. After initial treatment, children from low‐income settings are sent to their homes located far away, and with poor access to hospital facilities. These hospitals are often deprived of means to handle severe complications caused by the toxicity of the intense induction chemotherapy. 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 Actually, in a Mexican study of children with ALL treated using a DFCI protocol, 7% died during induction; deaths were associated with delays in hospital care, poor general conditions, tumor charge, malnutrition, infection, and treatment toxicity. 41 Moreover, a recent study from a major pediatric hospital in Mexico revealed the importance of improving the safety and quality of care of children with ALL; it was estimated that the incidence of adverse events (51.8/1000 patient‐days) linked to morbidity and mortality during the induction phase that can be prevented and mitigated was 10.5% and 53.6%, respectively. 60

Early relapse has also been used to predict survival. 46 , 51 , 52 , 53 While no such correlation was observed for ALL using 18‐month relapse in this study, a moderate correlation was seen between 12‐month relapse and survival for TOCNS (r = 0.44) and TWCNS (r = 0.43).

Results from HSCT patients were not presented, as these patients belonged to two different groups: those who were initially treated using the HITO model and then transplanted, and those transferred from another institution just for the transplant. Patients from the latter group, who represented more than half of all HSCT, had incomplete data regarding the previous treatment received. Therefore, the scant number of HSCT HITO patients with complete data precluded meaningful estimates. All trasplants were allogeneic of related donors (46%), autologous (27%), and haploidentical (27%). Initial diagnoses included mostly ALL in second remission (n = 9), high risk neuroblastoma (n = 5), and chronic myelogenous leukemia (n = 3). The100‐day post‐transplant survival was 100%, and post‐transplant relapse was 27% during the study period.

The major strength of HITO relates to the standard set in Mexico, in terms of OS and RFS, by a specialized hospital exclusively focusing on pediatric oncology care using a comprehensive and integrated therapeutic model. This hospital is part of a nonprofit foundation that provides nondiscriminatory pediatric oncology care to children from all socioeconomic strata from any Mexican state, but mostly to the poor. Actually, 98% of patients treated at HITO are not affiliated to any public or private health institution. Another strength relates to the 2% treatment abandonment. This very low rate is explained by three main factors: to Casa Teletón that provides comprehensive assistance to children/caretakers during critical stages of treatment, to the fact that all care provided is completely free of charge, and to the work conducted by social workers that provide financial assistance to patients and caretakers to attend scheduled visits in the case of economic hardships.

Finally, some limitations ought to be mentioned: (1) the sample size for individual cancers other than ALL were too small, especially for TWCNS, to produce stable survival estimates; the 19 patients excluded initially due to incomplete or inaccurate data were the result of missing data, typing mistakes, and incoherent information, and are therefore unlikely to have biased the results observed, (2) the grouping of cancers within and outside the CNS precluded direct comparisons with other studies that do not use such categorization; it was used, as it is the official classification of the Mexican Secretariat of Health, 61 (3) the inability to compute 5‐year survival estimates, as only a small number of patients had completed such follow‐up when permission was granted to retrieve the data for analyzes, (4) the incomplete number of variables required to run a more thorough adjusted analysis for ALL, and (5) the limited representativeness of the sample, which makes it difficult to generalize the findings to public hospitals with limited resources, and to private settings not specialized in pediatric oncology care.

In spite of increasing funding to treat pediatric cancer in Mexico, survival has not increased as expected. 62 Poor survival in LMIC is often related to delayed, erroneous, or deficient diagnosis, lack of specialized facilities and services, treatment abandonment, lack of adequate medications, treatment toxicity, excess relapse, malnutrition, and high prevalence of comorbidities. 63 While HITO has been able to provide advanced treatment and supportive care throughout the illness process, unfortunately many pediatric oncologic units in Mexico lack of adequate infrastructure, services, and trained staff to offer adequate care that can lead to the highest survival possible. Therefore, it is crucial that governmental and private health institutions, along with philanthropic organizations, collaborate together from the early identification of children with cancer to all subsequent therapeutic and rehabilitation stages.

We believe that the findings presented here highlight the value of implementing a successful therapeutic model in a country with relatively limited resources such as Mexico that could be of use in similar settings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Joel Monárrez‐Espino: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (supporting); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (lead); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); validation (equal); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (lead). Lourdes Romero‐Rodríguez: Conceptualization (supporting); data curation (lead); formal analysis (supporting); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); validation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Gabriela Escamilla‐Asiain: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); project administration (lead); supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Andrea Ellis‐Irigoyen: Data curation (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); validation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). María del Pilar Cubría‐Juárez: Data curation (supporting); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); validation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Douglas Sematimba: Data curation (supporting); methodology (supporting); validation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Carlos Rodríguez‐Galindo: Data curation (supporting); methodology (supporting); validation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Lourdes Vega‐Vega: Conceptualization (equal); investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting).

ETHIC STATEMENT

The following sentences were added: All procedures preformed were in accordance with national and international ethical standards.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S1 Summary of the treatment protocols used by type of pediatric malignancy at HITO, Querétaro, Mexico

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge datamanager Jessica Rincón Rivera for integrating and maintaining the hospital database.

Monárrez‐Espino J, Romero‐Rodriguez L, Escamilla‐Asiain G, et al. Survival estimates of childhood malignancies treated at the Mexican telethon pediatric oncology hospital. Cancer Reports. 2023;6(2):e1702. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1702

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Farmer P, Frenk J, Knaul FM, et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1186‐1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gupta S, Rivera‐Luna R, Ribeiro RC, Howard SC. Pediatric oncology as the next global child health priority: the need for national childhood cancer strategies in low‐ and middle‐income countries. PLoS Med. 2014;11(6):e1001656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodriguez‐Galindo C, Friedrich P, Morrissey L, Frazier L. Global challenges in pediatric oncology. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2013;25(1):3‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perez‐Cuevas R, Doubova SV, Zapata‐Tarres M, Flores‐Hernandez S, Frazier L, et al. Scaling up cancer care for children without medical insurance in developing countries: the case of Mexico. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):196‐203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ribeiro RC. Impact of the Mexican government's system of social protection for health, or Seguro popular, on pediatric oncology outcomes. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(2):171‐172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rivera‐Luna R, Shalkow‐Klincovstein J, Velasco‐Hidalgo L, Cardenas‐Cardos R, Zapata‐Tarres M, et al. Descriptive epidemiology in Mexican children with cancer under an open national public health insurance program. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rivera‐Luna R, Velasco‐Hidalgo L, Zapata‐Tarres M, Cardenas‐Cardos R, Aguilar‐Ortiz MR. Current outlook of childhood cancer epidemiology in a middle‐income country under a public health insurance program. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;34(1):43‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rivera‐Luna R, Zapata‐Tarres M, Shalkow‐Klincovstein J, et al. The burden of childhood cancer in Mexico: implications for low‐ and middle‐income countries. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(6):e26366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kaatsch P. Epidemiology of childhood cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2010;36(4):277‐285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aristizabal P, Fuller S, Rivera‐Gomez R, et al. Addressing regional disparities in pediatric oncology: results of a collaborative initiative across the Mexican‐north American border. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64(6):e26387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nakata K, Ito Y, Magadi W, et al. Childhood cancer incidence and survival in Japan and England: a population‐based study (1993‐2010). Cancer Sci. 2018;109(2):422‐434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martin‐Trejo JA, Nunez‐Enriquez JC, Fajardo‐Gutierrez A, Medina‐Sanson A, Flores‐Lujano J, et al. Early mortality in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a developing country: the role of malnutrition at diagnosis. A multicenter cohort MIGICCL study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(4):898‐908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chatenoud L, Bertuccio P, Bosetti C, Levi F, Negri E, la Vecchia C. Childhood cancer mortality in America, Asia, and Oceania, 1970 through 2007. Cancer. 2010;116(21):5063‐5074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rodriguez‐Romo L, Olaya‐Vargas A, Gupta S, Shalkow‐Klincovstein J, Vega‐Vega L, et al. Delivery of pediatric cancer Care in Mexico: a National Survey. J Global Oncol. 2018;4:1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Green DM. The treatment of stages I‐IV favorable histology Wilms' tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1366‐1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kalapurakal JA, Dome JS, Perlman EJ, et al. Management of Wilms' tumour: current practice and future goals. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(1):37‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meyers PA, Schwartz CL, Kralio MD, Healey JH, Bernstein ML, et al. Osteosarcoma: the addition of muramyl tripeptide to chemotherapy improves overall survival‐ a report from the Children's oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):633‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Matthay KK, Reynolds CP, Seeger RC, et al. Long‐term results for children with high‐risk neuroblastoma treated on a randomized trial of myeloablative therapy followed by 13‐cis‐retinoic acid: a children's oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1007‐1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baker DL, Schmidt ML, Cohn SL, et al. Outcome after reduced chemotherapy for intermediate‐risk neuroblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1313‐1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pollack IF. Multidisciplinary management of childhood brain tumors: a review of outcomes, recent advances, and challenges. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2011;8(2):135‐148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Strother DR, London WB, Schmidt ML, et al. Outcome after surgery alone or with restricted use of chemotherapy for patients with low‐risk neuroblastoma: results of Children's oncology group study P9641. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1842‐1848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abramson DH, Shields CL, Munier FL, Chantada GL. Treatment of retinoblastoma in 2015: agreement and disagreement. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(11):1341‐1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meyers PA. Systemic therapy for osteosarcoma and Ewing sarcoma. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2015;35:e644‐e647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marina NM, Smeland S, Bielack SS, et al. Comparison of MAPIE versus MAP in patients with a poor response to preoperative chemotherapy for newly diagnosed high‐grade osteosarcoma (EURAMOS‐1): an open‐label, international, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):1396‐1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skapek SX, Ferrari A, Gupta AA, et al. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vrooman LM, Silverman LB. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: update on prognostic factors. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(1):1‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silverman LB, Stevenson KE, O'Briend JE, Asselin BL, Barr RD, et al. Long‐ term results of Dana Farber cancer institute ALL Consorcium protocols for children with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia (1985–2000). Leukemia. 2010;24(2):320‐334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silverman LB, Supko JG, Stevenson KE, et al. Intravenous PEG‐asparaginase during remission induction in children and adolescents with newly diagnosed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(7):1351‐1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Place AE, Stevenson KE, Vrooman LM, et al. Intravenous pegylated asparaginase versus intramuscular native Escherichia colil‐asparaginase in newly diagnosed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (DFCI 05‐001): a randomised, open‐label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(16):16‐1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457‐481. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steliarova‐Foucher E, Colombet M, Ries LAG, et al. International incidence of childhood cancer, 2001‐10: a population‐based registry study. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(6):719‐731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pérez‐Saldivar ML, Fajardo‐Gutiérrez A, Bernáldez‐Ríos R, et al. Childhood acute leukemias are frequent in Mexico City: descriptive epidemiology. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud . Seguro Popular: Fondo de Protección contra Gastos Catastróficos. Gobierno de México, 2019. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/salud%7Cseguropopular/articulos/que-es-el-fondo-de-proteccion-contra-gastos-catastroficos

- 35. Kersey JH. Fifty years of studies of the biology and therapy of childhood leukemia. Blood. 1997;90(11):4243‐4251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Terwilliger T, Abdul‐Hay M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017;7(6):e577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Verduzco‐Rodriguez L, Verduzco‐Aguirre HC. Prevalence of high risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) in Mexico, a possible explanation for outcome disparities. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15):e22501. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jaime‐Pérez JC, López‐Razo ON, García‐Arellano G, et al. Results of treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a low‐middle income country: 10 year experience in Northeast Mexico. Arch Med Res. 2016;47(8):668‐676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jiménez‐Hernández E, Jaimes‐Reyes EZ, Arellano‐Galindo J, et al. Survival of Mexican children with acute lymphoblastic Leukaemia under treatment with the protocol from the Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute 00‐01. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:576950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gaynon PS, Angiolillo AL, Carroll WL, et al. Long‐term results of the children's cancer group studies for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia 1983–2002: a Children's oncology group report. Leukemia. 2010;24(2):285‐297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975‐2013. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 2015. Accessed April 30, 2020.

- 42. Ibagy A, Silva DB, Seiben J, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in infants: 20 years of experience. J Pediat‐Brazil. 2013;89(1):64‐69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen J, Mullen CA. Patterns of diagnosis and misdiagnosis in pediatric cancer and relationship to survival. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39(3):e110‐e115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Möricke A, Zimmermann M, Reiter A, Gadner H, Odenwal E, et al. Prognostic impact of age in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: data from the trials ALL‐BFM 86, 90, and 95. Klin Padiatr. 2005;217(6):310‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pieters R, Schrappe M, De Lorenzo P, Hann I, De Rossi G, et al. A treatment protocol for infants younger than 1 year with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Interfant‐99): an observational study and a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):240‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nguyen K, Devidas M, Cheng SC, La M, Raetz EA, et al. Factors influencing survival after relapse from acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a children's oncology group study. Leukemia. 2008;22(12):2142‐2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Oskarsson T, Soderhall S, Arvidson J, et al. Relapsed childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the Nordic countries: prognostic factors, treatment and outcome. Haematologica. 2016;101(1):68‐76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pui CH, Pei D, Campana D, et al. Improved prognosis for older adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(4):386‐391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hann I, Vora A, Harrison G, et al. Determinants of outcome after intensified therapy of childhood lymphoblastic leukaemia: results from Medical Research Council United Kingdom acute lymphoblastic leukaemia XI protocol. Br J Haematol. 2001;113(1):103‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cooper SL, Brown PA. Treatment of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2015;62(1):61‐73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Stahl M, Ranft A, Paulussen M, et al. Risk of recurrence and survival after relapse in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(4):549‐553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leary SE, Wozniak AW, Billups CA, Wu J, PcPherson V, et al. Survival of pediatric patients after relapsed osteosarcoma: the St Jude Children's Research Hospital Experience. Cancer. 2013;119(14):2645‐2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cho HW, Lee JW, Ma Y, Yoo KH, Sung KW, Koo HH. Treatment outcomes in children and adolescents with relapsed or progressed solid tumors: a 20‐year, single‐center study. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33(41):e260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fennell ML, Das IP, Clauser S, Petrelli N, Salner A. The organization of multidisciplinary care teams: modeling internal and external influences on cancer care quality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010(40):72‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Hord J, Feig S, Crouch G, et al. Standards for pediatric cancer centers. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):410‐414. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lepe‐Zuniga JL, Ramirez‐Nova V. Elements associated with early mortality in children with B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Chiapas, Mexico: a case‐control study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;41(1):1‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Abdelmabood S, Fouda AE, Boujettif F, Mansour A. Treatment outcomes of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a middle‐income developing country: high mortalities, early relapses, and poor survival. J Pediatr. 2020;96(1):108‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Schraw JM, Peckham‐Gregory EC, Rabin KR, Scheurer ME, Lupo PJ, Oluyomi A. Area deprivation is associated with poorer overall survival in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(9):e28525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Rahat‐Ul‐Ain FM, Shamim W. Treatment‐related mortality in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in a low‐middle income country. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(10):2373‐2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vázquez‐Cornejo E, Morales‐Ríos O, Hernández‐Pliego G, Cicero‐Oneto C, Garduño‐Espinosa J. Incidence, severity, and preventability of adverse events during the induction of patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a tertiary care pediatric hospital in Mexico. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0265450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Secretaría de Salud. Epidemiología del cáncer en menores de 18 años. México 2015. Boletín 151217. Centro Nacional para la Salud de la Infancia y Adolescencia: Ciudad de México, 2015. www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/281302/Boletin_CIA_2016_151217.pdf

- 62. Muñoz‐Aguirre P, Huerta‐Gutierrez R, Zamora S, et al. Acute lymphoblastic Leukaemia survival in children covered by Seguro popular in Mexico: a National Comprehensive Analysis 2005‐2017. Health Syst Reform. 2021;7(1):e1914897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Doubova SV, Knaul FM, Borja‐Aburto VH, et al. Access to paediatric cancer care treatment in Mexico: responding to health system challenges and opportunities. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35(3):291‐301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

SUPPLEMENTARY TABLE S1 Summary of the treatment protocols used by type of pediatric malignancy at HITO, Querétaro, Mexico

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.