Abstract

Gas-phase and aqueous oxidations of formic and oxalic acids with ozone and OH radicals have been thoroughly examined by DFT methods. Such acids are not only important feedstocks for the iterative construction of other organic compounds but also final products generated by mineralization and advanced oxidation of higher organics. Our computational simulation unravels both common and distinctive reaction channels, albeit consistent with known H atom abstraction pathways and formation of hydropolyoxide derivatives. Notably, reactions with neutral ozone and OH radical proceed through low-energy concerted mechanisms involving asynchronous transition structures. For formic acid, carbonylic H-abstraction appears to be more favorable than the dissociative abstraction of the acid proton. Formation of long oxygen chains does not cause a significant energy penalty and highly oxygenated products are stable enough, even if subsequent decomposition releases environmentally benign side substances like O2 and H2O.

Introduction

Ozonation has become a valuable and efficient tool in disinfection treatments of drinking water and wastewater, resulting from the rapid degradation of numerous organic pollutants1,2 and inactivation of pathogenic microorganisms3,4 present in aqueous environments. Like other advanced oxidation processes (AOPs), ozone-based protocols can be conducted alone and in combination with a broad range of activation methods, ranging from photoirradiation and the use of both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts.5−10 In general, ozone is more efficient than molecular oxygen in the catalytic oxidation of volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and higher conversions can be achieved at lower temperatures and mild conditions.5

The aqueous chemistry of ozone-mediated reactions may involve intermediates and radical species observed in gas-phase reactions, widely studied in the context of ozone depletion or atmospheric aerosol formation.11−14 However, additional and distinctive reaction channels arise from phenomena such as solvation, ionization, and intermolecular associations, which complicate the search of satisfactory interpretations. Thus, although ozonation is extremely useful from a practical viewpoint, there is still a lack of mechanistic understanding at the molecular level, and the putative pathways, especially with complex organics, remain speculative. In recent years, application to AOPs of first-principle calculations, often aided by density functional theory (DFT) simulations, sheds light upon reaction pathways and intermediates, which have eventually been identified by experiments. Among them, Criegee intermediates (carbonyl oxides), produced by the ozonolysis of unsaturated hydrocarbons in the atmosphere, can also trigger subsequent reactions with both inorganics and organics and leading to aerosol formation.15−18

Herein, we provide an in-depth computational study on the interaction of ozone with formic and oxalic acids, which are archetypal ozonation reactions assessed by numerous experimental analyses, and serving as reactivity models of ozone toward organic acids. Moreover, such low-mass C1 and C2 carboxylic acids are often end-products detected during AOPs of other higher organic pollutants.

The reaction of ozone with formic acid in aqueous solution should be fairly credited to Nobelist Henry Taube, who in the early 1940s showed the existence of a chain reaction involving the formation of HO–HO2 species accounting for the decomposition of ozone and correlating well with results obtained in the ozone–peroxide reactions.19 As mentioned, formic acid is a common product found in the ozonolysis of aliphatic and substituted aromatic organics, often enhancing the oxidation when used as solvent. Combination of ozone–formic acid and H2O2–formic acid have long been used as oxidative degradation methods, and the intermediacy of performic acid was invoked more than 60 years ago.20 To a minor extent, oxalic acid is also present as a decomposition product.21 On the other hand, there has been a plethora of kinetic data on the OH-induced decomposition of organic acids, although rates reported should be interpreted with caution because experimental conditions vary from paper to paper.22 For ionizing compounds, the second-order rate constants increase with pH as does deprotonation of the dissolved acid.23 This also reflects the conversion of ozone into OH radicals by reaction with hydroxyl anions.24 However, the dependence of rate constants on pH lacks a clear-cut relationship when OH radicals are directly evaluated instead of ozone.22 In general, when the oxidation of organic compounds affords oxalic or acetic acid, further mineralization to CO2 is slower than oxidations leading to formic acid or formate.23,25 Remarkably, the presence of formate ions causes significant acceleration of oxidation, presumably due to formation of carbonate radical anion (CO3•–) as evidenced by the use of radical probes.26 Such an intermediate appears to occur in the gas-phase oxidation of formic acid with ozone, though mediated by tropospheric electrons.27 Despite variations, rate constants obtained by radiolytic28 and photochemical methods exhibit good agreement21,29 and are substantially enhanced when catalysts are present, thereby showing the synergetic effect owing to production of OH radicals.30−32

Although structural information cannot be inferred from kinetic data, it is evident the distinctive behavior of the actual oxidative agents, which depend in turn on the initial conditions. With these premises and in line with the scope of this theoretical study, reactions of formic and oxalic acids with either ozone or hydroxyl radicals have been computed leading to saddle points and products, whose structure, energy barriers, and stability are also consistent with the apparent rapidity observed by experimental methods.

Computational Methods

All calculations were carried out using the Gaussian16 package.33 Geometries and energies were optimized using the spin-unrestricted hybrid functional MN12-SX,34 which is a range-separated-hybrid meta-NGA (nonseparable gradient approximation),35 in combination with the Pople 6-311++G(2d,p) basis set.36 Geometries were optimized with inclusion of solvation effects in water using the SMD method.37,38 All saddle points linking specific reactant and products through the reaction path were verified using intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) analysis. Frequency calculations were carried out at 298.15 K at the above-mentioned level of theory. Saddle points and energy minima were characterized by one or none imaginary frequencies, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Reaction of Formic Acid and Ozone

Formic acid exemplifies well the case of double-H atom abstraction (or transfer) reactions, which are of paramount importance in atmospheric and aquatic chemistry. While numerous organic compounds are sensitive to single hydrogen transfer upon reaction with the OH radical, carboxylic acids are also prone to undergo both hydration and dehydration reactions.39 Organic acids containing α-hydrogens are susceptible to hydrogen transfer at the acidic carboxyl moiety and at alkyl carbons. In formic acid, the latter occurs at a less hindered sp2-hybridized carbon. This process is feasible enough with neutral O3 and our theoretical simulation is displayed in Scheme 1 (for the sake of clarity, atom numbering is shown along the different structures). Frontal attack of one terminal oxygen of ozone (O6 in Scheme 1) to aldehydic H atom of formic acid (H1) leads to the saddle point TS(1)+(2)→(3), which features similar geometric characteristics in both the gas phase and water, namely, the bond lengths H1–O6 (1.17 Å in the gas phase and 1.20 Å in water) and H1–C2 (1.36 Å in the gas phase and 1.34 Å in water), together with the angle C2–H1–O6 (168° in the gas phase and 174° in water) and dihedral angle H1–O6-O7–O8 (−60° in the gas phase and −72° in water). As expected, the saddle points were unambiguously characterized by their imaginary frequencies, at 1837i cm–1 (gas phase) and 1873i cm–1 (water).

Scheme 1. Abstraction of the Carbonylic H-Atom of Formic Acid by Ozone.

As usual, IRC (intrinsic reaction coordinate) analysis is customary to trace the path from the TS to the products and reactants. However, the curvature and length of the path also provides some insights into the reaction itself. Here, the IRC of TS(1)+(2)→(3) (Figure S1) evidence that the H1–C2 bond breaking is accompanied by a progressive shortening between the O8 and C2 atoms, thereby affording in concerted fashion the trioxidane derivative, 3, which may be regarded as the insertion product of ozone into the C–H bond of formic acid.

Formation of the highly oxygenated product 3 is consistent with previous literature reporting the chemistry of hydrogen trioxide, HOOOH, called trioxidane according to IUPAC nomenclature, which is the simplest polyoxide of formula ROnR (n ≥ 3) with R standing for hydrogen as well as alkyl, acyl, or other atoms.40,41 These elusive species are generated by ozonation of carbon–hydrogen bonds, i.e., from a formal viewpoint by the reduction of ozone by activated C–H bonds. Surprisingly, organic hydrotrioxides (ROOOH), which are indeed strong oxidants, have long been omitted in atmospheric chemistry, whereas a recent study evidences their formation by combination of peroxy radicals (RO2) and hydroxyl radicals (OH) (vide infra). In fact, this appears to be a dominant pathway in the atmosphere starting from volatile terpenes and hydrocarbons, from which peroxy species can easily be generated.42 Other mechanistic surrogates have been proposed in the last four decades, ranging from a 1,3-dipolar insertion of ozone to radical pairs and hydride ion abstraction.41 A better picture suggests that H atom abstraction and hydride abstraction would actually be extreme situations between a reaction complex with bifurcations depending on the experimental conditions.43

Trioxide 3 evolves through the shortening and subsequent transfer of H5 to O6 followed by C2–O8 bond breaking, which leads to the saddle point TS(3)→(4)+(5)+(6) [C2–O8 1.68 Å, O6–O7 1.68 Å, H5–O6 1.08 Å, H5–O4 1.36 Å in the gas phase and C2–O8 1.63 Å, O6–O7 1.69 Å, H5–O6 0.98 Å, H5–O4 2.19 Å in water] that directly drives to naturally occurring end products, namely CO2 (4), H2O (5), and O2 (6) (Scheme 2). IRC of the saddle point TS(3)→(4)+(5)+(6) (Figure S2) proves the aforementioned reaction path, and as expected, such a transition structure exhibited only one imaginary frequency (741i cm–1 in the gas phase and 382i cm–1 in water).

Scheme 2. Evolution of Trioxide 3 to Compounds 4–6.

The reactions of unsaturated oxygen-containing compounds of atmospheric relevance have been evaluated by theoretical methods,44 although the role of trioxides is scarcely addressed. The putative intermediates (either acyclic or cyclic in particular) have also been the subject of controversy, albeit results with carbonyls are illuminating in context. Thus, benzaldehyde undergoes ozone insertion into the aldehydic C–H bond. DFT calculations, at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level, evidence the highly exothermic formation of benzoyl hydrotrioxide, i.e., C6H5C(O)OOOH, which is conformationally unstable ending up with the elimination of benzoic acid and singlet oxygen.45 The stability of long oxygen chains, higher than H2O2, has been rationalized in terms of bond dissociation energies, and rapid decomposition is expected on moving from H2O3 (hydrogen trioxide) to the most reactive H2O4 and H2O6.46 Ozonation reactions with saturated oxygenates are less known, but they would similarly proceed through H-atom abstraction leading to formation of hydrotrioxides, which then evolve to R–OH and O2, according to a recent computational study performed on acyclic and cyclic oxolanes, alkyl hydroperoxides, and ethers.47

On the other hand, ozone can also react with formic acid by abstracting the acidic (carboxylic) proton (H5). Computation unravels a frontal attack as well, as shown in Scheme 3, giving rise to tetraoxidane 7.

Scheme 3. Formation of Tetraoxidane 7 by Reaction of Formic Acid and Ozone Involving Abstraction of the Acidic Proton H5.

The approach of the O6 atom to H5 proceeds in a concerted way affording the saddle point TS(1)+(2)→(7), characterized by the bond distances O4–H5 (1.23 Å in both media) and H5–O6 (1.17 Å in both media too), the angle O4–H5–O6 (172° in the gas phase and 173° in water), and the dihedral angle H5–O6–O7–O8 (−39° in the gas phase and −42° in water), with imaginary frequencies of 1179i cm–1 (gas phase) and 1232i cm–1 (water).

In a similar way to the preceding C–H cleavage, the IRC analysis of TS(1)+(2)→(7) (Figure S3) shows that O4–H5 bond breaking occurs with the concomitant shortening of the O8–O3 distance, leading to compound 7 in a concerted manner. These results indicate that abstraction of the carbonylic (aldehydic) hydrogen by ozone is more favorable in aqueous solution than the alternative and chemoselective abstraction at the acidic moiety (ΔΔG‡ = 2.07 kcal mol–1), while the gas-phase reaction follows the opposite trend, by favoring the abstraction of the carboxylic proton (ΔΔG‡ = 1.63 kcal mol–1).

The evolution of tetraoxidane 7 is initiated by the attack of a new molecule of ozone (2) to H1 of 7, which takes place through the saddle point TS(7)+(2)→(4)+2(6)+2(8) [bond length H1–C2 (1.31 Å in the gas phase and 1.33 Å in water); bond length H1–O9 (1.24 Å in the gas phase and 1.21 Å in water); angle C2–H1–O9 (160° in the gas phase and 178° in water); imaginary frequency (1736i cm–1 in the gas phase and 2015i cm–1 in water)] in which the abstraction of H1 by O9 is accompanied by O3–O8, O6–O7, and O9–O10 bond breaking, giving rise to CO2 (4), two molecules of O2 (6), and two hydroxyl radicals (8) (Scheme 4). Again, IRC analysis of TS(7)+(2)→(4)+2(6)+2(8) agrees with the reaction path depicted above (Figure S4).

Scheme 4. Evolution of Tetraoxidane 7 to End Species 4, 5, and 8.

Figure 1 and Figure S15 collect thermochemical data for the reaction of formic acid with ozone. This indicates that carbonylic H-abstraction is a little bit more favorable than the abstraction of the acid proton in water, but it is much less favorable than the abstraction of the acid proton in the gas phase.

Figure 1.

Relative free energies (ΔG, kcal mol–1) of all stationary points involved in the reaction of formic acid with ozone, at the UMN12SX/6-311++G(2d,p) level of theory with bulk solvation in water (SMD method).

Reaction of Oxalic Acid and Ozone

Unlike formic acid, oxalic acid (9) can only undergo H atom abstraction at the carboxylic fragment. The direct reaction with ozone is shown in Scheme 5.

Scheme 5. Reaction of Oxalic Acid with Ozone Forming Tetraoxidane 10.

The approach of one terminal oxygen (O6) to the H5 atom of 9 evolves with the formation of TS(9)+(2)→(10) (ΔG‡ = 21.77 kcal mol–1 in the gas phase and 28.16 kcal mol–1 in water; imaginary frequencies 1039i cm–1 and 722i cm–1, respectively) leading to the neutral trioxidane derivative 10. The key structural parameters are seldom distorted by solvation as reflected by bond distances O4–H5 (1.26 and 1.31 Å) and H5–O6 (1.15 and 1.12 Å, respectively), with angles O4–H5–O6 (172° in both media) and H5–O6–O7–O8 (−38° and −34°, respectively). In agreement with previous IRC analyses, this attack exhibits complete concertedness for the insertion of ozone into the O–H bond of oxalic acid (Figure S5) and, as expected, the reactivities of the carboxylic hydrogen atom in both formic and oxalic acids are similar, irrespective of the environment considered (ΔΔG‡ = 0.22 kcal mol–1 in the gas phase and 1.11 kcal mol–1 in water).

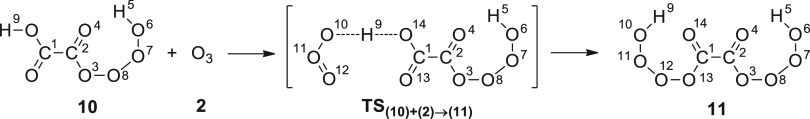

The attack of a second ozone molecule (2) to H9 of 10 leads to saddle point TS(10)+(2)→(11) [bond distance H9–O14 (1.27 Å in the gas phase and 1.36 Å in water); bond distance H9–O10 (1.14 Å in the gas phase and 1.09 Å in water); angle O14–H9–O10 (172° in both media); imaginary frequencies (927i cm–1 in the gas phase and 337i cm–1 in water)] in which the abstraction of H9 by O10 is accompanied by the formation of the O12–O13 bond (Scheme 6, Figure S6).

Scheme 6. Reaction of Tetraoxidane 10 with O3 to Give a Hydropolyoxidane Structure.

The decomposition of bis(tetraoxidane) 11 is a fast process starting with O4–O8 bond breaking and followed by the progressive scission of C1–C2, O12–O13, O6–O7, and O10–O11 bonds to form CO2 (4), two molecules of O2 (6), and two hydroxyl radicals (8) through the saddle point TS(11)→(4)+2(6)+2(8) [bond length O3–O8 (2.21 Å in the gas phase and 2.33 Å in water); imaginary frequencies (259i cm–1 in the gas phase and 215i cm–1 in water)] (Scheme 7, Figure S7).

Scheme 7. Decomposition of Bis(tetraoxidane) 11 to CO2, O2, and HO•.

Figure 2 and Figure S16 gather thermochemical data for the reaction of oxalic acid (9) with ozone (2). Computational simulations show that the decomposition of the bis(tetraoxidane) 11 takes place with similar energy barriers in both the gas phase and water (∼12 kcal mol–1).

Figure 2.

Relative free energies (ΔG, kcal mol–1) for all stationary points involved in the reaction of oxalic acid with ozone, at the UMN12SX/6-311++G(2d,p) level with bulk solvation in water (SMD method).

Reaction of Oxalic and Formic Acids with OH Radical

As mentioned in our introductory remarks, the oxidation of formic (1) and oxalic (9) acids with transient OH radicals generated by different AOP protocols, instead of the direct condensation with net ozone, has been taken into account for comparative purposes. The first step involves the reaction of HO• (8) with the carbonylic atom (H1) of HCOOH (1) (Scheme 8, Figure S8) yielding the radical species 12. The abstraction reaction of H1 by the hydroxyl radical is a fast step that proceeds through the formation of saddle point TS(1)+(8)→(12)+(5) (ΔG‡ = 8.51 kcal mol–1 in the gas phase and 10.33 kcal mol–1 in water). The structural parameters affected involve the H1–O6 (1.38 and 1.42 Å, respectively) and H1–C2 distances (1.19 and 1.18 Å, respectively), together with the angle C2–H1–O6 (162° and 170°, respectively) and have a lower imaginary frequency than those of ozonation reactions (582i cm–1 in the gas phase and 556i cm–1 in water).

Scheme 8. Reaction of Formic Acid with OH Radical.

Once radical 12 is formed, the collision of a new OH radical (8) with 12 generates carbonic acid (13) through a barrierless process, which is further transformed into CO2 and water via saddle point TS(13)→(4)+(5) (Scheme 9, Figure S9).

Scheme 9. Transformation of Radical 12 into CO2 and Water.

Alternatively, the reaction of OH radicals at the carboxylic acid terminus is shown in Scheme 10. The first step in which a reactive species (8) reacts with the H5 atom of HCOOH (1) produces another radical (14). As expected for this free-radical transformation, the saddle point TS(1)+(8)→(14)+(5) is quickly reached (ΔG‡ = 7.79 kcal mol–1 in the gas phase and 12.72 kcal mol–1 in water, as displayed in Figure 3 and Figures S10 and S17). Consistent with the different geometries of the aldehydic and carboxylic moieties, the latter now shows shorter H5–O6 (1.21 and 1.22 Å, respectively) and O4–H5 (1.20 and 1.19 Å, respectively) distances with characteristic angles O4–H5–O6 (155° and 156°) and O4–H5–O6–H7 (84° and 86°, respectively).

Scheme 10. Abstraction of Acid Proton H5 of Formic Acid by OH Radical.

Figure 3.

Relative free energy values (ΔG, kcal mol–1) of all stationary points involved in the reaction of formic acid with OH radical, at the UMN12SX/6-311++G(2d,p) level with inclusion of solvation effects in water (SMD method).

Next, the attack of a new OH radical (8) to hydrogen H1 of 14 leads to CO2 (4) and H2O (5) via saddle point TS(14)+(8)→(4)+(5), characterized by H5–O1 (1.39 Å in the gas phase and 1.34 Å in water) and H1–C2 (1.27 Å in the gas phase and 1.30 Å in water) bond distances, angle O5–H1–C2 (128° in the gas phase and 131° in water), dihedral angle H6–O5–H1–C2 (−75° in the gas phase and −84° in water) and one imaginary frequency of 690i cm–1 in the gas phase and 799i cm–1 in water (Scheme 11, Figure S11).

Scheme 11. Evolution of Radical 14 to CO2 and H2O.

Finally, the H-atom abstraction in oxalic acid (9) by the OH radical (8) follows a reactivity similar to that observed for formic acid (Scheme 12), through a fast and concerted process leading to TS(9)+(8)→(15)+(5) (ΔG‡ = 7.60 kcal mol–1 in the gas phase and 13.16 kcal mol–1 in water, with imaginary frequencies of 1748i and 1754i cm–1, respectively; Figures 4, S12 and S18), which enables the subsequent formation of radical 15. Optimized structures are scarcely modified with respect to the attack of either ozone or OH radical to the carboxylate residue. Thus, calculated bond lengths for O4–H5 (1.20 Å in both media) and H5–O6 (1.21 Å in both media), along with identical O4–H5–O6 angles (156° in both media) and dihedral angles O4–H5–O6–H7 (85° in the gas phase and 88° in water), arise from the computational analysis.

Scheme 12. Reaction of Oxalic Acid with OH Radical.

Figure 4.

Relative free energies (ΔG, kcal mol–1) of all stationary points through the reaction of oxalic acid with OH radical, at the UMN12SX/6-311++G(2d,p) level with solvation in water (SMD method).

The collision of H10 with a new hydroxyl radical (8) produces a diradical species (16) through the saddle point TS(15)+(8)→(16)+(5) [bond distances O11–H10 (1.20 Å in the gas phase and 1.17 Å in water) and H10–O9 (1.21 Å in the gas phase and 1.24 Å in water), angle O11–H10–O9 (155° in both media), dihedral angle H12–O11–H10–O9 (83° in the gas phase and 86° in water), and imaginary frequencies 1774i cm–1 in the gas phase and 1663i cm–1 in water, Figure S13]. Conversion of 16 into two molecules of CO2 takes place via saddle point TS(16)→2(4) [bond distances C1–C2 (1.91 Å in the gas phase and 1.88 Å in water), angles C1–C2–O3 (104° in the gas phase and 109° in water), dihedral angle O8–C1–C2–O3 (180° in both media), and imaginary frequencies 346i cm–1 in the gas phase and 279i cm–1 in water, Figure S14].

At this stage and in the context of hydrotrioxide chemistry,42 one could conjecture the intermediacy of such species by combining peroxy acid radicals and OH radicals because this pathway should likewise be plausible in the atmosphere. Nonetheless, as shown above, H-abstraction from organic acids should be the primary mechanism as formation of highly reactive hydroxyacyl and oxyacyl radicals is followed by essentially barrierless evolution to CO2 and H2O. It is obvious, however, that the present analysis focuses on ozonation and OH-based oxidation processes without taking into account the suite of different conditions, especially radiative or photochemical, which would permit secondary reaction channels.48 In line with experimental data gathered so far for gas-phase and aquatic reactions, H-abstraction mechanisms represent the main degradation routes of formic and oxalic acids, with competitive C–H and O–H cleavages depending on the parent substrate and the oxidizing agent as collected in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparative Reactivity (ΔΔG‡, kcal/mol)a of Formic and Oxalic Acids versus O3 and •OH.

| Reaction step | Gas phaseb | Waterb |

|---|---|---|

| Cleavage of the C–H bond in HCOOH | 15.11 | 14.65 |

| Cleavage of the O–H bond in HCOOH | 27.01 | 26.15 |

| Cleavage of the O–H bond in HOOC–COOH | 42.23 | 31.80 |

Calculated as ΔG‡(O3) – ΔG‡(•OH) at the UMN12SX/6-311++G(2d,p) level of theory.

Calculated from the reaction pathways involving the highest transition structures.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this theoretical study using an open-shell DFT method, throws light on the reactivity of formic and oxalic acids with ozone and OH radicals. Such oxidative processes result from anthropogenic activity (e.g., destruction of pollutants by AOPs) and have therefore environmental importance as these low-carbon organic acids are usually the final products of chemical degradation. From a mechanistic standpoint, the interaction with ozone involves the formation of linear and highly oxygenated structures (hydrotrioxides). The computer-aided exploration suggests the feasible generation of these otherwise counterintuitive polyoxygenated species through H-abstraction and insertion reactions, whose geometries and energies have been thoroughly characterized. While hydrotrioxides have long been known in aquatic chemistry, their intermediacy in atmospheric chemistry has been evidenced very recently, albeit involving the formation of peroxy radicals prior to reaction with OH radicals, and having lifetimes from hours to days.42 In general, our computational study reveals higher reactivities for both acids when oxidized by OH radicals. The relative reactivity of formic acid against O3 and HO• acid is essentially the same, regardless of the gas phase or in bulk aqueous solution (ΔΔG‡ = 0.46 and 0.86 kcal mol–1, respectively). As expected, C–H bond oxidation is more favorable than O–H bond cleavage for formic acid. Large variations emerge when one compares the thermodynamic data of OH bond cleavage in oxalic acid, for which the oxidation process is more favored in water.

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Junta de Extremadura and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (Grants IB16022, IB20026, GR21039, and GR21053) as well as the Agencia Estatal de Investigación, Spain (PID2019-104429RBI00/MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033), is warmly appreciated. We thank the Computaex Foundation and Cénits for the use of computational resources (Lusitania supercomputer). We also thank Dr. José Luis Jiménez for helpful suggestions and critical reading of this material.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jpca.2c08091.

IRC analyses for saddle points (Figures S1–S14), thermochemistry data in the gas phase (Figures S15–S18), and computational data for all optimized structures at the UMN12SX/6-311++G(2d,p) level in the gas phase and water using the SMD method (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of The Journal of Physical Chemistry virtual special issue “Early-Career and Emerging Researchers in Physical Chemistry Volume 2”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Beltrán F. J.Ozone Reaction Kinetics for Water and Wastewater Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk C.; Libra J. A.; Saupe A.. Ozonation of Water and Waste Water: A Practical Guide to Understanding Ozone and Its Applications, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Epelle E. I.; Emmerson A.; Nekrasova M.; Macfarlane A.; Cusack M.; Burns A.; Mackay W.; Yaseen M. Microbial Inactivation: Gaseous or Aqueous Ozonation?. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61 (27), 9600–9610. 10.1021/acs.iecr.2c01551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangel K.; Cabral F. O.; Lechuga G. C.; Carvalho J. P. R. S.; Villas-Bôas M. H. S.; Midlej V.; De-Simone S. G. Detrimental Effect of Ozone on Pathogenic Bacteria. Microorganisms 2022, 10 (1), 40. 10.3390/microorganisms10010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyama S. T. Chemical and Catalytic Properties of Ozone. Catal. Rev. 2000, 42 (3), 279–322. 10.1081/CR-100100263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He C.; Cheng J.; Zhang X.; Douthwaite M.; Pattisson S.; Hao Z. Recent Advances in the Catalytic Oxidation of Volatile Organic Compounds: A Review Based on Pollutant Sorts and Sources. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119 (7), 4471–4568. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J.; Xie Y.; Rabeah J.; Brückner A.; Cao H. Visible-Light Photocatalytic Ozonation Using Graphitic C3N4 Catalysts: A Hydroxyl Radical Manufacturer for Wastewater Treatment. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53 (5), 1024–1033. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.; Zhang H.; Wang F.; Xiong X.; Tian K.; Sun Y.; Yu T. Application of Heterogeneous Catalytic Ozonation for Refractory Organics in Wastewater. Catalysts 2019, 9 (3), 241. 10.3390/catal9030241. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes J.; Matos A.; Gmurek M.; Quinta-Ferreira R. M.; Martins R. C. Ozone and Photocatalytic Processes for Pathogens Removal from Water: A Review. Catalysts 2019, 9 (1), 46. 10.3390/catal9010046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X.; Wang B.; Zhu W.; Tian K.; Zhang H. A Review on Ultrasonic Catalytic Microbubbles Ozonation Processes: Properties, Hydroxyl Radicals Generation Pathway and Potential in Application. Catalysts 2019, 9 (1), 10. 10.3390/catal9010010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson D.; Marston G. The Gas-Phase Ozonolysis of Unsaturated Volatile Organic Compounds in the Troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008, 37 (4), 699–716. 10.1039/b704260b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray Bé A.; Upshur M. A.; Liu P.; Martin S. T.; Geiger F. M.; Thomson R. J. Cloud Activation Potentials for Atmospheric α-Pinene and β-Caryophyllene Ozonolysis Products. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3 (7), 715–725. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X.; Day D. A.; Krechmer J. E.; Brown W.; Peng Z.; Ziemann P. J.; Jimenez J. L. Direct Measurements of Semi-Volatile Organic Compound Dynamics Show near-Unity Mass Accommodation Coefficients for Diverse Aerosols. Commun. Chem. 2019, 2 (1), 98. 10.1038/s42004-019-0200-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anglada J. M.; Martins-Costa M.; Ruiz-López M. F.; Francisco J. S. Spectroscopic Signatures of Ozone at the Air-Water Interface and Photochemistry Implications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111 (32), 11618–11623. 10.1073/pnas.1411727111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meidan D.; Brown S. S.; Rudich Y. The Potential Role of Criegee Intermediates in Nighttime Atmospheric Chemistry. A Modeling Study. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2017, 1 (5), 288–298. 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.7b00044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long B.; Bao J. L.; Truhlar D. G. Unimolecular Reaction of Acetone Oxide and Its Reaction with Water in the Atmosphere. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115 (24), 6135–6140. 10.1073/pnas.1804453115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhantyal-Pun R.; Rotavera B.; Mcgillen M. R.; Khan M. A. H.; Eskola A. J.; Caravan R. L.; Blacker L.; Tew D. P.; Osborn D. L.; Percival C. J.; et al. Criegee Intermediate Reactions with Carboxylic Acids : A Potential Source of Secondary Organic Aerosol in the Atmosphere. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2018, 2 (8), 833–842. 10.1021/acsearthspacechem.8b00069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newland M. J.; Nelson B. S.; Muñoz A.; Ródenas M.; Vera T.; Tárrega J.; Rickard A. R. Trends in Stabilisation of Criegee Intermediates from Alkene Ozonolysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22 (24), 13698–13706. 10.1039/D0CP00897D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube H. II. Chain Reactions of Ozone in Aqueous Solution. The Interaction of Ozone and Formic Acid in Aqueous Solution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1941, 63 (9), 2453–2458. 10.1021/ja01854a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey P. S. The Reactions Of Ozone With Organic Compounds. Chem. Rev. 1958, 58 (5), 925–1010. 10.1021/cr50023a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aristova N. A.; Leitner N. K. V.; Piskarev I. M. Degradation of Formic Acid in Different Oxidative Processes. High Energy Chem. 2002, 36 (3), 197–202. 10.1023/A:1015385103605. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton G. V.; Greenstock C. L.; Helman W. P.; Ross A. B. Critical Review of Rate Constants for Reactions of Hydrated Electrons, Hydrogen Atoms and Hydroxyl Radicals (·OH/·O−) in Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1988, 17 (2), 513–886. 10.1063/1.555805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoigné J.; Bader H. Rate Constants of Reactions of Ozone with Organic and Inorganic Compounds in Water-II: Dissociating Organic Compounds. Water Res. 1983, 17 (2), 185–194. 10.1016/0043-1354(83)90099-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staehelin J.; Hoigné J. Decomposition of Ozone in Water: Rate of Initiation by Hydroxide Ions and Hydrogen Peroxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1982, 16 (10), 676–681. 10.1021/es00104a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet R.; Bourbigot M.; Dore M. Oxidation of Organic Compounds through the Combination Ozone-Hydrogen Peroxide. Ozone Sci. Eng. 1984, 6 (3), 163–183. 10.1080/01919518408551019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yapsakli K.; Can Z. S. Interaction of Ozone with Formic Acid: A System Which Supresses the Scavenging Effect of HCO3−/CO32−. Water Qual. Res. J. 2004, 39 (2), 140–148. 10.2166/wqrj.2004.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Linde C.; Tang W. K.; Siu C. K.; Beyer M. K. Electrons Mediate the Gas-Phase Oxidation of Formic Acid with Ozone. Chem.—Eur. J. 2016, 22 (36), 12684–12687. 10.1002/chem.201603080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehested K.; Getoff N.; Schwoerer F.; Markovic V. M.; Nielsen S. O. Pulse Radiolysis of Oxalic Acid and Oxalates. J. Phys. Chem. 1971, 75 (6), 749–755. 10.1021/j100676a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen A.; Tuhkanen T.; Kalliokoski P. Treatment of TCE- and PCE Contaminated Groundwater Using UV/H2O2 and O3/H2O2 Oxidation Processes. Water Sci. Technol. 1996, 33 (6), 67–73. 10.2166/wst.1996.0082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S.; Shiraishi F.; Nakano K. A Synergistic Effect of Photocatalysis and Ozonation on Decomposition of Formic Acid in an Aqueous Solution. Chem. Eng. J. 2002, 87 (2), 261–271. 10.1016/S1385-8947(02)00016-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán F. J.; Rivas F. J.; Fernández L. A.; Álvarez P. M.; Montero-de-Espinosa R. Kinetics of Catalytic Ozonation of Oxalic Acid in Water with Activated Carbon. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41 (25), 6510–6517. 10.1021/ie020311d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán F. J.; Rivas F. J.; Montero-de-Espinosa R. Ozone-Enhanced Oxidation of Oxalic Acid in Water with Cobalt Catalysts. 1. Homogeneous Catalytic Ozonation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2003, 42 (14), 3210–3217. 10.1021/ie0209982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.; Trucks G. W.; Schlegel H. B.; Scuseria G. E.; Robb M. A.; Cheeseman J. R.; Scalmani G.; Barone V.; Petersson G. A.; Nakatsuji H.; et al. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT: 2016.

- Peverati R.; Truhlar D. G. Screened-Exchange Density Functionals with Broad Accuracy for Chemistry and Solid-State Physics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14 (47), 16187–16191. 10.1039/c2cp42576a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peverati R.; Truhlar D. G. Exchange–Correlation Functional with Good Accuracy for Both Structural and Energetic Properties While Depending Only on the Density and Its Gradient. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8 (7), 2310–2319. 10.1021/ct3002656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francl M. M.; Pietro W. J.; Hehre W. J.; Binkley J. S.; Gordon M. S.; DeFrees D. J.; Pople J. A. Self-consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XXIII. A Polarization-type Basis Set for Second-row Elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 77 (7), 3654–3665. 10.1063/1.444267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Performance of SM6, SM8, and SMD on the SAMPL1 Test Set for the Prediction of Small-Molecule Solvation Free Energies. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113 (14), 4538–4543. 10.1021/jp809094y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marenich A. V.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Universal Solvation Model Based on Solute Electron Density and on a Continuum Model of the Solvent Defined by the Bulk Dielectric Constant and Atomic Surface Tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113 (18), 6378–6396. 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar M.; Sinha A.; Francisco J. S. Role of Double Hydrogen Atom Transfer Reactions in Atmospheric Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49 (5), 877–883. 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plesničar B. Progress in the Chemistry of Dihydrogen Trioxide (HOOOH). Acta Chim. Slov. 2005, 52 (1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cerkovnik J.; Plesničar B. Recent Advances in the Chemistry of Hydrogen Trioxide (HOOOH). Chem. Rev. 2013, 113 (10), 7930–7951. 10.1021/cr300512s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt T.; Chen J.; Kjærgaard E. R.; Møller K. H.; Tilgner A.; Hoffmann E. H.; Herrmann H.; Crounse J. D.; Wennberg P. O.; Kjaergaard H. G. Hydrotrioxide (ROOOH) Formation in the Atmosphere. Science 2022, 376 (6596), 979–982. 10.1126/science.abn6012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giamalva D. H.; Church D. F.; Pryor W. A. Kinetics of Ozonation. 5. Reactions of Ozone with Carbon-Hydrogen Bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986, 108 (24), 7678–7681. 10.1021/ja00284a035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereecken L.; Francisco J. S. Theoretical Studies of Atmospheric Reaction Mechanisms in the Troposphere. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41 (19), 6259–6293. 10.1039/c2cs35070j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerkovnik J.; Plesničar B.; Koller J.; Tuttle T. Hydrotrioxides Rather than Cyclic Tetraoxides (Tetraoxolanes) as the Primary Reaction Intermediates in the Low-Temperature Ozonation of Aldehydes. The Case of Benzaldehyde. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74 (1), 96–101. 10.1021/jo801594n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mckay D. J.; Wright J. S. How Long Can You Make an Oxygen Chain?. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120 (5), 1003–1013. 10.1021/ja971534b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wurmel J.; Simmie J. M. H-Atom Abstraction Reactions by Ground-State Ozone from Saturated Oxygenates. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121 (42), 8053–8060. 10.1021/acs.jpca.7b07760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Although ozonation and

oxidation with OH radicals have been evaluated independently through

this manuscript, one reviewer suggested the combined use of both ozone

and OH. Clearly this premise would require different experimental

conditions (e.g., Fenton-like processes, photocatalysis, etc.) in

order to sustain a comparable concentration of both species, and so

it is beyond the scope of this study. Even so, the point is worthwhile

and we computed the reaction of O3 and OH radicals in the

gas phase. The resulting O4H radical constitutes a stable

intermediate, capable of reacting with formic acid through aldehydic

hydrogen abstraction (see scheme below). However, this process shows

an energy barrier of 29.16 kcal/mol, higher than that described for

the reactions of ozone (23.62 kcal/mol) and OH radical (8.51 kcal/mol).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.