Abstract

Cancer cell membranes (CCMs) are widely used as sources of tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) for the development of cancer vaccines. To improve the CCM-associated cancer vaccine efficiency, personalized cancer vaccines and effective delivery systems are required. In this study, we employed surgically harvested cancer tissues to prepare personalized CCMs for use as TAAs. Thioglycolic-acid-grafted poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-block-poly(2-butyl-2-oxazoline-co-2-butenyl-2-oxazoline) (PMBEOx-COOH) was synthesized to load imiquimod (R837) efficiently. The personalized CCMs were then coated onto R837-loaded PMBEOx-COOH nanoparticles (POxTA NPs/R837) to obtain surgically derived CCM-coated POxTA NPs (SCNPs/R837). SCNPs/R837 efficiently travelled to the draining lymph nodes and were taken up and presented by plasmacytoid dendritic cells to elicit enhanced antitumor immune responses. When combined with programmed cell death-1 antibodies, SCNPs/R837 exhibited high efficiency corresponding to antitumor progression. Therefore, SCNP/R837 might represent a promising personalized cancer vaccine with significant potential for cancer immunotherapy.

Keywords: poly(2-oxazoline), nanoparticle, surgically derived cancer cell membrane, cancer immunotherapy, cancer vaccine

Introduction

Alongside the rise in cancer immunotherapy, current cancer therapy is developing rapidly. The development of precision medicine promotes the provision of more suitable individual treatments based on the comprehensive analysis of tumors and their microenvironment.1 Cancer immunotherapy aims to stimulate the body’s own immune system to induce antitumor responses. In most approaches that trigger antitumor immunity, the first step is delivering tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) to antigen-presenting cells (APCs), such as dendritic cells (DCs), which then present TAAs to cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) and T-helper lymphocytes. CTLs and innate immune cells, including natural killer (NK) cells, gather at the tumor sites to target and eliminate tumor cells. Indeed, DCs play a significant role in this process. In particular, plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) arise from lymphoid progenitor cells and are found throughout the body within the lymph nodes (LNs), spleen, thymus, and bone marrow, where they are stimulated by Toll-like receptor (TLR)7 and TLR9. However, most pDCs within the tumor microenvironment are not activated. As such, pDCs are associated with the development and maintenance of an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. Meanwhile, recent studies have indicated that pDC stimulation can induce tumor regression.2−8

The main categories of cancer immunotherapy include cancer vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, immunomodulators, cell-based immunotherapies, immune checkpoint blockade therapies, and oncolytic virus immunotherapies.1,9,10 In particular, cancer vaccines are a promising strategy that inhibit tumor progression by eliciting antitumor immune responses.11,12 To achieve potent antitumor immune responses, sufficient TAAs and immunostimulatory adjuvants are indispensable in preparing cancer vaccines.13,14 Although single TAAs have been employed as the antigenic components of cancer vaccines, the efficiency of cancer vaccines is limited by potential mutation of tumor cells, which further influences their clinical application. To avoid the limitation of a single TAA cancer vaccine, multiple TAAs, such as tumor cell lysates (TCLs), have been explored. However, TCL-associated cancer vaccines have certain inherent limitations; given that non-antigenic components comprise a significant proportion of TCLs, they can yield inefficient cancer inhibition.15 As an alternative, cancer cell membranes (CCMs) have been studied as a TAA source for cancer vaccines when combined with immunostimulatory adjuvants,16,17 both of which are typically delivered using nanotechnology. We previously developed CCM-coated poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles (MANPs) loaded with imiquimod (R837), as an immune adjuvant. MANPs with different particle sizes were also explored to demonstrate the influence of nanoparticle size on immune efficacy. Smaller MANPs were found to elicit more efficient anticancer immune responses compared with larger particles.18

However, sections corresponding to neoantigens derived from CCMs differ among individuals, rendering cell-line-derived CCMs (CLMs) unsuitable to act as antigenic components of cancer vaccines. Meanwhile, surgical interventions represent the primary treatment strategy for most solid cancers. The removed cancers possess important information regarding mutation of genes that function as neoantigens, as well as the metabolism checkpoint signature. Thus, TAAs of the removed cancers are specific to the patient, and surgically derived CCMs (SCMs) may possess more appropriate and specific TAA profiles compared with CLMs. Therefore, to prepare individual cancer vaccines, SCMs might be more appropriate as TAA sources.19−21 A sufficient dose of immunostimulatory adjuvants is necessary to elicit efficient anticancer immune responses, which can be delivered most effectively via small immune-modulated nanoparticles. Among the polymer nanomaterials, poly(2-oxazoline) (POx)-based block copolymers have attracted considerable attention due to their excellent biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity.22,23 Moreover, amine-containing drugs, for example, R837, are more easily loaded by POx with carboxyl groups.24 Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) is also approved as a food additive by the US Food and Drug Administration.25

In the current study, we synthesized thioglycolic-acid-grafted poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-block-poly(2-butyl-2-oxazoline-co-2-butenyl-2-oxazoline) (PMBEOx-COOH). PMBEOx-COOH can load R837 efficiently, thus, effectively reducing the side effects caused by the high dose of excipients. To combine the advantages of SCMs, as the antigen, and PMBEOx-COOH, as the delivery system, we loaded R837 into PMBEOx-COOH nanoparticles (POxTA NPs) to obtain PMBEOx-COOH NPs/R837 (POxTA NPs/R837). Subsequently, SCMs were coated onto POxTA NPs/R837 to obtain SCM-coated POxTA NPs (SCNPs/R837), which were found to efficiently deliver TAAs and R837 to the resident pDCs of draining LNs and elicit enhanced anticancer immune responses. Moreover, when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as programmed cell death-1 (PD1) antibodies, SCNPs/R837 exhibited strong potential as a therapeutic agent (Scheme 1). Hence, the findings of this study support the application of PMBEOx-COOH as an efficient delivery system, and SCMs as effective TAAs, to obtain a potent personalized cancer vaccine for cancer immunotherapy.

Scheme 1. Schematic of the Preparation Process, Structure, and Anticancer Mechanism of SCNP/R837.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of PMBEOx-COOH

Briefly, methyl trifluoromethylsulfonate (0.1 mmol, 16.0 mg, MeOTf) was dissolved by anhydrous acetonitrile (6.5 mL) in an atmosphere containing dry argon. 2-methyl-2-oxazoline (7.0 mmol, 0.6 g, MeOx) was added dropwise to the MeOTf solution and stirred for 24 h at 70 °C. Once the mixture was refrigerated to room temperature, 2-butyl-2-oxazoline (250.0 mg, 1.96 mmol) and 2-(3-butenyl)-2-oxazoline (1.36 mmol, 170.0 mg) were added dropwise, and the reaction solution was stirred for 48 h at 70 °C. After the blend was purified using the dialysis method for 48 h against distilled water, the products were obtained by lyophilization. The following modification was performed in a quartz bottle. The resulting products (0.5 mmol, 455.0 mg) were dissolved in 5.0 mL of anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide, and nitrogen was used to create an anaerobic condition by bubbling through the blend for 10 min. After thioglycolic acid (10.0 mmol, 0.9 mg) and irgacure 2959 (0.5 mmol, 0.1 mg) were added to the blend, the nitrogen bubbling was continued for 10 min. Subsequently, the blend was sealed to isolate oxygen and irradiated with 365 nm ultraviolet light for another 1 h. The final product was purified via dialysis against water for 2 days, and the resulting PMBEOx-COOH was regained through lyophilization (yield: 300.9 mg, 65.6%).24

Preparation of CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837

R837-loaded PMBEOx-COOH nanoparticles (POxTA NPs/R837) were prepared using the thin-film method. PMBEOx-COOH (120 mg) and R837 (10 mg) were solubilized in acetonitrile. The acetonitrile was removed to obtain a thin film, which was dissolved by deionized water. The insoluble drug was separated through filtration to obtain the POxTA NP/R837 solution.

The extrusion approach was used to obtain the RM-1 prostate cancer cell line-derived CCM-coated POxTA NPs (CLNPs/R837) and SCNPs/R837. CLMs of the RM-1 prostate cancer cells were prepared following a previously reported protocol.18 To obtain SCMs, isolated RM-1 tumors were cut into pieces and digested with a mixture of collagenase D (250 μg mL–1, Roche, Switzerland) and DNase I (20 μg mL–1, Roche, Switzerland) at 37 °C for 50 min. The isolated cells were filtered, collected, and grown in cell culture dishes until achieving confluence. During this period, the cells were washed using sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove the suspended residual stromal cells. The following protocol was used to obtain the CLMs and SCMs. The harvested cancer cells were copied with a hypotonic lysis buffer comprising 2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 20 mM tris–HCl (pH 7.5), and one EDTA-free mini protease inhibitor tablet per 10.0 mL of solution at 4 °C for 2 h. The obtained solution was centrifuged for 5 min at 4000g to collect the supernatant, which was then centrifuged for an additional 20 min at 20,000g. The supernatant was again collected and further centrifugated for 50 min at 100,000g. The resulting pellet was washed with the prepared solution (10.0 mM Tris–HCl, 1.0 mM EDTA, pH = 7.5) to obtain purified CCM.

To coat the CCM onto the nanoparticles, it was sequentially extruded through a 400 nm polycarbonate membrane 10 times to obtain CCM vesicles. The CCM vesicles were mixed with POxTA NP/R837 and physically crowded through a 200 nm polycarbonate membrane 10 times. The CCM-coated nanoparticles were fabricated with doses of 200.0 μg POxTA NP/R837 and CCM containing 100.0 μg of membrane protein.

Characterization of Nanoparticles

NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker AV 300 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) at room temperature. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy was performed with a Bio-Rad Win-IR instrument (Bio-Rad, USA) using the KBr method. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using a Waters e2695 HPLC system to detect R837 concentrations in different nanoparticles. The sample injection volume was 20 μL. The mobile phase was a blend of acetonitrile and 0.02 M K2HPO4 aqueous solution at a ratio of 7:3 (v/v). The UV detection wavelength was set at 245 nm. The drug-loading capacity (DLCs) and drug-loading efficiency (DLEs) were calculated using eqs 1 and 2. The hydrodynamic diameters of different nanoparticles were measured by the dynamic light scattering method employing a Malvern Zetasizer instrument (Malvern, Britain) at a concentration of 1.0 mg mL–1.

The morphologies of the nanoparticles were evaluated using a transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-1011, Japan). The TEM samples were prepared as follows: small drops of different nanoparticle solutions at a concentration of 100.0 μg mL–1 were deposited onto 400-mesh copper grids. After drying at room temperature, the TEM samples were stained with 2.0% phosphotungstic acid. For protein characterization by gel electrophoresis, the protein content of all samples was detected using the BCA assay. Samples with the same amount of protein were loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie Blue and destained overnight using water before imaging with Gel Doc XR+ (Bio-Rad).

| 1 |

| 2 |

where Wdrug and Wnanoparticle indicate the weight of the drug in the nanoparticle and the weight of the individual nanoparticle, while Wdrugfeeding refers to the weight of the drug added during the preparation of the nanoparticle.

Isolation and Culture of pDCs

Murine pDCs were isolated from the bone marrow of mice treated with Flt3L. Bone marrow cells (BMCs) were acquired from the tibiae and femora 10 days after injection of pORF-mFlt3L (10 μg). After incubation with rat CD16/32 antibodies to block nonspecific binding, BMCs were stained with CD11c, B220, and CD11b antibodies. BD FACSAria (BD Biosciences, USA) was used to sort pDCs with the CD11c+CD11b–B220+ phenotype. The isolated pDCs were cultured at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells mL–1 in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol.26

Cell Lines and Animals

The murine prostate cancer RM-1 cell line was cultured at 37 °C with 5% (v/v) carbon dioxide (CO2) in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS and 1% (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin. 5 week old male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Beijing, China). All animal experiments were performed according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Jilin University (no. 20200243).

Cellular Uptake and In Vivo Fluorescence Imaging

Tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate (DiD, excitation/emission: 644/665 nm)-labeled POxTA NPs (POxTA NPs/DiD) were obtained using the thin-film method. CCM-coated POxTA NPs/DiD were fabricated via physical extrusion, and each nanoparticle solution was diluted to the same fluorescence intensity. DiD-labeled nanoparticle solutions (200 μL) were cultured with 5 × 105 pDCs in a 12-well plate for 12 h. The nucleus was stained by DAPI at 37 °C for 5 min. The cellular uptake of different DiD-labeled nanoparticles was detected using fluorescence cytometry (FCM; FACSCanto cytometer, BD Biosciences, USA) and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM; FLUOVIEW FV3000, OLYMPUS, Japan). For in vivo fluorescence imaging, POxTA NPs/DiD, CLNPs/DiD, or SCNPs/DiD solution (100.0 μL) was injected intradermally into the flanks of C57BL/6J mice. The draining LNs were isolated at different times after injection (2, 12, 24, and 48 h), and fluorescence images were captured using IVIS Lumina XR (Caliper Life Sciences, USA).

In Vitro Maturation Assays

pDCs were cultured in a 12-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 pDCs per well. Nanoparticle formulations (200 μL) with POxTA NPs/R837 (1.0 mg mL–1) were added to each well. The percentage of mature pDCs was analyzed using FCM after incubating for 24 h. The culture supernatants were collected and analyzed using cytokine-specific enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for IFN-α, IL-6, and IL-12.

In Vivo Immune Response Assays

PBS, POxTA NPs/R837, CLNPs/R837, and SCNPs/R837 were administered intradermally three times at an interval of 2 days. Three mice from each group were euthanized on the fifth day after the last immunization by CO2 asphyxiation and euthanized by cervical dislocation. LNs were then isolated to determine the amount of pDCs and the percentage of mature pDCs by FCM.

Tumor Prevention and Treatment

The nanovaccine formulations (100 μL) with POxTA NPs/R837 (3.0 mg mL–1) were administered to the C57BL/6J mice (5–6 weeks old) on day −9, −7, and −5. The mice were challenged with 1.0 × 105 RM-1 prostate cancer cells via subcutaneous injection into the right flank on day 0. The tumor volumes and changes in body weight were monitored every other day. The tumor volumes were calculated using eq 3.

| 3 |

where V (mm3) represents the tumor volume and L and W represent the length and width of each tumor (mm), respectively.

To detect the effect of the treatment of the different nanoparticle formulations combined with the PD-1 antibody, 1.0 × 105 RM-1 prostate cancer cells were subcutaneously injected in the right flank of C57BL/6J mice (5–6 weeks old) on day 0. In the vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group, SCNPs were administered to the mice 5 days before being introduced to a challenge with RM-1 cells. On days 3, 5, and 7, the mice were injected with various nanoparticle formulations. On these days, mice in the SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 and vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 groups were injected with anti-PD-1 (RMP1-14, 100.0 μg) intraperitoneally. Tumor volumes and changes in body weight were noted every other day.

Isolation of Tumor-Infiltrating Leukocytes

The isolated RM-1 tumor tissues were cut into pieces using a scalpel in RPMI-1640 medium containing 1% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and digested with collagenase D (250 μg mL–1) and DNase I (20 μg mL–1) at 37 °C for 50 min. The cell suspensions were then filtrated with a cell strainer with a pore size of 100 μm, collected, and incubated with red blood cell lysis buffer. The obtained cells were stained and analyzed by FCM.2

Statistical Analysis

Statistical data are represented as the average ±standard deviation (SD). Data from different groups were analyzed for statistical significance by employing the Student t test. The log-rank test was used to analyze survival curves. Significance was indicated by p < 0.05, and p < 0.01 and p < 0.001 were considered to indicate significance.

Results and Discussion

PMBEOx-COOH was synthesized, as described in our previous study.24 The structure of PMBEOx-COOH was confirmed by 1H NMR (Figure S4). To load the R837 onto the POxTA NPs, the thin-film method was used, and the DLC and DLE were resolved to be approximately 6.1 and 77.6%, respectively. PMBEOx-COOH exhibits substantially higher DLC compared to other nanomaterials such as PLGA.27,28 The DLC and DLE were determined using HPLC. In the in vitro R837 release study, the release of R837 from POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 was controlled and sustained at both pH 7.4 and pH 5.5. Furthermore, the release of R837 from POxTA NP/R837 was accelerated when the PBS pH was changed from 7.4 to 5.5, and the release of R837 from CCM-coated nanoparticles was slightly slower than that from naked nanoparticles (Figure S5). In addition, the stabilities of POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 were studied by monitoring the diameters of nanoparticles in PBS at 25 °C. It was indicated that POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 in PBS at pH 7.4 and 25 °C exhibited stable sizes within 72 h (Figure S6).

SCMs were procured from surgical tumors of RM-1 prostate cancer cell-bearing mice to prepare SCNPs/R837. The cell-line-derived CCMs were collected from RM-1 prostate cancer cells and designated as CLMs. A physical extrusion method using porous polycarbonate membranes was used to coat SCMs or CLMs onto POxTA NPs/R837 to obtain SCNPs/R837 and CLNPs/R837. After the naked nanoparticles were coated with these CCMs, dynamic light scattering was employed to detect nanoparticle sizes, indicating that the nanoparticle diameters increased by about 20 nm from the naked nanoparticle diameters of approximately 30 nm (Figure 1A). Furthermore, the surface potential of the naked nanoparticles was near 0 mV (Figure 1B). After being coated with CLMs and SCMs, the surface potential decreased to approximately −7 mV, indicating that nanoparticles were successfully coated by CCMs.29 TEM was also used to verify the successful coating of CCMs onto the nanoparticles, revealing the core–shell structures of CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 (Figure 1C). Protein components of CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 were detected by gel electrophoresis. CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 exhibited similar protein profiles to CLMs and SCMs (Figure 1D). The results indicated that CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 could be functionalized by the TAAs on CCMs. Interestingly, SCMs possessed a protein profile similar to that of CLMs, likely due to the SCMs being derived from RM-1 tumors, primarily composed of RM-1 prostate cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Nanovaccine characterization. (A) Sizes of POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837. (B) ζ potential of POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837. (C) TEM images of POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 negatively stained by 2% phosphotungstic acid. (D) Protein analysis of TCL, CLM, SCM, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 via gel electrophoresis. Samples with equivalent protein concentrations were evaluated and stained using Coomassie brilliant blue.

The efficient migration of cancer vaccines to draining LNs and their uptake by APCs greatly contribute to eliciting anticancer immune responses.27 DiD-labeled POxTA NPs (POxTA NPs/DiD), CLNPs/DiD, and SCNPs/DiD were assessed via CLSM, FCM, and an in vivo imaging system to investigate the pDC internalization and in vivo migration of different nanoparticles. POxTA NPs/DiD, CLNPs/DiD, and SCNPs/DiD were efficiently consumed by pDCs in vitro, with no significant differences in the cellular uptake between various nanoparticles (Figure 2A,B). CLSM results confirmed the same phenomenon (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Transmission of the adjuvant and antigen in vitro and in vivo. (A,B) Uptake of POxTA NP/DiD, CLNP/DiD, and SCNP/DiD by pDCs in vitro, as determined by FCM. (C) CLSM images of pDCs incubated with POxTA NP/DiD, CLNP/DiD, and SCNP/DiD. (D) Fluorescent images of isolated axillary LNs collected at different times after injection of POxTA NP/DiD, CLNP/DiD, and SCNP/DiD.

We then detected the nanoparticle drainage to draining LNs in vivo. To this end, different DiD-labeled fluorescent nanoparticles were intradermally injected into the right flanks of mice. Then, draining LNs were isolated for in vivo fluorescent imaging after 2, 12, 24, and 48 h. Although fluorescent nanoparticles were observed to have drained to the LNs at 2 h, the fluorescence was markedly stronger at 12 h (Figure 2D and S7). Interestingly, there were no obvious differences between the POxTA NPs/DiD, CLNPs/DiD, and SCNPs/DiD groups, possibly because of the diameters of POxTA NPs/DiD and membrane-coated nanoparticles (approximately 30 and 50 nm, respectively), which is sufficiently small for efficient accumulation at draining LNs. The efficient drainage of small nanoparticles weakened the influence of the nanoparticle diameter on the draining efficiency in vivo.30,31

To enquire into the immune stimuli of nanovaccine formulations on pDCs, purified pDCs were harvested from the bone marrow of mice, which were administered with Flt3L-encoding plasmid DNA intravenously.32 The purity of the isolated pDC population was more than 90%. The obtained pDCs were then incubated with POxTA NPs/R837, CLNPs/R837, and SCNPs/R837, and the expression of CD86 and MHC II was detected on the pDCs via FCM (Figure 3A–D). It was found that the nanovaccine formulations could induce pDC maturation. Moreover, no significant difference was observed between CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 on pDC maturation in vitro. POxTA NPs/R837 exhibited an effect similar to that of CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 in pDC maturation in vitro. Cytokine secretion by pDCs was also investigated. The nanovaccine formulations triggered enhanced interferon-α (IFN-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-12 secretion (Figure 3E–G). These results verified that the nanovaccine formulation, particularly CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837, could induce pDC maturation and activation.

Figure 3.

In vitro pDC activation effect of PBS, POxTA NPs/R837, CLNPs/R837, or SCNPs/R837. (A–D) Analysis of pDC maturation markers CD86 and MHC II after incubation with different nanovaccines. (E–G) Secretion of IFN-α, IL-6, and IL-12 from pDCs treated with different nanovaccine formulations. Data are presented as average ± SD (n = 3; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

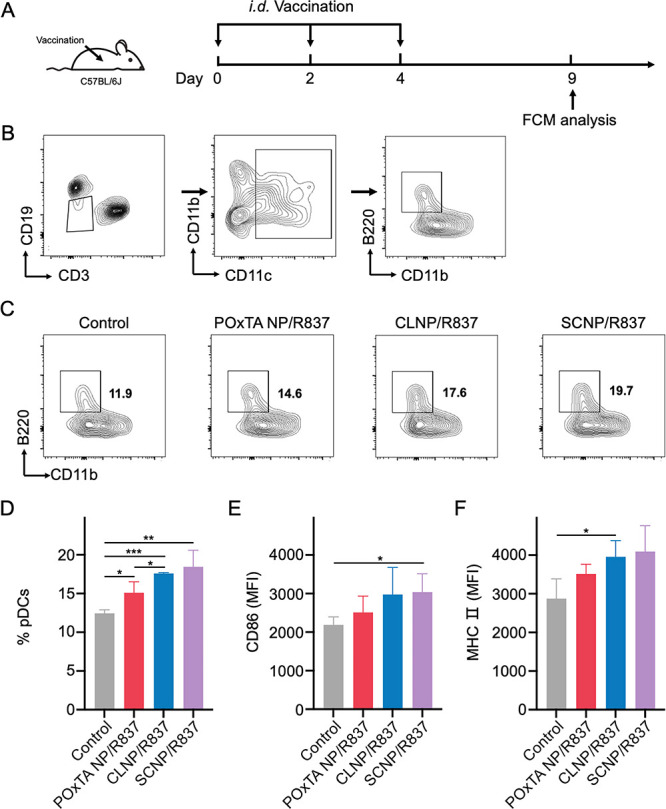

We further investigated the effects of nanovaccine formulations on immune stimulation. The pDC maturation ratio in draining LNs after three vaccine administrations was investigated using FCM (Figure 4A). The gating strategy for pDCs is shown in Figure 4B, and pDC ratio and typical markers, that is, CD86 and MHC II, were detected (Figure 4C–F). The pDC ratio in draining LNs was found to substantially increase after 5 days of three administrations in the CLNP/R837 and SCNP/R837 groups. Furthermore, the mean fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of CD86 (an active marker of pDCs) on pDCs in the CLNP/R837 and SCNP/R837 groups were substantially higher than the control and POxTA NP/R837 groups. The MFI of MHC II exhibited a similar trend. These results indicated that the combination of CCMs and R837 via PMBEOx-COOH could provide an effective immune-stimulating nanovaccine to induce potent immune responses in vivo.

Figure 4.

Characterization of in vivo immune stimulation. (A) Schematics of the immune treatment and FCM analysis. (B) Gating strategy for pDCs. (C,D) Infiltration of pDCs/CD3–CD19–CD11c+ cells. (E,F) Analysis of (E) CD86 and (F) MHC II pDC markers. Data are presented as average ± SD (n = 3; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01).

We also investigated the influence of nanovaccine formulations on systemic immunity. The titers of IL-6 and IL-12 in immunized mouse sera were detected through ELISA, and no significant difference was observed among the groups (Figure S9). Furthermore, the weight of mice did not significantly differ under different treatments (Figures S10,S12). These results implied that the systemic immunotoxicity of the prepared nanovaccines was mild. Meanwhile, FCM quantitative analysis of aqua stain indicated that the nanovaccine formulations exhibited relatively no cytotoxicity (Figure S8).

The prophylactic effects of different nanovaccine formulations in vivo were evaluated in the RM-1 prostate cancer model. PBS, POxTA NPs/R837, CLNPs/R837, or SCNPs/R837 was administered to the C57BL/6J mice three times at an interval of 2 days and challenged with RM-1 prostate cancer cells 5 days after the last immunization (Figure 5A). CLNPs/R837 and SCNPs/R837 were found to significantly inhibit tumor progression (Figure 5B,D). The median survival of the SCNP/R837 group was extended to 40 days compared to 26 days in the control group (Figure 5C). These results indicate that combining CCMs as TAAs and immune adjuvants via nanomaterial-based delivery systems can induce effective antitumor immune responses and achieve cancer immunotherapy. Interestingly, no significant difference was observed between the CLNP/R837 and SCNP/R837 groups. A possible reason for this is that the protein profile of the SCMs was similar to that of the CLMs. However, this does not imply that SCMs as TAAs in nanovaccines are redundant. The SCMs were obtained from isolated mouse prostate cancers, suggesting that it is possible to prepare SCNPs/R837 nanovaccines from SCMs obtained from tumors removed from patients via surgery.

Figure 5.

Prophylactic effects of different nanovaccine formulations. (A) Schematics of the immune treatment and tumor challenge. (B) Tumor volume of RM-1 tumors in C57BL/6J mice after treatment with POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, or SCNP/R837. (C) Survival curve of RM-1 tumor-bearing mice in various groups. (D) Individual tumor growth kinetics. FCM quantitative analysis of (E,F) CD8+ T cells/CD45+ cells and (G–I) NK cells/CD45+ cells and NKG2D on NK cells derived from the mice bearing RM-1 tumors after different treatments. Data are presented as average ± SD (n = 6 for B, n = 3 for F, H, and I; **p < 0.01, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

To determine the mechanisms of tumor inhibition by nanovaccines, tumors in immunized mice were isolated. FCM and immunohistochemistry were employed to detect tumor infiltration by CD8+ T cells and NKG2D+ NK cells after vaccination. More CD8+ T and NK cells were detected in the tumor microenvironment of the SCNP/R837 group than that in the control group (Figures 5E–I; S11). Furthermore, FCM results revealed that the MFI of NKG2D (an active marker of NK cells) on NK cells in the CLNP/R837 and SCNP/R837 groups was higher than the control and POxTA NP/R837 groups. We also detected tumor infiltration of regulatory T cells (Tregs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and determined that fewer Tregs and TAMs were present within the tumor microenvironments of CLNP/R837 and SCNP/R837 groups compared with those in the control group (Figure S11). These results indicated that our vaccine formulations could activate pDCs, causing subsequent enhancement of CD8+ T and NKG2D+ NK cell infiltration following vaccination, thus representing an important antitumor effect of our nanovaccine formulations.

We further investigated the therapeutic efficacy of the various nanovaccine formulations. SCNPs/R837 was administered to mice 5 days before being challenged with RM-1 prostate cancer cells in the vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group (Figure 6A). Mice were treated with cancer cells on day 0 and then administered with different treatment strategies on days 3, 5, and 7. In the SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 and vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 groups, mice were also intraperitoneally injected with anti-PD1. It was found that SCNP/R837 inhibited tumor progression and prolonged overall survival (Figure 6B–D). When combined with anti-PD1, SCNP/R837 exhibited enhanced therapeutic efficacy. In addition, tumor volume did not differ significantly between SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 and vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 groups. However, there were more tumor-free mice in the vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group than that in the SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group, indicating that the combination of SCNP/R837 as a vaccine and therapeutic agent exhibited improved anticancer efficacy (Figure 6D).

Figure 6.

Therapeutic efficacy of different nanovaccine formulations. (A) Schematics of the tumor challenge and immune treatment. (B) Tumor volume of RM-1 tumors in C57BL/6J mice after various treatment strategies. (C) Survival curve of mice suffering RM-1 tumors in different groups. (D) Individual tumor growth kinetics. FCM quantitative analysis of (E,F) CD8+ T cells/CD45+ cells and (G–I) NK cells/CD45+ cells and NKG2D on NK cells from mice suffering RM-1 tumors after different treatment strategies. Data are presented as average ± SD (n = 6 for B, n = 3 for F, H, and I; **p < 0.01, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001).

To investigate the mechanisms underlying various anticancer strategies, FCM was used to detect tumor infiltration by CD8+ T and NK cells. Enhanced infiltration of CD8+ T and NK cells was noted in tumor sites in the vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group. Furthermore, the MFI of NKG2D on NK cells in the SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group and vaccine + SCNP/R837 + anti-PD1 group was higher than the control and SCNP/R837 groups (Figure 6E–I). Early vaccination and anti-PD1 treatment could improve the therapeutic efficacy of SCNP/R837 by mediating early immune system recognition of tumor cells, efficiently bypassing the immunosuppressive tumor environment.33,34

Conclusions

The present study describes the first reported vaccine using POxTA NPs and SCMs. PMBEOx-COOH as a delivery system is effective for loading R837 and CCMs. Meanwhile, applications of SCMs as autologous TAA sources can endow the nanovaccine with individualization for specific patients. The prepared SCNPs/R837 can activate pDCs both in vitro and in vivo, triggering a significant release of inflammation-related cytokines, particularly IFN-α, IL-6, and IL-12. Activated pDCs can recruit and activate NK cells and CTLs at tumor sites, especially NKG2G+ NK cells, effectively bypassing the tumor immunosuppressive microenvironment and killing tumor cells. When combined with an anti-PD1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, SCNPs/R837 as a therapeutic vaccine can induce high-level recruitment and activation of NK cells and CTLs at tumor sites, ultimately inhibiting tumor progression. This personalized nanovaccine offers a target for clinical research as a promising cancer vaccine formulation.

Acknowledgments

This study received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant 81901591 and 51773083); the Key Scientific Project of Jilin Province (YDZJ202201ZYTS088 and YDZJ202201ZYTS098); the China Scholarship Council (CSC); and the Graduate Innovation Fund of Jilin University (grant no. 101832020CX282).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CCM,

cancer cell membrane

- TAA,

tumor-associated antigen

- PMBEOx-COOH,

thioglycolic-acid-grafted poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline)-block-poly(2-butyl-2-oxazoline-co-2-butenyl-2-oxazoline)

- POxTA NP/R837,

R837-loaded PMBEOx-COOH nanoparticle

- SCNP/R837,

surgically derived CCM-coated POxTA NP

- APC,

antigen-presenting cell

- DC,

dendritic cell

- CTL,

cytotoxic T lymphocyte

- NK cell,

natural killer cell

- TCL,

tumor cell lysate

- PLGA,

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- R837,

imiquimod

- CLM,

cell-line-derived CCM

- SCM,

surgically derived CCM

- pDC,

plasmacytoid dendritic cell

- LN,

lymph node

- PD1 antibody,

programmed cell death-1 antibody

- MeOTf,

methyl trifluoromethylsulfonate

- MeOx,

2-methyl-2-oxazoline

- CLNP/R837,

RM-1 prostate cancer cell line-derived CCM-coated POxTA NP

- PBS,

phosphate-buffered saline

- HPLC,

high-performance liquid chromatography

- TEM,

transmission electron microscopy

- BMC,

bone marrow cell

- CO2,

carbon dioxide

- DiD,

tetramethylindodicarbocyanine perchlorate

- FCM,

fluorescence cytometry

- CLSM,

confocal laser scanning microscopy

- DLC,

drug-loading capacity

- DLE,

drug-loading efficiency

- POxTA NP/DiD,

DiD-labeled POxTA NP

- IFN-α,

interferon-α

- IL-6,

interleukin-6

- MFI,

mean fluorescence intensity

- ELISA,

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Treg,

regulatory T cell

- TAM,

tumor-associated macrophage.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsami.2c22363.

1H NMR spectra of BuOx (in CDCl3); 1H NMR spectra of ButenOx (in CDCl3); 1H NMR spectra of PMBEOx (in CDCl3); 1H NMR spectra of PMBEOx-COOH (in CDCl3); release kinetics of R837 from POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 in PBS at pH 7.4 and pH 5.5; diameter changes of POxTA NP/R837, CLNP/R837, and SCNP/R837 in PBS at pH 7.4 and 25 °C with increasing time; secretion of IL-6 and IL-12 in murine serum after subcutaneous administration of the different nanovaccine formulations; representative immunohistochemical images of the tumor infiltration of Tregs, TAMs, NK cells, and CD8+ T cells after different treatments; and body weight of the mice in the different groups of the prophylactic efficacy experiment and therapeutic efficacy experiment (PDF)

Author Contributions

S.L. and J.C. conceived the study; S.L., S.D., and J.W. performed the experiments; N.Y. and J.W. analyzed the data; X.L. and Q.W. contributed to the flow cytometric studies; J.C. and C.W. conceived and designed the experiments and supervised the work. All authors contributed to data analysis, reviewed, and edited the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang Y.; Wang M.; Wu H. X.; Xu R. H. Advancing to the era of cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 803–829. 10.1002/cac2.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T.; Hua C.; Yue W.; Wu J.; Lv X.; Wei Q.; Zhu S.; Zang G.; Cui J.; Liu Y. J.; Chen J. Discrepant antitumor efficacies of three CpG oligodeoxynucleotide classes in monotherapy and co-therapy with PD-1 blockade. Pharmacol. Res. 2020, 161, 105293. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Mercier I.; Poujol D.; Sanlaville A.; Sisirak V.; Gobert M.; Durand I.; Dubois B.; Treilleux I.; Marvel J.; Vlach J.; Blay J.-Y.; Bendriss-Vermare N.; Caux C.; Puisieux I.; Goutagny N. Tumor promotion by intratumoral plasmacytoid dendritic cells is reversed by TLR7 ligand treatment. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 4629–4640. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou Y.; Liu C.; Kim G. J.; Liu Y. J.; Hwu P.; Wang G. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells synergize with myeloid dendritic cells in the induction of antigen-specific antitumor immune responses. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 1534–1541. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demoulin S.; Herfs M.; Delvenne P.; Hubert P. Tumor microenvironment converts plasmacytoid dendritic cells into immunosuppressive/tolerogenic cells: insight into the molecular mechanisms. J. Leukocyte Biol. 2012, 93, 343–352. 10.1189/jlb.0812397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Märkl F.; Huynh D.; Endres S.; Kobold S. Utilizing chemokines in cancer immunotherapy. Trends Cancer 2022, 8, 670–682. 10.1016/j.trecan.2022.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Fu M.; Wang M.; Wan D.; Wei Y.; Wei X. Cancer vaccines as promising immuno-therapeutics: platforms and current progress. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 15, 1–26. 10.1186/s13045-022-01247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.; Xie D.; Yang L. Engineering strategies to enhance oncolytic viruses in cancer immunotherapy. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. 2022, 7, 117. 10.1038/s41392-022-00951-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nam J.; Son S.; Park K. S.; Zou W.; Shea L. D.; Moon J. J. Cancer nanomedicine for combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2019, 4, 398–414. 10.1038/s41578-019-0108-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Chen J. Current status and future directions of cancer immunotherapy. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 1773–1781. 10.7150/jca.24577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R.; Billingsley M. M.; Mitchell M. J. Biomaterials for vaccine-based cancer immunotherapy. J. Control Release 2018, 292, 256–276. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley R. S.; June C. H.; Langer R.; Mitchell M. J. Delivery technologies for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 175–196. 10.1038/s41573-018-0006-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coumes F.; Huang C.-Y.; Huang C.-H.; Coudane J.; Domurado D.; Li S.; Darcos V.; Huang M.-H. Design and development of immunomodulatory antigen delivery systems based on peptide/PEG-PLA conjugate for tuning immunity. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 3666–3673. 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b01150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Guo Z.; Zheng R.; Xie W.; Gao X.; Gao J.; Zhang Y.; Xu W.; Ye J.; Guo X.; Tang J.; Yu J.; Wang L.; Xu B.; Zhang G.; Zhao L. Local destruction of tumors for systemic immunoresponse: Engineering antigen-capturing nanoparticles as stimulus-responsive immunoadjuvants. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 4995–5008. 10.1021/acsami.1c21946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Liu J.; Sun M.; Wang J.; Wang Y.; Sun Y. Cell membrane-camouflaged nanocarriers for cancer diagnostic and therapeutic. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 24. 10.3389/fphar.2020.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll A. V.; Fang R. H.; Jiang Y.; Zhou J.; Wei X.; Yu C. L.; Gao J.; Luk B. T.; Dehaini D.; Gao W.; Zhang L. Nanoparticulate delivery of cancer cell membrane elicits multiantigenic antitumor immunity. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703969. 10.1002/adma.201703969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y.; Krishnan N.; Zhou J.; Chekuri S.; Wei X.; Kroll A. V.; Yu C. L.; Duan Y.; Gao W.; Fang R. H.; Zhang L. Engineered cell-membrane-coated nanoparticles directly present tumor antigens to promote anticancer immunity. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001808. 10.1002/adma.202001808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S.; Feng X.; Wang J.; Xu W.; Islam M. A.; Sun T.; Xie Z.; Wang C.; Ding J.; Chen X. Multiantigenic nanoformulations activate anticancer immunity depending on size. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1903391. 10.1002/adfm.201903391. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye X.; Liang X.; Chen Q.; Miao Q.; Chen X.; Zhang X.; Mei L. Surgical tumor-derived personalized photothermal vaccine formulation for cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 2956–2968. 10.1021/acsnano.8b07371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher T. N.; Schreiber R. D. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 2015, 348, 69–74. 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan S. B.; Taber A. M.; Jileaeva I.; Pegues E. P.; Sentman C. L.; Stephan M. T. Biopolymer implants enhance the efficacy of adoptive T-cell therapy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 97–101. 10.1038/nbt.3104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorson T.; Lübtow M. M.; Wegener E.; Haider M. S.; Borova S.; Nahm D.; Jordan R.; Sokolski-Papkov M.; Kabanov; Kabanov A. V.; Luxenhofer R. Poly(2-oxazoline)s based biomaterials: A comprehensive and critical update. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 204–280. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang D.; Ramsey J. D.; Kabanov A. V. Polymeric micelles for the delivery of poorly soluble drugs: From nanoformulation to clinical approval. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2020, 156, 80–118. 10.1016/j.addr.2020.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S.; Ma S.; Liu Z.-L.; Ma L.-L.; Zhang Y.; Tang Z.-H.; Deng M.-X.; Song W.-T. Functional amphiphilic poly(2-oxazoline) block copolymers as drug carriers: The relationship between structure and drug loading capacity. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 39, 865–873. 10.1007/s10118-021-2547-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Li X.; Li Y.; Zhou Y.; Fan C.; Li W.; Ma S.; Fan Y.; Huang Y.; Li N.; Liu Y. Synthesis, characterization and biocompatibility of poly (2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)–poly (d, l-lactide)–poly (2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) hydrogels. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 4149–4159. 10.1016/j.actbio.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Li S.; Yang Y.; Zhu S.; Zhang M.; Qiao Y.; Liu Y. J.; Chen J. TLR-activated plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibit breast cancer cell growth in vitro and in vivo. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 11708–11718. 10.18632/oncotarget.14315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R.; Xu J.; Xu L.; Sun X.; Chen Q.; Zhao Y.; Peng R.; Liu Z. Cancer cell membrane-coated adjuvant nanoparticles with mannose modification for effective anticancer vaccination. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5121–5129. 10.1021/acsnano.7b09041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang D.; Ramsey J. D.; Makita N.; Sachse C.; Jordan R.; Sokolsky-Papkov M.; Kabanov A. V. Novel poly(2-oxazoline) block copolymer with aromatic heterocyclic side chains as a drug delivery platform. J. Control Release 2019, 307, 261–271. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M.; Liu X.; Bai H.; Lai L.; Chen Q.; Huang G.; Liu B.; Tang G. Surface-layer protein-enhanced immunotherapy based on cell membrane-coated nanoparticles for the effective inhibition of tumor growth and metastasis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 9850–9859. 10.1021/acsami.9b00294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.; Wang J.; Zhu D.; Wang Y.; Qing G.; Zhang Y.; Liu X.; Liang X.-J. Effect of physicochemical properties on in vivo fate of nanoparticle-based cancer immunotherapies. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 886–902. 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habibi N.; Christau S.; Ochyl L. J.; Fan Z.; Hassani Najafabadi A.; Kuehnhammer M.; Zhang M.; Helgeson M.; Klitzing R.; Moon J. J.; Lahann J. Engineered ovalbumin nanoparticles for cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Ther. 2020, 3, 2000100. 10.1002/adtp.202000100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen N.; Wu J.; Yang C.; Yu H.; Yang S.; Li T.; Chen J.; Tang Z.; Chen X. Combretastatin A4 nanoparticles combined with hypoxia-sensitive imiquimod: A new paradigm for the modulation of host immunological responses during cancer treatment. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 8021–8031. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.9b03214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S.; Lv X.; Zhang X.; Li T.; Zang G.; Yang N.; Wang X.; Wu J.; Chen W.; Liu Y. J.; Chen J. An effective dendritic cell-based vaccine containing glioma stem-like cell lysate and CpG adjuvant for an orthotopic mouse model of glioma. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 2867–2879. 10.1002/ijc.32008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Zhao M.; Sun M.; Wu S.; Zhang H.; Dai Y.; Wang D. Multifunctional nanoparticles boost cancer immunotherapy based on modulating the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 50734–50747. 10.1021/acsami.0c14909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.