Abstract

Purpose:

Norm-referenced, standardized measures are tools designed to characterize a child's abilities relative to their same-age peers, but they also have been used to measure changes in skills during intervention. This study compared the psychometric properties of four types of available scores from one commonly used standardized measure, the Preschool Language Scales–Fifth Edition (PLS-5), to detect changes in children's language skills during and after a language intervention.

Method:

This study included data from 110 autistic children aged 18–48 months whose mother participated in an 8-week parent-mediated language intervention. Children's language skills were measured at 3 time points using the PLS-5. Changes in children's expressive and receptive language skills were calculated using raw scores, standard scores, age equivalents, and growth scale values (GSVs).

Results:

Analysis of raw scores, age equivalents, and GSVs indicated significant improvement in the scores of autistic children in both receptive and expressive language throughout the study (i.e., during the intervention period and in the 3-month period after the intervention). Standard scores suggested improvement only in the receptive language scale during the intervention period. Standard scores showed a floor effect for children who scored at −3 SD below the mean.

Conclusions:

Findings suggested that GSVs were not only psychometrically sound but also the most sensitive measure of direct changes in skills compared to raw, standard, and age-equivalent scores. Floor effects may limit the sensitivity of standard scores to detect changes in children's skills. Strengths, limitations, and interpretations of each of the scoring approaches in measuring changes in skills during intervention were discussed.

Supplemental Material:

Norm-referenced, standardized measures are tools commonly used to characterize a child's language abilities and determine a child's eligibility for clinical services. The use of these measures often extends beyond this original intention, to also quantify changes in children's skills during intervention by both researchers (Fuller & Kaiser, 2020; Roberts & Kaiser, 2011) and clinicians (Kerr et al., 2003; McCauley & Swisher, 1984). This extended use of norm-referenced, standardized measures has been critiqued because of the inadequate consideration of the psychometric properties of the scores available in these measures (Daub et al., 2021). That is, norm-referenced standardized measures offer a variety of scores, including raw scores, standard scores, age-equivalent scores, and in some cases, growth scale values (GSVs) that represent an individual's performance on the measure. These available scores differ in their psychometric properties and, therefore, are not equally appropriate or sensitive to detecting changes in skills (Daub et al., 2021; Farmer et al., 2020). The Preschool Language Scales–Fifth Edition (PLS-5), for example, offers different scores to support the different uses of the measure, which include determining a child's level of language delay/disorders, as well as to measure changes in skills over time (Zimmerman et al., 2011).

Raw scores are calculated by summing the performance on all items within a measure or within a subscale of a measure. In the PLS-5, for example, raw scores can be calculated for the auditory comprehension (AC) and the expressive communication (EC) scales independently (Zimmerman et al., 2011). As the PLS-5 was designed to measure children's skills from birth to 7 years 11 months, the items within each subscale capture a broad range of language skills. As children develop more skills, we can expect them to get more items correct and obtain a higher raw score. Although raw scores can sometimes appear on equal intervals (i.e., each item contributes equal points to the raw score), they are in fact ordinal scale variables (Bock, 1997). This means that the difference between two raw scores is not constant across the test—sometimes two successive items may be of very similar difficulty, whereas at other times, the amount of skill needed to succeed at the next item is much larger. Therefore, it is not meaningful to compare changes in raw scores at different levels of this scale or over time (Bock, 1997; Grimby et al., 2012). In order words, to interpret changes in raw scores, one needs to know more information about the items that contributed to the changes in the raw scores (Baylor et al., 2011). In the intervention literature, raw scores have been used to demonstrate treatment-related changes in skills in several ways. For example, studies have compared the changes in raw scores by comparing postintervention scores between groups while controlling for age and raw scores before intervention (Green et al., 2010; Hampton et al., 2020). Within-subject comparisons are sometimes made by subtracting an individual's own preintervention raw score from their postintervention score and testing the extent to which these changes differ from zero (e.g., Gibbard et al., 2004).

Age equivalents are also often available for norm-referenced measures. Age equivalents represent the age at which a given raw score is equal to the median score for that age in the standardization sample. Age equivalents are some of the most misinterpreted scores (Bracken, 1988); contrary to what this term suggests, age equivalents do not represent the equivalent age at which children function. This is because at any given age, there is a range of normal variability in raw scores (Maloney & Larrivee, 2007). Across cohorts of children at different ages, these ranges of normal variability in raw scores overlap. Consequently, assigning age equivalents, which solely reflect the median of the range of normal variation, can give a false impression that a child is functioning above or below their expected chronological age (i.e., when the age equivalents of their raw scores are older or younger than their chronological age). Similar to raw scores, age equivalents are ordinal scale variables that do not exist on an equal interval scale, which makes the magnitude of change in age equivalents (e.g., from before to after intervention) difficult to interpret or compare. In the current intervention literature, age equivalents have been used to compare preintervention and postintervention language skills within subjects (e.g., Siller et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2019). Studies further transform age-equivalent scores using logarithmic transformation (e.g., Siller & Sigman, 2008) or by calculating developmental quotients (i.e., a ratio between age equivalents and chronological age; e.g., Casenhiser et al., 2013) to support the interpretation of changes in age-equivalent scores.

More recently, person-ability scores have become available on several norm-referenced, standardized measures. Multiple names are used for person-ability scores depending on the test, including GSV (e.g., the PLS-5, Zimmerman et al., 2011; Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test‑Fourth Edition, Dunn et al., 2007), change-sensitive scores (e.g., the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales–Fifth Edition; Roid & Pomplun, 2012), and W-scores (e.g., the Woodcock-Johnson Cognitive and Achievement tests; Jaffe, 2009). Person-ability scores are developed based on item response theory (IRT; Snyder & Sheehan, 1992), a class of analytic approaches that estimates a latent, unobservable score based on observable data (see Baylor et al., 2011, for a tutorial about IRT for speech-language pathologists). An IRT model recognizes that an individual's score on each item of a standardized measure (i.e., the observable variable) is influenced by a combination of factors: (a) the individuals' true ability (i.e., the latent variable of interest), (b) the difficulty level of the item, (c) the item's ability to discriminate varying levels of ability (i.e., some items may be better than others at differentiating ability), and (d) guessing (i.e., the probability of a correct response from guessing rather than ability; Snyder & Sheehan, 1992). Therefore, by accounting for these combined factors, IRT provides a way to better estimate an individual's true ability (i.e., the latent variable) based on their performance on the measure (i.e., the observable variable). Similar to raw scores, an individual's response to each item on the measure contributes to the calculation of a person-ability score. In contrast to raw scores, they are on an equal interval scale. The PLS-5 manual gave the following example about one item on the EC subscale: A child who previously babbled but is now beginning to say at least one word may only gain 1 raw score point on the item “uses at least one word”; however, this item contributes to an increase of 10 points on the GSV scale because the use of a first word is a clinically significant milestone of expressive language ability (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Increasingly, person-ability scores are being used to demonstrate changes in children's abilities (Daub et al., 2017; Sadhwani et al., 2021). For children who are more severely delayed (i.e., those who score at the floor of a standardized test), these person-ability scores may more sensitively detect changes in ability (Farmer et al., 2020).

Standard scores are equal interval scale variables. Standard scores represent a child's performance relative to the performance of age-matched peers (i.e., child's age-adjusted standing). The standard score scale on the PLS-5 has a mean of 100 and an SD of 15. Standard scores are useful in estimating whether children's performance is above, at, or below the average of peers at the same age. For example, a standard score of 85 means that the child's performance is 1 SD below the average of their age group. Since standard scores are equal interval variables, from a methodological perspective, these scores are suitable for parametric statistical analysis and common arithmetic operations (e.g., subtracting postintervention scores from those at preintervention) across groups of children with different ability levels. In the current intervention literature, many studies have compared changes in standard scores as an indicator of treatment efficacy. For example, studies have compared each participant's preintervention standard score to their own postintervention standard score to assess within subject change over time (e.g., Bradshaw et al., 2019; Vernon et al., 2019). Other studies compare change in language abilities over time between groups (e.g., Buzhardt et al., 2020; Frazier et al., 2021; Kronenberger et al., 2020; Roberts & Kaiser, 2012, 2015). Although methodologically feasible, the interpretation of changes in standard scores is challenging and can be misleading. That is, changes in a child's standard scores over time do not directly imply improvement or regression in their language skills but rather indicate a change in the child's performance relative to peers of the same age. For example, if a child's below-average standard scores decreased over time (i.e., a negative change in standard scores), this does not necessarily mean that the child has regressed and lost skills, but rather, it suggests that the child's performance is further from the average of their peers, which could happen if the child gained skills but at a slower rate than most peers, experienced no change in their skills, or actually lost the ability (e.g., due to a degenerative condition, Farmer et al., in press).

In summary, standardized measures offer a variety of scores, which have all been used in early intervention literature to track and compare changes in children's language skills. The various scoring methods have different psychometric properties that (a) require different statistical tests and (b) likely impact the extent to which the scores can accurately capture change in children's skills during intervention. Specifically, raw scores and age equivalents are ordinal scale measures that, generally speaking, do not satisfy the level of measurement assumption of parametric statistical tests such as t tests or ANOVA (Miller & Salkind, 2002; Townsend & Ashby, 1984). In contrast, GSVs and standard scores are equal interval scale variables that satisfy the level of measurement assumption in parametric statistical tests. In addition, raw scores, age equivalents, and GSVs directly reflect a child's ability, and therefore, changes in these scores more directly reflect changes in a child's skills. In contrast, standard scores reference a child's ability to a normative sample where changes in standard scores reflect changes in the gap between a child's ability relative to same-age peers (e.g., standard scores only improve when a child gained skills at an accelerated rate, which closed the gap with peers).

The purpose of this study is to (a) compare the ability of these four scoring methods to detect changes in the skills of autistic children in a language intervention, (b) explore which scoring approaches are more prone to floor effects and thus may be less sensitive to change in children of varying language skills (i.e., for preverbal vs. verbal children), and (c) illustrate the strengths, limitations, and appropriate interpretation of children's outcomes using each of these scoring methods. To do so, we will analyze PLS-5 data collected during a parent-mediated language intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs; clinical trial: NCT02632773, clinicaltrials.gov). The purpose of this study was not to determine the effects of intervention (see Roberts et al. 2022, and Jones et al., 2022, for between-groups comparisons of parent and child outcomes, respectively) but rather to examine how different scoring methods of the same measure reflect changes in language skills of autistic children.

Method

Participants

This study involved secondary analysis of an existing clinical trial with 110 mother–child dyads of children between 18 and 48 months diagnosed with ASD. Demographic information is presented in Table 1. Mother–child dyads were recruited through their Illinois Early Intervention providers, pediatricians, and ASD diagnostic clinics in the Chicagoland area. The original study was approved by the IRB (STU00201708) and registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02632773). Mothers provided informed consent prior to participation. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria are provided with the primary study end points (Jones et al., 2022; Roberts et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Baseline participant characteristics.

| Characteristic | All participants

a

|

Participants by intervention group |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 110 | Responsive (n = 55) | Directive (n = 55) | |

| Child's age in months, M (SD) | 33.16 (6.21) | 32.84 (6.28) | 33.47 (6.19) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 83 (75) | 38 (69) | 45 (82) |

| Female | 27 (25) | 17 (31) | 10 (18) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| African American | 12 (11) | 6 (11) | 6 (11) |

| American Indian/Alaskan | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Asian | 3 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) |

| European American | 58 (53) | 26 (47) | 32 (58) |

| Multiple | 27 (25) | 14 (25) | 13 (24) |

| Chose not to report | 8 (7) | 6 (11) | 2 (4) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 39 (35) | 18 (33) | 21 (38) |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 66 (60) | 33 (60) | 33 (60) |

| Chose not to report | 4 (4) | 3 (5) | 1 (2) |

One participant in sample (responsive group) did not report race and ethnicity.

Intervention

Mother–child dyads participated in eight weekly, hour-long coaching intervention sessions with a speech-language pathologist or developmental therapist (a bachelor's level special education provider with training in early intervention, also referred to as special instructor or special educator). Dyads were randomized into two intervention arms to either receive coaching on responsive strategies (n = 55) or directive strategies (n = 55). For both groups, the first session consisted of a workshop to introduce the specific intervention strategies, and each of the seven subsequent weeks followed the standardized teach–model–coach–review instructional format (Roberts et al., 2014). Both responsive and directive strategies are parts of the Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBIs) that effectively support social communication outcomes in children with ASD (Sandbank et al., 2020).

Measures for Language Skills

The PLS-5 (Zimmerman et al., 2011) was administered by trained assessors to all children at three time points during the study: baseline (T0) before the intervention, end of intervention (T1), and 3 months after the end of intervention (T2). The average length of time from T0 to T1 PLS-5 administrations and T1 to T2 PLS-5 administrations were 14.3 weeks (SD = 2.5) and 10.7 weeks (SD = 2.1), respectively. The PLS-5 is a norm-referenced developmental language assessment widely used to evaluate the receptive and expressive language skills of children from birth to 7 years 11 months. Test-retest reliability for the PLS-5 ranges from .89 to .95 for children from birth to 4 years 11 months, demonstrating good to excellent stability in the measure over time. The PLS-5 offers two domains of language scores: AC (i.e., receptive language) and EC (i.e., expressive language). Assessors were clinically certified speech-language pathologists and a trained research assistant who met and maintained over 80% fidelity in PLS-5 administration throughout the study and were blinded to participants' treatment arm. At each time point, the raw scores, standard scores, age equivalents, and GSVs were calculated for the two language domains according to the PLS-5 Examiner Manual (Zimmerman et al., 2011).

Analysis of Changes in Children's Skills

The first aim of this study was to compare the sensitivity of these four PLS-5 scoring methods (raw scores, standard scores, age equivalents, and GSVs) in detecting changes in children's skills during a language intervention. To do so, we explored changes in children's performance during the intervention period (i.e., from T0 to T1) and during the 3-month postintervention period (i.e., from T1 to T2). We calculated the difference scores by subtracting each child's own scores at the previous time point (i.e., T1 minus T0, and T2 minus T1). The use of a difference score is a common way to measure change over time (Castro-Schilo & Grimm, 2018) and is consistent with the PLS-5 manual for the calculation and interpretation of GSVs (Zimmerman et al., 2011). Cohen's d was calculated to illustrate the effect size of change in children's skills. We note that the use of parametric analyses on raw scores and age equivalents, which are ordinal scale variables, violated some assumptions in these statistical analyses. However, using the same analysis across all four scoring approaches can more clearly illustrate the differences between the scoring approaches, which was the main purpose of this analysis. Overall, nonparametric comparisons using Wilcoxon signed-ranks test (see data reporting in Supplemental Material S1) and the parametric analyses produced similar confidence intervals and magnitudes of effect for all scoring approaches. Both parametric and nonparametric analyses showed significant improvement in language skills in EC and AC subscales for raw scores, age equivalents, and GSVs during the intervention and in the 3-month postintervention period. However, standard scores did not consistently demonstrate improvement across time points or PLS-5 subscales.

As this clinical trial had two treatment arms (directive strategies and responsive strategies), we first explored whether there was a difference in the changes in participants' skills between the two treatment groups. This analysis revealed that, regardless of the scoring approach used, participants in the two treatment groups had similar changes in skills on the PLS-5 AC and EC subscales (i.e., the effect sizes of the two intervention arms, regardless of scoring approaches or PLS-5 subscales, did not significantly differ, p ≥ .099). In all subsequent analyses, we have combined data from both treatment groups because the main goal of this study was to illustrate the impact of choosing different scoring approaches on detecting changes in children's skills rather than to compare the effectiveness of the two treatments. We further note that the changes in participants' scores in this study may be due to a range of factors including natural development and intervention effect. With the current study design (e.g., without a no-treatment control group), it was not appropriate to infer or differentiate the factors underlying score changes.

The second aim of this study was to explore which scoring approaches were more prone to floor effects and which may be less sensitive to change in children of varying language skills (i.e., for preverbal vs. verbal children). To do so, we explored the distribution of children's ability at baseline as measured by each of the scoring approaches. To help visualize the floor effect, we plotted the distribution of children's raw scores, standard scores, and age equivalents against their corresponding GSVs. We also calculated the correlation between these scores.

To test whether different scoring approaches may more sensitively detect changes in skills for children who were preverbal versus verbal at baseline, we fitted multilevel models to explore the effect of children's spoken language status (i.e., verbal and preverbal) on their rate of language changes across the three intervention time points. This analysis was only conducted on standard scores and GSVs, which satisfy the interval scale variables' assumptions for a regression analysis. In addition to the distributional assumption for the outcomes, these models also make statistical assumptions regarding the independence of residuals after accounting for the within-person variance and the normal distribution of the random effects. As part of our analyses, we evaluated whether standard scores or GSVs violated any of these other assumptions. We visually inspected the distribution of residuals to ensure there was not a significant violation of distribution assumptions for parametric analyses. The only noteworthy violation was the distribution of standard scores from the PLS-5 AC scale, which presented with minor skewness due to floor effects. Multilevel models are particularly useful in understanding nested data (Siller & Sigman, 2008; Yarger et al., 2016), such as in our case, to understand each participant's growth trajectory over time (i.e., within-subject effects), when their data were simultaneously used to explore whether verbal versus preverbal participants had different trajectories (i.e., between-subjects effects). Children's spoken language status was measured at baseline using an item on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012). Specifically, children were considered verbal if they (a) regularly used utterances with two or more words, (b) occasionally used phrases but spoke mostly single words, or (c) spoke five different meaningful and recognizable single words. Children were considered preverbal if they (a) had at least one but fewer than five words/word approximations or (b) had no spontaneous use of word/word approximations. The multilevel models were constructed with the lme4 package in R using a restricted maximum likelihood approach (Bates et al., 2015). The model estimated each participant's language score predicted by (a) each participant's own average language score (i.e., within-subject random-intercept effects), along with (b) the assessment time points (i.e., baseline, postintervention, and follow-up), (c) the verbal and preverbal grouping variable, and (d) the interaction effect between assessment time points and verbal and preverbal groups, reflecting the difference in slope across the two groups. To estimate fixed effects, estimates, t values, and confidence intervals were calculated. In addition, p values and effect sizes of the trajectory of changes in scores between the verbal and preverbal groups were estimated using the emmeans package in R.

Results

Changes in Skills Measured by the Different Scores

When measuring changes children made during the intervention (i.e., from T0 to T1), raw scores, age equivalents, and GSVs indicated a statistically significant improvement in children's PLS-5 AC and EC scores (p ≤ .001). The magnitude of the Cohen's d effect size ranged from .57 to .74, suggesting a moderate effect. Standard scores, however, showed that children made significant gain in AC (p = .02) but not EC scores (p = .48). The magnitude of the effect size in receptive language was .23, suggesting a small effect. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Effect size of changes from the intervention as measured by each scoring approach.

| PLS-5 AC |

PLS-5 EC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Changes during the intervention (T1 minus T0 scores) |

|||||||

| RS | AE | GSV | SS | RS | AE | GSV | SS | |

| M | 2.04 | 2.41 | 13.81 | 1.9 | 1.52 | 1.75 | 10.53 | 0.47 |

| d | 0.72 | 0.7 | 0.74 | 0.23 | 0.63 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.07 |

| 95% CI | [.49, .95] | [.48, .92] | [.51, .96] | [.03, .44] | [.41, .85] | [.36, .79] | [.43, .87] | [−.13, .27] |

|

p

|

< .001**

|

< .001**

|

< .001**

|

.02*

|

< .001**

|

< .001**

|

< .001**

|

.48 |

|

Changes during the 3-month postintervention period (T2 minus T1 scores)

| ||||||||

| M | 2.04 | 2.39 | 11.82 | 1.25 | 1.02 | 1.48 | 6.92 | −1.44 |

| d | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.13 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 | −0.2 |

| 95% CI | [.31, .77] | [.31, .77] | [.30, .75] | [−.09, .34] | [.24, .69] | [.25, .70] | [.24, .69] | [−.42, .02] |

| p | < .001** | < .001** | < .001** | .25 | < .001** | < .001** | < .001** | .07 |

Note. PLS-5 = Preschool Language Scales–Fifth Edition; AC = auditory comprehension scale; EC = expressive communication scale; RS = raw score; AE = age equivalents; GSV = growth scale values; SS = standard scores; CI = confidence intervals.

p < .05.

p < .001.

When measuring changes children made during the 3-month period after the intervention (i.e., from T1 to T2), raw scores, age equivalents, and GSVs yielded a significant and moderate improvement in children's receptive and expressive scores. Standard scores, on the other hand, failed to yield a significant change in children's PLS-5 AC and EC scores (p = .25 and p = .07, respectively). Although it was not significant, it is noteworthy that the direction of the mean effect size for standard scores on the EC scale was negative (indicating a decrease in standard scores over time), unlike all of the other scoring approaches.

Floor Effect

To explore floor effects of the four scoring approaches, we created scatter plots to visualize participants' receptive and expressive language scores at baseline. Figure 1 shows the scatter plots of participants' raw scores (top panel), age-equivalent scores (middle panel), and standard scores (bottom panel) plotted against their GSV scores. Overall, raw scores and age-equivalent scores were highly correlated with GSVs. Standard scores and GSVs were also positively correlated, although more dispersion of scores can be seen in these scatter plots. Furthermore, a floor effect can be observed in participants' standard scores on the PLS-5 AC scale, where many participants had a standard score of 50, equivalent to roughly −3.3 SD below the mean. These same participants' abilities were better differentiated with GSV scores, where participants' scores were distributed in a wider range (range: 252–345).

Figure 1.

Distribution of participants' Preschool Language Scales–Fifth Edition (PLS-5) auditory comprehension (AC) and expressive communication (EC) scores at baseline. GSV = growth scale value.

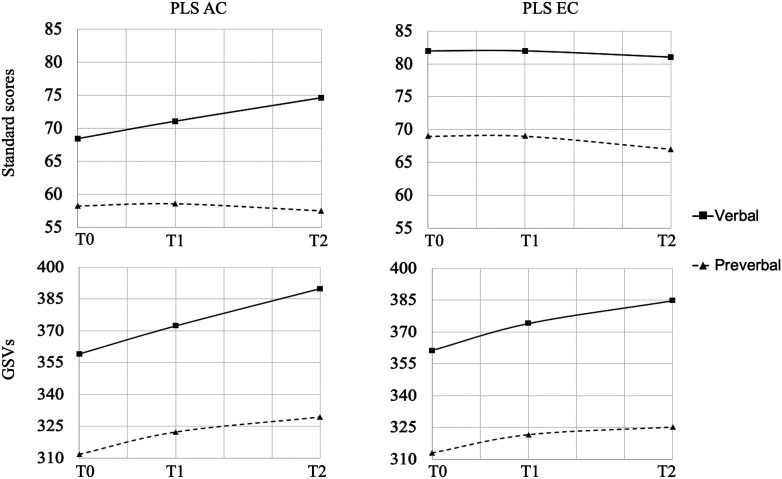

To explore whether standard scores or GSVs may more sensitively detect changes in skills for children who were preverbal versus verbal, we additionally ran multilevel models to explore the random (i.e., within-subject) and fixed (i.e., assessment time point and between verbal and preverbal groups) effects on participants' language scores throughout the intervention study. Of note, the PLS-5 AC standard score had nonnormally distributed residuals, likely due to the floor effect noted above. For standard scores, the ICC values for the PLS-5 AC and EC scales were .79 and .80, respectively. For GSVs, the respective ICC values were .76 and .77. These high ICC values suggest that a lot of the variance in the model was explained by within-participant variabilities. Fixed effects estimates are summarized in Table 3. For standard scores, the simple slopes were not significantly different than 0 for either group on the PLS-5 EC scale, and they were not significantly different than 0 for the preverbal group on the PLS-5 AC scale, suggesting no change in these scores during or after intervention (see Figure 2). The verbal group was estimated to increase 2.7 (95% CI [1.6, 3.9]) standard score points on the AC scale during each 8-week period. This is juxtaposed with the GSV simple slopes (see Figure 2), where both preverbal and verbal groups experienced statistically significant improvement during the study, with the verbal group's improvement outpacing the preverbal group in both EC (p = .03) and AC (p < .01).

Table 3.

Parameter estimates from multilevel models.

| PLS AC |

PLS EC |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Standard scores, fixed effects variables |

|||||||

| Estimate | Standard error | t | 95% CI | Estimate | Standard error | t | 95% CI | |

| Intercept | 58.24 | 1.69 | 34.45* | [54.9, 61.5] | 69.02 | 1.37 | 50.43* | [66.34, 71.69] |

| Time point | −0.43 | 0.53 | −0.82 | [−1.46, 0.60] | −0.66 | 0.41 | −1.60 | [−1.47, 0.15] |

| Verbal status | 10.15 | 2.56 | 3.96* | [5.14, 15.16] | 12.57 | 2.07 | 6.06* | [8.51, 16.63] |

| Time point × verbal status |

3.17 |

0.77 |

4.12*

|

[1.66, 4.68] |

0.53 |

0.60 |

0.88 |

[−0.65, 1.71] |

|

Growth scale values, fixed effects variables

| ||||||||

| Intercept | 313.8 | 3.97 | 79.06* | [306.0, 321.6] | 314.8 | 3.26 | 96.5* | [308.4, 321.2] |

| Time point | 7.08 | 1.30 | 5.45* | [4.53, 9.62] | 5.31 | 1.04 | 5.10* | [3.27, 7.35] |

| Verbal status | 45.13 | 6.01 | 7.51* | [33.4, 56.9] | 46.8 | 4.94 | 9.47* | [37.1, 56.4] |

| Time point × verbal status | 5.50 | 1.90 | 2.89* | [1.77, 9.23] | 3.45 | 1.53 | 2.26* | [0.46, 6.45] |

Note. PLS = Preschool Language Scales; AC = auditory comprehension scale; EC = expressive communication scale; CI = confidence interval.

p < .05, using Kenward‑Roger approximation.

Figure 2.

Changes in language scores for verbal and preverbal groups of participants. AC = auditory comprehension; EC = expressive communication; GSVs = growth scale values; PLS = Preschool Language Scales.

Discussion

This study aimed to use PLS-5 data collected during a randomized controlled trial to illustrate the differences in the psychometric properties of various scores available in norm-referenced, standardized measures. We compared changes in language skills of autistic children as measured by PLS-5 raw scores, standard scores, age equivalents, and person-ability scores (referred to as GSVs on the PLS-5), as these scores have been commonly used in the intervention research literature, and sometimes in clinical practice, to document treatment-related changes.

Findings from this study illustrated that different scoring approaches offered by norm-referenced, standardized measures result in different conclusions about changes in children's skills from an intervention. Specifically, we found that the GSVs, age equivalents, and raw scores demonstrated moderate improvement in children's scores across both AC and EC scales throughout the study (i.e., during the intervention period and in the 3-months period after the intervention). In contrast, findings from the parametric analyses of standard scores indicated that children significantly improved only in the AC scale during the intervention period. All four scoring approaches explored in this study have been used by intervention studies to indicate changes in skills over time. Our findings revealed that the different scoring approaches can yield different treatment effect sizes. Therefore, the choice of scoring approach may have contributed to the inconsistent conclusion about treatment effects in the current language intervention literature (see the reviews by Fuller & Kaiser, 2020; Roberts & Kaiser, 2011; Sandbank et al., 2020). Therefore, it is important for future work to carefully consider the most appropriate scoring approach based on the specific clinical or research questions. The following sections of the discussion will support the selection of the most appropriate scoring approach by (a) illustrating the interpretation of children's outcomes based on each scoring method and (b) discussing the floor effects of these scoring approaches.

As mentioned in the introduction, raw scores and age equivalents are not interval scale variables and thus are not suitable, statistically speaking, for parametric analyses. In addition, without considering the specific items that resulted in changes in children's raw scores or age-equivalent scores over time, it is not possible to conclude how much children's skills have changed from an intervention. In contrast, standard scores and GSVs are both interval scale variables and have the psychometric properties to support meaningful comparisons.

Based on the significant changes in participants' raw scores and age-equivalent scores across different time points of this intervention study, an appropriate interpretation is that there is a statistical difference between pretreatment and posttreatment participants' raw scores (i.e., the number of items correct) and age equivalents scores (i.e., the age at which the participant's raw scores aligned with the median in the distribution). In general, the value of participants' raw scores and age-equivalent scores increased during the intervention and the 3-month period after the intervention. As mentioned above, raw scores are ordinal scale variables and should be analyzed using nonparametric tests. It is also difficult to interpret changes in raw scores without knowing more information about the items that contributed to such changes. Given that GSVs are derived from raw scores, there is a significant correlation between the two scores. In cases when a standardized measure does not provide person-ability scores (e.g., GSVs), the analysis of changes in raw scores using nonparametric tests (e.g., Poisson regression model) can be an alternative approach to detecting changes in ability. Age equivalents (which are also ordinarily scaled) are unreliable estimates of children's ability and can result in drastically different conclusions about changes in children's language skills compared to other scoring approaches (Bracken, 1988; Maloney & Larrivee, 2007). In this study, the effect sizes concluded from analyzing age equivalents happened to be comparable to those of GSV, which may not be the case in other studies with different populations. The advantage of age equivalents is that clinicians find it easier to explain their interpretation to parents or clients (Kerr et al., 2003)—though we note that this apparent ease of interpretation may be misguided, as age equivalents in particular are frequently misinterpreted (Bracken, 1988). Due to the psychometric limitations we discussed, age equivalents were not considered an appropriate approach for evaluating changes in children's skills over time.

Using standard scores, we can conclude that children in this intervention study significantly increased in the PLS-5 AC scale's standard scores only and during the intervention period alone. As all children scored below average on the PLS-5 at the beginning of the intervention, this would suggest that the gap between their performance and the average performance of their same-age peers narrowed (i.e., children scored closer to the mean of their age group). Standard scores on the PLS-5 EC scale suggest that there were no significant changes in children's age-adjusted standing during or after the intervention, but this does not mean that children did not gain expressive language skills in this period. Interestingly, although not significant (p = .07), there was a negative change in standard scores during the 3-month period after the intervention (M = −1.44). This meant that, for some children, their standard scores decreased from T1 (i.e., immediately after intervention) to T2 (i.e., at 3-month follow-up). However, this decrease in standard scores is misleading and may be mistakenly interpreted as regression in children's skills. The more appropriate interpretation of a significant negative change in standard scores, which was not the case in this study, is that the gap between children's language performance and the average performance of their same-age peers has widened (i.e., children scored further from the mean of their age group). Unfortunately, the reason for such a score pattern cannot be determined from the standard score alone—a child may have increased in skills but at a slower rate than same-age peers, they may have plateaued and only maintained their initial skill level, or they may have actually decreased in ability. All three types of changes in ability would result in a similar decrease in age-based standard scores. It is also important to note that standard scores were not intended to be used to measure changes over time. Therefore, when used for this extended purpose, such an interpretation will need careful consideration as we illustrated using data from an intervention study.

In contrast to the findings from standard scores, GSVs—which quantify a person's ability level—indicated that children in this intervention study significantly improved their receptive and expressive language skills during all phases of the intervention (Zimmerman et al., 2011). It may seem odd to see that even though a child was gaining skills (per increases in GSV), it is not reflected in their standard scores. This is a known limitation of standard scores that is acknowledged in the PLS-5 manual (Zimmerman et al., 2011). One reason is that standard scores compare a child's ability to those of their same-age peers, whereas the GSVs measure a child's ability without referencing the normative sample. Therefore, changes in GSVs provide a more direct index of changes in a child's ability estimates (i.e., offering a more “absolute” index of a child's ability), whereas changes in standard scores index changes in a child's ability relative to the reference group of same-age peers (i.e., offering a “relative” index of a child's ability). Another reason is that, for children who have moderate or severe disability, standard scores may have limited sensitivity to detect differences in skill levels.

From the scatter plots (see Figure 1), it can be observed that standard scores were most prone to floor effects and did not differentiate the abilities of participants who scored below −3 SD from the mean. Meanwhile, GSVs offered more variability for differentiating those participants' skills. This floor effect of standard scores may explain why GSVs yielded a significant change in participants' scores at all phases of the intervention but standard scores did not. For a child with a score on the floor of the test, where standard scores do not differentiate small differences in skills, a child would have to increase in ability sufficiently to get off of the floor and obtain a different standard score; otherwise, the increase in ability (appropriately captured on the GSV) would result in no change to the floored standard score.

To further explore this floor effect, we conducted multilevel modeling to determine whether participants' verbal status at baseline (i.e., verbal vs. preverbal) affected the changes measured by standard scores or GSVs throughout the course of the study. Since standard scores were more prone to floor effects, it is possible that they would be less sensitive to changes in children who were preverbal compared to those who were verbal. In contrast, GSVs may be more sensitive to changes in skills for all children, regardless of their verbal status. Our findings suggest that this may have been the case in our sample. Specifically, GSVs found significant improvement for both groups in both language scales during and after intervention, with significantly better improvement for verbal children, whereas standard scores only found significant improvement for verbal children on AC scales. These findings suggest that GSVs were more sensitive not only to detect changes over time but also to detect the different rate of changes in children with varying language ability.

This study recruited a sample of autistic children and measured language skills using the PLS-5. Admittedly, the sample in this study did not represent all developmental populations or standardized language measures clinicians encounter in their real-world practices. Of note, atypical and inconsistent language development trajectories have been reported in autistic children, including regression in language skills (Baird et al., 2008; Lord et al., 2004; Rogers, 2004). Another consideration is whether language-impaired populations were included in the normative sample of the standardized measure. Peña et al. (2006) argued that including language-impaired individuals in the normative sample, as in the case of the PLS-5, can reduce the accuracy of a test in identifying children with language impairments. It is, therefore, possible that the sensitivity of different scoring approaches varies in other developmental populations and in other standardized language measures, which can only be fully addressed in future studies. It is also important to emphasize that this study aimed to compare scoring approaches for tracking changes in skills over time. We caution against drawing any inferences to the potential causes underlying these changes in scores. In this study, changes in participants' scores may be a result of many factors (e.g., natural development, intervention effects, random errors) to which this study was not designed to differentiate or infer. Another future direction for this work is the consideration of the concurrent validity of change scores measured by the PLS-5 compared to other measures, such as criterion measures clinicians use to track progress or parents' report of their child's progress.

In summary, this article illustrated and discussed the psychometric properties and the meaning of different scores available from a commonly used, norm-referenced, standardized measure of language skills. As many have argued, these scoring approaches are not inherently appropriate for all clinical and research purposes. Therefore, the selection of scores should be driven by the specific question being addressed using the scoring approach (Daub et al., 2021). This article provided an in-depth discussion of the appropriateness and sensitivity of four scoring approaches for one purpose: measuring changes in skills of autistic children. Findings suggest that raw scores and age-equivalent scores, though offering large variance, are not suitable psychometrically to detect changes in skills. Standard scores are psychometrically useful for comparing changes, but the interpretation of such change scores should be considered and explained more carefully in research studies and, more importantly, in clinical practice. Floor effects may also limit the sensitivity of standard scores to detect changes in children with severe language delays. Growth scale values, in contrast to raw scores and age equivalents scores, are equal-interval scale variables. Additionally, in contrast to standard scores, GSVs linearly relate to a child's skill level without referencing the performances of same-age peers and are less prone to floor effects. Therefore, GSVs offer the most sensitive measure of direct change in language skills.

Data Availability Statement

Data contributing to the findings of this study are available by the authors upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant 1R01DC014709 (PI: Megan Y. Roberts).

Funding Statement

This study was funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant 1R01DC014709 (PI: Megan Y. Roberts).

References

- Baird, G. , Charman, T. , Pickles, A. , Chandler, S. , Loucas, T. , Meldrum, D. , Carcani-Rathwell, I. , Serkana, D. , & Simonoff, E. (2008). Regression, developmental trajectory and associated problems in disorders in the autism spectrum: The SNAP study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(10), 1827–1836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0571-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D. , Mächler, M. , Bolker, B. , & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [Google Scholar]

- Baylor, C. , Hula, W. , Donovan, N. J. , Doyle, P. J. , Kendall, D. , & Yorkston, K. (2011). An introduction to item response theory and Rasch models for speech-language pathologists. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0079) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bock, D. (1997). A brief history of item theory. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 16(4), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1997.tb00605.x [Google Scholar]

- Bracken, B. A. (1988). Ten psychometric reasons why similar tests produce dissimilar results. Journal of School Psychology, 26(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-4405(88)90017-9 [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, J. , Shic, F. , Holden, A. N. , Horowitz, E. J. , Barrett, A. C. , German, T. C. , & Vernon, T. W. (2019). The use of eye tracking as a biomarker of treatment outcome in a pilot randomized clinical trial for young children with autism. Autism Research, 12(5), 779–793. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.2093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzhardt, J. , Greenwood, C. R. , Jia, F. , Walker, D. , Schneider, N. , Larson, A. L. , Valdovinos, M. , & McConnell, S. R. (2020). Technology to guide data-driven intervention decisions: Effects on language growth of young children at risk for language delay. Exceptional Children, 87(1), 74–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402920938003 [Google Scholar]

- Casenhiser, D. M. , Shanker, S. G. , & Stieben, J. (2013). Learning through interaction in children with autism: Preliminary data from asocial-communication-based intervention. Autism, 17(2), 220–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311422052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Schilo, L. , & Grimm, K. J. (2018). Using residualized change versus difference scores for longitudinal research. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 35(1), 32–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407517718387 [Google Scholar]

- Daub, O. , Bagatto, M. P. , Johnson, A. M. , & Cardy, J. O. (2017). Language outcomes in children who are deaf and hard of hearing: The role of language ability before hearing aid intervention. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 60(11), 3310–3320. https://doi.org/10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-16-0222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daub, O. , Cunningham, B. J. , Bagatto, M. P. , Johnson, A. M. , Kwok, E. Y. , Smyth, R. E. , & Cardy, J. O. (2021). Adopting a conceptual validity framework for testing in speech-language pathology. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(4), 1894–1908. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-20-00032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, L. , Dunn, D. , Lenhard, A. , Lenhard, W. , & Suggate, S. (2007). Core systems of number. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 8(7), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, C. A. , Kaat, A. J. , Thurm, A. , Anselm, I. , Akshoomoff, N. , Bennett, A. , Berry, L. , Bruchey, A. , Barshop, B. A. , Berry-Kravis, E. , Bianconi, S. , Cecil, K. M. , Davis, R. J. , Ficicioglu, C. , Porter, F. D. , Wainer, A. , Goin-Kochel, R. P. , Leonczyk, C. , Guthrie, W. , … Miller, J. S. (2020). Person ability scores as an alternative to norm-referenced scores as outcome measures in studies of neurodevelopmental disorders. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 125(6), 475–480. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-125.6.475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, T. W. , Klingemier, E. W. , Anderson, C. J. , Gengoux, G. W. , Youngstrom, E. A. , & Hardan, A. Y. (2021). A longitudinal study of language trajectories and treatment outcomes of early intensive behavioral intervention for autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(12), 4534–4550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-04900-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, E. A. , & Kaiser, A. P. (2020). The effects of early intervention on social communication outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(5), 1683–1700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03927-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbard, D. , Coglan, L. , & MacDonald, J. (2004). Cost-effectiveness analysis of current practice and parent intervention for children under 3 years presenting with expressive language delay. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 39(2), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/13682820310001618839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, J. , Charman, T. , McConachie, H. , Aldred, C. , Slonims, V. , Howlin, P. , Le Couteur, A. , Leadbitter, K. , Hudry, K. , Byford, S. , Barrett, B. , Temple, K. , Macdonald, W. , Pickles, A. , & PACT Consortium. (2010). Parent-mediated communication-focused treatment in children with autism (PACT): A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 375(9732), 2152–2160. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60587-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimby, G. , Tennant, A. , & Tesio, L. (2012). The use of raw scores from ordinal scales: Time to end malpractice? Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 44(2), 97–98. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, L. H. , Kaiser, A. P. , & Fuller, E. A. (2020). Multi-component communication intervention for children with autism: A randomized controlled trial. Autism, 24(8), 2104–2116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361320934558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, L. E. (2009). Development, interpretation, and application of the W score and the relative proficiency index. Woodcock-Johnson III Assessment Service Bulletin No. 11. Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. , Sone, B. J. , Grauzer, J. , Sudec, L. , Kaat, A. , & Roberts, M. Y. (2022). Active ingredients of caregiver-mediated Naturalistic Developmental Behavioral Interventions (NDBIs) for autistic toddlers: A randomized clinical trial [Manuscript submitted for publication] . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, M. A. , Guildford, S. , & Bird, E. K. R. (2003). Standardized language test use: A Canadian survey utilisation. Journal of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, 27(1), 10–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberger, W. G. , Xu, H. , & Pisoni, D. B. (2020). Longitudinal development of executive functioning and spoken language skills in preschool-aged children with cochlear implants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 63(4), 1128–1147. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-19-00247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C. , Risi, S. , & Pickles, A. (2004). Trajectory of language development in autistic spectrum disorders. In Developmental language disorders (pp. 18–41). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410610881-7 [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C. , Rutter, M. , Dilavore, P. C. , Risi, S. , Gotham, K. , & Bishop, S. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule–Second Edition (2nd ed.). Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, E. S. , & Larrivee, L. S. (2007). Limitations of age-equivalent scores in reporting the results of norm-referenced tests. Contemporary Issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 34(Fall), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1044/cicsd_34_F_86 [Google Scholar]

- McCauley, R. J. , & Swisher, L. (1984). Use and misuse of norm-referenced test in clinical assessment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 49(4), 338–348. https://doi.org/10.1044/jshd.4904.338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. , & Salkind, N. (2002). Handbook of research design & social measurement . SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984386 [Google Scholar]

- Peña, E. D. , Spaulding, T. J. , & Plante, E. (2006). The composition of normative groups and diagnostic decision making: Shooting ourselves in the foot. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(3), 247–254. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2006/023) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. Y. , & Kaiser, A. P. (2011). The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 180–199. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. Y. , & Kaiser, A. P. (2012). Assessing the effects of a parent-implemented language intervention for children with language impairments using empirical benchmarks: A pilot study. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(6), 1655–1670. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0236) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. Y. , & Kaiser, A. P. (2015). Early intervention for toddlers with language delays: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 135(4), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. Y. , Kaiser, A. P. , Wolfe, C. E. , Bryant, J. D. , & Spidalieri, A. M. (2014). Effects of the teach–model–coach–review instructional approach on caregiver use of language support strategies and children's expressive language skills. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(5), 1851–1869. https://doi.org/10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-13-0113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, M. Y. , Sone, B. J. , Jones, M. , Grauzer, J. , Sudec, L. , Stern, Y. S. , Kwok, E. , Losh, M. , & Kaat, A. (2022). One size does not fit all for parent-mediated autism interventions: A randomized clinical trial. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613221102736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S. J. (2004). Developmental regression in autism spectrum disorders. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 10(2), 139–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid, G. H. , & Pomplun, M. (2012). The Stanford-Binet intelligence scales, fifth edition. In Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (3rd ed., pp. 249–268). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Sadhwani, A. , Wheeler, A. , Gwaltney, A. , Peters, S. U. , Barbieri-Welge, R. L. , Horowitz, L. T. , Noll, L. M. , Hundley, R. J. , Bird, L. M. , & Tan, W.-H. (2021). Developmental skills of individuals with Angelman syndrome assessed using the Bayley-III. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04861-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandbank, M. , Bottema-Beutel, K. , Crowley, S. , Cassidy, M. , Dunham, K. , Feldman, J. I. , Crank, J. , Albarran, S. A. , Raj, S. , Mahbub, P. , & Woynaroski, T. G. (2020). Project AIM: Autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychological Bulletin, 146(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller, M. , Hutman, T. , & Sigman, M. (2013). A parent-mediated intervention to increase responsive parental behaviors and child communication in children with ASD: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(3), 540–555. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1584-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller, M. , & Sigman, M. (2008). Modeling longitudinal change in the language abilities of children with autism: Parent behaviors and child characteristics as predictors of change. Developmental Psychology, 44(6), 1691–1704. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, S. , & Sheehan, R. (1992). The Rasch measurement model: An introduction. Journal of Early Intervention, 16(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/105381519201600108 [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, J. T. , & Ashby, F. G. (1984). Measurement scales and statistics: The misconception misconceived. Psychological Bulletin, 96(2), 394–401. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.96.2.394 [Google Scholar]

- Vernon, T. W. , Holden, A. N. , Barrett, A. C. , Bradshaw, J. , Ko, J. A. , McGarry, E. S. , Horowitz, E. J. , Tagavi, D. M. , & German, T. C. (2019). A pilot randomized clinical trial of an enhanced pivotal response treatment approach for young children with autism: The PRISM model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2358–2373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03909-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarger, H. A. , Hoye, J. R. , & Dozier, M. (2016). Trajectories of change in attachment and biobehavioral catch-up among high-risk mothers: A randomized clinical trial. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(5), 525–536. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, V. , Munson, J. A. , Greenson, J. , Hou, Y. , Rogers, S. , & Estes, A. M. (2019). An exploratory longitudinal study of social and language outcomes in children with autism in bilingual home environments. Autism, 23(2), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317743251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, I. L. , Steiner, V. G. , & Pond, R. E. (2011). Preschool Language Scales–5th Edition (PLS-5). Pearson. https://doi.org/10.1037/t15141-000 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data contributing to the findings of this study are available by the authors upon request.