Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated adaption of a telehealth care model. We studied the impact of telehealth on the management of atrial fibrillation (AF) by electrophysiology providers in a large, multisite clinic. Clinical outcomes, quality metrics, and indicators of clinical activity for patients with AF during the 10-week period of March 22, 2020 to May 30, 2020 were compared with those from the 10-week period of March 24, 2019 to June 1, 2019. There were 1946 unique patient visits for AF (1,040 in 2020 and 906 in 2019). During 120 days after each encounter, there was no difference in hospital admissions (11.7% vs 13.5%, p = 0.25) or emergency department visits (10.4% vs 12.5%, p = 0.15) in 2020 compared with 2019. There was a total of 31 deaths within 120 days, with similar rates in 2020 and 2019 (1.8% vs 1.3%, p = 0.38). There was no significant difference in quality metrics. The following clinical activities occurred less frequently in 2020 than in 2019: offering escalation of rhythm control (16.3% vs 23.3%, p <0.001), ambulatory monitoring (29.7% vs 51.7%, p <0.001), and electrocardiogram review for patients on antiarrhythmic drug therapy (22.1% vs 90.2%, p <0.001). Discussions about risk factor modification were more frequent in 2020 compared with 2019 (87.9% vs 74.8%, p <0.001). In conclusion, the use of telehealth in the outpatient management of AF was associated with similar clinical outcomes and quality metrics but differences in clinical activity compared with traditional ambulatory encounters. Longer-term outcomes warrant further investigation.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to paradigm shifts in traditional healthcare delivery models. Healthcare systems focused on decreasing reliance on in-person services to minimize patients’ risks, reduce personnel exposure, preserve personal protective equipment, and avert potential volume surges in emergency departments (EDs) and hospitals.1 Due to regulatory changes, expanded reimbursement, and endorsement by professional societies,2 telemedicine quickly emerged as an essential alternative healthcare delivery model during the pandemic. Telemedicine has been studied in the primary care setting,3 and specialty care settings, such as diabetes mellitus4 and heart failure.5 It remains unknown how the use of telehealth may impact other cardiovascular patient populations, such as those with atrial fibrillation (AF). Patients with AF represent a high-risk population frequently burdened with co-morbidities and may be vulnerable in the setting of predominantly virtual clinical encounters.2 Several medical societies including the American Heart Association and European Heart Rhythm Association recommend following quality metrics in the inpatient and outpatient settings to help healthcare providers improve the quality of care provided to patients with AF and to reduce adverse outcomes related to AF.6 , 7 Whether ambulatory care delivered for AF through virtual encounters results in similar outcomes and quality of care is unknown. To this end, we sought to leverage the “natural experiment” of the COVID-19 pandemic to evaluate the quality of care and clinical outcomes associated with virtual visits as compared with in-person ambulatory visits for patients with AF.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective matched cohort study of patients who had formal ambulatory encounters in the Saint Luke's Health System cardiology clinics, based in Kansas City, Missouri, with electrophysiology providers (6 physicians and 4 nurse practitioners) during the 10-week period of March 22, 2020 to May 30, 2020 compared with those with encounters during the 10-week period of March 24, 2019 to June 1, 2019. Outpatient encounter characteristics, demographics, co-morbidities, and outcomes were extracted from the electronic medical record (Epic, Madison, Wisconsin) for patients with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes of primary or secondary AF diagnoses in their problem list at the outpatient encounter (Table 1 ). Further data were obtained through chart review. The study was approved by our institutional review board and written informed consent was waived.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (n=1,946) | 2019 (n=906) | 2020 (n=1,040) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit type | <0.001 | |||

| In-person | 948 (48.7) | 906 (100) | 42 (4) | |

| Virtual | 998 (51.3) | NA | 998 (96) | |

| Age | 71 [63, 78] | 71 [62, 78] | 71 [64, 77] | 0.278 |

| Female | 808 (41.5) | 355 (39.2) | 453 (43.6) | 0.050 |

| Race | 0.164 | |||

| White | 1,846 (94.9) | 866 (95.6) | 980 (94.2) | |

| Black | 67 (3.4) | 24 (2.6) | 43 (4.1) | |

| Asian | 10 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 5 (0.5) | |

| Native American | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Other | 13 (0.7) | 9 (1) | 4 (0.4) | |

| Patient refused | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | |

| Unknown | 4 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.178 | |||

| Paroxysmal | 1,171 (60.2) | 549 (60.6) | 622 (59.8) | |

| Persistent | 359 (18.4) | 178 (19.6) | 181 (17.4) | |

| Unspecified | 416 (21.4) | 179 (19.8) | 237 (22.8) | |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score | 3 [2, 4] | 3 [2, 4] | 3 [2, 4] | 0.399 |

| Prior pacemaker | 452 (23.2) | 210 (23.2) | 242 (23.3) | 0.962 |

| Prior ICD | 261 (13.4) | 121 (13.4) | 140 (13.5) | 0.945 |

| Prior CRT device | 37 (1.9) | 14 (1.5) | 23 (2.2) | 0.283 |

| Prior ablation | 1,037 (53.3) | 459 (50.7) | 578 (55.6) | 0.030 |

| History of heart failure | 0.978 | |||

| HFrEF | 304 (15.6) | 140 (15.5) | 164 (15.8) | |

| HFpEF | 303 (15.6) | 142 (15.7) | 161 (15.5) | |

| None | 1,339 (68.8) | 624 (68.9) | 715 (68.8) | |

| Cardiomyopathy | 491 (25.2) | 221 (24.4) | 270 (25.9) | 0.558 |

| Hypertension | 1,586 (81.5) | 735 (81.1) | 851 (81.8) | 0.691 |

| Myocardial infarction | 192 (9.9) | 101 (11.1) | 91 (8.8) | 0.076 |

| Coronary artery disease | 997 (51.2) | 469 (51.8) | 528 (50.8) | 0.660 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 530 (27.2) | 248 (27.4) | 282 (27.1) | 0.898 |

| Cerebral vascular accident | 113 (5.8) | 51 (5.6) | 62 (6) | 0.754 |

| Obesity | 921 (47.3) | 447 (49.3) | 474 (45.6) | 0.097 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 476 (24.5) | 242 (36.7) | 23 (22.5) | 0.031 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 11 (0.6) | 6 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 0.594 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 55 (2.8) | 25 (2.8) | 30 (2.9) | 0.867 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 977 (50.2) | 461 (50.9) | 516 (49.6) | 0.576 |

| Dialysis | 19 (1) | 8 (0.9) | 11 (1.1) | 0.695 |

Values are presented as median [interquartile range] or as n (%) as appropriate.

CRT = cardiac resynchronization therapy; HFpEF = heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; ICD = implantable cardioverter defibrillator.

Primary outcomes were all-cause death, ED visits, and hospital admissions at 120 days after the index office visit. ED visits referred to patients who presented to the ED and were discharged without hospital admission. Hospital admissions included both observation and inpatient status. For patients with multiple ED visits or hospital admissions after the index clinic visit, the first occurrence was used. Patients presented to 16 different ED locations and could have been admitted to any of 12 hospitals within our health system.

Secondary outcomes were established quality metrics for the care of patients with AF and investigator-determined indicators of clinical activity in the management of AF. Established quality metrics assessed at the end of the index ambulatory visit included: appropriately prescribed oral anticoagulation (for CHADS-VASc ≥3 in women and ≥2 in men), inappropriate use of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with permanent AF, inappropriate use of class 1C antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with structural heart disease, inappropriate use of dofetilide or sotalol in patients with end-stage renal disease, inappropriate use of a nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction, prescription of a β blocker in patients with an ejection fraction <40%, and inappropriate use of a direct-acting oral anticoagulant in patients with a mechanical heart valve.6, 7 Investigator-determined indicators of clinical activity included: offering of escalation of rhythm control treatment by cardioversion, antiarrhythmic drug therapy, or catheter ablation; electrocardiogram (ECG) review by a clinician within 1 month of the clinic visit (including 12-lead ECG, ambulatory monitor, and stored ECG on pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator) for patients on antiarrhythmic drug therapy; use of ambulatory monitoring (Holter monitors, ambulatory telemetry, and event recorders) within 120 days; and risk factor modification discussions, including hypertension, obesity, exercise, obstructive sleep apnea treatment, and alcohol cessation.

Data are shown as mean ± SD for continuous and number (n; %) for categorical variables. Data were divided into 2 groups (2020 and 2019) and were compared with Student's t test for continuous and chi-square for categorical variables. To address the differences between 2020 and 2019 visits, we used a multivariable logistic regression model. The covariates, which were selected a priori for adjusting the clinical outcomes of hospital admissions, ED visits, and indicators of clinical activity included: age, gender, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, intracranial hemorrhage, cerebrovascular accident, smoking, obstructive sleep apnea, previous ablation, and provider type (physician or advanced practice provider). Because mortality had only 31 events, we used a smaller adjustment list of: CHA2DS2-VASc score, previous ablation, and provider type. A hierarchal model was constructed to account for the effect of clustering by provider and incorporated into the multivariate analysis. Data from this model are shown as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was used for significance testing throughout the study. All analyses were done with SAS 9.4 (Cary, North Carolina).

Results

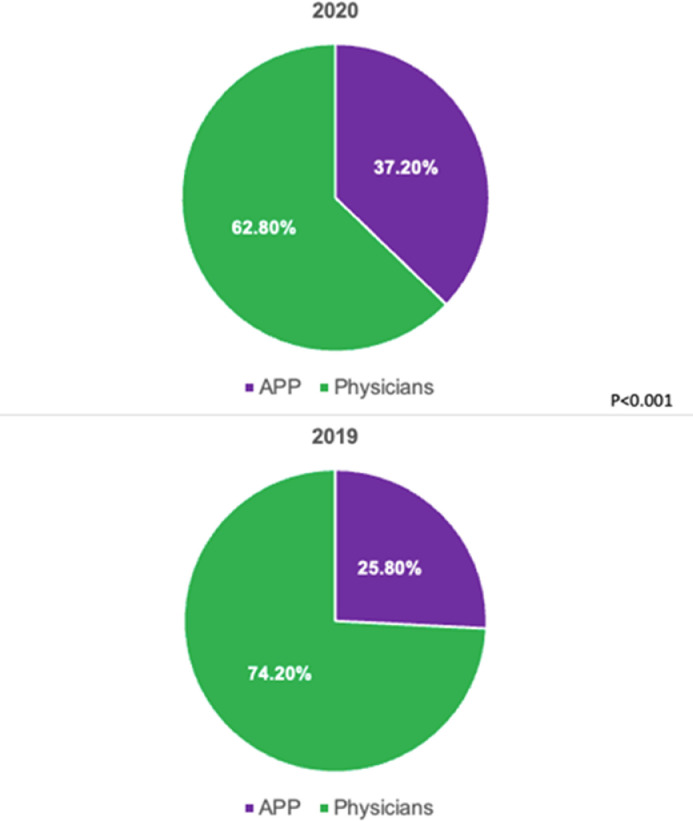

There were a total of 1964 unique patient visits (1,040 in 2020 and 906 in 2019). The vast majority of encounters in 2020 were telehealth (96.0%; Figure 1 ). Telehealth was not used in 2019. Proportions of patients seen by physicians versus advanced practice providers in 2020 and 2019 are shown in Figure 2 . Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The median age was 71.0 years and 94.9% of patients were White, with no difference between the 2 groups. Overall, women represented 41.5% of the study cohort. The majority of patients in both cohorts had paroxysmal AF. Patients in 2020 were more likely to have undergone an ablation procedure before the index clinic encounter, whereas those in 2019 were more likely to have diabetes mellitus.

Figure 1.

Proportion of in-person visits and telehealth visits by year.

Figure 2.

Proportion of visits by provider type. APP = advanced practice provider.

During 120 days after each index encounter, the rates of hospital admission (122 [11.7%] vs 122 [13.5%], p = 0.25) and ED visits (108 [10.4%] vs 113 [12.5%], p = 0.15) did not differ in 2020 versus 2019. There was a total of 31 deaths during the study period, with similar mortality in 2020 versus 2019 (19 [1.8%] vs 12 [1.3%], p = 0.38; Table 2 ). On the multivariate analysis, clinical outcomes remained similar in both cohorts (Figure 3 ). The causes of hospital admission and all-cause mortality are shown in Figure 4 .

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes within 120 d following the index ambulatory visit

| Total | 2019 | 2020 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital admission | 244 (12.5) | 122 (13.5) | 122 (11.7) | 0.248 |

| Emergency department visit | 221 (11.4) | 113 (12.5) | 108 (10.4) | 0.147 |

| Death | 31 (1.6) | 12 (1.3) | 19 (1.8) | 0.377 |

Values are presented as n (%).

Figure 3.

Multivariate analysis of clinical outcomes and indicators of clinical activity in 2020 versus 2019. AAD = AAD = antiarrhythmic drug.

Figure 4.

Outcomes according to year, showing causes of hospital admission (A) and all-cause mortality (B).

There were no statistically significant differences in any of the established quality metrics between 2020 and 2019. Oral anticoagulation was appropriately prescribed in 92.7% of patients overall, with no significant differences in the 2 groups. Most patients who had a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤40% were appropriately prescribed β blockers (87.2% vs 89.9%, p = 0.55). Inappropriate use of antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with permanent AF, inappropriate use of class 1C antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with structural heart disease, inappropriate use of dofetilide or sotalol in patients with end-stage renal disease, inappropriate use of a nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and inappropriate use of a direct-acting oral anticoagulant in patients with a mechanical heart valve were rare and did not differ between the 2 cohorts (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Outpatient quality metrics at index ambulatory visit

| Total | 2019 | 2020 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate anticoagulation decision | 1,804 (92.7) | 850 (93.8) | 954 (91.7) | 0.077 |

| Inappropriate AAD and permanent AF | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0.350 |

| Inappropriate AAD and SHD | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0.186 |

| Inappropriate dofetilide or sotalol in ESRD | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| Inappropriate non-dihydropyridine CCB in HFrEF | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 0.515 |

| β-blocker prescribed when EF ≤40% | 206 | 80 (89.88) | 102 (87.17) | 0.548 |

| Inappropriate DOAC and mechanical heart valve | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.283 |

Values are presented as n (%).

AAD = antiarrhythmic drug; AF = atrial fibrillation; CCB = calcium channel blocker; DOAC = direct oral anticoagulant; EF = ejection fraction; ESRD = end stage renal disease; HFrEF = heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; SHD = structural heart disease.

At the index visit, offering escalation of rhythm control efforts by cardioversion, antiarrhythmic drug or catheter ablation occurred less frequently in 2020 than in 2019 (16.3% vs 23.3%, p <0.001). Ambulatory monitoring within 120 days of the index visit occurred less frequently in 2020 (29.7% vs 51.7%, p <0.001). ECG review by a clinician within 1 month of the clinic visit for patients on antiarrhythmic drug therapy also occurred less frequently in 2020 (22.1% vs 90.2%, p<0.001). There were less new antiarrhythmic drug prescriptions in 2020 than 2019 (13.9% vs 17.5%, p = 0.03), and there was a trend toward fewer new anticoagulant prescriptions in 2020 than 2019 (6.4% vs 8.7%, p = 0.06). Discussions about risk factor modification occurred more frequently in 2020 than 2019 (87.9% vs 74.8%, p <0.001; Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Indicators of clinical activity

| Total | 2019 | 2020 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offering escalation of rhythm control | 381 (19.6) | 211 (23.3) | 170 (16.3) | <0.001 |

| Ambulatory monitoring within 120 d* | 777 (39.9) | 468 (51.7) | 309 (29.7) | <0.001 |

| ECG reviewed within 1 mo of AAD initiation† | 1,047 (53.8) | 817 (90.2) | 230 (22.1) | <0.001 |

| New antiarrhythmic drug prescription | 304 (15.6) | 159 (17.5) | 145 (13.9) | 0.028 |

| New anticoagulant prescription | 146 (7.5) | 79 (8.7) | 67 (6.4) | 0.057 |

| Risk factor modification discussion | 1,592 (81.8) | 678 (74.8) | 914 (87.9) | <0.001 |

Ambulatory monitoring includes Holter monitor, ambulatory telemetry, and event recorders.

ECG review includes 12-lead ECG, ambulatory monitor, and stored ECG on pacemaker or ICD.

Values are presented as n (%).

AAD = antiarrhythmic drug; ECG = electrocardiogram.

On the multivariate analysis, offering escalation of rhythm control efforts (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.95, p = 0.0189), ambulatory monitoring within 120 days (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.3 to 0.44, p <0.0001), and ECG review within 1 month for patients on an antiarrhythmic drug (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.04, p <0.0001) all remained less frequent in 2020 than 2019. There was no significant difference in new antiarrhythmic drug prescriptions (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.05, p = 0.10) or new oral anticoagulant prescriptions (OR 0.75, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.06, p = 0.1). Discussion about risk factor modification remained more frequent in 2020 than 2019 (OR 2.91, 95% CI 2.25 to 3.76, p <0.0001; Figure 3).

Discussion

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic led to a remarkable change in the practice of outpatient cardiology and provided a unique opportunity to assess safety and changes in practice with the use of telehealth compared with in-person outpatient visits. The primary findings of our study are that telehealth visits for patients with AF in a large, multisite electrophysiology practice were associated with (1) similar clinical outcomes; (2) no difference in quality metrics; (3) a lower likelihood of offering escalation of rhythm control therapy, less frequent use of ambulatory monitoring, and a lower rate of ECG review for patients on an antiarrhythmic medication; and (4) more frequent engagement in a risk factor modification discussion. These data support the feasibility and intermediate-term safety of telemedicine in the subspecialty care of patients with AF and have highlighted opportunities for improving this clinical modality.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to the adaption of remote patient management in electrophysiology, and across many specialties. In the United States, the growth of ambulatory teleconsultation was significant, increasing from <50 to >1,000 per day, as evident in a large New York City health system.8 The Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force in late 2020 endorsed the adaption of telehealth visits and the limitation of in-person visits to time-sensitive indications, such as worsening heart failure related to AF, recent implantable cardioverter defibrillator shocks or syncope, suspicion for device malfunction, or suspected device infection.2 It is also important to note that non-COVID-19 deaths attributed to heart disease in the United States significantly increased during the pandemic months.9 Consequently, there has been concern regarding whether AF-related clinical outcomes, quality of care, and ambulatory clinical activity were negatively affected by the adaption of telehealth. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to demonstrate that telehealth visits for patients with AF were not associated with an increase in hospitalizations, ED visits, or mortality in intermediate-term follow-up. Moreover, there were no differences in quality metrics, such as the appropriate use of oral anticoagulation and antiarrhythmic medications. These data provide reassurance regarding the safety and quality of telemedicine in the AF population and extends previous work demonstrating comparable clinical outcomes in other cardiovascular populations, such as heart failure.10 Our findings support the future use of telehealth visits in AF ambulatory care, which is embraced by both patients and physicians11 and underscores its potential impact on areas of healthcare shortage currently affecting 59 million Americans.12

During the pandemic months, recommendations related to electrophysiology procedures called for the postponing or canceling of nonurgent or elective procedures.2 AF catheter ablation in stable patients was considered appropriate to delay, particularly in those without significant risk of hospitalization and without heart failure. In addition, electrical cardioversion for AF was deemed urgent only for highly symptomatic patients or those with rapid ventricular rates not controlled with medications. Otherwise, cardioversion was considered reasonable to delay. Our study demonstrated that rates of rhythm control escalation including catheter ablation and cardioversion were lower in 2020, reflecting efforts to mitigate the risks of in-person encounters. In addition, we found lower documented rates of ECG review by a clinician within 1 month of the clinic visit for patients on antiarrhythmic drug therapy in 2020, despite efforts at our institution to encourage alternative methods of ECG recording and review (remote transmissions from implanted devices, short-duration ambulatory monitoring studies, and patient-recorded ECGs with commercial devices). Patients on antiarrhythmic drugs that required ECG monitoring and laboratory assessments were likely often deferred, particularly if previous evaluations remained stable and no new QTc-prolonging medications were initiated.2

The rates of ambulatory monitoring with Holters, ambulatory telemetry, and event recorders were reduced in 2020. This was a surprising finding, given that these monitors provide potentially important data remotely and would be uniquely advantageous in this setting. Home enrollment of prescribed ambulatory monitors is possible in many instances without the need for patients to present to the clinic or hospital. We hypothesize that the decrease in prescribing ambulatory monitors can partially be explained by medical staff shortages during the pandemic because ambulatory monitors require a well-established system composed of trained technicians, nurses, and other skilled professionals.13 Other monitoring modalities, such a consumer wearable device, may not be as labor-intensive and thus may produce different results; however, these were not measured in our study.

One of the pillars of AF management includes aggressive risk factor modification.14 Our study found that rates of discussing risk factor modification were increased in 2020. This could reflect a strength of telehealth and may result from increased efficiency with virtual encounters and more available time for such discussions. It is also possible that patients or providers find some aspect of the telehealth format more conducive to conversations relating to the patients’ underlying risk factors. These discussions can lead to lifestyle changes, including weight loss, increased physical activity, and other risk factor modification, which have been shown to reduce AF burden.15, 16, 17

Telehealth in the ambulatory care of patients with AF will continue to evolve in the post-COVID-19 era. By offering more flexible access to the healthcare system without a negative impact on clinical outcomes, telehealth is anticipated to persist and likely expand as a complementary format to face-to-face visits in the care of patients with AF. Future efforts are needed to help streamline ECG recording and ambulatory monitoring during times of limited in-person contact. Continued adaption of our current healthcare systems and development of virtual technologies and clinical workflows are all needed to better implement telehealth care models. Further research is needed to inform the continued development and use of telehealth care for patients with AF.

There are important limitations that should be noted for this study. This was a retrospective analysis that leveraged the ‘natural experiment’ of an external situation that led to marked changes in practice. Efforts to address potential biases included the use of a control group studied during the same period from the preceding calendar year and inclusion of ambulatory visits from the same group of physicians and nurse practitioners. The data are from a single, large, midwest health system, which may limit applicability to other regions, patient populations, and healthcare settings. The diagnoses were based on International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes, which are subject to documentation and coding errors. It is possible that unaccounted ED visits or hospitalizations occurred outside our health system and were not reported because we only captured results from the 16 ED locations and 12 hospitals within our health system. Only intermediate-term outcomes were assessed. Further data are needed to confirm the relative safety of telehealth versus in-person visits in the AF population over longer follow-up periods, especially because some of the changes in the processes of care (e.g., ECG review) may take longer than 120 days to result in adverse clinical outcomes. Lastly, the study examined healthcare during a global pandemic. Any observed differences or similarities in clinical outcomes, quality of care, and indicators of clinical activity may be influenced by other factors occurring during the pandemic, apart from the use of telemedicine.

In conclusion, telehealth was associated with similar intermediate-term clinical outcomes and quality metrics for patients with AF compared with traditional ambulatory encounters. Opportunities for improving this care modality were identified, including the use of ECGs and ambulatory monitoring and ensuring that appropriate escalation of rhythm control efforts occurs. Multicenter, prospective studies over longer periods are needed to better understand the safety and efficacy of a telehealth model in the care of patients with AF.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to acknowledge Tracie Breeding, BSN, and Anne Hoffman, BS, for their support in this project.

Footnotes

Dr. Shatla and Dr. El-Zein contributed equally to this manuscript.

Dr. El-Zein is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, under award number T32HL110837.

Funding: none.

References

- 1.Patel SY, Mehrotra A, Huskamp HA, Uscher-Pines L, Ganguli I, Barnett ML. Trends in outpatient care delivery and telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:388–391. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lakkireddy DR, Chung MK, Gopinathannair R, Patton KK, Gluckman TJ, Turagam M, Cheung JW, Patel P, Sotomonte J, Lampert R, Han JK, Rajagopalan B, Eckhardt L, Joglar J, Sandau KE, Olshansky B, Wan E, Noseworthy PA, Leal M, Kaufman E, Gutierrez A, Marine JE, Wang PJ, Russo AM. Guidance for cardiac electrophysiology during the COVID-19 pandemic from the Heart Rhythm Society COVID-19 Task Force; Electrophysiology Section of the American College of Cardiology; and the Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:e233–e241. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bashshur RL, Howell JD, Krupinski EA, Harms KM, Bashshur N, Doarn CR. The empirical foundations of telemedicine interventions in primary care. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22:342–375. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faruque LI, Wiebe N, Ehteshami-Afshar A, Liu Y, Dianati-Maleki N, Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Tonelli M. Alberta Kidney Disease Network. Effect of telemedicine on glycated hemoglobin in diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. CMAJ. 2017;189:E341–E364. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.150885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorodeski EZ, Moennich LA, Riaz H, Jehi L, Young JB, Tang WHW. Virtual versus in-person visits and appointment no-show rates in heart failure care transitions. Circ Heart Fail. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.120.007119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heidenreich PA, Solis P, Estes NAM, 3rd, Fonarow GC, Jurgens CY, Marine JE, McManus DD, McNamara RL. 2016 ACC/AHA Clinical Performance and Quality Measures for Adults with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Performance Measures. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:525–568. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arbelo E, Aktaa S, Bollmann A, D'Avila A, Drossart I, Dwight J, Hills MT, Hindricks G, Kusumoto FM, Lane DA, Lau DH, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Lobban T, Pak H-T, Potpara T, Saenz LC, Gelder ICV, Varosy P, Gale CP, Dagres N, Boveda S, Deneke T, Defaye P, Conte G, Lenarczyk R, Providencia R, Guerra JM, Takahashi Y, Pisani C, Nava S, Sarkozy A, Glotzer TV, Oliveira MM. Quality indicators for the care and outcomes of adults with atrial fibrillation: Task Force for the development of quality indicators in atrial fibrillation of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC): Developed in collaboration with the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Latin-American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) EP Europace. 2021;23:494–495. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa253. Chair(Co-chair), Reviewers(review coordinator) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann DM, Chen J, Chunara R, Testa PA, Nov O. COVID-19 transforms health care through telemedicine: evidence from the field. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:1132–1135. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Weinberger DM, Hill L, Taylor DDH. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March–July 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:1562–1564. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sammour Y, Spertus JA, Austin BA, Magalski A, Gupta SK, Shatla I, Dean E, Kennedy KF, Jones PG, Nassif ME, Main ML, Sperry BW. Outpatient management of heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic after adoption of a telehealth model. JACC Heart Fail. 2021;9:916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu PT, Hilow H, Patel D, Eppich M, Cantillon D, Tchou P, Bhargava M, Kanj M, Baranowski B, Hussein A, Callahan T, Saliba W, Dresing T, Wilkoff BL, Rasmussen PA, Wazni O, Tarakji KG. Use of virtual visits for the care of the arrhythmia patient. Heart Rhythm. 2020;17:1779–1783. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Office of Health Policy, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Report to Congress: e-health and telemedicine. Available at:https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/private/pdf/206751/TelemedicineE-HealthReport.pdf. Accessed on 04/07/2022.

- 13.Slotwiner DJ, Al-Khatib SM. Digital health in electrophysiology and the COVID-19 global pandemic. Heart Rhythm. 2020;1:385–389. doi: 10.1016/j.hroo.2020.09.003. O2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung MK, Eckhardt LL, Chen LY, Ahmed HM, Gopinathannair R, Joglar JA, Noseworthy PA, Pack QR, Sanders P, Trulock KM, American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee and Exercise. Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Secondary Prevention Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology. Council on Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; and Council on Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health Lifestyle and risk factor modification for reduction of atrial fibrillation: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e750–e772. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pathak RK, Elliott A, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Hendriks JM, Twomey D, Kalman JM, Abhayaratna WP, Lau DH, Sanders P. Impact of CARDIOrespiratory FITness on arrhythmia recurrence in obese individuals with atrial fibrillation: the CARDIO-FIT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:985–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.06.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Meredith M, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Wong CX, Twomey D, Elliott AD, Kalman JM, Abhayaratna WP, Lau DH, Sanders P. Long-term effect of goal-directed weight management in an atrial fibrillation cohort: a long-term follow-up study (LEGACY) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2159–2169. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pathak RK, Middeldorp ME, Lau DH, Mehta AB, Mahajan R, Twomey D, Alasady M, Hanley L, Antic NA, McEvoy RD, Kalman JM, Abhayaratna WP, Sanders P. Aggressive risk factor reduction study for atrial fibrillation and implications for the outcome of ablation: the ARREST-AF cohort study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2222–2231. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]