Abstract

The outbreak of COVID-19 has underscored the vulnerability of our current food systems. In China, following a series of strategies in guaranteeing food security in the past decades, the pandemic has further highlighted the necessity to strengthen urban-rural linkages and facilitate the sustainable development of local agri-food systems. The study for the first time introduced the City Region Food Systems (CRFS) approach to Chinese cities and attempted to holistically structure, analyze and promote the sustainability of local food systems in China. Taking Chengdu as an example, the study first took stock of existing concepts and policies in China and the city, and defined the high-quality development goals of CRFS for Chengdu. An indicator framework was then developed to serve as a CRFS assessment tool for identifying existing challenges and potentials of local food systems. Further, a rapid CRFS scan using the framework was conducted in Chengdu Metropolitan Area, providing concrete evidence for potential policy interventions and practice improvement in the area. The study has explored new paradigm of analysis for food related issues in China and provided supporting tools for evidence-based food planning in cities, which collectively contribute to the food system transformation in a post-pandemic scenario.

Keywords: City Region Food Systems, High-quality development, Food policy, indicator framework, Chengdu Metropolitan Area, Integrated urban-rural development

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has completely altered the world's normality. In addition to the exposed issues in the health system and city governance system, emerging challenges faced with the food systems are also widely observed worldwide. Various degrees of disruptions have been observed along the agri-food chains during the COVID-19 lockdown. On the production side, issues such as labor shortage, limited access to agricultural inputs and restrictions in agricultural operations had led to short food supply, reduced income of farmers and higher food losses in the field (Fei & Ni, 2020). From the consumption perspective, variables that constrained the traditional food distribution and selling channels had seriously affected food access, especially for the vulnerable populations and in big cities (FAO, 2020). With high food demands but limited production capacity, cities are witnessing high vulnerabilities of their local food systems.

By 2050, the global population will reach 9.7 billion, 68 % of which will live in cities (United Nations, 2018). The rapid population growth and urbanization process, together with increasing external challenges such as the climate change and public health emergencies, have stressed the risks faced with the urban food systems in securing high-quality food supply (Grewal & Grewal, 2012). In 2020, a total of 720–811 million people globally were in hunger and 34.4 % of children under five years old were at malnutrition status (FAO, 2021). More than 50 % of adults were obese or overweight, suggesting common problems in healthy food access and consumption. Further, a third of the global anthropogenic GHG emissions were estimated to be attributed to our current food systems, the negative environmental impacts of which will in turn adversely affect agricultural production and food supply systems (Crippa et al., 2021). Collectively, actions need to be taken from all respects to transform the current food systems and contribute to the sustainable development goals.

Paradigm in food system transformation initiatives has been shifting in the past decades, from the reductionism to systems theory and approaches. Research in this field used to be conducted from single disciplinary perspective and focused on individual component of the system. For instance, production-focused approaches are often used to improve crops' productivity without consideration of supply chain capacities, consumer diet demands or the impacts of the food production towards the social and natural environment (FAO, 2018). Considering the complex and cross-disciplinary nature of the food system, the system thinking has been increasingly adopted in food-related research and governance, which concerns not only individual elements' status and behaviors but also the interactions among different elements in a system and the dynamics of broader environments the food system is embedded in Schebesta and Candel (2020).

The concept of “food system” was originally put forward by Marion (1986) to represent the sum total of relationships between the agriculture sector and the downstream actors along the food chain. Sobal et al. (1998) incorporated the nutrition dimension and expanded the concept to “food and nutrition system” which includes three subsystems (producer, consumer and nutrition) and covers nine stages from production in the field to metabolism in human's diets. Ericksen (2008) paid more attention to the global climate change situation and conceptualized the food system framework by emphasizing the trade-offs among environmental, social and food security outcomes. According to the developed food security definition that encompasses food availability, food access and food utilization, a series of food system drivers, activities, outcomes and feedback cycles were identified to illustrate the food system dynamics (Ingram, 2011). In 2014, the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition (HLPE) defined the food system as a system that “gathers all the elements (environment, people, inputs, processes, infrastructures, institutions, etc.) and activities that relate to the production, processing, distribution, processing, distribution, preparation and consumption of food, and the output of these activities, including socio-economic and environmental outcomes” (HLPE, 2014). The above evolution in food system concepts provide fundamental theoretical basis for the application of systems approaches in food security and nutrition research and policy making.

Further to this, an increasing number of literature has looked at the structure, functions and interactions of the food systems to identify potential leverage points of improvement. For example, Nourish (2020) developed a food system circle that encompasses farming, economic, environmental and social parts and illustrates relations in between the biological system, economic system, social system, health system and political system through the lens of food. (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2016) applied concentric circles to describe the food systems by locating “diet quality” in the center and subsequently “consumer”, “food environment” and “food supply system” oriented away from the center point. Food system wheels developed by FAO (2018) and Bhunnoo and Poppy (2020) both recognized the food chain as the core system and concerns its interrelationships with the society, environment, economy, health and politics systems. From a value chain perspective, Hussain and Vause (2018) analyzed the food system feedback and impacts across four stages of the value chain, namely agricultural production, manufacturing & processing, distribution, marketing and retail, and household consumption, with the human capital, social capital, produced capital and natural capital included in the interrelationship analysis. Food system framework developed by Posthumus et al. (2021) divided the food supply system into five sections, including agricultural production, food storage, transport & trade, food processing & transformation, food retail & provisioning, and food consumption, with influential factors such as the enabling environment, food environment, business services and consumer characteristics considered in food system activity analysis. In latest versions of HLPE reports, the sustainable food system framework identified food supply chains, food environments and consumer behaviors as key elements of food systems, which are influenced by five categories of drivers (biophysical and environmental, technology and infrastructure, economic and market, political and institutional, socio-cultural, demographic) and deliver five categories of outcomes (nutrition, health, economic impacts, social equity, environment) (HLPE, 2017, HLPE, 2020). To further investigate the causality and driving mechanisms of the system, measures such as causal loop diagrams and mathematical modeling are applied in some studies (Zhang et al., 2018; Posthumus et al., 2021, Allen & Prosperi, 2016, Nicholson et al., 2020, Béné et al., 2019). As such, through systematic investigation of the structure, evolution and regulation pathways of the food systems, the systems approaches are increasingly used to explain and respond to food security and nutrition issues in faced with global challenges such as climate change, urbanization, population growth and depletion of natural resources (FAO, 2018; Si & Scott, 2016).

In this context, tools to assist food system analysis, food governance and policy making have been developed at various scales. For instance, the Food Systems Decision-Support Toolbox sets a five-step protocol started with defining policy objectives of the given region, followed by the analysis of food system actors, characteristics and behaviors, which then lead to policy and actionable recommendations (Posthumus et al., 2021). The four-action tool developed by UNEP (2019) follows four stages in promoting food systems transformation, including food systems advocacy and training, food systems assessment of impacts, policies and actors, multi-stakeholder dialogue and long-term capacity building and governance. The City Region Food System Toolkit developed by FAO, RUAF, and Wilfrid Laurier University (2018) supports cities in urban food system mapping and planning by gathering information and establishing multi-stakeholder platforms. Looking into food system assessment tools, the Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems Guidelines evaluates the agri-food system sustainability through four dimensions: good governance, environmental integrity, economic resilience and social well-being, by assessing a total of 17 themes and 58 indicators (FAO, 2014). The Food Sustainability Index assessed three pillars of the food systems, namely nutrition, sustainable agriculture, and food loss and waste, to investigate challenges, solutions and best practices of food systems across the world (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2018). The Food Systems Dashboard referred to HLPE's (2017) conceptual framework and applied more than 140 indicators to monitor food supply chains, food environments, individual factors, consumer behavior, diets and nutrition, environment and drivers (Fanzo et al., 2020). The food system assessment framework developed by the U.S. National Academies consisted of four principles and six steps, which measured food system effects through three domains including health, environment, and the social and economic domains. In each domain, quantity, quality, distribution and resilience were measured to evaluate the sustainability of the food system (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2015).

Provided the fact that the performance of food systems are very specific to the local context, and that the disjunction of urban and rural areas is a main challenge for food system sustainability, more territorial food system approaches such as the City Region Food Systems (CRFS) approach are gaining increasing attention, which links urban centers with their surrounding peri-urban and rural hinterlands, and carries out food systems analysis and interventions through a City-Region lens (Blay-Palmer et al., 2018; Jennings et al., 2015; Vittuari et al., 2021). Since 2015, FAO's City Region Food Systems Programme undertakes a multi-sectorial, multi-stakeholder and multi-level approach to: “(a) assess linkages and resource flows between rural and urban areas, key actors, policies and legislation, sustainability, risks and current and future vulnerabilities; and (b) plan policy actions to build resilience and sustainability” (Blay-Palmer et al., 2020). In the pilot cities of the CRFS Programme, the CRFS approach and tools have positively contributed to local food security and regional sustainable development goals. Particularly during the COVID-19 epidemic, the CRFS methodology has supported the pilot cities with positive responses to the crisis and strategic food planning for building back better (Blay-Palmer et al., 2020). Similar approaches are also emerging in countries such as the USA, UK and Canada, with adapted tools developed and applied locally to inform food policies and promote urban food system resilience and sustainability (Biehl et al., 2018; Food Systems Transformation Group, 2022, Zeuli et al., 2018). Urban agriculture, a key component of the City Region Food Systems, is also gaining increasing attentions in recent years and recognized as an important contributor in urban-rural linkages and food system resilience. Urban agriculture is generally defined as the production of food and other outputs and related processes that are taking place within cities and surrounding regions (FAO et al., 2022). Practices of urban agriculture vary across countries and cities, some carried out for basic food access on a home scale, while some taking advantage of the educational and recreational functions of urban agriculture that serves city dwellers' social and cultural needs in life. Innovative production systems such as the plant factory are also emerging worldwide targeting commercialized model which could achieve high-intensity, space-saving and environment-friendly food production and contribute to food security in mega-cities (Wang et al., 2021).

In Chinese cities, many good practices in local food systems, such as efficient cross-level governance and the application of digital technologies, have been observed and especially reflected during the COVID-19 responses (Fei & Ni, 2020; Fei et al., 2020). However, further to the supply side improvement which has already been paid great attention by academia and policy agenda, two major gaps across the food systems still exist: (1) the lack of linkages between the production and consumption ends, leading to the mismatch between consumers' nutritional dietary demands and the agricultural production supply; (2) barriers of effective synergies among different sectors and lack of evidence-based tradeoffs among sub-systems. Holistic approaches such as the CRFS approach are needed to measure, analyze and improve the performance of cities' food systems through multiple layers, which could in turn support cities in achieving the goals in food and nutrition security and high quality development.

This paper for the first time introduces the concept of CRFS to Chinese cities, attempting to adopt the systems theory and emerging food systems approaches for assessing the food systems of a given city region in China and supporting the local food planning in a holistic and evidence-based manner. By incorporating the goals in agri-food system transformation with overarching development strategies such as the rural revitalization and high quality development strategies, the study identified the high quality development goals of CRFS tailored for the pilot Chinese city, Chengdu, and developed an adapted assessment framework to assist local food system mapping and analysis. The case study in the Chengdu Metropolitan Area provided knowledge of the local scenario as well as a good basis for further local assessments and food planning. Overall, the paper presented an empirical study that explored the application of systems theory in agri-food system governance and verified the effectiveness of the City Region Food Systems methodology in a Chinese city. In addition, through a closer analysis of the food systems in Chengdu's city region, the study also provided adaptable tools for local food system assessment and systematic information to support local food policy and regional high quality development goals. The outputs of the study have reinforced the theoretical development of the food system paradigm at a city scale and would enlighten food governance systems in practice for cities globally especially those with similar development stage as Chengdu.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research design

Upon an extensive analysis of existing theories and methodologies, the present study hypothesized that the food systems approach can be effective in Chinese cities to systematically analyze local food systems and inform food decision making, aimed to facilitate food system transformation and contribute to regional development goals. The study conducted an empirical research by adapting and applying the CRFS methodology in a Chinese city according to the local context, which leads to in-depth understanding of the local food systems and policy implications for cities of its kind. Specifically, Chengdu and its metropolitan area were identified to be a typical city-region area and selected for the case study, due to its rapid increase of urban population, advanced practices in urban-rural linkages and significance of the agri-food sector in city development. The case study design followed the CRFS methodology and consisted of the policy review, food system goal definition, development of the food system assessment framework and the pilot assessment through primary and secondary data collection and analysis. Policy recommendations for Chengdu's city-region area and implications for other cities worldwide were provided in the end.

2.2. Study area

Chengdu is the capital city of Sichuan province and an important meg-city in western China. In 2020, the total inhabitants in the city exceeded 20 million, ranking at the fourth place among all cities in China. The Gross Domestic Products of Chengdu was 1771.7 billion yuan in 2020, occupying 36.4 % of the total GDP in Sichuan province. In the past ten years, the city's residents were increased by 5.8 million, with the urbanization rate raised from 65.75 % to 78.77 %. A considerable GDP growth by 219.16 % was also witnessed as compared to 2010, indicating the impressively rapid growth and strategic potentials of the city (Statistic Bureau of Chengdu and Leading Group Office of the 7th National Population Census of Chengdu, 2021; Statistic Bureau of Chengdu & NBS Survey Office in Chengdu, 2020). In 2016, Chengdu was officially designated as one of the nine national central cities in China, recognized as a key hub of economy, science and technology, culture, international exchange and transportation junction. In 2020 the guideline document for developing the Chengdu-Chongqing city cluster were officially endorsed, marking a strong political will to support the coordinated development of the region and strengthen the strategic position of the two core cities (Chengdu, Chongqing) as regional growth engines.

The Chengdu Metropolitan Area (CMA), encompassing Chengdu and three smaller cities in the surroundings, is a key area leading the development of Sichuan province as well as the Chengdu-Chongqing city cluster. Located in the Chengdu Plain where natural resources are ample, CMA has unique advantages in food production and development potentials in many aspects. Population and GDP of CMA constitute a large proportion in that of Sichuan province (Section 3.3), suggesting important roles CMA is playing in regional development. In 2020, a CMA working team consisted of governmental authorities from the four cities was established to coordinately steer cross-boundary communications and cooperations. A three-year development plan of CMA was subsequently released, in which eight pillars of coordinated actions were identified and translated into a range of implementation programs that also cover the food and agriculture sector.

2.3. Food policy review

A policy analysis was conducted to gain full understanding of the local development goals and priorities. Given that city food policies in China are in line with agri-food strategies developed by provincial and central governments, the analysis of the present study covers policies released from cross-level administrations, including Chengdu city, Chengdu Metropolitan Area, Chengdu-Chongqing city cluster, Sichuan province and China. A total of 42 documents of strategies, guidelines, action plans, policies and laws issued in the past two decades were gathered and analyzed in detail. The topics of these selected documents were considered with potential correlations to local CRFS concepts and goals, including the national overall development, urban development, agriculture and food industries, rural areas and rural people, environment protection, nutrition and health. Key milestones were extracted and presented in the Result Section. The full list of the documents is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Taking a closer look on the local actions in Chengdu and its surrounding areas, a further analysis was conducted on four main categories of plans across different administrative scope, including the 14th Five-Year Plans for Chengdu city, Sichuan province and China respectively, the rural revitalization strategic plans for Chengdu city, Sichuan province and China respectively, the urban/regional development plans for Chengdu city, Chengdu Metropolitan Area and Chengdu-Chongqing city cluster respectively, and the agricultural development plans for Chengdu city, Chengdu Metropolitan Area, Chengdu-Chongqing city cluster and Sichuan province respectively. Word frequency of the planning documents was analyzed by category through a word frequency statistics software written with the Python algorithm. Ranking of the words by frequency of presence was then obtained to assist the identification of the policy hotspots.

2.4. Development of the CRFS framework

The indicator framework for CRFS assessment was adapted from the CRFS framework developed by Carey and Dubbeling (2017). A 5 × 5 matrix of the food flow chain crossing the five identified themes was established as the skeleton of the framework. The nodes of the food flow chain were adjusted to better suit the local situation. Indicators were then selected to fill in the matrix frame. A four-step selection process was applied: (1) consolidation of existing indicators from food system framework in other literature (Carey & Dubbeling, 2017; Fanzo et al., 2020; FAO, 2014; FAO et al., 2019; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2018; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020; Vieira et al., 2018); (2) nomination of new indicators according to the identified CRFS objectives in each theme; (3) combination of (1) and (2) and screening process that took comprehensiveness and applicability into consideration; (4) internal consultation to verify and decide on the indicators to be included.

2.5. Data collection for the case study in CMA

Both secondary data from desk research and primary data from field surveys were included in the case study in CMA. Secondary data was collected from statistic yearbooks, reports and public database. Specifically, the socio-economic data on GDP, population, total land area, annual yield and annual consumption quantity was obtained from the latest Statistic Yearbooks of Sichuan province and four cities in CMA respectively. Data regarding the agro-tourism industries, namely total number of rural tourists, total income of rural tourism and estimated household number involved in rural tourism businesses were based on Sichuan Yearbook, Sichuan Tourism Yearbook, Sichuan Rural Yearbook, China Tourism Statistical Yearbook and county statistic data extracted from statistical bureau reports of respective city.

Field surveys were carried out to collect primary data on the CRFS performance and challenges in all four cities in CMA. A consultation meeting was arranged for each city respectively, attended by governmental officials from relevant departments including the Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the Development and Reform Commission, Bureau of Commerce, Bureau of Resource and Planning, Bureau of Economic and Information Technology, Bureau of Culture, Broadcast-TV and Tourism and related officers from local counties. A total of 59 open-ended interviews were conducted with food system stakeholders on their practices, challenges and suggestions. The selection of stakeholders fully considered the balance between different types of actors, nodes of value chains, agricultural product categories and geological distribution. In addition, seventeen consulting interviews were conducted with experts with rich research background in the agri-food field, from which the assessment outputs were discussed and policy recommendations were put forward. Data collected from the consultation meetings, stakeholder interviews and expert interviews was collectively analyzed to identify the strengths and weaknesses, as well as good practices of the CRFS in CMA.

3. Results

3.1. Policy analysis

Given that the food systems of a given city region are important parts of the overall development of the region encompassing both urban and rural areas, a review of development strategies, guidelines, action plans, policies and laws was conducted first to understand the localized development priorities and define the food system goals accordingly. In the present study, Chengdu City and its surrounding areas were taken as the “city region” for piloting the CRFS approach, so the scope of the present policy analysis covered food system related policies released by different levels of administration that apply to Chengdu and its surrounding regions, including the city of Chengdu, the Chengdu Metropolitan Area, the Chengdu-Chongqing City Cluster, Sichuan Province and China.

In the past decades, cities in China have experienced significant changes in urbanization, industrialization, economic growth and livelihood improvement. Fig. 1 demonstrated a 30-year timeline of urbanization with policies considered to be key driving factors for agri-food system transformation highlighted, which suggests the change of development phases and the adjustment of policy priorities accordingly. Based on an analysis of these policies, the main goal of food systems in Chengdu's city region and multidimentional objectives could be identified.

Fig. 1.

An overview of development strategies and food policies issued in the past 30 years in China. The orange bar represents the national urbanization rate (United Nations, 2018).

3.1.1. Overarching vision of development

The overarching national and regional development goals will provide fundamental guidance for identifying food systems goals and possible actions. In the context of China, along with the long-term efforts in building a modern society, the development theories evolved from the Scientific Outlook on Development put forward in 2003 that promotes comprehensive, coordinated and sustainable development, to the new development philosophy proposed in 2015 with the vision of innovative, coordinated, green, open and shared development (Liu & Du, 2021). The Five-sphere Integrated Plan was raised in 2012 that structured the overall development into five aspects, including the economic, political, cultural, social and ecological fields. With the aim to make significant progress in all aspects, the Five-sphere Integrated Plan provides a skeleton framework for concrete planning and actions in various regions and sectors. In 2017, the concept of high-quality development (HQD) was presented for the first time at the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC), indicating the new development paradigm of China's economy transitioning from rapid growth to high-quality development aiming to achieve better quality, more efficient, fairer, and more sustainable development. The HQD has become an overarching vision ever since, pillared by the implementation of the new development philosophy and the Five-sphere Integrated Plan.

3.1.2. City development strategies

In line with the overarching development vision, strategies of city development are also transforming towards better quality and sustainability in all respects. The New Urbanization Strategy was put forward in 2012, aiming to explore a new path of urbanization suitable for Chinese cities. Pillars of the new urbanization include urban-rural integration, city-industry interaction, economical resource utilization, eco-environment protection and harmonious development. In 2015, the National Urban Work Conference claimed that cities should follow the law of urban development and strengthen coordination in five dimensions, including coordination across the arrangements of space and industry, across action steps, across diverse drivers, across strategies of different fields and across all types of stakeholders. In the action guidelines of the new urbanization released in 2021, six key objectives of urban development were proposed, including livability, innovation, intelligence, green, culture and resilience (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2014; National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), 2021). For Chengdu in particular, the goals of building the Park City were raised in 2018 (CPNRB, 2019). The Park City Initiative follows a people-centered strategy, by establishing the “people-city-environment-industry” framework and incorporating the city's ecological value, aesthetic value, humanistic value, low-carbon economic value, healthy living value and social value in the urban planning and strategies. In addition, the city plan of Chengdu recognizes the significance of promoting agriculture and green spaces by paying efforts to well balance spaces for urban built-up areas, ecological areas and agricultural areas. A range of agricultural zones, urban agriculture functional zones and urban-rural integration zones were identified to foster local food security and regional development (CPNRB, 2021).

3.1.3. Linking urban and rural areas

In face of the fact that the rapid urbanization and industrialization in cities have led to imbalanced development and gap of wealth between urban and rural areas, strengthening urban-rural integration has been a policy priority in China since the Scientific Outlook on Development first included coordinated development of urban and rural areas in the strategies. In 2005, the fifth Plenary Session of the 16th CPC Central Committee outlined the overarching goals for new socialist countryside construction, portraying the “new countryside” to feature “advanced production, well-to-do life, civilized folkways, a neat look, and democratic management”. As part of the initiative, public financial resources were allocated to support rural development and urban-rural integration programs. Following this, the No.1 Central Document released in 2006, 2007 and 2010 continuously stressed the importance of integrating urban and rural development and supporting modern agriculture development to facilitate the new socialist countryside construction (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2006, CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2007, CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2010). In the New Urbanization Strategy and following action guideline documents in recent years, “integrated urban-rural development” was the official discourse consisting of actions such as improving the supporting policy systems, promoting bidirectional flow of production factors and balanced allocation of public resources, and transforming relations between the industry and agriculture sectors (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2014; National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), 2019, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), 2020, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), 2021). A more recent significant milestone to facilitate the integrated urban-rural development and benefit rural people is the National Rural Revitalization Strategy demonstrated at the 19th CPC National Congress in 2017, featuring the overall objectives in thriving businesses, pleasant and eco-friendly environment, social etiquette and civility, effective governance, and prosperous population in rural areas. Continuing China's huge achievements of poverty elimination in 2020, guidelines, laws as well as new administrative bodies in rural revitalization were subsequently developed early in 2021 to accelerate the modernization of agriculture and rural areas and contribute to the national high-quality development (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2021; NPC Standing Committee, 2021, NPC Standing Committee, 2021).

3.1.4. Evolution of food policies

Along with the development phase transitions and change of overall development priorities, the agri-food sector is also witnessing an evolution process, contributing a crucial portion to the high-quality development of urban and rural areas. Targeting the four dimensions of food security objectives including food availability, food access, food utilization and stability, a range of policies have been developed to support activities across the food chains. The No.1 Central Document in 2005 mainly focused on raising the overall agricultural production capacity, suggesting the prioritized demand to guarantee food security in the early ages. In 2007, the No. 1 Central Document demonstrated the necessity of utilizing modern technologies, modern industrial systems and modern operation approaches to improve the capacity, quality and profit of the food supply systems. The document for the first time established a comprehensive framework to guide actions in developing modern agriculture in China, including 1) increasing support, investment and safeguard mechanisms in agriculture and risk prevention of agricultural entities; 2) facilitating agricultural infrastructure construction, facility improvement and farming sustainability improvement; 3) promoting science and technology innovation in agriculture, such as resource-saving, mechanization and informatization technologies; 4) developing multiple functions of agriculture and diversifying relevant industries such as health aquaculture, characteristic agriculture and biomass industries; 5) strengthening the market systems with improved logistics and food quality monitoring and services; 6) educating new farmers with professional farming and managing skills; 7) innovating governance mechanisms in rural areas; 8) improving cross-level management for better implementation of agriculture modernization initiatives (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2005, CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2007). The modernization of agriculture has since then become a mainstreamed goal in food policies in China, considered to be key for improving food availability and access. In face of the increasing challenges of the agri-food supply systems, another key milestone of food policy in China, the supply-side structural reform in agriculture, was introduced during the National Rural Work Conference in 2015. The overall objective is to improve the efficiency and quality of the agri-food supply systems, which will meet consumers' needs and increase producers' incomes (Chen, 2017). On the consumption side, the Health China Initiative announced in 2016 supports activities in promoting food education, improving citizen's dietary habits while strengthening food safety supervision, which facilitates the food utilization of citizens and constitutes a crucial part of sustainable local food systems (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2016; Health China Initiative Promotion Committee, 2019). The National Nutrition Plan (2017–2030) released by the State Council in 2017 targeted to substantially reduce nutrition-related diseases through actions such as improving nutrition legislation, promoting scientific research in food nutrition, facilitating nutrition and food safety evaluation systems, and raising public awareness in nutrition and health (General Office of the State Council, 2017). More recently, the issuing of the anti-food waste laws has suggested the increasing political intentions to improve food system sustainability from multiple dimensions in a more systemic way (NPC Standing Committee, 2021, NPC Standing Committee, 2021). Further, a national policy to strengthen agri-food supply chain systems was released in 2021, which aims to increase public agricultural markets in cities, support cold chain infrastructure construction, expand network of food retailing, improve food product precooling capacities of the production sites, strengthen production-consumption matching mechanisms and optimize the food distribution network (Office of the Ministry of Finance and Office of the Ministry of Commerce, 2021). In line with this, Chengdu's municipal government released the 14th Five-Year Development Plan for the Construction of Agricultural Product Distribution Systems developed by a total of eight bureaus, providing concrete guidelines in improving local food supply systems and increasing citizens' food security levels.

3.1.5. Identification of policy hotspot

A word frequency analysis was carried out on various scales of development plans to assist the identification of policy hotspot in the next period of time, either political objectives or levers of actions, to be taken into consideration when defining the CRFS prioritized objectives. Four main categories of plans that are directly or indirectly related to the CRFS development were included in the analysis, including the agricultural development plans, the rural revitalization plans, the economic and social development plans and city and/or region development plans. As shown in Fig. 2 , words with top frequency of presence in all four categories include industry, innovation, system/mechanism, modernization and service, indicating the crucial roles these elements will be leading in the development of all these four aspects and potentially, in the development and transformation of the CRFS. Besides, attention are also to be paid to several key words with high frequency of presence in more than one policy category, including economy, culture, society, ecology, governance, infrastructure, characteristics, platform/hub, coordination/collaboration and integration.

Fig. 2.

Word frequency analysis of the plans for agricultural development, rural revitalization, economic and social development and city/region development. The top ten words with the highest frequency of presence in each category were presented in the descending order. Words in red are the five most frequent words present in all four categories.

3.2. Defining the CRFS framework

3.2.1. Conceptual framework

Building on the analysis in Section 3.1 over the strategies and policies that are directly and indirectly related to the City Region Food Systems, three key points were made to guide the formulation of the CRFS conceptual framework adaptable for Chengdu and potentially other Chinese cities. (1) China is experiencing a crucial transition phase from rapid growth to high quality development, when the HQD strategies set overarching development framework for all sectors in China. Thus, the national HQD vision, together with the new development philosophy and the Five-sphere Integrated Plan, should be the structural basis for conceptualizing the HQD of CRFS and defining corresponding goals in Chinese cities. (2) Rural revitalization, urban development, as well as the integrated development between urban and rural areas, are top priorities to achieve the HQD goals at the current stage in China. Since CRFS is a pivotal component in both rural and urban development and plays crucial roles in urban-rural linkages, the objectives and strategies in rural revitalization, new urbanization and integrated urban-rural development should serve as fundamental references for identifying the CRFS priorities. (3) From a more microscopic perspective, the hot words identified in Fig. 2 indicated the policy priorities in the following years, thus should be taken into consideration during the identification of HQD goals for CRFS.

Based on the three points illustrated above, a conceptual framework for the HQD of CRFS was developed to demonstrate how the main HQD goals of CRFS were identified and what the prioritized areas are according to the context of Chinese cities (Fig. 3 ). The HQD goals of CRFS were developed under the overall umbrella of the HQD vision, following the principles of the new development philosophy and the Five-sphere Integrated Plan and closely targeting the five objectives of rural revitalization and six objectives of urban development. To consistently support the high-quality development goals in a five-sphere perspective, the prioritized areas of objectives and actions in CRFS, consolidated from the policy analysis (Section 3.1), were structured into five main themes covering the governance, economic, environmental, cultural and social aspects. Specifically, in the theme of “good governance”, reforms and innovations in systems and mechanisms are frequently recommended in many respects as suggested in Fig. 2, a main part of which is to facilitate coordination in different dimensions such as between urban and rural areas, within metropolitan areas and between domestic and international partners. Laws, regulations and policies in regards to the food chains are also to be improved accordingly. In the economic aspect, it is a major objective to achieve modernization of agriculture and rural areas. Systems of production, operation and the industries are to be transformed to better serve the food availability dimension of local food security objectives and contribute to the high-quality development of the agri-food sector. Innovations are required in both supply side that aligns to the supply-side structural reform in agriculture and consumption side that improves consumption scenarios and healthy food access. Urban agriculture is also a highlighted topic especially in development plans of Chengdu and the wider surrounding areas, suggesting its great values in city and region's development as well as in achieving the HQD goals of CRFS. In terms of “environmental integrity” which is a main target in the national HQD goals, the city region food system's contributions may include but not limit to the reduction of food losses and waste, increase of ecological services, reduction of the air and water pollution, promotion of green agriculture and product systems, development of resource circulation systems and establishment of agricultural parks in cities for better park city scenes. For cultural preservation, it is planned to promote characteristic agriculture and food chains featuring rich culture of local agriculture and food. More agricultural products with Geographical Indication and regional public brands are expected in near future. For Chengdu in particular, plans to build the ‘City of Gastronomy’ include actions in promoting local agri-food culture, innovating food consumption scenarios and improving quality local food supply chains and services, which could be an important lever to protect and disseminate the characteristic culture of Chengdu city and Sichuan province. The social wellbeing, to which CRFS is closely linked, has a main priority to promote people's health through balanced diets as demonstrated in the Health China Initiative planned for the next ten years, which will improve the food utilization dimension of local food security goals (CPC Central Committee and State Council, 2016). Additionally, actions to increase farmers' incomes, support the vulnerable areas, provide capacity building activities and foster food system actors' associations and fair profit distribution are also in great need to improve people's livelihood.

Fig. 3.

A conceptual framework illustrating the HQD goals and prioritized areas for CRFS in Chengdu and potentially in other Chinese cities.

3.2.2. Assessment indicator framework

In alignment with the identified concepts and targets, comprehensive assessments of the food system performance and impacts are necessary to identify gaps, challenges and opportunities for the high-quality development of CRFS, which could provide concrete evidence for better decision making in food planning. By taking stock of the food system analysis frameworks in literature while targeting the local HQD objectives of CRFS, an indicator framework to monitor CRFS in Chinese cities was developed as illustrated in Fig. 4 (Carey & Dubbeling, 2017; Fanzo et al., 2020; FAO, 2014; FAO et al., 2019; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2018; The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020). The framework follows the five themes identified in Section 3.2.1 and sets indicators along the agri-food chains from production to consumption, taking into account all actors, activities and relations involved in the system. In particular, the economic theme concerns the main food flow chain, in which the food system's interactions with local economy, the capacities of high-quality food supply and food access are evaluated to understand the economic contribution and food security status. The governance theme assesses existing CRFS related policies, implementation systems and mechanisms as well as stakeholder perception on these two aspects, in order to evaluate to what extent the current governance provides enabling environment and sufficient support for HQD of CRFS. The theme of environment is concerned with the food system's ecosystem services and negative ecological impacts, quantity and interventions of food loss and waste and the degree of resource circulation within the food systems. In the social theme, three aspects of assessments are included to evaluate if healthy food is sufficiently supplied and properly consumed, if the rights and interests of all actors are well protected and continuously improved, and if educational activities such as capacity building training and food education courses are frequently provided. Further, the culture theme of CRFS can be an important contributor to the cultural progress goals included in the Five-Sphere Integrated Plan, in which the protection, transformation and export of local agriculture and food culture are monitored and intervened as required. Collectively, it is expected that the performance and progress of the five themes are regularly monitored to guide planning and practices towards the high-quality development of CRFS in China.

Fig. 4.

A comprehensive indicator framework for CRFS assessment in Chinese cities.

3.3. Case study: a snapshot of CRFS in the Chengdu Metropolitan Area

Based on the identified local priorities and assessment framework, a closer look was taken on the Chengdu Metropolitan Area (CMA) to have a preliminary CRFS profile and form a basis for following in-depth assessments and improving actions in the region. Interviews were conducted with stakeholders from CMA's four cities to understand the current status, existing challenges and potential opportunities. Good practices that contribute to HQD goals of CRFS were collected as references to enlighten future planning and practices.

CMA encompasses Chengdu and three surrounding cities including Deyang, Meishan and Ziyang (Fig. 5 ). Chengdu is the capital city of Sichuan province and the most developed city occupying the largest area, thus serves as the core city of CMA leading the regional development in many aspects. Taken as a whole, CMA is recognized as important centers of economy, transportation, trade, manufacturing, innovative technology and agriculture in Sichuan province. The Gross Domestic Product of CMA was 2230 billion yuan in 2020, approximately 45.9 % of the total amount in Sichuan province. The total area of CMA is 3.31 million hectares, with 31.34 million residents living in the area (37.42 % of total residents in Sichuan province) to be fed by either the local food production or imported food products. Resources in CMA for agricultural production are relatively ample as compared to many other regions in China, given its advantageous location at the hinterland of Chengdu Plain and next to the Dujiangyan Irrigation System that benefits agricultural irrigation of the entire province. The province has released the Three-Year Action Plan for the Development of Chengdu Metropolitan Area (2020–2022) in 2020, indicating the strong political will in facilitating synergies within the area, as well as good opportunities to promote the CRFS high-quality development in CMA.

Fig. 5.

The map for Sichuan province. The Chengdu Metropolitan Area is indicated with the grey color, in which Chengdu city is highlighted with the orange color. For reference, Chongqing Municipality is on the right of the city of Ziyang. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3.1. Economic resilience

From an economic and food security perspective, the staple food produced within CMA could sufficiently meet the consumption demands of the region according to the yield and population data in 2019 (General Office of the State Council, 2014). The production of vegetables, meat and eggs is also either completely or almost sufficient to cover the local needs. However, a gap of self-provision was observed in the total grain production, suggesting the high dependence of imported grain to cover grain use of all purposes locally (Fig. 6 ). Main agricultural products in CMA include grain, vegetables, pigs, tea, fruits, bamboo and Chinese medicinal herbs, contributing a significant portion of total yield in Sichuan province. Advantages in producing various agricultural products were observed among the four cities in CMA, based on which planning of relevant agri-food industries can be conducted for better resource allocation, spatial arrangement and synergistic development (Fig. 7 ). Generally, small-scale food production and processing systems with a low level of standardization, mechanization and digitalization are still common in the local food supply, which limits the overall supply capacities of CRFS in CMA. Additionally, it was pointed out that homogeneous competition among similar agri-food industries is a frequent issue within CMA. Better regional planning to guide differentiated industry development that serves HQD goals is necessary for CMA's CRFS. For the food supply chains and consumption, distribution and market systems comprising three levels of wholesale markets and three main retailing outlet types have been developed and improved through development plans in past decades. Specifically, the wholesale markets include regional integrated markets, district- or county-level markets and specialized local food markets, and the retailing outlets include farmer markets, food supermarkets and neighborhood grocery stores. The Mengyang wholesale market located in Chengdu serves as a regional food distribution hub in Sichuan Province, with 6.8 million tonnes of food products distributed in 2020, playing pivotal roles in consumers' food access. A trend of increasing online food purchase has been observed among consumers, which provides more possibility on food diversity and affordability. A metropolitan emergency food supply system is also under development based on collaboration of four large-scale wholesale markets located in the four cities of CMA respectively, expected to greatly contribute to the food system resilience in CMA especially under shocks and stresses.

Fig. 6.

A comparison between production capacities and consumption demands of the main agricultural products in CMA. The orange bar represents the annual yield of the main agricultural products and the grey bar represents the quantity of estimated consumption demands according to the total population and recommended food consumption amount per capita according to the national guideline for food and nutrition. On a particular note, “grain” refers to total production of grain crops, while “staple food” refers to the grain which are supplied for human consumption. Data is sourced from the Statistics Yearbook of 2019.

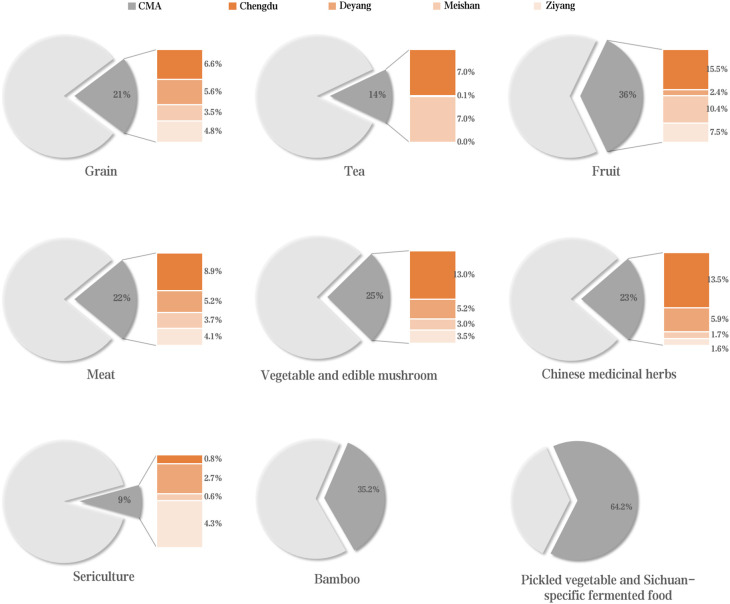

Fig. 7.

Yield proportion of main agricultural products in CMA cities respectively in 2018. The pie charts in light grey and dark grey illustrate the proportion of the production in CMA as compared to the total production in Sichuan province. The column charts in orange illustrate the proportion of the production in respective cities as compared to the total production in CMA. Data of individual cities for bamboo and pickled vegetable was missing. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.3.2. Good governance

With respect to governance, in addition to the provincial strategies in improving coordination mechanisms among the four cities of CMA, a number of counties and cities in CMA are designated by the national government as pilot and demonstration areas for institutional innovations in integrated urban-rural development, urban-rural coordination support, rural collective property rights, rural collective assets and share, and reforms of rural areas. In Chengdu, Urban Agriculture Functional Zones was an innovative invention, where factors of production for specific industries are gathered in the designated zones to maximize the synergies among sectors and stakeholders and lead to differentiated high-quality development effectively (Wang et al., 2021). Overall, progresses are continuously observed upon the newly emerging governance systems, although proved approaches to better coordinate and achieve win-win outcomes across CMA are still under exploration to be widely implemented.

3.3.3. Environmental integrity

The new urban development paradigm that emphasizes the “people-city-environment-industry” integration has presented both higher requirements and more opportunities for CRFS transformation towards ecosystem serving, carbon neutral, resource recycling and fine views of food production areas that better entertains city consumers. A trend from traditional agriculture to ecological agriculture has been observed in many production and processing spots of CMA. The Qianfeng Tea Theme Demonstration Park in Meishan is a typical example of organic production and resource cycling (Fig. 8A). The park has a pig farm of 53 mu in intelligently controlled environment and a tea farm embedded with experiencing and educational elements for consumers. The manure from the pig farm is collected, treated and supplied to the tea farm as organic fertilizers through a network of irrigation pipes. The tea farm strictly follows the standard in zero use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. The park holds multiple organic certificates and mainly supplies to the healthy food industry. In Deyang, the demonstration base of integrated rice-shrimp farming also applies ecological approaches for healthy and green food supply (Fig. 8B). Of a year, the farm usually grows one season of rice, raises two seasons of shrimp and leaves one season for fallow. Green cultivation technologies are utilized along the whole cycle. The total annual incomes of shrimp seeds, shrimps and rice could reach 10,000 yuan per mu. There are a variety of similar cases in CMA, while information regarding food loss and waste and greenhouse gas emission still remains further investigations.

Fig. 8.

Photos taken during the field survey in CMA to illustrate the case of the Qianfeng Tea Theme Demonstration Park (A), the integrated rice-shrimp farming demonstration base (B), the Hao Wei Dao Specialized Rice Cooperative (C) and the China Paocai museum (D).

3.3.4. Social wellbeing

For improving rural livelihood and strengthening urban-rural linkages, increasing local practices and governmental support for integrating the agriculture industry with the secondary and tertiary industries have been observed in CMA. Being the origin area of agritourism in China, CMA has good foundation in leisure agriculture and rural tourism. In 2019, the total number of rural tourists was 187.53 million in CMA versus 369 million in Sichuan province. The total income of rural tourism was 118.9 billion yuan in CMA versus 296.7 billion yuan in Sichuan province. An estimated total of 82,400 households in CMA were involved in rural tourism businesses to diversify their income sources. Another typical practice to improve incomes is the organization of cooperatives that collectively manage production, processing, marketing and capacity building activities taking advantages of the scale merit. A representative case is the Hao Wei Dao Specialized Rice Cooperative possessing 355 members and a total of more than 41,000 mu of transferred land (Fig. 8C). On the production side, the cooperative conducts recycling agriculture and collaborates with local research institutions to improve rice yield and quality. It also provides agricultural input supply and mechanization services for more than ten thousands of households in the neighborhood, reaching hundred thousands of people. For marketing of the rice products, the cooperative employs sales teams and sells through both online and offline channels. The sales profit is then divided to cooperative members.

3.3.5. Cultural preservation

There are a number of industries in CMA featuring characteristic agri-food culture with high value to be explored and disseminated, such as sericulture, bamboo, pickled vegetables, rattan pepper, Chinese medicinal herbs etc. So far there are 36 agricultural product Geographical Indications in CMA out of 191 in Sichuan province (n.d., 2021). Practices to upgrade and develop these industries have been observed to disseminate local culture and increase the wider influence of the local food products. For example, building on the rich culture of the Silk Road and good basis Ziyang has in the sericulture industry, the city's plan to establish “City of Mulberry” is expected to further upgrade the entire industry and increase the international influence of local brands. The pickled vegetable processing is also a traditional industry in Sichuan province. Out of the 4 million tons of pickled vegetables and Sichuan-specific fermented food produced in Sichuan province, CMA's production occupied 64.2 % of the total amount (Fig. 7). In Meishan, the China Paocai (pickled vegetables) City, a museum of Paocai was started in 2012 to elaborate and disseminate the culture and industry of Paocai, receiving 1 billion person-time visits per year (Fig. 8D). The Pickle Food International Expo has been held for eleven years continuously in Meishan, gaining a worldwide reputation for the city's culture of food. Meishan has offered a representative example in which the agri-food industry's culture is well preserved while scale-up of the industry and local brands are also achieved by taking advantage of the cultural values.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Findings and reflections

The study has presented the first attempt in China that applied the City Region Food System approach to evaluate the city's food related activities, actors and impacts from a holistic view. A key principle to ensure practical implementation of the food systems approach is to precisely map the local needs so that the support for local planning and practices will be conducted accordingly. Hence, three actions were taken in the present study to set robust foundation for the next-step in-depth assessments and evidence-based food planning.

The multi-level policy analysis was conducted first to understand the overall development direction and prioritized needs in the pilot area in China (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). It was found that under the overarching framework of high-quality development, the rural revitalization, new urbanization development and integrated urban-rural development are main pillars of top priorities for the current stage. The CRFS, a pivotal component for above, was conceptualized under the HQD framework into five main sections including governance, economy, environment, culture and society, with prioritized objectives in each section identified according to plans and policies across multiple administrative levels (Fig. 3). Targeting the CRFS goals specific to Chengdu and its surrounding areas, an adaptable indicator framework for in-depth CRFS assessment was developed, covering the five CRFS sections and sorted along the agri-food chain (Fig. 4). A range of existing food system frameworks piloted elsewhere globally were consulted, which verified the rationality and inclusion of the indicator framework. However, given that the framework developed in the present study is the first-ever attempt for CRFS assessment in Chinese cities and that China is unique as compared to other countries in many aspects such as its large food security needs, transitioning development stage and governing patterns, it is necessary to monitor the suitability and feasibility of the framework and make continuous adjustments along the piloting of the assessment exercise. Sub-indicators to be selected for in-depth measurements of the CRFS performance and impacts should follow the following criteria: (1) close relevance to the section themes and indicators; (2) data availability and accessibility; (3) data comparability.

Under the framework, the rapid CRFS scan in the Chengdu Metropolitan Area has enabled preliminary understanding of the CRFS status, based on which information gaps, potential challenges and opportunities in high-quality development of CRFS in CMA were identified. By obtaining the local data mainly from statistic yearbooks, interviews of key informants and on-site observations in the field, a lack of information on the consumption side was reflected, suggesting the limited attention in food environment research and development in general. In-depth surveys to a wider respondents are required to obtain first-hand data on consumers' food access, diets, and consumption behaviors. Data on other indicators such as the food loss and waste was also found scarce, indicating the needs for more research and collaborations across sectors and stakeholders. In addition to the good practices observed in CMA that demonstrated potential options for CRFS improvement (Fig. 6), the systemic analysis of the local food systems of CMA has suggested innovative attempts in seeking food system synergies at the scale of the metropolitan area to facilitate regional high-quality development in a shared, coordinated, open, innovative and green manner. To achieve these goals, thorough analysis of strengths and weakness of different cities and counties in CMA should be carried out, which then will guide effective resource distribution and aggregation at the metropolitan level, so that the cities could better develop by maximizing the existing advantages and complementing the weaknesses. Practical coordination mechanisms should be in place to facilitate information sharing and resource flow among the four cities for a win-win situation. Large-scale demonstration bases should be established for each industry to lead good practices in CMA towards better performances in standardization, mechanization and digitization of the food supply systems. It would be challenging for cities to make cross-boundary investments by themselves. Strategic food planning and effective systems of coordination and collaboration at the CMA level are essential to make the expected metropolitan synergies real.

4.2. Policy recommendations

Based on the analysis above, key implications can be obtained and entry points of actions were identified to facilitate high-quality development of CRFS. Policy recommendations were proposed for consideration of further research and interventions for both local and international practices:

-

(1)

The digitalization of the food supply systems could bring huge values in improving the supply capacity and food system resilience (Nikola et al., 2019). Actions in this area may include the application of digital agriculture for food production, the systemization of the food flow data for supply chain management, the use of e-commerce platforms for food product consumption and ideally, the establishment of a consolidated local food system shared database for connecting all the food system stakeholders to support evidence-based decision making for all. The COVID-19 pandemic has indeed accelerated the food system digitalization which considerably supported producers with fresh food sales and guaranteed the city food supply during the lockdown situation (Fei & Ni, 2020). In a post pandemic scenario, more attention and investment are expected in this field to facilitate the modernization development and food system transformation.

-

(2)

Urban agriculture in inner city areas can be a lever for improving citizens' diets and knowledge in agriculture and food culture (Palmer et al., 2016; Veenhuizen & Danso, 2007; Fei et al., 2020), which is currently a weakness of the CRFS in most Chinese cities (Chinese Nutrition Society, 2021). School gardens and community gardens are typical urban agriculture typologies where food production activities, food education and social events will be happening. Monitoring of participants' food consumption habits and diet-related health status can be conducted to gain in-depth understanding of the food environment in cities.

-

(3)

Food loss and waste (FLW) is receiving great attention more recently, recognized as key factor in resource depletion and food security. Quantitative data of FLW is still limited in China (Cheng et al., 2017) and many areas globally. Research in measuring FLW quantity in different scenarios and evaluating intervention effects is needed to guide targeted measures in effective FLW reduction.

-

(4)

Industry integration has been increasingly practiced and proved to be helpful measures to drive the up-scaling and transformation of traditional agri-food industries, dissemination of the farming culture and income improvement in rural areas. Combination of agriculture with the secondary and tertiary industries, such as the tourism industry and the cultural and creative industry, could add new income sources for the rural population while facilitating connections and understandings between producers and consumers. Multiple values of agriculture should be studied and explored further.

4.3. Looking forward

The increasing global challenges and disasters have highlighted the vulnerability of our current food systems. The constraints in global trade during the COVID-19 further implied the significance of the local food systems in securing our food security and nutrition. For China, although huge progress has been made in the past decades to feed more than 20 % of the global population with less than 10 % of the total land area, more efforts are yet to be made to adjust the food supply structure, minimize ecological costs and improve consumers' diets for health.

“Standing on the shoulders of giants”, the present study made the first attempt to apply the food system thinking and adapt the CRFS approach in Chinese cities, aiming to develop conceptualization and assessment tools and support local food planning and high-quality development. Building on the findings and reflections from this paper, the research team will continue the study in Chengdu and CMA by undertaking in-depth assessments of all the five themes, establishing stakeholder dialogue mechanisms and formulating practical policy recommendations tailored for the region. The conceptual and assessment frameworks will be iterated along the monitoring process and a package of food planning support tools that are adaptable for other Chinese cities is expected to be developed in the end. The outcomes will enrich the food system theories and practices of food systems both in China and globally. It will be challenging to break the barriers across different sectors and territories for information sharing and autonomous coordination, and this is the value of food system approaches that worth working for, to transform the current research and development paradigm towards more inclusive, resilient and sustainable food systems in a post pandemic era.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

List of the policy documents reviewed and analyzed in the present study.

Funding

This research was jointly supported by the Local Financial Funds of National Agricultural Science and Technology Center, Chengdu (NASC2020PR02) and Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Shulang Fei: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Zhuang Qian: Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Guido Santini: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Jia Ni: Resources, Writing – review & editing. Yuanhao Bing: Investigation. Li Zhu: Investigation. Jindong Fu: Writing – review & editing. Zhuobei Li: Writing – review & editing. Nan Wang: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

Zhuang Qian is grateful for the financial support from the program of China Scholarship Council (No. 201908320418) during his PhD study.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Allen T., Prosperi P. Modeling sustainable food systems. Environmental Management. 2016;57 doi: 10.1007/s00267-016-0664-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Béné C., Prager S.D., Achicanoy H.A., Alvarez Toro P., Lamotte L., Bonilla Cedrez C., Mapes B.R. Global Food Security; 2019. Understanding food systems drivers: A critical review of the literature. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Bhunnoo R., Poppy G.M. A National Approach for transformation of the UK food system. Nature Food. 2020;1(1):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Biehl E., Buzogany S., Baja K., Neff R. Planning for a resilient urban food system: A case study from Baltimore City, Maryland. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. 2018:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- Blay-Palmer A., Santini G., Dubbeling M., Renting H., Taguchi M., Giordano T. Validating the city region food system approach: Enacting inclusive, transformational city region food systems. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018;10 Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Blay-Palmer A., Santini G., Halliday J., Veenhuizen R.V., Taguchi M. 2020. City Region Food Systems to Cope with COVID-19 and Other Pandemic Emergencies. Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Carey J., Dubbeling M. 2017. A City Region Food System Indicator Framework. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . 2006. Suggestions on Promoting the Construction of a New Socialist Countryside. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. Opinions on the supply-side structural reform in agriculture. China Agricultural University Journal of Social Sciences Edition. 2017;34(2) [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S., Bai J., Jin Z., Wang D., Liu G., Gao S., Bao J., Li X., Li R., Jiang N., Yan W., Zhang S. Reducing food loss and food waste: Some personal reflections. Journal of Natural Resources. 2017;32(4):529–538. [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Nutrition Society . Vol. 2021. 2021. Scientific Research Report of Dietary Guidelines for Chinese Residents. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . 2005. Policy suggestions for further strengthening rural work and raising comprehensive agricultural production capacity. Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . 2007. Suggestions on Actively Developing Modern Agriculture and Promoting the Construction of a New Socialist Countryside. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . 2010. Suggestions on strengthening the coordination of urban and rural development and further facilitating the Foundation of Agricultural and Rural Development. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . State Council Bulletin; Beijing, China: 2014. National new urbanization plan(2014-2020) [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . 2016. The outline for the health China 2030 initiative plan. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee and State Council . 2021. Suggestions on comprehensively promoting rural revitalization and accelerating agriculture and rural modernization. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- CPNRB . Chengdu Planning and Natural Resources Bureau; Chengdu, China: 2019. Planning for the construction of a beautiful and livable park city of Chengdu (2018–2035) [Google Scholar]

- CPNRB . Draft master plan for territorial space in Chengdu (2020-2035) 2021. Chengdu, China. [Google Scholar]

- Crippa M., Solazzo E., Guizzardi D., Monforti-Ferrario F., Tubiello F.N., Leip A. Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food. 2021;2(3):198–209. doi: 10.1038/s43016-021-00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen P.J. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Global Environmental Change. 2008;18(1):234–245. [Google Scholar]

- Fanzo J., Haddad L., Mclaren R., Marshall Q., Davis C., Herforth A., Jones A., Beal T., Tschirley D., Bellows A., Miachon L., Gu Y., Bloem M., Kapuria A. The food systems dashboard is a new tool to inform better food policy. Nature Food. 2020;1:243–246. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . FAO; Rome, Italy: 2014. SAFA sustainability assessment of food and agriculture systems guidelines version 3.0. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . FAO; Rome, Italy: 2018. Sustainable food systems: Concept and framework. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . FAO; Rome, Italy: 2020. Cities and local governments at the forefront in building inclusive and resilient food systems: Key results from the FAO survey “urban food systems and COVID-19". [Google Scholar]

- FAO . FAO; Rome, Italy: 2021. The state of food security and nutrition in the world 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, Rikolto, RUAF . FAO and Rikolto; Rome: 2022. Urban and peri-urban agriculture sourcebook – From production to food systems. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, RUAF, MUFPP . The Milan urban food policy pact monitoring framework. 2019. p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Fei S., Ni J. 2020. Local food systems and COVID-19: A look into China’s responses.http://www.fao.org/in-action/food-for-cities-programme/news/detail/en/c/1270350/ Retrieved 6/4/2021, 2021, from. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei S., Ni J., Santini G. Local food systems and COVID-19: An insight from China. Resources, Conservation & Recycling. 2020;162 doi: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Food Systems Transformation Group . Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford; 2022. Enhancing the resilience of London’s food system. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the State Council . 2014. Guidelines for Food and Nutrition Development in China (2014-2020) Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- General Office of the State Council . 2017. National nutrition plan(2017-2030) Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition . Food systems and diets: Facing the challenges of the 21st century. 2016. London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Grewal S.S., Grewal P.S. Can cities become self-reliant in food? Cities. 2012;29(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Health China Initiative Promotion Committee . National Health Commission; 2019. Action plan for the health China initiative (2019-2030) [Google Scholar]

- HLPE . 2014. Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security. Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE . 2017. Nutrition and food systems. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security. Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- HLPE . 2020. Food security and nutrition: Building a global narrative towards 2030. A report by the high level panel of experts on food security and nutrition of the committee on world food security. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain S., Vause J. TEEB for agriculture & food: Scientific and economic foundations. 2018. TEEB for agriculture & food: Background and objectives; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ingram J. A food systems approach to researching food security and its interactions with global environmental change. Food Security. 2011;3(4):417–431. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2015. A framework for assessing effects of the food system. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings S., Cottee J., Curtis T., Miller S. 2015. Food in an urbanised world: The role of CRFS in resilience and sustainable development. Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Liu T., Du S. The construction of high-quality development evaluation index system of agricultural based on new development concept. Chinese Journal of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning. 2021;42(4) [Google Scholar]

- Marion B.W. Heath and Company; Lexington, Mass, USA, D.C.: 1986. The Organization and Performance of the U.S. Food System. [Google Scholar]

- n.d. 2021. National information system for agro-product geographic indications. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) 2019. Key tasks for the new urbanization in 2019. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) 2020. Key tasks for the new urbanization and integrated urban-rural development in 2020. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) 2021. Key tasks for the new urbanization and integrated urban-rural development in 2021. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C.F., Kopainsky B., Stephens E.C., Parsons D., Jones A.D., Garrett J., Phillips E.L. Conceptual frameworks linking agriculture and food security. Nature Food. 2020;1(9):541–551. doi: 10.1038/s43016-020-00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikola M., Trendov S.V., Zeng M. 2019. Digital technologies in agriculture and rural areas. Rome, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Nourish . 2020. Food system tools: Nourish food system map. [Google Scholar]

- NPC Standing Committee . The People's Republic of China; 2021. Law on Countering Food Waste. [Google Scholar]

- NPC Standing Committee . The People's Republic of China; 2021. Law on promotion of rural revitalization. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Ministry of Finance. Office of the Ministry of Commerce . 2021. Strengthening the construction of supply chain systems of agricultural products. Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]