Abstract

Red blood cells circulating through the brain are briefly but closely apposed to the capillary endothelium. We hypothesized that this contact provides a nearly direct pathway for metabolic substrate transfer to neural cells that complements the better characterized plasma to endothelium transfer. While brain function is considered independent of normal fluctuations in blood glucose concentration, this is not borne out by persons with glucose transporter I (GLUT1) deficiency (G1D). In them, encephalopathy is often ameliorated by meal or carbohydrate administration, and this enabled us to test our hypothesis: Since red blood cells contain glucose, and since the red cells of G1D individuals are also deficient in GLUT1, replacing them with normal donor cells via exchange transfusion could augment erythrocyte to neural cell glucose transport via mass action in the setting of unaltered erythrocyte count or plasma glucose abundance. This motivated us to perform red blood cell exchange in 3 G1D persons. There were rapid, favorable and unprecedented changes in cognitive, electroencephalographic and quality-of-life measures. The hypothesized transfer mechanism was further substantiated by in vitro measurement of direct erythrocyte to endothelial cell glucose flux. The results also indicate that the adult intellect is capable of significant enhancement without deliberate practice. ClinicalTrials.gov registration: NCT04137692 https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04137692

Keywords: Glucose, flux, exchange transfusion, electroencephalography, erythrocyte

Introduction

Transfer of plasma metabolites to the brain parenchyma governs numerous well-known facets of neural activity. Transfer from red blood cells (RBC) may be considered as important but has been less studied. For example, deformed RBC in Alzheimer's disease were hypothesized to provide less oxygen to the brain, with potential consequences on cognition. 1 We utilized GLUT1 deficiency syndrome (G1D) as a disease model to investigate direct red blood cell to cerebral capillary endothelium glucose transfer. Several considerations informed our choice of this model. First, G1D is primarily an encephalopathy. 2 This is expected because brain capillary endothelium and glial cells rely almost exclusively on GLUT1 for glucose entry and exit. This encephalopathy often proves nutrient-responsive 3 and thus, perhaps, also RBC-glucose transfer responsive. Second, a similar transporter exclusivity occurs in red blood cells, where GLUT1 represents about 10% of the membrane protein. 4 In fact, G1D may be diagnosed via RBC glucose transport assay 5 and certain missense mutations lead to hemolysis due to GLUT1 transporter dysfunction. 6 Therefore, since most G1D persons harbor a normal glut1 (or slc2a1) allele and all exhibit a significant, though reduced, degree of GLUT1 activity, 7 increasing blood glucose availability could augment blood to brain transport. Clinical observations of epilepsy amelioration in G1D have supported this notion. 3 Thus, we hypothesized that this may occur not only via plasma glucose transfer but also via red cell transfer. However, two notions militate against the usefulness of this experimental context for the testing of our hypothesis: First, synaptic dysfunction in G1D mouse brain tissue persists despite elimination of the blood brain barrier, suggesting that any effects of increased blood to brain transfer may be too modest to detect in a background of blood brain barrier-independent neural dysfunction;3,8 second, the adult brain is widely assumed to be incapable of practice-independent intellectual enhancement, including the G1D brain, which may prove nonmodifiable after development. This would impose, if correct, an early age limitation to any potential effect of augmented glucose transfer. 9 Counterarguments to these contentions may be adduced based on various experimental or clinical observations but, instead, we reasoned that quantitative experimental investigation was required. Thus, we asked whether replacing G1D RBC with healthy donor RBC via exchange transfusion 10 modulated cognition and related measures such as EEG. We chose exchange over transfusion to avoid RBC or fluid overload while preserving native blood glucose levels. The hypothesis thus indirectly tested was that the short-lived but close apposition between circulating RBC and endothelium was a determinant of blood to brain glucose flux. In this context, ours was a proof of principle study that did not assess potential long-term effects after the exogenous RBC were naturally degraded and fully replaced, repetitive treatments or blinding to the RBC exchange since the procedure is by necessity apparent to the subject and impractical to compare with a control intervention. These questions could be addressed in future work if the principle was proven.

Materials and methods

Subjects and overall study design

The study followed the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 (and as revised in 1983) and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of UT Southwestern Medical Center. ClinicalTrials.gov registration was NCT04137692. Written consent was obtained from all the subjects. The G1D subjects were selected to represent potentially disparate molecular mechanisms of GLUT1 dysfunction or reduced abundance. 3 white Caucasian G1D subjects aged 28 (S1, male, harboring splice site mutation c.972 + 1G > T in intron 7, 21 (S2, female, mutation DelIIe129) and 29 years (S3, female, mutation Ser210Asn) with the common phenotype of epilepsy, ataxia, spasticity and dysarthria with infantile onset 2 and consuming a regular diet were recruited for 2 visits (3 days and 1 day, respectively) 60 days apart. c.972 + 1G > T is expected to abolish GLUT1 activity due to protein truncation, whereas DelIle129 and Ser210Asn may alter function and/or expression.

Blood typing and matching for groups ABO, Rh and Kell and quantification of blood cell count and analytes and a pregnancy test (where appropriate) were obtained. These tests except blood typing were repeated after RBC exchange, which took place on day 2. At visit 1 (on day 1), a scored physical exam was performed as previously described. 11 On days 1 and 3, the subjects and parents underwent standardized cognitive and quality of life assessments as described below. On day 2, video electroencephalography (EEG) was continuously performed from 3 1/2 hours prior to 1 hour post exchange. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound of the major cerebral vessels was performed immediately before and after exchange. On day 3, a 3 1/2-hour EEG and the neuropsychological assessments were repeated at the same time as day 1. On visit 2, all of day 1 blood (except for typing) and physical exams and all of day 3 studies were again obtained.

Assessments

Visit 1: On day 1, a scored physical exam was performed as previously described. 11 Blood typing and matching for groups ABO, Rh and Kell and quantification of blood cell count, electrolytes, AST, ALT, GGT, lactate, pyruvate, beta hydroxybutyric acid, magnesium, phosphorus, calcium, albumin, urea nitrogen, creatinine, amino acids, creatine kinase, free fatty acids, TSH, T4, lipids, and a pregnancy test (where appropriate) were obtained. These tests except blood typing were repeated after exchange, which took place on day 2.

On days 1 and 3, the subjects underwent these performance assessments: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI-II 12 ) Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT-3 13 ) Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT-5 13 ) Symbol Digit Modalities Test, Oral (SDMT 14 ) Hopkins Verbal Learning Test (HVLT-R 15 ) Connors Continuous Performance Test (CPT-3 16 ) Revised Abbreviated Finger Tapping Test; 17 Purdue Pegboard; 18 Grooved Pegboard; 19 spiral drawing; 20 line drawing and clock drawing. 21 Practice effects were minimized via alternate forms where available (EVT-3, PPVT-5, HVLT-R) and randomized presentation of stimuli (CPT-3). Of note, since PPVT-5 and EVT-3 represent alternate-form tests of vocabulary (which is generally considered stable), practice effects generally are not considered significant and no studies have reported practice effects for these measures. However, exposure to the CPT-3 task alone is likely to induce a practice effect simply because upon subsequent testing (especially when administered in rapid succession), subjects can recall the general trends and duration of the test, thus potentially facilitating their performance. One parent of each participant completed questionnaires EQ-5D-5L 1 and 2, 22 Adult Behavior Checklist, 23 and Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, third edition. 24

On day 2, video electroencephalography (EEG) was continuously performed from 3 1/2 hours prior to 1 hour post exchange. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound of the major cerebral vessels immediately before and after exchange utilized a ST3 (Spencer Technologies). On day 3, a 3 1/2-hour EEG and the neuropsychological assessments were repeated at the same time as day 1. On visit 2, all of day 1 blood (except for typing) and physical exams and all of day 3 studies were again obtained.

RBC exchange

Isovolemic hemodilution (S1 and S2) or standard RBC exchange (S3) utilized a Spectra Optia (Terumo BCT) apheresis device programmed to replace 70% of G1D subject RBC with donor RBC (utilized less than 7 days after collection) maintaining hematocrit. 10 The RBC volume to replace was estimated based on the apparent favorable effect of a meal on other G1D subjects, indicating that modest increases in glucose availability are followed by appreciable, and thus potentially measurable, benefit. 3 Greater fractional exchanges would necessitate much greater amounts of blood used since donor blood is increasingly eliminated during the course of the exchange. Calcium gluconate was intravenously administered prophylactically, with ionized calcium level verified during exchange.

RBC 3-O-methyl-D-glucose (3-OMG) and endothelium cell line 2-deoxyglucose (2DG) flux

On days 1 and 3, venous blood was collected and RBC subject to 3-OMG assay as described. 5 Donor blood was also assayed. Zero-trans uptake of 3H-3-OMG was measured. For co-incubation assays, 1.75 × 105 bEnd.3 endothelial cells (ATCC, CRL-2299) were cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were washed and incubated in lactate buffered Ringer’s solution 2 hours before uptake assay, which included [3H] 2DG (in culture medium) or 3 × 106 RBCs equilibrated with [3H] 2DG. For background, RBC were equilibrated with [3H] 2DG and treated with cytochalasin and phloretin. 2DG uptake by bEnd.3 cells was measured for 10 minutes at 4°C.

Pyruvate measurement

Washed RBCs were stored in citrate-phosphate-dextrose buffer overnight. RBC were resuspended in lactate buffered Ringer’s solution supplemented with 5 mM glucose (pH 7.25) and incubated at 37°C for 30 min, followed by placement on ice and centrifugation. Supernatant was deproteinized with a 10 kDa molecular weight cut off filter (Amicon, 501024). Pyruvate concentration was colorimetrically determined (Sigma, MAK071).

GLUT1 Western blot

RBC lysates were subjected to electrophoresis and western blot as described 25 using rabbit anti-GLUT1 (Millipore, 07-1401) and HSP90 antibodies (Cell Signaling, 4877S) and GLUT1 quantified using Image Studio Lite (Licor) and normalized to HSP90.

EEG acquisition

A Nihon Kohden digital EEG system was utilized to acquire scalp EEG recordings on day 2, whereas a XLTEK digital EEG system was used on day 60 of the study. A 10–20 and modified combinatorial nomenclature system of electrode placement referenced to the electrode Cz was used for the acquisition of continuous EEG recordings. The voltage values (in µV) thus collected were exported as European Date Format (EDF) and subsequently imported into MATLAB for spectral analysis.

Analysis of 30-min EEG segments

On day 2, two movement-artifact-free 30-minute EEG segments were chosen, one before exchange and one at the end of exchange. Similarly, a 30-minute segment was selected on day 60 of the study at the same time in the morning as the first (pre-exchange) recording. Any movement artifact (for instance, eating lunch or going to the restroom) resulted in removal of that segment before further analysis. After initial screening, data from each electrode of the 30-min segment was divided into 5-second epochs. Power spectral densities were calculated using a Fast Fourier Transform (MATLAB’s ‘fft’ function) for each epoch, for delta (<4 Hz), theta (4–7 Hz), alpha (7–14 Hz), beta (15–30 Hz), low gamma (30–50 Hz) and high gamma (70–100 Hz) frequency bands. A 60 Hz band-stop or notch IIR filter was used. The omitted spectrogram data due to the notch filter was linearly interpolated (MATLAB’s ‘fillmissing’) and Gaussian white noise was introduced in that segment (MATLAB’s ‘awgn’) for visualization purposes. Absolute power for every 5 second epoch was divided by the trapezoidal area under the spectrum, using MATLAB’s ‘trapz’ function. Average relative power was generated for all aforementioned frequency bands. Means of 5 second EEG epochs were calculated and changes in average relative frequency band power after RBC exchange on day 2 and on day 60 with respect to before exchange on day 2 were visualized using EEGLab’s ‘topoplot’ function. Because of large changes demonstrated in the topoplots and because of demonstrated neurophysiological abnormalities in the subjacent cerebral cortex of the mouse model, 8 electrode P3 was chosen for further analysis. The power from all 360 5 second epochs of electrode P3 was used to perform statistical analysis to determine effect of exchange for each subject. The mean of all 5 second epochs was generated for absolute power and relative power of all frequency bands.

Spectral peak prominence

The spectral peak prominence was extracted from the power spectral density plots. A limited frequency range for alpha spectral peak was avoided to prevent biasing against individual subjects and conditions. MATLAB’s ‘ginput’ function was utilized to mark a point before the ascent and a point after the descent of the spectral peak. A line connecting these two points was considered as baseline for calculating the spectral peak prominence. After performing baseline subtraction from the spectral peak, a smoothing filter (MATLAB’s ‘smooth’) was applied. The MATLAB’s ‘findpeaks’ operation was used to calculate the frequency, the half width and prominence (height) of the spectral peak.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using MATLAB R2021a and Graphpad Prism 9. To assess the acute changes in each patient, student’s two-sample t-test was performed for the 5 second epochs on Day 2-Pre, Day2-Post and Day-60. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

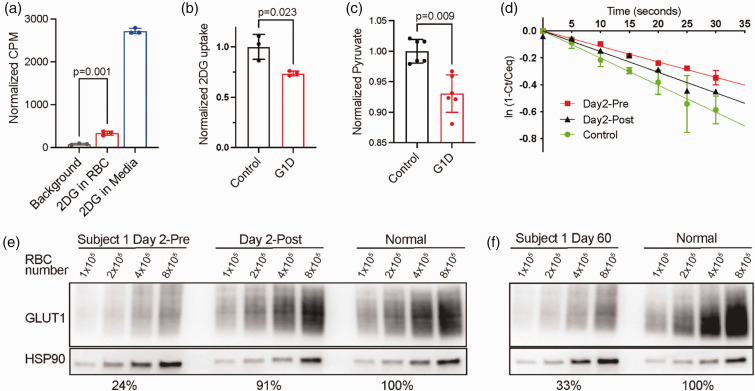

Several measurements were obtained in vitro. RBC exchange took place on day 2 of the study. On days 1 and 3, venous blood was collected and RBC subject to RBC 3-O-methyl-D-glucose (3-OMG) assay as described. 5 To determine whether normal RBC directly transfer glucose to capillary endothelium, glucose uptake was assayed in immortalized mouse brain endothelial cells (bEnd.3) exposed to human RBC containing [3H] 2DG (Figure 1(a)). This reflected RBC transport rather than RBC lysis or passive diffusion because RBC pretreatment with GLUT1 inhibitors (phloretin and cytochalasin B) abolished most [3H] 2DG uptake by the endothelial cells. G1D RBC facilitated less [3H] 2DG transport into endothelial cells (Figure 1(b)). G1D RBC also released less pyruvate than normal (Figure 1(c)). G1D RBC also exhibited reduced [3H] 3-OMG uptake (Figure 1(d)). These assays indicated that direct glucose flux from RBC to endothelium likely occurs and confirmed that G1D RBC display impaired glucose transport. 5

Figure 1.

Analysis of normal and G1D RBC. (a) 2DG uptake in cultured bEnd.3 endothelial cells. Endothelial cells show 2-DG uptake when incubated in media with 2-DG or when incubated with RBC loaded with 2-DG. Transport is minimal when RBC are loaded and then treated with transport inhibitors (phloretin and cytochalasin B) prior to incubation with bEnd.3 cells. (b) G1D subject RBC transport significantly less 2DG when co-incubated with b.End3 endothelial cells. (c) G1D subject RBC export significantly less pyruvate than normal RBC. (d) RBC 3-OMG uptake assay confirms that uptake is impaired in G1D subject 1 and that 3-OMG uptake increases after RBC exchange. (e) Representative Western blot for GLUT1 before and after RBC exchange. G1D subject 1 shows significant increase in RBC GLUT1 protein levels after exchange relative to control RBC and (f) RBC GLUT1 levels approach baseline after 60 days (at visit 2). Percentages in panels e and f indicate RBC GLUT1 abundance relative to control measured from the blots above.

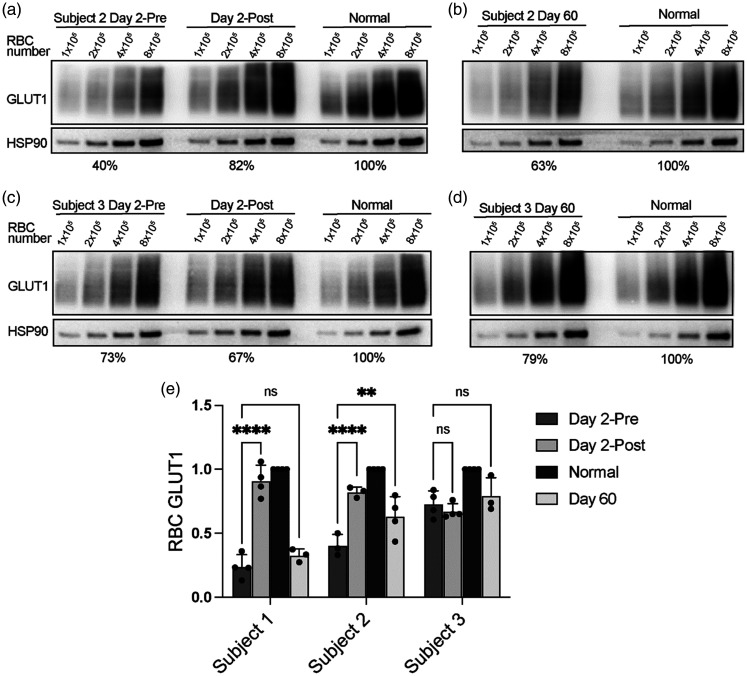

All subjects developed transient hypotension during exchange, which resolved with saline or 5% albumin infusion. Subject 3 (S3) received only 80% of the target 70% RBC exchange due to hypotension. Pre and post-exchange RBC GLUT1 levels were: Subject 1 (S1): 23.8 ± 4.7 and 90.8 ± 6.1% of control; Subject 2 (S2): 40.4 ± 5.0 and 82.2 ± 2.4%; S3: 72.8 ± 5.2 and 67.2 ± 2.9% (Figure 1(e), Table 1, Figure 2). The rate of 3-OMG uptake increased in S1 following exchange (Figure 1(d)).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and impact of red blood cell exchange on red cell parameters, EEG and neuropsychological performance.

| Subject | S1 | S2 | S3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLC2A1 mutation | c.972 + 1G > T (intron 7) | p.Ile129delc.385_387del(exon 4) | p.Ser210Asnc.627G > A(exon 5) |

| Exchange method and extent (% of RBC) | Isovolemic hemodilution (70%) | Isovolemic hemodilution (70%) | Standard exchange (56%) |

| RBC characteristics | |||

| Day 2-Pre | |||

| Hgb/HCT | 12.6/39.5 | 13.6/40.8 | 12.5/37.6 |

| MCV | 83.7 | 90.9 | 91.3 |

| RDW | 14.8 | 12.4 | 12.3 |

| Day 2-Post | |||

| Hgb/HCT | 14.1/42.4 | 13.7/42.3 | 11.2/32.9 |

| MCV | 84.5 | 90.0 | 88.4 |

| RDW | 17.0 | 15.7 | 13.5 |

| GLUT1 (% of control) | |||

| Day 2-Pre | 23.8 ± 4.7 | 40.3 ± 5.0 | 72.8 ± 5.2 |

| Day 2-Post | 90.8 ± 6.1 | 82.2 ± 2.4 | 67.2 ± 2.9 |

| Day 60 | 32.6 ± 2.9 | 63.1 ± 7.8 | 79.4 ± 8.1 |

| EEG changes | |||

| Relative beta power | |||

| Day 2-Pre | 0.0105 | 0.0158 | 0.0112 |

| Day 2-Post | 0.0115 | 0.0171 | 0.0124 |

| Day 60 | 0.0089 | 0.0128 | 0.0115 |

| Spectral peak frequency (Hz) | |||

| Day 2-Pre | 9.1 | 19.4 | 9.7 |

| Day 2-Post | 9.4 | 20.0 | 10.1 |

| Day 60 | 9.1 | 13.2 | 9.6 |

| Neuropsychological changes | |||

| PPVT-5 | |||

| Day 2-Post | ++ | − | + |

| Day 60 | ++ | ND | + |

| EVT-3 | |||

| Day 2-Post | + | + | + |

| Day 60 | − | ND | + |

| CPT-3 | |||

| Day 2-Post | +++ | + | − |

| Day 60 | +++ | ND | − |

| EQ-5D | |||

| Day 2-Post | +/− | +/− | − |

| Day 60 | + | ND | +/− |

ND: not completed in S3; +: improvement relative to pre-exchange below 1 SD; −: no significant improvement; +/−: marginal improvement; ++: improvement relative to pre-exchange great than 1 SD; +++: improvement greater than 2 SD.

Figure 2.

RBC GLUT1 levels in G1D subjects before and after exchange. (a and b) Representative Western blot of RBC GLUT1 in S2 before and after exchange (Day 2-Pre and Day 2-Post) (A) and at 60 days (visit 2, B). (c and d) Same analysis for subject 3 immediately before and after exchange (c) and after 60 days (d) and (e) GLUT1 abundance Western blot quantitative estimation for all subjects (S1, S2 and S3). Each point indicates a separate blot obtained from a total of 2 independent blood samples.

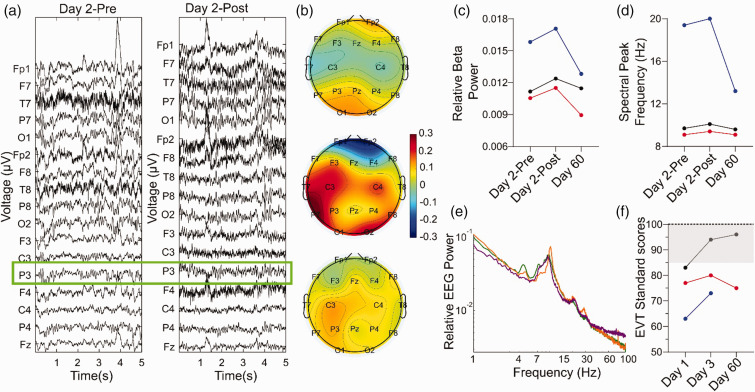

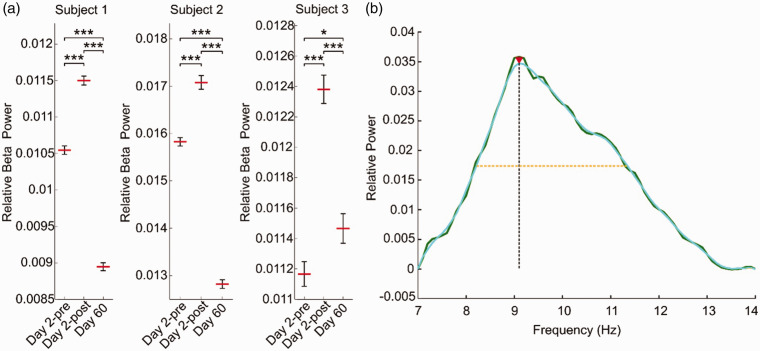

Figures 3(a) to (e) and 4 illustrate increases in EEG beta oscillation power and a shift in peak frequency relative to pre-exchange immediately after exchange, both of which partially returned to pre-treatment values at day 60. Transcranial Doppler measurements showed no clinically significant changes following exchange.

Figure 3.

EEG (a–e) and neuropsychological score changes (EVT test, f) after RBC exchange. (a) representative 5-second EEG trace from S1. The left panel (Day 2-Pre) illustrates the EEG in the morning before RBC exchange (on day 2), whereas the right panel was generated at the end of the exchange on the same day. A green rectangle highlights traces from electrode P3 (standard EEG nomenclature) which were used for the measurements in c and d. (b) Topoplots (from S1, S2 and S3 arranged in vertical order) depicting the change in relative beta oscillation (15–30 Hz) power measured at all EEG electrodes at the end of RBC exchange compared to the EEG before exchange (presented as Day 2-Post - Day 2-Pre * 100). (c and d) Pre-Post RBC exchange values of average relative beta power and spectral peak frequency measured at the P3 electrode for three conditions: before RBC exchange on day 2 (Day 2-Pre), at the end of RBC exchange on day 2 (Day 2-Post) and on day 60 of the study. Values for subjects S1, S2 and S3 are depicted in red, blue and black, respectively. (e) Representative power spectral density recorded at the P3 electrode of one subject, with Day 2-Pre (green), Day 2-Post (orange) and Day 60 (purple) represented as colored spectra and (f) Standard scores of Expressive Vocabulary Test (EVT) conducted on Day 1, Day 3 and Day 60. Normative scores in healthy subjects span from 85 to 115 with a SD of 15. The gray area indicates the lower half of these normal scores (85 to 100) and the dotted line the average of normal (100).

Figure 4.

(a) EEG changes reflected in relative beta power for 5 second epochs for each subject. Student’s 2-sample t-test with α = 0.05 (*, ** and *** indicate p ≤ 0.05, p ≤ 0.01 and p ≤ 0.001, respectively) and (b) Example of the computation of peak spectral prominence in S1. The baseline-subtracted signal (as described in the methods) is illustrated with green, whereas the smoothed spectra (moving average using MATLAB’s ‘smooth’) is displayed in cyan onto which the maximum peak is marked with an red arrowhead. The frequency corresponding to this maximum peak is extracted as spectral peak frequency (Hz). Half-width and peak prominence (height) are demonstrated by yellow and black dotted lines, respectively.

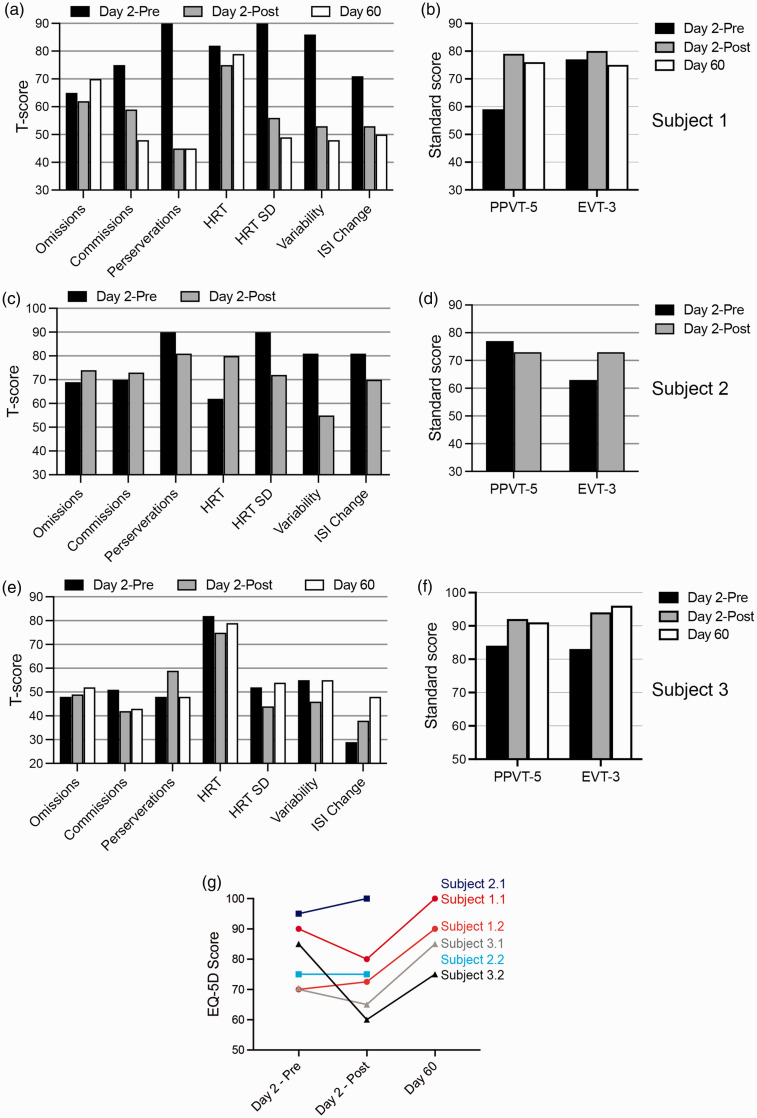

Figure 3(f) represents expressive vocabulary scores, a cardinal deficit in G1D 2,9 as part of neuropsychological testing, which is fully presented in Figure 5. In tests of sustained attention (CPT-3; see Methods for descriptions of tests and questionnaires), S1 and S2 exhibited gains on several variables on visit 1 day 3 (post-exchange). S1 showed marked increase in the consistency of reaction times (4 SD above normative mean, reaching normal values), lower rates of commission errors (2.5 SD above the mean, reaching normal), decreased impulsive responding (4 SD above mean, reaching normal), and increased sustained attention at longer inter-stimulus intervals (2 SD above mean, reaching normal). In all, his scores on 9 out of 10 CPT-3 measures improved, exceeding any expected impact of practice (Figure 5(a)). S2 also demonstrated improvements in reaction time variability and more modest improvements (Figure 5(c) and (d)). S3, whose CPT-3 scores were in the normal range before the study, did not show marked changes (Figure 5(e) and (f)) except for expressive vocabulary (EVT-3 test), which modestly improved for all subjects (Figure 5(b), (d) and (f)). While receptive vocabulary showed only slight changes for S2 and S3, S1’s scores increased by one SD, rising from moderately deficient to borderline (Figure 5(b)). None of these changes are normally expected in G1D subjects regardless of treatment, since rapid cognitive amelioration is not part of the G1D natural history (JMP, personal observation of n = 175 G1D subjects and 2 )

Figure 5.

Neuropsychological testing scores for all the subjects before and after RBC exchange and at 60 days post exchange (a–f). Subject 2 could not be tested at day 60 due to an unrelated illness. T-scores are represented with a mean of 50 and a SD of 10. Standard scores are indicated with a mean of 100 and a SD of 15. (g) Quality of life EQ-5D scores for each subject as rated by one accompanying parent who separately evaluated each corresponding subject and answered two EQ-5Q questionnaires (i.e., one, how the parent would rate the subject’s health (1.2., 2.2, 3.2) and, two, how the subject would rate his or her own health if the subject could communicate it (1.1., 2.1, 3.1)).

After 60 days (visit 2), S1 and S2 RBC GLUT1 had decreased but remained greater than pre-exchange (Table 1, Figures 1(f) and 2(b) and (d)). Only S1 and S3 completed neuropsychological testing on visit 2, as an intercurrent illness prevented this for S2. Gains in receptive vocabulary were maintained for the tested subjects (Figure 5). S1 also retained improvements in most variables of sustained attention, including consistency of reaction times, commission errors, impulsive responding, perseverations, and sustained attention at longer inter-stimulus intervals.

Caregivers evaluated overall health (EQ:5D-5L questionnaire) in visits 1 pre- and post-exchange and in visit 2. Immediately after exchange, most ratings were worse, likely reflecting the rigors of exchange and testing, which also suggests that any favorable placebo effects were overshadowed by the treatment. However, most ratings improved subsequently (Figure 5). Subjects and parents also noted strikingly improved reasoning and dexterity as reflected in the time spent eating meals starting the day following the treatment.

Discussion

Overall, this study describes RBC exchange effects for neural performance in G1D and provides a biochemical rationale for these effects. Subjects harboring mutations with divergent presumed molecular repercussions were studied. Exchange transfusion was associated with RBC GLUT1 augmentation in the absence of significant cell count or glucose concentration changes and with improvements in all subjects to varying degrees, including neuropsychological performance and quality of life. These changes were consistent with EEG findings, in other studies, of increased alertness and visual performance (increased beta power), 26 and enhanced cognitive performance (shifted or increased peak prominence frequency). 27

The reason for the different EEG spectral peak frequency of S2 at baseline is unknown since there was no obvious correlate with disease manifestations. Of note, EEG voltage amplitude and its associated absolute EEG power vary substantially in persons, both over time and over the different degrees of a person’s engagement with the environment. In contrast, relative EEG power mitigates this variability by normalizing power at every EEG oscillation frequency to the total EEG power. This facilitates the detection of frequency-specific changes. Nevertheless, attentional and maturational changes influence relative EEG power. For example, EEG alpha frequencies (7 to 15 Hz) are relevant to cognitive function during quiet wakefulness. Peak (or maximum power) alpha frequency increases during normal brain development,28,29 and is correlated with maturing cognition 30 and can be altered in neurodevelopmental disorders. 31 Thus, although the source of the difference in baseline spectral peak for S2 relative to the other subjects cannot be definitely determined, possibilities include: a) differences in brain development due to the disease, b) different cognitive engagement capacity, or c) an unknown feature of cerebral EEG activity variable across G1D subjects. The relatively greater decrease of peak spectral frequency on day 60 for S2 was unexpected and suggests a disproportionate impact of the natural loss of the infused normal RBC on brain activity. This indicates that the modulation of brain function in these patients may be heterogeneous across G1D subjects. Future studies that include serial EEGs beyond the life cycle of infused RBCs should be informative in this regard.

Greater fractions of RBC exchanged may prove more effective, but at the expense of much greater donor RBC volumes. For this study we reasoned that, if our initial hypothesis was correct, the extent of RBC exchange that we performed could be expected a priori to impact brain metabolism because only modest blood glucose increases such as those experienced postprandially are beneficial to G1D subjects. This is in fact a diagnostic disease feature noted in clinical reports.3,32–35 For example, assuming 50% GLUT1 activity in patient RBC,5,7,34 replacing 70% of these RBC with donor RBC (as in this study) will increase subject RBC GLUT1 activity by 70% (since, following exchange, 70% of RBC are donor cells expressing 100% GLUT1, and 30% are residual G1D subject RBC with 50% GLUT1), and this will raise total GLUT1 activity in G1D subject RBC from the original 50% to 85% of normal. How relevant is this increase? In G1D, after an oral glucose load (maximum 75 g), serial blood glucose increases over baseline by less than 57% over 120 min are associated with normalization of the EEG and motor and cognitive improvement. 34 Notably, in large human blood vessels, which do not participate in blood to brain exchange, only 40% of glucose resides in RBC, where 60% is plasmatic. 4 This RBC glucose compartment will receive the estimated extra 70% GLUT1 transporter, but its contribution to brain function is amplified in capillaries relative to large vessels since they contain a relatively greater RBC compartment.4,36

Several longstanding observations provide a broader context to the new therapeutic possibility described here and thus merit future consideration: 1) Man is the appropriate experimental subject because, although all fetal vertebrate RBC express GLUT1, only primates maintain high expression after birth. 37 2) Intracellular RBC glucose concentration reaches 90% of plasma glucose 38 or 40% of total blood glucose, thus constituting a considerable supply with direct brain transfer potential.4,39 3) Because GLUT1 activity depends on the structural transitions of separate protein domains, 7 some Glut1 mutations may impact selective aspects of transporter function. For example, asymmetrically reduced efflux relative to influx, as can sometimes be observed, 40 would alter the magnitude of flux restriction that each consecutive RBC and endothelial barrier presents to glucose, potentially determining overall flux and thus RBC exchange effects. 4) Exchange effects may decay following donor RBC normal degradation over time or persist if plastic change occurs in the brain.

Further research will address extent of RBC exchange response. One possibility is that glucose flux-independent process(es) may underlie unmodifiable manifestations. Research is also needed in light of the hypotension noted, particularly since neurological diseases are associated with more frequent exchange complications. 41 Another avenue for investigation may be the permanent ex vivo rectification of suitable glut1 mutations in autologous myeloid cells followed by reinfusion in the myelosuppressed subject.

The results challenge the convention that the brain is immutable after development concludes. Specifically, we find that rapid gains are possible and that some of them may persist beyond glucose flux augmentation. They also suggest that G1D brain metabolism has become dependent on glucose mass action from blood to brain. This contrasts with normal subjects, in whom hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia may be unnoticed. 42 In this context, and based in part in mouse model studies, we postulated that reduced brain glycogen renders the G1D brain susceptible to normal fluctuations in blood glucose levels. 3

Our study also suggests that RBC can directly transfer glucose and modulate brain function. RBC also carry other substrates, including pyruvate, whose efflux is reduced in G1D. Thus, future work will determine whether additional RBC metabolites support brain function or contribute to disease, particularly since increased RBC mean corpuscular volume is related to cognition in adults. 43

Abnormal RBC GLUT1 levels have been noted in diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease.44,45 In diabetes, cognitive deficits and fMRI abnormalities ensue even under mild hypoglycemia 46 without changes in blood-brain barrier transport, 47 which we postulate may be due to reduced RBC glucose transfer.

In conclusion, our findings further substantiate the participation of RBC in brain function and suggest a novel therapy for G1D.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X221146121 for Red blood cells as glucose carriers to the human brain: Modulation of cerebral activity by erythrocyte exchange transfusion in Glut1 deficiency (G1D) by Richard C Wang, Eunice E Lee, Nicole De Simone, Gauri Kathote, Sharon Primeaux, Adrian Avila, Dong-Min Yu, Mark Johnson, Levi B Good, Vikram Jakkamsetti, Ravi Sarode, Alice Ann Holland and Juan M Pascual in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We thank the G1D participants and their families for their participation.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by an unrestricted gift from the Glut1 Deficiency Foundation (JMP) and by UT Southwestern Medical Center (JMP) and NIH grant AR072655 (RCW).

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions: RCW, NDS, RS, AAH, JMP designed the study and developed the protocol; NDS, SP, AA, AAH, JMP investigated the patients; RCW, NDS, JMP supervised and managed the data generation. JMP determined eligibility and performed the physical exams. RCW, EEL, D-MY performed red blood and endothelial cell analyses. NDS and RS designed and supervised red blood cell exchange. MJ evaluated transcranial Doppler data. GK analyzed EEG data with the participation of LBG, VJ and JMP. AAH performed neuropsychological testing and quality of life assessments. RW, JMP supervised the overall data analysis and integration. All authors contributed to the analysis and interpretation of the data and reviewed all drafts of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding authors.

ORCID iD

Juan M Pascual https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0843-8221

References

- 1.Mohanty JG, Eckley DM, Williamson JD, et al. Do red blood cell-beta-amyloid interactions alter oxygen delivery in Alzheimer's disease? Adv Exp Med Biol 2008; 614: 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pascual JM, Ronen GM. Glucose transporter type I deficiency (G1D) at 25 (1990-2015): presumptions, facts, and the lives of persons with this rare disease. Pediatr Neurol 2015; 53: 379–393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajasekaran K, Ma Q, Good LB, et al. Metabolic modulation of synaptic failure and thalamocortical hypersynchronization with preserved consciousness in Glut1 deficiency. Sci Transl Med 2022; 14: eabn2956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacquez JA. Red blood cell as glucose carrier: significance for placental and cerebral glucose transfer. Am J Physiol 1984; 246: R289–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klepper J, Garcia-Alvarez M, O'Driscoll KR, et al. Erythrocyte 3-O-methyl-D-glucose uptake assay for diagnosis of glucose-transporter-protein syndrome. J Clin Lab Anal 1999; 13: 116–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flatt JF, Guizouarn H, Burton NM, et al. Stomatin-deficient cryohydrocytosis results from mutations in SLC2A1: a novel form of GLUT1 deficiency syndrome. Blood 2011; 118: 5267–5277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pascual JM, Wang D, Yang R, et al. Structural signatures and membrane helix 4 in GLUT1: inferences from human blood-brain glucose transport mutants. J Biol Chem 2008; 283: 16732–16742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marin-Valencia I, Good LB, Ma Q, et al. Glut1 deficiency (G1D): epilepsy and metabolic dysfunction in a mouse model of the most common human phenotype. Neurobiol Dis 2012; 48: 92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hao J, Kelly DI, Su J, et al. Clinical aspects of glucose transporter type 1 deficiency: information from a global registry. JAMA Neurol 2017; 74: 727–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarode R, Matevosyan K, Rogers ZR, et al. Advantages of isovolemic hemodilution-red cell exchange therapy to prevent recurrent stroke in sickle cell anemia patients. J Clin Apher 2011; 26: 200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pascual JM, Liu P, Mao D, et al. Triheptanoin for glucose transporter type I deficiency (G1D): modulation of human ictogenesis, cerebral metabolic rate, and cognitive indices by a food supplement. JAMA Neurol 2014; 71: 1255–1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryan JJ, Kreiner DS, Teichner G, et al. Validity of the Wechsler abbreviated scale of intelligence, second edition (WASI-II) as an indicator of neurological disease/injury: a pilot study. Brain Inj 2021; 35: 1624–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Axelrad ME, Nicholson L, Stabley DL, et al. Longitudinal assessment of cognitive characteristics in Costello syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2007; 143A: 3185–3193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaywant A, Barredo J, Ahern DC, et al. Neuropsychological assessment without upper limb involvement: a systematic review of oral versions of the trail making test and symbol-digit modalities test. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2018; 28: 1055–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao Z, Bu Y, Li M, et al. Remote ischemic conditioning improves cognition in patients with subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. BMC Neurol 2019; 19: 206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsai LP, Wang SS, Chee SY, et al. Dynamic changes in the quantitative electroencephalographic spectrum during attention tasks in patients with Prader-Willi syndrome. Front Genet 2022; 13: 763244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piccolino A. Cross-validation and initial investigation of two abbreviated methods of the finger tapping test. Appl Neuropsychol Adult 2021; 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinkle JT, Pontone GM. Psychomotor processing and functional decline in Parkinson's disease predicted by the Purdue Pegboard Test. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2021; 36: 909–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bezdicek O, Nikolai T, Hoskovcova M, et al. Grooved pegboard predicates more of cognitive than motor involvement in Parkinson's disease. Assessment 2014; 21: 723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banaszkiewicz K, Rudzińska M, Bukowczan S, et al. Spiral drawing time as a measure of bradykinesia. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2009; 43: 16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim S, Jahng S, Yu KH, et al. Usefulness of the clock drawing test as a cognitive screening instrument for mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: an evaluation using three scoring systems. Dement Neurocogn Disord 2018; 17: 100–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng X, Sui M, Liu B, et al. Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L and EQ-5D-3L in six commonly diagnosed cancers. Patient 2021; 14: 209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinoo C, de Lange IM, Westers P, et al. Behavior problems and health-related quality of life in Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy Behav 2019; 90: 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saleem M, Beail N, Roache S. Relationship between the vineland adaptive behaviour scales and the Wechsler adult intelligence scale IV in adults with intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res 2019; 63: 1158–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee EE, Ma J, Sacharidou A, et al. A protein kinase C phosphorylation motif in GLUT1 affects glucose transport and is mutated in GLUT1 deficiency syndrome. Mol Cell 2015; 58: 845–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamiński J, Brzezicka A, Gola M, et al. Beta band oscillations engagement in human alertness process. Int J Psychophysiol 2012; 85: 125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klimesch W, Doppelmayr M, Schimke H, et al. Alpha frequency, reaction time, and the speed of processing information. J Clin Neurophysiol 1996; 13: 511–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Somsen RJ, van't Klooster BJ, van der Molen MW, et al. Growth spurts in brain maturation during middle childhood as indexed by EEG power spectra. Biol Psychol 1997; 44: 187–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chiang AK, Rennie CJ, Robinson PA, et al. Age trends and sex differences of alpha rhythms including split alpha peaks. Clin Neurophysiol 2011; 122: 1505–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richard Clark C, Veltmeyer MD, Hamilton RJ, et al. Spontaneous alpha peak frequency predicts working memory performance across the age span. Int J Psychophysiol 2004; 53: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dickinson A, DiStefano C, Senturk D, et al. Peak alpha frequency is a neural marker of cognitive function across the autism spectrum. Eur J Neurosci 2018; 47: 643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Moers A, Brockmann K, Wang D, et al. EEG features of glut-1 deficiency syndrome. Epilepsia 2002; 43: 941–945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parolin G, Drigo P, Toldo I, et al. Pre- and postprandial electroencephalography in glucose transporter type 1 deficiency syndrome: an illustrative case to discuss the concept of carbohydrate responsiveness. J Child Neurol 2011; 26: 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akman CI, Engelstad K, Hinton VJ, et al. Acute hyperglycemia produces transient improvement in glucose transporter type 1 deficiency. Ann Neurol 2010; 67: 31–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koy A, Assmann B, Klepper J, et al. Glucose transporter type 1 deficiency syndrome with carbohydrate-responsive symptoms but without epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2011; 53: 1154–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cornford EM, Hyman S, Swartz BE. The human brain GLUT1 glucose transporter: ultrastructural localization to the blood-brain barrier endothelia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1994; 14: 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Widdas WF. Hexose permeability of foetal erythrocytes. J Physiol 1955; 127: 318–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khera PK, Joiner CH, Carruthers A, et al. Evidence for interindividual heterogeneity in the glucose gradient across the human red blood cell membrane and its relationship to hemoglobin glycation. Diabetes 2008; 57: 2445–2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widdas W. The asymmetry of the hexose transfer system in the human red cell membrane. Current Topics in Membranes and Transport 1980; 14: 165–223. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang D, Yang H, Shi L, et al. Functional studies of the T295M mutation causing Glut1 deficiency: glucose efflux preferentially affected by T295M. Pediatr Res 2008; 64: 538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLeod BC, Sniecinski I, Ciavarella D, et al. Frequency of immediate adverse effects associated with therapeutic apheresis. Transfusion 1999; 39: 282–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Monnier LO, Owens D, Colette C, et al. Glycaemic variabilities: key questions in pursuit of clarity. Diabetes Metab 2021; 47: 101283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gamaldo AA, Ferrucci L, Rifkind J, et al. Relationship between mean corpuscular volume and cognitive performance in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61: 84–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garg M, Thamotharan M, Becker DJ, et al. Adolescents with clinical type 1 diabetes display reduced red blood cell glucose transporter isoform 1 (GLUT1). Pediatr Diabetes 2014; 15: 511–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Varady G, Szabo E, Feher A, et al. Alterations of membrane protein expression in red blood cells of Alzheimer's disease patients. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2015; 1: 334–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hwang JJ, Parikh L, Lacadie C, et al. Hypoglycemia unawareness in type 1 diabetes suppresses brain responses to hypoglycemia. J Clin Invest 2018; 128: 1485–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fanelli CG, Dence CS, Markham J, et al. Blood-to-brain glucose transport and cerebral glucose metabolism are not reduced in poorly controlled type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 1998; 47: 1444–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X221146121 for Red blood cells as glucose carriers to the human brain: Modulation of cerebral activity by erythrocyte exchange transfusion in Glut1 deficiency (G1D) by Richard C Wang, Eunice E Lee, Nicole De Simone, Gauri Kathote, Sharon Primeaux, Adrian Avila, Dong-Min Yu, Mark Johnson, Levi B Good, Vikram Jakkamsetti, Ravi Sarode, Alice Ann Holland and Juan M Pascual in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding authors.