Key Points

Question

Does cumulative risk of screen-detected ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) vary according to mammography screening interval and clinical risk factors?

Findings

For this cohort study, a well-calibrated model was developed to predict cumulative 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS in 916 931 women. Compared with women undergoing biennial mammography, those undergoing annual mammography had a 40% to 45% higher 6-year cumulative risk of screen-detected DCIS, whereas those undergoing triennial mammography had lower risk.

Meaning

This risk model provides estimates of the 6-year probability of screen-detected DCIS and can inform discussions of screening benefits and harms for those considering a screening interval other than biennial.

This cohort study of US women aged 40 to 74 years undergoing mammography screening uses a risk prediction model to determine the cumulative 6-year risk of screen-detected ductal carcinoma in situ.

Abstract

Importance

Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) by mammography screening is a controversial outcome with potential benefits and harms. The association of mammography screening interval and woman’s risk factors with the likelihood of DCIS detection after multiple screening rounds is poorly understood.

Objective

To develop a 6-year risk prediction model for screen-detected DCIS according to mammography screening interval and women’s risk factors.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium cohort study assessed women aged 40 to 74 years undergoing mammography screening (digital mammography or digital breast tomosynthesis) from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2020, at breast imaging facilities within 6 geographically diverse registries of the consortium. Data were analyzed between February and June 2022.

Exposures

Screening interval (annual, biennial, or triennial), age, menopausal status, race and ethnicity, family history of breast cancer, benign breast biopsy history, breast density, body mass index, age at first birth, and false-positive mammography history.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Screen-detected DCIS defined as a DCIS diagnosis within 12 months after a positive screening mammography result, with no concurrent invasive disease.

Results

A total of 916 931 women (median [IQR] age at baseline, 54 [46-62] years; 12% Asian, 9% Black, 5% Hispanic/Latina, 69% White, 2% other or multiple races, and 4% missing) met the eligibility criteria, with 3757 screen-detected DCIS diagnoses. Screening round–specific risk estimates from multivariable logistic regression were well calibrated (expected-observed ratio, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.97-1.03) with a cross-validated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.639 (95% CI, 0.630-0.648). Cumulative 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS estimated from screening round–specific risk estimates, accounting for competing risks of death and invasive cancer, varied widely by all included risk factors. Cumulative 6-year screen-detected DCIS risk increased with age and shorter screening interval. Among women aged 40 to 49 years, the mean 6-year screen-detected DCIS risk was 0.30% (IQR, 0.21%-0.37%) for annual screening, 0.21% (IQR, 0.14%-0.26%) for biennial screening, and 0.17% (IQR, 0.12%-0.22%) for triennial screening. Among women aged 70 to 74 years, the mean cumulative risks were 0.58% (IQR, 0.41%-0.69%) after 6 annual screens, 0.40% (IQR, 0.28%-0.48%) for 3 biennial screens, and 0.33% (IQR, 0.23%-0.39%) after 2 triennial screens.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, 6-year screen-detected DCIS risk was higher with annual screening compared with biennial or triennial screening intervals. Estimates from the prediction model, along with risk estimates of other screening benefits and harms, could help inform policy makers’ discussions of screening strategies.

Introduction

Detection of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a controversial outcome of mammography screening. The incidence of DCIS increased markedly in the US with the widespread adoption of screening mammography,1,2 and more than 30% of screen-detected breast cancers are DCIS.3 Because DCIS is a nonobligate precursor to invasive breast cancer, the detection and treatment of DCIS may reduce the risk of subsequent invasive disease,4,5 yet there is concern that a substantial fraction of DCIS may never lead to invasive cancer if left untreated.2,6,7 Overdiagnosis is challenging to estimate8,9 but has influenced national breast cancer screening recommendations as a potential harm of breast cancer screening.10,11

The US Preventive Services Task Force and American Cancer Society recommendations include elements of individual informed decision-making regarding breast cancer screening strategies, including whether to start screening before the age of 50 years and whether screens should be performed annually or biennially. Aggregate data on mammography screening benefits and harms7,12,13 and individual-level breast cancer risk prediction models14 are available to inform these decisions, yet few models provide individual-level predictions of mammography screening outcomes. Models were recently published for cumulative 6-year risk of advanced (prognostic stage II or higher) breast cancer and cumulative 10-year risk of a false-positive mammography result based on mammography screening frequency and readily available clinical risk factors.15,16 Prediction models for screen-detected DCIS would further inform screening decisions and guidelines.

The purpose of this study is to examine DCIS detection rates according to mammography screening interval and clinical risk factors and develop a risk prediction model to estimate the cumulative 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS. We used a 6-year horizon to enable comparison of outcomes for 6 annual, 3 biennial, and 2 triennial screening rounds.

Methods

Study Setting

For this cohort study, we used observational clinical data from 6 breast imaging registries within the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC): the Carolina Mammography Registry, the Kaiser Permanente Washington Registry, the New Hampshire Mammography Network, the Vermont Breast Cancer Surveillance System, the San Francisco Mammography Registry, and the Metropolitan Chicago Breast Cancer Registry. Each registry prospectively collects clinical data on women undergoing breast imaging from participating radiology facilities within its catchment area. The registries and a central statistical coordinating center received institutional review board approval from their respective institutions for active or passive consenting processes or a waiver of consent to enroll participants, link data, and perform analyses. Identifiable data are collected by each registry. Limited data sets (containing dates and residential zip codes but no other direct identifiers) are sent to the BCSC Statistical Coordinating Center for pooling and statistical analysis. All procedures were Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act compliant, and registries and the statistical coordinating center received a federal certificate of confidentiality for the identities of women, physicians, and facilities. The study followed Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines17 for reporting results from cohort studies and Transparent Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) reporting guidelines for development of the risk prediction model.

Study Population

Women aged 40 to 74 years undergoing mammography screening (digital mammography or digital breast tomosynthesis) from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2020, were eligible for inclusion. We excluded women with a prior history of breast cancer (invasive or DCIS), lobular carcinoma in situ, or mastectomy. Screening mammograms were identified based on the radiologist’s clinical indication for the examination. To reflect women who were routinely screened and evaluate the screening interval, we restricted the study to screening mammograms among women who underwent mammography within the prior 42 months (corresponding to the upper limit of our triennial screening interval definition). Thus, a woman’s first mammogram was not included. We also excluded mammography screening that was unilateral, was preceded by mammography within the prior 9 months, was followed by screening ultrasonography within 3 months, or occurred 12 months before or after screening magnetic resonance imaging. At least 1 year of follow-up for complete capture of cancer diagnoses was required.

Data Collection

Participating radiology facilities provide imaging modality, examination indication, breast density, and assessment data to BCSC registries using standard nomenclature from the Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS).18 Demographic and risk factor information is self-reported or extracted from electronic medical records. The BCSC registries ascertain breast cancer diagnoses and tumor characteristics by linking women to pathology databases; regional Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results programs; and state tumor registries. Deaths are obtained by linking to state death records.

Outcome and Predictor Definitions

Screen-detected DCIS was defined as a DCIS diagnosis within 12 months after a screening mammogram with a positive final assessment (BI-RADS category 3, 4, or 5), with no invasive breast cancer diagnosis.12 We evaluated rates of screen-detected DCIS in relation to mammography screening interval, mammography screening modality (digital mammography vs digital breast tomosynthesis [DBT]), and 9 clinical breast cancer risk factors: age, menopausal status, first-degree family history of breast cancer, history of benign breast biopsy, BI-RADS breast density,18 body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), age at first birth, history of false-positive screening mammography results in the previous 5 years, and race and ethnicity. Screening interval for each mammogram was defined based on the time since the woman’s prior mammogram (annual: 11-18 months; biennial: 19-30 months; and triennial: 31-42 months). Breast density is categorized by radiologists during clinical interpretation as almost entirely fatty, scattered fibroglandular densities, heterogeneously dense, or extremely dense.18 Postmenopausal women were those with both ovaries removed, in whom menstruation had stopped naturally, who were currently receiving postmenopausal hormone therapy, or who were 60 years or older. Premenopausal women were those who reported menstruating within the last 180 days, who used oral contraceptives, or who were younger than 45 years. History of benign breast biopsy was defined based on diagnoses abstracted from clinical pathology reports. We grouped prior benign diagnoses based on the highest grade as proliferative with atypia greater than proliferative without atypia greater than nonproliferative using published taxonomy19,20,21,22 or as unknown if a woman reported a prior biopsy with no available BCSC pathology result. Self-reported race and ethnicity were included as a social construct that could potentially capture differences in screen-detected DCIS risk due to social determinants of health, including inequities in access to high-quality screening and diagnostic services, and were categorized as Hispanic/Latina and for non-Hispanic/Latina as Asian, Black, White, or other or multiple races (including American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and self-reported other race).

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted between February and June 2022. The screening mammogram was the unit of analysis. We estimated absolute screen-detected DCIS risk after 1 round of screening using multivariable logistic regression, including screening interval, modality, age (linear and quadratic, centered at 55 years), calendar year of screen (linear and quadratic, centered at January 31, 2020), menopausal status, first-degree breast cancer family history, benign biopsy history, BMI (categorical), breast density, age at first live birth (categorical), prior false-positive mammography result, and race and ethnicity. Before model fitting, 20 imputed values for each missing variable were generated using multiple imputation via chained equations (eMethods and eTable 5 in Supplement 1).23 For each covariate combination, risk scores from a single screening round were estimated by averaging over the 20 risk scores estimated in fitted logistic regression models from each imputed data set. We evaluated interactions of risk factors with age, age squared, and menopausal status and retained those that were statistically significant at a 2-sided P < .05 on type 3 tests; these interactions included those between linear age and BMI, linear age and prior false-positive mammography results, and menopausal status and BMI. We also tested interactions between each risk factor and screening interval; none were significant at P < .05 and thus were not included in the model. Mammography modality (digital mammography vs DBT) was not associated with DCIS detection and was omitted from the final model. Model calibration was estimated as the ratio of expected to observed number (E/O ratio) of screen-detected DCIS, both overall and within predicted risk decile groups. Model discriminatory accuracy was summarized using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). To internally validate the model, we compared the AUC from the model fit using the full data to the AUC from a model fit using 5-fold cross-validation, and the difference between them (optimism) was 0.004. To account for this small overfitting, the AUC and 95% CI were adjusted by subtracting the optimism from the estimates obtained from the full data.

The cumulative screen-detected DCIS risks after hypothetical repeat screening patterns consisting of 6 annual, 3 biennial, or 2 triennial screens occurring at 12-, 24-, or 36-month intervals, respectively, were estimated using a discrete-time survival model based on the fitted logistic regression models for 1 round of screening while accounting for competing risks of death or invasive cancer within 1 year after annual screening, 2 years after biennial screening and 3 years after triennial screening.24 A 6-year horizon enables comparison of outcomes for 6 annual, 3 biennial, or 2 triennial screening rounds. Mean predicted 6-year cumulative risks and IQRs for different screening intervals were estimated in a standardized population; the weights of the study population were adjusted to reflect the US female population based on age, race and ethnicity, and family history of breast cancer.25,26 The cumulative 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS was categorized into 5 risk levels (high, >95th percentile; intermediate, 75th-95th percentile; average, 25th-75th percentile; low, 5th-25th percentile; and very low, ≤5th percentile) adjusted by US population weights and standardized to the same population for different screening intervals. Data were analyzed using R software, version 4.0.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) and SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Two-sided α = .05 was used to determine statistical significance. The eMethods in Supplement 1 provide additional statistical methods details.

Results

A total of 2 320 016 annual, 681 983 biennial, and 199 058 triennial mammograms in 916 931 women (median [IQR] age at baseline, 54 [46-62] years) were included, with 3757 screen-detected DCIS diagnoses. Overall, the distribution of self-reported race and ethnicity was 12% Asian, 9% Black, 5% Hispanic/Latina, 69% White, 2% other or multiple races, and 4% missing. The screening interval was shorter among women who were older, who were White, and who had a first-degree family history of breast cancer, prior benign biopsy, normal BMI, or history of false-positive mammography results (Table 1).

Table 1. Examination-Level Characteristics of Women Undergoing Screening Mammography by Screening Interval, Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, 2005-2020.

| Characteristic | No. (%) of examinationsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual (n = 2 320 016) | Biennial (n = 681 983) | Triennial (n = 199 058) | |

| Age group, y | |||

| 40-49 | 550 151 (26.4) | 163 440 (26.3) | 58 582 (31.8) |

| 50-59 | 805 860 (38.7) | 249 409 (40.1) | 74 274 (40.3) |

| 60-69 | 724 085 (34.8) | 209 137 (33.6) | 51 577 (28.0) |

| 70-74 | 239 920 (10.3) | 59 997 (8.8) | 14 625 (7.3) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 234 941 (10.5) | 108 599 (16.4) | 26 190 (13.7) |

| Black | 209 025 (9.4) | 58 158 (8.8) | 19 917 (10.4) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 109 559 (4.9) | 46 510 (7.0) | 13 130 (6.9) |

| White | 1 640 900 (73.5) | 430 314 (65.2) | 127 001 (66.4) |

| Other or multiple racesb | 38 421 (1.7) | 16 774 (2.5) | 5113 (2.7) |

| Missing | 87 170 (3.8) | 21 628 (3.2) | 7707 (3.9) |

| Menopausal status | |||

| Premenopausal | 546 510 (28.6) | 164 582 (29.2) | 57 340 (35.8) |

| Postmenopausal | 1 362 300 (71.4) | 399 380 (70.8) | 102 697 (64.2) |

| Missing | 411 206 (17.7) | 118 021 (17.3) | 39 021 (19.6) |

| First-degree family history of breast cancer | |||

| No | 1 817 368 (81.2) | 572 979 (86.4) | 167 006 (86.8) |

| Yes | 420 085 (18.8) | 89 920 (13.6) | 25 292 (13.2) |

| Missing | 82 563 (3.6) | 19 084 (2.8) | 6760 (3.4) |

| History of benign breast biopsy | |||

| None (no prior biopsy) | 1 774 790 (76.5) | 569 618 (83.5) | 168 766 (84.8) |

| Prior biopsy, benign diagnosis unknown | 326 389 (14.1) | 75 844 (11.1) | 19 774 (9.9) |

| Nonproliferative | 154 484 (6.7) | 26 709 (3.9) | 7764 (3.9) |

| Proliferative | |||

| Without atypia | 53 843 (2.3) | 8574 (1.3) | 2452 (1.2) |

| With atypia | 10 510 (0.5) | 1238 (0.2) | 302 (0.2) |

| BI-RADS breast density | |||

| Almost entirely fatty | 223 242 (10.2) | 66 257 (11.0) | 20 113 (11.1) |

| Scattered fibroglandular densities | 956 968 (43.5) | 251 662 (41.9) | 76 244 (42.2) |

| Heterogeneously dense | 846 056 (38.5) | 234 923 (39.1) | 69 648 (38.6) |

| Extremely dense | 171 555 (7.8) | 47 545 (7.9) | 14 465 (8.0) |

| Missing | 122 195 (5.3) | 81 596 (12.0) | 18 588 (9.3) |

| BMI | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 25 413 (1.6) | 8223 (1.6) | 2135 (1.5) |

| Healthy weight (18.5-24.9) | 688 504 (42.2) | 206 268 (41.1) | 53 582 (38.3) |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 474 728 (29.1) | 142 810 (28.5) | 39 749 (28.4) |

| Obesity | |||

| Grade I (30.0-34.9) | 253 933 (15.6) | 78 469 (15.6) | 23 457 (16.8) |

| Grade II/III (≥35.0) | 188 333 (11.5) | 65 716 (13.1) | 20 980 (15.0) |

| Missing | 689 105 (29.7) | 180 497 (26.5) | 59 155 (29.7) |

| Age at first live birth, y | |||

| Nulliparous | 386 859 (21.7) | 115 875 (22.5) | 31 956 (21.5) |

| <30 | 1 015 156 (57.0) | 287 575 (55.8) | 84 511 (57.0) |

| ≥30 | 379 007 (21.3) | 111 572 (21.7) | 31 859 (21.5) |

| Missing | 538 994 (23.2) | 166 961 (24.5) | 50 732 (25.5) |

| History of false-positive mammography resultsc | |||

| No | 1 806 747 (77.9) | 584 748 (85.7) | 176 064 (88.4) |

| Yes | 513 269 (22.1) | 97 235 (14.3) | 22 994 (11.6) |

Abbreviations: BI-RADS, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

Among participants with nonmissing data.

Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and self-reported other race.

False-positive screening mammography result within the previous 5 years.

In multivariable-adjusted analyses of a single screening round, DCIS detection was more likely with longer screening interval (biennial vs annual screening: odds ratio [OR], 1.43; 95% CI, 1.33-1.55; triennial vs annual screening: OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.63-2.05) (Table 2). Detection of DCIS was more common among women who had a first-degree family history of breast cancer, were nulliparous or 30 years or older at first live birth, had a prior benign breast biopsy, or reported Asian race (Table 2). Breast density was more strongly associated with DCIS detection among younger women, whereas prior false-positive mammography results were more strongly associated with DCIS detection among older women (Table 3). The positive association of BMI with DCIS detection was limited to postmenopausal women (Table 3). Detection of DCIS did not vary according to mammography modality (OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.89-1.12 for DBT vs digital mammography).

Table 2. DCIS Detection on a Single Screening Mammogram by Screening Interval and Selected Sociodemographic and Risk Factors.

| Characteristic | No. of screening mammograms | No. with screen-detected DCIS | DCIS detection rate per 1000 population | Multivariable-adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening interval | ||||

| Annual | 2 320 016 | 2474 | 1.07 | 1 [Reference] |

| Biennial | 681 983 | 948 | 1.39 | 1.43 (1.33-1.55) |

| Triennial | 199 058 | 335 | 1.68 | 1.83 (1.63-2.05) |

| First-degree family history of breast cancer | ||||

| No | 2 557 353 | 2726 | 1.07 | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 535 297 | 875 | 1.63 | 1.53 (1.42-1.65) |

| Age at first live birth, y | ||||

| Nulliparous | 534 690 | 727 | 1.36 | 1.24 (1.14-1.36) |

| <30 | 1 387 242 | 1552 | 1.12 | 1 [Reference] |

| ≥30 | 522 438 | 621 | 1.19 | 1.21 (1.11-1.33) |

| History of benign breast biopsy | ||||

| None (no prior biopsy) | 2 513 174 | 2690 | 1.07 | 1 [Reference] |

| Prior biopsy, benign diagnosis unknown | 422 007 | 633 | 1.50 | 1.26 (1.15-1.37) |

| Nonproliferative | 188 957 | 269 | 1.42 | 1.24 (1.09-1.41) |

| Proliferative | ||||

| Without atypia | 64 869 | 125 | 1.93 | 1.60 (1.33-1.92) |

| With atypia | 12 050 | 40 | 3.32 | 2.66 (1.94-3.65) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||||

| Asian | 369 730 | 555 | 1.50 | 1.37 (1.25-1.51) |

| Black | 287 100 | 362 | 1.26 | 1.04 (0.93-1.17) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 169 199 | 138 | 0.82 | 0.81 (0.68-0.96) |

| White | 2 198 215 | 2505 | 1.14 | 1 [Reference] |

| Other or multiple racesb | 60 308 | 76 | 1.26 | 1.13 (0.89-1.42) |

Abbreviation: DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ.

Based on 20 imputed data sets. The multivariable model included screening interval, age (linear and squared), examination year (linear and squared), race and ethnicity, menopausal status, first-degree family history of breast cancer, personal history of breast biopsy, breast density, body mass index, age at first live birth, false-positive screening mammography result within the previous 5 years, interaction between linear age and breast density, interaction between age and false-positive screening mammography result within the previous 5 years, and interaction between menopausal status and body mass index.

Other included American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and self-reported other race.

Table 3. DCIS Detection on a Single Screening Mammogram by Women’s Risk Factors That Interact With Age at Mammography or Menopausal Status.

| Characteristic | No. of screening mammograms | No. with screen-detected DCIS | DCIS detection rate per 1000 population | Multivariable-adjusted OR (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 40 yb | Age 50 yb | Age 60 yb | Age 70 yb | ||||

| BI-RADS breast density | |||||||

| Almost entirely fatty | 309 612 | 186 | 0.60 | 0.38 (0.23-0.64) | 0.44 (0.32-0.60) | 0.49 (0.42-0.58) | 0.56 (0.45-0.69) |

| Scattered fibroglandular densities | 1 284 874 | 1374 | 1.07 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Heterogeneously dense | 1 150 627 | 1539 | 1.34 | 1.99 (1.64-2.42) | 1.66 (1.47-1.86) | 1.38 (1.27-1.49) | 1.14 (1.01-1.29) |

| Extremely dense | 233 565 | 332 | 1.42 | 2.35 (1.79-3.08) | 1.90 (1.61-2.24) | 1.53 (1.31-1.79) | 1.24 (0.96-1.60) |

| History of false-positive mammography resultsc | |||||||

| No | 2 567 559 | 2804 | 1.09 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Yes | 633 498 | 953 | 1.50 | 1.08 (0.91-1.29) | 1.23 (1.11-1.36) | 1.39 (1.29-1.50) | 1.58 (1.40-1.78) |

| BMId | |||||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 35 771 | 31 | 0.87 | 0.79 (0.50-1.24) | 0.70 (0.48-1.00) | ||

| Healthy weight (18.5-24.9) | 948 354 | 1047 | 1.10 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | ||

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 657 287 | 721 | 1.10 | 1.01 (0.84-1.20) | 1.23 (1.09-1.37) | ||

| Obesity | |||||||

| Grade I (30.0-34.9) | 355 859 | 432 | 1.21 | 1.16 (0.90-1.49) | 1.56 (1.36-1.78) | ||

| Grade II/III (≥35.0) | 275 029 | 318 | 1.16 | 1.18 (0.89-1.57) | 1.72 (1.49-1.99) | ||

Abbreviations: BI-RADS, Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; OR, odds ratio.

Based on 20 imputed data sets. The multivariable model included screening interval, age (linear and squared), examination year (linear and squared), race and ethnicity, menopausal status, first-degree family history of breast cancer, personal history of breast biopsy, breast density, BMI, age at first live birth, false-positive screening mammography result within the previous 5 years, interaction between linear age and breast density, interaction between age and false-positive screening mammography result within the previous 5 years, and interaction between menopausal status and BMI.

Age was modeled as a continuous variable; ORs at specific decades of age are given to illustrate patterns in the interactions between age and other risk factors.

False-positive screening mammography result within the previous 5 years.

ORs under the columns for age 40 y and age 50 y indicate premenopausal; ORs under age 60 y and age 70 y indicate postmenopausal.

Overall, 11.2% of annual screeners had high 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS compared with 2.7% among biennial screeners and 1.1% among triennial screeners (Table 4). Women aged 40 to 49 years had the lowest proportion in the intermediate or high-risk groups, whereas women aged 70 to 74 years had the highest proportion.

Table 4. Cumulative Risk of Screen-Detected Ductal Carcinoma In Situ After 6 Years of Annual, Biennial, or Triennial Screeninga.

| Risk group | No. (%) of examinations by risk level | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very low (<0.10%) | Low (0.10%-0.19%) | Average (>0.19%-0.38%) | Intermediate (>0.38%-0.63%) | High (>0.63%) | |

| Annual | |||||

| Overall | 47 207 (1.5) | 268 548 (8.4) | 1 402 774 (43.8) | 1 124 054 (35.1) | 358 473 (11.2) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 40-49 | 37 948 (4.0) | 156 068 (16.3) | 529 250 (55.4) | 211 452 (22.1) | 21 383 (2.2) |

| 50-59 | 9027 (0.9) | 89 484 (8.7) | 511 931 (49.7) | 345 344 (33.5) | 74 909 (7.3) |

| 60-69 | 232 (0.0) | 22 495 (2.5) | 291 503 (32.6) | 417 143 (46.6) | 164 000 (18.3) |

| 70-74 | 0 (0.0) | 502 (0.2) | 70 090 (22.0) | 150 115 (47.1) | 98 181 (30.8) |

| Biennial | |||||

| Overall | 154 427 (4.8) | 660 269 (20.6) | 1 780 858 (55.6) | 517 726 (16.2) | 87 776 (2.7) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 40-49 | 102 094 (10.7) | 308 176 (32.2) | 495 955 (51.9) | 47 178 (4.9) | 2697 (0.3) |

| 50-59 | 46 072 (4.5) | 243 678 (23.6) | 599 289 (58.1) | 128 422 (12.5) | 13 235 (1.3) |

| 60-69 | 6213 (0.7) | 96 257 (10.8) | 527 984 (59.0) | 224 549 (25.1) | 40 372 (4.5) |

| 70-74 | 48 (0.0) | 12 158 (3.8) | 157 631 (49.4) | 117 578 (36.9) | 31 472 (9.9) |

| Triennial | |||||

| Overall | 279 219 (8.7) | 992 054 (31.0) | 1 618 357 (50.6) | 277 519 (8.7) | 33 909 (1.1) |

| Age group, y | |||||

| 40-49 | 173 859 (18.2) | 410 547 (42.9) | 353 770 (37.0) | 17 097 (1.8) | 827 (0.1) |

| 50-59 | 86 203 (8.4) | 364 912 (35.4) | 516 284 (50.1) | 58 742 (5.7) | 4555 (0.4) |

| 60-69 | 18 743 (2.1) | 189 491 (21.2) | 543 585 (60.7) | 128 494 (14.4) | 15 060 (1.7) |

| 70-74 | 414 (0.1) | 27 104 (8.5) | 204 718 (64.2) | 73 185 (23.0) | 13 467 (4.2) |

The numbers (percentages) of screening examinations are adjusted by US population weights and standardized to same population for different screening intervals. High risk is the top 5%, intermediate risk is the 75th to 95th percentile, average risk is the 25th to 75th percentile, low risk is the 5th to 25th percentile, and very low risk is the lowest 5%.

The model predicting DCIS detection at a single screening round was well calibrated, with an E/O ratio of 1.00 (95% CI, 0.97-1.03) and little deviation from unity across all deciles of predicted risk (eFigure in Supplement 1). The adjusted AUC for predicting DCIS detection was 0.639 (95% CI, 0.630-0.648).

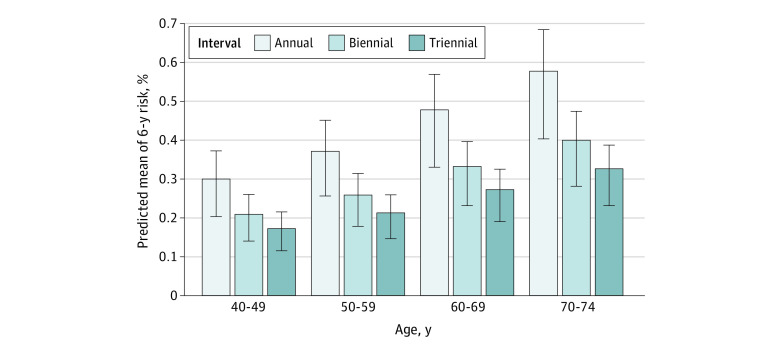

Mean cumulative 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS was higher with increasing age and shorter screening interval (Figure; eTables 1-4 in Supplement 1). Among women aged 40 to 49 years, the mean 6-year screen-detected DCIS risk was 0.30% (IQR, 0.21%-0.37%) for annual screening, 0.21% (IQR, 0.14%-0.26%) for biennial screening, and 0.17% (IQR, 0.12%-0.22%) for triennial screening. For women aged 70 to 74 years, the mean cumulative risks were 0.58% (IQR, 0.41%-0.69%) after 6 annual screens, 0.40% (IQR, 0.28%-0.48%) after 3 biennial screens, and 0.33% (IQR, 0.23%-0.39%) after 2 triennial screens.

Figure. Mean Predicted Cumulative 6-Year Risk of Screen-Detected Ductal Carcinoma In Situ by Age and Screening Interval.

Within each age group, predictions were standardized to a common population for comparing predicted risks with different screening intervals. Weights of the study population were adjusted to reflect the US female population based on age, race and ethnicity, and first-degree family history of breast cancer. Error bars represent the IQRs.

eTables 1 through 4 in Supplement 1 list the mean cumulative 6-year risks of screen-detected DCIS by decade of age according to women’s risk factors and screening interval. For example, the 6-year risk of DCIS detection for women aged 50 to 59 years undergoing annual screening ranged from 0.34% (IQR, 0.24%-0.41%) for women with no prior benign breast biopsy to 1.11% (IQR, 0.80%-1.35%) for women with a history of proliferative benign breast disease with atypia, whereas the risk was 0.24% (IQR, 0.17%-0.29%) for women with no prior benign breast biopsy and 0.76% (IQR, 0.55%-0.93%) for women with a history of proliferative benign breast disease with atypia who underwent biennial screening.

Discussion

The results of this cohort study suggest that DCIS detection rates on mammography screening vary by screening interval and clinical risk factors. Cumulative risk of screen-detected DCIS after 6 years of annual screening is substantially higher than for women undergoing 3 biennial screens. Age, first-degree family history of breast cancer, and history of benign breast biopsy are particularly strong risk factors for screen-detected DCIS. Breast density is a strong risk factor among younger women, and history of false-positive mammography results and obesity are strong risk factors among older women. Our risk prediction model integrates screening interval and individual risk factors to estimate the probability of screen-detected DCIS. These risk estimates can be used by policy makers in conjunction with estimates of other breast cancer screening outcomes (such as cumulative risk of false-positive mammography results and advanced cancer) when evaluating the balance of screening benefits and harms by screening interval.15,16

Ductal carcinoma in situ currently makes up more than 30% of screen-detected breast cancer in the US.27 Although the goal of breast cancer screening is early detection, screening recommendations from the US Preventive Services Task Force and the American Cancer Society acknowledge concerns about overdiagnosis and overtreatment of DCIS.10,11 Ductal carcinoma in situ is considered a nonobligate precursor of invasive breast cancer.28 Given the potential for subsequent invasive cancer and the current inability to reliably distinguish high-risk from indolent DCIS, treatment guidelines for DCIS recommend breast-conserving surgery and consideration of radiation therapy and endocrine therapy.29 Locoregional therapy reduces the risk of subsequent invasive breast cancer but has not been shown to influence overall survival or breast cancer–specific survival.30,31,32,33,34,35 Given the morbidity of DCIS treatments and evolving biological models of DCIS progression,28 many scientists have called for reconsideration of how DCIS is managed,36,37,38 and trials of active surveillance for low-grade DCIS are ongoing.39,40,41

Consistent with the recently published model of cumulative advanced breast cancer risk,15 we estimated 6-year risk of screen-detected DCIS to inform decision-making about mammography screening strategies. Previous studies13,15,27,42 have identified risk groups that can undergo biennial screening with little adverse change in risk of advanced cancer or life-years gained compared with annual mammography. Our results indicate that women who have low advanced cancer risk with biennial screening (eg, women with healthy weight and nondense breasts)15 would also experience reduced cumulative DCIS detection with a biennial vs annual screening interval. Of note, risk of screen-detected DCIS on a single screening round was higher with increasing time since last mammography, reflecting the longer interval for DCIS to emerge. However, the probability of screen-detected DCIS for biennial mammography is only 40% to 45% higher than annual mammography; similarly, the probability of screen-detected DCIS for triennial mammography is less than 3 times that of annual mammography. Consequently, cumulative DCIS risk after 6 years of screening is substantially lower for women undergoing 2 triennial or 3 biennial screens compared with 6 annual screens.

Our results do not directly provide new insights into the natural history of DCIS. Potential advantages of increased DCIS detection could include lower-interval invasive breast cancer rates.5 Annual screening may offer the opportunity to detect DCIS that has a short sojourn time.43 However, simulation modeling suggests that increased detection of DCIS with more frequent screening corresponds to increased overdiagnosis,44 and population-based data show that large increases in DCIS incidence do not lead to a reduction in early-stage invasive cancer incidence or mortality.45 Thus, uncertainty exists regarding whether screen-detected DCIS is a potential screening harm or benefit. Physicians referring women for screening may wish to consider advanced cancer risk as the primary outcome influencing screening frequency and supplemental imaging.15 Our results could be used to estimate the effect of the chosen screening strategy on the risk of DCIS detection and are relevant for policy makers considering a wide range of outcomes associated with different population-level screening strategies.10

Our study results are consistent with an extensive literature demonstrating that benign breast disease history, family history of breast cancer, breast density, BMI, and age at first live birth are associated with overall DCIS risk.46,47,48,49 To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate the history of false-positive mammography results in relation to future DCIS risk, although prior studies50,51 have identified false-positive mammography as a risk factor for breast cancer overall (invasive or DCIS). Our study provides new insights regarding interactions between age and breast density and false-positive mammography results in relation to risk of screen-detected DCIS. We also observed that the risk of screen-detected DCIS was higher among Asian women and lower among Hispanic/Latina women compared with White women. Reasons for these differences require further exploration.

Prior studies52,53,54,55,56 have demonstrated increases in overall or invasive breast cancer detection with DBT, but few have directly assessed DCIS detection. A meta-analysis57 of 4 European prospective, observational studies found that DCIS detection was higher on DBT vs digital mammography, whereas a large US-based observational study58 and a European randomized clinical trial59 both observed no difference in DCIS detection by modality. Our study found no difference in DCIS detection rate on DBT vs digital mammography after adjustment for other factors. Differences in study populations (eg, age and breast density), European vs US radiologist practices, the proportion of prevalent vs incident screening examinations, and covariate adjustments could contribute to the observed differences across studies.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths, including the large, diverse, population-based sample and the prospective collection of risk factor information. However, as with any observational study, some limitations exist. Residual confounding could still impact differences in risk estimates by screening interval. Data on menopausal status and BMI were missing for a substantial fraction of examinations. We used multiple imputation to avoid bias that would have resulted from exclusion of examinations with incomplete data.60 We did not examine DCIS rates by nuclear grade, which correlates with risk of subsequent invasive breast cancer.61 We used cross-validation to assess the accuracy of our model. The AUC optimism and SEs for the risk factor ORs did not account for the process of selecting interactions for inclusion in the model and as a result may be underestimated. External validation is needed to evaluate model performance in other populations.61

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this cohort study suggest wide variation in the probability of DCIS detection according to screening interval and clinical risk factors. Our risk model permits estimation of the probability of screen-detected DCIS during a 6-year time horizon according to mammography screening frequency and women’s risk factors. Our findings can be used by policy makers assessing the balance of benefits and harms of different screening strategies, in conjunction with existing risk models for other screening outcomes, such as advanced cancers and false-positive mammography results.15,16

eMethods. Technical Details of Risk Model Development and Evaluation

eFigure. Calibration Results for Model Predicting Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS

eTable 1. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 40-49 Years

eTable 2. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 50-59 Years

eTable 3. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 60-69 Years

eTable 4. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 70-74 Years

eTable 5. Summary of Variables in the Multiple Imputation Model

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Esserman L, Shieh Y, Thompson I. Rethinking screening for breast cancer and prostate cancer. JAMA. 2009;302(15):1685-1692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Independent UK Panel on Breast Cancer Screening . The benefits and harms of breast cancer screening: an independent review. Lancet. 2012;380(9855):1778-1786. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61611-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehman CD, Arao RF, Sprague BL, et al. National Performance benchmarks for modern screening digital mammography: update from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Radiology. 2017;283(1):49-58. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016161174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mannu GS, Wang Z, Broggio J, et al. Invasive breast cancer and breast cancer mortality after ductal carcinoma in situ in women attending for breast screening in England, 1988-2014: population based observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1570. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duffy SW, Dibden A, Michalopoulos D, et al. Screen detection of ductal carcinoma in situ and subsequent incidence of invasive interval breast cancers: a retrospective population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):109-114. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00446-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson HD. Mammography screening and overdiagnosis. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(2):261-262. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.4096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandelblatt JS, Stout NK, Schechter CB, et al. Collaborative modeling of the benefits and harms associated with different U.S. breast cancer screening strategies. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):215-225. doi: 10.7326/M15-1536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Etzioni R, Gulati R, Mallinger L, Mandelblatt J. Influence of study features and methods on overdiagnosis estimates in breast and prostate cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):831-838. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-11-201306040-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ryser MD, Lange J, Inoue LYT, et al. Estimation of breast cancer overdiagnosis in a U.S. breast screening cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175(4):471-478. doi: 10.7326/M21-3577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force . Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279-296. doi: 10.7326/M15-2886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. ; American Cancer Society . Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sprague BL, Miglioretti DL, Lee CI, Perry H, Tosteson AAN, Kerlikowske K. New mammography screening performance metrics based on the entire screening episode. Cancer. 2020;126(14):3289-3296. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trentham-Dietz A, Kerlikowske K, Stout NK, et al. ; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network . Tailoring breast cancer screening intervals by breast density and risk for women aged 50 years or older: collaborative modeling of screening outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(10):700-712. doi: 10.7326/M16-0476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cintolo-Gonzalez JA, Braun D, Blackford AL, et al. Breast cancer risk models: a comprehensive overview of existing models, validation, and clinical applications. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;164(2):263-284. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4247-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerlikowske K, Chen S, Golmakani MK, et al. Cumulative advanced breast cancer risk prediction model developed in a screening mammography population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2022;114(5):676-685. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djac008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ho TH, Bissell MCS, Kerlikowske K, et al. Cumulative probability of false-positive results after 10 years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e222440. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.2440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. ; STROBE initiative . Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(8):W163-94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American College of Radiology . ACR BI-RADS—Mammography. 5th ed. ACR BI-RADS Atlas: Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System. American College of Radiology; 2013. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Reporting-and-Data-Systems/Bi-Rads

- 19.Dupont WD, Page DL. Risk factors for breast cancer in women with proliferative breast disease. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(3):146-151. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page DL, Dupont WD, Rogers LW, Rados MS. Atypical hyperplastic lesions of the female breast. A long-term follow-up study. Cancer. 1985;55(11):2698-2708. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page DL, Schuyler PA, Dupont WD, Jensen RA, Plummer WD Jr, Simpson JF. Atypical lobular hyperplasia as a unilateral predictor of breast cancer risk: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):125-129. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12230-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tice JA, Miglioretti DL, Li CS, Vachon CM, Gard CC, Kerlikowske K. Breast density and benign breast disease: risk assessment to identify women at high risk of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3137-3143. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.8869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White IR, Royston P. Imputing missing covariate values for the Cox model. Stat Med. 2009;28(15):1982-1998. doi: 10.1002/sim.3618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hubbard RA, Ripping TM, Chubak J, Broeders MJ, Miglioretti DL. Statistical methods for estimating the cumulative risk of screening mammography outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25(3):513-520. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Census Bureau . Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex: Single Year of Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States. US Census Bureau; 2017. Accessed May 27, 2019. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/datasets/2010-2017/national/asrh/

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics . 2015 National Health Interview Survey. National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2015_data_release.htm

- 27.Miglioretti DL, Zhu W, Kerlikowske K, et al. ; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium . Breast tumor prognostic characteristics and biennial vs annual mammography, age, and menopausal status. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(8):1069-1077. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Seijen M, Lips EH, Thompson AM, et al. ; PRECISION team . Ductal carcinoma in situ: to treat or not to treat, that is the question. Br J Cancer. 2019;121(4):285-292. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0478-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2021. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1419

- 30.Correa C, McGale P, Taylor C, et al. ; Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) . Overview of the randomized trials of radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010(41):162-177. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wapnir IL, Dignam JJ, Fisher B, et al. Long-term outcomes of invasive ipsilateral breast tumor recurrences after lumpectomy in NSABP B-17 and B-24 randomized clinical trials for DCIS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(6):478-488. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cuzick J, Sestak I, Pinder SE, et al. Effect of tamoxifen and radiotherapy in women with locally excised ductal carcinoma in situ: long-term results from the UK/ANZ DCIS trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(1):21-29. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70266-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donker M, Litière S, Werutsky G, et al. Breast-conserving treatment with or without radiotherapy in ductal carcinoma in situ: 15-year recurrence rates and outcome after a recurrence, from the EORTC 10853 randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(32):4054-4059. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.5077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wärnberg F, Garmo H, Emdin S, et al. Effect of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ: 20 years follow-up in the randomized SweDCIS Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(32):3613-3618. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Narod SA, Iqbal J, Giannakeas V, Sopik V, Sun P. Breast cancer mortality after a diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):888-896. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esserman L, Yau C. Rethinking the standard for ductal carcinoma in situ treatment. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1(7):881-883. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benson JR, Jatoi I, Toi M. Treatment of low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ: is nothing better than something? Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(10):e442-e451. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30367-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fallowfield L, Francis A. Overtreatment of low-grade ductal carcinoma in situ. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(3):382-383. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Francis A, Fallowfield L, Rea D. The LORIS Trial: addressing overtreatment of ductal carcinoma in situ. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2015;27(1):6-8. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2014.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elshof LE, Tryfonidis K, Slaets L, et al. Feasibility of a prospective, randomised, open-label, international multicentre, phase III, non-inferiority trial to assess the safety of active surveillance for low risk ductal carcinoma in situ: the LORD study. Eur J Cancer. 2015;51(12):1497-1510. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hwang ES, Hyslop T, Lynch T, et al. The COMET (Comparison of Operative versus Monitoring and Endocrine Therapy) trial: a phase III randomised controlled clinical trial for low-risk ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e026797. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-026797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Ravesteyn NT, Schechter CB, Hampton JM, et al. ; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network . Trade-offs between harms and benefits of different breast cancer screening intervals among low-risk women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(8):1017-1026. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yen MF, Tabár L, Vitak B, Smith RA, Chen HH, Duffy SW. Quantifying the potential problem of overdiagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ in breast cancer screening. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39(12):1746-1754. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(03)00260-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Ravesteyn NT, van den Broek JJ, Li X, et al. Modeling ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS): an overview of CISNET model approaches. Med Decis Making. 2018;38(1_suppl):126S-139S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X17729358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bleyer A, Welch HG. Effect of three decades of screening mammography on breast-cancer incidence. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1998-2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1206809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Puvanesarajah S, Gapstur SM, Gansler T, Sherman ME, Patel AV, Gaudet MM. Epidemiologic risk factors for in situ and invasive ductal breast cancer among regularly screened postmenopausal women by grade in the Cancer Prevention Study-II Nutrition Cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2020;31(1):95-103. doi: 10.1007/s10552-019-01253-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerlikowske K. Epidemiology of ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010(41):139-141. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Peila R, Arthur R, Rohan TE. Risk factors for ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast in the UK Biobank cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;64:101648. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2019.101648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trentham-Dietz A, Newcomb PA, Storer BE, Remington PL. Risk factors for carcinoma in situ of the breast. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9(7):697-703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Henderson LM, Hubbard RA, Sprague BL, Zhu W, Kerlikowske K. Increased risk of developing breast cancer after a false-positive screening mammogram. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(12):1882-1889. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Román M, Hofvind S, von Euler-Chelpin M, Castells X. Long-term risk of screen-detected and interval breast cancer after false-positive results at mammography screening: joint analysis of three national cohorts. Br J Cancer. 2019;120(2):269-275. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0358-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Conant EF, Zuckerman SP, McDonald ES, et al. Five consecutive years of screening with digital breast tomosynthesis: outcomes by screening year and round. Radiology. 2020;295(2):285-293. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Conant EF, Barlow WE, Herschorn SD, et al. ; Population-based Research Optimizing Screening Through Personalized Regimen (PROSPR) Consortium . Association of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography with cancer detection and recall rates by age and breast density. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(5):635-642. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.7078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lowry KP, Coley RY, Miglioretti DL, et al. Screening performance of digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography in community practice by patient age, screening round, and breast density. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2011792. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marinovich ML, Hunter KE, Macaskill P, Houssami N. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis or mammography: a meta-analysis of cancer detection and recall. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(9):942-949. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sprague BL, Coley RY, Kerlikowske K, et al. Assessment of radiologist performance in breast cancer screening using digital breast tomosynthesis vs digital mammography. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201759. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Houssami N, Zackrisson S, Blazek K, et al. Meta-analysis of prospective studies evaluating breast cancer detection and interval cancer rates for digital breast tomosynthesis versus mammography population screening. Eur J Cancer. 2021;148:14-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL, et al. Breast cancer screening using tomosynthesis in combination with digital mammography. JAMA. 2014;311(24):2499-2507. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.6095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hofvind S, Moshina N, Holen AS, et al. Interval and subsequent round breast cancer in a randomized controlled trial comparing digital breast tomosynthesis and digital mammography screening. Radiology. 2021;300(1):66-76. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Greenland S, Finkle WD. A critical look at methods for handling missing covariates in epidemiologic regression analyses. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142(12):1255-1264. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kerlikowske K, Molinaro A, Cha I, et al. Characteristics associated with recurrence among women with ductal carcinoma in situ treated by lumpectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2003;95(22):1692-1702. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djg097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Technical Details of Risk Model Development and Evaluation

eFigure. Calibration Results for Model Predicting Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS

eTable 1. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 40-49 Years

eTable 2. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 50-59 Years

eTable 3. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 60-69 Years

eTable 4. Variation in Mean Predicted Cumulative Six-Year Risk of Screen-Detected DCIS by Screening Interval and Risk Factors Among Women Aged 70-74 Years

eTable 5. Summary of Variables in the Multiple Imputation Model

Data Sharing Statement