Abstract

Objective:

In recent years, transcranial magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (tcMRgFUS) has been established as a potential treatment option for movement disorders, including essential tremor (ET). So far, however, little is known about the impact of tcMRgFUS on structural connectivity. The objective of this study was to detect microstructural changes in tremor- and motor-related white matter tracts in ET patients treated with tcMRgFUS thalamotomy.

Methods:

Eleven patients diagnosed with ET were enrolled in this tcMRgFUS thalamotomy study. For each patient, 3 Tesla magnetic resonance imaging (3T MRI) including structural and diffusion MRI were acquired and the Clinical Rating Scale for Tremor was assessed before the procedure as well as 1 year after the treatment. Diffusion MRI tractography was performed to identify the cerebello-thalamo-cortical tract (CTCT), the medial lemniscus, and the corticospinal tract in both hemispheres on pre-treatment data. Pre-treatment tractography results were co-registered to post-treatment diffusion data. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) metrics, including fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD) and radial diffusivity (RD), were averaged across the tracts in the pre- and post-treatment data.

Results:

The mean value of tract-specific DTI metrics changed significantly within the thalamic lesion and in the CTCT on the treated side (p < 0.05). Changes of DTI-derived indices within the CTCT correlated well with lesion overlap (FA: r = −0.54, p = 0.04; MD: r = 0.57, p = 0.04); RD: r = 0.67, p = 0.036). Further, a trend was seen for the correlation between changes of DTI-derived indices within the CTCT and clinical improvement (FA: r = 0.58; p = 0.062; MD: r = −0.52, p = 0.64; RD: r = −0.61 p = 0.090).

Conclusions:

Microstructural changes were detected within the CTCT after tcMRgFUS, and these changes correlated well with lesion-tract overlap. Our results show that diffusion MRI is able to detect the microstructural effects of tcMRgFUS, thereby further elucidating the treatment mechanism, and ultimately to improve targeting prospectively.

Impact statement

The results of this study demonstrate microstructural changes within the cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways 1 year after MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy. Even more, microstructural changes within the cerebello-thalamo-cortical pathways correlated significantly with clinical outcome. These findings do not only highly emphasize the need of new targeting strategies for MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy but also help to elucidate the treatment mechanism of it.

Keywords: diffusion tensor imaging, essential tremor, microstructural change, MR-guided focused ultrasound, structural connectivity, tractography

Introduction

Transcranial magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (tcMRgFUS) thalamotomy has recently been introduced as a new and less invasive treatment option to provide substantial and stable relief in patients with severe or medication-refractory essential tremor (ET) (Chang et al., 2018; Elias et al., 2013, 2016; Lipsman et al., 2013; Ravikumar et al., 2017; Zaaroor et al., 2017). By concentrating multiple intersecting beams of ultrasound within a deep target in the brain, it is possible to induce cell necrosis at the convergence of the multiple beams by thermal ablation.

Current devices used for tcMRgFUS can be integrated with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), leading to a high precision and accuracy of the guidance procedure. Due to ultrasound energy distortions induced by the skull and the reliance on focusing from a phased array of multiple ultrasound transducers surrounding the brain, it is easier to achieve accurate targeting in the deep brain compared with more superficial locations (Fishman and Frenkel, 2017). Similar to radiofrequency thalamotomy or deep brain stimulation (DBS), tcMRgFUS traditionally targets the ventral intermediate nucleus (VIM) of the thalamus.

To improve clinical outcome and minimize the risk of adverse events, recent studies have targeted specific fiber tracts instead of atlas-based, anatomic targeting of the VIM (Akram et al., 2018; Chazen et al., 2017; Coenen et al., 2014; Fenoy and Schiess, 2017; Tian et al., 2018; Tsolaki et al., 2017). However, a few studies have investigated the underlying treatment mechanisms leading to tremor suppression or the impact of tcMRgFUS on the targeted fiber tracts.

So far, only limited data are published regarding the structural and functional changes after tcMRgFUS or DBS treatment. Functional MRI studies have reported reduced connectivity in visual, motor, and attention networks after tcMRgFUS, but these studies did not investigate changes in fiber tracts that might be helpful for target identification (Jang et al., 2016; Tuleasca et al., 2018). In addition, both Wintermark et al. (2014) and Buijink et al. (2014) used diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) (but not tractography) to examine changes in DTI metrics after tcMRgFUS thalamotomy and detected changes in multiple brain regions that were part of the Guillain-Mollaret triangle and the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network. These studies used either region of interest (ROI) based or voxel-based analysis to detect microstructural changes but did not look at diffusion changes associated with specific tracts.

Tractography has been used by previous tcMRgFUS studies to detect fiber tracts that are part of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network and improve individual target identification (Akram et al., 2018; Chazen et al., 2017; Coenen et al., 2014; Fenoy and Schiess, 2017; Tian et al., 2018; Tsolaki et al., 2017). However, these studies do not report follow-up imaging nor give further insight into microstructural changes caused by tcMRgFUS. Determining which tracts are affected by the most successful treatments provides important data for how to use tractography prospectively for targeting.

The objective of our study was to combine tractography and DTI to explore microstructural changes within white matter fiber tracts believed to be affected by tcMRgFUS thalamotomy in ET patients. We hypothesized that microstructural changes in the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network would correlate with the clinical outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Study cohort

On approval of the Stanford Institutional Review Board (protocol no. IRB 32859), 11 patients (5 female, mean age: 76.5 years, range: 70–87 years, demographic information available in Table 1) with medication-refractory ET were prospectively enrolled in this longitudinal study. Written, informed consent was obtained from all patients. All patients participated in a previous clinical trial, with results reported elsewhere (Federau et al., 2017; Tian et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Patient | Age (in years) | Sex | Treated hemisphere | CRST pre-treatment | CRST post-treatment | ΔCRST (%) | Lesion volume (mm3) | Lesion-tract overlap (mm3) | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 74 | Male | Left | 17 | 16 | −5.9 | 7.0 | 5.3 | |

| S2 | 69 | Female | Right | 23 | 17 | −26.1 | 17.6 | 3.5 | |

| S3 | 75 | Male | Left | 18 | — | — | 59.8 | 33.4 | |

| S4 | 86 | Female | Left | 19 | 6 | −68.4 | 73.8 | 66.8 | |

| S5 | 76 | Male | Left | 17 | 14 | −17.7 | 10.5 | 0 | |

| S6 | 84 | Female | Right | 16 | 6 | −62.5 | 40.4 | 10.6 | |

| S7 | 70 | Male | Left | 21 | 7 | −66.7 | 73.8 | 44.0 | Mild dysmetria |

| S8 | 75 | Male | Left | 20 | 11 | −45.0 | 45.7 | 24.6 | Gait discoordination |

| S9 | 70 | Male | Left | 11 | 6 | −45.5 | 40.4 | 28.1 | |

| S10 | 70 | Female | LEFT | 22 | 20 | −9.1 | 54.5 | 19.3 | |

| S11 | 81 | Female | Left | 14 | 9 | −35.7 | 42.2 | 38.7 |

Post-treatment clinical scores for patient S3 could not be obtained.

Δ implicates the percent changes between the pre-treatment and post-treatment CRST scores.

CRST, Clinical Rating Scale for Tremor.

Lesions were planned in the VIM contralateral to their dominant hand (nine patients were right hand dominant and two were left hand dominant), using 3 Tesla MRI (3T MRI) (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) and a clinical system for focused ultrasound surgery (ExAblate Neuro4000; InSightec, Haifa, Israel). Two patients (S1 and S7) underwent a sham procedure in which no thalamic lesion was induced but crossed over to active treatment 3 months after the sham procedure was performed.

In one patient (S3), the first treatment did not reach high enough temperatures in the target area due to device limitations. Specifically, there was a governor limiting the power and some settings were changed to allow higher voltage to the elements. This limitation was removed, and the patient was treated a second time on the same side 3 months after the first treatment.

All patients received an additional 3T MRI immediately before the procedure as well as 1 year post procedure with a scan protocol, including anatomical and diffusion MRI scans. In addition, the Clinical Rating Scale for Tremor (CRST) was assessed at both dates (Fahn et al., 1993).

MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy and lesion targeting

The details of focused ultrasound thalamotomy have been previously described (Federau et al., 2017). Briefly, stereotactic targeting of the VIM was performed in consultation with the treating neurologist or neurosurgeon in the intercommissural plane using the following rules: 25% of the distance from the anterior to the posterior commissure (typically 6–7 mm rostral from the posterior commissure), and 10–11 mm lateral from the wall of the third ventricle (resulting in a final target 13–15 mm lateral from the midline).

Although DTI data were acquired before the procedure, it was not used for targeting. Targeting was performed shortly before sonications started on balanced steady-state gradient echo sequence (GE FIESTA) images (repetition time [TR] = 4.592 msec, echo time [TE] = 2.184 msec, flip angle 35°, matrix size 244 × 288, field of view [FOV] 22 cm, slice thickness 2 mm, bandwidth 244 kHz/pixel).

Clinical assessments

Clinical impairment was assessed using the CRST (Fahn et al., 1993). All patients were scored immediately before the treatment and at 12 months after tcMRgFUS thalamotomy. One of the subjects (S3) was not available for the post-treatment clinical assessment due to personal reasons (the post-treatment imaging data of S3 were still acquired). Patients who underwent sham treatment first were evaluated before the sham treatment, then a second time before the actual tcMRgFUS thalamotomy, and one last time 12 months after the actual treatment. In those cases, the CRST scores before sham treatment were defined as baseline scores to avoid a possible bias of the placebo effect. To prevent inter-rater variability, pre- and post-treatment scores were always assessed by the same blinded rater.

The CRST comprises three components: Part A (“tremor”), Part B (“tasks”), and Part C (“disability”). An upper extremity tremor sub-score with a maximum of 32 points was measured by combining parts A and B for the hand that was affected by the treatment. Subsequently, the percent change was calculated between the pre- and post-treatment CRST.

MRI protocol

All MR imaging was performed on the same 3T scanner (Discovery MR750; GE Healthcare) at baseline and 12 months after the treatment. The MR imaging protocol included a three-dimensional T2-weighted (T2w) fast spin echo sequence (TE/TR = 83.5/2500 ms, flip angle = 90°, 180 slices, FOV = 240 × 240 mm2, slice thickness = 1 mm, slice spacing = 0.5 mm, voxel size = 0.75 × 0.75 × 1.0 mm, acquisition time = 7 min) and a two-dimensional twice-refocused diffusion-weighted spin-echo echo-planar imaging sequence (TE/TR = 81.6/8500 ms, flip angle = 90°, 69 slices, FOV = 240 × 240 mm2, slice thickness = 2 mm, zero slice spacing, voxel size = 1.875 × 1.875 × 2.0 mm3, 60 directions uniformly distributed on a sphere, gradient b value 2500 s/mm2, acquisition time = 10 min).

Model fitting and probabilistic tractography

Image pre-processing and probabilistic tractography were performed on the diffusion data using tools contained in the FMRIB Software Library (FSL, v5.0.7) (Jenkinson et al., 2012). Diffusion data were corrected for motion and eddy current distortions using FSL's “eddy” function. Diffusion tensor model was fitted using FSL's “dtifit” function to derive the fractional anisotropy (FA), mean diffusivity (MD), and radial diffusivity (RD) maps. Ball-and-stick model (up to three sticks) was fitted using FSL's “bedpostx” function to derive the voxel-wise crossing fiber orientation distributions.

Probabilistic tractography was performed using FSL's “probtrackx2” function. To determine “seed” and “target” regions for tractography, ROIs were manually outlined on baseline T2w images by two neuroradiologists (M.W. and C.T. with 13 and 4 years of imaging experience) using the FSLView visualization software of FSL (Fig. 1B–D). Tractography was performed only on the baseline diffusion data since thalamic gliosis caused by the treatment and visible on the post-treatment images would have influenced the tract reconstruction.

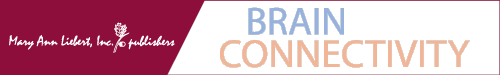

FIG. 1.

Example of ROI placement and tractography results in a representative patient. (A) The CTCT (blue), CST (red), and ML (green) overlaid on T1w images (affinely co-registered to T2w images using the reg_aladin function from the NiftyReg software with the default parameters) in sagittal, coronal, and axial views. Examples of seed, target, and waypoints for the (B) CTCT, (C) CST, and (D) ML. CST, corticospinal tract; CTCT, cerebello-thalamo-cortical tract; ML, medial lemniscus; ROI, region of interest; T2w, T2-weighted.

Probabilistic tractography was performed for delineating the corticospinal tract (CST) and medial lemniscus (ML) because of their close proximity to the lesion target and their possible implication in side-effects of the procedure. The cerebello-thalamo-cortical tract (CTCT) was also included to test the hypothesis that microstructural changes in the CTCT would correlate with the best clinical outcomes. “Seed” and “target” ROIs were determined for each tract as follows:

-

(1)

CST, with the precentral gyrus as “seed” and the cerebral peduncle as the “target”;

-

(2)

ML, with the dorsolateral area of the pons as the “seed” and the postcentral gyrus as “target”;

-

(3)

CTCT, with the dentate nucleus as the “seed” and the contralateral precentral gyrus as the “target.” For the tracking of the CTCT, the ipsilateral superior cerebellar peduncle, the contralateral red nucleus, and the contralateral thalamus were set as the “waypoints” (Kwon et al., 2011; Yamada et al., 2010). Of note, the segment of the CTCT between the dentate nucleus and the thalamus is referred to as the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract in prior literature. To take account of this, we divided the tract into two segments in the treated hemisphere: one segment between the dentate nucleus and the thalamus (including the voxels within the thalamus) and the other segment between the thalamus (including the voxels within the thalamus) and the precentral gyrus.

For the CST and ML, minimal fiber length was set to 30 mm. For the CTCT, minimal fiber length was set to 20 mm. For all tracts, a total of 5000 streamlines per seed voxel were initiated with a curvature threshold of 80° and an FA threshold of 0.2, which is comparable to former studies (Kwon et al., 2011; Tsolaki et al., 2017; Yamada et al., 2010). The tracking stopped when the maximum number of steps was reached (i.e., 2000 by default). With the default step length of 0.5 mm, this corresponded to a maximal fiber length of 1 m. An example of successful fiber tractography and ROI placement is shown in Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S2.

The tractography results provided a probabilistic map, with a value for each brain voxel corresponding to the total number of streamlines that passed from the “seed” region through that voxel to the “target” region. The probabilistic map was then thresholded to include only voxels with values 1% or more of the total number of streamlines from the “seed” region that reached the “target” region (called “waytotal” number).

Probabilistic maps generated with thresholds at 5% and 10% were also assessed, but the 1% threshold generated the most anatomical accurate tracts based on visual inspection/validation by a neuroradiologist (C.T.). After thresholding, the tracts were binarized. Since probabilistic tractography was only performed on images before treatment, the fiber tracts were transformed to the post-treatment diffusion images (with nearest-neighbor interpolation) using transformations generated from a co-registration between the pre- and post-treatment b0 images.

Analyses were performed on a rack server equipped with 24 Intel Xeon E5-2630 CPUs at 2.60 GHz and 256 GB RAM. FSL's bedpostX took ∼8 h, although this can now be run with bedpostX_gpu in ∼2 h. Each tracking took ∼10 min and varied depending on the tract size and the brain size of the subject. The affine and non-linear co-registration took ∼5 and ∼60 min, with some variation depending on the brain size of the subject.

Lesion delineation

In each patient, the thalamic lesion was outlined on the post-treatment T2w images by a neuroradiologist (M.W.). The delineated lesion ROIs were then mapped to the post- and pre-treatment diffusion image space using the obtained non-linear transformation.

Image co-registration

The pre-treatment diffusion image was aligned to the post-treatment diffusion image using non-linear co-registration to account for the susceptibility-induced image distortions. Specifically, the post-treatment diffusion b = 0 image was first linearly registered to the pre-treatment b = 0 image using NiftyReg's “reg_aladin” function (default parameters) (Modat et al., 2014). The transformed b = 0 image was then non-linearly registered to the pre-treatment b = 0 image using NiftyReg's “reg_f3d” function (default parameters) (Modat et al., 2010).

The affine and non-linear transformations were inversed and integrated into a single transformation using NiftyReg's “reg_transform” function to transform binary masks of fiber tract ROIs delineated on the pre-treatment diffusion image to the post-treatment diffusion image space using nearest-neighbor interpolation using NiftyReg's “reg_resample” function.

In addition, the post-treatment T2w images were co-registered to the pre- and post-treatment diffusion data, using the same algorithm described earlier. Binary masks of lesion ROIs delineated on the post-treatment T2w image were transformed to the pre- and post-diffusion image space using the resultant transformation using nearest-neighbor interpolation.

All co-registration results were visually examined and confirmed for quality control (a representative axial slice containing parts of the thalamus of the post-treatment b = 0 image volume, and the pre-treatment b = 0 image volume and post-treatment T2w image volume non-linearly co-registered to the post-treatment b = 0 image volume available in Supplementary Fig. S1). To quantify the image similarity and ensure the quality of image co-registration, the cross-correlations between the pre-treatment b = 0 image and the co-registered post-treatment T2w image, the post-treatment b = 0 image and the co-registered post-treatment T2w image, and the post-treatment b = 0 image and the co-registered pre-treatment b = 0 image were computed using the “MeasureImageSimilarity” function from the Advanced Normalization Tools (Avants et al., 2011), which were consistently high for all subjects (group means ± group standard deviation [SD] as 0.949 ± 0.0053, 0.951 ± 0.0053 and 0.989 ± 0.0028, respectively).

Statistical analysis

For each subject, the mean values of FA, MD, and RD of all voxels within binary masks of the lesion and fiber tracts of interest in both the pre- and post-treatment spaces were calculated. The group mean and the group SD of the mean values of FA, MD, and RD across the 11 patients were also calculated.

The overlap of the lesion and the fiber tract was quantified by calculating the number of voxels of the lesion within a certain fiber tract. In an attempt to correct for the potential impact of differing degrees of lesion thoroughness and permanence, the percent FA change within the lesion was selected as surrogate marker. FA was chosen as the surrogate marker for lesion thoroughness and permanence, because FA demonstrated the largest changes within the lesion pre- and post-treatment. The lesion-tract overlap (in mm3) was then multiplied by the percent FA change within the lesion to obtain a weighted lesion-tract overlap.

To test for normal distribution, the Shapiro-Wilk test was used. Since changes of the mean FA, MD, and RD were normally distributed in all tracts and lesions, a paired-sample t-test was used to test for statistical significance between pre- and post-treatment mean values of FA, MD, and RD of all voxels within fiber tracts and lesions. To account for multiple comparisons, p-values were adjusted for all tracts, including five tracts on the treated hemisphere (i.e., the full CTCT, the upper and lower segments of the CTCT, the ML and the CST), three tracts on the untreated hemisphere (i.e., the full CTCT, the ML and the CST), and the lesion (i.e., in total of nine comparisons) using false discovery rate (FDR) supplied by the Benjamini-Hochberg method. p-values of <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant for all tests. The CTCT was not divided into upper and lower segments on the untreated side, because there was no lesion to provide a clear division.

Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were used to describe correlations between changes of DTI metrics within all tracts and the lesion and clinical improvement, which was measured as percent change of part A and B of the CRST, as well as the lesion-tract overlap. The p-values were adjusted as described earlier for each correlation. To ensure that the correlations between changes of DTI metrics and the lesion-tract overlap were not driven by the weighted, lesional region of the tract, the changes of the mean FA, MD, and RD within the fiber tracts were re-calculated excluding the lesional voxels and the correlation was then performed again as described earlier.

Results

Clinical scores

Mean CRST sub-scores Part A + B for the hand that was affected by the treatment decreased significantly from 18 (±3.6; n = 11) at baseline to 12.2 (±5.2; n = 10) 12 months after tcMRgFUS treatment (p = 0.001). Adverse events were reported for two subjects (S7: mild dysmetria; S8: gait discoordination) who were still present after 12 months. An overview about CRST sub-scores A + B for each patient is given in Table 1.

Imaging results

The group mean of the FA, MD, and RD differed significantly between pre- and post-treatment acquisitions inside the lesion ROI (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S3). Over the 11 patients, nine showed this pattern, but in two patients, these DTI metrics demonstrated only minimal or no change inside the lesion (S5, S10).

Table 2.

Pre-Treatment and Post-Treatment Diffusion Tensor Imaging Metrics for the Treated Hemisphere

| Tract segment | Fractional anisotropy |

Mean diffusivity (10−3 mm2/s) |

Radial diffusivity (10−3 mm2/s) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | p | Adjusted p-value | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | p | Adjusted p-value | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | p | Adjusted p-value | |

| CTCT | ||||||||||||

| Dentate Ncl.—precentral gyrus | 0.502 (±0.034) | 0.491 (±0.037) | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.565 (±0.021) | 0.578 (±0.029) | 0.023 | 0.069 | 0.387 (±0.018) | 0.402 (±0.031) | 0.007 | 0.021 |

| Dentate Ncl.—thalamus | 0.524 (±0.039) | 0.506 (±0.043) | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.584 (±0.03) | 0.586 (±0.029) | 0.830 | 1.000 | 0.385 (±0.022) | 0.396 (±0.03) | 0.134 | 0.241 |

| Thalamus—precentral gyrus | 0.494 (±0.035) | 0.485 (±0.038) | 0.003 | 0.015 | 0.556 (±0.027) | 0.574 (±0.037) | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.388 (±0.026) | 0.404 (±0.038) | 0.002 | 0.009 |

| CST | 0.553 (±0.021) | 0.546 (±0.024) | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.581 (±0.022) | 0.584 (±0.033) | 0.567 | 0.851 | 0.376 (±0.022) | 0.385 (±0.035) | 0.065 | 0.146 |

| ML | 0.502 (±0.025) | 0.502 (±0.024) | 0.778 | 0.778 | 0.573 (±0.018) | 0.579 (±0.022) | 0.152 | 0.34 | 0.392 (±0.018) | 0.397 (±0.02) | 0.163 | 0.245 |

| Lesion | 0.457 (±0.095) | 0.207 (±0.079) | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.573 (±0.049) | 0.849 (±0.216) | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.417 (±0.073) | 0.765 (±0.212) | 0.001 | 0.009 |

The group mean (±group SD) of the mean value of the DTI metrics, including fractional anisotropy, mean diffusivity, and radial diffusivity within the CTCT and its segments, CST, ML and the lesion for the treated hemisphere before and after the treatment. p-Values are adjusted for multiple comparison using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. Significant p-values are marked in bold.

CST, corticospinal tract; CTCT, cerebello-thalamo-cortical tract; ML, medial lemniscus; SD, standard deviation.

Probabilistic tractography detected connections that followed the expected anatomy for the CST, ML, and CTCT in all patients and each hemisphere (Supplementary Fig. S4).

At baseline, there were no significant left-right hemispheric differences in tract-specific mean FA, MD, or RD. For the untreated side, there were no significant pre- and post-treatment differences in tract-specific mean FA, MD, or RD (Supplementary Table S1).

For the treated side, there were significant pre- and post-treatment differences in mean FA (−2.2%, p = 0.018, after adjusting for FDR) and RD (+3.9%, p = 0.02, after adjusting for FDR) within the CTCT whereas the pre- and post-treatment difference in the mean MD was not significant (+2.3%, p = 0.07, after adjusting for FDR). To further examine the changes within the CTCT, we examined the results from the two segments of CTCT.

The FA decreased significantly in both segments (−3.4% in the segment between dentate nucleus and thalamus, −1.8% in the segment between thalamus and precentral gyrus). The MD and RD only increased significantly in the segment between the thalamus and the precentral gyrus (+3.2% for MD and +4.1% for RD) but not between the dentate nucleus and the thalamus (p = 1.0 and p = 0.24, after adjusting for FDR). The FA also decreased significantly within the CST on the treated side by a mean of −1.3% (p = 0.02, after adjusting for FDR), whereas no significant changes were found in MD or RD.

No significant changes were found in the ML between pre- and post-treatment. All p-values relating to tract-specific DTI parameter changes are listed in Table 2. For a detailed overview of the DTI parameters in the CTCT for each patient, see Supplementary Table S2.

Correlations between microstructural changes and clinical outcome

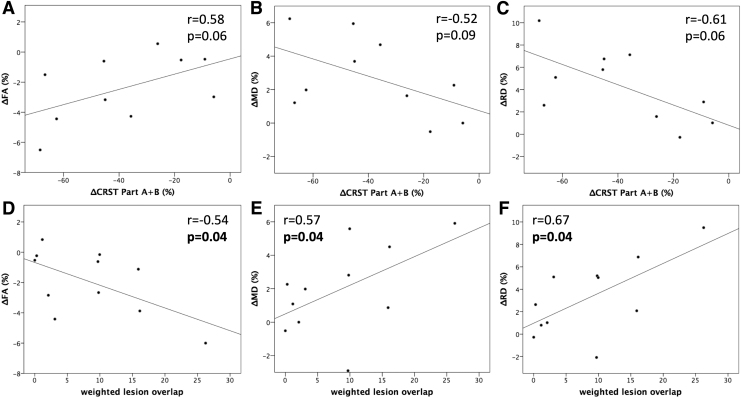

Significant correlations were found between clinical improvement (i.e., percent change of part A and B of the CRST) and changes in FA and RD within the CTCT on the treated side (r = 0.58, p = 0.041; r = −0.61, p = 0.030) but not in MD (r = −0.52, p = 0.064). However, after adjusting for multiple comparisons, statistical significance was not reached for FA or RD (FA: p = 0.062; RD: p = 0.090; MD: p = 0.64). Correlations between changes in DTI metrics within the CTCT and clinical outcome are displayed in Figure 3A–C.

FIG. 3.

Correlation between changes of DTI metrics within the CTCT and the clinical outcome as well as the tract-lesion overlap. The correlation between changes of DTI metrics and clinical outcome was performed on only data from 10 subjects since the post-treatment clinical scores were not available for one subject (S3) due to personal reasons. Δ implicates the percent changes between the pre-treatment and post-treatment DTI metrics and CRST scores. The p-values reported in the panels are adjusted to account for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. (A–C) Correlation between changes of DTI metrics within the CTCT and clinical improvement. (D–F) Correlation between changes of DTI metrics within the CTCT and weighted lesion overlap. CRST, Clinical Rating Scale for Tremor; DTI, diffusion tensor imaging.

No significant correlations were obtained for FA or RD within the lesion ROI and clinical improvement (r = 0.19; p = 0.302; r = −0.39, p = 0.156), though MD changes within the lesion ROI correlated significantly with clinical improvement (r = −0.55, p = 0.049). After adjusting for multiple comparison, statistical significance was missed for MD (p = 0.147).

Correlations between microstructural changes and lesion/tract overlap

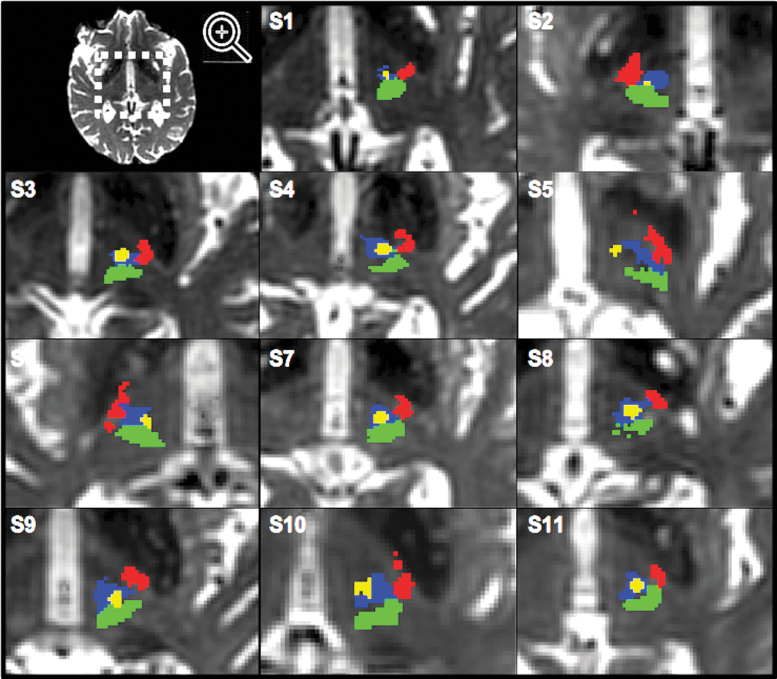

In all but one patient (S5), the thalamic lesion overlapped with the CTCT (Fig. 2). In one patient, the lesion also overlapped with the ML (S9). The mean overlap between the CTCT and the lesion was 26.3 (±21.3) mm3.

FIG. 2.

Lesion location in relation to tract location within the thalamus. CTCT (blue), CST (red), ML (green), and tcMRgFUS lesion (yellow) overlaid on post-treatment T2w images of all patients (S1–S11). tcMRgFUS, transcranial magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound.

Correlations between weighted tract-lesion overlap and microstructural changes within the CTCT were statistically significant for all DTI metrics, even after adjusting the p-value for multiple comparisons (FA: r = −0.68, raw p = 0.01, adjusted p = 0.015; MD: r = 0.6, raw p = 0.026, adjusted p = 0.026; RD: r = 0.69, raw p = 0.009, adjusted p = 0.027). Correlations were still significant for microstructural changes that were computed, excluding the lesional voxels (FA: r = −0.54, raw p = 0.044, adjusted p = 0.044; MD: r = 0.57, raw p = 0.026, adjusted p = 0.039; RD: r = 0.67, raw p = 0.012, adjusted p = 0.036). Correlations between changes in DTI metrics within the CTCT excluding the lesional regions and the weighted tract-lesion overlap are displayed in Figure 3D–F.

Discussion

This longitudinal study using DTI and probabilistic tractography identified significant microstructural changes within the ipsilateral CTCT 12 months after tcMRgFUS thalamotomy in ET patients. Our data demonstrate significant correlations between changes in DTI metrics in the CTCT and the weighted lesion overlap with the tract. Importantly, changes in the CTCT correlated well with clinical improvement, though statistical significance was closely missed due to the adjustment of the p-values for multiple comparisons.

According to current pathophysiological models, abnormal oscillations of a tremor network connecting the cerebellum, thalamus, and primary motor cortex are hypothesized to cause tremor in ET patients (Muthuraman et al., 2012; Raethjen et al., 2007; Schnitzler et al., 2009). Although DBS uses a phase-linked stimulation to modulate the neural activity within the affected brain networks, the focal tissue damage caused by tcMRgFUS thalamotomy is hypothesized to lead to cell destruction and axonal degeneration within this tremor network (namely the CTCT), which subsequently reduces or even stops these abnormal oscillatory activities and reduces tremor (Cagnan et al., 2014).

To monitor structural tract changes afterctcMRgFUS thalamotomy, we used DTI-derived measures, including FA, MD, and RD. Altered DTI metrics, especially decreased FA, have been linked to tract degeneration (Ciccarelli et al., 2006; Concha et al., 2010; Mädler et al., 2008). Analyzing tract changes after tcMRgFUS helps to detect and understand factors that are associated with improved outcomes after treatment and hopefully improve targeting prospectively by demonstrating how to best use tractography to guide the targeting procedure.

Even though this study was a retrospective analysis and did not use probabilistic tractography for the aiming procedure, our results support the recent trend to use probabilistic tractography for optimal targets identification (Akram et al., 2018; Chazen et al., 2017; Coenen et al., 2014; Fenoy and Schiess, 2017; Tian et al., 2018; Tsolaki et al., 2017). Further, DTI metrics within the lesion or along the tract could be used as a helpful imaging biomarker to control and monitor the effectiveness of tcMRgFUS (Hori et al., 2019).

By doing so, measurements of post-tcMRgFUS tract changes might help explain why some patients do not benefit as much clinically from the procedure by identifying tcMRgFUS treatments that either did not achieve an optimal location for the lesion or did not achieve a sufficiently thorough and/or permanent lesion to affect the tract microstructure.

Our results support and extend the findings of Wintermark et al., 2014, who also reported decreased FA in areas projecting to the ipsilateral dentato-rubro-thalamic tract and CST after tcMRgFUS in ET patients. As a fundamental difference to previous studies, we used a tract-based approach to analyze changes within entire tracts. Therefore, we were not only able to detect the impact of tcMRgFUS on important neuronal circuits but also able to correlate these changes with the lesion load.

Although Wintermark et al. (2014) detected those changes up to 3 months after the treatment, we were able to identify changes in DTI metrics that remained after 12 months, indicating stable and durable microstructural tract alterations. This is consistent with recently published clinical data that demonstrated stable tremor suppression over 2 years after the treatment (Chang et al., 2018; Elias et al., 2016).

Clinical data beyond this point are not yet available. To evaluate the microstructural properties and possible regeneration of white matter fiber tracts over a longer period of time, further longitudinal clinical and imaging studies would be needed.

We found FA changes in both the lower (between dentate nucleus and thalamus) and upper part (between thalamus and precentral gyrus) of the CTCT. However, the FA change was greater for the lower (−3.4%) compared with the upper part (−1.8%) of the CTCT. This is similar to the results found by Pineda-Pardo et al. (2019), which led to their hypothesis that decreasing FA values within the afferent fibers were possibly due to retrograde decay of afferent axons from the VIM. In the upper segment of the CTCT, MD and RD changes were more pronounced compared with the lower segment (MD: 3.2% vs. 0.3%; RD: 4.1% vs. 2.9%). This finding could be explained by myelin clearance at the subcortical white matter below the motor cortex (Beaulieu, 2002; Pineda-Pardo et al., 2019).

In this study, DTI metrics did not change significantly within the tracts on the untreated side or in the ipsilateral ML. Hence, tcMRgFUS thalamotomy does not seem to cause long-lasting microstructural alterations in the global brain networks, but only in tracts that are directly affected by the thalamic lesion. However, it has been reported that transient changes in global brain networks may occur right after the treatment but recover in the short term, whereas changes in the CTCT seem to be durable (Jang et al., 2016).

Since no significant changes were obtained in the fiber tracts on the untreated side, we are also confident that the changes on the treated side are related to the treatment and not caused by physiological brain aging or other neuropathological processes. Of note, FA also decreased significantly within the CST on the treated side, although the significance of this finding is unclear as no limb or body weakness was noted by patients or their neurologists at follow-up. It is possible that the CTCT and the CST cannot be fully resolved for tractography purposes.

That is, some voxels likely contain elements of both tracts, causing changes within the CTCT to impact the values in the CST. To segment the tracts, we performed probabilistic tractography, which is still prone to false positives and negatives but has been demonstrated to be more sensitive and provide more accurate tracking solutions of the CTCTs than certain deterministic tracking approaches (Schlaier et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2014). In addition, for optimizing intra-voxel crossing fiber detection we followed recent recommendations, including sufficient spatial resolution (1.875 × 1.875 × 2.0 mm), high b-values (2500 s/mm2), and a high number of diffusion encoding directions (60 gradients) (Jones et al., 2013).

Longitudinal changes in DTI metrics within the CTCT correlated well with the weighted overlap between the lesion and the CTCT. Further, the overlap between the lesion and cerebellar tracts correlated well with clinical outcome, consistent with our previous findings (Tian et al., 2018). In this study, we used a weighted lesion overlap (i.e., multiplying the lesion/tract overlap by the percent FA change within the lesion) in an attempt to correct for the potential impact of differing degrees of lesion thoroughness and permanence.

Hirato et al. have demonstrated that the lateral area of the VIM plays an important role in tremor suppression and highly selective ablation of the most lateral part of the VIM is effective (Hirato et al., 2018). Though we did not determine the exact lesion location within the CTCT and the thalamus, we can still assume that a larger lesion/tract overlap leads to an increased likelihood to affect the important areas. Consequently, there is mounting evidence for the value of using probabilistic tractography seems to improve lesion targeting and potentially facilitate performing tcMRgFUS thalamotomy (Chazen et al., 2017; Tsolaki et al., 2017).

In this study, we used a well-established, atlas-based aiming procedure, which has been previously described by several studies to target the VIM (Chang et al., 2015; Elias et al., 2013; Federau et al., 2017). However, it was not the aim of this study to investigate lesion targeting and future prospective studies would be needed to validate this method.

Two patients of the study cohort experienced persistent adverse events (mild dysmetria and gait discoordination). We could not detect any abnormal changes within the examined tracts after tcMRgFUS treatment in these two patients compared with the others. Also, no excessive overlap with the CTCT, CST, or ML was detected. In another patient (S9), we detected an overlap between the lesion and the ML but no side effects were reported or documented. Gait disturbance and sensory problems constitute the largest number of adverse events Motor and gait problems are caused mainly by inferior and lateral lesions, whereas sensory problems are caused by posterior involvement (Segar et al., 2021).

Hence, causes and risk factors for adverse events after tcMRgFUS thalamotomy remain a question of critical debate and should be a main focus in future studies.

Although we report a trend toward changes in DTI metrics within the CTCT correlating with clinical improvement, for some patients these changes were not commensurate. For example, some patients showed a large change in FA within the CTCT but only a subtle clinical improvement or vice versa. For future studies, there may be value in identifying sub-portions of the CTCT for which microstructure changes are more strongly associated with clinical improvement. Another important consideration is the possibility that there is a specific ablation location within the cross-sectional area of intra-thalamic CTCT tract (i.e., a sub-tract within the CTCT) that will produce an optimal therapeutic effect.

Further, three patients (S2, S9, S10) showed only minimal FA changes within the CTCT in post-treatment images even though the lesion was overlapping with the CTCT. Though we tried to capture the differing degrees of lesion thoroughness and permanence by calculating a weighted lesion overlap, there might have been other possible influencing factors we did not investigate, for example, the exact lesion location in the thalamus (as discussed by Hirato et al., 2018), thermal dose during the procedure, tissue resilience, or location of the lesion overlap within the CTCT.

There are a few limitations to our study. First, only a small number of patients were enrolled in this study, which lowers the overall statistical power. tcMRgFUS is still a novel treatment option performed at specialized medical centers in the United States and around the world. Naturally, patient numbers are, in general, low compared with more established procedures, such as DBS. Due to the low patient number and overall statistical power, we were not able to reach statistical significance for the correlation between changes of DTI parameters within the CTCT and clinical impairment after adjusting for multiple comparison.

Second, we quantified DTI metrics in a limited number of white matter fiber tracts at pre- and 12 months post-treatment and may have missed the impact of tcMRgFUS thalamotomy on other important brain networks or time points. Third, we segmented the CTCT, which is more commonly referred to as the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract by prior literature, into two segments, namely a cerebello-thalamic segment between the dentate nucleus and the thalamus and a thalamo-cortical segment between the thalamus and the precentral gyrus.

Both tracts include voxels within the thalamus, which are the ending and starting regions of the two tracts anatomically, respectively, and therefore cannot be completely separated from each other. This must be taken into consideration when looking at our results that examined the microstructural changes within the two segments. Further, only the mean values of the DTI metrics within fiber tracts were used in our study to measure the microstructural changes. Along-tract analysis with more sophisticated MRI acquisition schemes that gain sensitivity to more specific features such as myelin content (van der Weijden et al., 2021) and axon diameters and density (Veraart et al., 2020) could improve sensitivity to post-treatment changes.

Further insight into the underlying histological processes after tcMRgFUS could also help to optimize imaging studies in terms of how and where to look for post-treatment tissue changes that correlate strongly with a meaningful clinical improvement. From a clinical point of view, post-processing of dMRI and tractography can be time consuming and requires a high expertise in the field to ensure a robust result. Ongoing development of the tractography software is needed to enable more automated methods. With the subtle changes observed in our study cohort, the clinical implications can be limited.

Finally, even though there was only a 6% difference in the in-plane and through-plane spatial resolution of the diffusion data in our study (i.e., 1.875 × 1.875 × 2.0 mm3), the slightly anisotropic voxels might lead to spatial biases in the diffusion tractography results and the delineation of fiber tracts that confound the reported findings. Isotropic spatial resolution is recommended for acquiring diffusion MRI data and tractography in future studies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found significant changes in DTI metrics within the CTCT after tcMRgFUS thalamotomy. Further, our results demonstrate a correlation between lesion location in the thalamus and microstructural changes within the CTCT. Our work provides novel information about brain connectivity after tcMRgFUS and helps to gain further insight into the underlying mechanisms leading to tremor suppression. In addition, since correlations between FA and RD within the CTCT and clinical improvement showed a trend toward statistical significance, it might be a helpful imaging biomarker to control treatment effectiveness and identify optimal lesion targets, such as the CTCT.

Supplementary Material

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization: C.T., Q.T., M.W., and J.A.M. Data curation: C.T., Q.T., P.G., C.H.H., J.M.H., M.Z., M.G., K.B.P., and J.A.M. Formal analysis: C.T., Q.T., C.L., and J.A.M. Methodology: C.T., Q.T., M.W., P.G., R.D.A., M.Z., M.G., and J.A.M. Project administration: M.W., J.A.M. Resources: M.W., P.G., C.H.H., J.M.H., R.D.A., J.F., K.B.P., and J.A.M. Visualization: C.T., Q.T., and C.L. Writing—original draft preparation: C.T., C.L., and J.A.M. Writing—review and editing: C.T., Q.T., M.W., P.G., C.H.H., J.M.H., R.D.A., C.L., M.Z., M.G., K.B.P., and J.A.M.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

Funding Information

The authors would like to acknowledge funding from the National Institutes of Health: R01 NS095985, R01 MH111444, P41 EB015891, S10 RR026351, the Dana Foundation, the Focused Ultrasound Foundation, InSightec, GE Healthcare, and the German Research Foundation (DFG, reference no.: TH 2235/1-1).

Supplementary Material

References

- Akram H, Dayal V, Mahlknecht P, et al. 2018. Connectivity derived thalamic segmentation in deep brain stimulation for tremor. Neuroimage Clin 18:130–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, et al. 2011. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage 54:2033–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu C. 2002. The basis of anisotropic water diffusion in the nervous system - a technical review. NMR Biomed 15:435–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijink AW, Caan MW, Contarino MF, et al. 2014. Structural changes in cerebellar outflow tracts after thalamotomy in essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 20:554–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cagnan H, Little S, Foltynie T, et al. 2014. The nature of tremor circuits in parkinsonian and essential tremor. Brain 137:3223–3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JW, Park CK, Lipsman N, et al. 2018. A prospective trial of magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: results at the 2-year follow-up. Ann Neurol 83:107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang WS, Jung HH, Kweon EJ, et al. 2015. Unilateral magnetic resonance guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: practices and clinicoradiological outcomes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 86:257–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazen JL, Sarva H, Stieg PE, et al. 2018. Clinical improvement associated with targeted interruption of the cerebellothalamic tract following MR-guided focused ultrasound for essential tremor. J Neurosurg 129:315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli O, Behrens TE, Altmann DR, et al. 2006. Probabilistic diffusion tractography: a potential tool to assess the rate of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 129:1859–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenen VA, Allert N, Paus S, et al. 2014. Modulation of the cerebello-thalamo-cortical network in thalamic deep brain stimulation for tremor: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurosurgery 75:657–669; discussion 669–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concha L, Livy DJ, Beaulieu C, et al. 2010. In vivo diffusion tensor imaging and histopathology of the fimbria-fornix in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci 30:996–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias WJ, Huss D, Voss T, et al. 2013. A pilot study of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. N Engl J Med 369:640–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias WJ, Lipsman N, Ondo WG, et al. 2016. A randomized trial of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. N Engl J Med 375:730–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn S, Tolosa E, Marin C. 1993. Clinical rating scale for tremor. In: Jankovic J, Tolosa E (eds.) Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorders, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; pp. 225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Federau C, Goubran M, Rosenberg J, et al. 2018. Transcranial MRI-guided high-intensity focused ultrasound for treatment of essential tremor: a pilot study on the correlation between lesion size, lesion location, thermal dose, and clinical outcome. J Magn Reson Imaging 48:58–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenoy AJ, Schiess MC. 2017. Deep brain stimulation of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract: outcomes of direct targeting for tremor. Neuromodulation 20:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman PS, Frenkel V. 2017. Focused ultrasound: an emerging therapeutic modality for neurologic disease. Neurotherapeutics 14:393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirato M, Miyagishima T, Takahashi A, et al. 2018. Superselective thalamotomy in the most lateral part of the ventralis intermedius nucleus for controlling essential and parkinsonian tremor. World Neurosurg 109:e630–e641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori H, Yamaguchi T, Konishi Y, et al. 2019. Correlation between fractional anisotropy changes in the targeted ventral intermediate nucleus and clinical outcome after transcranial MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: results of a pilot study. J Neurosurg 132:568–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang C, Park HJ, Chang WS, et al. 2016. Immediate and longitudinal alterations of functional networks after thalamotomy in essential tremor. Front Neurol 7:184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TEJ, et al. 2012. NeuroImage 62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Knösche TR, Turner R. 2013. White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: the do's and don'ts of diffusion MRI. NeuroImage 73:239–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HG, Hong JH, Hong CP, et al. 2011. Dentatorubrothalamic tract in human brain: diffusion tensor tractography study. Neuroradiology 53:787–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsman N, Schwartz ML, Huang Y, et al. 2013. MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: a proof-of-concept study. Lancet Neurol 12:462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mädler B, Drabycz SA, Kolind SH, et al. 2008. Is diffusion anisotropy an accurate monitor of myelination? Magn Reson Imaging 26:874–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modat M, Cash DM, Daga P, et al. 2014. Global image registration using a symmetric block-matching approach. J Med Imaging 1:024003–024005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modat M, Ridgway GR, Taylor ZA, et al. 2010. Fast free-form deformation using graphics processing units. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 98:278–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuraman M, Heute U, Arning K, et al. 2012. Oscillating central motor networks in pathological tremors and voluntary movements. What makes the difference? NeuroImage 60:1331–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda-Pardo JA, Martinez-Fernandez R, Rodriguez-Rojas R, et al. 2019. Microstructural changes of the dentato-rubro-thalamic tract after transcranial MR guided focused ultrasound ablation of the posteroventral VIM in essential tremor. Hum Brain Mapp 40:2933–2942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raethjen J, Govindan RB, Kopper F, et al. 2007. Cortical involvement in the generation of essential tremor. J Neurophysiol 97:3219–3228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravikumar VK, Parker JJ, Hornbeck TS, et al. 2017. Cost-effectiveness of focused ultrasound, radiosurgery, and DBS for essential tremor. Mov Disord 32:1165–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaier JR, Beer AL, Faltermeier R, et al. 2017. Probabilistic vs. deterministic fiber tracking and the influence of different seed regions to delineate cerebellar-thalamic fibers in deep brain stimulation. Eur J Neurosci 45:1623–1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzler A, Munks C, Butz M, et al. 2009. Synchronized brain network associated with essential tremor as revealed by magnetoencephalography. Mov Disord 24:1629–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar DJ, Lak AM, Lee S, et al. 2021. Lesion location and lesion creation affect outcomes after focused ultrasound thalamotomy. Brain 144:3089–3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas C, Ye FQ, Irfanoglu MO, et al. 2014. Anatomical accuracy of brain connections derived from diffusion MRI tractography is inherently limited. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:16574–16579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Q, Wintermark M, Elias WJ, et al. 2018. Diffusion MRI tractography for improved transcranial MRI-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy targeting for essential tremor. Neuroimage Clin 19:572–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsolaki E, Downes A, Speier W, et al. 2017. The potential value of probabilistic tractography-based for MR-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor. Neuroimage Clin 17:1019–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuleasca C, Najdenovska E, Régis J, et al. 2018. Ventro-lateral motor thalamus abnormal connectivity in essential tremor before and after thalamotomy: a resting-state fMRI study. World Neurosurg 113:e453–e464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Weijden CWJ, Garcia DV, Borra RJH, et al. 2021. Myelin quantification with MRI: a systematic review of accuracy and reproducibility. Neuroimage 226:117561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veraart J, Nunes D, Rudrapatna U, et al. 2020. Nonivasive quantification of axon radii using diffusion MRI. Elife 9:e49855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wintermark M, Huss DS, Shah BB, et al. 2014. Thalamic connectivity in patients with essential tremor treated with MR imaging-guided focused ultrasound: in vivo fiber tracking by using diffusion-tensor MR imaging. Radiology 272:202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Akazawa K, Yuen S, et al. 2010. MR imaging of ventral thalamic nuclei. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 31:732–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaaroor M, Sinai A, Goldsher D, et al. 2018. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound thalamotomy for tremor: a report of 30 Parkinson's disease and essential tremor cases. J Neurosurg 128:202–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.