Abstract

The regio- and stereoselective carbosilylation of tosylynamides with allylic trimethylsilanes takes place under mild conditions in the presence of catalytic TMSNTf2 or HNTf2 to give (Z)-α-allyl-β-trimethylsilylenamides with good yields. Theoretical calculations show the activation of the C–C triple bond of the ynamides by the trimethylsilylium ion and formation of a β-trimethylsilylketenimonium cation. Further transformations of the products demonstrate the synthetic utility of this reaction.

Silylium ion has been consolidated in the past two decades as a potent catalyst in organic synthesis.1 Its strong Lewis acid character is reflected in its high affinity not only to σ- but also to π-bases. This makes silylium ion a simpler and more sustainable alternative to catalytic metal salts or transition metal complexes for the activation of C–C multiple bonds. Since the pioneering work of Lambert et al., employing 1,1-disubstituted alkenes,2 several examples of silylium-catalyzed hydro-3−6 and carbosilylation7 of C–C double bonds have appeared. However, there are few precedents related to the activation of triple C–C bonds with silylium ion.8 In this context, Kawashima et al. recently described a silylium catalyzed intermolecular silylation of an arylalkyne9 to form a β-silyl stabilized vinylcation, that was subsequently intercepted by an intramolecular Friedel–Crafts ring closure.

Exploring new ways for the activation of electron rich triple C–C bonds, ynamides could be good candidates to broad the scope of silylium ion catalysis. The tendency of ynamides to be activated by electrophilic species such as acids and transition metals,10 and the polarization of their C–C triple bond allow many regioselective reactions.10,11 Moreover, the 1,2 functionalization of ynamides offers the possibility to obtain functionalized and highly substituted nitrogenated alkenes.12 Thus, the silylation of these compounds represents an entry to nitrogen-substituted vinylsilanes,13 of great value in organic synthesis.

Several methods to install a silyl group in one of the carbon atoms of ynamides have been described (Figure 1). Thus, α,β-silylmetalation and subsequent attack of an electrophile to the metal position is the most common method for this purpose (Figure 1A); for instance, the silylcupration14 and the Pd-catalyzed silylstannation15 of ynamides result in α-metalated (Z)-β-silylenamides; alternatively, Pd-catalyzed silylboration leads to β-metalated (Z)-α-silylenamides;16 finally, α-metalated (E)-β-silylenamides can be obtained from a trans-selective radical silylzincation of ynamides.17

Figure 1.

Ynamide silylation methods.

Apart from the silylmetalation approach, β-silyl-(Z)-enamides can also selectively be obtained by hydrosilylation of ynamides using a rhodium complex18 or tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane19 as catalyst; in both cases, the hydride abstraction from the silane by the corresponding catalyst leads to a silylium ion, responsible for the formation of a β-silyl ketenimonium intermediate I (Figure 1B). Very recently, a palladium catalyzed silylcyanation was described; the reaction proceeds in a stereo- and regioselective way through a β-palladium enamide intermediate II (Figure 1C).20

On the other hand, the precedented reactions of allylsilanes with C–C multiple bonds catalyzed by Brønsted or Lewis acids21−23 and the possibility of self-regeneration of catalytic silylium moved us to choose allylsilane derivatives as carbon nucleophile counterparts for our study on the catalytic carbosilylation of ynamides (Figure 1D). Therefore, herein we develop a regio- and stereoselective allylsilylation of ynamides, using catalytic silylium ion, an alternative to other species such as metal salts and transition metal complexes.

Our first experiments focused on the reaction between tosylynamide 1a and allyltrimethylsilane 2a in 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) using a direct silylium ion freshly prepared source like N-trimethylsilyl bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide, TMSNTf2,24 or an acid like bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide, HNTf2, as initiators (10 mol %).25 To our delight, we obtained in both cases the corresponding allylsilylated enamide 3a, in 50% and 35% yield, respectively, with complete regio- and stereoselectivity (Table 1, entries 1 and 2).

Table 1. Optimization of the Reaction of Ynamide 1a and Allylsilane 2aa.

| entry | initiator (mol %) | 2a (equiv) | solvent | yieldb (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TMSNTf2 (10) | 2 | DCE | 50 |

| 2 | HNTf2 (10) | 2 | DCE | 35 |

| 3 | TMSOTf (10) | 2 | DCE | |

| 4 | TMSNTf2 (10) | 4 | DCE | 54 |

| 5 | HNTf2 (10) | 4 | DCE | 65 |

| 6 | TMSNTf2 (5) | 4 | DCE | 56 |

| 7 | HNTf2 (5) | 4 | DCE | 66, 71c |

| 8 | HNTf2 (5) | 4 | DCM | 64 |

| 9 | HNTf2 (5) | 4 | Et2O | 16 |

| 10 | HNTf2 (5) | 4 | toluene | 28 |

| 11 | HNTf2 (5) | 4 | THF | |

| 12 | HNTf2 (5) | 4 | CH3CN |

1a (0.1 mmol, 1 equiv), 2a (equiv), initiator (mol %), solvent (0.4 M).

Isolated yield after flash chromatography purification on silica gel.

2 mmol scale.

We employed also trimethylsilyl trifluoromethanesulfonate, TMSOTf, as initiator in the same reaction conditions, but in this case, we observed only decomposition of the reagents (Table 1, entry 3). Then, the yields were improved by increasing the ratio of allylsilane 2a to 4-fold excess (Table 1, entries 4,5); additionally, we observed that lowing the initiator loading to 5 mol % did not seem to affect the efficiency of the reaction (Table 1, entries 6 and 7). Furthermore, comparable yields were obtained with other halogenated solvents such as dichloromethane (Table 1, entry 8); however, the yields were significantly lower with diethyl ether or toluene (Table 1 entries 9 and 10), or simply the reaction did not afford any product when using THF or acetonitrile (Table 1, entries 11 and 12). Finally, the reaction was scaled-up to 2 mmol employing 5 mol % HNTf2 with an improved yield of 71% (Table 1, entry 7).

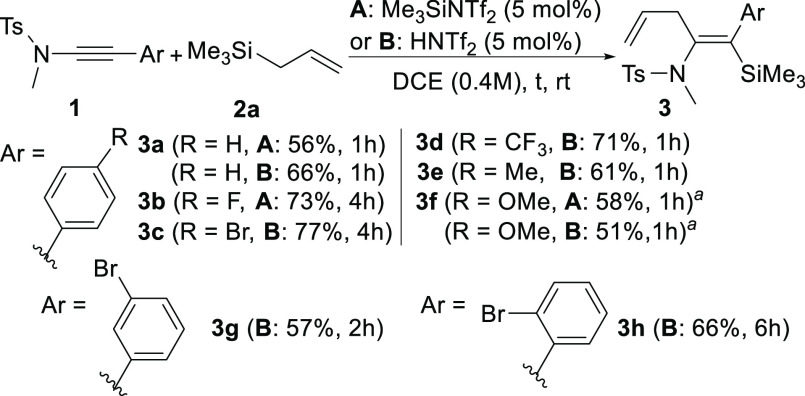

With the optimized conditions in hand, we examined the scope of the reaction. We employed either TMSNTf2 (method A) or HNTf2 (method B) as initiators with different β-aryl-N-methyl-N-tosylynamides 1 and allylsilane 2a (Scheme 1). Thus, α-allyl-β-silyl-(Z)-enamides 3 were obtained with complete regio- and stereoselectivity and good yields (56–77%). In this way, it was proved that the reaction works well with different aryl-substituted ynamides bearing either electron-withdrawing (R = F, Br, CF3, products 3b–d,g,h) or electron-donating (R = Me, MeO, products 3e,f) substituents at different positions of the aryl moiety.

Scheme 1. Reaction of Ynamides 1 and Allyltrimethylsilane 2a.

10 mol % initiator, DCE (0.2 M).

Then, we explored the reactivity of different 2-substituted allylsilanes 2 with a variety of β-aryl-substituted ynamides 1 (Scheme 2). The results were similar or even better than those previously obtained for the parent allyltrimethylsilane 2a (R2 = H). Thus, trimethyl(2-methylallyl)silane 2b gave good yields with diverse ynamides (Scheme 2, R2 = Me, products 3i–n); furthermore, other 2-substituted allylsilanes like trimethyl-(2-phenylally)silane 2c gave also excellent results (Scheme 2, R2 = Ph, products 3o–u). Interestingly, product 3o was obtained almost quantitatively (99%) when the reaction was performed in a 2 mmol scale (Scheme 2). In addition, the structures of products 3j and 3q were unambiguously confirmed by X-ray resolution.26 Continuing our study on 2-arylsubstituted allylsilanes, [2-(4-chlorophenyl)allyl]trimethylsilane 2d (R2 = 4-ClC6H4) and [2-(4-t-buthylphenyl)allyl]trimethylsilane 2e (R2 = tBuC6H4) were also employed to obtain the corresponding silylenamides again with good yields (Scheme 2 products 3v,w and 3x, respectively). Regarding other substitution in the ynamide, we also checked a β-alkyl tosylynamide (R1 = n-butyl) with allylsilanes 2a,b (R2 = H, Me) in similar reaction conditions, but in this case only complex mixtures were obtained.27 However, when an alkenyl β-substituted tosylynamide (Scheme 2, R1 = cinnamyl) was reacted in the same reaction conditions with allylsilane 2c (R2 = Ph), the expected β-silyl-(Z)-enamide 3y was obtained in 51% yield (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Reaction of Ynamides 1 with 2-Substituted Allyltrimethylsilanes 2.

10 mol % initiator, DCE (0.2 M).

99% 2 mol scale, method B.

Ellipsoids at 50% of probability level.

To get some insight into the reaction mechanism, we performed computational studies at the PCM-M05-2X/6-31G*//M05-2X/6-31G* level.26 Starting from tosylynamide 1a and TMSNTf2, the molecular geometry was fully optimized without any molecular symmetry constraint, leading to structure A (Figure 2), a coordination minimum that placed the Si–CPh distance at 4.065 Å, keeping the Si–N bond distance at 1.895 Å. Subsequently, the approach between Si and CPh (Si–CPh distance = 2.195 Å) induces an elongation between Si and N (Si–N distance = 2.538 Å), giving rise to transition state TS1 (+10.3 kcal·mol–1), in which the SiMe3 moiety is rather flat (C–Si–C–C dihedral angle = 165.4°). TS1 evolves to B (+6.2 kcal·mol–1), with formation of the Si–CPh bond (Si–CPh distance = 2.058 Å) and cleavage of the Si–N bond (Si–N distance = 2.906 Å). As also shown in Figure 2, the anti-approximation of allyltrimethylsilane 2a to B gave the coordination minimum Canti (+0.4 kcal·mol–1), with a distance of 4.093 Å between H2C= and CN, which is reduced in the transition state TS2anti (+8.8 kcal·mol–1) to 2.048 Å. TS2anti led to the minimum Danti (−1.2 kcal·mol–1), which in fact has a cyclopropyl structure (bond distances: H2C–CN = 1.592 Å, HC–CN = 1.565 Å, and H2C–HC = 1.464 Å). Finally, the attack of the Tf2N– anion on the silicon atom acts as the driving force of the process, leading directly to the coordination minimum Eanti (−41.4 kcal·mol–1), formed by the allylsilylated enamide 3a and TMSNTf2, without any intermediate being located. Likewise, syn-addition from the coordination minimum Csyn (+2.1 kcal·mol–1) leads to the minimum Dsyn (−2.9 kcal·mol–1) through the transition state TS2syn (+13.6 kcal·mol–1), which shows a distance of 2.300 Å between H2C= and CN. The difference in the energy barriers to reach TS2anti or TS2syn (4.8 kcal·mol–1) could be explained by the β-silicon effect,19 which places the bond angles in B at 107° (Si–CPh–CN) and 131° (Ph–CPh–CN), which avoid syn-approximation and allow us to explain the experimentally found stereoselectivity.26

Figure 2.

Calculated relative energy profile for the formation of β-silylenamides, in kcal·mol–1 (for the sake of comparison, the values shown for A, TS1, and B also include the energy value of 2a) and overall reaction of the proposed catalytic cycle. H atoms have been omitted for clarity.

According to our calculations, the overall process would start from the reaction of 1a with TMSNTf2 and formation of a β-silyl ketenimonium intermediate B and the Tf2N– anion. Intermediate B would receive nucleophilic anti-attack of the C–C double bond of the allylic silane 2a to give the intermediate Danti. The subsequent attack of the Tf2N– anion on the silicon atom leads to β-silylenamide 3a and TMSNTf2, which closes the catalytic cycle (Figure 2).

Finally, to illustrate the synthetic possibilities of enamides 3, we carried out several transformations (Scheme 3). Thus, the reaction of β-silylenamide 3o with a fluoride source, such as tetrabutylammonium fluoride, led to the desilylated enamide 4 (86%) or, alternatively, the coupling product 5 (72%) if the reaction was performed in the presence of 4-bromobenzaldehyde (Scheme 3). The allyl group can also intervene in other transformations; thus, the presence of a catalytic amount of a Brønsted acid (HNTf2, 1 mol %) gave the 1,2-dihydronaphthalene derivative 6 (65%) because of an intramolecular aromatic electrophilic substitution of the carbocation intermediate formed by previous protonation of the 2-phenylallyl substituent (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Further Transformations of silylenamide 3o.

In summary, we have described a regio- and stereoselective carbosilylation of tosylynamides 1 catalyzed by silylium ion. The reaction uses different allylsilanes 2 as the source of the carbon nucleophile and the silicon electrophile. The silylium ion activates the triple C–C bond of the ynamide to produce an electrophilic β-silylketenimonium intermediate B, the subsequent nucleophilic attack by the allylsilane 2 produces the regeneration of the silylium ion to close the catalytic cycle. Theoretical calculations support this mechanistic picture. This versatile reaction leads to (Z)-β-silylenamides 3, interesting building blocks as demonstrated by the possibility of further transformations. Finally, this reaction represents a novel example of catalytic activation of electron rich alkynes by silylium ion.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant from AEI (PID2019-107469RB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033). The authors also thank Prof. J. M. González (Universidad de Oviedo) for helpful discussions and suggestions. Computing resources used in this work were provided by Universidad de La Rioja (Beronia cluster). The authors also acknowledge the technical support provided by Servicios Científico-Técnicos de la Universidad de Oviedo.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00221.

Experimental details, materials and methods, characterization data, NMR spectra for all compounds, X-ray diffraction experiments and computational studies data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

Dedicated to the memory of Professor Gregorio Asensio.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Shaykhutdinova P.; Keess S.; Oestreich M. in Organosilicon Chemistry-Novel Approaches and Reactions; Hiyama T., Oesreich M., Eds.; Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2019; pp 131–170. [Google Scholar]; b Klare H. F. T.; Albers L.; Süsse L.; Keess S.; Müller T.; Oestreich M. Silylium Ions: From Elusive Reactive Intermediates to Potent Catalyst. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 5889–5985. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert J. B.; Zhao Y.; Wu H. β-Silyl and β-Germyl Carbocations Stable at Room Temperature. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 64, 2729–2736. 10.1021/jo982146a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intramolecular hydrosilylation of alkenes:Steinberger H.-U.; Bauch C.; Müller T.; Auner N. A. A metal-free catalytic intramolecular hydrosilylation. Can. J. Chem. 2003, 81, 1223–1227. 10.1139/v03-121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Intermolecular hydrosilylation of alkenes intercepted by a Friedel–Crafts reaction:Arii H.; Yano Y.; Nakabayashi K.; Yamaguchi S.; Yamamura M.; Mochida K.; Kawashima T. Regioselective and Stereoespecific Dehydrogenerative Annulation Utilizing Silylium Ion-Activated Alkenes. J. Org. Chem. 2016, 81, 6314–6319. 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reactions of vinylcyclopropanes and hydrosilanes promoted by silylium ion:He T.; Wang G.; Long P.-W.; Kemper S.; Irran E.; Klare H. F. T.; Oestreich M. Intramolecular Friedel-Crafts alkylation with a silylium-ion-activated cyclopropyl group: formation of tricyclic ring systems from benzyl-substituted vinylcyclopropanes and hydrosilanes. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 569–575. and references therein 10.1039/D0SC05553K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rej S.; Klare H. F. T.; Oestreich M. Silylium-Ion-Promoted Hydrosilylation of Aryl-Substituted Allenes: Interception by Cyclization of the Allyl-Cation Intermediate. Org. Lett. 2022, 24, 1346–1350. 10.1021/acs.orglett.2c00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He T.; Qu Z.-W.; Klare H. F. T.; Grimme S.; Oestreich M. Intermolecular Carbosilylation of α-Olefins with C(sp3)-C(sp) Bond Formation Involving Silylium-Ion Regeneration. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202203347 10.1002/anie.202203347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Müller T.; Meyer R.; Lennartz D.; Siehl H.-U. Unusually Stable Vinyl Cation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3074–3077. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Martens A.; Kreuzer M.; Ripp A.; Schneider M.; Himmel D.; Scherer H.; Krossing I. Investigations on non-classical silylium ions leading to a cyclobutenyl cation. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 2821–2829. 10.1039/C8SC04591G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arii H.; Kurihara T.; Mochida K.; Kawashima T. Silylium ion-promoted dehydrogenerative cyclization synthesis of silicon-containing compounds derived from alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6649–6652. 10.1039/C4CC01648C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen Y.-B.; Qian P.-C.; Ye L.-W. Bro̷nsted acid-mediated reacions of ynamides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8897–8909. 10.1039/D0CS00474J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hong F.-L.; Ye L.-W. Transition Metal Catalyzed Tandem Reactions of Ynamides for Divergent N-Heterocycle Synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 2003–2019. 10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Campeau D.; Rayo D. F. L.; Mansour A.; Muratov K.; Gagosz F. Gold-Catalyzed Reactions of Specially Activated Alkynes, Allenes, and Alkenes. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 8756–8867. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Evano G.; Coste A.; Jouvin K. Ynamides: Versatile Tools in Organic Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2840–2859. 10.1002/anie.200905817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dodd R. H.; Cariou K. Ketinimines Generated from Ynamides: Versatile Building Blocks for Nitrogen-Containing Scaffolds. Chem.—Eur. J. 2018, 24, 2297–2304. 10.1002/chem.201704689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recent examples:; a Takimoto M.; Gholap S. S.; Hou Z. Alkylative Carboxylation of Ynamides and Allenamides with Functionalized Alkylzinc Halides and Carbon Dioxide by a Copper Catalyst. Chem.—Eur. J. 2019, 25, 8363–8370. 10.1002/chem.201901153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dutta S.; Yang S.; Vanjari R.; Mallick R. K.; Gandon V.; Sahoo A. K. Keteniminium-Driven Umpolung Difunctionalization of Ynamides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 10785–10790. 10.1002/anie.201915522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c You C.; Sakai M.; Daniliuc C. G.; Bergander K.; Yamaguchi S.; Studer A. Regio- and Stereoselective 1,2-Carboboration of Ynamides with Aryldichloroboranes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 21697–21701. 10.1002/anie.202107647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szudkowska-Frątczak J.; Hreczycho G.; Pawluć P. Silylative coupling of olefins with vinylsilanes in the synthesis of functionalized alkenes. Org. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 730–738. 10.1039/C5QO00018A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vercruysse S.; Jouvin K.; Riant O.; Evano G. Copper-Catalyzed Silylcupration of Activated Alkynes. Synthesis 2016, 48, 3373–3381. 10.1055/s-0035-1562460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Timbart L.; Cintrat J.-C. Synthesis and Reactivity of an α-Stannyl β-Silyl Enamide. Chem.—Eur. J. 2002, 8, 1637–1640. and references therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito N.; Saito K.; Sato H.; Sato Y. Regio- and Stereoselective Synthesis of Tri- and Tetrasubstituted Enamides via Palladium-Catalyzed Silaboration of Ynamides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2013, 355, 853–857. 10.1002/adsc.201201111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Romain E.; Fopp C.; Chemla F.; Ferreira F.; Jackowski O.; Oestreich M.; Pérez-Luna A. Trans-Selective Radical Silylzincation of Ynamides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11333–11337. 10.1002/anie.201407002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b A stereodivergent silylzincation of ynamides giving rise selectively to Z or E β-silylenamides was later described by the same group:Fopp C.; Romain E.; Isaac K.; Chemla F.; Ferreira F.; Jackowski O.; Oestreich M.; Pérez-Luna A. Stereodivergent Silylzincation of α-Heteroatom-Substituted Alkynes. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 2054–2057. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N.; Song W.; Zhang T.; Li M.; Zheng Y.; Chen L. Rhodium-Catalyzed Highly Regioselective and Stereoselective Intermolecular Hydrosilylation of Internal Ynamides under Mild Conditions. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 6210–6216. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b00695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.; Dateer R. B.; Chang S. Borane-Catalyzed Selective Hydrosilylation of Internal Ynamides Leading to β-Silyl (Z)-Enamides. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 190–193. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansjacob P.; Leroux F. R.; Gandon V.; Donnard M. Palladium-Catalyzed Silylcyanation of Ynamides: Regio- and Stereoselective Access to Tetrasubstituted 3-Silyl-2-Aminoacrylonitriles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200204 10.1002/anie.202200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allylsilylation of alkenes:Motokura K.; Matsunaga S.; Miyaji A.; Sakamoto Y.; Baba T. Heterogeneous Allylsilylation of Aromatic and Aliphatic Alkenes Catalyzed by Proton-Exchanged Montmorillonite. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 1508–1511. 10.1021/ol100228t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allylsilylation of alkynes:Imamura K.-I.; Yoshikawa E.; Gevorgyan V.; Yamamoto Y. First Exclusive Endo-dig Carbocyclization: HfCl4-Catalyzed Intramolecular Allylsilylation of Alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 5339–5340. and references therein 10.1021/ja9803409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For a review:Motokura K.; Baba T. An atom-efficient synthetic method: carbosilylations of alkenes, alkynes, and cyclic acetals using Lewis and Bro̷nsted acid catalysis. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 565–579. 10.1039/c2gc16291a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubial B.; Ballesteros A.; González J. M. Silylium-Catalyzed Carbon–Carbon Coupling of Alkynylsilanes with (2-Bromo-1-methoxyethyl)arenes: Alternative Approaches. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 6194–6198. and references therein 10.1002/ejoc.201800777. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubial B.; Ballesteros A.; González J. M. Silylium-Catalyzed Alkynylation and Etherification Reactions of Benzylic Acetates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, e202200051and references therein 10.1002/ejoc.202200051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- See the Supporting Information for additional details.

- The presence of acidic hydrogens in the alkyl moiety opens the possibility of other transformations of silylketenimonium cation intermediate B in the same reaction conditions.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this study are available in the published article and its online Supporting Information.