Abstract

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, international higher education and student mobility have faced tremendous pressure and challenges. To address COVID-induced challenges and stress, higher education institutions and host governments undertook responses. This article has humanistically looked into the institutional responses of host universities and governments to international higher education and student mobilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Informed by a systematic literature review of publications released between 2020 and 2021 in a wide range of academic sources, we argue that many of these responses were problematic and did not adequately maintain student well-being and fairness; instead, international students were treated to some extent with poor services in the host countries. To situate our comprehensive overview and propose ideas for forward-thinking conceptualisation, policy, and practice in higher education in the context of the ongoing pandemic, we engage with the literature on ethical and humanistic internationalisation of higher education and (international) student mobilities.

Keywords: Word, International student mobility, International higher education, Humanism, COVID-19 response

Abbreviations: ISM, International Student Mobility; IHE, International Higher Education; OECD, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses

1. Introduction

In response to the increasing globalisation process, international student mobility (ISM) is a rapidly growing global phenomenon in international higher education (IHE). Globally, more than 5.6 million students are undertaking tertiary education outside their home countries [1]. This trend is so fast that it is estimated that the number of international students will be more than 8 million by 2025, according to Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] projections elsewhere [2,3]; experts in Australia, however, predict that this number will reach 15 million by 2025 [4]. This fast-growing trend of international student mobility has been dynamic, diversified, and increasingly complex [5,6]. Evidence shows that learners from 209 nations study abroad in at least 143 countries [7]. However, the top destinations of international students remain Anglophone and European countries, namely the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada [8], for varied reasons, including a desire to achieve Western-style and Western-based education [9] and considering the English language as a tool of opportunity for academic success and future career goals [10,11].

ISM has played a critical role in international higher education institutions (IHEIs) [12]. This influx of international students' mobility benefits not only international students by exposing them to new places, people, and pedagogies along with a foreign degree but also host countries in a variety of ways, including increased revenue from international student fees [13], global labour market flow [14], as a source of talent, a sign of institutional prestige, and a means of amplifying global impact [15], and the development of cosmopolitan identities that influence people's lives [16]. As a result, tertiary education institutions and their respective countries' academic reputations constantly improve worldwide [17].

The unprecedented and sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis has adversely disrupted almost all areas of human life globally, including international higher education and international student mobility and higher education institutions, governments, and their responses. However, this pandemic has created an excellent opportunity for many stakeholders to re-evaluate and redesign higher education with a successful risk-management strategy to boost the sustainability and resilience of this industry in the long run [18]. Meanwhile, some scholars have discretely focused on the impact of the pandemic on higher education in particular country contexts, such as China [19], Malaysia [20], India [21], the UK [22], Australia [23] and Canada [24], where they highlighted the educational challenges of COVID-19, the local university environment, and their reformed pedagogical and assessment responses to the pandemic and its implications for student equity in higher education. Some articles also focus on higher education responses to COVID-19 from global perspectives e.g., Refs. [[25], [26], [27]]. However, those articles viewed the higher education responses from national system perspectives, some eastern and particular western country perspectives, or a large-scale survey-based approach. Our further reading reveals that few scholars focus on international student mobility [28] or address global higher education and student mobility together [18]. For example [18], critically examine how students in Mainland China and Hong Kong conceptualise overseas study plans against the COVID-19 crisis. The study identified that the pandemic has not only significantly decreased international student mobility but is also shifting the mobility flow of international students. However, from a humanistic perspective, little attention has been paid to institutional responses to international higher education and student mobility in host countries during the COVID-19 crisis e.g. Refs. [29,30], which were and continue to be critical for international higher education during and after the pandemic, as well as the sustainability of global student mobility in western host countries. The preceding studies were conducted in the context of Asia-Pacific countries such as Brunei and Australia. As previously stated, the majority of international student mobility destinations have remained Anglophone and European countries. Scholarly works have underrepresented the responses of dominant countries, particularly Australia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada together, to the COVID-19 crisis at the start of the COVID. Specifically, little attention has been paid to academic works on the COVID-19 responses of the university and government to international students through the lens of humanism. Based on existing research, this type of academic narrative presenting the vulnerable or supportive situations that international students encounter in the above dominant host countries is required to be cautious for future students' mobility if any further crisis arises.

It is argued that during the pandemic, the issues regarding institutions' and governments' responsibilities to students facing financial and emotional challenges and physical solitude have become much more pressing. Also, the future of ISM and IHE and their goals and sustainability have been contested [31]. It is argued that it is essential to better comprehend and anticipate the shifting learning landscape in an increasingly uncertain, complex, and contradictory environment.

Against this backdrop, by systematically reviewing recently published academic articles, this paper examines the institutional responses (both university and government) to international higher education and student mobility from a global perspective, particularly key anglophone international host countries, namely Australia, the UK, the USA, and Canada, during COVID and looks at various outcomes of broad interest. This paper has viewed a historical account of institutional and government responses during COVID-19 from a humanistic lens. The humanistic lens refers to a worldview in which “the human remains at the center” [32]. In conceptualising the humanistic approach to education and its basis [8], underlines a set of fundamental ethical concepts that should serve as the foundation for a comprehensive approach to knowledge, learning, and development. These values include respect for life and human dignity, equal rights and social justice, cultural variety, a sense of shared responsibility, and a dedication to international solidarity, all of which are essential to our shared humanity. The underlying concepts of a humanistic approach to education policies must be re-contextualized [8].

From the ethos of the humanistic worldview, this paper discursively examines whether COVID-19 has a positive or negative impact on fairness and social justice with international students, as international students frequently feel marginalised and vulnerable individuals socially and academically in many institutions in host countries, and they often experience ethnic or racial tensions in global higher education [33]. Whether or not IHEIs and their governments maintained justice, equity, and sustainability and fostered individual and shared welfare [8]. Thus, this systematic review aims to determine the impact of COVID-19 on international higher education and the responses of IHIs and governments to ISM from a humanistic lens. The research questions of the paper are.

-

(1)

How did the higher education institutions and host governments respond to international students and their mobility during the pandemic?

-

(2)

How fair, inclusive and humanistic was the higher education response to international higher education and international student mobility?

In the following, the paper first presents the methodology of developing this paper. Afterwards, it presents findings under several vital themes, followed by discussions.

2. Methodology

This systematic literature review (SLR) followed the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [34,35] for selecting relevant research publications on the topic (Fig. 1). Mendeley, the reference management software, was used for preparing the online database for working collaboratively among the authors. Moreover, NVIVO 12, a qualitative data analysis software, was employed to systematically develop themes on this study's issues [36]. In the following sections, different stages of preparing this SLR paper have been illustrated.

Fig. 1.

Prisma model.

2.1. Identification

To identify relevant literature on the impact of COVID-19 on higher education, a rigorous search was conducted in 2021 to determine relevant literature on the effects of COVID-19 e-databases that include Scopus, Web of Science, Springer, and Francis & Taylor. The authors used the Boolean method on keywords in TITLE-ABS-KEY for searching articles. The keywords were “COVID-19 and “international higher education,” “impact of COVID-19″, “COVID-19,” and “international student mobility” (“International student mobility” in “higher education”, “Responses to the crisis in higher education in COVID-19”, “adaptation”, mitigation”, Adjustment”) between 2020 and 2021 with publications appeared online. The total identified publications were 1021; 720 were from Springer Link, 19 from Web of Science, 27 were from Scopus, and 255 were from Taylor and Francis (Fig. 1). All non-English papers, studies other than this study's objectives mentioned above, and studies written earlier about COVID were excluded. Therefore, the search had to be intentionally broad to capture any review related to topics, even if this included reviews that solely analysed and synthesised empirical literature on the impact of COVID-19 on higher education and international students' mobility in the world.

2.2. Screening

The extracted publications from each database were put into individual excel sheets. The screening was held in two stages: checking titles and checking duplicity. The titles on each excel sheet from the database were examined. The purpose of this early screening is to find relevance in response to the objectives of this study [37]. At this stage, 77 publications out of 1082 were recorded. All 77 publications were compiled into one excel sheet to initiate the next steps. In the second stage, 21 publications were removed from the sheet for the sake of duplicity. Finally, 56 publications were considered to be analysed to identify the answers to the study's research questions (Fig. 1).

2.3. Eligibility

After screening titles of 77 publications, 56 were downloaded and prepared in a database with Mendeley, the reference management software for assessing in response to the objectives of this study (Fig. 1). The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were followed.

2.3.1. Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria set for this study include the following.

-

•

Studies published from March 2020.

-

•

Studies published only in journals, book chapters, and conference proceedings.

-

•

Studies conducted in the form of empirical, review, and short communications

-

•

Studies conducted on the impact of COVID-19 on higher education in the local and global context

-

•

Studies conducted on the impact of COVID-19 on international student mobility in higher education

-

•

Studies published in the English language.

-

•

Studies evaluated, discussed, and explored the impact of COVID-19 on higher education from a humanistic lens.

-

•

Studies accessed full texts

2.3.2. Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded based on the following criteria.

-

•

Book, newspaper articles, summaries, abstracts, and incomplete studies.

-

•

Repeated/duplicated articles found from defined data sources, journals, and databases.

-

•

Studies reported not in the English language.

-

•

Studies not matching quality criteria.

-

•

Studies unrelated to the research questions(s)

2.4. Inclusion

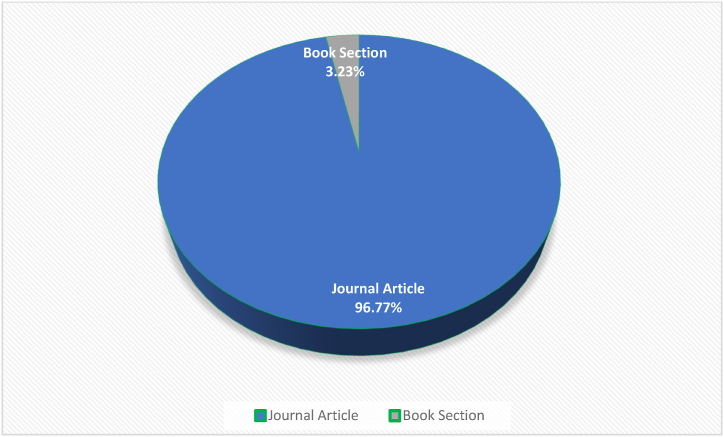

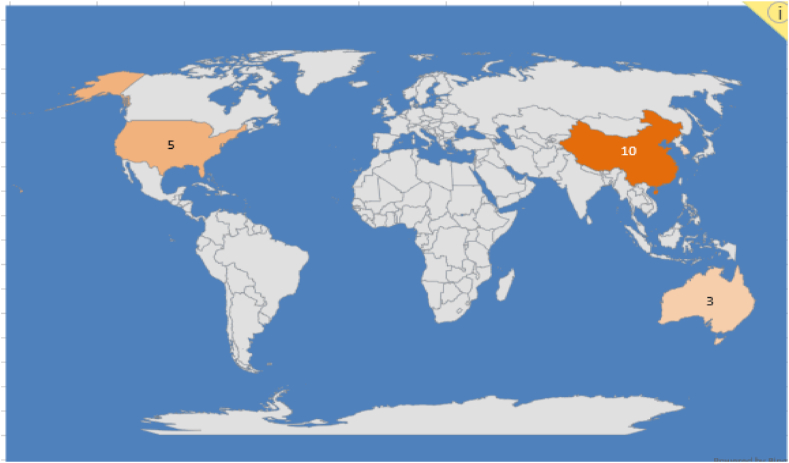

Based on the eligibility of inclusion and exclusion, 31 publications were included to respond to the study's objectives. Before analysing further, 31 publications were classified according to specific criteria of the publications. These criteria were of the publications' types, methods, and contexts. According to the classifications of the kind of publications, most publications (96.77%) were journaled articles (Fig. 2). Again, based on the methodology, the majority of the publications were conducted through qualitative research design (40%), and the least publications were held with quantitative research design (13%) (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the highest number of publications targeted China and global contexts by 32.25% each (Fig. 4). The other contexts were Australia (9.67%), and USA (16.12%), South Korea (6.45%), and New Zealand (3.22%).

Fig. 2.

Types of publications.

Fig. 3.

Methods of publications.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of contexts of publications.

2.5. Data analysis process

The data analysis process is presented in Fig. 5. After including the publications, the authors prepared a database with Mendeley Referencing software. All the publications were exported from this database as a research information system (.ris) file for importation into NVIVO, the qualitative data analysis software. By importing this ris file into NVIVO, the themes as nodes and sub-nodes were extracted from the publications to find out the answers to the research questions of this study. This systematic literature review assessed all the papers qualitatively to group themes and sub-themes textually and visually, highlighting the study objectives. Two components were examined, one mechanical and one interpretative, the first organising the data according to the study subjects and the second deciding whether data were noteworthy regarding the research objectives.

Fig. 5.

Data analysis process.

3. Results

Our systematic literature reviews identified several themes. However, this paper presents only significant themes that align with the research questions.

3.1. Sinophobia, xenophobia, racism, and discrimination

Though discrimination, xenophobia, bigotry, and violence towards international students, particularly Asian students in Western countries, are closely associated with racism and geopolitical tensions rather than directly related to students, this has been documented in the existing literature [38] in the UK [33]; in Australia [39], in the USA. Xenophobia is gradually becoming a source of security worries for international students [40]. The situation deteriorated further during the COVID-19 outbreak. Because of “mask phobia,” racist attacks on Asian students have grown, with some students wearing masks becoming targets of abuse. Most of the papers in our reviews addressed this critical issue associated with international student mobility and IHE.

Because COVID-19 was perceived as a Chinese virus, it became increasingly common for international students, mainly Asian international students, to face racism, intolerance, and discrimination. Xenophobic behaviour, language, microaggressions, and targeted threats were prevalent among international slabelledtudents [41]. While strolling along the street, they have been spat on, yelled at with racist obscenities, and told to “go home” in many western host countries. Students' psychological well-being, mental health, social isolation, and physical safety were all negatively affected by racial tensions. Evidence of prejudice and hostility moved off campus [42], delivering unpleasant messages and creating stress among students seeking a sense of belonging and support that most host community institutions could not supply. Only a few community colleges have dedicated workers to help international students cope with institutional racism. Those who were subjected to such acts of racism faced incredibly high levels of mental stress, social anxiety, prejudice, and insecurity. Some people were hesitant to leave their homes due to circumstances [43].

Surprisingly, during Sinophobic exchanges, formal identification of a Chinese-looking person's citizenship status is rarely made. Instead, casual visual racial profiling, which detects one's racial identity based on physical appearance, is used to select the victim. Residents of the area who are ethnically Chinese are occasionally shunned, even if they have never visited China. Because of their physical resemblance to the Chinese, the conflation increased Sinophobia and discrimination against East Asians in general. For instance, a gang of youngsters in London assaulted a Singaporean student they mistook for a Chinese national [44]. Anti-Asian attacks and viral acts of violence escalated to the point where several host nations, particularly the United States, were labelled as dangerous places for Chinese students [45].

The coronavirus was thought to have been used to tag Chinese people for political reasons. The growth of nationalist ideology in the Trump administration blamed and victimised these students, refugees, and immigrants [46]. This politically motivated hostility directly affected Chinese people living in other countries. Chinese students studying overseas were subjected to unfavourable treatment, and wearing a mask as self-defence is frowned upon. Racism and xenophobia were blamed on cultural differences, while others blamed racial nationalism and xenophobia. The “triple conflation” condition occurred when Chinese people's health, racial, and political/national identities became mixed up [44]. Sinophobic rhetoric has highlighted an increasing perception of China as a threat. One Instagram user jokes that the coronavirus “will not last long because it's made in China,” implying a link between the virus and China's manufacturing capabilities. Hence, Sinophobic rhetoric can be seen as a result of the ongoing trade war between the United States and China [44].

International students were more exposed to these attitudes and actions than ever before and were advised to remain calm and sensible. Fortunately, as the pandemic spread worldwide, more people became aware of the significance of wearing masks and realised that COVID-19 is not a “Chinese virus.” Students' decisions to study in the United States for in-person classes or return to China and risk a lower quality education due to online courses were influenced by safety concerns. Anxieties developed primarily due to a lack of understanding of the university's security measures. Safety concerns influenced students' judgments on whether to study in the United States or return to China. Inconsistencies in safety equipment requirements, such as masks, raised many eyebrows. Differences influenced the participants' and their families' decisions regarding the restrictions [47].

Some of the literature presented suggestions to lessen students' vulnerability, emphasising the importance of HEIs broadening their spectrum of support by providing suitable security and protection to both outgoing and incoming international students. This framework's accountability issues should be viewed as “mutual issues” between HEIs, relevant agencies, and students. The paper by Ref. [12] highlights a unique mobility experience in which international students participated in social and community activities outside of the campus, which coincides with the internationalisation of higher education. This activity has greatly impacted the students' growth and transformations. On the one hand, it represents new narratives of desires and possibilities in the arena of inter-Asian mobility; on the other, their intercultural skills significantly reduce the safety and well-being concerns connected with international student mobility [12]. It was also proposed to incorporate racial and xenophobic issues in faculty development, curricular reform, and pedagogical program design to reduce racial conflict in the host society and make the international education experience more comfortable for international students. Microaggressions are needed to emphasise and provide a decolonised context for the curriculum and host-country culture [41].

3.2. Border closure, travel bans/restrictions, and pushback: Student's (im)mobility and sufferings

When the Coronavirus spread rapidly worldwide, host country governments and host universities directly or indirectly forced international students to return home. International students could not return home due to cancelled flights and restricted borders and were stranded in host nations. Authorities acted inhumanely by paying little attention to how good or bad the situation was for international students. These activities can be viewed as a substantial authoritarian move diminishing human rights [48]. reported that international students who were unable to return to their home countries, homeless students, and students with health or safety concerns were prioritised at Stanford and Cornell. Likewise, for international students who desired to return home, in many cases, their home country governments supported them in transition (e.g., Singapore, Bangladesh, Thailand, and Indonesia). However, only a few host countries came forward in this regard. According to Ref. [29], the Brunei Prime Minister's Office issued a directive to aid this transition and/or visa extension while international students in other major host countries faced significant immigration issues [48].

This border closure, travel bans or restrictions, campus shutdowns, and pushback had several consequences, as reflected in some of our reviewed articles. Travel restrictions and/or prohibitions, airline cancellations, and route closures severely hampered international student mobility [49]. Due to the travel ban, millions of students could not begin or continue their studies overseas. Some students were permitted to go to host nations via Southeast Asia (for example, Australia). These steps taken by the Australian government were criticised, with some arguing that Australia externalised the risks involved with selling educational services while keeping the earnings by allowing Chinese students to enter only after a transit stay (Haugen, Heidi Østbø; Lehmann, Angela, 2020).

Furthermore [29], illustrated how international students who arrived in host countries confronted several complicated issues. The crucial question was whether they should stay and finish their education in the host country or return home to be with their family. If they opted to stay, would they be able to cope emotionally and financially if things went wrong? Many international students decided to quit or postpone their ambitions to study abroad, according to Kanwar and Carr (2020). Students who returned home usually lacked the resources they needed to complete their studies. The shift toward online schooling exacerbated inequity as more students became part of the digital divide [41]. Due to increased restrictions, many overseas students decided to postpone or cancel their study abroad plans. Not all countries, however, closed their doors. For example, the Republic of Korea's relatively successful pandemic containment allowed borders to remain open and no countrywide lockdowns to date, allowing student movement throughout the epidemic [42].

In the second year of COVID-19, the world was dealing with the pandemic, resulting in fears among international students about returning to their study places. New lockdowns were in place on college campuses to prevent the spread of a new strain of COVID-19. To avoid the spread of the current variant of the coronavirus, the host country continued to enforce health and safety measures as well as travel limitations. Countries that admit international students have set specific requirements, like obtaining a COVID-19 test result that is negative or having certain vaccinations completed. Even after arriving at their destination, the students had to remain separated for a certain number of days and pay for additional coronavirus tests to certify COVID negativity. If they tested positive for COVID in these tests, they had to self-isolate for an additional number of days. A case study describes exchange students' arrival and quarantine experiences at a university in Seoul, Korea. Students' opinions and expectations of Korea as a safe study location were juxtaposed with harsh and chaotic arrival experiences during the pandemic [42]. The host governments' responses and attitudes toward international students throughout the pandemic harmed several host nations' reputations [42].

3.3. Financial anxieties and little support from universities and governments

As mentioned, COVID-19 had a variety of effects on ISM and IHE. Our systematic review shows that the pandemic severely affected students' employment, recruitment, and financial ability, which are common issues in IHE. Many international students lost their part-time jobs or put their ambitions to find part-time jobs on hold due to the COVID-19 epidemic's lockdowns and social-distancing (stay-at-home) guiding philosophy. According to Ref. [43], campus lockdowns also robbed international students of on-campus jobs, which were a source of financial support. In such circumstances, international students expected their host university to provide valuable measures to assist them in getting out of a financial bind while also caring for their mental health and well-being. Nevertheless, university help for students was insufficient and, in some cases, even increased the level of anxiety. Some universities refused to decrease or freeze fees for international students who lost part-time jobs, forcing them to rely on local charities for food and accommodation [50].

The significance of host country governments and universities in helping international students was highlighted in several papers [29,43]. Ref [29] described that during the pandemic, the University Brunei Darussalam (UBD) aided international students by providing “full administrative and academic assistance,” regular medical care, a generous “free meal system,” and high-quality housing. Similarly, universities in other host nations, such as Charles Darwin University in Australia and the University of Central Florida in the United States, assisted overseas students with housing issues and financial, social, and emotional assistance.

The function of Australian state governments in providing financial aid to international students was described by Ref. [43]. As the pandemic spread worldwide, they claimed that Australia's global education industry suffered greatly. The federal government failed to allocate any cash to help international students. Scott Morrison, Australia's Prime Minister, recommended international students “go home” if they could not pay. Many saw the Prime Minister's comments on international students as “cash cows” and an unnecessary burden on the Australian population. International students have unquestionably contributed to Australia's efforts to provide for society, from healthcare to replenishing grocery shelves. On the other hand, international students have struggled to cover basic needs like paying for housing and food since the pandemic began [43].

Furthermore, according to Ref. [43], not all state governments were as kind or supportive of international students. They were not all as prompt in disbursing humanitarian funds. International students were left to fend for themselves for more than a month without government aid. Only students in desperate situations were eligible for assistance. However, they had to submit bank statements as proof of their inability to pay rent to get rental help or prove that they needed welfare benefits. The evaluation process took a long time, with a considerable wait period and inconsistent outcomes.

On the other hand, international students began to receive free food or coupons from local governments, community organisations, and ethnic eateries later. The authors above described an inhumane situation in Australia, where support for international students was manifestly out of proportion to the billions of dollars they provided to the country's economy. Even though they are taxpayers, international students are ineligible for programs like JobKeeper and JobSeeker.

Some international students could not support their funding applications with formal employment records or superannuation accounts. These were the most vulnerable people, and it looked like relief efforts would be ineffective until financial assistance reached those who needed it most. As a result, overseas students who had lost their job and had no other means of paying their rent would be practically homeless while waiting for funds to arrive. Many students were left trapped, unable to manage their education while dealing with the stress and anxiety of financial concerns [41,43].

In her paper [51], discussed the government's response to the crisis. Governments react to emergencies differently, from deliberate denial or crisis non-recognition to partially or entirely blaming non-government interests. The degree of centralisation varied depending on the state's form and the interests represented at each level of government.

3.4. The possible financial impact on HEIs and the country's economy

The pandemic's impact on higher education around the world took several forms. Many universities, which rely heavily on international students' fees, predicted that national economies would suffer if students stayed in their home countries. COVID-19 was expected to have a more significant and long-lasting economic impact on HE than the 2008 financial crisis. In the United States, around 800 higher education institutions were likely to lose 20% of their revenue, with one out of every five colleges facing closure. In the worldwide higher education industry, Chinese students are critical. Because of anti-Chinese prejudice and bigotry, COVID-19 broke Western schools' reliance on Chinese students as a source of revenue. The annualised international student fee income of around $8 billion in the UK and $4–6 billion in Australia was at risk if Chinese students could not attend the first term of the 2020–21 academic year. On the other hand, ESL classes, which generate additional revenue for the college, could not be filled because international students were forced to return home. Higher education was included in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act in the United States, which allocated $12.5 billion to help the HE sector, with half of the money going to students [41,52].

Because of the potential financial loss, numerous higher education institutions took the initiative to cut their costs. All international travel, including visits to other countries and international high schools, was halted in this process. Due to financial constraints, professional memberships and conference attendance were reduced. Many budgets were lowered to the point where offices had to close, or employees had to relocate [41].

3.5. International student mobility shifting from west to the east

Some notable global higher education experts projected that the general mobility direction of international students to western universities might be shifted and could be redirected to eastern universities, particularly in China and other Asian countries. Education leaders also assumed that after the COVID-19 world, international student mobility to western universities would decrease, and more students would study close to home [53]. Ref [54] states that a coronavirus-induced recession would disproportionately afflict developing countries. If the global middle class diminishes briefly, it would considerably influence international student flows to Western universities. Following the outbreak, 84% of the 2739 people polled claimed they had no interest in studying abroad. Apart from the United States and the United Kingdom, Asian regions and countries are among the top five destinations for students to further their education overseas [18,54].

4. Discussions

This paper examines higher education and the government's response to international higher education and student mobility through the lens of humanism in the COVID-19 context. According to the systematic literature review, the coronavirus considerably affects international higher education and student mobility, and both are vulnerable, concerned, and uncertain during the COVID-19 health emergency. Stranded in one's home country or host country due to a travel ban, being forced to return home, racial discrimination in host countries and the uncertainty of financial ability with little support from host HEIs and governments are just some of the vulnerabilities, problems, and certainties. On the one hand, the uncertainties and hazards faced by international students during COVID-19 were problematic and ethically ambiguous.

While travel bans for international students, college closures, and a drive to return home may be justified on nationalistic and health grounds, other state government and university actions may be unethical. It goes against reciprocity and hospitality ideals. International students are treated as academic guests in host countries. The host country must provide appropriate hospitality to the academic visitors [55]. Nonetheless, the state governments and IHIs have failed to do so extensively. Instead of being flexible, patient, and empathic with students' specific cases and situations in order to shield themselves from the coronavirus, governments and IHIs turned selfish. As a result, people from all walks of have expressed dissatisfaction. For example, interim vice chancellor Jane den Hollander of the University of Western Australia claimed the Australian Premier's “unhelpful” words would send an “unwelcome” signal and hinder Australia's post-pandemic recovery [56].

It appears that universities protect their students in good times. However, it increasingly appears that they take care of themselves in difficult times, according to a director of studies at Cambridge. Students and their representatives also expressed their dissatisfaction. Many international students, who lost their part-time job owing to national coronavirus restrictions, thought the Premier's advice was “unrealistic” and “unethical.” The Council of International Students Australia (CISA) is also concerned about Australia as a destination for international students in the future. It poses questions about why international students should consider coming here when current students are treated poorly. According to Northern Territory Chief Minister Michael Gunner, the challenge overseas students face is that many international students have “fallen between the cracks.” “They can't find work right now, and they just cannot.” They can't travel home since the airlines have stopped flying, and their parents are likely in financial trouble wherever the family stays [58].

According to academics, neoliberalism has turned international higher education into a big industry [4]. In 2015–16, international students contributed US $32 billion to the global economy, a figure that is expected to rise to US $1 trillion in the next ten years [3] This money comes from fee-paying international students and is used to help local economies see Refs. [59,60]. For many overseas students who sought admission to western universities out of a desire for recognition, international education has also become a branded good, resulting in their goods (education) being overvalued in the market. International students have become a “cash cow” for western colleges and destination nations, yet these establishments routinely underserve them. Instead, they confront persecution, bigotry, and uncertainty in several host countries, which may impact ISM and higher education long-term. According to the New Zealand International Students' Association, international students are considered “cash cows” in New Zealand higher education (NZISA).

This opinion of a cash cow is aligned with the previous research before the pandemic, which reveals that higher education institutions and governments do not provide adequate support to international students, who are treated as aliens with limited rights despite being an essential part of any institution's internationalisation effort and are classified as non-citizens and temporary migrants [61,62]. IHIs and governments frequently overlook or neglect international students [15,63], and international students are commonly treated as cash cows with poor services [64,65] providing resources to enable economic advantage [[66], [67], [68]] from international student fees [13]. In other words, IHE in the global north is considered a mechanism for governments to earn funds to offset dwindling public funding [69]. Others may argue that because international students are not funded by home taxpayers, they must pay the full economic cost of their education at foreign institutions. According to NZISA, universities are responsible for serving international students efficiently. If they fail to do so, they will violate an international educational code of practice [57]. As a result, although international student mobility benefits host countries' economies and cultures, few host countries worked hard to ensure international students' well-being during the COVID-19 crisis.

However, the existing literature also reveals that IHE played a very supportive role during the previous crisis period in reacting to refugee crises in general and the Syrian refugee crisis in Europe [70,71], where several methods existed for governments, higher education as a sector, and individual universities to respond constructively to the influx of immigrants. This form of humanitarian aid is required for international students arriving in their host nations, which governments, institutions, and individuals can provide through soft power. Indeed, some universities offer such services, which have the potential to benefit both host and home societies. However, during the early stages of the pandemic, this type of humanitarian assistance in crisis management was insufficient in some universities in western host countries. It is believed that during a crisis, HEIs' and host governments' policies and responses to foreign education can make a significant difference for this vulnerable group [72].

According to literature from a justice and equity perspective, international students face stress, anxiety, challenges, and vulnerability due to a variety of issues, including academic and financial difficulties, housing, jobs, visas, homesickness and loneliness, exploitation, abuse, and discrimination at work and in the private sector [73,74]. Cultural hostility, prejudice, abuse, racial discrimination, and exploitation [75]; Ramia, Marginson, and Sawir, 2013 [74]; are highly rated challenges that occur outside of the university, primarily on the street, public transportation, and stores, and which profoundly affect international students and make them feel alienated [74,75]. Due to the emergence of the coronavirus in several novel forms, these issues of vulnerability and insecurity, as well as the question of rights, accountability, justice, equity, and the well-being of international students in higher education, have risen in western and eastern countries. It may raise ethical questions about governments' and universities' obligations to international students [11]. wonder if international higher education is merely for profit or more than that, with governments and universities bearing moral and ethical duties for overseas students' well-being.

Based on data from a study in Western society, it is argued that the rise in attacks against “Asian-looking people” is deeply rooted in Western cultures and civilisations’ historical prejudice against Chinese and Asians [76]. Experts are encouraging universities in Europe, North America, and Australia to do more to protect Asian students, as well as other students, by establishing, expanding, or improving academic and psychological support for all students [[76], [77], [78]]. In their consideration, discrimination and xenophobia have been identified as sad indictments of socially aware people in the twenty-first century. It has been suggested that diversity issues be included in the curriculum to prevent discrimination [78].

5. Conclusion

The coronavirus epidemic has undoubtedly produced unprecedented uncertainty, tensions, anxiety, and concerns about international student mobility, the international student market, financial stability, and global higher education in general. The coronavirus has a short-, medium-, and long-term impact. By reducing reliance on international students, lowering their tuition fees, legislating international student safety and security, and providing high-quality online delivery, now is the time to develop strategic action plans to address this critical issue and ensure the long-term viability of international higher education and student mobility. The government, universities and students must work together to support one another.

The coronavirus outbreak has taught us numerous lessons. This epidemic teaches us how to deal with global health crises and manage education with limited resources, which will become a new model for the global economy and higher education. In addition, this crisis has demonstrated the importance of contingency planning and risk management to better prepare universities for high-risk emergencies [79], as well as the benefits of supporting novel delivery methods and the need for flexibility. COVID-19 has brought about a new world order that requires a shift in perspective and new ways of thinking [80]. The epidemic has increased the importance of ethical issues, raising concerns about the host and home governments' responsibilities and university enrollment. Universities with a more flexible and humanistic attitude, educational delivery modes, and robust intercultural communication and counselling systems clearly needed to deal with the coronavirus epidemic at the time.

The limitation of this paper is that it has presented the university and government response to the only early-stage crisis of COVID-19, which was very severe and unfamiliar to IHE and the government. Secondly, it is a review paper developed based on the existing academic works published between 2020 and 2021. Despite the limitations mentioned above, this paper provides a better understanding of the vulnerable situation in which international students found themselves in dominant host countries. This paper also provides IHE stakeholders with a better understanding of the vulnerable situation that international students face in dominant host countries. This paper presents the COVID crisis as a wake-up call [30] and argues that the pandemic taught us that IHE should be first and foremost about people (students) and for people with humanism, and this very humanistic internationalisation is what we uphold, build, and strive for [29]. UN Sustainable Development Goal 4 emphasises learning flexibility by offering various pathways and support to diverse learners to provide access and equity for all. As a result, future higher education must be more adaptable, flexible, and humanistic [81].

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This study did not receive any funds from any institutions. But, the authors are grateful to Senior Professor Phan Le Ha, Universiti Brunei Darussalam for her guidance and mentoring in writing this article.

Data availability statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.

Declaration of interest's statement

The authors declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Mohammod Moninoor Roshid, Email: moninoor@du.ac.bd, moninoor.roshid@ubd.edu.bn.

Prodhan Mahbub Ibna Seraj, Email: mahbub.seraj@aiub.edu, mahbubutm@gmail.com.

References

- 1.UNESCO . 2019. Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students.http://uis.unesco.org/en/uis-student-flow Retrieved. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ICEF Monitor . 2017. OECD Charts a Slowing of International Mobility Growth.https://monitor.icef.com/2017/09/oecd-charts-slowing-international-mobility-growth/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis M.J. University World News; 2018. A New Age in International Student Mobility.https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20180605103256399 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altbach P.G., Knight J. The internationalization of higher education: motivations and realities. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2007;11(3–4):290–305. doi: 10.1177/1028315307303542. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu M., Le Ha P. We have no Chinese classmates”: international students, internationalization, and medium of instruction in Chinese universities. Aust. Rev. Appl. Ling. 2021;44(2):180–207. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phan l.H., Fry G.W. 2021. International Educational Mobilities and New Developments in Asia's Higher Education: Putting Transformations at the Centre of Inquiries. Comparative and International Education. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.UNESCO Institute for Statistics Data center: student mobility country of origin, 1999 e 2013. 2018. http://data.uis.unesco.org/ Available at:

- 8.UNESCO . UNESCO; 2015. Rethinking Education: towards a Global Common Goods.https://unevoc.unesco.org/e-forum/RethinkingEducation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phan L.H. Higher education, English, and the idea of ‘the West’: globalizing and encountering a global south regional university. Discourse: Stud. Cult. Polit. Educ. 2018;39(5):782–797. doi: 10.1080/01596306.2018.1448704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marginson S. Student self-formation in international education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2014;18(1):6–22. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sawir E., Marginson S., Forbes-Mewett H., Nyland C., Ramia G. International student security and English language proficiency. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2012;16(5):434–454. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kumpoh A.A.Z.A., Sulaiman E.A., Le Ha P. Insights into Bruneian students' transformative mobility experiences from their community outreach activities in Vietnam. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2021;16(3):228–251. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bessant S.E., Robinson Z.P., Ormerod R.M. Neoliberalism, new public management and the sustainable development agenda of higher education: history, contradictions and synergies. Environ. Educ. Res. 2015;21(3):417–432. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kahanec M., Králiková R. 2011. Pulls of International Student Mobility.https://ssrn.com/abstract=1977819 IZA Discussion Paper No. 6233, Available at SSRN: [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marginson S. Including the other: regulation of the human rights of mobile students in a nation-bound world. High Educ. 2012;63:497–512. doi: 10.1007/s10734-011-9454-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tran L.T. British Journal of Sociology of Education; 2015. Mobility as ‘becoming’: a Bourdieuian Analysis of the Factors Shaping International Student Mobility; pp. 1–22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.OECD . OECD Publishing; 2007. Education at a Glance, 2007: OECD Indicators. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mok K.H., Xiong W., Ke G., Cheung J.O.W. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on international higher education and student mobility: student perspectives from mainland China and Hong Kong. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2021;105(August 2020) doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang R. China's higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: some preliminary observations. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2020;39(7):1317–1321. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sia J.K.M., Adamu A.A. Asian Education and Development Studies. 2020. Facing the unknown: pandemic and higher education in Malaysia.https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/AEDS-05-2020-0114/full/html [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahoo K.K., Muduli K.K., Luhach A.K., Poonia R.C. Pandemic COVID-19: an empirical analysis of impact on Indian higher education system. J. Stat. Manag. Syst. 2021;24(2):341–355. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsiligkiris V., Ilieva J. Global engagement in the post‐pandemic world: challenges and responses. Perspective from the UK. High Educ. Q. 2022;76(2):343–366. [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Shea S., Koshy P., Drane C. The implications of COVID-19 for student equity in Australian higher education. J. High Educ. Pol. Manag. 2021;43(6):576–591. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metcalfe A.S. Visualizing the COVID-19 pandemic response in Canadian higher education: an extended photo essay. Stud. High Educ. 2021;46(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bajaba S., Mandurah K., Yamin M. A framework for pandemic compliant higher education national system. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2021;13(2):407–414. doi: 10.1007/s41870-021-00629-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma G., Black K., Blenkinsopp J., Charlton H., Hookham C., Pok W.F.…Alkarabsheh O.H.M. Higher education under threat: China, Malaysia, and the UK respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. Compare. 2022;52(5):841–857. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marinoni G., Van’t Land H., Jensen T. The impact of Covid-19 on higher education around the world. IAU Global Survey Report. 2020;23 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yıldırım S., Bostancı S.H., Yıldırım D.Ç., Erdoğan F. Higher Education Evaluation and Development; 2021. Rethinking Mobility of International University Students during COVID-19 Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keasberry C., Phan L.H., Roshid M.M., Iqbal M.A. Globalisation, Education, and Reform in Brunei Darussalam. Palgrave Macmillan; Cham: 2021. Student experiences during COVID-19: towards humanistic internationalisation; pp. 393–413. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le A.T. Support for doctoral candidates in Australia during the pandemic: the case of the University of Melbourne. Stud. High Educ. 2021;46(1):133–145. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Green W., Anderson V., Tait K., Tran L.T. Precarity, fear and hope: reflecting and imagining in higher education during a global pandemic. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2020;39(7):1309–1312. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1826029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quinn J. A humanist university in a posthuman world: relations, responsibilities, and rights. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 2021:1–15. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2021.1922268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pham L., Tran L. Understanding the symbolic capital of intercultural interactions: a case study of international students in Australia. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 2015;25(3):204–224. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ibna Seraj P.M., Habil H. A systematic overview of issues for developing EFL learners ’ oral English communication skills. J. Lang. Educ. 2021;7(1):229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zulkarnaen R.H., Setiawan W., Rusdiana D., Muslim M. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Vol. 1157. IOP Publishing; 2019, February. Smart city design in learning science to grow 21st century skills of elementary school student. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Y., Watson M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plann. Educ. Res. 2019;39(1):93–112. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown L., Jones I. Encounters with racism and the international student experience. Stud. High Educ. 2013;38(7):1004–1019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yeo H.T., Mendenhall R., Harwood S.A., Huntt M.B. Asian international student and Asian American student: mistaken identity and racial microaggressions. J. Int. Stud. 2019;9(1):39–65. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Forbes-Mewett H. Vulnerability and resilience in a mobile world: the case of international students. J. Int. Stud. 2020;10(3):ix–xi. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raby R.L., Zhang Y.L. Learning from COVID-19: challenges and opportunities for international education in community colleges. Community Coll. J. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2021.1961924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stewart W.H., Kim B.M. Commitment to academic exchanges in the age of covid-19: a case study of arrival and quarantine experiences from the Republic of Korea. J. Int. Stud. 2021;11(2):77–93. doi: 10.32674/JIS.V11IS2.4110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nguyen O., Olena) T.K., Balakrishnan V.D. International students in Australia–during and after COVID-19. High Educ. Res. Dev. 2020;39(7):1372–1376. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2020.1825346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gao Z. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science; 2021. Sinophobia during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Identity, Belonging, and International Politics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen R.M., Ye Y. Why deteriorating relations, xenophobia, and safety concerns will deter Chinese international student mobility to the United States. J. Int. Stud. 2021;11(2):I–VII. doi: 10.32674/jis.v11i1.3731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yacoub A.R., El-Zomor M. The Short-Term and Long-Term Impact of COVID-19 on Globalization. 2020. Would COVID-19 be the turning point in history for the globalization era? [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xu Y., Gibson D., Pandey T., Jiang Y., Olsoe B. The lived experiences of Chinese international college students and scholars during the initial COVID-19 quarantine period in the United States. Int. J. Adv. Counsell. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10447-021-09446-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ye R. Testing elite transnational education and contesting orders of worth in the face of a pandemic. Educ. Rev. 2021:1–16. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2021.1958755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mercado S. International student mobility and the impact of the pandemic. BizEd: AACSB International. 2020;11 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan B.C., Baker J.L., Bunagan M.R., Ekanger L.A., Gazley J.L., Hunter R.A., O'Connor A.R., Triano R.M. Theory of change to practice: how experimentalist teaching enabled faculty to navigate the covid-19 disruption. J. Chem. Educ. 2020;97(9):2788–2792. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramia G. Crises in international education, and government responses: a comparative analysis of racial discrimination and violence towards international students. High Educ. 2021;82(3):599–613. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00684-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Purcell W.M., Lumbreras J. Higher education and the COVID-19 pandemic: navigating disruption using the sustainable development goals. Discover Sustainability. 2021;2(1) doi: 10.1007/s43621-021-00013-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marginson S. Times Higher Education; 2020. Global HE as We Know it Has Forever Changed.https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/global-he-we-know-it-has-forever-changed [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pan S. COVID-19 and the neo-liberal paradigm in higher education: changing landscape. Asian Educ. Develop. Stud. 2021;10(2):322–335. doi: 10.1108/AEDS-06-2020-0129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ploner J. International students' transitions to UK Higher Education–revisiting the concept and practice of academic hospitality. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2018;17(2):164–178. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ross J. Times Higher Education; 2020. New Zealand Students Protest Coronavirus Entry Ban ‘overreach’.https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/students-protest-coronavirus-ban-over-reach [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ross J. Times Higher Education; 2020. Time to Go Home’, Australian PM Tells Foreign Students.https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/time-go-home-australian-pm-tells-foreign-students?fbclid=IwAR33B2vxRDD8Oo0udEcqSJB96gV0eGmwcuOTUCJQanFxE_FKMIXpmfbJ-QE [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gibson J., Moran A. ABC News; 2020. As Coronavirus Spreads, 'it's Time to Go Home' Scott Morrison Tells Visitors and International Students.https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-03/coronavirus-pm-tells-international-students-time-to-go-to-home/12119568 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gribble C. Policy options for managing international student migration: the sending country's perspective. J. High Educ. Pol. Manag. 2008;30(1):25–39. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ortiz A., Chang L., Fang Y. University World News; 2015. International Students Bring Money, Skills and Jobs.https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20150212092452773 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chowdhury R., Le Ha P. Multilingual Matters; 2014. Desiring TESOL and International Education. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Marginson S., Sawir E. In: Social Policy Review 23: Analysis and Debate in Social Policy. Holden C., Kilkey M., Raima G., editors. Policy Press; 2011. Student security in the global education market; pp. 281–302. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sawir E., Marginson S., Nyland C., Ramia G., Rawlings-Sanaei F. The social and economic security of international students: a New Zealand study. High Educ. Pol. 2009;22(4):461–482. doi: 10.1057/hep.2009.4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Choudaha R. Are international students “cash cows”. Int. Higher Educ. 2017;90:5–6. doi: 10.6017/ihe.2017.90.9993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ziguras C., McBurnie G. Higher Education in the Asia-Pacific. Springer; Dordrecht: 2011. International student mobility in the Asia-Pacific: from globalization to regional integration? pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stein S., de Andreotti V.O. Cash, competition, or charity: international students and the global imaginary. High Educ. 2016;72(2):225–239. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9949-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yao C.W., Viggiano T. Interest convergence and the commodification of international students and scholars in the United States. J. Commit. Soc. Change on Race and Ethnicity. 2019;5(1):81–109. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yao C.W., Mwangi C.A.G. Yellow Peril and cash cows: the social positioning of Asian international students in the USA. High Educ. 2022:1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00814-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stein S., Andreotti V., Suša R. Pluralizing frameworks for global ethics in the internationalization of higher education in Canada. Can. J. Higher Educ. 2019;49(1):22–46. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Streitwieser B., Brück L. Competing motivations in Germany's higher education response to the “refugee crisis”. Refuge: Canada's J. Refugees/Refuge: revue canadienne sur les réfugiés. 2018;34(2):38–51. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Streitwieser B., Miller-Idriss C. The Globalization of Internationalization. Routledge; 2017. Higher education's response to the European refugee crisis: challenges, strategies and opportunities; pp. 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Qi J., Ma C. Australia's crisis responses during COVID-19: the case of international students. J. Int. Stud. 2021;11(S2):94–111. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andrade M.S. International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2006;5(2):131–154. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sherry M., Thomas P., Chui W.H. International students: a vulnerable student population. High Educ. 2010;60(1):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee J.J., Rice C. Welcome to America? International student perceptions of discrimination. High Educ. 2007;53(3):381–409. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lay J. Times Higher Education; 2020. Coronavirus Sparks a Rising Tide of Xenophobia Worldwide.https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/coronavirus-sparks-rising-tide-ofxenophobia-worldwide [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brown C., Salmi J. University World News; 2020. Putting Fairness at the Heart of Higher Education.https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200417094523729 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wen J., Aston J., Liu X., Ying T. Effects of misleading media coverage on public health crisis: a case of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in China. Anatolia. 2020;1–6 doi: 10.1080/13032917.2020.1730621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hommel U. University World News; 2020. Universities Need to Prepare Better for High Risk Crises.https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200302103912399 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dennis M. University World News; 2020. How Will Higher Education Have Changed after COVID-19?https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200324065639773 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martin M., Furiv U. University World News; 2020. COVID-19 Shows the Need to Make Learning More Flexible.https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20200324115802272 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.