Abstract

Introduction:

Group well-child care (GWCC) is an alternative to traditional pediatric well-child care designed to increase parental social support and peer learning. This mixed methods study explored the adaptation and implementation of GWCC to a virtual format during COVID-19 among Spanish-speaking Latino immigrant families.

Methods:

Interviews were conducted with 8 providers and 10 mothers from May-September 2020. Qualitative analyses used a priori codes based on an implementation science framework. Quantitative data included demographics, the COVID-19 Impact Scale, and virtual group attendance. Bivariate analyses identified correlates of virtual visit attendance.

Results:

80% of mothers reported the pandemic had moderately or extremely impacted at least one major life domain such as daily life, food security, or family conflict. Of 27 mothers offered virtual groups, 67% attended. Mothers who attended virtual groups reported lower English proficiency (p=0.087) and fewer friends and family members with COVID-19 (mean=1.0 vs 5.1, p<.05) than those who did not attend. Women described virtual GWCC as acceptable and a source of social support. Some described differences in group dynamics compared to in-person groups and had privacy concerns. Providers noted scheduling and billing challenges affecting feasibility and sustainability. They reported that visits with good attendance were productive. Mothers and pediatric providers offered recommendations to improve feasibility and privacy and address sustainability.

Discussion:

Competing demands for those most impacted by COVID-19 may outweigh benefits of attendance. Virtual Spanish language GWCC appears acceptable and feasible for Spanish speaking Latina mothers. Thematic analysis and recommendations identify areas of improvement.

Keywords: immigrant health, Latino health, pediatric integrated care, telehealth, two-generation approaches to health

Introduction

There is concern that traditional well-child care models do not adequately meet the needs of families experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage (Schor, 2004). Group well-child care (GWCC) is one form of redesign incorporating a two-generation approach, focusing on core family functioning components such as maternal well-being, parenting education, and support (Connor et al., 2017; Graber et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2018; Oldfield et al., 2019). In GWCC, the traditional 15–20 minute individual visit is replaced by a 90–120 minute visit in which 6–10 families with same-age infants participate in brief individual visits and a group discussion (Oldfield et al., 2020). GWCC has been shown to improve visit attendance (Gullett et al., 2019), timeliness of immunizations (Irigoyen et al., 2020), and parent satisfaction (Jones et al., 2018), as well as clinicians’ perceptions of meeting families’ needs (Desai et al., 2019). GWCC was recommended as culturally effective for children in immigrant families (Cheng et al., 2015).

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted families with young children, presenting numerous risks to well-being including food insecurity, decreased healthcare utilization, and school interruptions (Bauer et al., 2021; Gassman-Pines et al., 2020; Santoli et al., 2020). These challenges are compounded for Latino families, especially those with immigrant parents, due to structural factors that place this population at higher risk both for COVID-19 infection (Figueroa et al., 2020; Galvan et al., 2021; Hernandez-Vallant A, 2020; Rodriguez-Diaz et al., 2020) and pandemic-related economic insecurity, childcare issues, and psychological distress (Vargas & Sanchez, 2020).

Little is known about whether and how pediatric practices delivering GWCC to Spanish-speaking immigrant families adapted the model for virtual implementation, or the impact of these adaptations on implementation outcomes (e.g., feasibility, acceptability). Such outcomes are critical for evaluating new healthcare practices. Therefore, guided in part by Proctor and colleagues’ established “taxonomy of implementation” (Proctor et al., 2011; Proctor et al., 2009), we investigated 1) predictors of virtual GWCC attendance (e.g., baseline characteristics, COVID-19’s impact on families), 2) stakeholder (e.g., parent, provider) perspectives on virtual GWCC implementation during COVID-19, and 3) stakeholder recommendations for pediatric services design.

Method

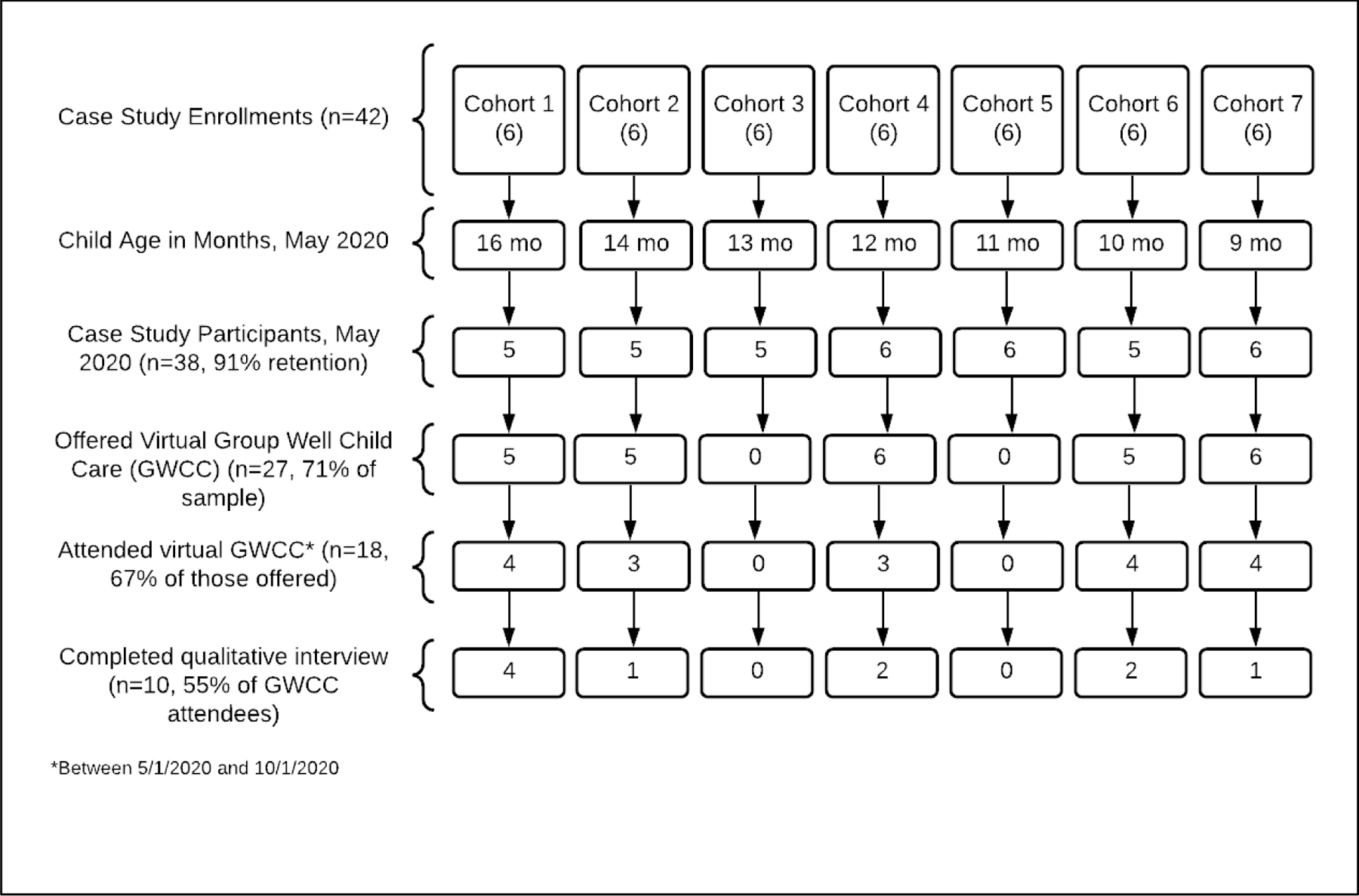

The study was conducted in an urban, academic general pediatric clinic serving a majority Latino patient population with Spanish-speaking immigrant parents. In 2019, the clinic began offering CenteringParenting® (CP) in Spanish for families of patients ages 0–2. CP is a GWCC model developed by the Centering Healthcare Institute that includes developmental and postpartum screening, individual health assessments, and a multifamily group discussion (Centering Healthcare Institute, 2017). As part of an ongoing case study of GWCC implementation at the clinic (Platt et al., 2021), this study examined the first seven GWCC cohorts (enrolled by child birth month; Figure 1). The clinic implemented virtual GWCC from May-September 2020. Mothers attending in-person GWCC were invited to 45–60 minute virtual group sessions on Zoom with their cohorts, co-facilitated by a pediatrician, social worker, and GWCC coordinator. Typically, the coordinator scheduled individual in-person visits for vaccinations and physical exams following the session. This study examined implementation of the virtual GWCC adaptation during COVID-19 through interviews with providers and mothers, medical record review, and a survey assessing COVID-19 impact administered to mothers. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine IRB.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of Mother Recruitment and Virtual Group Well Child Care participation

Data collection

We employed a triangulation mixed methods design, collecting distinct and complementary qualitative and quantitative data within a similar timeframe (Creswell, 2015). Quantitative data included the 12-item COVID-19 Impact Scale, which assesses impact on daily life, financial stability, physical and mental health, family conflict, and COVID-19 diagnoses of self, family, and friends (Stoddard, 2020). The survey was administered by telephone from June-October 2020. Demographic information, including maternal age, years in the US, number of children, and self-reported English language proficiency was previously collected as part of the parent study. Medical record review captured this study’s primary “service outcome,” virtual GWCC session attendance.

Qualitative data included semi-structured interviews with pediatric providers/staff (n=8) including five pediatricians, two social workers, and one GWCC coordinator. A bilingual research coordinator (JA) interviewed mothers who attended virtual sessions; we contacted all mothers attending virtual GWCC sessions. RP interviewed all providers conducting in-person and virtual sessions. Interview guides were informed by Proctor’s taxonomy of implementation outcomes, including acceptability, feasibility, and service outcomes, such as patient-centeredness1 (Appendices A and B).

Data analysis

Qualitative analyses began with interview transcript review, creation of a preliminary codebook with a priori codes based on Proctor’s taxonomy, and identification of emerging codes and concepts unique to study stakeholders. Matrices were developed in Microsoft Excel to summarize themes, sub-themes, connections between themes, and patterns within and across informants. The process was similar to Framework Analysis (Gale et al., 2013), but coding and charting were completed simultaneously. The matrix was refined through an iterative, collaborative process; the team met weekly until consensus was reached. At least two coders identified themes for each interview (AB, RP, NW-L). A researcher from another institution (RBJ), who is studying CenteringParenting® at several sites nationally, also informed interpretation.

Descriptive statistics were calculated to identify factors associated with virtual session attendance. Potential correlates included sociodemographic factors and COVID-19 Impact Scale items. Bivariate analyses of correlates by session attendance included t-tests and Chi-square statistics. Analyses were conducted in Stata/SE 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Of the 38 mothers enrolled in the ongoing case study in May 2020, 71% (n=27) were offered virtual GWCC sessions between May and September (Figure 1). Of those, 67% (n=18) attended GWCC virtually. Ten mothers participated in semi-structured interviews related to that experience. Women who were interviewed did not differ from those who were not in educational attainment, years in the US, number of children at home, or English proficiency. Children were 8–15 months at the time of the virtual sessions. Ninety percent of mothers enrolled in the case study received at least one in-person service (urgent or routine) during that period.

On average, mothers were on average 29 years old and had two children; the majority reported less than a high school education (Table 1). Immigrant mothers had lived in the U.S. on average five years (range: 0–20). Two-thirds reported limited English proficiency. Most (80%) indicated the pandemic had moderately or extremely impacted at least one major area of their lives.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and COVID-19 impact among Spanish-speaking Latina mothers enrolled in the Group Well Child Care ongoing case study

| Average | |

|---|---|

| M (sd), range or % (n) | |

| Selected demographic characteristics1 (n=38) | |

| Maternal age in years | 28.7 (6.1), 19–40 |

| Maternal education | |

| Less than high school | 52.6 (20) |

| Some high school | 26.3 (10) |

| High school graduate and beyond | 21.1 (8) |

| Cohabitates with romantic partner | 76.3 |

| Number of minor children in household | 2.1(1.0), 1–4 |

| Years lived in the U.S.2 | 5.0 (5.2), 0–20 |

| English language proficiency (How well do you speak English?)3 | |

| Not well (poor) | 68.4 (26) |

| Ok | 21.1 (8) |

| Well | 7.9 (3) |

| Very well | 2.6 (1) |

| COVID-19 impact,4 (n=33)5 | |

| Extent to which the coronavirus pandemic has impacted/interfered with your… | |

| 1. Daily life | 1.9 (0.9), 0–3 |

| 2. Income/employment | 1.7 (0.9), 0–3 |

| 3. Food security | 1.3 (0.9). 0–3 |

| 4. Medical care | 1.2 (0.5), 0–2 |

| 5. Mental health treatment | 0.5 (0.8), 0–3 |

| 6. Social support from non-family members | 1.2 (0.8), 0–3 |

| 7. Emotional distress | 0.8 (0.9), 0–3 |

| 8. Family conflict | 0.4 (0.6), 0–2 |

| Areas of life impacted “moderately” or “extremely” | 2.3 (1.7), 0–5 |

| Other impacts of the pandemic | |

| 9. Personal COVID-19 Diagnosis | 24.4 (8) |

| 10. Number family members diagnosed with COVID-19 | 0.6 (1.2), 0–4 |

| 11. Severity of “sickest” family member6 | 0.5 (0.8) (0–2) |

| 12. Number of extended family/friends diagnosed with COVID-19 | 2.8 (5.1), 0–20 |

| 13. Severity of “sickest” extended family/friend?6 | 1.2 (1.3), 0–4 |

| Total COVID-19 Impact Score7 (11-item sum) | 9.2 (5.3), 0–20 |

Notes.

Demographic information collected at study baseline from February to September 2019

Denominator excludes one U.S.-born mother

English proficiency scale as follows: 0=Not well (poor); 1=Ok, 2= well, and 3=very well

For the first eight items, Likert responses included: 0=no change, 1=A little change, 2=moderate change, and 3=extreme change

Denominator changed as 33 of 38 completed COVID-19 Impact Scale measure

For COVID-19 severity scale: 0=none, 1=some symptoms, controllable at home, 2=severe symptoms requiring brief hospitalization, 3=very serious, requiring a ventilator, 4=person died

Sum of scores for items 1–9, 10 and 12

Bivariate analyses did not identify statistically significant differences in virtual GWCC attendance by maternal age, education, or number of children (Table 2). Mothers who attended virtual groups reported marginally lower English proficiency (p=0.087) compared to those who did not. Mothers who did not attend reported higher COVID-19 impact on mental health care (p=0.011) and more friends and family members with COVID-19 compared to mothers who attended (mean=5.1 vs. 1.0; p=0.035). Combined COVID-19 Impact scores did not vary by virtual session attendance.

Table 2.

Demographics and COVID-19 impact items associated with virtual Group Well Child Care group attendance among Spanish-speaking Latina mothers, from May to September, 2020, N=27

| Attended Virtual GWCC Group | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | Total | P-value | |

| Total, % (n) | 33.3 (9) | 66.7 (18) | 27 | -- |

| Demographic characteristics 1 | ||||

|

M(sd) or % (n) |

M(sd) or % (n) |

M(sd) or % (n) |

||

| Maternal age in years | 27.3 (6.0) | 29.2 (6.3) | 28.6 (1.2) | 0.762 |

| Maternal education | ||||

| Less than high school | 55.6 (5) | 50.0 (9) | 51.9 (14) | 0.948 |

| Some high school | 22.2 (2) | 22.2 (4) | 22.2 (6) | |

| High school graduate and beyond | 22.2 (2) | 27.8 (5) | 25.9 (7) | |

| Cohabitates with romantic partner | 88.9 (8) | 77.8 (14) | 81.5 (22) | 0.484 |

| Number of minor children in household | 2.3 (1.2) | 2.2 (1.0) | 2.2 (1.1) | 0.353 |

| Years lived in the U.S.2 | 5.0 (6.4) | 5.0 (5.5) | 5.0 (5.6) | 0.500 |

| English language proficiency3 | 0.7 (1) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.087* |

| COVID-19 Impact Items 4 | ||||

| 1. Daily life | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.9 (0.2) | 1.8 (0.8) | 0.803 |

| 2. Income/employment | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.6 (0.9) | 0.397 |

| 3. Food security | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.3 (1.0) | 1.3 (0.9) | 0.350 |

| 4. Medical care | 1.1 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.533 |

| 5. Mental health treatment | 1.1 (1.2) | 0.3 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.011** |

| 6. Social support from non-family members | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.9) | 0.382 |

| 7. Emotional distress | 1.0 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.8) | 0.213 |

| 8. Family stress/discord | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.7) | 0.270 |

| Areas of life impacted “moderately” or “extremely” | 2.4 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.3 (1.7) | 0.406 |

| 9. Personal COVID-19 diagnosis | 0 | 27.8 (5) | 20.0 (5) | 0.119 |

| 10. Number family members diagnosed with COVID-19 | 0.7 (1.5) | 0.6 (1.2) | 0.6 (1.3) | 0.431 |

| 11. Severity of “sickest” family member5 | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.4 (0.8) | 0.5 (0.8) | 0.427 |

| 12. Number of extended family/friends diagnosed with COVID-19 | 5.1 (8.6) | 1.1 (2.4) | 2.2 (5.1) | 0.035** |

| 13. Severity of “sickest” extended family/friend?5 | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.6 (0.8) | 0.9 (1.1) | 0.101 |

| Total COVID-19 Impact Score6 (11-item sum) | 8.9 (5.6) | 9.6 (4.1) | 9.3 (4.5) | 0.636 |

Notes.

statistically significant at p< 0.05

marginally significant at p<0.10

Demographic information collected at study baseline from February to September 2019

Denominator excludes one US-born mother

English proficiency scale as follows: 0=Not well (poor); 1=Ok, 2= well, and 3=very well

For the first eight items, COVID-19 impact responses included: 0=no change, 1=A little change, 2=moderate change, and 3=extreme change

Responses included: 0=none, 1=some symptoms, controllable at home, 2=severe symptoms requiring brief hospitalization, 3=very serious, requiring a ventilator, 4=person died

Sum of scores for items 1–9, 10 and 12

Mother and Provider Perspectives

Five implementation and service outcome themes were identified, most in-line with Proctor’s taxonomy, some containing sub-themes: 1) acceptability, 2) patient-centeredness (social support; group dynamics), 3) feasibility (technology; scheduling; resources; billing), and 4) safety/privacy (home setting), and 5) recommendations. Tables 3–4 describe themes and display selected quotes.

Table 3.

Summary of mother and provider perspectives on virtual implementation* of Group Well Child Care groups

| Theme | Mothers | Pediatrics Providers |

|---|---|---|

| Implementation Outcomes: | ||

| 1) Acceptability | Mothers reported finding format acceptable overall; viewed as “next best alternative” to in-person implementation in COVID-19 context | Providers found format generally acceptable, with challenges related to billing, scheduling, and staff resources |

| 2) Feasibility | ||

| 2a) Technology | Mothers noted some connectivity issues, which improved after troubleshooting | Providers noted barriers related to internet connectivity, background noise and data costs for the mothers |

| 2b) Scheduling | This theme did not emerge among mothers | Providers reported scheduling challenges, especially with work conflicts (of mothers) during day; concerned about burden on mothers to attend both in-person and virtual sessions |

| 2c) Resources | This theme did not emerge among mothers | Necessary to have dedicated coordinator on staff |

| 2d) Billing | This theme did not emerge among mothers | Confusion arose with coding; new COVID-19 era modifiers for virtual services welcomed |

| Service Outcomes: | ||

| 3) Patient-Centeredness | Most described being satisfied with the chance to ask questions and receive informative answers to questions about child health and development | Comparable to in-person sessions, with more education focus and with new topics like COVID-19 and home safety |

| 3a) Social support | Some valued social connections, especially during COVID-19, others missed the “informal socializing” of in-person groups | Providers noted that mothers seemed to especially value social connection in the virtual GWCC within the COVID-19 context |

| 3b) Group dynamics | Mixed – some described virtual groups as more awkward and others said they were better (provided the opportunity to pay attention) | Providers described some mothers as more distracted, others as more engaged; some said 4+ groups ideal; some credited prior in-person groups as helping dynamic, others said it was just about “personalities” mix |

| 4) Safety/privacy | Some said not dissimilar to in-person (uncomfortable with sensitive topics in either); others said less likely to discuss partner relationship at home; some noted concerns about if the session was being recorded and who else was “in the room” | Used more caution with sensitive topics |

| 4a) Home setting | Convenient (without need to arrange transportation or childcare) but also distracting | More distractions and also more opportunities to discuss home safety (e.g., cabinets) |

| Client Outcomes: | ||

| Recommendations to improve client satisfaction in the future | Consisted mostly of specific child health and development topics and the ability to be provided with a list of possible topics in advance | Suggested use of active learning online features (breakout rooms, polls, videos); stated need for more guidance to protect confidentiality (e.g., headphones); new models suggested: a) hybrid in-person during vaccine visits and virtual during medical visits that are ok to be virtual; b) opening up cohort structure to “drop in” style |

Guided by a framework for assessing the implementation of intervention strategies and outcomes developed by Proctor and colleagues (Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7)

Table 4.

Selected Mother and Pediatric Provider Quotes by Theme and Sub-Theme

| Mothers | Pediatric Providers and Staff | |

| Theme 1: Acceptability | ||

| Of course, if we can’t meet in a group right, in a normal group, yes, of course I would like to join by, by video call. …Yes, [in person is my preference] for the kids, so that the little ones can interact a little. -Mother, Age 38 Yes. This [virtual session] is a good alternative. It seems fine to me like this because one isn’t going out so much and exposing their kids, to well, it’s not a good option right now in this moment in the hospital because you never know, right. –Mother, Age 27 |

I think people want to connect, I think ultimately people want to stay connected in some way or another, during this difficult time. And with it’s with other women who have kids the same age, I think that’s something they can really, that really you know, they can understand each other in some ways. – Pediatrician | |

| Theme 2: Patient-Centeredness 1 | ||

| I liked it because you hear more different, because they explain a lot of things to us. We’re all paying attention. I think it’s better on the call because everyone is paying attention to what they’re saying… [The interactions that I had that day with the doctor and the social worker were] excellent, very good… They know how to explain well and they listen, you see that they take the time with you. –Mother, Age 33 The expression lacked a little more, more, like more explanation, so like, because the, because I feel that because of the time it was fine that… we didn’t cover many topics… They answered the questions that we had and even the important thing is that sometimes one wants to ask more or know a little more about the topic but because, because of the time as well [we couldn’t]. –Mother, Age 27 Because we can, like asking about the children, like about, about what help we can receive with regard to, to the problem of, of what’s happening now with the coronavirus. We also because, we have a, an application about how we can get an emergency visit when a patient from, when a person from our household is sick, or something like that. –Mother, Age 26 |

Some of the stuff like feeding and sleeping, it just seems to be more like lecturing again. Like how are they sleeping? Are they sleeping through the night? Anybody else? How, how are people putting, soothing their children? You know, I don’t know… but maybe some of the subjects where there was sort of a natural group pause in person, that kind of was able to hold the room a little bit better than in the virtual format for some of these questions around like, what do you like to, you know, what does your baby like to eat. …It is hard to ask [laughs] questions, when everybody’s sort of in a different level of concentration and focus. -Pediatrician I think that in general they were just listening. Which is, I mean I guess it was necessary sometimes, but like if that way is easier for them to engage more, not just be, ‘cause they were listening so they were, okay, I’m just listening so I can be doing something else. And they were like [laughs] doing something else instead of actually … paying more attention. –Coordinator |

|

| Theme 2a: Patient Centeredness-Social Support | ||

| For me it’s very good. Because it’s a time where we, can express ourselves, we can ask questions, we can see each other. …We can see each other’s faces there and it’s something different than being stuck at home every day. –Mother, Age 33 I felt very happy so, from seeing them in that appointment, seeing that they were doing well, really, and from knowing that they’re happy, and that they’re at home. But, it’s better, it’s the better thing to do, to stay at home, and not be running around somewhere outside. You never know what people you’re dealing with. And, well, I feel happy from having seen them, all of them, I feel really happy. And even though I didn’t see them personally, but if I can know that they’re okay and that makes me really happy, that makes me really happy. –Mother, Age 26 Seeing the other people… I felt as if we were really all hanging out in the same place… I spoke with my three friends, saw their three babies… I felt happy because I, later, whenever I meet up with other people it’s always, with all the conversing and talking and there are… It’s been a long time since we’ve been able to leave the house with both, well with my kids, and the cough. –Mother, Age 33 |

I think that, you know, if they took the time to get on, you know, make the space to get on, they were happy to be there But I think people want to connect, I think ultimately people want to stay connected in some way or another, during this difficult time. And…with other women who have kids the same age, I think that’s something they can really, that really you know, they can understand each other in some ways. -Pediatrician | |

| Theme 2b: Patient-Centeredness-Group Dynamics | ||

| But sometimes it’s also because of the time, I feel that the mamas like don’t, well, I felt that some of the mamas express themselves more being in the clinic than like this on the phone…Because on the phone I’m saying you can miss the way, the, the word, raising their hand to say to me, and everyone being there, well they say ‘here I am, look’, that causes doubt sometimes. Well, I felt that. –Mother, Age 27 I felt natural, pretty natural [in the virtual session]. [The interactions] were similar. –Mother, Age 38 Well, we talked. A little more…. With more confidence [than in person]. Well, I feel that… because there’s a little shyness I think, because I think I’m a little shy, I haven’t really liked talking [but I wasn’t so shy on the video call]. –Mother, Age 20 It was very good. We were conversing about several topics there. The truth is… there were only two of us mamas there. I don’t know if it was better like that since we had more opportunities to, speak about everything like the worries that the other mama had and the ones I had. So that was very good. –Mother, Age 22 It would be good if more people came to the meetings because if there are more then there’s more talking. –Mother, Age 38 |

I think when we went to virtual, I think I had four groups in total, you know, that varied in the age of the kids at the time that they ended. So maybe something like two months, six months, nine months, and twelve months. We tried hosting all of them. As far as I remember. Some of them worked very well. The groups that were already established were the most successful in terms of attention, attendance and maternal engagement. And I think my greatest success was with the pretty well- established groups. -Pediatrician I mean, I think many mothers are avid for information and they’re willing to take it from a variety of, of different people, as long as they’re trusted people. But, you know, that there is something pretty special about that peer teaching when you see it happen. And if you don’t have enough people that’s not gonna happen. -Pediatrician |

|

| Theme 3a: Feasibility-Technology | ||

| Well, I had never used it but I had heard of that platform and well, I felt it was a good, if one, I imagine that if one has internet, there’s not going to be any distortion, no, or, I mean it’s not going to cut out. But for some mamas, well I mean, they can’t read, or they can’t, they’re not very familiar with technology so, like, because one mama didn’t, she didn’t connect, so she couldn’t hear, or I don’t know, the connection cut off. –Mother, Age 28 | I think it was at least one mother of every group [laughs]. At least. Yeah, or like, it seems like it was in every meeting someone couldn’t join or couldn’t download the app on their phone or some of them that there was mother, one mother, like she can’t read, so she wasn’t sure of how to, she had to wait until somebody else come and help her. And so things like that. -Coordinator Yeah, we would have some intermittent challenges. I guess because of the online school, our families did pretty well with Zoom. So that set up worked out pretty well. Whenever we did have technological challenges, I think it was from their end, so we, I just sort of passed. I was like, ‘okay, señora, we’re gonna go to the next lady, we’ll come back.’ –Pediatrician |

|

| Theme 3b: Feasibility-Scheduling | ||

| That time when I was talking in that moment, that, that they were going to call, I had to go to work and receive the call at my work. I didn’t do it at home But I, the people I work for, they gave me permission to be able to accept the call, I could ask the questions that I had to ask. That could, she didn’t, didn’t get angry about that, instead they told me that it’s fine, I can receive the call. -Mother, Age 25 | My experience was that the biggest challenge was …it was interesting. It was like people weren’t available. So, many of them were still working. A couple of them specifically were, are like in the somewhere in the chain of custody for like Amazon distribution. I don’t know if they work at official Amazon facilities. But they work at, you know, a packing, or merchandise, you know, warehouse of some kind. So they were working, which was always kind of an impediment. But they always made it to the groups otherwise. …I almost wonder if the group being like at that certain same time slot every two months, or every six months, was fine for them, but then when we started moving things around. Or when, you know, then it was like well, my work schedule’s already set. There’s not some alternative time that is better. –Pediatrician And I thought it was really great that the mom who was working came. She was listening, she had some questions. She was involved. You know, and if she you know, if we had done that visit in person, maybe she couldn’t have come But I, you know, since it’s a lot of talking, I think that she really was, I think there’s a benefit to that, of being able to have some flexibility. She was very comfortable, you know, like I said she, she felt like she was in a place where she had enough privacy. But she was really, she was engaged and seemed to appreciate it. -Pediatrician |

|

| Theme 3c: Feasibility-Resources | ||

| Sub-theme did not emerge from Mother interviews | I guess the only comment is you know, when you think about staffing, the problem with virtual is just that you really need that third person, the tech person and that’s, it’s a lot. I mean it’s not prohibitive, but I can imagine places being, wary of that added expense. …And it’s important to get it right because it’s very easy to offend people. You know, you don’t unmute somebody, you mute somebody, so it, that does have to be done correctly. –Pediatrician | |

| Theme 3d: Feasibility-Billing | ||

| Sub-theme did not emerge from Mother interviews | I think that it [billing] was confusing and I think we relied on those with more experience or who had …done some more troubleshooting to figure out what we were supposed to bill for that particular type of encounter. And what …documentation in the medical record that would look like. -Pediatrician It’s hugely important that of course we went virtual for the same reason that everybody went virtual, and so there’s been huge progress on telemedicine. So, you can bill for telemedicine visits. There’s a telemedicine modifier if the, if a mother can only participate by phone. So that’s really helpful. And I am, I’m pretty sure there is a modifier if there’s no kid. So, you know, you have a telemedicine appointment, and dad shows up to pick up the kid early, I think there’s a modifier so you can have it with the parent. So there are a lot of different ways to bill. You’re not going to get a ton of money for any of those ways, but it, it, it really helps. –Pediatrician |

|

| Theme 4: Safety/Privacy | ||

| Eh, no, I mean, no, I don’t have any in mind that, I mean, or that would be very difficult to talk about. I mean but if it was a difficult topic, well I wouldn’t do it on, on a video call. …I wouldn’t want all the people there, listening to the video call, to hear it. –Mother, Age 38 Mm, well about matters that are sometimes, well I don’t, I don’t have any problem in that way. The thing is I know it’s confidential, and, and that well, well I feel that like this because, because I like hoping to share my experience with other mamas that say, or I didn’t like going through that, no, or the other. –Mother, Age 27 |

I certainly recall between myself and like the social worker and [coordinator], debriefing afterwards, I think we always felt a limitation about trying to broach more sensitive family inter-dynamic questions and discussions. Just because of not knowing sort of who was in the room, or within hearing distance of the call or, if children, if other children were around, which we sometimes had that in person as well. So, I think we just felt more sensitive about kinda consciously not bringing up some of those more difficult topics. -Pediatrician | |

| Theme 4a: Safety/Privacy-Home Setting | ||

| For me one of the things is the community that one had. And it helps that it’s in the house and all that. In my case, my baby was sleeping at that time, and I would have had to go out to get there, bring him with me and all that. I like it. …But when there are these appointments for vaccines or something like that, then there’s no other way they can. …And also for the children, especially now that it’s so cold, you don’t have to drag them out there. -Mother, Age 37 | It was challenging because the kids are all over the place. So I think the mother was having a really hard time, like chasing the kid around the house and participating adequately and figuring out like turning herself on and off of mute [laughs]. -Pediatrician The capacity to see people’s houses is, you know, assuming that they’re home when they’re doing the visits, which was my, that was my experience, you, I mean you could talk about like safety things and you could have women, mothers like sharing, like if anyone had a baby gate, like showing everybody else. Or had like cabinet locks. Or, you know, those type of things could be, like they could share the things that they’ve done for safety. That would be, I guess, one advantage of doing the virtual with people at home. You could, you know, you could have mothers show the, like the books that they had for their kids, or the toys that they had for their kids, or you know, their, I guess talking about other things that mothers were finding or that their kids were enjoying. That would be easier when they’re already in their home setting. –Pediatrician |

|

| Theme 5: Future Recommendations | ||

| We could have something like the, well, we vote to indicate which topics we want, what they’re going to cover, ahead of time. Because sometimes when you’re there on the video call, everything disappears from your head. So, or in a way where the, the doctor or they would have the topics and we would tell them yes, we want to cover that topic, that topic and that topic. And it’s like they upload a list and we cover the most, the most important ones. And so that, because sometimes well, there are things that one, one doesn’t know about, so it can be interesting to one as, as a parent. So that seems good to me, no, a good option… for them to, to upload a list of topics. And then we can tell them yes, as mamas, yes I respond to that topic, let’s cover that topic, like that. Yes, because then this way with the dynamic of the group, so they have that diversity of topics that say well, you can choose a topic. Because when I was in the group like this about, about when I was pregnant, the doctor did it like that. A list of topics and then we choose what topic we wanted her to, to cover. So now I remembered it and it’s a good option for, for when we forget something and everything goes out of our heads. –Mother, Age 27 Talking more about the mamas [would be good], that, that about talking about, about sometimes when one is at home sometimes you get depressed, well, I’m not talking about me because I’m so busy and talking to everyone, and, but I’m talking about mamas that don’t, haven’t learned how to be at home. Because sometimes their life is outside, not at home. …But it’s like they work, they, they want to go out everywhere, and can’t. That, how depression, sometimes being with the little kids can leave you with [laughs]. –Mother, Age 26 |

I would probably try to involve their space a little bit, depending on how comfortable they are…. with a virtual visit you’re going, stepping a little bit into their house, and their space and so I would try to sort of maybe say like ‘can you, can you show us your kid’s favorite toy? Or what’s your, what’s a favorite thing?’ And they could, you know, if they feel comfortable, like, you know, show a little bit of what’s going on in their home, something they’re proud of, something they’re happy with, a favorite toy, whatever. You know, to kind of [have] a little more of sharing the personal side of raising their child. I think if they were engaged and we could do the video I think there are some good video opportunities to explore, around certain developmental milestones …take advantage of the internet in some ways to do some demonstration and sharing in a different, in a more personal way if that’s what people feel comfortable with. -Pediatrician I guess maybe for, trying to think, you know, would there be a benefit to, I guess for like, like the nine-month visit for example, there’s often not any shots being given at the nine-month visit. You already know if babies are on a pretty good like growth trajectory at that stage. So you could do the nine-month visit entirely virtually. Without really sacrificing medical needs. But that would be, like the nine-month visit and the eighteen- month visit could be both probably done fully virtually. You know, and by that point maybe the, you know, if the babies have had an in person one-month, two-month, four-month, six-month visits, the group is well formed, the group knows each other well, and then you could try doing like a nine-month virtual and seeing how that goes. -Pediatrician I think that it would be more valuable for the, for the patients like if we had more kind of activities that like, you know, like when you’re doing a class, right. More like a, probably include like breakout rooms where small teams get together and they come back. So they are active learning and not just listening….. So maybe include more activities that require for them to be more engaged and, that they need to participate more like, with questions, with uh, some things to do, like they can actually do. Even if they’re not doing it on the computer or the phone but like, write something and do it and then show it. Like things that engage them more. -Coordinator |

|

When we refer to patient-centeredness in this paper it is in the context of a parent model of child well-visits and thus we consider the parent-child dyad to be the patient.

Acceptability

All mothers described virtual sessions as acceptable or a “good alternative” to in-person groups. Two mothers described virtual groups as comparable to in-person groups. Most indicated a desire to continue virtual sessions during COVID-19 but preferred in-person groups. Providers had mixed perspectives on acceptability, and most reported that sessions with 4+ participants were most productive. The GWCC coordinator reported most mothers wanted to participate, but some were unable to attend due to work conflicts.

Patient-Centeredness

Mothers had predominantly positive feedback about session content and process. While some described the provider as driving more of the discussion in virtual versus in-person GWCC, mothers felt their questions were well-addressed. Perceived benefits included connecting to other services and receiving COVID-19-specific information.

Most providers reported that online sessions focused more on education than sharing and often felt like they were lecturing parents. One provider described how “decoupling” the individual checkup and group sessions was difficult because she was not able to familiarize herself with families in the individual visit before beginning the group, as would typically occur in-person. Conversely, several providers reported being able to conduct more focused individual visits because of information shared in the group. Another provider felt virtual visits increased her accessibility to patients during a difficult time.

Social support.

Most mothers and providers identified social support as a benefit of attending virtual sessions. Mothers reported that they particularly valued these connections during the pandemic; providers agreed, perceiving mothers were experiencing social isolation and increased stressors. One mother expressed relief at seeing other mothers and babies, stating “even though I didn’t see them personally, but if I can know that they’re okay…that makes me really happy.” Two reported having close connections with other group members, and one said the group helped her feel less alone. Conversely, several mothers described social drawbacks of virtual sessions, including less opportunity for babies to interact and mothers to socialize.

Group dynamics.

Half of the participants described at least one aspect of virtual group dynamics as awkward (e.g., due to the more formal feel of Zoom “we don’t even realize that we can greet each other and say hello”). One provider reported that mothers seemed more distracted in virtual sessions. These distractions included tending to children, cooking and for some, work. Several mothers and providers described decreased interaction among mothers, attributed in part to mothers not knowing when the next person would speak and/or feeling self-conscious on video.

Conversely, several mothers described the virtual group dynamic as better than in-person. One mother reported feeling more confident speaking in virtual sessions; another noted everyone had the chance to speak. Similarly, one provider felt virtual visits allowed her to better command “the room,” facilitating a structured approach to elicit participation.

While some mothers wanted larger virtual groups, one woman in a two-person group felt the small size fostered closer connection between mothers. Providers generally felt groups had to reach a certain size (e.g., 4+) for optimal peer learning. Several providers reported GWCC cohorts that had previously met for in-person visits were more successful than those that had not.

Feasibility

Technology.

Mother and provider perspectives were generally consistent, describing technological capability as initially low. Some mothers were unfamiliar with Zoom and needed assistance, either from the coordinator, who sent instructions in advance, or from children in the household. All mothers used cell phones and some had challenges viewing other participants. Despite some continuing difficulties (e.g., poor connectivity), most described increasing comfort with technology over time.

Scheduling.

Scheduling was challenging, particularly when mothers returned to work after stay-at-home orders were lifted. Providers noted it was challenging to schedule virtual visits in the morning when in-person visits would have occurred due to demands of assisting children with school and sharing electronic devices among family members. Thus, some virtual groups were scheduled later in the day, although this posed challenges if providers fell behind schedule as the day progressed. One provider preferred having more control over her schedule and more time to prepare mentally by conducting virtual sessions on days when she did not see other patients.

Importantly, families still needed to attend in-person well-child visits to receive immunizations. It was especially difficult to schedule virtual groups at these times as additional time off work was required for separate group and individual visits. Providers felt mothers were less motivated to attend virtual sessions if they had already attended an in-person visit.

Resources.

Providers and mothers felt it was vital to have the coordinator at sessions for technical support to mothers and visit scheduling. When virtual session attendance was low, there was concern whether resources devoted to these sessions were justified.

Billing.

Providers reported confusion about appropriate billing codes and practices for virtual GWCC. Billing challenges for virtual group visits arose when mothers attended without their child or if an in-person visit occurred the same day. However, as one provider noted, reimbursements permitted for telemedicine during COVID-19 made virtual GWCC possible.

Safety/Privacy

Some mothers avoided speaking about sensitive topics in the virtual setting due to the presence of others in their homes. One mother indicated that, in contrast to in-person groups, it was hard to know who was present “in the room” during a virtual group as it was unclear who was in other members’ homes. Another mother wondered whether video visits were being recorded.

Providers also had concerns regarding safety and privacy, noting it was often difficult to know how private home or work settings were; “Just because of not knowing sort of who was in the room, or within hearing distance of the call or … if other children were around, which we sometimes had that in person as well.” Thus, most providers opted not to address sensitive topics such as sexual health, intimate partner violence, and managing unwanted advice from family members.

Home setting.

Most mothers attended virtual sessions from home. For many, attending visits from home was helpful, enabling them to avoid public transportation and reducing time burden, cost, and infection risk. Conversely, some mothers expressed concern about background noise and wondered whether it interfered with others’ ability to hear discussions. Several providers mentioned that competing demands in the home setting (e.g., childcare or cooking) made sessions challenging. However, providers also discussed how the home setting could be used constructively (e.g., discussing home safety measures). Providers mentioned that several mothers attended virtual visits while at work and noted that they, nevertheless, seemed engaged and dedicated to the sessions.

Recommendations

When asked how they would improve virtual GWCC, most mothers focused on content areas they wanted learn more about (e.g., child development, remote learning support, maternal mental health). One mother suggested attendees be provided with a list of potential topics in advance from which they could choose. Several mothers mentioned higher group attendance would be helpful.

Several providers recommended better leveraging functionalities of the virtual platform (e.g., polls, breakout rooms, incorporating videos and visual aids) to facilitate active learning and peer interaction. Providers felt an hour was too long for virtual sessions and recommended 45 minutes to avoid “Zoom fatigue.”

Provider recommendations to increase privacy included an initial contract to ensure that mothers understand the need for a confidential space. However, providers were mindful of constraints mothers may experience and suggested, at a minimum, asking mothers to use headphones to increase privacy. Providers also recognized the unique opportunity to involve the home setting in virtual sessions and suggested developing guidelines or standards for how this could be done.

Providers had several suggestions to improve feasibility of virtual GWCC participation by minimizing the potential burden on families being asked to attend in-person “exam” visits as well as virtual GWCC. One suggested a hybrid approach where standard in-person visits occur at times when in-person well-child visits were required, and virtual sessions occur when individual visits could also be completed virtually (e.g., when no vaccinations were required). Other providers suggested in lieu of closed cohorts of mothers with same-age infants, group discussions be available to all families in the practice with similar-age children. While this would represent a departure from the CenteringParenting® model, it was viewed as potentially more feasible from a resources perspective and more likely to facilitate optimal group sizes for peer learning.

Discussion

With heightened urgency in the COVID-19 era, studies are examining the extent to which telemedicine will hinder or promote health equity (Badawy & Radovic, 2020). This study described experiences of Spanish-speaking immigrant Latina mothers and providers as GWCC transitioned to a virtual format. Despite pandemic-related disruptions and concerns about families’ ability to engage in telemedicine (Katzow et al., 2020), 67% of mothers scheduled to attend a virtual session did so. Mothers with lower English proficiency had higher virtual group attendance, a departure from literature that has shown that Spanish-speaking patients were less likely to attend virtual appointments (Blundell et al., 2020) and in-line with previous studies of in-person group interventions (Dillman Carpentier et al., 2007). While many described drawbacks to the nature of virtual group interactions as compared to in-person, mothers also identified social support as a benefit that was more highly valued during the pandemic, potentially due to increased psychological stress (Serafini et al., 2021). These findings suggest that Spanish-language virtual groups may provide access to social supports and resources that are scarcer for Latina immigrant mothers with limited English proficiency during the pandemic. Conversely, mothers reporting more pandemic impact attended proportionately less, suggesting competing demands may have outweighed motivations to attend (Hibel et al., 2021).

Mothers and providers found virtual GWCC an acceptable and “good alternative” during COVID-19. While some experienced technology challenges, these were not insurmountable. In general, mothers and providers described sessions as patient-centered and noted that virtual groups facilitated answering questions more thoroughly than would have been possible during individual in-person well-child visits during COVID-19. While both groups noted privacy concerns specific to virtual sessions, the home setting also provided an opportunity to address home safety topics. Providers had concerns about billing, adequate attendance, resource utilization, and scheduling, which may limit the sustainability of virtual GWCC. The GWCC coordinator played a vital role, both in in-person and virtual groups, although tasks varied across the two modalities.

Strengths and Limitations

Study strengths included use of quantitative and qualitative data and data collection from both mothers and providers, including half the mothers and all providers involved in virtual groups. Analyses were in part guided by an established implementation science taxonomy as well as stakeholder input related to recommendations for virtual GWCC redesign. We explored perspectives of Spanish-speaking immigrant women, often underrepresented in research and disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 (Macias Gil et al., 2020). Finally, research team members observed in-person (RP & JA) and virtual (RP) visits.

This study has several limitations. It was based at one clinic, which conducted all virtual groups in Spanish; findings may not generalize to other settings. To address this limitation, we included a member of the research team (RBJ) who could contextualize our findings based on experiences with virtual GWCC at other clinical sites. The study site conducted virtual groups during a limited time period relatively early in the pandemic. We only interviewed mothers who were part of the ongoing case study (families who participated in in-person GWCC between March and September 2019). Participating providers, however, were able to reflect on their experiences with women participating in GWCC across the clinic. We only interviewed mothers who attended virtual GWCC, limiting our understanding of perspectives of mothers who did not participate.

Implications beyond COVID-19

This study provides insights regarding virtual group services with immigrant Latina mothers. While some mothers did not participate in virtual groups, other mothers whose work schedules would have otherwise prevented in-person attendance participated from work, suggesting potential to address logistical and financial barriers for a subset of families. Further research is needed to better understand the trade-offs involved between offering mothers that flexibility and introducing privacy concerns. Many child- and family-serving practices and programs are reflecting on ways in which such options for patients (and caregivers) may be advantageous, beyond the COVID-19 era, to afford families flexibility in meeting their competing needs. That said, this study took place early during the pandemic, when many families were managing virtual learning from home. The degree to which our findings translate beyond this context merits future research.

For providers and staff, facilitating in-person and virtual GWCC prompted creative thinking about future well-visit redesign. Most providers noted that having at least four participants was optimal for virtual groups to be feasible from a resource and peer learning perspective. As such, some providers suggested holding monthly virtual group office hours in place of the standard “cohort structure” of GWCC. Other sites delivering GWCC during COVID-19 also transitioned to social “check-ins” instead of formal virtual groups. When in-person GWCC resumes, these “check-ins” could occur parallel to or independent of GWCC, providing an additional type of family-centered service, particularly if telemedicine reimbursement continues. These types of services are not traditionally provided in primary care settings; further evidence of their benefit would likely be needed to encourage more widespread adoption by clinics or payors. Alternatively, hybrid models could offer a combination of in-person and virtual groups for mothers who anticipate difficulty attending in-person GWCC.

Billing, staffing, privacy, and other logistics must be clearly articulated for virtual groups; established protocols and guidelines would facilitate this process. Additionally, best practices to promote confidentiality in virtual settings are necessary. Providers agreed that physical exams should take place after virtual groups to maximize engagement. A study team member (RBJ) who assessed multiple GWCC sites noted that sites with active social media groups fared better with group engagement and communication.

This study found that virtual adaptation of GWCC for Spanish-speaking mothers was generally acceptable and feasible. Future studies of virtual and in-person GWCC should consider the impact of telehealth and billing code changes on the feasibility of this care model and continue to explore strategies to maximize engagement of underserved populations with this two-generation approach to pediatric care.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the mothers and pediatric providers who spent time to share their perspectives with us. We would also like to thank Lindsay Cooper and Jami-Lin Williams for their assistance with quantitative data collection.

Grant support

Dr. Weiss-Laxer was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration award number T32HP30035 (PI: Dr. Linda Kahn). Drs. Platt (PI) and Brandt were supported by the National Institutes of Health award number K23MH118431. Dr. Platt’s work on this project was also supported by the Johns Hopkins University Department of Psychiatry. Funders did not play any role in manuscript preparation.

Appendix A

Provider Interview Guide

Provider questions related to implementation of hybrid (virtual group care + in-person well child visits)

1. Tell me about your experience with virtual groups

A. How did it compare with in-person groups?

Probe on content discussed (focus: fidelity)

Specifically, were there areas that you were not able to cover in the new format?

New areas covered (e.g., Covid prevention, Covid impact, other)

Probe on interaction/dynamics (focus: fidelity, acceptability)

Acceptability of providers and patients? Privacy concerns?

Probe on feasibility for clinic staff and for patients

Did you lose patients due to switch in modality? If so, any ideas about patient-level barriers to attendance?

Did you spend more or less time/effort as a result? Did this change require adding more staff time (e.g., technology assistance)?

Benefits, drawbacks in comparison-

for patients

for providers

B. How many virtual groups did you lead? (Age of kids in groups, number of parents attended, whether any started virtual or continued)

Probe on feasibility with additional visit (virtual + in-person); were there patients who opted for in-person only (and opted out of virtual group?); “lost to follow-up” completely?

Describe reasons for these various outcomes

What were the barriers and facilitators to maintaining aspects of group well during Covid-19 pandemic?

2. Can you tell me a little about your experience with the logistics of the groups?

How were they scheduled? Any problems?

How did you bill? Any problems?

Think of costs both in terms of billing and time spent in visit and scheduling

Any technology issues?

If so, what might you recommend in the future to trouble shoot these and better support patients?

Probe on uptake; was it easier or more difficult to schedule patients? To engage with patients once you connected virtually?

3. Given your experience thus far, do you have a strong preference for virtual v. in-person groups?

If you could design a virtual group for your patients, how might you design it?

What would need to change in terms of logistical supports, financing, patient communication, etc. to increase uptake, provider and patient satisfaction?

4. Anything else you would like to tell me?

Appendix B

Mother Interview Guide

Interview with current group well participants and/or LFAB re combination of in-person and group virtual visits

Interest in virtual group format

- If interested, ask about anticipated barriers to participating in virtual group in pediatrics

- Technological – wifi connection, phone or laptop, data

- Time – how has your day changed in quarantine? How could this affect your ability to have a successful group pediatric visit?

- Privacy – do you have a room in your home where you can close the door and speak to the group in private?

- Topics that would like to discuss in group setting

- Who should be present in group discussion?

- Pediatrician needed? Other potential staff who could liaise?

In an in-person visit, there are often screening forms that families are asked to complete. These forms ask questions about mother’s mood, baby’s/child’s development and behavior, and challenges in the home such as lack of money for food. How would you feel about doing these screenings virtually/via telemedicine? This could be having someone ask you questions over the video or phone, or being sent forms to fill out electronically.

- Frequency of in-person visits vs virtual

- Interest in alternating brief in-person with vaccines + generally discussion (monthly contacts, half in-person and half virtual?

- Not sure if that is feasible from pediatrics standpoint?

For those already participating in group visits, interest in continuing group discussion with same cohort?

Virtual groups with fathers who may not be working?

Interview with group well participants who participated in virtual visits

- How did you find the virtual group visit?

- How was it different from in-person?

- Anything better? Anything worse?

- What challenges did you encounter with virtual group?

- Technological

- Probe on use of/familiarity with zoom (including platform used to get onto zoom – phone/laptop – this could have a big impact on how someone interacts w/the group during session)

- Did technology- either yours or another participant’s- get in the way of the visit?

- Privacy

- Ask if they were able to conduct the session in a private area away from partners and potentially children

- Probe on if they had concerns about privacy during the session?

- With other participants

- With other members of the household

- How were your interactions with facilitators (Doctor, Social Worker, Isabel) in the virtual group?

- How were they different from in-person interactions you had in the past?

- How were your interactions with the other mothers or families in the group?

- How different from in-person interactions in the past?

- Did you feel connected to the other mothers in the group in this virtual format? Could you chat with the other mothers like you usually did in the in-person groups? If so, why? If not, why not?

- Do you recall what topics you discussed in the virtual group visit?

- If so, what topics did you discuss?

- How did you find the group discussions about these topics? Were the discussions different in the video format than the in-person format? If so, how?

- Are there topics you think are not appropriate to discuss in the video visit?

- If so, which topics, and why?

- Probe specifically on sensitive topics (mood, partner relationship etc)

- How do you feel about attending future virtual groups if we continue to offer them?

- Would you have interest in attending virtual groups even if in-person groups resume in the future?

- Would you have interest in attending a combination of in person groups and virtual groups?

What topics would you like to discuss in these virtual groups if you plan to attend in the future?

Do you have suggestions about how we might improve virtual groups?

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest or relationship, financial or otherwise, that might be considered as influencing our objectivity, to disclose.

When we refer to patient-centeredness in this paper it is in the context of a parent model of child well-visits and thus we consider the parent-child dyad to be the “patient.”

References

- Badawy SM & Radovic A. (2020) Digital Approaches to Remote Pediatric Health Care Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Existing Evidence and a Call for Further Research. JMIR Pediatrics and Parenting;3(1):e20049. doi: 10.2196/20049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer KW, Chriqui JF, Andreyeva T, Kenney EL, Stage VC, Dev D, Lessard L, Cotwright CJ, & Tovar A (2021). A Safety Net Unraveling: Feeding Young Children During COVID-19. Am J Public Health, 111(1), 116–120. 10.2105/ajph.2020.305980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blundell AR, Kroshinsky D, Hawryluk EB, & Das S (2020). Disparities in telemedicine access for Spanish-speaking patients during the COVID-19 crisis. Pediatr Dermatol, 38, 947–949. 10.1111/pde.14489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centering Healthcare Institute, (2017). Who We Are Retrieved 7/12/2021 from https://www.centeringhealthcare.org/about

- Cheng TL, Emmanuel MA, Levy DJ, & Jenkins RR (2015). Child Health Disparities: What Can a Clinician Do? Pediatrics, 136(5), 961–968. 10.1542/peds.2014-4126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor KA, Duran G, Faiz-Nassar M, Mmari K, & Minkovitz CS (2017). Feasibility of Implementing Group Well Baby/Well Woman Dyad Care at Federally Qualified Health Centers. Acad Pediatr 10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Creswell J (2015). A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Desai S, Chen F, & Boynton-Jarrett R (2019). Clinician Satisfaction and Self-Efficacy With CenteringParenting Group Well-Child Care Model: A Pilot Study. J Prim Care Community Health, 10, 2150132719876739. 10.1177/2150132719876739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillman Carpentier FR, Mauricio AM, Gonzales NA, Millsap RE, Meza CM, Dumka LE, German M, & Genalo MT (2007). Engaging Mexican origin families in a school-based preventive intervention. J Prim Prev, 28(6), 521–546. 10.1007/s10935-007-0110-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa JF, Wadhera RK, Lee D, Yeh RW, & Sommers BD (2020). Community-Level Factors Associated With Racial And Ethnic Disparities In COVID-19 Rates In Massachusetts. Health Aff (Millwood), 39(11), 1984–1992. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, & Redwood S (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol, 13, 117. 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan T, Lill S, & Garcini LM (2021). Another Brick in the Wall: Healthcare Access Difficulties and Their Implications for Undocumented Latino/a Immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health, 1–10. 10.1007/s10903-021-01187-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, & Fitz-Henley J 2nd. (2020). COVID-19 and Parent-Child Psychological Well-being. Pediatrics, 146(4). 10.1542/peds.2020-007294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber LK, Roder-Dewan S, Brockington M, Tabb T, & Boynton-Jarrett R (2019). Parent Perspectives on the Use of Group Well-Child Care to Address Toxic Stress in Early Childhood [Article]. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment and Trauma, 28(5), 581–600. 10.1080/10926771.2018.1539423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gullett H, Salib M, Rose J, & Stange KC (2019). An Evaluation of CenteringParenting: A Group Well-Child Care Model in an Urban Federally Qualified Community Health Center. J Altern Complement Med, 25(7), 727–732. 10.1089/acm.2019.0090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Vallant A, S. G, Roybal C, Gomez-Aguinaga B, Abrams B, Daniel DK, Vargas E, Pena J, Dominguez MS. (2020, June 1 2020). Compliant But Unprotected: Communities of Color Take Greater Action to Prevent the Spread of COVID-19 But Remain at Risk https://iaphs.org/compliant-but-unprotected-communities-of-color-take-greater-action-to-prevent-the-spread-of-covid-19-but-remain-at-risk/?fbclid=IwAR1m0Sv8cJGzyWRlNA8bHT-boYbqUK-6CRfMTLKgZo8RhGGMNPG4CK7Aw6c

- Hibel LC, Boyer CJ, Buhler-Wassmann AC, & Shaw BJ (2021). The psychological and economic toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on Latina mothers in primarily low-income essential worker families. Traumatology, 27(1), 40–47. 10.1037/trm0000293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irigoyen MM, Leib SM, Paoletti AM, & DeLago CW (2020). Timeliness of Immunizations in CenteringParenting. Acad Pediatr 10.1016/j.acap.2020.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jones KA, Do S, Porras-Javier L, Contreras S, Chung PJ, & Coker TR (2018). Feasibility and Acceptability in a Community-Partnered Implementation of CenteringParenting for Group Well-Child Care. Acad Pediatr, 18(6), 642–649. 10.1016/j.acap.2018.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzow MW, Steinway C, & Jan S (2020). Telemedicine and Health Disparities During COVID-19. Pediatrics, 146(2). 10.1542/peds.2020-1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias Gil R, Marcelin JR, Zuniga-Blanco B, Marquez C, Mathew T, & Piggott DA (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparate Health Impact on the Hispanic/Latinx Population in the United States. J Infect Dis, 222(10), 1592–1595. 10.1093/infdis/jiaa474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Nogelo PF, Vázquez M, Ona Ayala K, Fenick AM, & Rosenthal MS (2019). Group Well-Child Care and Health Services Utilization: A Bilingual Qualitative Analysis of Parents’ Perspectives. Matern Child Health J, 23(11), 1482–1488. 10.1007/s10995-019-02798-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield BJ, Rosenthal MS, & Coker TR (2020). Update on the Feasibility, Acceptability, and Impact of Group Well-Child Care. Acad Pediatr, 20(6), 731–732. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt RE, Acosta J, Stellmann J, Sloand E, Caballero TM, Polk S, Wissow LS, Mendelson T, & Kennedy CE (2021). Addressing Psychosocial Topics in Group Well-Child Care: A Multi-Method Study With Immigrant Latino Families. Acad Pediatrics, 22(1), 80–89. 10.1016/j.acap.2021.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, & Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health, 38(2), 65–76. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health, 36(1), 24–34. 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Diaz CE, Guilamo-Ramos V, Mena L, Hall E, Honermann B, Crowley JS, Baral S, Prado GJ, Marzan-Rodriguez M, Beyrer C, Sullivan PS, & Millett GA (2020). Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Ann Epidemiol, 52, 46–53.e42. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoli JM, Lindley MC, DeSilva MB, Kharbanda EO, Daley MF, Galloway L, Gee J, Glover M, Herring B, Kang Y, Lucas P, Noblit C, Tropper J, Vogt T, & Weintraub E (2020). Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Routine Pediatric Vaccine Ordering and Administration - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 69(19), 591–593. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schor EL (2004). Rethinking well-child care. Pediatrics, 114(1), 210–216. 10.1542/peds.114.1.210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini RA, Powell SK, Frere JJ, Saali A, Krystal HL, Kumar V, Yashaswini C, Hernandez J, Moody K, Aronson A, Meah Y, & Katz CL (2021). Psychological distress in the face of a pandemic: An observational study characterizing the impact of COVID-19 on immigrant outpatient mental health. Psychiatry Res, 295, 113595. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddard J, & Kaufman J (2020). Coronavirus Impact Scale [Scale] https://www.nlm.nih.gov/dr2/COVID-19_BSSR_Research_Tools.pdf

- Vargas ED & Sanchcez GR (2020). COVID-19 Is having a devastating impact on the economic well-being of Latino families. Journal of Economics, Race and Policy, 3(4), 262–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]