Abstract

Objective

Nicotine pouch products are an emerging and rapidly growing smokeless tobacco (ST) category in the USA. Little is known about the promotional strategies and media channels used to advertise this ST category or the extent to which the marketing strategies differ from strategies used to promote ‘conventional’ smokeless products (eg, snuff). We describe the nature, timing of and expenditures related to conventional, snus and newer ST product advertising on print, broadcast and internet media.

Methods

Advertising expenditures were collected using Kantar Media’s ‘Stradegy’ tool, which provides advertising data including dollars spent promoting specific products across various media channels, including print magazines and newspapers, broadcast television and radio, outdoor posters and billboards, and internet. We identified 306 smokeless products within Kantar database and collected ad expenditures retrospectively for January 2018–April 2020. Promotional expenditures were aggregated by product category, by month and by designated market area (DMA).

Results

Kantar data analysis returned 28 conventional ST, 22 oral nicotine and 3 snus products (53 total) advertised during the period of observation, with over $71 million spent collectively on ST promotion. Across categories, more advertising dollars were spent on conventional ST products (63%) than newer oral nicotine products (25%) or snus (12%). However, during the later 9-month period from August 2019 to April 2020, oral nicotine products accounted for the majority of monthly ad spending. Most ad spending was placed in the national market ($66.5 million), with Atlanta ($1.1 million), Houston ($1 million) and Las Vegas ($0.8 million) as the top three local DMAs for expenditures.

Discussion

Advertising expenditures for nicotine pouches have recently exceeded conventional ST product advertising and nicotine pouches are being promoted nationally. Marketing surveillance as well as understanding consumer appeal, perceptions and consumption are critical next steps in tracking potential uptake of these new products.

Keywords: Media, Advertising and Promotion, Tobacco industry

KEY MESSAGES.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Smokeless tobacco product landscape is rapidly changing with the emergence of newer oral nicotine pouch products on the US market.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

We examined the amount and nature of conventional and newer smokeless tobacco product advertising expenditures on print, broadcast and internet media.

We found that promotional spending for smokeless tobacco shifted from conventional products (eg, moist snuff) to newer nicotine pouches during the study period.

Nicotine pouches were predominantly advertised on television, likely due to the lack of regulation of broadcast media promotion of tobacco-free nicotine products.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Marketing surveillance as well as understanding consumer appeal, perceptions and consumption are critical next steps in tracking potential uptake of these new products.

Stronger marketing regulations can curb exposure to smokeless product advertisement among novices and young people.

Introduction

Nicotine pouches are a rapidly growing smokeless tobacco (ST) category in the USA. Similar to snuff (dry or moist tobacco leaf in packets) or snus (a variant of pouched dry snuff originating from Sweden), these products are portioned in pouches, but instead of containing tobacco leaf they hold nicotine powder.1 Prominent brands in the USA are produced by major cigarette and cigar product manufacturers, including Velo (RJ Reynolds), Zyn (Swedish Match), Rogue (Swisher International) and On! (Altria).2 3 Other emerging brands introduced by independent manufacturers are NIIN (or ‘Nicotine Innovated’), Rush, Nic-S, Lucy, Black Buffalo and Fre.2 4 These products come in a variety of flavours (eg, mint, fruit and candy flavours) and contain different amounts of nicotine. For instance, Zyn products range from 3 mg to 6 mg of nicotine; Velo pouches are available in 2 mg, 4 mg and 7 mg nicotine strength options.2 Some brands feature as much as 12 mg (Fre) and 20 mg (Faro) of nicotine per pouch. Additionally, several brands (eg, Fre, NIIN) indicate that they use synthetic nicotine in their pouch products, with claims that their products are formulated to remove such known carcinogens as tobacco-specific nitrosamines.5

The ‘tobacco-free nicotine’, ‘non-tobacco’ and ‘synthetic nicotine’ claims and potential reduced risk statements used by brands, vendors and marketers to promote newer ST products have not been verified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and may be misleading.6 7 It is unclear whether any newer smokeless brands have submitted an application to receive modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) status from FDA, that is, a designation that tobacco product poses lower health risks to individual users and the population as a whole when compared with existing products on the market.8 While switching to newer ST could reduce morbidity and mortality among smokers who are unable to quit, the products also have potential to attract and addict a new generation to tobacco. In particular, the availability of flavours, high nicotine content and ‘tobacco free’ claims are likely to be appealing to youth.9 10

Nicotine pouches, which were introduced in 2016, grew to 4.0% in market share by 2019.11 While this market is rapidly growing, nicotine pouches are also competing in an increasingly diverse nicotine product landscape. New product categories and brands of smokeless and nicotine products (eg, nicotine gums, lozenges, sticks) continue to emerge despite FDA actions to limit the sales of flavoured products.12–14

Furthermore, the FDA recently approved modified risk claims for several General snus products indicating that use of those brands results in lower harm of various tobacco-related illness compared with cigarette use.15 These MRTP marketing orders may affect consumers’ perceptions of other oral nicotine products, such as nicotine pouches. The growth and diversification within the smokeless market have raised both regulatory questions and health concerns, particularly as they relate to youth who are using tobacco and nicotine products, including flavoured varieties.16

Use of these products may encourage dual or poly-tobacco product use. Indeed, evidence suggests that youth never-tobacco users who try ST products are more likely to try cigarettes and e-cigarettes 1 year later17 and nearly two-thirds of youth who reported using ST products also used at least one other tobacco product.18

The transformation of the ST product landscape coincided with changes in the tobacco regulatory environment. The 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act required ST packages and advertisements to have larger and more visible warning labels.19 In recent years, some localities in states such as California and Massachusetts banned all flavoured tobacco products, including ST products.20 The way in which ST products are taxed has also shifted, resulting in reduced taxes for consumers of these products.11 21 These regulatory changes likely have affected how tobacco companies market ST products.

Understanding where and how the industry is promoting newer oral tobacco products is important to predict population uptake and public health impact. The latest Federal Trade Commission (FTC) report that tracks industry spending for ST marketing does not include these products.22 Our analyses describe the nature, timing of and expenditures for ‘conventional’/older (eg, snuff), snus and newer ST product categories on print, broadcast and internet media. Comparative analysis of the marketing expenditures for conventional, snus and newer smokeless products can help shed light on unique strategies used to promote each of these ST categories and elucidate whether the channels used to promote newer products differ from the traditionally used channels and potentially reach a new audience to help expand the consumer base.

Methods

Data collection

We employed Kantar Media’s ‘Stradegy’ tool to estimate US advertising expenditures for ST products from January 2018 to April 2020. Kantar’s estimates are based on rate cards provided by publishers, television (TV) and radio networks, and advertising agencies to forecast the cost of advertising placement. We searched the Stradegy database using ST-related terms (such as nicotine, nic, snus, pouch, gum, stick, lozenge, pellet, strip, dissolvables), established brand names (such as Copenhagen, Grizzly and Skoal) and emerging ST brand names (such as Velo, Zyn and On!). We also reviewed all products falling under the same Kantar Stradegy categories as the products we used in our initial searches based on the established brand names. Relevant product categories included ‘cigar & tobacco’ and ‘smoking deterrents’ categories, which yielded additional ST products. We identified 297 smokeless products in the Kantar database and collected ad expenditures retrospectively for the time period from January 2018 through April 2020.

Analysis

Marketing expenditures were aggregated by month and media type: TV (local and national), print (local and national magazines and newspapers, in English and Spanish), radio (local and national), internet (standard web and mobile device types) and outdoor (billboard, poster, etc). Promotional expenditures were also aggregated by designated market area (DMA) and product category: conventional ST (eg, dip, moist and dry snuff, chewing tobacco), snus (an established variant of pouched dry snuff) and newer oral nicotine ST products (eg, nicotine pouches and lozenges). Finally, within each product category we reviewed the specific products with highest advertising expenditures.

Results

There were 53 ST products advertised during the period of observation, with a total of $71.7 million in advertising expenditures collectively. Among ST categories, conventional ST products accounted for 63% ($45.2 million) of the total ($71.1 million), followed by newer oral nicotine products (25%, $18 million) and snus (12%, $8.5 million). Of the 22 oral nicotine products (ie, nicotine pouches, toothpicks, gums, sprays, tablets and lozenges), 5 pouch products accounted for 97% ($17.4 million) of oral nicotine expenditures ($18 million). Most ad spending was placed in the national market ($66.5 million or 92.7%), with Atlanta ($1.1 million), Houston ($1 million) and Las Vegas ($0.8 million) emerging as the top three DMAs for localised expenditures.

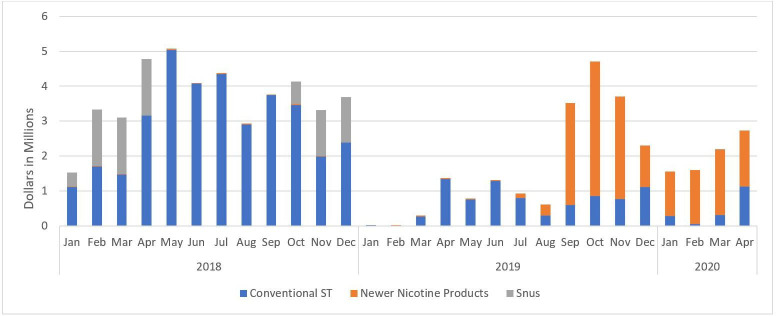

Figure 1 shows the monthly expenditures for ST marketing by product category across time, from January 2018 through April 2020. Notably, all product categories approached zero ad spending in January and February of 2019 and overall spending remained relatively low through August of that year. However, during the 9 months between August 2019 and April 2020, overall ST expenditures increased, with newer oral nicotine products largely replacing conventional ST advertisement spending.

Figure 1.

Amount of smokeless tobacco (ST) marketing expenditures by product category from January 2018 to April 2020. Each stacked bar shows the proportion of expenditures by product category.

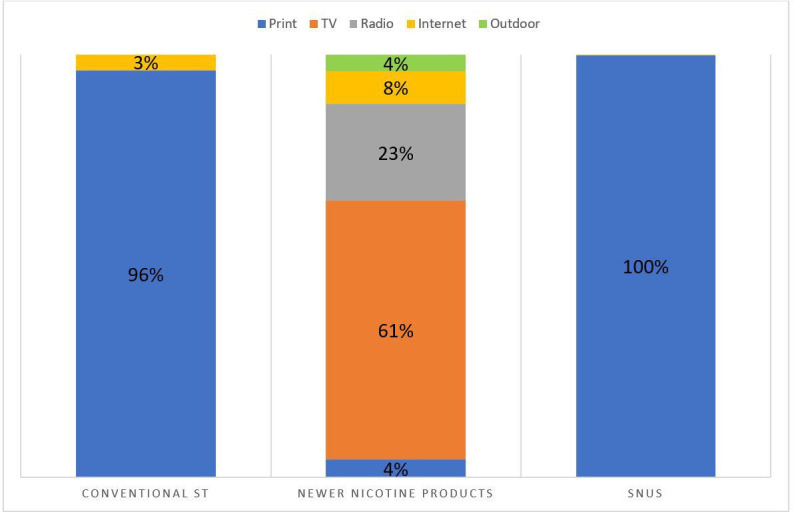

Figure 2 shows the proportion of advertising for each product category by media type. Over 96% of advertising dollars for both conventional ST and snus were spent on print advertising. However, the majority (61%) of the spending on oral nicotine ST promotion was for TV advertising. Almost a quarter (23%) of oral nicotine ST promotion dollars were spent on radio and the remaining dollars were spent on internet ads (8%), print ads (4%) and outdoor ads (4%).

Figure 2.

Proportion of smokeless tobacco advertising expenditures by product category by media type. ST, smokeless tobacco; TV, television.

Top advertisers of conventional ST products included U.S. Smokeless Tobacco Company (USSTC, Altria subsidiary), which spent more than $14 million advertising a prominent moist snuff brand. The second, third and fourth highest levels of ad expenditures for specific conventional ST product brands ranged between $4.8 and $5.6 million during the same period. RJ Reynolds spent the most among newer tobacco product manufacturers ($16.6 million), distantly followed by Swedish Match ($0.67 million). This vast discrepancy is likely because the RJ Reynolds product was introduced to the market in 2019, while the Swedish Match product was introduced earlier in 2016 and was already a market leader.23 24

Discussion

Advertising expenditures for nicotine pouches have recently exceeded those for conventional ST and account for the majority of spending for newer nicotine product marketing. Five nicotine pouch products accounted for 97% of expenditure for oral nicotine (ie, pouches, toothpicks, gum, spray, tablets and lozenges). It is noteworthy that while most ad spending was placed in the national market, Atlanta, Houston and Las Vegas emerged as the top three DMAs based on the amount of expenditures, which may be due to the fact that these areas were test markets for oral nicotine products (eg, Velo).25 Both newer and conventional smokeless products were promoted on media channels easily accessible to youth. Namely, while the majority of conventional and snus advertisement expenditures were placed on print media, over 60% of spending on nicotine pouch promotion was allocated for TV advertising. There is a robust body of evidence that exposure to tobacco product marketing is associated with youth initiation, across a variety of products.26–29 Thus, there is no reason to expect that promotion of newer ST products would be an exception. Further, marketing of these products may encourage dual or poly-use since youth who try ST products are more likely to try combustible and e-cigarette products.17 18

Despite potentially lower health risks compared with combustible products, newer smokeless products also have potential to addict a new generation to tobacco. Testing of newer smokeless products finds high levels of nicotine which may be associated with increased risk of dependence.30 The FDA should evaluate the reduced risk claims of ST products, including newer oral tobacco products, to help ensure that young users are not misled. Furthermore, if any nicotine pouch products are approved for modified risk, the FDA should ensure that these products are not marketed using strategies that appeal to youth. Public health and tobacco control professionals can contribute to the effort to reduce youth tobacco and nicotine use by educating parents and children about the tobacco industry’s role in developing newer products to attract new users.

Limitations

The study is not without limitations. Kantar expenditures data capture mass media and outdoor ads, but not point-of-sale marketing, direct-to-consumer mail or email marketing, or social media marketing. Other research demonstrates that direct mail ST marketing (including for newer products) was prevalent in 2018–2020, with 38 million pieces of newer smokeless direct mail advertisements sent to US consumers during the time period from March 2018 to August 2020.6 31 In addition, while the Kantar database includes internet advertising data, it cannot capture some important types of online marketing—influencer partnerships or social media campaigns that do not pay to promote posts, for example.

Our findings revealed that there was a retrenchment in ST advertising in January–February 2019, and while we are unsure what caused the spending decline these results are in line with estimates from the FTC Smokeless Tobacco report which shows a 12.5% reduction in advertising and promotional expenditures from 2018 to 2019.32 Despite limitations, this paper provides needed data on newer ST marketing practices beyond what is publicly available in FTC reports.

Conclusions

This analysis provides early surveillance of the introduction of a nicotine pouch product to the market. Promotional spending for ST shifted from conventional products and snus in 2018 to primarily newer oral nicotine pouches towards the end of 2019 and into early 2020. Newer ST products are not regulated in the same way as conventional ST products. While it is unlawful to advertise conventional ST on TV, newer ST products, which claim to be ‘tobacco-free’, have evaded regulation thus far. Thus, TV audiences recently saw ads for ST products for the first time since 1986.33 34 Continued marketing surveillance as well as research to understand consumer appeal, perceptions, sales and consumption are critical next steps in tracking potential uptake and the public health impact of these new products.

Footnotes

Twitter: @sherryemery, @ShyanikaRose

Contributors: SLE, SB, SWR and GK together designed the study. SB and GK conducted data analysis. SLE, GK, SB and SWR contributed to data interpretation. SB and CCC wrote the first draft. SLE, GK and SWR revised the draft. The final version of the paper has been reviewed and approved by all coauthors.

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA234082. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Food and Drug Administration . Smokeless tobacco products, including dip, snuff, Snus, and chewing tobacco, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robichaud MO, Seidenberg AB, Byron MJ. Tobacco companies introduce 'tobacco-free' nicotine pouches. Tob Control 2020;29:e145–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Talbot EM, Giovenco DP, Grana R, et al. Cross-promotion of nicotine pouches by leading cigarette brands. Tob Control 2023;32:528–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Truth Initiative . What you need to know about new synthetic nicotine products, 2021. Available: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/harmful-effects-tobacco/what-you-need-know-about-new-synthetic-nicotine-products

- 5. Chu Delos Reyes N. NIIN nicotine pouches are Upping the game for tobacco-free alternatives. Newsweek, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Czaplicki L, Patel M, Rahman B, et al. Oral nicotine marketing claims in direct-mail advertising. Tob Control 2022;31:663–6. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. O'Connor R, Durkin SJ, Cohen JE, et al. Thoughts on neologisms and pleonasm in scientific discourse and tobacco control. Tob Control 2021;30:359–60. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Food and Drug Administration . Modified risk tobacco products, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Villanti AC, Johnson AL, Glasser AM, et al. Association of flavored tobacco use with tobacco initiation and subsequent use among US youth and adults, 2013-2015. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1913804. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.13804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kostygina G, Ling PM. Tobacco industry use of flavourings to promote smokeless tobacco products. Tob Control 2016;25:ii40–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delnevo CD, Hrywna M, Miller Lo EJ, et al. Examining market trends in smokeless tobacco sales in the United States: 2011-2019. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:1420–4. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kostygina G, Kreslake JM, Borowiecki M, et al. Industry tactics in anticipation of strengthened regulation: bidi vapor unveils non-characterising bidi stick flavours on digital media platforms. Tob Control 2023;32:121–3. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-056502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Diaz MC, Donovan EM, Schillo BA, et al. Menthol e-cigarette sales rise following 2020 FDA guidance. Tob Control 2021;30:700–3. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kostygina G, England L, Ling P. New product marketing Blurs the line between nicotine replacement therapy and smokeless tobacco products. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1219–22. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . FDA grants first-ever modified risk orders to eight smokeless tobacco products, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Editor..National Institute on Drug Abuse . Study: surge of teen vaping levels off, but remains high as of early 2020. N.I.o.D. Abuse, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaffee BW, Cheng J. Tobacco product initiation is correlated with cross-product changes in tobacco harm perception and susceptibility: longitudinal analysis of the population assessment of tobacco and health youth cohort. Prev Med 2018;114:72–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;64:381–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Food and Drug Administration . Regulations restricting the sale and distribution of cigarettes and smokeless tobacco to protect children and adolescents. Final rule, in Fed Regist, 2010: 13225–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Truth Initiative . Local flavored tobacco policies 2021 Q1, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hrywna M, Grafova IB, Delnevo CD. The role of marketing practices and tobacco control initiatives on smokeless tobacco sales, 2005–2010. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:3650. 10.3390/ijerph16193650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Federal Trade Commission . Smokeless tobacco report for 2020, 2021. Available: https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/federal-trade-commission-cigarette-report-2020-smokeless-tobacco-report-2020/p114508fy20smokelesstobaccop114508fy20smokelesstobacco.pdf

- 23. RJ Reynolds Vapor Company . R.J. Reynolds Vapor Company Announces VELO - Expanding Emerging Modern Oral Portfolio and Choice for Adult Tobacco Consumers. PR Newswire, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Reid Blackwell J. With its non-tobacco Zyn product, Swedish match is a leader in a growing category of alternative nicotine products. Richmond Times, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hammond H. R.J. Reynolds Releases Velo Dissolvable Nicotine Lozenges. CSP Daily News, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Evans N, Farkas A, Gilpin E, et al. Influence of tobacco marketing and exposure to smokers on adolescent susceptibility to smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst 1995;87:1538–45. 10.1093/jnci/87.20.1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, et al. Tobacco industry promotion of cigarettes and adolescent smoking. JAMA 1998;279:511–5. 10.1001/jama.279.7.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Soneji S, Pierce JP, Choi K, et al. Engagement with online tobacco marketing and associations with tobacco product use among U.S. youth. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:61–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pierce JP, Sargent JD, White MM, et al. Receptivity to tobacco advertising and susceptibility to tobacco products. Pediatrics 2017;139. 10.1542/peds.2016-3353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stanfill S, Tran H, Tyx R, et al. Characterization of total and unprotonated (free) nicotine content of nicotine pouch products. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:1590–6. 10.1093/ntr/ntab030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Czaplicki L, Rahman B, Simpson R, et al. Going smokeless: promotional features and reach of US smokeless tobacco Direct-Mail advertising (July 2017-August 2018). Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:1349–57. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Federal Trade Commission, . Federal Trade Commission cigarette report for 2019 and smokeless tobacco report for 2019, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Truth Initiative . What do tobacco advertising restrictions look like today? 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34. VELO . VELO nicotine pouches TV spot. 'Hassle-Free and Just for Me' 2021. [Google Scholar]