Significance

Women’s underrepresentation at higher levels in academia negatively impacts the course of scholarly activities. One criterion for judging who reaches higher levels of academia is student-provided teaching evaluations. Here, we illustrate that both men and women suffered from gender-based discrimination in their teaching evaluations. However, women were more frequently impacted because of their minority status. When students observed gender disparities in academic departments in our experimental paradigm, they formed expectations about gendered roles for upper- and lower-level courses. Violating these expectations caused gender-based discrimination in teaching evaluations. Left unaddressed, these gender biases can undermine diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts. This article provides evidence to support those who seek to implement interventions that lead to equity and gender parity.

Keywords: gender bias, teaching evaluations, university policy

Abstract

Women are underrepresented in academia’s higher ranks. Promotion oftentimes requires positive student-provided course evaluations. At a U.S. university, both an archival and an experimental investigation uncovered gender discrimination that affected both men and women. A department’s gender composition and the course levels being taught interacted to predict biases in evaluations. However, women were disproportionately impacted because women were more often in the gender minority. A subsequent audit of the university’s promotion guidelines suggested a disproportionate impact on women’s career trajectories. Our framework was guided by role congruity theory, which poses that workplace positions are gendered by the ratios of men and women who fill them. We hypothesized that students would expect educators in a department’s gender majority to fill more so essential positions of teaching upper-level courses and those in the minority to fill more so supportive positions of teaching lower-level courses. Consistent with role congruity theory when an educator’s gender violated expected gendered roles, we generally found discrimination in the form of lower evaluation scores. A follow-up experiment demonstrated that it was possible to change students’ expectations about which gender would teach their courses. When we assigned students randomly to picture themselves as students in a male-dominated, female-dominated, or gender-parity department, we shifted their expectations of whether men or women would teach upper- and lower-level courses. Violating students’ expectations created negative biases in teaching evaluations. This provided a causal link between department gender composition and discrimination. The importance of gender representation and ameliorating strategies are discussed.

Women’s underrepresentation at higher levels in academia is well documented (1). A variety of metrics are considered during tenure and promotion decisions. Critical among them are course evaluations provided by students of the faculty member applying for promotion. Oftentimes these evaluations are the only metric by which individuals are judged for their teaching efforts (2). To illustrate this point, our audit of promotion guidelines at the university where these studies were conducted revealed that student course evaluations played an instrumental role in virtually all tenure and promotion decisions (94%). Problematic to the reliance on course evaluations and particularly relevant to the research at hand, is the nature of the evaluation scores themselves. Typical evaluation scores fall within a fraction of a point of one another (3). This is because students will distinguish a “good” from an “excellent” educator with what would seem to be trivial differences in evaluation scores, e.g., a 4.43 versus a 4.60 on the frequently used 1 to 5 scale. Oftentimes promotion guidelines require excellence in teaching. Therefore, small differences in scores could be meaningful in the tenure and promotion process. If gender bias creates differences in evaluation scores, those differences have the potential to be problematic for advancement.

Student teaching evaluations are a convenient, student-centered metric used to inform educators, advisors, curriculum committees, and promotion committees of the quality of instruction provided by individuals, courses, and departments. As commonly as student-provided evaluations are used, they are criticized for being retrospective self-reports that also measure unintended factors such as attractiveness (4) and lenient grading (5). Despite these flaws, for the foreseeable future they are the prevailing method to evaluate teaching for tenure and promotion decisions. Therefore, for purposes of equity it is important to identify biases in student provided teaching evaluations so that adjustments can be made to the way that these scores are interpreted.

Gender is a fundamental aspect in person perception (6). It stands to reason that gender also could be a chief aspect in students’ perceptions of their educators. Indeed, for more than 70 y, researchers using laboratory experiments have shown how students can rate women’s teaching as inferior to men’s in their teaching evaluations (2, 3, 7–9). However, when investigating real-world data, straightforward biases have not always been found (10–13). These discrepancies leave university policy decision-makers with inconsistent evidence as to how to best combat bias. Framed within Eagly et al.’ role congruity theory (14, 15), we provide documentation of gender bias in teaching evaluations that illustrates when one might expect to see bias and when one would not. We provide evidence from both university-wide and experimental data drawn from the same student body to reveal how students’ expectations of their educator’s gender may be formed and how violating those expectations can impact teaching evaluations.

Role Congruity Theory

The authors of role congruity theory (14, 15) proposed that when workers in a specific role are predominantly men or women, those roles become gender typed, that is people hold expectations that the role should be filled by the gender they have observed within that role. These effects intensify as gender disparities within roles increase (16). Moreover, people develop general beliefs that those who fill gender-typed positions should possess the stereotypical traits of the gender type. Thus, people in masculine-typed positions should be agentic. They are essential to move forward the workplace’s goals. In contrast, those in feminine-typed positions should be communal. These people should be supportive and concerned with the welfare of others within the workplace (17, 18). As a consequence the more masculine or feminine typed a workplace position is, the more the position is considered appropriate for only that gender (16). Thus, both men and women can be evaluated poorly when they violate an expected gender role (19–21). Meta-analyses of industries with differing gender compositions and lab studies in which gender roles were manipulated show that these gender-role biases successfully predict discrimination against women when they are in positions in which men would be expected, and discrimination against men when they are in positions in which women would be expected (22–24). For example, women are judged more harshly than men in masculine-typed science careers, but more positively than men in feminine-typed nursing and early childhood education careers (24).

Similarly to what has been documented in industry roles, the more male or female dominated a university department is the greater the gender-role expectation is for its members (25). A gender imbalance cues whether the norm or the “true” members of that department should be men or women (14, 26). This could account for why students systematically provide lower teaching evaluations for women than men when those data are collected in male-dominated academic departments (2, 3, 7). Researchers who study gender biases in teaching evaluations have used persuasive experimental studies in which the same written lectures (27) or online courses (28) are described as having been taught by a man or a woman. In such studies students provided higher ratings for men than women. Yet, notably these studies were conducted in male-dominated fields. In the three instances in which researchers considered university-wide evaluations and each department’s gender composition, biases against female educators were found in male-dominated but not female-dominated departments (10, 12, 13). These university-wide investigations did not parallel role congruity research precisely, i.e., symmetrical biases were not found against both men and women. However, the university-wide investigations did not parallel the specificity of role congruity research.

Theory in Context.

To make better predictions we must consider how role congruity theory applies to specific positions within the context of a workplace (29). We pose that whether women or men are negatively evaluated depends on if they fill essential or supportive positions within a given workplace context. For example, role congruity theory would predict that in the United States, the position of auto mechanic is masculine typed because 98.1% of mechanics in the United States are men (30). Thus, a woman who works in an auto repair shop would be expected to be evaluated more poorly for filling an essential role of a mechanic. However, she would not be evaluated negatively for filling a supportive role by working in the office to schedule customer appointments. For another example, a woman will be poorly evaluated in the essential role of a manager when that job is typically filled by men (22). However, it was never suggested that a woman would be evaluated poorly when she was in the supportive role as a manager’s secretary. The nuance of essential versus supportive roles also should apply to university departments. A gender imbalance within a department could cue students as to which gender is considered primary or essential and which gender should fill supportive roles. That is, students may think of educators in the gender majority as agentic legitimate members of the department—filling essential roles and those in the gender minority as more communal supportive members—filling supportive roles.

To understand whether a student would expect an essential or supportive-typed educator to teach his or her course, we considered the importance of the course level. Upper-level courses typically have students who are maturing in their chosen discipline, situated within smaller class settings that delve into topics with greater depth. In general, students consider upper-level courses essential to their mastery of their chosen fields, and they expect bonafide experts of that field to be their educators (31). Those in the gender majority are more so considered true and legitimate members of the department (14, 26, 32). Therefore, students might expect those in the gender majority to fill these essential roles of teaching upper-level courses. Inversely, those in the gender minority might be expected to serve supportive roles by teaching lower-level courses. lower-level courses cater to younger students who may be exploring their interests, aptitudes, and fits within a field. Students in lower-level courses are less concerned about their educators’ expertise (31). Thus, gendered expectations as to whom will teach upper- versus lower-level courses may be influenced by a department’s gender composition.

The Interplay of Broader Gender Stereotypes and Gender Roles.

The framework described above does not take into consideration the role of broader gender stereotypes for men and women. Stereotypes are predominant consensual beliefs about the attributes of social categories. Those who research gender stereotypes find that men are presupposed to be agentic and women communal (33, 34). There is abundant research on the interplay of gender stereotypes and gender roles in regard to essential or leadership positions. In essential positions within male-dominated fields, there is a consistency between gender stereotype content and gender roles as defined by role congruency theory, i.e., agentic men fill essential positions. However, there is a tension between gender roles and broader gender stereotypes in female-dominated fields. Role congruity research shows us that women can fill essential positions in female-dominated domains without being evaluated negatively. This contradicts what broader stereotypes would suggest, i.e., that men fill essential roles (35). In part, this contradiction can be explained by the fact that female-dominated fields such as nursing or early childhood education are viewed as more communal, that is interpersonal, nurturing, and supportive (17). Therefore, women may be expected to fill essential positions in communal fields because women are seen as genuinely legitimate members of those fields. The same cannot be said for men. Men are penalized for taking on key positions in female-dominated fields (14). For example, when men enter early education jobs they are evaluated poorly (24), viewed suspiciously (36), and they are criticized for doing women’s work (24). These findings and others (37–39) show that there are instances when women—not men, are expected in essential positions. This suggests that gender roles can and do override gender stereotypes.

Less studied is the interplay between gender roles and gender stereotypes in nonessential, supportive positions. On the one hand if viewed through the lens of role congruity theory, individuals in the gender minority should be expected to fill supportive positions. One the other hand, if viewed through the lens of gender stereotypes, women—not men—should be expected to serve in supportive positions regardless of the domain. We lean toward the first possibility. As discussed above, gender roles have been found to override gender stereotypes. Additionally, there are some examples to support this notion in the literature. For instance, in male-dominated office domains women are evaluated more favorably than men in subordinate positions (39). In the traditionally male-dominated domain of family breadwinning, marriages have better outcomes when wives play a supporting part in earning the family income than when wives take on the essential position of breadwinner (40). In the female-dominated domain of family caregiver, men are evaluated negatively for filling the essential caregiving role of stay-at-home fathers (41) or for taking extended family leave, which signals a primary caretaking position (42). Yet, men are viewed more positively than are women when they fill supportive roles in female domains, such as reducing work hours to help out with the family’s needs (43) or taking shorter leaves from work for supportive or interim caretaking (42). It seems that those in the gender minority are not penalized for entering gender incongruent domains when they are simply facilitating the more supposedly genuine members of that domain.

The Present Research.

We investigated these dynamics in an archival investigation in study 1 and an experimental investigation in study 2. In study 1, we would expect the findings in our real-world archival data to closely resemble what has been found previously in role congruity research because the departments in university settings resemble work settings outside of academia (14). Unless a university has actively worked to address gender disparities, gender disparities in academe mirror gender disparities seen in professions more generally. For example, 88.5% of nurses are women and 84.8% of nursing professors are also women (44). Similarly, in our real-world university data, the top female-dominated departments included nursing and education and the top male-dominated departments included engineering and science. In study 1, our hypotheses were as follows. We expected that those educators who had gender-role congruency would have higher teaching evaluations than those educators who had gender-role violations. Therefore (H1), we predicted that those in the gender majority would be evaluated more positively for upper-level courses than those in the gender minority. As has been found in past research (H2), we expected the effects of gender-typed roles to be strongest in departments with the greatest gender disparities. We also predicted (H3) that those in the gender minority would be evaluated more positively for lower-level courses than those in the gender majority. We made this last prediction with the acknowledgment that little research has been done to evaluate gender role dynamics in lower-level positions.

Study 1

Study 1 was an archival investigation of student evaluations collected from courses with 115,467 students enrolled in all 51 departments within seven colleges at a US public R1 university. We examined how department gender composition and course level interacted with the gender of the educator to predict student evaluation scores. The teaching evaluations were 11 items that measured students’ perceptions of their educators’ effectiveness as a teacher. Students were asked for their agreement to statements such as, “The instructor’s teaching methods helped me understand the course material,” and “Overall, the instructor is an effective teacher.” Response options were provided with a Likert-type scale of 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. Please see the SI Appendix for details.

Results Study 1.

For context, we provide descriptive statistics here. Our university-wide sample consisted of course evaluations from 1,885 educators who taught 4,700 courses in the 2018 to 2019 academic year. Educators taught far more upper-level (72.3% were level 3,000 and above) than lower-level courses (27.7% were 1,000 or 2,000 level). Additionally, in 72.6% of the departments within this university women were in the gender minority. Not the central focus of this article but worthy of mention, two main effects were apparent in our analysis. First, as the percentage of male educators rose in a department, teaching evaluations fell, b = −0.271, SE = 0.087, df = 45.49, t = 3.12, P = 0.003. This is consistent with previous research that attributed these differences to the fact that male-dominated departments are more likely to be in highly analytical fields, which are evaluated with lower scores on average than other fields more generally (13, 31). Additionally, female students in general provide higher teaching evaluation scores than do male students and female-dominated departments have more female students (12). Second, as course level rose so did evaluation scores, b = 0.019, SE = 0.005, df = 3,816.63, t = 4.22, P < 0.001. This is also consistent with past research that attributed this increase in scores to students’ greater interest in their courses as they progress within their chosen fields. Furthermore, students may receive more personal attention in upper-level courses due to smaller class sizes (31).

In the university-wide data, we found support for hypotheses H1, H2, and H3. There was a significant three-way interaction between department gender composition, course level, and educator gender (1 = female, 0 = male), b = −0.157, SE = 0.046, F(1, 4,487.85) = 11.47, P < 0.001, effect size partial η2 = 0.338 [η2 estimated through model variances (45)]. The three-way interaction term indicated that as gender disparity rose within a department, the two-way interactions between course level and educator gender changed. To decompose the three-way interaction we used slope difference tests for linear models (46). They provided an estimate similar to a two-way interaction term (46, 47), but through directly testing if simple slopes are different. We found significantly different slopes for men and women teaching upper and lower-level courses in male-dominated (+1 SD percentage of men, b = −0.176, t = −2.22, P = 0.027, 95% CI −0.332, −0.020) and female-dominated departments (−1 SD percentage of men, b = 0.214, t = 2.82, P = 0.005, 95% CI 0.065, 0.363). However, the simple slopes were not different in departments closer to gender parity (mean percentage of men, b = 0.019, t = 0.369, P = 0.713, 95% CI −0.083, 0.121). Please see Table 1 and Fig. 1, and the SI Appendix for details on all estimates, model, and covariates.

Table 1.

Detailed results from the three-way interaction in study 1: Archival study

| Estimates | Simple slope statistics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | Course level | Model estimates for women’s scores | Model estimates for men’s scores | Unstandard simple slope, women’s–men’s scores* | Standardized simple slope, women’s–men’s scores† | |||

| Slope significance test | ||||||||

| t | P | |||||||

| Direct contrasts between men and women | Majority men (+1 SD) | Upper | 4.282 | 4.368 | −0.086 | −0.145 | −2.300 | 0.021 |

| Lower | 4.241 | 4.152 | 0.090 | 0.151 | 1.427 | 0.154 | ||

| Mean gender composition | Upper | 4.381 | 4.366 | 0.015 | 0.026 | 0.601 | 0.548 | |

| Lower | 4.286 | 4.290 | −0.004 | −0.006 | −0.100 | 0.920 | ||

|

Majority women (−1 SD) |

Upper | 4.480 | 4.363 | 0.117 | 0.196 | 3.346 | 0.001 | |

| Lower | 4.331 | 4.428 | −0.098 | −0.163 | −1.623 | 0.105 | ||

| Department | Gender | Model estimates for scores in upper-level courses | Model estimates for scores in lower-level courses | Unstandard simple slope, upper–lower scores* | Standardized simple slope, upper–lower scores† | |||

| Slope significance test | ||||||||

| t | P | |||||||

| Direct contrasts between upper- and lower-level courses | Majority men (+1 S D) | Women | 4.282 | 4.241 | 0.041 | 0.067 | 0.597 | 0.550 |

| Men | 4.368 | 4.152 | 0.217 | 0.363 | 4.540 | <0.001 | ||

| Mean gender composition | Women | 4.381 | 4.286 | 0.095 | 0.159 | 2.273 | 0.023 | |

| Men | 4.366 | 4.290 | 0.076 | 0.127 | 2.072 | 0.038 | ||

|

Majority women (−1 SD) |

Women | 4.480 | 4.331 | 0.150 | 0.251 | 3.227 | <0.001 | |

| Men | 4.363 | 4.428 | −0.065 | −0.108 | 0.994 | 0.320 | ||

*Unstandardized evaluation scores.

†Standardized evaluation scores (z-scored).

†Linear model probed at: upper-level 4,000 course = 1, lower-level 1,000 course = 0; majority men = +1 SD percentage of men in department, majority women = −1 SD percentage of men in department.

Fig. 1.

Illustrated are the findings from the archival study (N = 4,700) in which department gender composition and course-level significantly predicted teaching evaluation scores for men and women differently. In male-dominated departments, women tended to have higher evaluations than did men in lower-level courses; in upper-level courses men had higher evaluations did than women. In contrast, in female-dominated departments men tended to receive higher evaluations than did women in lower-level courses, and in upper-level courses women received higher evaluations than did men. There were no such differences at the mean department gender composition. Error bars indicate ±2 SEs.

We probed the three-way interaction two ways. First, we probed the data by department gender composition and course level, which positioned us to make direct comparisons between men and women. When considering upper-level courses in departments with gender disparities (±1 SD in percentage of men) men and women in the gender majority were evaluated more positively than men and women in the gender minority. These effects appeared to be symmetrical for both men and women. The slopes difference tests indicated that in departments with gender disparities the patterns of results for upper and lower-level courses were significantly different. In lower-level courses, men and women in the gender minority tended to be evaluated more positively than men and women in the gender majority, although not significantly so. None of these patterns were apparent in departments that were closer to gender parity. Second, we probed the data by department gender composition and educator’s gender, which positioned us to make direct comparisons between upper and lower-level courses. As mentioned previously the main effect of course level was apparent. In most cases including when departments were near gender parity, educators received higher evaluation scores for teaching upper- than lower-level courses. The only exception to this pattern was when those in the gender minority taught upper-level courses. When men and women were in the gender minority in departments with gender disparities, they did not receive higher evaluation scores for upper- than lower-level courses.

Given the context that the majority (72.3%) of courses taught were upper-level courses and women were more frequently in the gender minority (72.6% of the departments were male dominated), it became clear that although we found biases against both men and women that these biases were disproportionately impacting women’s teaching evaluations. See Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

In study 1, (N = 4,700), because the majority of women held gender-minority status (72.6% of departments were male dominated), and most classes taught were upper-level courses (72.3%) the potentially negative impact of gender bias was greater for women than for men. An estimated 32% of men and 52% of women at this university were potentially negatively impacted by gender bias in their teaching evaluations.

Discussion Study 1.

In study 1, we found support for the idea that department gender composition relates to gender bias in teaching evaluations. In departments with gender disparities students generally evaluated their educators consistent with department gender majority and minority roles. We found a statistically significant interaction between department gender composition, educator gender, and course level. Slope difference tests revealed that gender and course level interacted in departments with greater gender disparities but not in departments nearer to parity. In departments with gender disparities, those in the gender majority were evaluated more positively than those in the gender minority when teaching upper-level courses. In contrast, those in the gender minority tended to be evaluated more positively than those in the gender majority when they taught lower-level courses, although not significantly so. These patterns were not evident in departments nearer to gender parity.

Study 2

In study 2, we sought to provide causal evidence of the dynamics observed in study 1 in an experimental paradigm. After assigning students randomly to picture themselves in departments with a majority of men, parity, or a majority of women, we captured students’ expectations of their educator’s gender while varying the level of the course being taught. If it was possible to shift expectations of which gender would teach lower versus upper-level courses by assigning students randomly to departments with differing gender compositions, and we could show that meeting or violating those expectations created biases in teaching evaluations, then we would be providing a direct causal link between department gender composition and the biases that we found in study 1. Our aim was not to perfectly parallel the findings from our archival work, but rather to provide proof of concept that department composition could shift gender role expectations. And violating those expectations could change how men and women were evaluated.

In study 2, we assigned students randomly to departments with differing gender compositions. It is possible that students inferred a field of study for their randomly assigned department, but we intentionally left each department’s field of study ambiguous. We could have assigned students, for example, to a predominantly female “nursing” department or a predominantly male “engineering” department to increase the strength of the manipulation. However, that manipulation would not have endeavored to isolate the impact of department gender composition. Additionally, it would have tied us to the idiosyncrasies of particular fields such as nursing or engineering. We purposefully manipulated only the percentage of men and women in each department to highlight how gender composition affects the assumptions that students make about who belongs in essential and supportive positions. Crucially, if we wanted to inform intervention efforts that aim to balance department gender compositions, we needed to understand if intentional changes in gender composition could reduce gender bias in students’ teaching evaluations. Demonstrating this dynamic, we thought, could help efforts to reach gender parity in academia.

Laboratory experiments provide rigorous control, but they lack realism. We would expect results from our experimental investigation to differ from our archival study for two reasons. For one, students in real-life departments are powerfully informed of gendered roles simply by virtue of their activities within the department (25). The effects of our short experimental manipulation cannot be of the same strength as living in a real-world scenario (13). The second reason why we would expect results to differ between studies 1 and 2 is that in study 1, students were inured not only to their departments’ gender composition but also to their field of study (16). In study 2, gender composition was manipulated, but the field of study was unspecified. Research in role congruity theory shows us that when a work domain is left unspecified, the influence of broader gender stereotypes can be stronger (37, 39). Therefore, we might expect gender stereotypes to have more influence in study 2 than study 1.

To describe how gender stereotypes might influence evaluations, we return to the factor of course level. Even though at some well-resourced universities lower-level courses are considered high status, taught by department “stars,” generally in US universities lower-level courses are seen as lower status classes that students must get through to be able to take what they see as more important courses in their major (31). Additionally, students consider supportive relationships with their educators as more important in lower than upper-level courses (48). Therefore, because lower-level courses are considered lower status, requiring more interpersonal support, broader gender stereotypes would imply that women should teach lower-level courses. In contrast, because upper-level courses signal high status and require expertise (31), broader gender stereotypes would imply that men should teach upper-level courses.

In a male-dominated department condition wherein our manipulation of department composition and broader gender stereotypes would provide consistent cues, we anticipated that students would view lower-level courses to be lower status, taught by supportive women and upper-level courses to be high status, taught by expert men. We further predicted that women would be evaluated more highly for lower-level courses than men, and men evaluated more highly for upper-level courses than women. We expected the parity department condition to be an attenuated version of male-dominated department condition because although department gender composition would not cue gender roles, gender stereotypes still would be in play. As such women still could be seen as communal and men as agentic aligning them for lower and upper-level roles, respectively. In the female-dominated condition wherein department composition and gender stereotypes would be in contrast, we expected no gender differences because the influence of one effect could potentially cancel out the other.

We experimentally manipulated department gender composition through the ratio of men to women presented in an academic department’s webpages. We asked students to look over the academic department webpages and to imagine being students within that department. We next captured students’ expectations about whether a man or a woman would teach upper and lower-level courses in the department. Then students read about a course that they were to envision having taken (random assignment to upper or lower-level), and they read a short bio and viewed a photograph of their educator (random assignment to a woman or a man). Students then were asked to provide course evaluations on the same 11-item questionnaire used in the real-world evaluations. Our predictions for study 2 were as follows. (H1) We predicted that we would be able to change students’ expectations of whether a man or woman should teach a course based upon the course level and their random assignment to a male-dominated, parity, or female-dominated department condition. (H2) We predicted that evaluations would show biases that mirror students’ expectations. In a direct test of how students’ gendered expectations for an educator could affect course evaluations, (H3) we predicted that educators who met their students’ gendered expectations would be evaluated more positively than those who violated them.

Results Study 2.

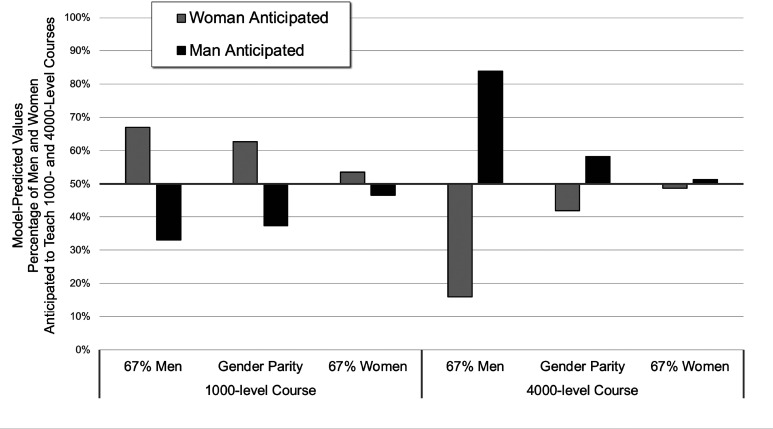

Consistent with H1, we were able to shift students’ expectations about whether a man or a woman would teach a course by their random assignment to departments of differing gender ratios. Please see the SI Appendix for model specifications. There was a significant interaction between a department’s gender composition and course-level, b = 0.054, SE = 0.027, Wald χ2 = 4.03, P = 0.045. It appeared that department gender composition and broad gender stereotypes combined to produce changes in students’ expectations. In the male-dominated department condition wherein department composition and gender stereotypes were aligned, men were more so expected to teach upper-level and women more so lower-level courses, b = 0.372, SE = 0.13, Wald χ2 = 8.72, P = 0.003. These biases were attenuated and not significant in the parity department condition where there were no cues as to department-specific gender roles but there were still gender stereotypes at play, b = 0.144, SE = 0.13, Wald χ2 = 1.23, P = 0.268. In the female-dominated department condition where department composition roles and gender stereotypes competed, we saw no bias to expect a man or a woman to teach a lower or upper-level courses, b = 0.053, SE = 0.12, Wald χ2 = 0.21, P = 0.650. See Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

From study 2 (N = 803), illustrated are the percentages of women and men that students expected to teach upper- and lower-level courses from our model estimates. Percentages are the predicted values from the statistical model that tested students’ expectations. Students guessed which of two professors (one male and one female) would teach four courses presented in random order. Students in the male-dominated, gender parity, and female-dominated departments had different expectations about whether a man or a woman should teach upper and lower-level courses.

We also found partial support for H2, that is that teaching evaluations would mirror students’ gendered expectations. When we tested student evaluations, there was an interaction between department composition, course level, and gender of educator, F(2, 8,039.02) = 12.07, P < 0.001, b = .329, SE = .079, effect size η2 = 0.328. We decomposed the three-way interaction by looking at the two-way interactions in each department condition. In the male-dominated department condition, there was a significant two-way interaction between gender and course-level, b = 0.254, SE = 0.056, t = 4.57, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.145, 0.363. Women received higher evaluations than did men for the 1,000-level course, and the inverse was true when considering the 4,000-level course. In the gender parity department condition, there was a significant two-way interaction between gender and course-level, b = 0.230, SE = 0.057, t = 4.06, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.119, 0.342. Men were evaluated more poorly than were women for the 1,000-level course. Men and women were not evaluated differently for the 4,000-level course. In the female-dominated department condition the two-way interaction between gender and course-level did not reach significance, b = −0.084, SE = 0.054, t = −1.55, P = 0.122, 95% CI −0.191, 0.022. When students imagined taking a 1,000-level course in a department dominated by women, we saw a complete reversal from the other two conditions, i.e., men were evaluated more positively than were women. Men and women were not evaluated differently for the 4,000-level course in the female-dominated condition. See Table 2 and Fig. 4.

Table 2.

Detailed results from the three-way interaction in study 2: Experimental study

| Condition | Course-level | Women | Men | P value | 95% CI of the difference | ||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct contrasts between men and women | Male-dominated | Upper | 3.747 | 0.026 | 3.840 | 0.029 | 0.018 | −0.170 | −0.016 |

| Lower | 3.924 | 0.029 | 3.764 | 0.027 | 0.000 | 0.083 | 0.238 | ||

| Parity | Upper | 3.868 | 0.028 | 3.889 | 0.027 | 0.593 | −0.097 | 0.055 | |

| Lower | 3.975 | 0.028 | 3.755 | 0.028 | 0.000 | 0.142 | 0.297 | ||

| Female-dominated | Upper | 3.835 | 0.030 | 3.835 | 0.027 | 0.990 | −0.079 | 0.078 | |

| Lower | 3.823 | 0.027 | 3.912 | 0.028 | 0.022 | −0.165 | −0.013 | ||

| Condition | Gender | Upper-level | Lower-level | P value | 95% CI of the difference | ||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Lower | Upper | ||||

| Direct contrasts between upper and lower-level courses | Male-dominated | Women | 3.747 | 0.026 | 3.924 | 0.029 | <0.001 | −0.253 | −0.100 |

| Men | 3.764 | 0.027 | 3.840 | 0.029 | 0.055 | −0.002 | 0.154 | ||

| Parity | Women | 3.868 | 0.028 | 3.975 | 0.028 | 0.007 | −0.184 | −0.030 | |

| Men | 3.889 | 0.027 | 3.755 | 0.028 | 0.001 | 0.057 | 0.210 | ||

| Female-dominated | Women | 3.835 | 0.030 | 3.823 | 0.027 | 0.766 | −0.067 | 0.090 | |

| Men | 3.835 | 0.027 | 3.912 | 0.028 | 0.049 | −0.153 | −0.000 | ||

Fig. 4.

Illustrated are the findings from study 2 (N = 803) in which random assignment to different department gender compositions and course levels significantly predicted different evaluation scores for men and women. Error bars indicate ±2 SEs.

We collected students’ expectations of educators’ genders in upper and lower-level courses to directly test how meeting or violating expectations about gender could influence students’ subsequent evaluations. Therefore, we predicted evaluation scores with expectation (1 = met, 0 = violated), the educator’s gender, and the level of the course entered as fixed factors with main effects and all possible interactions. There was a main effect of expectation, F(1, 8,041.29) = 4.20, P = 0.041, 95% CI 0.001, 0.064. When the educator’s gender met students’ expectations (M = 3.862, SE = 0.011), the educator was evaluated more positively than when they did not meet expectations (M = 3.829, SE = 0.012). Moreover, there was a significant interaction between expectations, educator gender, and course level, F(1, 8,055.43) = 10.00, P = 0.002, b = .203, SE = .064, effect size η2 = 0.210. When an educator’s gender met students’ expectations, gender and course level did not interact, P = 0.347. In sharp contrast, when gender expectations were violated, there was a robust interaction between gender and course level, F(1, 3931.31) = 27.53, P < 0.001, b = .242b SE = .046. Women’s evaluation scores (M = 3.742, SE = 0.023) dropped relative to men’s (M = 3.861, SE = 0.023) when they were evaluated for upper-level courses in which they were unexpected, P < 0.001, 95% CI 0.054, 0.183. In contrast, men’s evaluations (M = 3.792, SE = 0.023) dropped relative to women’s (M = 3.916, SE = 0.023) when they were evaluated for lower-level courses in which they were unexpected, P < 0.001, 95% CI −0.187, −0.060.

Discussion Study 2.

In study 2, we provided causal evidence that might explain the dynamics observed in study 1. We showed it was possible to shift which gender students expected to teach lower versus upper-level courses by randomly assigning students to departments with differing gender compositions. We also showed that violating those expectations created biases in teaching evaluations. We provided a possible direct link between department gender composition and the biases that we found in study 1. In the male-dominated condition, wherein our manipulation was consistent with gender stereotypes, we saw clear biases that women were expected to teach lower-level courses and men upper-level courses. Evaluations followed those same patterns.

When we looked at shifts in students’ gendered expectations, those patterns attenuated in a stepwise fashion from the male-dominated to the parity and female-dominated conditions, respectively. The evaluations did not follow such a tidy pattern in the parity and female-dominated conditions. In the parity condition, evaluations were consistent with expectations in respect to upper-level courses, in that there was a nonsignificant bias that favored men to teach and receive higher evaluations. However, in lower-level courses there was no significant expectation that women would teach lower-level courses, but women did receive significantly higher evaluations than did men for doing so. In the female-dominated condition as predicted, the expectation data did not show significant biases. The evaluations for upper-level courses were consistent with the expectation data in showing no biases. However, much like in the real-world data men received significantly higher evaluations for teaching lower-level courses than did women. Future research might investigate these findings with stronger manipulations and perhaps with additional course content to resemble real world experiences more closely.* For our purposes it was important to show that it was possible to change expectations and evaluations by changing department gender compositions. We were able to successfully do so in this experiment.

We also tested the direct consequences for men and women of meeting or violating students’ gendered expectations. When expectations were met, we did not see any biases in teaching evaluations. However, when expectations were violated, we saw strong biases that were consistent with broader gender stereotypes. That is women were penalized for filling the essential expert roles of teaching upper-level courses, and men were penalized for filling the interpersonal supportive roles of teaching lower-level courses.

General Discussion

In the archival study, we found strong support for the idea of department gender composition as a driver of bias. Students generally evaluated their educators consistent with department gender majority and minority roles. In departments with gender disparities interactions between educator gender and course level were statistically significant. Yet, we found no such effects in departments nearer to gender parity. In departments with gender disparities, those in the gender majority were evaluated more positively than those in the gender minority when they taught upper-level courses. In contrast, those in the gender minority tended to be evaluated more positively than those in the gender majority when they taught lower-level courses, although not significantly so. We found symmetrical impacts on both men and women’s evaluations. However, male-dominated departments were nearly three times more common than female-dominated departments at this university. In addition, upper-level courses were nearly three times more common than lower-level courses. Therefore, these biases disproportionately impacted women.

Gender differences in teaching evaluation scores did not reach statistical significance for lower-level courses in the archival study. It could be that there are no differences between men and women in real-world lower-level courses. However, the evidence suggests that there could be, for three reasons. For one, gender differences in evaluation scores for lower-level courses were apparent in the experimental study. Second, the direction of the results for lower-level courses in study 1 and study 2 were consistent with each other and with the theoretical framework; and third, in the archival study there were far fewer lower-level courses than upper-level courses, which meant higher statistical power when testing the upper-level courses. A limitation to this work is that a larger sample of lower-level courses may be needed to see statistically significant gender differences in evaluation scores. An additional limitation to this work is that it was conducted in a single southern US state university. Previous meta-analyses that looked at gender roles across workplaces with varying gender compositions (22, 23) do not share this limitation and the findings from our archival study were consistent with that previous research. Yet, future research should confirm these effects in other universities situated within different sociocultural climates. Students with relatively more liberal backgrounds might show different patterns in their evaluations. Thus, more empirical research on this topic is justified.

Our experimental study provided causal evidence that expectations could be shaped by department gender composition. The differences between the archival and experimental studies might be explained by the fact that gendered roles established by real-world department composition are powerful when students are in those environments daily. Likewise, departments in the archival study were situated within fields of study and departments in the experimental investigation did not specify a field of study. Our manipulation via a few moments with a faculty web page was most likely not powerful enough to override broader gender stereotypes, particularly because fields of study were not specified. Thus, the gender stereotypes appeared to play a larger part in shaping biases in the experimental than the archival study. Nonetheless, it should not be minimized that the effects of department composition were still evident even with our brief manipulation. Most importantly, regardless of whether department composition or gender stereotypes shaped expectations, we found that violating gendered expectations had a detrimental effect on the person who was evaluated. The consistency in our findings with previous research shows that department gender composition could be key in shaping gendered expectations, which in turn impact evaluations of the department’s members.

These findings taken together with the body of work on role congruity theory provide a foundation for equity and inclusion efforts. In addition to combating the effects of bias, this research suggests that we can combat some sources of bias by moving departments toward gender parity. It appears that an effective intervention could be to recruit and retain underrepresented faculty. To understand if this work could be relevant we have to ask, what impact could possibly be achieved if gender compositions could be changed within departments at a university? If a field is seen as inherently communal or agentic could broader gender stereotypes stubbornly sabotage diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts by remaining static and thereby pinning women and men into roles perceived to be communal and agentic? We have some evidence that the answer is no. As we reach gender parity across different domains, stereotypes have changed with sex differences eroding (26, 33, 49, 50). Likewise, we have historical evidence that changes in the gender composition of an occupation can override what would seem immoveable gendered characteristics of a job. Take for instance that in the 1960s, computer programmers were primarily women. In addition, during that time, the job was viewed as a supportive role. Once the field became male-dominated, the characterization of the field changed to one of cerebral analytics (51). It seems as though reaching gender parity is a way through which the cycle of gender bias can be reduced (52).

Until parity is achieved, departments might employ a strategy of “fake it until you make it” by emphasizing the presence and achievements of both men and women within their departments. Indeed, our quick manipulation showed that even a department’s webpages could have a significant effect on how faculty are evaluated. Additionally, both male and female educators should teach lower and upper-level courses to help neutralize gender expectations by way of course levels.

Those on tenure and promotion committees should be aware of these biases within teaching evaluations. However, they also should be aware of the tendency to evaluate faculty more generally based upon a sense of whether or not they “fit.” Previous findings taken from the business world (22, 23) suggest that gender biases affect job performance evaluations provided by human resources professionals and supervisors. Thus, this is not a problem specific to students or teaching evaluations. In departments with high gender disparities, promotion and hiring committees should be trained (53) to understand how their department’s gender composition may have influenced student evaluations so that they might make proper adjustments. These biases also can be addressed at the university level, with policies that require evidence other than semester-end teaching evaluations. University interventions could include the provision of bias-corrected scores that account for these systematic differences for tenure and promotion committees. University-wide training for department leaders that oversee the promotion of men and women could also ameliorate these effects.

Our findings show that the violation of gendered expectations affects evaluations. Given the gender disparities among faculty, female professors were more frequently in the position to violate students’ expectations. Consequently, our demonstrated effects disproportionately impacted women. Our additional audit into this university’s promotion guidelines suggested that these biases most likely disproportionately impacted women’s career trajectories. Men and women with lower evaluation scores could be denied promotion, and/or these educators could expend extra efforts in teaching to be on par with others who do not face these biases. Either scenario is unfair. Women in particular are underrepresented in upper levels of academia in part potentially because of the gender biases demonstrated in this article. We hope that this article aids diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts by arming them with causal evidence with which to advocate for interventions.

Materials and Methods Study 1: Archival.

Methods for study 1 were reviewed and approved by Clemson University Institutional Review Board. Our sample (N = 1,885) included tenure track and nontenure track faculty and educators. Graduate students and teaching assistants were not included. Overall, women made up 40.0% of the faculty, which was similar to national averages at R1 institutions 42.3% (1). Women were significantly more likely than men to be evaluated for lower-level courses (49.5% female educators) than upper-level courses (38.3% female educators), χ2 = 47.89, df = 1, P < 0.0001. This overrepresentation of women in lower-level courses has been noted in other studies that looked at university-wide evaluations (12, 31). Courses (N = 4,700, courses with two or more students) had been taught in the fall of 2018 and spring of 2019. Evaluation scores were the class-averaged scores for each item of an 11-item instrument. Previous researchers have found that male and female students evaluate their educators differently (11). Our course-aggregated data did not allow us to test the effects of student gender in study 1. We address this concern in study 2. Please see SI Appendix for details.

We coded each department by gender composition rather than by department type (e.g., accounting or biology) so that we might directly test the relationship between a department’s gender composition and teaching evaluations. For example, one might imagine that the “Philosophy and Religion” and the “Environmental Engineering and Earth Sciences” departments represent very different fields. Yet in this sample both departments had 74% male and 26% female educators. Therefore, if we saw that these two departments produced similar results, we could be more confident that it was the gender composition and not some other aspect about those departments that drove our results.

We contrast coded the level of the evaluated courses to reflect a center point in between the 2,000 and 3,000 levels (1,000 = −3, 2,000 = −1, 3,000 = 1, 4,000 and higher = 3). The majority (74.9%) of the evaluations in our sample were from 1,000 to 4,000 level courses. We decided to include the graduate courses (25.1% of evaluations were 5,000 and higher) in the highest level of the coding scheme a “3” for four reasons. First, coding the graduate courses separately (e.g., as a 5) rendered nearly identical results. Second, undergraduates also take graduate level courses, and we did not know which evaluations might have been provided by undergraduate students in these graduate courses. Third, we had no reason to believe that biases would be limited to undergraduate students, and fourth, including graduate level courses avoided excessive exclusions. Therefore, we included course levels 5,000 through 9,000 as a 3 in our coding.

Our preliminary analyses found that three course characteristics, student response rates (b = 0.054, SE = 0.016, t = 3.41, df = 4,228.58, P < 0.001), the number of students in a course (b = −0.092, SE = 0.014, t = −6.37, df = 3,391.84, P < 0.001), and whether or not the course was a requirement (b = −0.011, SE = 0.015, df = 3,994.88, t = −2.87, P = 0.004) were related to evaluation scores. None of the course characteristics interacted with gender of educator, all P’s > 0.43. All our statistical models controlled for these course characteristics. Results are significant and in the same direction with and without these covariates.

To test the relationships between educator’s gender, department composition, and course level, we predicted evaluation scores with a mixed linear model, which accommodated the lowest (1 course) to the highest (12 courses) number of courses for which a single educator was evaluated. Our model had three levels. First, we had evaluation scores for two semesters, and most educators had more than one teaching evaluation in our data. Therefore, we specified repeated effects that accounted for the semester in which each evaluation was collected and the nonindependence of the evaluation scores when any individual professor taught more than one course. Second, we accounted for the fact that educators were situated within departments with a random effect for department, and third, we accounted for the fact that departments were situated within colleges with a random effect for college (college was nested within department). We entered the three covariates of response rates, class size, and course requirement, and we entered department gender composition (percentage of men), course level, and gender of the educator as fixed factors. We modeled our tests in steps, first with main effects followed by interactions. See SI Appendix for further details.

Materials and Methods Study 2: Experimental.

Methods and materials for study 2 were reviewed and approved by Clemson University Institutional Review Board. Participants were provided with informed consent before they began the study. Study 2 consisted of students from 33 departments at same university as study 1. Students participated for course credit (N = 803, 394 female students) in this 3 (department gender composition: 67%, 50%, or 33% men) × 2 (course level: 1,000 or 4,000 level) × 2 (gender of educator: male or female) experimental design. The computer instructions asked students to suppose that they were part of a department for which webpages had been created for them to browse. The department’s field was left intentionally vague. Students were assigned randomly to one of three conditions that manipulated department gender composition through the ratio of men to women presented on a faculty webpage and in a “Department News” section. The faculty webpage featured 18 actual college professors that were chosen and verified by an independent sample to be equivalent in attractiveness and perceived career stage. Both are factors relevant to teaching evaluations (4, 7). See Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

In study 2 (N = 803), students viewed a “Faculty” webpage, in which we manipulated the percentage of men and women to create male-dominated, parity, and female-dominated departments. The photos were not blurred in the actual stimuli.

After viewing the department webpage, but before beginning the portion of the study in which students would provide an evaluation for a specific course and educator, students provided their expectations about whether a man or a woman would teach upper and lower-level courses through playing a guessing game. In this game, we asked students to guess which of two educators within this department, one a man and the other a woman, would teach a 1,000-, 2,000-, 3,000-, and 4,000-level course (randomly counterbalanced).

Next students were to picture themselves taking either a 1,000 or 4,000-level course. All 1,000-level courses had identical descriptions and all 4,000-level courses had identical descriptions. All students saw identical information about the educator, e.g., Ph.D. from Iowa State, and hobbies include crosswords and kayaking. The only change between the gender of educator conditions was the photograph placed directly above the bio. The photograph was selected randomly from a set of 12 photographs (6 men and 6 women, pretested to be similar in career stage and attractiveness). Students provided evaluations on the same 11-item questionnaire used in the university-wide investigation.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank Amy Lawton-Rauh, Ph.D., and Melissa Welborn for their assistance in accessing the data. We thank Sa-kiera T. J. Hudson, Ph.D., Barbara Ramirez, and Rashmi Adaval, Ph.D. for their feedback on earlier drafts of the work.

Author contributions

O.R.A., E.S.P., and B.A.P. designed research; O.R.A. and B.A.P. performed research; O.R.A. analyzed data; and O.R.A., E.S.P., and B.A.P. wrote the paper.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

*We conducted a third study in which we strengthened the manipulation by increasing the percentage of men and women (from 67 to 75%) in the male and female dominated departments respectively. We also added in lecture slides with close captioned lecture content from the supposed educator. The third study was not included in this article due to a programming error which made the female dominated department condition unusable. The results from the male dominated and gender parity conditions did show similar patterns of bias as described in study 2. See the SI Appendix for more information.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Anonymized (data files SPSS) data have been deposited in OSF (osf.io/s9bgu/?view_only=e527540d6453480a8d8640e80bdf7b42) (54). Some study data are available. (The posted archival data were transformed to protect educators’ confidentiality. We binned the “percentage of men per department” variable into 10% increments to protect the identity of those educators who could be identified with more precise information about the percentage of men in their department. This transformation did not change the direction or statistical significance of our findings.)

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Colby G., Fowler C., Data Snapshot: IPEDS Data on Full Time Women Faculty and Faculty of Color (2020). American Association of University Professors.

- 2.Wagner N., Rieger M., Voorvelt K., Gender, ethnicity and teaching evaluations: Evidence from mixed teaching teams. Econ. Educ. Rev. 54, 79–94 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boring A., Gender biases in student evaluations of teaching. J. Public Econ. 145, 27–41 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen A. S., Correlations, trends and potential biases among publicly accessible web-based student evaluations of teaching: A large-scale study of RateMyProfessors.com data. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 43, 31–44 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang G., Williamson A., Course evaluation scores: Valid measures for teaching effectiveness or rewards for lenient grading? Teach. High. Educ. 27, 1–22 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiske A. P., Haslam N., Fiske S. T., Confusing one person with another: What errors reveal about the elementary forms of social relations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 60, 656–674 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McPherson M. A., Jewell R. T., Kim M., What determines student evaluation scores? A random effects analysis of undergraduate economics classes. Eastern Econ. J. 35, 37–51 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 8.McKee J. P., Sherriffs A. C., The differential evalutaion of males and females. J. Pers. 25, 356–371 (1957). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg P., Are women prejudiced against women? Transaction 5, 316–322 (1968). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan Y., et al. , Gender and cultural bias in student evaluations: Why representation matters. PLoS One 14, e0209749 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boring A., Ottoboni K., Stark P., Student evaluations of teaching (mostly) do not measure teaching effectiveness. ScienceOpen Res. (2016), 1–11. 10.14293/S2199-1006.1.SOR-EDU.AETBZC.v1 [DOI]

- 12.Basow S. A., Student evaluations of college professors: When gender matters. J. Educ. Psychol. 87, 656–665 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sidanius J., Crane M., Job evaluation and gender: The case of university faculty. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 19, 174–197 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eagly A. H., Karau S. J., Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol. Rev. 109, 573–598 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eagly A. H., “Prejudice: Toward a more inclusive understanding” in The Social Psychology of Group Identity and Social Conflict: Theory, Application, and Practice, Baron R. M., Eagly A. H., Eds. (American Psychological Association, 2004), pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall J. A., Carter J. D., Gender-stereotype accuracy as an individual difference. Pers. Process. Individ. Differ. 77, 350–359 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cejka M. A., Eagly A. H., Gender-stereotypic images of occupations correspond to the sex segregation of employment. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 25, 413–423 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glick P., Wilk K., Perreault M., Images of occupations: Components of gender and status in occupational stereotypes. Sex Roles 32, 565–582 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banchefsky S., Westfall J., Park B., Judd C. M., But you don’t look like a scientist! Women scientists with feminine appearance are deemed less likely to be scientists. Sex Roles 75, 95–109 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eaton A. A., Saunders J. F., Jacobson R. K., West K., How gender and race stereotypes impact the advancement of scholars in STEM: Professors’ biased evaluations of physics and biology post-doctoral candidates. Sex Roles 82, 127–141 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss-Racusin C. A., Dovidio J. F., Brescoll V. L., Graham M. J., Handelsman J., Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16474–16479 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eagly A. H., Karau S. J., Makhijani M. G., Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 117, 125–145 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martiniko M. J., Gardner W. L., A methodological review of sex-related access discrimination problems. Sex Roles 9, 825–839 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Croft A., Schmader T., Block K., An underexamined inequality: Cultural and psychological barriers to men’s engagement with communal roles. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 19, 343–70 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degner J., Mangels J., Zander L., Visualizing gendered representations of male and female teachers using a reverse correlation paradigm. Soc. Psychol. 50, 233–251 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller D. I., Eagly A. H., Linn M. C., Women’s representation in science predicts national gender-science stereotypes: Evidence from 66 nations. J. Educ. Psychol. 107, 631–644 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abel M. H., Meltzer A. L., Student ratings of a male and female professors’ lecture on sex discrimination in the workforce. Sex Roles 57, 173–180 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacNell L., Driscoll A., Hunt A. N., What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innov. High. Educ. 40, 291–303 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cikara M., Martinez J. E., Lewis N. A., Moving beyond social categories by incorporating context in social psychological theory. Nat. Rev. Psychol. (2022), 1(9), 537–539. 10.1038/s44159-022-00079-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Automotive service technicians and mechanics. (2022, December 24). Publisher DataUSA. Retrieved from https://datausa.io/profile/soc/automotive-service-technicians-mechanics#sex

- 31.Johnson M. D., Narayanan A., Sawaya W. J., Effects of course and instructor characteristics on student evaluation of teaching across a college of engineering. J. Eng. Educ. 102, 289–318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vial A. C., Napier J. L., Brescoll V. L., A bed of thorns: Female leaders and the self-reinforcing cycle of illegitimacy. Leadersh. Q. 27, 400–414 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eagly A. H., Nater C., Miller D. I., Kaufmann M., Sczesny S., Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. Am. Psychol. 75, 301–315 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abele A. E., Wojciszke B., “Communal and agentic content in social cognition” in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, (Elsevier, 2014), pp. 195–255. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koenig A. M., Eagly A. H., Mitchell A. A., Ristikari T., Are leader stereotypes masculine? A meta-analysis of three research paradigms. Psychol. Bull. 137, 616–642 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelland J., Lewis D., Fisher V., Viewed with suspicion, considered idle and mocked-working caregiving fathers and fatherhood forfeits. Gend. Work Organ. 29, 1578–1593 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bosak J., Sczesny S., Eagly A. H., The impact of social roles on trait judgments: A critical reexamination. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 38, 429–440 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gustafsson Sendén M., Eagly A., Sczesny S., Of caring nurses and assertive police officers: Social role information overrides gender stereotypes in linguistic behavior. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 11, 743–751 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eagly A. H., Steffen V. J., Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 46, 735–754 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Syrda J., Spousal relative income and male psychological distress. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46, 976–992 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S. J., Lee J. Y., Chang O. D., in “The characteristics and lived experiences of modern stay-at-home fathers” in Handbook of Fathers and Child Development: Prenatal to Preschool, Fitzgerald H. E., von Klitzing K., Cabrera N. J., Scarano de Mendonça J., Skjøthaug T., Eds. (Springer International Publishing, 2020), 10.1007/978-3-030-51027-5 (November 11, 2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petts R. J., Kaufman G., Mize T. D., Parental leave-taking and perceptions of workers as good parents. J. Marriage Fam. (2022), 10.1111/jomf.12875. [DOI]

- 43.Meeussen L., Koudenburg N., A compliment’s cost: How positive responses to non-traditional choices may paradoxically reinforce traditional gender norms. British J. Soc. Psychol. 61, 1183–1201 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Registered nurses. (2022, December 24). Publisher DataUSA. Retrieved from https://datausa.io/profile/soc/registered-nurses#sex

- 45.Fritz C. O., Morris P. E., Richler J. J., Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. General 141, 2–18 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dawson J. F., Richter A. W., Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. J. Appl. Psychol. 91, 917–26 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Robinson C. D., Tomek S., Schumacker R. E., Test of moderation effects: Difference in simple slopes versus the interaction term. Mult. Linear Regression Viewp. 39, 16–24 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey C. D., Gupta S., Schrader R. W., Do students’ judgment models of instructor effectiveness differ by course level, course content, or individual instructor? J. Accounting Educ. 18, 15–34 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Diekman A. B., Eagly A. H., Stereotypes as dynamic constructs: Women and men of the past, present, and future. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 26, 1171–1188 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller D. I., Nolla K. M., Eagly A. H., Uttal D. H., The development of children’s gender-science stereotypes: A meta-analysis of 5 decades of U.S. draw-a-scientist studies. Child Dev. 89, 1943–1955 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheryan S., Master A., Meltzoff A. N., Cultural stereotypes as gatekeepers: Increasing girlsâ€TM interest in computer science and engineering by diversifying stereotypes. Front. Psychol. 6, 49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Eagly A. H., Koenig A. M., The vicious cycle linking stereotypes and social roles. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 30, 343–350 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moss-Racusin C. A., Pietri E. S., van der Toorn J., Ashburn-Nardo L., Boosting the sustainable representation of women in STEM with evidence-based policy initiatives. Policy Insights Behav. and Brain Sci. 8, 50–58 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aragón, O. R. Data for Gender Bias in Teaching Evaluations. OSF Storage. osf.io/s9bgu/?view_only=e527540d6453480a8d8640e80bdf7b42 Deposited September 20, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized (data files SPSS) data have been deposited in OSF (osf.io/s9bgu/?view_only=e527540d6453480a8d8640e80bdf7b42) (54). Some study data are available. (The posted archival data were transformed to protect educators’ confidentiality. We binned the “percentage of men per department” variable into 10% increments to protect the identity of those educators who could be identified with more precise information about the percentage of men in their department. This transformation did not change the direction or statistical significance of our findings.)