Abstract

Using an electronic health record–based algorithm, we identified children with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) based exclusively on serologic testing between March 2020 and April 2022. Compared with the 131 537 polymerase chain reaction–positive children, the 2714 serology-positive children were more likely to be inpatients (24% vs 2%), to have a chronic condition (37% vs 24%), and to have a diagnosis of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (23% vs <1%). Identification of children who could have been asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic and not tested is critical to define the burden of post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection in children.

Keywords: PEDSnet, COVID-19 serology, anti-N antibodies, anti-S antibodies, post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, long COVID, chronic COVID-19 syndrome, late sequelae of COVID-19, long-haul COVID-19, long-term COVID-19, post–COVID-19 syndrome, post-acute COVID-19, post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection

Since the beginning of the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, different testing modalities for diagnosis have been implemented.1 Although molecular tests remain the more reliable and accurate modality for diagnosing acute severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, serologic testing has some key advantages. In the absence of a prior positive molecular test, serology aids the diagnosis of conditions that occur after SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)2 and post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), defined as ongoing, relapsing, or new symptoms or other health effects occurring ≥4 weeks after acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.3 In addition, serologic testing has public health value and is used for epidemiologic purposes to assess the burden of prior SARS-CoV-2 infections in the population. However, the interpretation of antibody testing has been challenging for many reasons. First, assays use different technologies and measure different classes of immunoglobulins. Second, these assays are directed toward different SARS-CoV-2 proteins, such as the nucleocapsid (N) and spike (S) proteins. Whereas IgG anti-N antibodies reflect past infection irrespective of vaccination, the vaccines approved in pediatric populations induce the production of IgG anti-S antibodies. Thus, detection of anti-S antibodies does not distinguish between prior vaccination and prior infection.

We conducted a retrospective study as part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery Initiative (RECOVER; https://recovercovid.org/), which seeks to understand, treat, and prevent PASC in children and adults. Leveraging PEDSnet, a multi-institutional clinical research network that analyzes EHR data from several of the nation’s largest children’s healthcare organizations, we sought to develop an accurate and reliable EHR-based algorithm to identify children and adolescents aged <21 years who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection exclusively by serology during the pandemic.4 In addition, we contrasted the serology-positive cohort with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive cohort to identify differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. Identification of children who could have been asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic (ie, presenting with few symptoms) and not tested or missed early in the pandemic is of critical importance for defining the prevalence and burden of PASC in children.

Methods

Data Source

Electronic health record (EHR) data were retrieved from all health care encounters at PEDSnet (pedsnet.org) institutions associated with children and adolescents who underwent serology and/or SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing in outpatient, inpatient, and emergency department settings. The institutions participating in the study were Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Children’s Hospital Colorado, Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Nemours Children’s Health System (a Delaware and Florida health system), Seattle Children’s Hospital, and Stanford Children’s Health.5 Institutional source data were standardized to the PEDSnet common data model, described in detail elsewhere.6 CHOP’s Institutional Review Board designated this study as not human subjects research and waived informed consent.

Cohort Formation

To define the serology-positive cohort, we first examined the frequency and type of serologic testing performed at PEDSnet institutions for children and adolescents aged <21 years at the time of the health encounter, between March 1, 2020, and April 20, 2022. The serologic tests included IgM and IgG anti-N antibodies, IgG anti-S or receptor binding domain (RBD) antibodies, and IgG and IgA undifferentiated antibodies. We then identified children who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 by serology only and did not have a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. EHR documentation of COVID-19 vaccination has not been fully linked and harmonized with other EHR data within our network; thus, to ensure that serologic tests results were related to a past SARS-CoV-2 infection rather than to vaccination, we applied the timing of age-specific vaccine approvals by the US Food and Drug Administration and excluded children with positive IgG anti-S/RBD, IgA, or undifferentiated IgG tests after the vaccination-eligible periods. We used the following vaccine approval dates: December 12, 2020: BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNtech) in children aged >16 years; May 12, 2021: BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNtech) for children aged 12-15 years, and November 2, 2021: BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNtech) for children aged 5-11 years. The adenovirus vaccine (Ad26.COV2.S) marketed by Janssen was approved in the US in February 28, 2021, for patients aged >18 years. However, the overall uptake of this vaccine has been low, especially in the 18- to 25-year age group; thus, serology age cutoffs for this vaccine were not included. Cohort entry for the positive serology group was defined as the date of first positive IgM, IgA, or IgG COVID-19 antibodies after applying the aforementioned filters. For the PCR-positive group, cohort entry was defined as the date of a first positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test irrespective of serology testing.4 , 7 COVID cases were defined according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines (https://services.cdc.gov/case-definitions/coronavirus-disease-2019-2021).

Statistical Analyses

We examined the numbers of serologic tests performed and percentage of positive serologic tests over time using descriptive statistics and data visualization. We used the χ2test to examine differences in demographic and clinical characteristics between the serology-positive and PCR-positive cohorts. Owing to the large sample size, we calculated effect sizes using standardized mean differences (SMDs), which reflect the difference between the group’s mean divided by the pooled SD.8 An SMD >0.2 was considered clinically meaningful.

Clinical characteristics of interest included chronic conditions, site of testing (emergency department, inpatient, outpatient), and COVID-19–related diagnoses. The Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA) version 2.0 was applied to categorize children as having no chronic conditions, noncomplex chronic conditions, or complex chronic comorbidities, considering diagnoses up to 3 years before cohort entrance as described previously.9 , 10 We examined MIS-C and COVID-19 diagnoses recorded ±30 days of the SARS-CoV-2 test. Analyses were conducted using R version 4.1.2.

Results

Serology Testing Over Time

Between March 1, 2020, and April 20, 2022, we identified 18 647 serologic tests and 1 764 658 PCR tests performed in 1 025 349 unique patients within the PEDSnet network. The same patient could have had more than one test performed in the data set. As such, we identified 348 678 patients who had multiple PCR tests performed, and 3225 patients with multiple serologic tests performed during the study period. The serologic tests most commonly used were undifferentiated IgG antibodies (7361 tests; 40%) and IgG anti-N antibodies (7326 tests; 39.3%), followed by IgM antibodies (2108 tests; 13.3%), anti-S or RBD IgG antibodies (1127 tests; 6%), and undifferentiated IgA antibodies (637 tests; 3.4%).

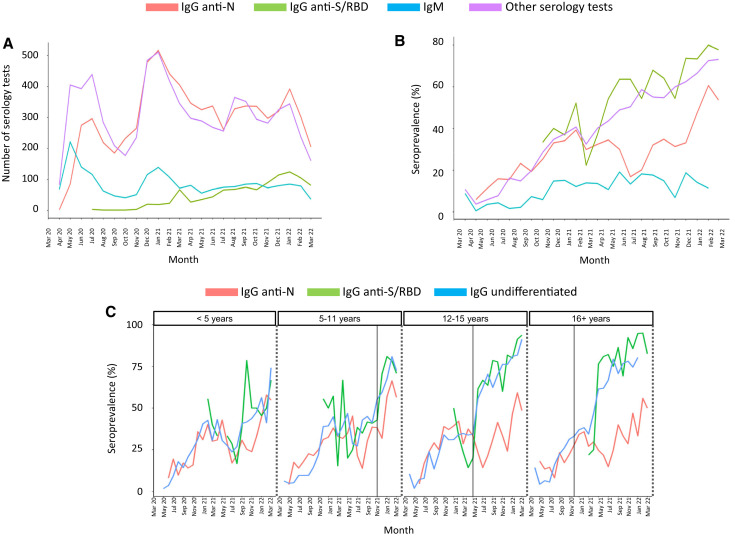

The number and types of tests performed at each participant site are included in Table I ). The use of undifferentiated IgG or IgG anti-N antibodies was relatively high throughout the study, with a peak in testing during the winter of 2020-21 (Figure 1 , A). The use of IgM was highest in the spring of 2020 and decreased over time, whereas the use of IgG anti-S/RBD antibodies increased following vaccine approval for adolescents in December 2020. The overall percentage of positive serologic tests increased over time and peaked during the omicron wave from December 2021 to February 2022 (Figure 1, B).

Table I.

Number of serology tests performed at each PEDSnet site from March 1, 2020 to April 20,2022

| Sites | IgG undifferentiated | IgG anti-N | IgM | IgG anti-S or RBD | IgA | Ab undifferentiated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3680 | 0 | 640 | 0 | 640 | 0 |

| B | 460 | 660 | 20 | 100 | <11 | 80 |

| C | <11 | 1560 | 300 | 510 | 0 | <11 |

| D | 190 | 800 | 0 | <11 | 0 | 0 |

| E | 0 | 2570 | 0 | 110 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 1530 | 490 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| G | 0 | 1240 | 0 | 250 | 0 | 0 |

| H | 1500 | 0 | 1150 | 60 | 0 | <11 |

| Total | 7361 | 7326 | 2108 | 1127 | 637 | 88 |

Site-specific counts were rounded to the nearest 10 to mask counts of <11.

Figure 1.

Number and positivity rates of SARS-CoV-2 antibody tests performed during the COVID-19 pandemic. A, Monthly number of serologic tests performed with a valid (positive or negative) result. The y-axis represents the number of tests performed by type of test over time (x-axis). Other serologic tests include undifferentiated IgG (the vast majority) and IgA tests. B, Monthly percentage of positive test results by type of test are plotted on the y-axis. IgG anti-N antibodies are depicted in red, IgM antibodies are in blue, IgG anti-S/RBD antibodies are in green and other serology tests, including undifferentiated IgG and IgA anti-SARS-CoV-2, are in purple. IgM positivity rates increased from 7% pre-alpha (March 2020 to February 2021) to 14% in the alpha phase, 15% in the delta phase, and 13% in the omicron phase (P < .001). The increase was also significant for IgG anti-N, IgG anti-S/RBD, and other serologic tests as the pandemic evolved (P < .001). C, Percentage of serologic tests with positive results by month (IgG anti-N in red, undifferentiated IgG in blue; IgG anti-S/RBD in green) according to age, stratified in 4 groups: <5 years, 5-11 years, 12-15 years, and 16-< 21 years. Vertical lines indicate the date of vaccine approval for each specific group.

Positivity rates for IgG anti-N or IgM antibodies reflected changes in SARS-CoV-2 infections, including known increases during the alpha variant phase (March-June 2021), the circulation of the delta variant (July-December 2021), and the circulation of omicron that began in December 2021 based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 data.11 Increases in the positivity rates of serologic tests able to detect anti-S antibodies were particularly pronounced in children aged 12-15 years and ≥16 years in the months following age-specific approvals for COVID-19 vaccines (Figure 1, C). A similar pattern was observed with undifferentiated IgG antibodies.

Contrast Between the Serology-Positive and PCR-Positive SARS-CoV-2 Cohorts

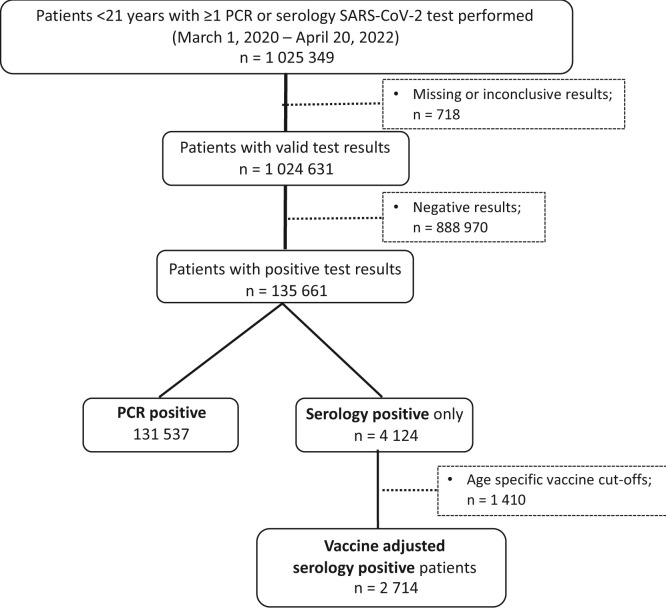

Of the 1 025 349 patients with at least 1 PCR or serologic test performed in serum or plasma specific for SARS-CoV-2, <0.1% of values were excluded because of unknown results or missing values. After excluding children and adolescents with negative test results, there were 135 661 unique patients with at least 1 positive PCR, a positive serologic test result, or positive results for both tests at any time during the study period. Thus, a child who tested negative by serology but positive by PCR remained in the PCR-positive group, and a child who tested positive by serology but negative by PCR remained in the serology-positive cohort. Among individuals with at least 1 positive test, 131 537 (97%) were identified by PCR, 4124 (3%) were identified exclusively by serology testing, and 792 were identified by both PCR and serology during the study period. The latter group were included in the PCR cohort, as they would have been identified by our PCR-based algorithms. After applying age-specific vaccine cutoffs, we identified 2714 patients who tested positive by serology and did not have a positive PCR test reported (Figure 2 ).

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of patient selection based on serology and PCR testing. Of all patients with a COVID-19 test performed, after excluding missing data and negative or inconclusive results, 135 661 patients had a positive test result (97% by PCR and 3% by serology testing exclusively). Of these, one-third were excluded after applying age-specific cutoffs for vaccine approval.

The characteristics of the 1 024 631 children and adolescents who underwent testing for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR and/or serology and the 134 251 who tested positive by at least 1 test are reported in Table II . Compared with PCR-positive patients, serology-positive children were more likely to be non-Hispanic White (55% vs 45%), and a greater proportion were in the 12-15 years age group of (23% vs 18%), largely reflecting the characteristics of those who were tested serologically Table III ). Serology-positive patients were also more likely to have a chronic condition compared with PCR-positive patients (37% vs 24%), especially a complex medical condition (27% vs 11%). Most serology-positive and PCR-positive patients were tested in the outpatient setting (52% and 76%, respectively), but a higher proportion of serology-positive patients than PCR-positive patients were tested as inpatients (24% vs 2%). Patients identified solely by serology were more frequently diagnosed with MIS-C (23% vs <1%). On the other hand, a COVID-19 diagnosis was significantly more common in the PCR-positive cohort (72% vs 45%).

Table II.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2–positive PCR and serology cohorts

| Characteristics | SARS-CoV-2 infection (N = 34 251) | SARS-CoV-2 PCR cohort (N = 131 537)∗ | SARS-CoV-2 serology cohort (N = 2714) | SMD (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at cohort entrance, y, mean (SD) | 8.7 (6.0) | 8.7 (6.0) | 9.5 (5.6) | |

| Age at cohort entrance, y, n (%) | ||||

| 0-4 | 46 722 (35) | 45 959 (35) | 763 (28) | 0.18 (<.001) |

| 5-11 | 43 109 (32) | 42 179 (32) | 930 (34) | |

| 12-15 | 23 862 (18) | 23 234 (18) | 628 (23) | |

| 16-20 | 20 558 (15) | 20 165 (15) | 393 (15) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 65 101 (48) | 63 836 (49) | 1265 (47) | 0.04 (.05) |

| Male | 69 138 (52) | 67 689 (51) | 1449 (53) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic | 25 230 (19) | 24 733 (19) | 497 (18) | 0.26 (<.001) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 60 252 (45) | 58 746 (45) | 1506 (55) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American | 25 900 (19) | 25 549 (19) | 351 (13) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander | 4534 (3) | 4452 (3) | 82 (3) | |

| Other/unknown | 12 904 (10) | 12 739 (10) | 165 (6) | |

| Multiple | 5431 (4) | 5318 (4) | 113 (4) | |

| Health institution, n (%) | ||||

| A | 29 009 (22) | 28 389 (22) | 620 (23) | 0.49 (<.001) |

| B | 28 807 (22) | 28 577 (22) | 230 (9) | |

| C | 21 645 (16) | 21 280 (16) | 365 (13) | |

| D | 6787 (5) | 6545 (5) | 242 (9) | |

| E | 23 172 (17) | 22 668 (17) | 504 (19) | |

| F | 15 308 (11) | 14 907 (11) | 401 (15) | |

| G | 3213 (2) | 2983 (2) | 230 (8) | |

| H | 6310 (5) | 6188 (5) | 122 (4) | |

| Chronic conditions, n (%) | ||||

| None | 101 899 (76) | 100 184 (76) | 1715 (63) | 0.44 (<.001) |

| Noncomplex | 17 627 (13) | 17 369 (13) | 258 (10) | |

| Complex | 14 725 (11) | 13 984 (11) | 741 (27) | |

| Period of cohort entrance, n (%) | ||||

| March 2020-June 2020 | 2999 (2) | 2944 (2) | 55 (2) | 0.44 (<.001) |

| July 2020-October 2020 | 9029 (7) | 8832 (7) | 197 (7) | |

| November 2020-February 2021 | 31 239 (23) | 30 505 (23) | 734 (27) | |

| March 2021-June 2021 | 10 526 (8) | 10 017 (8) | 509 (19) | |

| July 2021-December 15, 2021 | 30 489 (23) | 29 870 (23) | 619 (23) | |

| December 16, 2021-April 20,2022 | 49 969 (37) | 49 369 (37) | 600 (22) | |

| Test location, n (%) | ||||

| Emergency department | 28 894 (21) | 28 244 (22) | 650 (24) | 0.72 (<.001) |

| Inpatient | 3389 (3) | 2745 (2) | 644 (24) | |

| Outpatient | 101 952 (76) | 100 532 (76) | 1420 (52) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| MIS-C | 877 (1) | 253 (<1) | 624 (23) | 0.82 (<.001) |

| COVID-19 (no MIS-C) | 96 466 (72) | 95 230 (72) | 1236 (45) | |

| No COVID-19 or MIS-C | 36 908 (27) | 36 054 (28) | 854 (32) |

SMD was used to measure the effect size between the PCR and serology positive cohorts and may be interpreted as equivalent to a z-score of a standard normal distribution. An SMD >0.2 was considered clinically meaningful. The higher the SMD, the larger the effect size.

Patients included in the PCR cohort could have a serology test performed as well.

Table III.

Characteristics of children and adolescents based on COVID-19 testing

| Characteristic | Patients with PCR testing performed (N = 1 020 336)∗ | Patients with only serology testing performed (N = 4295) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at cohort entrance, y, mean (SD) | 7.9 (5.8) | 11.9 (5.4) | |

| Age at cohort entrance, y, n (%) | |||

| 0-4 | 404 422 (40) | 632 (15) | |

| 5-11 | 327 592 (32) | 1301 (30) | |

| 12-15 | 160 547 (16) | 1183 (28) | |

| 16-20 | 127 775 (12) | 1179 (27) | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 485 534 (48) | 2103 (49) | |

| Male | 534 606 (52) | 2192 (51) | |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 165 180 (16) | 464 (11) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 514 902 (51) | 2899 (68) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black/African American | 150 348 (15) | 171 (4) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander | 43 139 (4) | 232 (5) | |

| Other/unknown | 103 986 (10) | 403 (9) | |

| Multiple | 42 781 (4) | 126 (3) | |

| Health institution, n (%) | |||

| A | 177 602 (17) | 774 (18) | |

| B | 205 124 (20) | 407 (9) | |

| C | 171 967 (17) | 343 (8) | |

| D | 73 104 (7) | 245 (6) | |

| E | 155 404 (15) | 672 (16) | |

| F | 122 344 (12) | 695 (16) | |

| G | 57 139 (6) | 683 (16) | |

| H | 57 652 (6) | 476 (11) | |

| Chronic conditions, n (%) | |||

| None | 777 710 (76) | 2800 (65) | |

| Noncomplex | 127 894 (13) | 569 (13) | |

| Complex | 114 732 (11) | 926 (22) | |

| Period of cohort entrance, n (%) | |||

| March 2020-June 2020 | 72 645 (7) | 435 (10) | |

| July 2020-October 2020 | 199 793 (20) | 654 (15) | |

| November 2020-February 2021 | 204 316 (20) | 945 (22) | |

| March 2021-June 2021 | 152 517 (15) | 723 (17) | |

| July 2021-December 15, 2021 | 265 237 (26) | 989 (23) | |

| December 16, 2021-April 20, 2022 | 125 828 (12) | 549 (13) | |

| Test location, n (%) | |||

| Emergency department | 209 984 (21) | 453 (11) | |

| Inpatient | 51 291 (5) | 187 (4) | |

| Outpatient | 758 900 (74) | 3655 (85) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| MIS-C | 915 (<0.1) | 99 (2) | |

| COVID-19 (no MIS-C) | 438 607 (43) | 1295 (30) | |

| No COVID-19 or MIS-C | 580 814 (57) | 2901 (68) | |

Patients included in the PCR cohort could have a serology test performed as well. COVID-19 diagnosis data include codes associated with confirmed as well as suspected or presumptive COVID-19.

Discussion

In this study, we developed and applied an EHR-based code set to identify children with COVID-19 based on serology testing who would have been missed otherwise had cohort selection been based solely on PCR.4 We found that the frequency of serologic testing was significantly lower than that of PCR, and that there was substantial variability in both the frequency and type of serologic tests used across 8 large pediatric institutions. Through data harmonization and exclusion of results during age-based vaccine eligibility periods, we identified a subset of children who had not been identified by molecular testing in our network. These patients were frequently tested in the inpatient setting, and one-fourth had an MIS-C diagnosis, compared with <1% of the PCR-positive cohort. In addition, these children had a higher prevalence of underlying complex medical conditions compared with those identified by PCR. Accurate identification of children and adolescents with positive SARS-CoV-2 serology results is critical in studies evaluating the presentation, burden, and risk of PASC in pediatrics.

Unlike nucleic acid amplification tests that detect SARS-CoV-2 RNA, serologic assays measure the antibody response to current or past infection and to vaccines. Antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 typically are detected more than 2 weeks after symptom onset, which limit their diagnostic utility during the acute disease stage.12 On the other hand, they are useful clinically for identifying patients with post-acute manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection, such as MIS-C and/or other post-acute sequalae. This is especially relevant in children whose initial infection might not have been detected because they were asymptomatic or mildly ill, which does not preclude the development of PASC.13 Compared with the latest cumulative national estimates of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children, which are approaching 75% of the pediatric population,14 serologic testing for SARS-CoV-2 was performed in a minority of children in our network. Thus, it is clear that the number of SARS-CoV-2 infected children is significantly greater than that captured in health care systems, and the numbers identified in our study likely represent the tip of the iceberg.

In our study, the most frequently used serologic tests were undifferentiated IgG against SARS-CoV-2, followed by IgG anti-N antibodies. However, we observed that IgG anti-S antibody use increased after vaccine implementation. The Food and Drug Administration does not recommend antibody testing to evaluate the level of immunity against SARS-CoV-2 at any time and especially after vaccine administration. Whether the increased use and positivity rate of IgG anti-S antibodies reflect the performance of these tests to examine vaccine responses, or whether they represent a true increase in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infections in unvaccinated children, warrants further studies.

The diagnosis of PASC relies on a broad range of new, recurring, or persistent clinical manifestations that last 4 weeks or longer after SARS-CoV-2 infection and may be difficult to recognize in children.15 This, coupled with the underreporting and underestimation of COVID-19 in pediatrics, has limited our ability to fully define the long-term impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. Understanding the utility and implementation of serology testing in children is critical and will provide comprehensive and essential information to define the computable phenotype of PASC in children. Nevertheless, a homogeneous, robust, and reliable system for reporting SARS-CoV-2 infections is needed that would allow defining the true incidence of PASC in children, with symptoms that might be underrecognized and/or attributed to other long-standing health conditions.

Our study has some limitations. We lack the reasons that prompted caregivers to order serologic testing, which would require manual chart review. On the other hand, it is reassuring that one-fourth of the serology-positive patients had an associated MIS-C diagnosis, suggesting that these tests were ordered in an appropriate clinical context. We took a conservative approach and used vaccine approval dates to exclude children with positive serology tests that did not permit discrimination between SARS-COV-2 infection and vaccination. Thus, we have likely underestimated and not included a group of children who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. Studies that incorporate vaccination registry data will overcome this limitation. A minority of children in our network underwent serologic testing, and their results suggest that testing was biased toward sicker children. Future studies should incorporate a combination of approaches, including PCR testing, serologic testing, and diagnoses, to define the computable phenotype of PASC in children. Despite these limitations, we included a large sample size of children across 8 major pediatric health care systems in the US with variable practices, which allowed us to capture a pediatric population at risk for PASC.

Harmonization of data and development of a refined COVID-19 EHR-based serology system has enabled additional identification of children with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection beyond PCR testing alone who might be at risk for PASC. Inclusion of serologic testing will be necessary to capture relevant cohorts and will allow more accurate examination of the presentation, risk, and burden of PASC in children.

Footnotes

This research was funded by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Agreement OT2HL161847-01 as part of the Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery (RECOVER) program. The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the RECOVER Program, the NIH, or other funders.

A.M. reports funding from Janssen and Merck for research support and from Janssen, Merck, and Sanofi-Pasteur for advisory board participation. S.R. reports prior grant support from GSK and BioFire and serves as a consultant for Sequiris. R.J. serves as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Seqirus, and Dynavax and receives an editorial stipend from Elsevier. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Hanson K.E., Caliendo A.M., Arias C.A., Englund J.A., Lee M.J., Loeb M., et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciab048. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfred-Cato S., Bryant B., Leung J., Oster M.E., Conklin L., Abrams J., et al. COVID-19-associated multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children–United States, March-July 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1074–1080. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6932e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanson K.E., Caliendo A.M., Arias C.A., Englund J.A., Hayden M.K., Lee M.J., et al. Infectious diseases Society of America guidelines on the diagnosis of COVID-19:serologic testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:ciaa1343. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forrest C.B., Burrows E.K., Mejias A., Razzaghi H., Christakis D., Jhaveri R., et al. Severity of acute COVID-19 in children <18 years old March 2020 to December 2021. Pediatrics. 2022;149 doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-055765. e2021055765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forrest C.B., Margolis P., Seid M., Colletti R.B. PEDSnet: how a prototype pediatric learning health system is being expanded into a national network. Health Aff. 2014;33:1171–1177. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gotzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P., et al. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rao S., Lee G.M., Razzaghi H., Lorman V., Mejias A., Pajor N.M., et al. Clinical features and burden of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176:1000–1009. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Tov A., Lotan R., Gazit S., Chodick G., Perez G., Mizrahi-Reuveni M., et al. Dynamics in COVID-19 symptoms during different waves of the pandemic among children infected with SARS-CoV-2 in the ambulatory setting. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:3309–3318. doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04531-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simon T.D., Cawthon M.L., Stanford S., Popalisky J., Lyons D., Woodcox P., et al. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e1647–e1654. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon T.D., Cawthon M.L., Popalisky J., Mangione-Smith R. Center of excellence on quality of care measures for children with complex N. Development and Validation of the pediatric medical complexity algorithm (PMCA) version 2.0. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7:373–377. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2016-0173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Disease and Prevention COVID data tracker. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home

- 12.Drain P.K. Rapid diagnostic testing for SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:264–272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2117115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldstein L.R., Rose E.B., Horwitz S.M., Collins J.P., Newhams M.M., Son M.B.F., et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in U.S. children and adolescents. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:334–346. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clarke K.E.N., Jones J.M., Deng Y., Nycz E., Lee A., Iachan R., et al. Seroprevalence of infection-Induced SARS-CoV-2 antibodies–United States, September 2021-February 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:606–608. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7117e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Evaluating and caring for patients with post-COVID conditions: interim guidance. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.