Abstract

Background

The emerging 2022 human mpox virus outbreak has presented with unique disease manifestations challenging prior case definitions.

Case Report

We present a case of a 42-year-old transgender woman with human immunodeficiency virus controlled on antiretroviral therapy, presenting with sore throat, who, after three emergency department visits, was found to have acute tonsillitis complicated by airway obstruction secondary to mpox.

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

Sore throat is a common presentation to the emergency department. mpox should be placed on the list of differential diagnoses when evaluating patients who present with pharyngitis to avoid complications or a missed diagnosis.

Keywords: mpox, Acute tonsillitis, Peritonsillar abscess, Airway obstruction, Tecovirimat

Introduction

mpox is an Orthopoxvirus that has led to a global outbreak across several nonendemic countries. The last known U.S. outbreak of mpox was in 2003, due to the import of infected small mammals from Ghana (1). The 2022 mpox outbreak has occurred in several nonendemic countries, in patients with no travel history to endemic countries, and in those with close contact with infected persons (2). Typically, human mpox presents with a prodrome of fever, chills, headache, myalgias, and back pain, followed by a maculopapular exanthem (1). This exanthem is often uniform and centrifugally progresses through stages of macules, papules, vesicles, and then pustules (3). Prodromal symptoms remain the same; however, the 2022 mpox outbreak has resulted in isolated lesions, primarily localized to anogenital regions, particularly in people who identify as gay, bisexual, or other men who have sex with men (2).

Case Report

A 42-year-old transgender woman with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease (CD4 count = 1048 cells/μL and undetectable HIV-1 RNA viral load) controlled on antiretroviral therapy developed fever, headache, myalgias, and sore throat after a recent unprotected sexual encounter (oral, anal insertive) with a male partner. On first presentation to the emergency department (ED), she tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 via polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis nucleic acid amplification testing of the throat. She was prescribed a course of doxycycline without improvement. Two days later, she returned to the ED with persistent symptoms. She tested negative for rapid group A streptococcus screen, nasal respiratory pathogen panel, and throat culture grew normal respiratory flora. She was given dexamethasone, ketorolac, and discharged with azithromycin.

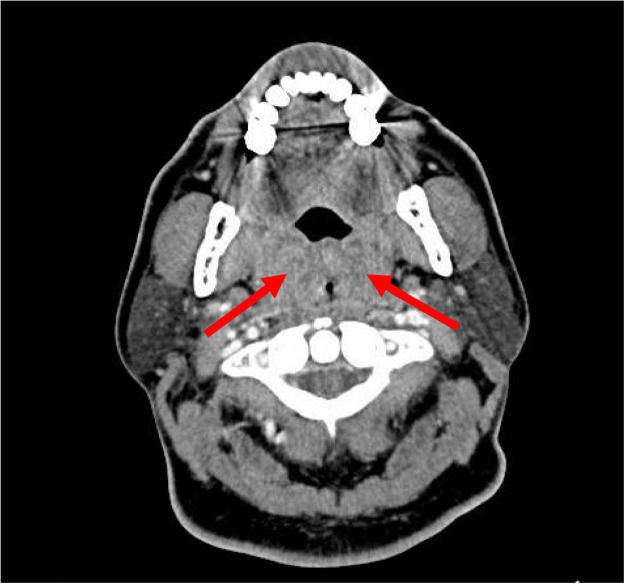

Four days after the second presentation, she returned to the ED with severe odynophagia, new dysphagia, and dysphonia. On physical examination, the patient had a temperature of 36.6°C, heart rate of 95 beats/min, blood pressure of 117/84 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. She had a muffled voice, bilateral tonsillar swelling with exudates, and tender cervical adenopathy. Her white blood cell count was 9.53 × 109 cells/L. Rapid mononucleosis testing returned negative. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck soft tissue with contrast revealed significantly enlarged bilateral tonsils with small abscesses and severe airway narrowing (Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Computed tomography of neck soft tissue with contrast. Enlargement of the left and right tonsils (arrows) and adjacent soft tissues with marked narrowing of the airway in this region. There may be small hypodensities in the tonsils potentially representing small abscesses.

She was admitted for management of airway compromise and treatment was initiated with one dose of intravenous methylprednisolone. Her pharyngeal symptoms improved rapidly after initiation of corticosteroid. The day after admission, which was 7 days after her initial ED visit for pharyngitis, discrete papules erupted on the chest, back, buttocks, knee, and thigh (Figure 2 ). Three swabs were collected, two from skin lesions and one from the tonsils. PCR assay was performed, with all tested sites resulting positive for non-variola orthopoxvirus. She was discharged with resolution of pharyngeal symptoms on the third day of admission, along with a 14-day course of tecovirimat. At the end of tecovirimat treatment, her skin lesions resolved.

Figure 2.

mpox skin lesions. Discrete nodules on an erythematous base across back on second day of admission.

Discussion

The diagnosis of mpox has been challenging for clinicians due to its nonspecific systemic symptoms and atypical presentations (4). Our patient presented with pharyngitis and subsequently developed oropharyngeal lesions and airway compromise on consecutive ED visits. The evaluating physicians appropriately considered sexually transmitted infections workup with gonorrhea and chlamydia testing, due to her sexual history and a prior diagnosis of chlamydial pharyngitis. They also appropriately assessed for other respiratory infections. However, without initial dermatologic manifestations, no emergency physician considered mpox at any of the three presentations to the ED.

Oropharyngeal symptoms were reported in approximately 5% of patients (26 of 528) as the initial presenting symptom in a large retrospective study by Thornhill et al. (5). In another observational case series, 61.5% of patients (102 of 166) reported prodromal systemic symptoms, such as fever and myalgias, prior to skin lesions (5,10). Patients are presumed to be infectious from the time of symptoms, which include prodromal symptoms prior to rash (4). Presenting with an isolated prodrome demonstrates a challenge for evaluating physicians. However, with thorough history taking, emergency physicians should have a high level of suspicion for mpox in any patient who has risk factors for acquiring mpox. Our case, with presenting symptoms of dysphagia without pathognomonic mucocutaneous lesions, highlights the importance for physicians to keep mpox high on their list of differential diagnoses.

The known severe complications of mpox include encephalitis, septicemia, bronchopneumonia, and ocular lesions resulting in corneal scarring and permanent vision loss (6). One reported case from the 2003 U.S. mpox outbreak described the development of a retropharyngeal abscess in a 10-year-old girl (7). She developed tracheal airway compromise secondary to a large retropharyngeal abscess and cervical lymphadenopathy. She was managed in the intensive care unit with prednisone and recovered.

From the 2022 outbreak, there have been several cases describing tonsillar abscesses (10,8). In the descriptive U.K. case series by Patel et al, one participant developed a right tonsillar abscess and right submandibular swelling, resulting in dysphagia and difficulty breathing (10). This patient subsequently developed a widespread maculopapular rash over the chest, back, and upper arms, with areas of confluent erythema. A single papule on the forearm was observed, which initiated investigation into mpox. Swabs taken from skin lesions and tonsillar exudate resulted positive for mpox. Similar to our case report, this patient developed the characteristic dermatologic manifestation of mpox after development of oropharyngeal symptoms.

The development of a tonsillar abscess with airway compromise is rare. This particular manifestation of mpox may have been secondary to a delayed diagnosis, exacerbated by lack of initial characteristic dermatologic lesions. In addition, HIV disease, although controlled with antiretroviral therapy in our patient, may have also contributed to a severe manifestation of tonsillitis. In the case series by Thornhill et al., HIV disease was present in 41% of cases (5). Co-infection with HIV and mpox is an ongoing area of interest and investigation. With this case report, we hope to encourage emergency physicians to consider mpox in patients who present with a nonspecific prodrome of fever, myalgias, and dysphagia and high-risk behavior for mpox.

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

Our case highlights a rare but serious complication from infection with mpox, resulting in tonsillar abscess with airway compromise. It also emphasizes the high degree of suspicion required for diagnosing mpox in high-risk populations. This patient, a transgender woman with controlled HIV and a recent unprotected sexual encounter with a male, presented to the ED three times with sore throat before mpox was considered. The diagnosis of mpox continues to be delayed in light of atypical presentations and nonspecific symptoms, such as sore throat, likely contributing to continued spread within our communities (9).

References

- 1.Huhn GD, Bauer AM, Yorita K, et al. Clinical characteristics of human monkeypox, and risk factors for severe disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1742–1751. doi: 10.1086/498115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Monkeypox outbreak- nine states, May 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(23):764. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7123e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCollum AM, Damon IK. Human monkeypox. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:260–267. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit703. [published correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Jun;58(12):1792] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Titanji BK, Tegomoh B, Nematollahi S, Konomos M, Kulkarni PA. Monkeypox: a contemporary review for healthcare professionals. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9(7):ofac310. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofac310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thornhill JP, Barkati S, Walmsley S, et al. Monkeypox virus infection in humans across 16 countries - April-June 2022. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:679–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jezek Z, Szczeniowski M, Paluku KM, Mutombo M. Human monkeypox: clinical features of 282 patients. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:293–298. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sejvar JJ, Chowdary Y, Schomogyi M, et al. Human monkeypox infection: a family cluster in the midwestern United States. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:1833–1840. doi: 10.1086/425039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davido B, D'Anglejan E, Baudoin R, et al. Monkeypox outbreak 2022: an unusual case of peritonsillar abscess in a person previously vaccinated against smallpox. J Travel Med. 2022;29(6):taac082. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taac082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampson MM, Polk CM, Fairman RT, et al. Monkeypox testing delays: the need for drastic expansion of education and testing for monkeypox virus. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2022 doi: 10.1017/ice.2022.237. ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel A, Bilinska J, Tam JCH, et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. BMJ. 2022;378 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-072410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]