Abstract

Community structure is reported to play a critical role in ecosystem stability, which indicates the ability of a system to return to equilibrium after perturbations. However, current studies rely on the assumption that the community consists of only a single-layer structure. In practice, multi-layer structures are common in ecosystems, e.g. the distributions of both microorganisms in strata and fish in the ocean usually stratify into multi-layer structures. Here we use multi-layer networks to model species interactions within each layer and between different layers, and study the stability of multi-layer ecosystems under different interaction types. We show that competitive interactions within each layer have a more substantial stabilizing effect in multi-layer ecosystems relative to their impact in single-layer ecosystems. Surprisingly, between different layers, we find that competition between species destabilizes the ecosystem. We further provide a theoretical analysis of the stability of multi-layer ecosystems and confirm the robustness of our findings for different connectances between layers, numbers of species in each layer, and numbers of layers. Our work provides a general framework for investigating the stability of multi-layer ecosystems and uncovers the double-sided role of competitive interactions in the stability of multi-layer ecosystems.

Keywords: ecosystems, stability, system structures, multi-layer, competition

1. Introduction

Studying the stability of ecosystems is essential to the conservation of ecosystems [1–11]. Indeed, stability captures the ability of a system to return to its equilibrium after external perturbations. It has been pointed out that the underlying structural properties of ecosystems significantly influence the system’s stability [4,12–15]. For example, May reported that for a random community where species interact randomly, it is hard to be stable if the system is sufficiently large or complex [1,2]. By contrast, other types of non-random interactions (such as predator–prey, mutualism or competition) can significantly change the stability of the community, with predator–prey stabilizing ecosystems most [3,4]. Other related explorations pertaining to heterogeneous structures (such as small-world and scale-free) also show that the underlying structure has a non-negligible impact on the stability of ecosystems [16].

In the current framework, studies have mainly considered the stability of different community structures under the assumption that the community structure only contains a single layer [14,16–18]. By contrast, little attention has been given to the stability of multi-layer ecosystems, despite there existing various definitions of multi-layer ecosystems. Generally speaking, the multi-layer ecosystem always contains a multitude of species interacting with each other in multiple patterns, and in the hierarchical structure, species generally interact with others only in the same and adjacent layers [19–23]. For example, distributions of fish in the ocean and microorganisms in geology both exhibit a hierarchical structure. The hierarchy generally restricts species from interacting only with species in the same or adjacent layers. Species in the same layer have similar biological properties and often compete for limited resources [24]. By contrast, species between adjacent layers can interact in many ways: competition, predator–prey, mutualistic, etc. Existing results demonstrate that the multi-layer structure can significantly affect the dynamical behaviour of the system, such as facilitating the evolution of cooperation and accelerating the dispersion of information [25–27]. Exploring the stability of such multi-layer ecosystems can help us better understand and protect ecosystems. Although multi-layer ecosystems are ubiquitous in nature, the study of the stability of such ecosystems is rare.

In network science, multi-layer networks have been frequently used to describe multiple interactions in nature and human societies recently [28–30]. Related models and analysis methods in multi-layer networks provide powerful tools for studying ecosystems with multi-layer structures. An intuitive way to describe multi-layer ecosystems is to use a multi-layer network in which each node appears on only one layer and interacts with other nodes within the same layer and between different layers [19]. Based on the framework of multi-layer networks, we explore the effect of the multi-layer structure with various types of interactions on the stability of ecosystems [19–21]. Here we mainly focus on the comparison of the stability between the multi-layer and the corresponding unstructured ecosystems. To ensure a fair comparison where the unstructured ecosystem has the same corresponding parameters, the number of species in each layer is set to be equal and each species could only occur in one layer.

We find that, compared with the corresponding unstructured case, the multi-layer structure plays a vital role in the stability of ecosystems. Specifically, multi-layer structures can stabilize ecosystems when interactions within the same layer are competitive, which is consistent with the role of competition in single-layer ecosystems [24]. Surprisingly, we find that multi-layer structures tend to destabilize ecosystems when interactions between different layers are competition. We provide mathematical analysis to estimate the stability of two-layer ecosystems. Furthermore, we investigate the effects of varying connectivity within the same layer and between different layers, the number of species in different layers, and the number of layers on the stability of ecosystems through simulations and theoretical analysis. We find that these modifications still support our main conclusions.

2. Results

2.1. Building community matrix

Following May’s framework [1,2], we employ the following ordinary differential equations to capture the interaction dynamics of S species

| 2.1 |

where X(t) = [X1(t), X2(t), …, XS(t)]T represents the density of each species at time t, and f(X(t)) describes the specific interactions between species.

By linearization, the dynamical behaviour near the feasible equilibrium point X* of the above system can then be represented by

| 2.2 |

where f(X*) = 0, J = ∂f/∂X and x(t) = X(t) − X*. is the community matrix of the ecosystem, which is usually denoted by M.

The linearized system in equation (2.2) is asymptotically stable near the equilibrium only when the real part of each eigenvalue of M is negative. Thus, the stability of the ecosystem is determined by the largest real part among all eigenvalues of M, Re(λM,1). The corresponding equilibrium is defined to be stable when Re(λM,1) is negative, while a positive Re(λM,1) indicates that the system is unstable [1,3]. We construct the community matrix M as follows: (i) constructing an adjacency matrix K, where species i can interact with j if Kij = 1; (ii) constructing an interaction strength matrix W, where (Wij, Wji) is drawn from a bivariate distribution; (iii) for the community matrix M, Mij = Kij × Wij; and (iv) setting all diagonal elements Mii = −d, where d is a positive constant.

Due to the limitation that species can only interact with species within the same layer and between adjacent layers, we know that adjacency matrix K is a tri-diagonal block matrix, where diagonal blocks represent interactions within the same layer and sub-diagonal blocks represent interactions between adjacent layers. Species within the same layer interact with probability Cw, while they interact with probability Cb between adjacent layers.

For interactions between species, we consider the following four interaction types [3,31]:

-

—

Random: Species i and j interact randomly, Wij and Wji are drawn from a normal distribution N(0, σ2) independently.

-

—

Mutualistic (+/ +): Species i and j interact positively, Wij and Wji are independently drawn from the distribution |X|, where X ∼ N(0, σ2).

-

—

Competitive (−/ −): Species i and j interact competitively, Wij and Wji are independently drawn from the distribution −|X|, where X ∼ N(0, σ2).

-

—

Predator–prey (+/ −): Wij and Wji have different signs, one is drawn from the distribution −|X|, and the other is drawn independently from the distribution |X|, where X ∼ N(0, σ2).

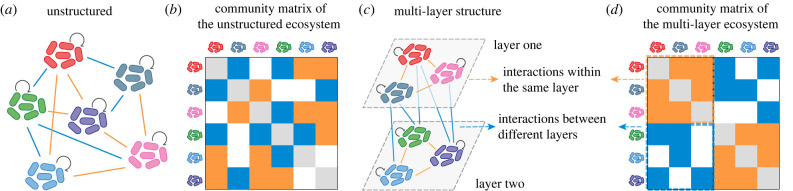

For simplicity, we use (Iw, Ib) to indicate the interaction types of the community: Iw for interactions within the same layer, and Ib for interactions between different layers. Since K is a tri-diagonal block matrix, we can know that M is also a tri-diagonal block matrix with connectance Cw in diagonal blocks and connectance Cb in sub-diagonal blocks (figure 1c,d).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the unstructured and corresponding multi-layer ecosystem. (a) Interactions among six species in a random (unstructured) ecological network. Each species can interact with others in different interaction types (coloured lines). Here the proportions of two different interaction types are 6/11 and 5/11. (b) Community matrix of the unstructured ecosystem in (a), and the colour in each element corresponds to the interaction type shown in (a). (c) One of the possible corresponding multi-layer ecosystems of (a), where the parameters (the number of species, the number of interactions, species connectance, etc.) are identical to the unstructured ecosystem in (a) except for the setting of the interaction types between species. Interaction types among species within each layer and between different layers are confined by the multi-layer structure, with one type of interaction within the layer and another type of interaction between layers. (d) Community matrix of the multi-layer structure in (c), whose diagonal blocks and off-diagonal blocks describe interactions within the same layer and between different layers, respectively.

2.2. Competition within the same layer stabilizes while competition between different layers destabilizes multi-layer ecosystems

To study the effect of multi-layer structure on the stability of ecosystems, mathematically we compare the largest real part of the eigenvalue of M and , where is a matrix with the same coefficients, but rearranged in a random single-layer structure (figure 1a,b). Note that here we use −Re(λM,1) and represent the stability of multi-layer ecosystems and the corresponding unstructured ecosystems, respectively [4].

Our principal result reveals that competition within the same layer enhances the stability of ecosystems in multi-layer ecological networks, regardless of the interaction type between different layers and the network connectivity. Figure 2a–f shows that the combination of competition within the same layer and mutualism between different layers has an obvious effect on fostering the stability of multi-layer ecosystems when the number of layers L = 2. And competition within each layer can always enhance the stability of multi-layer ecosystems (figure 2g). This result reveals that such multi-layer ecosystems where species in the same layer compete for limited resources, while species between different layers always cooperate or interact in other ways, are more likely to be stable. Furthermore, we theoretically give stability criteria for the corresponding multi-layer ecosystems.

Figure 2.

Multi-layer structures stabilize ecosystems with competition within each layer. (a–c) Illustration of multi-layer structures and the corresponding unstructured ecosystems at different connectance (high, middle and low), where interactions within each layer are competition and between layers are mutualism. (d–f) The change of the relative abundance of each species with time after the same external perturbations for multi-layer and the corresponding unstructured ecosystems shown in (a–c). As to different connectances within each layer (Cw) and between different layers (Cb), we find that the multi-layer ecosystem is always stable for dense (Cw = Cb = 1), medium (Cw = Cb = 2/3) and sparse (Cw = Cb = 1/3) connections (left panel in (d–f)), while the corresponding unstructured case is unstable (right panel in (d–f)). (g) For different combinations of interaction types (predator–prey ( + / − ), mutualism ( + / + ), competitive ( − / − ) and random) within the same layer and between different layers, we calculate the ΔStability of multi-layer and the corresponding unstructured ecosystems, where ΔStability = Stability (multi-layer) − Stability (unstructured). Here we show that competition within each layer has a stabilizing effect (first row), while between different layers has a destabilizing effect (first column). In (a–f), the abundance of each species before perturbation is 1, while the perturbation is taken from a uniform distribution of [ − 1, 1] for each species. Interaction strengths for species within the same layer are drawn from −|X|, while between different layers are drawn from |X|, where X ∼ N(0, σ2), σ = 0.5. In (g), we set the number of layers L = 2, the number of species in each layer Si = 500, i = 1, 2, σ = 0.05, and Cw = Cb = 1/3 (left), Cw = Cb = 2/3 (middle), Cw = Cb = 1 (right). Each value is obtained by averaging over 50 replicates.

Surprisingly, we also find that competition between different layers destabilizes multi-layer ecosystems (figure 2g). Species are more likely to become extinct since they cannot be replenished from species in other layers and instead increase depletion. Then the ecosystem loses stability. According to May’s work [1,2], the larger the network connectivity, the more likely the ecosystem will be unstable. However, increased network connectivity enhances the stabilizing effect of multi-layer structures compared with the corresponding unstructured ecosystems. Our analysis highlights the fact that multi-layer structures profoundly alter the stability of ecosystems. To check the robustness of our results beyond the linear stability, we further consider the recovery time of ecosystems, stochasticity, nonlinearity and ecosystem collapse in our model. And we find that all these factors do not change our conclusions qualitatively.

Next, we give a mathematical analysis for the stability criterion when Cw = Cb = C, the number of layers L = 2, and the number of species in each layer Si = S, i = 1, 2. Here we focus on the case when interactions within the same layer are competition:

-

(1) When interactions between different layers are mutualism or competition, the largest real part of the eigenvalues of M is given by

2.3 -

(2) When interactions between different layers are predator–prey, the largest real part of the eigenvalues of M is given by

2.4 -

(3) When interactions between different layers are random, the largest real part of the eigenvalues of M is given by

If Re(λM,1) < 0, the ecosystem is stable. Thus, we can get the corresponding stability criteria in equations (2.3), (2.4) and (2.5). In general, we give a framework to calculate the stability criterion of arbitrary compositions of interaction types within and between layers when L = 2 (see electronic supplementary material). And we find that the stability criterion of multi-layer ecosystems is much less strict than the corresponding unstructured case when interactions within the same layer are competition [24].2.5

2.3. Impact of connectance within the same layer and between different layers on the stability of multi-layer ecosystems

Next, we show the effect of connectance on the stability of multi-layer ecosystems when interactions within the same layer (Cw) are competition (figure 3a–c) or between different layers are competition (Cb) (figure 3d,e). For interactions with Iw and Ib, the corresponding overall percentages fw, fb of the ratio of interaction within each and between different layers are

Note that there are various angles to characterize the ‘complexity’ of ecosystems [32–34], here the ‘complexity’ portrays the network connectance in our model [1,2]. Thus the increase of Cb makes the system more complex (the connectance of the whole ecosystem increases). And for different connectance within the same layer and between different layers, we find that it is robust for competition within the same layer to enhance the stability of multi-layer ecosystems (figure 3a–c). By contrast, competition between different layers continually destabilizes the ecosystem (figure 3d–f). According to May’s theory, the stability of the ecosystem will decrease.

Figure 3.

Effect of species connectance between different layers on the stability. We plot the stability of the multi-layer ecosystem (blue) and the corresponding unstructured case (orange) by fixing the other parameters and varying the level of connectance between different layers, Cb. (a–c) Interactions within the same layer are competition ( − / − ), and between different layers are mutualism ( + / + ), predator–prey ( + / − ) and random (from left to right), respectively. (d–f) Interactions between different layers are competition, and within the same layer are mutualism, predator–prey and random (from left to right), respectively. We set the number of layers L = 2, the number of species in each layer Si = 100, i = 1, 2, species connectance within each layer Cw = 0.5, σ = 0.05, and vary Cb from 0 to 1. Each box chart is obtained from over 50 replicates.

For competition within the same layer and prey–predator between different layers, predator–prey’s stabilizing effect counteracts the competitive interactions’ destabilizing effects, so the ecosystem becomes more stable with increasing the amount of predator–prey interactions (figure 3b). Generally, the stability of ecosystems is decreasing with increasing Cb as shown in figure 3, which is consistent with May’s law [1,2]. However, for mutualism within the same layer and competition between different layers, the corresponding unstructured ecosystem will become more stable first, and then its stability will decrease since increasing competition interactions will neutralize the mutualism effects first and then drive the ecosystem unstable (figure 3d).

We give a mathematical analysis for the stability criterion of a two-layer ecosystem when Cw ≠ Cb, and the number of species in each layer is S. Here we also focus on when the interactions within the same layer are competition:

-

(1) When interactions between different layers are mutualism or competition, the stability criterion is

where2.6 2.7 2.8 -

(2) When interactions between different layers are predator–prey, the stability criterion is

2.9 -

(3) When interactions between different layers are random, the stability criterion is

2.10

In figure 4a, we give theoretical estimates and numerical simulations of the stability criterion when the interactions within the same layer and between different layers are all competition (stability criteria for different interaction types within and between layers are shown in electronic supplementary material). When Cb < Cw, the stability of the multi-layer ecosystem is mainly determined by interactions within the same layer. When Cb > Cw, the stability of the multi-layer ecosystem is mainly determined by interactions between different layers. Our analysis agrees with the simulation results. When Cw = Cb = C, the corresponding stability criterion degenerates to be consistent with equation (2.3) in §2.2.

Figure 4.

Theoretical analysis confirms our numerical findings on the stability of both multi-layer and unstructured ecosystems. We show the effect of Cb and S2 on the stability when interactions within the same layer and between different layers are competition. (a) We set the number of layers L = 2, the number of species in each layer Si = 100, i = 1, 2, Cw = 0.5, σ = 0.05, and vary Cb from 0 to 1 to study the case when interactions within the same layer and between different layers are competition with simulations (box lines) and theory (dashed lines). (b) We set the number of layers L = 2, S1 = 100, Cw = Cb = 1, σ = 0.05, and vary S2 from 0 to 200 to study the case when interactions within the same layer and between different layers are competition with simulations (box lines) and theory (dashed lines). Each box chart is obtained from over 50 replicates.

2.4. Impact of the number of species between different layers on the stability of multi-layer ecosystems

We find that the stabilizing effect of competition within the same layer is also robust when different layers have different sizes (S1 ≠ S2) as shown in figure 5a–c. According to May’s theory, increasing S2 will make the ecosystem larger and thus lead it to be unstable [1]. Our results in figure 5 are consistent with May’s conclusion that increasing S2 leads to instability of ecosystems except for the unstructured ecosystem in figure 5d, which corresponds to the multi-layer ecosystem with mutualism within each layer and competition between different layers. Similar to figure 3d, the increase of competition neutralizes the destabilizing effect incurred by mutualistic interactions and then destabilizes the ecosystem [24].

Figure 5.

Effect of the number of species in the second layer on the stability. We plot the stability of the multi-layer ecosystem (blue) and the corresponding unstructured case (orange) by fixing the other parameters and varying the number of species in the second layer, S2. (a–c) Interactions within the same layer are competition, and between different layers are mutualism, predator–prey and random (from left to right), respectively. (b–f) Interactions between different layers are competition, and within the same layer are mutualism, predator–prey and random (from left to right), respectively. We set the number of layers L = 2, S1 = 100, Cw = Cb = 1, σ = 0.05, and vary S2 from 0 to 200. Each box chart is obtained from over 50 replicates.

For interactions Iw and Ib, their percentages fw, fb of the ratio of interaction within each and between different layers are

and

In figure 5a–c, we show that although increasing S2 leads the ecosystem to instability, competition within the same layer enhances the stability of multi-layer ecosystems despite varying S2. Besides, competition between different layers can easily destabilize the ecosystem (figure 5d–f). The effect of the multi-layer structure is robust when interactions within the same layer or between different layers are competition, which is consistent with our previous conclusions. Remarkably, increasing S2 exacerbates the distinction between multi-layer and the corresponding unstructured ecosystems, which in turn leads to a more significant difference in their impact on stability. In figure 4b, we give the corresponding theoretical estimations [3] and numerical simulations of the stability criterion, and they are in good agreement with each other.

2.5. Impact of the number of layers on the stability of multi-layer ecosystems

In previous sections, we focused on the case L = 2. We next study the impact of the number of layers L on the stability of ecosystems. In figure 6, we show that the ecosystem will be less stable after increasing L, both for multi-layer and unstructured ecosystems. It confirms our prediction that competition within the same layer can stabilize ecosystems when interactions between different layers are random or predator–prey. However, if interactions between different layers are mutualism, increasing the number of layers may destabilize ecosystems.

Figure 6.

Effect of the number of layers on the stability. We plot the stability of the multi-layer ecosystem (blue) and the corresponding unstructured case (orange) by fixing the other parameters and varying the number of layers L. Interactions within the same layer are competition, and between different layers are mutualism, predator–prey, random and competition (from left to right), respectively. We set the number of species in each layer 100, Cw = Cb = 1, σ = 0.05, and vary L from 1 to 30. Each box chart is obtained from over 10 replicates.

For interactions Iw and Ib, their percentages fw, fb of the ratio of interaction within each and between different layers are

As L increases, the multi-layer ecosystem with competition within the layer and mutualism between different layers becomes unstable because the ratio of mutualism interactions increases twice as fast as the competition. And in this case, stabilizing effect brought by the competition cannot neutralize the destabilizing effect of mutualism. For competition between different layers, each additional layer significantly affects individuals in the adjacent layer in the multi-layer structure, which makes the system rapidly unstable. In the corresponding unstructured ecosystem, the effect of increasing competition interactions is equally shared by all individuals, so the stability of such ecosystems is not sensitive to the growing number of layers.

3. Discussion

Competitive relationships between species are prevalent, from microbial populations to plant and animal populations. For example, microorganisms in the same medium compete for nutrient solutions, plants in the same forest compete for sunlight and water, etc. [24,35–37]. According to the previous important findings [3,31], competitive relationships are conducive to system stability in a mixed population of competitive and mutualism interactions. Here we introduce multi-layer networks to study the stability of ecosystems from the perspective of community structure and find that multi-layer structure has a significant effect on the stability of ecosystems. Specifically, we show that competition within each layer has a more substantial stabilizing impact on ecosystems compared with other interaction types. Surprisingly, we find that competition between different layers has a significant destabilizing effect on ecosystems. This suggests that competitive effects do not always increase stability in communities with a multi-layer network structure. Moreover, we verify that the effects of multi-layer structures are robust and less influenced by other factors, such as the connectance within the same layer and between different layers, the number of species in each layer and the number of layers.

Multi-layer networks are one of the common topological structures in complex systems [38]. With the development of network science and corresponding computation tools, more and more studies use multi-layer networks to model complex systems [38–40]. We introduce multi-layer networks to the study of ecosystem stability and find that they play a crucial role in the stability of ecosystems. Beyond revealing that competitive interactions have completely opposite effects within and between layers. Here we find that predator–prey and random interactions perform worse than competition in stabilizing ecological communities within each layer, even though they were found to present more stabilizing effects in previous single-layer structures [3]. Furthermore, we also discuss the effect of stochasticity, strong nonlinearity and ecosystem collapse [41–44] on the stability of multi-layer and corresponding unstructured ecosystems. We find that these factors do not alter our main results qualitatively. Our findings offer a general framework to study the influence of multi-layer structures on the stability of complex ecosystems.

Future work following our framework could consider these more relevant factors, such as the mixture of interaction types in each layer, the heterogeneous structure in each layer and the niche model within and between layers, which would help us further understand the stability of ecosystems. Another potential expansion could start from more realistic networks [39,45,46], such as temporal [47–49] and higher-order networks [38,50] that are gradually attracting attention. Indeed, such extensions could introduce these network models into the study of ecosystem stability, making the study of ecosystem stability more relevant to empirical systems.

Acknowledgements

We thank Yao Meng, Guocheng Wang, Anzhi Sheng and Guyu Hou for valuable discussions.

Contributor Information

Aming Li, Email: liaming@pku.edu.cn.

Long Wang, Email: longwang@pku.edu.cn.

Data accessibility

The electronic supplementary material is available on Figshare [51].

Authors' contributions

Y.W.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; Y.Y.: data curation, formal analysis, visualization, writing—review and editing; A.L.: conceptualization, data curation, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; L.W.: conceptualization, formal analysis, methodology, funding acquisition, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China under grant no. 2022YFA1008400, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant nos. 62036002 and 62173004, Beijing Nova Program, China under grant no. Z211100002121105, the Emerging Engineering Interdisciplinary-Young Scholars Project, Peking University, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and PKU-Baidu Fund, China under grant no. 2020BD017.

References

- 1.May RM. 1972. Will a large complex system be stable? Nature 238, 413-414. ( 10.1038/238413a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.May RM. 2001. Stability and complexity in model ecosystems. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allesina S, Tang S. 2012. Stability criteria for complex ecosystems. Nature 483, 205-208. ( 10.1038/nature10832) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allesina S, Grilli J, Barabás G, Tang S, Aljadeff J, Maritan A. 2015. Predicting the stability of large structured food webs. Nat. Commun. 6, 7842. ( 10.1038/ncomms8842) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harvey E, Gounand I, Ward CL, Altermatt F. 2017. Bridging ecology and conservation: from ecological networks to ecosystem function. J. Appl. Ecol. 54, 371-379. ( 10.1111/1365-2664.12769) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Worm B, Duffy JE. 2003. Biodiversity, productivity and stability in real food webs. Trends Ecol. Evol. 18, 628-632. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.003) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray C, Ma A, McLaughlin O, Petit S, Woodward G, Bohan DA. 2021. Ecological plasticity governs ecosystem services in multilayer networks. Commun. Biol. 4, 75. ( 10.1038/s42003-020-01547-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorren LKA, Berger F, Imeson AC, Maier B, Rey F. 2004. Integrity, stability and management of protection forests in the European Alps. For. Ecol. Manag. 195, 165-176. ( 10.1016/j.foreco.2004.02.057) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbier EB, et al. 2014. Ecology: protect the deep sea. Nature 505, 475-477. ( 10.1038/505475a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu J, Amor DR, Barbier M, Bunin G, Gore J. 2022. Emergent phases of ecological diversity and dynamics mapped in microcosms. Science 378, 85-89. ( 10.1126/science.abm7841) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu J, Jafari S, Han Y, Grodzinsky AJ, Cai S, Guo M. 2017. Size- and speed-dependent mechanical behavior in living mammalian cytoplasm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9529-9534. ( 10.1073/pnas.1702488114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allesina S, Pascual M. 2008. Network structure, predator–prey modules, and stability in large food webs. Theor. Ecol. 1, 55-64. ( 10.1007/s12080-007-0007-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costa JM, Ramos JA, Timóteo S, Silva LP, Ceia RS, Heleno RH. 2020. Species temporal persistence promotes the stability of fruit–frugivore interactions across a 5-year multilayer network. J. Ecol. 108, 1888-1898. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.13391) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohr RP, Saavedra S, Bascompte J. 2014. On the structural stability of mutualistic systems. Science 345, 416-425. ( 10.1126/science.1253497) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angulo MT, Moog CH, Liu YY. 2019. A theoretical framework for controlling complex microbial communities. Nat. Commun. 10, 1045. ( 10.1038/s41467-019-08890-y) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan G, Martinez ND, Liu YY. 2017. Degree heterogeneity and stability of ecological networks. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170189. ( 10.1098/rsif.2017.0189) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White L, O’Connor NE, Yang Q, Emmerson MC, Donohue I. 2020. Individual species provide multifaceted contributions to the stability of ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1594-1601. ( 10.1038/s41559-020-01315-w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melián CJ, Bascompte J, Jordano P, Krivan V. 2009. Diversity in a complex ecological network with two interaction types. Oikos 118, 122-130. ( 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.16751.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilosof S, Porter MA, Pascual M, Kéfi S. 2017. The multilayer nature of ecological networks. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0101. ( 10.1038/s41559-017-0101) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hutchinson MC, Bramon Mora B, Pilosof S, Barner AK, Kéfi S, Thébault E, Jordano P, Stouffer DB. 2019. Seeing the forest for the trees: putting multilayer networks to work for community ecology. Funct. Ecol. 33, 206-217. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.13237) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silk MJ, Finn KR, Porter MA, Pinter-Wollman N. 2018. Can multilayer networks advance animal behavior research? Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 376-378. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2018.03.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finn KR, Silk MJ, Porter MA, Pinter-Wollman N. 2019. The use of multilayer network analysis in animal behaviour. Anim. Behav. 149, 7-22. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2018.12.016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angulo MT, Kelley A, Montejano L, Song C, Saavedra S. 2021. Coexistence holes characterize the assembly and disassembly of multispecies systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1091-1101. ( 10.1038/s41559-021-01462-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coyte KZ, Schluter J, Foster KR. 2015. The ecology of the microbiome: networks, competition, and stability. Science 350, 663-666. ( 10.1126/science.aad2602) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Interdonato R, Magnani M, Perna D, Tagarelli A, Vega D. 2020. Multilayer network simplification: approaches, models and methods. Comput. Sci. Rev. 36, 100246. ( 10.1016/j.cosrev.2020.100246) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muldoon SF, Bassett DS. 2016. Network and multilayer network approaches to understanding human brain dynamics. Philos. Sci. 83, 710-720. ( 10.1086/687857) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Omodei E, De Domenico M, Arenas A. 2017. Evaluating the impact of interdisciplinary research: a multilayer network approach. Netw. Sci. 5, 235-246. ( 10.1017/nws.2016.15) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su Q, McAvoy A, Mori Y, Plotkin JB. 2022. Evolution of prosocial behaviours in multilayer populations. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 338-348. ( 10.1038/s41562-021-01241-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kivela M, Arenas A, Barthelemy M, Gleeson JP, Moreno Y, Porter MA. 2014. Multilayer networks. J. Complex Netw. 2, 203-271. ( 10.1093/comnet/cnu016) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Domenico M, Solé-Ribalta A, Cozzo E, Kivelä M, Moreno Y, Porter MA, Gómez S, Arenas A. 2013. Mathematical formulation of multilayer networks. Phys. Rev. X 3, 041022. ( 10.1103/PhysRevX.3.041022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allesina S, Tang S. 2015. The stability–complexity relationship at age 40: a random matrix perspective. Popul. Ecol. 57, 63-75. ( 10.1007/s10144-014-0471-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Y, Di Z, Gerlee P. 2022. Ladderpath approach: how tinkering and reuse increase complexity and information. Entropy 24, 1082. ( 10.3390/e24081082) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solé R, Levin S. 2022. Ecological complexity and the biosphere: the next 30 years. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 377, 20210376. ( 10.1098/rstb.2021.0376) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solé R, Bascompte J. 2006. Self-organization in complex ecosystems. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coyte KZ, Tabuteau H, Gaffney EA, Foster KR, Durham WM. 2017. Microbial competition in porous environments can select against rapid biofilm growth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E161-E170. ( 10.1073/pnas.1525228113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coyte KZ, Rakoff-Nahoum S. 2019. Understanding competition and cooperation within the mammalian gut microbiome. Curr. Biol. 29, R538-R544. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grilli J, Barabás G, Michalska-Smith MJ, Allesina S. 2017. Higher-order interactions stabilize dynamics in competitive network models. Nature 548, 210-213. ( 10.1038/nature23273) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallotti R, Barthelemy M. 2015. The multilayer temporal network of public transport in Great Britain. Sci. Data 2, 140056. ( 10.1038/sdata.2014.56) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J, Buldyrev SV, Havlin S, Stanley HE. 2011. Robustness of a network of networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 195701. ( 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.195701) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao J, Li D, Havlin S. 2014. From a single network to a network of networks. Natl Sci. Rev. 1, 346-356. ( 10.1093/nsr/nwu020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tahara T, et al. 2018. Asymptotic stability of a modified Lotka-Volterra model with small immigrations. Sci. Rep. 8, 1-7. ( 10.1038/s41598-018-25436-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y, Sumpter D. 2017. Insights into resource consumption, cross-feeding, system collapse, stability and biodiversity from an artificial ecosystem. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20160816. ( 10.1098/rsif.2016.0816) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kessler DA, Shnerb NM. 2015. Generalized model of island biodiversity. Phys. Rev. E 91, 042705. ( 10.1103/PhysRevE.91.042705) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loreau M, De Mazancourt C. 2013. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: a synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 16, 106-115. ( 10.1111/ele.12073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gao J, Barzel B, Barabási AL. 2016. Universal resilience patterns in complex networks. Nature 530, 307-312. ( 10.1038/nature16948) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rohr RP, Naisbit RE, Mazza C, Bersier LF. 2016. Matching–centrality decomposition and the forecasting of new links in networks. Proc. R. Soc. B 283, 20152702. ( 10.1098/rspb.2015.2702) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Angulo MT, Moreno JA, Lippner G, Barabási AL, Liu YY. 2017. Fundamental limitations of network reconstruction from temporal data. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20160966. ( 10.1098/rsif.2016.0966) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li A, Cornelius SP, Liu YY, Wang L, Barabási AL. 2017. The fundamental advantages of temporal networks. Science 358, 1042-1046. ( 10.1126/science.aai7488) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li A, Zhou L, Su Q, Cornelius SP, Liu YY, Wang L, Levin SA. 2020. Evolution of cooperation on temporal networks. Nat. Commun. 11, 2259. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-16088-w) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fath BD, Scharler UM, Ulanowicz RE, Hannon B. 2007. Ecological network analysis: network construction. Ecol. Modell. 208, 49-55. ( 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2007.04.029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y, Yang Y, Li A, Wang L. 2023. Stability of multi-layer ecosystems. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6423936) [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The electronic supplementary material is available on Figshare [51].