Abstract

We provide the first assessment of fungal diversity associated with historic wooden structures at Whalers Bay (Heritage Monument 71), Deception Island, maritime Antarctic, using DNA metabarcoding. We detected a total of 177 fungal amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) dominated by the phyla Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, Chytridiomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Rozellomycota, and Zoopagomycota. The assemblages were dominated by Helotiales sp. 1 and Herpotrichiellaceae sp. 1. Functional assignments indicated that the taxa detected were dominated by saprotrophic, plant and animal pathogenic, and symbiotic taxa. Metabarcoding revealed the presence of a rich and complex fungal community, which may be due to the wooden structures acting as baits attracting taxa to niches sheltered against extreme conditions, generating a hotspot for fungi in Antarctica. The sequences assigned included both cosmopolitan and endemic taxa, as well as potentially unreported diversity. The detection of DNA assigned to taxa of human and animal opportunistic pathogens raises a potential concern as Whalers Bay is one of the most popular visitor sites in Antarctica. The use of metabarcoding to detect DNA present in environmental samples does not confirm the presence of viable or metabolically active fungi and further studies using different culturing conditions and media, different growth temperatures and incubation periods, in combination with further molecular approaches such as shotgun sequencing are now required to clarify the functional ecology of these fungi.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s42770-022-00869-0.

Keywords: Antarctica, Extremophiles, Heritage site, Fungi, Taxonomy

Introduction

Historical buildings and other human artifacts are present in Antarctica, originally built as shelters for personnel and equipment in the early era of human contact with the continent during the eras of seal and whale hunting and geographical exploration. Today, some of the remaining structures and their environs are considered under the Antarctic Treaty as heritage sites and are protected for their historic significance [1]. The origins and history of the diverse wooden structures present in Whalers Bay on Deception Island are described by Held and Blanchette [2]. Deception Island was initially used by sealers and whalers as shelter from the storms and poor sea conditions typifying the region, taking advantage of its flooded caldera. The onshore Hektor whaling station, originally constructed by Norwegian whalers in 1911, also provided support for whaling factory ships.

After the demise of the South Shetland Islands whaling industry in the 1930s, in 1944 the British Second World War Operation Tabarin used the site and established a wooden building, as well as utilizing some of the existing whaling station structures, calling it Base B. Soon after the end of the war, this facility was transferred to the newly established Falkland Island Dependencies Survey, who subsequently established a runway and hangar facility, using it primarily as a base for aerial surveys in the South Shetland Islands and western Antarctic Peninsula region. Thus, over time, many wooden buildings and other structures were added, with some still present today in various stages of deterioration. In 1995, these remains were designated for protection under the Antarctic Treaty as Antarctic Historic Site or Monument 71 (HSM-71). Nevertheless, it is increasingly apparent that the wooden structures in these heritage sites have faced microbial attack over recent decades, drawing attention to the challenge of achieving long-term preservation [1].

The presence of anthropogenically imported wooden structures and artifacts in different locations in Antarctica provides an opportunity to study the microbial life that has colonized them under the continent’s extreme conditions over time. Fungi are able to colonize different environments and habitats despite the extreme conditions, typically developing highly diverse communities and being the dominant group of microbial decomposers present [3]. According to Hughes and Bridge [4], of more than 1000 non-lichenized fungi that had been reported at that time from the Antarctic and sub-Antarctic regions, only 2–3% were considered truly psychrophilic species. Rather, those with mesophilic or psychrotolerant growth characteristics generally dominated the known diversity [3, 5].

Fungi are a diverse group of microorganisms with considerable ability to function under the different stresses that typify polar environments. The majority of mycological studies in Antarctica to date have focused on cultivable species, mainly represented by taxa of the phylum Ascomycota, followed, in rank, by Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, Mucoromycota, Chytridiomycota, and Glomeromycota [3]. In Antarctica, fungi form part of complex ecological networks, including saprophytic, mutualistic, and parasitic taxa [2, 3, 5]. However, little is known in detail about the diversity and decomposition functions of fungi in polar environments in comparison with temperate and tropical areas [2]. Fungal communities associated with wooden structures and artifacts in Antarctica have been reported in various studies [6–12]. However, these studies applied only traditional culturing approaches, which recover only cultivable fungi and do not accurately reflect overall diversity. With recent developments in the application of DNA sequencing techniques, we hypothesized that the DNA metabarcoding using high-throughput sequencing (HTS) would allow the identification of previously unrecognized cryptic fungal sequence diversity present on the historic wooden structures in Whalers Bay, Deception Island, maritime Antarctica.

Methods

Study sites and historic wood sampling

Wood samples were obtained at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands (Fig. 1). Wood fragments were collected directly from four different locations/structures: Biscoe House, a beached whaling boat, the Biscoe House Annex, and the Hunting Lodge (Fig. 2), all of which are included in HSM-71. Three small samples (ca. 3 cm3) of wood from each site were obtained during the Antarctic summer (December 2016) and stored in individual sterilized Whirl–Pak bags (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), which were sealed and kept at – 20 °C until they were processed at the Microbiology Laboratory of the Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil. There, each sample was gradually thawed at 4 °C for 24 h before carrying out DNA extraction. All DNA extraction took place under strict control conditions within a laminar flow hood in order to avoid contamination. The wooden structures at Whalers Bay are designated for protection according to the Antarctic Treaty as Antarctic Historic Site or Monument 71 (HSM-71). For this reason, we obtained a special authorization to recover small sample fragments (ca. 3 cm3) for our study and followed the Antarctic Treaty rules (see “Ethics approval” section).

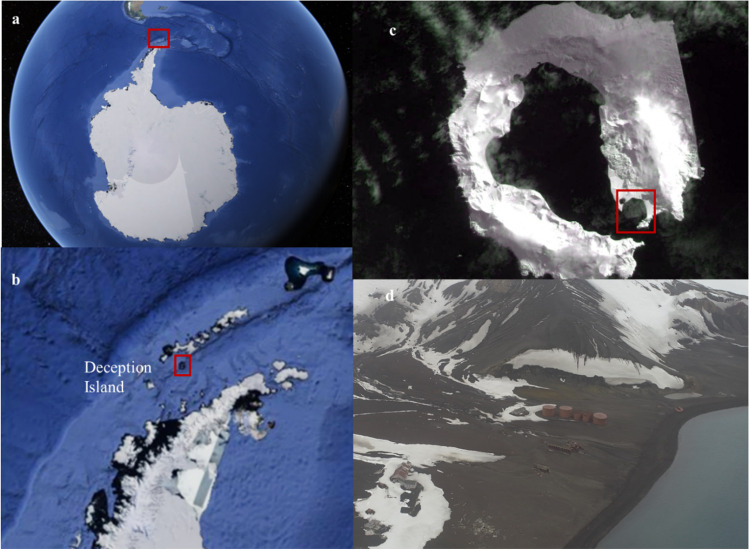

Fig. 1.

Location of Whalers Bay, Deception Island, in the South Shetland Islands, maritime Antarctica, where the wood samples were obtained. Satellite images a, b, and c were obtained using Google Earth Pro, 2019 (www.google.com.br/earth/about/versions). a Antarctica with the South Shetland Islands within the red rectangle; b Deception Island in the South Shetland Islands within the red rectangle; c Whalers Bay, Deception Island (62°57′S and 60°38′W); and d aerial view of Whalers Bay ruins (62° 58′ 52.0″ S; 60° 39′ 52.9″ W). Photo d taken by Luiz H. Rosa

Fig. 2.

Whalers Bay ruins, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands, where the wood samples were obtained. a Biscoe House, b beached whaling boat, c Biscoe House Annex, and d Hunting Lodge. Photos taken by Luiz H. Rosa

DNA extraction, Illumina library construction, and sequencing

From each wooden fragment sample (total of 12), we obtained three replicate sub-samples of about 1 cm3, which were then mixed and subjected to total DNA extraction. From each site, we analyzed 36 environmental DNA samples. Total DNA was extracted using an SDS extraction method [13–15]. Briefly, the sub-samples were added to plastic tubes containing 2 mL of SDS extraction buffer (0.1 M EDTA at pH 8 and 2% SDS), ground with sterilized iron beads for 3 min, and then incubated at 55 °C for 16 h. Then, 330 µL of 5 M NaCl and 330 µL of pre-heated CTAB 10% (55 °C) were added, the solution was vortexed, spun down, and incubated at 55 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was then transferred to a new 2-mL tube and 600 µL of chloroform was added and vortexed at maximum speed for 1 min. The tubes were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 10 min and the supernatant again transferred to a new tube.

The extracted DNA from the wood samples was cleaned using the Genomic DNA purification Kit (QIAGEN, Carlsbad, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quality was analyzed using agarose gel electrophoresis (1% agarose in 1 × Trisborate-EDTA), quantified using the Quanti- iT™ Pico Green dsDNA Assay (Invitrogen), and the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) of the nuclear ribosomal DNA used as a DNA barcode for molecular species identification of fungi [16, 17] using the universal primers ITS3 and ITS4 [18]. Library construction and DNA amplification were performed using the Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase Nextera XT Index Kit V2, following Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation protocol (Part #15,044,223, Rev. B). Paired-end sequencing (2 × 300 bp) was performed on a MiSeq plataform (Illumina) by Macrogen Inc. (South Korea). All quality control to avoid DNA contamination was carried out by Macrogen Inc.

Data analysis and fungal identification

Sequence quality analysis was carried out using BBDuk v. 38.87 in BBmap software [19] with the following parameters: Illumina adapters removing (Illumina artefacts and the PhiX Control v3 Library); ktrim = l; k = 23; mink = 11; hdist = 1; minlen = 50; tpe; tbo; qtrim = rl; trimq = 20; ftm = 5; maq = 20. The remaining sequences were imported to QIIME2 version 2021.4 (https://qiime2.org/) for bioinformatics analyses [2]. The qiime2-dada2 plugin was used for filtering, dereplication, turn paired-end fastq files into merged, and remove chimeras, using default parameters [20]. Taxonomic assignments were determined for amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) in three steps. First, ASVs were classified using the qiime2-feature-classifier [21] classify-sklearn against the UNITE Eukaryotes ITS database version 8.3 [22]. Second, remaining unclassified ASVs were filtered and aligned against the filtered NCBI non-redundant nucleotide sequences (nt) database (October 2021) using BLASTn [23] with default parameters; the nt database was filtered using the following keywords: “ITS1,” “ITS2,” and “internal transcribed spacer.” Third, output files from BLASTn were imported to MEGAN6 [24] and taxonomic assignments were obtained using the “megan-nucl-Jan2021.db” mapping file with default parameters and trained with Naive Bayes classifier and a confidence threshold of 98.5%. All DNA sequences read before and after analysis are provided in Table S1. Taxonomic profiles were plotted using the Krona [25]. The heatmap of ASV abundance and clustering analysis were performed using Heatmapper [26]; clustering analysis was performed using the following parameters: average linkage, Spearman rank correlation, and Z-score among samples for each ASV.

Many factors, including extraction, PCR, and primer bias, can affect the number of reads obtained [27], and thus lead to misinterpretation of absolute abundance [28]. However, Giner et al. [29] concluded that such biases did not affect the proportionality between reads and cell abundance, implying that more reads are linked with higher abundance [30, 31]. Therefore, for comparative purposes, we used the number of reads as a proxy for relative abundance. Fungal classification followed Kirk et al. [32] references, and Tedersoo et al. [33], MycoBank (http://www.mycobank.org), and the Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org) databases.

Fungal diversity and ecology

The relative abundances of the ASVs were used to quantify the fungal diversity present in the wood fragments sampled, where fungal ASVs with relative abundance > 10% were considered dominant, those between 1 and 10% intermediate, and those with < 1% minor (rare) components of the fungal community [5]. The numbers of reads were used to quantify taxon diversity, richness, and dominance, using the following indices: (i) Fisher’s α, (ii) Margalef’s, and (iii) Simpson’s, respectively. In addition, species accumulation curves were obtained using the Mao Tao index. All results were obtained with 95% confidence, and bootstrap values were calculated from 1000 replicates using the PAST program 1.90 [34]. Functional assignments of fungal ASVs at generic levels were generated using FunGuild [35].

Results

Fungal taxonomy and abundance

A total of 344,493 DNA reads was detected from the four historic wood fragment samples, representing 177 fungal ASVs (Table S2), with assignments at all hierarchical taxonomic fungal levels. The Mao Tao rarefaction curves of the fungal assemblages detected in all four samples did not reach asymptote (Fig. S1), indicating that total fungal sequence diversity was greater than detected in our study. Figures 3 and S2 show the abundances of fungal ASVs at different hierarchical levels, which varied between the four samples. Taxa of Ascomycota dominated the sequence assemblages, followed by those of the phyla Basidiomycota, Mortierellomycota, Chytridiomycota, Monoblepharomycota, Rozellomycota, and Zoopagomycota, in rank order (Table S2 and Fig. 3). The sequence assemblages were dominated by the higher taxonomic level taxa Helotiales sp. 1 and Herpotrichiellaceae sp. 1, which occurred in all samples with the highest relative abundances. Nineteen taxa were classified as intermediate abundance, while the majority of the fungal sequence diversity detected represented minor components of the fungal community. Fifty-five fungal ASVs (31.07% of the total detected) could only be assigned to higher taxonomic levels (phylum, class, order, or family) and may represent taxa not currently included in the available sequence databases or be new Antarctic records and/or previously undescribed taxa.

Fig. 3.

Krona chart showing the abundances of different fungal taxonomic levels detected in wood fragment samples from a Biscoe House, b beached whaling boat, c Biscoe House Annex, and d Hunting Lodge at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands

Diversity, distribution, and functional ecology

The fungal sequence assemblages detected ranged in their ecological diversity indices (Table 1). The fungal sequence assemblage present in wood from Biscoe House displayed the highest number of taxa and diversity indices, followed by those from Biscoe House Annex, the beached whaling boat, and the Hunting Lodge.

Table 1.

Diversity indices of fungal sequence assemblages detected in the different historic wood samples obtained at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands

| Sites | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ecological index* | Biscoe House | Whaling boat | Biscoe House Annex | Hunting Lodge |

| Number of fungal ASVs** | 94 | 83 | 84 | 74 |

| Number of DNA reads | 81,434 | 99,497 | 83,530 | 80,033 |

| Fisher’s α | 767.3 | 229.4 | 247.6 | 128.8 |

| Margalef | 20.19 | 17.81 | 18.02 | 15.85 |

| Simpson | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.83 |

*All results were obtained with 95% confidence, and bootstrap values were calculated from 1000 replicates using the PAST program 1.90. **ASV, amplicon sequence variant. *All results were obtained with 95% confidence, and bootstrap values were calculated from 1000 replicates using the PAST program 1.90

Assigned taxa distribution varied across the four samples (Fig. 4 and Table S3), with each wood sample hosting some specific fungal taxa, in particular, Biscoe House, Biscoe House Annex, and the beached whaling boat, which had 28, 25, and 24 fungal ASVs assigned, respectively. The most abundant fungal ASVs overall (Helotiales sp. 1 and Herpotrichiellaceae sp. 1) were present in all four samples. Twenty-two fungal ASVs were common across the four samples, including dominant, intermediate, and rare elements of the sequence assemblages. Functional assignments of the ASVs detected at generic level are shown in Table S4, suggesting that the taxa detected were dominated by saprotrophic, plant and animal pathogenic, and symbiotic fungi, and again including dominant, intermediate, and minor components of the sequence diversity assigned.

Fig. 4.

Venn diagram showing the distribution of fungal amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) across the four wood samples obtained from Biscoe House, the abandoned whaling boat, Biscoe House Annex, and Hunting Lodge at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands. *Total relative abundance (%) in blue

Discussion

Taxonomy, diversity, and abundance

Despite the extreme conditions of Antarctica, in particular, the low temperatures and arid conditions, Antarctic historical huts and artifacts constructed from wood are facing the threat of destruction by microbial decomposition. Fungi are the primary decomposer microorganisms responsible for wood decomposition. Although using different taxonomic techniques to those in the current study, a number of studies in recent years have set out to assess the fungal diversity present in and potentially threatening Antarctica’s historical heritage [1, 6, 7, 10, 36]. However, to date, such studies have applied traditional culturing techniques, which provide a poor representation of the complete fungal diversity present. The metabarcoding approach applied in the current study revealed a more diverse fungal community (in terms of numbers of taxa assigned from the sequences obtained) relative to the studies of Blanchette et al. [1] (29.5 times greater), Held et al. [6] (22.12 times greater), Arenz et al. [7] (2.49 times greater), Duncan et al. [36] (11.8 times greater), and Blanchette et al. [10] (44.25 times greater).

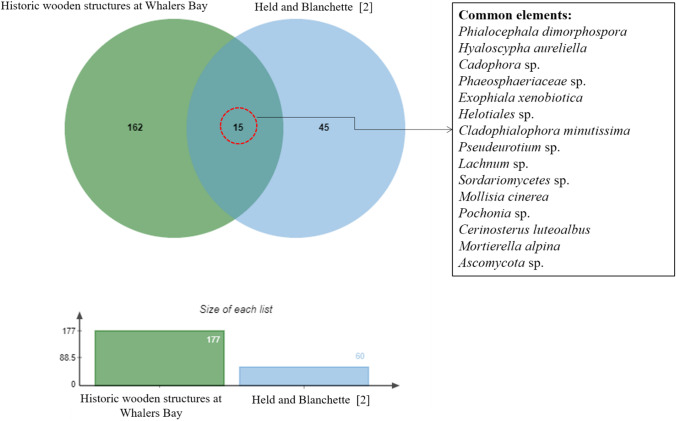

Held and Blanchette [2] applied a culturing approach in assessing the fungal diversity associated with historic wooden structures and artifacts at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, providing a direct comparison with the current study. They reported 60 taxa, about a third of that obtained here; furthermore, only 15 taxa were common to both studies (Fig. 5). Despite analyzing similar samples, the dominant taxa differed between the two studies. Among the taxa reported by Held and Blanchette [2], Cadophora species dominated the community, a known wood-decomposing genus. In contrast, our sequence data suggested that Cadophora sp. were present at low relative abundance (a minor component of the assigned fungal community). Cadophora species have been reported from various different Antarctic habitats, including moss [37, 38], angiosperms [39], and lake sediments [40], as well as from historic wooden structures [2, 9]. Some Cadophora species may have bipolar distributions, as well as having circumpolar distributions in both Antarctica and the Arctic, suggesting possession of effective adaptations to extreme polar environments [10].

Fig. 5.

Venn diagram showing the overlap in fungal amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) obtained from historic wooden structures at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands using metabarcoding approach and by Held and Blanchett [2] using traditional culturing methods

The assigned sequence data suggested dominance of Helotiales sp. 1 and Herpotrichiellaceae sp. 1 in the samples analyzed in the current study. Helotiales was also reported by Held and Blanchette [2], but at low dominance. Representatives of Helotiales have been detected in Antarctica in both traditional culturing studies and analyses of environmental DNA (eDNA), associated with plant [38, 41] and macroalgal tissues [42], in soils colonized by Antarctic plants [43, 44], and in lake sediments [40]. These fungi appear to be abundant in maritime Antarctica and, given the lack of taxonomic resolution in the sequence assignments, may represent new and/or endemic species [45].

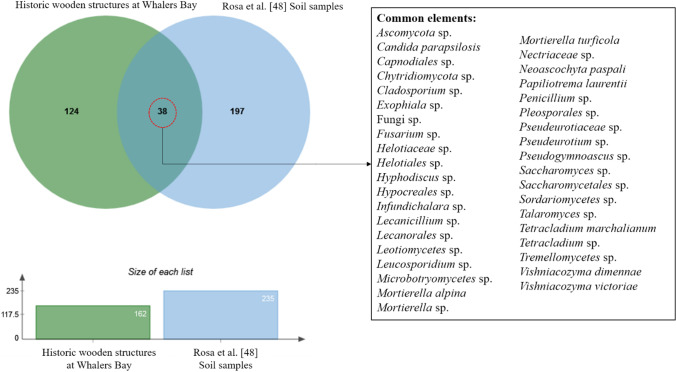

Rosa et al. [46] used metabarcoding to study the fungal community in soil samples from Whalers Bay, detecting 257 taxa. Compared with the results of the current study, only 38 taxa were present in both wood and soil samples (Fig. 6). In contrast, 197 taxa were exclusively detected from soil samples and 124 from wood samples. Among the 38 shared taxa, Helotiales sp. was the most abundant in both sample types. Despite the strong differences in sequence diversity between the wood and soil samples, some sequences from both sources were assigned to cosmopolitan taxa such as Aspergillus versicolor, Candida albicans, and C. tropicalis, while others represented Antarctic endemic taxa such as Antarctomyces sp., Friedmanniomyces endolithicus, and Glaciozyma antarctica.

Fig. 6.

Venn diagram showing the overlap in distribution of fungal amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) among the historic wooden structures at Whalers Bay, Deception Island, South Shetland Islands and soil samples analyzed by Rosa et al. [47], using a metabarcoding approach

Fifty-five ASVs (~ 30% of the total fungal community) were identified only at high hierarchical taxonomic levels (phylum, class, order, or family). These unidentified fungi may represent taxa not included in the current sequence databases or represent undescribed taxa. However, as our study focused on fungal diversity using eDNA, further specific taxonomic studies are required to confirm if the apparently high richness of these undescribed taxa represent new species or are a result of sequence database limitations.

Ecology

The fungal genera detected in the wood samples analyzed here typically display different ecological roles including saprophytes, parasites (plant and animal pathogens), and symbionts, in rank order. This fungal community functional profile has also been reported in Antarctic studies sampling fungi present in the air [5, 46], soil [47], freshwater [48], rock surfaces [49], and lake sediments [50]. The dominance of saprophytic fungi in the wood samples examined here may be due their capability to degrade available organic matter at low temperatures.

Various plant and animal pathogens occurred with high, moderate, and low relative abundance in the wood samples. The family Herpotrichiellaceae includes melanized fungi able to survive in extreme oligotrophic environments [51]. However, due to their slow growth, species of Herpotrichiellaceae are poor competitors with common fast-growing saprophytes and, for this reason, they are normally recovered in culturing studies at low frequencies [52]. Herpotrichiellaceae includes taxa that are important agents of human and animal infectious diseases such as chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis [52]. In our study, Herpotrichiellaceae sp. was the second most abundant taxon, while Cladophialophora sp. is also a member of this family, displaying intermediate or low relative abundance in the wood samples analyzed. Phialemonium sp. occurred with moderate abundance in the wood samples. This genus includes species with cosmopolitan distribution and has been reported from air, soil, industrial water, and sewage [53]. Phialemonium species are being recognized as opportunistic pathogens of humans and are associated with fungemia and endocarditis, often with fatal outcome [54]. In addition, other human and animal opportunistic fungi were detected in the wood samples at intermediate or low abundance, including members of the genera Acremonium, Candida, Exophiala, and Pseudogymnoascus.

Conclusions

Confirming our original hypothesis, and contrasting with pioneering studies using traditional culturing methods to characterize the fungal diversity associated with heritage materials from Antarctica, the application of a DNA metabarcoding approach revealed the presence of sequences assigned to a rich, diverse, and complex fungal community in wood samples obtained from Whalers Bay (HSM-71), Deception Island. The diverse fungal community detected may be a result of the historically imported wooden structures and artifacts acting as baits attracting different fungal species as well as providing microhabitats sheltering against the extreme environmental conditions and providing nutrients (organic matter) and favorable temperatures. The fungal diversity assigned on the basis of sequences detected included taxa with different global distributions and ecological profiles, with both cosmopolitan and Antarctic endemic taxa and potential previously unreported species. The assigned sequence diversity was dominated by saprophytic, plant and animal opportunistic pathogens, and symbiotic taxa. It is possible that some of the fungal taxa detected were introduced originally when the wood was first imported, typically from Europe, but they may also have arrived in Deception Island as spores dispersed by air currents, animals (such as birds), or via human activity. However, over time, native Antarctic and other cold-adapted fungi have also colonized the structures. The characterization of the fungi present in these historical sites and structures may provide information useful to conservation practitioners and in the development of strategies for fungal control and/or suppression. The detection of sequences assigned to various human and animal opportunistic pathogen species also highlights a potential risk to human health, due to Whalers Bay being one of the most visited locations in Antarctica, both by the tourism industry and national research operators. However, we recognize that metabarcoding involves the detection and assignment of DNA sequence fragments and does not confirm the presence of viable or metabolically active fungi. Further studies using different culturing conditions and media (e.g., with general, selective, solid, or broth characteristics), different growth temperatures and incubation periods, in combination with further molecular approaches such as shotgun sequencing are now required to clarify the functional ecology of these fungi.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

LMDS, EAAT, LCC, LHR, MCS, and PEASC conceived the study. LCC and LHR collected the samples. LMDS, EAAT, LHR, and PEASC performed DNA extraction from lake sediments. FACL performed the metabarcoding analysis. LMDS, EAAT, LCC, PEASC, FACL, PC, MCS, and LHR analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study received financial support from CNPq, CAPES, FNDCT, FAPEMIG, FAPT, and PROANTAR. P. Convey is supported by NERC core funding to the British Antarctic Survey’s “Biodiversity, Evolution and Adaptation” Team.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. All raw sequences have been deposited in the NCBI database under the codes SAMN29145234, SAMN29145235, SAMN29145236, SAMN29145237, SAMN29145238, SAMN29145239, SAMN29145240, SAMN29145241, SAMN29145242, and SAMN29145243.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The collections performed in Whalers Bay (Heritage Monument 71) were authorized under permit issued by PROANTAR.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Responsible Editor: Luis Nero

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Blanchette RA, Held BW, Jurgens JA, et al. Wood-destroying soft rot fungi in the historic expedition huts of Antarctica. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1328–1335. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.3.1328-1335.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Held BW, Blanchette RA. Deception Island, Antarctica, harbors a diverse assemblage of wood decay fungi. Fungal Biol. 2017;121:145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosa LH, Zani CL, Cantrell CL et al (2019) Fungi in Antarctica: diversity, ecology, effects of climate change, and bioprospection for bioactive compounds. In: Rosa LH (ed) Fungi of Antarctica: diversity, ecology and biotechnological applications. Springer, Berlin, pp 1–18. 10.1007/978-3-030-18367-7_1

- 4.Hughes KA, Bridge PD. Potential impacts of Antarctic bioprospecting and associated commercial activities upon Antarctic science and scientists. Ethics in Science and Environmental Politics. 2010;10:13–18. doi: 10.3354/esep00106. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosa LH, Pinto OHB, Convey P, et al. DNA metabarcoding to assess the diversity of airborne fungi present over Keller Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica. Microb Ecol. 2021;82:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s00248-020-01627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Held BW, Jurgens JA, Arenz BE, et al. Environmental factors influencing microbial growth inside the historic expedition huts of Ross Island, Antarctica. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2005;55:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ibiod.2004.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arenz BE, Held BW, Jurgens JA, et al. Fungal diversity in soils and historic wood from the Ross Sea Region of Antarctica. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006;38:3057–3064. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duncan SM, Farrell RL, Thwaites JM, et al. Endoglucanase-producing fungi isolated from Cape Evans historic expedition hut on Ross Island, Antarctica. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8:1212–1219. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arenz BE, Blanchette RA. Investigations of fungal diversity in wooden structures and soils at historic sites on the Antarctic Peninsula. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:46–56. doi: 10.1139/W08-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanchette RA, Held BW, Arenz BE. An Antarctic hot spot for fungi at Shackleton’s historic hut on Cape Royds. Microb Ecol. 2010;60:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9664-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arenz BE, Held BW, Jurgens JA, Blanchette RA. Fungal colonization of exotic substrates in Antarctica. Fungal Diversity. 2011;49:13–22. doi: 10.1007/s13225-010-0079-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Menezes GCD, Porto BA, Radicchi GA, et al. Fungal impact on archaeological materials collected at Byers Peninsula Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. An Acad Bras Ciênc. 2022;94:e20210218. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765202220210218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldenberger D, Perschil I, Ritzler M, Altwegg M. A simple “universal” DNA extraction procedure using SDS and proteinase K is compatible with direct PCR amplification. Genome Res. 1995;4:368–370. doi: 10.1101/gr.4.6.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou J, Bruns MA, Tiedje JM. DNA recovery from soils of diverse composition. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:316–322. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.316-322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natarajan M, Nayak BK, Galindo C, et al. Nuclear translocation and DNA-binding activity of NFKB (NF-κB) after exposure of human monocytes to pulsed ultra-wideband electromagnetic fields (1 kV/cm) fails to transactivate κB-dependent gene expression. Radiat Res. 2006;165:645–654. doi: 10.1667/RR3564.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen S, Yao H, Han J, et al. Validation of the ITS2 region as a novel DNA barcode for identifying medicinal plant species. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8613. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson RT, Lin CH, Sponsler DB, et al. Application of ITS2 metabarcoding to determine the provenance of pollen collected by honey bees in an agroecosystem. Applications in Plant Sciences. 2015;3:1400066. doi: 10.3732/apps.1400066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. 1990;18:315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bushnell B (2014) BBMap: a fast, accurate, splice-aware aligner. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. (LBNL), Berkeley, CA (United States). https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap.

- 20.Bolyen E, Rideout JR, Dillon MR, et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37:852–857. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, et al. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bokulich NA, Kaehler BD, Rideout JR, et al. Optimizing taxonomic classification of marker-gene amplicon sequences with QIIME 2’s q2-feature-classifier plugin. Microbiome. 2018;6:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0470-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abarenkov K, Zirk A, Piirmann T (2020) UNITE QIIME release for eukaryotes. Version 04.02.2020. UNITE Community.

- 24.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huson DH, Beier S, Flade I, et al. MEGAN community edition-interactive exploration and analysis of large-scale microbiome sequencing data. PLoS Comput Biol. 2016;12:e1004957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1004957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ondov BD, Bergman NH, Phillippy AM. Interactive metagenomic visualization in a web browser. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:385. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Babicki S, Arndt D, Marcu A, et al. Heatmapper: web-enabled heat mapping for all. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:147–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Medinger R, Nolte V, Pandey RV, et al. Diversity in a hidden world: potential and limitation of next-generation sequencing for surveys of molecular diversity of eukaryotic microorganisms. Mol Ecol. 2010;19:32–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04478.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weber AA, Pawlowski J. Can abundance of protists be inferred from sequence data: a case study of Foraminifera. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giner CR, Forn I, Romac S, et al. Environmental sequencing provides reasonable estimates of the relative abundance of specific picoeukaryotes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2016;82:4757–4766. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00560-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deiner K, Bik HM, Machler E, et al. Environmental DNA metabarcoding: transforming how we survey animal and plant communities. Mol Ecol. 2017;26:5872–5895. doi: 10.1111/mec.14350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hering D, Borja A, Jones JI. Implementation options for DNA-based identification into ecological status assessment under the European Water Framework Directive. Water Res. 2018;138:192–205. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2011) Dictionary of the fungi, 10th ed. CAB International, Wallingford, UK, p. 784.

- 34.Tedersoo L, Sánchez-Ramírez S, Kõljalg U, et al. High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses. Fungal Diversity. 2018;90:135–159. doi: 10.1007/s13225-018-0401-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontology Electronic. 2001;4:9. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen NH, Song Z, Bates ST, et al. FUNGuild: an open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016;20:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2015.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Duncan SM, Farrell RL, Jordan N. Monitoring and identification of airborne fungi at historic locations on Ross Island, Antarctica. Polar Sci. 2010;4:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.polar.2010.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tosi S, Casado B, Gerdol R, Caretta G. Fungi isolated from Antarctic mosses. Polar Biol. 2002;25:262–268. doi: 10.1007/s00300-001-0337-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosa LH, de Sousa JRP, de Menezes GCA, et al. Opportunistic fungi found in fairy rings are present on different moss species in the Antarctic Peninsula. Polar Biol. 2020;43:587–596. doi: 10.1007/s00300-020-02663-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santiago IF, Alves TMA, Rabello A, et al. Leishmanicidal and antitumoral activities of endophytic fungi associated with the Antarctic angiosperms Deschampsia antarctica Desv. and Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. Extremophiles. 2012;16:95–103. doi: 10.1007/s00792-011-0409-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogaki MB, Teixeira DR, Vieira R, et al. Diversity and bioprospecting of cultivable fungal assemblages in sediments of lakes in the Antarctic Peninsula. Extremophiles. 2020;124:601–611. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2020.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Upson R, Newsham KK, Bridge PD. Taxonomic affinities of dark septate root endophytes in the roots of Colobanthus quitensis and Deschampsia antarctica, the two native Antarctic vascular plant species. Fungal Ecol. 2009;2:184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.funeco.2009.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furbino LE, Godinho VM, Santiago IF, et al. Diversity patterns, ecology and biological activities of fungal communities associated with the endemic macroalgae across the Antarctic Peninsula. Microb Ecol. 2014;67:775–787. doi: 10.1007/s00248-014-0374-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cox F, Newsham KK, Bol R, et al. Not poles apart: Antarctic soil fungal communities show similarities to those of the distant Arctic. Ecol Lett. 2016;19:528–536. doi: 10.1111/ele.12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox F, Newsham KK, Robinson CH. Endemic and cosmopolitan fungal taxa exhibit differential abundances in total and active communities of Antarctic soils. Environ Microbiol. 2019;21:1586–1596. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Newsham KK, Cox F, Sands CJ, et al. A previously undescribed Helotialean fungus that is superabundant in soil under maritime Antarctic higher plants. Front Microbiol. 2020;11:615608. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.615608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosa LH, Pinto OHB, Santl-Temkiv T, et al. DNA metabarcoding of fungal diversity in air and snow of Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78630-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosa LH, da Silva TH, Ogaki MB, et al. DNA metabarcoding uncovers fungal diversity in soils of protected and non-protected areas on Deception Island, Antarctica. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78934-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Souza LMD, Ogaki MB, Câmara PEAS, et al. Assessment of fungal diversity present in lakes of Maritime Antarctica using DNA metabarcoding: a temporal microcosm experiment. Extremophiles. 2021;25:77–84. doi: 10.1007/s00792-020-01212-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Menezes GCA, Câmara PEAS, Pinto OHB, et al. Fungal diversity present on rocks from a polar desert in continental Antarctica assessed using DNA metabarcoding. Extremophiles. 2021;25:193–202. doi: 10.1007/s00792-021-01221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Souza LMD, Lirio JM, Coria SH, et al. Diversity, distribution and ecology of fungal community present in Antarctic lake sediments uncovered by DNA metabarcoding. Sci Rep. 2022;12:8407. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12290-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crous PW, Schubert K, Braun U, et al. Opportunistic, human-pathogenic species in the Herpotrichiellaceae are phenotypically similar to saprobic or phytopathogenic species in the Venturiaceae. Stud Mycol. 2007;64:123–133. doi: 10.3114/sim.2007.58.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costa FDF, da Silva NM, Voidaleski MF, et al. Environmental prospecting of black yeast-like agents of human disease using culture-independent methodology. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-70915-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gams W, McGinnis MR. Phialemonium, a new anamorph genus intermediate between Phialophora and Acremonium. Mycologia. 1983;75:977–987. doi: 10.1080/00275514.1983.12023783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Proia LA, Hayden MK, Kammeyer PL, et al. Phialemonium: an emerging mold pathogen that caused 4 cases of hemodialysis-associated endovascular infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:373–379. doi: 10.1086/422320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. All raw sequences have been deposited in the NCBI database under the codes SAMN29145234, SAMN29145235, SAMN29145236, SAMN29145237, SAMN29145238, SAMN29145239, SAMN29145240, SAMN29145241, SAMN29145242, and SAMN29145243.