Abstract

Background:

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the most common metabolic disorder. The aim of the present investigation was to identify gene signature specific to T2DM.

Methods:

The next generation sequencing (NGS) dataset GSE81608 was retrieved from the gene expression omnibus (GEO) database and analyzed to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between T2DM and normal controls. Then, Gene Ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analysis, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, modules, miRNA (micro RNA)-hub gene regulatory network construction and TF (transcription factor)-hub gene regulatory network construction, and topological analysis were performed. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was also performed to verify the prognostic value of hub genes.

Results:

A total of 927 DEGs (461 were up regulated and 466 down regulated genes) were identified in T2DM. GO and REACTOME results showed that DEGs mainly enriched in protein metabolic process, establishment of localization, metabolism of proteins, and metabolism. The top centrality hub genes APP, MYH9, TCTN2, USP7, SYNPO, GRB2, HSP90AB1, UBC, HSPA5, and SQSTM1 were screened out as the critical genes. ROC analysis provides prognostic value of hub genes.

Conclusion:

The potential crucial genes, especially APP, MYH9, TCTN2, USP7, SYNPO, GRB2, HSP90AB1, UBC, HSPA5, and SQSTM1, might be linked with risk of T2DM. Our study provided novel insights of T2DM into genetics, molecular pathogenesis, and novel therapeutic targets.

Keywords: bioinformatics analysis, differentially expressed genes, hub genes, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, pathway enrichment analysis

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a complex metabolic disorder and is characterized primarily by a decrease in insulin secretion, typically accompanied by insulin resistance.1 Globally, it is predicted that 25 million adults (20-79 years) have diabetes, projected to reach 629 million by 2045 and is the ninth leading cause of death.2,3 T2DM is mainly associated with macrovascular complications include stroke, coronary artery disease and peripheral arterial disease, and microvascular complications include diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, and diabetic neuropathy, and non-vascular diabetes complications include nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, psychiatric disease, obesity, cancer, cognitive impairment, infections, and disability.4 There are several important risk factors for T2DM, such as age, sex, family history of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, abdominal obesity, stress in the workplace or home, a sedentary lifestyle, smoking, insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption, physical activity, genetic, and environmental causes.5 Our understanding of the occurrence and development mechanism of T2DM has been greatly improved; however, the cause and potential molecular mechanism of T2DM are still unclear.6 Therefore, it is necessary to identify key genes and pathways for understanding the molecular mechanism and discovering potential biomarkers for T2DM.

In recent decades, more and more researchers have devoted themselves to exploring the potential mechanisms for progression of T2DM. Recent investigation have shown that key biomarkers, such as HHEX, CDKN2A/B, and IGF2BP2,7 CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE,8 ADIPOQ, PPAR-γ, and RXR-α,9 ABCC8 and KCNJ11,10 TCF7L2, SLC30A8, PCSK1, and PCSK211 were involved in the T2DM. Recent studies have shown that signaling pathway, including PI3K/AKT-and AMPK signaling pathway,12 mTOR signaling pathway,13 insulin signaling pathway,14 AGE/RAGE/JNK, STAT3/SCOS3, and RAS signaling pathway,15 and ERK signaling pathway16 were involved in progression of T2DM. Therefore, it is of great practical significance to explore the genes and signaling pathways of T2DM on islet cells.

RNA sequencing technology can rapidly detect gene expression on a global basis and are particularly useful in screening for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in diseases.17 RNA sequencing technology allows the investigation of gene expression in a high throughput manner with high sensitivity, specificity and repeatability. Significant amounts of data have been produced via the use of RNA sequencing and the majority of such data has been uploaded and stored in public databases. Indeed, some researchers found key genes and pathways in T2DM by integrated bioinformatics analysis.18-23 However, the comparative analysis of DEGs across a range of independent investigation might yield only a relatively limited amount of useful data with regard to T2DM advancement. The disadvantages of these single investigations might be overcome by NGS analysis, as this approach would make it possible to analyze the signaling pathways and interaction networks linked with the identified DEGs. This knowledge might help in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying T2DM and its associated complications.

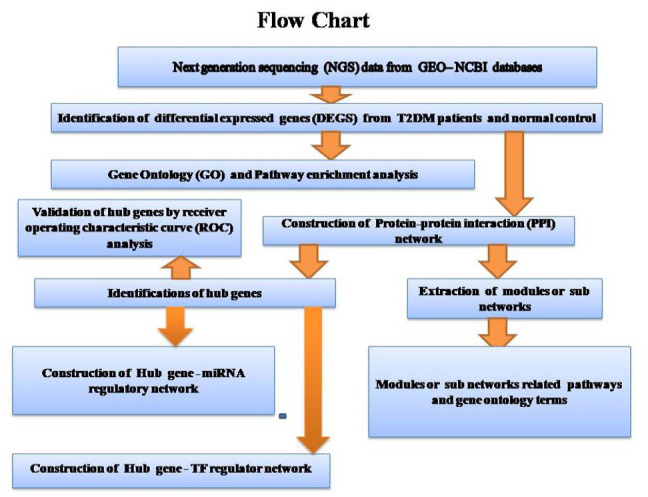

In the present investigation, next generation sequencing (NGS) dataset was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)24: GSE81608.25 DEGs were identified in T2DM. We then carried out gene ontology (GO), REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis, module analysis, miRNA-hub gene regulatory network, and TF-hub gene regulatory network analysis to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanisms. Finally, hub genes were validated by receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC). Collectively, the findings of the present investigation highlighted crucial genes and signaling pathways that might contribute to the pathology of T2DM and associated complications. The research flowchart of this investigation was shown in Figure 1. These may provide a basis for the advancement of future diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic tools for T2DM.

Figure 1.

Research design flow chart.

Materials and Methods

Data resources

NGS dataset GSE8160825 was downloaded from the GEO database. The platform used for NGS data was the GPL16791 Illumina HiSeq 2500 (Homo sapiens). The GSE81608 dataset contained data from 1600 samples, including 949 T2DM samples (single human islet cells), and 651 healthy control samples (single human islet cells).

Identification of DEGs

Limma package in R software26 is a tool to identify DEGs by comparing samples from GEO series. Limma package in R software was used to search for in messenger RNAs (mRNAs; DEGs) that were differentially expressed between T2DM and healthy control samples. The cutoff criteria were an adjusted P-value of <.05, whereas the logFC value were >0.181 for up regulated genes and <−0.27 for down regulated genes. DEG of this dataset was visualized with volcano map and hierarchical clustering heat map. The volcano plot was drawn using ggplot2 package in R software. Hierarchical clustering heat maps of DEG expression (up regulated genes and down regulated genes) were visualized with gplots package in R software.

GO and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

GO enrichment analysis (http://geneontology.org/)27 implements the annotation of biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC) and molecular functions (MF) of DEGs. REACTOME (https://reactome.org/)28 is a database that stores large amounts of data on genomics, biological pathways, signaling pathways, diseases, drugs, and chemicals. The present investigation used Database for g:Profiler (http://biit.cs.ut.ee/gprofiler/)29 to perform GO and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis. P < .05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Construction of the PPI network and module analysis

The IID interactome database (http://iid.ophid.utoronto.ca/) may be searched for associations between known and predicted proteins, and is commonly used to predict PPI information in molecular biology.30 Cytoscape 3.8.2 (http://www.cytoscape.org/)31 was used to visualize the results from the PPI network In this investigation, node degree,32 betweenness centrality,33 stress centrality,34 and closeness centrality,35 which constitutes a fundamental parameter in network theory, was adopted to evaluate the nodes in a network. The node degree betweenness centrality, stress centrality and closeness centrality methods were calculated using Cytoscape plugin Network Analyzer. Module analysis on the PPI network results was performed using the PEWCC136 clustering algorithm that comes with Cytoscape. Module analysis might be used to find out more connected gene groups. In addition, the module analysis were further analyzed for GO and pathway enrichment analysis.

MiRNA-hub gene regulatory network construction

Prediction of miRNA-hub genes was performed by miRNet database (https://www.mirnet.ca/).37 According to the regulatory interaction, miRNA-hub gene regulatory network was constructed based on miRNet by Cytoscape 3.8.2 software.31

TF-hub gene regulatory network construction

Prediction of TF-hub genes was performed by NetworkAnalyst database (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/).38 According to the regulatory interaction, TF-hub gene regulatory network was constructed based on NetworkAnalyst by Cytoscape 3.8.2 software.31

Validation of hub genes by receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis

ROC curve analysis was performed to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the hub genes for T2DM diagnosis using the R package “pROC.”39 An area under the curve (AUC) value was determined and used to label the ROC effect. GEO datasets were used in ROC analysis. AUC > 0.8 indicated that the model had a good fitting effect.40

Results

Identification of DEGs

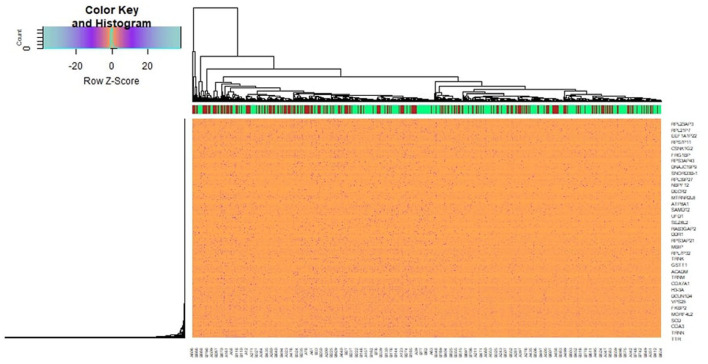

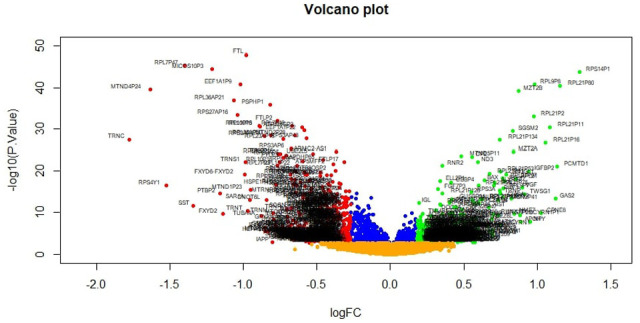

A total of 927 genes were identified to be differentially expressed between T2DM and normal control samples with the threshold of adjusted P-value of <.05, and logFC value were >0.181 for up regulated genes and <−0.27 for down regulated genes. Among these DEGs, 461 were up regulated and 466 down regulated genes in T2DM compared with normal control samples and DEGs are listed in Supplemental Table S1. A heat map (Figure 2) and a volcano plot (Figure 3) for the identified DEGs was generated.

Figure 2.

Heat map of differentially expressed genes. Legend on the top left indicate log fold change of genes. (A1-A651 = normal control samples; B1-B949 = T2DM samples).

Figure 3.

Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes. Genes with a significant change of more than two-fold were selected. Green dot represented up regulated significant genes and red dot represented down regulated significant genes.

GO and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis of DEGs

To identify the pathways which had the most significant involvement with the genes identified, up regulated and down regulated genes were submitted into g:Profiler for GO terms are listed in Supplemental Table S2 and REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis are listed in Supplemental Table S3. GO enrichment analysis revealed that in BP terms, the up regulated genes were mainly enriched in protein metabolic process and positive regulation of biological process. Down regulated genes were mainly enriched in establishment of localization and cellular metabolic process. In CC terms, up regulated genes were mainly enriched in intracellular anatomical structure and endomembrane system, whereas down regulated genes were mainly enriched in cytoplasm and intracellular anatomical structure. In MF terms, up regulated genes were mainly enriched in heterocyclic compound binding and protein binding, whereas down regulated genes were mainly enriched in catalytic activity and protein binding. REACTOME pathway enrichment analysis demonstrated that up regulated genes were significantly enriched in metabolism of proteins, and NR1H3 and NR1H2 regulate gene expression linked to cholesterol transport and efflux. Down regulated genes were significantly enriched in the metabolism and the citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport.

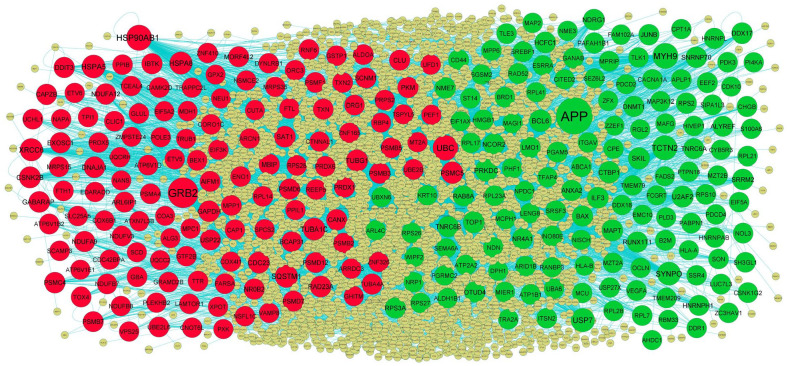

Construction of the PPI network and module analysis

Following the analysis based on the PPI networks, 4424 nodes and 8670 edges were identified in Cytoscape (Figure 4). The genes with higher scores were the hub genes, as the genes of higher node degree, betweenness centrality, stress centrality, and closeness centrality might be linked with T2DM. The top hub genes include APP, MYH9, TCTN2, USP7, SYNPO, GRB2, HSP90AB1, UBC, HSPA5, and SQSTM1, and topological properties of each hub genes in PPI network is given in Table 1. A total of 2 modules were selected through PEWCC1 analysis, and module 1 had nodes 98 and edges 117 (Figure 5A) and module 2 had nodes 81 and edges 248 (Figure 5B). Enrichment analysis demonstrated that modules 1 and 2 might be linked with RNA polymerase II transcription, intracellular anatomical structure, metabolism of proteins, protein metabolic process, positive regulation of biological process, metabolism, immune system, establishment of localization, cytoplasm, neutrophil degranulation, cellular metabolic process, intracellular anatomical structure, and protein binding.

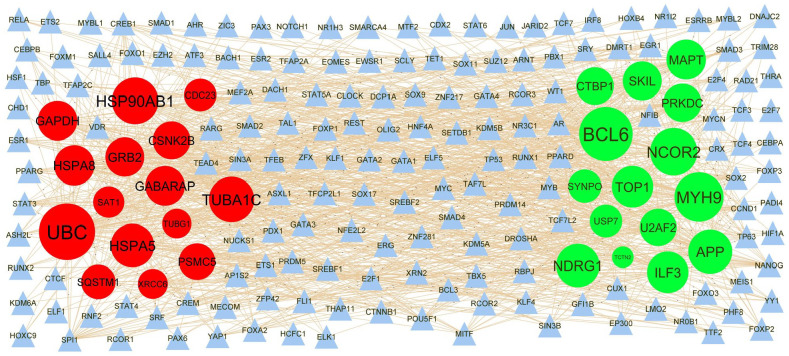

Figure 4.

PPI network of DEGs. The PPI network of DEGs was constructed using Cytoscap. Up regulated genes are marked in green; down regulated genes are marked in red. Big node represents nod with more number of interactions and small node represents nod with least number of interactions.

Table 1.

Topology table for up and down regulated genes.

| Regulation | Node | Degree | Betweenness | Stress | Closeness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up | APP | 674 | 0.277552 | 48 171 576 | 0.396397 |

| Up | MYH9 | 231 | 0.067132 | 12 987 566 | 0.351087 |

| Up | TCTN2 | 203 | 0.074204 | 9 822 804 | 0.31559 |

| Up | USP7 | 156 | 0.048917 | 10 011 292 | 0.341756 |

| Up | SYNPO | 148 | 0.019807 | 5 325 396 | 0.315343 |

| Up | BCL6 | 99 | 0.03129 | 4 924 434 | 0.316788 |

| Up | PRKDC | 97 | 0.02396 | 5 704 444 | 0.339213 |

| Up | U2AF2 | 77 | 0.016653 | 3 792 650 | 0.316448 |

| Up | SKIL | 72 | 0.021529 | 2 766 174 | 0.31763 |

| Up | CTBP1 | 72 | 0.018919 | 3 933 722 | 0.30334 |

| Up | TOP1 | 66 | 0.012706 | 3 485 932 | 0.318522 |

| Up | NDRG1 | 65 | 0.014232 | 2 582 316 | 0.327508 |

| Up | NCOR2 | 62 | 0.014748 | 2 563 224 | 0.327727 |

| Up | ILF3 | 62 | 0.010796 | 3 729 048 | 0.325197 |

| Up | MAPT | 59 | 0.011654 | 2 038 018 | 0.335304 |

| Up | SNRNP70 | 56 | 0.013306 | 2 811 964 | 0.337737 |

| Up | NME7 | 54 | 0.009971 | 2 818 468 | 0.302345 |

| Up | HCFC1 | 54 | 0.011189 | 4 114 590 | 0.285724 |

| Up | SRRM2 | 53 | 0.008517 | 2 842 260 | 0.304719 |

| Up | DDX17 | 48 | 0.010257 | 2 309 956 | 0.34835 |

| Up | RUNX1T1 | 45 | 0.007377 | 1 300 474 | 0.298327 |

| Up | TNRC6B | 44 | 0.005765 | 1 772 074 | 0.294513 |

| Up | RPS3A | 43 | 0.008663 | 1 580 346 | 0.314044 |

| Up | BAX | 43 | 0.010013 | 1 360 956 | 0.305287 |

| Up | ANXA2 | 42 | 0.006725 | 1 415 220 | 0.32746 |

| Up | RAB8A | 38 | 0.009675 | 2 880 488 | 0.28541 |

| Up | ALYREF | 37 | 0.006723 | 3 260 410 | 0.299114 |

| Up | OTUD4 | 36 | 0.009901 | 1 095 992 | 0.306175 |

| Up | TNRC6A | 36 | 0.006285 | 1 066 772 | 0.298629 |

| Up | LMO1 | 36 | 0.007004 | 1 983 992 | 0.281738 |

| Up | NR4A1 | 35 | 0.007386 | 1 366 096 | 0.293516 |

| Up | DNMT1 | 35 | 0.007153 | 1 311 716 | 0.318247 |

| Up | JUNB | 34 | 0.007201 | 2 171 380 | 0.289501 |

| Up | HNRNPH1 | 34 | 0.004039 | 1 126 254 | 0.310822 |

| Up | HNRNPL | 33 | 0.002406 | 639 204 | 0.306684 |

| Up | EEF2 | 32 | 0.00508 | 1 312 314 | 0.31811 |

| Up | RPS2 | 32 | 0.005007 | 944 774 | 0.30743 |

| Up | PGAM5 | 32 | 0.004601 | 1 343 578 | 0.295695 |

| Up | CD44 | 31 | 0.005854 | 812 632 | 0.311523 |

| Up | B2M | 31 | 0.005781 | 1 559 068 | 0.265885 |

| Up | RAD52 | 30 | 0.004293 | 852 988 | 0.296289 |

| Up | ATP2A2 | 30 | 0.007054 | 1 516 120 | 0.312823 |

| Up | SREBF1 | 30 | 0.007025 | 2 186 330 | 0.278526 |

| Up | PAFAH1B1 | 29 | 0.005215 | 2 372 866 | 0.276438 |

| Up | NDN | 29 | 0.007043 | 1 329 464 | 0.296547 |

| Up | SRSF3 | 28 | 0.003437 | 1 013 722 | 0.303174 |

| Up | APLP1 | 27 | 0.006221 | 892 288 | 0.276818 |

| Up | GANAB | 27 | 0.004094 | 990 330 | 0.298347 |

| Up | RPL7 | 26 | 0.003381 | 933 236 | 0.310757 |

| Up | MPRIP | 26 | 0.001472 | 342 632 | 0.295873 |

| Up | INO80E | 25 | 0.005901 | 1 721 260 | 0.272453 |

| Up | CACNA1A | 24 | 0.010596 | 1 171 628 | 0.281863 |

| Up | CHGB | 24 | 0.006952 | 765 394 | 0.299337 |

| Up | RPL28 | 24 | 0.002372 | 585 818 | 0.299074 |

| Up | ITSN2 | 24 | 0.003281 | 939 596 | 0.286093 |

| Up | RPS10 | 23 | 0.004922 | 897 446 | 0.326132 |

| Up | RPL23A | 23 | 0.003289 | 505 840 | 0.311962 |

| Up | PHF1 | 22 | 0.003983 | 1 034 682 | 0.277426 |

| Up | HNRNPAB | 22 | 0.001844 | 495 324 | 0.3108 |

| Up | SH3GL1 | 22 | 0.003033 | 986 094 | 0.270008 |

| Up | HMGB1 | 21 | 0.002117 | 776 702 | 0.290681 |

| Up | PDK3 | 19 | 0.002946 | 742 934 | 0.275937 |

| Up | ARID1B | 19 | 0.004 | 716 712 | 0.264217 |

| Up | ABCA1 | 18 | 0.003966 | 549 762 | 0.275216 |

| Up | ESRRA | 18 | 0.002502 | 368 532 | 0.276023 |

| Up | TRA2A | 18 | 0.001473 | 605 004 | 0.285005 |

| Up | MAGI1 | 18 | 0.00426 | 637 328 | 0.277722 |

| Up | VEGFA | 17 | 0.004134 | 836 256 | 0.248525 |

| Up | ZC3HAV1 | 17 | 0.001292 | 489 318 | 0.274227 |

| Up | HIVEP1 | 16 | 0.001767 | 378 796 | 0.2718 |

| Up | SIPA1L3 | 16 | 0.001056 | 218 866 | 0.285465 |

| Up | MPP6 | 16 | 0.002628 | 324 224 | 0.275972 |

| Up | RPL17 | 16 | 0.001736 | 515 376 | 0.297165 |

| Up | SSR4 | 16 | 0.001986 | 441 016 | 0.283617 |

| Up | RPS27 | 15 | 0.002603 | 522 416 | 0.297905 |

| Up | SON | 15 | 4.63E-04 | 263 370 | 0.282512 |

| Up | PDCD4 | 15 | 0.001508 | 323 916 | 0.276732 |

| Up | TMEM79 | 15 | 0.004325 | 604 778 | 0.229337 |

| Up | MAFG | 14 | 0.002447 | 382 134 | 0.252123 |

| Up | SGSM2 | 14 | 0.002229 | 327 358 | 0.278544 |

| Up | NOL3 | 14 | 6.71E-04 | 214 960 | 0.264091 |

| Up | S100A6 | 14 | 9.74E-04 | 248 722 | 0.280861 |

| Up | MZT2A | 14 | 2.68E-04 | 75 218 | 0.276801 |

| Up | RPL21 | 14 | 0.001091 | 579 282 | 0.289843 |

| Up | MCPH1 | 14 | 8.71E-04 | 244 188 | 0.255857 |

| Up | LUC7L3 | 13 | 0.001174 | 368 838 | 0.272386 |

| Up | DDX18 | 13 | 0.001648 | 394 268 | 0.31722 |

| Up | TLE3 | 13 | 0.002428 | 330 598 | 0.309193 |

| Up | EIF5A | 13 | 0.002018 | 470 016 | 0.279742 |

| Up | LENG8 | 13 | 0.001599 | 412 736 | 0.24473 |

| Up | OCLN | 12 | 0.001253 | 314 884 | 0.263462 |

| Up | PABPN1 | 12 | 0.001338 | 370 074 | 0.285705 |

| Up | BRD1 | 11 | 0.001735 | 432 360 | 0.250156 |

| Up | KRT10 | 11 | 5.29E-04 | 212 650 | 0.28389 |

| Up | RPS26 | 11 | 6.46E-04 | 207 408 | 0.291102 |

| Up | TMEM209 | 11 | 0.002671 | 362 732 | 0.281917 |

| Up | TLK1 | 11 | 0.001007 | 270 716 | 0.252627 |

| Up | NPDC1 | 11 | 7.46E-04 | 230 746 | 0.250595 |

| Up | ST14 | 11 | 0.001157 | 228 876 | 0.261871 |

| Up | UBA6 | 10 | 0.00209 | 401 360 | 0.269055 |

| Up | MAP3K12 | 10 | 0.00226 | 336 206 | 0.272201 |

| Up | MAP2 | 10 | 0.001373 | 254 464 | 0.319327 |

| Up | ITGAV | 10 | 0.00199 | 532 090 | 0.270371 |

| Up | CPE | 10 | 0.001881 | 615 956 | 0.227778 |

| Up | TFAP4 | 10 | 7.77E-04 | 213 056 | 0.26184 |

| Up | MIER1 | 10 | 0.0015 | 272 476 | 0.264123 |

| Up | CPT1A | 9 | 5.45E-04 | 93 620 | 0.276438 |

| Up | RGL2 | 9 | 6.06E-04 | 170 470 | 0.251865 |

| Up | CYB5R3 | 9 | 9.29E-04 | 184 034 | 0.256748 |

| Up | DDR1 | 9 | 0.001327 | 189 372 | 0.266558 |

| Up | ATP1B1 | 9 | 0.001955 | 400 240 | 0.267073 |

| Up | NME3 | 9 | 0.001643 | 194 338 | 0.301808 |

| Up | MZT2B | 9 | 1.10E-04 | 28 768 | 0.258413 |

| Up | ALDH1B1 | 9 | 9.67E-04 | 319 144 | 0.277583 |

| Up | PI4KA | 9 | 7.40E-04 | 268 444 | 0.277879 |

| Up | CSNK1G2 | 9 | 0.001421 | 396 030 | 0.252931 |

| Up | CITED2 | 9 | 0.002327 | 530 770 | 0.263431 |

| Up | RANBP3 | 9 | 0.001499 | 304 686 | 0.236853 |

| Up | NRP1 | 8 | 8.45E-04 | 148 358 | 0.258398 |

| Up | PGRMC2 | 8 | 4.66E-04 | 87 082 | 0.262275 |

| Up | HLA-B | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0.210049 |

| Up | HLA-A | 4 | 7.39E-05 | 16 916 | 0.249408 |

| Up | EIF1AX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.28389 |

| Up | ARL4C | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.28389 |

| Up | RPL41 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.28389 |

| Up | UBXN6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.28389 |

| Up | CDK10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.267235 |

| Up | DPH1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.266639 |

| Up | AHDC1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.259871 |

| Up | SEZ6L2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.191166 |

| Up | PDCD2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.222239 |

| Up | PTPN18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.285576 |

| Up | NISCH | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.285576 |

| Up | RBM33 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.285576 |

| Up | WIPF2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.285576 |

| Up | MCU | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.225479 |

| Up | ZZEF1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.241075 |

| Up | FCGRT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.210049 |

| Up | EMC10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.239898 |

| Up | PLD3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.239898 |

| Up | FADS2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.239898 |

| Up | FAM102A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.212614 |

| Up | SEMA6A | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.222463 |

| Up | ZFX | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.232008 |

| Up | USP27X | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.21869 |

| Down | GRB2 | 431 | 0.172947 | 23 419 584 | 0.399693 |

| Down | HSP90AB1 | 225 | 0.07414 | 15 655 320 | 0.364663 |

| Down | UBC | 224 | 0.075316 | 15 138 294 | 0.356148 |

| Down | HSPA5 | 144 | 0.05737 | 10 318 564 | 0.363554 |

| Down | SQSTM1 | 123 | 0.036494 | 6 909 982 | 0.339317 |

| Down | XRCC6 | 121 | 0.034438 | 8 751 842 | 0.335228 |

| Down | HSPA8 | 120 | 0.03154 | 6 567 910 | 0.365537 |

| Down | TUBA1C | 91 | 0.023847 | 3 670 590 | 0.328896 |

| Down | TUBG1 | 81 | 0.017666 | 3 231 832 | 0.324267 |

| Down | PSMC5 | 80 | 0.015146 | 3 450 624 | 0.332456 |

| Down | CSNK2B | 77 | 0.019998 | 5 358 078 | 0.32002 |

| Down | CDC23 | 75 | 0.021091 | 6 346 650 | 0.302076 |

| Down | SAT1 | 69 | 0.01963 | 4 672 960 | 0.296746 |

| Down | GAPDH | 63 | 0.012495 | 2 722 934 | 0.342046 |

| Down | GABARAP | 62 | 0.01438 | 2 298 584 | 0.299175 |

| Down | RAD23A | 56 | 0.009202 | 1 854 168 | 0.312778 |

| Down | PKM | 51 | 0.009281 | 2 445 062 | 0.320972 |

| Down | DNAJA1 | 51 | 0.008274 | 2 322 170 | 0.320763 |

| Down | PSMB3 | 50 | 0.005865 | 1 322 226 | 0.308051 |

| Down | EXOSC1 | 50 | 0.01119 | 2 195 338 | 0.294709 |

| Down | DDIT3 | 48 | 0.01172 | 2 529 152 | 0.297345 |

| Down | NDUFA9 | 47 | 0.013121 | 3 147 348 | 0.291102 |

| Down | CANX | 46 | 0.01141 | 2 049 224 | 0.314089 |

| Down | IBTK | 45 | 0.008641 | 1 736 696 | 0.290891 |

| Down | SCNM1 | 45 | 0.006692 | 2 252 600 | 0.281594 |

| Down | PSMC4 | 42 | 0.003699 | 829 472 | 0.31331 |

| Down | NDUFA12 | 42 | 0.004926 | 813 880 | 0.250837 |

| Down | MBIP | 42 | 0.01045 | 2 311 340 | 0.274601 |

| Down | PSMD7 | 41 | 0.002834 | 722 504 | 0.302179 |

| Down | USP22 | 41 | 0.011629 | 3 407 576 | 0.279884 |

| Down | PSMD6 | 40 | 0.001629 | 559 916 | 0.281863 |

| Down | CLU | 40 | 0.00841 | 1 216 580 | 0.309431 |

| Down | AIFM1 | 39 | 0.005419 | 1 729 814 | 0.299966 |

| Down | MORF4L2 | 39 | 0.011082 | 2 538 970 | 0.275662 |

| Down | PRDX1 | 38 | 0.005407 | 1 341 464 | 0.312403 |

| Down | ARL6IP1 | 37 | 0.012555 | 1 641 598 | 0.244635 |

| Down | CAPZB | 36 | 0.004358 | 1 050 292 | 0.311742 |

| Down | PSMD12 | 34 | 0.001447 | 422 448 | 0.305161 |

| Down | PSMB7 | 34 | 0.001154 | 364 868 | 0.289577 |

| Down | BCAP31 | 34 | 0.013785 | 1 768 344 | 0.327824 |

| Down | PSMB5 | 34 | 0.003403 | 666 674 | 0.313199 |

| Down | NR0B2 | 34 | 0.005798 | 1 517 314 | 0.302138 |

| Down | TUBA4A | 33 | 0.005178 | 1 530 624 | 0.307217 |

| Down | RNF6 | 33 | 0.003643 | 1 333 208 | 0.262166 |

| Down | MPP1 | 32 | 0.007264 | 815 422 | 0.302924 |

| Down | CAMK2D | 32 | 0.008412 | 1 997 208 | 0.289805 |

| Down | PSMF1 | 32 | 0.006012 | 1 557 236 | 0.280594 |

| Down | ALDOA | 31 | 0.004458 | 960 392 | 0.311391 |

| Down | PSMA4 | 30 | 0.002283 | 522 348 | 0.297505 |

| Down | PSMB2 | 30 | 0.003431 | 769 210 | 0.296309 |

| Down | UCHL1 | 28 | 0.00501 | 791 348 | 0.328067 |

| Down | TXN2 | 28 | 0.00596 | 1 364 924 | 0.272084 |

| Down | ORC3 | 28 | 0.005692 | 1 623 144 | 0.284273 |

| Down | CLIC1 | 27 | 0.004327 | 824 568 | 0.304447 |

| Down | UBE2L6 | 27 | 0.006391 | 1 958 890 | 0.274499 |

| Down | GBA | 26 | 0.004796 | 875 116 | 0.282061 |

| Down | ENO1 | 26 | 0.00367 | 1 143 078 | 0.306876 |

| Down | RPL14 | 26 | 0.004161 | 1 610 674 | 0.298569 |

| Down | FTH1 | 24 | 0.004084 | 777 832 | 0.276783 |

| Down | TXN | 24 | 0.003003 | 482 510 | 0.302717 |

| Down | GSTP1 | 24 | 0.004232 | 1 080 546 | 0.295201 |

| Down | REEP5 | 24 | 0.005234 | 1 041 918 | 0.267817 |

| Down | TOX4 | 23 | 0.005025 | 1 370 332 | 0.276058 |

| Down | TTR | 23 | 0.003317 | 617 718 | 0.272823 |

| Down | CORO1C | 23 | 0.001258 | 341 072 | 0.296269 |

| Down | GTF2B | 22 | 0.004837 | 1 919 700 | 0.246228 |

| Down | PPIB | 21 | 0.002633 | 702 460 | 0.286557 |

| Down | UFD1 | 20 | 0.00202 | 299 278 | 0.298952 |

| Down | GLUL | 20 | 0.003636 | 572 524 | 0.266767 |

| Down | SCAMP3 | 19 | 0.002153 | 497 590 | 0.274738 |

| Down | FTL | 19 | 0.004867 | 440 140 | 0.298006 |

| Down | SLC25A5 | 19 | 0.001986 | 352 068 | 0.310844 |

| Down | UBE2B | 19 | 0.002118 | 572 844 | 0.260713 |

| Down | ZNF326 | 19 | 0.002394 | 916 478 | 0.295359 |

| Down | LAMTOR1 | 19 | 0.004398 | 814 628 | 0.252454 |

| Down | ZNF410 | 18 | 0.004751 | 566 192 | 0.302386 |

| Down | PRDX6 | 18 | 0.002313 | 594 114 | 0.280327 |

| Down | DRG1 | 18 | 0.002816 | 810 156 | 0.295122 |

| Down | ATP6V1B2 | 18 | 0.002914 | 816 976 | 0.270388 |

| Down | ZNF165 | 18 | 0.003519 | 739 876 | 0.262493 |

| Down | NDUFV3 | 18 | 0.001755 | 335 550 | 0.259292 |

| Down | EIF3K | 18 | 0.004959 | 1 105 612 | 0.27343 |

| Down | NSFL1C | 17 | 0.003491 | 339 954 | 0.287189 |

| Down | ARCN1 | 17 | 0.002733 | 778 374 | 0.290204 |

| Down | TPI1 | 17 | 0.001365 | 553 820 | 0.293848 |

| Down | ARRDC3 | 17 | 0.001321 | 468 292 | 0.265518 |

| Down | NDUFB8 | 16 | 0.001576 | 271 076 | 0.25175 |

| Down | PRDX5 | 15 | 0.00314 | 356 484 | 0.304824 |

| Down | RPS28 | 15 | 0.00171 | 509 708 | 0.276317 |

| Down | TCEAL4 | 15 | 0.002744 | 249 400 | 0.281451 |

| Down | VAMP8 | 15 | 0.003131 | 687 744 | 0.270437 |

| Down | TRAPPC2L | 14 | 0.004206 | 559 988 | 0.293516 |

| Down | CNOT6L | 14 | 0.002421 | 339 456 | 0.257721 |

| Down | ATP6V1D | 14 | 0.002838 | 320 770 | 0.28589 |

| Down | DYNLRB1 | 14 | 0.001865 | 358 956 | 0.26184 |

| Down | EDARADD | 13 | 0.001601 | 322 314 | 0.258051 |

| Down | PEF1 | 13 | 0.001577 | 414 800 | 0.268957 |

| Down | FARSA | 13 | 0.001697 | 508 804 | 0.2652 |

| Down | POLE3 | 12 | 0.004074 | 517 276 | 0.286019 |

| Down | COX4I1 | 12 | 0.002449 | 321 508 | 0.261561 |

| Down | ETV5 | 12 | 0.003438 | 1 053 244 | 0.236334 |

| Down | NAPA | 12 | 0.002141 | 556 788 | 0.283217 |

| Down | VPS25 | 12 | 0.002068 | 519 502 | 0.245014 |

| Down | BEX1 | 12 | 0.001246 | 267 736 | 0.267979 |

| Down | XPOT | 11 | 0.001347 | 381 778 | 0.281774 |

| Down | MT2A | 11 | 0.001882 | 359 724 | 0.241562 |

| Down | NDUFB7 | 11 | 0.001 | 155 788 | 0.238231 |

| Down | MRPS35 | 11 | 0.00194 | 415 706 | 0.264107 |

| Down | MRPS15 | 11 | 0.001587 | 179 036 | 0.276058 |

| Down | PLEKHB2 | 11 | 0.001437 | 374 900 | 0.236057 |

| Down | NSMCE2 | 11 | 0.001999 | 798 156 | 0.237464 |

| Down | CTNNAL1 | 11 | 0.001959 | 302 074 | 0.253119 |

| Down | PPIL1 | 11 | 0.001172 | 393 624 | 0.278019 |

| Down | PRPS2 | 10 | 0.001596 | 384 080 | 0.259383 |

| Down | COX6B1 | 10 | 5.69E-04 | 148 866 | 0.236765 |

| Down | ETV6 | 10 | 0.002363 | 207 722 | 0.296408 |

| Down | CAP1 | 10 | 5.76E-04 | 164 992 | 0.273972 |

| Down | SPCS2 | 10 | 0.001427 | 294 448 | 0.282801 |

| Down | GRAMD2B | 10 | 0.002536 | 387 376 | 0.231425 |

| Down | CDC42BPA | 10 | 0.001848 | 460 620 | 0.252858 |

| Down | ATP6V1E1 | 2 | 1.68E-05 | 7358 | 0.256421 |

| Down | MPC1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.230293 |

| Down | TRUB1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.28389 |

| Down | NANS | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.267235 |

| Down | MDH1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.267235 |

| Down | GHITM | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.266639 |

| Down | COA3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.207341 |

| Down | NEU1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.224518 |

| Down | UQCC2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.285576 |

| Down | RBP4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.214355 |

| Down | CUTA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.226925 |

| Down | GPX2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.228591 |

| Down | PXK | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.230257 |

| Down | TSPYL5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.254722 |

| Down | ALG3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.239898 |

| Down | ZMPSTE24 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.239898 |

| Down | SCD | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.239898 |

| Down | UQCRH | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.200544 |

| Down | EIF5A2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.232008 |

| Down | ATXN7L3B | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.21869 |

Figure 5.

Modules of isolated form PPI of DEGs: (A) the most significant module was obtained from PPI network with 98 nodes and 117 edges for up regulated genes and (B) the most significant module was obtained from PPI network with 81 nodes and 248 edges for down regulated genes. Up regulated genes are marked in green; down regulated genes are marked in red.

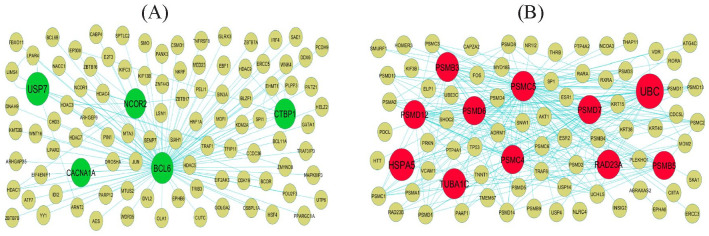

MiRNA-hub gene regulatory network construction

The hub genes of the DEGs in T2DM were performed by online databases miRNet. Based on the miRNAs, a miRNA-hub gene regulatory network was constructed with 2630 nodes (miRNA: 2345 and hub gene: 285) and 20 765 interaction pairs (Figure 6). PRKDC was the gene targets of 163 miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-142-5p), MYH9 was the gene targets of 126 miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-181b-3p), APP was the gene targets of 125 miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-216b-5p), ILF3 was the gene targets of 107 miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-3157-3p), SKIL was the gene targets 91 of miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-1294), HSPA8 was the gene targets of 116 of miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-3661), HSP90AB1 was the gene targets of 103 of miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-200a-3p), SQSTM1 was the gene targets of 94 of miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-520d-5p), HSPA5 was the gene targets of 88 of miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-573), and GRB2 was the gene targets of 65 of miRNAs (eg, hsa-mir-1291), and topological properties of each hub genes and miRNAs in miRNA-hub gene regulatory network are listed in Table 2.

Figure 6.

MiRNA-hub gene regulatory network. The purple color diamond nodes represent the key miRNAs; up regulated genes are marked in green; down regulated genes are marked in orange.

Table 2.

miRNA-target gene and TF-target gene interaction.

| Regulation | Target genes | Degree | MicroRNA | Regulation | Target genes | Degree | TF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up | PRKDC | 163 | hsa-mir-142-5p | Up | BCL6 | 60 | NOTCH1 |

| Up | MYH9 | 126 | hsa-mir-181b-3p | Up | MYH9 | 53 | PPARD |

| Up | APP | 125 | hsa-mir-216b-5p | Up | NCOR2 | 50 | HIF1A |

| Up | ILF3 | 107 | hsa-mir-3157-3p | Up | APP | 45 | SMARCA4 |

| Up | SKIL | 91 | hsa-mir-1294 | Up | NDRG1 | 44 | SUZ12 |

| Up | NCOR2 | 81 | hsa-mir-4708-3p | Up | TOP1 | 41 | CREM |

| Up | U2AF2 | 65 | hsa-mir-196a-5p | Up | ILF3 | 41 | DACH1 |

| Up | NDRG1 | 60 | hsa-mir-374a-5p | Up | MAPT | 38 | YAP1 |

| Up | TOP1 | 45 | hsa-mir-424-5p | Up | SKIL | 37 | GATA2 |

| Up | CTBP1 | 45 | hsa-mir-944 | Up | PRKDC | 36 | NUCKS1 |

| Up | BCL6 | 35 | hsa-mir-4701-3p | Up | CTBP1 | 35 | ELF1 |

| Up | USP7 | 34 | hsa-mir-93-5p | Up | U2AF2 | 34 | KDM6A |

| Up | MAPT | 23 | hsa-mir-2278 | Up | SYNPO | 28 | SMAD4 |

| Up | SYNPO | 15 | hsa-mir-138-5p | Up | USP7 | 27 | NANOG |

| Up | TCTN2 | 9 | hsa-mir-34a-5p | Up | TCTN2 | 10 | SRF |

| Down | HSPA8 | 116 | hsa-mir-3661 | Down | UBC | 64 | TAF7L |

| Down | HSP90AB1 | 103 | hsa-mir-200a-3p | Down | HSP90AB1 | 49 | RUNX2 |

| Down | SQSTM1 | 94 | hsa-mir-520d-5p | Down | TUBA1C | 47 | MITF |

| Down | HSPA5 | 88 | hsa-mir-573 | Down | HSPA5 | 44 | YAP1 |

| Down | GRB2 | 65 | hsa-mir-1291 | Down | HSPA8 | 39 | E2F1 |

| Down | SAT1 | 56 | hsa-mir-301b-3p | Down | GAPDH | 38 | SOX11 |

| Down | UBC | 55 | hsa-mir-9-5p | Down | GABARAP | 38 | HOXB4 |

| Down | GAPDH | 54 | hsa-mir-5690 | Down | GRB2 | 37 | TFAP2A |

| Down | TUBA1C | 53 | hsa-mir-603 | Down | CSNK2B | 35 | THAP11 |

| Down | CDC23 | 51 | hsa-mir-376a-5p | Down | PSMC5 | 33 | STAT4 |

| Down | TUBG1 | 32 | hsa-mir-182-5p | Down | SQSTM1 | 30 | EP300 |

| Down | XRCC6 | 31 | hsa-mir-618 | Down | CDC23 | 27 | TEAD4 |

| Down | GABARAP | 26 | hsa-mir-34b-3p | Down | SAT1 | 25 | SALL4 |

| Down | PSMC5 | 10 | hsa-mir-452-5p | Down | XRCC6 | 23 | YY1 |

| Down | CSNK2B | 9 | hsa-mir-149-3p | Down | TUBG1 | 22 | SOX2 |

TF-hub gene regulatory network construction

The hub genes of the DEGs in T2DM were performed by online databases NetworkAnalyst. Based on the TFs, a TF-hub gene regulatory network was constructed with 477 nodes (TF: 192 and hub gene: 285) and 8507 interaction pairs (Figure 7). BCL6 was the gene targets of 60 TFs (eg, NOTCH1), MYH9 was the gene targets of 53 TFs (eg, PPARD), NCOR2 was the gene targets of 50 TFs (eg, HIF1A), APP was the gene targets of 45 TFs (eg, SMARCA4), NDRG1 was the gene targets of 44 TFs (eg, SUZ12), UBC was the gene targets of 64 TFs (eg, TAF7L), HSP90AB1 was the gene targets of 49 TFs (eg, RUNX2), TUBA1C was the gene targets of 47 TFs (eg, MITF), HSPA5 was the gene targets of 44 TFs (eg, YAP1), and HSPA8 was the gene targets of 39 TFs (eg, E2F1), and topological properties of each hub genes and TFs in TF-hub gene regulatory network are listed in Table 2.

Figure 7.

TF-hub gene regulatory network. The blue color triangle nodes represent the key TFs; up regulated genes are marked in green; down regulated genes are marked in red.

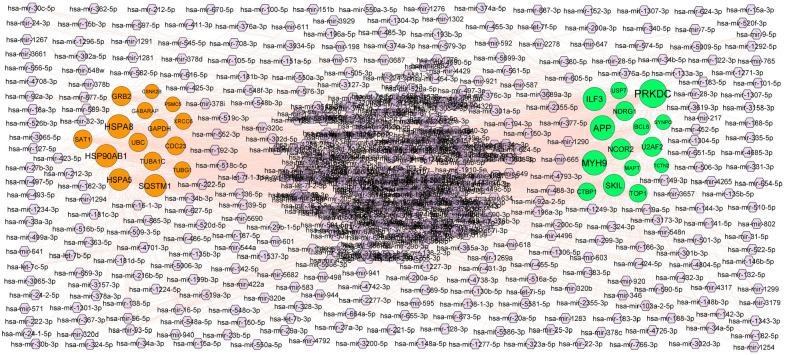

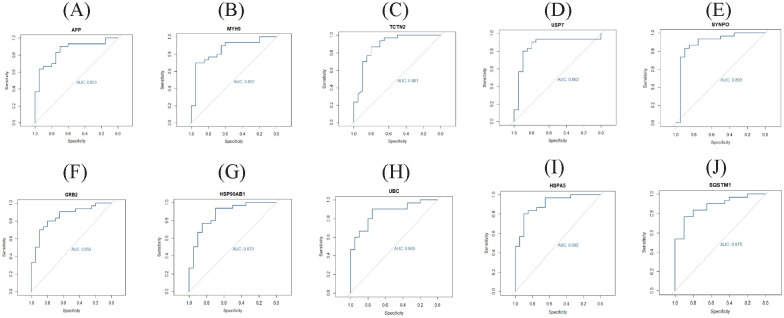

Validation of hub genes by receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis

Validated by ROC curves, we found that 10 hub genes had high sensitivity and specificity, including APP (AUC = 0.853), MYH9 (AUC = 0.852), TCTN2 (AUC = 0.881), USP7 (AUC = 0.862), SYNPO (AUC = 0.893), GRB2 (AUC = 0.850), HSP90AB1 (AUC = 0.870), UBC (AUC = 0.865), HSPA5 (AUC = 0.902), and SQSTM1 (AUC = 0.875) (Figure 8). The hub genes might be biomarkers of T2DM and have positive implications for early medical intervention of the disease.

Figure 8.

ROC curve validated the sensitivity, specificity of hub genes as a predictive biomarker for T2DM: (A) APP, (B) MYH9, (C) TCTN2, (D) USP7, (E) SYNPO, (F) GRB2, (G) HSP90AB1, (H) UBC, (I) HSPA5, and (J) SQSTM1.

Discussion

Although there are various investigations on T2DM that have been conducted, the mortality of T2DM is still high. This might be due to the lack of valid biomarkers for detection of early stage T2DM and of valid treatment for T2DM. Therefore, molecular mechanisms of T2DM are necessary for scientists to find the treat and diagnosis method of T2DM. Because of the fast advancement of NGS technology, it is more convenient to find out the genetic modification of development of diseases. NGS facilitates us to examine the gene, the genetic modification in T2DM, which had been proved to be a better approach to find novel biomarkers in other metabolic diseases.

In the present investigation, we observed whether there were more beneficial genes which could be better biomarkers for the diagnosis, prognosis and therapeutic for T2DM. In order to find out the significant gene of T2DM, we analyzed the NGS data GSE81608 in Limma, where a total number of 927 DEGs were obtained between T2DM and normal control, comprising was 461 up regulated and 466 down regulated genes. CTBP141 and TRNC42 are involved in the pathogenesis of T2DM. A previous study has demonstrated that SST (somatostatin) serves an essential role in obesity.43 Therefore, the data suggest that the identified DEGs might participant in the development of T2DM and associated complications and contribute to T2DM treatment.

Then, databases including GO and REACTOME were selected to do gene enrichment analysis. Metabolism of proteins,44 metabolism,45 the citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport,46 gluconeogenesis,47 immune system,48 heterocyclic compound binding,49 protein binding,50 establishment of localization,51 cellular metabolic process,52 cytoplasm,53 and catalytic activity54 were the GO terms and signaling pathways responsible for the advancement of T2DM. A previous study showed that IGFBP2,55 APOH (apolipoprotein H),56 ANXA2,57 BAX (BCL2 associated X, apoptosis regulator),58 PCSK1N,59 PDK4,60 CPE (carboxypeptidase E),61 OCLN (occludin),62 CD44,63 NDN (necdin, MAGE family member),64 MLXIPL (MLX interacting protein like),65 CD36,66 SREBF1,67 NR4A1,68 PCSK2,69 CHGB (chromogranin B),70 PDK3,71 PDCD4,72 EIF5A,73 NRP1,74 ABCA1,75 DNMT1,76 MYH9,77 HMGB1,78 B4GALT5,79 B2M,80 MAP3K12,81 KSR2,82 NPY (neuropeptide Y),83 CHGA (chromogranin A),84 CD47,85 DLK1,86 PDK4,87 CPE (carboxypeptidase E),61 OCLN (occludin),62 CXXC4,88 PEMT (phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase),89 FADS2,90 RREB1,91 HNRNPAB (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A/B),92 CPT1A,93 ALDH1B1, 94 ESRRA (estrogen related receptor alpha),95 NISCH (nischarin),96 SSTR3,97 ND1,98 NCOR2,99 RBP4,100 GSTP1,101 CYB5A,102 G6PC2,103 DNAJC15,104 TMED6,105 PSMD6,106 CLU (clusterin),107 TTR (transthyretin),108 TXN (thioredoxin),109 LAMTOR1,110 GLUL (glutamate-ammonia ligase),111 NEU1,112 HSPA8,113 AP3S2,114 COX4I1,115 MT2A116 MTCH2,117 ESD (esterase D),118 UBE2L6,119 SCD (stearoyl-CoA desaturase),120 MGST3,121 NQO1,122 NSMCE2,123 and PRSS1124 played an important role in T2DM. Quintela et al,125 Yuan et al,126 Cacace et al,127 Hao et al,128 Beckelman et al,129 Liu et al,130 Sekiguchi et al,131 Castillon et al,132 O’Donnell-Luria et al,133 Coupland et al,134 Koufaris et al,135 Qvist et al,136 Richter et al,137 Torres et al,138 Jeong et al,139 Bermejo-Bescós et al,140 Ramon-Duaso et al,141 Guilarte,142 Mukaetova-Ladinska et al,143 Fazeli et al,144 Butler et al,145 Nackenoff et al,146 Konyukh et al,147 Hu et al,148 Kaur et al,149 Nakamura et al,150 Liu et al,151 Obara et al,152 Herrmann et al,153 Ozgen et al,154 Masciullo et al,155 Perrone et al,156 Su et al,157 Zhao et al,158 Iqbal et al,159 Gal et al,160 Wang et al,161 Stefanović et al,162 Zahola et al,163 Bik-Multanowski et al,164 Mata et al,165 Li et al,166 Payton et al,167 and Chai et al168 indicated that UBA6, TIA1, DPP6, USP7, EEF2, ITM2B, DPH1, PAK3, KMT2E, MAPT (microtubule associated protein tau), HCFC1, BRD1, TAOK2, PHF1, STMN2, APP (amyloid beta precursor protein), MBNL2, APLP1, MAP2, SRRM2 CST3, SRRM2, CST3, PLD3, SEZ6L2, DOC2A, PI4KA, GNAO1, TRA2A, MIDN (midnolin), HOOK3, MCPH1, SACS (sacsin molecular chaperone), TUBA4A, ASAH1, ATP6V1B2, SVBP (small vasohibin binding protein), AIFM1, UBC (ubiquitin C), IFI30, SCGN (secretagogin, EF-hand calcium binding protein), MTRNR2L12, GBA (glucosylceramidase beta), TXN2, NQO2, and PPIL1 were involved in the development and progression of cognitive impairment. RPS3A,169 PGAM5,170 RPL7,171 TLK1,172 DDR1,173 ILF3,174 TNRC6A,175 GGCX (gamma-glutamyl carboxylase),176 S100A6,177 LSAMP (limbic system associated membrane protein),178 KCNA5,179 LUC7L3,180 ATAD3C,181 SRSF3,182 MCU (mitochondrial calcium uniporter),183 ATP2A2,184 GAA (glucosidase alpha, acid),185 MAGI1,186 WIPF2,187 VAMP8,188 UCHL1,189 CLIC1,190 PSMB5,191 GRB2,192 MPSTE24,193 COX6B1,194 SQSTM1195, COTL1196, CD63197, NDUFB7198, BEX1199 and MTRNR2L8 200 plays a major role in mediating cardiovascular diseases progression. HLA-A,201 VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A),202 RPS26,203 BMP6,204 HLA-B,205 IER3IP1,206 MT1E,207 ACADM (acyl-CoA dehydrogenase medium chain),208 and GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase)209 are associated with progression of Type 1 diabetes mellitus. PEMT (phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase),210 INSM1,211 BCL6,212 RUNX1T1,213 PGRMC2,214 ARID1B,215 CITED2,216 KLF13,217 PPT1,218 ARRDC3,219 HSPA5,220 MDH2,221 and COA3,222 have been previously reported to be a key biomarkers for the early detection of obesity. A previous study demonstrated that IGFBP5,223 PRDX6,224 PKM (pyruvate kinase M1/2),225 PRDX1,226 and USP22227 were more highly expressed in diabetic nephropathy. Durgin et al,228 Zhang et al,229 Hamada et al,230 Gong et al,231 Li et al,232 Lin et al,233 and Schweigert et al234 suggested that CYB5R3, CACNA1A, GLCCI1, CAP1, HSP90AB1, BLVRA (biliverdinreductase A), and CRIP1 were involved in the progression of hypertension. These results suggested that these, cognitive impairment, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, diabetic nephropathy and hypertension responsible genes might influence the development of T2DM through the altered expression. Therefore, these genes might involve in these GO terms and pathways are most likely to be important in the development of T2DM and T2DM associated complications.

By PPI network and module analysis, we identified the hub genes that might affect the origin or advancement of T2DM. TCTN2, SYNPO (synaptopodin), PSMD12, PSMC4, TUBA1C, PSMC5, PSMD7, and RAD23A might serve as a novel target for early diagnosis and specific therapy of T2DM and T2DM associated complications, and the related mechanisms need to be further investigation.

In addition, miRNA-hub gene regulatory network construction and TF-hub gene regulatory network were constructed. In addition, miRNA-mRNA networks were constructed. The roles of hub genes, miRNA and TF in the pathogenesis of T2DM are discussed. Hsa-mir-142-5p,235 hsa-mir-1291,236 NOTCH1,237 PPARD (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta),238 HIF1A,239 RUNX2,240 and E2F1241 levels are correlated with disease severity in patients with T2DM. Previous studies have demonstrated that hsa-mir-216b-5p242 and hsa-mir-200a-3p243 appears to be expressed in Type 1 diabetes. Hsa-mir-1294,244 SUZ12,245 and YAP1246 were responsible for progression of cognitive impairment. Hsa-mir-573247 and SMARCA4248 were linked with progression of hypertension. Therefore, cognitive impairment and hypertension responsible biomarkers might be used as a diagnostic biomarker because of its essential role in the pathogenesis in early T2DM. Our study also suggests that PRKDC (protein kinase, DNA-activated, catalytic subunit), SKIL (SKI like proto-oncogene), NDRG1, hsa-mir-181b-3p, hsa-mir-3157-3p, hsa-mir-3661, hsa-mir-520d-5p, TAF7L, and MITF (Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor) are the novel biomarkers of the entire process of T2DM and T2DM associated complications development and might be used as the novel diagnostic biomarker for T2DM and T2DM associated complications.

The conduct of updating methods was calculated the classification work in which collected a higher score in efficiency, AUC, specificity, and sensitivity. As a result, 10 hub genes with AUC > 0.80 showed excellent diagnostic value for T2DM, and thus were considered as hub genes of T2DM, including APP, MYH9, TCTN2, USP7, SYNPO, GRB2, HSP90AB1, UBC, HSPA5, and SQSTM1. Through these analyses, we expect to provide novel insights into the molecular pathogenesis of T2DM and its associated complications and provide a more detailed molecular mechanism for the development of T2DM treatment. Although bioinformatics analysis has been performed in these present investigations, some limitations exist. Lacking of experimental validation of hub genes is a limitation of the study. In addition, we do not conduct in vitro and in vivo experiments of hub genes in T2DM. Corresponding experiments will be performed to verify in our future investigation, thus conversely testifying in bioinformatics analysis.

In conclusion, the present study identified 10 hub genes (APP, MYH9, TCTN2, USP7, SYNPO, GRB2, HSP90AB1, UBC, HSPA5, and SQSTM1) with crucial role in progression of T2DM; our results suggested these genes could add a new dimension to our understanding of the T2DM and might be served as potential biomarkers that will be assisting endocrinologist in developing novel therapeutic strategies for T2DM patients. However, there are some limitations in this study. Further larger clinical sample size and in-depth clinical experiments are needed to clarify the clear mechanism and warrant the prognostic value of these DEGs in T2DM.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-end-10.1177_11795514231155635 for Bioinformatics Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data Identifies Molecular Biomarkers Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Varun Alur, Varshita Raju, Basavaraj Vastrad, Chanabasayya Vastrad, Satish Kavatagimath and Shivakumar Kotturshetti in Clinical Medicine Insights: Endocrinology and Diabetes

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-end-10.1177_11795514231155635 for Bioinformatics Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data Identifies Molecular Biomarkers Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Varun Alur, Varshita Raju, Basavaraj Vastrad, Chanabasayya Vastrad, Satish Kavatagimath and Shivakumar Kotturshetti in Clinical Medicine Insights: Endocrinology and Diabetes

Supplemental material, sj-docx-3-end-10.1177_11795514231155635 for Bioinformatics Analysis of Next Generation Sequencing Data Identifies Molecular Biomarkers Associated With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus by Varun Alur, Varshita Raju, Basavaraj Vastrad, Chanabasayya Vastrad, Satish Kavatagimath and Shivakumar Kotturshetti in Clinical Medicine Insights: Endocrinology and Diabetes

Acknowledgments

I thank Yurong Xin, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Tarrytown, New York, USA, very much, the author who deposited their NGS dataset GSE81608, into the public GEO database.

Footnotes

ORCID iD: Chanabasayya Vastrad  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3615-4450

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3615-4450

Informed consent: No informed consent because this study does not contain human or animals participants.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Trial registration: Not applicable.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Declarations

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Varun Alur: Methodology; Validation. Varshita Raju: Formal analysis; Validation. Basavaraj Vastrad: Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Chanabasayya Vastrad: Investigation; Software. Satish Kavatagimath: Formal analysis; Resources. Shivakumar Kotturshetti: Resources; Supervision.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) repository [(GSE81608) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE81608)].

References

- 1. Caruso R, Magon A, Baroni I, et al. Health literacy in type 2 diabetes patients: a systematic review of systematic reviews. Acta Diabetol. 2018;55:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gruss SM, Nhim K, Gregg E, Bell M, Luman E, Albright A. Public health approaches to Type 2 diabetes prevention: the US National Diabetes Prevention Program and Beyond. Curr Diab Rep. 2019;19:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Khan MAB, Hashim MJ, King JK, Govender RD, Mustafa H, Al Kaabi J. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes - global burden of disease and forecasted trends. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;10:107-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Magliano DJ, Sacre JW, Harding JL, Gregg EW, Zimmet PZ, Shaw JE. Young-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus - implications for morbidity and mortality. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2020;16:321-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borzouei S, Soltanian AR. Application of an artificial neural network model for diagnosing type 2 diabetes mellitus and determining the relative importance of risk factors. Epidemiol Health. 2018;40:e2018007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rojas J, Bermudez V, Palmar J, et al. Pancreatic beta cell death: novel potential mechanisms in diabetes therapy. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:9601801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Grarup N, Rose CS, Andersson EA, et al. Studies of association of variants near the HHEX, CDKN2A/B, and IGF2BP2 genes with type 2 diabetes and impaired insulin release in 10,705 Danish subjects: validation and extension of genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56:3105-3111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pascoe L, Tura A, Patel SK, et al. Common variants of the novel type 2 diabetes genes CDKAL1 and HHEX/IDE are associated with decreased pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes. 2007;56:3101-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Shi H, Lu Y, Du J, et al. Application of back propagation artificial neural network on genetic variants in adiponectin ADIPOQ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, and retinoid X receptor-α genes and type 2 diabetes risk in a Chinese Han population. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gloyn AL, Weedon MN, Owen KR, et al. Large-scale association studies of variants in genes encoding the pancreatic beta-cell KATP channel subunits Kir6.2 (KCNJ11) and SUR1 (ABCC8) confirm that the KCNJ11 E23K variant is associated with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52:568-572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng X, Ren W, Zhang S, et al. Association of type 2 diabetes susceptibility genes (TCF7L2, SLC30A8, PCSK1 and PCSK2) and proinsulin conversion in a Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Y, Liu Y, Liang J, Wang T, Sun M, Zhang Z. Gymnemic acid ameliorates hyperglycemia through PI3K/AKT- and AMPK-Mediated signaling pathways in Type 2 diabetes mellitus rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:13051-13060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Suhara T, Baba Y, Shimada BK, Higa JK, Matsui T. The mTOR signaling pathway in myocardial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mackenzie RW, Elliott BT. Akt/PKB activation and insulin signaling: a novel insulin signaling pathway in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2014;7:55-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Abo El-Nasr NME, Saleh DO, Mahmoud SS, et al. Olmesartan attenuates type 2 diabetes-associated liver injury: cross-talk of AGE/RAGE/JNK, STAT3/SCOS3 and RAS signaling pathways. Eur J Pharmacol. 2020;874:173010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ozaki KI, Awazu M, Tamiya M, et al. Targeting the ERK signaling pathway as a potential treatment for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2016;310:E643-E651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mao Y, Shen J, Lu Y, et al. RNA sequencing analyses reveal novel differentially expressed genes and pathways in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:42537-42547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Podder NK, Rana HK, Azam MS, et al. A system biological approach to investigate the genetic profiling and comorbidities of type 2 diabetes. Gene Rep. 2020;21:100830. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rahman MH, Peng S, Hu X, et al. A network-based bioinformatics approach to identify molecular biomarkers for type 2 diabetes that are linked to the progression of neurological diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hasan MI, Hossain MA, Bhuiyan P, Miah MS, Rahman MH. A system biology approach to determine therapeutic targets by identifying molecular mechanisms and key pathways for type 2 diabetes that are linked to the development of tuberculosis and rheumatoid arthritis. Life Sci. 2022;297:120483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hossain MA, Al Amin M, Hasan MI, et al. Bioinformatics and system biology approaches to identify molecular pathogenesis of polycystic ovarian syndrome, type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease that are linked to the progression of female infertility. Inform Med Unlocked. 2022;30:100960. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rahman MH, Peng S, Hu X, et al. Bioinformatics methodologies to identify interactions between type 2 diabetes and neurological comorbidities. IEEE Access. 2019;7:183948-183970. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prashanth G, Vastrad B, Tengli A, Vastrad C, Kotturshetti I. Investigation of candidate genes and mechanisms underlying obesity associated type 2 diabetes mellitus using bioinformatics analysis and screening of small drug molecules. BMC Endocr Disord. 2021;21:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1418:93-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Xin Y, Kim J, Okamoto H, et al. RNA sequencing of single human islet cells reveals type 2 diabetes genes. Cell Metab. 2016;24:608-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, et al. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thomas PD. The gene ontology and the meaning of biological function. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1446:15-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fabregat A, Jupe S, Matthews L, et al. The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D649-D655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reimand J, Kull M, Peterson H, Hansen J, Vilo J. g:Profiler–a web-based toolset for functional profiling of gene lists from large-scale experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W193-W200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kotlyar M, Pastrello C, Malik Z, Jurisica I. IID 2018 update: context-specific physical protein-protein interactions in human, model organisms and domesticated species. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D581-D589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498-2504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pržulj N, Wigle DA, Jurisica I. Functional topology in a network of protein interactions. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:340-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nguyen TP, Liu WC, Jordán F. Inferring pleiotropy by network analysis: linked diseases in the human PPI network. BMC Syst Biol. 2011;5:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shi Z, Zhang B. Fast network centrality analysis using GPUs. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fadhal E, Gamieldien J, Mwambene EC. Protein interaction networks as metric spaces: a novel perspective on distribution of hubs. BMC Syst Biol. 2014;8:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zaki N, Efimov D, Berengueres J. Protein complex detection using interaction reliability assessment and weighted clustering coefficient. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fan Y, Xia J. miRNet-functional analysis and visual exploration of miRNA-target interactions in a network context. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1819:215-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhou G, Soufan O, Ewald J, Hancock REW, Basu N, Xia J. NetworkAnalyst 3.0: a visual analytics platform for comprehensive gene expression profiling and meta-analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W234-W241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, et al. pROC: an open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ren C, Li M, Du W, et al. Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis reveals hub genes and inflammation state of rheumatoid arthritis. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Erfanian Omidvar M, Ghaedi H, Kazerouni F, et al. Clinical significance of long noncoding RNA VIM-AS1 and CTBP1-AS2 expression in type 2 diabetes. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:9315-9323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Duraisamy P, Elango S, Vishwanandha VP, Balamurugan R. Prevalence of mitochondrial tRNA gene mutations and their association with specific clinical phenotypes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus of Coimbatore. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:49-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kumar U, Singh S. Role of somatostatin in the regulation of central and peripheral factors of Satiety and obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gougeon R, Marliss EB, Jones PJ, Pencharz PB, Morais JA. Effect of exogenous insulin on protein metabolism with differing nonprotein energy intakes in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:250-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yao K, Zeng L, He Q, Wang W, Lei J, Zou X. Effect of probiotics on glucose and lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of 12 randomized controlled trials. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:3044-3053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gaster M, Nehlin JO, Minet AD. Impaired TCA cycle flux in mitochondria in skeletal muscle from type 2 diabetic subjects: marker or maker of the diabetic phenotype? Arch Physiol Biochem. 2012;118:156-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chung ST, Hsia DS, Chacko SK, Rodriguez LM, Haymond MW. Increased gluconeogenesis in youth with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2015;58:596-603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Daryabor G, Atashzar MR, Kabelitz D, Meri S, Kalantar K. The effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus on organ metabolism and the immune system. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wu WL, Hao J, Domalski M, et al. Discovery of novel tricyclic heterocycles as potent and selective DPP-4 inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7:498-501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shoukry A, Bdeer SEL-A, El-Sokkary RH. Urinary monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 and vitamin D-binding protein as biomarkers for early detection of diabetic nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mol Cell Biochem. 2015;408:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hearn T, Spalluto C, Phillips VJ, et al. Subcellular localization of ALMS1 supports involvement of centrosome and basal body dysfunction in the pathogenesis of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:1581-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bouché C, Serdy S, Kahn CR, Goldfine AB. The cellular fate of glucose and its relevance in type 2 diabetes. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:807-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Turner R, Stratton I, Horton V, et al. UKPDS 25: autoantibodies to islet-cell cytoplasm and glutamic acid decarboxylase for prediction of insulin requirement in type 2 diabetes. UK prospective Diabetes Study Group. Lancet. 1997;350:1288-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cheung A, Kusari J, Jansen D, Bandyopadhyay D, Kusari A, Bryer-Ash M. Marked impairment of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B activity in adipose tissue of obese subjects with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;134:115-123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wittenbecher C, Ouni M, Kuxhaus O, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 2 (IGFBP-2) and the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2019;68:188-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Castro A, Lázaro I, Selva DM, et al. APOH is increased in the plasma and liver of type 2 diabetic patients with metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2010;209:201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Caron D, Boutchueng-Djidjou M, Tanguay RM, Faure RL. Annexin A2 is SUMOylated on its N-terminal domain: regulation by insulin. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:985-991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Podestà F, Romeo G, Liu WH, et al. Bax is increased in the retina of diabetic subjects and is associated with pericyte apoptosis in vivo and in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1025-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liu T, Zhao Y, Tang N, et al. Pax6 directly down-regulates pcsk1n expression thereby regulating PC1/3 dependent proinsulin processing. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Kim YI, Lee FN, Choi WS, Lee S, Youn JH. Insulin regulation of skeletal muscle PDK4 mRNA expression is impaired in acute insulin-resistant states. Diabetes. 2006;55:2311-2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Alsters SIM, Goldstone AP, Buxton JL, et al. Truncating homozygous mutation of carboxypeptidase E (CPE) in a morbidly obese female with type 2 diabetes mellitus, intellectual disability and hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Yu T, Lu XJ, Li JY, et al. Overexpression of miR-429 impairs intestinal barrier function in diabetic mice by down-regulating occludin expression. Cell Tissue Res. 2016;366:341-352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kodama K, Horikoshi M, Toda K, et al. Expression-based genome-wide association study links the receptor CD44 in adipose tissue with type 2 diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:7049-7054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Goldfine AB, Crunkhorn S, Costello M, et al. Necdin and E2F4 are modulated by rosiglitazone therapy in diabetic human adipose and muscle tissue. Diabetes. 2006;55:640-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Mtiraoui N, Turki A, Nemr R, et al. Contribution of common variants of ENPP1, IGF2BP2, KCNJ11, MLXIPL, PPARγ, SLC30A8 and TCF7L2 to the risk of type 2 diabetes in Lebanese and Tunisian Arabs. Diabetes Metab. 2012;38:444-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Castelblanco E, Sanjurjo L, Falguera M, et al. Circulating soluble CD36 is similar in type 1 and Type 2 diabetes mellitus versus non-diabetic subjects. J Clin Med. 2019;8:710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Krause C, Sievert H, Geißler C, et al. Critical evaluation of the DNA-methylation markers ABCG1 and SREBF1 for type 2 diabetes stratification. Epigenomics. 2019;11:885-897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Huang Q, Xue J, Zou R, et al. NR4A1 is associated with chronic low-grade inflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Exp Ther Med. 2014;8:1648-1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chang TJ, Chiu YF, Sheu WHH, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of PCSK2 are associated with glucose homeostasis and progression to type 2 diabetes in a Chinese population. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Herold Z, Herold M, Rosta K, Doleschall M, Somogyi A. Lower serum chromogranin B level is associated with type 1 diabetes and with type 2 diabetes patients with intensive conservative insulin treatment. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2020;12:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Mayer AE, Löffler MC, Loza Valdés AE, et al. The kinase PKD3 provides negative feedback on cholesterol and triglyceride synthesis by suppressing insulin signaling. Sci Signal. 2019;12:eaav9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang J, Zhang M, Yang Z, et al. PDCD4 deficiency ameliorates left ventricular remodeling and insulin resistance in a rat model of type 2 diabetic cardiomyopathy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2020;8:e001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mastracci TL, Colvin SC, Padgett LR, Mirmira RG. Hypusinated eIF5A is expressed in the pancreas and spleen of individuals with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0230627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hoseini-Aghdam M, Sheikh V, Eftekharian MM, Rezaeepoor M, Behzad M. Enhanced expression of TIGIT but not neuropilin-1 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Immunol Lett. 2020;225:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yoon HY, Lee MH, Song Y, Yee J, Song G, Gwak HS. ABCA1 69C>T polymorphism and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and updated meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12:639524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chen YT, Lin WD, Liao WL, Tsai YC, Liao JW, Tsai FJ. NT5C2 methylation regulatory interplay between DNMT1 and insulin receptor in type 2 diabetes. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zhao H, Ma L, Yan M, et al. Association betweenMYH9andAPOL1gene polymorphisms and the risk of diabetic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes in a Chinese Han population. J Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Huang J, Zeng T, Tian Y, et al. Clinical significance of high-mobility group box-1 (HMGB1) in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) combined with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). J Clin Lab Anal. 2019;33:e22910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Li SF, Zhu CS, Wang YM, et al. Downregulation of β1,4-galactosyltransferase 5 improves insulin resistance by promoting adipocyte commitment and reducing inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kim MK, Yun KJ, Chun HJ, et al. Clinical utility of serum beta-2-microglobulin as a predictor of diabetic complications in patients with type 2 diabetes without renal impairment. Diabetes Metab. 2014;40:459-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ye M, Li D, Yang J, et al. MicroRNA-130a targets MAP3K12 to modulate diabetic endothelial progenitor cell function. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;36:712-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Pearce LR, Atanassova N, Banton MC, et al. KSR2 mutations are associated with obesity, insulin resistance, and impaired cellular fuel oxidation. Cell. 2013;155:765-777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Nakhate KT, Yedke SU, Bharne AP, Subhedar NK, Kokare DM. Evidence for the involvement of neuropeptide Y in the antidepressant effect of imipramine in type 2 diabetes. Brain Res. 2016;1646:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kogawa EM, Grisi DC, Falcão DP, et al. Impact of glycemic control on oral health status in type 2 diabetes individuals and its association with salivary and plasma levels of chromogranin A. Arch Oral Biol. 2016;62:10-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Bitar MS. Diabetes impairs angiogenesis and induces endothelial cell senescence by up-regulating thrombospondin-CD47-dependent signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kameswaran V, Golson ML, Ramos-Rodríguez M, et al. The dysregulation of the DLK1-MEG3 locus in islets from patients with type 2 diabetes is mimicked by targeted epimutation of its promoter with TALE-DNMT constructs. Diabetes. 2018;67:1807-1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Mori J, Alrob OA, Wagg CS, Harris RA, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. ANG II causes insulin resistance and induces cardiac metabolic switch and inefficiency: a critical role of PDK4. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1103-H1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Guan B, Zhan Z, Wang L, Wang L, Liu L. CXXC4 mediates glucose-induced β-cell proliferation. Acta Diabetol. 2020;57:1101-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Hartz CS, Nieman KM, Jacobs RL, Vance DE, Schalinske KL. Hepatic phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase expression is increased in diabetic rats. J Nutr. 2006;136:3005-3009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Mazoochian L, Mohammad Sadeghi HM, Pourfarzam M. The effect of FADS2 gene rs174583 polymorphism on desaturase activities, fatty acid profile, insulin resistance, biochemical indices, and incidence of type 2 diabetes. J Res Med Sci. 2018;23:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bonomo JA, Guan M, Ng MC, et al. The ras responsive transcription factor RREB1 is a novel candidate gene for type 2 diabetes associated end-stage kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6441-6447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ghosh A, Abdo S, Zhao S, et al. Insulin inhibits nrf2 gene expression via heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein F/K in diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2017;158:903-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Hirota Y, Ohara T, Zenibayashi M, et al. Lack of association of CPT1A polymorphisms or haplotypes on hepatic lipid content or insulin resistance in Japanese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2007;56:656-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Singh S, Chen Y, Matsumoto A, et al. ALDH1B1 links alcohol consumption and diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:768-773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Larsen LH, Rose CS, Sparsø T, et al. Genetic analysis of the estrogen-related receptor alpha and studies of association with obesity and type 2 diabetes. Int J Obes. 2007;31:365-370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Dong S, Blüher M, Zhang Y, Wu H, Alahari SK. Development of insulin resistance in nischarin mutant female mice. Int J Obes. 2019;43:1046-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Shah SK, He S, Guo L, et al. Discovery of MK-1421, a potent, selective sstr3 antagonist, as a development candidate for type 2 diabetes. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:513-517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Hattori Y, Nakajima K, Eizawa T, et al. Heteroplasmic mitochondrial DNA 3310 mutation in NADH dehydrogenase subunit 1 associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and mental retardation in a single patient. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:952-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Cividini F, Scott BT, Suarez J, et al. Ncor2/PPARα-dependent upregulation of MCUb in the type 2 diabetic heart impacts cardiac metabolic flexibility and function. Diabetes. 2021;70:665-679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhang L, Cheng YL, Xue S, Xu ZG. The role of circulating RBP4 in the type 2 diabetes patients with kidney diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:8830471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Abbas S, Raza ST, S Mir S, Siddiqi Z, Mahdi F. No association of SNP 313A→G in GSTP1 with nephropathy, hypertension and dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Br J Biomed Sci. 2019;76:153-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Huang K, Nair AK, Muller YL, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies variation in CYB5A and RNF10 associated with adiposity and type 2 diabetes. Obesity. 2014;22:984-988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Shi Y, Li Y, Wang J, et al. Meta-analyses of the association of G6PC2 allele variants with elevated fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Minchenko DO, Davydov VV, Budreiko OA, et al. The expression of CCN2, IQSEC, RSPO1, DNAJC15, RIPK2, IL13RA2, IRS1, and IRS2 genes in blood of obese boys with insulin resistance. Fiziol Zh. 2015;61:10-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Wang X, Yang R, Jadhao SB, et al. Transmembrane emp24 protein transport domain 6 is selectively expressed in pancreatic islets and implicated in insulin secretion and diabetes. Pancreas. 2012;41:10-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Chen M, Hu C, Zhang R, et al. A variant of PSMD6 is associated with the therapeutic efficacy of oral antidiabetic drugs in Chinese type 2 diabetes patients. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Cai R, Han J, Sun J, et al. Plasma clusterin and the CLU gene rs11136000 variant are associated with mild cognitive impairment in type 2 diabetic patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2016;8:179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kwanbunjan K, Panprathip P, Phosat C, et al. Association of retinol binding protein 4 and transthyretin with triglyceride levels and insulin resistance in rural Thais with high type 2 diabetes risk. BMC Endocr Disord. 2018;18:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Wondafrash DZ, Nire’a AT, Tafere GG, Desta DM, Berhe DA, Zewdie KA. Thioredoxin-interacting protein as a novel potential therapeutic target in diabetes mellitus and its underlying complications. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2020;13:43-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Ying L, Zhang M, Ma X, et al. Macrophage LAMTOR1 deficiency prevents dietary obesity and insulin resistance through inflammation-induced energy expenditure. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:672032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Griffin JWD, Liu Y, Bradshaw PC, Wang K. In silico preliminary association of ammonia metabolism genes GLS, CPS1, and GLUL with risk of Alzheimer’s disease, major depressive disorder, and Type 2 diabetes. J Mol Neurosci. 2018;64:385-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Fougerat A, Pan X, Smutova V, et al. Neuraminidase 1 activates insulin receptor and reverses insulin resistance in obese mice. Mol Metab. 2018;12:76-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Chiva-Blanch G, Peña E, Cubedo J, et al. Molecular mapping of platelet hyperreactivity in diabetes: the stress proteins complex HSPA8/Hsp90/CSK2α and platelet aggregation in diabetic and normal platelets. Transl Res. 2021;235:1-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Kazakova EV, Zghuang T, Li T, Fang Q, Han J, Qiao H. The gas6 gene rs8191974 and ap3s2 gene rs2028299 are associated with type 2 diabetes in the northern Chinese Han population. Acta Biochim Pol. 2017;64:227-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Van der Schueren B, Vangoitsenhoven R, Geeraert B, et al. Low cytochrome oxidase 4I1 links mitochondrial dysfunction to obesity and type 2 diabetes in humans and mice. Int J Obes. 2015;39:1254-1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Haynes V, Connor T, Tchernof A, Vidal H, Dubois S. Metallothionein 2a gene expression is increased in subcutaneous adipose tissue of type 2 diabetic patients. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;108:90-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Ng MCY, Tam CHT, So WY, et al. Implication of genetic variants near NEGR1, SEC16B, TMEM18, ETV5/DGKG, GNPDA2, LIN7C/BDNF, MTCH2, BCDIN3D/FAIM2, SH2B1, FTO, MC4R, and KCTD15 with obesity and type 2 diabetes in 7705 Chinese. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2418-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Subramanian VS, Krishnaswami CV, Damodaran C. HLA, ESD, GLOI, C3 and HP polymorphisms and juvenile insulin dependent diabetes mellitus in Tamil Nadu (south India). Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 1994;25:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wei W, Li Y, Li Y, Li D. Adipose-specific knockout of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2L6 (Ube2l6) reduces diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis. J Pharmacol Sci. 2021;145:327-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Jacobs S, Schiller K, Jansen EH, Boeing H, Schulze MB, Kröger J. Evaluation of various biomarkers as potential mediators of the association between Δ5 desaturase, Δ6 desaturase, and stearoyl-coa desaturase activity and incident type 2 diabetes in the European prospective investigation into cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:155-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Thameem F, Yang X, Permana PA, Wolford JK, Bogardus C, Prochazka M. Evaluation of the microsomal glutathione S-transferase 3 (MGST3) locus on 1q23 as a Type 2 diabetes susceptibility gene in Pima Indians. Hum Genet. 2003;113:353-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Ramprasath T, Murugan PS, Kalaiarasan E, Gomathi P, Rathinavel A, Selvam GS. Genetic association of glutathione peroxidase-1 (GPx-1) and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1(NQO1) variants and their association of CAD in patients with type-2 diabetes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;361:143-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Payne F, Colnaghi R, Rocha N, et al. Hypomorphism in human NSMCE2 linked to primordial dwarfism and insulin resistance. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:4028-4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Liu QC, Zhuang ZH, Zeng K, Cheng ZJ, Gao F, Wang ZQ. Prevalence of pancreatic diabetes in patients carrying mutations or polymorphisms of the PRSS1 gene in the Han population. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2009;11:799-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Quintela I, Barros F, Fernandez-Prieto M, et al. Interstitial microdeletions including the chromosome band 4q13.2 and the UBA6 gene as possible causes of intellectual disability and behavior disorder. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A:3113-3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Yuan Z, Jiao B, Hou L, et al. Mutation analysis of the TIA1 gene in Chinese patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;64:160.e9-160.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Cacace R, Heeman B, Van Mossevelde S, et al. Loss of DPP6 in neurodegenerative dementia: a genetic player in the dysfunction of neuronal excitability. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137:901-918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]