Abstract

Objective:

Multiple barriers in research participation have excluded the Chinese older adults from benefitting the recent advancement of aging sciences. The paucity of systematic understanding of Chinese aging population necessitated the Population-Based Study of ChINese Elderly in Chicago (PINE).

Method:

Guided by community-based participatory research approach, the PINE study is a population-based epidemiological study of Chinese older adults aged 60 and above in the Greater Chicago area.

Results:

We described study design and implantation of the PINE study, highlighting strategies in adapting a population-based study design to the Chinese community. These measures included community-engaged recruitment, innovative data collection methods, and culturally and linguistically sensitive study infrastructure.

Discussion:

The intricate cultural and linguistic diversity among U.S. Chinese older adults, coupled with their demographic characteristics and residential pattern, present challenges and opportunities in implementing a population-based study of older adults. Implications for the research and practice in relation to future minority aging and social sciences studies are discussed.

Keywords: aging, population-based study, Chinese older adults, community-based participatory research

Introduction

The overall goal of the Population-Based Study of ChINese Elderly in Chicago (PINE) (松年研究, sōng nián yán jiū) is to understand the issues of psychological and social well-being in the lives of U.S. Chinese older adults. The study enrolled 3,159 Chinese community-dwelling older adults aged 60 and above in the Greater Chicago area, and provided one of the first population-based epidemiological samples of this largest and oldest Asian American subgroup. Despite the rapid growth of Chinese aging population in recent years, systematic research on Chinese older adults is scarce. Evidence suggests that multiple social and structural barriers compounded with cultural and linguistic challenges may prohibit minority immigrants from understanding and participating in health research studies (Guo, 2000; Norman, 1988; Shinagawa, 2008; Wong, 1998). As a result, there exists incomplete understanding of many critical psychological and social well-being issues facing the diverse aging populations, and public health and policy goals specific to the needs of the community remain under-developed. Building on the strengths of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach, the PINE study aims to address the knowledge void by capturing the complex cultural, ethnic, and environmental considerations that may be overlooked in aging-related research.

A History and Demographic Rationale to Develop the PINE Study

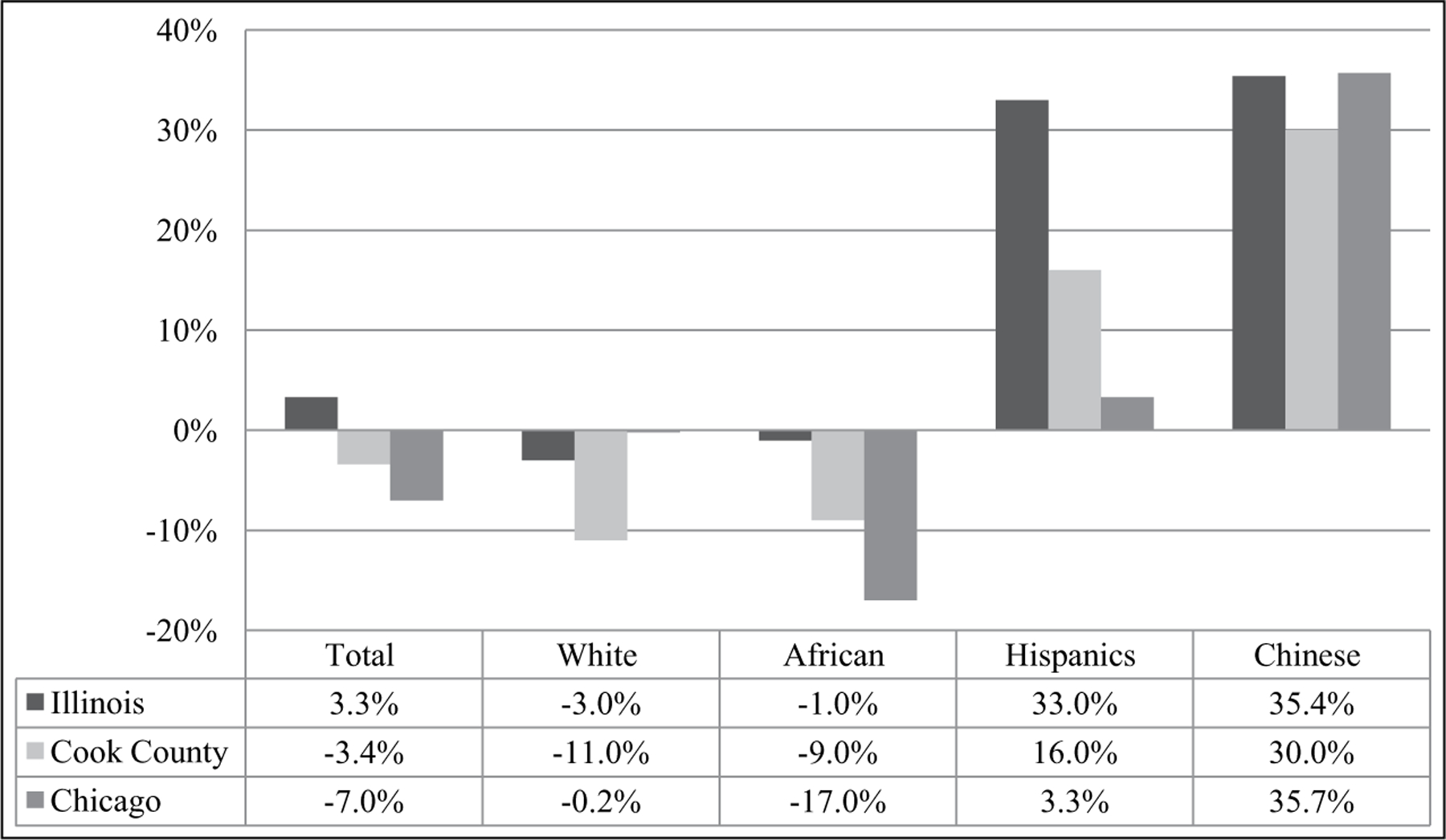

Chinese American community is the oldest and largest Asian population in the United States (Barnes & Bennett, 2002; Bennett & Martin,1995). It is also among the fastest growing U.S. Asian population. However, the growth of the U.S. Chinese population has been impeded by the past anti-Chinese sentiment and U.S. immigration policies (Table 1). As the ethnic/racial minority group that was the first to be brought to the United States as “indentured servants” to build the transcontinental railroads in the 1860s, Chinese populations have endured harsh violence and discrimination (Shinagawa, 2008; Takaki, 1998). This culminated into the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which outlawed all Chinese immigration to the United States and denied citizenship to those already settled in the country, marking Chinese immigrants as the first group to be legally barred to becoming naturalized citizens in the United States. After more than 60 years of repression, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943 and quotas established for Chinese immigration, allowing families to reunite for the first time. However, legal opportunities for Chinese immigration to the United States did not expand significantly until the reform of the U.S. immigration system in 1965 (Zhou, 2009). The number of U.S. Chinese immigrants has increased steadily each decade since then, when the population stood at just under 240,000, to reach 4 million in 2011 (American Community Survey, 2011). In the past decade, the Chinese community grew at a faster rate compared with non-Hispanic White, African American, and Latino populations in the state of Illinois. Similar trends were observed in Cook county and the city of Chicago (Figure 1). It is projected that the Asian American population will increase to 41 million in 2050, nearly tripling in size (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010).

Table 1.

Overview of Chinese Americans History Timeline.

| 1830 | The first U.S. Census notation recorded three Chinese living in the United States. |

| 1849 | During the California Gold Rush, Chinese arrived in California in large numbers. |

| 1858 | California legally prohibited Chinese immigration. |

| 1869 | First transcontinental railroad was completed with a workforce of over 80% of Chinese workers. |

| 1870 | Congress passed the Naturalization Act, barring Chinese from obtaining U.S. citizenship. Anti-Chinese sentiment along the Pacific Coast dispersed Chinese immigrants to the Midwestern and Eastern states, bringing the first Chinese to Chicago. |

| 1871 | The Chinese Massacre in LA occurred where Chinese residents in Chinatown were robbed and murdered by a racially motivated mob. |

| 1880 | Anti-Chinese riots spread throughout the West and led to racially motivated violence and massacres. The Chicago Chinese Community began to form in the downtown loop area, near W. Van Buren and S. Clark street. |

| 1882 | The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed. A significant restriction on free immigration in U.S. history, the Exclusion Act outlawed all Chinese immigration to the United States and denied citizenship to those already settled in the country. |

| 1898 | United States versus Wong Kim Ark: this was a Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled everyone born in the United States is a U.S. citizen. |

| 1900 | Chinese Exclusion Act was renewed and extended indefinitely. |

| 1912 | In Chicago, due to the increasing rent prices and racial discrimination, the majority of Chinese moved to the near south side of Chicago. A new Chinatown located near Wentworth and Cermak roads was established. |

| 1925 | Chinese wives of American citizens were denied entry. |

| 1943 | The Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed. A second wave of Chinese immigrants arrived, seeking economic opportunity and reuniting with families. |

| 1952 | Groups of Mandarin-speaking professionals settled in the suburban areas of Chicago after the revolution in mainland China. |

| 1965 | The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 increased the quota of immigrants from China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. |

| 1975 | More than 130,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, and China entered the United States through the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act. A large number of ethnic Chinese from Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, and Laos settled down in the uptown Argyle Neighborhood after the conclusion of the Vietnam War. |

| 1989 | Tiananmen Square protests occurred. An executive order was issued to allow mainland Chinese scholars, students, and families to permanently remain in the United States. |

| 1990 | The 1990 Immigration Act increased the total immigration to the United States and increased visa quotas by 40%. Family reunification continued as a main immigration focus. Increasing numbers of people in China could afford to study abroad, and an increasing number of Chinese young professionals came to study and work in Chicago. |

| 2012 | With the passage of Senate and House resolution, the Congress issued a formal apology for the Chinese Exclusion Act. In Chicago, Chinatown celebrates its Centennial Anniversary. |

Figure 1.

Population change by racial/ethnic groups, 2000–2010.

Source. U.S. Census (2010).

Whereas the U.S. Chinese population is becoming a larger proportion of the country’s growing minority-majority, population-based research on the health of Chinese older adults has been difficult due to challenges in data collection, subgroup heterogeneity, and recruitment barriers (Guo, 2000; Moreno-John et al., 2004; Norris et al., 2007; Parikh, Fahs, Shelley, & Yerneni, 2009). The vast heterogeneity among subgroups of Asian descents, particularly on psychological and social well-being indicators, has been well documented (Kim et al., 2010). However, most federal level health data collection often aggregates diverse Asian groups under the same racial category, masking the specific health disparities facing the Chinese aging population.

Moreover, the Chinese population is inherently diverse. Although the ethnic Han group constitutes the majority in P.R. China, China’s other 55 minority nationalities account for 123.3 million people, which is the equivalent of 40% of the total U.S. population. Linguistic diversity as a by-product was evident. Among 56 ethnic groups, 53 have their own language, and 21 have written scripts (Xu & Wang, 2007). Mandarin is the predominant dialect spoken in the country alongside other mutually unintelligible languages. In overseas Chinese communities, Cantonese and Mandarin were among the most commonly used dialects. These forms of speech, according to linguists, could be as far apart as English and Dutch, or French and Italian (DeFrancis, 1984; Ramsey, 1989). Vast intra-group diversity in Chinese cultures and languages further presented challenges to identify U.S. Chinese older adults’ growing needs of health care (Lauderdale, Kuohung, Chang, & Chin, 2003). In addition, the anti-Chinese sentiment in the past has continued to influence Chinese community’s sense of distrust on the city, state, and federal government-sponsored research activities. For these historical rationale and socio-demographic characteristics in the context of population aging, one important priority in the nation’s health research agenda is to provide systematic community-level data for Chinese older adults in the United States.

In this following report, we aim to describe the study design and field implantation of the PINE study in full detail, with an emphasis on its unique features in meeting the needs of the U.S. Chinese aging population. We will also discuss the community and practice implications of study design in relation to future minority aging and social sciences research.

Method

CBPR

To prepare for a population-based study aimed to assess health and well-being of the Chinese aging population, we implemented the CBPR approach to collaborate with the Chinese community in Greater Chicago area. CBPR has been proven as an effective approach in increasing public health research relevancy (Horowitz, Robinson, & Seifer, 2009; Leung, Yen, & Minkler, 2004; Wallerstein, 2006). Guided by CBPR principles, our community−academic partnership is a synergetic collaboration between Rush Institute for Healthy Aging, Northwestern University, and many community-based social services agencies dedicated to serving Chinese Americans throughout the Greater Chicago area.

The formation and conduct of the community−academic partnership allows us to develop appropriate research methodology in accordance with Chinese cultural context, in which community advisory board (CAB) played a pivotal role in providing useful perspectives and strategies for aging research conduct and partnership sustainability (Dong, Chang, Wong, & Simon, 2011a, 2011b). Board members were community stakeholders and residents enlisted through over 20 civic, health, social and advocacy groups, community centers, and clinics in the city and suburbs of Chicago. The board works extensively with an investigative team to develop and examine study instrument to ensure cultural sensitivity and appropriateness. In addition, the board is deeply involved in guiding a series of ongoing community-health outreach initiatives to educate older adults on the benefits of aging research through outreach workshops and trainings, community-health newsletters, and continuing focus group discussions (Dong, Li, Chen, Chang, & Simon, 2013).

Development Process for the Study Instruments

In Chinese culture, the image of “PINE” (松Sōng) symbolizes longevity, resilience, respect, and successful aging, and in keeping with research objectives of this community−academic partnership has been aptly chosen as a lexical title for the study. In developing the instruments and protocols for the collection of studying the physical, cognitive, psychological, and social well-being of older adults, the research team worked alongside with the CAB to determine the measurement domains necessary to address the aims of the study. When domains were selected, research staff conducted a thorough review of relevant literature on global Chinese populations and consulted with experts in the field. If no existing measurements were readily available in the literature, research team and the board jointly developed questions based on its epidemiological expertise and community service experience.

Cohort Recruitment

The PINE study wished to invite older adults above 60 years who self-identified as Chinese in the Greater Chicago area. The age of 60 is a culturally constructed meaning of old age in traditional Chinese culture. In addition, the age of 60 is socially and functionally marked as equivalent to retirement age in China. Therefore, for the PINE study, we used 60 years or older as the definition of an older person.

However, based on the U.S. census estimates, only approximately 1.6% of households in the city of Chicago contain a Chinese individual. Identifying such households and the eligible participant 60 years and older within them would have involved a relatively expensive cost and less targeted operation. In addition, evidence suggests that Chinese older adults in metropolitan areas experience high levels of concentration in ethnic enclaves such as the two main Chinatowns in the city, and smaller clusters throughout the Greater Chicago area (Ling, 2012). This highly segregated residential pattern may be a result of the harsh racial sentiment and diverse immigration trajectories in the past, coupled with the lower levels of acculturation in which approximately one in three Chinese older adults immigrated after turning 60 (Mui & Shibusawa, 2008). In light of these factors, the research team implemented a targeted community-based recruitment strategy by first engaging community centers as our main recruitment sites throughout the Greater Chicago area. These sites included (in alphabetical order) Appleville Apartments, Asian Health Coalition, Benton House, Chinese American Service League (CASL), CASL Senior Housing, Chicago Chinese Benevolent Association, Chinatown Elderly Apartments, Chinese Mutual Aid Association, Hilliard Apartments, Midwest Asian Health Coalition, Pine Tree Council, Pui Tak Center, Shields Apartments, South-East Asia Center, St. Therese Chinese Catholic Church, and Xilin Asian Community Center, to name a few.

With over 20 community-based social services agencies, community centers, faith-based organizations, senior apartments, and social clubs on board, we effectively integrated study recruitment with routine services provided to Chinese families throughout the city and suburban areas. One of our major recruitment sites, CASL, is the oldest and largest social services agency serving the needs of Chinese Americans in the Midwest. Situated in the hub of Chinatown in the near south side of Chicago, more than 17,000 clients are served on a yearly basis with a large proportion being Chinese older adults. Another main site, the Xilin Asian Community Center, plays a key role in providing social services to a rapidly growing population of suburban Chinese families. Through sharing outreach channels and field experiences with organizations as such, the research team was able to identify, outreach, and extend study invitation to eligible older adults in a vast geographical region of the Greater Chicago area (Simon, Chang, Rajan, Welch, & Dong, 2014).

Several additional strategies were used to encourage participation in the study and increase cultural and linguistic appropriateness of the study. The project was first announced and later promoted frequently in the local Chinese quarterly newspapers in collaboration with community-based organizations. Flyers and posters advertising the study were placed in the public spaces including restaurants, teahouses, and parks frequented by Chinese families. Eligible older adults who came to the recruitment sites were approached after their attendance in community center-sponsored health promotion activities or cultural activities, such as calligraphy, Chinese painting classes, and social activities. In occasions where we gave community-health educational workshops, Chinese participants were not only empowered by proven ways of health promotion, but they also learned about potential contributions to moving aging science forward by participating in the PINE study. Due to the closely knitted ethnic social network connecting the families of Chinese immigrants, over a third of PINE study participants learned about the project through family members, neighbors, acquaintance, or friends.

Owing to the fact that collective decision-making remains a core value of Chinese culture, we asked older adults to consult with their family members regarding study participation. Older adults who agreed to participate were then scheduled for a face-to-face in-home interview. Participants were surveyed in their preferred language and dialects including Mandarin, Cantonese, Toishanese, Teochew dialect, or English. Older adults who were reluctant to participate were invited to stay in touch with the research team for further information in the future. All recruitment materials were prepared in English and Chinese scripts. Out of 3,542 eligible Chinese older adults who were approached, 3,159 agreed to the study, yielding a response rate of 91.9%. All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Rush University Medical Center.

Interviewer Training

After developing the field methods, it was imperative to recruit, screen, and train research assistants to conduct quality in-home interviews. Research assistants were recruited through community partners and were equipped with multi-lingual abilities. Conventional interviewer skills including good communication and listening skills are crucial. Giving some questions in the in-home interviews with respect to psychological and social well-being may be sensitive and personal in nature, the abilities to establish a trusting relationship with interviewee are imperative. Prior to field interviews, all hired interviewers attended an intensive training that covered from proper data collection techniques, survey questionnaire administration, to in-person communication skills, basic understanding of health sciences research and mock-interview role play. During the field data collection period, booster trainings combined with staff meetings were conducted once to two times a month to reinforce specific aspects of in-person training, and provide additional training on new issues emerged from the field work.

Data Collection

The quality of public health research data is often dampened by the error-prone data entry system (World Health Organization, 2003). Such clerical errors may occur frequently when data are transferred from original source documents to data collection worksheets. Collecting health information from minority older adults may be even more challenging due to the complexities in linguistic issues and physical frailty.

In view of these barriers in data collection, the research team developed a novel software application tailored toward the diverse linguistic needs of Chinese older adults. First, when conducting the survey, each research assistant was equipped with a tablet computer preloaded with interview questions. The compact size of a tablet computer served effectively as an interview guide, yet without interfering eye-contacts in establishing interview rapport within an efficient time frame. In addition, when research assistants conducted the health interview in English or any Chinese dialect selected by the participant, this web-based application allowed health data to be recorded simultaneously in English, Chinese traditional and simplified characters. The system switched back and forth smoothly between all scripts in its interface, and recorded the information according to the chosen dialect. The state-of-science innovative platform not only permitted efficient data acquisition with fluency in the native language and scripts of the study participant, but further sustained the technical base in reducing the risk of mis-interpretation or over-interpretation.

Several additional mechanisms were in place to assure the quality of data collected. Entry of data through web-based software reduces probabilities of errors, due to the allowable data range checks. A random sample of collected data was periodically generated that allowed study coordinator to re-contact the participants to verify data accuracy independently. Booster trainings were provided based on the uniformity of data detected by the research team.

Discussion

The data collection of the PINE study began in July 2011, and has completed in June 2013. We believe the PINE study is carried out with several noteworthy features in its study development, design, and field implementation, which has the potential to contribute to future population-based studies of aging research among the increasingly diverse U.S. populations.

Low participation of Chinese Americans in epidemiological studies has been a concern for both research and public health reasons (Dong, 2012a; Dong, 2012b). There were a number of investigations that examined the health of Asian American communities, including the Honolulu Heart Program (HHP), Honolulu-Asia Aging Study (HAAS), Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), and National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS). However, these studies primarily focused on specific diseases, such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease of Japanese American men examined in the HHP and HAAS studies, in which the sample did not enroll any Chinese Americans (Harada et al., 2012; Stewart et al., 2005). In addition, existing studies that sampled U.S. Chinese population tended to collect a small cohort of older Chinese Americans. For instance, the MESA study enrolled 307 Chinese Americans aged 65 and older in which the primary aim of the study was to examine clinical cardiovascular disease (Bild et al., 2002; Bild et al., 2005). In the NLAAS study, in which the primary outcome of interest was accessing mental disorders and mental health service utilization in minority populations, a national representative sample of 150 Chinese Americans aged 51 and older were surveyed (Alegria et al., 2004; Takeuchi et al., 2007). There existed limited epidemiological population-based investigations that specifically focused on aging issues among Chinese American older adults (Dong et al., 2010). The PINE study, to our knowledge, is the largest epidemiological study of Chinese older adults in the Western countries with primary aims to examine the psychological and social well-being of Chinese older adults.

Following the community-based, action-oriented collaboration model, the PINE study was led by a synergistic community−academic partnership to overcome barriers in minority health research. Whereas evidence suggests that community-engaged research has been increasingly practiced by gerontologists from relevant disciplines toward healthy aging promotion, health protection, and disease prevention (Baker & Wang, 2006; Blair & Minkler, 2009; Carrasquillo & Chadiha, 2007; Davies & Nolan, 2003; Norris et al., 2007), the PINE study design and operations further demonstrate its applicability to a racial/ethnic minority group. Such partnerships can be considered by other population-based studies that examine the health and well-being of minority older adults.

Second, due to the residential patterns of U.S. Chinese older adults who were highly concentrated in selected neighborhoods and at the same time with smaller clusters widely dispersed in and around the city and suburbs, the PINE study implemented an extensive community-based recruitment strategy to reach out to study participants in the Greater Chicago area. Whereas community-based service organizations are often among the most involved partners in collaborative research on health and quality of life issues, an effective recruitment strategy also requires the sustainability of a broad spectrum of community participation (Alexander et al., 2003). Although this recruitment feature requires months and years in exploring, building, and sustaining community relationships with all the Chinese community organizations and agencies in the Greater Chicago area, the population sample of Chinese older adults was obtained with higher resource efficiency and at a lower cost, than if it had to conduct its own screening operation to sample the entire city.

Third, each step of our field implementation is designed toward serving the needs of linguistically and culturally diverse Chinese community. The PINE study was operationalized on a multi-lingual and multi-cultural infrastructure, ranging from interviewer training, study materials, to data collection hardware and software. Infrastructure building in a community-academic research partnership contributes to bridging the current knowledge level with a long-term vision (Wolff & Maurana, 2001). Whereas conventional infrastructure building may be essential, through our community−academic partnership in designing the PINE study, we have learned that utilizing creative measures to address the bilingual and bicultural needs concerning Chinese community are equally critical in maximizing recruitment effort. For instance, when organizing bilingual community-health workshops to empower the community, the research team also aims to enhance community research capacity, leverage the importance of aging research to older adults, as well as for the general well-being of the community-at-large.

Last, we see wide implications of the PINE study design and implementation in meeting the needs of diverse populations. In our case, the cultural contexts present challenges not only for the juxtaposition of community members versus research scientists, but also within the wide diversity of Chinese populations. Embracing various cultural practices implies more than adapting to its specific language needs (Chang, Simon, & Dong, 2012). Our existing partnership experience with Chinese community in planning and conducting a population-based study provides implications on expanding CBPR model to fully address the needs of culturally sensitive research.

Conclusion

As the first population-based study of U.S. Chinese older adults in Greater Chicago area, the PINE study was designed and implemented in accordance with the local cultural, social, and environmental contexts of Chinese aging population. When aging population in the United States is becoming more racially and ethnically diverse, developing an understanding of the multifaceted nature of health and aging of older Americans will be the first step to leverage public policy and practice changes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Community Advisory Board members for their continued effort in this project. Particular thanks are extended to Bernie Wong, Vivian Xu, Yicklun Mo with Chinese American Service League (CASL), Dr. David Lee with Illinois College of Optometry, David Wu with Pui Tak Center, Dr. Hong Liu with Midwest Asian Health Association, Dr. Margaret Dolan with John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital, Mary Jane Welch with Rush University Medical Center, Florence Lei with CASL Pine Tree Council, Julia Wong with CASL Senior Housing, Dr. Jing Zhang with Asian Human Services, Marta Pereya with Coalition of Limited English Speaking Elderly, Mona El-Shamaa with Asian Health Coalition.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Dong was supported by National Institute on Aging grant (R01 AG042318, R01 MD006173, R01 AG11101 & RC4 AG039085), Paul B. Beeson Award in Aging (K23 AG030944), The Starr Foundation, American Federation for Aging Research, John A. Hartford Foundation and The Atlantic Philanthropies.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, Duan N, Shrout P, Meng XL, … Gong F (2004). Considering context, place, and culture: The national Latino and Asian American Study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 208–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JA, Weiner BJ, Metzger ME, Shortell SM, Bazzoli GJ, Hasnain-Wynia R, … Conrad DA (2003). Sustainability of collaborative capacity in community health partnerships. Medical Care Research and Review, 60, 130S–160S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Community Survey. (2011). American Community Survey 2011. U.S Census Bureau, Washington D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TA, & Wang CC (2006). Photovoice: Use of a participatory action research method to explore the chronic pain experience in older adults. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 1405–1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes JS, & Bennett CE (2002). The Asian population: 2000 United State Census 2000 U.S. Census Bureau, Washington D.C. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kbr01-16.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bennett CE, & Martin B (1995). The Asian and Pacific Islander Population. Population Profile of the United States 1995. U.S. Department of Commerce Washington D.C., Bureau of the Census. [Google Scholar]

- Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, DIez Roux AV, Folsom AR, … Tracy RP (2002). Multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis: Objectives and design. American Journal of Epidemiology, 156, 871–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bild DE, Detrano R, Peterson D, Guerci A, Liu K, Shahar E, … Saad MF (2005). Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation, 111, 1313–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair T, & Minkler M (2009). Participatory action research with older adults: Key principles in practice. The Gerontologist, 49, 651–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasquillo O, & Chadiha L (2007). Development of community-based partnerships in minority aging research. Ethnicity & Disease, 17, S3–S5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang E, Simon M, & Dong X (2012). Integrating cultural humility into health care professional education and training. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 17, 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S, & Nolan M (2003). Nurturing research partnerships with older people and their carers: Learning from experience. Quality in Ageing, 4, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- DeFrancis J (1984). The Chinese language: Fact and fantasy Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dong X (2012a). Advancing the field of elder abuse: Future directions and policy implications. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 60, 2151–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X (2012b). Cultural diversity and elder abuse: Implication for research, education, and policy. Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 36, 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Chang ES, Wong E, & Simon M (2011a). Sustaining community-university partnerships: Lessons learned from a participatory research project with elderly Chinese. Gateways International Journal of Community Research & Engagement, 4. Retrieved from http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/ijcre/article/view/1767 [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Chang ES, Wong E, & Simon M (2011b). Working with culture: Lessons learned from a community-engaged project in a Chinese aging population. Aging Health, 7, 529–537. [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Chang E, Wong E, Wong B, Skarupski KA, & Simon MA (2010). Assessing the health needs of Chinese older adults: Findings from a community-based participatory research study in Chicago’s Chinatown. Journal of Aging Research, 2010. Retrieved from 10.4061/2010/124246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Li Y, Chen R, Chang ES, & Simon M (2013). Evaluation of community health education workshops among Chinese older adults in Chicago: A community-based participatory research approach. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 1, 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z (2000). Ginseng and aspirin: Health care alternatives for aging Chinese in New York Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harada N, Takeshita J, Ahmed I, Chen R, Petrovitch H, Ross GW, & Masaki K (2012). Does cultural assimilation influence prevalence and presentation of depressive symptoms in older Japanese American men? The Honolulu-Asia aging study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20, 337–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz CR, Robinson M, & Seifer S (2009). Community-based participatory research from the margin to the mainstream. Circulation, 119, 2633–2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G, Chiriboga DA, Jang Y, Lee S, Huang C, & Parmelee P (2010). Health status of older Asian Americans in California. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58, 2003–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauderdale DS, Kuohung V, Chang SL, & Chin MH (2003). Identifying older Chinese immigrants at high risk for osteoporosis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 18, 508–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung MW, Yen IH, & Minkler M (2004). Community-based participatory research: A promising approach for increasing epidemiology’s relevance in the 21st century. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling H (2012). Chinese Chicago: Race, transnational migration, and community since 1870 Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-John G, Gachie A, Fleming CM, Napoles-Springer A, Mutran E, & Manson SM (2004). Ethnic minority older adults participating in clinical research: Developing trust. Journal of Aging and Health, 16, 93–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mui AC, & Shibusawa T (2008). Asian American elders in the twenty-first century New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norman J (1988). Chinese Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, Miranda J, Duru OK, & Mangione CM (2007). Partnering with community-based organization: An academic institution’s evolving perpective. Ethnicity & Disease, 17, S27–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh NS, Fahs MC, Shelley D, & Yerneni R (2009). Health behaviors of older CHinese adults living in New York City. Journal of Community Health, 34, 6–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey SR (1989). The languages of China Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shinagawa L (2008). A portrait of Chinese Americans Maryland: Asian American Studies Program College Park, MD: University of Maryland. [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Chang E-S., Rajan KB., Welch MJ., & Dong X. (2014). Demographic characteristics of U.S. Chinese older adults in the Greater Chicago area: Assessing the representativeness of the PINE study. Journal of Aging and Health, 26, 1100–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon MA, Magee M, Shah A, Cheung W, Liu H, & Dong XQ. (2008). Building a Chinese community health survey in Chicago: The value of involving the community to more accurately portray health. International Journal of Health and Aging Management, 2, 40–57. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R, Masaki K, Xue QL, Peila R, Petrovitch H, White LR, & Launer LJ (2005). A 32-year prospective study of change in body weight and incident dementia: The Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Archives of Neurology, 62, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaki R (1998). Strangers from a different shore Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi D, Zang N, Hong S, Chae D, Gong F, Gee G, … Alegría M (2007). Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 84–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US (2010). Population: Estimates and projections by age, sex, race/ethnicity (The 2010 Statistical Abstract) Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population/estimates_and_projections_by_age_sex_raceethnicity.html

- Wallerstein NB (2006). Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promotion Practice, 7, 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff M, & Maurana CA (2001). Building effective community-academic partnerships to improve health: A qualitative study of perspectives from communities. Academic Medicine, 76, 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SC (1998). Language Diversity: Problem or Resource? A Social and Educational Perspective on Language Minorities in the United States, edited byMcKay SL. and Wong SC. New York, NY: Newbury House. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2003). Improving data quality: WHO library cataloguing in publication data Geneva, Switzerland: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, & Wang B (2007). Ethnic minorities of China: Journey into China Beijing, China: China Intercontinental Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M (2009). Contemporary Chinese America: Immigration, ethnicity, and community transformation Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]