Abstract

Objective

Care bundles are considered a key tool to improve bedside quality of care in the intensive care unit (ICU). We explored their effect on long-term patient-relevant outcomes.

Design

Systematic literature search and scoping review.

Data sources

We searched PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, APA PsycInfo, Web of Science, CDSR and CENTRAL for keywords of intensive care, care bundles, patient-relevant outcomes, and follow-up studies.

Eligibility criteria

Original articles with patients admitted to adult ICUs assessing bundle implementations and measuring long-term (ie, ICU discharge or later) patient-relevant outcomes (ie, mortality, health-related quality of life (HrQoL), post-intensive care syndrome (PICS), care-related outcomes, adverse events, and social health).

Data extraction and synthesis

After dual, independent, two-stage selection and charting, eligible records were critically appraised and assessed for bundle type, implementation strategies, and effects on long-term patient-relevant outcomes.

Results

Of 2012 records, 38 met inclusion criteria; 55% (n=21) were before–after studies, 21% (n=8) observational cohort studies, 13% (n=5) randomised controlled trials, and 11% (n=4) had other designs. Bundles pertained to sepsis (n=11), neurocognition (n=6), communication (n=4), early rehabilitation (n=3), pharmacological discontinuation (n=3), ventilation (n=2) or combined bundles (n=9). Almost two-thirds of the studies reported on survival (n=24), 45% (n=17) on care-related outcomes (eg, discharge disposition), and 13% (n=5) of studies on HrQoL. Regarding PICS, 24% (n=9) assessed cognition, 13% (n=5) physical health, and 11% (n=4) mental health, up to 1 year after discharge. The effects of bundles on long-term patient-relevant outcomes was inconclusive, except for a positive effect of sepsis bundles on survival. The inconclusive effects may have been due to the high risk of bias in included studies and the variability in implementation strategies, instruments, and follow-up times.

Conclusions

There is a need to explore the long-term effects of ICU bundles on HrQoL and PICS. Closing this knowledge gap appears vital to determine if there is long-term patient value of ICU bundles.

Keywords: Adult intensive & critical care, Quality in health care, Quality of Life

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The protocol of this scoping review has been published in a peer-reviewed journal, and we followed the high standards of the Arksey and O’Malley framework and the Joanna Briggs Institute.

Our search strategy was independently peer-reviewed as recommended in the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies guidelines, and we conducted a comprehensive hand search of reference lists of all included studies and relevant reviews identified in the screening.

We grouped bundle implementation strategies using the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change taxonomy of 73 implementation strategies.

Although not mandatory for scoping reviews, we conducted a quality appraisal of included studies using recommended tools from the Joanna Briggs Institute.

By using ‘bundle’ as an obligatory term in our search strategy, we may have missed articles that implemented bundle-like interventions without explicitly referring to them as ‘bundles’.

Introduction

The complex environment of an intensive care unit (ICU) is characterised by severely ill patients1 and a high density of treatment decisions.2 On average, intensivists face more than 100 treatment decisions per day, where they put evidence-based measures into practice.2 While intensive care research has focused on finding new therapies, little attention has been paid to knowledge transfer.3 This led to a stark discrepancy between research-based best practice and bedside care.3–7 For example, a study on the implementation of 11 evidence-based practices in the ICU found that best-practice care was prescribed in only 56.5% of the instances.8 Existing ICU culture, low prioritisation on introducing novel care strategies, an ICU’s organisational complexity, and lack of staff training have been identified as potential barriers to the implementation of evidence-based practices.7

Care bundles have been heralded as a potential remedy to leap the gap between evidence and practice.9 Care bundles group three to five evidence-based practices.10 Each bundle element stands independently, is non-controversial, has a strong evidence base,10 and the conjunctive application multiplies the effect on patient outcomes.9 Each bundle element is clearly defined, and bundle implementation is monitored continuously.10 Over the last decades, several ICU-specific bundles have emerged, such as the sepsis bundle of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign,11 the ventilator bundle,12 and the ABCDEF bundle.13

Bundle implementation studies in the ICU have commonly assessed bundle adherence,14–17 ICU14 17 18 or hospital mortality,15 18 ICU length of stay,17 18 costs,17 and incidence of adverse events such as ventilator-associated pneumonia.14 16 Undoubtedly, these short-term outcomes, which commonly focus on improvements in quality of care and clinical parameters, remain relevant. Yet, critical care research has acknowledged the importance of long-term patient-relevant sequelae of critical illness.19–21 In addition to long-term mortality, these include a decreased health-related quality of life (HrQoL),22 and specific morbidities like impairments of physical function,23 cognition24 and mental health,25 summarised as post-intensive care syndrome (PICS).26

Previous reviews have explored the effect of non-pharmacological ICU interventions to improve long-term outcomes,27 but we are unaware of previous research on ICU bundles. The effect of the implementation of ICU bundles on long-term patient-relevant outcomes appears unknown. First, we assessed if original ICU bundle research articles have reported effects on long-term patient-relevant outcomes. We included any study that assessed patient outcomes beyond ICU discharge. Second, we determined bundle types, implementation strategies, time points of outcome assessment of included studies. Given the heterogeneous nature of bundles, implementation strategies and outcomes, we considered a scoping review most suitable to answer the research question. With this work, we aim to identify knowledge gaps that may guide future studies on the long-term patient value of ICU bundles.

Methods

Study design and definitions

We conducted a systematic literature search and scoping review to identify the effect of ICU bundles on long-term patient-relevant outcomes. We adhered to the Arksey and O’Malley framework28 and additions,29 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping-Reviews checklist (online supplemental file 1).30 The scoping review was pre-registered on Open Science Framework,31 and the protocol has been published.32

bmjopen-2022-070962supp001.pdf (65.7KB, pdf)

Patient-relevant outcomes were defined as outcomes of mortality, symptoms, adverse events/complications, and social health (eg, return to work).33 Additionally, we included HrQoL and the PICS domains cognition, mental health and physical health. Long-term was defined as assessment at ICU discharge or later, except that we excluded mere assessment of hospital mortality.

Study identification

We searched PubMed, Embase (via Ovid), CINAHL and APA PsycInfo (via EBSCOhost), Web of Science, CDSR and CENTRAL on 12 December 2021 using a combination of English keywords and medical subject headings for four concepts: (1) intensive care, (2) care bundles, (3) patient-relevant outcomes, and (4) follow-up studies, without restrictions to the publication date (online supplemental table S1). On 21 August 2021, a preliminary search and independent pilot screening of 100 records by two authors (ERB and A-CK) was conducted to test and refine the search strategy, which adhered to the guidelines of Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS).34

bmjopen-2022-070962supp002.pdf (341.4KB, pdf)

Study selection

Search results were assessed in a two-stage process. Records were imported to EndNote (V.20.1, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, USA) and, after duplicate removal, imported to Rayyan.35 Two authors (NP and ERB) independently screened titles and abstracts using Rayyan’s blinding option. Additionally, we conducted a hand search of reference lists of all included studies and relevant reviews identified in the screening to find additional literature. Two authors (NP and ERB) independently assessed the full texts of the remaining records. Disagreements between authors were solved through discussions. Reasons for exclusion were documented (online supplemental table S2).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) participants were ≥18 years; (2) more than 50% of the patients received ICU treatment; (3) an ICU care bundle (≥3 bundled measures) was compared with standard care; (4) patient-relevant outcomes were measured at ICU discharge or later; (5) original research article; (6) published in English, German or Spanish. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) paediatric patients; (2) no measurement of patient-relevant outcomes at ICU discharge or later; (3) records were based on expert opinion or secondary research only.

Data charting and critical appraisal

Eligible records were charted individually by two authors (ERB and A-CK) using the Joanna Briggs Institute extraction form,36 which was piloted with 10 publications and refined. Disagreements were resolved through discussions. Study designs were classified following the definitions of the Joanna Briggs Institute.37 Experimental designs without randomised study arm allocation (eg, before–after designs) were classified as quasi-experimental studies. Studies that related the number of performed bundle items or bundle compliance to patient outcomes without implementing an intervention were classified as observational cohort studies. Bundles were categorised: (1) communication, (2) early rehabilitation, (3) neurocognition, (4) pharmacological discontinuation, (5) sepsis, (6) ventilation, and (7) combined bundles (eg, ABCDEF bundle). Outcomes were categorised: (1) survival, (2) HrQoL, (3) care-related outcomes (outcomes pertaining to care after discharge, ie, readmissions or discharge disposition), the PICS domains (4) cognition, (5) mental health, and (6) physical health/mobility, (7) social health (ie, return to work) and (8) adverse events. To enhance the comparability of implementation strategies, we adhered to the taxonomy of implementation strategies proposed in the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project.38 Bundle effects of included studies on long-term patient-relevant outcomes were categorised as positive, possibly positive and no effect. Two authors (ERB and A-CK) individually performed a critical appraisal of included records using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools.37 Disagreements were resolved through discussions. Studies were not excluded based on inferior quality. Study data were managed using MS Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA).

Patient and public involvement

We did not involve patients in designing or conducting the review. For public involvement, we plan to disseminate our results through the authors’ department website.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

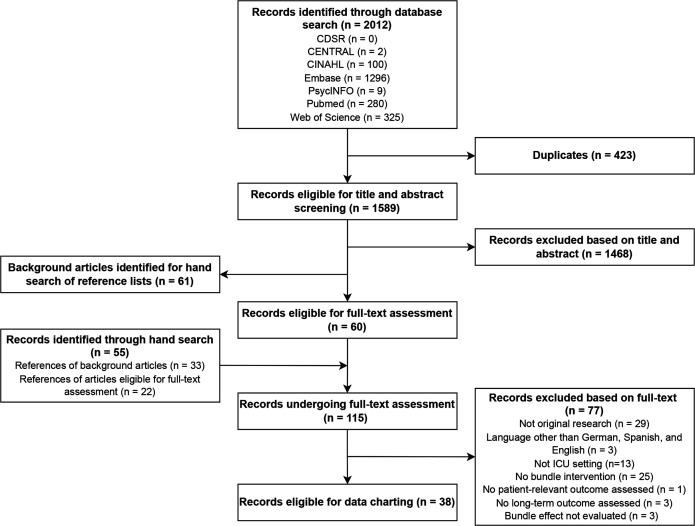

Of identified 2012 records, 60 remained for full-text assessment after dual title and abstract screening. We identified another 55 records through hand search of reference lists of background articles (n=33) and of articles included after screening (n=22). Of 115 records undergoing dual full-text assessment, 77 were excluded, leaving 38 records for dual charting (figure 1, online supplemental table S2).

Figure 1.

Study inclusion flowchart. ICU, intensive care unit.

Articles were published between 2000 and 2022, with half of the studies (n=19) published in 2016 or later. They were conducted in the US (n=15),39–53 France (n=4),54–57 Australia (n=5),58–62 China (n=3),63–65 Spain (n=2),66 67 Norway (n=2),68 69 Scotland,70 Portugal,71 Northern Ireland,72 Italy,73 Germany,74 Canada75 and Uganda (each n=1).76 Two studies depict separate outcome analyses of data collected within one clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01656317).68 69 We identified 19 single-centre studies,39–41 44 45 47 49 50 52 56 62–64 68 69 72–75 three two-centre studies,43 57 76 and 16 multicentre studies.42 46 48 51 53–55 58–61 65–67 70 71 Thirty studies were prospective,39–45 48 51–59 61 62 64–69 71–73 75 76 and eight studies were retrospective.46 47 49 50 60 63 70 74 Eight studies were observational cohort studies,50 53 59 63 65 66 70 71 21 studies were quasi-experimental before–after studies,39–41 43–47 49 54–58 67–69 73–76 1 study was a quasi-experimental single-arm study (which compared patients from the early and late implementation phases of a bundle intervention),51 1 study was a quasi-experimental controlled non-randomised comparative time-series study,72 1 study was a cost-effectiveness analysis,42 5 studies were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (one cluster RCT and 4 individually RCTs)48 52 61 62 64 and 1 study was a quasi-experimental trial following an RCT.60 Settings varied from 42 hospitals59 and 68 ICUs53 to 1 ICU.50 75 Sample sizes varied from 36 05570 to 3062 (online supplemental table S3).

Bundle type and implementation strategies

Eleven studies investigated the implementation of a sepsis bundle based on recommendations from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign or similar.44 45 54 63–67 71 74 76 Nine studies explored combined bundles, including five studies on the ABCDE(F) bundle,41–43 53 62 one study on geriatric-focused practices,50 two studies on a fever, sugar and swallowing bundle60 61 and one study comprising delirium and sedation management, mobilisation and rounding strategies.46 Six studies explored the implementation of neurocognitive bundles, with one sleep quality intervention,40 one psychological intervention,73 two stroke bundles,59 70 one cognitive and physical therapy bundle,52 and one bundle on protocolised sedation, analgesia and delirium management.75 Four studies investigated the implementation of a communication bundle, which comprised interaction with patient and family.39 47 51 72 Three bundles pertained to early rehabilitation.56 68 69 Three studies investigated pharmacological discontinuation bundles on stress ulcer prophylaxis discontinuation,58 antipsychotic medication discontinuation49 and pharmacological delirium management.49 Two studies were about ventilation bundles with lung-protective ventilation and early extubation55 57 (table 1, online supplemental table S3).

Table 1.

Categories of long-term patient-relevant outcomes, by bundle category

| Outcome and bundle category | All (n=38) | Combined bundle (n=9)* | Communication (n=4) | Early rehabilitation (n=3) | Neurocognition (n=6) | Pharmacological discontinuation (n=3) | Sepsis (n=11) | Ventilation (n=2) |

| Survival | 24 (63) | 4 (44) | 1 (25) | 3 (100) | 3 (50) | 1 (33) | 11 (100) | 1 (50) |

| Care-related outcome† | 17 (45) | 6 (67) | 3 (75) | 3 (50) | 2 (67) | 1 (9) | 2 (100) | |

| Health-related quality of life | 5 (13) | 2 (22) | 3 (50) | |||||

| PICS—physical health | 5 (13) | 2 (22) | 2 (67) | 1 (17) | ||||

| PICS—cognition | 9 (24) | 2 (22) | 3 (100) | 3 (50) | 1 (50) | |||

| PICS—mental health | 4 (11) | 1 (11) | 1 (25) | 1 (17) | 1 (33) | |||

| Social health | 1 (3) | 1 (17) | ||||||

| Adverse events | 1 (3) | 1 (33) |

n (%).

*Includes the ABCDEF bundle.

†Care-related outcomes comprise outcomes pertaining to care after intensive care unit discharge, eg, readmissions or discharge disposition.

PICS, post-intensive care syndrome.

We identified 44 ERIC implementation strategies to implement bundles. Most commonly, studies conducted educational meetings (n=23) such as seminars or supervised training, or developed and implemented tools for quality monitoring (n=19), for example, change cycles and algorithms. Often studies developed (n=13) and distributed (n=12) educational materials by, for example, uploading information to the institute’s website or providing posters. Studies identified and prepared champions (n=11) to implement the intervention in their ICU and built a coalition to strengthen partner relationships (n=10). Studies rarely involved executive boards or used advisory boards and workgroups. Notably, reporting of implementation strategies was not standardised, and four studies did not report any implementation strategy (table 2).

Table 2.

Implementation strategies* used in included studies (n=38), in descending order

| Implementation strategy | n (%) | References |

| Conduct educational meetings | 23 (61) | 40–47 49 51 54–58 60–62 67 71–73 75 |

| Develop and implement tools for quality monitoring | 19 (50) | 40 43–47 49 51 52 54–57 62 67 68 71 75 76 |

| Develop educational materials | 13 (34) | 41 47 49 51 54–56 58 60 61 67 71 72 |

| Distribute educational materials | 12 (32) | 41 47 49 51 54–56 58 60 61 71 72 |

| Identify and prepare champions | 11 (29) | 40–43 48 51 60 61 71 75 76 |

| Build a coalition | 10 (26) | 40 41 43 47 49 51 52 68 71 75 |

| Audit and provide feedback | 9 (24) | 39 41–43 46 51 60 61 67 |

| Conduct ongoing training | 8 (21) | 41 43 45 47 49 51 56 75 |

| Develop and organise quality monitoring systems | 8 (21) | 41 42 46–48 51 65 71 |

| Develop a formal implementation blueprint | 7 (18) | 41 43 47 51 54 65 71 |

| Provide ongoing consultation | 6 (16) | 43 48 60–62 71 |

| Change record systems | 5 (13) | 41–43 46 71 |

| Stage implementation scale up | 5 (13) | 40 46 47 62 72 |

| Create new clinical teams | 5 (13) | 41 43 47 60 61 |

| Involve patients/consumers and family members | 4 (11) | 39 47 72 76 |

| Centralise technical assistance | 4 (11) | 46 48 62 71 |

| Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators | 4 (11) | 43 49 60 61 |

| Remind clinicians | 4 (11) | 40 48 60 61 |

| No strategy reported | 4 (11) | 51 61 63 70 |

| Conduct educational outreach visits | 3 (8) | 51 60 61 |

| Tailor strategies | 3 (8) | 47 49 75 |

| Provide clinical supervision | 3 (8) | 43 48 73 |

| Purposely re-examine the implementation | 3 (8) | 41 54 57 |

| Conduct local consensus discussions | 2 (5) | 41 75 |

| Organise clinician implementation team meetings | 2 (5) | 41 55 |

| Facilitation | 2 (5) | 43 72 |

| Provide local technical assistance | 2 (5) | 48 71 |

| Change physical structure and equipment | 2 (5) | 40 75 |

| Conduct cyclical small tests of change | 2 (5) | 46 47 |

| Mandate change | 2 (5) | 43 47 |

| Develop academic partnerships | 2 (5) | 43 71 |

| Make training dynamic | 2 (5) | 55 62 |

| Create a learning collaborative | 1 (3) | 41 |

| Recruit, designate, and train for leadership | 1 (3) | 41 |

| Intervene with patients/consumers to enhance uptake and adherence | 1 (3) | 72 |

| Obtain and use patients/consumers and family feedback | 1 (3) | 72 |

| Prepare patients/consumers to be active participants | 1 (3) | 72 |

| Facilitate relay of clinical data to providers | 1 (3) | 68 |

| Conduct local needs assessment | 1 (3) | 65 |

| Inform local opinion leaders | 1 (3) | 46 |

| Use an implementation advisor | 1 (3) | 46 |

| Involve executive boards | 1 (3) | 43 |

| Work with educational institutions | 1 (3) | 43 |

| Promote adaptability | 1 (3) | 75 |

| Use advisory boards and workgroups | 1 (3) | 75 |

Studies68 69 are separate outcome analyses of unique data collected within one clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01656317).

*According to the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) taxonomy.38

Long-term patient-relevant outcomes used

Almost two-thirds (n=24) of the studies reported survival after hospital discharge, most commonly 28-day,44–46 54 63–67 71 76 30-day,48 70 74 75 60-day,63 90-day,57 61 63 69 180-day,59 70 1 year,42 56 68 or 3–5 year mortality,60 or survival to discharge from acute and rehabilitative care to home and mortality in the rehabilitation facility39 (tables 1 and 3).

Table 3.

Instruments and evaluation periods for the assessment of long-term patient-relevant outcomes

| Outcome category | Instruments | At discharge* | After discharge* | Other time | References | |||||

| 28–30 d/1 m | 60 d/2 m | 90 d/3 m | 180 d/6 m | 1y | 3–5 y | |||||

| Survival (n=24) | Mortality | x† | 44–46 48 54 64–67 71 74–76 | |||||||

| x | x | x | 63 | |||||||

| x | 57 61 69 | |||||||||

| x‡ | 61 69 | |||||||||

| x‡ | x‡ | 70 | ||||||||

| x‡ | 59 | |||||||||

| x§ | 42 | |||||||||

| x¶ | 42 56 68 | |||||||||

| x‡ | 60 | |||||||||

| At discharge to rehabilitation, to home and in rehabilitation | 39 | |||||||||

| HrQoL (n=5) | SF-36 | x | 62 | |||||||

| EQ5D VAS | x | 52 | ||||||||

| EQ5D VAS | x** | x** | 59 | |||||||

| EQ5D domain scores, EQ5D VAS | x | 73 | ||||||||

| QALYs | x§ | 42 | ||||||||

| PICS—cognition (n=9) | Modified Rankin Scale; Glasgow Outcome Scale Extended | x¶ | 68 | |||||||

| Glasgow Outcome Scale | x¶ | 55 | ||||||||

| Modified Rankin Scale | x§ | 61 | ||||||||

| Functional Independence Measure | x | 62 | ||||||||

| CAM-ICU; Digit Span Forward and Backward test; TMT A and B | x†† | 40 | ||||||||

| Tower Test; dysexecutive questionnaire, MMSE | x | x | 52 | |||||||

| Glasgow Coma Scale | x | 69 73 | ||||||||

| ASIA motor and sensitive score | x | x¶ | 56 | |||||||

| PICS—physical health (n=5) | Physical Function ICU Test-scored, Functional Independence Measure | x | 62 | |||||||

| Timed Up-and-Go; Katz Activities of Daily Living; Functional Activities Questionnaire | x | x | 52 | |||||||

| Mobilisation level | x | 69 | ||||||||

| ASIA motor and sensitive score | x | x¶ | 56 | |||||||

| Mean physical component summary score, Barthel index | x§ | 61 | ||||||||

| PICS—mental health (n=4) | Sickness Impact Profile | x§ | x§ | x§ | 72 | |||||

| IES-R; HADS; need for psychotherapy, anxiolytic and/or antidepressant medication | x | 73 | ||||||||

| Antipsychotic medication use | x | 49 | ||||||||

| Mean SF-36 mental component summary score | x§ | 61 | ||||||||

| Care-related outcomes (n=17) | Discharge destination | x | 42 47 48 50 51 53 59 | |||||||

| Change in residence | x | 41 | ||||||||

| Discharge to usual residence | x§ | x§ | 70 | |||||||

| Return to independent living | x | 75 | ||||||||

| ICU readmission rate, ICU discharge destination other than home | x | 53 | ||||||||

| Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylaxis | x | 58 | ||||||||

| ICU-free days and ventilator-free days | x¶ | 55 57 | ||||||||

| Ventilator-free days | x‡‡ | 57 74 | ||||||||

| Readmission rate | x | 43 | ||||||||

| Risk of remaining in the ICU | Until day 20 | 39 | ||||||||

| Discharge diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia | x | 61 | ||||||||

| Adverse events (n=1) | Adverse events | x‡ | 69 | |||||||

| Social health (n=1) | Return to work | x | 73 | |||||||

Studies68 69 are separate outcome analyses of unique data collected within one clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01656317).

*ICU and/or hospital discharge.

†After discharge, except for one study that considered those discharged before 28 days to be alive44 and one study that assessed 30-day mortality after hospital admission.76

‡After stroke.

§After ICU/hospital admission.

¶After trauma/haemorrhage.

**EQ5D VAS measured at 90-180 days after the index event.

††Right after ICU discharge.

ASIA, American Spinal Injury Association; CAM-ICU, Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU; d, days; EQ5D, EuroQol 5 dimensions; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HrQoL, health-related quality of life; ICU, intensive care unit; IES-R, Impact of Event Scale-Revised; m, months; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; QALY, quality-adjusted life year; SF-36, Short Form (36); TMT, Trail Making Test; VAS, visual analogue scale; y, years.

Long-term HrQoL was assessed in five studies.42 52 59 62 73 Concerning the PICS domains, nine studies assessed cognition,40 52 55 56 61 62 68 69 73 five studies assessed physical health,52 56 61 62 69 and four studies assessed mental health.49 61 72 73 Care-related outcomes, that is, outcomes associated with patient care after discharge, were assessed in 17 studies. These include discharge destination,42 47 48 50 51 53 59 change in residence,41 70 return to independent living,75 hospital or ICU readmission rates,43 53 inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylaxis at discharge,58 ICU-free days and ventilator-free days,55 57 74 risk of remaining in the ICU39 or discharge diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia.61 One study assessed adverse events within 90 days after stroke,69 and one study assessed return to work within 12 months73 (tables 1 and 3). Notably, even within similar outcome categories (eg, mental health), studies varied with respect to test instruments used. Further, the time points of outcome measurement varied from ICU discharge to 3–5 years after stroke onset60 (table 3).

Effects on long-term patient-relevant outcomes

We grouped studies based on the effect on patient-relevant outcomes, but due to the variability in instruments and time points, we did not perform a meta-analysis. Thirteen studies found a positive effect of the bundle intervention on survival,44 45 54 55 59 64–67 70 71 74 76 whereas nine studies did not find a survival benefit.39 46 48 56 57 63 68 69 75 Interestingly, 10 of 11 studies on sepsis bundles showed superior survival. For care-related outcomes, HrQoL, and the PICS domains cognition, mental health and physical health, we found mixed evidence: Some studies detected a positive effect, others possibly a positive effect, and other studies could not find any effect at all (table 4, online supplemental table S4).

Table 4.

Effects of bundles on long-term patient-relevant outcomes

| Bundle category | Outcome | Effect | ||

| Positive | Possibly positive | None | ||

| All (n=38) | Survival | 1344 45 54 55 59 64–67 70 71 74 76 | 260 61 | 939 46 48 56 57 63 68 69 75 |

| Care-related outcomes * | 1239 42 49–51 53 55 57–59 70 75 | 443 47 61 62 | 541 48 69 73 74 | |

| Health-related quality of life | 259 73 | 242 62 | 152 | |

| PICS—physical health | 356 61 69 | 252 68 | ||

| PICS—cognition | 156 | 340 52 68 | ||

| PICS—mental health | 272 73 | 161 | ||

| Adverse events | 169 | |||

| Social health | 173 | |||

| Communication (n=4) | Survival | 139 | ||

| Care-related outcomes* | 239 51 | 147 | ||

| PICS—mental health | 172 | |||

| Early rehabilitation (n=3) | Survival | 356 68 69 | ||

| Care-related outcomes* | 169 | |||

| PICS—physical health | 256 69 | 168 | ||

| PICS—cognition | 156 | 168 | ||

| Adverse events | 169 | |||

| Neurocognitive (n=6) | Survival | 259 70 | 175 | |

| Care-related outcomes* | 359 70 75 | 173 | ||

| Health-related quality of life | 259 73 | 152 | ||

| PICS—physical health | 152 | |||

| PICS—cognition | 240 52 | |||

| PICS—mental health | 173 | |||

| Social health | 173 | |||

| Pharmacological discontinuation (n=3) | Survival | 148 | ||

| Care-related outcomes* | 249 58 | 148 | ||

| Sepsis (n=11) | Survival | 1044 45 54 64–67 71 74 76 | 163 | |

| Care-related outcomes* | 174 | |||

| Ventilation (n=2) | Survival | 155 | 157 | |

| Care-related outcomes* | 255 57 | |||

| Combined (n=9)† | Survival | 142 | 260 61 | 146 |

| Care-related outcomes* | 342 50 53 | 343 61 62 | 141 | |

| Health-related quality of life | 242 62 | |||

| PICS—physical health | 161 | |||

| PICS—mental health | 161 | |||

Studies68 69 are separate outcome analyses of unique data collected within one clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01656317).

*Care-related outcomes comprise outcomes pertaining to care after ICU discharge, eg, readmissions or discharge disposition.

†Includes the ABCDEF bundle.

ICU, intensive care unit; PICS, post-intensive care syndrome.

As an example of a positive effect on PICS outcomes, a before–after study in an Italian mixed ICU evaluated an in-ICU psychological intervention including emotional support to patients and family members, counselling, stress management, coping strategies and family-centred decision-making. One year after ICU discharge, fewer patients from the intervention group showed a high risk for post-traumatic stress disorder (21.1% vs 57%) or needed psychiatric medication after discharge (1.7% vs 8.1%), and their HrQoL was higher (EQ-5D visual analogue scale 77.4 vs 72.4). No significant differences were found concerning anxiety, depression, and return to previous employment.73

Critical appraisal

In almost half of the RCTs and the quasi-experimental studies (n=12/30), baseline characteristics of control and intervention group significantly differed, posing a high risk of confounding bias.40–42 45 52 54 57 58 62 74–76 The proportion of studies lacking comparability of study groups could be even higher as articles frequently lacked information to assess the comparability of the study groups. Another issue with included RCTs was the lack of blinding: All RCTs (n=5) blinded the outcome assessor for treatment assignment, but only one study reported patient blinding,61 and no study reported study team blinding. The reliability of outcome measures in quasi-experimental studies was often compromised or not reported. In three studies, participants selectively received different care other than the exposure, making these studies prone to confounding bias.46 57 69 In two of eight cohort studies, the study groups did not originate from the same population, posing a risk of selection bias59 66 (online supplemental tables S5–S7).

Discussion

Main findings

We conducted a scoping review on the long-term effects of ICU bundles on patient-relevant outcomes. Our five main findings were as follows: First, most included studies reported long-term survival or care-related outcomes, but few studies assessed HrQoL or PICS-related outcomes of cognition, mental health and physical health. Second, even if studies assessed HrQoL or PICS, we found little standardisation in methodology, instruments and follow-up time. Third, most studies on sepsis bundles found a positive effect on survival, but there was no conclusive positive effect of other bundles on different patient-relevant outcome categories. Fourth, interventions commonly relied on simple implementation strategies such as conducting educational meetings. Fifth, while studies were conducted in a variety of settings, more than half were before–after studies and half were single-centre studies. In the critical appraisal, we identified a high risk of bias.

What is already known

Outside of ICU bundle implementation research, the epidemiology of long-term sequelae after critical illness is well described: Up to 34% of the patients show anxiety symptoms 12–14 months after ICU discharge,77 up to 29–30% have depressive symptoms 12–14 months after discharge,78 and up to 34% have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.79 Cognitive impairments occur in 4–62% of the patients,80 5–70% show dependencies in instrumental activities of daily living,81 and the HrQoL is below population norms.22

Although the high frequency of long-term impairments constitutes an imperative to include these outcomes in ICU bundle research, no other review of ICU bundles has focused on long-term patient-relevant outcomes. Previous reviews have assessed ICU bundle implementation strategies,82 barriers and facilitators of ICU bundle implementation83 and the effect on outcomes.84 Our results support previous reviews, which concluded that studies implementing ICU bundles often lack structure regarding use, reporting and justification of implementation strategies.83 84 In line with previous reviews,82–84 we showed that some implementation strategies (eg, educational activities and audit and feedback) were more frequently used than others. We translated implementation strategies to the respective ERIC strategies to enhance comparability; however, just like previous reviews on ICU bundles found out,83 none of our included studies used the ERIC taxonomy. Another scoping review for evidence-based practices in critical care in general also found considerable variability in the nomenclature that was used to describe implementation strategies.85 Standardised and transparent reporting is recommended to compare the effectiveness of certain strategies.83 86 Corresponding to our critical appraisal, previous reviews also found that most evidence on ICU bundle effects has weak methodological quality.85 In our work, half of the studies were conducted in a single centre, making them prone to centre-specific effects such as local ICU culture. Unknown centre-specific effects may limit the generalisability of results to other hospitals and contexts.

Practical implications and directions of future research

Our work yields practical implications and directions for future research. Studies on ICU bundles that used long-term patient-relevant outcomes mostly assessed mortality or care-related outcomes, but HrQoL and PICS appear rarely assessed. Hence, this scoping review identified a research gap for high-quality research on the effect of ICU bundles on HrQoL and PICS, but not so much on mortality and care-related outcomes. Closing the research gap is difficult as post-ICU follow-up studies take time and are challenging for research teams.87 Reasons include high post-ICU mortality, loss to follow-up, missing data, instrument selection and high demands on constraint time and personnel.87 However, the relevance for patients provides a strong impetus for conducting these studies, with observation periods ideally years after discharge. To ease the comparison and facilitate results synthesis in meta-analyses, there is a need to adhere to a common and standardised instrument set (eg,88 89). The definition of a core outcome set for long-term effects of ICU bundle interventions, which could be included in the Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials initiative database,90 may facilitate the harmonisation.

We identified several studies that implemented a sepsis bundle and found a positive effect on long-term survival. Hence, as a practical implication, clinicians may consider using multicomponent implementation strategies to implement a sepsis bundle, ideally using a theory-guided approach.91 For a stronger recommendation, studies identified in this review could be included in a meta-analysis. For other bundles, for example, neurocognitive bundles or combined bundles (including the ABCDEF bundle), we found little and inconclusive evidence of improved outcomes. Hence, at this point we are unable to recommend that intensivists implement these bundles to improve long-term patient-relevant outcomes. The variation in instruments and time points, the risk of bias and the varying complexity level of implementation strategies may have contributed to the unequivocal conclusions on the bundle effects. ICU bundles may improve short-term patient outcomes, but the low-quality evidence has already prevented a clear recommendation for ICU bundle implementation in a previous review.84

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this scoping review include the rigorous methodology: First, the review was preregistered on Open Science Framework31 and its protocol was published.32 Second, the search strategy was developed according to PRESS recommendations.34 Third, we performed an extensive hand search to collect records missed by our search strategy. Fourth, selection, charting and critical appraisal were performed independently by two researchers. Fifth, though not mandatory for scoping reviews, we performed a quality appraisal. Finally, we used the ERIC framework to group implementation strategies,38 which enhances the comparability to other studies.

Limitations of this work also warrant consideration. First, there is no consensus on a definition of patient-relevant outcomes. We intended to use a broad definition that included general and ICU-specific outcomes but might have missed relevant studies. Second, there is no consensus on the definition of long-term. We used a broad definition of ICU discharge or later to include any study that assessed outcomes beyond a patient’s ICU stay, but our pragmatic definition resulted in the inclusion of studies that only measured outcomes shortly after or at ICU discharge. A more restrictive definition would have drastically reduced the number of included studies. Third, by including ‘bundle’ as a necessary term in our search strategy, we may have missed articles that described multicomponent interventions without referring to them as bundles. For example, a recently published cluster RCT evaluated the effects of an individually tailored, multicomponent nursing intervention on delirium prevention, which may be considered a bundle. Despite implementation efforts, the time spent on intervention components, ICU readmission rate, 28-day and 90-day mortality did not improve significantly.92 The term ‘bundle’ has been well-established for many years, and we mitigated the risk of missing relevant articles by conducting a comprehensive hand search. Fourth, the research question and search strategy were developed by a research team with expertise in critical care, quality improvement, care bundles, PICS and post-ICU follow-ups. While this expertise relates to many areas of the review, the clinical focus may have biased our results. Finally, as this was not intended in our study protocol,32 we did not synthesise the effects of the included studies. A synthesis could be performed in future meta-analyses, despite the challenges due to the heterogeneity of implemented bundles, outcomes, instruments and time points.

Conclusions

Our systematic literature search and scoping review identified 38 studies on the effect of ICU bundles on long-term patient-relevant outcomes. The studies pertained to a variety of bundles, most commonly the sepsis bundle. The majority were quasi-experimental before–after studies and single-centre or two-centre studies with bias risks identified in the critical appraisal. Despite their undisputed relevance for patients, we only identified a few studies that reported long-term HrQoL and PICS outcomes of cognition, mental health and physical health. While most studies on sepsis bundles indicated a survival benefit, the effect of other bundles on different long-term patient-relevant outcomes was inconclusive. This may have been due to the large variability in instruments and time points. Hence, future research should focus on: (1) Assessing long-term HrQoL and PICS-related outcomes; (2) using standardised instruments and common time points; (3) employing high-quality research designs and clearly describing bundle interventions and implementation strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Julius J. Grunow for the PRESS review of our search strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: Conceptualisation: NP, ERB and A-CK. Methodology: NP, ERB and MN. Project administration: ERB, NP and A-CK. Supervision: BW and CDS. Visualisation: ERB and NP. Writing—original draft: NP and ERB. Writing—review and editing: A-CK, MN, BW and CDS. Guarantor: NP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: NP, A-CK, ERB and MN have no conflicts of interest to declare. BW reports grants from Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss/Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) – Innovationsfonds and the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), outside the submitted work, and consulting fees from OrionPharma, honoraria from Dr F. Köhler Chemie, support for attending meetings and travel from Teladoc Health, a leadership role as ESICM NEXT Chair, a member role in the ESICM ARDS Guideline Group and a member role in the COVRIIN Group of the Robert Koch Institute. CDS reports grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft/German Research Society, during the conduct of the study; grants from Drägerwerk AG & Co. KGaA, grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft/German Research Society, grants from Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR)/German Aerospace Center, grants from Einstein Stiftung Berlin/Einstein Foundation Berlin, grants from Gemeinsamer Bundesausschuss/Federal Joint Committee (G-BA), grants from Inneruniversitäre Forschungsförderung/Inner University Grants, grants from Projektträger im DLR/Project Management Agency, grants from Stifterverband/Non-Profit Society Promoting Science and Education, grants from European Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care, grants from Baxter Deutschland GmbH, grants from Cytosorbents Europe, grants from Edwards Lifesciences Germany, grants from Fresenius Medical Care, grants from Grünenthal, grants from Masimo Europe, grants from Pfizer Pharma PFE, personal fees from Georg Thieme Verlag, grants from Dr F. Köhler Chemie, grants from Sintetica, grants from Stifterverband für die deutsche Wissenschaft e.V./Philips grants from Stiftung Charité, grants from AGUETTANT Deutschland, grants from AbbVie Deutschland. KG, grants from Amomed Pharma, grants from InTouch Health, grants from Copra System, grants from Correvio, grants from Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften, grants from Deutsche Gesellschaft für Anästhesiologie & Intensivmedizin (DGAI), grants from Stifterverband für die deutsche Wissenschaft/Medtronic, grants from Philips Electronics Nederland, grants from BMG, grants from BMBF, grants from BMBF, grants from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft/German Research Society, outside the submitted work; in addition, CDS has a patent 10 2014 215 211.9 licensed, a patent 10 2018 114 364.8 licensed, a patent 10 2018 110 275.5 licensed, a patent 50 2015 010 534.8 licensed, a patent 50 2015 010 347.7 licensed and a patent 10 2014 215 212.7 licensed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; peer reviewed for ethical and funding approval prior to submission.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Lilly CM, Swami S, Liu X, et al. Five-year trends of critical care practice and outcomes. Chest 2017;152:723–35. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.06.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKenzie MS, Auriemma CL, Olenik J, et al. An observational study of decision making by medical intensivists. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1660–8. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pronovost PJ, Murphy DJ, Needham DM. The science of translating research into practice in intensive care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010;182:1463–4. 10.1164/rccm.201008-1255ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green LW. Making research relevant: if it is an evidence-based practice, where’s the practice-based evidence? Fam Pract 2008;25 Suppl 1:i20–4. 10.1093/fampra/cmn055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schultz MJ, Wolthuis EK, Moeniralam HS, et al. Struggle for implementation of new strategies in intensive care medicine: anticoagulation, insulin, and lower tidal volumes. J Crit Care 2005;20:199–204. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2005.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rak KJ, Kahn JM, Linstrum K, et al. Enhancing implementation of complex critical care interventions through interprofessional education. ATS Sch 2021;2:370–85. 10.34197/ats-scholar.2020-0169OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosa RG, Teixeira C, Sjoding M. Novel approaches to facilitate the implementation of guidelines in the ICU. J Crit Care 2020;60:1–5. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ilan R, Fowler RA, Geerts R, et al. Knowledge translation in critical care: factors associated with prescription of commonly recommended best practices for critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 2007;35:1696–702. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269041.05527.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulbrook P, Mooney S. Care bundles in critical care: a practical approach to evidence-based practice. Nurs Crit Care 2003;8:249–55. 10.1111/j.1362-1017.2003.00039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Resar R, Griffin FA, Haraden C, et al. Using care bundles to improve health care quality. In: IHI innovation series white paper. Cambridge, USA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:165–228. 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawe CS, Ellis KS, Cairns CJS, et al. Reduction of ventilator-associated pneumonia: active versus passive guideline implementation. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1180–6. 10.1007/s00134-009-1461-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marra A, Ely EW, Pandharipande PP, et al. The ABCDEF bundle in critical care. Crit Care Clin 2017;33:225–43. 10.1016/j.ccc.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hocking C, Pirret AM. Using a combined nursing and medical approach to reduce the incidence of central line associated bacteraemia in a New Zealand critical care unit: a clinical audit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2013;29:137–46. 10.1016/j.iccn.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schramm GE, Kashyap R, Mullon JJ, et al. Septic shock: a multidisciplinary response team and weekly feedback to clinicians improve the process of care and mortality. Crit Care Med 2011;39:252–8. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181ffde08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helmick RA, Knofsky ML, Braxton CC, et al. Mandated self-reporting of ventilator-associated pneumonia bundle and catheter-related bloodstream infection bundle compliance and infection rates. JAMA Surg 2014;149:1003–7. 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman LZ, Hoesel LM, Desai A, et al. It takes an intensivist. Am J Surg 2011;201:320–3. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim JH, Hong S-K, Kim KC, et al. Influence of full-time intensivist and the nurse-to-patient ratio on the implementation of severe sepsis bundles in Korean intensive care units. J Crit Care 2012;27:414. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Angus DC, Carlet J, 2002 Brussels Roundtable Participants . Surviving intensive care: a report from the 2002 Brussels Roundtable. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:368–77. 10.1007/s00134-002-1624-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajic O, Ahmad SR, Wilson ME, et al. Outcomes of critical illness: what is meaningful? Curr Opin Crit Care 2018;24:394–400. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Davis WE, et al. Perspectives of survivors, families and researchers on key outcomes for research in acute respiratory failure. Thorax 2018;73:7–12. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerth AMJ, Hatch RA, Young JD, et al. Changes in health-related quality of life after discharge from an intensive care unit: a systematic review. Anaesthesia 2019;74:100–8. 10.1111/anae.14444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1293–304. 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1306–16. 10.1056/NEJMoa1301372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bienvenu OJ, Friedman LA, Colantuoni E, et al. Psychiatric symptoms after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-year longitudinal study. Intensive Care Med 2018;44:38–47. 10.1007/s00134-017-5009-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:502–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geense WW, van den Boogaard M, van der Hoeven JG, et al. Nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse long-term outcomes among ICU survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2019;47:1607–18. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2005;8:19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 2010;5:69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–73. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Center for Open Science . Use of patient-relevant outcome measures to assess the long-term effects of care bundles in the ICU: a scoping review protocol [OSF Registries]. 2021. Available: https://osf.io/w3pd7 [Accessed 6 Oct 2022]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Paul N, Knauthe A-C, Ribet Buse E, et al. Use of patient-relevant outcome measures to assess the long-term effects of care bundles in the ICU: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2022;12:e058314. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kersting C, Kneer M, Barzel A. Patient-relevant outcomes: what are we talking about? A scoping review to improve conceptual clarity. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:596. 10.1186/s12913-020-05442-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGowan J, Sampson M, Salzwedel DM, et al. PRESS Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;75:40–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.01.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016;5:210. 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, et al. Chapter 11: scoping reviews (2020 version). In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Adelaide, Australia, 2020. Available: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joanna Briggs . Critical Appraisal Tools. Available: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools [Accessed 6 Oct 2022].

- 38.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci 2015;10:21. 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med 2000;109:469–75. 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamdar BB, King LM, Collop NA, et al. The effect of a quality improvement intervention on perceived sleep quality and cognition in a medical ICU. Crit Care Med 2013;41:800–9. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182746442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Olsen KM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1024–36. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Collinsworth AW, Priest EL, Masica AL. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of the ABCDE bundle: impact of bundle adherence on inpatient and 1-year mortality and costs of care. Crit Care Med 2020;48:1752–9. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loberg RA, Smallheer BA, Thompson JA. A quality improvement initiative to evaluate the effectiveness of the ABCDEF bundle on sepsis outcomes. Crit Care Nurs Q 2022;45:42–53. 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Alsawalha LN, et al. Outcome of septic shock in older adults after implementation of the sepsis “bundle.” J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:272–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gurnani PK, Patel GP, Crank CW, et al. Impact of the implementation of a sepsis protocol for the management of fluid-refractory septic shock: a single-center, before-and-after study. Clin Ther 2010;32:1285–93. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu V, Herbert D, Foss-Durant A, et al. Evaluation following staggered implementation of the “Rethinking Critical Care” ICU care bundle in a multicenter community setting. Crit Care Med 2016;44:460–7. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vuong C, Kittelson S, McCullough L, et al. Implementing primary palliative care best practices in critical care with the Care and Communication Bundle. BMJ Open Qual 2019;8:e000513. 10.1136/bmjoq-2018-000513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan BA, Perkins AJ, Campbell NL, et al. Pharmacological management of delirium in the intensive care unit: a randomized pragmatic clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:1057–65. 10.1111/jgs.15781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.D’Angelo RG, Rincavage M, Tata AL, et al. Impact of an antipsychotic discontinuation bundle during transitions of care in critically ill patients. J Intensive Care Med 2019;34:40–7. 10.1177/0885066616686741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sinvani L, Kozikowski A, Patel V, et al. Nonadherence to geriatric-focused practices in older intensive care unit survivors. Am J Crit Care 2018;27:354–61. 10.4037/ajcc2018363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Black MD, Vigorito MC, Curtis JR, et al. A multifaceted intervention to improve compliance with process measures for ICU clinician communication with ICU patients and families. Crit Care Med 2013;41:2275–83. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182982671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, et al. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:370–9. 10.1007/s00134-013-3136-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, et al. Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF bundle: results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Crit Care Med 2019;47:3–14. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lefrant J-Y, Muller L, Raillard A, et al. Reduction of the severe sepsis or septic shock associated mortality by reinforcement of the recommendations bundle: a multicenter study. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2010;29:621–8. 10.1016/j.annfar.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Asehnoune K, Mrozek S, Perrigault PF, et al. A multi-faceted strategy to reduce ventilation-associated mortality in brain-injured patients. The BI-VILI project: a nationwide quality improvement project. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:957–70. 10.1007/s00134-017-4764-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cinotti R, Demeure-Dit-Latte D, Mahe PJ, et al. Impact of a quality improvement program on the neurological outcome of patients with traumatic spinal cord injury: a before-after mono-centric study. J Neurotrauma 2019;36:3338–46. 10.1089/neu.2018.6298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roquilly A, Cinotti R, Jaber S, et al. Implementation of an evidence-based extubation readiness bundle in 499 brain-injured patients. A before-after evaluation of a quality improvement project. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:958–66. 10.1164/rccm.201301-0116OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anstey MH, Litton E, Palmer RN, et al. Clinical and economic benefits of de-escalating stress ulcer prophylaxis therapy in the intensive care unit: a quality improvement study. Anaesth Intensive Care 2019;47:503–9. 10.1177/0310057X19860972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cadilhac DA, Andrew NE, Lannin NA, et al. Quality of acute care and long-term quality of life and survival: the Australian stroke clinical registry. Stroke 2017;48:1026–32. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Middleton S, Coughlan K, Mnatzaganian G, et al. Mortality reduction for fever, hyperglycemia, and swallowing nurse-initiated stroke intervention: QASC trial (Quality in Acute Stroke Care) follow-up. Stroke 2017;48:1331–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.016038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Middleton S, McElduff P, Ward J, et al. Implementation of evidence-based treatment protocols to manage fever, hyperglycaemia, and swallowing dysfunction in acute stroke (QASC): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011;378:1699–706. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61485-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sosnowski K, Mitchell ML, White H, et al. A feasibility study of A randomised controlled trial to examine the impact of the ABCDE bundle on quality of life in ICU survivors. Pilot Feasibility Stud 2018;4:32. 10.1186/s40814-017-0224-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang Q, Wang Z, Guan J. Effect of simple-bundles management vs. guideline-bundles management on elderly patients with septic shock: a retrospective study. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:5198–204. 10.21037/apm-20-2320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lv C, Wang G, Chen A. Speckle tracking algorithm-based ultrasonic cardiogram in evaluation of the efficacy of dexmedetomidine combined with bundle strategy on patients with severe sepsis. J Healthc Eng 2021;2021:7179632. 10.1155/2021/7179632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 65.Li Z-Q, Xi X-M, Luo X, et al. Implementing surviving sepsis campaign bundles in China: a prospective cohort study. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:1819–25. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.20122744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sánchez B, Ferrer R, Suarez D, et al. Declining mortality due to severe sepsis and septic shock in Spanish intensive care units: a two-cohort study in 2005 and 2011. Med Intensiva 2017;41:28–37. 10.1016/j.medin.2016.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ferrer R, Artigas A, Levy MM, et al. Improvement in process of care and outcome after a multicenter severe sepsis educational program in Spain. JAMA 2008;299:2294–303. 10.1001/jama.299.19.2294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karic T, Røe C, Nordenmark TH, et al. Impact of early mobilization and rehabilitation on global functional outcome one year after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Rehabil Med 2016;48:676–82. 10.2340/16501977-2121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karic T, Røe C, Nordenmark TH, et al. Effect of early mobilization and rehabilitation on complications in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg 2017;126:518–26. 10.3171/2015.12.JNS151744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Turner M, Barber M, Dodds H, et al. Implementing a simple care bundle is associated with improved outcomes in a national cohort of patients with ischemic stroke. Stroke 2015;46:1065–70. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cardoso T, Carneiro AH, Ribeiro O, et al. Reducing mortality in severe sepsis with the implementation of a core 6-hour bundle: results from the Portuguese community-acquired sepsis study (SACiUCI study). Crit Care 2010;14:R83. 10.1186/cc9008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Black P, Boore JRP, Parahoo K. The effect of nurse-facilitated family participation in the psychological care of the critically ill patient. J Adv Nurs 2011;67:1091–101. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05558.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Peris A, Bonizzoli M, Iozzelli D, et al. Early intra-intensive care unit psychological intervention promotes recovery from post traumatic stress disorders, anxiety and depression symptoms in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2011;15:R41. 10.1186/cc10003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kortgen A, Niederprüm P, Bauer M. Implementation of an evidence-based “standard operating procedure” and outcome in septic shock. Crit Care Med 2006;34:943–9. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206112.32673.D4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Skrobik Y, Ahern S, Leblanc M, et al. Protocolized intensive care unit management of analgesia, sedation, and delirium improves analgesia and subsyndromal delirium rates. Anesth Analg 2010;111:451–63. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d7e1b8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jacob ST, Banura P, Baeten JM, et al. The impact of early monitored management on survival in hospitalized adult Ugandan patients with severe sepsis: a prospective intervention study*. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2050–8. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31824e65d7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nikayin S, Rabiee A, Hashem MD, et al. Anxiety symptoms in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016;43:23–9. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1744–53. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Parker AM, Sricharoenchai T, Raparla S, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in critical illness survivors: a metaanalysis. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1121–9. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wolters AE, Slooter AJC, van der Kooi AW, et al. Cognitive impairment after intensive care unit admission: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:376–86. 10.1007/s00134-012-2784-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hopkins RO, Suchyta MR, Kamdar BB, et al. Instrumental activities of daily living after critical illness: a systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2017;14:1332–43. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201701-059SR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Borgert MJ, Goossens A, Dongelmans DA. What are effective strategies for the implementation of care bundles on ICUs: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2015;10:119. 10.1186/s13012-015-0306-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gilhooly D, Green SA, McCann C, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the successful development, implementation and evaluation of care bundles in acute care in hospital: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2019;14:47. 10.1186/s13012-019-0894-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lavallée JF, Gray TA, Dumville J, et al. The effects of care bundles on patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci 2017;12:142. 10.1186/s13012-017-0670-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.McNett M, O’Mathúna D, Tucker S, et al. A scoping review of implementation science in adult critical care settings. Crit Care Explor 2020;2:e0301. 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci 2013;8:139. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wilcox ME, Ely EW. Challenges in conducting long-term outcomes studies in critical care. Curr Opin Crit Care 2019;25:473–88. 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Spies CD, Krampe H, Paul N, et al. Instruments to measure outcomes of post-intensive care syndrome in outpatient care settings-results of an expert consensus and feasibility field test. J Intensive Care Soc 2021;22:159–74. 10.1177/1751143720923597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Needham DM, Sepulveda KA, Dinglas VD, et al. Core outcome measures for clinical research in acute respiratory failure survivors. An international modified Delphi consensus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1122–30. 10.1164/rccm.201702-0372OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.COMET . COMET database. 2010. Available: https://www.comet-initiative.org/ [Accessed 6 Oct 2022].

- 91.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rood PJT, Zegers M, Ramnarain D, et al. The impact of nursing delirium preventive interventions in the ICU: a multicenter cluster-randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;204:682–91. 10.1164/rccm.202101-0082OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-070962supp001.pdf (65.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-070962supp002.pdf (341.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.